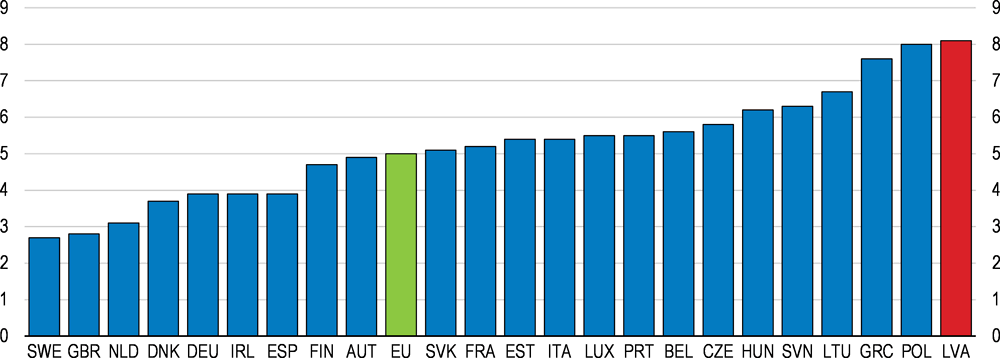

Economic growth is strong and income convergence continues, even though at a slower pace than before 2008 (Figure 1). The labour market is tight, as unemployment fell to its lowest rate in ten years and vacancies are rising fast. Wage growth has been strong supporting household purchasing power. Despite increasing labour costs, Latvian exporters have remained competitive and gained market shares. The macroeconomy appears balanced overall with inflation, public debt and the deficit under control. Financial markets look stable, sustained by sound macroprudential policy.

OECD Economic Surveys: Latvia 2019

Key policy insights

Growth is strong, but inequality remains high, and ageing is a challenge

Figure 1. GDP growth is strong and income convergence continues

1. Percentage gap with respect to the weighted average using population weights of the highest 17 OECD countries in terms of GDP per capita and GDP per hour worked (in constant 2010 PPPs).

Source: OECD National Accounts Database; OECD (2019), Economic Policy Reforms 2019: Going for Growth (forthcoming).

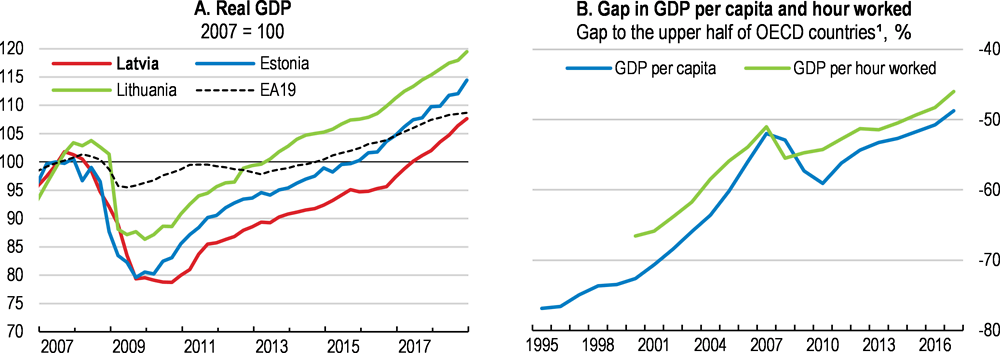

Latvia faces considerable headwinds from a rapid demographic transition. The working age population is declining fast (Figure 2) owing to ageing and outmigration, which has reduced the population by 20% since 2000. A large fraction of emigrants is skilled, contributing to skill shortages, dampening economic growth and putting pressure on the adequacy of pensions and health care. Latvia has taken action to confront these challenges, including by upgrading its education system and active labour market policies.

Figure 2. The working age population is shrinking fast

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017), World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, DVD Edition; Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia.

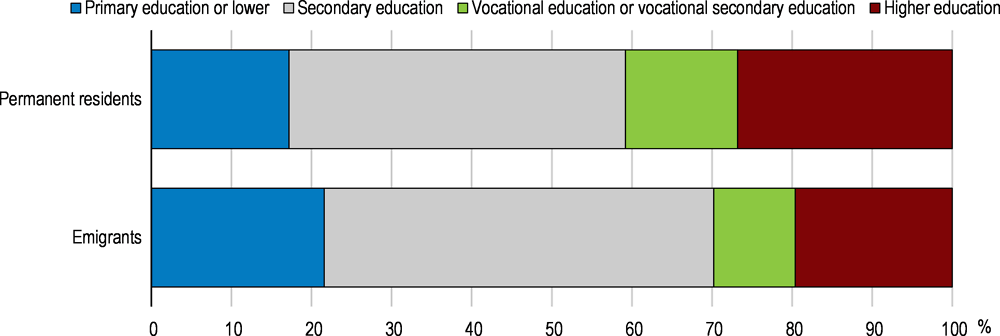

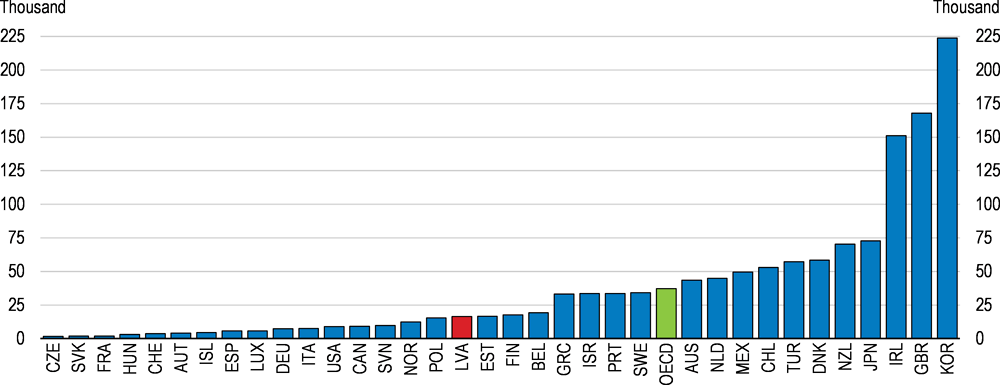

Box 1. Latvia’s emigration challenge

Between 2008 and 2017, about 260 thousand people emigrated from Latvia, amounting to 13.5% of the population in 2017. The emigration flow peaked in 2009 and 2010 when Latvia lost a little less than 2% of its population in each year. In 2017 more than 80% of emigrants were of working age, and more than half were aged between 20 and 39, according to the data by the Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. The pace of emigration has stabilised since 2014 to 19 thousand people per year. According to the OECD International Migration Database, the most popular emigration destinations have been the United Kingdom where 119 thousand Latvian emigrants resided in 2017, Germany, Ireland and Nordic countries. Emigrants are overall less skilled than permanent residents (Figure 3). Nevertheless, 20% of emigrants had higher education attainment in 2016, implying a sizable brain drain.

Figure 3. Emigrants are relatively less skilled

The composition of emigrants and permanent residents, 2016

While emigration intentions are generally stronger among less educated Latvians, many young people of all educational backgrounds express a desire to emigrate, mostly due to Latvia’s large earning gaps with high-income European economies (OECD, 2016b). Large emigration resulted in a sizable inflow of remittances, which amounts to more than 1 billion euros every year according to data from the Bank of Latvia, equivalent to roughly 4 ½ % of Latvia’s Gross National Income.

Like in other OECD countries, productivity growth has fallen after the global crisis of 2008/2009. Since then it has been mainly driven by resource reallocation to more productive firms. Yet, among Latvia’s large pool of small firms, many have experienced little or no productivity growth, pointing to weaknesses in their capacity to absorb new technologies and innovate. They need better management, access to skills and use of digital technologies, requiring investments in education and training, the quality of research and science-industry collaboration. Weak competition in some sectors with a high share of state-owned enterprises also holds back productivity growth. The government has been simplifying regulations and improving the functioning of the judiciary to ensure the protection of property rights and access to finance as well as facilitate innovation. These efforts need to continue.

Box 2. The new government’s key policy priorities

The new government of Latvia was established in January 2019, as a coalition of five centre-right parties. Its policy priorities with relevance to this Survey’s recommendations among others include the following:

Anti-money laundering

The government developed an action plan to strengthen the quality and capacity of supervision, control and law enforcement bodies regarding anti-money laundering and combating of terrorism financing, following the July 2018 mutual evaluation report by an international group of experts (Moneyval, 2018) and an OECD report (OECD, 2019a). The action plan will be implemented with the technical assistance of the OECD under the supervision of the Financial Sector Development Council, which is chaired by the Prime Minister and includes prosecutors, relevant ministers, representatives of the central bank, financial market regulators and other stakeholders. The 2019 budget foresees funds to increase the capacity of law enforcement agencies to combat money laundering through more hiring and training. The government is actively working to pass laws that will help to strengthen the authorities’ capacity to detect, investigate and prosecute money laundering activities.

Effectiveness of the judiciary

In order in enhance the capacity of the judiciary, large-scale training programmes for judicial staff are underway, funded by the European Social Fund.

Competition policy

The new government amended the competition law to endow the Competition Council with the authority to intervene when public administrative bodies favour enterprises that they control.

Social cohesion and skills

The government decided to ensure universal healthcare by abolishing the system that would exclude some residents from parts of healthcare basket. It is also elaborating proposals to increase social transfers to low-income individuals. A comprehensive Skills Strategy is being developed in collaboration with the OECD.

Administrative territorial reform

In line with the coalition agreement and a mandate from the parliament, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development set forward a proposal to merge municipalities.

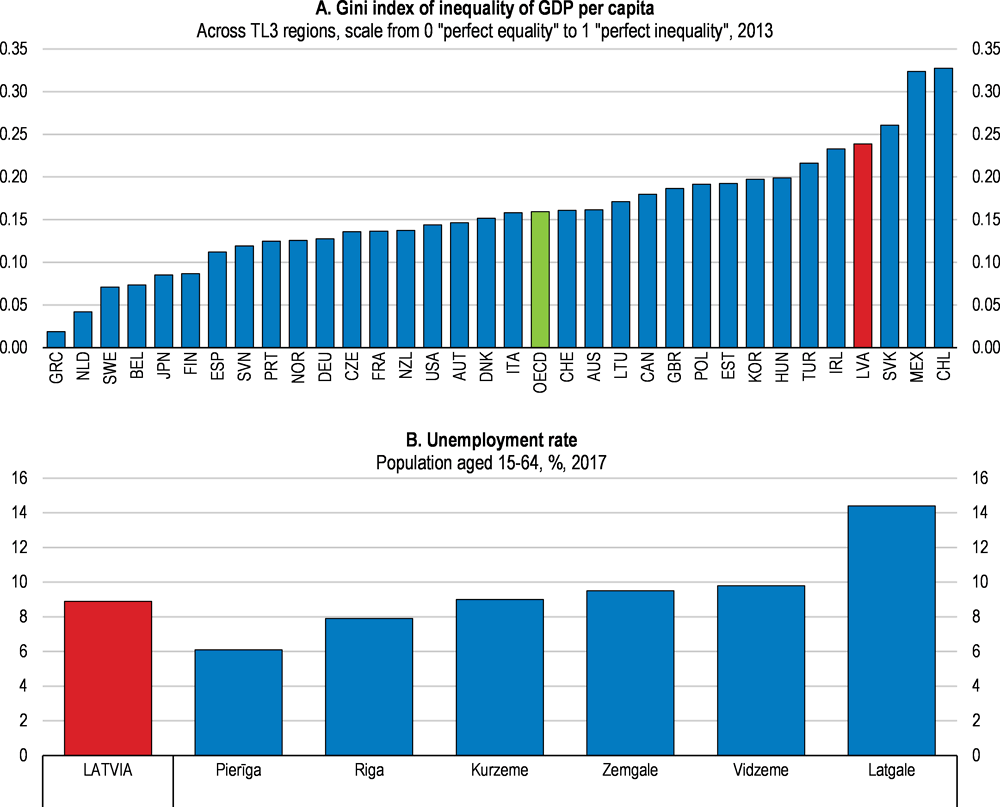

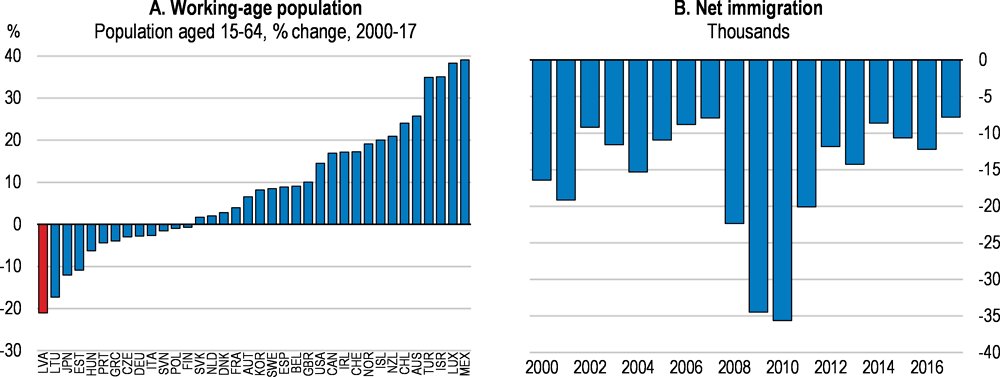

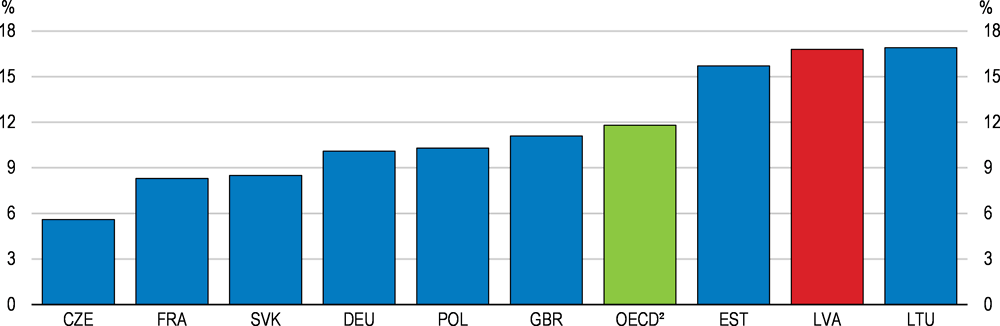

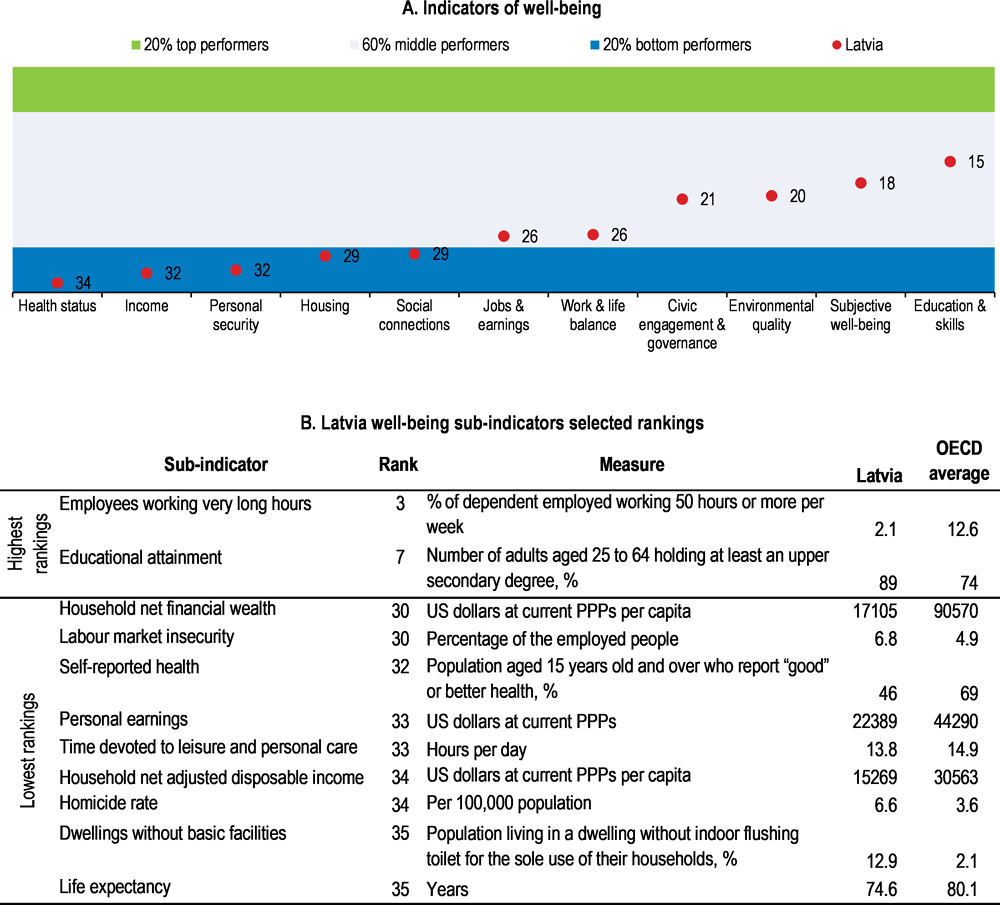

There are important inequalities in income, well-being and access to public services to address. Income inequality and poverty (Figure 4) remain high and many workers under-declare income limiting access to social protection, training and better career prospects. Job insecurity is high (Figure 5). Informality, including under-declaration of income and tax evasion, also weighs on productivity and tax revenues. Life expectancy and self-reported health are low and, in fact, highly unequal, with big gaps between men and women and different income groups. Housing conditions are poor for many people (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Poverty is high

Share of population with disposable income below the poverty line1, 2016 or latest year available

1. The poverty threshold is 50% of median household disposable income. Household income is adjusted to take into account household size.

2. Unweighted average of available countries.

Source: OECD Income Distribution database (IDD).

Figure 5. Latvia lags behind in some dimensions of well-being

Better Life Index, country rankings from 1 (best) to 35 (worst), 2017¹

1. Each well-being dimension is measured by one to four indicators from the OECD Better Life Index set.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Better Life Index, www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org.

Against this background, this Survey has four main messages:

Growth is strong and the macroeconomy appears balanced overall.

Investments in skills, research and innovation and efforts to strengthen competition would help support productivity and address the demographic challenges related to ageing and migration.

A more inclusive society requires more spending on health, social protection and housing.

Strengthening the judiciary and law enforcement agencies would help improve trust in institutions, address corruption, widespread under-declaration of income, or informality and tax evasion, and money laundering issues.

Reforms proposed in this Survey would have a positive impact on Latvia’s growth prospects, illustrated in Box 3.

Box 3. Structural reforms can raise growth and living standards

The effect of selected reforms proposed in this Survey can be gauged using simulations based on historical relationships between reforms and growth outcomes across OECD countries (Égert and Gal, 2017). The model on which the estimates are based captures the reform recommendations only very roughly in some instances. The policy changes that are assumed (Table 1) corresponds to scenarios where Latvia’s current policy settings converge to the average settings of OECD countries.

While reforms such as a reduction of personal income tax rates have implications for government finances, the model imposes a restriction that these reforms are budget neutral in order to leave the fiscal stance unchanged (see Gal and Theising, 2015). The fiscal measures laid out in Box 4 can be seen as one example how the reforms assessed in this box could be implemented in a budget neutral way.

Table 1. Illustrative GDP-per-capita impact of recommended reforms

|

Reform |

Percentage increase in GDP per capita |

|

|---|---|---|

|

10 year effect |

Long-run effect |

|

|

Increase spending on Active Labour Market Policy |

1.6% |

3.3% |

|

Increased spending on R&D |

0.9% |

2.4% |

|

Personal income tax reform |

0.7% |

0.9% |

|

Improve the rule of law |

1.9% |

5.0% |

|

Strengthening competition and enhancing privatisation |

1.8% |

4.8% |

Notes: The policy changes assumed for the simulations are:

1. Spending on active labour market policies as a share of GDP is increased by 0.24 percentage points to reach 75% of the level of the OECD average.

2. R&D business sector funding is increased by 0.6% of GDP, closing half of the gap to the OECD average level.

3. The tax wedge is reduced by 1 percentage point for single earners and 3 percentage points for one-earner couples with two children. This includes the reforms that the government has been phasing in since 2018 and further reductions in social contributions as laid out in Rastrigina (2019).

4. The rule of law measured by the World Bank’s World Governance indicator is improved by closing half of the gap with the OECD average

5. Privatising commercial activities of state-owned enterprises and strengthening the authority of the Competition Council is assumed to close the gap to the OECD average in the PMR - barriers to trade and investment index

Source: OECD calculations based on Égert and Gal (2017).

Macroeconomic policies are sound

The short-term economic outlook is strong

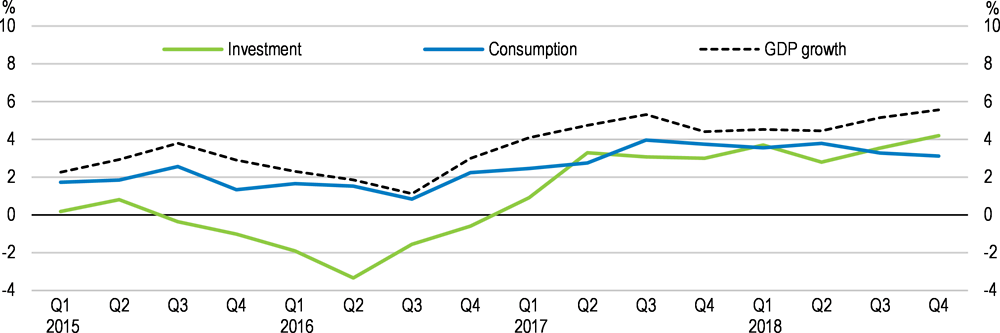

The economy is in a broad-based upswing (Figure 6), led by domestic demand. A strong labour market and fast increases in earnings are supporting private consumption. Following a slump, investment surged in late 2017 and 2018, as private and public investors learned the new rules to draw on EU Funds. A strong rebound of public and private investment pushed GDP growth rates above 4% in 2017 and 2018. Investment will continue to be supported by EU Funds, but its growth rates should moderate towards a more sustainable pace. GDP growth is expected to slow to around 3% in 2019 and 2020, as the cycle matures and world trade weakens. Growth in Europe will lose momentum, weighing on external demand and business expectations.

Figure 6. Investment and consumption contribute to GDP growth

Contributions to GDP growth

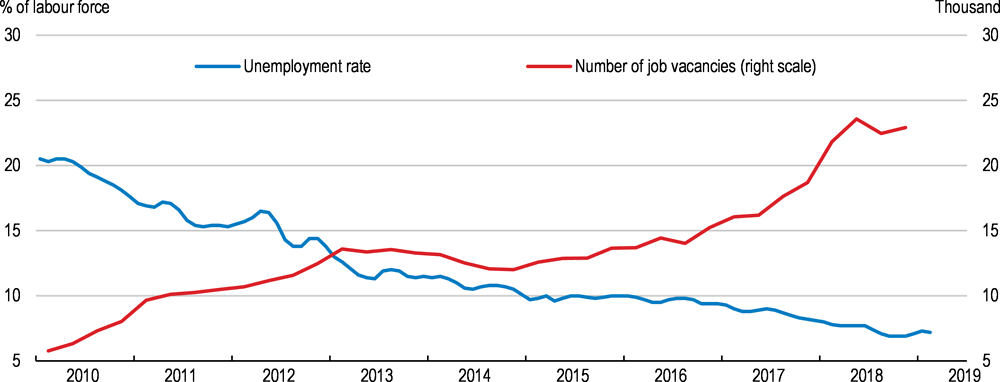

Unemployment has been decreasing fast and vacancies are continuing to grow (Figure 7), although a broader measure of unemployment that includes involuntary part-time and workers that are ready to work, but not actively seeking jobs for various reasons, is still above 14%. Vacancies are particularly high in the Riga region, Latvia’s main economic centre, and some other cities are suffering from labour shortages. Given a lack of affordable housing, workers find it difficult to relocate. Continued outmigration also contributes to skill mismatches and shortages. Along with a 13% rise in the minimum wage in 2018, this has fuelled wage growth, which is running at roughly 8%. While the effect of the rise in the minimum wage should fade over time, the wage growth is likely to remain high as skill mismatches and labour shortages will persist in the short run.

Figure 7. Unemployment is falling and vacancies are rising

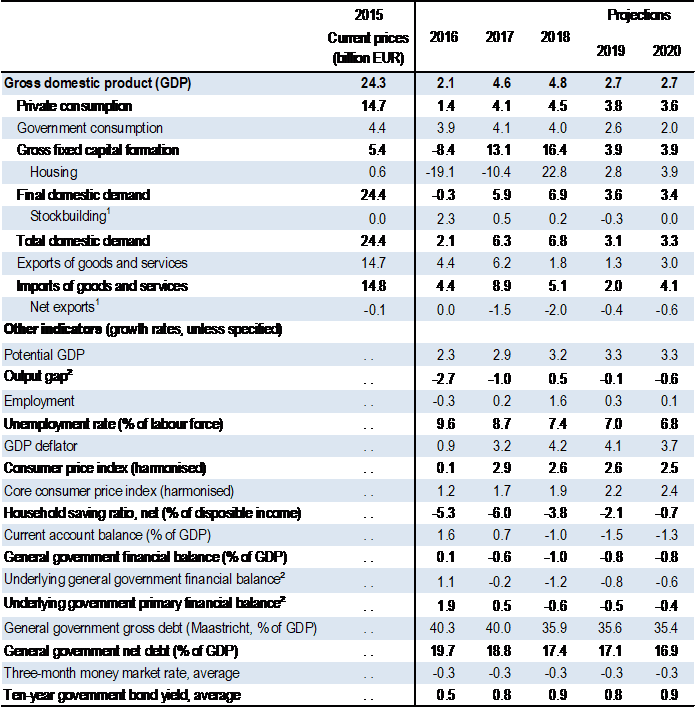

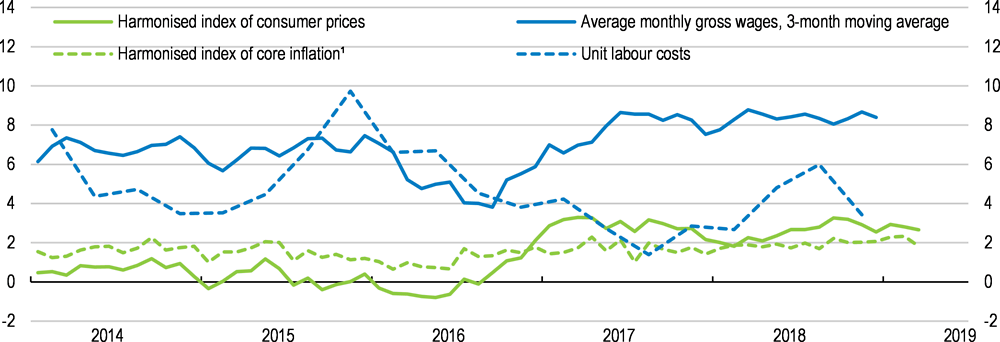

Although wage growth has surged considerably since 2016 (Figure 8), the effect on core inflation has been muted, so far. Increases in unit labour costs have been absorbed in firms’ profit margins. Credit growth to households and non-financial corporations is close to nil and while non-bank lending is growing faster, its share is too low to contribute to stronger demand. Higher excise taxes and sharp increases in energy prices contributed to a faster increase in headline inflation in 2018. As these effects are fading, inflation is expected to stabilise below 3%.

Table 2. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2010 prices)

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

2. As a percentage of potential GDP.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 105 database.

The fiscal deficit widened in 2018 as the government increased spending on healthcare by making use of the flexibility mechanisms within the EU fiscal rules. The government also started to phase in corporate and personal income tax reforms in 2018. The resulting decrease in fiscal revenue will be compensated by higher excise taxes and spending restraint in a number of areas. Higher social contributions are financing a part of the increase in health spending. The fiscal stance is projected to remain broadly neutral. This is appropriate given limited inflationary pressures and the need for more spending in particular on healthcare, education and training to address skills shortages and inequalities in access to social services. Yet, it may have to be tightened should inflationary pressures intensify more than expected.

Figure 8. Wage growth is strong, but inflation remains stable

Year-on-year % change

1. Harmonised index of consumer prices excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco.

Source: Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia; Economic Outlook Database; OECD Productivity Database.

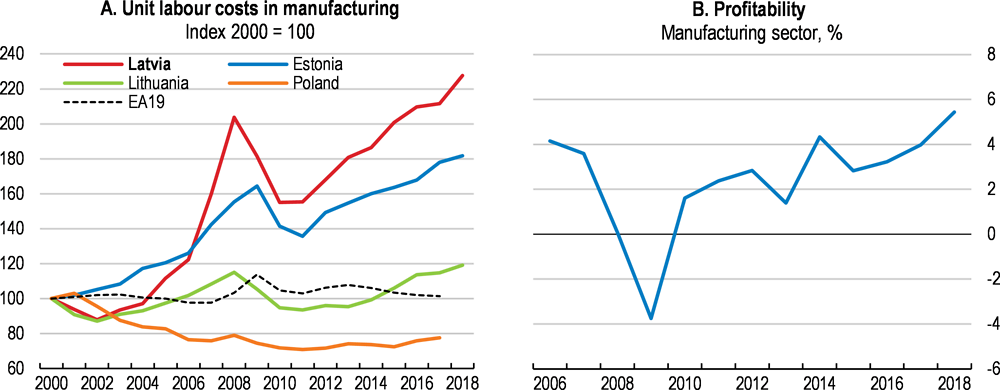

Despite strong wage growth, Latvian exporters have remained competitive and continued to gain market share. Unit labour costs have risen more than in neighbouring countries (Figure 9, Panel A). However, profitability continues to be high in manufacturing (Panel B), so there is room to absorb further wage increases in profit margins.

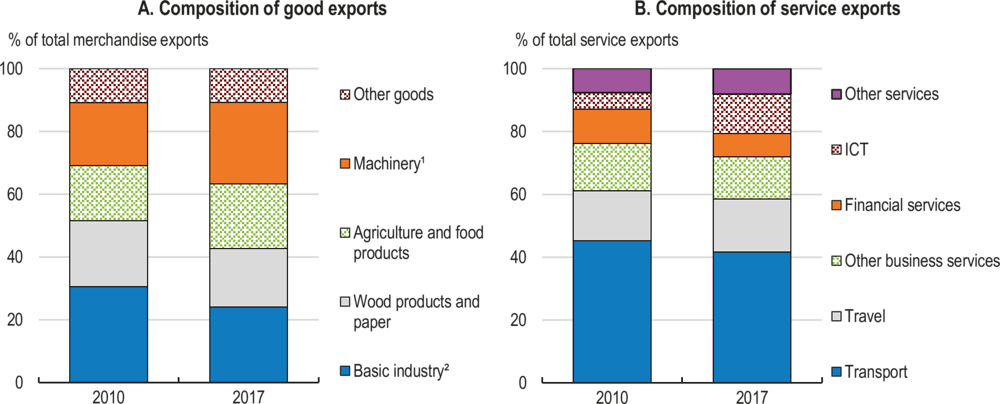

Figure 9. Unit labour costs are rising, but profitability remains strong

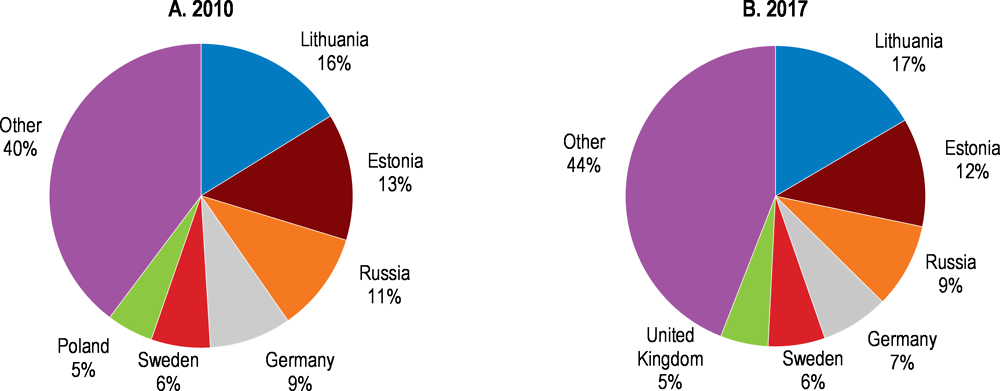

Latvia has diversified its exports and maintained strong performance despite headwinds from Russia (Figure 10). Services exports have been growing over the past decade, resisting adverse events in transport and the financial sector, as business services outsourcing, and in particular, ICT services, have been rising fast. Strong growth in tourism has compensated for a decline in transit traffic from Russia and in financial services of banks specialising in serving non-EU depositors following a tightening of anti-money laundering regulations. The share of agriculture, food products and raw materials in exports, although still large, has been falling, as higher-tech exports have fared well (Figure 11).

Figure 10. Latvia has diversified its trading partners

Exports of goods, shares by partner, % of total

Figure 11. Exports have become more sophisticated

1. Includes mechanical appliances; electrical equipment; transport vehicles; optical instruments and apparatus (inc. medical); clocks and watches; musical instruments.

2. Includes products of the chemical and allied industries; plastics and articles thereof; rubber and articles thereof; base metals and articles of base metals; and mineral products.

Source: Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia; Bank of Latvia.

There are both positive and negative risks to this outlook. The decision of the UK, an important trading partner (see Figure 10), to leave the European Union may affect exports, in particular if Brexit were to prove disorderly. Additional trade restrictions between the EU and the US would reduce external demand further. Wage growth has been well above productivity gains, and if it failed to moderate, costs would rise in the tradeable sector, hurting exports and encouraging imports. On the other hand, rising incomes and consumer confidence could strengthen consumption more than expected leading to a more sustained pick-up in domestic business confidence and investment. Continuing to improve re-training opportunities, internal labour mobility and social protection, will contribute to addressing labour shortages and strengthen the economy’s potential to grow faster in the longer term. Shocks, which would completely alter the economic outlook, include the intensification of geopolitical risks related to Russia (Table 3) and rising trade tensions between the United States and its main trading partners.

Table 3. Potential vulnerabilities of the Latvian economy

|

Vulnerability |

Possible outcome |

|---|---|

|

Intensification of geopolitical risks related to Russia. |

Geopolitical tension with Russia could jeopardise exports and investment. An immediate halt of the transit of Russian exports through Latvia would lower Latvian GDP by 3-4% according to estimates by the Bank of Latvia. |

|

Rising trade tensions between the US and China |

If the US were to impose tariffs on a much wider range of goods imported from China and China were to retaliate, this would jeopardize the EU’s and Latvia’s exports and investment. The Bank of Latvia estimates that EU GDP could be reduced by 1% after two years and Latvia’s GDP by more than that, if the US was to impose a tariff of 25% on goods that amount to roughly to 46.2 billion of imports from China (10% of the total) and China would retaliate with tariffs on a list of imported goods from the US with a total value of a similar size (49.8 billion US dollars or 38.2% of the total) (Bank of Latvia, 2018). |

|

A sharp reduction of EU funding of structural programmes in the next funding period starting form 2021. |

A deterioration in funding would severely hamper implementation of the government’s development strategies. |

Credit growth is low and the financial market is stable

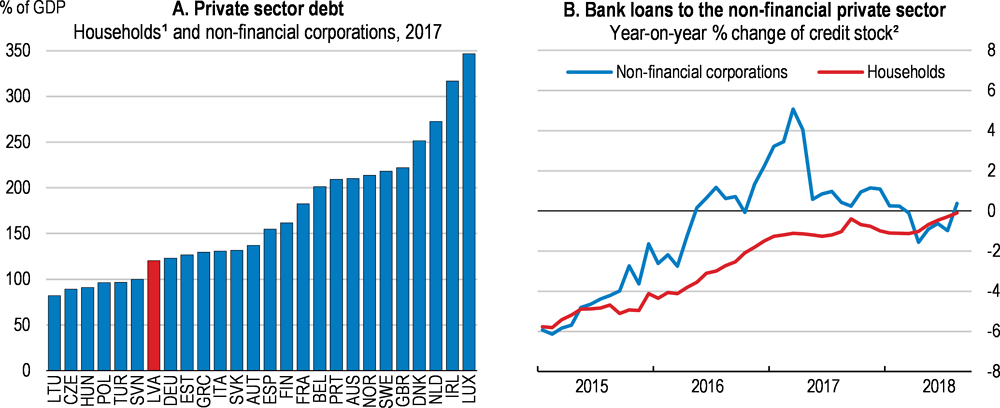

Credit growth remains subdued. The debt of private households and non-financial corporations has fallen from 180% of GDP in 2010 to 120%, below levels seen in most other European countries (Figure 12, panel A). While private sector debt reduction has lowered financial risks, weak credit growth is holding back stronger investment, weighing on Latvia’s development potential. Slow credit growth to business and private households (Panel B) partly reflects over-indebtedness of many lower-income households and difficulties of many firms and households to document their income because of widespread under-declaration.

Figure 12. Credit growth remains weak

1. Includes non-profit institutions serving households.

2. Data are adjusted for one-off effects related to the structural changes in the Latvian banking sector (e.g., due to withdrawal of credit institutions’ licences).

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database; OECD National Accounts Database; Bank of Latvia.

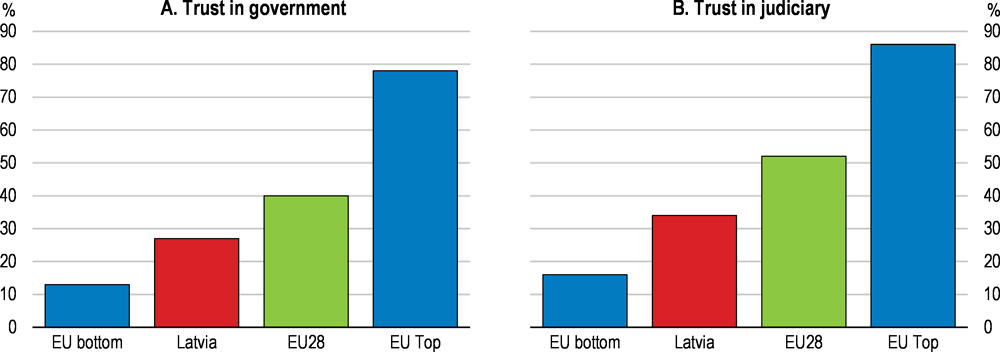

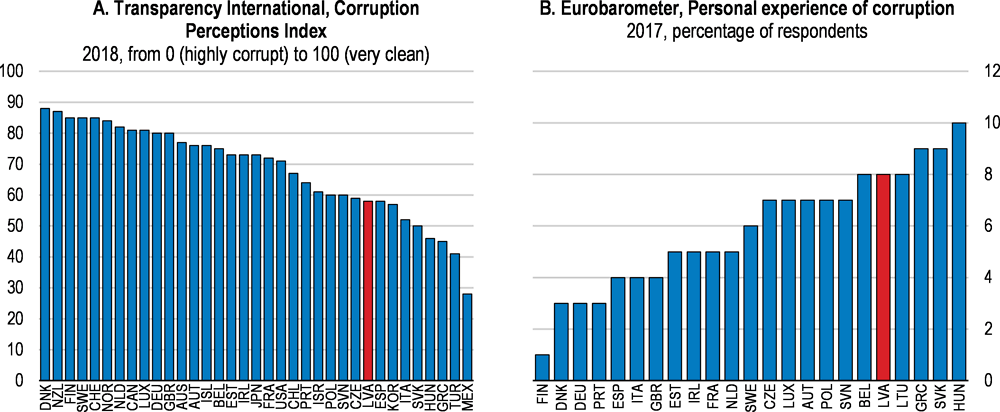

In the past, abuse of the insolvency regime in several cases and slow judicial procedures have also led to banks’ losses, increasing their perception of country-specific risk. A 2017 reform strengthened accountability and the qualification of insolvency administrators, but trust in the independence of the judiciary remains low among business, the public and judges themselves (European Commission, 2018a). High perceived corruption and low confidence in authorities’ capacity to fight it likely undermine investors’ trust (Figure 13). According to a Eurobarometer Survey, in 2017, only 18% of Latvian respondents declared there is enough successful prosecution to deter people from corrupt practices, the second lowest share in the EU (European Commission, 2017).

Figure 13. Corruption indicators

Note: “Eurobarometer: personal experience of corruption” refers to the share of respondents who answered positively to the question “In the last 12 months have you experienced or witnessed any case of corruption?”.

Source: Transparency International; European Commission, Special Eurobarometer 470.

Measures to strengthen the independence of the justice system and to improve effectiveness of the insolvency framework have been put in place, but are too recent to evaluate their effectiveness. The credibility and effectiveness of the judiciary can be reinforced by improving investigations of disciplinary offences committed by judicial staff (CEPEJ, 2018). The transparency and consistency of investigations could be improved by establishing a judicial inspectorate that is common in many OECD European countries. Time limitations for initiating disciplinary procedures and for imposing a sanction should also be lengthened in light of international best practices.

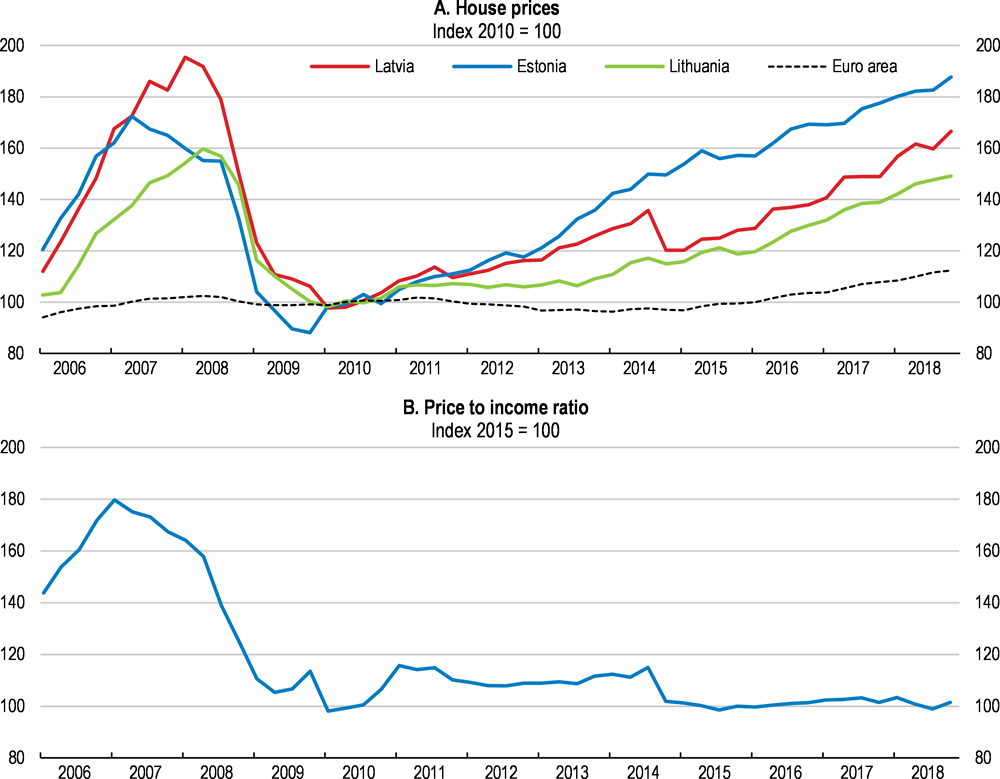

Financial soundness indicators of banks are strong overall. The tier 1 capital ratio stood at close to 20% at the end of 2018, above levels seen in most other EU countries. The leverage ratio was also high at close to 10%, well above the 3% required by Basel III standards. Stress tests seem to suggest a high ability to withstand shocks of Latvian banks that specialise in serving domestic customers. The share of non-performing loans has also fallen significantly and is now close to the EU average of 5%. House prices have been rising faster than in most European countries, but increases have been in line with income growth and prices remain well below their peak in 2008 (Figure 14). Lending standards have eased with an increase of the share of new mortgage credit with a loan-to-value ratio above 80%. Since household debt continues to decline, risks from excessive lending to households appear limited.

Figure 14. House prices are rising in line with income growth

Note: The price-to-income ratio is given by the ratio of nominal house prices to nominal household disposable income per capita.

Source: Eurostat; OECD Housing prices Database.

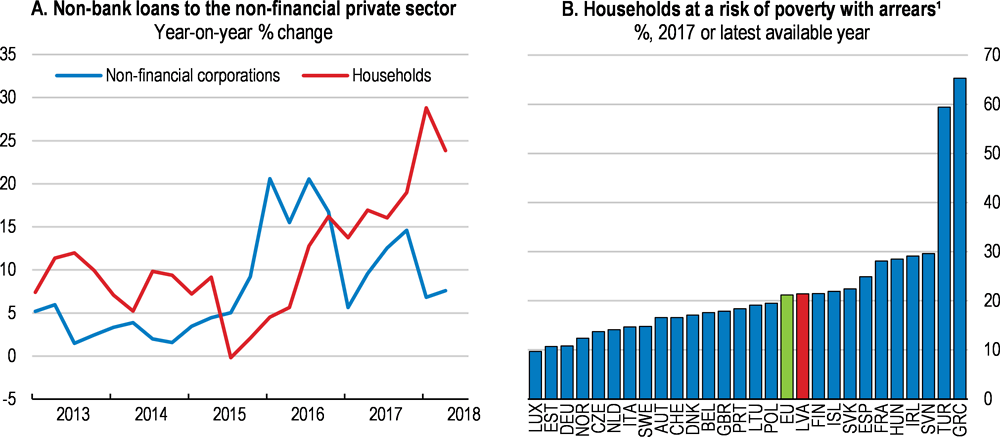

Lending from the non-bank financial sector rises rapidly, although from a low level, including expensive consumer credit and pay-day loans to households. Non-bank loans accounted for 40% of household’s interest expenses at end-2017, although the stock of outstanding loans from the non-bank sector stood at around 20% of the total bank loans portfolio. The share of households at risk of poverty who are in arrears is above the EU average (Figure 15). According to the ECB’s Household Finance and Consumption Survey the 10% most heavily indebted households in Latvia have to devote more than half of their income to pay down their debt, higher even than in Greece and more than twice as high as in Finland and Poland.

Since January 2019, both bank and non-bank lenders have to assess clients’ creditworthiness using information on their overall loan portfolios, including non-bank loans, available through licensed credit bureaus. Total costs, including interest, for pay-day loans will also be capped from July 2019. Higher fines for lending to households who cannot afford it, currently capped at 43 000 euros, may be necessary for effective enforcement. Rolling out municipality-led counselling for debtors throughout the country would be useful, as it is not available everywhere in the country and it is not free of charge, unlike for example in Germany. The cost of initiating private insolvency procedures of approximately 900 Euros is out of reach for many low-income households and should be waived for the poorest.

Figure 15. Non-bank loans are rising fast, as many households have problems re-paying debt

1. Households below 60% of median equalised income having arrears on mortgage or rent payments, utility bills, hire purchase instalments or other loan payments.

Source: Bank of Latvia; Eurostat.

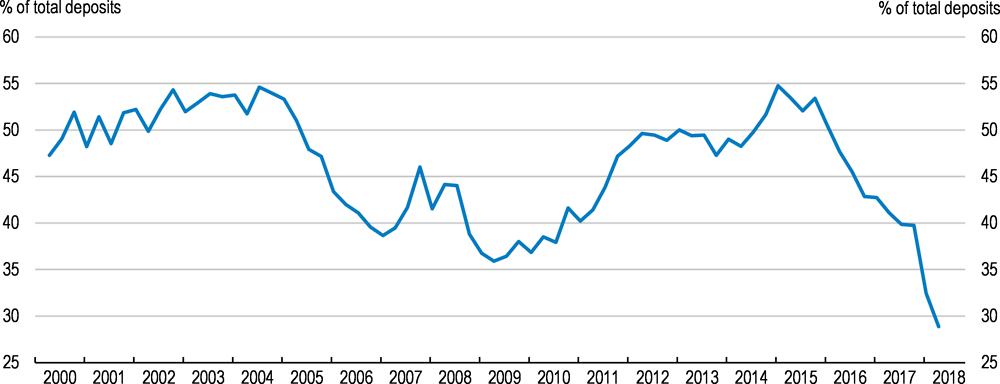

There are challenges in relation with the unwinding of the large share of foreign deposits following money laundering allegations. The related downfall of ABLV, Latvia’s then third-largest bank, in the summer of 2018 highlighted the need for further action. Since then Latvia banned its banks from servicing certain types of high risk “shell companies” and oversaw a reduction in non-resident deposits by more than 60 % following a tightening of anti-money laundering and combating of terrorism financing (AML/CFT) framework in 2016 and 2018 (Figure 16). A number of banks in Latvia have specialised in serving foreign clients, whose funds originate mainly from the Commonwealth of Independent States. Foreign deposits have fallen quickly. So far, Latvian banks serving mainly foreign customers have managed to maintain high levels of capitalisation and liquidity, but the future of these banks depends on their ability to change their business model. Linkages of banks serving foreign clients to the domestic lending market and banks serving domestic clients are limited and so are risks for repercussions on overall financial stability. Strengthening AML supervision would require increasing resources dedicated to inspections in the foreign deposit banking sector (Moneyval, 2018; OECD, 2019a). The authorities have initiated an overhaul of the anti-money laundering system to ensure the highest standards of supervision, regulation and transparency (see Box 2), which should be presented in spring 2019, a welcome step.

Figure 16. The share of foreign deposits in the Latvian banking sector is falling

Tax and spending reform for a stronger and more inclusive economy

The budgetary framework is sound

Latvia has a rigorous budgetary framework with an independent fiscal council and transparent national fiscal rules and medium-term budgetary planning designed to ensure compliance with the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact. Overall, the fiscal position is sound with a low debt and deficit. Spending efficiency is high (IMF, 2018).

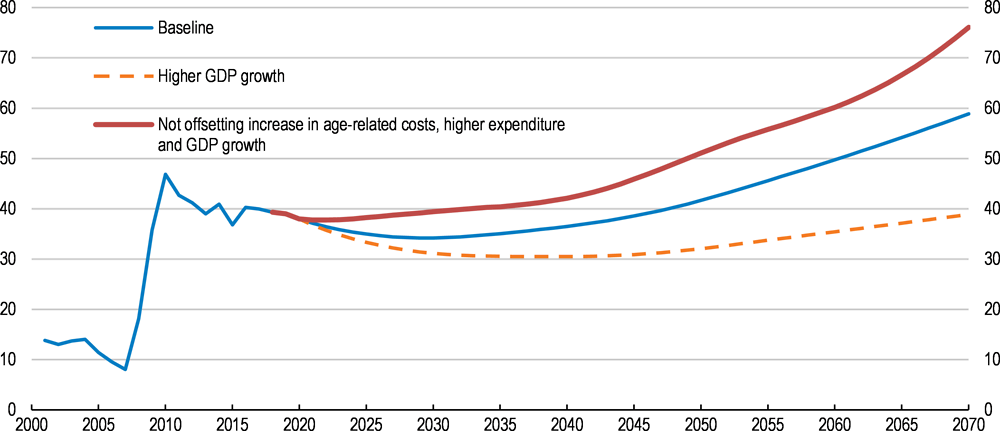

Despite a fast increase in the old-age dependency ratio, ageing-related spending is not forecast to increase over the coming decades. Public pension expenditure automatically adjusts downwards when the working-age population falls, the importance of the private pre-funded pillar is rising and pension indexation falls short of wage growth (European Commission, 2018b). Sustainability concerns are limited from today’s perspective if the current system is maintained (Figure 17), but reducing old age poverty from its current high level and maintaining replacement rates would require additional spending on public pensions.

Another challenge will be to prepare for a possible fall in available EU structural funds in the next financing period. Latvia is one of the largest recipients of EU funds relative to its GDP. The successful absorption of EU funds has boosted employment and investment over the past years (Benkovskis et al., 2018). Latvia relies heavily on the EU budget to finance public investment and policies support to innovation and skills development. This has created problems with policy continuity during the switchover of EU Fund Programming Periods, as financing of some very effective programmes was interrupted. As it is unclear how the availability of these funds will develop in the next Programming Period, it will be important to identify the most effective EU funded policy measures through evaluations and plan for national financing of these measures.

Increasing debt after 2045 due to a slowdown in growth, as in the baseline scenario (blue line), could be prevented by strengthening productivity growth through structural reforms proposed in this Survey (orange line). In that case, debt would stay below 80% of GDP until 2070 even if the government were not to offset ageing-related spending increases through higher taxes. It could even add a further percentage point of GDP to pension and healthcare spending to improve adequacy without higher taxes (red line). Offsetting these spending increases through mildly higher taxes would keep debt constant.

Figure 17. Illustrative public debt paths

General government debt, Maastricht definition, as a percentage of GDP

Note: The baseline scenario assumes a constant primary deficit of 0.3% of GDP, inflation of around 2% and annual real GDP growth slowly decreasing from around 2% in the 2020s to around 1% in the 2050s, in line with assumed convergence of productivity growth with the European Union average (Guillemette and Turner, 2018). The age-related cost assumptions in the “Not offsetting increase in age-related costs, higher expenditure and GDP growth” scenario assumes public spending and GDP growth are 1 percentage point higher than in the baseline scenario. The ‘Higher GDP growth’ scenario assumes that real GDP growth is 1 percentage point higher than in the baseline.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), November; Guillemette, Y. and D. Turner (2018), “The Long View: Scenarios for the World Economy to 2060”, OECD Economic Policy Paper No. 22., OECD Publishing, Paris; and European Commission (2018), “The 2018 Ageing Report – Economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)” Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.

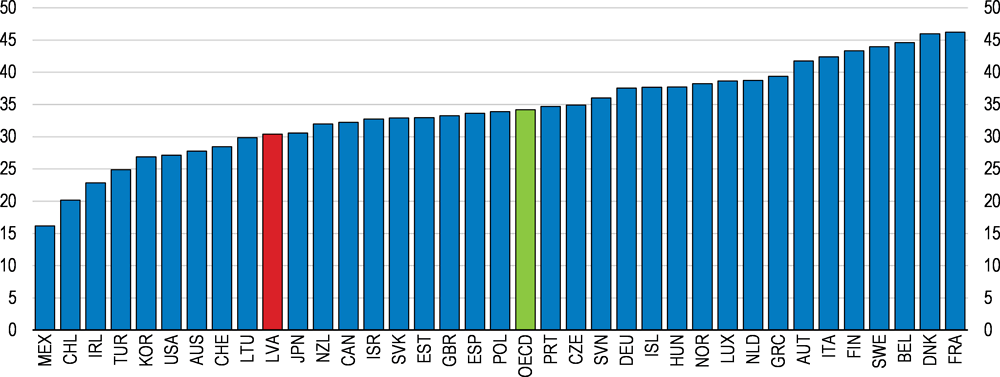

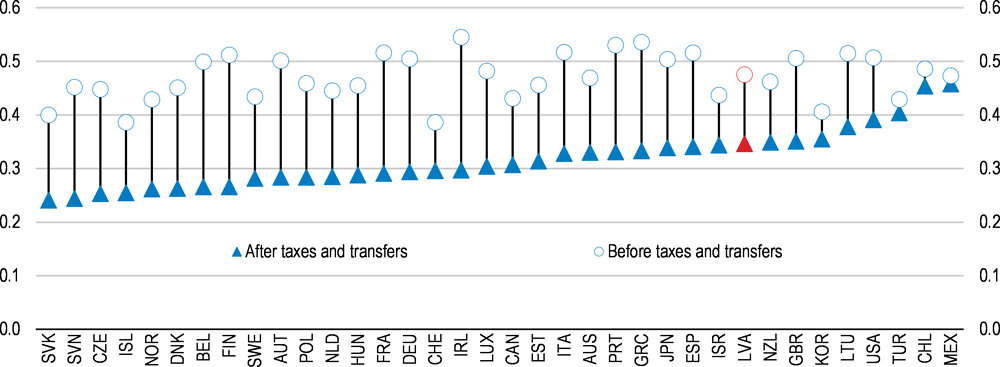

Making taxing and spending more inclusive

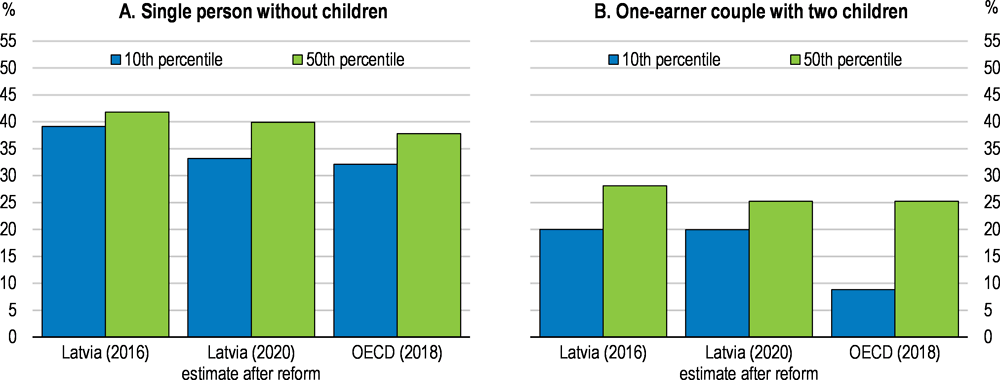

Tax revenues as a share of GDP are well below the OECD average (Figure 18). Overall, tax and benefits could have a larger impact on poverty and equity (Figure 19). This is because the size of social transfers and the progressivity of personal income taxation are limited. The personal income tax schedule is essentially flat and effective tax rates on labour for low-income earners are relatively high (Figure 20). The guaranteed minimum income, or social assistance, provides single households with 10% of the median household income in Latvia, compared with an EU average of 25%. It hardly covers costs for a healthy diet in the Riga region, let alone other basic necessities (European Commission, 2018c).

A 2018 reform made personal income taxes somewhat more progressive and lowered the tax burden on labour income. It increased the income-dependent tax allowance, particularly for lower-income workers, and introduced a progressive tax schedule. Nevertheless, in practice a 20% rate is applied to more than 90% of taxpayers (Pluta and Zasova, 2017). In addition, this measure does not help the lowest income earners who do not pay income tax. There is thus room to strengthen the redistributive impact of the tax system further. In the longer run, tax cuts better targeted on low-income households and effective increases in personal income tax rates on medium to high incomes would bring more progressivity in the system.

Figure 18. Tax revenues are relatively low as a share of GDP

General government, tax revenues, % of GDP, 2017 or latest available year

Figure 19. The tax-and-benefit system could do more to lower high inequality

Gini coefficient, scale from 0 “perfect equality” to 1 “perfect inequality”, 2016 or latest available year

The government introduced a new social contribution of 1% of payroll to finance higher health spending. As a result, the effective tax rates on labour will not decrease for some low-income households (Figure 20, Panel B), remaining well above the OECD average, although the tax burden will fall for lower- and middle-income households, who benefit more from the reduction of the tax allowance. Financing higher healthcare spending from general budget revenues rather than earmarked social contributions would improve labour market outcomes and equity while simplifying the tax system. Reducing the tax burden on labour income has led to higher formal employment in Colombia (Kugler et al., 2017) and in Turkey (Betcherman et al., 2010). Informality in those countries is higher than in Latvia, but still these research suggest that increasing social security contributions risks being counterproductive.

Figure 20. Taxation of labour income will decrease for some households

Effective tax rates on labour at different earnings levels, % of labour costs

Source: Rastrigina, O. (2019), “Reform Options to Reduce the Effective Tax Rate on Labour in Latvia”, Technical Background Paper for the OECD Economic Survey: Latvia 2019. ECO/EDR(2019)10/ANN3.

There have been plans to increase the guaranteed minimum income, or social assistance, for some time, but implementation remains incomplete. Benefits were increased substantially only for pensioners and families with children. Since 2017, earnings up to the minimum wage are exempted from the benefit means-test for three months after starting a job. But afterwards, the social assistance benefits are withdrawn one-for-one when income rises, thus implying a 100% marginal effective tax rate, entailing considerable negative work incentives. In fact, for a single-earner family with two children, there is almost no financial gain from taking up a minimum-wage job, creating an inactivity trap (European Commission, 2018c).

The three-month earnings disregard may prove insufficient to strengthen work incentives durably. Withdrawing the benefit more gradually as income rises, for instance by offering permanent income disregard as done in Lithuania and Finland, would be a useful follow-up reform. Simulations show that increasing the guaranteed minimum income to bring it to 40% of the median income (and 20% for work-able recipients), while tapering it off more gradually, would come at a substantial budget cost of around 1% of GDP. At the same time, it would reduce poverty by almost 9 percentage points (European Commission, 2018c).

Since a recent reform, taxes on capital income are aligned at a 20% rate and the taxation of corporate income is deferred until the distribution of profits. The nominal tax rate on corporate profits and dividends of 23.5 % has been lowered, while the rates on interest and capital gains have been increased from 10 % and 15 % to 20% from 2018. Aligning tax rates on different forms of capital income reduces distortions and is thus welcome. No corporate tax is payable on undistributed profits, mimicking an earlier reform in Estonia. Authorities are hoping that this will entice more companies to fully declare their profits, improving access to credit. There is evidence that companies in Estonia reacted mainly by accumulating liquid assets (Hazak, 2009) and studies struggle to find positive effects on investment or productivity (Pikkanen and Vaino, 2018; Staehr, 2014). The government should carefully evaluate the impact of the reform on tax revenues, incentives for businesses to incorporate, formality, investment and firm performance to assess whether such a costly reform yields the expected benefits.

Indirect tax revenues are set to increase with rising excise duties (Table 4). Measures to improve value added tax (VAT) compliance, such as lowering the threshold for VAT registration and stricter requirements to report VAT transactions in more detail, are expected to increase revenues (European Commission, 2018a). The shortfall of VAT revenues compared with its potential has been falling, but remains substantial at 12.9 % of potential revenues according to data from the tax authorities, suggesting significant room to further improve compliance.

Table 4. Past OECD recommendations on taxation and spending

|

Topic and summary of recommendations |

Summary of action taken since 2017 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Reduce the labour tax wedge on low earnings |

An increase in the income-dependent tax allowance reduces the tax wedge on some workers. |

|

Raise more taxes from the taxation of real estate and energy |

Excise taxes on fuel, alcohol, tobacco and gambling were increased in 2018. Annual vehicle taxation will be based on CO2 emissions for cars that are registered after 2008, but for older cars taxation will still be based on gross weight or gross weight, engine capacity and engine power. Moreover, there will be tax reliefs for agriculture and large families and exemptions for handicapped persons. |

|

Gradually withdraw benefits targeted at low-income earners when they take up a job |

The guaranteed minimum income can now be retained for three months after finding a job. |

Property tax revenues are almost a full percentage point of GDP lower than on average in OECD countries. Increasing property tax rates would help generate revenues to lower labour taxes and increase social spending. It would also be progressive because property wealth is highly concentrated in Latvia (Household Finance and Consumption Survey, 2017). That said, sufficiently high tax allowances or exemptions for lower-income households are already in place. The re-assessment of cadastral values is ongoing and should allow aligning the tax base with market values, as done in the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden. This would increase economic efficiency and equity. The tax and spending reforms proposed throughout the Survey would have a budgetary impact, which is illustrated in Box 4.

Box 4. Quantifying the fiscal impact of structural reforms

The following estimates (Table 5) roughly quantify the long-run fiscal impact of selected recommendations. These estimates do not take into account any consequent effects on GDP. Since the assessment of the reform impact of recommendations on GDP in Box 3 is estimated in a budget neutral way, it already incorporates any negative effect of GDP of tax increases described in this box. The fiscal estimates below do not take into account any consequent effects of reforms on GDP and hence fiscal revenues, because these seem too uncertain.

Table 5. Illustrative fiscal impact of recommended reforms

|

Measure |

Annual fiscal balance effect |

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

% of GDP |

|

|

Deficit-increasing measures |

1.5 |

|

|

|

Increase the guaranteed minimum income and taper its withdrawal |

0.5 |

|

|

Increase investment in ALMP |

0.2 |

|

Increase spending on healthcare |

0.5 |

|

|

|

Provide more public funding for affordable rental and social housing |

0.1 |

|

|

Improve wages and conditions for researchers and provide incentives to collaborate with industry |

0.1 |

|

Strengthen the capacity of enforcement personnel |

0.1 |

|

|

Offsetting tax measures |

1.5 |

|

|

Labour tax reform |

0.3 |

|

|

|

Energy tax reform |

0.5 |

|

|

Property tax increase |

0.8 |

Notes: The policy changes assumed for the estimation are the following:

1. The guaranteed minimum income is increased to 20% of the median income with a tapering of the withdrawal, a variant of the calculation in EC (2018c).

2. Spending on active labour market policies as a share of GDP is increased by 0.24 percentage points to reach 75% of the level of the OECD average

3. Increasing spending on public funding for affordable housing as a share of GDP to 50% of the OECD average

4. The personal income tax reform assumed for this calculation includes abolishing the social contribution earmarked for healthcare financing, reducing social security contribution on low incomes, and increasing progressivity of the personal income tax as described in Rastrigina (2019).

5. Changes in the energy tax regime consists in harmonising the tax rate for diesel, oil products and gasoline.

6. Property tax as a share to GDP is increased to the average level in the OECD.

Source: OECD calculations.

Improving fiscal equalisation and the quality of local public services

All municipalities need sufficient financing to provide their citizens with high quality public services, including education and training, and promote social mobility. Local governments rely on earmarked central government grants and personal income and real estate taxes. Local government spending accounts for approximately 28% of the total and includes school provision, housing, social transfers, local infrastructure and economic development.

Regional disparities in income per capita are unusually pronounced in Latvia, and so are differences in unemployment (Figure 21). As a result, per capita tax revenues differ markedly across municipalities and are three times higher in Riga than in some rural municipalities. A much larger share of the population in poorer municipalities typically receives social transfers, further limiting financial resources for infrastructure and education spending.

Figure 21. Regional disparities are large

Fiscal equalisation was reformed in 2016 and it does reduce revenue inequalities quite effectively, although post-equalisation inequality is still at the high end compared to other countries with a similar structure (Table 6). To make up for municipalities’ losses resulting from the tax reform a new central government grant was introduced in 2016, which is linked to municipal personal income tax revenues, thus reinforcing inequalities. Linking central government grants instead to the costs of service provision would help improve the capacity of poorer municipalities to invest in education and training and key municipal infrastructure.

Table 6. The strength of equalisation in OECD countries

|

Unitary countries |

Ratio of highest to lowest tax-raising capacity decile, 2012 |

Ratio of highest to 6th tax-raising capacity decile, 2012 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Before equalisation |

After equalisation |

Before equalisation |

After equalisation |

|

Latvia (2017) |

2.9 |

1.4 |

2.0 |

1.3 |

|

Denmark |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

|

Finland |

1.8 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

|

Norway |

2.1 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

1.2 |

|

Sweden |

1.5 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

|

Average |

1.9 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.2 |

Source: OECD calculations

Latvia has a two-tier government structure comprising the central state and municipalities. A 2009 reform reduced the number of local governments from over 500 to 119, but the average size of municipalities is still much smaller than in other countries where municipalities play an important role in education provision, such as Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands (Figure 22).

The creation of groups of municipalities that could manage some tasks at the group level has been envisaged in 2018. This was a good starting point to improve the efficiency of local public service provision, in particular by easing consolidation of the school network and coordination of urban and transport planning. Merging small municipalities would free up more resources, but is politically difficult. It is thus welcome that the new government recently initiated an ambitious territorial reform to revise the administrative map and create larger municipalities before the next municipal elections in 2021.

Figure 22. The average size of municipalities is small

Average number of inhabitants per municipality, 2016

Addressing skill shortages

Providing high-quality education to all

Given growing skills shortages and the rapid decline in the working age population, the education system needs to equip all children with solid cognitive skills. PISA results are above the OECD average in Latvia, but the urban-rural divide is sharp, well above the OECD average (Echazarra and Radinger, 2019). High-quality early childhood education can improve learning outcomes throughout life. In fact, lower PISA results in rural areas may partly reflect a large attendance gap in early childhood education between urban and rural areas at the time when today’s teenagers were pre-schoolers (Echazarra and Radinger, 2019). Since then the government has invested heavily in early childhood education and the attendance gap has narrowed. Reaching out to parents in rural areas to ensure full attendance to early childhood education while improving the monitoring of early childhood services would be useful.

Highly qualified and motivated teachers are key to improving students’ skills (Chetty et al., 2014; OECD, 2013). Yet, due to low wages, limited career options and low prestige, teaching is not considered as attractive in Latvia (OECD, 2016a; OECD, 2018a). The teaching workforce is ageing fast and raising teacher salaries and developing interesting career options should be a priority to attract competent new recruits, in particular in rural schools with struggling children. Latvia could look to Australia, Estonia, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Singapore, which have developed human resource models to attract teachers. The teacher workforce would also benefit from investment in more systematic and continuous personal development, as required training hours for teachers are low and there is a lack of induction programmes (OECD, 2016a).

Urban-rural inequalities in educational outcomes can be partly traced to the fact that a disproportionate share of resources is used for the maintenance of a fragmented school network rather than for teaching and learning. Many schools are too small to be viable and some smaller and poorer municipalities lack the capacity to effectively manage their local education systems. In addition, municipalities can top up state-financing for schools, resulting in a large variation of per-pupil spending and teacher salaries across municipalities. The ongoing consolidation of the school network could be accentuated to achieve economies of scale. Resulting savings could be used to offer higher salaries, better career prospects and continuing training options.

A recent reform foresees diminishing the scope of non-Latvian language teaching in general secondary education by the 2020/2021 school year. Currently, 27% of students study up to 40% of lesson hours in another language, primarily in Russian, but also other languages, such as Polish and Estonian. The reform aims at ensuring all pupils have high proficiency in Latvian, not least to facilitate their integration in the labour market. The authorities plan to provide teacher training, teaching aid and material to achieve this objective in the envisaged timeframe while preserving educational outcomes of pupils. The authorities should ensure that all schools receive sufficient resources and monitor outcomes closely, as switching the language of instruction risks being challenging for some teachers.

Providing adequate skills

Addressing skill shortages requires making education more responsive to quickly changing labour market needs. In vocational education, the government made important progress in this respect by involving social partners in updating curricula through Sectoral Expert Councils. The government is working to expand work-based learning, but while student numbers are increasing, they remain low and tend to concentrate in sectors such as hotel and restaurant services and beauty services (Ministry of Education and Science, 2019). Latvia’s numerous small and medium enterprises often shy away from offering workplace training due to the logistical difficulties of setting it up. Promoting joint work-based learning as in Germany or Austria can be helpful. Similarly, stronger reach-out mechanisms for small firms, for example intermediary bodies that handle the logistics of work-based learning for them, such as placing students in firms and engaging with schools to ensure that they address their needs, have helped to place more students in enterprises in Australia and Scotland.

The government has made considerable efforts to invest in adult learning and participation has increased fast, albeit from a low level. As in other OECD countries, participation is much lower for older and low-skilled workers and addressing this requires providing more information about the programmes on offer and good counselling. Financial support for firms, perhaps focussed on training for low-qualified workers as in Germany, or scholarships for workers with limited means who wish to engage in training would be helpful.

Spending on active labour market policies has been low. There has been a welcome re-focussing from public works to more training measures and activation for the long-term unemployed, as such programmes have a better impact on employment (OECD, 2019b). Participation in activation measures for the long-term unemployed more than doubled in 2017. Caseloads can be high, varying between 350 and 500 cases per months in 2017. Hiring more counsellors can be effective in intensifying counselling and reducing unemployment spells, as experience in Germany and the Netherlands has shown (Hainmüller et al., 2016; Koning, 2009).

Making Latvia more attractive for foreign and domestic workers alike

Making Latvia more attractive for foreign and domestic workers alike will also be important to address skill shortages. Emigration intentions are particularly strong among students and younger workers (Hazans, 2015). Most emigrants and people considering emigration cite financial concerns and a desire to improve their material living conditions as reasons for their decision (OECD, 2016b), but limited social protection also features high on the list (Hazans, 2015). Promoting economic development and improving access to social protection and services are thus important to make Latvia more attractive for domestic and foreign workers.

While the inflow of the foreign-born population has increased, this surge has been much stronger in nearby Estonia and Poland. Both countries receive many workers from Ukraine and Belarus owing to simplified procedures to hire workers from those countries and fast-track access to residence permits for skilled migrants from non-EU countries. In Latvia, the law imposes Latvian only in almost all official contexts and strict Latvian proficiency requirements for a wide range of professions. This can be a hindrance to skilled migration, including for the return of Latvian emigrants with foreign-born partners or children, even though programmes to learn Latvian are widely available (OECD, 2016b). The government recently eased procedures for immigration of skilled workers in some professions with shortages (Table 7), but they are not covered by public health insurance. Foreign graduates are not exempted from labour market tests.

Expecting large waves of return migration would be unrealistic, as only a fifth of emigrants indicate plans to return within the next five years. Still strong engagement with the diaspora can alert emigrants to opportunities to invest, do business or help promote Latvia as a destination for investment and tourism. The government runs information campaigns in countries with a high concentration of Latvian emigrants and offers help with finding housing, work and business opportunities in Latvia. It is also setting up a database of Latvian researchers abroad and their interest in research and teaching collaboration with Latvian institutions is substantial.

Table 7. Past OECD recommendations on education and labour market policies

|

Topic and summary of recommendations |

Summary of action taken since 2017 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Provide more generous grants for students attending vocational schools who are from low-income families |

There is a programme financed from EU Funds that provides financial help and counselling for students at risk of early school leaving. |

|

Expand grants for university students and target them to students from low-income families |

The government plans to provide social grants to studying parents. |

|

Accelerate the development of modular programmes in VET, professional qualification exams and professional standards |

The development of modular programmes, professional qualification exams and professional standards is ongoing. |

|

Promote the provision of adult education in VET schools |

Pilot programmes train staff in vocational education schools to develop adult education programmes. |

|

Reduce labour market test and language requirements for highly skilled immigrants |

For a list of professions with skill shortages the labour market test has been eased, as the vacancy has to be registered with the public employment service only for ten days as opposed to 30 days before a foreigner can apply. Authorities’ deadline for processing the application for an EU Blue Card for these professions has been shortened from 30 to 10 days and applicants now only need to proof that they have five years of work experience in the field rather than provide an education certificate. Their wage needs to be only 20% above the national average as opposed to 50% before. |

|

Support the employment of foreign students by shortening the process for obtaining work visa and labour market tests |

The residence permits for foreign students is issued for a term exceeds the required study period that for 4 months. After this period a student is entitled to apply for a job-searching permit for 9 months. |

Fighting informality to improve productivity and access to social services

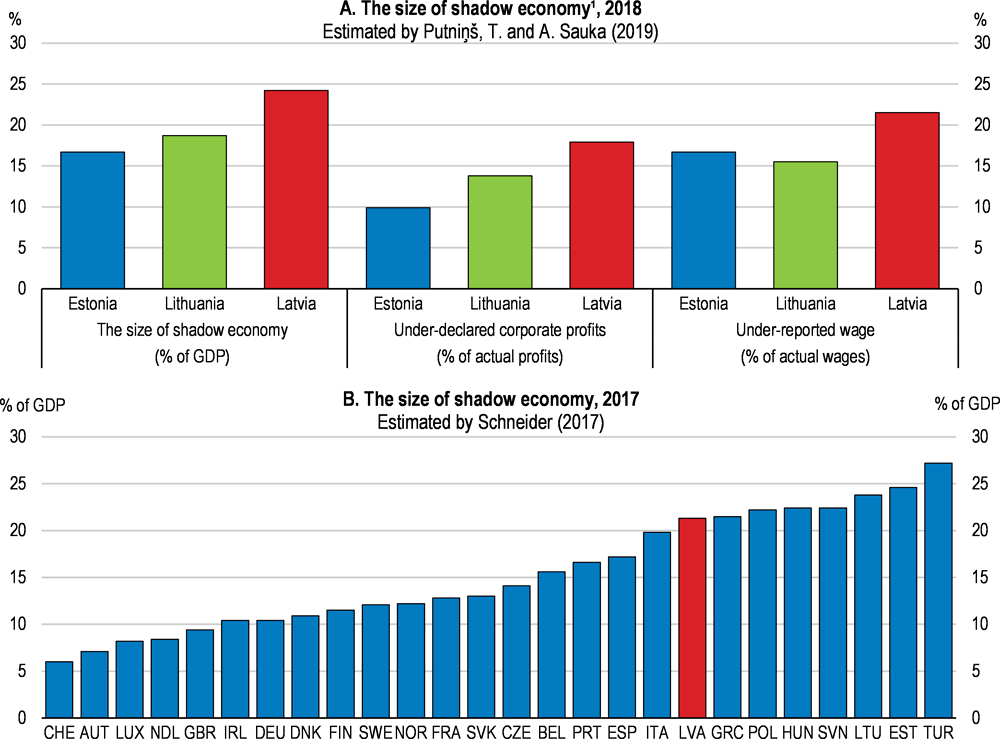

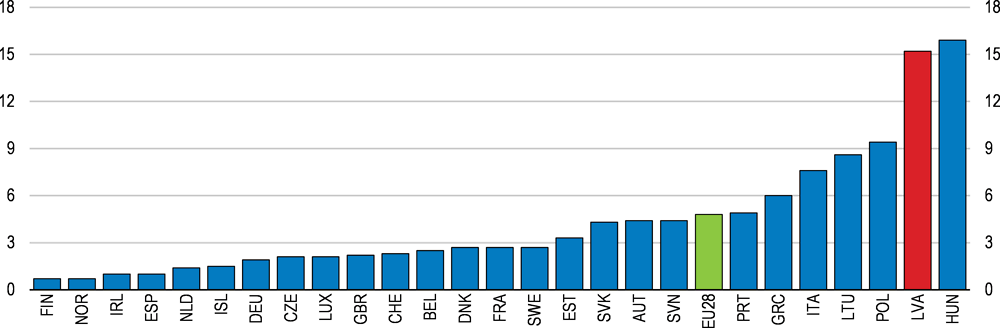

Informal activities remain widespread, although estimates on the size of the shadow economy vary across estimation methods (Figure 23). Tax revenue losses due to under-declaration of income – a criminal activity in Latvia as it is in other countries - limit the government’s ability to invest in infrastructure and social services. Informal firms often work with outdated technologies and are reluctant to grow, as they are trying to hide their activities. Their workers rarely have access to training. All of this is holding back productivity growth. A high share of informality can also hold back investment from formal firms who may fear unfair competition from enterprises that keep their costs low by failing to comply with tax laws and business regulation (Distinguin et al., 2016). Finally, informal workers typically have limited pension rights, resulting in a high risk of old-age poverty.

For all of these reasons it is important for the Latvian government to continue coordinated efforts across all ministries to develop a strategy to fight informality. Weak enforcement of tax and labour laws are the main issues, while compliance with product market regulations, which are relatively business friendly overall, is less a matter of concern. To reduce undeclared work, a recent agreement with social partners in the construction sector, where informality is widespread, seems promising and could be extended to other sectors. The government has also developed guidelines for public procurement procedures to help buyers assess bidders’ compliance risks, including with tax and labour laws. The length of court procedures for tax crimes has declined and electronic case management system is in place.

Figure 23. Informality is widespread

1. The size of shadow economy is estimated from firm-level information. Under-declared corporate profits and under-reported wage payments by registered firms in the three Baltic countries are based on survey data.

Source: Sauka, A and T. Putniņš (2019), Shadow Economy Index for the Baltic Countries 2009-2018, Stockholm School of Economics in Riga (SSE Riga); Schneider, F. (2017) “Implausible Large Differences in the Sizes of Underground Economies in Highly Developed European Countries? A Comparison of Different Estimation Methods” CESifo Working Paper No. 6522, Munich.

Research shows that raising tax morale, i.e. voluntary compliance with tax laws, is crucial in the fight against informality (Williams and Horodnic, 2015). Tax authorities have improved wages and career prospects to attract more qualified personnel and are working towards making better use of information and communication technology (ICT) and strengthening the analytical capacity of the State Revenue Service to target audits at taxpayers with a high probability of committing tax evasion (Table 8). Information exchange and cooperation between different law enforcement agencies is being improved and these important efforts need to continue. Tax authorities have rated individual compliance records and risks. Taxpayers will be allowed to share their rating to enhance their reputation. The hope is that this will encourage formality, as taxpayers can control each other to some extent.

However, mild sentences continue to impede the fight against economic crimes, including under-declaration of income and tax evasion. For example, during 2014-2016 there were only three prison sentences for tax crimes. Yet, higher detection risks and fines have been shown to be very effective in strengthening tax morale and combatting informality, including in Latvia (Mickiewicz et al., 2017). They can also help increase productivity by helping to better allocate workers to higher productivity jobs (Meghir et al., 2015). The government foresees amendments to the Tax and Duties Law that would strengthen fines for tax code violations, which is welcome.

Raising trust in the fairness and impartiality of government institutions, which is now low (Figure 24), would help fight informality and improve compliance with tax laws (Mickiewicz et al., 2017). Providing for transparency and consultation in law-making and ensuring that law enforcement agencies build good relations with businesses and citizens, helping them to comply with laws, will thus be equally important as fines for infractions. The recent “Consult first” initiative can be helpful in this respect. Under this initiative, large law enforcement agencies, including the tax and insolvency administrations, will support business compliance rather than fine immediately, provided that infractions are non-essential. A model-based approach will help target enforcement at the highest risks and there will be regular client surveys.

Figure 24. Trust in national institutions is low

% of respondents

The government has also foreseen larger budgets and new posts for several law enforcement agencies, including the Financial Regulator, the Financial Intelligence Unit and the Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau (KNAB). This is welcome and demonstrates Latvia’s strong commitment to fight informality and corruption. Nevertheless, actual hiring procedures have been slow, partly due to security protocols, and staff has not increased as planned in any of these institutions. Providing attractive wages and career prospects would facilitate hiring of qualified personnel. Finally, as stressed in previous Economic Surveys, budgetary independence of the KNAB would improve public trust in its capacity to fight corruption in all spheres of the Latvian society (Table 8).

Table 8. Past OECD recommendations on informality

|

Topic and summary of recommendations |

Summary of action taken since 2017 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Strengthen the budgetary independence of the Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau (KNAB) |

The budget has been significantly increased, but continues to be proposed by the Council of Ministers and approved by parliament annually. |

|

Make better use of information and communication technologies for tax law enforcement |

Regulation is underway that would require companies using electronic devices for the registration of sales and taxes, such as electronic record keeping cash registers, to transmit monthly sales data to the State Revenue Service. The State Revenue Service’s tax debt collection department is implementing ICT and data analysis systems to better target audits at high-risk tax payers. New regulations facilitate regular transmission of bank account data of persons or companies suspected of tax fraud or illicit financial transactions. The State Revenue Service is working on a system that would allow it to match data received from foreign tax authorities automatically with its own data. Currently matching is performed manually. The State Revenue Service is working with the World Bank on developing better tax gap indicators. |

Improving access to social services

Improving pension adequacy

Latvia’s pension system comprises a notional defined benefits (NDC) pillar and a mandatory funded pillar. Basic and minimum pensions for people with insufficient contributions are very low. Basic pensions are not automatically indexed. Old-age poverty is high (Figure 25), particularly among women. The government is progressively making the indexation of old-age pensions more favourable for pensioners with long contribution periods, by increasing the share that is indexed to wage rather than consumer price inflation. It also has plans to increase basic and minimum pensions as of 2020 and index basic pensions to consumer price inflation as of 2021. If those plans are approved basic pension for seniors without entitlement to social insurance pensions will reach about 10% of the average wage in 2019, compared to 20% on average in the OECD.

Starting in 2019 survivors receive 50% of their deceased spouses’ pension benefits for twelve months after their death, but beyond this period there are no survivors’ pensions. Indexation was made more favourable for individuals with long contributions histories in 2019 and premia for each contribution year were increased. These are welcome steps, although more may be needed to noticeably lower old-age poverty. The increase in the statutory pension age to 65 years by 2025 is another step in the right direction. Linking it to life expectancy after that, as in Denmark, would take some pressure off the system and help lower the number of workers that retire with a pension that is too low.

The share of pensioners claiming minimum or basic pensions is projected to increase sharply owing to volatile employment, high informality and a falling weight of pre-1996 contributions. The self-employed and workers under the microenterprise regime – together around a quarter of employment - pay lower pension contributions, increasing the risk that they will receive no more than a minimum pension. In fact, until end-2017 the majority of the self-employed have not made any contributions at all. Contributions should be aligned across different employment statuses to strengthen contribution records. Introducing mandatory pension savings for all, as in Denmark, should be considered in the longer term.

Figure 25. The poverty rate for elderly people is high

Share of population over 64 with household income below 50% of the median, 2017 or latest available year

Improving healthcare services

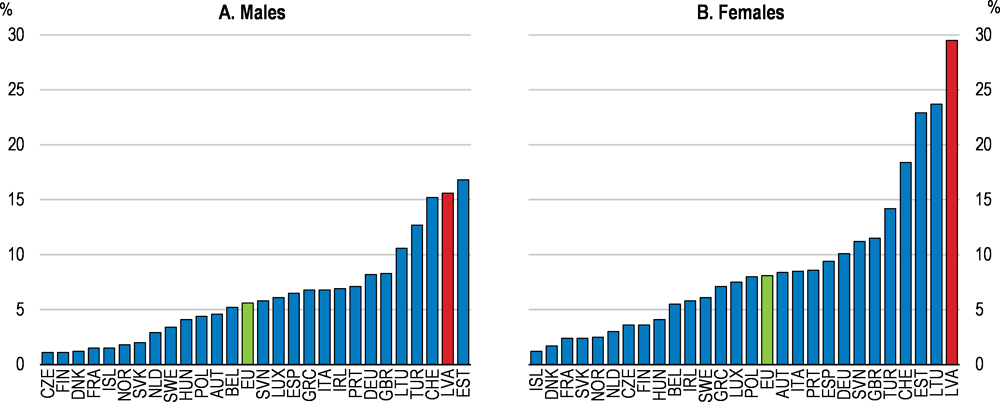

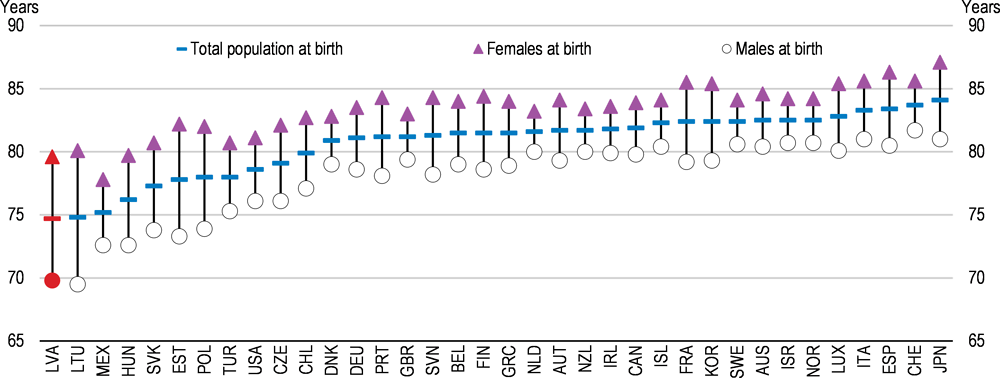

While life expectancy has increased quite rapidly over the last 15 years it is still among the lowest in the OECD (Figure 26) and there are large differences by income and sex. Both the gap between men and women and between Latvians with high and low educational attainment is about ten years. Risky behaviour plays a role, as men and people with lower education and income are more likely to smoke or consume alcohol excessively. The incidence of obesity is also high in socio-economically disadvantaged groups. The government is taking action with higher taxes on alcohol and tobacco and information campaigns on the benefits of a healthy lifestyle and some extra training for pharmacists (Table 9). These important efforts need to continue. But limited access to healthcare for lower-income groups due to high out-of-pocket payments also plays a role.

Figure 26. Life expectancy remains low and unequal

Life expectancy at birth, 2016 or latest available year

Table 9. Past OECD recommendations on healthcare and pension services

|

Topic and summary of recommendations |

Summary of action taken since 2017 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Lower operating costs of the compulsory pension system, for example by introducing a low-cost fund as the default choice. |

Legislation passed in late 2017 lowered the cap on the fixed part of the fee and imposed stricter requirements for performance-related higher charges. |

|

Reduce out-of-pocket payments, especially for the low-income population |

Higher financing for healthcare helped reduce waiting lines and out-of-pocket payments. |

|

Develop key service quality and performance indicators for health care providers at national, local and provider-level |

There are various ongoing initiatives financed by EU Structural Reforms Support Program to develop performance indicators, including at the provider-level data to guide health inspections. |

|

Deliver preventive care more effectively by expanding the activities nurses and pharmacists are allowed to carry out, notably in rural areas where services are scarcer. |

Pharmacists now receive training for cardiovascular risk identification. |

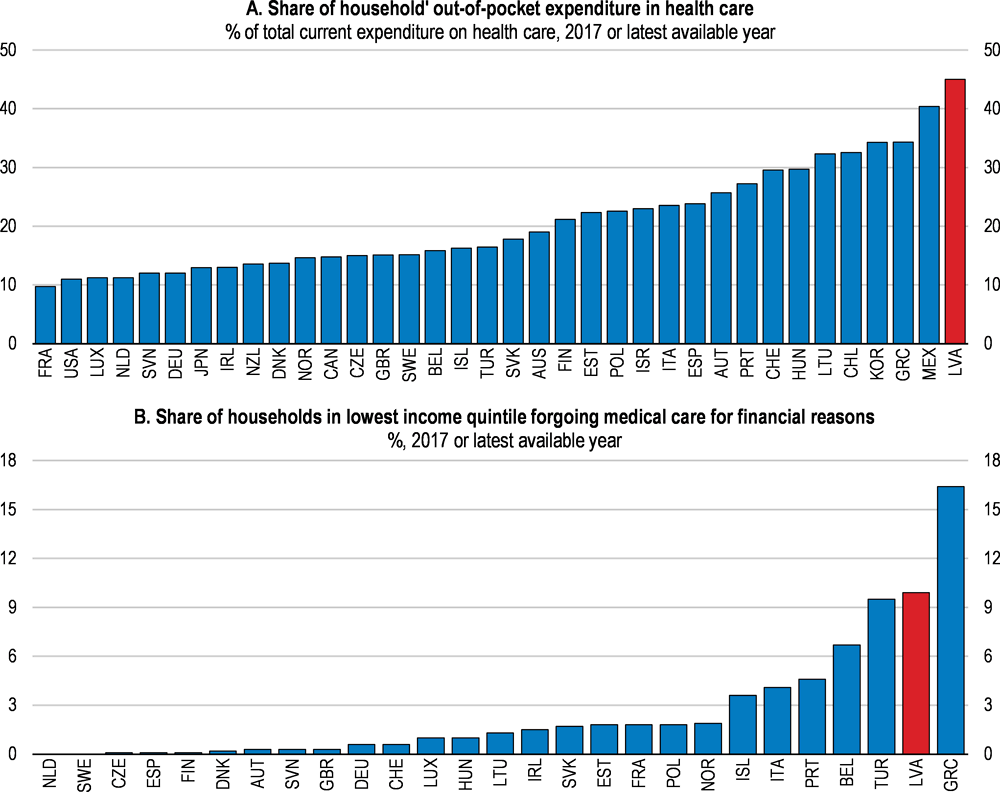

Public spending on healthcare, funded via general tax revenues, is 3.8 % of GDP, well below the OECD average and neighbouring Estonia and Lithuania. Out-of-pocket payments and, as a result, the share of patients who forego doctors’ visits are high (Figure 27). Since 2017, the government has lifted annual limits on services, in particular for cancer treatment, which forced patients to either wait for treatment the following year or pay by themselves. This has led to a welcome reduction in waiting times and out-of-pocket payments. Yet, more could be done to improve access to healthcare. The cap on total annual contributions for inpatient and outpatient treatment is too high and should be reduced: it amounts to around 570 euros (excluding the purchasing of drugs, spectacles and dental services), compared with 300 euros in Estonia and 90 euros in the Czech Republic (WHO, 2017).

Figure 27. Many Latvians skip doctors’ appointments to avoid high out-of-pocket payments

In 2018, the government has increased spending on healthcare by 22% and planned to finance it partly through a new earmarked social contribution. As of 2019, self-employed, workers under the microenterprise regime and pensioners receiving their pension from a foreign country have to pay a levy increasing to 5% of the minimum wage by 2020, otherwise they will only have access to a minimum basket of health services. Risk that a high share of the population affected by the reform does not pay the levy is non-negligible. At end 2018, only around 5% of this population at risk of being excluded from parts of the healthcare basket had paid social security contributions. Excluding parts of the population from the full basket of healthcare services is likely to endanger their health status and lead to higher costs later on. In addition, raising a new levy will almost certainly involve considerable administrative costs. The fact that the reform was postponed to mid-2019, as doctors found it impossible to determine patients’ insurance status with the available IT system, is a case in point. It seems preferable to keep universal healthcare, as now envisaged by the new government, and finance spending increases via general taxes.

Analyses of the hospital system performance highlight that despite progress in reorganising the hospital system, much remains to be done to improve its efficiency and the quality of services (OECD, 2018b). For instance, the 30 day mortality after admission for a heart attack in Latvia is the highest in the EU and twice the average (OECD/EU, 2018). The envisaged centralisation of complex services and the development of cooperation areas for local hospitals would be steps in the right direction and could be accompanied by a broader review of performance, accountability and governance mechanisms in hospitals. Shortages of skilled medical staff are growing and could be eased by improving wages and working conditions while facilitating return migration and immigration of medical professionals.

Improving environmental outcomes and regional cohesion

Regional disparities are high and environmental outcomes should improve

Regional disparities in income per capita are large and relate to a rapid depopulation and ageing (European Commission, 2019). All regions besides the Riga metropolitan area have lost a considerable share of their younger population, as a result of internal and external migration. The Latgale and Vidzeme regions, where GDP per capita is less than 40% of what it is in Riga, suffer from their remoteness. Better transport infrastructure and services and better access to affordable housing would strengthen labour mobility and thus improve economic opportunities for workers in disadvantaged regions. Together with increasing use of digital technologies, this would also facilitate regional specialisation and interregional sharing of knowledge, innovations, amenities, resources.

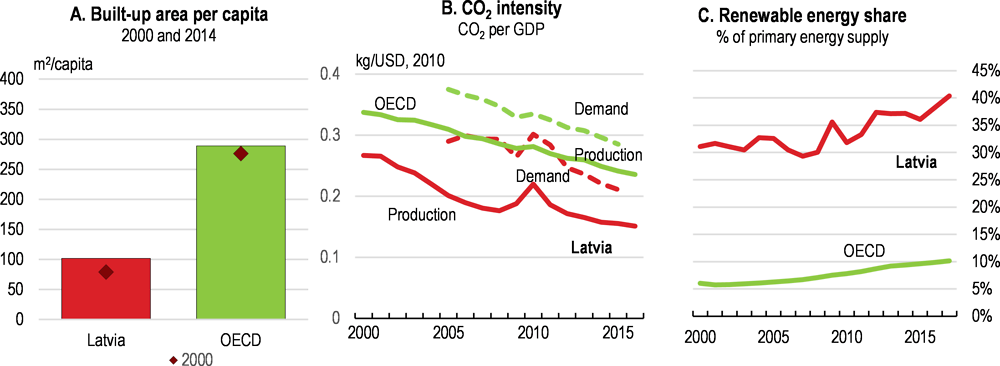

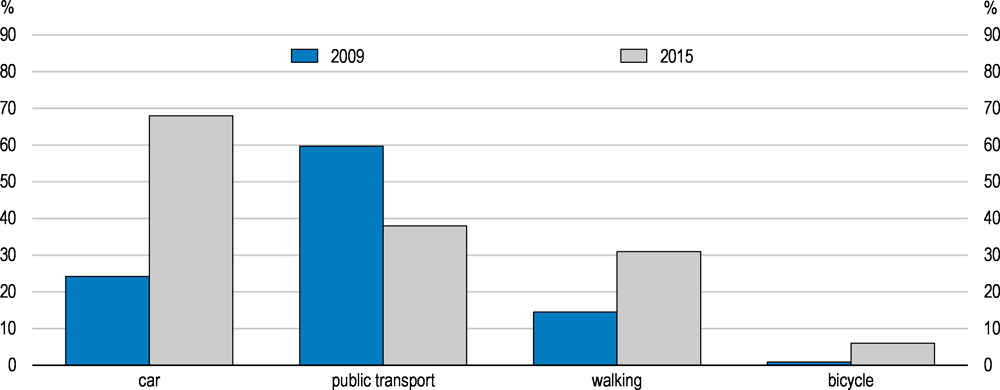

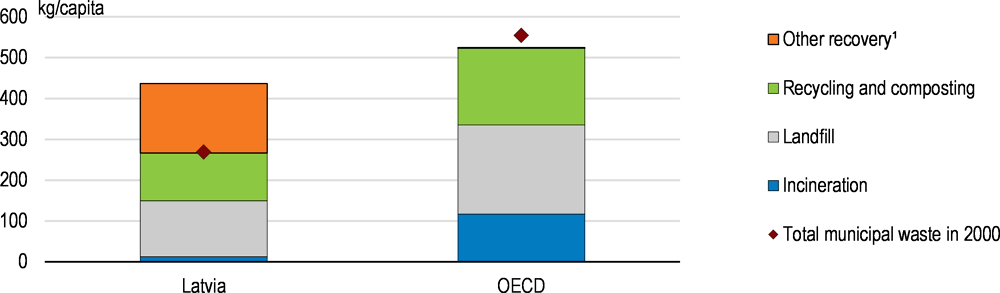

Latvia is richly endowed with pristine forests as well as beautiful sea and landscapes and well-established nature conservation traditions. Forests cover 54% of the national territory, one of the largest shares in the OECD. Built-up area per capita is low, though rising faster than elsewhere (Figure 28, panel A). Latvia’s per capita CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion are lower than anywhere else in the OECD, thanks to an unusually large share of renewable energy production (Panels B and C). It mostly consists of hydropower and biomass, which meets most energy needs in the housing, commercial and industrial sectors. Biomass production needs to become more sustainable, though. Together with a vibrant wood industry it is endangering the role of Latvia’s forests as a carbon sink. The contribution of land use, land use change and forestry to reducing greenhouse gas emissions has diminished significantly since 2004 and net emissions from this source were actually positive in 2014 and 2015.

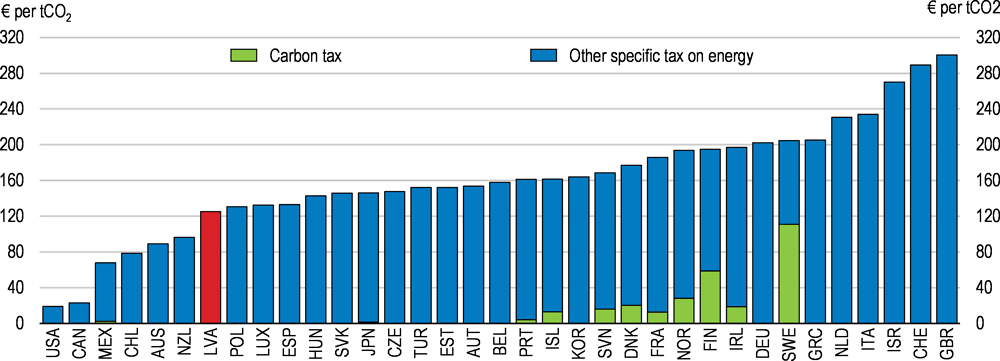

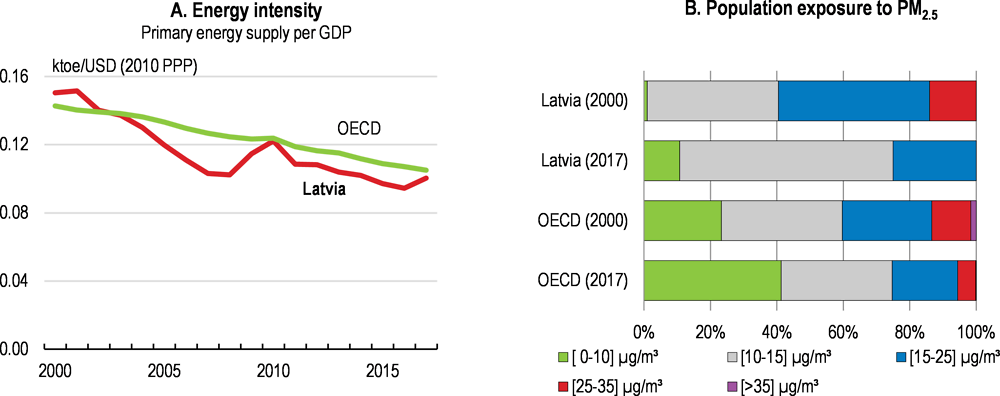

The energy intensity is below the OECD average, but has not fallen over the past 10 years (Figure 29, panel A). Although CO2 intensity is low, a steeper decline is needed for Latvia to meet its target to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions outside the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) by 6% relative to 2005 levels by 2030 (European Environment Agency, 2017). Most of Latvia’s GHG emissions fall outside of the EU emissions trading system and investments in energy efficiency, renewable energy and public transport are necessary to meet emission reduction targets. This would also improve health outcomes. Despite notable progress with reducing air pollution, most of the population remains exposed to small particle emissions above the limit of 10 micrograms per cubic meter recommended by the World Health Organisation (panel B). Growing urban transport in fuel-inefficient cars and the burning of biomass, often in inefficient furnaces continue to play a role.

Figure 28. The renewable energy share is high and CO2 intensity is relatively low

Source: OECD (2018), Land cover, OECD Environment Statistics (database); OECD (2018), Green Growth Indicators, OECD Environment Statistics (database), OECD National Accounts (database) ; IEA (2018), IEA World Energy Statistics and Balances (database).

Figure 29. Energy intensity and population exposure to pollution need to fall further

Source: IEA (2018), IEA World Energy Statistics and Balances (database), OECD (2018) National Accounts (database); OECD (2018), Exposure to air pollution, OECD Environment Statistics (database).

Improving access to affordable housing, its quality and energy efficiency

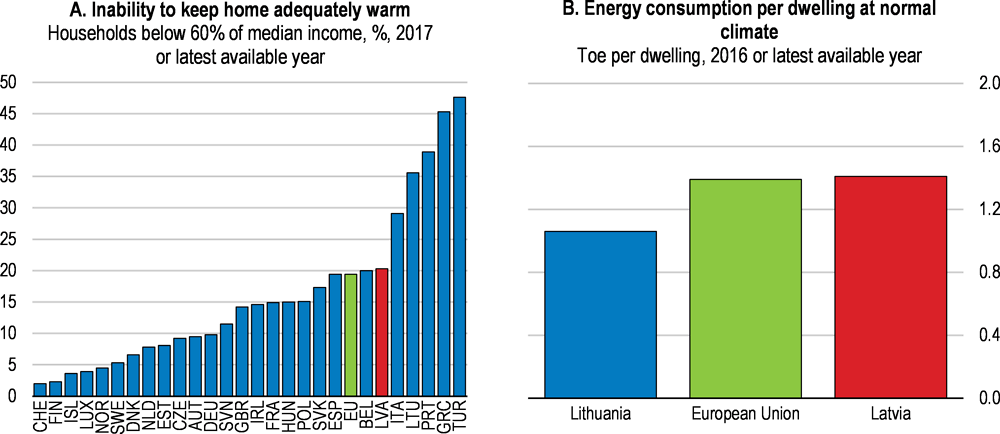

Improving access to affordable and energy-efficient housing would help address skill shortages and improve environmental outcomes. Housing conditions are poor in Latvia (Figure 30) and a lack of affordable housing in the Riga region and other cities with good employment opportunities hinders better job matches. This is partly responsible for high regional disparities in employment. Residential housing development has stagnated over the past 25 years, as only 3% of the residential housing stock was built after 1993. Heating bills in old apartment blocks can easily be three times higher than in newly constructed multi-unit buildings (Eurofund, 2016) and many lower-income households have trouble keeping their house warm (Figure 31, Panel A). While there have been improvements in energy efficiency, energy consumption per dwelling is significantly lower in neighbouring Lithuania (Panel B), suggesting that further improvements are possible with beneficial effects for well-being, air quality and Latvia’s contribution to lowering CO2 emissions.

Figure 30. Many families live in substandard housing

Severe housing deprivation rate¹, %, 2017 or latest available year

1. Severe housing deprivation rate is defined as the percentage of population living in the dwelling that is considered as overcrowded and exhibiting at least one of the housing deprivation measures (leaking roof, no bath/shower and no indoor toilet, or a dwelling considered too dark).

Source: EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC).

Figure 31. Higher building energy efficiency would bring benefits for well-being

After 1990 the transfer of ownership to sitting tenants at below market prices led to very high home ownership rates, as in other Central and Eastern European countries. More than 70% of the population own their home without a mortgage, but many lack the resources to maintain it. More than 80% of the population would not be able to buy or rent a home without spending more than 30% of their disposable income on housing according to data collected by the Ministry of Economy, making it very difficult to move. Social housing makes up less than 1% of the housing stock. Only few households are eligible and waiting times are long. Candidates can only apply in the municipality where they already live, making it difficult to move for a job. The quality of social housing is also low due to a lack of adequate maintenance, for which many municipalities lack resources. Overall, the rental market is under-developed in Latvia: 13% of households live in rented dwellings compared to about 24% on average across OECD countries. Informal renting is widespread and about a quarter of tenants in Latvia did not have a written contract in 2015 (Kull et al., 2015).

The profitability of residential buildings is low, partly because there is a lot of competition through informal renting (Hussar, 2016). This creates legal uncertainty for transactions and investment, as buyers often find that their newly acquired apartment is subject to an informal rent agreement that cannot be easily dissolved. A draft law foresees a requirement for rental contracts to be registered in the land register. Non-compliant landlords will not have access to a new accelerated dispute settlement procedure, which is expected to shorten procedures from 2-4 years to 4 months, while tenants will not be protected when the owner changes. This is expected to improve the enforcement of tax laws and strengthen investment incentives.

To address skill shortages the government plans to support municipalities, except Riga, to build affordable rental apartments for skilled workers. Including Riga municipality in the programme would yield more efficient results, as shortages are particularly high in this area. In addition, the needs of other income groups have to be addressed, as well, and this requires stronger engagement to preserve the existing housing stock and develop both social housing and affordable opportunities to rent and buy on the private market. The government should advance quickly with its plan to develop a Strategy for Affordable Housing.

A vibrant rental market requires protection of landlords’ property rights to ensure acceptable returns to investment for them and thereby to stimulate investment. But experience from OECD countries with the most developed rental markets suggest that ensuring a degree of tenancy safety and soft rent control for existing contracts can ultimately be in the interest of both parties, as it creates stable demand (Kemp and Kofner, 2010; de Boer and Bitetti, 2014). In contrast, low tenant protection, a high incidence of fixed-term contracts and complete deregulation of rents, can hamper demand for rental housing and hence the development of the rental market sector (de Boer and Bitetti, 2014). The government plans to allow only fixed-term contracts in the future, but fast and efficient dispute settlement procedures may be a better way to balance landlords’ and tenants’ rights.

Take up of EU structural funds to finance energy efficiency investments increased considerably since 2009, but still only 3% of the multi-owner housing stock were renovated until 2017. The government plans to renovate another 4% until 2023. Given the age and low energy efficiency of the building stock, this target could be more ambitious, but it requires overcoming barriers to investment.