This chapter discusses challenges, opportunities and emerging mechanisms for multilevel governance of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The chapter also highlights how local and regional governments are experimenting with new governance models to embrace a whole-of-society approach to the SDGs, involving both the private sector and civil society. The SDGs provide an unprecedented opportunity to align global, national and subnational priorities, however, increased capacity and awareness of the transformative nature of the 2030 Agenda are needed to reach and motivate subnational governments everywhere to use the SDG framework as a tool for the long-term transition towards sustainability. The emergence of Voluntary Local Reviews highlights the willingness among local and regional governments to engage in the global agenda and can be used as a vehicle to strengthen the localisation of the SDGs.

A Territorial Approach to the Sustainable Development Goals

Chapter 4. The multilevel governance of the Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

Introduction

Key opportunities provided by the SDGs to strengthen multilevel governance to achieve the 2030 Agenda include:

Vertical co‑ordination of priorities across local, regional and national governments for the implementation of the SDGs, including proper engagement of subnational authorities in the preparation of Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs).

Horizontal co‑ordination across sectoral departments of cities, regions and countries to manage trade-offs across policy domains in the implementation of the SDGs and ensure decisions taken or progress made in one area or SDG do not work against other SDGs.

Stakeholder engagement to promote a holistic and whole-of-society approach to achieve the SDGs, enhancing partnerships between public and private sectors, and engagement with civil society and citizens at large.

Vertical co‑ordination to align local, regional, national and global priorities

The 2030 Agenda explicitly calls for governments and public institutions to collaborate with local and regional governments in the implementation of the SDGs. A number of initiatives have emerged to raise the profile of cities and regions’ contributions to the SDGs implementation. For instance:

In February 2019, a High-level Dialogue convened by the governments of Cabo Verde, Ecuador and Spain led to the Seville Commitment whereby national, regional and local governments, their associations, civil society, academia, private sector and the United Nations underlined the importance of supporting subnational governments in implementing the SDGs (Agenda 2030, 2019).

United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) spearheaded the Local and Regional Governments Forum (LRGF) at the 2018 High-level Political Forum (HLPF) as a recurring space for dialogue between local, regional and national governments in the context of the 2030 Agenda.

The OECD Roundtable on Cities and Regions for the SDGs, launched in 2019 as a biannual policy forum, brings together local, regional and national government representatives, and major stakeholder groups to share knowledge and experience on SDGs localisation.1

The SDGs framework offers a common language for multilevel action on all three pillars of sustainable development – environmental quality, economic growth and social inclusion – to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity. Other agendas where local and regional governments are acknowledged – in addition to the 2030 Agenda – include the Paris Agreement, the New Urban Agenda by UN-Habitat, the UN summit for Refugees and Migrants and the European Consensus on Development (OECD, 2018).

At the national level, local and regional governments are not systematically engaged in the policy debate, monitoring process and implementation levers. For instance, only 34% of countries that reported to the HLPF between 2016 and 2019 have engaged local and regional governments in national co‑ordination mechanisms. For all other countries, such an engagement is either very weak (15%) or inexistent (43%) (UCLG, 2019b). The joint OECD-CoR survey highlights that only 23% of subnational authorities collaborate with national government on SDG projects, while collaboration between subnational levels (e.g. local and regional authorities) is more common for 60% of the 400+ respondents (OECD/CoR, 2019).

Strategic directions from the national level for the implementation of the SDGs can avoid a lock-in. A lock-in situation can be observed when national authorities are reluctant to “impose” agendas on local or regional governments, while those latter may seek further guidance. For example, in the Norwegian context, the national government does not have any overarching strategy for the 2030 Agenda. Instead, ministries are responsible for different SDGs from a sectoral point of view, with the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation responsible for SDG 11. At the same time, subnational authorities such as the county of Viken look at all the SDGs holistically with a territorial lens. In the Basque Country, Spain, the regional government also developed its integrated and transversal Agenda Euskadi 2030 without any national strategy to align with. In the European context, the lack of an SDGs strategy at European Union (EU) level has been noted as a barrier to define clear objectives and allocate resources while there is willingness among subnational governments to have more overarching EU strategy for the SDGs (European Union, 2019; OECD/CoR, 2019).

In practice, many regional and local governments have not yet embraced the transformative nature of the 2030 Agenda. A recent report by the European Committee of the Regions highlights that rather than an opportunity to achieve a sustainable vision of the future, the 2030 Agenda is often seen as an externally imposed burden detached from local policies, which does not come with adequate financial and other resources. This calls for a strengthened dialogue between different levels of government and greater policy coherence to develop and implement a shared vision for the future (European Union, 2019). Continued support is needed to scale up local action for the SDGs worldwide. A study by the Network of Regional Governments for Sustainable Development (Regions4SD) found that while over 90% of respondents were familiar with the SDGs, capacity constraints remain for addressing the goals, including both financial and human resources (Messias, Grigorovski Vollmer and Sindico, 2018). In Flanders, the Association of Flemish Cities and Municipalities (VVSG) considers reaching well over half (65%) of its members with support to localise the SDGs; yet, a key concern remains how to reach the other local governments (35%) less inclined to deal with sustainable development. In a similar vein, about 50% of surveyed municipalities in a study from Norway see the SDGs as favouring public sector innovation, while many small- and mid-sized municipalities perceive the lack of resources, capabilities and available time to focus on the SDGs as key barriers (Deloitte, 2018).

Moreover, there is an important challenge with regards to the time frame for the achievement of the SDGs vis-à-vis the mandate periods of different government levels. While political commitment can be tied to one legislative period, the SDGs require a longer-term perspective. Changing objectives and targets in each political cycle can be both costly and time-consuming and cause confusion among citizens and public officials (European Union, 2019). That is why some regional governments, for example the province of Córdoba and the region of Flanders, have decided to develop long-term “strategic lines” or “visions” towards 2030, or both 2030 and 2050 in the case of Flanders. In this way, priorities may be updated following elections, however, they are not reformulated from scratch. Integrating the SDGs in other administrative and policy processes, such as for example procurement decision or budgeting processes, are other ways to foster continuity.

Conducive national frameworks to support the localisation of the SDGs

An increasing number of national governments support the localisation of the SDGs in cities and regions, both through technical co‑operation and financial support. One example is Germany, where drawing on the previous experiences with Local Agenda 21, the federal government provides technical and financial support to municipalities to implement the SDGs through a multilevel government framework, the Service Agency Communities in One World (SKEW) of Engagement Global and the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). Since 2017, SKEW has supported municipalities in eight states (Länder) to localise the SDGs through the lighthouse project “Municipalities for Global Sustainability”. A key feature of this project is the involvement of all levels of government, from national through state to local level, while connecting with international governance agents like the United Nations (UN). In the city of Bonn, support from the national lighthouse project has translated into a local sustainability strategy with six prioritised fields of municipal action. The strategy will help the city to effectively localise the SDGs and to face a number of key sustainable development challenges like affordable housing, sustainable transport and maintaining the city’s green areas. It also helps to promote Bonn’s new profile as a UN City. In the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), the project enabled 15 municipalities and administrative districts to develop local sustainability strategies incorporating the SDGs and align them with federal and state ones.

Japan’s expanded SDGs Action Plan 2018 is another example of national commitment to support local efforts. The second pillar of the Action Plan on “regional revitalisation” focuses mainly on the localisation of the SDGs through its Future Cities initiative comprising 29 local governments, 10 of which were selected as SDGs Model Cities and receiving financial support by the government to implement their SDGs strategies. The initiative also promotes the establishment of SDGs governance structures by local governments following the national “SDGs Promotion Headquarters” headed by the Prime Minister within the Cabinet Office. Considered a “model city” within the selection process, Kitakyushu was one of the first cities in Japan to put in place a SDGs Future City Promotion Headquarters, headed by the Mayor. The SDGs Headquarters guides the rest of the city administration in the implementation of the SDGs. Other institutional structures put in place are the SDGs Council and SDGs Club, promoting multi-stakeholder engagement on the SDGs (see further below), and the Public-Private SDGs Platform (chaired by the mayor of Kitakyushu).

In Iceland, the governmental body overseeing and directing the work on the SDGs is the Inter-ministerial Working Group for the SDGs (hereafter the “working group”). The working group is led by the Prime Minister’s Office, in close co-operation with the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and includes representatives from all ministries, Statistics Iceland and the Association of Local Authorities. The Youth Council for the Global Goals and the Icelandic UN Association act as observers and the Youth Council further has a special advisory role to the working group. The national government upholds the importance of municipalities in the implementation of the 2030 Agenda, however, there is (as of now) no formal support mechanism at the central level. Beyond that, the Icelandic Association of Local Authorities, which is the official body representing Icelandic municipalities, has established a platform for climate issues and the SDGs at the municipal level to share experiences and build collective knowledge on experiences with the SDGs, involve municipalities and strengthen the co‑operation on the SDGs between the local authorities and the national government.

The Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development (ASviS) was established to raise awareness among the Italian society, economic stakeholders and institutions about the importance of the 2030 Agenda and to spread a culture of sustainability. This initiative dates back to February 2016, was spearheaded by the Unipolis Foundation and the University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, and currently brings together over 230 members, including the most important institutions and networks of civil society. Over 600 experts from member institutions contribute to the activities of ASviS in different working groups dealing with specific SDGs and cross-cutting issues (Box 4.1).

Box 4.1. Key activities of the Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development

Since its establishment in 2016, the Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development (ASviS) has conducted activities on six key fronts:

ASviS report: Starting in 2016, ASviS presents a report each year that documents Italy’s progress in achieving the SDGs. The report shows data and concrete policy recommendations to improve people’s quality of life, reduce inequalities and improve environmental quality. The report can be freely accessed online and aims to become a monitoring, reporting and accountability mechanism for policymakers and their commitments towards the SDGs.

ASviS SDG indicators database: ASviS has created an interactive online database, free of access that allows users to consult Italy’s national and regional progress towards achieving the SDGs. The platform has made time series available for all indicators among those selected by the UN for the 2030 Agenda, shared by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istat), as well as composite indicators calculated by ASviS for each SDG.

Institutional dialogue: ASviS contributed to the definition of the National Strategy for Sustainable Development, and periodically elaborates economic, social and environmental policy proposals addressed to the Italian government. The director of ASviS is a member of the scientific committee of the Steering Committee “Benessere Italia” within the Prime Minister’s Office. The Alliance is a member of the 2030 Agenda Working Group in the National Council for Cooperation and Development of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and of the Observatory on Sustainable Finance of the Ministry of Environment. At the international level, it represented the Italian civil society at the 2017 High-level Political Forum, is a founder of the Europe Ambition 2030 coalition, and a member of SDG Watch Europe and the European Sustainable Development Network.

Information and awareness-raising: ASviS has conducted various awareness-raising activities on sustainability issues at large and on the 2030 Agenda among public sector, businesses, public opinion and citizens. Among others, its website (asvis.it) is dedicated to each of the SDGs and its newsletter and multimedia products offer daily updates on sustainable development. ASviS is also active on social media and launches awareness-raising campaigns through them (e.g. Saturdays for Future).

Education for Sustainable Development: ASviS, together with the Ministry of Education, University and Research, has developed an e-learning course on the 2030 Agenda, available to all teachers and recently translated in English. It also launched the yearly contest “Let’s score 17 Goals” open to all schools in the country. Moreover, the Alliance focuses on higher education and co‑operates with a number of master’s courses and summer schools. ASviS is also developing projects with the Italian University Network for Sustainable Development and the National School of Administration to include sustainable development education in the adults’ learning system.

The Sustainable Development Festival: ASviS organises the annual Sustainable Development Festival which takes place throughout Italy for 17 days, corresponding to the 17 SDGs. In 2019, 1 060 events took place all over Italy, 300 of them promoted by universities involving thousands of students. The festival was one of the three finalists, picked from over 2 000 projects, in the UN SDG Action Awards.

Source: ASviS (n.d.), Alleanza Italiana per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile https://asvis.it/ (accessed on December 2019).

In Argentina, the National Council for the Coordination of Social Policies (Consejo Nacional de Coordinación de Políticas Sociales, CNCPS), responsible for co‑ordinating the implementation of the 2030 Agenda, is promoting co‑operation agreements with the provinces to promote vertical co‑ordination of the SDGs. Together with the Cooperation Agreement, the CNCPS provides provinces with an adaptation guide including methodological suggestions on the utilisation of the SDGs as a management and planning tool at the subnational level. The CNCPS also invites provinces to participate in the voluntary Provinces Report (Informe Provincias), which seeks to highlight annual progress on the adaptation of the SDGs in each territory, in relation to the SDGs under review by the High-level Political Forum every year. At the time of signature, the province had already adopted the goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda, set up focal points responsible for the local implementation of the SDGs and provided adequate resources. However, the signature was a trigger to use the adaptation guide as a key tool to ensure consistency between the provincial and national SDGs indicator frameworks. The province also committed to reporting to the CNCPS on the localisation process.

In Paraná, Brazil, the Social and Economic Development Council (CEDES) is promoting a state-wide agreement to support the implementation of the SDGs with regional associations and municipalities. In August 2019, 16 out of 19 regional associations and 248 out of 399 local governments had already formalised their commitment to the 2030 Agenda through this mechanism. The council also works to strengthen communication between governments and civil society to better engage citizens in the implementation process of the SDGs.

Other pilot cities and regions have put in place vertical co‑ordination mechanisms and enabling national frameworks for the SDGs, although these are institutionally less mature than those mentioned above. Table 4.1 provides a summary of such initiatives:

In Belgium, all governments must pursue sustainable development as a general policy objective, as granted by the Belgian constitution. Each government thus develops its own strategy for sustainable development. While information sharing is common practice, there is limited harmonisation around the substance of the strategies between governments, such as shared goals or activities. In Flanders, state and federal governments support vertical integration with municipalities through the SDGs pilot project funded by the Flemish Department of Foreign Affairs (DBZ) and the Directorate-General Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid, implemented by VVSG in 20 municipalities.

In Norway, there is no national overarching strategy document or action plan for the SDGs. However, they are integrated into key policy processes. Each ministry is assigned with a responsibility for the SDGs matching with their competencies, while the Ministry of Finance is responsible for co‑ordinating SDG reporting and to compile the yearly budget proposal presented to the parliament in accordance with the SDGs. To promote the localisation of the SDGs, the Ministry of Local Development and Modernisation has released an “expectation document”, where it is stated that the government expects regional and local authorities to include the SDGs in their planning. However, there is no established financial or technical support mechanism to support regions and cities similar to those of Germany or Japan.

In Iceland, the Prime Minister has issued a letter to all municipalities urging them to work on the SDGs. Kópavogur has been a front running city in this regard and has established a relatively close, albeit informal, working relationship with the Inter-ministerial Working Group on the SDGs. The municipality has also aligned its prioritisation exercise of goals and targets with the one previously conducted by the national government.

In Denmark, while regions and municipalities are listed among the key partners in the national government’s Action Plan for the SDGs, their role in the 2030 Agenda is not elaborated to a great extent in the document.

In the Russian Federation, the 2008 “Concept of the Long-Term Socio-Economic Development of the Russian Federation for the period up to 2020” and its revision in 2012, are the main guidelines for local and regional action in the field of sustainable development. There is room for better vertical co‑ordination through the SDGs to maximise the impact of sustainable development actions at all levels – including the co-production and use of statistics for policymaking. The Voluntary National Review (VNR) expected in July 2020 is an opportunity to engage subnational governments. Moreover, the ongoing development of a City Index by the Ministry of Economic Development provides an opportunity to actively engage cities and regions in the design and testing stages.

Table 4.1. Overview of vertical co‑ordination mechanism for the SDGs in pilot cities and regions

|

OECD Pilot |

Level of government |

Description of vertical co‑ordination for the SDGs |

|---|---|---|

|

Bonn (Germany) |

Local |

Technical and financial support from the national government (BMZ) through the “Municipalities for Global Sustainability” lighthouse project. Alignment of federal, state and local government sustainability strategies and to the SDGs is a key feature of the project. |

|

Córdoba (Argentina) |

Regional |

Formal co‑operation agreement between the provinces and the National Council for the Coordination of Social Policies (CNCPS), responsible for co‑ordinating the implementation of the 2030 Agenda in Argentina. The CNCPS provides technical support through an adaptation guide. Each province signing the agreement agrees to adapt local policies, monitoring and reporting to the SDGs. |

|

Flanders (Belgium) |

Regional |

No separate vertical co‑ordination mechanisms for the SDGs exists but all governments have to pursue sustainable development as a key policy objective as per the Belgian constitution. Municipalities enjoy technical support through VVSG’s pilot SDGs project, financed by the federal and Flemish government. |

|

Kitakyushu (Japan) |

Local |

Support by the national government through the SDGs Promotion Headquarters (Cabinet Office) and SDG Action Plan. The Action Plan includes SDGs Future Cities initiative with 29 local authorities, among which 10 SDG Model Cities receive financial support to develop SDGs Future City Plans. |

|

Kópavogur (Iceland) |

Local |

The Prime Minister has issued a letter to all municipalities in Iceland urging them to work on the SDGs. Kópavogur collaborated with the national level Inter-ministerial Working Group on the SDGs on an informal basis. Kópavogur has based its prioritisation of goals and target based on the exercise conducted previously by the national government. |

|

Moscow (Russian Federation) |

Local |

National goals set in 2008 in the “Concept of the Long-Term Socio-Economic Development of the Russian Federation for the period up to 2020” and revised by the current administration in 2012. |

|

Paraná (Brazil) |

Regional |

The state of Paraná delegated to the Social and Economic Development Council (CEDES) the responsibility to co‑ordinate the implementation of the SDGs. CEDES is responsible for horizontal and vertical co‑ordination, including with the 399 municipalities in the state. The council is also responsible for preparing a plan for the implementation of the SDGs. |

|

Southern Denmark (Denmark) |

Regional |

Co‑operation Agreement between Southern Denmark and Statistics Denmark to develop a coherent indicator framework for national, regional and local levels. |

|

Viken (Norway) |

Regional |

The Ministry for Local Government and Modernisation has released an official “expectation document” urging local and regional authorities to include the SDGs in regional and local planning and share good practices. Vertical co‑ordination largely takes place through the decentralised planning system. |

Other good practices for co‑ordinating SDGs vertically can be observed in Europe. For instance, in Italy, regional strategies for sustainable development are also expected to align with national objectives defined in the national sustainable development strategy (NSDS), which is organised around the five Ps of the 2030 Agenda: People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace and Partnerships. The Ministry of the Environment supports regional strategies both through capacity building and financial resources. In addition, since March 2018, a biannual roundtable convenes the national government and all the regions (European Union, 2019). In Spain, a High-level Group (HLG) for the 2030 Agenda, chaired by a dedicated 2030 Commissioner, has been created to support the inter-ministerial co‑ordination for the SDGs, where all Spanish ministries participate, and which has also convened the regional administrations and local entities.

The alignment potential of Voluntary National Reviews

The 2030 Agenda encourages member states to “conduct regular and inclusive reviews of progress at the national and subnational levels, which are country-led and country-driven”. The United Nations High-level Political Forum (HLPF) on Sustainable Development is mandated to follow up and review progress of the 2030 Agenda, including through state-led and thematic reviews. Countries thus present voluntary national reviews (VNRs) to the HLPF each year. The number of countries presenting VNRs has grown since the adoption of the 2030 Agenda. In 2016, 22 countries presented VNRs, 43 in 2017, 46 in 2018 and 47 in 2019 (UN DESA, 2019). However, the involvement of local and regional governments in the VNR process remains anecdotal. An annual survey by United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) and the Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments (GTF) found that only 18 out of 47 countries reviewed (38%) formally engaged local and regional governments (LRGs) in the preparation of VNRs for 2019, although this was a slight improvement compared to previous years (Table 4.2). Over the full four-year reporting cycle so far reviewed by UCLG (2016-19), LRGs have participated in the VNR preparation in 42% of cases (66 out of 143 countries). Participation has been observed to be highest in Europe (61%) followed by Africa and Latin America (50%). At the same time, 72% of the VNRs presented in 2019 mention subnational governments as key institutional actors for the SDGs, delivering policies and services crucial for the achievement of the SDGs. This points to the strong potential for upscaling vertical co‑ordination and multilevel governance of the SDGs within forthcoming VNRs, as further highlighted by another independent review of VNRs presented in 2018, which found that only 3 of the 46 VNRs included relatively advanced descriptions of localisation efforts (Benin, Greece and Spain), while many included only piecemeal illustrations (Kindornay, 2019).

Table 4.2. Local and regional governments’ participation in the preparation of VNRs, 2016‑19

Results of the annual survey by UCLG and the Global Taskforce of Cities and Local Governments

|

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

Total |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

|

|

Total countries/year |

22 |

100 |

43 |

100 |

46 |

100 |

47 |

100 |

158 |

100 |

|

LRG consulted |

10 |

45 |

17 |

40 |

21 |

46 |

18 |

38 |

66 |

42 |

|

Weak consultation |

6 |

27 |

10 |

23 |

7 |

15 |

11 |

23 |

34 |

22 |

|

Not consulted |

6 |

27 |

14 |

33 |

13 |

28 |

9 |

19 |

42 |

27 |

|

No local government organisation1 |

2 |

5 |

4 |

9 |

5 |

11 |

11 |

7 |

||

|

No information2 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

9 |

5 |

3 |

||||

1. No local self-government organisations: Bahrain, Kuwait, Monaco, Nauru, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Tonga, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates.

2. The VNRs that were not published until 28 June 2019: Cameroon, Croatia, Eswatini, Guatemala, Guyana, Lesotho, Nauru, Turkey. But for Cameroon, Croatia, Guatemala and Turkey, UCLG received the answer to the GTF Survey 2019. Those for which there was insufficient information about the LRGs: Bahamas (2018), Lichtenstein.

Note: Includes revised data for previous years based on information available up to 28 June 2019. Explanation of the categories: i) Consulted: LRGs, either through their representative national local government associations (LGAs) or a representative delegation of elected officers, were invited to participate in the consultation at the national and regional level (conferences, surveys, meetings); ii) Weak consultation: only isolated representatives, but no LGAs or representative delegations participated in the meetings, or the LGAs were invited to a presentation of the VNR (when it was finalised); iii) Not consulted: no invitation or involvement in the consultation process was issued, even though the LGAs were informed of the need to prepare VNRs.

Source: Reproduced from UCLG (2019a), “The Localization of the Global Agendas: How local action is transforming territories and communities”, https://www.gold.uclg.org/sites/default/files/GOLDV_EN.pdf

Within the pilot cities and regions of the OECD Programme A Territorial Approach to the SDGs, national associations for municipalities have been involved in the VNR process in Flanders, Germany and Iceland. The regional government of Flanders directly contributed to the Belgian VNR, while Kópavogur was featured in Iceland’s 2019 VNR as a leading example of a municipality working on the SDGs, in addition to the Association of Icelandic Local Authorities being part of the inter-ministerial working group responsible for SDGs implementation and reporting in Iceland. In Córdoba, Argentina, the voluntary provincial report requested by the national CNCPS is aligned with the SDGs under review by the High-level Political Forum every year.

The emergence of Voluntary Local Reviews

In 2018, a few pioneering cities, such as Kitakyushu and New York , presented Voluntary Local Reviews (VLRs) in the special session dedicated to local government engagement at the HLPF (see Chapter 1). The pioneering VLRs were prepared by local governments based on the Secretary General’s Voluntary Common Reporting Guidelines for VNRs and have spurred a movement of new cities and regions undertaking VLRs. UCLG finds that a wide array of subnational governments have adopted this “reporting innovation”, including regions, departments, as well as cities of all sizes. Kitakyushu, for instance, has produced such a VLR, supported by the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) Japan (see Box 4.2).

Helsinki was one of the first European cities presenting a VLR in the 2019 HLPF. The report describes how the Helsinki City Strategy connects with the SDGs, including the monitoring of their implementation. The VLR connects the city’s key strategies and operations, as well as key performance indicators, to the SDGs. These include the Helsinki City Strategy 2017-21, Carbon Neutral Helsinki 2035 Action Plan, as well as other projects and operations in relation to the SDGs. In addition, a mapping of the city’s strategic documents against the SDGs was carried out. The VLR also includes detailed analyses and reporting for the SDGs under review in the 2019 HLPF edition (e.g. SDGs 4, 8, 10, 13 and 16) (City of Helsinki, 2019).

Bristol, United Kingdom, is another city having carried out a VLR, which unlike many other reviews was produced independently from the city government. The report showcases actions by a range of actors across sectors towards the SDGs and rather than outlining achievements per goal in 2019, Bristol’s VLR describes how the city is faring on indicators related to all the SDGs since 2010 (the benchmarking year chosen).2 The report was funded through the Bristol SDGs Alliance – an informal network of city stakeholders promoting the SDGs. One of the key insights of the report is that the difference between the functional urban area of Bristol and its administrative boundaries creates challenges to both the implementation and monitoring of the SDGs at the subnational level, pointing to the need for disaggregated data and an indicator framework for different urban scales and income contexts. For example, indicators such as CO2 emissions, wage inequality or hunger measured within the administrative boundaries may not necessarily reflect the reality of people living in highly integrated towns that are part of the wider functional area (City of Bristol, 2018).

Buenos Aires, Argentina, also produced its VLR ahead of launching the city localisation plan of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Based on a long tradition of results-based management, one part of the localisation of the SDGs described in the VLR consisted in analysing the linkages to the SDGs in relation to over 1 300 initiatives, projects, policies and works of the multiannual investment plan included in the city’s comprehensive management platform. Similar to the province of Córdoba, Buenos Aires benefitted from the national government’s (CNCPS) guidance on integrating the SDGs in local policies.

Cities having undergone the experience of a VLR usually find the process helpful in in order to engage departments across policy sectors, overcoming silos and catalysing new partnerships. While favouring a flexible format for the VLRs, some cities concur that key principles for cities would be needed to make VLRs a credible tool, such as for example clarity and transparency of gaps in terms of SDGs achievements (Pipa, 2019).

Box 4.2. Pioneering Voluntary Local Reviews : The cases of Kitakyushu, Japan, and New York, United States

In July 2018, New York City launched the VLR at the HLPF. The report includes a qualitative analysis of the strategic goals and targets of the city’s strategy for sustainable development, OneNYC, compared to the SDGs, illustrating direct links between relevant indicators. When the SDGs were adopted by global leaders, the Office for International Affairs created the Global Vision, Urban Action programme to link OneNYC to the SDGs, using the shared language of the 2030 Agenda. Similarly, New York’s VLR report uses the common language of the SDGs to translate NYC’s local actions to a global audience. In addition to presenting the report, New York City used the occasion of the HLPF in 2018 to demonstrate SDGs action in practice, organising site visits for the UN community to look at projects and facilities linked to urban gardening, recycling and water treatment. The review allowed the city to identify additional opportunities to be further explored with UN agencies, member states, cities and other stakeholders. In 2019, the city presented its second VLR and committed to report on a yearly basis. The 2019 Voluntary Local Review used data from OneNYC 2050, the city’s updated comprehensive strategic plan released the same year.

The city of Kitakyushu, Japan, presented its VLR at the HLPF in 2018, developed in collaboration with the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). The report outlines progress and challenges in the work towards the city’s vision for achieving the SDGs, namely “Fostering a trusted Green Growth City with true wealth and prosperity, contributing to the world”. The VLR reflects the mayor’s drive and strong political commitment to implement the 2030 Agenda and showcase progress at the international scale. At the 2018 HLPF, the Mayor also conveyed his vision on an 18th SDG on “Culture” that should refer to creating a peaceful society by tolerating and respecting different cultures, history and traditions. The report also serves as a communication tool and reference for other cities in Japan and elsewhere that are addressing the SDGs. In Japan, Shimokawa Town and Toyama City also produced VLRs in 2018, with the support of IGES.

Sources: City of Kitakyushu and Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (2018), Kitakyushu City the Sustainable Development Goals Report 2018 - Fostering a Trusted Green Growth City with True Wealth and Prosperity, Contributing to the World, https://iges.or.jp/en/publication_documents/pub/policyreport/en/6569/Kitakyushu_SDGreport_EN_201810.pdf; City of New York (2019), 2019 Voluntary Local Review: New York City’s Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/international/downloads/pdf/International-Affairs-VLR-2019.pdf.

The role of international organisations and associations of LRGs

City umbrella networks and international institutions increasingly support the development of VLRs. For example, the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, in collaboration with DG REGIO, is producing a Handbook for European regional and local authorities to prepare VLRs to be launched at the World Urban Forum in February 2020. The handbook will be structured in two sections, including existing indicators at the local level that can support the monitoring of the SDGs, as well as a methodology section for local and regional governments to mainstream the SDGs in their strategic activities. The indicators draw on data produced by the European Commission or other institutions, while the development of proxy indicators is also underway (see Chapter 2). In addition, drawing on its initial support to Japanese cities, IGES has developed a VLR Lab to support cities undertaking the endeavour, including by offering workshops and technical support.

Local and regional government networks have been vocal and effective in pledging for multilevel governance of the SDGs and raise the profile of cities and regions in global agendas. For example, United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), C40, the Council of European Municipalities and Regions (CEMR) and PLATFORMA are actively supporting capacity building for localising the SDGs. International and national umbrella organisations are key providers of capacity development for LRGs on the SDGs. For instance, the Association of Flemish Cities and Municipalities (VVSG) has been providing intensive support to municipalities as part of their SDGs pilot project (Box 4.4). UCLG reports that the most common undertaking by local and regional government associations are awareness-raising workshops and campaigns mostly addressed to members and local and regional political leaders. A total of 67% of respondents to the Global Task Force survey in 2019 had adopted policy documents related to the implementation of the SDGs and over 75% had organised workshops to raise awareness and build capacity on the SDGs.

Various UN agencies are also active in localising the SDGs across levels of government. This is the case for UN-Habitat and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for instance, through the online platform “Localizing the SDGs”, developed in collaboration with UCLG. The platform gathers a vast range of resources, including guidance on monitoring and evaluation of the SDGs at the local level and examples of practices from across the globe to help local governments find inspirations for their own solutions.

European Union institutions have also been active in promoting the localisation of the SDGs in Europe and beyond. In the reflection paper Towards a Sustainable Europe 2030, key strengths and challenges for sustainable development in Europe are captured, and three scenarios are proposed in terms of how the EU could contribute towards achieving the SDGs (European Commission, 2019) (Figure 4.1). Which scenario will guide future action remains to be seen under the new EU governance following the May 2019 elections. Nevertheless, LRGs expect a more prominent role by the EU in the 2030 Agenda as reflected in the OECD-CoR survey which found that more than 90% of respondents are in favour of an EU overarching long-term strategy to mainstream the SDGs within all policies and ensure efficient co‑ordination across policy areas (OECD/CoR, 2019).

In 2017, the European Commission (EC) set up a High Level Multi-stakeholder Platform on the SDGs, bringing together 30 members from the EU, global institutions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other public, private and civil society organisations. The Platform contributed to the reflection paper Towards a Sustainable Europe 2030 and advocates for a multilevel and multi-stakeholder approach to the SDGs, emphasising the involvement of local and regional authorities (European Commission, 2019). The platform further has a subgroup on “Delivering the SDGs at regional and local levels”, which has found that vertical and horizontal co‑ordination needs to be enhanced in terms of governance of the SDGs (European Union, 2019).

Beyond EU member countries, the EC’s Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development (DG DEVCO) also supports the localisation of the SDGs through Decentralised Development Cooperation (DDC), focusing on partnerships between local authorities for the SDGs achievement. In EU member countries, the EC funds over 1 000 local sustainable development strategies, with mobilised investment estimated to the amount of 35 billion EUR. DG DEVCO is currently supporting 16 partnerships between cities in EU countries and cities in developing countries to promote integrated urban development in the framework of the SDGs. The objectives of the call are to: i) strengthen urban governance; ii) ensure social inclusiveness of cities; iii) improve resilience and greening of cities; and iv) improve prosperity and innovation in cities. DEVCO is also launching a similar call for proposals targeting small municipalities. This programme builds on the findings of the OECD report Reshaping Decentralised Development Cooperation (2018), which stressed the importance of partnerships between subnational governments in OECD and developing countries, beyond the traditional financial support (official development assistance, ODA). The report stresses that DDC is increasingly becoming a tool to localise the SDGs for cities both in OECD and in developing countries (Box 4.3).

Box 4.3. Key findings of the OECD work on Decentralised Development Co-operation

Cities and regions are responsible for policies that are central to the 2030 Agenda and people’s well-being, from water to housing, transport, infrastructure, land use and climate change. They can also support peer cities and regions around the world, which is what decentralised development co-operation (DDC) is about: when cities and regions from one (often developed) country partner with cities and regions from another (often developing) country.

Promoting coherence between internal territorial approaches to the SDGs and DDC activities should be a key objective. Adapting the internal territorial development initiatives and involving regional actors is therefore a good practice on DDC, observed for example in Tuscany, Italy. DDC can become a tool to address the universal nature of the SDGs and the territorial partnership model allows for best practices exchanges and peer-to-peer learning among subnational governments in developed and developing countries on the implementation of the SDGs.

The 2018 OECD Decentralised Development Co-operation report provided a set of key recommendations to national and subnational governments to improve the effectiveness of DDC activities. These included:

Use DDC to improve local and regional policies in partner and donor countries and ultimately contribute to the SDGs.

Recognise the diversity of DDC concepts, characteristics, modalities and actors.

Promote a territorial approach to DDC by fostering place-based and demand-driven initiatives for mutual benefits over time.

Encourage better co-ordination across levels of governments in promoter and partner countries for greater DDC effectiveness and impact.

Set incentives to improve reporting on DDC financial flows, priorities and practices and better communicate on outcomes and results.

Promote results-oriented monitoring and evaluation frameworks for informed decision-making and better transparency.

The 2019 edition of the OECD DDC Report has identified three key steps to make the most of DDC as a driver for implementing the SDGs:

1. Address the data challenge. With fewer than half of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members reporting on aid provided by cities and regions, a serious knowledge gap persists. To address this and raise awareness on official development assistance (ODA) reporting among subnational governments, OECD DAC members such as Belgium, France, Germany and Spain are building efforts to share best practices and strategies. Several members have begun incorporating subnational reporting in OECD DAC statistical peer reviews.

2. Promote better adapted subnational capacity and resource exchange. Subnational partnerships are often co-financed by the national government, yet they are not always aligned with local needs. How can national governments help to promote demand-driven and mutually beneficial partnerships? One solution, hosted by the EU Committee of the Regions, is a “stock exchange” initiative that acts as a matchmaker, pooling and exporting subnational resources, where needs are greatest. This includes south-south and triangular co-operation. A structured assessment of the kinds of technical assistance exchanged and the incentives for engaging in partnerships could build on findings from city networks such as United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), PLATFORMA, C40 or the Council of European Municipalities and Regions (CEMR) that have long sought to improve the co‑ordination of technical assistance exchange at the subnational level.

3. Co-ordinate across levels of government. To ensure that subnational action does not reverse national progress or vice versa, multilevel and multi-stakeholder engagement is necessary. The Voluntary National Review (VNR) process serves as an important tool to engage subnational governments in the reporting of DDC activities contributing to the SDGs. To improve the effectiveness of ODA, national and subnational governments should work together on SDG progress reviews.

Sources: OECD (2019), “Decentralised development co-operation: Unlocking the potential of cities and regions”, https://doi.org/10.1787/e9703003-en; OECD (2018), Reshaping Decentralised Development Cooperation: The Key Role of Cities and Regions for the 2030 Agenda, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264302914-en.

The OECD launched the programme A Territorial Approach to SDGs in the context of its Action Plan on SDGs. In 2016, the OECD adopted an action plan to support the implementation of the SDGs, which was welcomed by all member states at the 2016 Meeting of the Council at the Ministerial Level (OECD, 2016a). The Action Plan stresses that data on progress at the subnational level also presents opportunities to support policies tailored to regional circumstances and one of the actions of the Plan refers to the important role of LRGs in the implementation of the SDGs. In this context, the OECD launched the programme A Territorial Approach to the SDGs, which aims to support cities and regions to use the SDGs to improve local development plans, policies and outcomes.

Figure 4.1. Three scenarios for an EU contribution to the SDGs implementation

Source: Reproduced from European Commission (2019), Reflection paper: Towards a Sustainable Europe by 2030, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/rp_sustainable_europe_30-01_en_web.pdf

Box 4.4. VVSG’s support to multilevel governance of the SDGs in Flanders, Belgium

From 2017 to 2019, VVSG worked in a SDGs pilot project with the aim to integrate the SDGs in local policies and promote coherence for sustainable development. Throughout the project, VVSG provided intensive support to a first group of 20 pioneering municipalities selected based on criteria related to geography (the municipalities are spread across the provinces), size and level or experience with the SDGs.

The project had three main tracks designed to move towards a coherent, integrated and broad-based policy on sustainable development:

1. Communication and awareness-raising.

2. Politics (advocacy and awareness-raising for elected council members).

3. Policy planning.

Together with the 20 pilot municipalities, VVSG developed practical tools and guidelines to integrate the SDGs into local policy, which were then promoted and disseminated to all Flemish municipalities. Due to different local contexts, priorities and levels of ambition, there is no one-size-fits-all approach or common roadmap for all municipalities. Instead, they developed different scenarios for localising the SDGs through the mandatory local context analyses. Such scenarios range from a basic ex post “SDGs check” to using the 17 SDGs through five pillars of sustainable development as the structure of the context analysis. VVSG also promotes the carrying out of an SDG check when developing a new action or project, including analysing the positive and negative impact and potential spill-over effects across goals. Finally, VVSG is working to support municipalities in monitoring progress towards the SDGs, amongst others by developing a catalogue of indicators.

The project also contributed to multilevel and multi-stakeholder governance for the SDGs through its advisory board. The board met twice a year to provide feedback to the pilot project and consisted of external experts from organisations such as VOKA (Flanders’ Chamber of Commerce and Industry that issued a Charter on Sustainable Entrepreneurship), the province of Antwerp, VNG International (experts in strengthening democratic local governments) and the Flemish government, as well as VVSG experts.

Source: VVSG (2018), Integrating the SDGs into your context analysis: How to start?, https://www.vvsg.be/kennisitem/vvsg/sdg-documents-in-foreign-languages

Distinctive role of regions in the implementation of the SDGs

Regions have a distinctive role in the implementation of the SDGs, in particular as an intermediary actor between the national and local levels. The competencies and resources of regions depend on the decentralisation degree of countries; however, a set of three key functions in the implementation of the SDGs can be identified: i) aligning national and local priorities and ensuring consistency across measurement frameworks; ii) channelling investment towards sustainability; and iii) setting incentives to enhance multilevel governance.

Regions are privileged interlocutors between city and national governments, in particular to align policy priorities across levels of government. Administrative fragmentation (i.e. a large number of municipalities) can result in a lack of involvement of local governments in national sustainability policies and planning processes. Regions have therefore a role to play in bringing national targets to a regional context and setting up co‑ordination and dialogue mechanisms to ensure municipalities localise the SDGs. For instance, during the preparation of the first Belgian Voluntary National Review, co‑ordinated through the Inter-ministerial Conference for Sustainable Development, federal and regional governments participated actively, while municipalities could have been more directly involved. It is in this context that regions can scale up issues and concerns at the local level and also localise national priorities.

Regions can contribute to ensuring consistent measurements on SDGs across levels of government. Norway has rich databases to measure progress on the SDGs at the subnational level, for example KOSTRA that gathers municipal-level data on public health. However, regions are better placed to identify data gaps at the regional and local levels. Viken has developed a Knowledge Base, which analyses existing trends, challenges and opportunities and can set quantified targets related to the SDGs for its regional development strategy. This can help to identify data gaps for monitoring the SDGs at the subnational level in Norway, in collaboration with Statistics Norway. In Argentina, the province of Córdoba is using an adaptation guide, with methodological suggestions on the use of the SDGs as a management and planning tool at the subnational level, developed by the national government to ensure consistency between the provincial and national indicator framework to monitor the implementation of the SDGs.

Regions can gear key monetary resources in the form of public investment towards implementing the SDGs. For instance, in Southern Denmark, sectoral priorities for the new regional development strategy, including associated financing and investment mechanisms, are decided by the Regional Council. In February 2019, all regional committees started to incorporate the SDGs in their respective areas of competency, with an overall focus on SDGs 3-7 and SDGs 9-13 for the region (Region of Southern Denmark, 2019). In Viken, Norway, one of the ways forward considered by the county is aligning smart specialisation and funding for clusters with the SDGs.

Regions also play a key role in setting incentives for multilevel co‑ordination on the implementation of the SDGs. Contracts across levels of government in key sectoral priorities are a tool used by regions to advance the implementation of the SDGs. In Denmark, regions own and operate public hospitals, while municipalities are responsible for preventative care and health promotion, as well as other types of care that are not related to inpatient care, such as rehabilitation and social psychiatry. Social services handled by the municipalities further include elders care, disabled people’s care and support to chronically and mentally ill people. To promote co‑ordination across health and social services in municipalities and regional hospitals, regions and municipalities sign mandatory healthcare agreements (Frølich, Jacobsen, and Knai, 2015). In Norway, to commit all levels of government to strategic regional planning, urban growth agreements and “city packages” for transport infrastructure investment are being promoted by the government. Examples of city packages in Viken include the Oslo Package 3 (Oslopakke 3), which was formed to co-fund transport and roads in the Oslo-Akershus area and the Buskerud Package 2 (Buskerudbypakke 2), which is a collaboration between nine municipalities, the county and regional state authorities in Buskerud to improve the public transport network, aiming for zero growth in car use in the county.

Softer mechanisms, such as co‑operation agreements or multilevel dialogue platforms, are also a common tool at the regional level to implement the SDGs. The Flemish and federal government of Belgium are together supporting municipalities to implement the SDGs through the SDGs pilot project funded by the Flemish Department of Foreign Affairs (DBZ) and the Directorate-General Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid, implemented by VVSG in 20 pilot municipalities (see “The key role of Flemish cities and municipalities” in the 2030 Agenda). In Argentina, the province of Córdoba is promoting the signature of voluntary co‑operation agreements to support municipalities with the implementation of the SDGs. In particular, the agreement promotes technical and research activities as well as awareness-raising campaigns. In Norway, regional planning fora, such as those existing in Viken, have been explicitly mentioned in the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation (KMD)’s Expectation Document as a tool to be used to strengthen multilevel dialogue and exchanging experiences around the SDGs.

Horizontal co‑ordination to achieve the SDGs: Enhancing policy complementarities, synergies and trade-offs management

The 17 SDGs are comprehensive in scope and cover all policy domains that are critical for sustainable growth and development. They are also strongly interconnected, meaning that progress in one area is likely to generate positive spill-overs in other domains, but can also trigger negative externalities and a race to the bottom. The SDGs, therefore, require both coherence in policy design and implementation, and multi-stakeholder engagement. Their implementation should be systemic and rely on a whole-of-society approach for citizens to fully reap expected benefits. Several pilot cities and regions are fostering such a holistic approach both in terms of the institutional frameworks to overcome policy silos and regarding multi-stakeholder dialogues (see Table 4.3).

Institutional frameworks for cities and regions to address the SDGs holistically

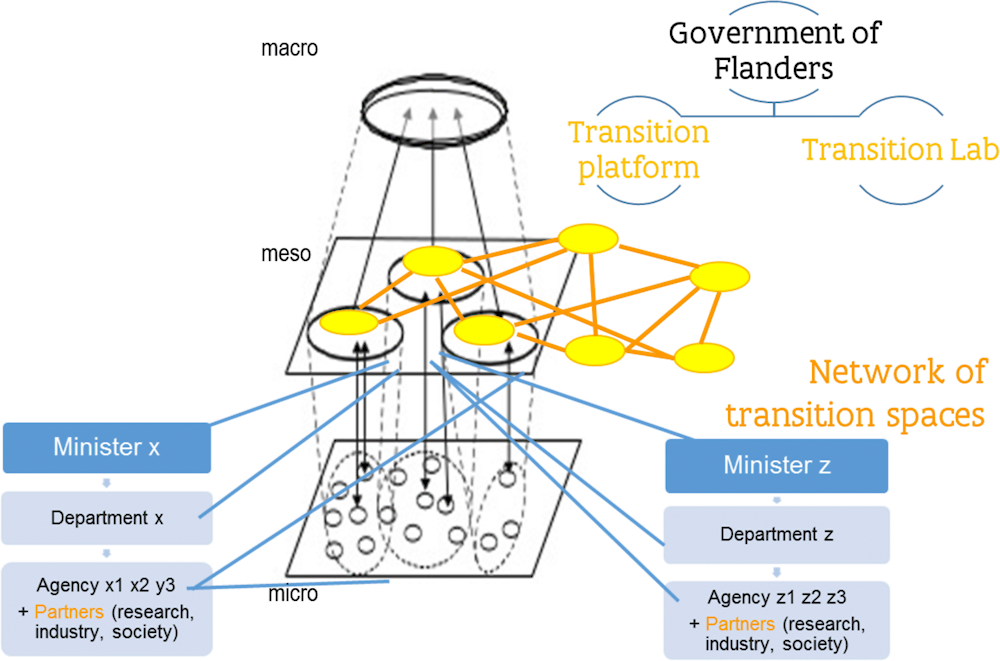

Innovative governance mechanisms to implement the SDGs holistically have started to emerge at the subnational level. One example is the new governance model put in place by the Flemish government in Belgium, based on transition management principles, namely: system innovation, taking a long-term perspective, involving stakeholders through partnerships, engaging in co-creation and learning from experiments (Figure 4.2). The model is moving away from the pyramidal, top-down and hierarchical structure of the public administration towards “transition spaces”, which are managed by teams composed of transition managers from the public administration, responsible ministers and external stakeholders, including experts, private-sector representatives and civil society. Together, the transition spaces form a network that connects the micro-level (multi-stakeholder partners) with the macro-level (the Flemish government). In March 2016, the Government of Flanders presented its new strategic outlook for the future: “Vision 2050: a long-term strategy for Flanders’. Vision 2050 sets out a vision for an inclusive, open, resilient and internationally connected region that creates prosperity and well-being for its citizens in a smart, innovative and sustainable manner. This long-term strategy provides a strategic response to the new opportunities and challenges Flanders is facing. Through the transition spaces, stakeholders from civil society, academia and the private sector collaborate with the regional government around its transition priorities. One example is Circular Flanders, where around 50 facilitators help to connect procurers with over 100 projects that provide circular economy products and services. The seven transition priorities are: i) circular economy; ii) smart living; iii) industry 4.0; iv) lifelong learning and a dynamic professional career; v) caring and living together in 2050; vi) transport and mobility; and vii) energy.

Figure 4.2. Flanders’ new governance model, Belgium

Source: Contribution by the local team of the OECD SDGs pilot of Flanders (Belgium).

In Norway, Viken uses the SDGs as the basis to build the new county organisation and public administration. In practice, this entails working on different levels to make the SDGs part of the everyday work of the county, while strengthening the county’s role as “community developer”. This implies a holistic process comprising elements such as developing relevant competencies among staff, updating administrative systems and decision-making processes that support the SDGs to ensure that Viken becomes a community developer “leading the way”. The SDGs will be included as a distinct managerial responsibility and training will be provided to managers, employees and elected politicians alike, as well as reflected in communication efforts, templates and routines.

Kitakyushu’s SDGs Promotion Headquarters in Japan guides the overall city administration in the implementation of the SDGs. The aim of the initiative is to promote effective actions to achieve the SDGs and to co‑ordinate all government institutions relevant to the 2030 Agenda under the leadership of the Mayor. These efforts are further supported by two other governance structures, which are the Kitakyushu City SDG Council (advisory board) and the Kitakyushu SDGs Club, open to anyone in the city, with 800+ members registered.

In Bonn, Germany, the SDGs provide a tool for inter-departmental and broader stakeholder dialogue around the sustainability strategy development. A key issue for the city of Bonn will be to ensure that the cross-sectoral perspective is institutionalised in the implementation of the strategy. This is why a project and steering group was set up for the whole process of developing the strategy, including 12 members from all the departments of the city administration, which ensured an integrated analysis and drafting of the strategy contents. The project group also convenes external stakeholders like businesses, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and academia, with the purpose of providing input and reviewing the content of the strategy.

In Córdoba, Argentina, the SDGs have shaped the regional development strategic lines of action for 2030. The province has established an Inter-ministerial Roundtable to raise awareness and foster the implementation of the SDGs, which is co‑ordinating all the provincial departments (ministries, secretariats and agencies) working on the prioritisation and alignment of their activities to the SDGs targets and goals. One of the key motivations to adopt the 2030 Agenda was the search for incentives to collaborate, both internally, across departments of the provincial government, and externally with other levels of government, the private sector, civil society, universities and citizens. The province is also sensitising all departments on SDGs through awareness-raising events and workshops. This work should allow to reflect and mainstream the SDGs into the sectoral policies and strategies of the province in the coming years.

In Southern Denmark, Denmark, the region is also using the SDGs for formulating its new Regional Development Strategy. The SDGs are seen as a natural step for linking the region’s current Regional Development and Growth Strategy “The Good Life” (Det Gode Liv) 2016-19 to the new strategy for 2020-23. The decision to base the next regional development strategy to the SDGs was taken in 2018. The new strategy is structured around six pillars that are considered levers to achieve the SDGs, in particular: mobility for all; green transition, climate and resources; clean water and soil; skills for the future; healthy living conditions; and an attractive region, rich in experiences.

In Kópavogur, Iceland, adopting a holistic approach to the implementation of the local strategy and its 36 prioritised SDG targets has been rather challenging. There is a long tradition of sector-based planning is the city, hence policy silos were hard to overcome in the early stages of the strategy development. Nonetheless, the municipality has set up a Steering Group with all heads of department and the project manager leading the strategy. The Steering Committee set up a Project Group that consists of two staff members from each department and the project manager of strategy. The group has succeeded in building internal awareness within the administration and is working towards the design of strategic action plans to implement the strategy.

In Moscow, Russian Federation, the SDGs are seen as a systemic framework that can help to promote an integrated approach to urban planning. Moscow is striving to find a balance between access to green areas, efficient transportation and quality housing. The city has to deal with difficult trade-offs when addressing key challenges such as the adaptation to climate change (SDG 13), since reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will imply maintaining and developing green spaces (SDG 11 or 15), reducing private transportation in favour of public transport (while at the same time catering for a growing population with the need for affordable housing) or promoting sustainable production (SDG 12), among others. The SDGs can help think, plan and act in a systemic manner and allow identify/manage synergies across different policy areas. The SDGs can offer an opportunity to broaden this perspective and look at interlinkages between socioeconomic and environmental goals. The key idea of the city is to disassociate sectors from individual SDGs.

Paraná, Brazil, has assigned the State Council of Economic and Social Development of the state of Paraná – CEDES – the role to co‑ordinate the implementation of the SDGs. CEDES is chaired by the governor and is composed of all state secretaries and three independent recognised professionals in the area of sustainable development (appointed by the Governor). The Council’s main functions are:

1. To advise the government on strategies, instruments and projects that contribute to economic growth, social development and environmental protection.

2. To design, approve and monitor the Sustainable Development Plan of the state of Paraná.

3. To strengthen communication and co‑ordination between governmental and non-governmental entities on the implementation of public policies.

The Basque Country, Spain, has developed an integrated and transversal strategy for the SDGs. The 2030 Agenda is seen as an indivisible whole and including multiple stakeholders in both its development and implementation. The Basque Internationalisation Council was set up to foster debate around the localisation of the SDGs, while the Basque parliament has created a Working Group to strengthen SDG collaboration with other organisations, regions and networks. Finally, the Udalsarea network links 183 Basque municipalities and provincial councils, as well as agencies for water and energy to promote shared responsibility for integrating sustainability into municipal action (European Union, 2019).

Table 4.3. Approaches to horizontal co‑ordination in the pilot cities and regions

|

OECD Pilot |

Horizontal co‑ordination approach |

|---|---|

|

Bonn (Germany) |

Project and steering groups set up with representatives from all city departments to provide input for the design of the local sustainability strategy, which aims to implement the prioritised SDGs. In the city council, it was decided to adopt the Sustainability Strategy and continue with the established structures. |

|

Córdoba (Argentina) |

Inter-ministerial Roundtable to raise awareness and foster the implementation of the SDGs, which is co‑ordinating all the provincial departments (ministries, secretariats and agencies) that are working on prioritisation and alignment of their activities to the SDG targets and goals. The province has also worked with actors from the private, not-for-profit, and academic sector to provide a reality check on the priorities selected by the government and to assess the interconnectedness across social, economic and environmental SDGs in the province. |

|

Flanders (Belgium) |

New governance model based on transition principles: system innovation, taking a long-term perspective, involving stakeholders through partnerships, engaging in co-creation and learning from experiments. The model is organised around “transition spaces” managed by teams composed of transition managers from the public administration, responsible ministers and external stakeholders. |

|

Kitakyushu (Japan) |

Kitakyushu SDGs Headquarters, SDG Council and SDG Club to ensure both horizontal co‑ordination and multi-stakeholder engagement in the implementation of the SDGs Future City Plan. |

|

Kópavogur (Iceland) |

Steering group set up for the development of the local strategy with all heads of department, while the strategy’s Project Group co‑ordinates the contents and strategic action plans by all departments to implement the strategy. |

|

Moscow (Russian Federation) |

Local departments co‑ordinate through the implementation of specific programmes, such as for the urban regeneration programme, the Moscow Electronic School or the Magistral Route Network. |

|

Paraná (Brazil) |

The Social and Economic Development Council in Paraná is responsible for co-ordinating the implementation of the SDGs in the state and for the development of a plan to implement SDGs. All state secretaries and other stakeholders are part of the council and participate in the discussions and in the decision-making process. |

|

Southern Denmark (Denmark) |

An interdisciplinary working group has been set up to identify how the SDGs can be integrated into regional development. |

|

Viken (Norway) |

New county organisation built on the SDGs, where the goals become a new management responsibility and part of everyone’s daily tasks and routines. |

Assessing SDGs synergies and trade-offs at the local and regional levels

Analysing the detailed relationship between the goals and targets is essential in order to avoid progress on one goal preventing or even worsening performance on another. Some typical examples of interconnected goals include synergies between promoting economic growth (SDG 8), ending poverty (SDG 1) and promoting equality (SDG 10). Trade-offs can include higher levels of CO2 emissions resulting from economic activity, hence working against combating climate change (SDG 13) or unsustainable use of natural resources threatening life on land (SDG 15) and in the sea (SDG 14), unless measures are taken to counter these. Access to clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) is another example of a highly interconnected goal. While it is critical to lift people out of poverty (SDG 1) and foster gender equality (SDG 5), the largest water consumers are farmers, which holds implications for SDG 2 (no hunger). While energy subsidies to farmers contribute to energy affordability, as called for in SDG 7, they undermine water use efficiency (SDG 6) because they incentivise over-abstraction from rivers and aquifers. Co‑ordination across water, energy and agriculture policies is essential to manage trade-offs.

In many policy domains, the local scale can often be more appropriate to unpack the complexity of trade-off management through tailoring concrete solutions to specific places. For instance, cities and regions can help to accelerate the transition to the circular economy, helping to keep the value of resources at its highest level, while decreasing pollution and increasing the share of recyclable materials. This supports the transition to more sustainable and responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), while contributing to economic growth and job creation (SDG 8), and reducing negative environmental impacts (e.g. SDG 13, 14 and 15).

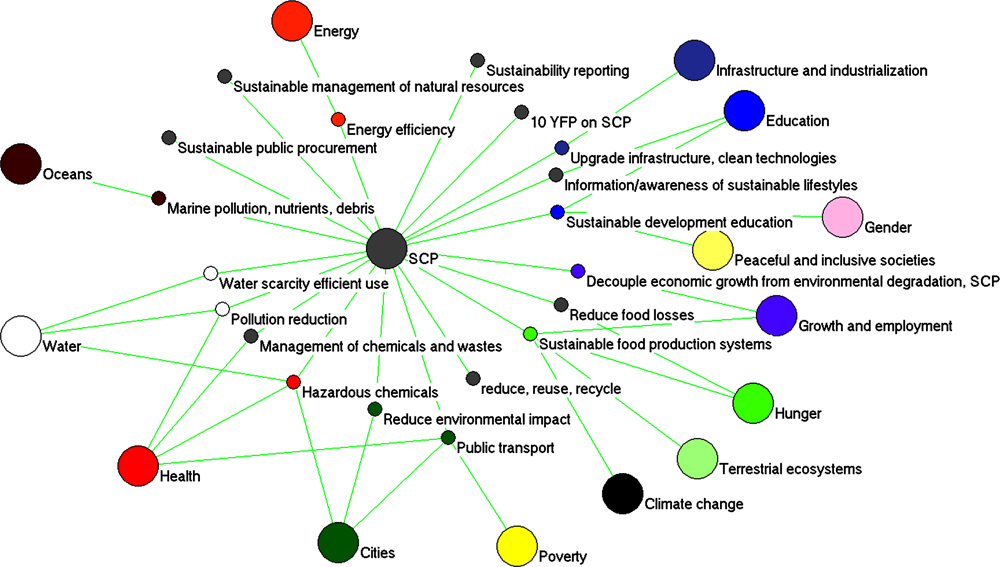

Several institutions have applied network analyses to understand the interlinkages between SDGs goals and targets and existing policies, helping to break “silo” thinking. By showing how the goals are interconnected, some with more frequent connections – “stronger ties” – than others, network analyses can help to promote policy integration in areas that may be traditionally sectoral. The UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) carried out network analyses for SDG 3, SDG 10 and SDG 12 against the other SDGs by using the wording of the targets to detect interlinkages. For example, the interlinkages between the targets of SDG 12 and other SDGs were counted with reference to how many of the other SDGs targets explicitly refer to sustainable consumption and production (Le Blanc, 2015). From this perspective, the “core” targets represent those directly part of SDG 12, while the “extended targets” are those covered in other SDGs but nevertheless relevant to the achievement of SDG 12. In this way, network analyses can enable cross-sector dialogues and thus help to address the “silo” approach, as experienced in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Figure 4.3 illustrates the network analysis of SDG 12 (Sustainable Consumption and Production) and the rest of the SDGs.

Figure 4.3. Network analysis of SDG 12 vis-à-vis other SDGs and targets

Note: SDG 12 is denoted by SCP: Sustainable Consumption and Production.

Source: Le Blanc, D. (2015), “Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets”, No. 141.

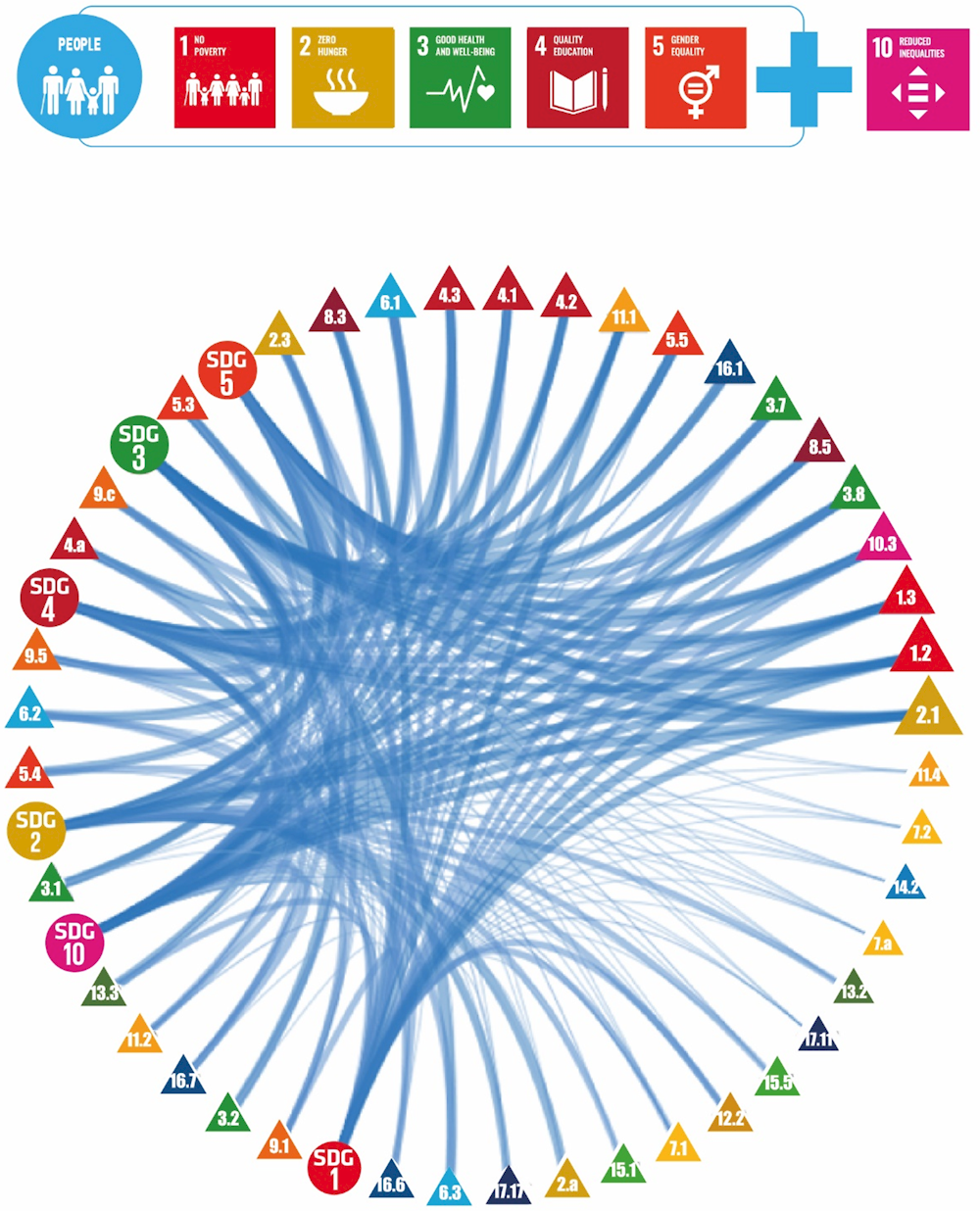

Some cities and regions have pioneered different methods and approaches to analyse the interactions between the SDGs, both in terms of synergies and trade-offs. Matrix approaches combining scientific evidence, expert opinions and participative policymaking processes provide useful tools to understand and address SDGs interactions. For example, the province of Córdoba, Argentina, is developing a matrix to identify “key drivers” of social inclusion in the province by analysing the synergies between SDGs 1 to 5 and SDG 10 on the one hand, and all SDGs related to environmental and economic outcomes on the other hand (Figure 4.4). The Matrix is inspired by the International Council for Science’s Guide to SDG Interactions: From Science to Implementation (ICSU, 2017), which entails scoring SDGs and targets according to the positive, negative or neutral relationship between each other. In the framework, a seven-point scale is developed based on scientific evidence and expert judgement of causal and functional relations between the SDGs and their targets. When goals and targets can be expected to contribute to each other’s achievement, they are scored either +1 (enabling), +2 (reinforcing) or +3 (indivisible). Goals and targets that involve trade-offs are scored -1 (constraining), ‑2 (counteracting) or -3 (cancelling).Neutral relations are scored 0. While acknowledging that many of the scores will be partly subjective, the authors highlight that the approach can be useful to identify essential knowledge gaps regarding interactions between the goals.

Figure 4.4. Matrix to identify “key drivers” of social inclusion in the province of Córdoba, Argentina

Source: Secretaría General de la Gobernación (2019), Córdoba hacia el 2030 - Tercer taller, Los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible en el contexto local.

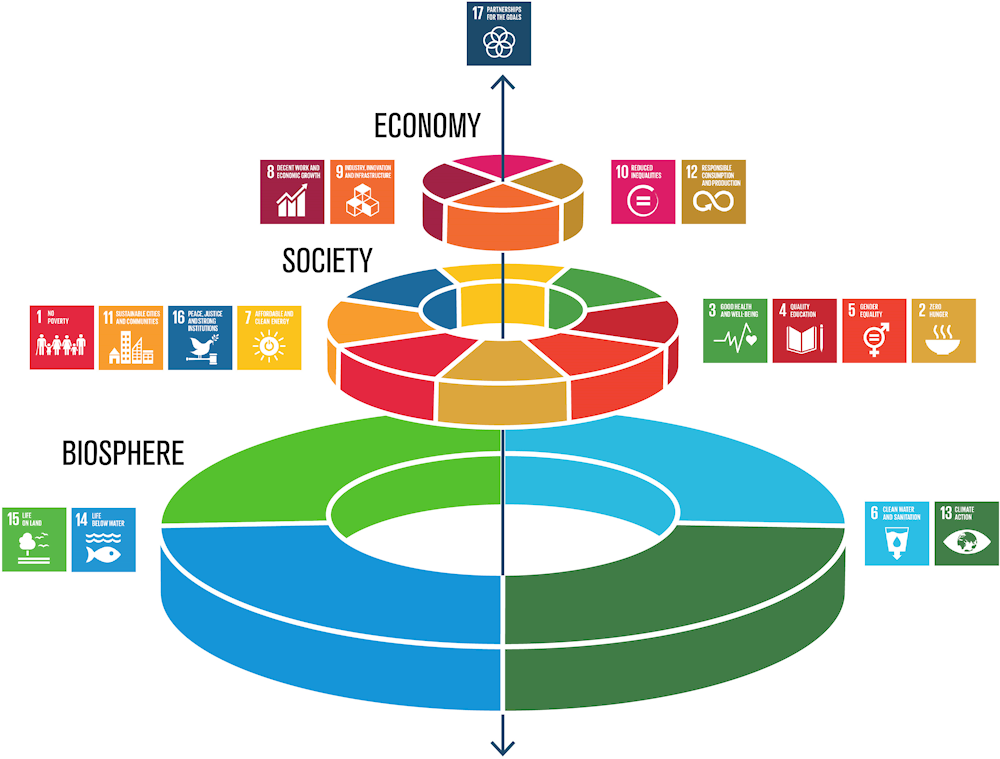

The “planetary boundaries” approach is another lens through which synergies and trade-offs across SDGs can be assessed. The “planetary boundaries” discourse implies focusing on long-term Earth-system stability while accounting for human development needs, acknowledging that some of the goals can be incompatible, unless set within planetary boundaries. For example, addressing climate change while promoting increased gross domestic product (GDP) growth can be incompatible unless significant decarbonisation of the economy takes place concurrently. Figure 4.5 shows a diagram developed by the Stockholm Resilience Centre called the “wedding cake”, whereby the environmental SDGs are considered foundational to all other goals. This model has inspired the county of Viken, Norway, to reflect on the relation between socioeconomic development and planetary boundaries. This has proven to be a challenging endeavour that needs further exploration. The complex relation between different SDGs will be shown by qualitative descriptions rather than quantitatively through the indicator set developed by the county.

Figure 4.5. The Stockholm Resilience Centre’s SDGs “wedding cake”

Photo credit: Azote Images for Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University.

Source: Stockholm Resilience Centre (2016), Contributions to Agenda 2030 – How Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC) contributed to the 2016 Swedish Agenda 2030 HLPF report, https://www.stockholmresilience.org/SDG2016.

Data-driven policymaking can also help to build integrated solutions for the goals. In Kópavogur, Iceland, the local administration is pioneering data-driven solutions for linking the SDGs goals and targets across municipal services and projects through an information and management system and software called MÆLKÓ (Measuring Kópavogur). The MÆLKÓ data warehouse incorporates around 50 different data systems, including service data from schools and kindergartens, building inspections data and human resources indicators, among others. The system will help to calculate performance indicators and indexes and support automatic updates to keep track of objectives and goals. The ultimate aim is to support the efficiency of the local administration in its work towards its 36 prioritised SDGs targets.

Geographical mismatches can be witnessed in the case of Norway, where counties and municipalities operate in a complex territorial governance system with many overlapping structures and collaboration agreements. In addition to its 51 municipalities, Viken alone is involved in 51 different regional state authorities and at least three significant regional collaboration networks. To address this complexity, the OECD promotes a functional approach to urban policies, using the definition of cities as functional urban areas (FUAs). For the county of Viken, this approach will be particularly relevant in order to understand the interplay with the Metropolitan FUA of Oslo, which is at the geographic core of the county and includes many municipalities that administratively belong to Viken. Yet, the urban core of Oslo has its own status as both municipality and county. Close collaboration between Oslo and Viken and its municipalities will thus be key to the sustainable development of Viken while promoting balanced urban development in the region.