Australia's economy has undergone steady growth and a general decoupling of environmental pressures. This chapter reviews efforts to mainstream environmental considerations into economic policy and promote green growth. It analyses progress in using economic and tax policies to pursue environmental objectives and discusses environmentally harmful subsidies. The chapter examines efforts to scale up measures to promote low-carbon energy and transport infrastructure and support eco-innovation as a source of economic and employment growth. It also reviews progress in mainstreaming environment in development co-operation and trade.

OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Australia 2019

Chapter 3. Towards green growth

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction

The Australian economy is among the world's largest. Since 1992, it has enjoyed steady growth. It withstood the global economic crisis, keeping an average gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of 2.6% over 2007-17. Economic growth is projected to continue at around 3% in 2018/19, supported by strong investment and exports to the growing Asian market (OECD, 2018a). The 25 million inhabitants enjoy high living standards and low unemployment rates. However, continuous economic and population growth is exerting pressure on the environment. As the driest inhabited continent, with settlement primarily on the coasts, Australia is also highly vulnerable to climate change.

Australia has considerable potential to green its economy, building on a wide range of renewable energy sources and strong innovation skills. Since the 2007 OECD Environmental Performance Review, the country has managed to decouple economic growth from the main environmental pressures (Chapter 1; OECD, 2007). The energy mix is gradually shifting to less carbon-intensive fuels and to renewables. However, the economy remains highly reliant on extraction of natural capital. It is among the most resource- and carbon-intensive OECD economies. Although it is using resources more efficiently, there is doubt about the capacity of Australia’s natural capital to continue providing the services required to support the country’s economy and well-being in the longer term.

Framework for sustainable development

Australia’s 2018 report on implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the first voluntary national review on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, identifies successes (e.g. on international co-operation, trade and water) and challenges (e.g. regarding sustainable cities and the needs and aspirations of Indigenous people), and showcases best practices (Chapter 1; DFAT, 2018). Progress is being made on populating the SDGs indicators. However, Australia has not conducted a quantified synthetic analysis of progress nor defined a timeline for implementation. The country could build on the present review to revive and update the 1992 National Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Development.

With some exceptions (e.g. the Infrastructure Plan), environmental concerns are not prominent in major sectoral strategies (e.g. white papers on energy, agricultural competitiveness, foreign policy), and economic interests still tend to dominate decision making (Section 3.4; Chapter 4). The merger of portfolios in the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources and the Department of the Environment and Energy was a positive step to align policies. Australia is a global leader in environmental‑economic accounting and has made progress in adopting a common national approach in this area (Box 3.1; Australian Government, 2018a). Further steps could be undertaken to use these accounts for policy and decision making (Obst, 2017). More broadly, improving environment-related information will help strengthen public trust in environmental policies that are often subject to highly politicised debates.

Box 3.1. Australia is a leader in developing environmental-economic accounts

The System of Environmental-Economic Accounting is an international statistical standard combining economic and environmental data in a framework consistent with the System of National Accounts. It aims to better understand environmental-economic links and to describe stocks of environmental assets and changes in them. Environmental‑economic accounting includes compilation of physical supply and use tables, functional accounts (e.g. on environmental taxation and expenditure) and asset accounts for natural resources.

Since the mid-1990s, Australia has been at the forefront of this work. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) publishes environmental-economic accounts annually. Asset accounts cover land, mineral, energy and timber resources. The ABS also regularly produces water, energy and greenhouse gas (GHG) emission accounts and reports environmental taxes. Experiments on establishing Great Barrier Reef ecosystem accounts and state-level land accounts are under way. Pilot accounts on waste and environmental expenditure were last updated in 2014.

Source: ABS (2018), Australian Environmental-Economic Accounts: 2018, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4655.0.

Greening the system of taxes, charges and prices

Overview

Australia’s fiscal position is sound. Following a large fiscal stimulus during the global economic crisis, the federal deficit was halved to 2% of GDP between 2009 and 2016. The budget is expected to return to balance by 2019, leaving room to absorb shocks, support activity and protect vulnerable households (Australian Government, 2018b). The government is committed to keeping the tax/GDP ratio low. Tax revenue accounted for 28% of GDP in 2015, below the OECD average of 34% (OECD, 2017a).

The tax mix remains geared towards direct taxation. Revenue from taxes on income and profits accounted for 16% of GDP in 2015, twice the share of revenue from taxes on goods and services. The 10% Goods and Services Tax (VAT) is low by international comparison and wide exemptions narrow its base. The Commonwealth collects most tax revenue (79%) and distributes it to the states and territories through transfers that account for about half their revenue.

The structure and levels of environmentally related taxes are not aligned with environmental objectives. Revenue from environmentally related taxes decreased from 2.2% of GDP in 2005 to 1.8% in 2016, though still above the OECD average of 1.6% (Figure 3.1). In real terms, revenue declined until 2011, increased over 2012-13 with the introduction of a carbon tax, then decreased again with its repeal (Box 3.2). Between 2005 and 2016, the share of energy taxation revenue decreased while those of taxes on motor vehicles, transport and waste rose. Overall, the contribution of energy taxes to tax revenue decreased. While the government is taking measures to reduce taxes on labour and investment, shifting the tax mix towards less distortive taxes on consumption, including on energy products, could help support economic growth and tackle climate change (OECD, 2017b).

Figure 3.1. Energy taxes’ contribution to tax revenue has declined

Box 3.2. Overcoming barriers to a carbon pricing mechanism

Australia established a carbon pricing mechanism in 2012 and repealed it in 2014. Liable entities producing over 25 000 tonnes of CO2 per year were required to pay the carbon tax and report their emissions to the Clean Energy Regulator. The mechanism covered about 60% of Australia's carbon emissions, including those from electricity generation and other “stationary energy” sources, landfills, wastewater treatment, industrial processes and fugitive emissions. The tax was introduced at a rate of AUD 23 per tonne of CO2. The government intended to replace the fixed price with an emission trading system from 2015.

The mechanism appeared effective: CO2 emissions from electricity production decreased by 10% over 2012-14. It was repealed due to concerns about electricity prices and competitiveness, but the impact on electricity prices may have been overstated compared with factors such as lack of competition in the electricity market and increasing domestic gas prices. Moreover, there is little empirical evidence of the effect of carbon pricing on competitiveness. After the repeal, CO2 emissions from electricity production rose by 7% over 2014-16.

Successful environmental taxation requires careful assessment of distributional and competitiveness concerns and policies to address them. Trust and communication are critical to public acceptance, as in France, whose Environmental Taxation Committee was influential in introducing a carbon tax in 2014 after unsuccessful attempts in 2000 and 2009.

Source: ACCC (2013), State of the Energy Market 2013; ACCC (2018), Restoring electricity affordability and Australia’s competitive advantage; Arlinghaus, J. (2015), “Impacts of Carbon Prices on Indicators of Competitiveness: A Review of Empirical Findings”; CER (2015), About the carbon pricing mechanism scheme, http://www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/Infohub/CPM/About-the-mechanism; IEA (2018), CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion (database, 2018 preliminary edition); OECD (2016), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: France 2016.

Taxes on energy products and carbon pricing

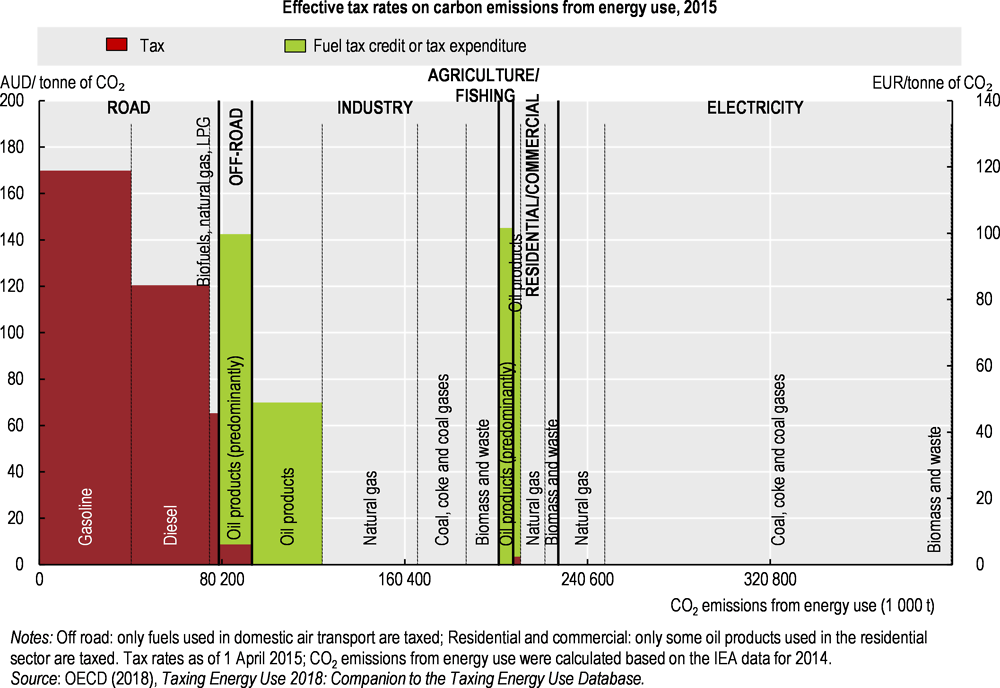

Although taxes on energy products continue to provide the bulk (58%) of revenue from environmentally related taxes, this share is lower than the OECD average of 72%. Its level reflects Australia’s narrow base and low rates of energy taxation. Excise tax applies to natural gas for road use and oil products across all sectors. Yet tax refunds mean fuels are largely untaxed outside of transport. Fuels used to generate electricity benefit from a full rebate on the excise tax paid; coal, which accounts for the majority of energy use and carbon emissions in the sector, is fully untaxed (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Fuels are largely untaxed outside the transport sector

Although revenue from road fuel taxes remained broadly constant in real terms, it declined once the Fuel Tax Credits were taken into account (Section 3.4.1). Since 2014, excise duties on road fuel have been indexed to inflation. Although this was motivated by revenue-raising considerations, it is a positive move to promote fuel savings. However, road fuel taxes do not reflect the environmental costs associated with their use. Although Australia is one of the few OECD countries taxing diesel and petrol at the same nominal rate, diesel is less taxed on a carbon basis (because diesel emits higher levels of CO2 per litre than petrol) (Harding, 2014a). Furthermore, heavy vehicles, mostly diesel-fuelled, benefit from a rebate. This has likely contributed to the increased share of diesel in road fuel consumption (Chapter 1). Effective carbon prices in road transport in Australia are in the lower range for OECD countries (OECD, 2018b).

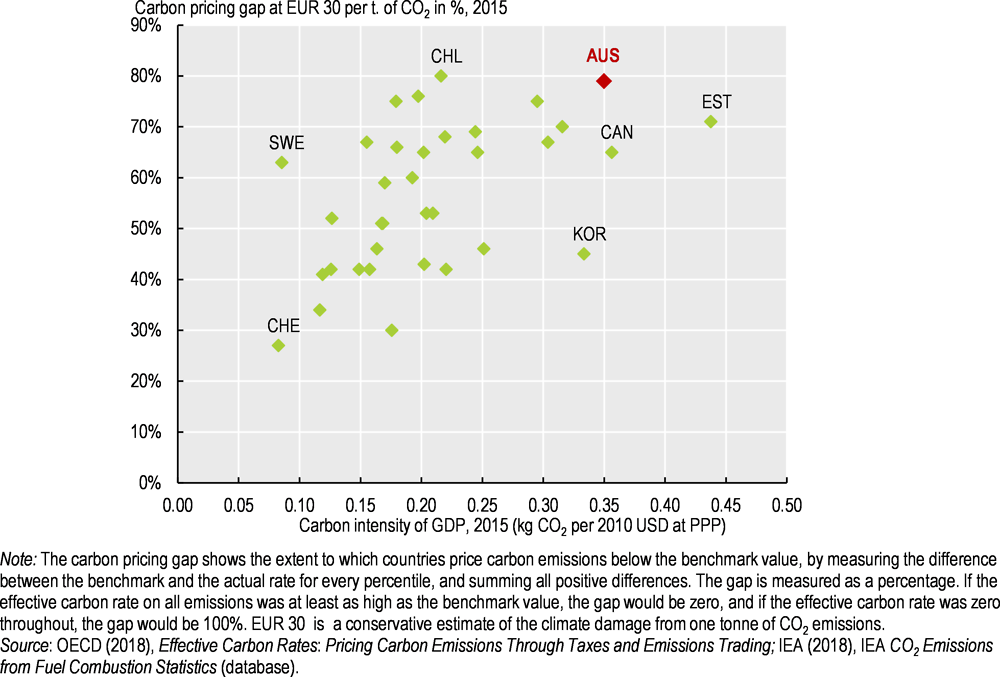

Beyond road transport, energy taxes do not reflect the climate costs of fuel use. In 2015, 77% of carbon emissions from energy use were unpriced and only 20% of emissions were priced above EUR 30 per tonne of CO2 (a conservative estimate of the climate damage from one tonne of CO2 emissions) (OECD, 2018c). Australia has the second highest carbon pricing gap1 in the OECD at EUR 30 per tonne of CO2, highlighting its lag in implementing cost-effective policies to decarbonise the economy (Figure 3.3). At a time when carbon pricing is gaining momentum worldwide, delaying abatement or pursuing mitigation policies in a way that is more costly than necessary could impair Australia’s long-term competitiveness. Extending coverage and rates of energy taxes would help Australia reduce emissions cost-effectively and prepare its economy for a low-carbon future.

Figure 3.3. Australia lags behind most OECD countries in pricing carbon

Other carbon pricing instruments

Emissions Reduction Fund and safeguard mechanism

Since 2014, the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) has been the main Commonwealth government instrument to mitigate climate change. Under this voluntary offset programme, businesses, local councils, farmers and landholders can register projects and earn Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) for every tonne of CO2 abated. Participants need to apply specific methods to demonstrate their projects create genuine emission reductions (CCA, 2017). The government committed AUD 2.55 billion to the ERF to buy ACCUs, primarily through reverse auctions.

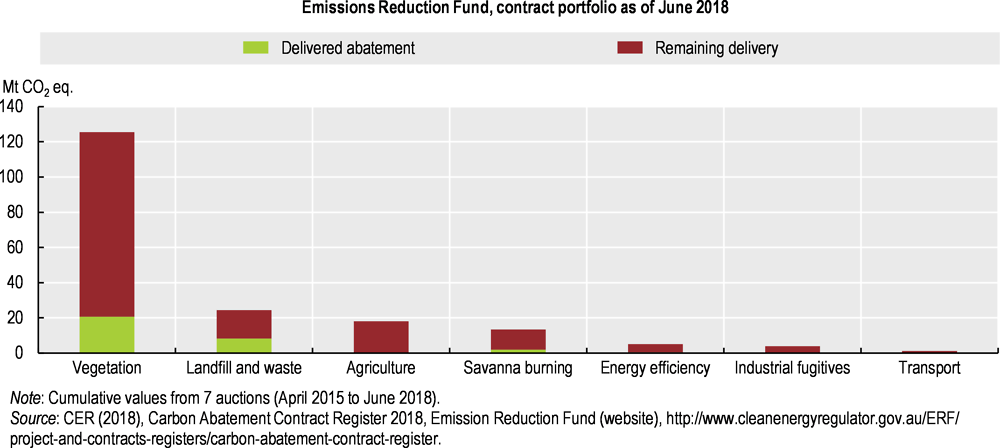

By June 2018, 460 projects had been contracted to abate 192 Mt CO2 eq. (more than a third of 2016 emissions) by 2030, of which 16% had been delivered (Figure 3.4). The ERF is open to all sectors, but the majority of contracted and delivered carbon abatement comes from vegetation management (carbon storage arising from regrowth of vegetation or from preventing land clearing) and landfill gas abatement and capture.2 The Climate Change Authority found that despite its complexity, the ERF has been found successful in incentivising new domestic abatement (CCA, 2017). However, it involves costs for the federal budget. While the ERF has strong governance and integrity measures, concerns were raised about emission reductions that might have happened without ERF support in the two biggest beneficiary sectors; about delivered abatement possibly being lower than expected; and about participants’ capacity for maintaining carbon storage in soil and vegetation over the long term. In addition, carbon abatement from the ERF is undermined by increased forest clearing in Queensland and New South Wales, where most projects are concentrated (Chapter 1). By June 2018, the ERF was nearly exhausted, with AUD 2.3 billion in projects contracted. While additional public funding is uncertain, other measures, such as the safeguard mechanism (described below), could incentivise the emergence of a private market.

Figure 3.4. The Emissions Reduction Fund mostly supports emission reductions from vegetation management

Since 2016, the ERF safeguard mechanism has ensured that emission reductions purchased by the government are not displaced by a significant rise in emissions elsewhere in the economy. It requires the largest emitters (above 100 000 tonnes of CO2 eq per year) in the mining, manufacturing, transport and electricity3 industries, accounting for nearly 60% of national emissions, to offset their emissions exceeding a baseline. For most facilities the baseline is linked to the highest historical emissions between 2009/10 and 2013/14. It can also vary with economic growth. As a result, the mechanism is not very constraining. In 2017, 16 facilities out of 2034 had to surrender ACCUs to offset emissions exceeding their baseline (CER, 2018). The safeguard mechanism is underpinned by a robust measurement, reporting and verification framework. With stricter baselines, it could provide an effective incentive to reduce emissions. However, the government should clarify its role in meeting climate targets.

National Energy Guarantee

In 2017, the government proposed a National Energy Guarantee (NEG), a market-based mechanism requiring electricity retailers to contract low emission and dispatchable power.5 It was recommended by the Energy Security Board6 in an attempt to restore investor confidence after a decade of instability in climate policies and after the government ruled out several policy options proposed by the Climate Change Authority and the independent Finkel review.7 However, no consensus was reached and the opportunity to provide a stable policy framework for the electricity sector, which is not subject to emission reduction constraints, was lost.

Transport taxes and charges

The transport sector is the highest energy consumer and second fastest-growing source of GHG (Chapter 1). Revenue from transport taxes (excluding road fuel taxes) rose to 40% of environmentally related tax revenue between 2005 and 2016, compared with 25% in the OECD. This trend has been driven by the growing vehicle fleet, which is less fuel efficient than in most G20 economies (IEA, 2017a). While vehicle taxes are less efficient than fuel taxes in reducing emissions of CO2 and local air pollutants, they can promote fleet renewal towards cleaner vehicles. As vehicles become more efficient, increased reliance on distance-based charges would better address road transport externalities and provide stable revenue (OECD, 2018d).

Taxes on vehicles

Registration fees and stamp duty levied by states and territories account for the bulk of transport tax revenue. Rates generally vary with vehicle size and price except in the Australian Capital Territory, where the rate is based on CO2 emissions. There, as in Queensland and Victoria, reduced rates apply for hybrid and electric vehicles (EVs). There is also a federal luxury car tax on the sale or import of cars whose value exceeds a set threshold. Its rate is 33% on the amount above the threshold, which is higher for fuel‑efficient vehicles irrespective of fuel type. In practice, the luxury car tax favours diesel vehicles, which are more efficient but emit more CO2 and harmful air pollutants per litre of fuel. Its complexity and inefficiency have also been criticised (Productivity Commission, 2014; Treasury, 2015).

Tax treatment of company cars and commuting expenses

The fiscal treatment of the use of a company car for personal purposes favours road use over other modes of transport. Australia's tax system captures a high share of the benefits of company car use compared with other OECD countries: employees bear nearly all the cost of private driving (Harding, 2014b). However, the forgone revenue related to this tax concession represented AUD 850 million in 2017-18 (Treasury, 2018a). Until 2011, the Fringe Benefits Tax unintentionally encouraged car use because its rate fell as kilometres travelled rose. The tax was reformed but the current system, which applies a single rate of 20% to vehicle cost price regardless of kilometres travelled, continues to create an incentive for employees to drive more. In addition, no such concession applies on commuting expenses for public transport or bicycles, although exemption applies in limited circumstances for travel by bus. There is thus room to review the tax incentives to promote alternative modes of transport (Pearce and Hodgson, 2015).

Road pricing

There is considerable scope for better pricing of road use with distance-based taxes and congestion charges (OECD, 2014). Congestion in capital cities has been growing with rising population. Related costs, which represented 1% of GDP in 2011, are expected to reach 2% by 2031 (Infrastructure Australia, 2016). Road pricing can help reduce pollution and finance transport infrastructure (Section 3.5.4). Sixteen toll roads operate in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane and on long-distance routes connecting major traffic nodes (BITRE, 2016). Fixed rate is the main form of charging, but three tolls have varying rates – according to distance (Western Sydney) and time of the day or day of the week (Sydney Harbour Bridge and Tunnel). Some states charge parking levies: Victoria, for example, imposes an annual “congestion levy” on parking spaces in inner Melbourne. No congestion fees such as those in Stockholm or London are in place. Pilot programmes on road charging in states and territories could help increase political support nationwide (Productivity Commission, 2017a). A heavy vehicle reform currently under way is conducting pilot programmes to design charging options.

Other economic instruments to limit resource use

Waste disposal levy and waste charges

Adopting a consistent national framework for landfill levies would help improve waste management policy effectiveness. Most states impose such levies, which have helped increase recycling. In real terms, related revenue quadrupled over 2005-16. However, uneven implementation across jurisdictions hampers waste recovery efforts. In 2017/18, the landfill levy was AUD 138 per tonne in New South Wales (metropolitan area), AUD 87 in South Australia, AUD 63 in Victoria and AUD 65 (putrescible waste)/AUD 60 (inert waste) in Western Australia (metropolitan area) (Western Australian Department of Treasury, 2018). The Northern Territory and Queensland have no landfill levy (it was removed in Queensland in 2012). The differences have resulted in significant amounts of waste being sent to landfill in Queensland. In a welcome move, Queensland has announced it will introduce a landfill levy of AUD 70 per tonne in 2019 (Queensland Government, 2018).

A small part of revenue from landfill levies is earmarked for waste recovery infrastructure and management programmes: 15% in New South Wales and Victoria, 25% in Western Australia and 50% in South Australia (Ritchie, 2017; Western Australian Department of Treasury, 2018). Recently China and other countries have restricted waste imports, reducing the value of recyclables and increasing stockpiling (Pickin, 2018).8 Industry and local governments are calling for states to help by earmarking more revenue. This may be necessary to secure sufficient funding in the current situation, but in the long run earmarking can reduce the flexibility and efficiency of revenue allocation.

Combining the landfill levy with variable pricing for municipal waste services would increase the levy’s effectiveness, encourage waste minimisation and recovery, and fund advanced management. There is a weak link between the quantity of municipal waste disposed of and the cost of disposal (Productivity Commission, 2006). The landfill levy is passed on to local governments, which provide waste disposal services to households and recover their costs through local charges. The charges are typically imposed at a flat rate, although some local governments charge more for provision of a larger than standard bin.

There has been a national product stewardship (extended producer responsibility) programme on televisions and computers since 2012, which provides tangible outcomes but is limited in scope. It should be extended to cover additional products as pledged by environment ministers (Chapter 1; OECD, 2016a). The recent restrictions on waste imports by China and others is an opportunity to further develop the domestic waste market, create jobs in the sector and steer the transition to a circular economy. Updating the Waste Account, which links waste management and economic policies, would be useful to inform this development.

Water trading

Since the 1980s, Australia has been a front runner in developing water markets, and it has further progressed under the National Water Initiative (NWI) (Chapter 1). Markets are established as cap-and-trade systems where the cap represents water available for consumptive use that enable scarce water resources to be allocated to their most productive use. Water markets were first developed in irrigation systems in the Murray‑Darling Basin (MDB) and were then gradually expanded to other catchments, sometimes interconnected.

Tradable rights can be permanent as share of water from a consumptive pool (entitlement) or for a given season according to availability and volume held in storage (allocations) (OECD, 2013a; Aither, 2018). To maintain water consumption at a suitable level for a drier climate it is increasingly important to ensure that the impact of climate change on water resources is regularly assessed and systematically integrated into water resource analysis for allocation setting (Productivity Commission, 2017b).

Water allocation trading has grown significantly, from about 1 500 GL in 2007/08 to 5 816 GL in 2015/16. Most of it takes place in the MDB, which accounts for more than half of agricultural water use. Surface water remains the main source of trade, but groundwater trade is increasing in the MDB and elsewhere. Actors can make informed decisions on whether to buy or sell their water rights based on the price of water, which varies by region, type of rights and time of year. Entitlement prices reflect expected annual allocation volumes and prices. Allocation prices peaked near the end of the Millennium Drought in around 2008 (ABARES, 2017).

There is widespread agreement that the markets provide positive social outcomes. With increased flexibility reflecting changes in water availability, markets supported irrigators’ adaptation responses to climate risks. There is only a small number of studies quantifying the benefits of trading, but they show significant economic benefits, especially in time of drought (Productivity Commission, 2017b). Removing barriers to trade between the irrigation and urban sectors could provide still greater benefits, as households are willing to pay more than irrigators. In some areas, information deficiencies on water resources and prices undermine the efficiency of water markets.

Water markets have helped deliver environmental outcomes through the purchase of water for the environment by environmental water holders (e.g. the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder). About 20% of MDB water entitlements is managed for the environment. The NWI requires monitoring of water managed for environmental and other public benefits. The federal and state governments need to improve monitoring and reporting to meet this requirement, help build public trust in water management and make better use of environmental water. Water buy-backs are the most cost-effective way of reducing over-extraction. A recent decision to prioritise infrastructure projects over water purchases in the MDB poses a challenge to the NWI commitment to select water recovery options based on cost-effectiveness (Productivity Commission, 2017b).

Removing subsidies potentially harmful to the environment

Support to fossil fuel production and consumption

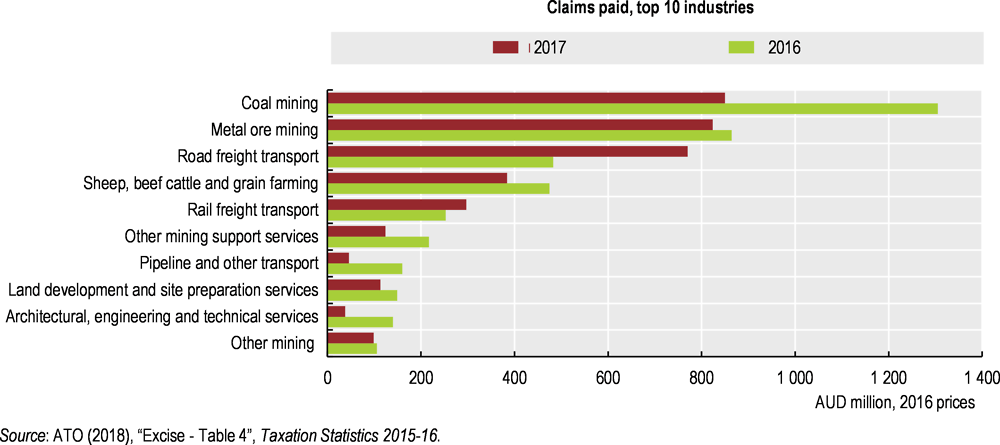

Support to fossil fuel consumption represented 43% of energy-related tax revenue in 2016, a high share by OECD comparisons (OECD, 2017c). The main measure is a Fuel Tax Credits programme that accounts for 81% of total consumer support. It refunds off‑road users the full amount of excise tax, and on-road heavy transport gets a partial rebate (OECD, 2018e). Most beneficiaries are businesses using diesel fuel in machinery, equipment or heavy vehicles. Mining is the main beneficiary (44% of payments), followed by transport (19%) and agriculture (13%) (Figure 3.5). In real terms, Fuel Tax Credits have increased by 34% since 2005.

Other consumer support measures include a reduced excise rate on aviation fuel, liquefied petroleum gas and natural gas for road use. Domestically produced biodiesel is untaxed. In addition, most states and territories provide rebates to low-income households to compensate for heating or cooling costs, in addition to bill assistance (OECD, 2013b, 2015a, 2018e). Providing direct support to vulnerable households, decoupled from energy use, and setting tax rates at levels that better reflect the environmental costs of energy use would be more efficient in addressing environmental and equity concerns. Simulations show that increasing taxes on heating fuels and electricity can reduce energy affordability risk if part of the additional revenue is returned to households using an income-tested cash transfer (Flues and Van Dender, 2017).

Figure 3.5. Mining is the main beneficiary of Fuel Tax Credits

There are no longer any significant support measures in the upstream sector since 2011, when the exemption from crude oil excise for condensate was phased out. But New South Wales, the Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia have programmes encouraging hydrocarbon exploration. Transitional assistance to coal mining, such as the Coal Sector Jobs Package and the Coal Mining Abatement Technology Support package, was provided to compensate for the carbon tax, although payment for technology support will continue until 2019/20 (Australian Government, 2018b).

There is no comprehensive information on potentially environmentally harmful subsidies and tax expenditure. The Trade and Assistance Review, the Productivity Commission’s statutory annual report on industry assistance and its effects on the economy, could be a vehicle for screening public support programmes with a view to identifying and eliminating those with adverse environmental effects.

Taxes on resource extraction

Taxes on energy and mineral resource extraction9 are collected by the federal or state/territory government, depending on project location. They are an important source of revenue. The main resource taxes levied on oil and gas projects are the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT), based on super-profits, and the crude oil excise and petroleum royalties, levied as a share of production value (DIIS, 2018).

Low international oil prices, declining oil production in mature projects and increasing deductible expenditure from large new investments in liquefied natural gas (LNG) production have accelerated a decline in PRRT revenue from 0.2% of GDP in the early 2000s to 0.1% in recent years. This has raised concern about equitable return to the Australian community and triggered a review of the PRRT in 2017 (Callaghan, 2017). The overall conclusion was that while the PRRT remained the preferred way to achieve a fair return to the community without discouraging investment, changes should be made to take account of the increased dominance of LNG projects, which have longer lives but smaller profits than oil projects. The review recommended updating the PRRT for new projects and improving its integrity, efficiency and administration for existing and new projects. While there is a consensus among non-industry players that the PRRT is too generous, the tax has not been revised (The Senate, 2018a).

Between 2012 and 2014, the Mineral Resource Rent Tax was levied on certain profits from iron ore and coal extraction to spread the benefits of the mining boom. It was repealed in 2014 in fulfilment of an electoral promise, despite an OECD recommendation to broaden its scope (OECD, 2012, 2014, 2015b). Both onshore and offshore mineral extraction is subject to royalties, which are either collected by the states and territories at various rates or by the Commonwealth (DIIS, 2018). Victoria tripled its brown coal royalty rate in 2017, aligning it with other jurisdictions (Victoria State Revenue Office, 2016).

Support to agriculture

Australia reduced its support to agriculture from already low levels, compared to other OECD countries, to 0.13% of GDP in 2017 (OECD, 2018f). There is no longer any potentially distorting market price support and domestic production prices are aligned with international levels. Support is split between direct support to producers10 (44% in 2017) and general services support (56%). Producer support is mainly provided through subsidies for upgrading on-farm water infrastructure and payments that seek to help producers deal better with droughts and other natural events through concessional loans. General services support is for agricultural innovation and infrastructure development. Since 2007, its share in total support nearly doubled as governments increased funding for irrigation infrastructure, especially in the MDB. Inadequate cost-benefit analysis has resulted in funding of several projects with poor financial and environmental performance, often for the private benefit of irrigators (Productivity Commission, 2017b). Similarly, as past programmes have been questioned, support to risk management measures should be reviewed to ensure that they effectively support drought preparedness and resilience (OECD, 2018f).

Investing in the environment to promote green growth

Environmental protection expenditure

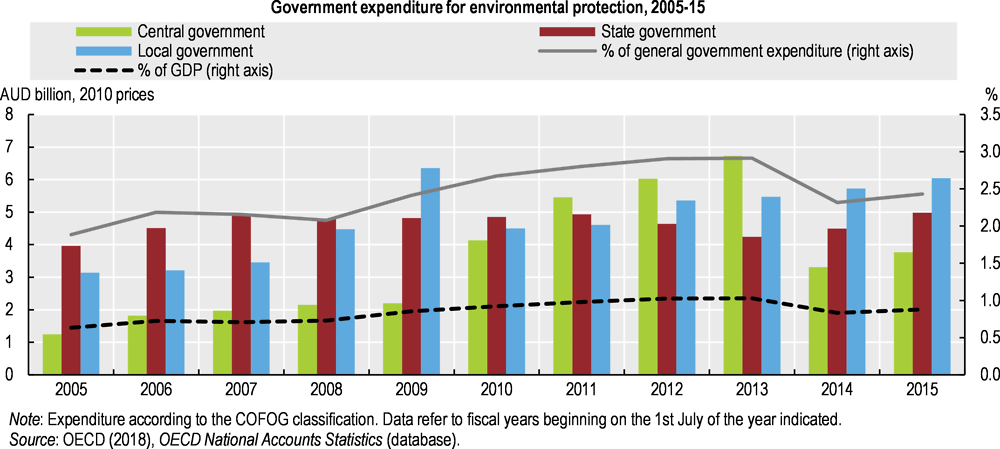

Government expenditure on environmental protection rose from 0.6% of GDP in 2005 to 1.0% in 2013 before decreasing to 0.9% in 2015 due to a sharp decline in Commonwealth spending not counterbalanced by increases in local and state expenditure (Figure 3.6). The most affected areas are difficult to identify as no breakdown of expenditure data by environmental domain is available. Australia does not produce regular environmental expenditure accounts (ABS, 2014). Federal expenditure on biodiversity has been relatively stable at around 0.03% of GDP in recent years, but plans call for it to shrink in the future (Chapter 4).

Figure 3.6. Federal expenditure on environmental protection has been declining since 2013

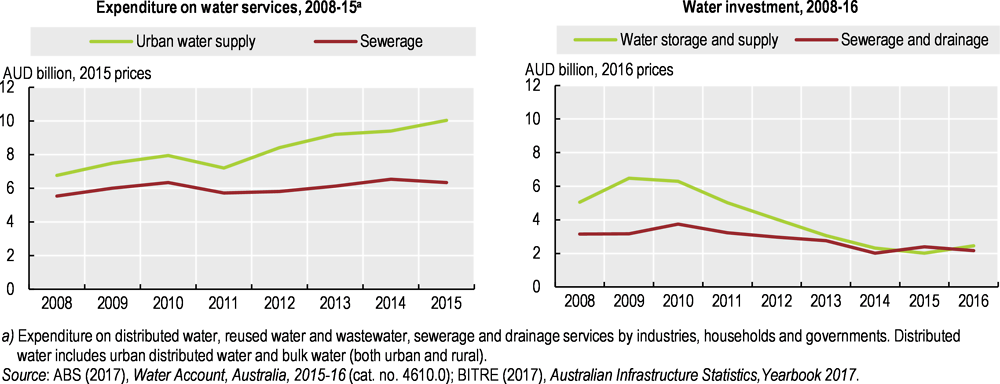

Expenditure on urban water supply and sewerage

Over 2008-15, expenditure on urban water supply increased by 50% as operating expenditure rose (Figure 3.7). The average annual household water bill could double over 2017-40 (Infrastructure Australia, 2017). While urban water services are mainly provided by government-owned entities, a high and increasing share of expenditure is outsourced to the private sector (Productivity Commission, 2017b). The introduction of independent economic regulation in major urban areas (metropolitan providers in the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria) has promoted more efficient pricing. However, providers in regional New South Wales,11 the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia are not subject to formal price regulation.

The NWI requires prices to reflect the long-run cost of service delivery, including both capital and operating costs. While large metropolitan and jurisdiction-wide providers generally achieve full cost recovery, there is some evidence of underpricing in regional New South Wales, Queensland and Tasmania. The NWI recognises that in remote areas, communities require assistance to deliver affordable service, provided through Community Service Obligation (CSO) payments. However, the New South Wales, Queensland and Commonwealth governments provide assistance through capital grants, generally poorly targeted. They should be replaced by CSO payments that are better directed at high-cost service areas and not tied to capital expenditure. Amalgamating small service providers would also improve regional service provision.

Figure 3.7. Expenditure on urban water supply has increased significantly

Investment has decreased since its 2008-12 peak, when significant investment was made in desalination plants to relieve drought (Figure 3.7; Productivity Commission, 2017b). Such investment was not always necessary and alternative options could have reduced the cost of urban water services significantly. While the need for major supply augmentation has declined, it is likely that climate change and population growth will necessitate further investment. Improved planning and decision making are needed to ensure that future investment is cost-effective. Despite the separation of policy, service provision and regulatory functions through corporatisation of urban water utilities, the role and responsibilities of jurisdictions could be clarified.

In recent years, there has been a move towards use of more decentralised approaches to water service provision, including on-site wastewater treatment and reuse and storm water harvesting. However, no jurisdiction has fully succeeded in implementing such an integrated approach. Further progress would require developing integrated water cycle management plans for major growth corridors and ensuring that options identified are considered in water and land use plans. Better reflecting the cost of serving a particular area in developer charges could also provide incentives to invest in onsite options (Productivity Commission, 2017b).

Investment in energy efficiency and renewable energy sources

The investment outlook in the National Electricity Market is challenging (IEA, 2018). Gas generation is being squeezed out by exceptionally high gas prices, the Renewable Energy Target will not increase beyond 2020 and it is expected that more coal power plants will be retired by 2030. There has been no investment in thermal capacity in recent years due to lower than forecast electricity demand, falling energy technology costs and uncertainty on future climate policies. Implementing stable climate policies aligned with the Paris Agreement, including a long-term emission reduction goal, is critical to restore investor confidence. To ensure that new investments are consistent with climate objectives, greater visibility is needed with regard to the role and contribution of energy efficiency and renewables to emission reduction (Chapter 1).

Energy efficiency

The Commonwealth government finances energy efficiency and renewables investment mainly through the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (Box 3.3), the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (Box 3.5) and the ERF (Section 3.3.3). The 2015 National Energy Productivity Plan (NEPP) aims for a 40% improvement by 2030. It is expected to contribute more than a quarter to Australia’s 2030 climate target. However, it does not specify savings expected from listed measures, their contribution to emission reduction or estimated investment needs. Energy productivity improvement is not fast enough to reach the 2030 NEPP target, highlighting the need for additional efforts (Chapter 1). Measures with great potential – such as energy prices reflecting social and environmental costs, efficient vehicles and updated energy efficiency requirements in the National Construction Code (to be updated in 2019) – remain to be taken.

Australia has no long-term vision or target for energy-efficient buildings (IEA, 2018). Such measures would be justified, since buildings represent half of electricity use. The National Construction Code is out of date regarding energy efficiency requirements and should be revised to align new buildings’ performance to a low-carbon economy. The nationwide mandatory programme for disclosure of the energy performance of commercial buildings is expected to lead to AUD 69 million in energy savings over 2015‑19. It could be extended to residential buildings. In 2016/17, the CEFC committed AUD 611 million for energy efficiency improvements in buildings.

Despite the large potential for improving energy efficiency in industry, related measures in the NEPP are vague (e.g. helping business self-manage energy costs, recognising business leadership and supporting voluntary action). Many grant programmes ended in 2015 and the CEFC provides only minor support (IEA, 2018; CEFC, 2017). While few industrial projects have been contracted under the ERF, the safeguard mechanism could incentivise energy efficiency in large industrial facilities.

States and territories have their own policies and targets, with varying levels of ambition. White certificate programmes are operational in the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria (IEA, 2018). Large subsidy programmes help households with their energy bills. However, such subsidies are often not well targeted and fail to encourage energy savings. They should be reformed to support consumer action on energy efficiency (e.g. renovation, fuel switching, flexible tariffs, metering).

Box 3.3. A green bank to scale up clean energy investment

Australia is one of the few OECD countries to have established a green bank at the national level. The Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC), an independent statutory authority, was set up in 2012 to facilitate increased flows of finance into the clean energy sector. It finances projects related to energy efficiency and technology related to reduced emissions and renewables, but excludes carbon capture and storage (CCS) (as of May 2018) and nuclear power. Financing takes a variety of forms, from project finance and co-financing programmes to corporate loans, climate bonds and equities.

The government credited the CEFC with AUD 2 billion a year from 2013 to 2017, totalling AUD 10 billion, to support debt and equity investments in clean energy projects. As of June 2018, the CEFC had committed AUD 5.3 billion to projects with a total value of AUD 19 billion (1% of 2018 GDP).

In 2017/18, 53% of the commitments went to renewable energy projects, 44% to energy efficiency and 3% to low emission technology. The CEFC’s performance is assessed against criteria defined by its board and the government. In 2017/18, financial leverage was AUD 1.8 for every AUD 1 committed by the CEFC, above the target of 1:1. CEFC’s portfolio of investment commitments is expected to abate 10.8 Mt CO2 eq. annually.

The introduction in Parliament in 2017 of a bill to include CCS in the CEFC mandate is an important step for CCS investment but should come as part of a balanced portfolio of technology.

Source: CEFC (2018), FY18 Investment update; CEFC (2017), CEFC Annual Report 2016-17; OECD (2016), Green Investment Banks.

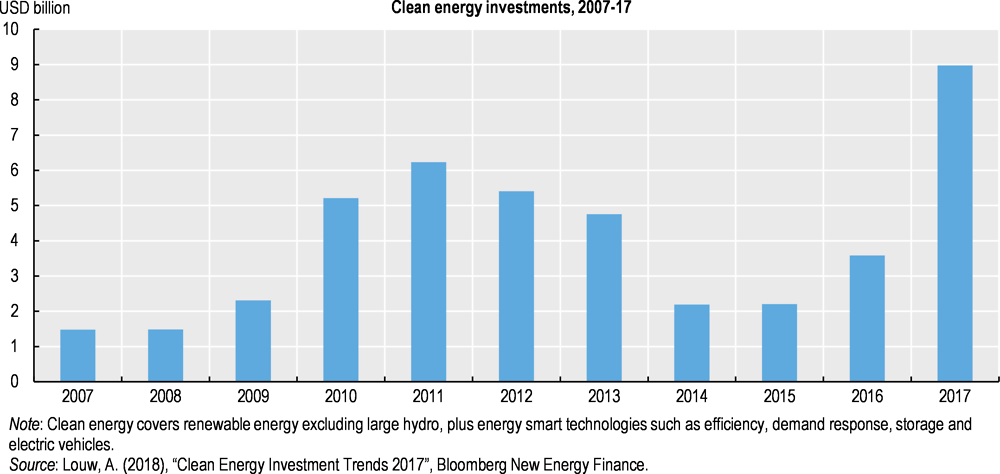

Supporting renewable energy sources

The share of renewables in electricity generation grew from 9% in 2005 to 16% in 2017 (compared with the OECD average of 25%), mainly through increased solar and wind power. In 2017, Australia hit a national record of USD 9 billion in renewables capacity investment, the seventh highest level globally, expected to secure the country’s achievement of its 2020 renewables target (Figure 3.8). The growth has been uneven, however, with a high rate of deployment in the residential sector and in South Australia (Box 3.4). This raises integration concerns in the long and weakly interconnected National Electricity Market and will require accompanying investment in network upgrades, flexible generation and storage, and demand response (IEA, 2017b).

Figure 3.8. Record 2017 investment secured the 2020 target on renewables

Box 3.4. Australia is becoming a global leader in solar photovoltaics

Reflecting the global trend, 2017 was a record year for solar photovoltaics (PV) in Australia, with 1.2 GW of capacity added for total capacity of 7.2 GW (expected to reach 8.5 GW in 2018). The country is now ranked among the top ten national markets for newly installed capacity and among the leaders in terms of PV capacity per inhabitant.

Two-thirds of new installations took place in the residential sector as a response to rising electricity prices and decreasing solar PV costs. More than 30% of dwellings in South Australia and Queensland had a solar rooftop PV system in 2018. Increasingly, PV installations are combined with energy storage systems as they become cheaper. The market for batteries is expected to grow substantially, providing an energy security solution and ensuring that supply matches demand. Commercial rooftop systems also increased rapidly: nearly 2 million were operating in 2018.

Source: APVI (2018), Solar Map 2018, http://pv-map.apvi.org.au/analyses; IEA (2018), Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Australia 2018 Review.

At the national level, the Renewable Energy Target, a quota system mandating production of 33 TWh based on renewables by 2020, has been a major driver of investment. In addition, feed-in tariffs are in place in the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and Victoria for small-scale solar, while the Australian Capital Territory, Queensland and Victoria run auctions to support large utilities.

Box 3.5. The Australian Renewable Energy Agency supports renewables development

The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) is a Commonwealth government agency that was established in 2011 to improve the competitiveness of renewables technology and increase the supply of energy based on renewables. It provides grants and invests in research, development, demonstration, deployment and early-stage commercialisation of renewables technology and, more recently, energy efficiency projects.

ARENA’s budget was initially set at AUD 2.2 billion for 2013-22 but was reduced to AUD 1.9 billion in 2016. The agency was close to being abolished in 2014, but the Senate opposed the repeal bill.

Since 2012, ARENA has supported 320 projects with AUD 1 billion in grant funding unlocking AUD 2.5 billion in private funds. In 2016/17, investment projects focused on large-scale solar PV (AUD 92 million in grants to construct 0.5 GW of solar farms in New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia) and integrate renewables into the grid (AUD 16 million in grants, mostly in New South Wales). Renewables deployment had the priority (AUD 108 million), followed by demonstration (AUD 11 million) and research and development (R&D) (AUD 4 million).

Source: ARENA (2017), Annual report 2016-2017; ARENA (2017), Australian Renewable Energy Agency website, https://arena.gov.au/.

Investment in sustainable transport

Growing population and economic activity are putting pressure on transport systems. Road and rail freight transport are expected to almost double over 2011-31, as are congestion costs in capitals, where public transport demand exceeds capacity (Infrastructure Australia, 2015). The 2016 Australian Infrastructure Plan, which provided a roadmap to address infrastructure gaps and meet future challenges, recommended an increase in funding (Infrastructure Australia, 2016). Transport investment did rise in 2016, and the government has committed AUD 75 billion to develop transport infrastructure over 2018/19-2027/28 (Treasury, 2018b).

Between 2005 and 2016, more than three-quarters of transport investment was devoted to roads. In 2016, road investment accounted for 1.1% of GDP, a higher share than in any other OECD country (ITF, 2018). Redirecting funding to public transport would make cities more sustainable. Australian cities have less travel by foot, bike and public transport than other big cities in the world (Arcardis, 2017). Some signs of progress can be seen, however. The Sydney Metro, funded 50-50 by the Commonwealth and New South Wales, is the country’s biggest public transport project. Sydney Metro Northwest (2019) and Sydney Metro City and Southwest (2024) will increase Sydney’s rail capacity in morning peak time by up to 60% (NSW government, 2017).

Additional transport infrastructure investment will not necessarily improve service quality. Although progress has been made in project selection, economic assessment has been overridden in some cases, the decisions being driven by political rather than economic and social merit. Much public investment is not subject to ex post evaluation (Infrastructure Australia, 2018; Productivity Commission, 2017a). More efficient use of existing transport infrastructure and better integration of transport services are also needed. Misaligned investment choices between road and public transport in the past have reduced growth in public transport capacity relative to demand. State and local governments have been active in developing metropolitan plans (e.g. the 2018 Greater Sydney Region Plan, Plan Melbourne 2017–2050, 2018 Perth and the Peel@3.5million) (Infrastructure Australia, 2018). However, there is room to better integrate transport and land use planning.

With the decline of revenue from fuel excise taxes, maintaining and developing the road network will impose an increasing burden on governments’ budgets. Wider use of road pricing would better address road transport externalities and secure long-term funding for infrastructure (Section 3.3.4). It would also enhance transport planning: user charges create demand signals that help make expenditure more responsive to user preferences (Productivity Commission, 2017a).

The last domestic carmaker closed in 2017. Many of the foreign companies making new cars now bought in Australia have committed to transition their fleet to EVs. The country’s uptake of EVs is low, although some jurisdictions are moving forward (Box 3.6). The reasons include limited options (16 EV models are available) and lack of infrastructure (476 public charging stations, compared with more than 60 000 in Europe). In 2015, electric cars represented 0.1% of new sales, compared with 1.2% in the EU (The Australia Institute, 2017). Financial support is provided through ARENA and the CEFC (Section 3.5.3). For example, the latter promotes EVs through the Sustainable Cities Investment Program.

Box 3.6. The Australian Capital Territory plan to promote low-emission vehicles

The Australian Capital Territory government has announced the ambitious targets of reaching 100% renewables-based electricity by 2020 and zero net GHG emissions by 2045. In April 2018, it released a plan to promote EVs, including:

Regulatory measures: require all newly leased territorial government passenger vehicles to be zero emission by 2021 (and at least 50% by 2019/20); require all new multi-unit and mixed-use developments to install charging infrastructure, and allow hybrids and EVs to drive in transit lanes, by 2023.

Fiscal instruments: exempt from stamp duty all purchases of new EVs since 2014 and provide a 20% discount on annual registration fees for EVs.

Source: ACT (2018), ACT's Transition to Zero Emissions Vehicles; ACT (2018), ACT's Climate Strategy to a Net Zero Emissions Territory.

Greening investment practices in the corporate and financial sectors

Greening investment practices

In 2017, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority stressed that risks associated with climate change could become financial risks and called on institutions to consider how climate risks might affect them (Summerhayes, 2017). Policy makers need to assess whether assets can become stranded by anticipating costly "lock-in" and ensure that government revenue, particularly at the state level, is resilient against potential discontinuity with a diversified tax base. Coal assets can be at particular risk of becoming stranded, especially considering China's evolving landscape in terms of regulations, carbon pricing and public pressure due to air pollution (Caldecott et al., 2013).

Green bonds

The first AUD-denominated green bond went on the market in 2014. Since then, the domestic market has grown rapidly. Australia ranks among the top ten countries for level of labelled green bond issuance, even if it represents a small share of the USD 221 billion in labelled green bonds worldwide. As of 2017, a dozen institutions had issued 15 labelled green bonds with a cumulative total of AUD 5.5 billion. The issuers included the country's four main banks (National Australian Bank in 2014, Australia and New Zealand Banking in 2015, Westpac in 2016, Commonwealth Bank of Australia in 2017), two state governments (Victoria and Queensland) and a property company (Investa Office Fund). Thus far the offerings have been fully subscribed, if not oversubscribed, reflecting strong demand among investors. The main barriers to issuance relate to the cost of learning to work with a chosen verification framework and of verification. The green bonds are mostly financing renewables projects. Support from the CEFC helped drive the green bond market development, which will remain essential to unlock new sources of capital (Climate Bonds Initiative, 2017).

Promoting eco-innovation

General innovation performance

At the national level, the Cabinet Investment, Infrastructure and Innovation Committee oversees public investment in R&D, supported by advice from the Commonwealth Science Council and Innovation and Science Australia. The government stimulates innovation by investing in higher education, businesses and research (e.g. by CSIRO). There has been a shift from public demonstration funding to tax incentives in the latest reform of innovation funding. One key measure to boost R&D was the R&D Tax Incentive Programme for businesses, which was reformed in 2018 to improve its effectiveness and fiscal affordability (Treasury, 2018b).

Australia performs well in terms of knowledge creation. Growing expenditure on R&D in higher education has resulted in strong skills foundations, availability of high-quality education at world-class universities, and high-impact publications (Innovation Science Australia, 2016). However, a well-performing innovation system, with good knowledge transfer and application, also requires good collaboration between industry and research and considerable international engagement – areas in which Australia ranks poorly, especially outside the resource sector. It also falls lower than the OECD median on international co-patenting (Department of Industry, 2016; OECD, 2016b).

Gross domestic expenditure on R&D peaked in 2008 (at 2.3% of GDP) and has slightly declined since to below the OECD average (1.9% vs. 2.3% of GDP in 2015). This decline reflects a slowdown in mining-related R&D. The main performers of business R&D are large firms in the primary and resource-based industries. The contribution of high-technology manufacturing to business expenditure on R&D is lower than in most OECD countries (OECD, 2016b). Public budget allocation to R&D follows a similar trend.

Policy framework for eco-innovation

National level

Climate change and associated risk and inadequate investment in innovation were identified as the greatest threats to Australia's future prosperity (Department of Industry, 2013). There is no national eco-innovation framework or co-ordination eco‑innovation mechanism. The recent 2030 roadmap for innovation and the 2015 National Innovation and Science Agenda do not adequately feature environmental issues (Innovation Science Australia, 2017). However, many initiatives focus on clean energy and environment, from research to commercial deployment.

The 2015 Energy White Paper calls for accelerating investment in technology that will support economic development, productivity and affordability and prioritises innovation in areas supporting Australia's export advantage. Technology areas that could address Australia’s challenges and help other countries decarbonise include addressing growing fugitive emissions (e.g. ventilation air methane, CCS) and accelerating renewables (e.g. geothermal and wave energy), identified in CSIRO’s Low Emissions Technology Roadmap (Campey et al., 2017). Implementing this roadmap and driving eco-innovation in general will require a clear long-term policy framework with secured government support to R&D.

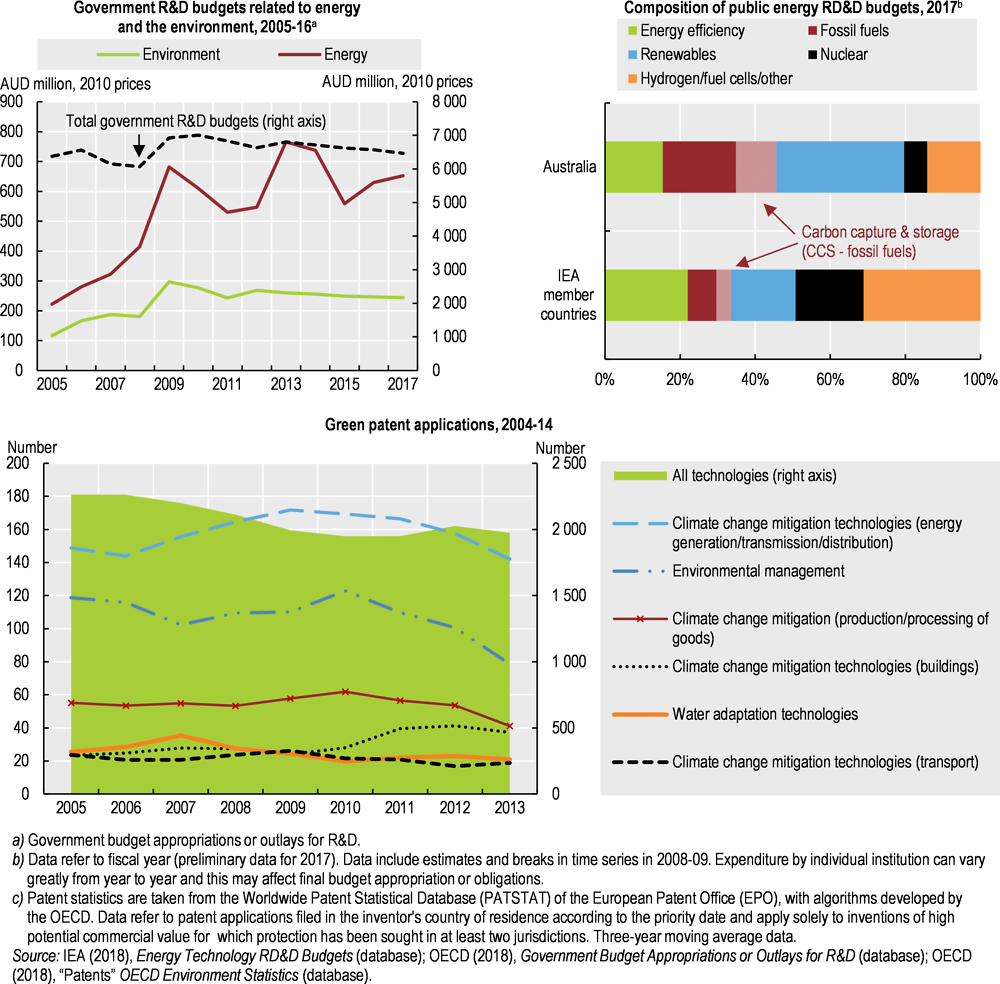

Along with 22 other countries in the Mission Innovation initiative, Australia pledged to double public investment in clean energy R&D between 2015 and 2020 (equivalent to AUD 216 million per year). However, this represents a small increase from historical levels of the public low-carbon energy RD&D budget. ARENA and the CEFC (Section 3.5.3) are key actors in helping clean energy technology become commercially viable. For example, the CEFC is to invest AUD 1 billion over ten years in the Sustainable Cities Investment Program. Together, they administer the AUD 200 million Clean Energy Innovation Fund.

The government has been funding R&D programmes to accelerate deployment of low‑emissions technology for fossil fuels, but policy changes over the last decade are likely to have affected these programmes’ operation (Box 3.7). They include the Low Emission Technology Demonstration Fund, the Coal Mining Abatement Technology Support Package, the Carbon Capture and Storage Flagships programme and the National Low Emissions Coal Initiative. The latter two saw their funding cut by at least half for a combination of strategic, technical and financial reasons (ANAO, 2017).

The government also funds research to tackle environmental challenges through the National Environmental Science Program. This includes six research hubs, receiving between AUD 8 million and AUD 31 million each, for a total of AUD 145 million between 2015 and 2021. The hubs focus on clean air and urban landscape, earth systems and climate change, northern Australian environmental resources and tropical water quality. All are required to produce meaningful results for stakeholders (Chapter 4).

State and territory level

States also have innovation strategies. In addition to its general strategy, Victoria set up an energy sector-specific strategy in 2016 and opened a Centre for New Energy Technologies to support collaboration between industry, universities and government. It also supports Climate Change Innovation Grants. Western Australia’s Low Emissions Energy Development Fund provided competitive grants in 2008-12 funding 12 projects totalling AUD 26 million.

New South Wales has a range of R&D programmes to support higher efficiency in the coal sector. Since 2009, Coal Innovation NSW has supported R&D and demonstration of low-emission coal technology for future commercial application. With a AUD 100 million fund, it supports research in fugitive emissions from coal extraction, coal combustion efficiency, CO2 capture and alternative CO2 storage methods. It also has a stated goal of increasing public awareness of these technologies.

Box 3.7. Australia was an early developer of carbon capture and storage

Carbon capture and storage has a role to play in keeping a global temperature rise below 2°C above pre-industrial levels. In Western Australia, Chevron’s Gorgon Carbon Dioxide Injection Project will be the world's largest CCS injection project once it starts operating in 2019, storing 3.4 to 4 Mt CO2 annually and reducing GHG emissions from the LNG project by about 40%. This CCS project is estimated to cost AUD 2.5 billion, with AUD 60 million provided by the Australian Government's Low Emissions Technology Demonstration Fund. Other projects are ongoing, such as the CarbonNet CCS Flagship and CO2CRC Otway Storage Demonstration projects in Victoria and the Callide Oxyfuel project in Queensland; still others were abandoned (e.g. ZeroGen project in Queensland).

Although federal and state governments have funded various programmes for CCS over the years, the level of funding has gradually been scaled down, along with the number of patents filed for CCS technology. The federally funded National Low Emissions Coal Initiative (NLECI), CCS Flagships Programme, Low Emissions Technology Demonstration Fund and Coal Mining Abatement Technology Support Package are closed to new applicants. The Australian National Audit Office noted that the NLECI and CCS Flagships projects were yet to reach the stage of deployable technology as was originally envisaged, despite nearly half a billion AUD spent. The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science is undertaking an evaluation of all low-emission fossil fuel technology programmes to inform future CCS policy.

Australia needs to continue to gauge the role CCS can play in various industries at home and abroad, such as natural gas and LNG, iron and steel production (e.g. United Arab Emirates), cement production (e.g. Norway), fertilisers (e.g. South West Hub facility in Western Australia), chemicals and textiles.

It also needs to continue assessing storage capability and risk of leakage at its sites, as well as ensuring regular measurement, monitoring and verification and community engagement. The completion of demonstrated, end-to-end CCS projects in Australia, supported by a stable and coherent policy framework and continued funding, would help the development and deployment of CCS in the country and worldwide.

Source: ANAO (2017), Low Emission Technologies for Fossil Fuels; Campey et al. (2017), Low Emissions Technology Roadmap; Global CCS Institute (2017), “Climate Change Policies Review”; IEA (2018), Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Australia 2018 Review; IEA (2017), Energy Technology Perspectives 2017: Catalysing Energy Technology Transformations; IPCC (2014), Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change, Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; OECD (2018), “Patents”, OECD Environment Statistics (database).

Performance on eco-innovation

Government support to energy R&D followed an upward trend until 2013, then was cut by two-thirds. The environment-related R&D budget has also decreased in recent years (Figure 3.9). The energy-related public RD&D budget dropped in 2014 as funding for CCS fell (Box 3.7), along with that for renewables. Spending on renewables peaked when ARENA began making grants in 2013. In 2017, public energy RD&D was split between fossil fuels (including CCS) and renewables, which accounted for about a third each, higher shares than in IEA countries. The public RD&D budget on energy efficiency has declined since 2010 and now accounts for 15% of energy RD&D – a smaller share than in IEA countries. Energy storage technology accounted for 3% of public energy RD&D in 2017.

Figure 3.9. Public R&D spending targets the energy sector

Australia is a small contributor to patents on environment-related technology in terms of share of environment-related inventions worldwide, and has a low level of inventions per capita. But its share of total environment-related patents is similar to the OECD average. Most of the patents apply to climate mitigation technology and only a few involve water‑related adaptation technology (Figure 3.9). Australia ranks poorly in terms of share of patents resulting from international collaborationFigure 3.9.

Labour and socio-economic implications of the green growth transition

Employment in the environmental goods and services sector

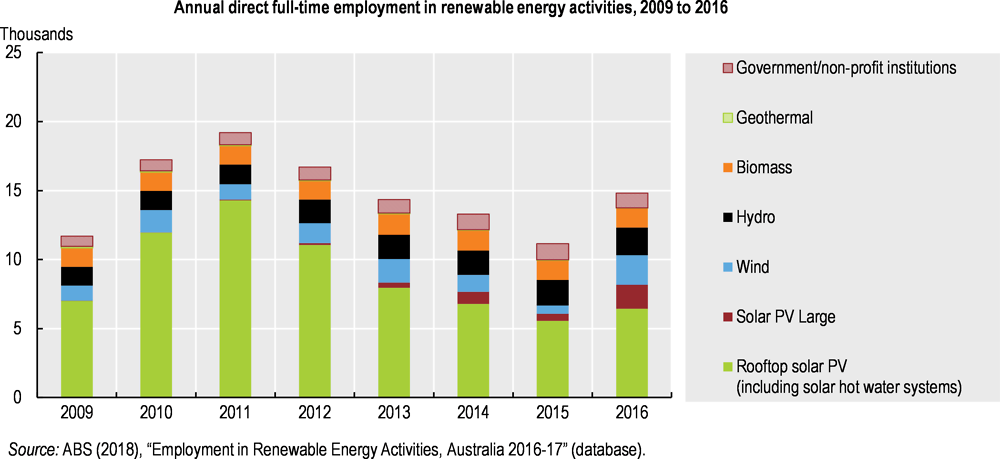

Environmental policies reshape labour markets in ways that can create opportunities but also risks, with different effects across sectors or regions. Quantitative evidence of labour market implications of green growth policies is important to move the agenda forward by maximising benefits and anticipating risks (OECD, 2017d). Australia does not monitor economic activity and employment in the environmental goods and services sector. It does, however, estimate employment in key areas such as waste management and renewables.

The waste sector is an important employer across the OECD. In Australia, the recycling industry alone directly employs over 20 000 people and indirectly almost 35 000 (about 0.3% of employment) (The Senate, 2018b). Employment in renewable energy activities accounted for 0.1% of employment in 2016/17, of which about half was in New South Wales and Queensland (Figure 3.10). The level has decreased since 2011 due to the reduction of feed-in tariffs in states and territories but it was picking up again in 2016 (ABS, 2018).

Figure 3.10. Employment in renewable energy activities

Ensuring an inclusive transition

A just transition of the workforce, as recalled in the Paris Agreement, builds on engaging with stakeholders (trade unions, employers, communities) to address negative effects on labour markets and support development of new jobs and the “greening” existing ones. Anticipating and addressing any negative impact from possible restructuring on regions, households, assets and companies will help in achieving broad support. This is essential for moving the green growth agenda forward. For example, some jurisdictions are looking at the social consequences of closing coal power plants (Box 3.8).

Box 3.8. Addressing the impact of closing coal power plants

Coal power stations are located close to major coalfields, thus concentrating coal activities in specific regions, e.g. near Melbourne, south of Perth and north and west of Sydney. There may be little employment diversification, so power station closures can result in large numbers of job losses. Since 2012, ten coal power plants have closed and three have announced their decommissioning. The latest to close, on short notice, was Hazelwood, which employed about 750 people. Its closure conveyed to the Australian and Victorian governments the need to plan for mitigation of the social impact through measures such as scaling up skills in the region, attracting new investment and providing financial support.

Other countries are facing similar challenges. Canada, one of the 19 OECD countries in the Powering Past Coal Alliance (whose membership also includes subnational governments and organisations), decided to accelerate its phase-out of coal, with a target date of 2030. The Canadian province of Alberta developed a range of financial, employment and retraining measures for workers being affected, including Indigenous people.

An important aspect of a just transition is to identify communities at risk and support economic diversification through long-term transition plans. In a first step in this direction, the Australian Energy Market Commission has recommended that Australia’s coal power stations be required to provide three years’ notice of closure.

Source: The Senate (2017), Retirement of coal fired power stations; IEA (2018), Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Australia 2018 Review; OECD (2017), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Canada 2017.

Skills development is the key to supporting employment in environmental goods and services. Australia runs environmental education and training programmes (Chapter 2). It also supports the best use of Indigenous knowledge and skills, especially in natural resource management. The Indigenous Rangers and Indigenous Protected Areas programmes have helped deliver economic, social, cultural and environmental outcomes. Together, they created more than 2 900 jobs through full-time, part-time and casual employment.

Another crucial element is identifying and directly supporting job creation. Queensland, acknowledging risk arising from climate change (e.g. the threat to the Great Barrier Reef puts 64 000 jobs at risk, along with 10 coal power plants, half of them more than 25 years old), included actions to develop low-emission jobs in its 2017 Climate Change Strategy. Queensland also supports Indigenous Land and Sea Rangers (76 Indigenous rangers were trained and hired in 2017) to create jobs in conservation. Similarly, employment and training opportunities, especially within Indigenous communities, were provided through the Green Army programme for young Australians (scrapped in 2018) and the National Landcare Program (Chapter 4).

Environment, trade and development

Mainstreaming environmental considerations in development co‑operation

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act requires the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade12 (DFAT) to assess whether an aid activity is likely to cause significant impact on the environment and to take steps to avoid and/or mitigate negative impact. The 2014 Environment Protection Policy for the Aid Program defines principles (e.g. do no harm, assess and manage environmental risk and impact, promote improved environmental outcomes) and operational procedures to meet this requirement and commitments made under multilateral environmental agreements (DFAT, 2014). The screening process is well established and sets levels of environmental risk and referral thresholds (OECD, 2018g).

The 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper acknowledges that environmental degradation and climate change are risks for security and prosperity in the Pacific (DFAT, 2017a). Australia has yet to clearly articulate an approach to mainstreaming environment and climate in its aid programme, however, beyond a safeguards approach. The OECD recommendation in Development Assistance Committee (DAC) peer reviews of 2008, 2013 and 2018, to ensure that environmental concerns are integrated at all levels (from top strategic management and programme design to implementation), with sufficient capacity and resources, remains valid. DFAT is developing a plan to address this shortcoming (OECD, 2018g).

Net official development assistance (ODA) disbursements have been declining in real terms since 2012, and are expected to continue to decline to 2021/22, despite continued economic growth (Treasury, 2018b). In 2017, ODA accounted for 0.23% of gross national income (GNI), below the DAC member average of 0.31% and far from the UN target of 0.7% – a target reiterated in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda (SDG 17.2). Australia had previously committed to reach 0.5% of GNI by 2016/17, but this target was abandoned. The government does not support a time-bound, percentage of GNI aid target. In 2016, Australia was among the top five DAC providers of bilateral ODA to small island developing states. However, like most DAC donors, it fell short of the target of providing at least 0.15% of GNI to least developed countries. About 70% of ODA was provided bilaterally, the rest being channelled through multilateral organisations. All the ODA was provided through grants (OECD, 2018h).

After a decrease over 2011-15, Australia’s aid focusing on environment rose to 23% of bilateral allocable aid in 2016, remaining low compared to the DAC average of 33% (Figure 3.11). The main recipients were Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu and other Pacific islands states (OECD, 2018i). Environment-related ODA is multisector. In 2016, the largest grant reported was that of the Australia NGO Cooperation Program, a partnership between DFAT and non-government organisations, whose activities span many countries and projects.

Australia has also provided multilateral environment-related ODA: it is among the top ten donors to the Green Climate Fund, having committed AUD 200 million over 2015-18. Australia chaired the Board of the Green Climate Fund in 2011-12, 2016 and 2017. It also contributes to the Climate Investment Funds (AUD 187 million over 2009-18) and the Global Environment Facility (AUD 93 million over 2014-18) to provide a range of grants in the Indo-Pacific region, especially on adaptation.

Figure 3.11. Climate-related aid increased in 2016 but remains low

Australia is delivering on its 2015 commitment to provide AUD 1 billion in climate finance over five years by reallocating the existing aid budget towards climate adaptation and mitigation. Climate-related bilateral allocable aid increased in 2016, but at 19% it remained below the DAC average of 26% (OECD, 2018h). In 2015, developed countries committed to jointly mobilise USD 100 billion a year by 2020 to help developing countries tackle climate change. Australia and Japan consider that financing for high-efficiency coal plants, which is usually not included when tracking climate finance, should be considered a form of climate finance (OECD, 2015c).

Trade and environment

Australia scores well on most trade facilitation indicators (OECD, 2018j). Free trade agreements (FTAs) and trade liberalisation raised its international trade to 40% of GDP in 2016, below the OECD average due to the country’s remoteness. Over the past decade, Australia signed FTAs with Chile, Malaysia, Korea, Japan, China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. All include general environmental provisions but those with Korea and Malaysia include a separate section on the environment. With agreements signed before 2007 (with New Zealand, Singapore, Thailand and the United States) taken into account, FTAs with environmental provisions cover nearly 70% of Australia's total trade (DFAT, 2017b). An FTA with Peru and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, signed in 2018 but not yet in force, each have an environmental chapter.

Australia chairs the negotiations to forge a plurilateral Environmental Goods Agreement in the framework of the World Trade Organization. The negotiations, if successful, will phase out import tariffs on a range of goods used to control pollution, monitor the environment or improve environmental performance. As of end 2018, the prospect of the negotiations was uncertain. Australia has reduced tariffs to 5% or less on a range of environmental goods, in line with its commitment with other Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation members. The global market for environmental goods was estimated to be worth USD 1 trillion when the negotiations were launched in 2014. In 2014/15, Australia’s environmental goods exports were estimated at USD 1.5 billion and imports at USD 8.7 billion (Productivity Commission, 2017c).

Australia’s National Contact Point (NCP) was established in 2000 to promote the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. An independent review commissioned by the government identified room for improving its visibility, accessibility, transparency and accountability as the Guidelines require (Newton, 2017). In 2017, the Australian NCP had no dedicated budget and only 1.5 full-time equivalent staff members, from the Treasury. The review recommended transitioning to a multipartite structure with adequate funding and support (Newton, 2017; OECD Watch, 2017). Complaints can be raised to an NCP if a multinational enterprise is believed to have breached the Guidelines. Of the 11 specific instances handled by the Australian NCP since 2005, 3 related to the environment (OECD, 2017e, 2018k). There is no mandatory corporate social responsibility reporting in Australia, unlike in a growing number of OECD countries (Baron, 2014). In terms of voluntary reporting requirements, the ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations cover disclosure of economic, environmental and social sustainability risks for listed entities.

The Export Finance and Insurance Corporation (EFIC), the government’s export credit agency, has developed a policy and procedures to implement the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Common Approaches for Officially Supported Export Credits and Environmental and Social Due Diligence, along with the Equator Principles. EFIC screens all transactions for environmental and social risk and undertakes a risk evaluation where potential for environmental and/or social risk is identified. It has committed to engage an independent environmental and social expert to review the application of its policy and procedures every two years (Ernst & Young, 2016). Details of projects with potentially significant adverse environmental and/or social risks are disclosed (EFIC, 2018a). EFIC finances few such mining projects. In 2015, OECD countries agreed to restrict support through export credits for construction of certain coal plants. Korea and Australia negotiated an exception allowing construction of less efficient small coal-fired power plants in developing countries (OECD, 2017f). Australia does not report significant amounts of officially supported export credits for electric power generation projects (OECD, 2015d; EFIC, 2018b). There is little information on the level of EFIC funding for fossil fuel projects.

References

ABARES (2017), Australian Water Markets Report, Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra, www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/research-topics/water (accessed 12 February 2018).

ABS (2018), Employment in Renewable Energy Activities, Australia, 2016-17, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/allprimarymainfeatures/58E7A93514A911F0CA25827B001AA6D2?opendocument (accessed 27 June 2018).

ABS (2014), Discussion Paper: Towards an Environmental Expenditure Account, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/7BA7EA1A708593D1CA257D2B00131795/$File/4603055001_august%202014.pdf.

Aither (2018), Water Markets Report: 2017-18 review and 2018-19 outlook, Aither, Melbourne, www.aither.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Aither-Water-markets-report-2017-18-3.pdf.

ANAO (2017), Low Emission Technologies for Fossil Fuels, Australian National Audit Office, Canberra, www.anao.gov.au/work/performance-audit/low-emissions-technologies-fossil-fuels.

Arcadis (2017), “Sustainable Cities Mobility Index 2017, Bold Moves”, Arcadis, Amsterdam, www.arcadis.com/assets/images/sustainable-cities-mobility-index_spreads.pdf.

Australian Government (2018a), Environmental Economic Accounting: A Common National Approach Strategy and Action Plan, prepared by the Interjurisdictional Environmental-Economic Accounting Steering Committee for the Meeting of Environment Ministers, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/f36c2525-fb63-4148-8f3c-82411ab11034/files/environmental-economic-accounting-strategy.pdf (accessed 10 June 2018).

Australian Government (2018b), Budget Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1 2018-19, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, www.budget.gov.au/2018-19/content/bp1/download/BP1_full.pdf.

Baron, R. (2014), “The Evolution of Corporate Reporting for Integrated Performance”, background paper for the 30th Round Table on Sustainable Development, 20 June, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/sd-roundtable/papersandpublications/The%20Evolution%20of%20Corporate%20Reporting%20for%20Integrated%20Performance.pdf.

BITRE (2016), Toll Roads in Australia, Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development, Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics, Canberra, https://bitre.gov.au/publications/2016/files/is_081.pdf.

Caldecott, B., J. Tilbury and Y. Ma (2013), Stranded Down Under? Environment-related Factors Changing China's Demand for Coal and What This Means for Australian Coal Assets. Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, Oxford. www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/publications/reports/stranded-down-under-report.pdf.

Callaghan, C. (2017), Petroleum Resource Rent Tax Review, The Treasury, Canberra. https://static.treasury.gov.au/uploads/sites/1/2017/06/R2016-001_PRRT_final_report.pdf.

Campey, T. et al. (2017), Low Emissions Technology Roadmap, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Canberra, www.csiro.au/~/media/EF/Files/LowEmissionsTechnologyRoadmap-Main-report-170601.pdf.

CCA (2017), Review of the Emissions Reduction Fund, Climate Change Authority, Canberra, http://climatechangeauthority.gov.au/sites/prod.climatechangeauthority.gov.au/files/files/CFI%202017%20December/ERF%20Review%20Report.pdf.

CEFC (2017), CEFC Annual Report 2016–17, Clean Energy Finance Corporation, Sydney, http://annualreport2017.cefc.com.au.

CER (2018), Safeguard Facility Reported Emissions, 2016-17: National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Data, www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/NGER/National%20greenhouse%20and%20energy%20reporting%20data/safeguard-facility-reported-emissions/safeguard-facility-emissions-2016-17 (accessed 11 May 2018).

Climate Bonds Initiative (2017), Bonds and Climate Change: The State of the Market 2017, www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi-sotm_2017-bondsclimatechange.pdf.

Department of Industry (2016), Australian Innovation System Report 2016, Department of Industry, Canberra, https://industry.gov.au/Office-of-the-Chief-Economist/Publications/Documents/Australian-Innovation-System/2016-AIS-Report.pdf.

Department of Industry (2013), Australian Innovation System Report 2013, Department of Industry, Canberra.