New Zealand’s housing supply has not kept pace with rising demand, including from net immigration. Affordability has worsened, particularly for low-income renters. Government action is underway to allow new housing through initiatives such as the Urban Growth Agenda, KiwiBuild and the Housing and Urban Development Authority, but further steps are needed to improve well-being. Clear overarching principles for sustainable urban development and rationalisation of strict regulatory containment policies would allow the planning system to better respond to demand for land. Incentives for local governments to accommodate growth could be increased by giving them access to additional revenue linked to local development. More user charging and targeted rates would also help to fund infrastructure required to service new housing. Government delivery of affordable housing through KiwiBuild should be re‑focused towards enabling the supply of land to developers, supporting development of affordable rental housing and further expanding social housing in areas facing shortages.

OECD Economic Surveys: New Zealand 2019

Chapter 3. Improving well-being through better housing policy

Abstract

Housing is important for well-being (section 3.1). Low supply responsiveness, low interest rates and strong population growth due to migration (Chapter 2) have contributed to rapidly increasing house prices in New Zealand. Affordability is now poor by international comparison, which is a key comparative well-being weakness (Chapter 1). Low-income renters have been severely affected (section 3.2). Policy measures are recommended to improve well-being, with a focus on increasing housing supply responsiveness and outcomes for low-income renters (sections 3.3 to 3.5). Macro-prudential restrictions imposed by the Reserve Bank to protect financial stability also affect affordability (see Key Policy Insights).

Housing is an important determinant of well-being

Apart from meeting the basic need for shelter, housing provides a foundation for family and social stability, facilitates social inclusion and contributes to health and educational outcomes, access to services and a productive workforce. How land is used for housing shapes the immediate environment as well as transport and resource use.

International research shows a connection between housing satisfaction and life satisfaction, self-esteem and perceived sense of control (Coates, Anand and Norris, 2015[1]) as well as a link between physical housing condition and subjective well-being (Clapham, Foye and Christian, 2017[2]). Living in poor-quality or overcrowded housing is strongly correlated with a range of health problems including respiratory conditions, exposure to toxic substances and injuries (Rohe and Lindblad, 2014[3]). Adults who experienced housing deprivation when they were younger remain more likely to suffer from ill health (Marsh et al., 2000[4]) and inadequate housing adversely affects children’s educational outcomes (Cunningham and Macdonald, 2012[5]). Residential segregation may cut off segments of the population from opportunities to participate in societal progress (OECD, 2016[6]). Unaffordable housing can trigger various forms of deprivation, such as poor nutrition, and is associated with other trade-offs that can harm health (Pollack, Griffin and Lynch, 2010[7]). Increasing property prices benefit owners, who tend to be wealthier, at the expense of renters.

Access to good-quality affordable housing is therefore a means to promote social policy goals that include prevention of poverty and social exclusion, better access to health, education and social capital, and labour market inclusion. Reflecting its importance for well-being, housing outcomes are one of twelve indicator topics under the New Zealand Living Standards Framework (Chapter 1). In addition to its distributional consequences, housing also affects other indicators, notably the environment, health, income and consumption, jobs and earnings, safety, social connections and subjective well-being. More evidence would be needed to evaluate the incremental effect of housing policy reform on the full range of well‑being indicators. Analysis of the effects on subjective well-being of easing supply constraints and increasing security of tenure for renters would be particularly valuable to complement the Social Investment Agency (2018[8]) study of social housing, which exploited the rich and innovative Integrated Data Infrastructure database available to NZ-based researchers.

Evidence is mixed on the well-being benefits of owning rather than renting (Clapham, Foye and Christian, 2017[2]). Despite a correlation, there is a lack of convincing evidence that homeownership causes better health, and benefits need to be weighed against the potential for financial obligations to cause greater stress. Labour mobility may be lower and thus unemployment higher among owner-occupants than renters (Oswald, 1996[9]; Caldera Sánchez and Andrews, 2011[10]). Evidence is also mixed on the effects of homeownership on children’s educational outcomes, with some earlier studies possibly mistaking selection differences in who becomes a homeowner with the effect of homeownership itself (Holupka and Newman, 2012[11]). Homeownership is one way to save for retirement and provide protection against rent increases, but can divert households from other forms of wealth-building (Salvi del Pero et al., 2016[12]) and the evidence that home ownership is a superior vehicle for long-term wealth accumulation is mixed (OECD, 2011[13]).

Housing affordability has worsened

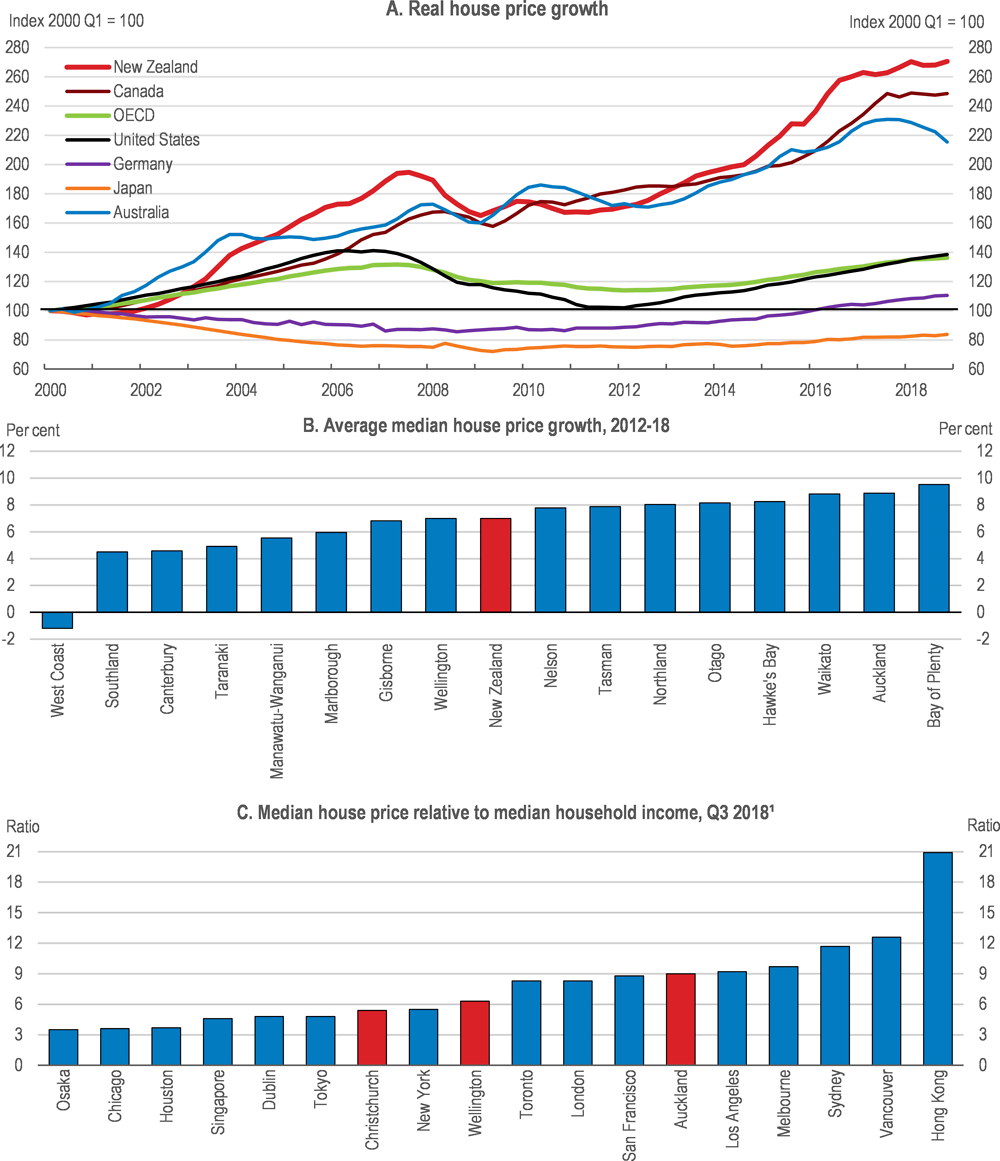

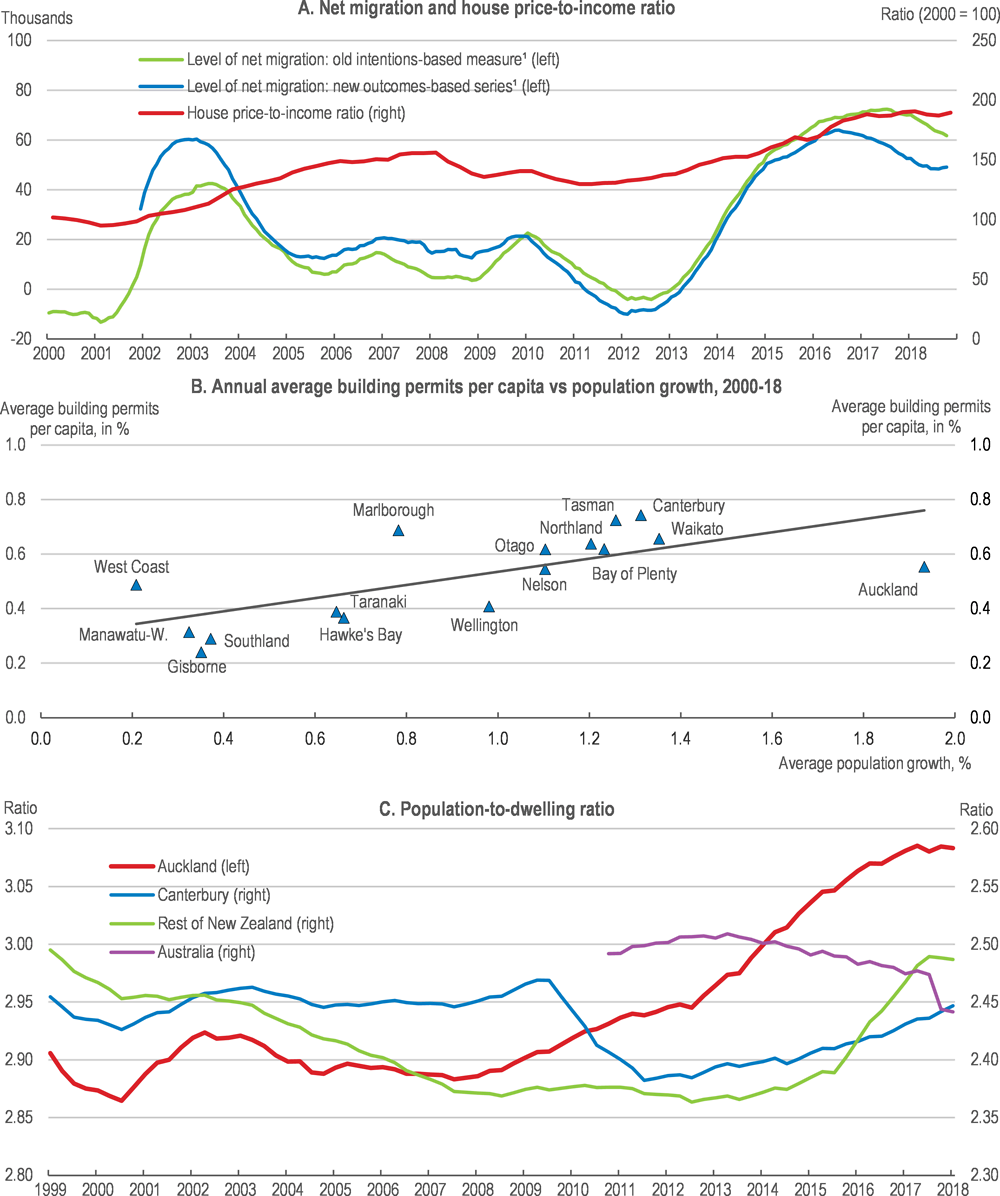

House prices in New Zealand have soared, outstripping income growth (Figure 3.1, panel A). Ratios of house prices to incomes and to rents now far exceed their long-term averages. Prices have risen most in Auckland (panel B), where the ratio of median prices to incomes is now comparable to or larger than in many much larger foreign cities (panel C). Average prices have been largely flat in Auckland since late 2016, but have continued to increase elsewhere in New Zealand.

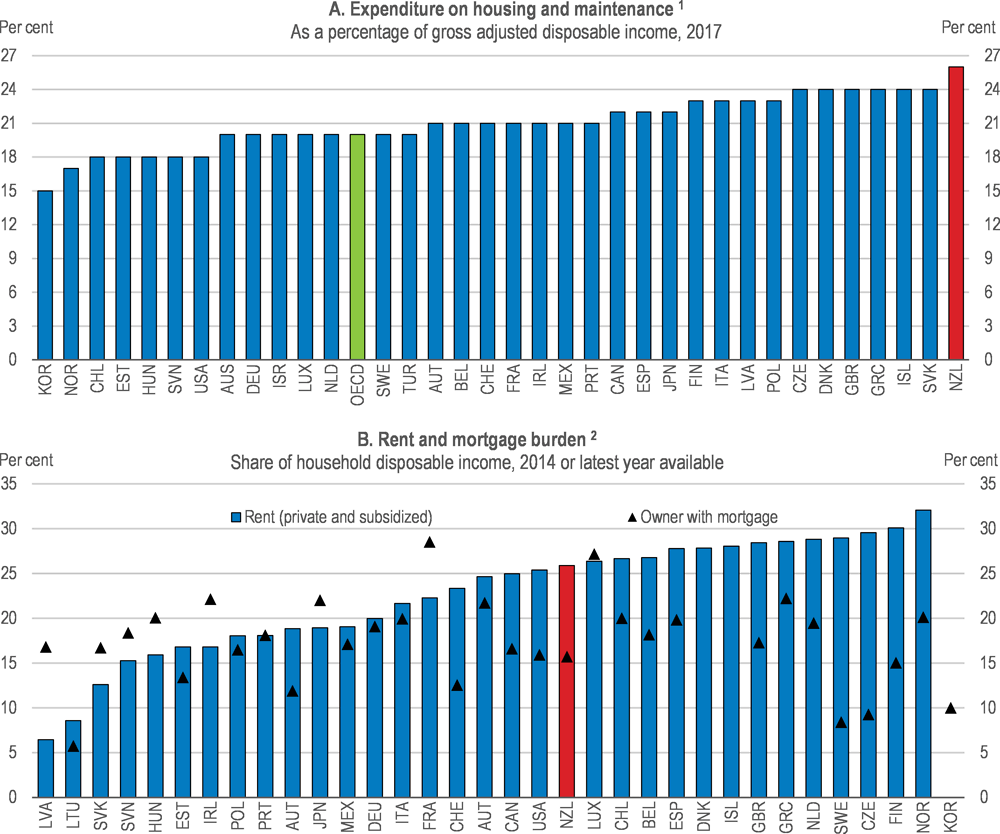

Housing costs are a higher share of income than in most OECD countries, though data issues mean New Zealand’s exact ranking is unclear. National accounts data indicate that New Zealanders spend the highest share of income on housing among OECD countries (Figure 3.2, panel A). These data incorporate imputed estimates of rental prices for owner-occupied housing, which are biased upward because rental properties used as a proxy are not stratified by location, giving a higher weight to Auckland where rental properties are both more common and more expensive. A sensitivity test, involving a 20% reduction in imputed rents, would still see New Zealand among the top few countries for housing costs, although no longer an outlier. Actual expenditure on housing appears more internationally typical (panel B), but in this case is biased downward because a gross rather than disposable measure of income is used. The size of this bias is considerable, as the gap between gross and disposable income is between 6% and 23% at the average wage (which is close to the median household income for renters) depending on family size and structure (OECD, 2018[14]). Differences in the types of mortgages available and therefore repayment schedules also affect cross-country comparability of actual expenditure on housing.

Figure 3.1. House price growth

1. For Osaka and Tokyo, data refer to Q3 2017.

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook database; Real Estate Institute of New Zealand; Demographia (2019), 15th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2019, http://www.demographia.com/dhi2019.pdf.

Figure 3.2. Housing costs for households

1. Includes actual and imputed rents for housing, expenditure on furnishings and equipment, maintenance and repair of the dwelling. Imputed rents are likely to be biased upward for New Zealand because rental properties used as a proxy are not stratified by location, giving a higher weight to Auckland where rental properties are both more common and more expensive.

2. Median of the mortgage burden (principal repayment and interest payments) or rent burden (private market and subsidized rent). In Chile, Mexico, New Zealand, Korea and the United States gross income instead of disposable income is used due to data limitations.

Source: OECD (2017), How’s Life? and OECD, Housing Affordability Database.

Low-income renters have been severely affected

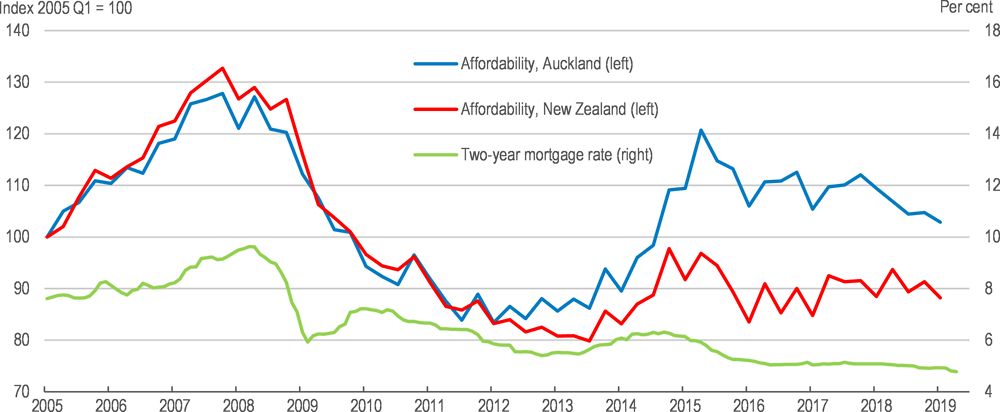

Around half of people with low incomes own their own home (Figure 3.3). For owner-occupiers, low interest rates have contributed to price growth but also reducing financing cost, so that affordability remains better than immediately preceding the global financial crisis, even in Auckland1 (Figure 3.4). Affordability could deteriorate rapidly, however, if interest rates were to rise from recent record lows as around two-thirds of outstanding mortgage balances are scheduled to be re-priced within the next two years.

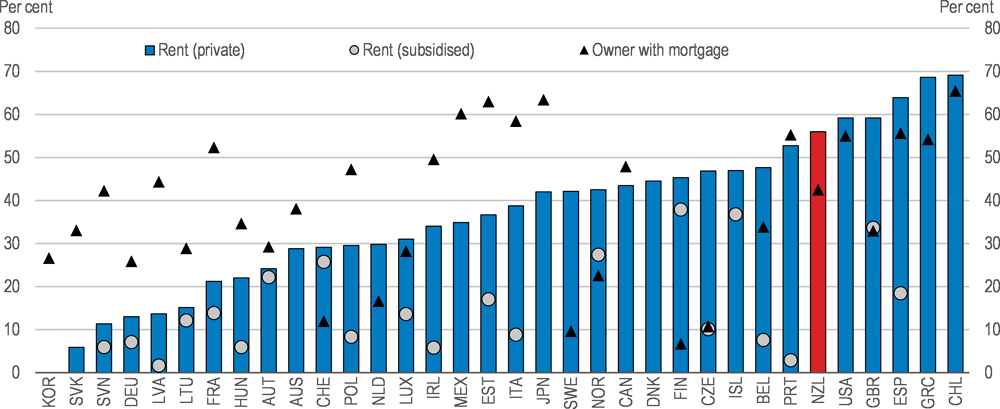

Figure 3.3. The homeownership rate is just below the OECD average

Figure 3.4. Housing affordability for owners has been supported by low interest rates

Note: The affordability index defined by the Massey University Real Estate Analysis Unit takes the ratio of the weighted mortgage interest rate as a percentage of median selling price to the average wage. The lower the index, the more affordable the housing.

Source: Massey University Real Estate Analysis Unit, Home Affordability Report, various quarterly reports, http://www.massey.ac.nz/massey/learning/colleges/college-business/school-of-economics-and-finance/research/mureau/mureau_home.cfm.

The burden of high housing costs has fallen disproportionately on those with lower incomes, with the majority of low-income renters spending more than 40% of their gross income on housing (Figure 3.5). Housing costs averaged 45% of income for the bottom fifth of households aged under 65 in 2017, up from under 40% in the early 2000s and 23% in 1990 (Perry, 2018[15]). Around one in 10 New Zealanders live in a crowded household, just above the median for OECD countries (Statistics NZ, 2018[16]; OECD, 2017[17]).

Māori have poor housing outcomes

Compared with people from European backgrounds, Māori are four times as likely to live in crowded homes and around five times as likely to be homeless (Statistics NZ, 2018[16]; Twyford, 2018[18]; Amore, 2016[19]). People from Pacific or Asian backgrounds also suffer high rates of crowding and homelessness. The government has recently established a dedicated Minister and unit for Māori Housing and is investigating initiatives to reduce barriers to building on Māori land. These include difficulties in using Māori land as security for finance, zoning restrictions, getting agreement from shareholders in land blocks and poorly coordinated or communicated government responses (NZ Productivity Commission, 2012[20]). Analysis across OECD countries with substantial indigenous populations highlights the need to recognise indigenous land rights and facilitate economic development through measures such as transferable long-term leasing of land parcels and support for land consolidation that overcomes problems of fragmentation (McDonald, forthcoming[21]).

Housing quality is low

About 30% of NZ homes are poorly insulated and a quarter of homeowners and half of renters report problems with dampness or mould (OECD, 2017[22]). Around 7% of adults report a need for immediate repairs and maintenance on the property they live in, with rental houses twice as likely to be poorly maintained (BRANZ, 2017[23]; Treasury, 2018[24]). Cold, leaky and damp wooden houses are common, partly owing to the abundance of forests and the historic risk of building masonry and stone buildings on a fault line. New Zealand has the highest rate of respiratory illnesses in the OECD (one in four people suffer from asthma), and 40 000 hospital admissions per year could be avoided (IEA, 2017[25]). Prevention and remediation of indoor dampness and mould are likely to reduce health risks and thereby improve well-being (Teasgood et al., 2017[26]).

A number of factors have contributed to unaffordability

Strong demand in the presence of weak supply responsiveness has been responsible for rapid price escalation. Increasing incomes have pushed up demand but can only explain a small part of price growth as the house-price-to-income ratio has risen sharply (Figure 3.6, panel A). As noted above, mortgage interest rates are low, which combined with greater access to credit has increased demand for owner-occupied and investment properties. Non-resident buyers have also contributed to demand for NZ housing, although their share of overall purchases (3%) is small (Statistics NZ, 2018[27]). High immigration and relatively low net outward migration of NZ citizens has led to strong net immigration recently (Chapter 2), boosting demand for housing. A synthesis of evidence from eight OECD countries suggests that a 1% increase in the population of a city due to immigration can be expected to raise rents by 0.5% to 1% and house prices by twice as much (Cochrane and Poot, forthcoming[28]). Analysis of New Zealand between 1962 and 2006 indicates a larger, 10% increase in house prices from a 1% increase in population, with a key explanation being the inability of NZ housing construction to rapidly respond to new demand from immigration (Coleman and Landon-Lane, 2007[29]). Another possible explanation – immigration pushing up house prices through higher expectations about house prices – is also related to weak supply responsiveness as the supply response conditions expectations and thus speculative demand.

Figure 3.5. Most low-income renters face very high housing costs

Share of population in the bottom quintile of the income distribution spending more than 40% of disposable income on mortgage and rent, by tenure, 2014 or latest year available

Note: In Chile, Mexico, New Zealand, Korea and the United States gross income instead of disposable income is used due to data limitations.

Source: OECD, Housing Affordability database, Figure HC1.2.3, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

The supply response has been constrained by restrictive and complex land-use planning, infrastructure shortages and insufficient growth in construction-sector capacity (OECD, 2017[30]). In aggregate, New Zealand has intermediate housing supply responsiveness, higher than in many European countries but well below that in North America and some Nordic countries (Caldera Sánchez and Johansson, 2011[31]). Supply has failed to keep up with rapid population growth in Auckland in particular (Figure 3.6, Panel B). The shortage in Auckland is estimated at around 40 000 to 55 000 dwellings (Coleman and Karagedikli, 2018[32]). Unlike in Australia, the population-to-dwelling ratio has increased despite an ageing population that would, all else equal, be expected to reduce the average number of people per household (Panel C). The important role of planning restrictions in high house prices is evident from the nearly nine times ratio that existed between the price of land just inside and outside Auckland’s (former) Metropolitan Urban Limit (NZ Productivity Commission, 2012[20]). Across all five of New Zealand’s largest cities and after correcting for other factors, land zoned for urban use close to the rural-urban boundary is valued at least twice as highly as similar rural land (MHUD, 2018[33]). One study estimates that land use constraints could be responsible for 56% of the price of an Auckland home, based on the difference in the value of land depending whether it can have a house on it (Lees, 2017[34]). Unresponsive housing supply has been identified as the most important policy factor holding back NZ labour productivity due to skills mismatches (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2017[35]).

Figure 3.6. Factors driving house price growth

1. Cumulative data for the past four quarters. Before June 2014, the outcomes-based series has been extended using Stats NZ's discontinued experimental series.

Source: Stats NZ; Australian Bureau of Statistics; OECD, Economic Outlook database; Reserve Bank of New Zealand (2015), Financial Stability Report, May, Figure 4.3 updated.

Supply constraints have disproportionately affected construction of affordable housing. Land prices have risen more than construction costs, encouraging the construction of high-end housing: as of 2014, only around 17% of newly built houses were valued below the median for the existing stock, down from half in 1990 (NZ Productivity Commission, 2015[36]). Upward pressure on land prices on Auckland’s urban fringe has had a much larger impact on prices at the lower end of the market.

The remainder of this chapter focuses on long-term policy changes that would enhance well-being by improving housing affordability. New Zealand has a number of policies supporting affordable housing, with the majority favouring home ownership (Table 3.2). The importance of distributional outcomes for societal well-being (due, in part, to diminishing marginal benefits as income increases) points to targeting support towards low-income renters. Targeting those with low incomes would assist the government with its priority to reduce child poverty. Increasing housing supply elasticity, while protecting environmental outcomes, is critical to increase affordability for both owner-occupiers and renters and to improve distributional outcomes. Increasing supply responsiveness also offers a potential boost to productivity that is estimated to more than offset negative effects on productivity from recommendations that increase tenure security – and thus serve distributional goals – but could constrain residential mobility (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Simulation of the potential impact of structural reforms

The potential impact of some of the reforms proposed in this chapter can be gauged using simulations based on historical relationships between public policy and labour productivity across OECD countries. The effect of housing policies on labour productivity is estimated based on their effect on residential mobility, which contributes to reducing labour market skills mismatches. The simulations do not account for other channels through which housing policies might affect growth, abstract from detail in the policy recommendations and do not reflect New Zealand’s particular institutional settings.

Table 3.1. Potential long-term impact of housing market policies on labour productivity

|

Change in labour productivity |

|

|---|---|

|

Per cent |

|

|

(1) Increase responsiveness of housing supply |

1.1 |

|

(2) Constrain rent increases for sitting tenants based on market rates |

-0.4 |

|

(3) Increase security of tenure for renters |

-0.2 |

|

Total |

0.5 |

Note: Illustrative policy changes assumed for each measure are as follows: (1) The gap with the leading OECD country (the United States) is halved. (2) The indicator of rent control is increased by 0.4 units (3) The indicator of tenant-landlord regulations is increased by 0.5 units.

Source: OECD calculations based on Adalet McGowan, M. and D. Andrews (2017), “Skills mismatch, productivity and policies: Evidence from the second wave of PIAAC”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1403.

Table 3.2. Affordable housing policies in New Zealand

|

Category |

Policy instrument |

Targeting |

|---|---|---|

|

Homeownership subsidies |

KiwiSaver HomeStart Grant |

Homeowners |

|

KiwiSaver first-home withdrawal |

Homeowners |

|

|

Welcome Home Loan |

Homeowners |

|

|

Kainga Whenua |

Māori homeowners |

|

|

KiwiBuild |

Homeowners |

|

|

Non-taxation of imputed rent |

Homeowners |

|

|

Non-taxation of capital gains |

Homeowners |

|

|

Housing allowances |

Accommodation supplement |

Tenure neutral |

|

Social rental housing |

Income-related rent subsidies |

Social renters |

|

Expansion of social rental stock |

Social renters |

|

|

Rental support and regulation |

Non-taxation of capital gains |

Landlords/renters |

|

Tenancy law |

Renters |

Source: Typology based on Salvi del Pero et al. (2016[12]).

Increasing the responsiveness of housing supply

A lack of national guidance on how local governments should implement the Resources Management Act (the primary land-use legislation) in urban settings and how to reconcile it with planning requirements under the Local Government Act and Land Transport Management Act has led to unnecessarily restrictive and complex land-use regulations (OECD, 2017[22]). Desirable development has been held back, particularly in fast-growing areas, because the planning system under-recognises potential benefits and suffers from a bias towards the status quo (NZ Productivity Commission, 2017[37]). There are examples in other OECD countries of successful reforms that specifically expedite planning in urban areas, such as the 2007 Act Facilitating Planning Projects for Inner Urban Development in Germany.

The National Policy Statement on Urban Development Capacity 2016 (NPS UDC) requires local governments to provide sufficient development capacity, and to enable urban environments to develop and change. The requirement to monitor price efficiency is also valuable, though monitoring published to date does not clearly show differences in land prices across zones. Moreover, the NPS UDC fails to provide principles for sustainable urban development or practical guidance on how to reconcile planning processes under the three major acts. While the NPS UDC calls for local governments to plan sufficient infrastructure provision, councils lack incentives to accommodate growth due to infrastructure funding issues (discussed below). Work underway as part of the central government’s Urban Growth Agenda shows promise in rectifying deep-seated urban planning problems through steps to improve infrastructure funding and financing, enable growth (both up and out), define clear principles for quality urban environments and provide a framework for spatial planning (Box 3.2). By seeking to reduce a broad range of barriers to new supply, the Urban Growth Agenda is a substantial step in the right direction, but further detail is needed on specific policy measures and their implementation to assess the Agenda’s likely success in achieving its ambitious objectives.

The Auckland Unitary Plan, most of which became operative in late 2016, allows greater densification and some expansion of urban development limits. It represents a major step forward in spatial planning, integrating land use, housing, transport, infrastructure and other urban planning issues. Local opposition to specific development from those with vested interests was managed by frontloading consultation through an independent hearing panel that took a broader perspective (this has also been successful in Australian cities, notably in Brisbane). There remains scope to increase density in Auckland around light rail investment and, once storm water investment catches up, in single housing zones immediately surrounding the central business district.

Box 3.2. The Urban Growth Agenda

The Urban Growth Agenda (UGA) is a medium- to long-term plan to increase the housing market’s capacity to respond to demand, bringing down the high costs of urban land and its development to improve housing affordability. The primary focus is on land and infrastructure markets, where the UGA aims to remove barriers to supply. Through accommodating and managing growth, the UGA also aims to improve choices around the location and type of housing, improve access to employment, education and services, assist greenhouse gas emission reduction and enable quality-built environments while avoiding unnecessary urban sprawl. To achieve these objectives, the UGA consists of five interconnected pillars of work.

1. Infrastructure funding and financing: provide a broader range of funding mechanisms for net beneficial bulk and distribution infrastructure; expand local authority borrowing capacity; rebalance development risk from local authorities to the development sector; and develop alternate financing mechanisms such as special purpose vehicles separated from the local authority with debt serviced by revenue from the properties.

2. Urban planning: reform planning regulation, methods and practice to allow growth up and out; define clearly what is meant by quality urban environments and ensure that councils consider the positive impacts that developments can have on amenity (through a new National Policy Statement on Urban Development); and facilitate a better understanding of the costs and benefits from urban development.

3. Spatial planning: embed within the urban development system a pro-growth spatial planning framework that facilitates better co‑ordination of the spatial dimensions of decision making around key issues such as zoning, infrastructure and environmental protection; in the near term, advance partnerships with local government to advance spatial planning.

4. Transport pricing: investigate congestion pricing options for Auckland through the joint Auckland and central government project “The Congestion Question”; price the full marginal costs of growth infrastructure; and consider a range of options aimed at a more sustainable and equitable future transport revenue system.

5. Legislative reform: ensure that regulatory, institutional and funding settings are collectively supporting the UGA objectives.

Compact urban development offers a number of benefits, with 69% of more than 300 published analyses worldwide finding positive effects (Ahlfeldt et al., 2018[38]). Agglomeration economies generated by cities are an important factor in knowledge diffusion and thus productivity growth, and population density has been a strong predictor of economic performance in European countries (Ahrend and Schumann, 2014[39]). Low-density urban sprawl undermines agglomeration benefits through longer travel times within a city if jobs fail to disperse in line with housing, higher fiscal costs of supplying infrastructure and public services (Adams and Chapman, 2016[40]; Ahlfeldt et al., 2018[38]), higher transport emissions (though greater use of electric vehicles would reduce this effect) and loss of environmental amenities within and at the borders of urban areas. On the other hand, density can have negative implications for open space preservation, traffic congestion, health and self-reported well‑being (Ahlfeldt et al., 2018[38]). Supporting infrastructure and high quality urban design are important to alleviate negative perceptions of density. For example, in Vancouver density is promoted but views of mountains and water are protected. Public parks and green spaces in urban centres are an essential element supporting quality of life in a compact city; physical or visual access to green spaces, water, or natural light has a surprisingly powerful direct impact on subjective wellbeing (O’Donnell et al., 2014[41]).

Population density in Auckland is higher than in Australian and North American cities with similar populations, but lower than in most European equivalents (Demographia, 2018[42]). NZ cities have low levels of public transport infrastructure and use by developed world standards, with nine out of ten commutes in Auckland by car. Recently completed bus lanes and in-progress rail network expansion are expected to deliver considerable efficiency gains through agglomeration benefits and encouraging more suburban dwellers to commute to higher-paying central business district jobs (Hazledine, Donovan and Mak, 2017[43]). Developing effective urban transport networks is important to connect people in disadvantaged communities and expand opportunities for socio-economic mobility (OECD, 2018[44]). An OECD study is currently underway modelling the potential to decarbonise urban mobility in Auckland through land use and transport policies (Tikoudis, Udsholt and Oueslati, forthcoming[45]).

Strict regulatory containment policies such as explicit density limits, minimum lot and apartment sizes and restrictions on multi-dwelling units impede densification, affordability and innovation. Regulation should be better aligned with prevention of the most important external costs. Specifically, external effects on neighbours would be better managed through clearer rules about overshadowing and the bulk and location of buildings (NZ Productivity Commission, 2015[36]). Concerns about increased rainfall runoff due to lower urban permeability would be better addressed more directly through green space requirements, which could be adjusted as stormwater systems are upgraded. Restricting the development of multi-dwelling units through single-use zoning is particularly costly, as it prevents land use from adapting to social and economic changes. Avoiding single-use zoning has facilitated strong residential construction activity in Japan, where there are generally no restrictions on multi-dwelling units and maximum building heights are determined according to a formula that depends on the distance of a building to the adjacent road (OECD, 2017[46]). Increasing the price of on-street parking to reflect its true social cost would remove the need for minimum parking requirements (OECD, 2018[47]), which increase house prices and rents (Lehe, 2018[48]).

More systematic use of pricing mechanisms to internalise external costs would be a better way to shape development. One-off development contributions are levied to recoup infrastructure investment costs, but do not generally reflect the true cost of infrastructure, particularly the higher cost of servicing greenfield investment at the urban fringe. For example, Auckland Council estimates bulk infrastructure costs of roughly NZD 140 000 per dwelling (USD 100 000) for greenfield areas, which far exceeds development contributions (Auckland Council, 2017[49]). Recently phased-out financial contributions should be re-introduced along with clearer principles on their intended use as an economic instrument to offset environmental costs of new development.

Allowing some orderly expansion of urban boundaries can work in conjunction with removal of barriers to densification to ease housing affordability challenges. Providing the option of development up or out – with cost-reflective charging for access to infrastructure services and policy measures to control environmental effects – allows residents to choose the best solution for their own well-being. The outcomes from this choice can be seen in Auckland, where the majority of the increase in building consents following the Unitary Plan has been for brownfield sites where greater density is now allowed (Auckland Council, 2018[50]). In areas of low density, governments need to focus on suitable transport models such as on-demand services and sharing, and encourage interchanges between different transport modes such as park-and-ride facilities. In Finland, for example, the development of multi-modal travel chains has been enabled through reforms to harmonise legislation and open access to data (Finnish Government, 2018[51]). On-demand shared services and their alignment with other policy tools such as pricing, regulation, land-use and infrastructure design have the potential to replace private car trips and thus reduce emissions, congestion and the need for parking space in Auckland, while providing more equitable access to opportunities. Replacing 20% of Auckland car trips with shared mobility services is estimated to deliver a 15% reduction in total distances driven and carbon dioxide emissions (ITF, 2017[52]). Lack of parking availability, under-pricing of parking and poor local connections have held back the success of park-and-ride in Auckland (Tan, 2018[53]).

Land ownership in New Zealand is fragmented, so failure to aggregate small holdings of land tends to push development out to the urban fringe (NZ Productivity Commission, 2015[36]). The establishment of a national housing and urban development authority (Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities) is a promising initiative that will assist with land amalgamation in specific areas. In addition to taking over Housing New Zealand’s role as a public landlord, Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities will operate in areas with significant redevelopment potential and have the capacity to override planning barriers, plan and build infrastructure, levy charges to cover infrastructure costs and assemble parcels of land for development, including through compulsory acquisition under the Public Works Act. Compulsory acquisition of land for construction of housing is possible in 58% of OECD countries covered by the 2016 Land Use Governance Survey (OECD, 2017[54]) and is valuable as a backstop to avoid the incentive for individual landholders to hold out for above-market compensation. Infrastructure funding issues for local government, as discussed below, are likely to be less of a problem in areas redeveloped by Kāinga Ora, as most costs can be more easily apportioned and passed on to those within the development project area (notwithstanding challenges associated with apportioning costs of upstream bulk infrastructure constraints).

Augmenting infrastructure funding and financing for local government

Councils2 bear the bulk of infrastructure costs, but have limited ability to recoup costs except through development contributions, user charges, or rates charged to residents. Across the OECD, local governments have been found to respond to such fiscal incentives through the types of planning policies implemented, which can create inefficient land use patterns (OECD, 2017[46]). While in theory growth in New Zealand can pay for itself over a period of time, in practice this proposition comes with significant risk for councils and the financial gain rarely eventuates, particularly where some infrastructure is required in advance of development (Morrison Low, 2017[55]). Financing (where the upfront money comes from) and funding (who eventually pays, for example through taxes or user charges) are both fundamental to any solution. Financing problems are currently more binding as key high-growth councils are constrained by contractual requirements to meet Local Government Funding Authority borrowing covenants, as well as their own borrowing covenants. The structure and norms of the local government sector worsens this constraint as councils find it difficult to credibly commit to not fully underwrite any special borrowing arrangements outside of general obligations debt, for example if project-specific revenue bonds were issued and linked to a specific infrastructure project. Funding mechanisms are also critical, however, as existing residents have an incentive to oppose development where they are liable for funding.

The problems that councils face in paying for infrastructure are well recognised and a key focus of the Productivity Commission’s current inquiry into local government funding and financing. Responses to date have not solved the funding and financing issues. The Housing Infrastructure Fund, for example, provides financing for high growth councils to accelerate infrastructure provision, but in the form of loans that count towards council general obligations debt. Crown Infrastructure Partners Limited was created to help enable project financing without any special public powers. However, this model cannot apply more generally when public infrastructure has significant spill-over benefits that cannot be captured without additional public powers to compel levies.

The Urban Growth Agenda recognises the need for more user charging for transport infrastructure. However, its proposals to rebalance risk from councils to the development sector will only support new supply insofar as developers are well-placed to control risks and target charges for recovery of infrastructure costs. This is most likely to be the case in large greenfield developments without substantial ongoing planning or other regulatory risks.

More user charging would be fairer in terms of ‘user pays’ and could also reduce infrastructure spending. Direct charging for road use will lead to more efficient use and also help inform where new roads go. The joint Auckland and central government project “The Congestion Question” is a promising initiative, though implementation of user charging will be challenging and thus needs to proceed prudently through policy trials. The national rule that tolls can only be levied on new roads with feasible untolled alternative routes should be removed to facilitate progress. Volumetric charging for water and wastewater should be introduced more widely and in high growth regions should be based on the full long-run marginal cost of supply – short-run marginal cost pricing achieves greater immediate allocative efficiency, but is not dynamically efficient under expanding demand and encourages over-consumption by failing to signal the cost of incremental investment. Auckland is the only area where volumetric charges are routinely applied for water and wastewater. Even there, volumetric charges do not fully reflect long-run marginal costs, requiring an Infrastructure Growth Charge on new customers, which skews recovery of costs towards new users and is significant enough (over NZD 10 000 per unit) to dissuade development. The problem here is not the existence of development contributions to pay for development-specific infrastructure, but the need to charge an additional fee to make up for low volumetric charges: a new unit would incur an Infrastructure Growth Charge whereas increasing water use by the same volume (on a new garden, for example) would not, despite the same expansion of trunk infrastructure requirements. A positive example is Tauranga City Council’s introduction of water meters and volumetric charges, which significantly reduced demand for water and allowed infrastructure upgrades to be delayed (NZ Productivity Commission, 2017[37]).

Giving councils access to a tax base linked to local economic activity (such as income or goods and services tax) would improve the fiscal dividends they receive from growth. Germany is an example of a devolved planning system where central government grants are linked to local population and tax revenue, which incentivises municipalities to allow growth, contributing to more affordable housing (Evans and Hartwich, 2005[56]).

Councils cannot currently apply targeted rates to just the value “uplift” that occurs following new infrastructure development. This barrier should be removed, though implementing value uplift capture can be challenging and lead to vigorous debate about how much of a value change can be ascribed to government actions. In Australia, value uplift charges intended to recover infrastructure costs have often not been sustainable politically (Australian Productivity Commission, 2014[57]). An alternative way to capture increases in land value associated with infrastructure investment would be to shift the base for council rates to unimproved land value (Figueiredo, forthcoming[58]). While some councils already do this, the majority, including those in each of the five largest cities, base rates on capital values. Shifting the base for rates to land value would also encourage development and density, be less damaging to economic growth, and may even be more progressive and thus equitable (NZ Productivity Commission, 2018[59]). Rates should also be extended to developable central government-owned land to encourage development and increase revenue for councils.

Broadening the range of financing options available to councils would also be beneficial. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) can offer benefits through access to private technology, innovation and experience managing commercial risks, as well as enhanced incentives to deliver projects on time and within budget. However, costs can include hidden contingent liabilities for government, higher transaction costs and contracting difficulties. Assessing risks and determining where to assign them is a complex task that requires substantial capacity in the procuring agency, which is lacking at the local government level. Project-specific infrastructure bonds, through special purpose vehicles or privately-owned vehicles as part of the proposed role for Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities, are a viable option for large projects with external ratings and where longer duration finance is needed (OECD, 2015[60]). However, project-specific bonds may have a higher cost of financing if separated from council general obligations debt. Servicing such debt with revenue from the new properties in a development helps ensure that the beneficiaries pay, but is likely to be more complicated in situations (such as brownfield development) where existing residents also gain. Another means to make financing easier would be to relax the requirements for lending from the Local Government Financing Agency, as recent assessments have not identified serious concerns about the overall level of council debt (NZ Productivity Commission, 2018[59]). The new independent New Zealand Infrastructure Commission, Te Waihanga, announced by the national government should be well-placed to support councils in broadening the range of financing sources they draw from.

Reforming the slow and prescriptive building consenting process

As in several other OECD countries including the United Kingdom and Canada, New Zealand uses a system of joint and several liability for building, whereby two or more parties liable for the same loss or damage because of separate wrongful acts can each be held up to 100% liable for the loss. The potential negative consequences were evident during the leaky homes crisis, where councils, often the “last person standing”, were held responsible for an average of 45% of adjudicated costs despite their share of responsibility being around half that level. Overall costs to councils between 1992 and 2020 have been estimated at several billion NZ dollars (Price Waterhouse Coopers, 2009[61]). Between 2008 and 2018, building consent authorities are estimated to have faced total payments of NZD 1.1 billion from residential building defect cases, with their burden in analysed cases increased by 170% due to the inability to collect shares from other liable parties (Sapere, 2018[62]). The Law Commission (2014[63]) recommended against moving to proportionate liability due to the risk for consumers of uncollectable shares as well as the difficulty of establishing the appropriate share of responsibility for all parties. However, this analysis failed to fully consider the role of joint and several liability in causing building consent authorities to be excessively risk averse, as highlighted by the NZ Productivity Commission (2012[20]) and more recently by Auckland Council (2018[64]; 2017[65]). Proportionate liability would improve incentives for consenting authorities by better aligning their liability with their responsibility and desired behaviour. Consumers’ interests can be protected through other means, such as a strengthened building warranty or insurance scheme.

Left to the market, building insurance needed to complement a system of proportionate liability suffers from adverse selection due to insurers’ incomplete information. A number of OECD jurisdictions, including Belgium, France and Israel, have made building insurance mandatory to cover the risk of defects up to 10 years after completion. The Australian state of Victoria, which combines proportionate liability with mandatory insurance for work exceeding AUD 16 000, provides a useful template but also illustrates the importance of monitoring building insurance markets: the market was served by five competing private sector insurers until all but one announced they would cease issuing building insurance and a government statutory authority was forced to step in. While a competitive market for building insurance is preferable, given the small size of the market and inherent risks associated with long-tail liability there may be a need for government-backed insurance that satisfies competitive neutrality. The other valuable lesson is the need to streamline agency responsibility for building insurance (Parliament of Victoria, 2010[66]).

Individual building consent authorities must be satisfied on reasonable grounds that the proposed building work will comply with the building code and have a preference for products and systems known to meet the code. A conservative approach to new products may hamper innovation (Auckland Council, 2017[65]). Building consenting authorities will face further challenges with more construction of pre-fabricated housing, which is one potential technological solution to New Zealand’s poor construction industry productivity. Proposed reforms have the potential to increase efficiency through mandatory information requirements for building materials and a regulatory framework for modern methods of construction, including pre-fabrication. If these steps are insufficient, authorities could consider a centralised building materials register that leverages approvals in countries with similar climates and earthquake risks (such as Japan or western Canada and the United States), or reallocating building consenting to a central authority.

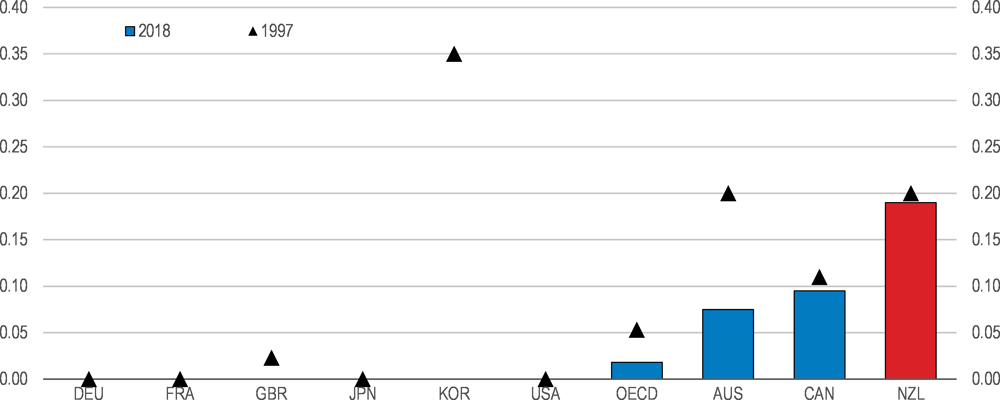

Increasing productivity in the construction industry

Productivity in the NZ construction industry is low relative to comparable countries, pushing up construction costs. A 10% decrease in construction costs is estimated to reduce long-run house prices by around 8% (Grimes et al., 2013[67]), though the pass-through of construction costs into house prices is lower when supply is inelastic (Evans and Guthrie, 2012[68]). If and when implementation of the Urban Growth Agenda increases the supply of developable land, construction industry efficiency will become even more important. Low productivity in construction largely stems from insufficient competition in specific markets, poor management skills and sluggish adoption of new technology (OECD, 2017[30]). High barriers to foreign direct investment (Figure 3.7) combine with remoteness and small market size to dissuade entry of foreign firms. Entry of foreign firms could promote competition, open up access to global supply chains, as well as bring in much-needed technological, skills and managerial quality transfers. The 2017 Survey recommended narrowing screening of foreign investment while continuing to reduce compliance costs and improve predictability, a Commerce Commission market study of the construction industry, and (as subsequently implemented) extending suspension of anti-dumping actions on residential building materials. Since the release of the 2017 Survey, the government has launched its Skills Action Plan, which aims to increase productivity through better skill development and matching. The Construction Sector Accord signed in April 2019 aims to strengthen the partnership between government and the industry through measures such as better risk management and allocation, better procurement practices and pipeline management, and improved building regulatory systems and consenting.

A ban on housing purchases by foreign residents passed in August 2018 aims to improve housing affordability, but will also have implications for construction of new housing. Effects on affordability are likely to be small, as only around 3% of home sales are to foreign buyers (Statistics NZ, 2018[27]). The ban risks holding back foreign direct investment and thus construction industry productivity. Compliance costs and uncertainty are now higher for foreign developers (excluding those from Australia and Singapore), as they are required to divest after completion of any development of less than 20 units.

Figure 3.7. Restrictions on foreign direct investment in construction are substantial

Index from 0 (open) to 1 (closed)

Note: The FDI restrictiveness index is zero for Germany, France, Japan and the United States in 1997 and 2018.

Source: OECD, FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index database.

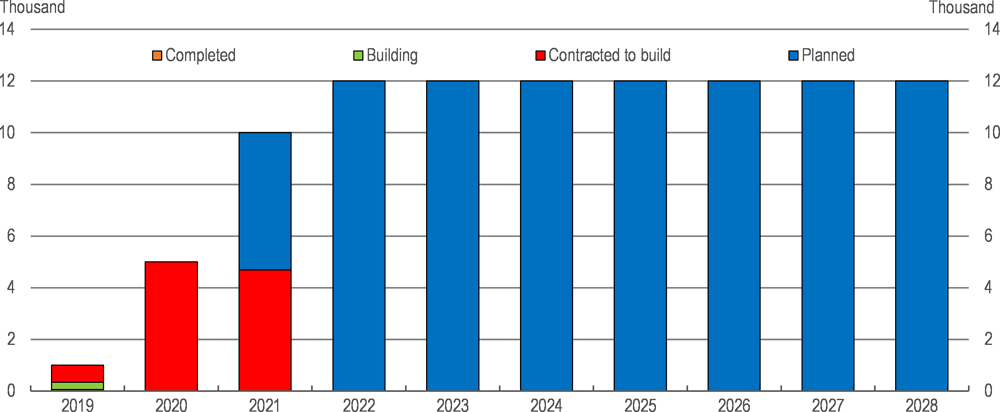

Better targeting KiwiBuild

The government is taking a more active role in increasing housing supply through Kiwibuild (Box 3.3). Once the programme ramps up, the number of affordable new dwellings is planned to exceed one third of the total dwellings consented nationally in recent years. Whether KiwiBuild is successful in increasing supply will depend on whether it is able to deliver additional dwellings that private markets would otherwise not have delivered, by overcoming planning, infrastructure and construction industry constraints or delivering higher density development. Given the current lack of spare capacity in the construction industry, particularly in Auckland, some crowding out of private activity is inevitable: the Reserve Bank has estimated that half to three quarters of the KiwiBuild contribution to residential investment until the end of 2022 will be offset by crowding out of private investment (RBNZ, 2019[69]). The programme also has the potential to provide benefits from smoothing historically highly variable construction activity across the economic cycle, which contributes to low industry productivity, but this will only become apparent during a downturn.

By focusing solely on home ownership, KiwiBuild is not well-directed at enhancing well-being. As noted above, the links between well-being and housing ownership are weak, and those in greatest need are renters without sufficient income or wealth to buy their own house. The annual income limits for buyers of KiwiBuild homes are NZD 120 000 for singles and NZD 180 000 for couples (or other multi-party buyers), meaning that only the top 8% of potential first home buyers do not qualify (Twyford, 2018[70]). The small number of houses supplied to date have been oversubscribed, so a ballot system was used initially to ration demand; one of the first ballot winners estimated a windfall capital gain of NZD 70 000 (Hooton, 2018[71]). Irrespective of the exact figure, the need for a ballot means that there is a wealth transfer from the government to relatively well-off home buyers who are (with some constraints) subsequently allowed to sell the home at its market price.

Box 3.3. The KiwiBuild Programme

KiwiBuild is a recent NZD 2 billion programme that aims to deliver 100 000 modestly priced homes over 10 years (Figure 3.8). The objectives are to increase supply of new housing in areas with shortages, increase home ownership and catalyse change in the residential construction sector by providing the sector with confidence to invest in skills and workforce and through initiatives such as increased use of prefabrication and modular housing. The homes, half of which are to be in Auckland, are aimed at first-home buyers and will be delivered at affordable prices using four main mechanisms.

Government underwriting or purchasing of new homes off the plans that the private sector or others are leading. Four-fifths of new KiwiBuild homes in 2019 and half in 2020 are planned for delivery this way.

Government acquisition of suitable vacant or under-utilised Crown and private land and sale to developers, subject to conditions around the share of affordable dwellings.

Undertaking major urban redevelopment projects, via Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities, in partnership with iwi (indigenous communities), councils and the private sector.

Identifying and leveraging opportunities through existing government-led housing initiatives, such as those being undertaken by Housing New Zealand.

Initiatives to streamline planning and consenting processes through the Urban Growth Agenda and Kāinga Ora will support delivery of KiwiBuild homes. Accommodation Supplement payments (discussed below) provide a demand-side incentive for the delivery of affordable housing once supply can more easily respond.

Figure 3.8. KiwiBuild original planned delivery and progress to date (dwellings)

Note: Based on original planned delivery profile – interim targets have since been dropped. Progress as of February 2019. All dwellings for which building work is underway are assumed to be delivered in 2018-19. Enough contracted dwellings are assumed to be delivered to meet the 2018-19 target and remaining contracted dwellings delivered in 2019-20 and 2020-21. Years shown correspond to the end of fiscal years, which run from 1 July to 30 June.

Source: Ministry of Housing and Urban Development.

The government is not well-placed to take on the allocation role and holding risks it has assumed under the main KiwiBuild delivery mechanism used to date. As described above, constraints around planning, consents and infrastructure have held back delivery of new housing supply. These are areas where market failures are pervasive and government involvement is critical. Allocating scarce government housing expertise elsewhere entails large opportunity costs. Once built, markets are much better placed to allocate housing to buyers; shortages have arisen due to a lack of supply, rather than allocation problems. By underwriting or purchasing new homes, government is taking on substantial risk that could blow out the fiscal cost of KiwiBuild if housing markets were to fall or if the developments chosen are not wanted. Developers are far better placed to manage market risks and determine which developments are likely to be successful.

Other OECD countries have policy measures to promote delivery of affordable housing that do not involve the same fiscal risks or hands-on allocation role. Canada’s National Housing Co-Investment Fund provides low-cost loans and/or financial contributions to support and develop mixed-income, mixed-tenure, mixed-use affordable housing. This scheme is squarely targeted at delivery of affordable rental housing, with a 20 year commitment required to keep rents for a minimum of 30% of units below 80% of the Median Market Rental rate (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, 2018[72]). France operates a highly diversified and complex system of subsidies and allowances to incentivise developers to deliver housing for both affordable rental and home ownership (Calavita and Mallach, 2010[73]). In Germany, the supply of affordable housing is increased through public subsidies in conjunction with inclusionary zoning, with rental housing generally targeted (Granath Hansson, 2017[74]). Austria provides direct construction subsidies and has been successful in maintaining housing affordability, although the high share of residential construction eligible for subsidies has impeded targeting (Scanlon, Whitehead and Fernandez Arrigoitia, 2014[75]).

KiwiBuild should be refocused on supplying land by aggregating fragmented land holdings and de-risking development sites to make it feasible for developers to step in. Examples of risks that governments can be better placed to manage than developers include using compulsory acquisition powers (at market rates) under the Public Works Act, restoring contaminated soil and upgrading or assessing uncertain underground infrastructure assets. Subsidies to private and not-for-profit developers should be used to incentivise delivery of affordable housing that would otherwise be under-provided. Priority should be given to financial support for the delivery of affordable rental housing, with requirements for dwellings to be leased at a specified discount to market rents. The precise approach under KiwiBuild delivery mechanisms other than “buying off the plans” is not yet clear, but the planned shift towards other delivery mechanisms offers an opportunity to refocus the programme in this way.

Avoiding policy measures that unnecessarily fuel demand

Tax settings favour investment in housing

The non-taxation of imputed rent3 on owner-occupied housing and capital gains biases household portfolios towards housing and has contributed to rising house prices. Housing investors can offset interest expenses against rents and other income sources, although offsetting against other income sources would be disallowed under government proposals to ringfence rental losses. Combined with the absence of capital gains tax on rental properties held for five years or more (recently increased from two years) unless there was an intention to make a capital gain, this inflates property valuation by over 50% for an investor with an 80% mortgage (OECD, 2011[13]). Owner occupiers benefit less when they have a large mortgage as they are unable to deduct mortgage expenses, but property valuation for an unmortgaged owner-occupier is inflated by more than 100% due to the non-taxation of imputed rent. New Zealand is unusual among OECD countries in having no comprehensive capital gains tax, although most countries exclude the primary residence. Because nominal interest income and dividends are taxed, the absence of a capital gains tax raises the relative returns to assets with good prospects for price appreciation, such as housing, farm land and, to a lesser extent given high dividend payout rates and the thin domestic market, equities.

The house price effects of introducing a comprehensive capital gains tax would be curtailed if it did not apply to primary residences, as in the Tax Working Group (2019[76]) proposal. Lower post-tax returns for investors would contribute to lower house prices and higher rents as investors pass through costs to renters. (The proposed ringfencing of rental losses can be expected to have a similar effect, though a smaller number of landlords would be directly affected.) Demand from potential owner occupiers would increase due to higher rents and lower returns on alternative investments now subject to capital gains taxation, such as equities. The cooling effect on house prices is thus likely to be small.

Some incremental changes to taxation of housing are warranted. Restoring building depreciation for multi-unit residential developments would increase the supply of this type of housing and support greater densification in urban areas. However, this would also exacerbate under-taxation of housing, so the case would be stronger if a capital gains tax was introduced. Another issue is the incentive for landholders on city fringes to withhold land from development for up to 10 years to avoid tax on sale where at least 20% of the gain can be attributed to zoning or other specified changes (Tax Working Group, 2018[77]). This could be resolved by removing this tax and relying on land taxes (as discussed above in relation to council rates) or targeted rates as less distortionary means of value capture. The government has identified repealing the ten-year rule as a high priority and has asked the Productivity Commission to consider a tax on vacant residential land as part of its inquiry into local government funding and financing.

Eliminating poorly targeted home ownership subsidies

Further support is provided through subsidies and government-backed access to loans with small deposits (Table 3.3). Financial assistance for home ownership is middling among OECD countries (OECD, 2017[17]), excluding the cost of KiwiSaver first-home withdrawal for which data are unavailable. Home ownership subsidy schemes seek to increase home ownership by assisting low- and moderate-income households to purchase their first home. Tenure-neutral objectives, such as housing affordability and quality, would be more useful. As noted above, well-being benefits of home ownership are much less certain than from access to quality affordable housing more generally. The main economic argument for subsidising owner occupation is that homeownership may give rise to positive spillovers for society, such as wealth accumulation, better (external) property maintenance, community engagement and voting behaviour. On all of these issues there is competing evidence and establishing causality is difficult (Andrews and Caldera Sánchez, 2011[78]).

Furthermore, New Zealand’s programmes to facilitate the transition to home ownership have generally failed to help large numbers of households purchase a first home (NZ Productivity Commission, 2012[20]). Subsidies can be self-defeating by pushing up the price of houses commonly purchased by first-home buyers, particularly where the supply response is weak. Associated wealth transfers have adverse consequences for distribution and thereby well-being.

The government should rationalise support for first-home buyers, as multiple policy tools seek to meet broadly the same objective. The KiwiSaver HomeStart Grant has some valuable features: it is means tested and available to people who have previously owned a home but are in a similar financial situation to a first-home buyer. However, its targeting does not necessarily align with locations of greatest housing need, as house price caps restrict support in areas with high housing costs. Around one in ten homes bought with a HomeStart subsidy were in Auckland in 2016, while one third of the population and half of people in crowded households lived there (Housing NZ, 2018[79]).

As noted in the 2011 Survey, the option for KiwiSaver members to withdraw balances to purchase a first home undermines incentives to diversify household portfolios away from housing and is poorly targeted, as those with higher incomes have higher balances. Welcome Home Loans work against macro-prudential controls (from which they are exempted) by allowing loans with high loan-to-value ratios, pushing risk back onto the government and adding to the overall fiscal cost. The benefits for lower-income households, who are at greater risk of default anyway, are questionable in a context where prices have been rising fast for some time and could fall sharply. Administrative costs are likely to be high relative to the benefits, given weak take-up.

Shared equity arrangements can increase access to home ownership for those with lower incomes, but also transfer risk away from those best able to control it (homebuyers) and carry greater complexity and administrative cost than HomeStart Grants. Consideration should be given to whether funding would be better directed towards improving health, education and distributional outcomes through supporting the broader housing needs of low-income households, in particular through more support for private and social rentals.

Table 3.3. Government subsidies to assist with home ownership

|

Programme (year of commencement) |

Support available |

Means testing |

Take-up |

|---|---|---|---|

|

KiwiSaver HomeStart Grant (2007) |

NZD 3 000 to 5 000 depending on duration of contributions (NZD 6 000 to 10 000 for purchase of a new home) |

Income <85 000 or <130 000 for couples Regionally-specific house price cap (400 000 to 600 000 for existing houses) Asset test for previous home owners |

16 712 in 2016‑17 |

|

KiwiSaver first-home withdrawal (2007) |

Can withdraw member and employer contributions, returns on investment and member tax credits, subject to keeping a minimum balance of NZD 1 000 |

Asset test for previous property owners |

33 000 in 2016‑17 |

|

Welcome Home Loan (2003) |

Smaller deposit requirement (10%), with risk for lender underwritten by Housing NZ |

Income <85 000 or <130 000 for couples Regionally-specific house price cap (400 000 to 600 000 for existing houses) Asset test for previous home owners |

1 381 in 2016‑17 |

|

Kainga Whenua (2010) |

Lenders mortgage insurance to help Māori to achieve home ownership on multiple-owned land |

No – income caps removed in 2013 – although only available to people that have no other access to finance |

17 since introduced in 2010 |

Source: Housing New Zealand, Ways we can help you to own a home, https://www.hnzc.co.nz/ways-we-can-help-you-to-own-a-home/; Housing New Zealand, Annual Report 2016/17, https://www.hnzc.co.nz/assets/ Publications/Corporate/Annual-report/HNZ16117-Annual-Report-2017.pdf; KiwiSaver, KiwiSaver Funds Withdrawn, https://www.kiwisaver.govt.nz/statistics/annual/withdrawals/.

Supporting low-income renters

Renters on average have lower incomes than owner-occupiers and spend a greater share of their income on housing (Section 3.1.2). Rental quality and security of tenure is low, with 12 month tenancies most common and an average rental duration of 2 years and 3 months (Johnson, Howden-Chapman and Eaqub, 2018[80]). This is only slightly lower than the average rental duration in England, but far below an average 11 years in Germany (IPPR, 2018[81]). By comparison, 70% of owner‑occupiers in New Zealand have been in their current property for five years or more (Statistics NZ, 2015[82]), while tenants are expected to stay an average of 17 more years in social housing (MSD, 2017[83]). Although renters might reasonably be expected to move more often than owners (with advantages for labour mobility), duration of tenure has been found to be associated with better outcomes, notably for children (Galster et al., 2007[84]). Older renters are particularly vulnerable to tenure insecurity, may need modifications to meet their needs and have a greater need for warm, comfortable and functional housing more generally; the number of older renters is set to rise with ageing of the population and decreasing home ownership rates (James and Saville-Smith, 2018[85]). Tenants would be better served by a rental market in which they have greater choice over if and when they move house.

Tenant-landlord regulation should be improved, in particular by increasing security of tenure and thus social and family stability. New Zealand ranks equal fifth lowest among 31 OECD countries for the restrictiveness of rental control and tenure security requirements (Kholodilin, 2018[86]). Proposals currently under consultation would go some way to improving security of tenure through limiting the frequency of rent increases, extending notice periods and tightening the conditions around which landlords can end a tenancy (MBIE, 2018[87]). In Germany and the Netherlands, security of tenure is strong for tenants who meet their contractual obligations (contracts are typically open-ended and sale of the dwelling is not a valid reason for termination) but this has not been a considerable disincentive to rental investment, as it has fostered long-term demand for renting and stable incomes for landlords (de Boer and Bitetti, 2014[88]).

One missing component is some restriction on rent increases in line with market rates, for example, as measured by local residential bond tenancy data. This would avoid landlords increasing rents to capture the benefits to an established tenant of remaining in the same dwelling and the use of rent increases as a means of eviction. However, restrictions should not serve to push rents below market rates, as such forms of rent control are detrimental to residential mobility and do not deliver long-term lower rents as they impede new supply (Andrews, Caldera Sánchez and Johansson, 2011[89]). While rent that substantially exceeds market rates is already disallowed, this requires comparison across properties, controlling for differences such as location, size, condition and facilities. Restricting rent increases for sitting tenants would be simpler and more effective. Germany has fostered a successful private rental sector through leaving initial rents effectively unregulated and tying subsequent increases to local reference rents, with greater increases permitted in proportion to any renovation expenditure (de Boer and Bitetti, 2014[88]).

The government has recently announced healthy homes standards for rental homes, which introduce minimum requirements for insulation, heating, ventilation, draught stopping, moisture ingress and drainage. Policy measures to increase minimum standards for rental homes should apply the regulatory principles developed by the NZ Productivity Commission (2014[90]), which set out when regulation should be principles-based, outcomes-based, prescriptive or process-based. Recent policy changes should be evaluated and adjusted in due course, as improving rental quality remains critical. Relevant to the natural capital component of well-being, substantial improvements in the energy efficiency of buildings (new and existing) are likely to be needed to get emissions on to a trajectory consistent with Paris Agreement targets (Climate Action Tracker, 2016[91]).

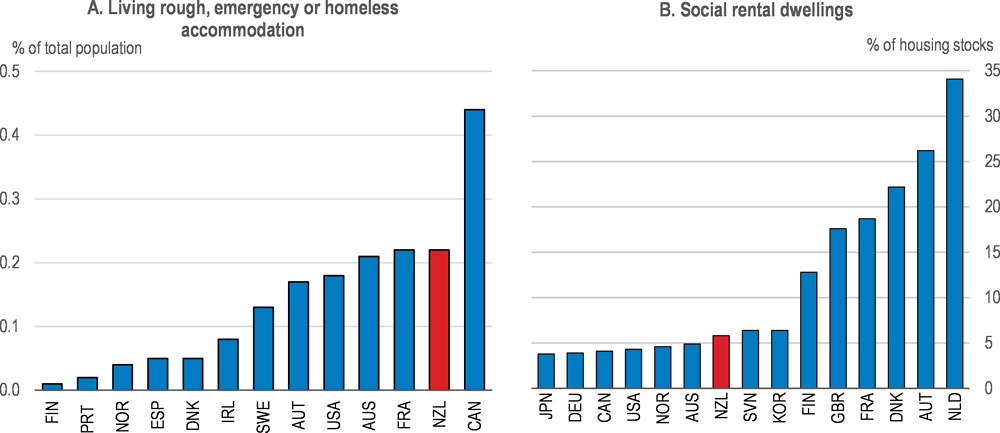

Increasing the supply of social housing

Social housing supply is low by international comparison and there are poor outcomes for at-risk groups, including overcrowding, low quality housing and high homelessness (though international comparability here is highly problematic – Figure 3.9). Homelessness has increased during the past decade, as in most OECD countries, although the lack of consistent data for New Zealand makes it difficult to identify trends in a timely fashion. The share of homeless people increased from 0.8% in 2006 to 1.0% in 2013 with an increase in households temporarily sharing with others (Amore, 2016[19]). Drivers of homelessness are many and varied, but deteriorating access to affordable housing has been a contributing factor (Cross-Party Inquiry on Homelessness, 2016[92]).

The government-owned Housing New Zealand Corporation (Housing NZ) owns and manages the majority of social housing dwellings (Table 3.4). This role will be taken over by Kāinga Ora, once established. Unaffordability of private rentals has increased pressure on social housing, with the waiting list more than doubling to 10 700 in the two years to December 2018 (MSD, 2018[93]). Over three quarters of those on the waiting list have been assessed at the highest level of housing need. Social housing cannot remedy the overall affordability problems but plays an important role at the bottom end of the market by providing non-discriminatory access, security of tenure and targeting for those suffering multiple or severe disadvantage. Budget 2019 included NZD 197 million to strengthen the Housing First programme and fund an additional 1044 places. Similar programmes in US cities have increased residential stability, with additional gains in health and well-being.

Figure 3.9. Homelessness is high and social housing stocks are low

2015 or latest year available

Note: Definitions of homelessness and the methodology for measuring it vary by country. New Zealand’s numbers are based on the census, whereas many other countries use surveys of relevant social support agencies, which are less likely to identify homeless people. Data in Panel A exclude people living in institutions, in non-conventional dwellings or temporarily sharing with another household due to lack of suitable alternatives, which are included in the total homeless population for some countries. New Zealand has a relatively large proportion of people temporarily sharing with another household, but in part this reflects the census approach and a broader definition to that used in other countries. For example, Australia applies stricter rent and income thresholds for those sharing temporarily to be considered homeless. For details, see https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC3-1-Homeless-population.pdf.

Source: OECD, Affordable Housing database, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm and national sources underlying the database.

Table 3.4. NZ social housing stock, number of dwellings 2017

|

Housing NZ |

Councils |

NGOs and others |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Receiving income-related rent subsidies |

58 500 |

0 |

4 800 |

63 300 |

|

Not receiving income-related rent subsidies |

4 400 |

7 700 |

7 900 |

15 300 |

|

Total social housing |

62 900 |

7 700 |

12 700 |

83 300 |

Source: A. Johnson et al. (2018), A Stocktake of New Zealand’s Housing.

Increases in the supply of social housing beyond those underway are necessary. Placement in social housing can improve well-being through marked improvements in health (Baker, Zhang and Howden-Chapman, 2010[94]), a lower number of remand and prison sentences, and increases in children’s access to education (Social Investment Unit, 2017[95]). Housing conditions generally improve for people placed into social housing in New Zealand (though feelings of safety deteriorate), with the well-being benefit of increased life satisfaction potentially exceeding the cost of provision (Social Investment Agency, 2018[8]). While the government plans to expand social housing by 6400 units over four years, this will be insufficient to meet current demand from those with highest need on the waiting list. Redevelopment at greater density and with a broader mix of housing types as in the Tamaki Regeneration offers promise as a means to achieve densification while reducing social segregation. To ensure that redevelopment responds to citizens’ needs, they should be systematically surveyed at the outset of any project.

Further entry of community housing providers should be encouraged through allowing competition with Housing NZ on a level playing field when developing new supply. The community housing sector, comprising iwi and non-governmental organisations, is small and fragmented but has had some successes such as the Waimahia housing development in South Auckland. More community housing would add to choice, offer opportunities for tenants to benefit from their own efforts by eventually purchasing their dwelling and can attract additional resources into housing, for example through private donations and co-operative funds. However, it may be challenging for community housing suppliers to develop sufficient scale in a country with low population and wide geographic spread. Rather than transfer stock from Housing NZ, which does not deliver any net increase in supply and undermines its scale and scope, the government should (as since 2014 for Auckland and since 2018 elsewhere) continue to allow community housing providers to access income-related rent subsidies on the same basis as Housing NZ. Capital grants and favourable loans, which can help community housing providers overcome financing difficulties, are used in a number of countries that have been successful in delivering social housing through non-government organisations, such as Austria and France, but there has been a trend away from such support in many other OECD countries. The development of a long-term strategy for social housing and clearer expectations of quality, quantity, and availability as recommended by the Controller and Auditor General (2017[96]), would provide greater investment certainty for community housing providers.

Efficient and well-targeted allocation of social housing is essential. In general, targeting is good in New Zealand. While many “high-risk” applicants on the waiting list are likely to have greater needs than a large proportion of those already in social housing, wait times are short at a median 77 days. Regular tenancy reviews have contributed by helping ensure that those whose circumstances have improved sufficiently have moved to other forms of tenure. The government has recently broadened the list of exemptions from tenancy review to exempt all tenants where they or their partner have children aged 18 or under in their care or are themselves aged 65 or over; 81% of social housing tenants are now exempt. This broadening does not appear to be justified by the outcomes of those who have recently moved out of social housing following tenancy review, 89% of whom no longer received any accommodation support after 12 months and only 3% of whom subsequently returned to social housing (Twyford, 2018[97]).

Housing NZ’s independence and funding based on the gap between income-based and market rents provides transparency about the annual costs to taxpayers. While Housing NZ and the Ministry of Social Development have strengthened their approaches to sharing information, they still need to work more closely together (Controller and Auditor-General, 2017[96]), for example with regard to efficient provision of broader social services to social housing tenants. As the Treasury has noted, financing new social housing out of normal Crown debt rather than independent borrowing by Housing NZ would reduce borrowing costs, strengthen fiscal control and be more appropriate given the absence of genuine financial risk transfer. However, Housing NZ would need to retain enough certainty around financing flows to support investment. As recommended in the 2011 Survey, Housing NZ could improve long-term financial viability as well as efficiency incentives by removing water rate subsidies for tenants paying market rents.

The role of Accommodation Supplement payments

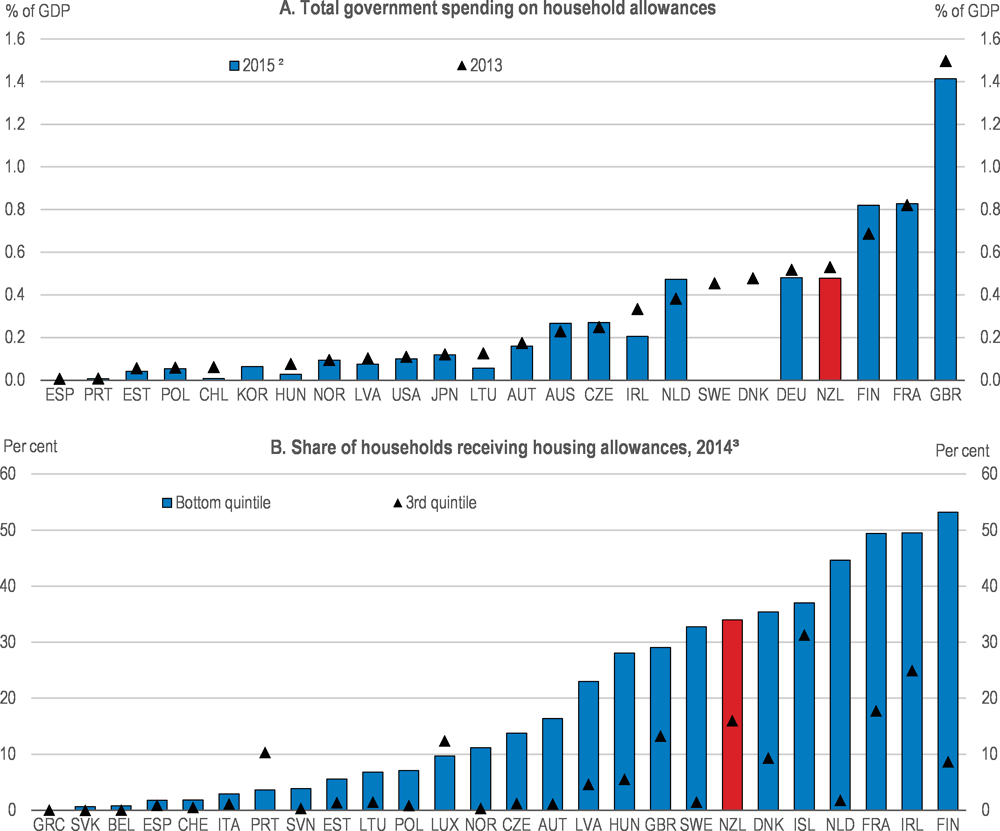

New Zealand spends a relatively large share of GDP on housing allowances through the Accommodation Supplement (AS), which is available to eligible renters and own-occupiers (Table 3.5;Figure 3.10, panel A). Payments increased further from 1 April 2018, and are projected to exceed 0.5% of GDP in the 2018-19 fiscal year. This was the first increase in AS payment rates since 2007. A relatively large share of the population receives AS payments, particularly among the third quintile (panel B). This is due to high maximum payment rates as well as relatively gradually phasing out of payments at a rate of 25 cents in the dollar above an income threshold. Families with incomes of up to NZD 96 000 can still be eligible to receive some AS payments.

Table 3.5.Rental assistance payments in New Zealand

|

Available to |

Means tested |

Number of recipients, June 2018 quarter |

Annual fiscal cost, 2018 forecast (NZD millions) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Income-related rent subsidy |

Social housing tenants paying below market rents |

Yes |

64 312 households |

889 |

|

Accommodation Supplement |

Renters and owner-occupiers not in social housing |

Yes |

284 686 |

1 208 |

|

Temporary Additional Support |

Those needing assistance to cover essential living costs for up to 13 weeks |

Yes |

58 763 |

212¹ |

|

Transitional Housing |

People in need of warm, dry and safe short-term accommodation |

Yes |

2 341 places |

70.8² |

|

Emergency Housing Special Needs Grant |

Individuals and families unable to access transitional housing places |

Yes |

10 879 |

34.0 |