This chapter explores the contribution of the business sector to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through three different angles. First, it reviews the academic literature on the role of firms in the provision of social goods, and their incentives to engage in such investments. Second, it gathers and describes examples of firms’ actions related to the SDGs. Finally, it presents evidence on firms’ prioritisation, actions and planning related to SDGs using the United Nations Global Compact survey data.

Industrial Policy for the Sustainable Development Goals

2. The role of the business sector with respect to the SDGs

Abstract

Key messages

Firms are well placed to contribute to social goods by producing new products, reducing negative externalities (e.g. effect on biodiversity) and inducing positive cross-border impacts (e.g. eliminating child labour in their operations abroad, in-house or outsourced). However, the private sector’s contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) remain insufficient.

The uncertainty of financial returns on firms’ sustainability investments is a substantial barrier to action. The tensions between financial and sustainability objectives hamper firms’ sustainability advances, leaving room for policy interventions to foster contributions to the SDGs.

Nonetheless, numerous firms already consider it economically viable to develop sustainable products and services linked to their core business. As the SDGs draw increased attention, this may expand both business opportunities for companies and value added for society. Selected examples and survey data show that firms of all size categories can find a business case for aligning their core business with the SDGs: the vast majority of firms are willing to take strategic action towards the SDGs by linking activities to their core business.

For these firms, sustainability shifts can be considered as intangible investments, complementary to other types of tangible and intangible capital. As with any other type of capital, this “sustainability” capital can bear fruit in both the short and long run. However, shifting to sustainability requires a comprehensive approach and structural changes in the firm’s culture. It entails the strong commitment of corporate leaders, a demonstration of the business case to stakeholders, the adaptation of the business model and an efficient communication with customers on sustainable strategies and practices.

Even among frontrunners, SDG actions differ widely across countries, sectors and firm size. The latter is a major determinant of actions, target setting and development of SDG-related products, with small firms facing more obstacles. SDG 3-Good Health and Well Being, SDG 5-Gender Equality, SDG 8-Decent Work and Economic Growth, SDG 9 Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, SDG 12-Responsible Consumption and Production and SDG 13-Climate Action are the most prioritised by firms.

Context

The degree of firm involvement in tackling the SDGs varies across firms and across countries for several reasons. First, there is no clear consensus among the business community about whether SDG action is economically viable, and beneficial for firms, or not. Second, some firms still struggle to align the SDG framework – and other sustainability-related business concepts (Box 1.1) – with their business operations. Third, the measurement of firms’ contributions to the SDGs rests on the measuring of their impact through well-designed indicators. However, Shinwell and Shamir (2018[1]) review the available frameworks (Box 2.1) and stress the methodological challenges of these frameworks, and the use of different indicators jeopardising comparability across firms. They also conclude that the SDGs have resonated strongly within the business community, particularly through these initiatives.

To lay the groundwork for the analysis developed in the rest of this report, this chapter explores the contribution of the business sector to the SDGs through three different angles. First, it reviews the academic literature on the role of firms in the provision of social goods, and their incentives to engage in such investments. Second, it gathers and describes examples of firms’ actions. Finally, it presents evidence on firms’ prioritisation, actions and plans related to SDGs using the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) survey data. These data allow for the comparison of the SDG awareness, orientation and, to some extent, actions, of firms across countries. They can also point to categories of firms and/or SDGs that deserve particular attention from policy makers.

Box 2.1. A few examples of sustainability reporting frameworks

The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is a non-profit organisation (NPO) that helps governments and businesses worldwide understand their impact on critical issues related to climate change, human rights and social well-being. GRI standards are among the most widely adopted global standards for sustainability reporting. A mapping between GRI standards and the SDGs is available.1

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) is an independent standards board that is accountable for the process, deliverables, and ratification of the SASB standards. The main focus of SASB is to establish industry-specific disclosure across environment, social and governance (ESG) topics that can facilitate the communication between companies and investors.

The Sustainable Development Goal Compass is a framework that provides guidance for companies on how they can align their action towards the SDGs.

Social Accountability International is a global non-governmental organisation (NGO) that works to advance human rights at work and develop multi-industry standards. These standards include Social Accountability 8000 (SA8000), TenSquared and Social Fingerprints. SA8000, for instance, is an auditable certification standard to develop, maintain and apply socially acceptable practices in the workplace. The SA8000 standard addresses workers' rights, workplace conditions and management systems and is as such related to the SDG 8‑Decent Work and Economic Growth.

Source: See Shinwell and Shamir (2018[1]), “Measuring the impact of businesses on people’s well-being and sustainability: Taking stock of existing frameworks and initiatives”, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/51837366-en for a more exhaustive list of initiatives, including ESG ratings.

Firms can complement governments and households in the pursuit of SDGs

The literature on the social responsibility of businesses started following the provocative column from Friedman (1970[2]), in which he stated that firms should only maximise their value for shareholders.

The objective of Friedman (1970[2]) was probably not to say that firms should completely disregard their social responsibility. Indeed, shareholders, and more generally households may also value1 the contribution of firms to social goods (Baron, 2007[3]). Rather, Friedman’s column questions the role of private firms in the contribution to these social goods, and the channels through which they can contribute to them.

Indeed, the provision of social goods can be financed by several agents:

households, contributing through charity giving or personal involvement in NGOs

the government (and indirectly the households), through taxes

firms, through their operations or the use of their profit.

If the three channels were perfect substitutes (as implicit in Friedman’s thinking), it would probably be inefficient to fund social goods through the firms. However, there are several reasons to believe that the three channels are imperfect substitutes:

The efficiency of the channels can vary depending on the social good considered, and firms may be more efficient in some instances:

Firms can be well placed to introduce new commercially viable products and processes that contribute to the achievement of SDGs.

For instance, for global challenges, multinationals may be better equipped than governments to address the issues, for example, child labour abroad (Bénabou and Tirole, 2010[4]).

Remedying some of the firms’ negative externalities (e.g. impact on biodiversity) may be more costly than avoiding them (Hart and Zingales, 2017[5]).

The cost of funding social goods through the different channels may be biased by the design of the corporate tax system.

Firms may want to contribute to the social goods on a voluntary basis (Coase, 1960[6]; Costello and Kotchen, 2020[7]), in particular when the externalities can be easily attributable to the firm (e.g. local pollution with a rare chemicals).

The provision of social goods by the firm can be achieved in several ways, depending on the link with the operations of the firm. The contribution of the firm can be tightly related to the core business of the firm (e.g. producing new drugs), pervasive in the firm’s operations although not directly related to its products (e.g. reducing greenhouse gas [GHG] emissions in the production process), or not directly related to the daily operations (e.g. using the firms human or financial resources to support NGOs).

Demand for the social and environmental accountability of firms has been increasing over the last 30 years. Bénabou and Tirole (2010[4]) cite four reasons for this trend: 1) the higher demand for social and environmental responsibility as standards of living are improving in developed countries; 2) the increased availability of information on companies’ operations; 3) globalisation and the operations of multinationals in developing countries; and 4) the increased awareness on climate change.

Firms can benefit from sustainability efforts through several channels

Whereas the previous section made it clear that firms can have a role to play in funding social goods, it does not necessarily mean that they will indeed engage in this activity, or that they will not under-invest in sustainability.

Therefore, two cases can be distinguished:

Sustainability efforts are in the financial interest of shareholders because it increases the value of the firm (strategic or win-win view (Baron, 2007[3]; Bénabou and Tirole, 2010[4]), also sometimes referred to as the triple bottom line approach).

Sustainability efforts are not in the financial interest of shareholders but is valuable for the broader community of stakeholders (altruistic view).

This section first reviews the literature on the relationship between sustainability and financial performances. This review does not offer a clear-cut conclusion and this relationship heavily depends on the type of SDG action. The remainder of this section explores the channels through which the financial and sustainability objectives are either consistent or conflicting.

Do sustainability efforts increase the financial value of a firm?

The strategic view of sustainability efforts can only be supported if the contribution to social goods effectively and positively affects the corporate financial performance (CFP) of a firm.

Despite extensive research conducted across countries to explore the corporate social performance (CSP)-CFP relationship, it remains unclear. While positive CSP-CFP relationships are more commonly found in some meta-analyses (Margolis, Elfenbein and Walsh, 2007[8]; Orlitzky, Schmidt and Rynes, 2003[9]; Hermundsdottir and Aspelund, 2021[10]), other recent contributions do not find any correlation between corporate responsibility and CFP (Surroca, Tribo and Waddock, 2010[11]; Endo, 2013[12]). Another strand of research, mainly focused on listed firms, investigates the impact of incorporating corporate sustainability factors into investors’ decisions, and usually corroborates a positive correlation between the ESG score of the portfolio and its financial performance (Hua Fan and Michalski, 2020[13]). These diverging results may be due to four different factors.

First, heterogeneous sustainability initiatives can be observed among firms. Different issues are addressed: environmental vs social; charity vs non-financial contributions; social issues linked to a firm’s value chain vs social issues affecting the business in-house vs generic social issues (Porter and Kramer, 2006[14]). Firms also differ by their degree of involvement in sustainability, and some studies have found a U-shaped or an inverted-U shaped relationship between sustainability and financial performances (Boakye et al., 2021[15]; Grassmann, 2021[16]).

Second, the measurement methodology, and thus the evaluation of the firm’s sustainability performance, are not standardised (Galant and Cadez (2017[17]) for corporate social responsibility [CSR]). While some evaluators measure only one aspect of sustainability initiatives (e.g. environmental aspect, amount of charity), others evaluate different or multiple aspects. The comparability of sustainability performance between firms remains challenging (Box 2.1).

Third, the relationship may instead be between CFP and the change in sustainability orientation. In theory, with perfect financial markets, the sustainability orientation of a firm should be priced, since inception and the CFP should only reflect subsequent changes in the firm’s sustainability orientation. In that case, the relationship between sustainability efforts and CFP, as measured by the evolution of stock prices, would be blurred (Alexander and Buchholz, 1978[18]).

Finally, other studies also show that the relationship between CSP and CFP may be due to an omitted variable bias, namely the stock of intangibles (Surroca, Tribo and Waddock, 2010[11]) or financial constraints (Hong, Kubik and Scheinkman, 2012[19]).

Focusing on one dimension of sustainability can to a certain extent lessen the problem of the heterogeneity of business actions and the issue of their measurement. For instance, the link between environmental regulation and firm performance is usually referred to as the Porter hypothesis. The literature shows that, even if the environmental regulation fosters innovation and productivity, the net impact on competitiveness remains negative or close to zero in a majority of the studies (Ambec et al., 2013[20]; Dechezleprêtre and Sato, 2017[21]; Dechezleprêtre et al., 2019[22]).

In summary, the positive link between CFP and sustainability remains unclear at the aggregate level and is likely to depend on the characteristics of the targeted social good and the firm, as well as on the economic context.

The two following subsections focus first on the channels through which sustainability can foster the financial value of a firm and then on the tensions arising between financial and other objectives.

Through which channels can sustainability efforts positively affect the financial value of a firm?

Academic and business literatures cite a number of reasons why sustainable practices may have a positive impact on a company:2

By decreasing “short-termism” (Bénabou and Tirole, 2010[4]). Introducing sustainability concerns may increase the long-term performance of companies. It can for instance help alleviate ineffective managerial incentives or a limited temporal horizon of managers. Bénabou and Tirole (2010[4]) cite the example of a firm reneging on an implicit contract with a supplier, thereby increasing its short-term profit but damaging goodwill and potentially the value that can be extracted from that relationship in the long run. In the same vein, increasing the managerial horizon can foster the internal incentives to innovation.

By strengthening the commitment of stakeholders – in particular employees –, making their personal motivations more aligned with those of the company (Graafland and Noorderhaven, 2019[23]; Jones, 1995[24]; Hiller and Raffin, 2020[25]). More fundamentally, some authors even argue that sustainability is a major component of corporate culture. Corporate culture corresponds to the “glue that binds employees together” and contributes to explaining why firms emerge as an efficient way to organise production (Gorton and Zentefis, 2020[26]).

By increasing the resilience of firms to various type of exogenous shocks:

Sustainability efforts decrease risk, for instance by avoiding costly lawsuits or scandals (Carroll and Shabana, 2010[27]; Hallikas, Lintukangas and Kähkönen, 2020[28]).

Firms with better environmental and social performances have a lower financial distress risk (Boubaker et al., 2020[29]).

This channel is also put forward during the COVID-19 crisis. Publicly listed firms with a higher pre-crisis investment in sustainability show a significant smaller decline in stock price, which is interpreted as the consequence of stronger ties with stakeholders more willing to make adjustments to support the firm’s continuity (Ding et al., 2020[30]; Chintrakarn, Jiraporn and Treepongkaruna, 2021[31]).

Through an improved corporate reputation and image:

Improving the perception of the firm can increase the demand for its products (Schuler and Cording, 2006[32]; Chuah et al., 2020[33]). For instance, Ricci et al. (2020[34]) show that the impact of digital innovations is magnified for more sustainable firms, perhaps because of a higher level of trust from their customers.

An improved image can increase the firms’ attractiveness on the labour market (Albinger and Freeman, 2000[35]; Jones, Willness and Madey, 2014[36]), thereby improving the talent of its new employees.

Sustainability efforts can also be used as a signalling tool towards stakeholders, such as suppliers or investors.

As a result, sustainability practices are usually thought of as having a positive impact on innovation (Graafland and Noorderhaven, 2019[23]), and more generally on productivity. Examples of this in recent literature include:

Graafland and Noorderhaven (2019[23]) who, using a large survey on a sample of European small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), show that the innovation motive for CSR is one of the most frequently cited by managers, especially for environmental CSR, with employee satisfaction also often cited as a motivation.

Hoogendoorn, van der Zwan and Thurik (2020[37]) show that start-ups that put more emphasis on environmental values are more likely to innovate; perhaps because their leaders internalise the positive spillovers of their inventions on the environment.

Liu, Sun and Zeng (2020[38]) show that, among Chinese firms, a higher employee-related CSR score spurs innovation.

Sustainability actions can thus be understood as an investment in intangible capital, complementary to other types of tangible and intangible capital. As with any other type of capital, this “sustainability” capital can bear fruits both in the short and long run, and needs to be maintained in order to compensate for its depreciation.

Tensions between financial and sustainability objectives may also arise

The literature review clearly shows that sustainability and financial objectives are not perfectly aligned (e.g. (Wannags and Gold, 2020[39]) for examples of tensions and trade-offs, mainly arising from the cost of the sustainability actions).

Porter and Kramer (2006[14]) distinguish between strategic CSR – which can increase the competitive advantage of the firm – and responsive CSR. Even in the case that responsive CSR can have a marginal positive impact on the financial performance of the firm, through a decrease in the risk of scandal or lawsuits, the authors argue that the effect is likely to be small in the long run, and outweighed by the costs of these actions. Responsive CSR includes the provision of generic public goods and the mitigation of harm caused by value-chain activities. Strategic CSR includes actions on social dimensions providing a competitive advantage to the firm directly (e.g. Toyota’s comparative advantage on hybrid vehicles, which contributes to the mitigation of GHG emissions), or through its supply chain (e.g. Nestlé’s milk district in India, which provides infrastructure and knowledge to local farmers).

The uncertain financial return of sustainability investments, and the tensions between financial and sustainability objectives, tend to support the hypothesis of an under-provision of social goods by firms, and provides a case for policy interventions.

How firms tackle SDGs in practice

The inconclusiveness of the literature on the link between sustainability and financial performance calls for a more granular approach. This section provides some examples of firms’ actions to explore the business case for being sustainable, and the underpinnings of firms’ actions. It relies on more than 50 selected cases from the UNGC-KPMG industry matrices, the Global SDG Award, the UNGC and company websites.

Typology of firms’ SDG actions

In line with the literature review in the previous section, the cases are classified according to two criteria into a four-by-four matrix (Table 2.1). The two criteria are defined by:

The objective of the action, building on Porter and Kramer (2006[14]), classified into four categories. The first two categories are considered as strategic uses of SDGs (or creating shared value) (see Box 1.1), because they provide a competitive advantage to the firm (for instance through increased sales or margins, reduced costs, or higher resilience).

1. Strategic in-house contribution to SDGs. Leveraging the ever-growing importance of SDGs, the objective is to increase revenues or profitability, notably by strengthening the involvement of the firms’ stakeholders, including employees, customers, business partners, shareholders and local communities. Some firms set this contribution to SDGs central to their long-term business strategy.

2. Transformation of global value chains (GVCs) and reinforcement of business strategy. Some firms that are involved in GVCs, either upstream or downstream, aim to contribute to SDGs by proactively and positively affecting their suppliers’ and intermediate customers’ well-being. This objective is close to the previous category (leverage on sustainability to increase or maintain the long-term business viability and profitability), but focuses on the supply chain rather than on in-house operations.

3. Mitigation of harm from GVCs. Some firms undertake responsive actions towards their suppliers or employees in their GVC to minimise reputational risk and negative externalities arising from their business operations, sometimes regardless of whether there is a direct causality or not.

4. Generic social impacts/good citizenship. Some firms simply try to do good for society (e.g. local communities), either by limiting the harm from their in-house operations, or in a way that is completely apart from their business. To some extent, this is close to the common understanding of CSR, and these actions do not have the direct objective of increasing revenues or profits.

The channel of action is also classified into four categories, depending on the link with the other operations of the firm. The categories are as follows, based on the literature review of sections “Firms can complement governments and households in the pursuit of SDGs” and “Firms can benefit from sustainability efforts through several channels”.

1. Core business. Some firms develop new products or services close to their core business in order to contribute to the SDGs. Integrating the SDG contribution into their main business pillar, these firms proactively upgrade their business model, business strategy and even research and development (R&D) directions. As SDGs draw more and more attention of stakeholders, this course of action may expand firms’ business opportunities, increasing their value added to the society and potentially their profits.

2. Mitigating the impact of the daily operations of the firm. Some businesses inevitably affect the surrounding society and environment. One way that firms can tackle SDGs is to minimise or offset this negative impact arising from the firms’ business operations. This course of action affects the process of business operations rather than business products themselves. However, it may affect the firms’ business positively, as consumers are also conscious of the impact of their consumer choice behaviour.

3. Using firm's non-financial resources (e.g. human resources) for actions unrelated to the main operations. Firms can use non-financial resources, such as employees, knowledge, technology, business networks and facilities to contribute to SDGs. Contrary to the first two channels, this one does not result directly in the development of new products, services or processes affecting the core operations of the firm. For example, some firms provide specialised technology or human resources for institutions that require it (e.g. NPOs, charities, other initiatives).

4. Donation/charity/philanthropy. Firms can contribute to SDGs by providing financial support to external organisations and activities such as NGOs, schools and environmental work. These contributions usually appear in firms’ sustainability report, but not as part of their business.

Examples of firms’ SDG actions

This subsection summarises the main lessons learnt from the analysis of 51 cases of firms’ SDG actions. It relies on 51 selected cases from the UNGC-KPMG industry matrices, the Global SDG Awards, the UNGC and company websites. It also presents in detail a few flagship examples of strategic uses of SDGs.

The cases are chosen to reflect the diversity of the firms’ contribution to SDGs. Some degree of representativeness of the sample is ensured through the survey design by setting quotas for different regions of the world, different sizes of firms and different industries (Annex A for the detail of the examples, and Box 2.4 for a focus on the financial sector). Even though this set of examples reflects the different objectives of firms, a particular emphasis is placed on strategic uses of SDGs. These examples, although not necessarily representative of the majority of firm’s actions (Table 2.2 and Annex A), are of particular relevance for policy measures.

Table 2.1. Joint distribution of firms’ objectives and channels

|

Objective/channel |

1. Core business |

2. Mitigating the impact of the daily operations of the firm |

3. Using firm's non-financial resources for actions unrelated to the main operations |

4. Donation/ charity/ philanthropy |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Strategic in-house contribution to SDGs |

31 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

34 |

|

2. Transformation of GVC and reinforcement of business strategy |

7 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

11 |

|

3. Mitigation of harm from GVC |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

4. Generic social impacts/good citizenship |

0 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

5 |

|

Total |

38 |

7 |

4 |

2 |

51 |

Sources: The cases were selected from UNGC and KPMG (2016[40]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Transportation”, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/4831; UNGC and KPMG (2016[41]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Industrial Manufacturing”, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/4351; UNGC and KPMG (2016[42]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Financial Services”, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/4001; UNGC and KPMG (2016[43]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Food, Beverage & Consumer Goods”, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/3961; UNGC and KPMG (2016[44]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Healthcare & Life Sciences”, https://unglobalcompact.org/library/4341; UNGC and KPMG (2017[45]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Energy, Natural Resources and Chemicals”, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/5061; firms’ websites and sustainability reports; and SDG awards (Canada and Japan).

Table 2.1 summarises the joint distribution of firms’ objectives and channels. While being mindful that that the 51 cases are not randomly selected, some interesting insights can be drawn. Unsurprisingly, the main insight is on the link between objectives and channels. The vast majority of firms willing to strategically use the SDGs, take actions linked to their core business, whereas other objectives can fit with any channel of action, including those that are not linked to the firms’ daily operations. In detail:

“Strategic in-house contributions to SDGs (objective)” are highly associated with firms’ “Core business (channel)”. However, the reverse is not necessarily true. “Core business (channel)” also serve to achieve “Transformation of GVC and business strategy (objective)”.

“Transformation of GVC and reinforcement of business strategy (objective)” are associated with “core business (channel)”, “Mitigating the impact of the daily operations of the firm (channel)” or “Using firm's non-financial resources for actions unrelated to the main operations (channel)”.

“Generic social impacts/good citizenship (objective)” are less likely to be linked to “Core business (channel)”, but are either linked to “Mitigating the impact of the daily operations of the firm (channel)” or “Donation/charity/philanthropy (channel)”.

Box 2.2. The United Nations Global Compact data

The UNGC is a voluntary initiative based on CEO commitments to implement universal sustainability principles and to take steps to support United Nations SDGs. The participants commit to embrace these principles and SDGs and to report on their progress. They benefit from networking and partnership opportunities, best practice guidance and a wide array of resources for advancing sustainability issues within their business. Rasche (2009[46]) describes the similarities and differences between the UNGC reporting and some other initiatives (GRI and SA8000). Van der Waal and Thijssens (2020[47]) show that UNGC participation is the main predictor of SDG involvement for the largest 2 000 listed businesses worldwide.

When discussing UNGC data, this book follows the regional, firm size and sectoral categories used by the 2020 UNGC survey. DNV GL and UNGC (2020[48]) provides descriptive statistics from this survey. The results may slightly differ from those provided in this book, which focuses on non-private sector organisations.

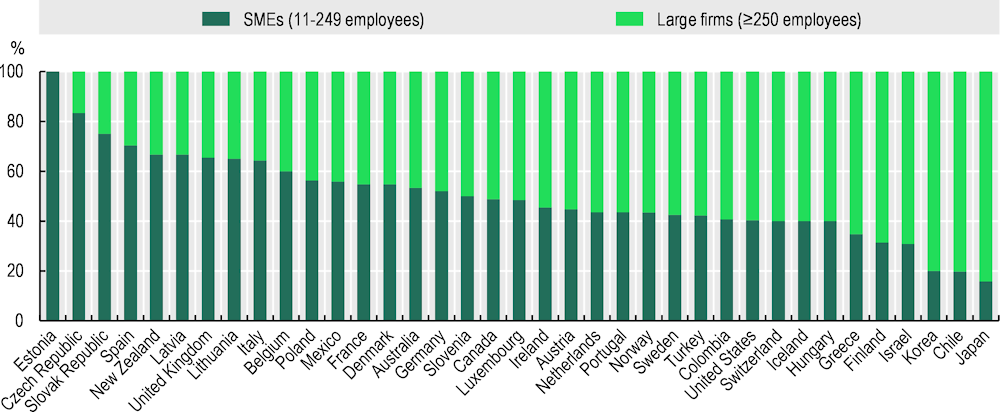

Figure 2.1. Firms’ participation in the UNGC, by employment size, across OECD countries

Notes: SMEs = small and medium-sized enterprises; UNGC = United Nations Global Compact.The classification of firm size relies on the definition of the UNGC. The data is as of 9 April 2020.

Source: OECD calculations based on UNGC’s participant list (not publicly available).

Composition of UNGC participants

The UNGC is one of the largest sustainability reporting frameworks. As of 2020, there are 9 214 private firms currently participating in the Compact. The participation in the UNGC by employment size is very heterogeneous across countries, with the share of SMEs (11 to 249 employees) ranging from less than 20% to 100% depending on the country.

Limitations

Although the use of UNGC data is insightful, some limitations have to be kept in mind. First, the data are self-reported by participating firms. Second, UNGC participation is voluntary and, for some firms, based on the payment of a fee. Thus, all the firms that take decisive actions do not necessarily participate in the UNGC. Third, the participation in the UNGC is not comparable across countries, either because of national policies or the activity of the UNGC. For this reason, analysis mainly focuses on the composition of participants rather than on the number of participants per country. The 2020 UNGC survey had around 600 respondents, representing approximately 6.5% of all private-sector participants.

Box 2.3. Why firms participate in sustainability reporting frameworks: stylised facts on the strategic reasons to participate to the UNGC

UNGC data can be used to shed light on the reasons disclosed by companies for their participation in the UNGC. These results must be evaluated with the knowledge that participation in the UNGC is voluntary, and subject to a fee. The participation in the UNGC, and hence to this survey, may thus be subject to a selection bias, which may vary across country, sector or company size.

Information available from the 2020 UNGC Survey Data

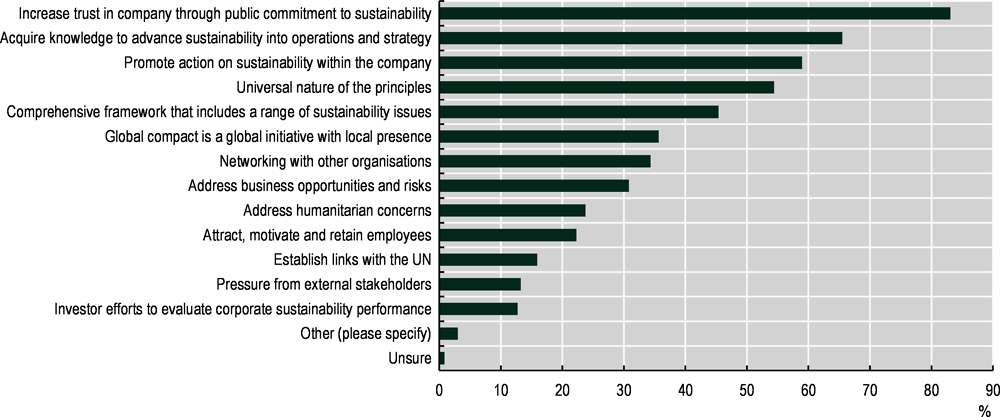

The main information used in this box comes from the 2020 UNGC Survey, Section I, question 6, which was completed by 597 firms. The companies are asked to rank “the top 5 reasons for [their] participation in the UN Global Compact”. The proposed answers are listed in Figure 2.2.

Although many reasons can be deemed strategic, this analysis focuses on the answers “Address business opportunities and risks” and “Attract, motivate and retain employees”, thereafter considered as strategic.

Most of the firms cite general reasons for participation in the UNGC. “Increase trust in company”, “acquire knowledge”, “promotes action on sustainability within the company” and “the universal nature of the principles” are cited by more than 50% of the firms as one the top five reasons for their participation. Each of the strategic reasons are cited by between 20% and 30% of the companies.

This pattern is even more striking when the analysis is focused on the top one or top two reasons, and is quite constant across time. The importance of strategic reasons even shows a slight decline over time, as firms become more eager to “acquire knowledge”, which was cited by only 30% of the respondents in 2010, compared to 65% in 2020.

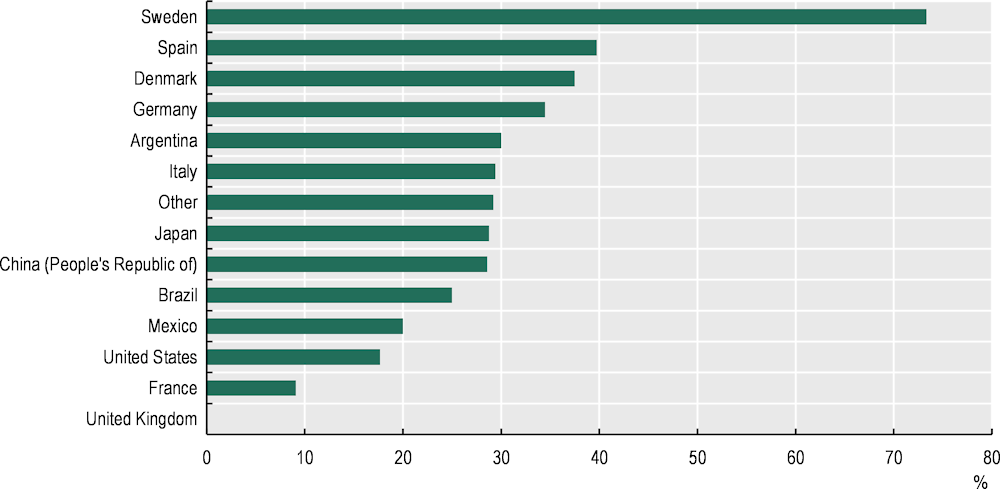

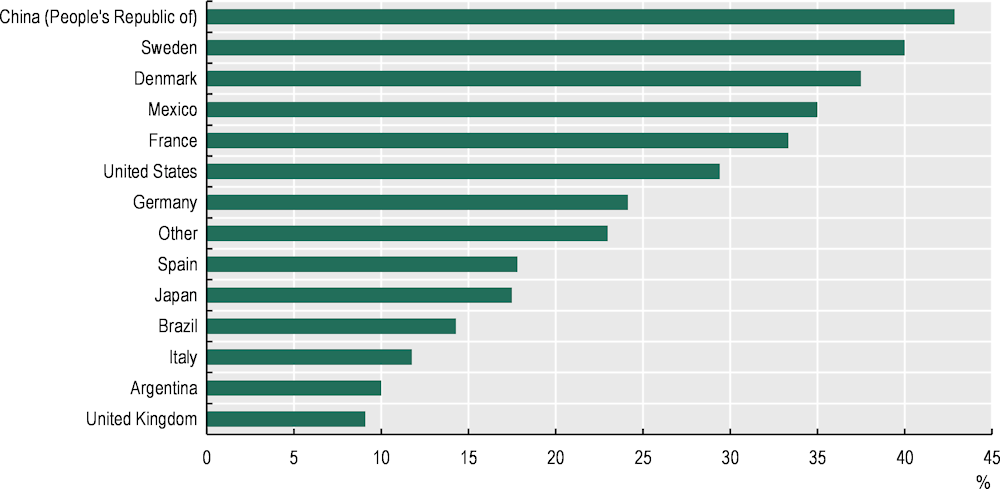

There is a considerable heterogeneity across countries, with the share of firms citing strategic reasons varying from 0% to almost 80% (Figure 2.3). However, due to different size and sectoral composition across countries, it is difficult to draw firm evidence or conclusions from these graphs.

Figure 2.2. Share of firms mentioning each reason among their top five

Note: UN = United Nations.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2020 UNGC survey (not publicly available).

Figure 2.3. Share of firms citing “Address business opportunities and risks” as one of their top five reasons

Note: Only countries with more than ten answering firms are listed. The rest of the countries are collated in the “Other” category.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2020 UNGC survey (not publicly available).

For this reason, a multivariate analysis is performed. The use of strategic reasons for UNGC participation is regressed on regional dummies, company size bins (headcount or turnover) and sectoral dummies. To account for the fact that the outcome variable is binary, a logit model is estimated. The following results stand out:

Firm size does not matter. The share of firms citing strategic reasons never depends on firm size, once the other variables are taken into account.

Firms in North America are three times less likely to cite a strategic reason than are European firms. This result is significant and robust across specifications. Other regions do not show a significantly different behaviour compared to Europe.

Firms in the “healthcare and life sciences” and “natural resources, energy and basic materials” sector are, respectively, three times and two times less likely to cite a strategic reason compared to firms in the manufacturing sector. This result is significant and robust across specifications. Other sectors do not show a significantly different behaviour compared to manufacturing firms.

Figure 2.4. Share of firms citing “Attract, motivate and retain employees” as one of their top five reasons

Note: Only countries with more than ten answering firms are listed. The rest of the countries are collated in the “Other” category.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2020 UNGC survey (not publicly available).

How firms are developing their business models around sustainability

These examples, along with an extant management literature, show that sustainability can be an economically viable option (circular economy, inclusive business models (Schoneveld, 2020[49]), gender equality (Bennett et al., 2020[50]), eco-innovation, etc.). Table 2.2 shows some of the most renowned and indicative cases of “strategic contributions to SDGs (objective)” through “core business (channel)” taken from the 51 cases. These strategic uses usually require structural changes. In particular, businesses need:

To show a strong commitment of corporate leaders. They not only need to devise a vision and common values, but also show emotional commitment in order to involve all relevant stakeholders (Kantabutra and Ketprapakorn, 2020[51]). This strategy must then be translated at the operational level by a network of SDG-oriented managers (Wolff et al., 2020[52]), be instilled into the corporate culture (García-Granero, Piedra-Muñoz and Galdeano-Gómez, 2020[53]) and, when relevant, be incorporated into R&D strategy. Examples in Table 2.2 require long-lasting R&D efforts, which would have been impossible without strong leadership. For example, Dulas has been consistently producing solar powered vaccine refrigeration since 1982, investing in R&D and innovation, and is now considered as a business success.

To demonstrate the business case for sustainable investments. Firms need performance indicators to track their return on investment and demonstrate that sustainability actions have a positive financial impact (Hristov and Chirico, 2019[54]). This is particularly important to convince stakeholders that business sustainability can be considered an intangible asset rather than a cost.

To adapt the business models. Sustainability must be embedded in a fully fledged business strategy (Rodrigues and Franco, 2019[55]). For instance, Blasi, Crisafulli and Sedita (2021[56]) put forward the example of firms willing to revisit their operations for more circularity. These firms often need to drastically change their business model, selling “solutions”3 rather than products. They also need to include their suppliers in their strategy (Elia, Gnoni and Tornese, 2020[57]). For example, Sompo Japan Nipponkoa Holdings (Table A.4) has developed a new line of products related to agriculture, by creating weather index insurance in Southeast Asia to smoothen the impact of climate change on farmers.

To communicate with customers about their sustainable strategies and practices. Communication is needed to advertise the impact of the company. Using a sample of Italian SMEs, Blasi, Crisafulli and Sedita (2021[56]) show that the promotional efforts of circular practice improve performance. The four firms in Table 2.2 clearly communicate their missions and SDG actions, either on their websites or in sustainability reports. But communication is also required to ensure that the new sustainable business model corresponds to the expectations of stakeholders, including – but not limited to – customers. Building on case studies, Bashir et al. (2020[58]) and Aminoff and Pihlajamaa (2020[59]) argue that the introduction of new sustainable products and services may require trial and error, a process which is made more fluid by communication with customers; for instance based on experiments and small-scale tests, and which can leverage on digital technologies (Gregori and Holzmann, 2020[60]). Firms are also expected to convey their sustainability strategy and corresponding SDG actions to their stakeholders, as they gain more roles and responsibilities in society. Finally, as many firms are trying to ride the wave of sustainability, firms’ actions also need to be distinguishable from competitors doing “SDG-washing” (i.e. window-dressing actions that are not directly related to or motivated by sustainability, or communicating only positive impacts of the business while hiding the negative impacts).

Box 2.4. SDGs and the role of the financial sector

Sustainable development initiatives undertaken by the financial industry act as a catalyst to channel funds to the most sustainable companies and to encourage other industries to become more sustainable. Hence, sustainability initiatives in the financial sector, which often have cross-border influence, have a pervasive impact on other industries, countries and individuals.

As an intermediary between depositors/investors (e.g. households) and borrowers (e.g. firms), the financial sector has a crucial role in channelling savings to sustainable businesses. For example, large commercial banks (e.g. Standard Chartered and Banco do Brazil in Annex A) provide financing and technical assistance for microfinance.

This has been translated into several investment policies, notably ESG investing and social impact investment (SII). More generally, financial institutions are also proposing “sustainable” financial products. To that end, they rely on available non-financial information, for instance ESG rating (Box 1.1).

ESG investing aims to “better incorporate long-term financial risks and opportunities into their investment decision-making processes to generate long-term value.” (Boffo and Patalano, 2020[61]).

SII, including both social investing and impact investment, “provides finance to organisations addressing social and/or environmental needs with the explicit expectation of measurable social and financial returns. It is a new way of channelling new resources towards the Sustainable Development Goals.” (OECD, 2019[62]) For example, Aavishkaar Group (Table 2.2), a well-recognised frontrunner of SII, has incubated social entrepreneurs addressing 13 different SDGs and has indirectly benefitted more than 100 million underserved customers in South Asia, Southeast Asia and East Africa (D’Souza, 2020[63]).

Table 2.2. Indicative examples of SDG actions (core business strategic contributions to the SDGs)

|

Country |

Industry |

Employment size |

SDGs |

Description of the action |

Objective of action |

Channel of action |

UNGC participation |

Use of GRI standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

United Kingdom |

1. Energy, natural resources and chemicals |

≤250 |

3 |

“Dulas Ltd has developed solar powered medical fridges that are used in remote regions across Africa, Asia, the Pacific Islands and Latin America to store blood and vaccines. The company is a major supplier of these fridges which are being used in numerous successful national immunisation programs in hospitals, clinics, health centres and remote medical stations around the world. These have been approved by the strict Performance, Quality and Safety protocol set by the World Health Organisation and feature independent freezer compartments and a durable sealed battery delivering continuous cooling to keep vaccines safe. The solar system provides secure constant power including a five day back up.” (UNGC and KPMG, 2017[45]). Dulas encountered success, doubling its sales between 2015 and 2017 (Torres-Rahman, 2018[64]). |

1. Strategic in-house contribution to SDGs |

1. Core business |

Yes |

No |

|

India |

2. Financial services |

>3 000 |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 17 |

Aavishkaar Group, known for building business that can benefit the underserved segments across Asia and Africa in sectors such as transport, healthcare, basic financial services and other services, comprises equity funds, a venture debt vehicle, a microfinance and advisory business including investment banking. Achievement of Aavishkaar Capital, the equity investment entity of Aavishkaar Group and one of the largest impact investors in Asia, includes 1) approximately 87% of its portfolio companies having Aavishkaar Capital as their first institutional investor, 2) 93 million people receiving improved access to essential products and services in the areas including education, healthcare, WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) and financial services, and 3) investing into sectors that are aligned with the 13 SDGs. (D’Souza, 2020[63]).. |

1. Strategic in-house contribution to SDGs |

1. Core business |

No |

No |

|

Netherlands |

4. Healthcare and life science |

>3 000 |

2, 3, 7, 12, 13 |

“Royal DSMs NutriRice uses innovative hot extrusion technology with encapsulated micronutrients to preserve the nutrients typically lost during milling and food preparation. This is an important innovation given that rice is the staple food of more than half of the world’s population, yet it contains few vitamins and minerals. NutriRice uses rice flour as a raw material and kernels are mixed with natural rice at a ratio of 0.5-2.0%. NutriRice kernels look, taste and behave exactly like normal rice. In a poor urban setting in Bangalore, India, DSM collaborated with the St. Johns Research Institute to conduct a trial to study the effects of NutriRice on school children aged 6-12 years. After six months the children’s B-vitamin status had improved significantly and there was an improvement in physical performance, particularly physical endurance, among the children who consumed NutriRice.” (UNGC and KPMG, 2016[44]). |

1. Strategic in-house contribution to SDGs |

1. Core business |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Italy |

5. Industrial manufacturing |

>250 and ≤3 000 |

4, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 15, 16 |

“Thanks to continuous research and collaboration with various stakeholders, in 2011, the Aquafil Group completed the transformation of Nylon 6 waste into regenerated ECONYL yarn, maintaining the same quality level and performance, but by significantly reducing environmental impact. Regenerated nylon is used by a growing number of companies in the carpet and fashion sectors, including some of the world's leading fashion houses.” (Aquafil, 2020[65]). |

1. Strategic in-house contribution to SDGs |

1. Core business |

No |

Yes |

Notes: SDG = Sustainable Development Goal; GRI = Global Reporting Initiative; UNGC = United Nations Global Compact. The table is organised by industry and country (alphabetical). The actions and corresponding SDGs only describe parts of the sustainability strategy of those firms.

Sources: The cases were selected from UNGC and KPMG (2016[40]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Transportation”, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/4831; UNGC and KPMG (2016[41]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Industrial Manufacturing”, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/4351; UNGC and KPMG (2016[42]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Financial Services”, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/4001; UNGC and KPMG (2016[43]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Food, Beverage & Consumer Goods”, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/3961; UNGC and KPMG (2016[44]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Healthcare & Life Sciences”, https://unglobalcompact.org/library/4341; UNGC and KPMG (2017[45]), “SDG Industry Matrix: Energy, Natural Resources and Chemicals”, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/5061; firms’ websites and sustainability reports; and SDG awards (Canada and Japan).

SDG orientation of firms: Quantitative evidence from the UNGC participating firms

This subsection analyses firms’ SDG orientation using the 2020 United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) annual survey results (see Box 2.2 on the description of the UNGC data). The 2020 version of the annual survey is well suited for this report because the questions related to SDGs are more specific than in previous years. A section of the annual survey is dedicated to the actions and impacts of companies that are related to the SDGs. It includes, for example, questions on firms’ motivation for sustainability, the company’s actions related to the SDGs, a self-assessment of the company’s positive and negative impacts on the SDGs, the firms’ stated prioritisation of the SDGs for their business, and more.

The results of the survey should not be over-interpreted, even though this is a valuable resource for policymakers and business community. The main caveat comes from the fact that answers reflect firms’ own perceptions rather than an objective measure of reality. The sustainability reporting frameworks still suffer from the lack of a systematic and internationally standardised approach linking business actions and impacts with the SDGs.

SDG orientation of firms

This subsection presents quantitative evidence on the SDG orientation of firms, using the 2020 UNGC survey dataset, which was answered by 597 firms (hereafter the firms) from 78 countries, and excluded non-business organisations. The survey provides information on how firms perceive and tackle the SDGs, complementing the qualitative analysis on the typology and examples of firms’ SDG actions in the previous subsection. It has some limitations and sample bias (Box 2.2); for instance, UNGC participating firms are more likely to be frontrunners in terms of sustainability.

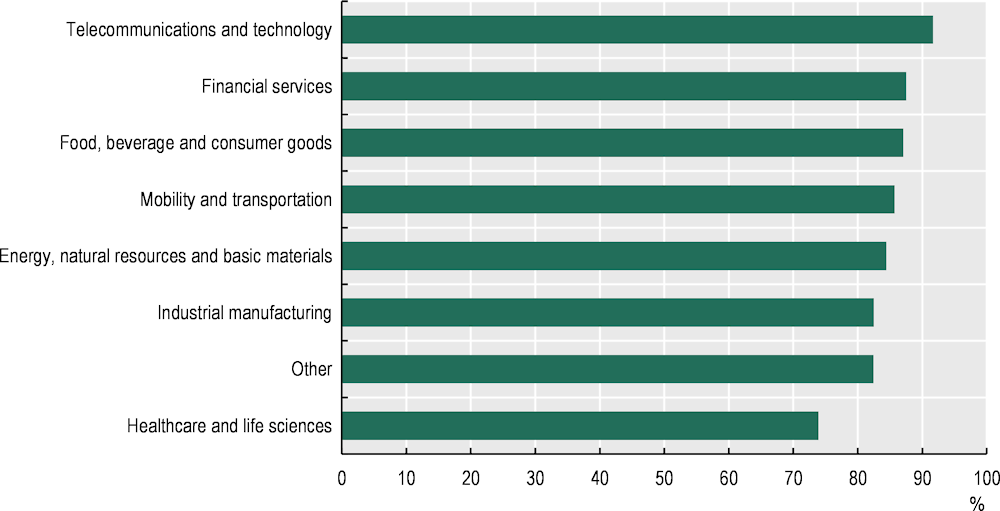

The vast majority of respondent firms answered that they take actions to advance the SDGs (Figure 2.5). The highest share (92%) is found in the technology and telecommunications sector, and the lowest in the healthcare and life sciences sector (74%).

Figure 2.5. Share of firms taking actions to specifically advance the SDGs, by mega sector

Notes: SDG = Sustainable Development Goal. The original question was: “Does your company take actions to specifically advance the Sustainable Development Goals?”.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2020 UNGC survey (not publicly available).

On average, firms consider themselves to have a positive impact on each of the SDGs (Table 2.3). This is particularly so for SDG 3-Good Health and Well-Being, SDG 5-Gender Equality, SDG 8-Decent Work and Economic Growth, SDG 9-Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure and SDG 12-Responsible Consumption and Production, while less strong for SDG 1-No Poverty, SDG 2-Zero Hunger, SDG 14-Life Below Water, SDG 15-Life on Land and SDG 16-Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions. The results are relatively consistent across sectors. The healthcare and life sciences sector indicates a very positive impact for SDG 3. The mobility and transportation sector considers itself as having a high impact on SDGs 3, 8, 9, 11-Sustainable Cities and Communities, and 12.

Table 2.3. Firms’ self-evaluation of their impact on each of the SDGs

Average score of firm’s self-evaluation of their current impact on each of the SDGs, by sector

|

SDG 1 |

SDG 2 |

SDG 3 |

SDG 4 |

SDG 5 |

SDG 6 |

SDG 7 |

SDG 8 |

SDG 9 |

SDG 10 |

SDG 11 |

SDG 12 |

SDG 13 |

SDG 14 |

SDG 15 |

SDG 16 |

SDG 17 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All sectors |

0.8 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

|

By mega sector: |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Energy, natural resources and basic materials |

0.7 |

0.6 |

1.1 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

|

Financial services |

0.8 |

0.6 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

|

Food, beverage and consumer goods |

0.9 |

0.8 |

1.3 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

1.1 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

1.1 |

|

Healthcare and life sciences |

0.7 |

0.7 |

1.7 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

0.7 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

|

Industrial manufacturing |

0.8 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

|

Mobility and transportation |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

1.1 |

|

Telecommuni-cations and technology |

0.6 |

0.4 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

|

Other |

0.8 |

0.7 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

1.3 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

Notes: SDG = Sustainable Development Goal. The original question was: “From your perspective, what would you say is your company’s current impact on each of the Global Goals?”. A higher score corresponds to a more positive impact. On a scale of -2 to 2, where -2= Significant negative impact, -1= Somewhat negative impact, 0= No impact or not aware of the impact that our company has on this goal, 1= Somewhat positive impact and 2= Significant positive impact. The colours in the cells vary from blue (the largest value) to white (the value at the 50th percentile) to red (the lowest value).

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2020 UNGC survey (not publicly available).

In recent years, it became more common for firms to indicate their SDG prioritisation/orientation on their websites or in their sustainability reports. Table 2.4 shows the SDG prioritisation by firms in the UNGC 2020 survey, as well as in other surveys. In the UNGC 2020 survey, the most widely prioritised SDGs were SDG 3-Good Health and Well-Being, SDG 5-Gender Equality, SDG 8-Decent Work and Economic Growth, SDG 9‑Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, SDG 12-Responsible Consumption and Production and SDG 13-Climate Action (in numeric order). This ranking result is consistent with survey results of the world's top 250 companies by revenue (G250) and of the top 150 Australian publicly listed companies (ASX150), despite some differences in absolute share (KPMG International, 2018[66]; RMIT and UNAA, 2020[67]). Therefore, in Chapter 5, policies targeting these highly prioritised SDGs are particularly scrutinised.

Table 2.4. SDG prioritisation by firms

Share of firms prioritising each SDG, and ranking of perceived relevance of SDGs for the private sector

|

SDG 1 |

SDG 2 |

SDG 3 |

SDG 4 |

SDG 5 |

SDG 6 |

SDG 7 |

SDG 8 |

SDG 9 |

SDG 10 |

SDG 11 |

SDG 12 |

SDG 13 |

SDG 14 |

SDG 15 |

SDG 16 |

SDG 17 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

UNGC 2020 survey (%) |

18 |

15 |

46 |

32 |

43 |

23 |

33 |

54 |

41 |

27 |

27 |

45 |

45 |

11 |

17 |

20 |

35 |

|

G250 survey (%) |

28 |

21 |

55 |

51 |

52 |

34 |

48 |

59 |

48 |

39 |

46 |

54 |

64 |

18 |

26 |

32 |

34 |

|

ASX150 2019 survey (%) |

11 |

5 |

26 |

20 |

31 |

15 |

25 |

37 |

27 |

25 |

25 |

31 |

37 |

9 |

17 |

17 |

19 |

|

SDG Barometer 2020 (ranking) |

14 |

17 |

2 |

8 |

7 |

12 |

6 |

1 |

3 |

9 |

10 |

4 |

5 |

16 |

13 |

15 |

11 |

Notes: SDG = Sustainable Development Goal. The share of firms (%) prioritising each of the SDGs in three different surveys (UNGC 2020 survey, G250 survey and ASX150 2019 survey) is shown in roman type, and the ranking of perceived relevance of SDGs for the private sector (SDG Barometer 2020) is shown in italics. The original question in the 2020 UNGC survey was “Which of the following Global Goals does your company currently prioritise? Select all that apply”. The colours of the cells vary gradually from red (the largest value) to white (the value at the 50th percentile) to blue (the lowest value) for the first three rows.

SDG Barometer 2020 represents 803 Belgian organisations, of which 60% are private sector. The results shown in the figure are restricted to the private sector and display their ranking of the SDGs (1 for the SDG deemed the most relevant to 17 for the one deemed the least relevant). The colours of the cells vary gradually from blue (the lowest value) to white (the value at the 50th percentile) to red (the largest value).

The colours are applied for each row to highlight the relative difference within each row.

Sources: OECD calculations based on the 2020 UNGC survey (not publicly available); KPMG International (2018[66]), “How to report on the SDGs”, https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2018/02/how-to-report-on-sdgs.pdf; RMIT and UNAA (2020[67]), “SDG Measurement and Disclosure 2.0: A study of ASX150 companies”, https://www.unaa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/UNAA-RMIT-ASX-150-SDG-Report.pdf; Antwerp Management School and the University of Antwerp (2020[68]), “SDG Barometer 2020”, https://cdn.uclouvain.be/groups/cms-editors-ilsm/csr-louvain-network/documents/rv_stl_sdg_barometer_2020_EN.pdf.

Similarly, in a recent survey of over 480 Belgian firms, the perceived relevance of SDGs for firms – which can be seen as a proxy for SDG prioritisation – indicated a similar pattern (Antwerp Management School and the University of Antwerp, 2020[68]). However, interestingly, this order differs significantly for government organisations, non-governmental organisations and educational institutions, confirming that firms have different roles than other organisations, as discussed in section “Firms can complement governments and households in the pursuit of SDGs”.

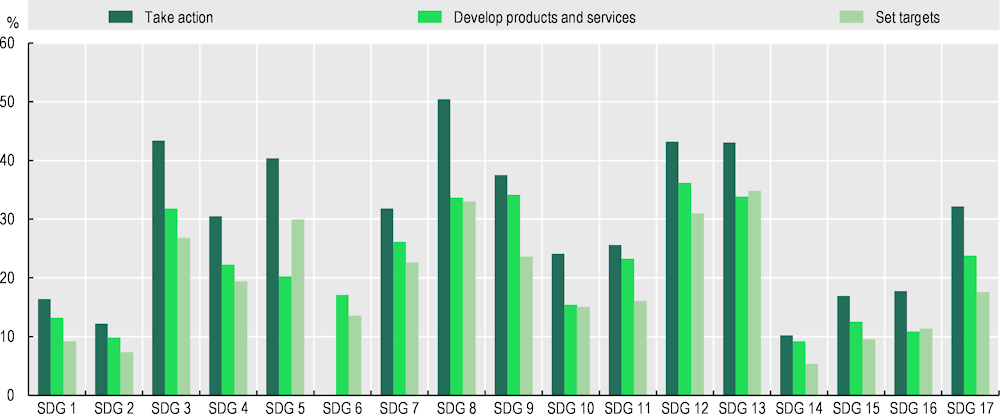

The share of firms taking action varies across the SDGs, ranging from 10% (SDG 14-Life Below Water) to 50% (SDG 8-Decent Work and Economic Growth) (Figure 2.6). The share of firms that develop products and services related to that SDG (i.e. close to what is defined as “core business” in previous sections), is lower than the share of those taking action, as actions include broader business activities. Across SDGs, the share of firms setting targets is even lower, except for SDG 5-Gender Equality, SDG 13-Climate Action and SDG 16-Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions.

Among the respondents, the propensity to take action related to a given SDG is very heterogeneous across region, firm size and sector (Table 2.5). In order to disentangle the influence of these three characteristics, a logistic regression is conducted, using the answer to the question “Does your company take action on Goal X? (Yes/No)” as a dependent variable, and region, firm size and sector dummies as independent variables. As a result, for example, compared to European firms, Asian firms are less likely to act on SDG 5-Gender Equality and SDG 16-Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions. For SDG 1-No Poverty, firms in Africa, Asia and Latin America are more likely to take actions compared to European firms. Firms in the energy, natural resources and basic materials sector, financial services sector, food beverage and consumer goods sector, mobility and transportation sector, and other sectors, are more likely to take actions for SDG 1 compared to firms in industrial manufacturing sector.

Figure 2.6. Firms’ actions and targets for each SDG

Notes: SDG = Sustainable Development Goal. For each SDG, the original questions were: “Has your company set targets to advance Goal X?”, “Does your company develop products and services that contribute to Goal X?” and “Does your company take action on Goal X?”. The data for “Take action (SDG 6)” are unavailable.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2020 UNGC survey (not publicly available).

In general, the larger the firm, the higher is the probability to take action. Very large firms (>50 000) are more likely to take action on all SDGs except SDG 3-Good Health and Well-Being, SDG 10-Reduced Inequalities, SDG 12-Responsible Consumption and Production, and SDG 15-Life on Land than SMEs (<250). Large firms (5 000-50 000) are more likely to take action on SDG 4-Quality Education, SDG 5‑Gender Equality, SDG 7-Affordable and Clean Energy, SDG 8-Decent Work and Economic Growth, SDG 9-Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, SDG 10; SDG 11-Sustainable Cities and Communities, SDG 12-Responsible Consumption and Production, SDG 13-Climate Action, SDG 16‑Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions, and SDG 17-Partnerships for the Goals than SMEs (<250). Firms in the financial sector are more likely to take action on SDGs 1, 8, 10 and 17 than are firms in the industrial manufacturing sector. While some of the patterns found in this analysis (e.g. the food, beverage and consumer goods sector’s relative focus on SDG 2-Zero Hunger, and the energy, natural resources and basic materials sector’s relative focus on SDGs 7 and 13) were expected, others (e.g. the financial systems sector’s relative focus on SDG 1-No Poverty and the telecommunications and technology sector’s relative focus on SDGs 5 and 10) were less so.

Although this result underlines that small firms may be at a disadvantage in the transition to sustainability, compared to large firms, it does not mean that SMEs’ contribution to the SDGs should be overlooked. First, SMEs constitute the vast majority of firms and a sizeable share of economic activities in most OECD countries. Their impact on sustainable development is therefore of utmost importance. Second, the very existence of SMEs can contribute to the SDGs, for instance by providing employment to their founders and local communities.

As this book focuses on the firms’ contribution to the SDGs particularly via core businesses, Table 2.6 provides very useful insights on firms’ developments of products and services linked to SDGs. Table 2.6 also presents the results of a logistic regression, using the answer to the question “Does your company develop products and services that contribute to Goal X? (Yes/No)” as a dependent variable, and region, firm size and sector dummies as independent variables. The results are similar to the ones in Table 2.5, but also exhibit some interesting differences. For example, compared to the European firms, the Latin American firms are more likely to develop products and services on SDG 1-No Poverty, SDG 4-Quality Education, SDG 8‑Decent Work and Economic Growth, and SDG 16-Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions. As for actions, the propensity to develop SDG-related goods and services increases with size for most of the SDGs. Firms in the financial sector are more likely to develop products and services related to the SDGs 1, 4, SDG 5-Gender Equality, 8, SDG 10-Reduced Inequalities and SDG 17-Partnerships for the Goals compared to firms in the industrial manufacturing sector. The technology and telecommunication sector is more likely to develop products and services on SDGs 4, 8, and 10, but less likely on SDG 6‑Clean Water and Sanitation, compared to firms in the industrial manufacturing sector.

Table 2.5. Firms’ likelihood of taking action on SDGs

Odds ratio of firms taking actions for each SDG, by region, headcount and mega sector, compared to the benchmark categories

|

SDG 1 |

SDG 2 |

SDG 3 |

SDG 4 |

SDG 5 |

SDG 7 |

SDG 8 |

SDG 9 |

SDG 10 |

SDG 11 |

SDG 12 |

SDG 13 |

SDG 14 |

SDG 15 |

SDG 16 |

SDG 17 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Region (benchmark: Europe) |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Africa |

7.7 |

2.7 |

|||||||||||||||

|

Asia |

2.1 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

|||||||||||||

|

Latin America |

2.9 |

||||||||||||||||

|

MENA |

0.3 |

||||||||||||||||

|

North America |

4.4 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Headcount (benchmark: <250) |

|||||||||||||||||

|

250-4 999 |

2.2 |

1.6 |

2.4 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

1.6 |

|||||||||||

|

5 000-50 000 |

2.4 |

1.9 |

2.1 |

4.2 |

3.8 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

3.4 |

4.5 |

3.6 |

2.8 |

||||||

|

>50 000 |

3.0 |

3.7 |

5.1 |

5.4 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

6.8 |

12.5 |

3.5 |

6.4 |

|||||||

|

Megasector (benchmark: industrial manufacturing) |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Energy, natural resources and basic materials |

2.4 |

3.4 |

2.4 |

1.9 |

2.4 |

||||||||||||

|

Financial services |

3.2 |

2.3 |

2.1 |

2.4 |

|||||||||||||

|

Food, beverage and consumer goods |

2.6 |

5.8 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|||||||||||||

|

Healthcare and life sciences |

0.3 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Mobility and transportation |

3.6 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Telecommunications and technology |

1.8 |

2.5 |

|||||||||||||||

|

Other |

2.3 |

2.6 |

1.7 |

0.5 |

|||||||||||||

Notes: MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SDG = Sustainable Development Goal. This table is a result of a logistic regression model (blank squares indicate no statistically significant difference). For each SDG, the original question was: “Does your company take action on Goal X?”. 597 firms were surveyed. Showing the statistically significant results only at p <.05 level. Asia includes Oceania. For each variable, the benchmark category is excluded from this figure. “Odds ratio = 1” means just as likely as the comparison group (small firms [<250]). The results are based on self-reported data by participating firms. The data for SDG 6 are unavailable. The colours of the cells vary gradually from red (the largest value) to white (not significantly different from 1.0) to blue (the lowest value).

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2020 UNGC survey (not publicly available).

Comparing to the relative likelihood of answering the question positively for very large firms (>50 000) compared to SMEs (<250) remains similar, and is even reinforced for SDG 1-No Poverty, SDG 3-Good Health and Well-Being and SDG 10-Reduced Inequalities, while it disappears for SDG 16‑Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions.

Table 2.6. Firms’ likelihood of developing products and services that contribute to SDGs

Odds ratio of firms developing products and services contributing to each SDG, by region, headcount and mega sector, compared to the benchmark categories

|

SDG 1 |

SDG 2 |

SDG 3 |

SDG 4 |

SDG 5 |

SDG 6 |

SDG 7 |

SDG 8 |

SDG 9 |

SDG 10 |

SDG 11 |

SDG 12 |

SDG 13 |

SDG 14 |

SDG 15 |

SDG 16 |

SDG 17 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Region (benchmark: Europe) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Africa |

7.6 |

4.2 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Asia |

2.5 |

1.8 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Latin America |

3.9 |

2.0 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

MENA |

3.2 |

2.6 |

0.3 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

North America |

0.2 |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Headcount (benchmark: <250) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

250-4 999 |

1.7 |

2.5 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

5 000-50 000 |

2.6 |

1.8 |

2.7 |

3.4 |

2.2 |

2.7 |

2.9 |

2.6 |

1.8 |

||||||||||||

|

>50 000 |

4.0 |

3.8 |

2.8 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

5.6 |

3.2 |

3.0 |

3.5 |

7.8 |

13.5 |

5.4 |

|||||||||

|

Megasector (benchmark: industrial manufacturing) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Energy, natural resources and basic materials |

3.1 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Financial services |

4.3 |

2.3 |

2.8 |

2.7 |

2.5 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Food, beverage and consumer goods |

5.6 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Healthcare and life sciences |

3.7 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Mobility and transportation |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Telecommunications and technology |

2.2 |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other |

2.6 |

3.3 |

2.4 |

1.9 |

|||||||||||||||||

Notes: MENA = Middle East and North Africa. This table is a result of a logistic regression model (blank squares indicate no statistically significant difference). For each SDG, the original questions was: “Does your company develop products and services that contribute to Goal X?”. 597 firms were surveyed. This table shows the statistically significant results only at p <.05 level. Asia includes Oceania. For each variable, the benchmark category is excluded from this table. The colours of the cells vary gradually from red (the largest value) to white (not significantly different from 1.0) to blue (the lowest value).

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2020 UNGC survey (not publicly available).

Channel of firms’ SDG actions

In section “Typology of firms’ SDG actions”, this book categorised firms’ sustainability actions into four main channels:

1. core business

2. mitigating the impact of the daily operations of the firm

3. using firm's non-financial resources (e.g. human resources) for actions unrelated to the main operations

4. donation/charity/philanthropy.

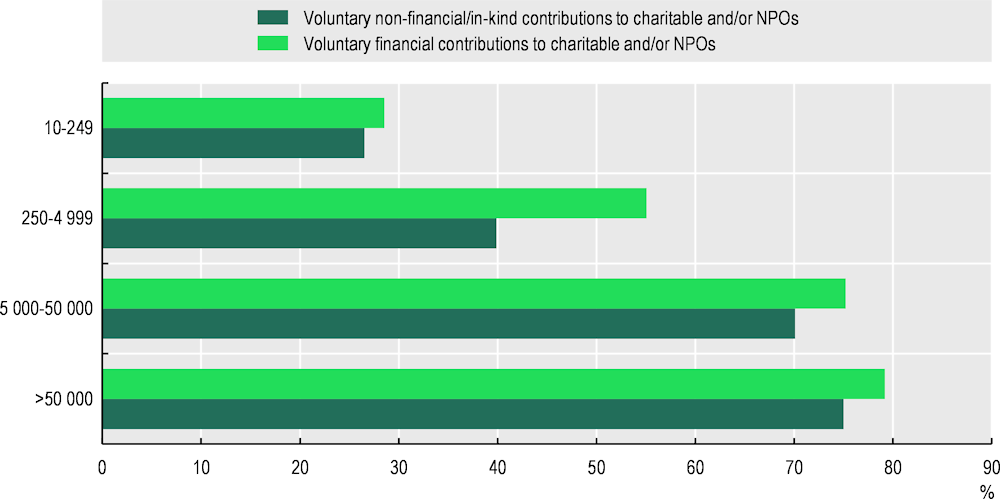

The UNGC survey also provides information on the channels of action used by companies (Figure 2.7), and this information can be linked to the four main channels distinguished in section “How firms tackle SDGs in practice”. “Voluntary non-financial/in-kind contributions to charitable and/or non-profit organisations (NPOs)” can be considered as belonging to category “3. Using firm's non-financial resources for actions unrelated to the main operations” and “Voluntary financial contributions to charitable and/or non-profit organisations (NPOs)” can be considered almost equivalent to “4. Donation/charity/philanthropy”. The share of firms using these two channels increases with firm size, from 27% to 29% for SMEs (<250) to more than 75% for very large firms (>50 000). This pattern is confirmed by a logistic regression controlling simultaneously for firm size, region and sector. This regression shows no significant difference across regions nor sectors.

Figure 2.7. Share of firms providing financial and non-financial contributions to charity

Social investment and philanthropy actions, by employment size

Notes: NPO = non-profit organisation. The original question was: “How does your company take action to contribute to the Global Goals?”. The legend lists the multiple-answer options.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2020 UNGC survey (not publicly available).

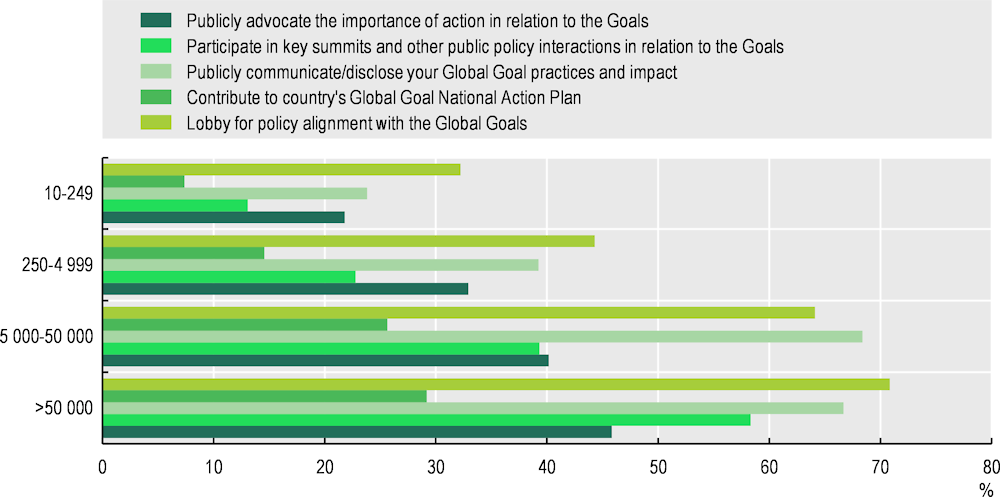

Figure 2.8. Share of firms taking advocacy and public policy actions, by employment size

Notes: The original question was: “How does your company take action to contribute to the Global Goals?”. The legend lists the multiple-answer options.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2020 UNGC survey (not publicly available).

The survey also asks firms whether they undertake “Advocacy and public policy actions”, which can correspond to most of the channels described in section “How firms tackle SDGs in practice”, but is mainly linked to “3. Using firm's non-financial resources for actions unrelated to the main operations”. The share of firms taking advocacy and public policy actions also increase by firm size (Figure 2.8). For example, “Publicly communicate/disclose your Global Goal practices and impacts” increases from 24% for SMEs (<250) to 67% for very large firms (>50 000). This pattern is confirmed by a logistic regression controlling simultaneously for firm size, region and sector. This regression shows no significant difference across regions nor sectors.

References

[35] Albinger, H. and S. Freeman (2000), “Corporate social performance and attractiveness as an employer to different job seeking populations”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 28/3, pp. 243-253, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006289817941.

[18] Alexander, G. and R. Buchholz (1978), “Corporate social responsibility and stock market performance”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 21/3, pp. 479-486, https://doi.org/10.5465/255728.

[20] Ambec, S. et al. (2013), “The Porter hypothesis at 20: Can environmental regulation enhance innovation and competitiveness?”, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, Vol. 7/1, pp. 2-22, https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/res016.

[59] Aminoff, A. and M. Pihlajamaa (2020), “Business experimentation for a circular economy - Learning in the front end of innovation”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 275, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124051.

[68] Antwerp Management School and the University of Antwerp (2020), “SDG Barometer 2020”, https://cdn.uclouvain.be/groups/cms-editors-ilsm/csr-louvain-network/documents/rv_stl_sdg_barometer_2020_EN.pdf.

[65] Aquafil (2020), “The Eco Pledge: Aquafil’s path toward full sustainability”, https://www.aquafil.com/sustainability/the-eco-pledge/ (accessed on 8 October 2020).

[3] Baron, D. (2007), “Corporate social responsibility and social entrepreneurship”, Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, Vol. 16/3, pp. 683-717, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9134.2007.00154.x.

[58] Bashir, H. et al. (2020), “Experimenting with sustainable business models in fast moving consumer goods”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 270, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122302.

[4] Bénabou, R. and J. Tirole (2010), “Individual and corporate social responsibility”, Economica, Vol. 77/305, pp. 1-19, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00843.x.

[50] Bennett, B. et al. (2020), “Paid leave pays off: The effects of paid family leave on firm performance”, NBER Working Papers, No. 27788, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27788.

[15] Boakye, D. et al. (2021), “The relationship between environmental management performance and financial performance of firms listed in the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) in the UK”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 278, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124034.

[61] Boffo, R. and R. Patalano (2020), “ESG investing: Practices, progress and challenges”, https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-Investing-Practices-Progress-Challenges.pdf.

[29] Boubaker, S. et al. (2020), “Does corporate social responsibility reduce financial distress risk?”, Economic Modelling, Vol. 91, pp. 835-851, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2020.05.012.

[27] Carroll, A. and K. Shabana (2010), “The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice”, International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 12/1, pp. 85-105, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00275.x.

[31] Chintrakarn, P., P. Jiraporn and S. Treepongkaruna (2021), “How do independent directors view corporate social responsibility (CSR) during a stressful time? Evidence from the financial crisis”, International Review of Economics & Finance, Vol. 71, pp. 143-160, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2020.08.007.

[33] Chuah, S. et al. (2020), “Sustaining customer engagement behavior through corporate social responsibility: The roles of environmental concern and green trust”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 262, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121348.

[6] Coase, R. (1960), “The problem of social cost”, in Classic Papers in Natural Resource Economics, Palgrave Macmillan UK, London, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230523210_6.

[7] Costello, C. and M. Kotchen (2020), “Policy instrument choice with Coasean provision of public goods”, NBER Working Papers, No. 28130, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, https://doi.org/10.3386/w28130.

[63] D’Souza, R. (2020), “Impact investments in India: Towards sustainable development”, ORF Occasional Paper, No. 256, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi, https://www.orfonline.org/research/impact-investments-in-india-towards-sustainable-development-68378/.

[22] Dechezleprêtre, A. et al. (2019), “Do environmental and economic performance go together? A review of micro-level empirical evidence”, International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Vol. 13/1-2, pp. 1-118, https://doi.org/10.1561/101.00000106.

[21] Dechezleprêtre, A. and M. Sato (2017), “The impacts of environmental regulations on competitiveness”, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, Vol. 11/2, pp. 183-206, https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rex013.

[30] Ding, W. et al. (2020), “Corporate immunity to the COVID-19 pandemic”, NBER Working Papers, No. 27055, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27055.

[57] Elia, V., M. Gnoni and F. Tornese (2020), “Evaluating the adoption of circular economy practices in industrial supply chains: An empirical analysis”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 273, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122966.

[12] Endo, K. (2013), “Does stakeholder welfare enhance firm value?”, Economics Today, [in Japanese], https://www.dbj.jp/ricf/pdf/research/DBJ_EconomicsToday_34_02.pdf.

[2] Friedman, M. (1970), “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits”, New York Times Magazine, https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html.

[17] Galant, A. and S. Cadez (2017), “Corporate social responsibility and financial performance relationship: A review of measurement approaches”, Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, Vol. 30, pp. 676-693, https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2017.1313122.