This chapter evaluates Colombia’s progress in identifying and assessing natural hazards and disaster risk across its territory, as well as the consideration of interconnected risks. The chapter reviews the openness and accessibility of disaster risk information, which includes the mechanisms for sharing risk information across governmental and non-governmental stakeholders. Finally, the chapter looks at whether the available information on risks is effectively used to inform disaster risk management decisions.

Risk Governance Scan of Colombia

Chapter 4. Disaster risk identification and assessment in Colombia

Abstract

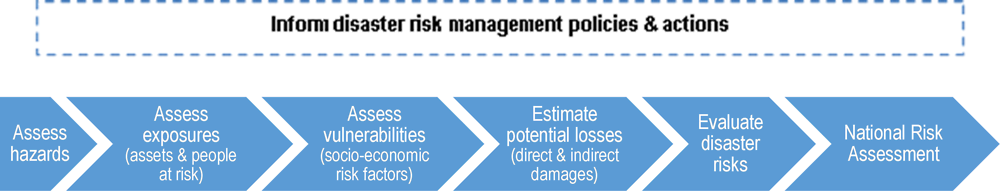

All aspects of decision making in disaster risk management depend on the availability and quality of local hazard and disaster risk information. Hazard maps identify geographic areas potentially affected by adverse events. Risk maps tie the hazard information in with data on socio-economic assets that are exposed to the identified hazards. This, in turn, allows decision makers to identify “disaster risk hotspots”, where disaster risk management interventions should be prioritised. National risk assessments support this process by identifying the most serious disaster risks, based on an all-hazards approach, facing a country at the national level (OECD, 2014).

Figure 4.1. Disaster risk assessments

Sources: Based on (OECD/G20, 2012)

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks (OECD, 2014) suggests developing location-based inventories of exposed populations and assets, as well as infrastructures that reduce exposure and vulnerability. It highlights the importance of identifying and assessing inter-linkages between different types of critical risks and their potential cascading effects. The Recommendation furthermore suggests to use the best available evidence incorporating up-to-date scientific models and to take an all-hazards approach to help prioritise disaster risk management interventions. Finally, it is recommended that risk assessments be periodically reviewed to incorporate new information as well as the lessons learnt from recent disaster events.

Quality information on natural hazards and disaster risk: Centrepieces of Colombia’s disaster risk management objectives

Colombia’s Law 1523/2012 promotes the identification of hazards and the assessment of disaster risks as key objectives to be fulfilled by the National Disaster Risk Management System (Sistema Nacional de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres, SNGRD). While Law 1523/2012 focuses on natural hazards only, the National Plan for Disaster Risk Management (Plan Nacional de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres, PNGRD) recognises the importance of an all-hazards approach and calls for improving the evidence base on natural as well as man-made hazards. Finally, Law 1523/2012 calls for the public access to hazard and disaster risk information (Congress of Colombia, 2012).

Hazard and risk information: Availability to date

The current availability and granularity of hazard information differs by type of hazard (Table 4.1). At the national level (resolution of 1:25,000), the available hazard assessments cover almost all hazards and for hydrometeoroligical hazards 96% of the territory. Three national seismic hazard maps, a national landslide hazard map and national flood hazard maps are available. In addition, a national wildfire hazard map was recently developed. At the regional level (resolution of at least 1:5,000), nine departmental drought hazard assessments have been conducted (IDEAM and UNDC, 2013; IDEAM, 2014; IGAC, 2015; SGC, 2015; SGC, 2018; SGC, 2018; DNP, 2018; UNGRD, 2018). At the local level, the implementation review of the National Development Plan confirms that municipal flood hazard mapping is increasingly conducted, albeit substantial work is needed to cover all of the exposed territory.

Table 4.1. Availability of hazard and disaster risk assessments and maps

|

Hazard assessments/maps in place |

If yes: Scope |

Disaster risk assessments/maps in place |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

No |

National |

Regional |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Earthquakes |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

Under development |

||

|

Volcanic activity |

✓ |

✓ |

Under development |

|||

|

Tsunami |

✓ |

Under development |

||||

|

Flood |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

Landslides/rockslides |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

Under development |

||

|

Storms |

✓ |

✓ |

||||

|

Cold wave |

✓ |

✓ |

||||

|

Heat wave |

✓ |

✓ |

||||

|

Drought |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

Wildfire |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

Snow avalanche |

✓ |

✓ |

||||

Source: 2018 OECD Colombia Risk Governance Survey.

In terms of disaster risk assessment, although the available information is scarce, the PNGRD includes a number of projects to change this in the future. The monitoring of the National Plan for Disaster Risk Management shows that several pilot studies for assessing disaster risk are under way. For example, tsunami exposure and vulnerability analyses have been carried out for 56 villages in Cauca and Nariño, and a landslide risk assessment is under way for the municipality of Villarrica, which is one of 120 to be completed by 2025. Following the implementation of Laws 388/19971 and 1454/2011,2 and the seismic building regulations (Reglamento Colombiano de Construcción Sismo Resistente, NSR-10)3, the National Plan for Disaster Risk Management also includes objectives for municipal seismic risk assessments, carried out already in Bogota. Another ongoing project, conducted in co‑operation with Japan, focuses on the modelling of earthquake, tsunami and volcanic disasters with a view to estimate potential disaster losses and damages (JICA, 2014; SIAC, 2012).

The National Disaster Risk Management Unit has been collecting comprehensive disaster damage and loss data for the past 20 years, which can provide valuable information for modelling risk assessments. The disaster loss and damage information is made available in a central public disaster repository, the DESINVENTAR database, which is maintained by the Colombian civil society organisation OSSO Corporation (Corporación OSSO), together with the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (OECD, 2018; UNGRD, 2018).

Good practices on how risk information can effectively guide disaster risk management decisions are emerging. For example, the Bogota Urban Disaster Risk index (UDRi) identifies hazard-prone areas and assesses vulnerabilities and exposure in these locations, with the objective of using the risk information to inform land-use decisions, as well as the development of local building codes (Baker, Anderson and Ochoa, 2012; Carreño, Cardona and Barbat, 2005; IDIGER, 2018; UNGRD, 2018).

National risk assessments are an important tool to guide priority-setting in disaster risk management. National risk assessments synthesise available hazard and disaster risk information to identify a country’s most critical disaster risks (Box 4.1 provides an example from the United Kingdom’s practice). As the process of preparing such an assessment should build on broad stakeholder engagement, they also serve as an important tool to build consensus on disaster risk management priorities (OECD, 2014). Currently, no national risk assessment is carried out in Colombia, but with the recently published National Risk Atlas (Atlas de riesgo de Colombia), the UNGRD has taken an important first step in establishing a national risk assessment process (UNGRD, 2018). As a national risk assessment process also builds on an established co-ordination mechanism that brings a wide range of inputs from across departments and scientific expertise together, the committees within the National System for Disaster Risk Management, with the National Committee for Risk Knowledge in the lead, would be an ideal platform that could serve this purpose.

Box 4.1. United Kingdom National Risk Assessment

The United Kingdom’s National Risk Assessment (NRA) is a yearly process to identify all major hazards and threats that may cause significant negative impacts at any point during the following five years. Led by the United Kingdom’s Civil Contingencies Secretariat (Cabinet Office), it involves a multi-agency process. Risks are ranked based on the likelihood and impact of the “reasonable worst-case scenario”.

The assessed risks cover three broad categories: 1) natural hazards; 2) major accidents; and 3) malicious attacks. Eighty types of major hazard and threat scenarios have been identified and analysed through the NRAs over the years.

The NRA results are used in capabilities‑based planning for emergency preparedness and response at all levels of government, as well as in assigning responsibilities for managing the identified risks to different agencies. While in part confidential, a public version of the NRA is made available through the National Risk Register, which serves as a valuable risk communication tool.

Sources: OECD (2017), Natural Hazards Partnership (2017), United Kingdom Cabinet Office (2017).

Roles and responsibilities

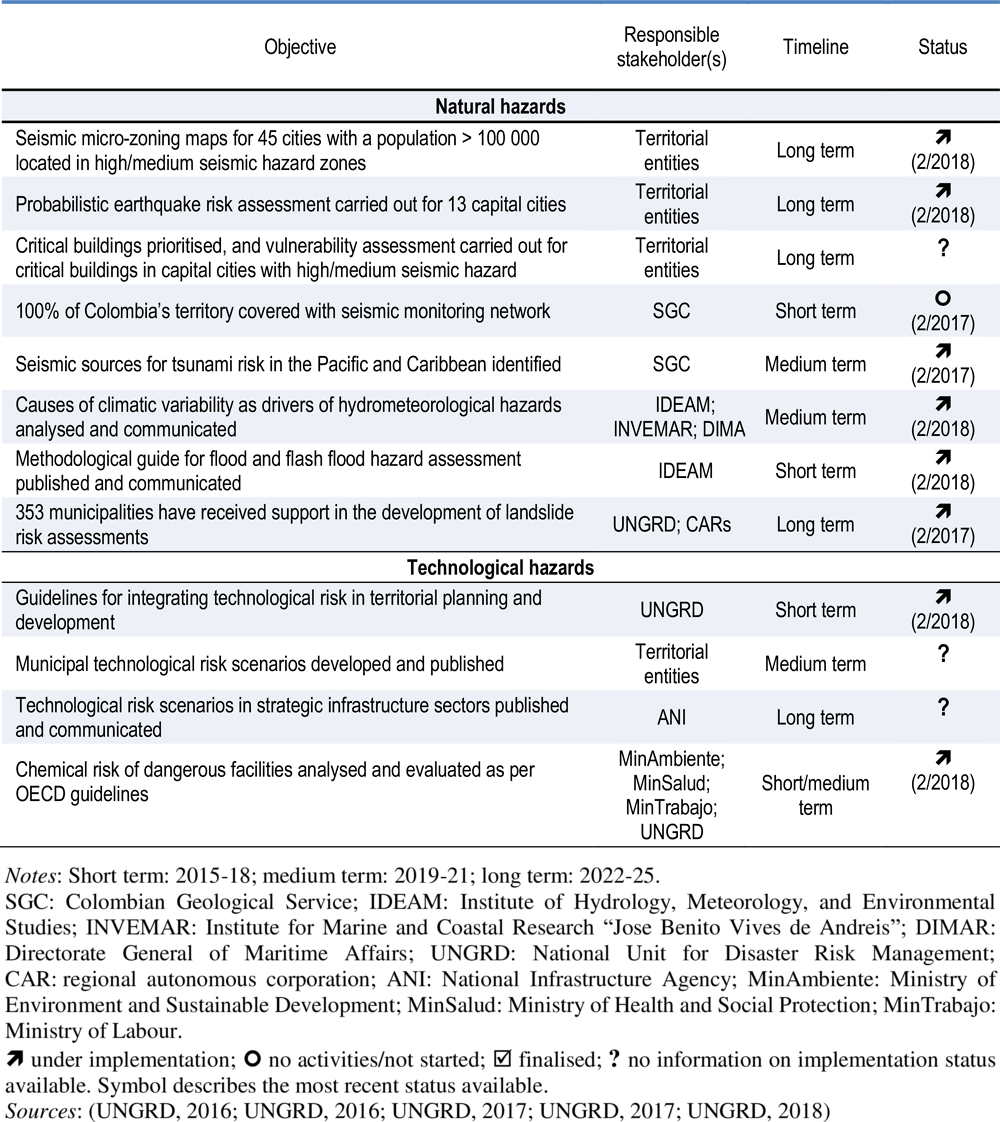

The National Disaster Risk Management Plan and the national development plans make hazard and disaster risk assessments a shared responsibility between central and subnational governments (Table 4.2. ). While the central government agencies are to assess risks at national scale, subnational governments, with technical support from central agencies, are to develop municipal hazard and disaster risk assessments (DNP, 2018; DNP, 2014; UNGRD, 2016).

Recognising the diversity of actors contributing to the hazard and risk assessment process, the National Committee for Risk Knowledge was established as part of the National Disaster Risk Management System as a platform to co-ordinate stakeholders’ efforts to fulfil the shared objectives. Although it convenes many of the stakeholders with responsibilities related to hazard and disaster risk assessments, the National Committee for Risk Knowledge currently focuses on exchange of technical expertise. In the future, the committee’s convening power and the technical expertise of its members have the potential to carry out a full national risk assessment informed by whole-of-government engagement (see above).

The National Plan for Disaster Risk Management requires all infrastructure as well as all public service providers to assess disaster risks arising to their operation. Concrete actions include:

the development of technical guidelines for disaster risk assessments in the telecommunication sector by the Ministry of Information Technologies and Communications that are to be used in turn by both public and private operators;

risk scenarios for strategic infrastructure sectors to be carried out by the National Infrastructure Agency (Agencia Nacional de Infrastructura, ANI);

disaster risk assessment prepared for critical transport infrastructure to be carried out by the Ministry of Transport.

There is scope to improve the sharing of risk knowledge, especially between businesses and government agencies. For example, some oil and energy businesses have conducted detailed analysis of its exposure to a variety of hazards, as have other large industrial sectors, but this information does not have any explicit mechanism that allows for it to be combined with risk information generated by public bodies. Combining these disparate bodies of knowledge could provide new insights and even improve the resolution of the national datasets. With the UNGRD’s guide for shared disaster risk management responsibilities, a first instrument to support public and private stakeholders throughout the disaster risk management cycle, including in the exchange of hazard and disaster risk information, is in place (UNGRD, 2018).

Increasing the availability and quality of hazard and risk information

The National Plan for Disaster Risk Management has put in place specific actions to develop Colombia’s hazard and risk information base. They focus on the assessment of hydrometeorological hazards, sea-level rise induced flood hazards, as well as geophysical hazards. In terms of disaster risk assessment, the National Plan for Disaster Risk Management’s priorities for action are the assessment of landslide risk in “critical” areas, the assessment of risks related to extreme climate events and disaster risk assessment for all major metropolitan areas. The National Development Plan includes further targets to be achieved by 2018, such as on the number of monitoring stations for geological, hydro-meteorological and maritime hazards, as well as for flood and flash flood hazard maps (UNGRD, 2016).

Projects to implement the objectives laid out in the National Disaster Risk Management and the National Development Plan are ongoing. The biannual monitoring report of the National Plan for Disaster Risk Management (Box 3.3) shows some progress to date, with 1 project completed, 34 under way and 4 that have yet to start. The annual implementation review of the National Development Plan (Table 4.3) shows that while the objective to increase the number of Colombian Geological Service monitoring stations was exceeded, none of the other objectives have been fully met yet (Lacambra et al., 2014; DNP, 2017; DNP, 2018).

Table 4.2. Hazard and disaster risk assessment actions in Colombia’s National Plan for Disaster Risk Management, 2015-25 (selection)

Table 4.3. National Development Plan: Disaster risk knowledge objectives, 2014-18

|

Responsible stakeholder |

Baseline value 2013 |

Objective for 2018 |

PND Review 2017 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Monitoring stations |

SGC |

675 |

766 |

864 |

|

Monitoring station |

IDEAM |

136 |

666 |

270 |

|

Monitoring station |

DIMAR |

23 |

28 |

? |

|

Volcanic hazard maps (national) |

SGC |

10 |

13 |

14 |

|

Flood hazard maps at a scale of 1:5 000 |

IDEAM |

29 |

35 |

New flood maps at a scale of 1:5 000 for Achí, Pinillos, Montelíbano, Ayapel, San Marcos, San Benito |

|

Flash flood hazard maps at a scale of 1:5 000 |

IDEAM |

10 |

20 |

Notes: SGC: Colombian Geological Service; IDEAM: Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology, and Environmental Studies; DIMAR: Directorate General of Maritime Affairs.

Sources: DNP (2014), DNP (2018), DNP (2017), DNP (2018).

Accessibility of hazard and disaster risk information

Accessible hazard and disaster risk information is indispensable for resilient land-use planning and stakeholder compliance with the accompanying regulations such as building codes (OECD, 2014). Particularly in the context of rapid urbanisation in hazard-prone areas, as is the case in Colombia, easy access to hazard maps may be a decisive factor in limiting informal construction in hazard-prone areas, or in incentivising households to carry out resilience measures.

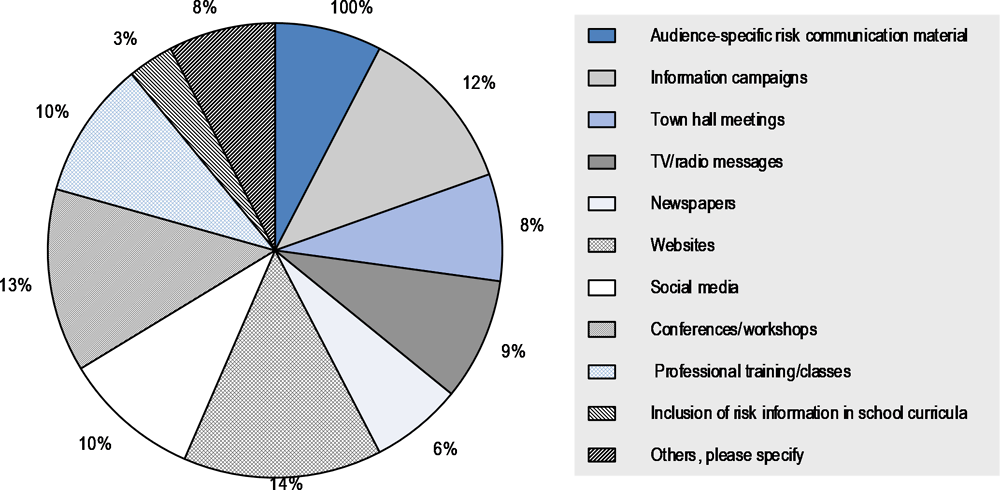

Law 1523/2012 requires stakeholders in the National Disaster Risk Management System to communicate hazard and risk information to the public, as well as to public and private entities. The National Plan for Disaster Risk Management includes the communication of risk information as part of several objectives under the “disaster risk knowledge” pillar. As a result, hazard and disaster risk assessments are made publicly available online and free of charge, published in print and broadcast media and communicated across departments and levels of government4 (e.g. by way of conferences, workshops and trainings) (Figure 4.2). There might be room for further leveraging the National Committee for Risk Knowledge to share hazard and risk information, to co-ordinate collaboration among actors to assess interlinkages of hazards, as well as to evaluate potential cascading effects especially between natural and technological hazards, such as in the case of the Hidroituango dam.

Figure 4.2. Hazard and disaster risk information dissemination channels

Notes: The question asked: “How does your organisation communicate disaster risk information?”. Eighteen out of 23 public sector respondents answered this question.

Source: 2018 OECD Colombia Risk Governance Survey.

Box 4.2. Mexico and Austria: Open access to risk and hazard data

Open access to risk assessment data ensures transparency. Mexico’s National Risk Atlas and Austria’s Natural Hazard Overview and Risk Assessment (HORA) platform are noteworthy tools for giving open access to risk and hazard data.

Mexico’s National Risk Atlas is an online portal (www.atlasnacionalderiesgos.gob.mx) that compiles all available risk information on Mexico, drawing information from the National Centre for Disaster Prevention, the National Seismological Service, the Earth Observation Laboratory and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The available information includes various hazard and vulnerability maps on an evolving GIS-based platform, as well as results of hazard and risk assessments. Metadata on exposed assets and information on socio-economic losses from disasters complements the available information.

Similarly, Austria’s HORA platform (www.hora.gv.at) is a publicly accessible Internet portal that compiles available hazard information into a national hazard map. Individual exposure to hazards (such as floods, avalanches and torrents) can be explored based on one’s address, enabling home owners and businesses to limit construction in hazard zones.

Sources: Nieto Muratalla (2017), OECD (2013), OECD (2017), Austrian Federal Ministry for Sustainability and Tourism (2018).

Accountability and transparency in the hazard and disaster risk assessment processes

For available hazard and disaster risk information to be trusted and acted upon, it is important to ensure transparency in the process of information collection and in the methods used to model hazards and risks Opening up datasets and methodologies to the scientific and academic communities helps encourage scrutiny from learned bodies and specialised individuals, helping improve the quality of the risk information being produced. Opening dialogue with citizens in the hazard and disaster risk assessment processes, through public review and commenting periods for hazard maps, can be useful in creating acceptance of the information and in determining acceptable levels of risks, hence increasing the likelihood that communities threatened by hazards are taking actions to increase their resilience.

In Colombia, all public actions can be put to scrutiny as per Law 1712/2014,5 but such processes are not yet institutionalised for hazard and disaster risk assessments. The Austrian practice to put draft hazard maps up for public review, during which comments are collected and assessed by a commission,6 is a good practice in this regard (Box 4.3). Aside from offering an opportunity to put hazard maps to public scrutiny, these consultations are used to improve hazard maps with local knowledge on experiences with past disasters. Often, the implication of stakeholders in this process has led to an expansion of the proposed hazard zones, which points to an increased acceptance of hazard assessments (Gamper, 2008; OECD, 2017).

Box 4.3. Austria: Improving hazard maps with through public consultation

Hazard mapping in Austria benefits from public participation. Following hazard assessments carried out by the subnational offices of the responsible expert units (Austrian Service for Torrent and Avalanche Control, Federal Water Engineering Administration) within the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management stakeholders have the opportunity to comment on draft hazard maps.

During the public consultation period comments are collected and subsequently assessed by a commission. On the one hand, this ensures public support for the hazard maps and enables increased hazard awareness. Stakeholders have the opportunity to ensure specific local knowledge: good practice from Austria’s needs are considered, and are informed of hazards early on. On the other hand, making hazard mapping inclusive may increase accuracy of the maps, and may result in plea for extending hazard zones. The local population may, for instance, have additional insights into hazards, e.g. from experiences with past disasters, or hope for the installation of structural disaster risk reduction measures, if hazard zones are expanded. Overall, the public consultation periods have seen active engagement, particularly in areas where settlement space is scarce.

Sources: Gamper (2008), OECD (2017).

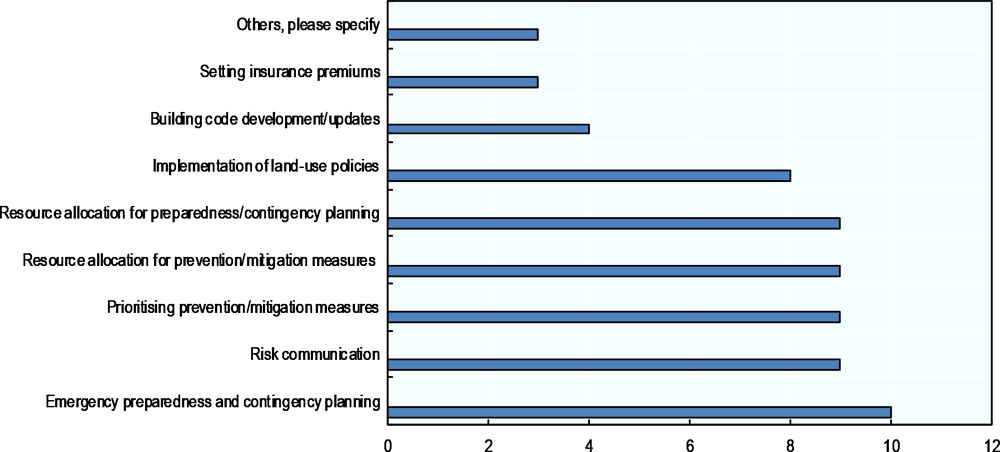

Law 1523/2012 seeks for hazard information and disaster risk assessments to inform disaster risk management decisions, in particular in land-use planning (as also required by the land-use Laws 388/1997 and 1454/2011, and the seismic code). Results from the OECD survey show that many stakeholders in Colombia use the available hazard and disaster risk information in policy making (Figure 4.3). Many respondents noted that the available evidence base is used to guide resource allocation for disaster preparedness, or for planning and prioritising ex ante measures. However, Figure 4.3 also illustrates that there may be scope for further reinforcing the integration of hazard information in land-use planning and building code development. The Ministry of Housing, City and Territory is providing technical support to 250 municipalities on this (DNP, 2014).

Figure 4.3. Use of hazard information across public stakeholders in the National System for Disaster Risk Management

Notes: The question asked: “Are the results of hazard assessments used in the following activities?”. Thirteen out of 23 public sector respondents answered this question.

Source: 2018 OECD Colombia Risk Governance Survey.

Using available hazard information in decision-making

Colombia’s land-use territorial planning advisory councils (consejo consultivo de ordenamiento territorial, CCOT) are a good practice for ensuring that hazard information gets integrated in local land-use plans. The advisory councils are required for all municipalities with more than 30 000 inhabitants (Law 388/1997; Decree 879/19987) and include representatives from across the municipal government, the territorial planning council (consejo territorial de planeación), trade unions and chambers of commerce, and civil society organisations. They are platforms for broad stakeholder review of land-use decisions and may propose revisions, when necessary (Orozco-Sánchez, 2017). The publication of territorial planning advisory council meeting protocols required by Law 1454/2011 creates an incentive for sound decision making and acts as an accountability mechanism. Open access to these protocols can also prevent actors from exercising undue influence, such as developers with an interest to develop hazard‑prone areas such as coasts attractive for tourism development (Orozco-Sánchez, 2017).

References

Austrian Federal Ministry for Sustainability and Tourism (2018), eHORA - Natural Hazard Overview & Risk Assessment Austria, https://www.hora.gv.at/.

Baker, J., C. Anderson and M. Ochoa (2012), Climate Change, Disaster Risk, and the Urban Poor : Cities Building Resilience for a Changing World, World Bank Group, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6018.

Carreño, M. et al. (2009), Holistic Evaluation of Risk in the Framework of the Urban Sustainability, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259641824_HOLISTIC_EVALUATION_OF_RISK_IN_THE_FRAMEWORK_OF_THE_URBAN_SUSTAINABILITY.

Congress of Colombia (2012), Law 1523/2012, https://repositorio.gestiondelriesgo.gov.co/bitstream/handle/20.500.11762/20575/Ley_1523_2012.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y.

DNP (2018), Balance de Resultados 2017 PND 2014-2018: “Todos por un nuevo país” [NDP 2014 – 2018 Balance of results 2017: “All for a new country”], https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/Sinergia/Documentos/Balance_de_Resultados_2017_VF.pdf.

DNP (2018), Índice Municipal de Riesgo de Desastres de Colombia [Municipal Disaster Risk Index for Colombia, https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/Prensa/Presentaci%C3%B3n%20%C3%8D%C3%8Dndice%20Municipal%20de%20Riesgo%20de%20Desastres.pdf.

DNP (2017), Balance de Resultados 2016 PND 2014-2018: “Todos por un nuevo país” [NDP 2014 – 2018 Balance of results 2016: “All for a new country”], https://sinergia.dnp.gov.co/Paginas/Internas/Seguimiento/Balance-de-Resultados-PND.aspx.

DNP (2014), Bases del Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2014-2018 “Todos por un nuevo país: paz, equidad, educación” [Foundations of the 2014-2018 National Development Plan. “Everybody for a new country: peace, equality, education”], https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/cdt/prensa/bases%20plan%20nacional%20de%20desarrollo%202014-2018.pdf.

Gamper, C. (2008), “The political economy of public participation in natural hazard decisions – a theoretical review and an exemplary case of the decision framework of Austrian hazard zone mapping”, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci, Vol. 8, pp. 233-241, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-8-233-2008.

IDEAM (2014), Zonificación del riesgo a incendoios [Wildfire risk zoning], http://www.ideam.gov.co/web/ecosistemas/zonificacion-del-riesgo-a-incendios.

IDEAM and UNDC (2013), Zonificación de amenazas por inundaciones a escala 1:2.000 y 1:5.000 en áreas urbanas para diez municipios del territorio colombiano [Flood hazard zoning at at 1:2.000 and 1:5.000 scale in urban areas for ten municipalities of the Colombian territory, http://www.ideam.gov.co/documents/14691/15816/10+Mapas+Urbanos+de+Amenaza+de+Inundaci%C3%B3n/d943552d-2294-45d6-8145-ce72292caf4b?version=1.0.

IDIGER (2018), Caracterización General del Escenario de Riesgo Sísmico [General Characterization of seismic risk scenarios], ://www.idiger.gov.co/en_GB/rsismico?p_p_auth=QxiGo9cj&p_p_id=49&p_p_lifecycle=1&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&_49_struts_action=%2Fmy_sites%2Fview&_49_groupId=20182&_49_privateLayout=false.

IGAC (2015), 9 departamentos de Colombia cuentan con mapas de riesgo agroclimático por inundaciones y sequía [9 Colombian departments count with agroclimatic risk maps for floods and droughts], https://noticias.igac.gov.co/es/contenido/9-departamentos-de-colombia-cuentan-con-mapas-de-riesgo-agroclimatico-por-inundaciones-y.

JICA (2014), Application of State of the Art Technologies to Strengthen Research and Response to Seismic, Volcanic and Tsunami Events, and Enhance Risk Management, http://www.jst.go.jp/global/english/kadai/h2606_colombia.html.

Natural Hazards Partnership (2017), National Riks Assessment, http://www.naturalhazardspartnership.org.uk/products/national-risk-assessment.

Nieto Muratalla, A. (2017), The Real Cost of Disasters: Identifying Good Practices to Build Better Evidence for Investing In Disaster Risk Managment.

OECD (2018), Assessing the Real Cost of Disasters: The Need for Better Evidence, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264298798-en.

OECD (2017), Boosting Disaster Prevention through Innovative Risk Governance: Insights from Austria, France and Switzerland, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264281370-en.

OECD (2017), The UK’s National Risk Assessment (NRA), https://www.oecd.org/governance/toolkit-on-risk-governance/goodpractices/page/theuksnationalriskassessmentnra.htm#tab_description.

OECD (2014), OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks, http://www.oecd.org/gov/risk/Critical-Risks-Recommendation.pdf.

OECD (2013), Review of the Mexican National Civil Protection System, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264192294-en.

OECD/G20 (2012), Methodological framework on disaster risk assessment and risk financing, OECD Publishing, http://www.oecd.org/gov/risk/G20disasterriskmanagement.pdf.

Orozco-Sánchez, A. (2017), El Consejo Consultivo de Ordenamiento Territorial [Land-use planning advisory councils], http://elpilon.com.co/consejo-consultivo-ordenamiento-territorial/.

SGC (2018), Evaluación y Monitoreo de Actividad Sísmica [Seismic Activity Assessment and Monitoring], https://www2.sgc.gov.co/ProgramasDeInvestigacion/geoamenazas/Paginas/actividad-sismica.aspx.

SGC (2018), Zonificación de amenaza, vulnerabilidad y riesgo por movimientos en masa en el Municipio de Cajamarca - Tolima a escalas 1:25.000 y 1:2.000, [Hazard, vulnerability and risk zoning by mass movements in the Municipality of Cajamarca], https://www2.sgc.gov.co/ProgramasDeInvestigacion/geoamenazas/Paginas/zonificacion-Cajamarca.aspx.

SGC (2015), Mapa de Amenaza Volcánica del Volcán Nevado del Ruíz, Tercera Versión (2015) [Nevado del Ruiz Volcano Hazard Threat Map], http://www2.sgc.gov.co/sgc/volcanes/VolcanNevadoRuiz/Documents/Mapa.

SIAC (2012), Mapas de inundación de Colombia [Flood risk maps of Colombia], http://www.siac.gov.co/inundaciones.

UNGRD (2018), Atlas de riesgo de Colombia: revelando los desastres latentes [Colombia’s risk atlas: revealing disasters], https://repositorio.gestiondelriesgo.gov.co/handle/20.500.11762/27179.

UNGRD (2018), Guía para aplicar protocolo de corresponsabilidad pública, privada y comunitaria en Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres [Guide for shared Disaster Risk Management responsibilities], https://repositorio.gestiondelriesgo.gov.co/handle/20.500.11762/27103.

UNGRD (2018), National System for Disaster Risk Management, Presentation at the OECD-UNGRD Colombia Risk Governance Scan Kick-off event, Unidad Nacional de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres.

UNGRD (2018), Plan Nacional de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres - Una estrategia de desarrollo 2015 - 2025.Cuarto Informe de Seguimiento y Evaluación [National Plan for Disaster Risk Management - A 2015- 2025 development strategy.Fourth Monitoring and Assessment Report, http://repositorio.gestiondelriesgo.gov.co/bitstream/handle/20.500.11762/756/Cuarto_Informe_seguimiento_PNGRD.pdf?sequence=43&isAllowed=y.

UNGRD (2017), Plan Nacional de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres - Una estrategia de desarrollo 2015 - 2025.Segundo Informe de Seguimiento y Evaluación [National Plan for Disaster Risk Management - A 2015- 2025 development strategy.Second Monitoring and Assessment Report, http://repositorio.gestiondelriesgo.gov.co/bitstream/20.500.11762/756/29/Segundo-informe-seguimiento-evaluacion-PNGRD-V2-.pdf.

UNGRD (2017), Plan Nacional de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres - Una estrategia de desarrollo 2015 - 2025: Tercer Informe de Seguimiento y Evaluación [National Plan for Disaster Risk Management -A 2015 -2025 development strategy:Third Monitoring and Assessment Report], http://repositorio.gestiondelriesgo.gov.co/bitstream/handle/20.500.11762/756/Tercer-informe-seguimiento-evaluacion-PNGRD-.pdf?sequence=30&isAllowed=y.

UNGRD (2016), Plan Nacional de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres - Una estrategia de desarrollo 2015 - 2025 [National Plan for Disaster Risk Management - A 2015 - 2025 development strategy], http://repositorio.gestiondelriesgo.gov.co/handle/20.500.11762/756.

UNGRD (2016), Plan Nacional de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres - Una estrategia de desarrollo 2015 - 2025. Primer Informe de Seguimiento y Evaluación [National Plan for Disaster Risk Management - A 2015 - 2025 development strategy.First Monitoring and Assessment Report, http://repositorio.gestiondelriesgo.gov.co/bitstream/20.500.11762/756/26/PNGRD-2015-2025-Primer-informe-seguimiento-evaluacion.pdf.

United Kingdom Cabinet Office (2017), National Risk Register, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/61934/national_risk_register.pdf.

Notes

← 1. Law 388/1997, Congress of Colombia, http://recursos.ccb.org.co/ccb/pot/PC/files/ley388.html (in Spanish, consulted on 16 July 2018).

← 2. Law 1454/2011, Congress of Colombia, www.senado.gov.co/images/stories/Dependencias/Comision_ordenamiento/LEY_1454_DE_ORDENAMIENTO_TERRITORIAL.pdf (in Spanish, consulted on 25 July 2018).

← 3. Seismic building regulations (Reglamento Colombiano de Construcción Sismo Resistente, NSR‑10), Colombian Association for Earthquake Engineering, www.asosismica.org.co/decretos-modificatorios-nsr-10 (in Spanish, consulted on 25 July 2018).

← 4. Ninety-three per cent of the respondents to the 2018 OECD Colombia Risk Governance Survey stated that hazard information is publicly accessed free of charge; 92% noted that this information is communicated across departments and levels of government to ensure policy consistency.

← 5. Law 1712/2014, Congress of Colombia, http://suin.gov.co/viewDocument.asp?ruta=Leyes/1687091 (in Spanish, consulted on 25 July 2018).

← 6. The commission usually includes one ministerial delegate, the regional planner, the regional head of section and one representative of the municipality for which the plan has been designed (mayor). In some cases, additional technical experts participate.

← 7. Decree 879/1998, Presidency of Colombia, www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=1369 (in Spanish, consulted on 25 July 2018).