Compensation for environmental damage is quite unusual among OECD members. It typically arises from lawsuits following unanticipated, severe and exceptional pollution events. Liability is understood as an obligation for the responsible party to bear the costs of restoring the environment. The policy objective is to restore the environment, which is reflected in specific requirements imposed by the law on liable parties. The objective is not to punish the operator that caused the damage (OECD, 2012[1]).

In other words, within the OECD, monetary pollution damages are not meant to punish an operator for breaching an emission limit or causing emissions not expressly authorised in a permit (OECD, 2012[1]). Rather, monetary pollution damages are intended to be restorative. Violation of laws (such as emission limit rules) is the domain of administrative penalties and criminal law.

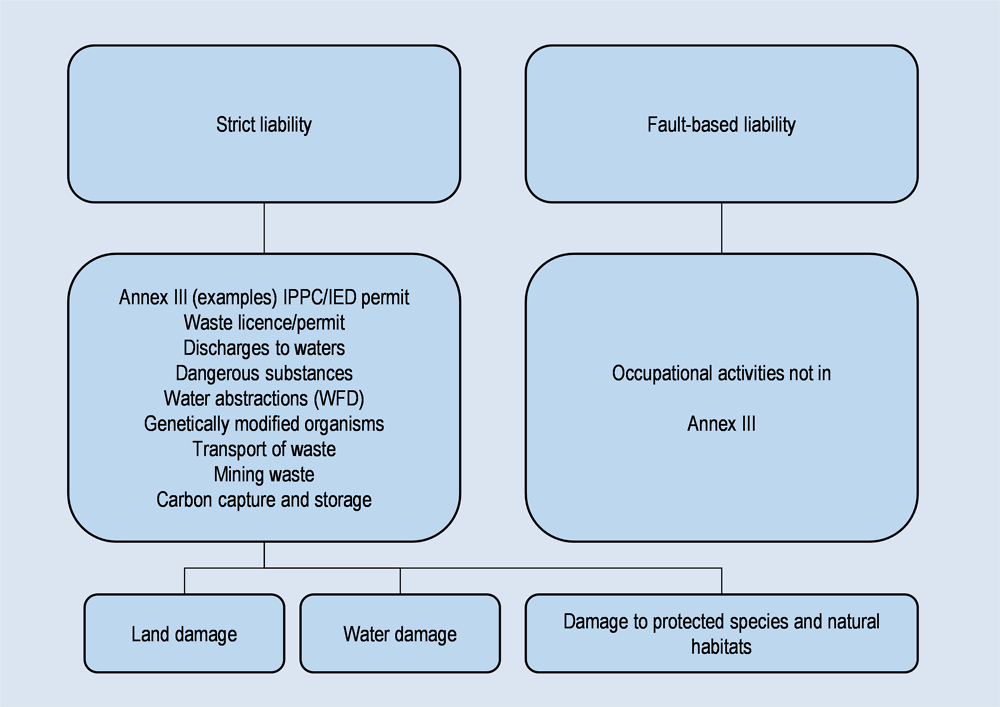

In determining the features of a liability regime underpinning monetary damages, legislators must choose between a strict liability and a fault-based standard.

A strict liability standard forces the operator to consider both the level of care and the nature and level of activity. It creates additional incentives for good corporate environmental management, at least with respect to hazardous activities (OECD, 2012[1]).

A fault-based standard provides appropriate incentives to potential responsible parties. However, these incentives relate only to the level of care (the diligence in performing a given activity) and not to the nature and level of polluting activity (OECD, 2012[1]). Some European countries (e.g. Italy and Poland) historically used fault-based liability. However, they changed their systems to comply with the Environmental Liability Directive (ELD) (OECD, 2012[1]).

Strict environmental liability was first applied in the United States and gained ground in other OECD member countries. The EU ELD imposes the policy on operators engaged in dangerous activities listed in Annex III of the directive. ELD Annex III defines dangerous activities as those subject to an integrated permit, a water abstraction, wastewater discharge or a waste management permit, or a licence for handling dangerous substances and waste. However, a strict liability regime can be weakened by different mitigating factors. The ELD states that operators can, subject to national legislation, invoke two defences. The “permit defence” argues the harmful activity was legally permitted or licensed, and that the operator can prove compliance with all permit/licence conditions. The “state of the art defence” can be used to avoid liability. It aims to prove the harmful activity was not considered likely to cause the damage according to the state of contemporary scientific and technical knowledge.

The party responsible for the damage usually conducts remediation. This is done under an administrative or court order, in accordance with a specific clean-up project. In a public health or environmental emergency, public authorities can proceed directly with remediation. Afterwards, they can recover remediation costs from the liable parties (OECD, 2012[1]).

Importantly, air pollution is not typically a basis for environmental damage in the OECD. Cases for damages to land and water for air emissions are rare. The environmental damages laws of OECD member countries thus tend not to be used for air pollution. The air cannot be remediated, and it is difficult to relate industrial air emissions to the harm of land, water or human health. As noted earlier, OECD jurisdictions impose a penalty, not monetary damages, on a resource user for exceeding a limit in a permit due to its own fault.

In Canada or Norway, cases in which a company was subjected to damages to land or water caused by emissions into the air could not be identified.

In the United States, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) includes air in its definition of natural resources damages. However, interviews with senior officials at the enforcing authority indicate that air pollution, while not expressly excluded, is clearly “outside the ambit” of natural resources damages under CERCLA and the Oil Production Act (OPA).2

In the European Union, air pollution is not, strictly speaking, a subject of damages liability as defined by the ELD. However, emissions to air that cause “environmental damage” can still have legal consequences. For example, if air emissions damage “land”, then the operator will be liable for the costs of remediation/restoration of the land. However, a causal link has to be established in court.

The ELD establishes an EU-wide common framework of environmental liability to prevent and remedy specific types of environmental damages (see Figure 4.1). The ELD covers three areas: i) “damage to protected species and natural habitats”; ii) “water damage”; and iii) “land damage.” The term damage pervades all three categories. It is defined as a measurable adverse change in a natural resource or measurable impairment of a natural resource, which may occur directly or indirectly. Measurability is, therefore, a central determinant as to whether damage (as a matter of strict legal definition) has been caused. Scientific assessment will be required to determine if the relevant threshold has been met (Fogleman, 2006[4]).

Air is absent from the definition of “environmental damage” under art 2(1) of the ELD. The European Commission has been asked to reconsider this absence in light of the harm caused by air pollution to human health and the environment (European Parliament, 2017[5]). The case of Túrkevei Tejtermelő Kft. v Országos Környezetvédelmi és Természetvédelmi Főfelügyelőség confirmed that “air pollution does not in itself constitute environmental damage covered by Directive 2004/35” (European Court of Justice, 2017[6]). Through analogy, flaring in excess of the limits of a permit, in itself, would not fall with the ELD’s definition of environmental damage.

However, recital four of the ELD is particularly pertinent. It asserts that environmental damage, “also includes damage caused by airborne elements as far as they cause damage to water, land or protected species or natural habitats.” Thus, the framework of environmental liability to be implemented by member states is relevant where water, land, protected species or natural habitats are damaged by emissions to air from, for instance, a flaring stack.

The competent authority has to present evidence that air pollution had caused such damage before it can consider making the relevant operator take remedial measures. Where this can be done, the pollution would come within the scope of the ELD. If not, relevant national law rather than the ELD would apply.

It may be more difficult to invoke the ELD in circumstances where the pollution is of a widespread, diffuse character. Diffuse pollution is generally understood to encompass, “[p]ollution from widespread activities with no one discrete source, e.g. acid rain”.

Diffuse emissions to air can occur from various scattered sources such as road transport, shipping, aviation, domestic heating, agriculture and small business. While pollution from individual diffuse sources may not be of particular concern, the combination of diffuse sources of pollution can have an environmental impact.

The ELD only applies to damage caused by pollution of a diffuse kind where it is possible to establish a causal link between the damage and the activities of individual operators. There is important case law from the Court of Justice of the European Union, which helps competent authorities to establish that link.