This chapter considers the relationship between carbon pricing, carbon efficiency and economic output across economies. Countries with higher carbon pricing scores tend to be more carbon efficient, as measured by carbon emissions per unit of economic output. Likewise, countries that increase their carbon pricing scores also become more carbon efficient. In addition, countries more advanced with carbon pricing also tend to produce more economic output per capita, and countries that progress more with carbon pricing show a stronger increase in economic output per capita.

Effective Carbon Rates 2021

5. The bigger carbon pricing picture

Abstract

This chapter considers the relationship between the CPS, and the emission intensity of GDP (a climate perspective) and GDP per capita (an economic output perspective).

Climate effects

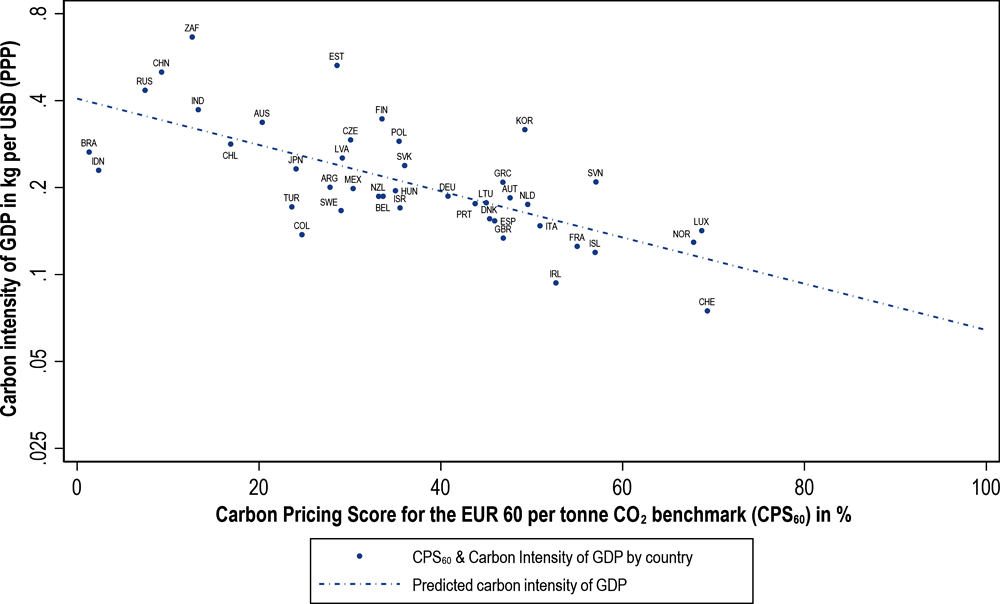

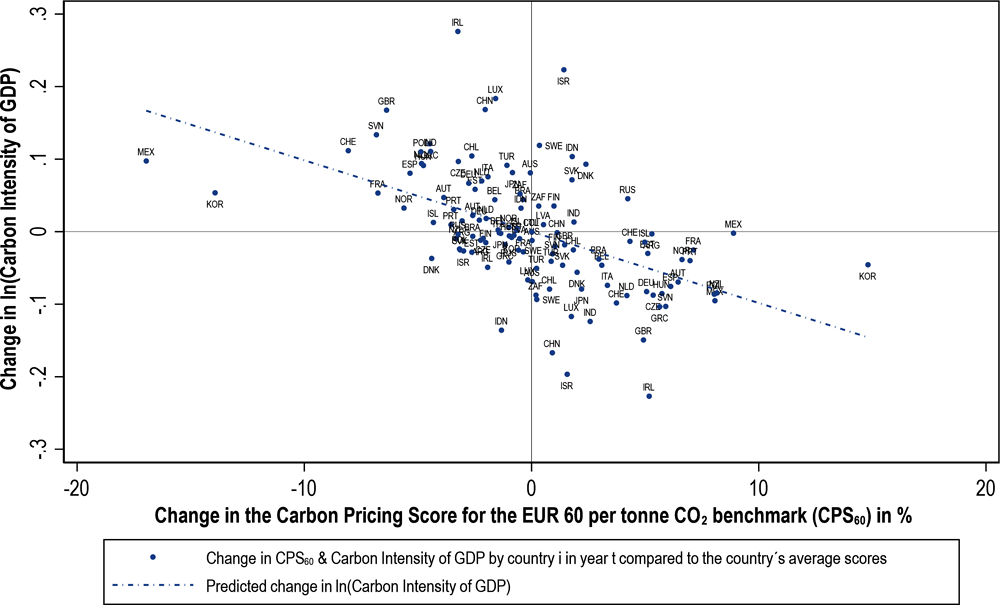

Figure 5.1 shows that countries that have a higher CPS are, on average, also more carbon efficient, i.e. they emit fewer emissions per unit of GDP. Figure 5.2 shows the same relationship but considering changes in the CPS and relating them to changes in the carbon emission intensity of GDP. Countries that increase their CPS are shown on the right side of Figure 5.2, i.e. their change in the score is positive. On average, these countries have also experienced a decrease in their carbon intensity of GDP, which shows from a negative change in the carbon intensity of GDP, meaning that they are located in the bottom half of the graph.

Figure 5.1 does not necessarily imply a direct causal effect in either direction. Low emissions per unit of GDP can be the result of a high carbon pricing score steering the economy towards zero- and low-emission energy sources. Alternatively, countries with fewer emissions per unit of GDP may find it easier to price emissions. Figure 5.2 controls for unobserved country-specific effects that are constant over time, ruling out that a low-carbon intensity of GDP is entirely explained by factors other a high CPS. Nevertheless, it could be the case that countries that decrease their carbon intensity of GDP simultaneously increase their CPS, e.g. if carbon pricing is enacted together with a suite of other climate polices. In such circumstances, it is difficult to estimate the exact contribution of a higher CPS on carbon efficiency.

Notwithstanding the caveats in interpreting Figure 5.1 and Figure 5.2 there is strong empirical evidence that clearly shows that higher carbon prices lower emissions, see for example the literature reviews by Arlinghaus (2015[7]) and Martin et al. (2016[8]). Carefully identifying the effects of higher effective carbon rates, Sen and Vollebergh (2018[9]) find that a EUR 10 per tonne of CO2 increase in the effective carbon rates is expected to lead to a 7.3% reduction in carbon emissions on average.

Figure 5.1. Countries with a higher carbon pricing score are more carbon efficient

Reading Note: The graph shows that countries that have a higher carbon pricing score towards the benchmark of EUR 60 per tonne CO2 (a low-end benchmark for carbon costs in 2030) have a lower carbon intensity of GDP.

Source: GDP data from the World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2020[28])

The association of a higher CPS with a lower emission intensity of GDP is consistent with the notion that by pricing all emissions at a minimum of EUR 60 per tonne of CO2, countries can make significant progress towards the net-zero emissions goal, but that carbon-neutrality by mid-century very likely requires additional efforts. To illustrate, a simple log-linear regression of the CPS60 on the carbon intensity of GDP (Figure 5.1) reveals that a one percentage point increase in the CPS60 is associated with a 1.8 percent decrease in the carbon intensity of GDP. By this log-linear relationship, countries that reach a CPS60 of 100, would be expected to lower their carbon emission intensity to around 0.06 kg per unit of GDP over time. Scenarios by Peters et al. (2017, p. 120[29]) for limiting global warming to 2°C require that the world economy reach net-zero emissions in the 2060s. The corresponding emission pathways imply a carbon intensity of GDP that is lower than 0.07 kg per unit of GDP by 2040. However, scenarios consistent with achieving the goal of the Paris agreement to limit global warming to 1.5°C require net-zero emissions already by mid-century (Rogelj et al., 2018[14]) and thus steeper emission pathways.

Figure 5.2. Countries that increase their carbon pricing score also become more carbon efficient

Reading Note: If a country increases its carbon pricing score (i.e. it moves towards the right), this goes hand in hand with a decrease of its carbon intensity of GDP (i.e. it moves downwards). The dotted line visualises the corresponding panel fixed effects regression of the carbon pricing score on the emission intensity of GDP.

Source: GDP data from the World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2020[28])

Economic output effects

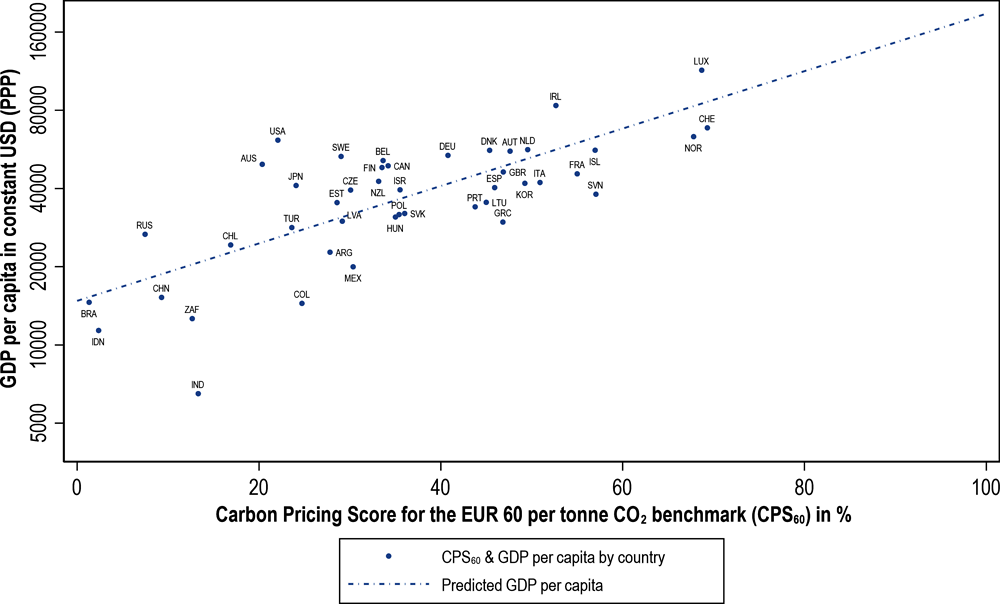

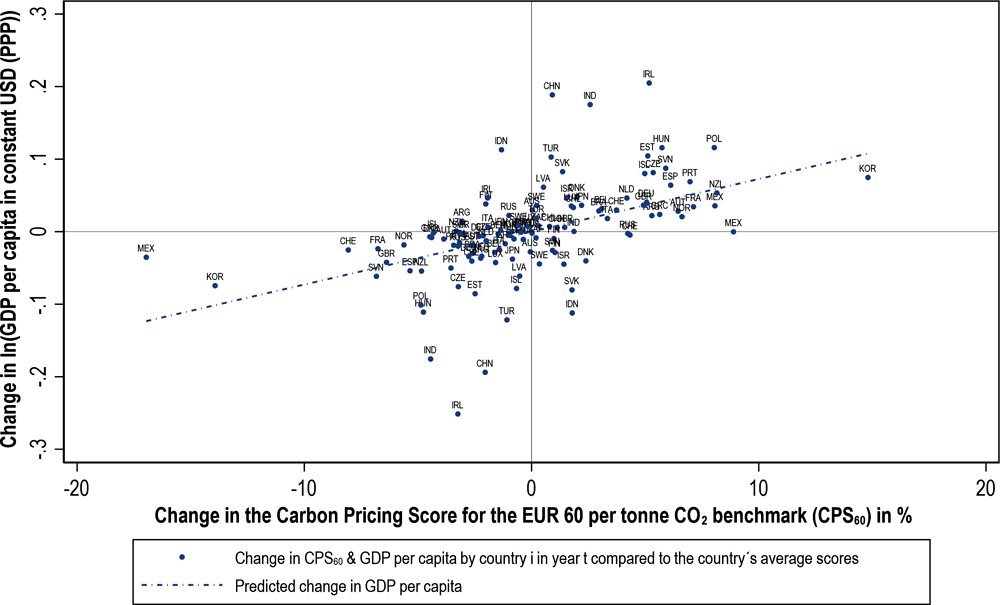

Figure 5.3 shows that countries with a higher CPS are also generally richer, at least in terms of GDP per capita. Moreover, countries that increase their CPS (shown on the right side of Figure 5.4) increase their GDP per capita at the same time (shown in the upper half of Figure 5.4). These findings do not necessarily imply a direct causal effect in either direction. Countries with a high GDP per capita may find it easier to price carbon emissions, and the same may hold for countries becoming richer. However, the findings are also consistent with the notion that countries that employ carbon pricing as a key climate policy reduce emissions more economically, and thus benefit from superior economic performance.1 With the Paris Agreement, countries decided to decarbonise their economies by about mid-century and given this commitment, those countries that decarbonise their economies more economically are likely to perform better across a broad range of dimensions including the level of GDP per capita.

Figure 5.3. Countries closer to the carbon pricing benchmark have a higher GDP per capita

Reading Note: The graph shows that countries that have a higher carbon pricing score towards the benchmark of EUR 60 per tonne CO2 (a low-end benchmark for carbon costs in 2030) have a higher GDP per capita.

Source: GDP data from the World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2020[28]).

Figure 5.4. Countries that progress more with carbon pricing show a stronger increase in GDP per capita

Note: If a country increases its progress towards pricing all its emissions at least at EUR 60 per tonne CO2 (i.e. it moves towards the right), GDP per capita increases (i.e. it moves upwards). The dotted line visualises the corresponding panel fixed effects regression of the carbon pricing score on GDP per capita.

Source: GDP per capita from the World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2020[28]).

References

[1] Arlinghaus, J. (2015), “Impacts of Carbon Prices on Indicators of Competitiveness: A Review of Empirical Findings”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 87, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5js37p21grzq-en.

[7] European Systemic Risk Board (2016), “Too late, too sudden: Transition to a low-carbon economy and systemic risk”, Reports of the Advisory Scientific Committee 6, https://www.esrb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/asc/Reports_ASC_6_1602.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2018).

[2] Martin, R., M. Muûls and U. Wagner (2016), “The Impact of the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme on Regulated Firms: What Is the Evidence after Ten Years?”, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, Vol. 10/1, pp. 129-148, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/reep/rev016.

[5] Peters, G. et al. (2017), “Key indicators to track current progress and future ambition of the Paris Agreement”, Nature Climate Change, Vol. 7/2, pp. 118-122, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3202.

[6] Rogelj, J. et al. (2018), “Mitigation Pathways Compatible with 1.5°C in the Context of Sustainable Development”, in Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. (eds.), Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C., IPCC.

[3] Sen, S. and H. Vollebergh (2018), “The effectiveness of taxing the carbon content of energy consumption”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Vol. 92, pp. 74-99, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.JEEM.2018.08.017.

[8] Siegert, C. (ed.) (2020), Mainstreaming the transition to a net-zero economy, G30: Group of Thirty, Washington, D.C.

[4] World Bank (2020), World Development Indicators, World Bank, Washington, D.C:.

Note

← 1. Carbon prices are key to cost-effective (or economic) emission reduction. They ensure that low-cost abatement options are carried out, before options that are more expensive are considered. Countries that heavily rely in policies other than carbon pricing likely miss out on some of the low-hanging abatement options and thus increase their overall abatement costs. Countries that delay abatement until it is unavoidable also risk increasing overall abatement costs as carbon-intensive capital can then become suddenly obsolete (European Systemic Risk Board (2016[33]); Siegert et al. (2020[35])).