This chapter focuses on the accumulation phase in the private pension system, and looks at the investment strategies and results of the pension fund administrators (Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones, AFPs), as well as the competitive landscape, costs and fees, and the services that the AFPs provide to their members. The chapter proposes policy options to optimise the period of asset accumulation in the private pension component with a focus on the investment strategies and fund offering of the AFPs. It also discusses how the incentives of the AFPs could be better aligned with member interests as well as options aiming to align costs and fees in the system and promote efficient operations. 1*

OECD Reviews of Pension Systems: Peru

Chapter 6. Optimising the design of the private pension system for the accumulation phase

Abstract

The amount of assets that individuals contributing to the SPP will have at retirement is driven by the way that those assets are invested during the accumulation phase and the related costs of doing so. More needs to be done to ensure that the investment strategies are appropriate for savers and to ensure that the fees that they are paying are aligned with the cost to the AFPs of the services provided.

Investment strategies are controlled through explicit investment limits and a requirement to provide a minimum guarantee that is established with reference to a peer benchmark. However, the rules in place, particularly with respect to the default investment strategy, are not necessarily optimal for individuals, and the peer-based benchmark promotes incentives for herding in investment behaviour.

Tender mechanisms and the collective insurance scheme that were introduced with the 2012 reform have promoted lower costs and higher transparency. In addition, the AFPnet platform has resulted in significant efficiency gains. However more could be done to better align costs and fees charged as well as to align the incentives of the AFP with the interest of members. Furthermore, the expected role of the institutions involved in the system are not necessarily aligned with their responsibilities.

Several policy options should be considered to improve investment outcomes for individuals. The default investment strategy should be better suited to the interests of the average member. The performance of the AFPs should be judged according to more appropriate benchmarks. The fee structure should be performance-based and the same structure should apply to both mandatory and voluntary contributions. The minimum guarantee should be removed to reduce incentives for investment herding. Improving the disclosure and reporting of costs and fees and limiting the ability for members to frequently switch funds would help to promote better cost control in the system. Finally, the misalignment of responsibilities needs to be addressed and the financing of activities related to the system more closely linked with their function.

6.1. Investment of pension assets

The AFPs are in charge of managing the pension assets in the individual accounts of the Peruvians affiliated with the SPP. Four AFP are currently operating in the Peruvian market: Habitat, Integra, Prima and Profuturo. The newest AFP to enter the market is Habitat, which began operations in June 2013. This entry coincided with the exit of the AFP Horizonte, which was absorbed in equal parts by Integra and Profuturo in August 2013. The fourth AFP, Prima, began operations in 2005 and merged with Union Vida in December 2006.

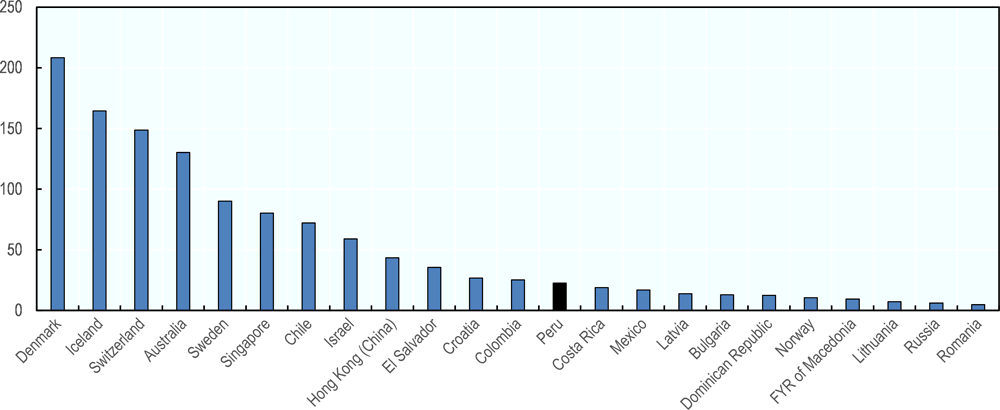

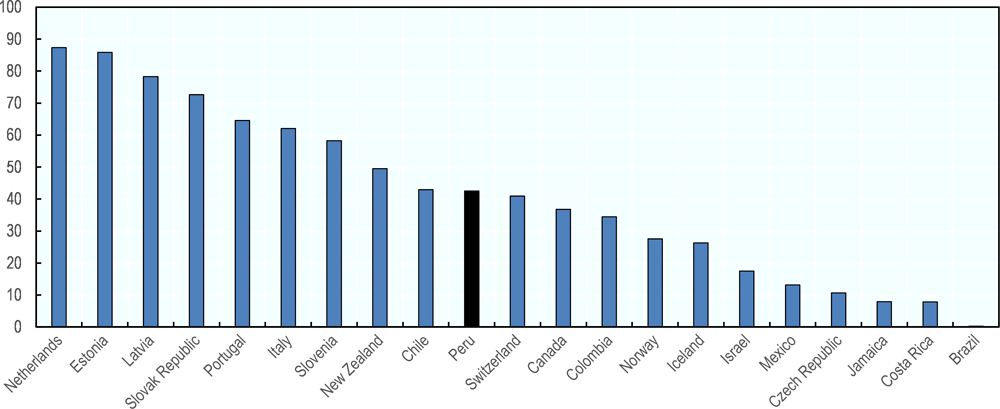

The four AFPs were managing a total of PEN 156.2 billion in pension assets (22.7% of GDP) at the end of 2017. This level is somewhat modest compared to other jurisdictions having mandatory DC-type pension arrangements, but comparable to the other Latin American countries with similar systems and maturity (Figure 6.1). Chile, El Salvador, and Colombia have higher levels of assets relative to GDP than Peru, but Costa Rica and Mexico have lower levels.

Figure 6.1. Pension assets as a percentage of GDP, 2017

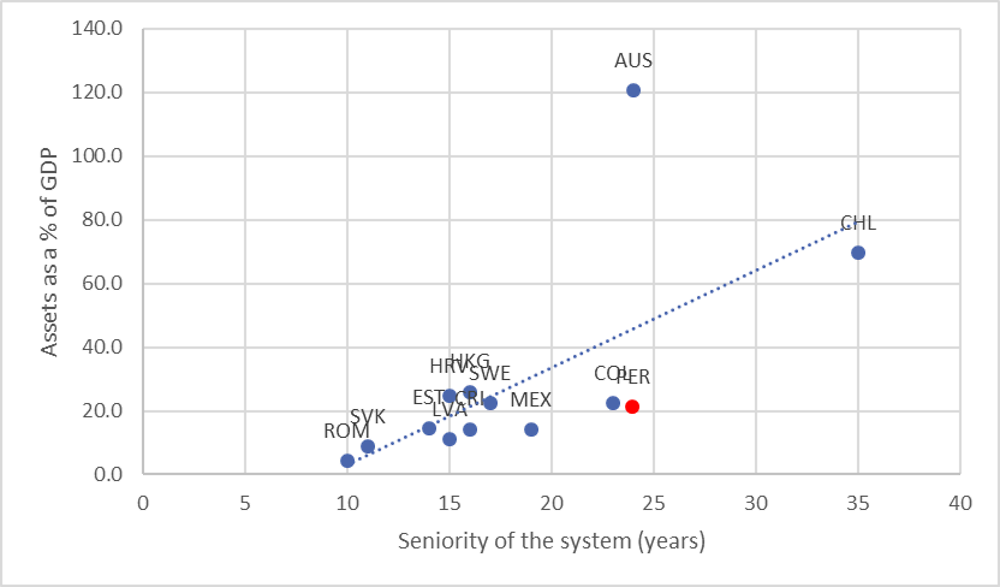

The level of pension assets would be expected to be greater in jurisdictions that have had their systems in place for longer. Figure 6.2 shows the assets in mandatory DC pension arrangements against the seniority of the system. Peru lags behind compared to the other countries shown. This is likely primarily driven by the low coverage and contribution rates of the Peruvian system that result in a lower level of assets, as well as competition with the public system. However, the asset allocation and investment performance may also play a role.

Figure 6.2. Assets under management and seniority of the mandatory funded DC pension system in selected jurisdictions

Source: OECD Global Pension Statistics.

This section explains the investment requirements that are in place and presents the asset allocation and fund performance of each AFP.

6.1.1. Available funds and investment choice

The AFPs must offer four different funds of varying risk profiles to the affiliates in the SPP (Table 6.1). Fund 2 is the default fund, and aims for an investment strategy that does not take a lot of risk while offering the opportunity for some capital appreciation. Funds 1 and 3 were introduced as alternatives to Fund 2 in December 2005. Fund 3 aims for higher capital appreciation with an investment strategy in higher volatility assets, whereas Fund 1 aims for very low volatility to preserve the existing capital in the account. The very conservative Fund 0 was introduced only in April 2016 with the investment objective of capital protection and no investment in growth assets.

Table 6.1. Investment funds in the SPP

|

Fund |

Type |

Strategy |

Target population |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Fund 0 |

Capital Protection |

Mostly cash and deposits |

Pensioners aged 65+ |

|

Fund 1 |

Capital Preservation |

Conservative and low volatility |

Pre-retirement aged 60-65 |

|

Fund 2 |

Balanced |

Medium volatility |

Default for new members |

|

Fund 3 |

Capital appreciation |

High volatility |

Not allowed for people aged 60+ |

Source: Texto Único Ordenado de la Ley del SPP.

New affiliates are automatically invested into the Fund 2 regardless of age. Once an affiliate reaches the age of 60 and 65, the AFP must automatically change their investment to Fund 1 and Fund 0, respectively, unless they request in writing to be in another Fund. Affiliates over the age of 60 are not allowed to invest in Fund 3.

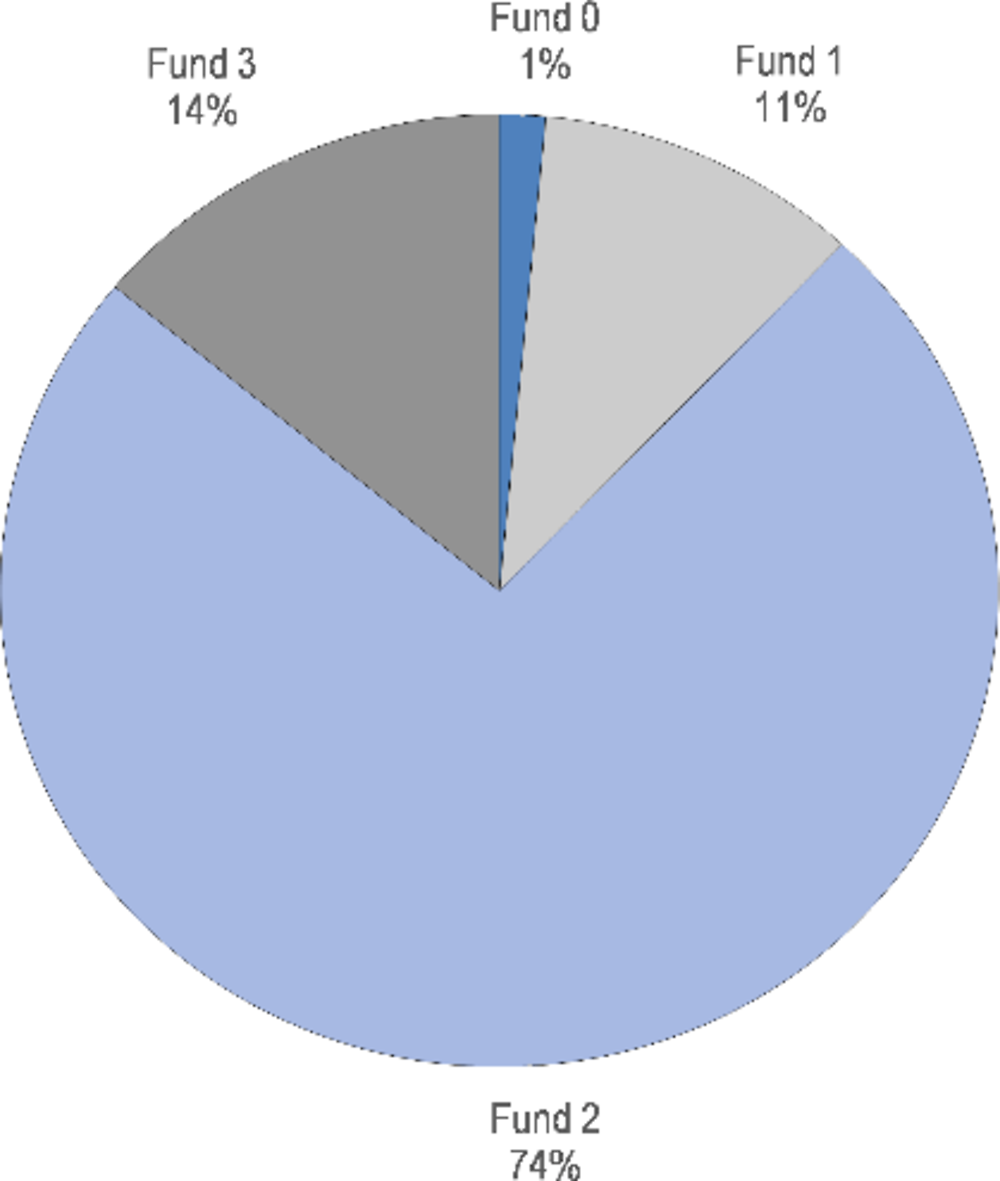

Nearly three-quarters of all pension assets are invested in the default Fund 2, as seen in Figure 6.3, implying that most members simply stay with the default investment strategy and do not opt into a different fund. However, 14% of assets are invested by under 4% of the affiliates in the most aggressive Fund 3, implying that individuals with higher levels of invested assets also tend to invest more aggressively.

Figure 6.3. Allocation of AFP assets under management by fund type, December 2018

Source: SBS.

Individuals are only allowed to invest their mandatory contributions in a single fund, although voluntary contributions may be invested differently. The AFPs must provide printed information, available in all physical branches, that details the main aspects of the SPP (investment portfolio, historical rate of return, fees, number of contributors, number of pensioners, etc.) along with the features of the different types of funds available. The AFP websites are also required to have detailed information about the different types of funds and their risk profiles.

An individual must request any change to the fund in which they invest their mandatory contributions in writing. The process to change funds takes approximately two months. Requests must be processed by the AFP within 10 days of the month following the request, and the full transfer of funds must be executed the first six days of the subsequent month.

6.1.2. Asset allocation and fund performance

Regulation imposes certain limits on investment for each of the four funds offered by the AFPs (Table 6.2). Equity investment by Fund 0 is forbidden, and only bonds and bank deposits are allowed. Equity investment in Fund 1 is restricted to only 10% of the assets in the fund. Investment in alternative instruments are allowed only for Fund 2 and Fund 3, with Fund 3 allowing for the highest level of riskier investment strategies. Derivative products are only allowed for hedging purposes or for more efficient portfolio management.

Table 6.2. Investment limits by type of fund

|

|

Equity |

Bonds |

Cash and Deposits |

Derivatives |

Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fund 0 |

0% |

75% |

100% |

0% |

0% |

|

Fund 1 |

10% |

100% |

40% |

10% |

0% |

|

Fund 2 |

45% |

75% |

30% |

10% |

15% |

|

Fund 3 |

80% |

70% |

30% |

20% |

20% |

Note: Cash and deposits includes bank deposits and short-term bonds. Only indirect real estate investment allowed. Derivative investment allowed only for hedging or efficient portfolio management.

Source: OECD, Texto Único Ordenado de la Ley del SPP.

Additional sub-limits are applicable for each fund within the categories shown in Table 6.2. A maximum of 30% of each fund can be invested in instruments issued or guaranteed by the Peruvian government, and a maximum of 30% in instruments issued or guaranteed by the Peruvian Central Bank. However, investment in Peruvian issued securities in total cannot exceed 40% of the fund. Sub-limits are also imposed for investment in alternative instruments for Fund 2 and Fund 3, shown in Table 6.3.

Table 6.3. Sub-limits on alternative investment

|

|

Private Equity |

Venture Capital |

Real Estate |

Hedge funds |

Commodities |

Natural forests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fund 2 |

12% |

6% |

6% |

4% |

4% |

4% |

|

Fund 3 |

15% |

8% |

8% |

6% |

6% |

6% |

Source: Título VI del Compendio de Normas de Superintendencia Reglamentarias del Sistema Privado de Administración de Fondos de Pensiones referido a Inversiones.

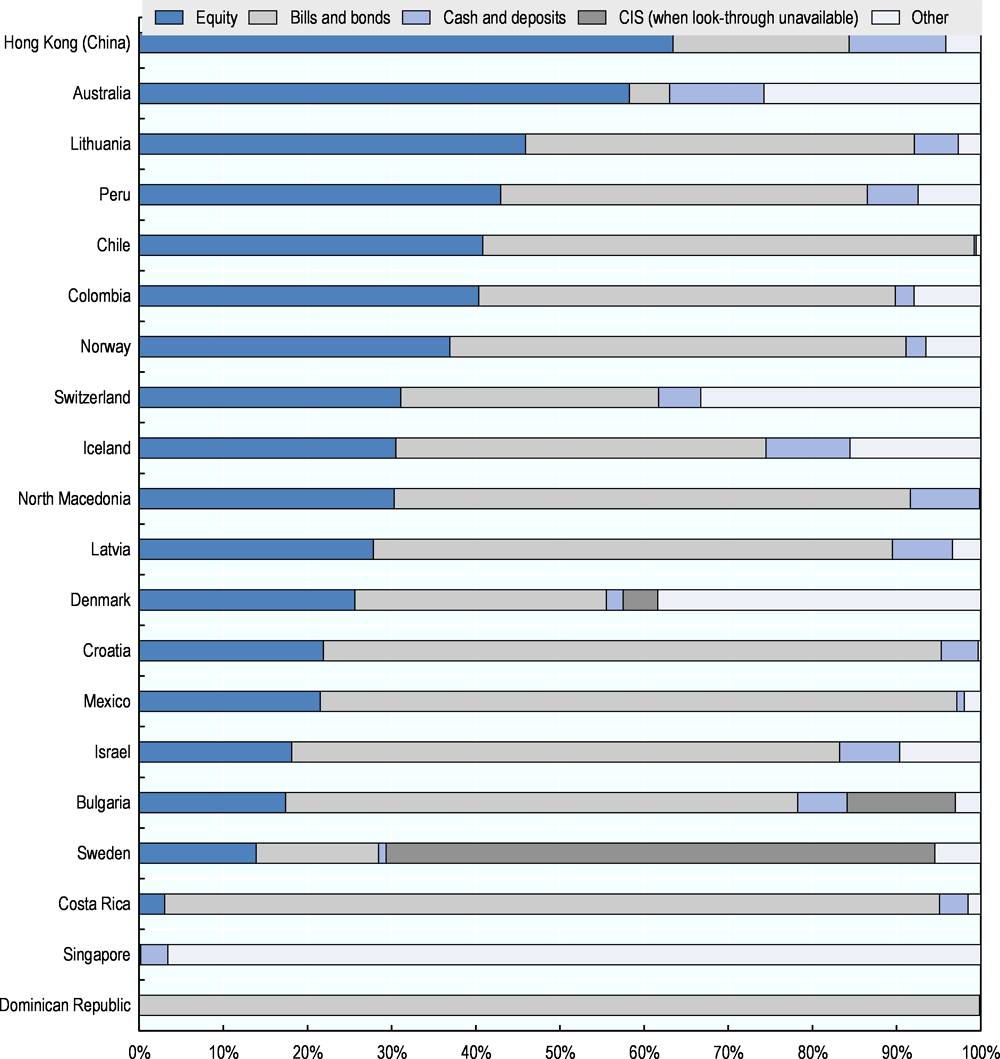

The equity and fixed income investment as a proportion of the total assets of all AFPs and fund types is 86.5%, including investments in collective vehicles, with a near equal split between the two categories. The remaining assets are similarly split between cash and deposits and alternative instruments. In an international context, Figure 6.4 shows that Peru has a relatively significant investment in equities at 43% of total pension assets, including investment in collective vehicles, compared to other jurisdictions with mandatory DC-type pension arrangements. Of the jurisdictions shown, only Hong Kong (China), Australia, and Lithuania have higher investment in equities. This could be positive in the sense that a higher average investment in equities will promote higher investment returns in the long run, increasing the level of assets that individuals are able to accumulate.

Figure 6.4. Allocation of pension assets in selected investment categories, December 2017

Note: Please see methodological notes included in OECD Pension Markets in Focus 2018.

Source: (OECD, 2018[1]).

Table 6.4 shows the asset allocation of each AFP at the end of 2018 without the look-through on collective investments.

Table 6.4. Asset allocation by fund type, December 2018

In %.

|

|

|

Equity |

Bills and bonds |

Cash and deposits |

Collective Investment |

Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fund 0 |

Habitat |

0.0 |

17.6 |

82.6 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

|

Integra |

0.0 |

0.0 |

99.9 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

|

|

Prima |

0.0 |

31.0 |

70.5 |

0.0 |

-1.6 |

|

|

Profuturo |

0.0 |

14.7 |

85.7 |

0.0 |

-0.4 |

|

|

Fund 1 |

Habitat |

3.5 |

70.5 |

1.7 |

24.1 |

-0.7 |

|

Integra |

4.4 |

71.1 |

1.1 |

23.5 |

-0.1 |

|

|

Prima |

3.4 |

76.6 |

1.4 |

18.3 |

0.2 |

|

|

Profuturo |

3.6 |

68.7 |

1.7 |

25.5 |

0.5 |

|

|

Fund 2 |

Habitat |

9.7 |

45.6 |

1.4 |

43.9 |

-0.5 |

|

Integra |

9.4 |

40.8 |

2.1 |

47.4 |

0.4 |

|

|

Prima |

9.1 |

42.8 |

1.7 |

45.5 |

1.0 |

|

|

Profuturo |

9.0 |

40.8 |

0.7 |

48.5 |

0.9 |

|

|

Fund 3 |

Habitat |

28.0 |

11.5 |

2.2 |

58.5 |

-0.2 |

|

Integra |

29.5 |

4.1 |

0.4 |

65.0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Prima |

27.7 |

3.5 |

1.0 |

67.2 |

0.6 |

|

|

Profuturo |

27.2 |

2.8 |

0.3 |

67.9 |

1.9 |

Source: SBS.

The allowable investments for the pension funds have been expanding over the last several years in an effort to increase investment in alternative instruments. In 2012, the SBS broadened the investment opportunities for private pension funds, allowing for, among others, financial instruments related to direct investment in infrastructure. In 2014, it created a more flexible process for investments where pension funds could invest in plain vanilla instruments, including direct investments in infrastructure, without prior authorization by the regulator. Previously this process could be long and complex, which limited the supply of investment instruments. According to a recent proposal, foreign infrastructure funds will be included as a new investment alternative for the portfolios managed by the AFPs. The majority of current infrastructure investment is through fixed income instruments. At the end of 2017, infrastructure investment by pension funds amounted to 8% of total assets (OECD[2]).

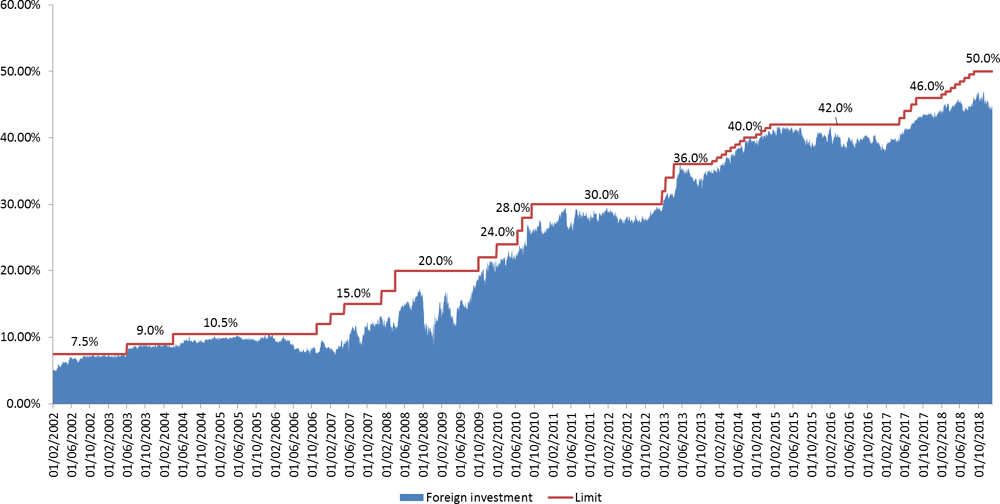

The limits on foreign investment have also been gradually expanded. The legal maximum for foreign investment is 50% of the total assets under management by the AFP. However, the Central Bank of Peru establishes operational limits for this threshold, which has been gradually increased over the last 15 years and was recently set at the maximum limit of 50%. Figure 6.5 shows the history of this increase and demonstrates that foreign investment has increased along with the investment limit. At the end of 2018, AFPs held 45% of their assets in foreign investments.

Figure 6.5. Foreign investment limits and actual foreign investment

Source: SBS.

Following the increased foreign investment limits, Peru now finds itself just below the average of selected OECD and Latin American countries in terms of the amount of foreign investment by pension funds. Figure 6.6 shows pension funds’ foreign investment for selected jurisdictions at the end of 2017.

Figure 6.6. Pension funds’ foreign investment as a percentage of total investment

Source: OECD Global Pension Statistics.

The regulation also establishes the minimum guidelines for the design of the investment policy. These address the overall investment policy for the portfolio, and includes long-term diversification of the global portfolio, tactical diversification, the global portfolio construction model, portfolio monitoring and rebalancing, liquidity, valuation guidelines for the invested instruments, guidelines for preparing and approving the policies including the responsible entity, internal limits or restrictions on investments, and the currency trading policy.

Each investment manager is responsible for the preparation of the investment policy, which must be evaluated and approved in consideration of the guidelines above. As part of this, the managers must establish a minimum, maximum and target percentage of investment for each active asset class, internal investment limits, and the acceptable levels of leverage in derivative investment, among other considerations. The SBS is responsible for reviewing and approving the investment policies and their modifications.

AFPs are required to guarantee a minimum level of real investment return that varies by fund and market performance. The level of this guarantee is established based on the average annualised real returns over the latest 36 month period for all AFPs, as described in Table 6.5. AFPs must hold a reserve to back the guaranteed return. The reserve is calculated according to each security type based on their risk classification, and is currently 0.9% of assets under management. This reserve must be invested in funds available to the affiliates. As the reserve is financed by the AFPs’ own resources, the expectation is that the incentives of the fund managers and the affiliates will be more aligned. The value of the guarantee is evaluated on a daily basis. If the minimum guaranteed return is not met, the AFP must transfer funds into the individual accounts. AFPs are also required to obtain a letter of credit from a bank equal to at least 0.5% of the assets under management to guarantee additional risks that AFP´s reserve is not sufficient to finance the minimum guarantee for the affiliates´ accounts.

Table 6.5. Minimum real guaranteed return

|

|

Minimum of: |

|---|---|

|

Fund 1

|

a) Average annualized return of the last 36 months of Fund 1 minus 2 percentage points |

|

b) 50% of the average annualized return of the last 36 months of Fund 1 |

|

|

Fund 2

|

a) Average annualized return of the last 36 months of Fund 2 minus 3 percentage points |

|

b) 35% of the average annualized return of the last 36 months of Fund 2 |

|

|

Fund 3

|

a) Average annualized return of the last 36 months of Fund 3 minus 4 percentage points |

|

b) 25% of the average annualized return of the last 36 months of Fund 3 |

Source: SBS.

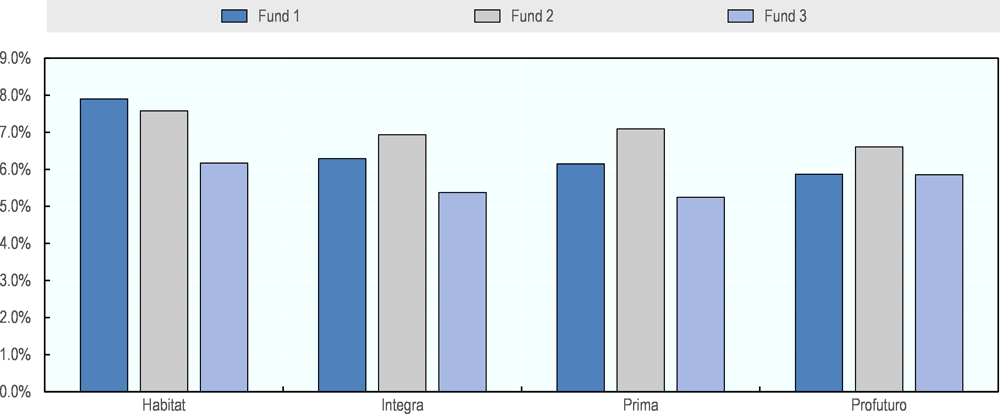

The average return over the last five years has not varied widely across AFPs for any given fund type. Figure 6.7 shows the five-year nominal returns for each fund and AFP. Fund 3 has not managed to outperform Fund 2 for any AFP, despite having a more aggressive risk profile. Returns across AFPs also do not vary widely, though Habitat has outperformed all other AFPs for every fund.

Figure 6.7. 5-year average nominal returns by AFP and fund type

Source: SBS.

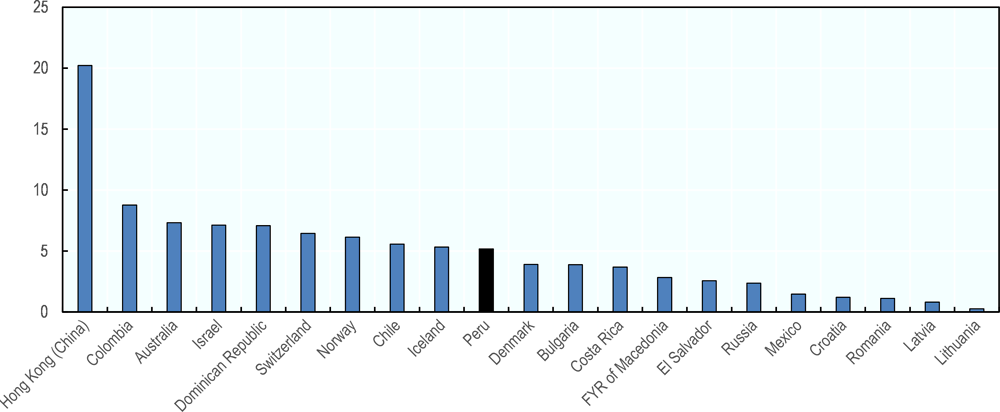

Globally, the investment return on pension assets in Peru compares well to those realised in other jurisdictions. The real annual return in Peru in 2017 was 5.2%, compared to the OECD average of 4.0%, or 6.6% average weighted by pension assets. For comparison, Figure 6.8 shows the real returns on pension assets in 2017 in selected jurisdictions having mandatory DC-type pension arrangements. Here again, Peru seems to be doing fairly average in terms of investment performance.

Figure 6.8. Annual real investment rates of return of pension assets, net of investment expenses

Note: Please see methodological notes included in OECD Pension Markets in Focus 2018.

Source: (OECD, 2018[1]).

Nevertheless, average real returns have lagged somewhat behind other countries over the last five to ten years, achieving only 2.4% and 1%, respectively (Table 6.6). However, the average annual real returns, net of expenses, that the system has delivered over the period from 2002 to 2018 is higher at 5.0%.

Table 6.6. Nominal and real geometric average annual investment rates of return of pension assets over the last 5, 10 and 15 years

In percent.

|

|

Nominal |

Real |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

5-year annual average |

10-year annual average |

15-year annual average |

5-year annual average |

10-year annual average |

15-year annual average |

|

Australia |

9.6 |

4.9 |

6.7 |

7.5 |

2.5 |

4.2 |

|

Dominican Republic |

10.3 |

11.5 |

.. |

7.3 |

7.0 |

.. |

|

Costa Rica |

8.8 |

8.2 |

.. |

6.4 |

3.7 |

.. |

|

Israel |

6.0 |

5.5 |

.. |

5.9 |

4.0 |

.. |

|

FYR of Macedonia |

6.2 |

5.0 |

.. |

5.7 |

3.3 |

.. |

|

Romania |

6.4 |

9.5 |

.. |

5.5 |

6.2 |

.. |

|

Switzerland |

4.9 |

3.0 |

3.9 |

5.1 |

3.0 |

3.5 |

|

Iceland |

7.1 |

5.6 |

8.1 |

4.8 |

0.8 |

3.2 |

|

Bulgaria |

4.7 |

1.6 |

4.5 |

4.7 |

-0.4 |

0.9 |

|

Denmark |

5.3 |

5.8 |

6.3 |

4.6 |

4.4 |

4.7 |

|

Norway |

7.0 |

5.3 |

6.7 |

4.6 |

3.2 |

4.7 |

|

Chile |

7.5 |

5.1 |

7.4 |

4.0 |

2.0 |

4.1 |

|

Lithuania |

4.8 |

.. |

.. |

3.7 |

.. |

.. |

|

El Salvador |

3.4 |

3.8 |

.. |

2.7 |

2.1 |

.. |

|

Colombia |

7.0 |

10.7 |

11.7 |

2.5 |

6.3 |

6.9 |

|

Hong Kong (China) |

5.3 |

.. |

.. |

2.4 |

.. |

.. |

|

Peru |

5.5 |

4.1 |

8.0 |

2.4 |

1.0 |

5.0 |

|

Latvia |

2.9 |

2.6 |

3.5 |

2.0 |

0.5 |

-0.5 |

|

Mexico |

4.8 |

6.2 |

.. |

0.7 |

1.9 |

.. |

|

Russia |

7.1 |

.. |

.. |

-0.5 |

.. |

.. |

Note: This table is based on the annual nominal and real net rates of investment return reported in (OECD, 2018[1]). Please refer to the notes of these statistical annexes in that publication for more country-specific notes. The 5, 10 and 15-year annual averages are calculated over the periods Dec 2012-Dec 2017, Dec 2007-Dec 2017 and Dec 2002-Dec 2017 respectively, except for Australia (June 2012-June 2017, June 2007-June 2017 and June 2002-June 2017).

Source: (OECD, 2018[1]).

6.2. Cost and services of the AFPs

Reforms to the Peruvian pension system have introduced measures aimed to increase the competition among AFPs and insurance providers and to reduce the fees charged to pension affiliates. For the AFPs, two main measures have been implemented. First, a tender mechanism was introduced to assign the enrolment of new affiliates to the system, and second the fee structure was changed from one charging per contribution to one charging on assets under management. These changes have promoted competition and fees have come down on average, but fees could come down further. The number of members switching AFPs is also on the rise.

The platform that administers the contributions of members, AFPnet, has been very successful in increasing the efficiency of administering contributions and tracking potential employer debt. However, AFPs lack the resources needed to be able to enforce the payment of contributions owed, which is a huge shortcoming in the effective operation of the pension system.

The introduction of the collective insurance scheme SISCO for survival and disability insurance has been successful in bringing consistency and transparency to the provision of this insurance. However, AFPs remain the face of the system, even for services they are not directly responsible for such as the provision of insurance and decisions around payments that are made to individuals.

This section discusses in more detail the measures that have been introduced and looks at evidence of their effectiveness in making the SPP more competitive and efficient.

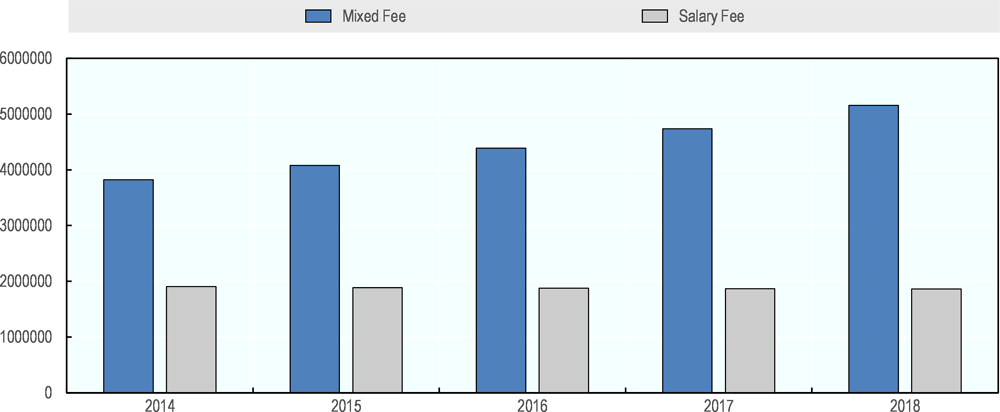

6.2.1. Management fee structure

The reforms of 2012 modified the allowed fee structure that AFPs charge to members, moving from a per-contribution charge based on salary to a charge levied on the assets accumulated in the individual accounts. The change in fees is being gradually implemented over time. Existing affiliates were automatically transitioned to the new fee structure unless they explicitly opted to remain with the old structure. All new affiliates since the reform will be charged based on assets under management. Following the changes in fee structure, only around a third of the members remained on the fee structure based on salary, as seen in Figure 6.9.

Figure 6.9. SPP affiliates per commission structure

Source: SBS

The transition from fees on contributions to fees on accumulated assets is being managed over a period of 10 years, during which the fees take the form of a mixed commission. The maximum allowable fee charged on remuneration is scheduled to decrease over time, and the fee charged on assets apply only to contributions made since June 2013. The intention of the mixed fee structure was to avoid significant double counting of fees. The maximum commission that could be charged on remuneration over this period was established as a percentage of the commission for each AFP charged in August 2012, shown in Table 6.7. Up until January 2019, all AFPs charged close to the maximum allowed limit. However, since the auction in December 2018, the participating AFPs reduced their proposed fees on remuneration to 0.0%.

Table 6.7. Reduction schedule for the maximum charge on remuneration for the mixed commission structure

|

|

% of charge on remuneration |

|---|---|

|

Feb 2013 - Jan 2015 |

86.5% |

|

Feb 2015 - Jan 2017 |

68.5% |

|

Feb 2017 - Jan 2019 |

50.0% |

|

Feb 2019 - Jan 2021 |

31.5% |

|

Feb 2021 - Jan 2023 |

13.5% |

|

From Feb 2023 |

0.0% |

The AFPs are free to establish the commission that they will charge on assets. The fees charged by each AFP under the mixed commission scheme at December 2018 and fees that were presented in the auction of December 2018 (that apply for the winner from June 2019) are shown in Table 6.8. At December 2018, the average fees charged for the mixed commission scheme were 0.63% of wage per contribution and 1.23% of assets under management. Proposed fees significantly reduced in the latest auction, with fees on wages completely eliminated and the average fee on assets falling to 0.91%. The average fee for those who stayed with the old fee structure was 1.58% of wage per contribution.

Table 6.8. Mixed fees charged by AFPs

In %

|

AFP |

December 2018 |

Auction December 2018 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fees on wage |

Fees on AUM |

Fees on wage |

Fees on AUM |

|

|

Habitat |

0.38 |

1.25 |

0.00 |

0.90 |

|

Integra |

0.90 |

1.20 |

0.00 |

0.82 |

|

Prima |

0.18 |

1.25 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

|

Profuturo |

1.07 |

1.20 |

- |

- |

Note: Fees on contribution as a percentage of wage. Fees for the auction winner will apply from June 2019. Profuturo did not participate in the last auction.

Source: SBS.

AFPs are allowed to charge different fees on voluntary contributions to the pension system, and these fees are also allowed to vary by fund type. As expected, these fees are highest for Fund 3 and lowest for Fund 0 (Table 6.9). The average spread between the lowest and highest charge is 123 basis points. However, fees charged for Fund 2 are higher for voluntary contributions than mandatory contributions by at least 25 basis points for all AFPs, despite the fact that the majority of assets are invested in Fund 2. Furthermore, fees charged for Fund 0, which is invested primarily in cash and deposits, are 80 basis points on average.

Table 6.9. Annual fees charged for voluntary pension contributions, December 2018

In %.

|

Fund 0 |

Fund 1 |

Fund 2 |

Fund 3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Habitat |

0.70 |

1.10 |

1.50 |

1.90 |

|

Integra |

0.49 |

1.15 |

1.75 |

2.00 |

|

Prima |

1.21 |

1.21 |

1.57 |

1.94 |

|

Profuturo |

0.81 |

1.21 |

2.12 |

2.30 |

Note: Fees charged for existing affiliates.

Source: SBS.

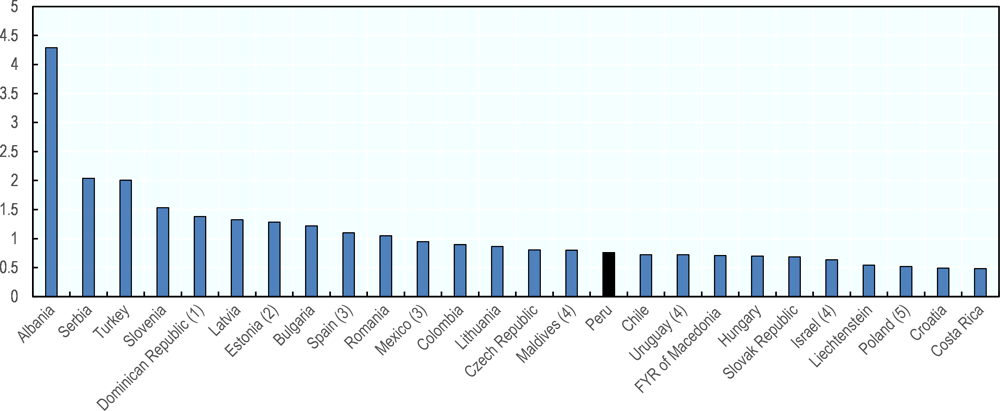

Given the different types of fee structures within the Peruvian pension system and those implemented in other jurisdictions, a direct comparison of the fee charged by the AFP is not possible. However, Figure 6.10 makes a comparison by showing the total amount of fees paid as a percentage of the total amount of assets under management for DC pension plans. In 2017, the AFPs in Peru charged members total fees amounting to 0.8% of assets under management, which included both the charges based on remuneration and the charges based on assets under management. Currently, this level is in line with the majority of the countries shown, as 17 out of 26 fall between 0.5% and 1%. Nevertheless, as the system completes its transition to fees based on assets under management, this figure can be expected to increase to the level of the fee that is being charged by the AFPs. If this remains at around 0.9%, however, Peru would still remain around the median level of fees of the countries shown.

Figure 6.10. Fees or commissions charged to members of DC plans in selected countries, 2017

Note: (1) Data refer to mandatory individual accounts only. (2) Data refer to 2015. (3) Data refer to personal plans only. (4) Data refer to 2016. (5) Data refer to open pension funds only.

Source: OECD Global Pension Statistics.

6.2.2. Competition

The pension reform passed in 2012 introduced a tender mechanism to select the AFP in which all new members are enrolled in order to promote competition among the AFPs and reduce the fees charged. The AFP proposing the lowest mixed fee receives all new affiliates to the system for a period of two years.

Since the tender mechanism was introduced, only Habitat has entered the market as a new player. Table 6.10 shows the AFPs winning each auction and the commissions proposed. Habitat won the first two auctions, and Prima won the auction held in 2016. Integra won the last auction, held in December 2018, which resulted in a significant reduction in the fees charged. From June 2019, new affiliates enrolled with Integra will be charged zero fees on their salary, and 82 basis points on assets under management.

Table 6.10. AFP auction winners and mixed fees charged

|

Mixed Commission |

2012 |

2014 |

2016 |

2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

% salary |

0.47 |

0.38 |

0.18 |

0.00 |

|

% assets |

1.25 |

1.25 |

1.25 |

0.82 |

|

Winning AFP |

Habitat |

Habitat |

Prima |

Integra |

Note: Auction fees applicable from June the following year.

Source: SBS.

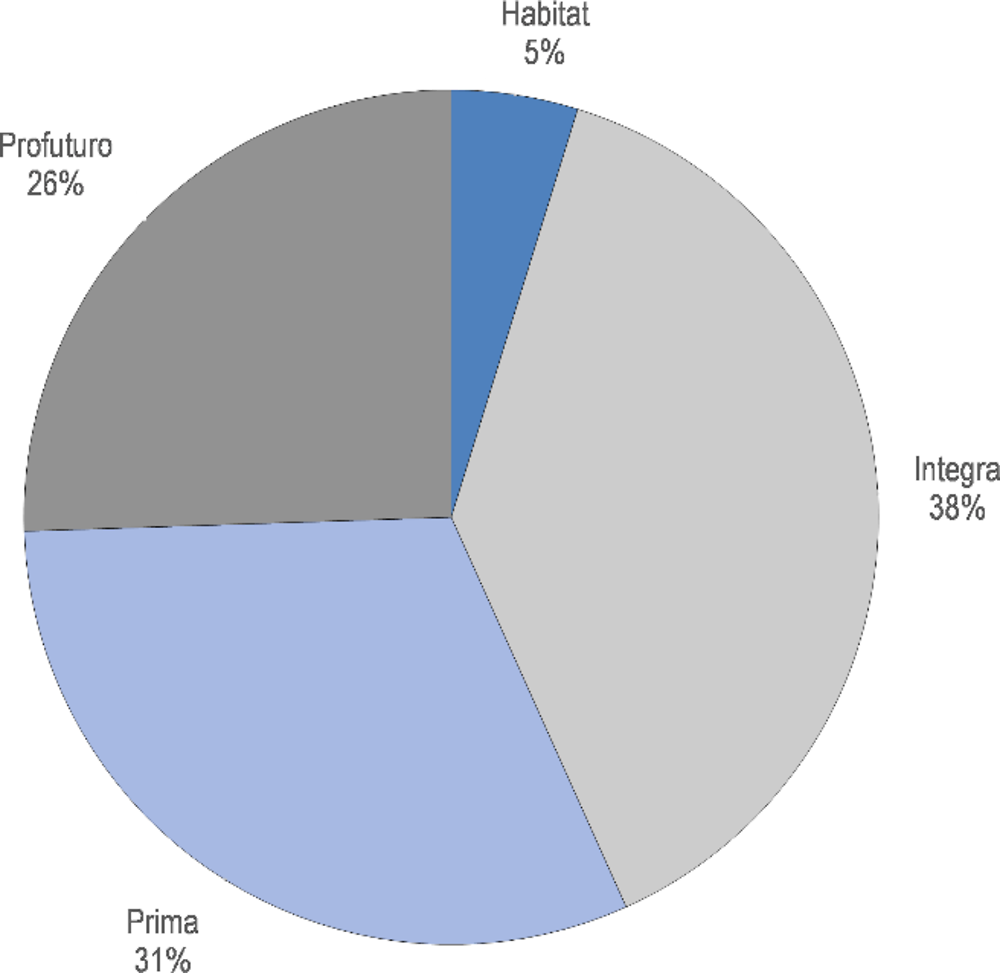

The AFPs with the largest market share are Integra and Prima, who manage 38% and 31% of the pension assets, respectively. Habitat is the smallest player as well as the newest, with a market share of only 5%, as seen in Figure 6.11.

Figure 6.11. Market share of AFPs by assets under management, December 2018

Source: SBS.

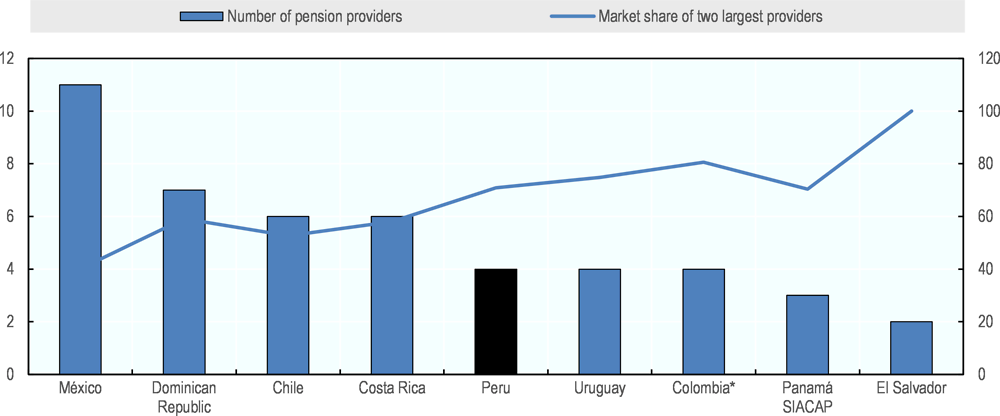

This concentration of market power among only a few providers is quite common in Latin America. Figure 6.12 shows that only Mexico has more than seven pension providers among the countries with a similar individual account pension system. Compared to the other jurisdictions in which there are only four pension providers, Colombia and Uruguay, the market is slightly less concentrated in Peru.

Figure 6.12. Concentration of market power of pension providers

Note: *December 2016. The number of pension providers is shown on the left axis and the market share of the two largest providers is shown on the right axis.

Source: Asociación Internacional de Organismos de Supervisión de Fondos de Pensiones, AIOS, Statistical bulletin, 2018.

6.2.3. Profitability and costs

The introduction of the tender mechanism seems to have been successful in its objective to promote competition among the AFP and ultimately reduce the costs of investing for members, as evidenced by a reduction in profitability following its introduction. Nevertheless, there has been only one new entrant into the business, and the AFPs overall have remained relatively profitable. Figure 6.13 shows the return on equity (ROE) for each of the AFP and for the SPP on average since 2010. Over the entire period, the return on equity averaged just under 20%. With the introduction of the tender mechanism, the ROE decreased to around 15% and has remained below 20% on average since. This is due to the fact that the AFPs’ income growth was constrained from the auctions, and from the decrease in the remuneration component of the mixed fee. Only Prima did not experience a reduction in its ROE following the introduction of the tender mechanism, though it did reduce since Prima won the third auction to receive new members.

The ROEs relationship with investment returns need to be considered in the long-term, and the two should not necessarily be correlated. For example, the ROE for all AFPs increased slightly over the year 2018 while annual real returns were negative. This is likely due to the transition from fees based on remuneration to fees based on assets under management. It would be expected that the total fees collected would be greater than before, and as the asset base to which the fees are applied grows so would the profitability of the AFP. On the other hand, ROE dropped at the beginning of 2019, and the fees charged by the AFPs are expected to reduce significantly from June 2019.

Figure 6.13. Return on Equity of the AFP

Source: SBS

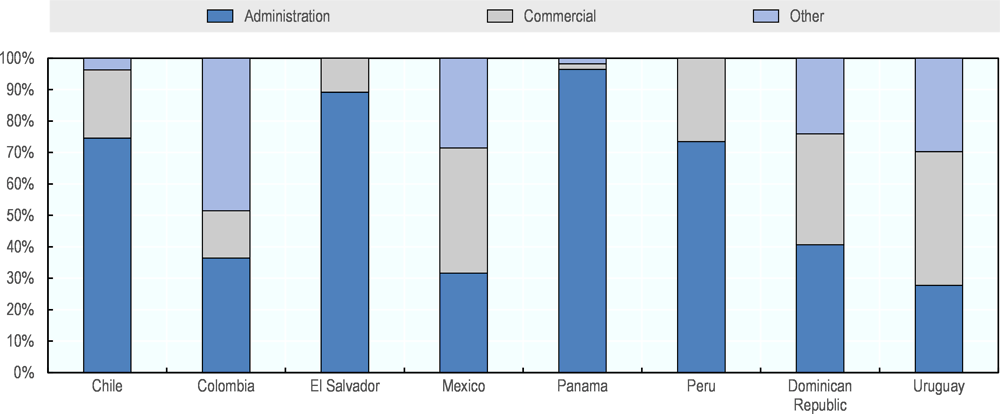

The amount that AFPs in Peru spend on commercial endeavours and marketing relative to administrative costs seems to be more or less in line with other Latin American countries. Commercial spending totals around a third of the total spent on administration (Figure 6.14). In November 2018, total operating costs of the AFPs represented 47% of income and administrative costs 35% of income on average in the SPP. Income per active affiliate amounted to PEN 190.3, and operating costs less than half of that amount at PEN 89.3.

Figure 6.14. Breakdown of operational spending of pension providers, 2017

Note: Other expenses not available for Peru.

Source: Asociación Internacional de Organismos de Supervisión de Fondos de Pensiones, AIOS, Statistical bulletin, 2018.

6.2.4. Switching between AFP

Affiliates are allowed to switch AFPs without restrictions or charges 24 months after they have been initially enrolled in the SPP. New affiliates are required to remain with the AFP that won the auction for 24 months, unless the investment performance of this AFP is particularly poor. If the return net of fees is lower than the market average, the affiliate can switch to another AFP after only 180 days. After 24 months, there are no additional restrictions on fund transfers. AFPs do not charge the affiliate fees to transfer providers. However, the sales representatives do earn commissions per transfer, and these commissions are not regulated by the SBS.

Affiliates must have all of their mandatory contributions managed by the same AFP, so if they decide to switch their entire account balance must be transferred to the new AFP. In order to change AFPs, the affiliate must request the transfer from the AFP that will receive the funds. This process takes around two months from the date that this request is made. If the request is made before the 23rd of month m, the affiliate will be registered with the new AFP in month m+1 and the funds will be transferred on the fifth working day of month m+2. If the request is made after the 23rd of month m, the registration and transfer take place in month m+2 and m+3, respectively.

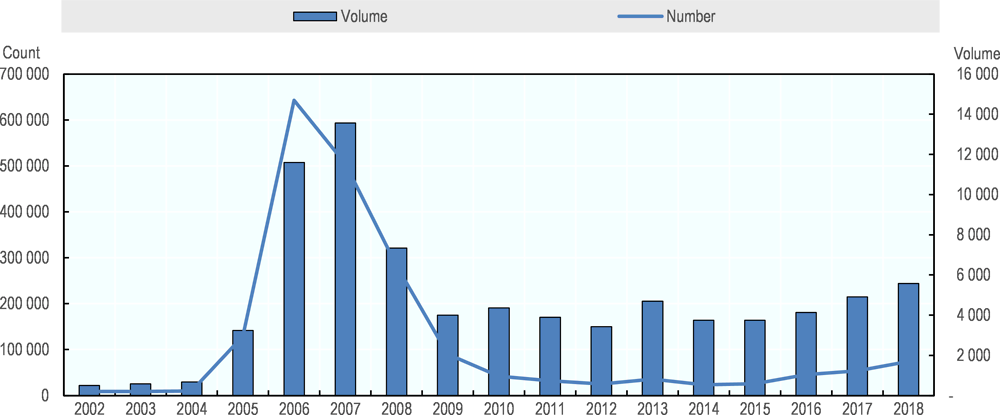

Transfers peaked in 2006 and 2007 following the liberalisation of transfers in 2005, as shown in Figure 6.15. During these two years, over 1 million affiliates transferred over PEN 25 billion between AFPs. These large volumes were driven by a commercial war that erupted among AFPs once transfers became easier and a reduction in fees from the increased competition. From 2009 to 2015 transfers were more stable, with 25 to 40 thousand members transferring around PEN 4 billion annually. This has been increasing in recent years, however, with the number of transfers in 2018 nearly tripling that observed in 2015, for a total annual volume transferred of approximately PEN 5.6 billion.

Figure 6.15. Transfers between AFPs

Note: Number, shown on the left axis, reflects the number of affiliates switching. Volume, shown on the right axis, reflects the amount of assets transferred in millions.

Source: SBS

6.2.5. Administration and services provided

AFPnet is a platform service that the AFPs provide and jointly administer. The internet-based platform facilitates the process for employers to transfer the affiliates’ contributions to the AFP, allowing this to be done with the completion of an excel file containing the employees’ identification data. The software then automatically prepares the spreadsheets, links the affiliate to the AFP and calculates the amount of their contribution. The employer is then able to make contribution payments to the affiliates’ accounts. Employers are obliged to use AFPnet to transfer their employees’ contributions, and must do so by the fifth working day of each month.

AFPnet has resulted in significant efficiency gains in terms of the administration of contributions. The time to deposit a contribution into the member’s account has been reduced from one month to one day.

AFPnet is also used to notify employers about presumed debt when the employer stops sending an employee’s contributions but has not informed the AFP that the employment relationship has ended. The employers can then confirm whether or not the debt is correct, and can now use the platform to make debt rescheduling agreements.

Apart from the management and investment of contributions, AFPs are also responsible for managing other administrative aspects for the affiliates, notably their eligibility for certain types of payments. The AFP is responsible, for example, for verifying that members are eligible to withdraw 25% of their account balance for the purchase of a first home and to assess the validity of the transaction. AFPs are also responsible for processing the application and liaising with the ONP for payment of the Recognition Bonus from the government into the account if the member is eligible for a Recognition Bond at retirement. The AFP is obliged to send all affiliates of the SPP information on the eligibility and process to obtain the Recognition Bonus, and must provide the application forms in all authorised agencies and establishments.

AFPs are also responsible for collecting the contributions of members who have opted into the SPP from employers. The AFPs are required to establish an administrative procedure to do so or to launch a legal judicial process against the employers.

The AFPs are also subject to minimum requirements with respect to the content and format of the information they provide to their affiliates about the pension system, their individual accounts and the benefit options available.

At retirement, the AFPs must inform the individual of their pay-out options and are responsible for obtaining quotes from the insurance companies. If the individual chooses an annuity option with an insurance company, the AFP manages the intermediation with the insurer, and remains the main point of contact for the individual throughout retirement.

AFPs are also responsible for the AFP Medical Committee, COMAFP, which is an autonomous body financed by the AFPs that determines the validity of disability claims. The committee is responsible for producing an evaluation and issuing an opinion as to whether a certain disability and its causes are covered by the insurance. The committee typically bases their decision on historical precedent and the official medical manual used for this purpose. There is no requirement, however, that the medical manual be regularly updated, and as a result it has not necessarily kept up with medical advances.

The COMAFP is required to provide a report with their opinion within ten days following the request by the affiliate, and must notify the SBS, the affiliate or beneficiaries, and the AFP and Insurance Company within three days of its decision. The affected parties are allowed to appeal the decision within 15 days.

The COMAFP is subject to the control, supervision and sanction by the SBS relating to the performance of its functions. It is made up of six members, of which four represent the AFP or the parent entity, and two representatives of the SBS. Despite being directly implicated in the decisions of the COMPAFP, the insurance companies are not represented on the committee. The designation of the members of the COMAFP is valid for three years, and can be renewed for a consecutive period of three additional years under certain conditions established by the SBS. Once this period has expired, a doctor may return to be a member again of the COMAFP following a period of at least three years.

6.3. Policy options

More needs to be done to promote better investment outcomes for individuals and align the incentives of the various players in the pensions system with positive outcomes for members. The following measures, implemented together, would improve investment outcomes for members, better align the incentives of the AFPs with their members, and promote more cost efficiencies in the system.

1. The default investment strategy should be adapted to provide a more optimal lifecycle approach, providing a more gradual de-risking as individuals approach retirement and more flexibility around how different types of savings are invested.

2. Independent investment benchmarks should be introduced to assess the performance of the AFPs in order to reduce the incentives for herding in investment behaviour.

3. Fees should be aligned with costs and competition promoted. This could be done by improving the disclosure and reporting on cost and fees for the AFP in order to encourage better cost control, implementing a performance based fee structure to better align the incentives of the AFPs with the interests of their members, aligning the fees charged on mandatory contributions with those for voluntary contributions, and setting limits around how often individuals can change funds and providers to avoid cost increases related to unnecessarily frequent switching.

4. The minimum guaranteed return should be eliminated and the riskiness of investment strategies controlled in a more direct manner.

5. The role of the institutions in the system and how the different components are financed should also be better aligned with their function. The central platform PensionsNet should be responsible for enforcing the payment of contributions, and be financed through a small fee charged on the contribution. Insurers should play a larger role in the decisions related to insurance in the COMAPF, and this body should be financed through the insurance premium.

6.3.1. Adapt the default investment strategy to a more optimal lifecycle approach and allow for flexibility in the default for voluntary savings

The current investment offering to members does provide a range of investment strategies to suit various degrees of risk tolerance of investors. Nevertheless, the default strategy to de-risk investment as individuals approach retirement is abrupt rather than gradual and therefore does not provide an optimal strategy as a lifecycle approach to investment. In addition, all pension savings are required to be invested in the same fund.

Provide a more gradual path to de-risk investments

The OECD Roadmap for the Good Design of Defined Contribution Pension Plans recommends that pension arrangements offer a default investment strategy, and one that ideally follows a lifecycle strategy. Lifecycle strategies are generally strategies that take more risk at younger ages and become more conservative as individuals approach retirement. Until 10-15 years before retirement, assets can be invested in riskier assets with higher expected returns because the investment horizon is long and individuals will have time to recover from any potential losses. The investment strategy shifts towards more conservative strategies when retirement is 10-15 years away in order to lock in the gains that have been earned with high growth assets and limit the risk of significant investment losses that cannot be recovered from.

The default strategy in Peru is to invest in a moderate growth strategy investing in up to 45% of equities until the age of 60, at which point assets are immediately rebalanced to a conservative strategy of mostly fixed income instruments. At 65, the normal retirement age, assets are transferred to a near risk-free strategy of cash and deposits until the individual makes a decision regarding pay-out.

While this investment strategy does de-risk the portfolio as an individual approaches retirement, it could invest more aggressively at the younger ages and it de-risks in a very disjointed manner, exposing the individual to additional risk of not being able to recover from severe investment losses.

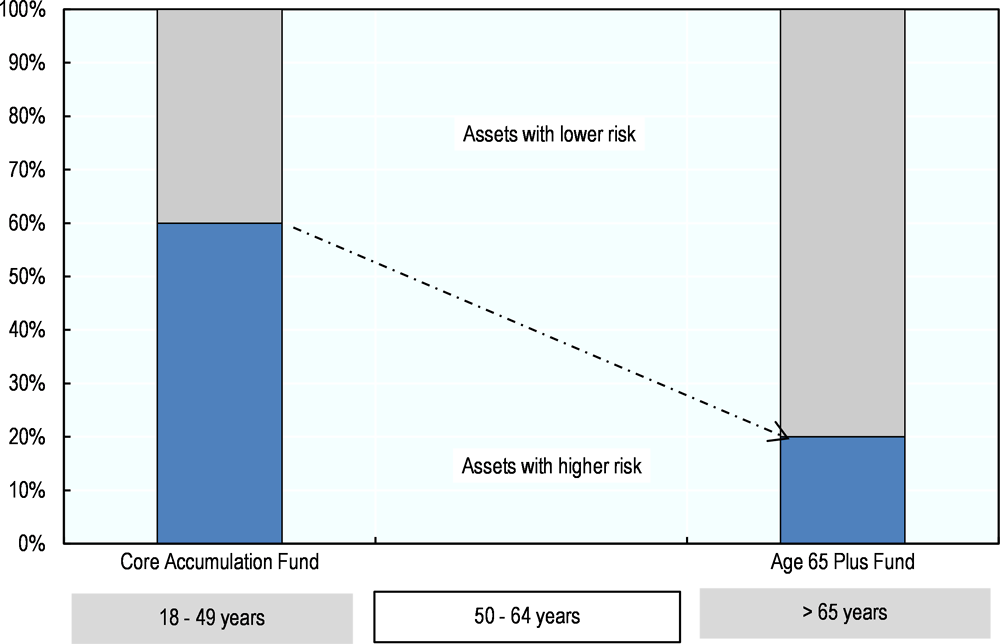

The typical lifecycle strategy employed in many pension funds allows for higher risk investment at younger ages and follows a more gradual path of de-risking, with the asset allocation gradually rebalanced as the individual approaches retirement rather than implemented all at once. The Mandatory Provident Fund in Hong Kong (China), for example, takes the approach of gradually shifting assets from a growth fund to a low-risk fund over the 15 years approaching retirement in a linear fashion (Figure 6.16).2 This type of approach aims to still allow for some level of higher growth while locking in the achieved investment returns, mitigating somewhat the risk of unrecoverable losses as people near retirement.

Figure 6.16. Risk allocation – MPFA Default Investment Strategy

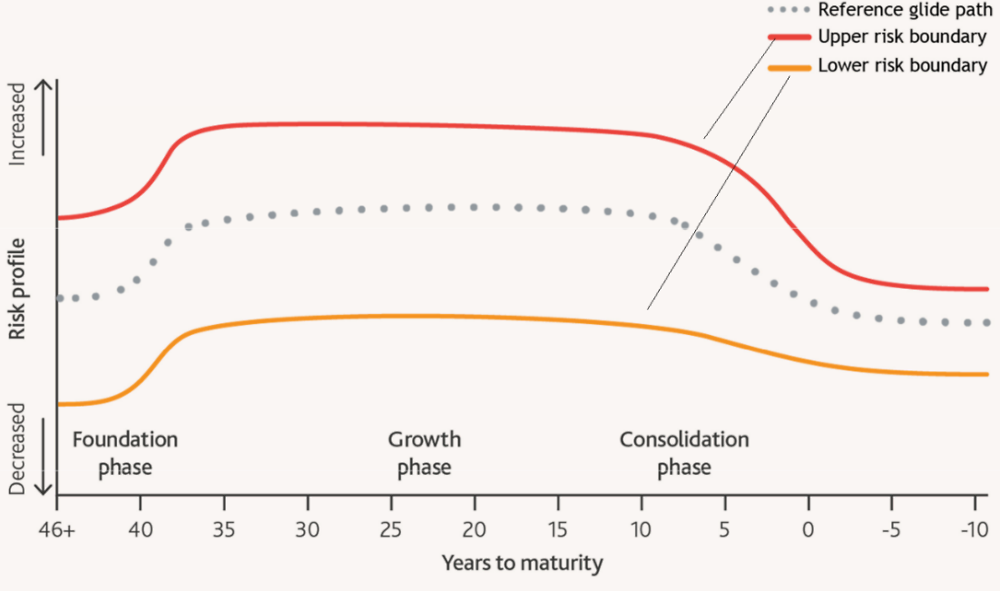

Other funds, commonly known as Target Date funds, reduce the automatic nature of the lifecycle approach and invest in a more dynamic manner along a glide path that takes into account the ages of a specific cohort, the economic environment, and the market conditions as it moves from one phase to the next. The NEST funds in the UK are an example of a target date approach. Each phase targets both a real investment return and a certain long-term volatility. Contrary to other lifecycle strategies, however, for the youngest members the NEST strategy begins more conservatively to limit losses that might discourage new savers, then builds up the level of risk from a horizon of 40 years to retirement (Figure 6.17).

Figure 6.17. Risk allocation – NEST funds

Target date funds have the advantage of more gradually linking the accumulation and the pay-out phase and having a coherent long-term perspective for investing for retirement. However, taking such an approach would limit the investment options that could be offered to members, and would require more significant changes to the current structure of the private pension system in Peru.

Allow different investment strategies for voluntary savings

More flexibility should be allowed in how individuals invest different types of savings. Individuals are currently required to invest all of their retirement savings, both mandatory and voluntary contributions, in the same AFP and fund.

Individuals should be allowed to opt for different strategies and providers for the different types of accounts to reflect their own risk preferences. This would allow them to opt for an intermediate level of risk between those defined by the funds by allocating their mandatory and voluntary pension savings to different funds. It could also allow them to diversify providers for their different types of savings.

6.3.2. Implement independent investment benchmarks to assess and compare investment performance

Basing the minimum guaranteed return for each fund on the average return of all AFPs may create an incentive for herding behaviour. This could result in similar investment strategies across all AFPs to minimise the likelihood that any one AFP’s investment returns deviates much below the average and triggers additional payments by the AFP to the individual accounts.

Indeed, when considering the correlation of real returns from Fund 2, in which most of the assets are invested, there does seem to be evidence of potential herding. Table 6.11 shows that the correlation of annualised returns, measured on a monthly basis, from January 2015 to June 2018 is close to 1 for all AFPs.

Table 6.11. Correlations of real annual returns (monthly) of Fund 2

January 2015 - June 2018.

|

|

Habitat |

Profuturo |

Integra |

Prima |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Habitat |

1 |

|||

|

Profuturo |

0.984 |

1 |

||

|

Integra |

0.996 |

0.977 |

1 |

|

|

Prima |

0.992 |

0.972 |

0.997 |

1 |

Source: Own calculations based on SBS data.

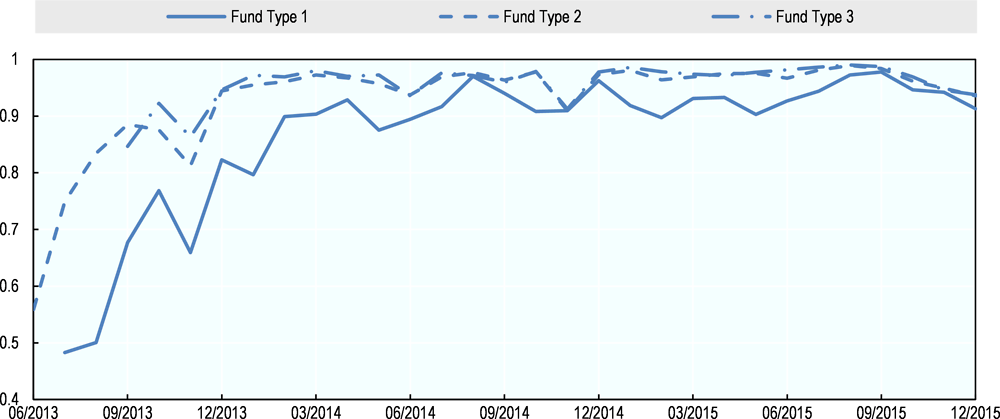

Figure 6.18 shows the evolution of the average correlations of daily returns over a given month for each fund type. The correlations in returns increased considerably from June 2013 to June 2014, though correlations tended to also be higher prior to 2013. In addition, the correlations for the different fund types have been converging.

Figure 6.18. Evolution of Monthly Average Correlation of Pension Funds Returns

Source: SBS

Correlations in investment returns may be due to the correlation of returns in similar assets or could result from similar investment strategies across AFPs. Internal studies by the SBS suggest that AFPs frequently changed their position in an asset in the same direction within a given month, with at times almost half of the assets traded within a given month being traded in the same direction by at least two AFPs. While all funds demonstrated a certain level of matching investment strategies, this effect was more significant for Funds 2 and 3. However, this could be partially explained by the lack of diversity in investment opportunities in the local market, which could necessitate similar investment strategies for a given asset allocation.

The SBS is working on the development of benchmark indicators for the AFPs, which will allow for the measurement of the relative performance of the funds against these indicators for the purpose of establishing the minimum guaranteed return. AFPs also have their own benchmark indicators for the pension funds they manage that have been established based on the actual asset classification in their portfolios and are shared with the SBS. The SBS is currently evaluating these indicators to see whether they fulfil regulatory requirements. However, any initiative to develop benchmarks should attempt to avoid herding behaviour towards the benchmarks and focus on the AFPs’ ability to outperform that benchmark on returns adjusted by risk and cost.

While individualised investment benchmarks are more appropriate for assessing the investment performance of the AFPs, the SBS should also establish a common independent benchmark for each fund that would allow for better comparability across AFPs. This benchmark should allow for the assessment of performance over the long-term, in line with the investment horizon of members. It should also allow for the comparison of the risk profile and the impact of fees and charges on overall performance.

6.3.3. Ensure charges are aligned with costs and promote competition

The introduction of the tender mechanism has been effective in reducing the average fees charged by AFPs. Nevertheless, the levels of profitability of the AFPs and the level of fees charged on assets under management indicate that there may still be room to reduce fees further. This could be done by improving disclosure requirements and introducing a fee structure that better aligns the incentives of the AFPs with those of members (OECD, 2018[6]). In addition, fees charged for accounts with voluntary contributions should be aligned with those for mandatory contributions, and frequent switching between AFPs should be limited.

Improve disclosure and reporting of costs and fees

Making costs and fees more transparent is often the primary policy tool implemented to reduce costs and fees when market mechanisms fail. Policies to improve the disclosure of fees aim to not only increase the transparency of fees charged to members, thereby increasing competitive pressure on providers, but also to help providers to better understand the fees that they actually incur in order for them to take action. Effective policies also improve the engagement of members by making the disclosures easy to understand.

The SBS, in coordination with the AFPs, has already taken steps to simplify fee disclosures and improve their transparency for members. AFPs are required to include in their communication the accumulated net returns of the pension account and the commissions that are charged, and it must be done in a way to promote simplicity and accessibility, among others.

While AFPs have to report total costs, the cost-reporting requirements to the SBS are not as comprehensive as they could be. Their reporting includes only the categories of administrative, operating, and marketing costs, and it is done following international accounting standards. However, as with most countries, they are not required to report implicit costs.3 Cost reporting requirements that have been implemented in the Netherlands provide a good example of how requiring funds to provide more granular details on their cost structure, service levels and performance can result in lower costs. In addition to administration costs, pension funds in the Netherlands also have to break out their investment costs and transaction costs. This exercise revealed that the pension providers were not fully aware themselves of all of the costs they incurred, and once this became more clear they took action based on this information to reduce costs (OECD, 2018[6]).

Nevertheless, there is a cost to increased data collection, so the relevance and usefulness of the data requested must be considered with the administrative burden to collect it. The success of the disclosure requirements in the Netherlands was, in part, driven by a pragmatic approach that the regulator took to implement the requirements gradually with increased granularity over time (OECD, 2018[6]).

Impose a fee structure to better align the incentives of providers and members

The change in fee structure from one based on remuneration to one based on assets under management does not fully align the interests of the AFPs with members and will result in lower accumulated assets for individuals at retirement. Assets will be lower because fees will be taken from the contributions rather than charged as an addition to the contributions, and in many cases, the new structure will also result in more fees paid to the AFP. Nevertheless, as the pension system in Peru is maturing, it may still be necessary to move away from the fee structure based on remuneration to cover costs as the asset base grows.

The change in fee structure to one based solely on assets under management does not necessarily align the incentives of the AFP with the interests of their clients. Fees based on assets do not provide incentives for fund managers to be more efficient, and may reward poor performance and penalise good performance. This is true because they are not linked to the relative performance of the fund compared to the market, and a fund that underperforms the market with positive returns can earn more in absolute terms than one who outperforms the market but with negative returns (OECD, 2018[6]).

Additionally, fees on assets under management (AUM) need to be set carefully. Moving from a fee based on remuneration to a fee based on AUM could potentially have a significant impact on the total amount of fees that members will pay to the AFPs and the pension pot they will ultimately accumulate if the level is not set correctly. Given that a fee on AUM is charged on the entire asset base in each period, the accumulated fees paid could be higher, if not set appropriately, than those charged on contributions, which are received only once. In addition, assuming that the fees based on AUM are deducted from the individual’s account and that contributions remain at 10% of salary, the individual’s assets accumulated at retirement would be lower than if they had continued paying an additional fee based on remuneration because the initial contribution would be reduced rather than having the fee charged as an addition to the contribution. Nevertheless, this higher potential cost is also a result of the need to implement the transition to the new fee structure in a gradual manner, as the AFPs lost the upfront funding for managing the assets, and initially the level assets on which the AUM fees were charged were very low. Over time these fees would be expected to gradually reduce to equalise the cost to members.

The impact of the new fee structure varies across demographic profiles. One study assessed the impact of the new fee structure in Peru using a microsimulation model with different income profiles, contribution rates and returns (Bernal et al., 2016[7]). Assuming the new fee structure does not result in lower overall fees due to increased competitive pressure, the study finds that the largest negative impact of the change in fee structure is for younger contributors and members with higher balances. Women are also more negatively affected because they are more likely to contribute and accumulate more savings. On the other hand, low-income workers end up paying less in fees under the new fee structure.

Under the new fee structure, Peru can be expected to remain it its current average position in the ranking of the level of fees if fees do not decline further (Figure 6.10). Currently, the total amount of fees charged relative to assets under management stands at 0.8%, and the fee based on assets under management charged to new affiliates will be 0.82% from June next year. If this level stays constant, Peru could be expected to remain at just under the median of the countries shown.

Policy makers should consider introducing alternative fee structures, such as performance-based fees, to better align the interests of AFPs with those of members. Performance based fees pay higher fees for higher risk-adjusted returns. Combining an appropriate investment benchmark with a performance-based fee structure would incentivise the fund managers to seek higher risk-adjusted returns with more innovative strategies. Some studies have shown that funds compensated with this type of fee structure achieve higher risk-adjusted returns than funds with AUM-based fees (Hamdani et al., 2016[8]). Furthermore, this type of fee structure would reduce the incentives for herding behaviour by providing additional compensation for over-performance.

The benchmark for performance needs to reflect the actual investment strategy of the fund and be in line with the objective of providing a pension. This benchmark should be the benchmark established by the SBS to assess the performance of each type of fund. The SBS could rely on an independent technical body to establish this benchmark.

Nevertheless, performance-based fees must be structured carefully in order to provide the right incentives to fund managers. Typically, these fee structures combine a small fixed-percentage base fee calculated on AUM combined with the variable fee based on performance. The main components include the asset base on which fees will be charged and the fee rate, the reference point for performance in order to asses ‘good’ performance, and the length of time over which this performance is calculated. The reference point can also incorporate a high watermark to avoid compensating the fund manager for previous losses (OECD, 2018[6]).

Different performance fee structures are possible to smooth the potential volatility of fees. The Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) in Japan provides one example of how to structure performance-based fees with a custodian model to smooth the volatility of fees from year to year. For this structure, the base fee references the return of a passive fund. Performance-based fees are calculated on the excess return over this passive fund. However, only 45% of the performance-based fee is actually paid to the asset manager each year, with the remaining 55% deferred to the following year. The carryover structure aims to encourage a longer-term horizon and avoid excessive payment for very high performance in one year – which is a drawback of using high watermarks – as well as the problems of clawbacks where excessive fees are taken back, which can present complications with respect to taxation (Jimba, 2018[9]).

Policy-makers could consider incorporating a performance-based fee structure with the current auction process. This could be done by basing the auction on the base fee that the AFPs would receive for achieving the benchmark returns. Other variables reflecting the value added that the AFP has to offer could also be considered. The SBS could then establish the proportion of the excess return that AFPs would receive for exceeding the benchmark returns, which would be the same for all AFPs, but could vary by fund type to align the total expected fee with the level of active management required (i.e. the highest performance fee for Fund 3). As an initial step to transition to the new structure in a smooth manner, the SBS could establish the level of the performance-based fee by solving for the amount required to match the current level of fees based on the target excess return of the funds and the expected base-fee.

This solution would address several challenges relating to the implementation of performance-based fees. Allowing the AFPs to establish their own base fees first provides a solution for having a performance-based fee structure that is compatible with the tender process. It also addresses the challenge of the communication of fees and net returns to members. Individuals could rely on the base fee as a way to compare the costs of the different AFPs, and net returns could still be calculated and communicated for members to be able to assess the relative investment performance of the AFPs. Finally, allowing for the performance-based fee to vary by fund type better aligns the fee received with the investment strategy of the fund, with higher fees paid for more actively managed funds.

Align fees on voluntary contributions with those for mandatory contributions

The performance-based fee structure proposed in the preceding section could also be a solution to align the fees of mandatory and voluntary contributions. One reason why the fees may currently differ between the mandatory and voluntary contributions is that it would be more likely for individuals to invest in the higher risk funds with voluntary contributions. With the performance-based fees, the same fee structure could apply to both because the expected fees would still be higher for the more actively managed funds.

In the current system, AFPs have no competitive pressure to offer lower fees for voluntary contributions. The tender mechanism only references the fees for mandatory contributions, and individuals have to invest their voluntary retirement contributions with whichever AFP they are already affiliated with.

While voluntary contributions are much less significant in size compared to mandatory contributions, the fees on voluntary contributions should also be addressed. For voluntary contributions, AFPs can charge different levels for different funds, which is justified as the higher growth funds could be expected to involve more active management. Nevertheless, on average we would expect that fees on voluntary contributions should resemble those charged for the mandatory contributions. This is not the case, and in fact the average fee charged for voluntary contributions weighted by the actual asset allocation across funds is 1.74%, which is more than 50 bps higher than the charges for mandatory contributions. Furthermore, fees charged for voluntary contributions to Fund 0 range from 49 bps to 1.21 bps, which is extremely high considering that this fund is primarily invested in cash and deposits.

At worst, these higher fees will provide disincentives for individuals to voluntarily contribute to their pension account. At best, people will not even realise that they are paying higher fees on their voluntary contributions, but will not be able to accumulate as much assets as they otherwise would have.

Establish limits around frequent switching

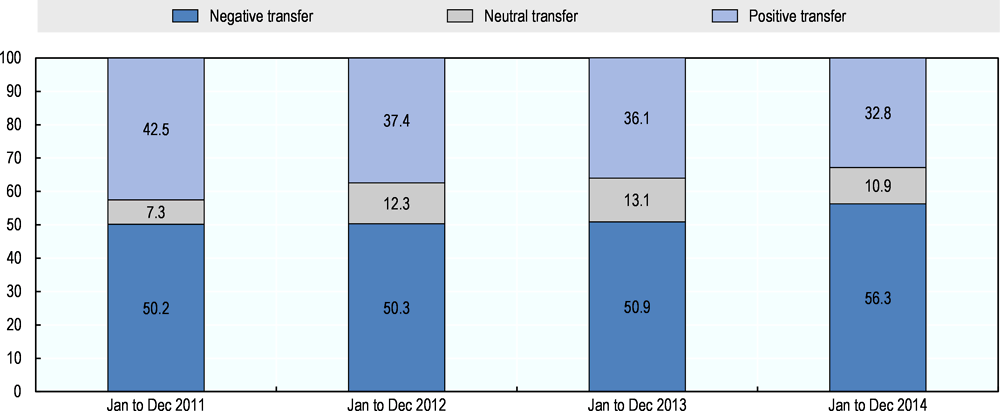

While the ability to switch providers is in theory a positive feature to promote competition, frequent switching can result in negative unintended consequences. It can encourage increased commercialisation expenditure by the AFP to convince consumers to switch, even if switching may not be in their best interest in terms of the net returns they can expect to receive. There is evidence in Mexico, for example, that over half of the individuals switching funds each year switched to a pension fund offering lower net returns (Figure 6.19).

Figure 6.19. Quality of account transfers in Mexico

Note: A negative transfer is one to an AFORE offering a lower net return. A positive transfer is one to an AFORE offering a net return at least 5% higher than that offered by the previous AFORE. A neutral one is any other offer.

Source: (OECD, 2016[10]).

Switching funds in Chile has also become a concern in recent years, where services have emerged that recommend frequent switching between funds. This has not only increased the costs to members because of the fees paid to the advisory service, but also has resulted in indirect costs as a result of a shift in the investment strategies of the funds towards more liquid assets and increased price pressure in the equity market (Da et al., 2018[11]).

Increased switching and commercial expenditure was evidenced in Peru during the commercial war of 2006 and 2007, when the profitability of AFPs fell and the number of members switching AFP skyrocketed. While the number of people subsequently reduced, there has been a strong uptick in recent years, so this trend should be carefully monitored.

In order to mitigate the negative unintended consequences of allowing members to switch between funds and providers, there should be some limits around how frequently members are allowed to switch. For example, members could be allowed to change providers only once per year, or to switch funds within a provider once per quarter. Limits could also be placed around unreasonable switching, for example from Fund 0 to Fund 3. Currently, the time it takes to process a request to change providers does mitigate the risk of frequent switching, however.

Another approach to prevent frequent switching would be to put limits on the commissions that sales representatives can receive when advising a switch. This is the approach taken in Mexico, where agents advising account transfers to another provider within 30 months are only allowed to receive 20% of the normal fee (OECD, 2016[10]). Alternatively, switching could only be allowed if fees are lower or returns higher over a reasonable period (e.g. one year).

6.3.4. Remove the minimum guaranteed return

The minimum guaranteed return defined relative to the average performance of the AFPs seems to have two main objectives. First, it should encourage AFPs to invest in a strategy that will not be harmful to members. Second, it aims to constrain the level of risk of the investment strategy, as defined through the volatility of performance. The first objective can be met with the implementation of appropriate benchmarks and a performance-based fee structure that aligns the incentives of the AFP with the members, discussed above. The second objective would be better met with a more direct approach to limit the riskiness of the investment strategies taken. This should be based on the probability of achieving a certain level of retirement income.

6.3.5. Align the responsibilities of the institutions with their expected role in the system

The responsibilities of the private institutions involved in the pension system are not always aligned with the role that they are expected to play. AFPs have the responsibility of managing many administrative aspects of the SPP, and more consideration should be given as to whether they are best placed to have this responsibility and whether they have the capability of being effective in doing so. Furthermore, the financing of the various components needs to be more closely linked to the function.

Many aspects of the operations and processes followed by the institutions to fulfil their responsibilities to the pension system are robust and efficient. AFPnet has led to significant efficiency gains in the management of contributions. The collective insurance scheme SISCO has greatly increased the transparency of the management of insurance claims and mitigated the potential conflicts of interest that existed between related capital companies.

However, with respect to contributions, AFPs are not only responsible for managing their collection and subsequent investment, they are also responsible for collecting unpaid contributions from employers. But in many cases they do not have adequate information to determine whether or not contributions are owed, particularly in the case where an individual has changed employers and has not informed the AFP. Under the proposed structure of the pension system, this responsibility would be given to the PensionsNet platform (Section 4.5.2) which would also have the power to enforce the payment of contributions and reduce the tendency of the public to blame the AFPs for procedural failures. This platform should be financed through a small fee paid on the contribution rather than through the fees charged by the AFP.

AFPs are also the sole representatives of the financial sector on the COMAFP that decides the validity of disability claims. However, the insurers are better placed with relevant expertise and experience to provide insights on recent trends and medical advances that may not be accurately reflected in the latest version of the medical manual. As such, representatives from the insurance companies should also be able to participate in the decision making process for the COMAFP, along with the AFPs and the regulator. This would also allow the insurers to play a more integrated role in the pension system, as currently they operate only in the periphery. COMAFP should be funded through the insurance premium rather than the fee paid to the AFP.

References

[7] Bernal, N. et al. (2016), How should we charge administrative fees in an individual capitalization pension system?.

[3] Comision de Proteccion Social (2017), Propuestas de Reformas en el Sistema de Pensiones, Financiamiento en la Salud y Seguro de Desempleo.

[11] Da, Z. et al. (2018), “Destabalizing Financial Advice: Evidence from Pension Fund Reallocations”, The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 2018/0.

[8] Hamdani, A. et al. (2016), Incentive Fees and Competition in Pension Funds: Evidence from a Regulatory Experiment.

[9] Jimba, T. (2018), GPIF’s New Performance-Based Fee Structure.

[4] MPFA (March 2017), .

[5] NEST (2018), Looking after members’ money: NEST’s investment approach.

[2] OECD (2018), Global Pension Statistics Project, http://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-markets/globalpensionstatistics.htm (accessed on October 2018).

[6] OECD (2018), OECD Pensions Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/pens_outlook-2018-en.

[1] OECD (2018), Pension Markets in Focus, http://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/private-pensions/Pension-Markets-in-Focus-2018.pdf.

[10] OECD (2016), OECD Reviews of Pension Systems: Mexico, OECD Reviews of Pension Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264245938-en.

Notes

← 1. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

← 2. The OECD is able to provide technical assistance regarding the development of such a strategy, as it did with the MPFA in Hong Kong (China).

← 3. Implicit costs include costs such as external asset management, look-through costs, transaction costs, platform fees etc. (OECD, 2018[6]).