This chapter tackles the structural problem of the current pension system, in which the public and private components operate in parallel in a fragmented and incoherent manner and individuals have to choose to contribute to the public or private system. Policy options discussed in this chapter aim to establish a solid framework for the contributory pension system where the public and private components are complementary and the system operates in an integrated and efficient manner, while addressing the sustainability of the entire system going forward.

OECD Reviews of Pension Systems: Peru

Chapter 4. Establishing a solid framework for the contributory pension system

Abstract

The pension system in Peru is made up of different components that do not necessarily align to best promote the objective of the system to provide old-age pensions to Peruvians. The contributory component is made up of a public and a private scheme that, rather than being complementary in their provision, function as two separate alternatives for workers. As in other Latin American countries, the introduction of private pensions in Peru was driven by fiscal pressures on its public PAYG system as a result of changing demographics and the resulting imbalance between contributions and pension promises. However, due to political considerations and the cost of transitioning fully to a private pension system, Peru maintained the public PAYG system and introduced the funded individual accounts in parallel rather than implementing a complementary public and private pension provision or moving fully to a private system.

The public pension component is also fragmented, with numerous schemes for specific populations being managed under the public system (SNP). There are a number of different schemes under Special Regimes, where journalists, pilots and housekeepers, amongst others have their own rules within the SNP.

The institutional organisation of the pension system is far from seamless. Two separate institutions oversee the two systems, the ONP and the SBS respectively, and each operates in a silo without official communication or information sharing channels in place.1 The non-contributory component, Pensión 65, is managed completely independently from the rest of the pension system by MIDIS, and here again there are challenges with respect to sharing information with the other institutions to facilitate having a complete view on how the pension system in Peru achieves its objectives. The lack of collaboration across institutions has led to procedural errors that harm pensioners. Contributions that employers pay to the wrong system or do not pay at all are often lost to the affiliates who thought they had been paid properly.

Efforts to improve the financial sustainability of the public system have also undermined the objective of the pension system to provide a pension, resulting in unintended consequences. Parametric reforms reduced the generosity of benefits and made eligibility requirements to receive a pension under the public system more restrictive, namely by increasing the minimum number of contributions years to receive a pension to 20 years. As a result, many pensioners contributing to the public system will no longer receive a contributory pension because they will not achieve 20 years of contributions.

Reforms implemented to improve the financial sustainability of special regimes have not gone far enough. Benefits from the CPMP for the military and police, for example, are primarily funded by transfers from the general budget to cover the shortfall, despite reforms that increased contributions and reduced benefits.

In order to have a more coherent and financially sustainable pension system, Peru first needs to remove the competition and duplication in the pension system between the public and private components and implement a system where these two components are complementary. It also needs to take measures to ensure the long-term sustainability of the new system and the existing special regimes and harmonise the rules across different occupational groups. Finally, measures need to be implemented to improve coordination and information sharing across the institutions participating in the system to allow the system to function more efficiently in a cost-effective manner.

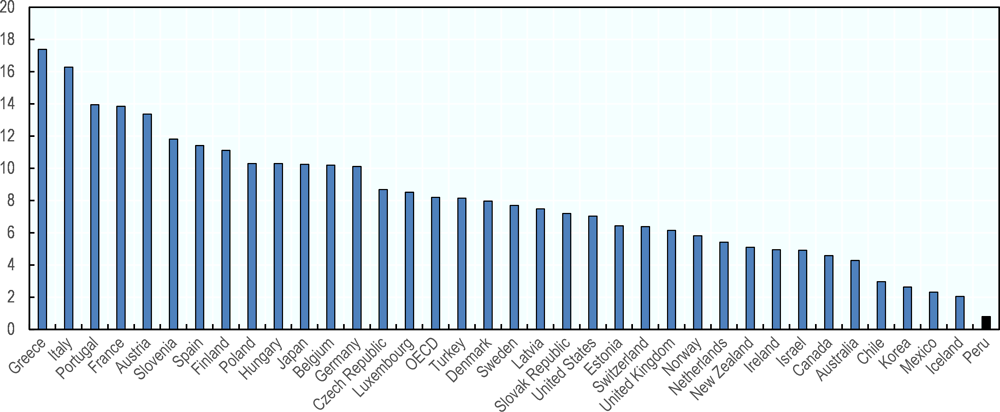

4.1. The choice between the SNP and the SPP

At the end of 2017, the total number of affiliates in the SPP was 6.6 million, compared to 4.5 million affiliates in the SNP, shown in Figure 4.1.2 The number of affiliates in the SPP grew to 7 million in 2018. However, only a proportion of these affiliates are actively contributing to either system. The proportion of affiliates contributing to the SNP has steadily decreased since 2002 from a level over 50% to only 35% in 2017. The proportion of affiliates contributing to the SPP has remained more stable and has even increased slightly, exceeding 40% since 2009.

Figure 4.1. Affiliates and contributors to the SPP and SNP

Source: ONP; SBS.

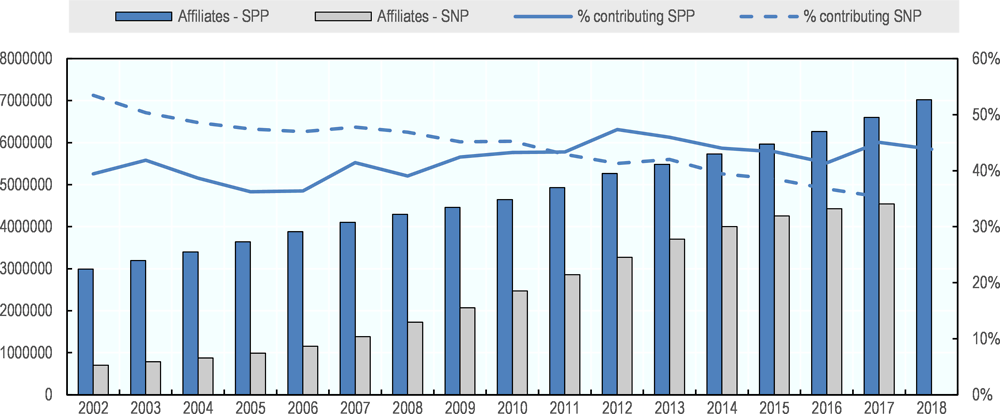

Even though the SPP has a larger number of affiliates in total, in recent years a larger number of new affiliates had been joining the SNP, as shown in Figure 4.2. There was also a spike in new affiliates in 2013 to the SNP, in part due to the new obligation for independent workers to enrol in the system. However, the difference in the number of new affiliates joining the SNP and the SPP has been reducing since the regulatory changes in 2013 that facilitated the enrolment process to the SPP. In 2017, enrolment to the SPP exceeded that for the SNP. However, over 40% of new affiliates to the SPP in 2016 and 2017 were individuals switching from the SNP, the exact figures being 136 460 and 153 359 individuals, respectively.3 This means that the majority of new contributors still join the public system, despite the measures in place to facilitate enrolment in the private system, and their initial contributions to the SNP are lost.

Figure 4.2. New affiliates to the pension system

Source: ONP; SBS.

The SNP and the SPP present different features that could lead members to enrol in one over the other. However, while members affiliated with the SNP are allowed to switch to the SPP at any time, those in the SPP are only allowed to go back to the SNP under certain very specific conditions.

The process and rules to enrol in the pension system have tended to favour enrolment in the SNP. When first entering the formal labour force, new workers must choose to contribute to either the SNP or the SPP. Within the first ten days of employment, employers are required to provide the employee with a document describing the main features of each system. Employees have ten days to choose which system to contribute to, and an additional ten days to change their mind. Prior to 2013, the process for enrolling employees in the SNP was relatively simpler than that for the SPP, and partly as a result of this, more new affiliates joined the SNP than the SPP. The administrative process to join the SPP was simplified in 2013, and since then the employee has been able to sign the contract for the SPP after they have been enrolled.

Despite efforts to simplify the enrolment process to the SPP, new employees are still often enrolled to the SNP. If the employee does not make any decision within ten days, the regulatory framework requires the employer to enrol the employee in the SPP. However, in practice employers will initially enrol employees in the SNP because they can always switch to the SPP.

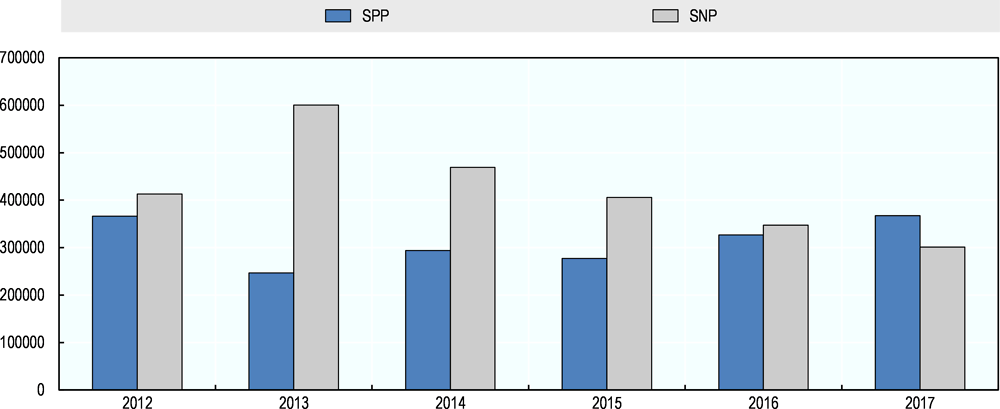

The number of years that individuals expect to contribute to the system likely lead to a preference for the SPP. If individuals have not contributed 20 years to the SNP, they will not be eligible for either pension benefits or health benefits, whereas under the SPP individuals will have a right to the amount of capital in their individual account and health benefits upon retirement regardless of the number of contributions made. Figure 4.3 shows that since 2010, up to 37% of applications for a pension under the SNP were denied because individuals could not prove eligibility for benefits. Since the peak in 2014, the proportion of denied applications has decreased to only 18% in 2017. This is in part because it has become easier for individuals to prove that they have made 20 years of contributions in recent years. There were no registers of contributions prior to 1999, so before this, individuals had to prove their contributions by showing their payslips. However, over the last few years, the ONP has worked to complete the registers, and now 85% of individuals are fully accredited in the system with proof of their years of contributions. Nevertheless, the minimum threshold of twenty years of contributions disproportionally affects low income groups, who have a higher probability of not contributing enough to be eligible for a pension under the SNP (Comision de Proteccion Social, 2017[1]). The contributions of these groups would therefore be subsidizing benefits for those who will be able to achieve 20 years of contributions.

Figure 4.3. Applications for pensions under the SNP

Source: ONP.

Nevertheless, when low-income groups are able to achieve twenty years of contributions, the minimum pension provided by the SNP can be a significant benefit for them, as the SPP does not offer a minimum pension. Indeed, 22% of Peruvians feel that receiving a minimum pension is one of the main reasons to contribute to the system (Arellano marketing, 2017[2]). Pensión 65 does provide benefits to all elderly not receiving a pension and in extreme poverty, but the benefit of PEN 250 every two months is significantly lower than the minimum monthly pension of PEN 415 under the SNP that is paid 14 times per year.

The maximum pension paid under the SNP can be a deterrent for high-income people to remain in this system. The maximum pension of PEN 857.36 is now below the minimum wage established in April 2018 of PEN 930. Since the pension thresholds have been detached from the minimum wage calculations, there are no plans to adjust them. In today’s terms, a person earning around two times the average annual wage would already be at the maximum pension level after 20 years of contributions.

While disability and survivor benefits also differ between the two systems, these benefits alone are not likely to incite individuals to choose one system over the other. The SPP offers higher disability benefits for those with total disability, but the SNP offers higher benefits to surviving spouses.

Similarly, contribution levels are not likely to have a large influence on the decision between the two systems, as they are nearly identical. When the SPP was first introduced, total contributions were higher than the 13% contributions for the SNP. In order to make the SPP more attractive, the 1% solidarity contribution to the SPP was removed in 1995 and contributions to the individual accounts were reduced from 10% to 8%. These contributions have since been reinstated at 10%, and with the insurance premium of 1.36% and the average fees to the AFPs of 1.26%, affiliates to the SPP contribute slightly less than the affiliates of the SNP.4

A significant draw for individuals to switch to the SPP is that they will have direct access to the capital that they contribute. During the accumulation phase, 25% of the account balance can be withdrawn for the purchase of a first home. At retirement, which for the majority of individuals is well before the normal retirement age of 65, 95.5% of the capital can now be withdrawn as a lump-sum. This access to capital could incite individuals to transfer from the SNP to the SPP even when it is not in their financial best interest. Indeed, in 2016 and 2017, over 40% of new affiliates to the SPP had transferred from the SNP despite not receiving any recognition bonus of contributions made since 2001, though many of these transfers were likely done soon after their initial enrolment to the SNP.

Nevertheless, most individuals have a low level of understanding of the differences between the two systems, and are not likely making the decision regarding which system to contribute to in a way that optimises their likely financial outcomes. The perception of whether the pension that individuals will receive will be sufficient to cover their expenses in old age is broadly similar between the SNP and the SPP, despite large differences in their expected replacement ratios (SBS, 2018[3]).

4.2. Procedural errors from a parallel system

The rules around the acquisition and retention of pension rights in either system is very strict. While it is possible to transfer from the SNP to the SPP, the previous contributions need to be transferred through Recognition Bonds, otherwise they will be lost. Individuals who contribute to the SNP after having contributed to the SPP have no such mechanism and will forfeit any contributions that have been made to the SPP.

These rules can create significant risks that affiliates may not be entitled to any pension, or a pension at a lower level than they expected. Because of the unique duality of the system it is important at the start of the career, and when changing employers, that the contributions are going to the correct place. While the body to collect taxes, SUNAT, has the information to check this process, they do not have the mandate to do so. AFPs are responsible for ensuring that the employers are paying the contributions of their employees enrolled in the SPP. However, if an individual changes employer and the AFPs are not informed, there is no mechanism for them to ensure that the new employer does not make payments to the SNP by mistake. As a result, any contributions mistakenly going to the SNP are not flagged and employees often do not notice that their contributions are going elsewhere until they near retirement. As there are no mechanisms for individuals to recoup the wrongly paid contributions, they are ultimately forfeited.

At the end of 2016, the amount of contributions that had been wrongly paid to the SNP totalled PEN 1.67 billion, and the monthly flow of contributions mistakenly going to the SNP averaged around PEN 10 million. The majority of these have been for private sector employers, though the public sector does make up a significant portion of the total, as seen in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1. Contributions misdirected to the SNP

As at December 2016

|

Amount of declared contribution (PEN) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Type |

Before 2012 |

After 2012 |

Total |

|

Not valid |

10 813 370 |

656 709 |

11 470 079 |

|

Business owners |

77 327 124 |

54 226 454 |

131 553 578 |

|

Public sector |

484 301 180 |

124 929 048 |

609 230 228 |

|

Private sector |

596 022 946 |

320 697 483 |

916 720 429 |

|

Total |

1 168 464 620 |

500 509 694 |

1 668 974 314 |

Source: ONP (Oficio No. 307-2016-DRP/ONP 03/11/2016).

The government has taken some steps to correct the situation of misdirected contributions. The Legislative Decree N. 1275, approving the Fiscal Responsibility and Transparency Framework of Regional Governments and Local Governments, came into force at the end of 2016. This decree authorized the ONP to return the misdirected contributions that had been made by regional and local governments between January 2012 and December 2016 to the AFPs, though affiliates still cannot reclaim contributions misdirected before 2012. The decree does not, however, oblige the ONP to return these contributions or pay any interest on them.

Of the PEN 125 million in the public sector, PEN 105.7 million falls within the Regional and Local governments that the ONP is authorised to return, of which PEN 20 million will be returned between 2018 and 2022 using the surplus of contributions being paid into the SNP.

Generally, employers are responsible for correcting the situation if they have mistakenly transferred contributions to the SNP. They may request the ONP to return the amounts paid. The ONP may opt to pay the sum back in instalments.

In other cases of mishandling of contributions, the contributions can disappear completely, with the employer never transferring the employee’s contribution to the AFP. If the employer does not comply with the timely payment of the contribution to the SPP, it must provide a statement to the SBS and pay the contributions in the same period or otherwise face a fine of 10% of the tax unit (UIT) for each worker for whom they did not declare contributions. The AFPs are responsible for filing the demand for the collection of missing contributions, and they must determine the amount owed by the employer.

4.3. Cost and financing of the SNP

While reforms to the pension system have improved the financial sustainability of the public system, this has also meant that fewer people will be able to receive a pension from the SNP, even if they do not switch to the SPP. The rules of the system also make it difficult to have an accurate estimate of the liabilities of the SNP, because individuals have the option to move from the SNP to the SPP at any point throughout the career, and many of those who do not switch will not achieve the 20 years of contributions needed to be eligible for benefits. In 2017, net actuarial liabilities of the SNP for those belonging to the system were around PEN 35 billion (around 5% of GDP), but when accounting for the people who will not manage to have 20 years of contributions the liability estimate would be much lower.

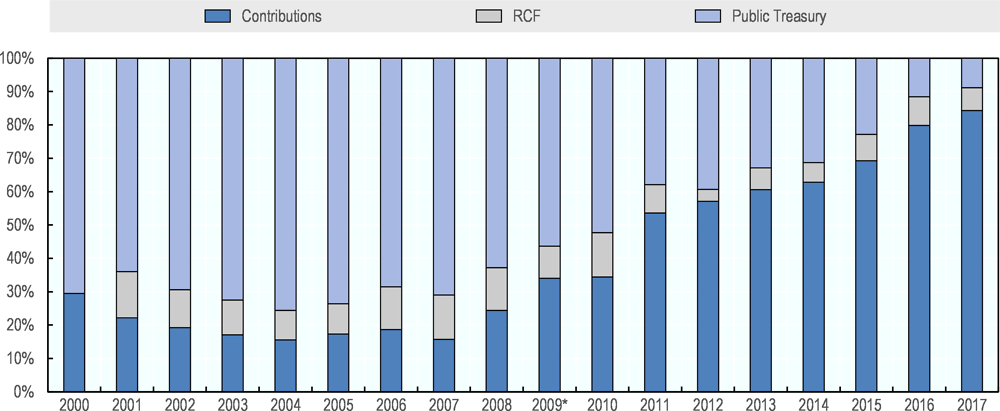

The SNP is on the path to becoming self-sufficient with respect to the financing of benefits paid. The pension benefits of the SNP are paid from incoming contributions, funds from the reserve fund (RCF) and funding from the public treasury. The proportion of funding required from the state to pay for the SNP benefits has steadily declined since 2000, shown in Figure 4.4. From 2000 to 2007, the state consistently contributed around 70% of the benefit payments because of the decline in contributions with individuals having moved to the SPP. However, since then the amount of state support required has fallen considerably as the balance between contributors and pensioners within the SNP has improved. State support in 2017 was only 8.8% of the total SNP benefits, and internal forecasts predict that the contributions will totally finance the pay-outs within the next two years.

Figure 4.4. Sources of financing of the SNP

Note: *includes PEN 14.6 million in contributions received directly.

Source: ONP.

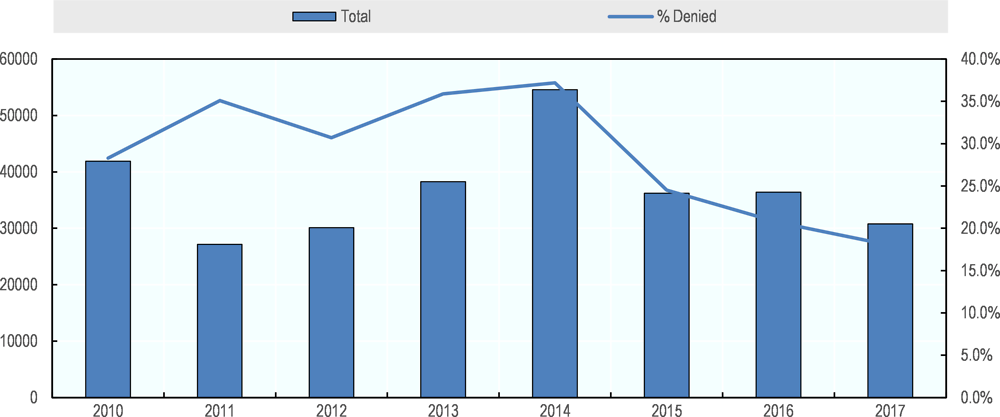

Indeed, at only 0.8% of GDP, public expenditure on pension benefits in Peru is extremely low compared to OECD countries. Figure 4.5 shows that this level is less than half of Iceland’s expenditure, who spends the least among all OECD countries.

Figure 4.5. Public expenditure on old-age and survivor benefits

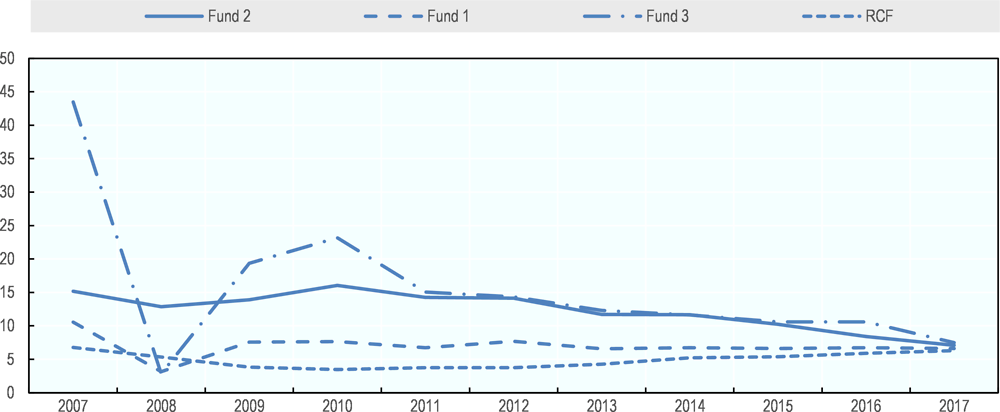

The investment management of the reserve fund (RCF) has also been improving over time relative to the investment performance of the funds of the SPP. Over the last decade, the long-term rate of return achieved by the SPP managers has been consistently above that of the SNP fund managers. Figure 4.6 shows that the 10-year nominal annual return of the RCF has been below the returns of even the conservatively invested Fund 1 of the SPP. However, these average returns converged more in 2017.

Figure 4.6. 10-year nominal annual returns of the SPP and RCF

Note: Simple average.

Source: ONP; SBS.

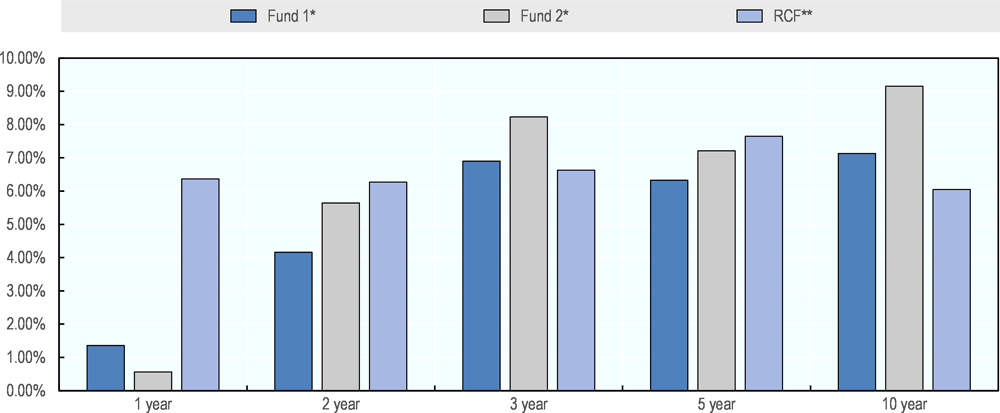

The relative performance of the RCF has improved since the introduction of the strategic asset allocation that was approved in 2012. Figure 4.7 shows that the average annual return of the RCF over shorter time horizons (shown on the x-axis) has been more comparable or even exceeded the returns of the SPP Fund 1 and Fund 2.

Figure 4.7. Annualised nominal return of the SPP and RCF, 2018

Note: *Market value, market average in October 2018; **RCF Methodology;

Source: ONP; SBS.

Nevertheless, the returns of the RCF are not directly comparable to those in the SPP. A comparison of the two approaches needs to take into account the different valuation methodologies, investment strategies, and investment restrictions. The returns of the AFP are calculated based on market values, whereas the returns of the RCF are a mix of market and book value. The RCF’s investment strategy also tends to invest in more growth assets, and compared to funds in the SPP it is able to invest in higher levels of alternative investments as well as directly in real estate.

If a higher rate of return were to be more consistently obtained, this could help to fully finance benefit payments from the SNP.

4.4. Cost of special pension schemes

Reforms have also aimed to improve the financial sustainability of special pension schemes, though significant deficits remain. Many special pension schemes have large financial liabilities for the state. One of the largest is the Caja de Pensiones Militar Policial (CPMP) for the military and police, which is still open for new employees. There are, however, three distinct contribution periods within the CPMP system. Those insured before 9 December 2012 are covered under Decreto Ley No 19846 with contributions set at 12% of earnings, split equally between employees and employers, and benefits equal to 100% of final salary for a 30-year career. An actuarial assessment conducted in 1973 concluded that to finance such a benefit level the contributions needed to be set at 27% of earnings. This system was closed to new entrants in 2011, after which new entrants are covered by Decreto Legislativo No 1133. Under this regime, the contribution still remained at 12%, split equally between employee and employer but with a reduced future benefit promise of 55% of last five years’ salary for a 30-year career. Since January 2018, new entrants contribute 19% (split 13% employee and 6% employer) with this same future benefit promise.

Consequently, as the funding for the old system was not sufficient to finance the pension promises, there is an annual deficit that is being met by general government finances. In 2018, this amounted to PEN 633.8 million, around 0.1% GDP. The reliance on transfers will only increase in the coming years as the number of contributors relative to pensioners has been declining, as shown in Table 4.2 for the old system.

Table 4.2. CPMP pension payments and sources, 2017

|

|

|

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Contributors (old system) |

Armed Forces (FFAA) |

43 689 |

41 668 |

40 353 |

39 226 |

38 162 |

36 897 |

|

National Police (PNP) |

100 892 |

94 411 |

90 320 |

85 688 |

82 350 |

79 221 |

|

|

Total |

144 581 |

136 079 |

130 673 |

124 914 |

120 512 |

116 118 |

|

|

Pensioners (old system) |

FFAA |

19 785 |

21 420 |

23 030 |

23 835 |

24 916 |

26 167 |

|

PNP |

25 246 |

30 758 |

35 088 |

38 640 |

41 472 |

43 898 |

|

|

Total |

45 031 |

52 178 |

58 118 |

62 475 |

66 388 |

70 065 |

|

|

Contributors (new system) |

FFAA |

2 160 |

4 322 |

6 759 |

9 004 |

10 995 |

13 228 |

|

PNP |

3 632 |

19 518 |

27 342 |

34 874 |

42 299 |

48 973 |

|

|

Total |

5 792 |

23 840 |

34 101 |

43 878 |

53 294 |

62 201 |

Source: CPMP.

The gap between the level of pensions and contributions is also widening under the old system, as shown in Table 4.3. In 2017, the gap was around PEN 1.2 billion, but increased to nearly PEN 2 billion, representing 0.25% of GDP in 2018.

Table 4.3. Level of contributions and pensions by year to the old system

Thousands of soles

|

|

2017 |

2018 |

|---|---|---|

|

Contributions |

435 525 |

423 814 |

|

Pensions |

1 656 388 |

2 408 866 |

Source: CPMP.

While the new regime has better aligned contributions with the promised benefits, it is not without its own challenges. It remains unregulated and without investment guidelines, and takes an investment approach more in line with a PAYG system rather than taking a liability driven investment approach. There is also some uncertainty concerning operational continuity, and the deficit and technical risks of the old regime remain.

4.5. Policy options

In order to have a comprehensible and coherent pension system, the design of the system needs to eliminate the competition between the public and private systems and promote the complementarity of the two components in a financially sustainable manner. This could be done by retaining both the public and private components, but requiring that all members contribute to and receive pensions from both. The design of the benefit formula for the public component needs to ensure that even individuals with short careers will accrue entitlements and that in aggregate benefits will continue to be aligned with the contributions being paid in order to ensure the financial sustainability of the system. A minimum pension should be in place to complement the non-contributory Pensión 65 and provide incentives for people to contribute to the system.

Transitioning to the new system will require a decision regarding the appropriate split of contributions between the public and private system. This split could be done in such a way that the flows of contributions to both systems remain relatively stable in order to smooth the transition to the new system. This is important especially for the SNP, as pension promises are fixed, and would allow contributions to continue to cover benefit payments. Implementation costs will also be lower if the rules of the new system apply immediately to all future benefit accruals for everyone currently in either system.

All workers should be in the same system subject, generally, to the same rules. Therefore, all workers in the special regimes should be brought to the new complementary system. The rules of the special regimes, apart from the police and military fund, should be aligned with the rules of this system. For the police and military fund, contributions rates should be aligned to those introduced for new employees since 2018, with past contributions being preserved.

In order for the pension system to operate efficiently as a whole, the administration and data collection for the system could be centralised. This could be done through a single platform operated jointly by the public and private sectors that has the mandate to collect contributions and enforce their payment, as well as gather relevant data. This would improve data-sharing and coordination of the institutions involved and minimise the opportunity for procedural errors.

4.5.1. Design a complementary and financially sustainable pension system

Removing the competition between the public and private contributory pension schemes will provide individuals with a more comprehensible and coherent pension system. There are several options to achieve this. The first could be to close the SPP and have all benefits provided by the SNP. The second could be to close the SNP and have all benefits provided by the SPP. The third would be to keep both the public and private components, but make them complementary rather than forcing individuals to choose one or the other. If the SNP were retained, the benefit formula would need to be restructured in order to ensure financial sustainability, while providing pension entitlements to those who contribute to the system for less than 20 years. Automatic mechanisms would also need to be put in place to adjust the parameters and benefit levels to the macroeconomic and demographic realities, perhaps in an actuarially fair manner. If the SPP is retained, the cost and public perception of the AFPs would need to be improved, and the function of the system to provide a stream of income at retirement restored by removing the option for taking all the assets accumulated as a lump-sum.

The recommendation for Peru is to make both the public and private components complementary. The OECD recommends a balanced pension system combining public and private components (OECD, 2018[5]). The option of retaining both systems would need to address the problems that both systems currently have, but has the key advantage of promoting a diversified pension system and allowing for a smoother transition to the improved, complementary pension system.

Retaining only the public system would not be an optimal solution for Peru due to the related fiscal challenges and the erosion of trust in the system that a reversal of past reforms could create. The private pension system was originally introduced as a response to address the challenges relating to the fiscal sustainability of the public system, though at the time one option would have been to rebalance the public scheme and introduce automatic actuarial mechanisms. Given the changing demographics, fiscal pressures on the public system could only be expected to increase. The parametric adjustments that have been made to improve the sustainability of the system have left many in the system without any benefits at all because of the requirement for 20 years of contributions. Furthermore, if this option was adopted, the authorities would need to decide whether to transfer the assets accumulated in the SPP to the individual, who own the assets in their accounts, or to the public system, to cover for their pension entitlements. Either way, it would likely create significant problems of confidence in the pension system.

One main disadvantage of the second option of moving fully to a private system would be the large transition cost of doing so. First, the benefits of the current pensioners would still need to be financed, which would represent a financial burden for the public treasury, whereas under the current system they are expected to be fully financed by incoming contributions by 2020. Secondly, the contributions that current affiliates have made to the public system would need to be recognised in some manner, likely through recognition bonds, which would represent a significant additional increase in fiscal cost in the future.

The Peruvian authorities should consider the third option of retaining both the public and private components, which would provide a solution that could minimise the disruption to the current system while benefiting from the diversification of risks that a complementary PAYG and funded system could provide. Indeed, one of the main policy messages of the OECD is to promote diversity in the source of pensions in order to better mitigate the numerous risks faced in financing retirement (OECD, 2018[5]).

For this option, the pension income from the public component would act as a base upon which the retirement income from the assets accumulated in the SPP would be added. This would provide some certainty with respect to the base benefit along with the opportunity to have higher benefits from higher contributions and/or investment returns. However, the contributory pension system should also be designed in consideration of the design of the non-contributory pension that will serve as a universal safety net in order to ensure that the appropriate incentives to contribute are in place.

In building a coherent system, several design aspects, all of which are discussed in turn here, will need to be carefully considered: the benefit formula for the public component; the minimum and maximum pension; the survivor and disability pensions; how contributions will be split to finance each component; and how to implement the transition from the old system to the new one.

Benefit formula for the public pension component

The formula to calculate the pension benefits from the public system needs to be defined in a way that encourages individuals to contribute and to ensure the continued financial sustainability of the system. First, it is important that individuals have access to a contributory pension even if they have a relatively short career. Second, the level of benefits granted needs to be closely related to the level of contributions paying for them. Third, the parameters of the system need to be able to adapt to changing demographic and economic realities.

The minimum number of years required to be eligible for benefits in the public component should be reduced to a minimum from the current 20-year requirement so that the majority of individuals contributing to the system receives a contributory pension benefit. Currently, it is estimated that two-thirds of those currently contributing will not reach the 20-year requirement. Removing, or at least considerably lowering, the minimum number of contribution years required would enable more pensioners to have an income during their retirement based on the years they have been able to contribute.

The authorities should also consider removing the maximum pension, especially in a complementary system. The current relatively low level of the maximum pension creates a disincentive to continue contributing to the system once the maximum level of benefits has been reached. At a minimum, the maximum pension should be much higher so that it only affects people at the top of the income scale.

To ensure the long-term stability of the SNP system, accrual rates should be defined in a way that is expected to be financially sustainable given the level of contributions, the macroeconomic environment and the level of life expectancy at retirement. The current level of accrual may need to be revised, as 2% for each additional year of contribution with a contribution rate of 13% is much higher than in most OECD countries ( (OECD, 2017[6]), Table 3.6). This level needs to be set to be financially sustainable based on the level of contribution going to the SNP component as well as the retirement age and remaining life expectancy.

Measures will also need to be taken in the future to ensure the long-term financial sustainability of the system. An automatic balancing mechanism will need to be incorporated in the benefit calculation formula to account for population ageing, and especially for improvements in life expectancy. There are two common approaches that have been adopted by many OECD countries over the last few years. First, the future retirement age can be linked directly to increases in life expectancy. Second, the benefit level can be reduced at a given retirement age by introducing a stability factor based on life expectancy that effectively reduces the annual accrual rate. The shortcoming of both of these approaches is that they are based on average life expectancies for the population as a whole and they do not account for the macroeconomic environment that can affect the pension system. Therefore, balancing mechanisms may also need to be incorporated into the accrual formula for benefits in addition to adjustments at retirement.

Minimum pension

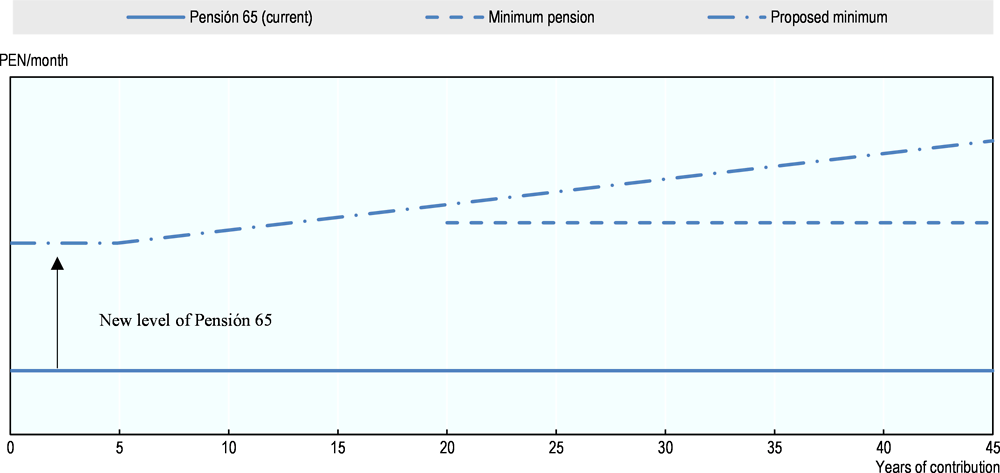

In order to encourage contributing throughout the career, the minimum level of pension should increase based on the number of years of contribution so that individuals can see merit in continuing to contribute. However, the benefit would also have to be coordinated with the safety-net Pensión 65. As every additional year of contribution should be encouraged, then the base minimum pension should be higher than the safety-net benefit. The minimum pension (i.e., the top-up to the earnings-related pension), might be financed through general taxation.

The level of the minimum pension can be set to reflect the number of years contributing, as was the case previously. In 2003, the minimum pension was PEN 145 with up to five years of contributions, PEN 173 for between six and nine years of contributions, PEN 200 for 10 to 19 years and PEN 250 for 20 years or more. The levels would have to be increased but the principle remains the same, as rewarding years of contributions can only encourage participation in the pension system.

The minimum pension could apply to the combination of income from the SNP and SPP components, in which case it has to be financed by general taxation. Currently, 20 years of contributions lead to a minimum benefit of PEN 500 per month, with 14 payments annually. This level could be maintained for 20 years of contributions, with increases based on indexation, but could be proportionally reduced for perhaps 10 years of contributions.

Furthermore, the minimum benefit could continue to increase for additional years of contributions so individuals will be able to directly see the impact of continuing to contribute on their future pension income. One possible option, for illustration purposes, is shown in Figure 4.8, where the current minimum is applicable after 5 years, and increases linearly by a certain number of soles per month for each additional year of contribution. Pension 65 and the minimum pension would complement each other for contribution-years below 5.

Figure 4.8. Illustration of a proposal for new minimum pension

Survivor and disability pensions

Improvements to the pension system to make it complementary will also need to eliminate competition and duplication with respect to the provision of survivor and disability pensions. It will need to be decided whether this coverage is offered by the public or private system or both. Survivor benefits should also be adjusted to reduce cross-subsidisation and reduce disincentives to participate in the labour market.

Several arguments can be made for having the private sector provide survivor and disability coverage. First, the mechanism through which this insurance is currently offered in the SPP has been successful in improving the transparency of the related costs. Second, given that premiums established by insurance companies are frequently updated, the sustainability of the system can be ensured as the premiums should reflect the actual cost of providing benefits. In the case of supplementary labour insurance (SCTR), this would also help to align the incentives of employers in risky occupations with those of their employees to reduce the risk of accidents.

If maintaining only the private provision of survivor and disability insurance, the process under SISCO could easily be expanded to cover all affiliates of the pension system, with the insurance premium paid as an addition to the pension contribution, as is currently the case in the SPP. The collective insurance established under SISCO has successfully led to an increase in the transparency and management of survivor and disability insurance and claims. It allows the participating insurance companies to operate as co-insurers for the disability and survivor coverage and establishes a single price for this coverage for all pension affiliates. Furthermore, the collective bidding process used to set this price has helped to keep the cost of this insurance at competitive levels.

The insurance premiums established under SISCO are updated every two years through the collective bidding process. In this way, the premiums reflect recent claims experience and therefore the system can be sustainable in the long-term as the parameters can be updated to account for demographic, biometric, and economic realities. If this coverage is fully provided by the insurance companies, however, the premiums would need to be increased as the level of capital accumulated in the accounts would be lower. Normally, this could be offset by diverting the proportion of the contributions to the SNP that intend to cover survivor and disability pensions to go towards the insurance premium.

Nevertheless, another option would be for the public system to retain the provision of the survivor and disability coverage for the portion of benefits that continue to be paid by the public system. For this solution the public and private sector would be responsible for the disability and survivor coverage of their respective proportions of expected pension income. The main advantage of this option is that the public sector retains the social policy element for survivor and disability coverage. The main disadvantage is that premiums under the public system are not likely to be regularly updated to reflect the actual risk, and if contributions are insufficient the additional cost will be borne by the public treasury.

However, for the provision of SCTR insurance for risky occupations, a decision needs to be made whether this should be provided by the public or private sector, as the two are in direct competition under the current system. SCTR insurance is largely provided by private insurance companies currently, with the ONP tending to insure higher-risk employers who cannot find a good deal in the private sector. Having this coverage provided only by the private sector would help to ensure that the premiums charged relate directly to the risk exposure for a given occupation and employer. Forcing employers to purchase insurance in the private sector that reflects their risk exposure could encourage them to take measures to improve the safety of their employees in order to pay lower premiums. Nevertheless, the ONP may still have an important social supplementary function to fulfil in the context of workers in risky occupations that the private sector does not cover because the risk is too high for the premium to be affordable.

The benefits should be defined in a way to reduce the subsidisation of benefits for couples by single individuals and preserve incentives for the surviving spouse to participate in the labour market, regardless of whether the public or private systems provide the survivor benefits. As such, the pension benefit of a single individual should be higher than pension benefits for couples entitled to a survivor pension, and the survivor pension should not be paid permanently to surviving spouses of working age (OECD, 2018[5]).

Split of contributions

The design of the new complementary system will need to define how the current old-age pension contribution of 10% of wages should be split between the public PAYG system and the privately managed individual accounts. To smooth the transition to the new system, one option to consider by the Peruvian authorities could be based on the existing flow of contributions going to each system at the time of the split, thereby maintaining the same cash flows into both systems and requiring no additional financing from the public treasury to cover current entitlements in the public system. Over the three-year period from 2015 to 2017, Table 4.4 shows that currently nearly three-quarters of total contributions to the system have been going to the SPP, while one-quarter has been going to the ONP. Therefore, in order to maintain the existing cash flows at a relatively constant level, the contributions under the new system could be established at 2.5% to 3% of wages for the public system and 7% to 7.5% of wages to the private system. Furthermore, AFPs would have to compete for the contributions to the SPP coming from people that were previously only in the SNP.

Table 4.4. Proportion of contributions to the public and private pension systems

|

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

SPP |

73.8% |

73.3% |

72.6% |

|

SNP |

26.2% |

26.7% |

27.4% |

Note: SNP figures represent the total 13% contribution. SPP figures represent the 10% mandatory contribution plus voluntary contributions.

Source: ONP; SBS.

Implementation

The improved pension system will need to define how the new rules of the complementary system will apply to those currently contributing to either system. There are two options to handle the transition from the current pension system to the improved complementary one:

1. All affiliates currently in the system continue to accrue benefits under the current rules and only new affiliates join the new complementary system;

2. Current affiliates retain the pension rights they have accumulated up to the introduction of the new system, and the new rules apply to all current and new affiliates for all future contributions to the system.

The second approach would minimise the implementation costs for Peru, and avoid a dramatic change in replacement rates under the public system when the new affiliates reach retirement.

Mexico provides an example of the problems of taking the first approach, which they did when moving from a public DB system to a system based on funded individual accounts. Workers who had entered the pension system just after the reform could expect a replacement rate of up to 60 percentage points lower compared to workers retiring a year earlier under the old DB formula.

With an immediate transition to the improved complementary system, setting the split of contributions to at least maintain an equivalent flow of contributions into each of the public PAYG and funded private component will ensure that the PAYG component would have the resources to cover most of its liabilities. As contributions going into the PAYG public component would be roughly the same as they are today, they should be sufficient to continue to pay current beneficiaries. The automatic mechanisms to adjust pension parameters and pension benefits to the macroeconomic and demographic realities would make the system financially sustainable going forward.

While the costs of moving to the new system can be minimised, they cannot be completely eliminated. The three main drivers of the additional cost will be:

Those currently contributing to the public system who will not achieve 20 years of contributions will now be entitled to benefits, to be funded through contributions;

Those currently contributing to the SPP who would not have been eligible for a minimum pension will now be entitled to one, to be funded with the general revenue;

The increased level of the minimum pension based on years of contribution will add a cost for the lower earners, to be funded with the general revenue.

4.5.2. Centralise the contribution management and data collection of the entire system to promote information sharing and efficiency gains

Improving the coordination and sharing of information among the institutions involved in the pension system could go a long way towards promoting the coherency of the Peruvian pension system and ensuring that the system is optimally designed to achieve its objectives.5 Indeed, the institutional framework of the pension system is crucial for the effective implementation and delivery of pensions, and a key factor in implementing the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation that describe the conditions for effective regulation. The implementing guidelines of Principle 1 on the conditions of effective regulation state that “the regulatory and supervisory system, institutional and financial market structure, and conduct of the different actors should be coherent, so that each plays a supportive and complementary role in achieving the overall objectives for the system” (OECD, 2016[7]).

Currently, in order to obtain or provide information with other institutions, the SBS must sign an Inter Institutional Cooperation Agreement. The SBS has signed two such agreements. In September 2013, they signed an arrangement with the Ministry of Labour and Employment Promotion (MTPE) that requires the MTPE to send to the SBS an electronic file every day that contains data from the employers with information on the employees choosing to enrol in the SPP. The SBS then sends this information to the AFP that has won the auction for the period so that they may contact the employees and send the SPP Registration Document (DRSPP) to complete the registration procedures and ensure that the individual is affiliated with the system. In December 2016, the SBS signed an agreement with the ONP that outlined the information to be shared in order to prevent contributions from the SPP from being misdirected to the SNP.

Since 2013, the SBS has been responding to requests by the ONP and the Ministry of Development and Social Inclusion (MIDIS) for information to determine the eligibility of their beneficiaries for their respective programmes. Around 88% of these requests relate to applications to MIDIS’s social programmes such as Pensión 65.

These procedures to share information between the SBS and other instructions involved in overseeing the pension system are very rigid and not conducive to facilitating collaboration. The Inter Institutional Cooperation Agreements require that the specific information to be shared be precisely detailed, and therefore do not allow for the information requirements to evolve or to be updated easily, and do not accommodate ad hoc requests. The procedure to update these agreements to include new information is extremely burdensome and time consuming.

All institutions that require information on the members and beneficiaries of the Peruvian pension system should have access to timely and accurate data in order to improve the efficiency of their operations and minimise the risk of procedural errors, such as the misdirection of contributions to the wrong system. The AFPs are already required to collect standardised information on the affiliate. This type of requirement could be extended for all systems, and be stored in a way that all institutions would automatically have access to the data. In addition, this would facilitate implementing the necessary controls needed to ensure the validity of the data, such as employment status from the Ministry of Labour.

One way to streamline the collection of information and make it more efficient would be to have one centralised, politically independent platform managing administration of the entire pension system, especially the collection of data and contribution management. This data collection needs to additionally ensure the security and reliability of data for the long-term. The platform AFPnet, managed by the AFPs for the private system, demonstrates the advantages of such an approach in increasing administrative efficiencies. Indeed, this platform has reduced the time to invest contributions to a minimum and manages this through the fee charged to members covering all services provided (currently 0.8% of assets under management), compared to the fee of 1.4% that SUNAT charges to collect social security contributions and taxes. This type of platform could be expanded to manage the contributions for both the public and the private system, and could incorporate validation checks that would eliminate the problem of misdirected contributions. It could be financed through a small fee charged on the contributions, and replace SUNAT as the intermediary for contribution collections for the public system. As this platform would cover both the public and private systems, it will hereafter be referred to as PensionsNet.

This platform should maintain independence and be free from the risk of governmental control. One way to accomplish this could be for the platform to be jointly owned and managed by the ONP and the AFPs, merging the mandates of the two systems. The ONP could provide oversight and define the objectives, and the AFPs could manage the operation of the platform, as is currently the case with AFPnet. PensionsNet should have the mandate to collect all of the information necessary to perform its function, such as the employer information necessary to determine whether contributions owed to the system have been paid, and should have the authority to enforce payment by delinquent employers. This would help to better align the responsibilities of the AFP with their expected role in the system and improve members’ trust and confidence that the system is working in their interest.

References

[2] Arellano marketing (2017), Presentación: Estrategias de ahorro a largo plazo de población joven y adulto mayor.

[1] Comision de Proteccion Social (2017), Propuestas de Reformas en el Sistema de Pensiones, Financiamiento en la Salud y Seguro de Desempleo.

[5] OECD (2018), OECD Pensions Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/pens_outlook-2018-en.

[4] OECD (2017), Pensions at a Glance 2017: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2017-en.

[6] OECD (2017), Pensions at a Glance 2017: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2017-en.

[7] OECD (2016), OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation, https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/private-pensions/Core-Principles-Private-Pension-Regulation.pdf.

[3] SBS (2018), Cómo ahorran los peruanos para su futuro.

Notes

← 1. However, the SBS and ONP do share information to avoid double payments to beneficiaries.

← 2. Affiliates to the SNP include only those who have made contributions since June 1999, as information before this date was not recorded.

← 3. These figures include individuals who had switched in prior months but were only reported in 2016 or 2017.

← 4. The average fee for those remaining on the fees based on contributions is 1.26%. New affiliates pay fees based on assets under management, so whether the total charge is higher or lower in the SPP will vary by member.

← 5. The institutions referred to are primarily the SBS, the ONP and MIDIS.