This chapter discusses developments in Korea that have implications for the role of labour migration. The development of the Korean economy is presented, in terms of its segmentation. The demographic trend of an aging population and a shrinking youth cohort is described. The chapter notes the high rate of tertiary education among young Koreans, and the relatively low education and skill level of the generation of Koreans currently heading into retirement. Vacancy data suggests continued demand for workers in firms offering low-quality jobs requiring little education. The chapter notes that young Koreans are an ill-fit with the jobs being vacated by retiring older workers.

Recruiting Immigrant Workers: Korea 2019

Chapter 1. Context for Labour Migration

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

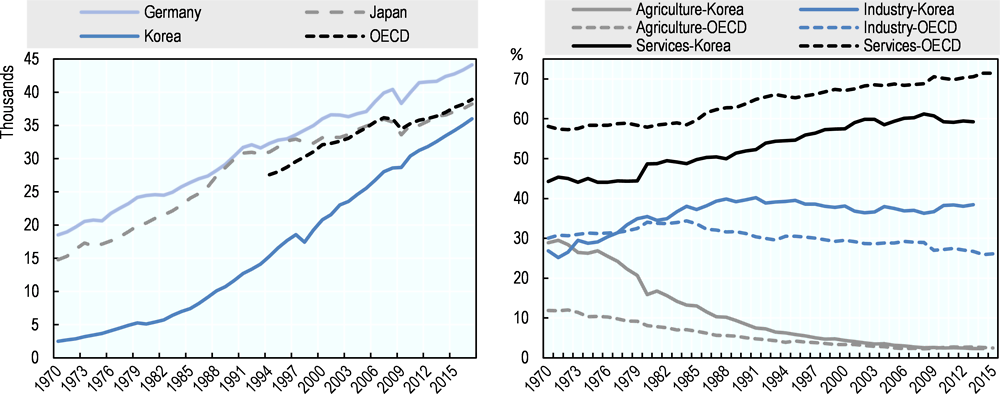

Korea’s economy: growth and sectors

From one of the least developed countries in the world in the late 1950s, Korea has become one of the most developed. From a situation of widespread unemployment and poverty, wages rose rapidly across the Korean economy between the 1960s and 1980s, and near-full employment (unemployment rates of 2‑4%) was achieved by the late 1980s. In 2016, Korean GDP per capita was less than 10% below the OECD average, and Korea ranked in the upper half of OECD countries in terms of GDP per capita.

Figure 1.1. Korea’s economic development has been impressive

a. Weighted average of the 35 OECD countries.

b. Unweighted average of 33 OECD countries (Israel and Switzerland were excluded due to unavailable data).

Source: OECD Productivity Database, http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=PDB_LV, Productivity and ULC – Annual, Total Economy, “Level of GDP per capita and productivity” for Panel A; and OECD Annual National Accounts Database, http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SNA_TABLE6A, Detailed Tables and Simplified Accounts, “Table 6A. Value added and its components by activity, ISIC Rev. 4” for Panel B.

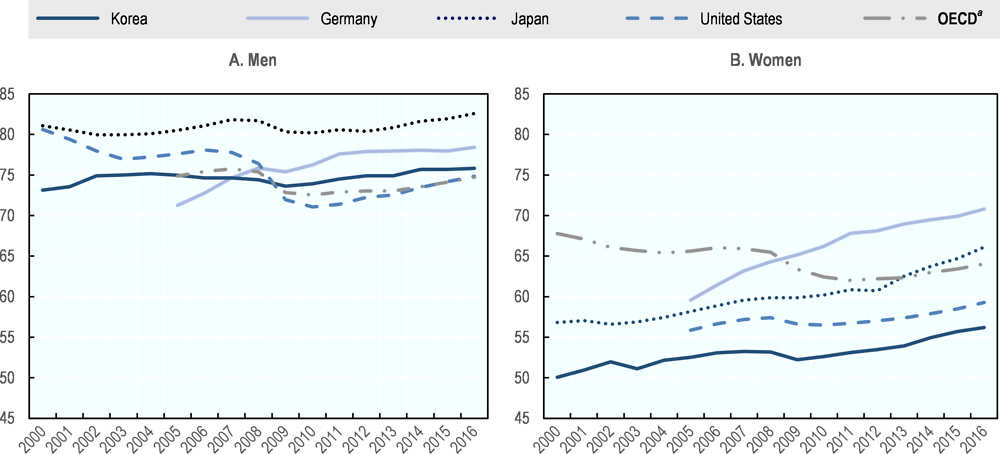

The employment rate in Korea has been rising for the past three decades, from 57% in 1986 to 63.9% in 1997, prior to the crisis of the late 1990s, when it fell to 59.2%. The 2000s saw employment rise again, to 63.9% in 2007, and only a one point decline during the crisis of the late 1990s. It is now at record levels, of 66.3% in 2016. However, these high employment levels hide a wide gap in the employment rate between men and women. Since 2000, the employment rate for men has been largely constant, close to the OECD level; while the employment rate for women has been slowly rising but remains almost 20 points below that of men, twice the gap of the OECD as a whole (Figure 1.2). Further, contrary to other OECD countries, Korea’s gender employment gap increases with the level of education. In 2015, the gender employment gap (the difference between male and female employment rate as a share of the male employment rate) for tertiary‑educated women was 30%, the highest among OECD countries. The gap for less educated women was smaller, less than 20%, and below the average for OECD countries.

Figure 1.2. The employment rate for women is much lower than for men

Note: a) Weighted average of OECD countries.

Source: OECD Employment Database, www.oecd.org/employment/database.

In terms of sectors of employment, in 2016 services were the main type of sector, accounting for 60% of employment. The manufacturing sector accounted for 14.6%. However, the share of employment in manufacturing fell by just 0.3 percentage points from 2006 to 2016, compared with about 2% in other OECD countries, indicating the continuing importance of manufacturing.

Regardless of sector, however, employment in Korea has increasingly been characterised by a dual labour market. Large enterprises and the public sector offer higher wages and better working conditions than small and medium-sized enterprises. SMEs often have low firm survival rates and offer low-quality jobs (minimum wage or worse, poor working conditions, high turnover).

A distinguishing feature of employment in Korea is the outsized role of SMEs (firms with fewer than 300 employees) in terms of employment. This is particularly true in the service sector, where SMEs comprise 90% of employment and 85% of added value. In the manufacturing sector, SMEs account for 81% of employment, but only 41% of added value. In other words, productivity in manufacturing SMEs is about 5.5 times lower than in large manufacturing firms. This gap is the largest among OECD countries. By comparison, in Japan the ratio is about 1.3, while in the United States, SMEs in manufacturing are more productive than large firms.

Employment in large firms has been declining since the 1990s, from 22.6% in 1993 to 13.6% in 2014. In manufacturing, the decline in large firm employment has been more severe: from 35.3% in 1993 to 19% in 2014. There has been a corresponding boom in the number of small (10‑19 employees) and very small (1‑9 employees) firms. Self-employment is quite high, at 25.5% in 2016, when compared with the OECD average of 15.8%. The majority of the self-employed are former wage workers, often early retirees.

Demographic context

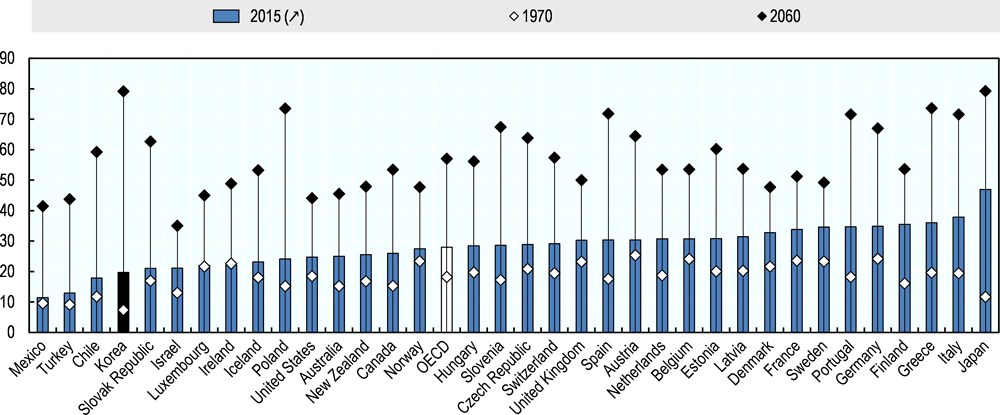

Korea is among the fastest aging populations in the OECD. The fertility rate has been low since the 1980s, and has stood at 1.2 children per woman since 2013, the lowest in the OECD. The largest birth cohorts were in the late 1960s and early 1970s. By the late 1980s, cohort size was about 60% that of the late 1960s; today, births are less than 40% of the peak years in the 1960s.

The consequences on the working age population are significant. Although the age group 25‑49 is the largest segment of the working age population, it has begun to decline since 2008. The age group 15‑24 has been gradually declining since 1991. The working age population peaked at 35 million in 2016 and has started to decline. As the younger working age population diminished, the 50‑64 cohort already exceeded that of the 15‑24 group by the early 2000s. The 50-64 is projected to soon approach the size of the 25‑49 population. However, even the 50‑64 population is predicted to decrease beginning 2024. Following projections from Statistics Korea, the share of the working-age population is expected to decline from 73.1% in 2013 – the highest in the OECD - to 63.1% in 2030 and 49.7% in 2060. At that point, the population over the age of 65 is projected to comprise 40.1% of the population, and the population under 15 to comprise just 10.2%. The projection model used here does not, however, include migration.

According to UN projections, the old-age dependency ratio in Korea will increase more than in any other OECD country between 2015 and 2060 (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. Korea will have the largest increase in its old-age dependency ratio between 2015 and 2060

Source: Calculations from United Nations, World Populations Prospects - 2015 Revisions.

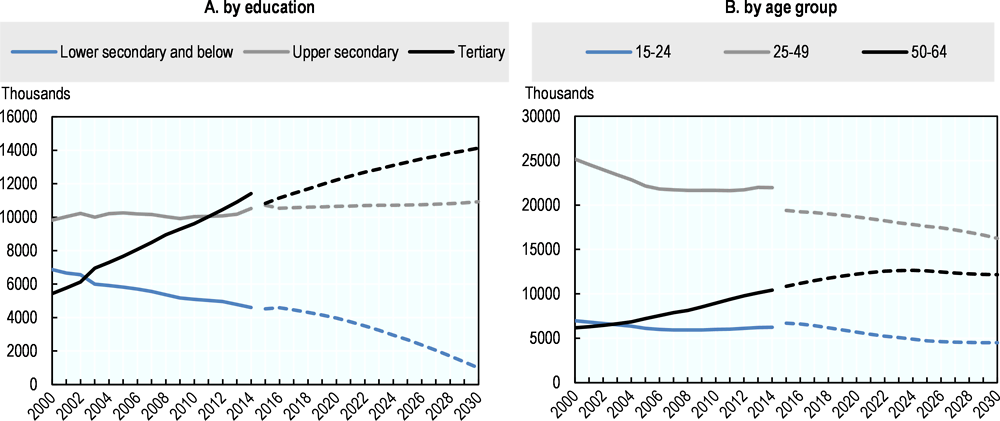

A highly educated youth population

In addition to the rapidly aging population and imminent decline in the working‑age population, another particularity in Korea is the extremely high educational attainment of the labour force, especially the younger age cohorts. Korea has the highest proportion of people aged 25 to 34 with tertiary education among OECD countries, and a large share of students progresses into tertiary education. The high school graduation rate is the highest among the OECD countries, above 93%. According to the Ministry of Education, 77.3% of general high school graduates and 32.8% of vocational high school graduates were enrolled in post‑secondary programmes in 2017. This represents a decline from 2009 (when the share was 85% and 74% respectively). Until recently, both general and vocational high schools had encouraged students to pursue post-secondary studies.

The highly educated are expected to account more than half of the people in the labour force by the mid-2020s (Figure 1.4). The surge in tertiary educated became evident from the beginning of the 2000s – the number of highly educated exceeded the low educated in 2003 and the medium educated in 2012. At present, 86% of the active population has at least upper secondary education or above, of which 52% is tertiary educated.

According to projections by KEIS (Park et al., 2015[1]), this trend is expected to continue (Figure 1.4, Panel A). The KEIS projections even appear conservative, since the actual trend line is steeper through 2016 for both less educated and more educated workers.

Figure 1.4. Decline in active population is only in the least-educated segment

Note: Panel A; Values until 2010 are real observed value. Panel B: Observed until 2014.

Source: Panel A: Society with 100-year life expectancy, Prospects and Counterparts on Employment and Job 2010, KEIS (Park et al., 2015[1]). Panel B: EAPS (2000‑14); Population Projections for Korea: 2010‑30 (Based on the 2010 Census), Kostat

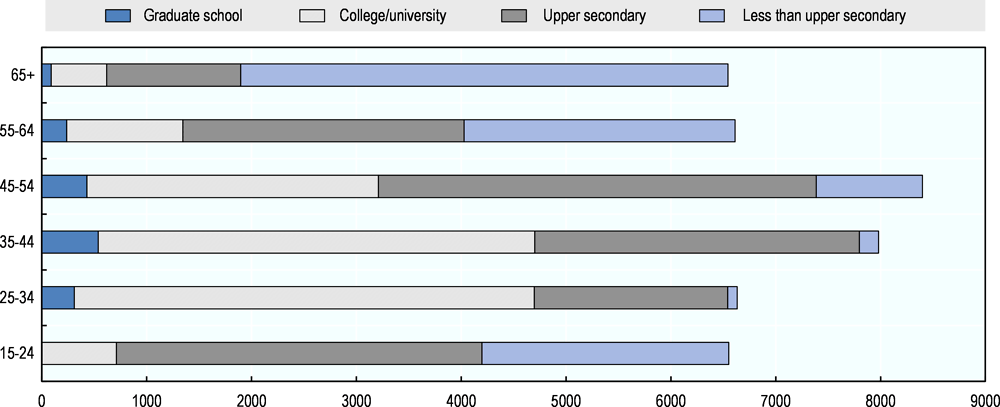

When looking into working-age population divided by age and education level, the evolution is even more striking. Figure 1.5, based on the 2015 Census, shows that the age cohort entering the labour force has very different characteristics from that which is leaving the labour force. Regarding educational attainment, generations entering and leaving the working-age population have opposite characteristics. Among those 55 to 64 years of age, 39% have less than upper secondary education. The low-educated accounted for an overwhelming majority among those 65 and older in 2015, who were leaving or have largely left the labour market by now. There are now few similarly low educated workers to step into their shoes.

Significant gender disparity concerning education attainment is another feature of this generation compared to the younger population (82.8% of women aged over 65 do not have high school degrees). On the other hand, the educational attainment is quite different for the middle-aged working population. Among those 45‑54, the upper-secondary educated are the majority for the first time, and the tertiary educated exceed high-school graduates among those aged 35‑44. The situation changes markedly for the youngest generation. 70.8% out of those aged 25‑34 are tertiary educated and the gender disparity disappears. As for those aged 15‑24 who are entering the labour force, not only does the overall size of the population diminish, but there is a further tendency towards higher education. Considering that population in schooling is included in this group and 68.9% of the upper secondary graduates are enrolled in post-secondary school (Ministry of Education, 2017[2]), it is likely that the 15‑24 cohort would follow a similar pattern as the 25‑34 cohort.

Figure 1.5. Younger cohorts are much better educated than older cohorts

Source: Kosis, 2015 Census.

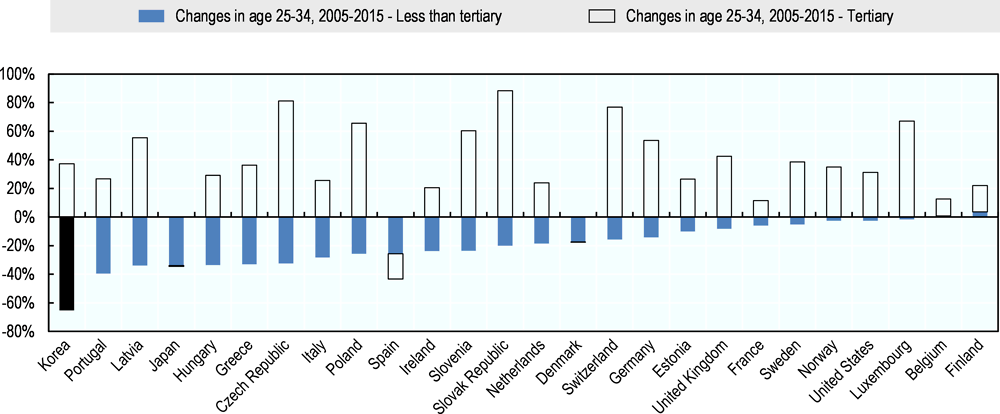

There are now few young people to take low-skilled jobs. The combined effect of rising education levels and shrinking youth cohorts is that there are relatively few young people with less than tertiary education. Indeed, the population entering working age with less than tertiary education is much smaller than it was just a decade earlier. The number of people aged 25‑34 in Korea with less than tertiary education fell from 4 million in 2005 to 1.4 million in 2015. The dramatic change in the Korean labour force occurred in a very short time span; no other OECD country has seen a similar contraction over such a short period (Figure 1.6). Further, over the same period, the number of people aged 25‑34 with tertiary education increased from 4.2 million to 5.7 million. As a result, there is a significant gap between the qualifications of vacancies that the older generation is creating with their retirement, and that of the jobs for which the younger generation has trained and which it is willing to fill. Young high-skilled Koreans face a job market in which there are not enough high-skilled jobs, but they have not shown a great interest in taking up employment – especially in manufacturing jobs in SMEs – where skill demands are basic, conditions are poor and wages are low.

Figure 1.6. Korea has seen the largest decline in the OECD in its less-than tertiary educated youth cohort over the past decade

Source: Labour Force Surveys.

Even among the non-tertiary educated, young Koreans have very high skill levels. According to PIAAC, Korean young people are among the most skilled in the OECD, with literacy and numeracy scores comparable to the highest levels within the OECD (OECD, 2013[3]). Remarkably, literary proficiency among Korean young people with less than secondary education is very high, comparable almost to those with tertiary education and much higher than similarly-educated young people in other OECD countries. This suggests a very high quality education system, and that even non-tertiary educated Koreans may be overqualified for jobs requiring only basic skills and involving routine tasks. Also notably, the gap in PIAAC literacy and numeracy scores between the younger (16‑24) and older (55‑65) groups is very wide – 50 points – pointing to a large gap between the skills of younger and older workers. This is the largest gap within the OECD countries, and again raises the question of who will be willing to step into the jobs vacated by the older, retiring generation.

Current labour market conditions and labour shortages

Current labour market conditions in Korea are favourable in comparison with other OECD countries. The proportion of working-age population (15‑64) in employment was at 68.3% in 2015, although the absolute size of the working age population, as noted, has begun to diminish. Employment levels remained high during the global financial crisis of the late 2000s. In 2016, the Korean harmonised unemployment rate dropped to 3.7%, the second-lowest in the OECD following Japan, although it crept up to 3.8 by mid-2018. The inactivity rate, while falling slightly from 31.3% in 2016 to 30.7% in 2018, remains however among the highest in the OECD. This is driven by particularly high inactivity rates of women (56.1% in 2016); among men, Korea’s participation rate was above the OECD average.

The situation for youth on the labour market in Korea is noteworthy for its low unemployment rate and low activity rate. In 2017, the unemployment rate was 9.8%, slightly below the OECD average of 11.9%. However, the participation rate of young people is relatively low in international comparison, especially in light of their high education attainment. The NEET (not in employment, education or training) rate in Korea, 18% in 2017, is slightly higher than the OECD average, but higher-educated Korean youth are more affected than those with lower education, the opposite of the situation in most other OECD countries. Young people in fact postpone entry to the labour market, investing further in their human capital in an attempt to pass selection exams and secure employment in the primary labour market – large firms and the public sector. The inactivity of highly-educated young people also suggests an unwillingness to accept jobs for which they are overqualified.

The participation rate among older workers, on the other hand, is relatively high. Many Koreans aged 50 or above have retired from their jobs in the primary labour market but, due to low income, must seek income through poor quality jobs in small enterprises or in self-employment in their “second career” (OECD, 2018[4]).

Therefore, the labour force reserve largely comprises highly educated young people who are delaying their entry into employment, and women who have left the labour force (due to childbearing, but also to a “glass ceiling” preventing them from finding a job in the primary labour market).

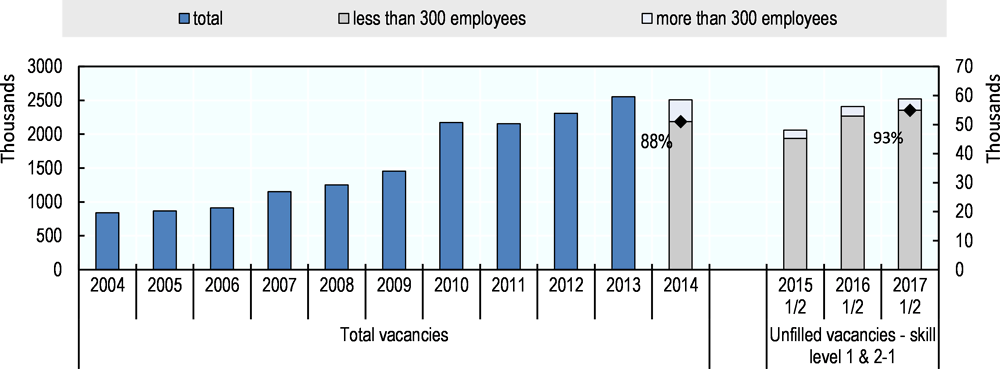

The number of vacancies posted on Worknet, the employment information service run by the Ministry of Employment and Labour for job matching, has been steadily increasing, from 841 000 in 2004 to 2.5 million in 2013. Of those vacancies, 88% were posted by businesses with less than 300 employees in 2014 (Figure 1.7). In terms of vacancies that went unfilled according to the Occupational Labour Force Survey at Establishments data of the MOEL in the first semester of 2017, 67% of the unfilled vacancies were low-skilled and most of the unfilled low-skilled jobs (93%) were among SMEs.

Figure 1.7. The number of vacancies are rising, especially in less skilled occupations

Note: 1) The share of vacancies in SMEs in 2014 comes from “March 2015 Employment Issue” of KEIS. 2) The skill level classification employed in the Occupational Labour Force Survey at Establishments classifies the skill level by five categories with regards to work experience, educational attainment and certificates: skill level 1 refers to an occupation with no requirement for experience, diploma, and certificate; skill level 2‑1 refers to an occupation that requires one to two years of experience or technician certificate or educational attainment of high school graduate or less.

Source: Worknet, Occupational Labour Force Survey at Establishments, Ministry of Employment and Labour, 2004‑17.

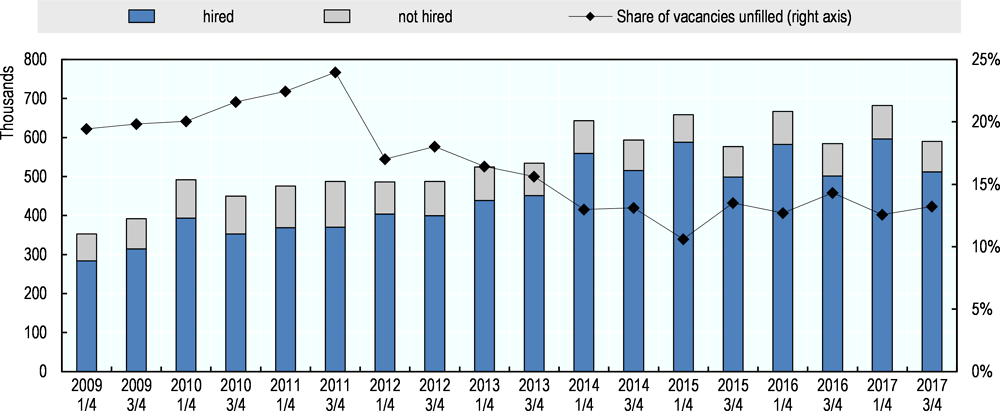

Labour shortages have been an issue in Korea since the early 1990s, especially in low-skilled manufacturing jobs, where shortage indices have been higher than for skilled workers (Park, 2002[5]). In the mid-2000s, shortage rates were twice as high for low-skilled jobs as for higher-skilled jobs (Lee and Park, 2008[6]). Since the crisis of the late 2000s the number of job vacancies has been increasing, even as it has become easier to fill positions (Figure 1.8). Vacancies in SMEs reached almost 700 000 in the first quarter of 2017, although only one in eight went unfilled.

Examining vacancies, labour shortages in Korea appear concentrated in a few sectors and a few occupations. The Occupational Labour Force Survey at Establishments (2017) indicates the difficulties by sectors. In spite of employers’ recruitment efforts, a number of occupation types were difficult to fill. In the second half of 2017, 11.7% of overall vacant positions could not be filled. The share of vacancies which could not be filled was much higher in driving and delivery (34.6%), food processing (22.2%), and materials, chemicals, textile and clothing (24.4%). When looking at unfilled vacancies by skill level, the number of unfilled positions was concentrated in low skill positions, level 1 and level 2‑1 in particular.

Figure 1.8. The share of vacancies which can’t be filled has been declining

Note: Establishments with five or more employees are included in the panel. The reference period is.1.1‑3.31 for first quarter and 1.7‑30.9 for the third quarter each year.

Source: Occupational Labour Force Survey at Establishments.

There are still many low-quality jobs

Low quality jobs – low wages, poor employment prospects, and poor working conditions – are widespread in Korea, especially in small and microenterprises. Employment in SMEs is associated in Korea with lower wages than in large companies. Hourly wages in companies with 10‑29 employees are half those in large enterprises; in firms with fewer than five employees, wages are only one-third that level. Overall, turnover in Korea is higher than in any other OECD country. In 2015, 30.9% of employees in Korea were in their jobs for shorter than one year – compared with an OECD average of 17.6% (OECD, 2018[7]). This is highest in the smallest firms - 50.7% workers in enterprises with fewer than five employees have job tenure of less than one year.

Many workers in SMEs earn minimum wage, and the minimum wage is low. The statutory Minimum Wage (MW) as of January 2017 was KRW 16.2 million per year for a full‑time worker, around 42% of the median wage, putting Korea’s minimum wage in the lower third of OECD countries which have a statutory MW. Around 15% of all workers in Korea (17.4% in 2017) earn MW – this is much higher a share than in most other OECD countries where typically only around 5% or less earn the minimum wage.

The changing educational composition of the working age population has not meant the disappearance of low-productivity, low-wage jobs. Further, the minimum wage is not enough to keep families out of poverty, especially for single-income households. The minimum wage is planned to increase gradually by about 30% from 2018 to 2020; however, the increase may not necessarily raise real earnings in the absence of enforcement. Further, it will not affect the wage of the self-employed.

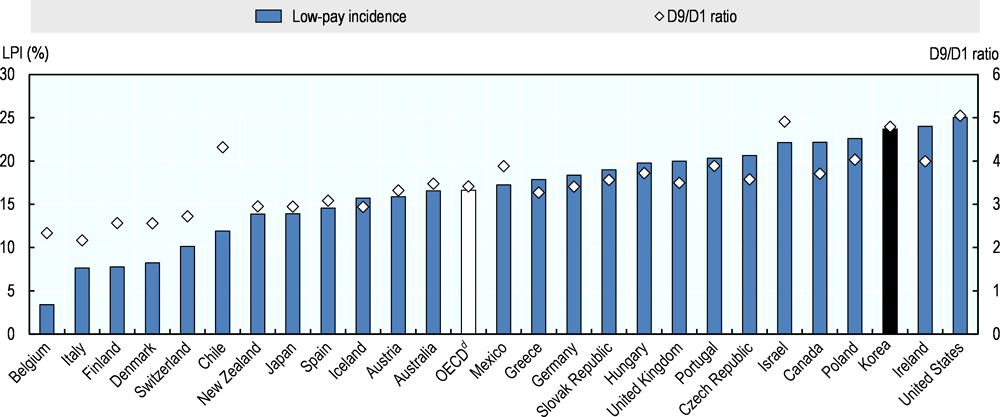

In addition to MW employment, there are many other low-paid jobs. Almost one in four Korean workers earns less than two-thirds of the median earnings; this is one of the highest rates of low-paid work in the OECD (Figure 1.8). Further, workers in the ninth income decile earn 4.7 times as much as those in the first income decile, an earnings dispersion which is also among the highest in the OECD (OECD, 2018[7]).

Figure 1.9. Korea has a high rate of low-paid work and of earnings dispersion

Note: a) The incidence of low pay refers to the share of workers earning less than two-thirds of median earnings. b) Earnings dispersion is measured by the ratio of 9th to 1st deciles limits of earnings. c) Data refer to 2011 for Israel; to 2012 for Spain; and to 2014 for Australia, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal and Switzerland. d) Unweighted average of the 26 countries shown above.

Source: OECD Earnings Distribution Database, www.oecd.org/employment/emp/employmentdatabase-earningsandwages.htm.

In summary, Korea’s labour force is undergoing a profound transition, already well‑advanced, towards a much higher-educated working-age population. This is especially true for youth cohorts, which are progressively smaller. There are fewer and fewer young people with lower educational qualifications. Young people with higher education tend to invest in further qualifications in an attempt to enter the regular labour market, rather than accept non-regular employment or low-quality jobs. The labour supply of less educated is aging and will soon start to diminish rapidly. At present, there are many poorly paid jobs, filled by workers with skill profiles which are becoming increasingly scarce. The difficulty in filling jobs which pay poorly and which do not require high levels of education points to the challenge in how Korea will meet the labour needs in these jobs. The jobs themselves are low-productivity, suggesting that without productivity gains, it will be difficult to increase wages substantially. For some jobs, it may be possible to increase productivity and wages, attracting Korean workers. For other jobs, in SMEs in the manufacturing sector where margins and capital investment are low, the absence of low-cost labour may force production cuts, or a loss of competitiveness compared to competitors in other countries. Even beyond manufacturing – in agriculture and services – the same question appears. It is in this context that labour migration has begun to play an important role.

References

[6] Lee, K. and S. Park (2008), “Employment Structure and Effects of the Foreign Workforce”, KLI Monthly Labor Review, Vol. September, https://www.kli.re.kr/kli_eng/selectBbsNttView.do?key=220&bbsNo=31&nttNo=100745&searchY=&searchCtgry=&searchCnd=all&searchKrwd=&pageIndex=7&integrDeptCode= (accessed on 13 November 2017).

[2] Ministry of Education (2017), Educational Statistics Analaysis (교육통계 분석자료집) 2017, KEDI, Seoul.

[7] OECD (2018), Towards Better Social and Employment Security in Korea, Connecting People with Jobs, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264288256-en.

[4] OECD (2018), Working Better with Age: Korea, Ageing and Employment Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264208261-en.

[3] OECD (2013), OECD Skills Outlook 2013: First Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204256-en.

[1] Park, M. et al. (2015), 100세 사회 고용․ 일자리 분야 전망 및 대응방안 (100 year old social employment – Occupational prospects and countermeasures, KEIS), http://keis.or.kr/user/extra/main/2102/publication/publicationList/jsp/LayOutPage.do?categoryIdx=131&pubIdx=1648&onlyList=N.

[5] Park, W. (2002), “The Unwilling Hosts: State, Society and the Control of Guest Workers in South Korea”, Asia Pacific Business Review, Vol. 8/4, pp. 67-94, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713999161.