This chapter examines Korea’s water governance framework, including mechanisms for horizontal and vertical co-ordination in relation to the WELF nexus. The chapter explores options for improved river basin management and stakeholder engagement. Lessons learnt and best practices from OECD countries are provided.

Managing the Water-Energy-Land-Food Nexus in Korea

Chapter 4. Towards effective water governance for the sustainable management of the Water-Energy-Land-Food nexus in Korea

Abstract

4.1. Introduction

The previous chapters have argued that managing the WELF nexus requires: i) coordinated policies and plans; ii) the capacity to reflect local situations and to make decisions at basin level; and iii) stakeholder engagement, preferably at basin level. Governance is a means to an end and water policies and institutional fit need to be tailored to different water, socio-economic and political contexts. While it is well recognised that there are no one-size-fits-all solution to water challenges, this chapter proposes a menu of options fit for the Korean context, inspired by best institutional practices and findings based on the OECD Principles on Water Governance (OECD 2015a; 2016; 2018).

Previous responses to water challenges in Korea were, to a large degree, based on technology and infrastructure development to augment water supply. Current and future responses will increasingly have to be about moving towards decentralised, coordinated and inclusive decision-making for efficient water use, where water users and other stakeholders are part of decision-making processes.

Much international experience of water reform has clearly moved towards polycentric governance. In a simplified way, this means shifting away from top-down mono-centric government approaches, to new modes of water governance that blend top-down and bottom-up approaches, including changing roles for government and increased engagements from civil society (NGOs, farmers’ associations, consumer associations, community based organisations, etc.) and the private sector (see for example OECD, 2015b; Pahl-Wostl and Knieper, 2014; and Tropp, 2007).

The government of Korea has demonstrated clear intentions of moving towards more polycentric, integrated and multilevel governance regimes through proposals of increased stakeholder engagement, integrating water quality and quantity under one ministry, and strengthening basin governance as an important scale for managing the WELF nexus. Some of these reforms are now starting to be implemented. But coping with existing and future water challenges raises not only the question of what should be done, but also who does what, at which level of government and how? Policy responses will only be viable if they are coherent, if stakeholders are properly engaged, if well-designed regulatory frameworks are in place, if there is adequate and accessible information, and if there is sufficient capacity, integrity and transparency.

4.2. Identifying water policy gaps

Korea faces a range of water policy and governance related gaps or challenges (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1. Water policy gaps and some possible causes in Korea

|

Policy-implementation gaps |

Possible causes |

|---|---|

|

Gaps in the policy-formulation process |

Political disagreements and different interests among key government stakeholders leading to no consensus on policy reform |

|

Gaps in the operationalisation of policy |

Institutional fragmentation, including misaligned decision-making and policy implementation Siloed and piecemeal reactive “project-oriented” approaches to respond to water challenges, leading to policy misalignments and ineffectiveness Lax enforcement of and compliance with existing policies, rules and regulations (see Chapter 3. ) Unclear separations between administrative functions of policy development, regulation, project development and implementation, and day-to-day operations |

|

Gaps related to the characteristics and behaviour of stakeholders |

Different vested interests among stakeholders Lack of capacities among NGOs and “local level” stakeholders Lack of water information, or limited access to existing information |

|

Gaps related to the overarching country governance situation |

Centralised style of decision-making Limited tradition and space for multi-stakeholder dialogues, especially with non-state stakeholders |

Source: Based on OECD (2017a), Enhancing Water Use Efficiency in Korea: Policy issues and recommendations, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris. See OECD (2011) for framework on water governance gaps analysis.

Institutional reform in Korea needs to take into account water policy and governance gaps. Differences in policy formulations call for consensus building activities. The operationalisation of policies and their alignment calls for strengthened horizontal and vertical coordination mechanisms. Improved stakeholder engagement would for example require transparency and access to information and inclusive platforms where stakeholders can make their voices heard. Greater clarity on mandates of policy making, regulation and project implementation can go a long way to hold government agencies to account with regard to policy implementation. The following sections of this chapter describe the ways forward to overcome these challenges.

4.2.1. The new water policy and institutional reform

There are considerable efforts in Korea to enable water policy and institutional reform to improve policy alignment and coordination between water resources and water quality issues, and across sectors and stakeholders. The most recent water policy institutional reform was adopted by the National Assembly in June 2018. The act - called the Government Organisation Act - provides the basis for transferring responsibilities of water resources management from MoLIT to ME. As a consequence, it led to the adoption of two new acts – The Framework Act on Water Management (to be enacted June 2019) and The Water Management Technology and Industry Act (to be enacted December 2018) under ME1. In essence, transferred responsibilities and functions from MoLIT to ME include: Conservation, utilisation and development of water resources, including water allocation (permits), flood control, and the operation and conservation of water resources. MoLIT maintains responsibility for river maintenance, including the maintenance and construction of river banks for flood protection. See Table 1.2 and Table 1.3 for the full list of water acts, plans and responsibilities related to water management in Korea.

In addition, five acts have moved from the responsibility of MoLIT to ME: Act on Investigation, Planning and Management of Water Resource; Groundwater Act; Act on Construction of Dams and Assistance, etc. to their Environs; Special Act on the utilisation of Waterfronts; and Korea Water Resources Corporation Act, as well as parts of the River Act. MoLIT remains responsible for parts of the River Act and the Special Act on the Compensation of Land Incorporated into River. The General Directorate for Water Resources, three Directorates, four Flood Control Offices (at basin level) and K-water are all transferred to ME. It is expected that the interim organisational set up will be re-arranged by ME.

The transfer of water quantity management to ME holds promise of improved coordination of policies and plans at both national and basin scales. However, to keep the River Act under MoLIT may risk creating unnecessary coordination gaps or “grey zones” in relation to responsibilities of long-term planning and implementation. This can fuel further misalignments when it comes to water policy development and implementation, and missed opportunities of the WELF nexus management at both national and basin level. As part of water reform in Korea there is also a strong emphasis on the river basin level as an appropriate scale of planning. Considering that also the Flood Control Offices are moved to ME makes a strong case that the long-term planning at basin scale should be under ME (through the RBCs).

The ongoing water reform puts emphasis on basic water management principles, such as:

Water should be increasingly managed at the basin level

Integrated and coordinated approaches are key to improved water management

Water management should be based on economic efficiency and social equity

Stakeholder engagement is seen as important for improved water management development and implementation

The user pays principle should apply.

ME has proposed to develop (building on the existing Water Management Committee) a National Water Committee under the Prime Minister’s Office to promote national coordination, policy alignment across ministries and regions, and conflict mediation. It is envisaged that the committee would consist of 30-40 members from ME, experts and non-governmental organisations. The representation of non-governmental stakeholders is a new feature and reflects the government’s intention to strengthen multi-stakeholder engagement for informed and outcome-oriented contributions to water policy and planning development and implementation. The committee would set the long term national priorities in a national master plan for water.

ME has proposed to set the 10-year plan on the supply and use of water resources (ME is already setting the long-term plan for water quality, but under the new set-up also water quantity will be included). ME has also suggested to strengthen the coordination role and mandate of the existing four River Management Committees (RMCs), and propose to merge them the River Basin Committees (RBCs) under the new Framework Act on Water Management. RBCs will set the basin management work plans on the supply and use of water based on the 10-year plans set by ME. The RBCs are also suggested to have responsibilities to mediate conflicts and continue to charge water user fees and manage the river management fund.

Even though many details are still to be worked out by ME, the implementation of the new Water Act entails many potential benefits for enhanced consistency and coordination across existing legal provisions, as well as across relevant ministries, to cope with future water challenges. In financial terms, it is estimated that the integration of water quality and water quantity management can provide financial benefits in the range of KRW 15.7 trillion (KECO, Pers. Comm.). Similar studies should be undertaken to assess potential financial gains of improved water management as part of WELF nexus. It can provide guidance for coordination priorities and identify where the “low-hanging fruits” may be for financial efficiency gains.

The reform steps taken are seen as very positive but should be perceived as an iterative process. Even though water quantity and quality is put under one ministry “unification” of water management will not be an easy task and would require structural organisational changes within ME, capacity development of, and motivation by, staff, and strengthening of coordination mechanisms at all levels within ME as well as between ME and other relevant ministries, water users, water and environmental NGOs and private sector.

The biggest water user and polluter in the country - agriculture, and the responsible ministry, MAFRA - are driven by distinct policy objectives to: pursue rural development; undertake cooperation in international trade of agricultural products; and improve the income, stability and welfare of agricultural households. Still, there are policy coordination challenges between ME and MAFRA, namely due to three policy misalignments: i) agriculture water is managed more or less independently from the rest of water resources through a distinct and disjointed network of infrastructure and institutions; ii) there is little incentive to promote water use efficiency in agriculture and to make more water available for other purposes, where water is scarce; and iii) there is little incentive to reduce diffuse water pollution and create synergies within the WELF nexus.

An expanded re-organisation to manage the agricultural water of MAFRA and the river management responsibilities for disaster prevention of the Ministry of Public Safety and Security can reduce duplication of policies and budget, and solve the problems caused by lack of communication. In addition, rapid water policy decision-making and planning will be facilitated, and policy consistency and responsible administration can be expected. Furthermore, reorganisation could enable a shift from a development-oriented water management approach (i.e. reservoir constriction) to water cycle recovery.

4.3. Managing water at basin level

4.3.1. Rationale for managing water at the basin scale

Water management at the basin scale emphasises coordination of water, land and related resources, and social and economic activities in a river basin to achieve certain water-related objectives. For Korea, managing water at the basin scale has been identified as an option to better achieve water policies, as well as to more effectively manage the WELF nexus and ensure ecosystem protection in the long-term. The coordination of policies, decisions and costs are necessary across a multitude of sectors and stakeholders are necessary to achieve this.

Managing water quality and quantity at the basin scale can have certain benefits in Korea, such as:

Stakeholder engagement. Managing and cooperating on water at the natural hydrological scale can more easily bring together all upstream and downstream water users and interests for improved policy and planning coordination and implementation to reach common objectives of sustainable water and environmental development, and to mediate differences between upstream and downstream water uses.

Cross-sector coordination. Increasing competition for water across economic sectors – for food and energy security, protection against floods and droughts and to maintain ecosystem services through securing environmental flows – makes river basins the appropriate planning unit to apply water quantity and quality measures.

Communications. Collecting, managing and communicating data at the basin scale regarding water availability, water demand (including environmental requirements), and water quality can support different basin functions.

Environmental and socio-economic analysis. Water modelling and socio-economic analysis at the basin scale can provide essential information for policymakers and managers to, for example, estimate the social and economic benefits of water user efficiencies and re-allocations.

River basin management in many countries marks a policy shift from more technocratic planning and water management implementation, to increasing the role of decision-making and operations through social and political processes. River basin organisations are perceived as important fora in which stakeholder interests can be reflected and mediated, as well as providing a platform to meet the requirements of national water priorities, local realities, and base decisions and actions on robust science and engineering.

4.3.2. Korea: Managing water at the basin scale

An awareness of the unique hydrological, ecological, social and economic characteristics of each river basin is important, especially when formulating policies and plans, and for explaining and analysing the outcomes of different river basin plans and projects.

For water management purposes, Korea is divided into four major river basin areas: Han River; Nakdong River; Geum River; and Youngsan-Seomjin rivers. The characteristics of the river basins vary considerably (see Section 1.2) and the overarching priorities to be addressed in one basin differ from those in another. In addition, 30 percent of the surface water resources (medium and smaller scale rivers) fall outside the responsibility of the four basin areas, but are supposed to be managed by local government.

Each of the four major river basins display different traits of conflictive issues and needs for conflict mediation. There are a number of conflicts and tensions between upstream and downstream stakeholders within the river basins (see section 1.1.4).

Several policy instruments do not reflect basin features or local conditions in Korea. For instance, neither the river water use fee nor the multi-regional water tariff signal water-related risk (scarcity) as they reflect neither local water conditions nor shifts in water availability (OECD, 2017a). Instead, nationwide unitary rates are set for each tariff and fee, and revisions are infrequent and minor. Similarly, the water use charge for Han River is KWN 170/m3 (EUR 0.13/m3), and for the other three basins it is set to KWN 160/m3 (EUR 0.12/m3). In principle, water abstraction fees could be differentiated by basin but there is a strong perception in Korea that the cost of water should be the same for everyone (principle of water equity).

Managing water at the basin scale is a new feature in Korean water management. There are some basic institutional structures in place at the basin level that can be built on for more effective management of water and the WELF nexus. The text below outlines the current institutional structure for water governance in Korea, which is essentially consists of: i) National Water Management Committee; ii) National Water Resource Management Committee; and iii) various sub-national committees, offices and councils.

In 2015, a Water Management Committee was set up at the central level (re-established in 2017 as the National Water Resource Management Committee). It is an inter-ministerial co-ordinating and advisory body gathering water-related stakeholders across levels of government. It cannot exceed 15 members who currently are the vice-ministers that play a role in water resources management, under the chairmanship of the Minister for Government Policy Coordination. Depending on the Committee’s agenda, directors of state-owned corporations and agencies, as well as representatives of provinces and metropolitan cities, are invited to participate. The Committee is supported by a working-level committee with director-level public officials from central, provincial and metropolitan agencies involved in water management (OECD, 2017a).

The National Water Resource Management Committee deliberates on river management issues and mediate disputes over the use of river water. The Committee can have up to 50 members. The Chair and the members are appointed by ME; the Chair is a staff of ME and members can be academics, lawyers, or experts.

At the basin / sub-national level there is the following institutional set up under the jurisdiction of ME:

Four River Basin Committees, one for each major river basin, have been established. They involve multiple stakeholders from government and expert community: they are chaired by the Vice-Minister of Environment and include MoLIT’s Assistant Minister, vice-governors in each river basin and the CEO of K-water. River Basin Committees manage the river management funds, raised from the water use charges. Under the new Framework Act on Water Management, local River Management Committees, which were formerly under the responsibility of MoLIT, will be transferred to ME and merged with the River Basin Committees (to collectively become River Basin Committees). The River Management Committees, one for each major river basin, were mandated to deliberate on matters of river management and disputes. They were set up by provinces and metropolitan cities with the Chair and the members of the committee appointed by the City Mayor or Do (administrative unit) Governor. Members represented MoLIT, cities, academia and law.

Four River Basin Environmental Offices, one for each major river basin, are in charge of river basin management, waste management, regional environmental impact assessments and pollution sources management. They are also responsible for the approval of the Basic Plans for Sewerage Improvement, the maintenance of the drinking water protection areas and the water treatment facilities.

Three Regional Environmental Offices are tasked with developing and implementing environmental management plans in their areas of jurisdiction, providing formal ME opinions on environmental impact assessment (EIA) and SEA reports, and providing oversight and control of compliance by local governments (OECD, 2017b). The Regional Environmental Offices manage drinking water protection areas and the status of water purification facilities and review, approve and evaluate the “Total Water Pollution Load” management system.

Four Flood Control Offices (previously under MoLIT), one for each major river basin, have two basic functions; 1) issue water permits, and 2) provide flood forecasting, hydrological observation, and hydrological data collection and management for their respective basin. Basically they are in charge of opening and closing the dam gates.

Four River Adjustment Councils are hosted by each of the Flood Control Offices and mandated to mediate over water allocation issues. They were established in 2015 and 2016 as an emergency response to the 2015 drought, requiring negotiation and mediation across water users and other stakeholders. Each council is composed of water users, stakeholders, experts from the private sector and NGOs. River Adjustment Councils are in charge of co-ordinating river water allocation and deliberation over allocation conflicts when needed. However, since 2015 drought, these Councils have been dormant.

Under the jurisdiction of MoLIT, five Regional Construction Management Offices will remain in operation at the sub-national level to cater for the needs of five large cities (i.e. Seoul, Wonju, Daejeon, Iksan and Busan). They act as policy implementing bodies in charge of safety facilities, flood damage prevention, waterfront zoning and management, river development in relation to construction, and land use policies and practices.

In addition, as part of transferring water resources responsibilities, the Korea Water Resources Corporation (K-water) has been moved from MoLIT to ME. K-water operates at multiple scales and develops and manages water resources and water supply facilities, including for example multi-regional waterworks and multi-purpose dams.

The basin level cannot and should not replace typical central government functions of policy making and over-arching long term planning, as well as local water resources and spatial planning and implementation of rules and regulations. Managing water along hydrological borders can facilitate more effective upward and downward coordination and accountability of water decision-making. Towns and cities are also part and parcel of catchments, and need to be considered in the context of upstream and downstream dynamics in terms of water quantity and quality.

The current water reform and governance changes provide the ME an opportunity to strengthen basin coordination of the WELF nexus. But coordination benefits will not be automatic; it is critical that ME puts in place proper institutional change and staff incentive programmes that can effectively increase water quality and quantity coordination, including with MAFRA and MoTIE.

4.3.3. Managing water at the basin scale: Examples of water management cases

There are no blue prints for effective water governance. This section documents water governance systems at the basin scale in France, England/Wales and the Netherlands. Despite that water reform in the three cases started well before the adoption of the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD), they have all had to adapt basin governance to meet the WFD requirements to its requirements. Importantly, the WFD is a framework that can be implemented in different ways (see Annex 3.A). The cases show that even though they are adhering to the same framework, countries find their own unique pathway on how to implement basic water management principles.

The purpose of the case studies is to provide useful examples of water governance that can serve as inspiration for Korea. It is important to acknowledge that the hydrological, socio-economic and political contexts are diverse, and that any new system that Korea chooses to implement will be different. Based on its geophysical conditions, socio-economics and history Korea will have to find its own water management model that can meet both current and future water challenges. It is important to keep in mind that water governance is considered as path dependent, meaning that bigger changes may not come into fruition easily since they may lack support from existing institutional frameworks and may face resistance from some or many water users and other stakeholders. In this regard, it would make good sense for Korean policy makers to think in terms of iterative and step-by-step approaches towards reforming water governance.

Governing water in France

Summary: The characteristics of the river basin management in France are: (1) financial independence of river basin authorities (RBAs – Agence de l’eau) and loans/subsidies to local governments; (2) stakeholder engagement through river basin committees (RBCs) and (3) active roles of local governments in policy making and basin planning. Coordination between water management and land use are positively incentivised through RBAs loans to local governments.

France is divided into six major river basin areas as water management administrative districts. Each district has a decision-making authority in the form of a basin committee, as well as a water management secretariat to support the committee. The basin committee sets “basic guidelines for water development and management”. The basin plans include general action plans for conserving surface water, groundwater, water-related ecosystems and wetlands. The French Water Act, 1992, stipulates that local entities are required to form water-related local alliances with the basin agencies, which enables local water management groups to participate in consultative processes.

River basin management in France has been regarded as a successful system because of the roles of the RBAs, RBCs and local government.

At central government level, and as a response to implement the EU-WFD, the French National Agency for Water and Aquatic Environments (ONEMA) was created in 2006 under the authority of the Ministry of Environment (now the French Biodiversity Agency). ONEMA is mandated to improve the links between the water cycle and water services management. It also works to better align European guidelines with decentralised implementation at basin scale (Colon et al., 2018).

A most significant feature of the French water management system was to transfer political, administrative and financial power from the centre to river basin levels. It is somewhat of a paradox, that France - with a long tradition of strong central government powers - took a pathway on strong decentralisation of water management at river basin and local scales since the 1960s. The complex and dynamic political situations of the time paved the way for the central government to allow river basin organisations to levy and collect water taxes within the river basins (Barraqué, 2003).

Another distinctive feature of RBAs in France is that they have served as a mutual bank to provide loans to local governments in case local governments need to implement water projects. Such a system has produced favourable a relationship between RBAs and local governments, and has achieved effective water management as well as land development (Barraqué, 2003).

Stakeholder engagement has been a critical factor for the establishment and functioning of the RBCs in France. Each of the six basin committees is chaired by an elected local official and made up of representatives from: local authorities (40% of seats); users and associations, including industries, regional developers, farmers, fishermen, tourism and nautical activities, electricity producers and water suppliers (40%); and central government (20%). As members of the basin committee, these stakeholders orientate the water policy priorities in their respective river basin. See Box 4.2 for an example of stakeholder participation in the Loire-Bretagne basin.

A core feature of the RBAs is to prepare a mandatory master basin plan for water development and management, which is then approved by central government. The RBCs are responsible for monitoring implementation of the master plan. They also formulate the priorities of each RBA, in particular regarding tax levies. The RBC votes on the water agency’s multi-year action programme, which sets the priorities and methods for financial assistance to fund the implementation of the river basin master plan. At the sub-basin level, local water commissions are set up in certain cases to develop a water development and management plan that aims to adapt the basin master plan to local specificities. These commissions are composed of representatives of local authorities (50%), water users (25%) and central government (25%) (Colon, et al., 2018; OECD, 2015b).

Governing water in England and Wales

Summary: Privatised water supply and sewerage services, and strong independent regulators are what stands out in England and Wales. Stakeholder engagement has played an increasingly important role in both water services and river basin management. The development of a catchment-based approach is a more recent development where stakeholder oriented catchment partnerships are established across England and Wales.

Water management in England and Wales has three independent regulatory authorities: the Environment Agency (EA), Drinking Water Inspectorate (DWI) and Water Services Regulation Authority (OFWAT), the economic regulator. The regulators were established at the time of privatisation of water services in 1989, in order to protect the interests of customers and the environment. Integrated water management in river basins is primarily overseen by the EA, working under policy guidance from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). Other distinctive traits are the limited roles of local government which, apart from assistance with the management of urban flooding risks, have little involvement in water management. In the past, stakeholder engagement was less of a priority, but is now integral to shaping and prioritising investment by the water companies, and also in river basin management.

The EA is the lead entity for the implementation of river basin management in England (in Wales the role has passed to the devolved regulator Natural Resources Wales). Ten water supply and sewage treatment companies operate broadly at a river basin scale. The EA is the competent agency to deal with regulation of water supply, water abstractions and pollution, flood risk management and environmental protection. The Agency, however, does not have any mandate to make a final decision on land use and planning; this was the responsibility of the Deputy Prime Minister’s Office and is now with the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. This is a situation that resembles the case in Korea and where there is a need for reform to strengthen the coordination between water management and land use (Lee and Kim, 2009).

A less well developed feature of the water management system in England and Wales set up at the time of privatisation (1989) was stakeholder engagement. Subsequently, the Consumer Council for Water (CCWater) was set up in 2005. CCWater is independent of both the water industry and OFWAT. Since its creation, the Council has become much better known and its influence in support of customers’ interests is now an integral and respected part of the water governance regime.

In its mandate to protect and represent customer needs and to encourage customer engagement, OFWAT, the water and sewage companies and CCWater carry out customer surveys in order to gain a detailed understanding of customers’ needs and priorities. This also includes customer’s willingness to pay for company specific improvements and can lead to improved standards of service where a company demonstrates that particular priorities are of concern. Since 2009, increased operational efficiency by the companies has meant that in real terms, customers’ bills have remained static or have reduced.

The water companies in England and Wales are required to develop a business plan every five years, and their customers are given the opportunity to influence water prices and investment priorities for each planning period. Water companies work to create opportunities for improved local ownership and leadership in water price setting to engage with stakeholders through extensive consultation, and use Customer Challenge Groups to create an informed network of stakeholders able to advise on priorities and preferred standards of service.

The implementation of the EU WFD meant that from 2009, the UK government, the EA and a variety of other organisations have developed a catchment-based approach for integrated basin management. It aims to better engage river catchment stakeholders; establish common ownership of problems and their solutions; build partnerships that balance environmental, economic and social demands; and align funding and actions within river catchments to bring about long-term improvements. The purpose of the new approach is three-fold: i) to generate more coordinated “on the ground” local action; ii) to generate more evidence to better understand and obtain buy-in to problems; and iii) to look for innovative, more cost-effective solutions.

Following a 12-month pilot phase in 2012, a formal independent evaluation of the 25 catchment scale trials across England was carried out to assess how catchment-level planning and collaboration could better inform planning and delivery of the EU WFD. The UK government formally announced the launch of the catchment-based approach in June 2013. Since then, the EA has worked with public, private and not-for-profit sectors to set up over 100 collaborative “catchment partnerships” in the 87 management catchments across England (plus 6 cross-border catchments with Scotland and Wales). The EA now employs over 60 dedicated “catchment co-ordinators” to support these independently-led groups and enhance engagement and partnerships for effective catchment governance across England. A Guide for Catchment Management has also been developed as a “how to” handbook to translate lessons learnt from the pilot phase into useful guidance and reference materials (UK Environment Agency et al., 2018). A national support group was also established to help transition and mainstream the approach in England (OECD, 2015c).

Governing water quality in the Netherlands

Summary: River basin management in the Netherlands puts strong emphasis on the integration of policies and plans as a means to overcome fragmentation. A particular focus of river basin management in the Netherlands is on improving water quality. Basin water quality plans coordinate with the plans of other government agencies also responsible for water quality. The planning of water quality at basin level also coordinates with the Dutch Delta approach – a national programme that aims to protect the Netherlands against flooding and to ensure freshwater supply, now and in the future. Stakeholder engagement is considered key for effective coordination.

In the Netherlands a number of key plans for water management are based on a river-basin approach. Managing water at the basin scale is considered a joint task where the government, water boards, provinces, municipal councils, the governing body of protected sites (Rijkswaterstaat), non-governmental organisations and companies are working together with similar ambitions in mind to improve water management.

A key milestone was the adoption of the river basin management plans 2016-2021 for the Rhine, Meuse, Scheldt and Ems in December 2015. These plans are about water quality and form part of the requirements to meet good water quality status under the EU-WFD. They provide direction on how to reduce water pollution, with the specific objective to improve the quality of the water in both a chemical and an ecological sense.

The case in the Netherlands illustrates a strong requirement for coordination between plans and policies. The river basin management plans provide an overview of the condition, problems, objectives and measures related to the improvement of water quality. Importantly, the river basin management plans are not isolated plans, but are interconnected with the plans and measures of water managers, and other water-related plans and regulations. Many government agencies in the Netherlands work on water quality, providing an imperative to coordinate the river basin management plans with the water plans of other government bodies.

The characteristics of the river basin management plans in the Netherlands are summarised as follows (Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment, 2016):

Integrated approach: the plans comprise all aspects of water quality

Applies to surface water, groundwater and protected areas

River basin approach: plans are drafted for each river basin (Rhine, Meuse, Scheldt, Ems) with both an international/transboundary part (part A) and a national part (part B)

Member states within a river basin hold each other accountable for objectives and measures

Describes objectives, loads, condition, measures and costs

Starting point: attainable and affordable measures

Detailed programme of measures: progress of implementation in past period (2010-2015), measures for the next period (2016-2021) and tasks remaining after 2021

Where possible, measures must be linked to measures from the Dutch Delta Programme and other policy challenges

Coordination with other bodies by means of a bottom-up approach with own role for the regions. Key role for Regional Administrative Consultation Committees, and

International coordination: all EU member states draft river basin management plans and report on progress to the EU.

4.3.4. Possible approaches to river basin management in Korea

The WELF nexus approach (see Introduction to the report for a summary) is a new concept in Korea and under development. Its increased use and meaningfulness would require that there is a common understanding of the concept among key stakeholders, especially ME, MoLIT, MoTIE and MAFRA, but also by local governments, water users, NGOs and other stakeholders. A common understanding of the nexus approach and its potential benefits, limitations and priorities in the Korean context is required for the concept to take a firm root and be perceived as making a contribution to improved coordinated water management. Considering that ministries such as MAFRA and MoTIE seem to be less interested in adapting their work to nexus approach is a particular concern.

In the context of WELF nexus approach, and as part of strengthening basin level management, it is proposed that ME and MoLIT focus on water and land use interactions, including different economic water and land uses such as food and energy production (under the remit of MAFRA and MoTIE). An opportunity for ME is to build a strong case for making environmental flows part of the nexus approach. Considering ME’s agenda to secure environmental flows in the four river basins and new a prototype of low impact development, environmental sustainability needs to be made a significant part of the nexus approach. Therefore, from the ME perspective, the nexus should put strong focus on water, land and ecosystems. Various economic uses of water and land can be integrated into this framework.

Addressing nexus and governance challenges at the basin scale cannot be the responsibility of a single ministry. The improved coordination between sectors related to the WELF nexus will require a broader set of policy options found in a mix of water governance, infrastructure and technology, and investment and funding. It will require a whole-of-government approach to take co-ordinated action at central, basin and local levels. As such, further assessment to address the aforementioned institutional challenges would justify a more systematic and in-depth analysis that would bring together all ministries involved in water management – particularly MoLIT, ME, MAFRA, MoI and MoTIE – in a coordinated approach.

For improved coordination, it is required that ME assesses the institutional mandates to identify overlaps, and management and economic efficiency opportunities at the basin scale for improved coordination among the River Basin Management Committees; River Basin Environmental Offices; Regional Environmental Offices; and the newly acquired Flood Control Offices and River Adjustment Councils in each of the four major river basins. Similarly, MoLIT should undertake a similar type of nexus coordination assessment to identify weaknesses and opportunities for improved coordination of land and water management related to the five regional Construction Management Offices. A basin level assessment can provide a basis for a dialogue between ME, MoLIT, MAFRA and other government and non-government stakeholders (including NGOs, private sector, academia, regional and local governments, etc.) to put in place a coordination platform between water and land management.

An important required policy change, and that cuts straight to the functionality of river basin organisations, is to acknowledge the basin management principle of: Each water basin is different and comes with their own hydrological and socio-economic characteristics and challenges. The very essence of basin management is that such unique characteristics need to be taken into account in the planning and implementation of river basin management plans. Consequently, a successful set up of river basin organisation requires that they can make their own independent decisions (albeit in line with national water priorities) on: long- and short-term plans, levying of water user fees, investment priorities, mechanisms for stakeholder consultation, and dialogue and conflict mediation.

The OECD recommends that the RBCs, under ME, gradually take on typical features of river basin organisation roles and responsibilities related to: planning, data collection, conflict mediation, setting water user fees, and provide mechanisms for stakeholder engagement. It would be beneficial to merge the River Management Committees (RMCs) with RBCs for a combined basin organisation for water management. See Box 4.1 for requirements for successful water management at basin level. The steps below outline a longer-term iterative approach. ME should retain ongoing oversight and delivery of RBCs and facilitate learning from experience. ME should also provide process guidance to RBCs to ensure alignment with national policy priorities, and to ensure that basin plans are implemented consistently across the different basins and the people are being treated fairly.

1. Start reflecting basin issues in national policies, even before ME sets the institutional framework to shift towards river basin management. This requires data collection and information on basin features, the capacity to reflect these features in national policies, and stakeholder engagement to signal local priorities and strengthen political buy in.

2. Mandate RBCs to develop river basin management plans. Based on the national long-term water plan and national water management principles, the RBCs in Korea should be mandated to develop river basin management plans (RBMPs). Considering that there is a big vertical coordination gap between central and local levels in Korea, RBMPs are one important step, as an intermediary institution, towards operationalising water policies, basic water management principles, and new concepts such as the WELF nexus approach. The RBMP can for example include: an appraisal and evaluation of water resources and their condition and trends; an analysis of community needs; alignment with broad policy objectives for the basin or catchment (typically in terms of economic development); coordination with land use, agriculture, food and energy supply policy; setting sub-catchment goals and implementation guidelines; details of cost-sharing programs for on-ground works and other actions; details of a monitoring program; and description and analysis of special catchment management issues, areas and management techniques. All other plans at the basin level (e.g. land use and spatial plans, transport plans and energy plans) should take heed to the RBMP; the RBMP in each basin should drive smart investments that contribute to the delivery of water objectives and minimise exposure to water-related risks. ME should ensure that updates of plans are done in consultation with relevant government and non-government stakeholders, and lessons learned are incorporated into future plans.

3. Empower RBCs to mediate conflicts. The RBCs would be one appropriate level for mediating conflicts along the basin (see section 1.1.4 for example of basin conflicts), with potential impacts to set precedence and to better support local governments to mediate conflicts at local scales. Currently, many water conflicts end up with the central government, creating inefficiencies and unnecessary transaction costs. Conflict mediation is better done at the basin or sub-basin scale. The central government should only deal with conflict mediation in case it is of national importance and in terms of developing appropriate policies.

4. Gradually devolve decisions on water use charges to RBCs. RMCs and RBCs are currently not independent entities, and water user charges are decided by central government through the RMCs. Considering Korea’s strong policy on “water equity”, initial reform change can be to allow fee variation in between a band-width of fixed lower and upper rates set by ME. The lower rate could be set at today’s level (more out of simplicity than anything else) and the upper level should clearly allow for a significant shift towards the promotion of more efficient use and management of water, differentiated by local water risks and the accepted level of risk. In case required, measures can be put in place to support poor water users and to compensate upstream users affected by economic restrictions due to water quality protection or water conservation.

5. Give RBCs responsibility for the planning of water supply, water quality and flood protection. The OECD recommends that ME, MoLIT, MAFRA and other relevant ministries explore an initial joint coordination mechanism at the basin level for coordinated decision-making in water quality and quantity projects (currently a lot of overlaps). Such a mechanism should also allow for stakeholder engagement. The current Integrated Water Management Forum (under ME) could serve as an initial step to strengthen water management at the basin scale. Some of the required steps that need to be taken include:

i. Establish a common vision for integrated water management and WELF nexus at basin scale based on policy directions (basin management core values of integration, and basic principles and systems, such as a mandate to develop basin plans, and stakeholder engagement);

ii. Establish clear objectives and strategies for achieving the established vision on managing water at the basin scale; and

iii. Develop and propose an institutional design at the basin level (such as through RBCs), including stakeholder engagement platform, roles and responsibilities, along with investment priorities and policy directions to advance on managing water at the basin scale.

6. Establish a stakeholder engagement platform for each river basin. Government and non-government engagement will be a critical element as part of operationalising an expanded role of RBCs. Stakeholder engagement will be key to developing RBMPs, but also in terms of having a voice in matters pertaining to conflict mediation, the setting of user fees and data collection. The OECD recommends that ME continue to develop stakeholder approaches in relation to its nexus work and under the existing institutional set up. A starting point is to assess and analyse the role and current mandate of the four RBCs, vertical and horizontal policy linkages, and use the assessment as a basis for how to move forward. Such a review should at least include and analysis of water and land use linkages with local governments, MoLIT and MAFRA. For example, the French case suggests that a financial link between local governments and basin organisation is key for improved coordination of water and land use decisions. If RBCs are mandated to independently use revenue generated from water use charges, they could potentially use part of the revenue to incentivise (through locally driven water investment demands) better coordination between basin and local levels.

Box 4.1. Some requirements for successful river basin management

Research and data collection at the basin scale to better understand the hydrology, environmental, climatological and the socio-economic dynamics for informed decision-making.

Clear division of roles and responsibilities at all levels of management and that various government and non-government actors can be held to account. A river basin entity needs to be endowed with a very clear mandate and a certain level of independence is required from central government.

Stakeholder buy-in and inclusiveness in the development of water policies and basin plans for enhanced policy relevance and better implementation efficiency.

Transparency in planning and policy processes and access to information. All stakeholders should be able to access similar data and information for informed decision-making.

Establishment of a long-term river basin management plan that is the outcome of diverse stakeholder engagement around the basin. The plan should cover the entire river basin, including medium and small scale watersheds. In addition, river basin management needs a clear purpose and a systematic approach.

Consideration of the needs and demands from different sectors (such as agriculture, energy, urban development, environmental flow, industry, etc.) and the costs involved.

Financial viability and adequate staff capacities to fulfil the mandate of the river basin organisation. Entirely new capacities may be required to cater for multi-stakeholder engagement and to improve coordination at the basin scale. Financing should be based on economic principles such as appropriate water tariffs, taxes and/or transfers. River basin organisations may levy water charges as a means to secure their own financial viability.

Sources: OECD (2015a), OECD Principles on Water Governance, OECD, Paris. http://www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy/OECD-Principles-on-Water-Governance.pdf; Pegram, G. et al. (2013), River Basin Planning: Principles, procedures and approaches for strategic basin planning. Paris, UNESCO.

The gradual development of RBCs will require some initial investment from ME to enhance certain capacities, for example, skills related to water planning and stakeholder engagement, investments and fee systems. However, it is envisaged that in the long-term, RBCs will be funded through water user fees and build their own sustainable financing base to be able to deliver on those roles and responsibilities mandated to the RBCs. This increased independence can favour RBCs devolution of responsibilities and capacitate RBCs to deliver on new proposed mandates of river basin planning, data collection, conflict mediation and establishing and implementing stakeholder platforms. Increasing financial self-sufficiency can also lead to improved accountability of new responsibilities. However, it is important to be aware of that this type of funding modality also can lead to economic distortions and inefficiencies; earmarking can be an inefficient use of public money for several reasons (OECD, 2017c). Hence, it is critical that financial viability and efficiencies are assessed and monitored on regular basis by ME, and expenditures should be commensurate with the revenue collected so stakeholders see the benefit.

4.4. Stakeholder engagement

A stakeholder refers to an individual, group, or organisation that has a direct or indirect interest or stake in a particular organisation. These may be governments, private or public sectors, research institutions, and civil society such as Non-Government Organisations (NGOs). In Korea, stakeholder engagement platforms could prove helpful networks for communication on, and management of, competing demands for water, managing coordination problems and conflicts, coalition-building, and planning and visioning.

Stakeholder engagement in water management is a means to an end. Various stakeholders’ participation in policy development and implementation, and access to relevant water information are essential preconditions for successful water resources management and water policy reform. Stakeholder engagement is conducive to improved water management because it enables water management to be better balanced among water users, and that water management policies and plans better reflect various interests and knowledge of society and be tailored according to local needs and demands. There are several mechanisms through which stakeholder needs, demands and knowledge can be made known to decision-makers. For example, stakeholders being part of various water committees and boards, and public hearings. For any engagement mechanism chosen, it is critical that it is inclusive and transparent, and provide a space where stakeholders can be heard in constructive ways.

The water sector in many OECD and non-OECD countries is experiencing a movement towards more formalised and structured forms of stakeholder engagement, going beyond reactive ad hoc approaches. New legislations, guidelines and standards at various levels related to public participation and stakeholder involvement have spurred the emergence of more formalised versions of stakeholder engagement. Organisations are referring to such engagement in their overarching principles and policy. Increasingly, either because of legal requirements or on a voluntary basis, public authorities, service providers, regulators, basin organisations and donors have included requirements for co-operation, consultation or awareness-raising in their operational rules and procedures (OECD, 2015b).

Some of the benefits of a formalised and structured form of stakeholder engagement are reflected in the Dutch Delta programme, created in 2010. Stakeholder engagement within this programme has, for example, led to a new working method in three areas: flood risk management, the availability of freshwater and water-robust spatial planning. The Delta Commissioner is required by law to submit a yearly proposal for action to the Cabinet, in consultation with the relevant authorities, social organisations and the business community (OECD, 2015b). This case can be illustrative for Korea in the sense that it shows that stakeholders can be involved in different water management issues and that there are many potential benefits of engaging long term with stakeholders. In fact, the establishment of stakeholder engagement may take time since stakeholders may lack experience and capacity, and there may also be distrust between some stakeholders that will require dialogue and trust-building. Some of the benefits of stakeholder engagement may not be immediately visible, but may pay off at later stage.

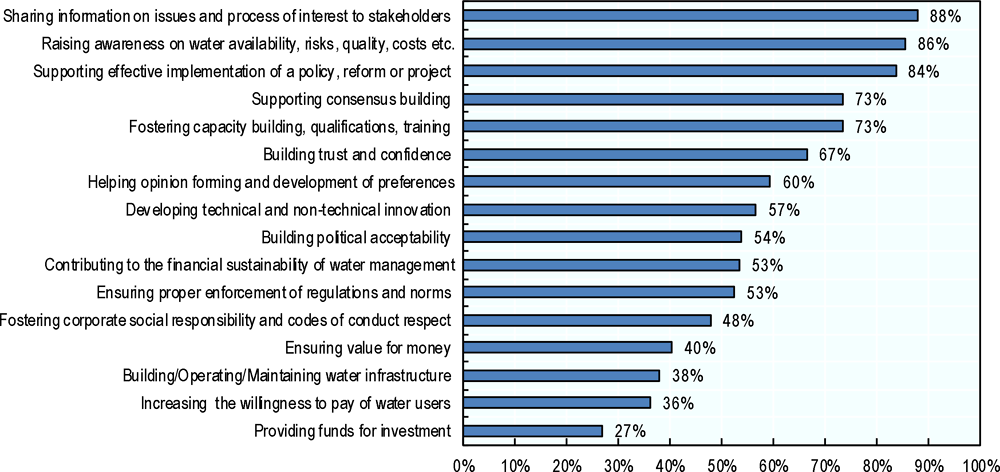

Stakeholders contribute to water governance in different ways and can pursue different objectives. The OECD Survey on Stakeholder Engagement for Effective Water Governance (OECD, 2015b) indicates that stakeholders’ contribution to better governance covers a variety of activities (Figure 4.1). The most common are that stakeholder engagement: contributes to information sharing (88% of respondents surveyed); raises awareness on water availability, risks, quality and costs (86%); and supports the effective implementation of water policy, reform or projects (84%).

Figure 4.1. How stakeholders contribute to better water governance

Source: OECD (2015b), Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Water Governance, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264231122-en.

In most water reforms in OECD and non-OECD countries, stakeholder engagement has been, and is considered to be, one important reform element. The EU WFD integrates engagement by relevant water stakeholders. The current development of EU Drinking Water Directive views communication with the public and engagement by relevant stakeholders as a key reform element.

Shifting from an ad-hoc based to a structured form (i.e. as stipulated by legislation, rules and regulations) of stakeholder engagement raises some challenges for decision makers. Formalising, or even institutionalising, collective decision-making related to water issues – such as for example as the French river basin management system - requires strong political leadership, with clear objectives and strategies (such as to prevent capture of engagement processes). It also implies investments to secure financial and human resources at the appropriate levels to sustain the engagement process. Appropriate skills are necessary to set up and facilitate the process for formal stakeholder engagement and to ensure its expected outcomes. This requires dedicated staff trained in mediation, communication, use of information and communication technologies (OECD, 2015b).

The Loire-Bretagne Basin Agency in France illustrates how stakeholders can be engaged in the development of a river basin management plan (Box 4.2). It is worth noting that in the French case, stakeholders can be engaged in two main ways: i) through being a member of the basin committee; and/or ii) through taking part in particular stakeholder consultation processes. It shows how stakeholder engagement can benefit the content and relevance of river basin planning, as well as its implementation.

Box 4.2. Stakeholder involvement in the development of a river basin master plan: The example of the Loire-Bretagne basin in France

In France, as required by the EU WFD (see Annex 3.A), a master basin plan is developed in each of the six river basins. Each plan defines water quality and quantity objectives, and actions to be carried out for achieving them. The basin master plans are updated every six years.

The relevant stakeholders are involved in the development of the basin master plans in two main ways: first, as being part of the basin committee; and second, during a consultation process organised within the basin.

Each river basin in France has a committee which is responsible for the development of the basin master plan. The committee is the pivotal place for discussing and collectively defining the keys points of the water policy within the river basin. A basin committee functions as a multi-stakeholder assembly that represents and mediates different interests along the basin. For instance, the Loire-Bretagne basin committee (one of the six French basin committees) is made up of 190 members appointed for six years. Out of these, 40% are elected representatives, mainly from local governments, and also from regional and county governments. Another 40% of the members are water user representatives, such as industries, farming, angling and environmental NGO’s. The last 20% is made up of state representatives (public and administrative central state bodies at decentralised levels).

The development of the master basin plan can, at times, be a hard process. For instance, in the Loire-Bretagne basin, the basin master plan in force was developed over a two-year period. The process itself required many meetings and debates, and sometimes even in the form of conflicts between stakeholders. More than 20 meetings of the thematic commissions (“planning”, “seashore” and “communication”) of the basin committee were necessary for reaching a compromise, and at the end getting an approval from the committee.

Stakeholders are also involved through a consultation process that takes place a few months before the final approval of a river basin plan. The basin committee makes a formal notice to local stakeholders to get their inputs on a draft of the basin master plan. The objectives are to strengthen the technical content of the plan, and to foster their buy-in and their future engagement in the implementation phase. During a four-month period, various local stakeholders can contribute to the consultation process, such as regional councils, county councils, chambers of agriculture (regional and county levels), chambers of commerce and industry (regional and county levels), management bodies of natural parks, sub-basin commissions, etc. During the consultation process, any relevant publications and other materials are made accessible to involved stakeholders. Moreover, they can also get technical support from state and basin agency services through local meeting participation.

In the Loire-Bretagne basin, about 260 local stakeholder bodies were consulted in the drafting phase the current basin master plan, and 3000 comments were made on its content. Every comment was analysed and their potential inclusion arbitrated by the thematic commissions of the basin committee. Some comments were taken into account, such as requests for clarifications, the need for greater relevance of stakeholder data, and suggestions of financial and technical feasibility issues that were not initially identified. Other comments did not lead to a change, specifically when comments were not precise enough and/or justified.

Examples of comments from the stakeholder consultation process on the master river basin plan of the Loire-Bretagne basin include:

Request that some high-priority areas be extended, reduced or suppressed. This can, for example, be relevant for lakes subject to eutrophication, erosion sensitive areas and abstraction sensitive areas.

Request to change some of the proposed technical standards, for example value of pluvial network flow, filling period of irrigation reserves, and yield of drinking water networks in rural area, and

Request for additional clarifications and details on technical terms, such as biological minimum flow and water economic values to avoid misinterpretation.

Source: Hervé Gilliard, Pers. Comm., Peer Reviewer, Loire-Bretagne Water Agency.

4.4.1. Non-government stakeholder engagement in Korea

During the 1990s and 2000s, Korea witnessed a changing civil society. The challenge of civil society is to increasingly become a key part of “co-governance” as an engaged and informed partner to the government. It is reported that civil society has become a stronger social force with increasing abilities of getting involved in, and influencing, government decision-making processes (Kim, 2013).

A number of environmentally oriented NGOs in Korea work to influence government and/or monitor environmental situations, including water, and to inform and educate the public. Large NGOs such as the Korean Federation for Environmental Movement have built up considerable competencies in the field of environmental policy, while smaller NGOs have focused on water service provision. Consumer associations (e.g. Korea Consumer Agency, Green Consumer Agency) are also important actors with a voice in consultative platforms such as the Water Tariff Committee, River Water Adjustment Councils, as well as local price committees. Academia also plays an important role to produce and share technical and scientific information and evidence to build a sound knowledge-base in support of the formulation of policies and practices (OECD, 2017b). Water and environmental NGOs work, among other things, includes monitoring of water quantity and quality issues, restoring wetlands and initiating river restoration projects, and informing and educating the public. They do their best to feed into policy processes by sending reports and other documents to government agencies, and by trying to draw public attention to harmful practices.

A water reform ambition in Korea is to engage more with stakeholder groups in water. Stakeholder engagement processes in Korea have been ad hoc and reactive, rather than being aimed at prevention and long-term resilience. They tend to be a response to a particular water need, crisis or emergency (droughts, floods, economic crisis, river restoration etc.), rather than a process carried out on a voluntary basis. Efforts are required to develop more systematic stakeholder engagement in decision making, including clear objectives for the engagement process, in order to more systematically integrate stakeholder interests and knowledge into water management.

One objective is to integrate stakeholder engagement under the RBCs in Korea. For this reason, a one-year project was recently set up in the Han River to test and promote stakeholder engagement. The River Basin Participation Centre is meant to promote improved water management, including principles for fund management. The Centre is mainly meant to improve planning at the sub-basin level and to seek alignment with the Han River Basin long-term management plan. Planning is not mandatory for medium and small scale rivers, resulting in only 10 % of them having water management plans.

In the follow-up of the pilot Han River Basin Participation Centre, it is critical the ME undertakes an assessment. It should assess experiences and lessons learned, through a survey with the various engaged stakeholders on their experiences, and explore ways in how they can and are willing to participate. It is important that these types of pilots are properly assessed so that stakeholder engagement mechanisms can evolve.

Despite trends of a more vivid and influential civil society, progress is at a slow pace in relation to the water sector. Challenges faced by water related NGOs and other non- state stakeholders in Korea include:

The lack of institutionalised stakeholder platforms and process whereby they can dialogue directly with the relevant decision-makers. This is considered as a major hindrance that leave many NGOs frustrated and without any clear channels for their voices. The experience so far with stakeholder engagement is to consult stakeholders in some specific projects, often related to river restoration.

Limited experiences within NGOs as well as the government system of working with water management at the basin scale. The RBCs under ME are mandated to manage the river management funds raised through the water user charges. The RBCs are currently not mandated to making planning and decision-making on water management.

There is overall an awareness and information gap among the Korean population about water management, which is mainly due to lack of information. The country has made efforts to open up public data, most recently with its “Government 3.0., which is an e-platform for government operation to deliver customised public services by opening and sharing government-owned data to the public and encouraging communication and collaboration between government departments. Government 3.0 aims to make the government more service-oriented, competent, and transparent (http://www.mois.go.kr/eng/sub/a03/Government30/screen.do). However, such tools may take time to implement, and information on water is for the time being limited, making water users and consumers less aware of the costs of water management and water pricing, sources of supply, and water quality and flood risks. Better informed water users and consumers should be seen as an important asset, since it makes them more aware to reduce their own water footprint, and to improve their willingness to comply with legislation or to pay for certain water services.

Efforts by NGOs tend to be fragmented and piece-meal partly due to the lack of plans for medium and smaller scale basins (only 10% of them have plans). NGOs base their work on the water plans, but the long term plans by MoLIT and ME need to be operationalised to a higher degree.

4.4.2. Moving forward: Towards increased non-state stakeholder engagement

Relevant ministries, such as ME, MoLIT and MAFRA, should start to build longer-term stakeholder engagement platforms as part of strengthening water management, including basin level management. While most water and environmental related NGOs in Korea are currently operating at a basic level, such platforms will help the NGOs to gradually build their capacities and experiences. Table 4.2 on OECD Principles on Stakeholder Engagement suggests a number of steps that would be important to apply for more effective stakeholder engagement.

Table 4.2. OECD Principles on stakeholder engagement in water governance

|

Principle |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Inclusiveness and equity |

Map all stakeholders who have a stake in the outcome or that are likely to be affected, as well as their responsibility, core motivations and interactions |

|

Clarity of goals, transparency and accountability |

Define the ultimate line of decision making, the objectives of stakeholder engagement and the expected use of inputs |

|

Capacity and information |

Allocate proper financial and human resources and share needed information for results-oriented stakeholder engagement |

|

Efficiency and effectiveness |

Regularly assess the process and outcomes of stakeholder engagement to learn, adjust and improve accordingly |

|

Institutionalisation, structuring and integration |

Embed engagement processes in clear legal and policy frameworks, organisational structures/principles and responsible authorities |

|

Adaptiveness |

Customise the type and level of engagement as needed and keep the process flexible to changing circumstances |

Source: OECD (2015b), Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Water Governance, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris.

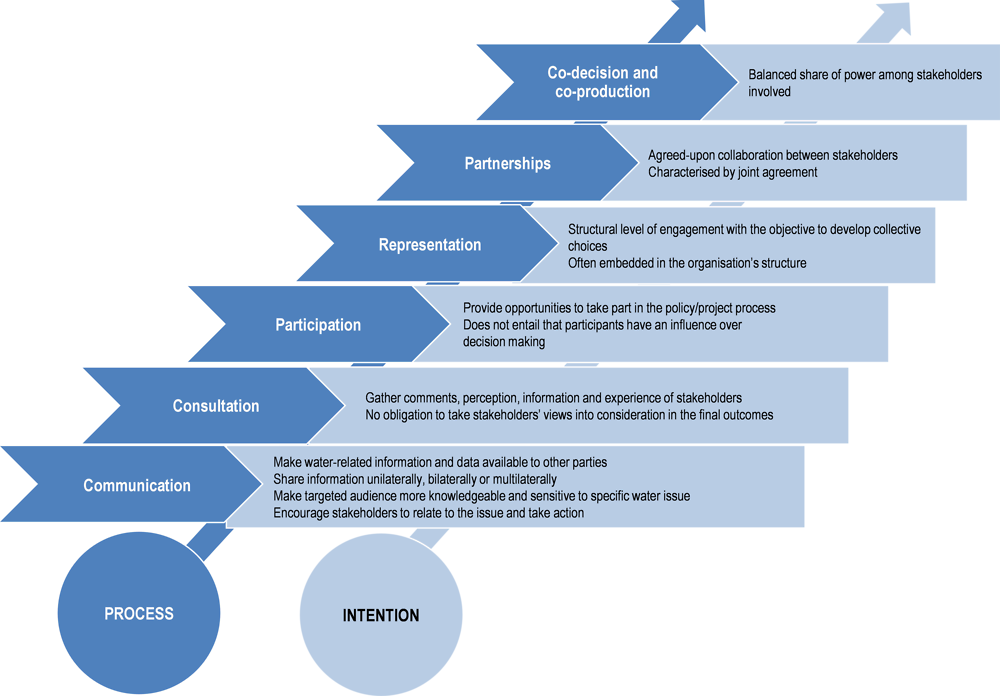

Six levels of stakeholder engagement have been distinguished depending on the processes and purpose of engagement (OECD, 2015b) (Figure 4.2). As a start, ME, MoLIT and MAFRA need to strategically assess the type of engagement required. For ME, one question to be posed is how stakeholders can be better engaged to advance on water quality and quantity management and to improve compliance with existing water rules and regulations.

The first level is communication, which intends primarily to share information and raise awareness, but implies that engagement is mostly passive, i.e. stakeholders are provided with information related to water quality and quantity policy and projects, but not necessarily with the opportunity to influence final decisions. The typology incrementally progresses up to the level of co-production and co-decision, which correspond to deepened decision-making where stakeholders exercise direct authority over the decisions taken. Stakeholder engagement is a multi-faceted exercise with various progressive levels that imply different forms and intensity of stakeholder engagement.

Figure 4.2. Levels of stakeholder engagement

Source: OECD (2015b), Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Water Governance, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264231122-en.

Below follows examples of stakeholder engagement that illustrate different ways on engagement. The cases are meant to provide examples of strategies and methods used to provide inspiration to ME and other ministries. The full case studies are presented as Annex 4.A. It is important that ME assesses and sets stakeholder engagement objectives in relation to river basin management and the management of the WELF nexus.

In the Netherlands, many citizens were perceived to lack capacity and interest to engage in water issues. A survey was carried out specifically targeting citizens to assess their knowledge on water, their positions regarding certain water issues and their willingness to participate further in decision-making. In Portugal the “Water Heroes” programme increased water awareness and spurred students to do research to encourage innovation, originality and applicability.

These cases illustrate that the assessment of stakeholders’ willingness and capacity to participate at the basin level could be a useful starting point for ME. Since most environmental NGOs in Korea operate with capacity limitations, it is important that ME surveys the stakeholders and their interests and capacities. As a first step, it is recommended that ME (and MoLIT and MAFRA) provide some incentives in the form of small grants (travel grants, grants for holding local stakeholder meetings, trainings etc.) for which NGOs can apply to improve their abilities and capacities to take part in stakeholder processes. Trainings and capacity development on stakeholder engagement will be required for ME staff and stakeholder groups. Engaging with non-conventional stakeholders, such as with youth, can be a useful means to spur innovation and interest for water.

Stakeholder engagement processes under the EU-WFD provides clear guidance on important elements Korea can apply in a stakeholder engagement process, including how to engage with stakeholders, for what purpose, avoidance of too technical information, time-bound processes, drawing the attention of all interested groups and individuals, being open-minded in analysing the results, and providing clear rationale for why and how a certain decision is made.

In Spain, stakeholder engagement was a strong element in reaching consensus on key water decisions and achieving good water quality status in the Mancha Oriental water body, Júcar Basin. Stakeholder engagement also led to the adoption of a new water management plan. In Germany, the state of Baden-Württemberg took measures to involve the key stakeholders through a series of over 70 different local events to produce a water plan. These cases show how stakeholders were engaged in the development of river basin management plans, and that engagement can be both ad hoc and by law. It also shows that sometimes a series of different types of events (consultations, workshops, public hearings, public exhibitions, etc.) may be required as a strategy to engage with different types of stakeholders. In Korea, it is important that long-term plans are properly consulted with the stakeholders. As mentioned in the German case, the level of public acceptance was high and something that most likely made the implementation of the plan more effective. ME can consult with stakeholders on existing long-term plans to check their viability from stakeholder perspectives as part of their renewal.

In the Durance Valley, France, the objective of stakeholder engagement was to optimise water allocation between energy generation and irrigation, and to develop appropriate incentives for water savings to restore financial margins and to answer future water demands. This case illustrates two important items which may also benefit Korea. First, stakeholder engagement was beneficial for coordinating complex nexus issues on water, energy and agriculture. The solution in this case was with the private electricity company and the farmers, and was not something that the government could have designed alone; it was enabled through a river basin management collaboration platform. Second, it illustrates a non-uniform and iterative river basin management approach. Diversified management based on river basin conditions can in fact be a very good way of stimulating innovation that can spread along a basin or even between basins.

In the South Saskatchewan River Basin, Canada, stakeholder engagement assisted with addressing adaptation to climate change, also an increasing challenge in Korea. Stakeholder engagement was conducted on a voluntary basis, and was supported by mechanisms such as collaborative modelling processes, and using sophisticated simulation for modelling water systems.

The case studies show that there can be multiple ways to engage with stakeholders depending on the objectives and type of stakeholders. For example, processes can range from being voluntary and ad hoc, to systematically structured and required by law such as under the EU-WFD, or under the French river basin agencies (see Box 4.2). Importantly, one modality does not exclude another, and it is important to design stakeholder processes according to their purposes. A viable engagement strategy can also be to work with different types of stakeholder engagement methodologies for different types of stakeholders, such as consultations, workshops, public hearings and public exhibitions.

For ME, it is important to develop a clear strategic long-term stakeholder engagement strategy, particularly with regard to non-government stakeholders and other key WELF nexus-related ministries (MoLIT, MAFRA and MoTIE). While stakeholder engagement is yet to be better structured in Korea, the ME can start by assessing the options for a multi-stakeholder, inter-ministerial mechanism for the WELF nexus at national level. Simultaneously, various stakeholder platform options should be assessed for the RBCs, with a clear purpose to advance on planning at the basin scale. To support this endeavour, it is recommended that ME organise a set of national and basin level workshops on the WELF nexus to collect views and ideas from various stakeholder groups as guidance for moving forward.

References

Barraqué, B. (2003), Past and future sustainability of water policies in Europe, in Natural Resources Forum, 27: pp 200–211.

Colon, M., S. Richard and P.A. Roche (2018), The evolution of water governance in France from the 1960’s: Disputes as major drivers for radical changes within a consensual framework, Water International, 43/1, pp. 109-132 https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2018.1403013.

European Commission (2003), Common Implementation Strategy for the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC), Guidance Document No 8, Public Participation in Relation to the Water Framework Directive, Working Group 2.9 – Public Participation, European Communities, Luxembourg.

Kim, H-R (2013), State-centric to Contested Social Governance in Korea: Shifting Power, Routledge Studies on Modern Korea, Routledge, New York.

Lee S. and S. Kim (2009), A new mode of river basin management in South Korea, Water and Environment Journal 23 (2009) p. 91-99.

Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment (2016), River basin management plans 2016-2021 of the Netherlands, The Hague, The Netherlands.