This chapter examines the availability and adequacy of income support for older workers. While the main pillars of a comprehensive social protection system are in place, one-half of Korea’s population aged 65 and over lives in relative poverty. The chapter discusses options to extend and improve the different programmes. In particular, limited coverage and low payments reduce the impact of social welfare policies on poverty reduction. In addition, further reforms are needed to develop an effective three-pillar pension system based on the National Pension Scheme, company pensions and individual savings.

Working Better with Age: Korea

Chapter 5. Addressing poverty among Korean older workers

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Due to labour market failures discussed in previous chapters, many older workers are pushed outside the core labour market before reaching the retirement age with a double penalty as a result: poor quality jobs and little or no social protection. Changes in the labour market and vocational training are needed to improve outcomes for older workers but these changes will take time to materialise and may only be visible in the longer run. In the meanwhile, significant efforts are needed to address the high poverty rate among older people also in the short run. With one in two persons of age 65 and over living in relative poverty, the urgency of the social problem cannot be neglected.

While the main pillars of a comprehensive system of social protection are in place in Korea, they are still in most cases at an early stage of implementation, compared with many other OECD countries. This chapter discusses the strengths and weaknesses of the various programmes and makes recommendations to improve the system. A difference is made between urgent and structural reforms.

Towards effective social security for older workers

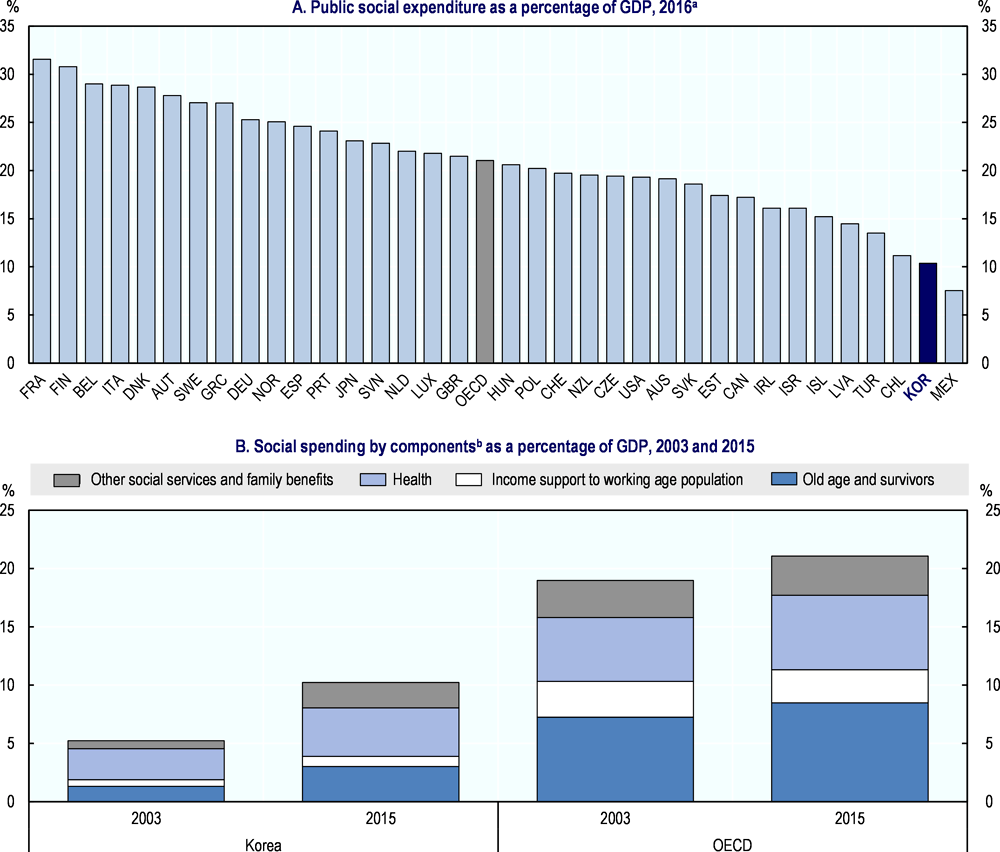

Public social spending as a percentage of GDP is still low in Korea, compared with other OECD countries, despite a continuous increase since the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. In 2016, gross public social spending stood at 10.4% of GDP – the second lowest in the OECD, well below the OECD average of 21% and only one‑third of the level in many European countries (Figure 5.1, Panel A).

Pensions and health care are the largest and fastest increasing components of Korea’s social expenditure (OECD, 2018). Even without further social benefit reform, social expenditure in Korea is projected to increase rapidly to at least 26% of GDP by 2050, because of the shift in the age structure and the gradual maturing of the current social protection system (Won and Kim, 2013). In 2015, public expenditure on old-age and survivor benefits amounted to 3.0% of GPD, still the second lowest in the OECD area and well below the OECD average of 8.5% (Figure 5.1, Panel B).

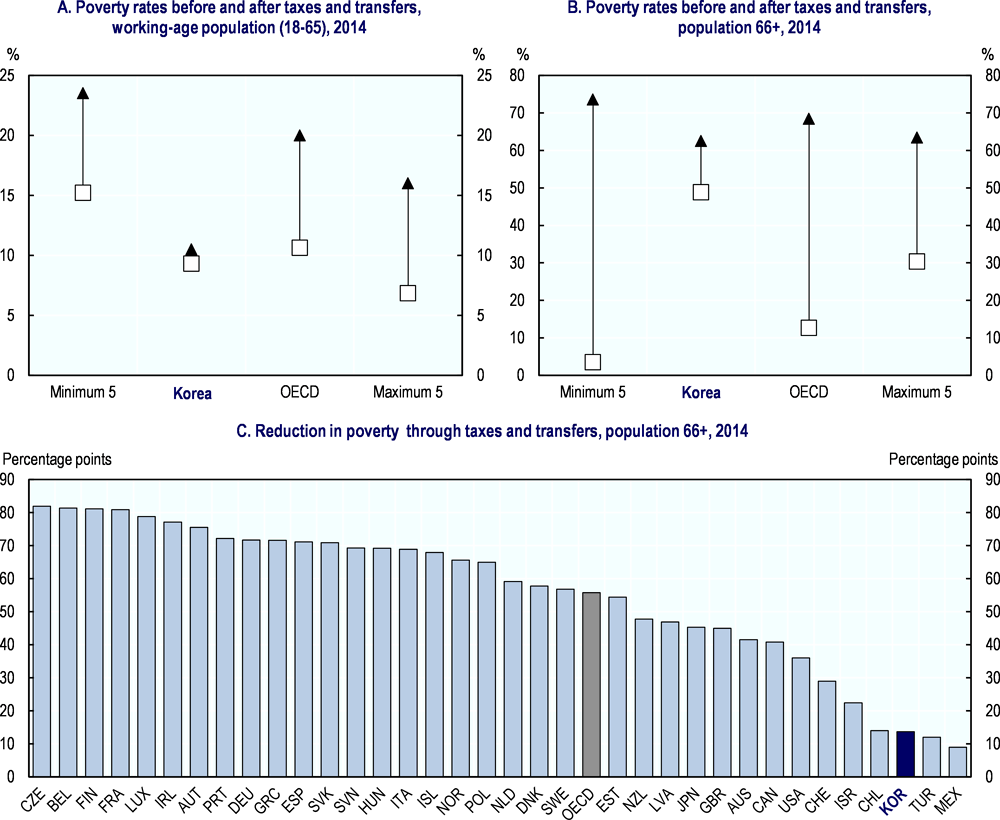

As a result of the overall low level of social spending and the importance of services rather than cash transfers, the Korean benefit system has almost no impact on poverty and inequality outcomes in the country. Data from the OECD Income Distribution database show that 10.5% of Koreans aged 18‑65 had a market income below 50% of the median income in 2014 (Figure 5.2, Panel A). The tax and benefit system reduced the relative poverty rate by only 1.2 percentage points to 9.3%. For people aged 66 and above, the reduction in relative poverty is higher (14 percentage points), but one in two of older Koreans are still living in relative poverty after transfers (Figure 5.2, Panel B).

These results are in stark contrast with most OECD countries. Tax and transfer systems reduce poverty among people aged 66 and over by 56 percentage points on average in the OECD, from 68% to 13% (Figure 5.2, Panel B). Only in Mexico and Turkey, there is less redistribution towards older people than in Korea (Figure 5.2, Panel C).

As discussed in OECD (2014), the high elderly poverty rate reflects a decline in family support before other private and public sources of old-age income have matured. In contrast to many OECD countries, where population ageing and the development of a public pension system occurred over a long time span, rapid population ageing in Korea has left the country poorly prepared for a long period. Many elderly had assumed that their children would care for them, thus making it unnecessary to prepare financially.

Figure 5.1. Social expenditure in Korea has increased but remains low in an international comparison

Note: OECD is the unweighted average of the 35 member countries.

a. Data refer to 2012 for Mexico, 2013 for Japan, 2014 for Turkey and 2015 for Canada, Chile and New Zealand.

b. Income support includes incapacity related benefits and unemployment. Other social services and family benefits includes active labour market programmes and housing.

Source: OECD Social Expenditure Database, https://data.oecd.org/socialexp/social-spending.htm.

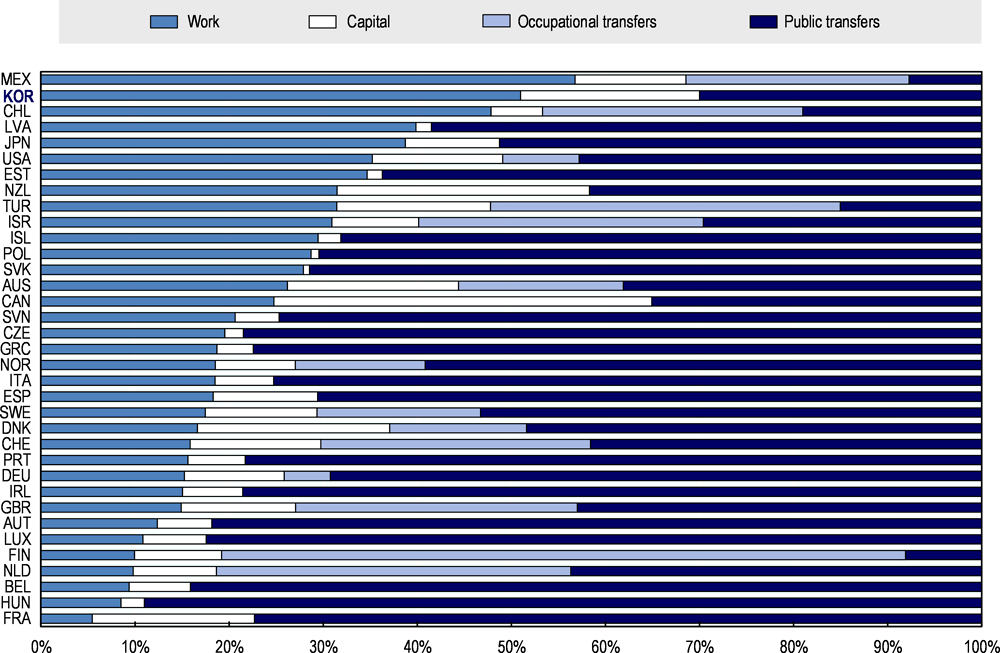

Data from the OECD Income Distribution Database show that public transfers account for only 30% of older people’s income in Korea in 2015, whereas in a typical OECD country public transfers account for nearly 60% of their income (Figure 5.3).1 In order to escape poverty, many older people in Korea have no other choice than to work. Korea is the country with the second highest share of work income in total household income of older people, accounting for half of their total income. Data from the Korean Survey of Household Finance and Living Conditions also illustrate that private transfers (accounting for only 5% of total household income in 2016) have been declining in the past five years (Table 5.1). At the same time, public transfers are gradually increasing as a share of total household income.

Figure 5.2. The Korean benefit system does little to lift older people out of poverty

Note: The Minimum 5 is the average of the 5 countries with the lowest poverty level after taxes and transfers and the Maximum 5, the average of the 5 countries with the highest poverty level after taxes and transfers. OECD is an unweighted average. Data for Chile refer to year 2015 and to 2012 for Japan.

Source: OECD Income Distribution Database, http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=IDD.

Figure 5.3. Work accounts for half of older people’s household incomes in Korea

a. Data refer to 2012 for Japan and to 2015 for Chile, Finland, Israel, Korea, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Source: OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD), www.oecd.org/social/income-distribution-database.htm.

Table 5.1. The share of public transfers in older people’s household income is increasing while private transfers are declining

Income sources of households with a head aged 60 years and over, 2012-16 (in percent)

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total income |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Work income |

35 |

38 |

39 |

40 |

41 |

|

Business income |

25 |

24 |

24 |

24 |

21 |

|

Asset income |

12 |

12 |

11 |

10 |

11 |

|

Public transfer income |

19 |

19 |

20 |

20 |

22 |

|

Private transfer income |

8 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

5 |

Source: Statistics Korea (2016), “Results of the Survey of Household Finances and Living Conditions in 2016".

The evidence shows that the social security system in Korea is currently insufficient to reduce poverty among older people. Comparing Korea with other OECD countries reveals that policy can do much more in financially supporting older people. An effective multi‑pillar approach is necessary to ensure adequate retirement income and reduce poverty among older workers. The following sections discuss and evaluate each of the existing policy programmes and presents recommendations to improve their effectiveness.

Reducing in-work poverty among older workers by the Earned Income Tax Credit

With the intention to support the large number of people not able to earn a decent living despite being in employment, the Korean government introduced an in-work support scheme in 2008, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). By reducing the income tax bill or providing cash refunds when the resulting tax deduction is larger than the actual tax to be paid, the scheme raises the take-home pay for working households with low incomes. Similar income tax credit schemes are used in many OECD countries and were shown to contribute to poverty reduction and to increase employment (OECD, 2005). Empirical evidence also suggests that the effectiveness of such tax credits is greatest in countries with low income tax rates and low social benefits for the non‑employed – both being characteristic of the situation in Korea (Bassanini, Rasmussen and Scarpetta, 1999).

Since the introduction of the EITC scheme in 2008, the scope and coverage of the programme have been repeatedly expanded to include more and more workers. Initially, the EITC targeted families with children, but it was then expanded to childless couples and, eventually, also to single‑member households aged 40 and over, and self-employed people.2 Income and asset thresholds and the maximum pay‑out were also augmented repeatedly and varied with the composition of the household (see Table 5.2 for an overview of the eligibility criteria as they apply in 2017).

Table 5.2. Eligibility criteria for the Earned Income Tax Credit in 2017

|

Criteria |

The eligibility requirements |

|---|---|

|

Recipient |

|

|

Household |

|

|

Total income threshold |

|

|

Assets |

|

Source: Korean National Tax Service website, https://www.hometax.go.kr.

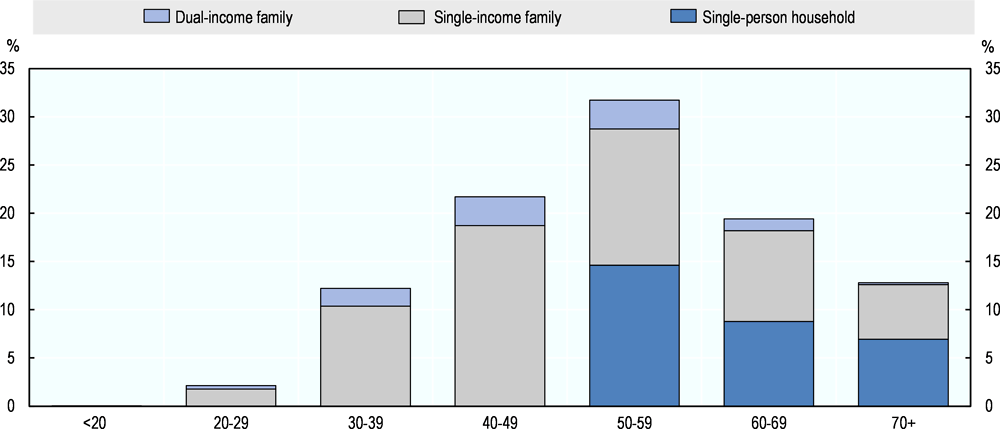

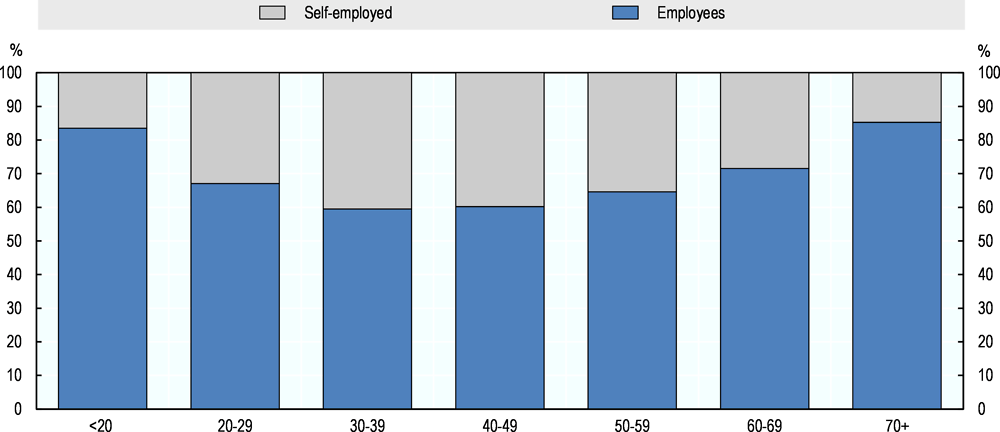

The various changes in the eligibility criteria over the past few years led to an increase in the total number of benefiting households from around 0.5 million in 2008 to nearly 1.4 million in 2016, accounting for about 7% of the total number of households in Korea. Two-thirds of all EITC households have a head aged 50 or more (Figure 5.4), and a large proportion (47%) of these older households consists of single-person households, without a spouse or children at charge. While overall one in three EITC households has a self‑employment income, this share decreases from age 50 onwards (Figure 5.5). In the age group 70 and over, only one in seven EITC households are self‑employed. This finding is surprising given the high incidence of self‑employment among older workers. Possibly, some older workers receive benefits from the Basic Livelihood Security Programme (see below), making them ineligible for EITC benefits. Another reason could be unawareness among older self-employed people about the EITC system. Since most self-employed people tend to register their business with the tax authorities, informality does not seem to be a plausible explanation. To address this issue, a better understanding is needed of the low incidence of self‑employment among older EITC beneficiaries.

Figure 5.4. Two thirds of all EITC recipiency households have a head aged 50 or more

Both the maximum tax credit and the income level at which EITC is phased out are comparable with similar in-work tax credit schemes in other OECD countries.3 In 2016, the maximum tax credit ranged from 2.1% of the average wage for singles to 5.0% for childless single-earner couples and 6.2% for childless dual-earner couples (Table 5.3). These maxima put Korea in the middle range in an international comparison for singles and on the higher end for couples without children. Only the United Kingdom allows significantly higher maximum credits for childless couples. In regard to the wage level at which in‑work benefits are phased out, Korea ranks in the middle of countries for singles and towards the higher end for couples without children.

Figure 5.5. Very few of the older recipients of EITC are self-employed

Table 5.3. EITC benefits for households without children are comparable to those in other OECD countries

Maximum benefit amounts and phase-out levels for EITC and in-work benefits in selected OECD countries for households without children, as a percentage of average wages (AW)

|

Maximum benefit (% of AW) |

Benefit phased out at (% of AW) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Single |

Couple |

Single |

Couple |

|

|

Korea |

2.1 |

5.0 – 6.2 |

38 |

62 – 74 |

|

Canada |

2.1 |

3.8 |

37 |

57 |

|

Finland |

1.6 |

3.2 |

220 |

440 |

|

France |

2.4 |

2.6 |

62 |

92 |

|

New Zealand |

1.5 |

1.5 |

21 |

21 |

|

United Kingdom |

7.9 |

13.4 |

39 |

54 |

|

United States |

1.0 |

1.04 |

29 |

40 |

Note: Data refer to 2016 for Korea and to 2010 for the other countries.

Source: Update based on OECD (2013), Strengthening Social Cohesion in Korea, OECD Publishing, Table 2.3, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264188945-en; and Kim, M.J (2016), “The Current Status of the Earned Income Tax Credit in South Korea and the Implications for Japan – Earned Income Tax Credit or Reduced Tax Rate?”, NLI Research Institute Report.

Despite the relatively high maximum benefit levels in an international comparison, the average EITC payment in 2016 was only around 2.2% of the average wage, with around one-third of all participants receiving less than KRW 500 000 or 1.5% of the average wage (Table 5.4, Panel B). Among older EITC households, and especially in the age group of 70 years and older, there are significantly more recipients with annual incomes of less than KRW 5 million (i.e. below one-third of the minimum wage) than among younger EITC households (Table 5.4, Panel A).

Table 5.4. Older EITC recipient households are over-represented among low-earners

|

A. Percentage distribution of EITC recipients by wage level and age, 2016 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total |

<20 |

20-29 |

30-39 |

40-49 |

50-59 |

60-69 |

70+ |

|

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Under KRW 5 million |

32.9 |

54.3 |

22.1 |

18.7 |

19.0 |

29.7 |

37.3 |

73.3 |

|

KRW 5 < 10 million |

24.1 |

16.5 |

19.7 |

18.8 |

20.1 |

29.7 |

30.5 |

13.3 |

|

KRW 10 < 15 million |

21.4 |

15.9 |

22.5 |

25.4 |

25.2 |

22.6 |

20.6 |

9.2 |

|

KRW 15 < 20 million |

15.8 |

9.1 |

25.4 |

26.8 |

26.0 |

12.7 |

9.3 |

3.7 |

|

KRW 20 < 25 million |

5.8 |

4.3 |

10.3 |

10.4 |

9.6 |

5.3 |

2.3 |

0.6 |

|

B. Percentage distribution of EITC recipients by benefit amount received and age, 2016 |

||||||||

|

|

Total |

<20 |

20-29 |

30-39 |

40-49 |

50-59 |

60-69 |

70+ |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Under KRW 5 million |

36.2 |

43.0 |

25.6 |

24.1 |

23.5 |

36.9 |

36.6 |

68.9 |

|

KRW 0.5 < 1 million |

27.9 |

22.6 |

24.9 |

24.3 |

24.2 |

34.0 |

32.2 |

16.4 |

|

KRW 1 < 1.5 million |

18.1 |

16.8 |

25.0 |

26.7 |

26.8 |

14.4 |

15.1 |

7.3 |

|

KRW 1.5 < 2.1 million |

17.8 |

17.7 |

24.6 |

25.0 |

25.5 |

14.7 |

16.0 |

7.5 |

Source: Administrative data from the National Tax Service.

Because of the relatively short history of EITC in Korea, evaluation studies are still rare. Available findings are mixed but, overall, point to a positive impact on labour supply – in terms of both participation and working hours – especially of households at the phase-in range of EITC; i.e. the range within which EITC benefits increase as earnings increase and therefore the range when work incentives are strongest (Lee, Kwon and Moon, 2015; and Song and Bahng, 2014). However, while Jeong and Kim (2015) found positive effects on the poverty rate of couple families, they found no significant effects on the poverty rate for elderly single-member households, largely because the benefits are too small to lift people out of poverty. So far, there seem to be no studies that looked at the impact and implications of the inclusion of self‑employed people.

Overall, findings suggest that EITC has a positive impact on labour supply and poverty for certain groups. Yet, EITC alone is insufficient to reduce the high level of in‑work poverty among older workers in Korea and thus can only be one element in a broader strategy. For older workers, the most pressing issue is to ensure that all those who are potentially eligible for EITC are reached. Especially among self-employed older workers, EITC coverage seems far below actual in-work poverty rates.

The high poverty rate among older people – including those who are in employment – calls for a stronger focus on this target group. It may be worth to raise the benefit levels of EITC for persons over 50 to reduce in-work poverty in this group, like in Sweden. Sweden introduced an in-work tax credit in 2007 and extended it several times for specific age groups, with the aim of increasing their labour force participation. The credit for those older than 65 is substantially larger than for other age groups.

Insuring older workers against the risk of unemployment

Employment Insurance (EI) is a comprehensive labour market and social security measure in Korea that includes: i) employment security and vocational skills development programmes; and ii) unemployment insurance providing income support to displaced workers. However, as discussed at length in various OECD publications, including Back to Work: Korea (OECD, 2013b), Strengthening Social Cohesion in Korea (OECD, 2013a) and Connecting People with Jobs: Korea (OECD, 2018), EI suffers from both low coverage and relatively low payments for average-wage workers.

Low coverage of employment insurance

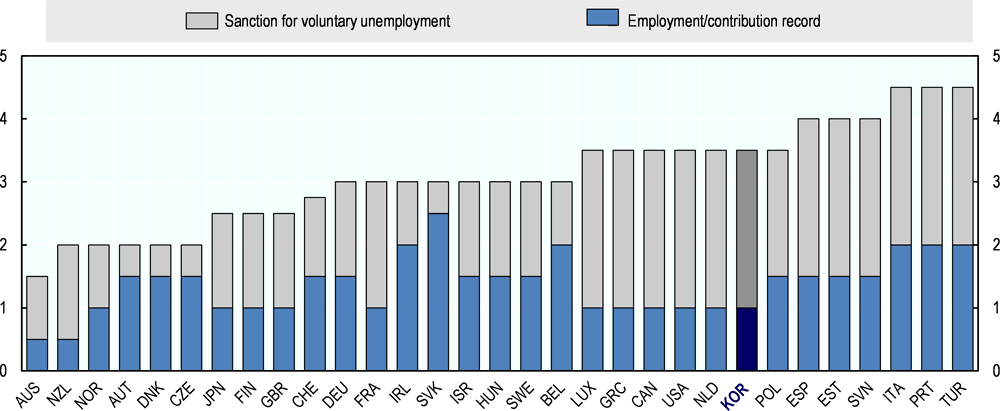

In principle, EI covers all employees on a mandatory basis, except for most persons working less than 60 hours a month or 15 hours a week, and family labour. Most self‑employed people can opt in on a voluntary basis. To be entitled to EI, a beneficiary must have at least 180 days of coverage during the last 18 months, be registered at an employment security office, capable of work and available for work. In addition, unemployment must not be due to voluntary leaving, misconduct, a labour dispute, or the refusal of a suitable job offer. Overall, Korean EI eligibility conditions are towards the stricter end of the regulations found across OECD countries, largely due to the sanctions for voluntary unemployment (Figure 5.6).

Figure 5.6. Korea has rather strict eligibility criteria for employment insurance

Source: Venn, D. (2012), “Eligibility Criteria for Unemployment Benefits: Quantitative Indicators for OECD and EU Countries”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 131, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k9h43kgkvr4-en.

While there are substantial grey areas between voluntary and involuntary separations, “honorary retirement” (i.e. voluntary retirement before the mandatory retirement age; see Box 4.1 for details) is a justifiable reason for separation. As such, people who go on voluntary retirement are, in principle, entitled to EI. Workers aged 65 and over who are newly employed are excluded from receiving unemployment benefits although they can still participate in employment security and vocational skills development programmes.

In 2016, less than half of all workers aged 50-64 (43.5%) had access to an employment safety net (Table 5.5). The share of covered older workers is considerably lower than for other age groups. This can be explained by two factors: the high share of only voluntarily insured self-employed in the age group 50-64 (21.8%) and a high share of non-enrolled older wage workers (18%). The drop in EI coverage with age is directly related to the switch in occupation after honorary retirement discussed in Chapter 2 of this report. While many older workers are covered by EI during their main job, they are much less likely to be covered in the jobs they take up afterwards.

Table 5.5. Less than half of all older workers have access to an employment safety net

Distribution of workers with and without employment safety net by age and employment status, 2016

|

Age |

Wage workers with employment safety net |

Wage workers without employment safety net |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Not enrolled |

Legally excluded (wage workers) |

Non-wage workers |

|||||

|

Employer |

Self-employed |

Unpaid family workers |

|||||

|

Firms with 5 or more employees |

Firms with less than 5 employees |

||||||

|

Total |

53.2 |

14.9 |

5.8 |

1.7 |

4.4 |

15.5 |

4.5 |

|

15‑29 |

67.3 |

24.6 |

1.8 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

3.4 |

2.0 |

|

30‑49 |

63.5 |

12.5 |

2.4 |

1.8 |

5.0 |

11.6 |

3.2 |

|

50‑64 |

43.5 |

18.0 |

2.6 |

2.4 |

5.6 |

21.8 |

6.1 |

Note: This figure adapts and updates calculations similar to those published by Yoo, G. (2013), “Institutional Blind Spots in the South Korean Employment Safety Net and Policy Solutions”, KDI Focus.

Source: Supplementary results of the Economically Active Population Survey by employment type, 08/2016.

The drop in EI eligibility among older workers is unfortunate, as it happens at a moment that they have much more volatile employment conditions and are in higher need of an adequate employment safety net. As discussed in detail in Connecting People with Jobs: Korea (OECD, 2018), strong efforts are needed to i) boost EI coverage among those who are currently (voluntarily) excluded from the system; and ii) better enforce EI regulations to ensure better coverage among undocumented workers. These recommendations particularly hold for older workers, who are over‑represented in both categories.

To expand EI coverage, OECD (2018) recommends to seek effective ways to ensure coverage among self-employed workers, possibly by making EI contributions mandatory for this group; and to allow workers who voluntarily leave their jobs to access EI after a suitable waiting period, rather than disqualifying them outright.

For instance, several OECD countries have resorted to mandatory EI registration for self‑employed workers to improve coverage among this group of workers. Indeed, the voluntary approach used in Korea has not resulted in significant coverage rates, nor did it in other OECD countries. Greece and Slovenia are two countries that have recently switched from voluntary to mandatory coverage for self-employed persons (OECD, 2018). Mandatory coverage would also have the advantage that older workers are more likely to contact the Employment Centre and make use of the available employment services, hereby increasing the likelihood that they find better jobs and avoid poverty.

Value and duration of unemployment benefits

While benefit recipients receive in principle 50% of their previous wage, in reality EI has become a flat-rate payment. Since its introduction in the 1990s, the maximum EI payment has remained largely unchanged. In contrast, the minimum EI payment, fixed at 90% of the minimum wage, has gradually increased in line with the minimum‑wage increase. Today the minimum EI payment is almost equal to the maximum, which implies that the link between previous earnings and benefit amounts has largely disappeared.

As a result, while being relatively generous for low-wage workers, the EI system pays rather low benefits for the average worker in Korea. As discussed in Connecting People with Jobs: Korea (OECD, 2018), the EI benefit floor as a percentage of the average wage for full-time employees is higher than in any other unemployment benefit system across the OECD. Korea is also the only country that brings all primary-tier unemployment beneficiaries above the relative poverty threshold of 50% of the average wage.

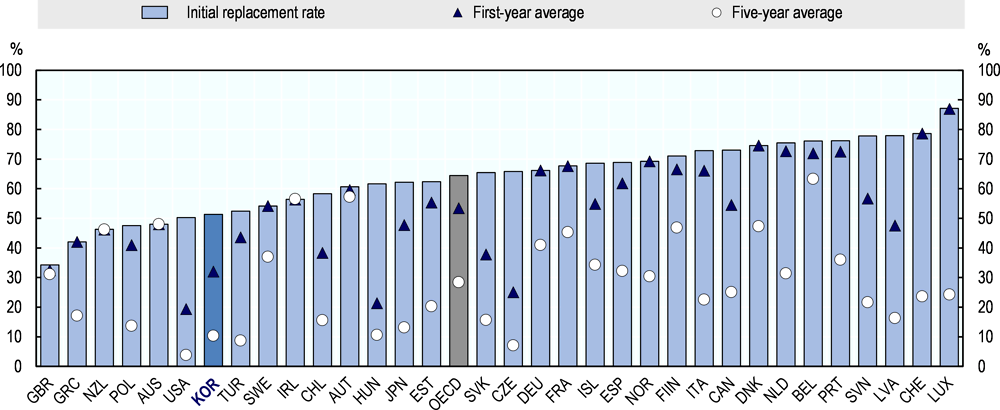

However, for a worker earning the average wage, benefit levels are rather low due to the binding maximum EI level. When considering family benefits as well as income taxes and mandatory social security contributions paid on unemployment benefits, the net replacement rate for an average-income earner, at 50%, is in the bottom quarter among an OECD ranking (Figure 5.7). As a comparison, the ratio of net income out of work to net income while in work is 65% in the OECD on average.

Figure 5.7. Employment insurance benefits in Korea replace a low share of previous income

Note: The net replacement rate (NRR) is the ratio of net income out of work to net income while in work, considering income taxes and mandatory social security contributions paid by employees. Social assistance and housing-related benefits are not included, while family benefits are included. NRRs are calculated for a 40-year-old worker with an uninterrupted employment record since age 22. They are averages over four different stylised family types and two earnings levels. OECD is an unweighted average of the 34 countries shown (excluding Mexico).

Source: OECD Tax-Benefit Models, www.oecd.org/els/social/workincentives.

In addition, the maximum duration during which beneficiaries can receive an EI payment in Korea is one of the shortest in the OECD. The duration of benefits increases with age at the time of job loss and the length of the contribution record, ranging from 90 days for people insured for less than a year (irrespective of age) to 240 days for people aged 50 or older. Only four OECD countries have benefit durations that are shorter than 8 months. As a result of the short duration, the net replacement rate averaged over the first year is only 32%; the third-lowest share in the OECD (again, Figure 5.7).

Enhancing social benefits for elderly people

Basic Livelihood Security Programme

The Basic Livelihood Security Programme (BLSP) is a comprehensive means-tested social assistance programme in Korea. Introduced in 2000 in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis, the programme provides various cash benefits to eligible persons living in absolute poverty (including a living benefit, housing benefit, medical benefit, education benefit, child-birth benefit, funeral benefit and self-support benefit).

In order to receive one or more of the benefits, an applicant has to meet the income and family requirements. The income requirement has been drastically reformed in July 2015 to tackle the “all or nothing” principle: Before reform, either all benefits were available to the beneficiary or none. More specifically, the threshold income level (income and assets converted into income) was diversified across benefits: it is now 30% of the standardised median income (derived from a household survey and similar to the minimum cost of living) for living benefit, 43% for housing benefit, 40% for medical benefit and 50% for education benefit. Today, people not eligible for the main payment (living benefit) may still receive other benefits, reducing the risk of poverty traps that discourage work.

The family requirement implies that applicants cannot receive benefits if they have a close family member (child, spouse or parent) capable of supporting them – the so‑called family support obligation rule. However, eligibility does not depend on whether such family support is actually provided. The capacity of family support is measured by the family members’ income and assets. While the threshold income to be accepted as an incapable legal supporter was raised from 130% of the minimum cost of living to 100% of median income in July 2015, it still means that relatives with a relatively low income are supposed to help their income-poor family member.

Income requirements and the family support obligation both keep the BLSP caseload below the actual poverty numbers. In 2016, about 1.7 million Koreans received one or several BLSP benefits, corresponding to around 3.2% of the population. About 76% of them received a living benefit and 85% received a housing benefit. The caseload is similar to the OECD average but low in comparison with OECD countries with immature overall social protection systems. Not even half of all Korean people living in absolute poverty (estimated at around 7-8%) are covered by the programme.

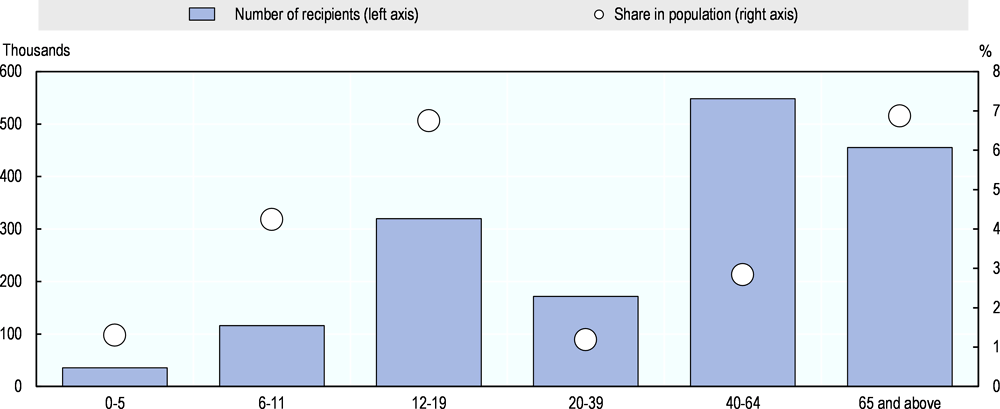

The largest beneficiary groups are those aged 40-64 and 65 and above (Figure 5.8). When compared with the overall population numbers by age group, people aged 65 and above are over-represented in the BLSP programme. However, compared with the total share of elder people living in absolute poverty (estimated at around one-fourth), a recipiency rate of 6.9% among older people is very low. The low coverage is largely related to the strict family eligibility criteria. While people with the possibility of assistance from family members are not eligible for the benefit, many children cannot or will not help their elderly parents nowadays in Korea.

Figure 5.8. BLSP recipiency in Korea is highest among youth and older people

Source: 2015 Annual statistics on BLSP recipients (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2017), UN Data, UNSD Demographic Statistics (http://data.un.org).

The government recently announced a plan to abolish the family support obligation for the housing benefit as of 2018 and to exclude, as of 2019, the application of the family support obligation for the living benefit and health benefit to the households of the lower 70% of the income distribution with household members aged 65 or above or a severely disabled person. These reforms would be particularly welcome for the large group of older people living in absolute poverty without support from their relatives.

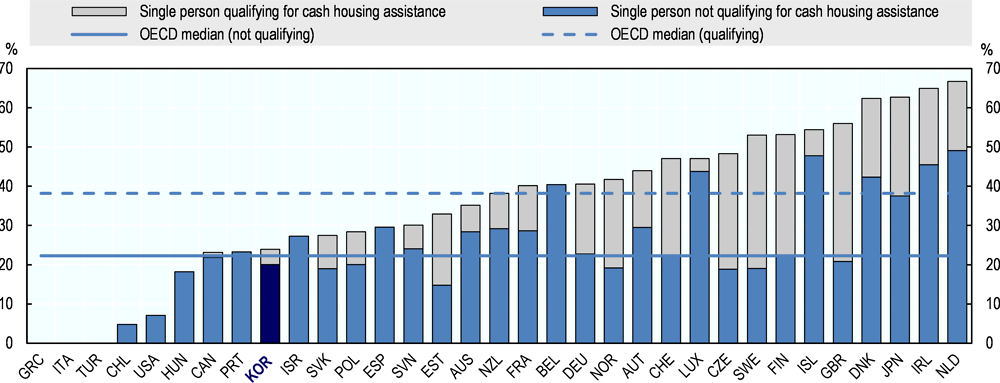

Apart from the coverage, also the benefit level of the BLSP programme is rather limited. Estimates based on the OECD tax and benefit model for cash minimum income benefits show that Korea ranks among the bottom third of OECD countries with respect to the level of living and housing benefits (taken together) as a share of the average income in the respective country. Taking into account net income taxes and social contributions, a single person eligible for the living and housing benefits would receive only about 24% of the median household income in Korea (Figure 5.9). The comparable median payment value across OECD countries for people eligible to both payments is around 40%; housing benefit in particular is significantly higher in many OECD countries.

In sum, it would be important to take further steps to broaden the coverage and increase the generosity of BLSP, especially in view of much higher than average poverty rates in Korea for some groups of the population. Benefit levels are low by OECD standards and eligibility conditions – notably those regarding the absence of so-called “supporting persons” – may still prevent many poor older persons from receiving BLSP benefits.

Figure 5.9. Payments provided by minimum income benefit are relatively low in Korea

Note: Median net household incomes are from a survey in or close to 2011, expressed in current prices and are before housing costs (or other forms of “committed” expenditure). Results are shown on an equivalised basis and account for social assistance, family benefits and housing-related cash support, net of any income taxes and social contributions. US results include the value of Food Stamps, a near-cash benefit. Where benefit rules are not determined on a national level but vary by region or municipality, results refer to a “typical” case (e.g. Michigan in the United States, the capital in some other countries). In countries where housing benefits depend on actual housing expenditure, the calculation represents cash benefits for someone in privately-rented accommodation with rent plus charges equal to 20% of the average gross full-time wage.

Source: OECD Tax-Benefit Models, www.oecd.org/els/soc/benefits-and-wages.htm.

Basic Pension

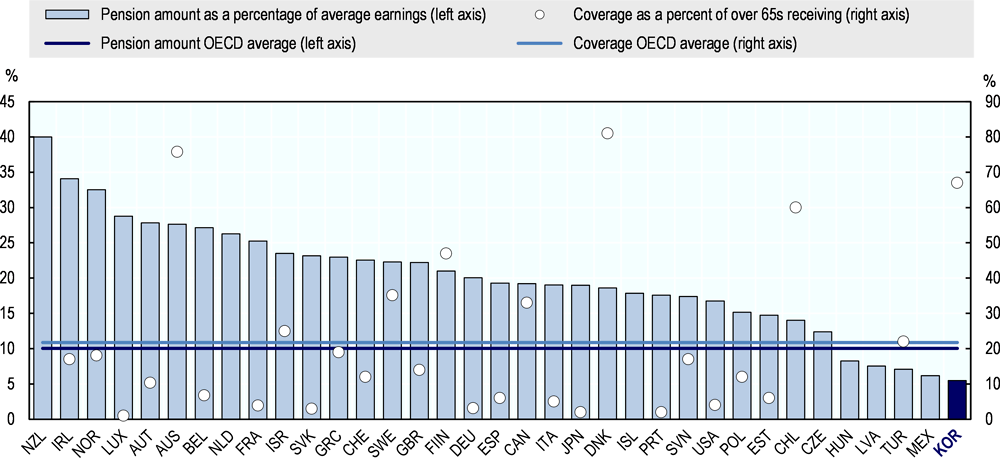

In addition to its Basic Livelihood Security Programme, Korea has a social welfare programme targeted at individuals aged 65 and above. This Basic Pension is a non‑contributory means-tested benefit for people who have not contributed for long enough to be entitled to a contribution-based pension payment. The maximum monthly benefit level has been KRW 200 000 since 2014, equivalent to 5.5% of the average earnings in 2016 and lower than any other non‑contributory basic pension benefit across the OECD (Figure 5.10). The new government, which began its term in May 2017, announced a plan to increase the maximum benefit level to KRW 250 000 in April 2018 and thereafter gradually to KRW 300 000 by April 2021. Even at the new level, the Basic Pension would still be amongst the lowest in the OECD,4 where the average benefit equalled 20% of average earnings in 2016.

Figure 5.10. The value of Korea’s Basic Pension is lower than in any other OECD country

Source: OECD (2017), Pensions at a Glance 2017: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2017-en.

At the same time, the Basic Pension covers an exceptionally large proportion of the Korean population aged 65 and over. Nearly 70% of the elderly population receives a Basic Pension. This is similar to the shares found in Australia, Chile and Denmark but a multiple of the OECD average of only 22% for similar non‑contributory basic pension schemes across 28 OECD countries (Figure 5.10). In other words, the Basic Pension in Korea spreads out resources very thinly over a large segment of the older population.

The Basic Pension could play a more important role in reducing the high poverty rate among older people in Korea, by better targeting scarce government resources to those with the highest need. More specifically, narrowing the coverage of the Basic Pension to people aged 65 living in absolute poverty would leave room to increase the benefit level for these people significantly, without affecting government’s overall budget.

Strengthening the multi-pillar pension system

In addition to social welfare programmes, Korea has a multi-pillar pension system for its elderly population which includes the following pillars:

Pillar 1: Public pension schemes including the National Pension Scheme and Occupational pension schemes

Pillar 2: Company pension system

Pillar 3: Individual, voluntary pension savings for retirement

Improving the National Pension Scheme to reduce old-age poverty

The National Pension Scheme (NPS) was created in 1988 to establish a major income support system for the elderly population. Its coverage was initially limited to regular employees in firms with at least ten workers and then gradually expanded to include all workplaces and eventually all types of employees as well as the self-employed. The pension age for the NPS is currently 61 years with at least ten years of contributions. This is gradually going to be increased to 65 years by 2033. A reduced early pension can be withdrawn from the age of 56 years (this age will be increased in parallel to 60 years).

The NPS is a defined-benefit programme, combining earnings-related and redistributive components. The income an insured person earns during the insured period is converted to the present value, and the benefit is annually adjusted based on national consumer price fluctuations. The target replacement rate after 40 years of contributions was 46% in 2016 and is being reduced by 0.5 percentage points for every year until reaching 40% in 2028 to improve the financial sustainability of the system. The contribution rate started at 3% of monthly income in 1988 and was increased to 6% in 1993 and to 9% in 1998 (shared equally between the worker and the employer). People above the age of 60 do not pay contributions and benefits do not accrue after this age.

By the end of 2016, the NPS insured 21.8 million people and had KRW 558.3 trillion worth in assets, accounting for 38% of GDP (National Pension Service, 2017). The NPS offers five types of benefits: old-age pension, disability pension, survivor pension, lump‑sum refund, and lump-sum death payment (Table 5.6).

Table 5.6. Types of benefits offered in Korea’s National Pension System

|

Types of Pension |

Eligibility conditions |

|---|---|

|

Old-age pension |

The old-age pension is the major benefit in the National Pension program. People who have been insured more than 10 years can be paid the old-age pension as of age 61. |

|

Disability pension |

The disability pension is paid if the insured has a disability, and the benefit level is determined based on the severity or conditions of physical or mental illness. |

|

Survivor pension |

The survivor pension is designed to guarantee the income of the spouse and eligible family, whose livelihoods had been maintained by the deceased, when the insured person dies. |

|

Lump-sum refund |

A lumps-sum refund is payable when a person can no longer be covered under the NPS because of age, emigration or death, etc., while failing to qualify for other types of benefits. |

|

Lump-sum death payment |

When an insured person dies, and there are no eligible survivors for a Survivor pension or Lump-sum refund, a funeral grant is given to the extended-family. |

Source: National Pension Service.

The NPS has a number of weaknesses as a major source of income for the elderly population, including a low coverage rate, a low actual replacement rate and financial instability. First, although participation has been mandatory by law since 1999, a large number of people are not insured, especially non-regular workers and self-employed. While 85% of regular workers are registered with the national pension system, the rate is only 36.5% among non-regular workers (Statistics Korea, 2017). Overall, around 60% of the working-age population was insured under the national pension system at the end of 2016 (National Pension Service, 2017). The low coverage reflects a lack of trust in the pension system as well as evasion by self-employed and non-regular workers. In addition, some self-employed workers are exempted from paying premiums due to low income. According to government’s projection in 2013, only 41% of the elderly are expected to receive NPS benefits in 2030 (OECD, 2016). Second, given the recent introduction of the NPS, the average contribution period is still short and the actual pension benefit low. At KRW 353 thousand per month in 2016, the average benefit equalled only about 10% of the average wage (National Pension Service, 2017). Even looking ahead, the actual replacement rate would still be less than 20% in 2030-40. As a result, the impact of the NPS in reducing poverty is limited by its recent introduction and a slow acceptance by the public. Third, NPS spending is set to rise faster than NPS revenues, despite the gradual cut in the replacement rate to 40% and the planned hike in the pension eligibility age from 61 to 65 in 2033. The reform in 2007 cannot solve the structural imbalance between expenditures and revenues: if the current system is maintained, the NPS fund is expected to be fully depleted by 2060 (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2014).

Addressing the low NPS coverage requires more rigorous policies to increase compliance of self‑employed and non-regular workers. In a similar vein as for the EI system, NPS coverage could be improved by increasing the penalties for employers who do not enrol their workers and expanding the resources and mandate of the labour inspectorate to control compliance of employers (see OECD, 2018). Combining the collection of taxes and social insurance contributions as is currently planned will improve identification of the self‑employed and transparency about their income.

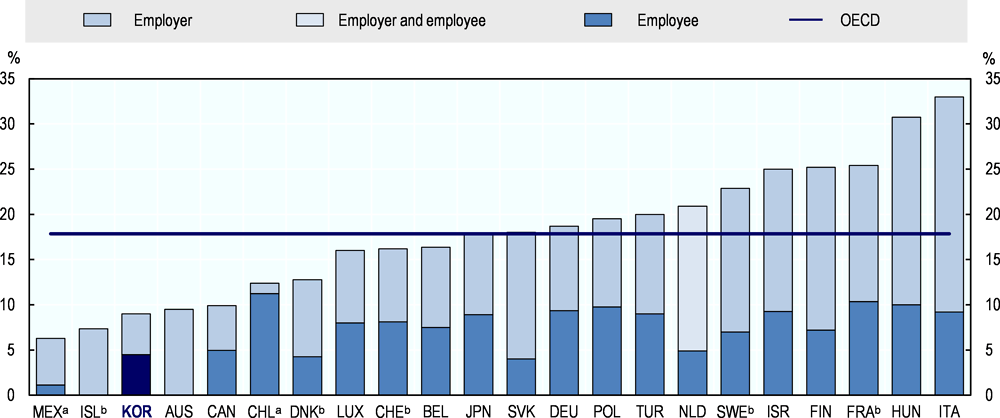

The best option to achieve financial sustainability of the NPS is to raise the contribution rate (Jones and Urasawa, 2014). Set at 9%, the current contribution rate is the second‑lowest among the 22 OECD countries where pension contributions are mandatory for both private and public pensions (Figure 5.11). The adjustment of the contribution rate should begin as soon as possible, as delays would make the necessary increase larger.

Figure 5.11. Contributions to the National Pension Scheme are very low in Korea

Note: OECD is the unweighted average of the 22 countries shown in the chart.

a. Data refer to private contributions.

b. Data refer to both public and private contributions.

Source: Table 7, OECD (2017), Pensions at a Glance 2017: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2017-en.

Limiting the financial burden of occupational pensions

The three occupational pension schemes for civil servants, military personnel and private-school teachers insure more than 1.5 million workers, with the scheme for civil servants accounting for more than two-thirds of the total. The occupational pensions have similar benefit structures and a rather generous replacement rate (76%) compared with the NPS, intended to compensate civil servants for relatively low wages and to attract a competent work force with a long-term commitment to public service.

Occupational pension benefits were increased repeatedly under political pressures without corresponding financing measures, forcing them to rely increasingly on government subsidies. Two reforms, in 2009 and 2015, aimed at enhancing the financial viability of the civil service pension scheme by raising the contribution rate, reducing the accrual rate and raising the minimum age of eligibility (Table 5.7). The reforms also had a roll-over effect on the pension scheme for private-school teaches since both are linked by the Private School Teachers and Staff Pension Act. Nevertheless, the outlook remains difficult as both the number of retirees and their life expectancy are rising. The gradual application of the contribution and accrual rates reduces the impact of the reform. For the military pension no reform has taken place so far.

Table 5.7. Features of Korea’s occupational pension scheme for civil servants

|

Old system |

2009 Reform |

2015 Reform |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Contribution rate |

5.5% |

7% |

9% |

|

Accrual rate |

2.1% |

1.9% |

1.7% |

|

Eligibility age |

60 years old |

60 if employed before 2009, 65 years if employed after 2010 |

Gradual increase from 60 to 65 by year of retirement |

Source: Government Employee Pension Service.

Promoting company pension systems

The weakness of the NPS and the decline in family support left a void that is to be filled in part by company pensions. In 2005, the government launched a plan to encourage the conversion of the mandatory retirement allowance into a company pension to provide better income security for retired workers. The retirement allowance, which was introduced in 1953 and became legally mandatory in 1961, requires firms to pay departing employees a lump‑sum equivalent to at least one month of wages per year of work. It was initially intended to be a support for the unemployed and the retired in the absence of unemployment insurance and pensions, similar to a severance payment. Nevertheless, given high labour turnover – average job tenure in Korea is only six years – most workers receive the retirement allowance numerous times during their working life. About 70% of workplaces that offer retirement allowances have paid the allowance prior to retirement at least once (Jones and Urasawa, 2014).

The company pension system introduced in 2005 allows firms to transform the retirement allowance into a defined-benefit (DB) or a defined-contribution (DC) scheme, in which the contribution is predetermined and the benefit depends on the investment returns. The decision is based on an agreement between management and employees. Companies that introduce a pension are exempt from paying retirement allowance, although many still do.

To promote the shift to a company pension system, the government has launched several measures since 2005 to make the retirement allowance less attractive. First, tax deduction for internally-funded retirement allowance plans has been phased out by 2016. Second, withdrawal of a worker’s retirement allowance before leaving the company (including for retirement) is limited to specific purposes since 2012. Third, employees moving between jobs are required to place their retirement allowance in an Individual Retirement Pension (IRP). Fourth, the government expanded the tax credit for the IRP at the workers’ own expenses from maximum KRW 4 million to KRW 7 million. Fifth, since July 2017 all workers including the self-employed are allowed to join an IPR scheme.

The company pension system has grown steadily in the past ten years, covering nearly 6.2 million employees and KRW 147 trillion of the total asset in 2016 (National Pension Service, 2017). However, the system’s impact remains limited. By 2016, only 17% of the firms in Korea had introduced a company pension system, with the percentage increasing with firm size, from 15% of firms with less than 30 employees to 90% of firms with 300 or more. Among workers eligible for company pension plans – those with more than one year of job tenure – 47.7% were enrolled at the end of 2016. Regular workers account for the vast majority of those enrolled in the company pension system. Only 1.6% of those who received the retirement benefit received the payment as an annuity during 2016, while all others still received a lump-sum payment.

It is important to accelerate the shift away from the lump-sum retirement allowance in order to supplement the weak National Pension Scheme. Additional measures are needed to strengthen this second pillar of the Korean pension system. Most importantly, while retirement pension plans apply to all workers in all firms irrespective of their size, more should be done to ease restrictions on the grounds of employment duration and types thereby expanding the target of mandatory enrolment. Various discussions are ongoing in this regard between the National Assembly and the government, including a suggestion to include all workers with three months of tenure and plans to limit the maximum amount and the permitted causes of early withdrawals. Consideration should also be given to aligning the age when the retirement pension can be drawn with the NPS pensionable age.

Encouraging private-sector savings for retirement

Voluntary individual pension accounts, which are open to individuals regardless of their employment status, were introduced in 1994. Various personal pension accounts are offered by insurance companies, banks, and asset management companies. Individuals who contribute a specified amount of money for more than five years are entitled to receive monthly pensions starting at age 55. They are allowed a tax credit of up to 13.2% of the amount placed in such accounts up to a ceiling of KRW 4 million a year. Taxation, which is deferred until the individual begins receiving benefits at age 55, is set at a rate of 3.3% to 5.5%, depending on the recipient's age and the amount of annual pension.

Coverage of voluntary individual pension plans remains somewhat limited in Korea, accounting for about 24% of the working-age population (Table 5.8). In addition, a substantial number of individuals withdraw their funds before reaching age 55: the share of investors closing their account rises from 28% after five years to 48% after ten years (Jones and Urasawa, 2014). The total amount of assets in Korea’s private pension plans including both company pension plans and voluntary individual pensions reached 26.9% of GDP in 2016 which compares with an unweighted OECD average of 50% and a weighted average of 83%.

In sum, despite recent reform efforts individual pension accounts remain underdeveloped in Korea and effort is needed to continue reform and further strengthen this third pillar of the pension scheme. It is important to increase the penalties for early withdrawal of funds and provide more favourable tax credits for people’s individual accounts.

Table 5.8. Coverage and assets for private pension plans in Korea could be expanded

Coverage as a percentage of the working-age population (15-64 years) and total assets as a percentage of GDP and in millions of USD, latest year available

|

Coverage |

Assets |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Occupational |

Personal |

% of GDP |

USD million |

|

|

Australia |

x |

.. |

123.9 |

1 523 302 |

|

Austria |

13.9 |

18.0 |

6.0 |

21 980 |

|

Belgium |

59.6 |

.. |

6.9 |

30 612 |

|

Canada |

26.3 |

25.2 |

159.2 |

2 403 874 |

|

Chile |

.. |

.. |

69.6 |

174 480 |

|

Czech Republic |

x |

52.6 |

8.4 |

15 684 |

|

Denmark |

x |

18.0 |

209.0 |

611 895 |

|

Estonia |

x |

12.3 |

16.4 |

3 656 |

|

Finland |

6.6 |

19.0 |

59.3 |

134 867 |

|

France |

24.5 |

5.7 |

9.8 |

230 184 |

|

Germany |

57.0 |

33.8 |

6.8 |

223 906 |

|

Greece |

1.3 |

.. |

0.7 |

1 254 |

|

Hungary |

.. |

18.4 |

4.3 |

5 105 |

|

Iceland |

x |

45.2 |

150.7 |

32 359 |

|

Ireland |

38.3 |

12.6 |

40.7 |

118 322 |

|

Israel |

.. |

.. |

55.7 |

177 293 |

|

Italy |

9.2 |

11.5 |

9.4 |

165 238 |

|

Japan |

45.4 |

13.4 |

29.4 |

1 354 754 |

|

Korea |

x |

24.0 |

26.9 |

364 634 |

|

Latvia |

0.3 |

11.4 |

12.7 |

3 340 |

|

Luxembourg |

5.1 |

.. |

2.9 |

1 659 |

|

Mexico |

1.7 |

.. |

16.7 |

156 503 |

|

Netherlands |

x |

28.3 |

180.3 |

1 335 227 |

|

New Zealand |

6.8 |

74.8 |

24.4 |

45 109 |

|

Norway |

.. |

26.7 |

10.2 |

36 899 |

|

Poland |

1.6 |

66.6 |

9.3 |

41 038 |

|

Portugal |

3.7 |

4.5 |

10.8 |

21 092 |

|

Slovak Republic |

x |

19.0 |

11.2 |

9 523 |

|

Slovenia |

.. |

.. |

7.0 |

2 963 |

|

Spain |

3.3 |

15.7 |

14.0 |

164 241 |

|

Sweden |

x |

24.2 |

80.6 |

389 264 |

|

Switzerland |

x |

.. |

141.6 |

904 380 |

|

Turkey |

1.0 |

13.9 |

4.8 |

35 217 |

|

United Kingdom |

.. |

.. |

95.3 |

2 273 713 |

|

United States |

40.8 |

19.3 |

134.9 |

25 126 592 |

|

OECD |

Simple: |

50.0 |

38 140 159 |

|

|

Weighted: |

83.0 |

Note: “x” = Not applicable; “..” = Not available.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2017), Pensions at a Glance 2017: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2017-en.

Conclusion

High poverty rates among older people, including those who are in employment, call for significant improvements in social security. While the main pillars of a comprehensive system of social protection are in place, many programmes are still immature and only gradually capturing the population of older workers. Recent reforms have contributed to improving the situation but more is needed to financially support older people.

First, general protection systems should be expanded. The Earned Income Tax Credit which intends to support people not able to earn a decent living despite being employed would be more effective, notably for older workers in second careers, if eligibility criteria and benefit amounts were to be revised. Similarly, the Basic Livelihood Security Programme, Korea’s social assistance measure, could be more effective in reducing poverty. While recent reforms have put an end to the “all or nothing” nature of payments, the benefit level itself remains low by OECD standards and eligibility conditions – notably the “family support obligation” – still affect older persons disproportionately.

Secondly, further pension reform is needed to ensure those entering retirement have an adequate standard of living while those who still want to work are rewarded in doing so. Korea’s Basic Pension could be better targeted and the payment value increased to provide a more solid safety-net. This is all the more important as benefits paid under Korea’s National Pension have been significantly reduced to ensure financial sustainability. In addition, measures could be taken to extend both the institutional and effective coverage of the National Pension itself. For many non-regular workers, employers are still managing to evade their obligations to document their workers formally and pay into the measure, similar to EI. In addition, the contribution rate should be raised to achieve financial sustainability of the National Pension.

Finally, further measures could be taken to foster the implementation of retirement pension plans notably among small and medium-sized enterprises. Despite several government initiatives over the past decade to encourage the conversion of the mandatory retirement allowance into a retirement pension, the allowance continues to be used as severance payment throughout workers’ careers. More radical measures need to be taken to transform the allowance into a second pillar of the pension system.

References

Bassanini, A., J. Rasmussen and S. Scarpetta (1999), The Economic Effects of Employment-Conditional Income Support Schemes for the Low-Paid, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/083815484206.

Jeong, C. and J. Kim (2015), “The redistributive effects of EITC and of CTC on one-earner and dual-earner household”, Korean Social Security Studies, Vol. 31/1.

Jones, R. and S. Urasawa (2014), "Reducing the High Rate of Poverty Among the Elderly in Korea", OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1163, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jxx054fv20v-en

Kim, M.J (2016), “The Current Status of the Earned Income Tax Credit in South Korea and the Implications for Japan – Earned Income Tax Credit or Reduced Tax Rate?”, NLI Research Institute Report.

Lee, D., G. Kwon and S. Moon (2015), “Studies on policy effects of the EITC”, The Korean Association for Policy Studies, Vol. 24/2.

Ministry of Health and Welfare (2014), 2013 Yearbook of Health and Welfare, Sejong-si.

National Pension Service (2017), 2016 National Pension Statistics Facts book, National Pension Research Institute, Jeonju-si.

OECD (2018), Connecting People with Jobs: Korea, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2017), Pensions at a Glance 2017: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2017-en.

OECD (2016), OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-kor-2016-en.

OECD (2014), OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2014, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-kor-2014-en.

OECD (2013a), Table 2.3 in Strengthening Social Cohesion in Korea, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264188945-en.

OECD (2013b), Korea: Improving the Re-employment Prospects of Displaced Workers, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264189225-en.

OECD (2005), OECD Employment Outlook 2005, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2005-en.

Song, H. and H. Bahng (2014), “The Effect of EITC on Job Creation in Korea”, The Korean Economic Review, Vol. 62/4.

Statistics Korea (2017), Supplementary Results of the Economically Active Population Survey by Employment Type, Daejeon.

Statistics Korea (2016), Results of the Survey of Household Finances and Living Conditions in 2016, Daejeon.

Venn, D. (2012), “Eligibility Criteria for Unemployment Benefits: Quantitative Indicators for OECD and EU Countries”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 131, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k9h43kgkvr4-en.

Won, J. and T. Kim (2013), “Projecting Social Expenditure and Total Tax Burden in Korea -A Study on Forecasting Social Expenditure for OECD Countries and Corresponding Total Tax Revenue for Korea”, http://repository.kihasa.re.kr:8080/handle/201002/10893 (accessed on 27 April 2017).

Yoo, G. (2013), “Institutional Blind Spots in the South Korean Employment Safety Net and Policy Solutions”, KDI Focus No. 28 (eng.), September 2013, Seoul, https://www.kdevelopedia.org/download.do?timeFile=/mnt/idas/asset/2014/09/17/DOC/PDF/04201409170134127079951.pdf&originFileName=13273_2.pdf.

Notes

← 1. It should be noted that incomes measured for households and older people are assumed to draw on the earnings of younger family members with whom they may live. For older people who live in multi-generational households work is likely to be a more important income source.

← 2. The extension of the EITC to single-member households was done in several stages: in 2013 single‑member households aged 60 years and above became eligible; the age threshold was further reduced to 50 years in 2015 and to 40 years in 2017.

← 3. As discussed in OECD (2018) and OECD (2013a), EITC is less generous than comparable in-work schemes in OECD countries for households with children as these countries tend to have higher child top-up benefits.

← 4. Assuming a constant inflation rate between 2016 and 2021 – the core inflation rate was 1.6% in Korea in 2016 (https://stats.oecd.org/) – the maximum monthly benefit would equal 7.6% of the average earnings by 2021. If other countries do not increase their monthly benefit, Korea would become the fourth-lowest in the OECD ranking.