This chapter explores the factors that drive economic inactivity in Poland, across target groups and places. The chapter highlights both group and regional level characteristics as potential explanations for differences in economic inactivity across Polish regions, emphasizing historical factors that put regions on differing trajectories. The chapter then sets economic inactivity within broader labour market megatrends. Polarisation, automation and the green transition are accentuating labour market divergences between people and regions.

Regional Economic Inactivity Trends in Poland

3. Drivers of economic inactivity in Polish regions

Abstract

In Brief

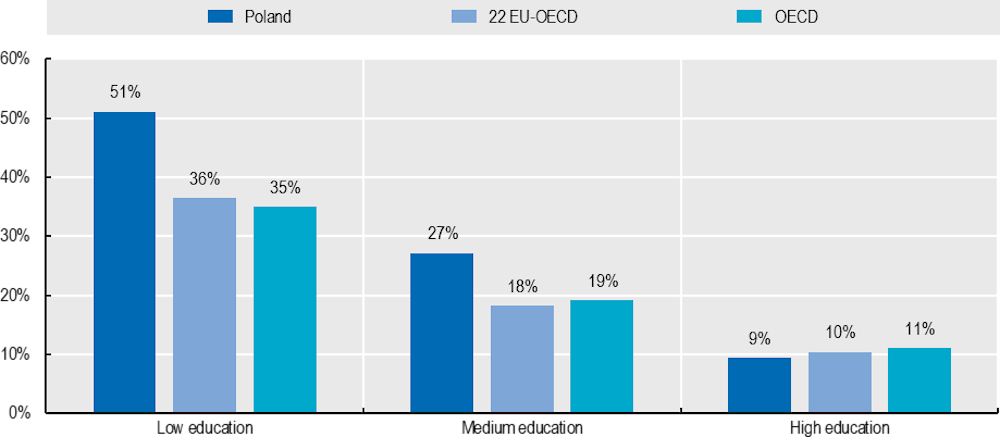

Low education is a key driver of economic inactivity in Poland. In Poland, 51% of those with less than upper secondary education are economically inactive. This number compares to 35% in the whole of the OECD. Thus, people with low education levels present a large unexploited resource of labour supply in Poland.

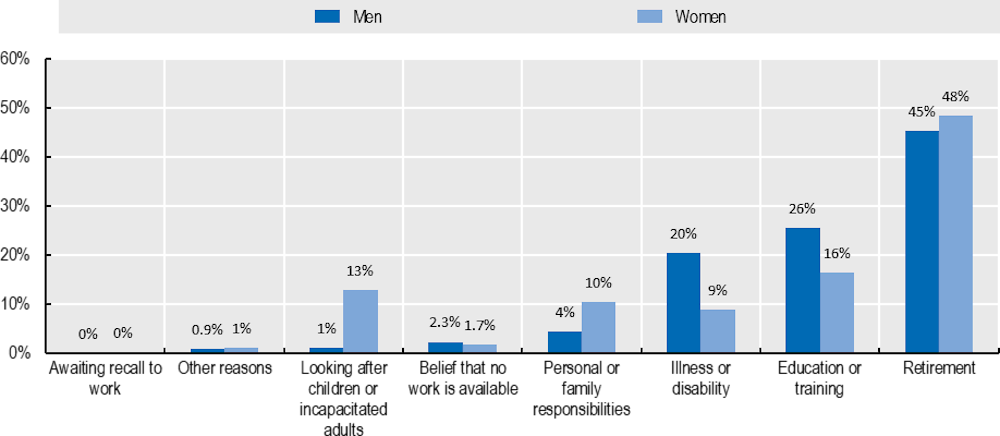

The reasons for economic inactivity differ between men and women. Women are more likely to remain economically inactive to take care of their families. Family responsibilities such as taking care of the household, looking after children, the chronically ill or older members of the family are more likely to fall on women than on men. 1 in 4 inactive women cites family duties as the reason behind their inactivity, while this is the case only for 1 in 20 inactive men. Working-age men, on the other hand, are mostly temporarily inactive due to participation in education and training. Illness and disabilities present other important reasons for men’s economic inactivity.

The “hidden unemployed” are those that can be reasonably expected to look for work. Hidden unemployment goes beyond the traditional definition of unemployment and also includes those who may be willing to work or have stopped looking for work for economic reasons (i.e. taking care of relatives due to the lack of access to care facilities; early retirement; and discouraged workers). Estimates show that the “hidden“ unemployment rate in Poland was 5.7 percent in 2019, 75 percent above the conventional unemployment rate of 3.3 percent.

In Poland, trends in economic inactivity over the past two decades have a strong regional dimension. These trends are tied to two main variables: convergence of those regions with historically high economic inactivity rates to the country-level average and regional differences in GDP per capita growth rates. These phenomena have to be understood in conjunction with Poland’s robust economic growth since its transition to a market economy. As labour demand increased, employers started tapping into idle labour resources.

Both market access and legacy costs due to high historical agricultural shares in total employment are likely to be driving forces behind differences in the extent to which trends in regional economic inactivity diverge. The ability of Polish regions to attract foreign capital strongly depends on their geography. While regions bordering Germany have managed to increase their foreign capital stock per capita by up to 400% following Poland’s accession to the EU, regions at Poland’s Eastern border have not managed to attract additional capital and are now characterised by large shares of relatively less productive SMEs. The same Eastern regions bore the brunt of Poland’s shift away from agricultural production towards the manufacturing and service industries.

COVID-19 is likely to compound megatrends in automation and skill polarisation, with regional differences. Past studies show that firms are likely to make labour-saving cost changes to their production processes. With automation mostly affecting employment in the medium-skill category, this process may exacerbate job polarisation, a process in which the relative shares of high and low-skill jobs grow, while the share of middle-skill jobs falls.

3.1. Introduction

A host of factors can drive economic inactivity, ranging from childcare to discouragement from job search. This chapter delves into the drivers of economic inactivity in Poland. Section 3.2 provides an overview of potential causes of economic inactivity across demographic groups. Section 3.3 explores regional level factors behind inactivity differences across Poland. Section 3.4, meanwhile, analyses economic inactivity in light of broader megatrends that accentuate labour market inequalities.

3.2. Drivers of economic inactivity in Poland

3.2.1. Inactivity is higher in Poland than in the rest of Europe for all groups

An inclusive labour market provides access and equal opportunities to all groups. However, in many OECD countries, labour market inequalities have been widening, with persistent difficulties to participate fully in the labour market for some groups and significant disparities in pay, working conditions and career prospects. Breaking down individual circumstances for inactivity can provide useful insights for policymakers to identify target groups for future local labour market activation strategies.

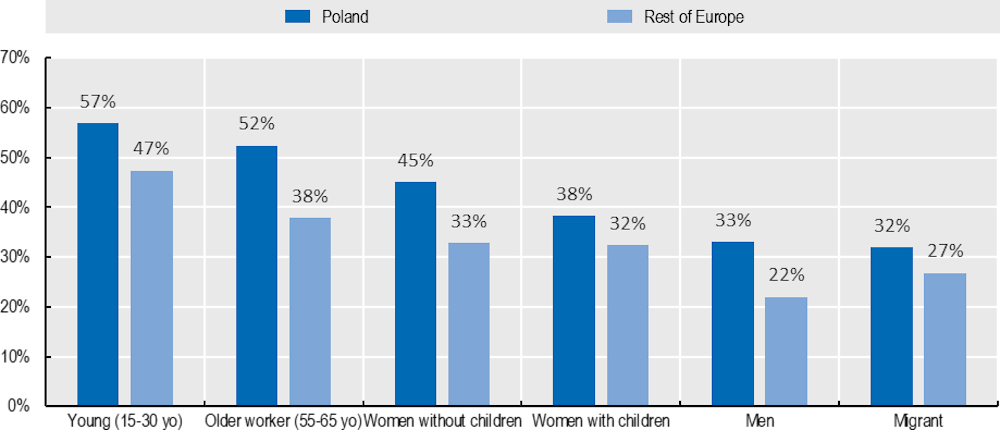

Compared to the average across other European countries, the economic inactivity rate is higher in Poland among youth who are not in education or training, older workers, women, men and migrants. The inactivity rate is highest among youth who do not currently pursue education or training. 57% of those aged 15 to 30 who do not currently pursue education or training are economically inactive, a rate 10 percentage points above the average across the rest of Europe. Older workers are the second group that is characterised by a high economic inactivity rate in Poland. One in two individuals aged 55 to 65 do not participate in the labour market, while this rate is much lower in other European countries (Figure 3.1).

Women, with or without children, are the third group with the highest inactivity rates. In addition to cultural reasons for low female participation, women face challenges to labour market participation, especially when they have young children. Interestingly, women without children participate even less in the labour force than women with children, while such a difference does not exist in other European countries. Both men and migrants in Poland have similar inactivity rates. In these groups, one in three do not participate in the labour market. While the inactivity rate of migrants is closer to the one observed in other European countries, men in Poland clearly participate less in the labour market compared to men in other European countries.

Figure 3.1. Inacitivity rate is higher across all groups of workers in Poland compared to the rest of Europe

Note: Inactivity rate is defined as the number of individuals who are inactive in the labour market over the working-age population. "Young" refers to individuals aged 15-30, excluding those in full-time education or training. "Women with children" refers to working-age mothers with at least one child aged 0-14 years. "Migrants" refers to all foreign-born people with no regards to nationality.

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS (2019).

3.2.2. Lower levels of skills are driving the high inactivity rates in Poland

Human capital is a crucial element in understanding the labour force participation differences within societies. Individuals with higher years of formal education have a higher probability of participating in the labour market, earning higher wages, and working longer in life. Being in education for longer helps people gain a wider range of skills that make them more adaptable and successful in a rapidly changing labour market. Across the OECD, the economic inactivity rate is 24 percentage points higher for people with low education levels (i.e. below upper secondary education) in comparison to those having attained tertiary education (Figure 3.2).

Labour market participation in Poland is highly uneven across populations with different skill levels. Nine out of ten individuals who have high levels of education are active in the labour market. In contrast, one in two individuals with low levels of education do not participate in the labour market. As observed in the numbers corresponding to the rest of the European countries, it is common that individuals with low education levels are less likely to participating in the active labour force than those with higher education levels. However, in the case of Poland, this gap is strikingly large for workers with lower levels of education, indicating that some factors are preventing them from taking part in the labour market.

Figure 3.2. Lower education groups are driving the weak labour force participation

Note: Inactivity rate is defined as the number of individuals who are inactive in the labour market over the population between 25-64. The low education corresponds to below upper secondary education, medium education corresponds to upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education, and high education refers to tertiary education.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD dataset: Educational attainment and labour-force status, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EAG_NEAC (accessed April 1, 2021).

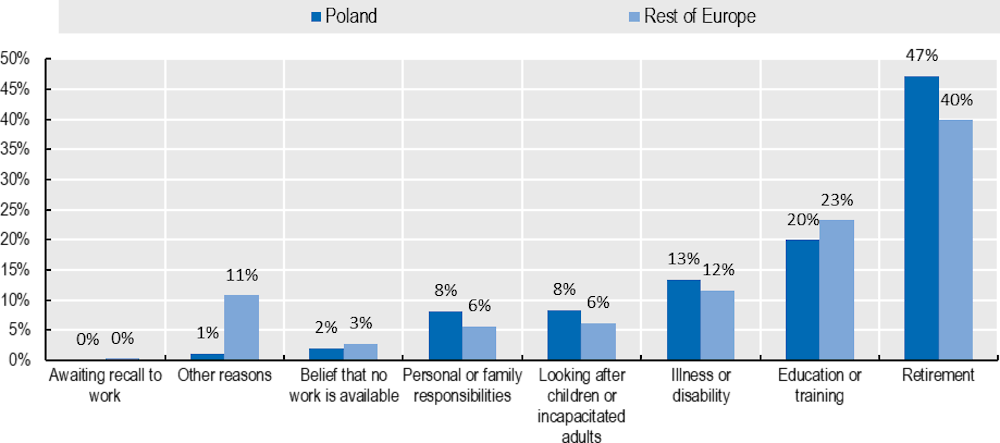

3.2.3. The reasons for economic inactivity

People can be economically inactive for a number of different reasons. These reasons can differ from place to place, but also from different demographic groups. Like in other European countries, students and retirees constitute the largest shares of working-age population economically inactive (Figure 3.3). It is reasonable to expect that students are well placed to enter the labour market they are qualifying for and that early retirees have most likely been able to leave the labour market because they are financially able to do so. Still, it is noteworthy that the share of retired individuals among Poland's inactive population is roughly 17% higher than the rest of Europe.

Reasons for inactivity differ significantly between men and women. Retirement is the main reason for inactivity for both genders and corresponds roughly half of those who are inactive (Figure 3.4). While education and training remain the second most important reason for both genders, it is a more important factor for men than women. For instance, while 1 in 4 men do not participate in the labour market due to participation in education and training, the share is only 1 in 6 for women. The difference between genders can be driven by many factors. For example, culturally, men might be competitive in the labour market, leading them to to invest in education for longer years, to achieve higher levels of degrees to unlock their access to higher positions. However, the difference might also be driven by women who do not participate in education as they do not expect to participate in the labour market.

Figure 3.3. Individual reason for inactivity

Note: The answers are ranked in ascending order depending on the share of each answer in Poland and other European countries.

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS (2019).

Figure 3.4. Individual reasons for inactivity by sex

Note: The answers are ranked in ascending order depending on the share of each answer in Poland and other European countries.

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS (2019).

Women are more likely to remain economically inactive to take care of their families. Family responsibilities such as taking care of the household, looking after the children, the chronically ill or older members of the family are more likely to fall on women than on men. In fact, 1 in 4 inactive women cites family duties as the reason behind their economic inactivity, while this is the case only for 1 in 20 inactive men. This difference highlights the importance of a cultural factor in the family roles where women bear the responsibility of family responsibility and stay home. The provision of free childcare and elderly care services remains an important policy response for reducing the share of women unable to participate in the labour market due to family care duties.

3.2.4. Part-time employment

Across the OECD, part-time work, including those workers who usually work less than 30 hours per week at their main or only job, has been increasing in recent decades. An increase in part-time work can be considered a positive development as it allows an increase in labour force participation of women or people with disabilities or allows a better work-life balance. Part-time employment can also be an issue if workers are forced to work part-time as they could not find a full-time job, or they would like to work more hours. Under such circumstances, involuntary part-time employment could be an indicator of low job quality.

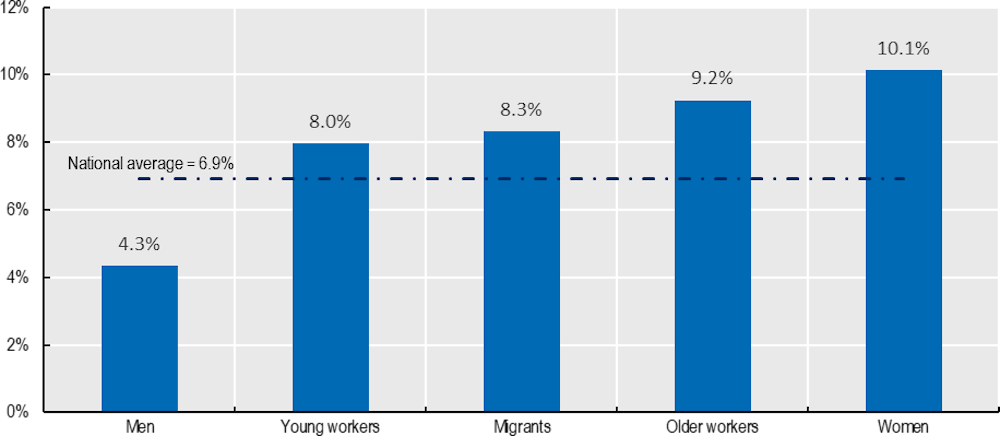

The share of part-time work has increased in Poland over the past decades, yet remains well below the rest of European countries. In 2019, around 7 percent of Poland's active workers worked part-time as an employee or self-employed, while the rate was 21.5 percent in rest of Europe. The prevalence of part-time varies significantly across different groups. For instance, while only 4 percent of male workers are employed part-time, the rate is more than double for all other groups (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5. Part-time employment is significantly more common for disadvantaged groups

Note: The number of part-time workers in total group employment. “Young workers” refers to individuals aged 15-29, excluding those in full-time education or training. “Migrants” refers to working-age individuals all foreign-born people with no regards to nationality. “Older workers” refers to individuals aged 55-64.

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS (2019).

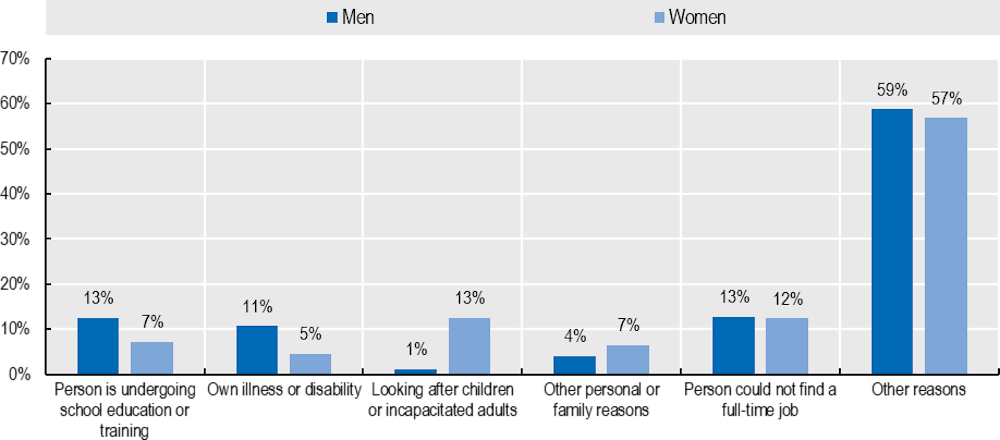

The share of part-time work is highest among women. In most OECD countries, women are more inclined to work part-time to balance family responsibilities. However, this part-time employment can be partially involuntary due to lack of childcare or healthcare facilities. In fact, among male workers in Poland, only 1 percent report working part-time due to reasons such as looking after children or incapacitated adults in the household, while this share stands at 13 percent among female workers (Figure 3.6). The large gap is likely driven by a set of complex factors, including social norms and gender roles in Poland, which puts the responsibility of caring for family members on women. However, a part of this gap could also be driven by a lack of access to care services that prevents women from contributing to the labour market with their full potential. Experience from other OECD countries further indicates that involuntary part-time work increases during economic downturns (OECD, 2019[1]). Thus, the less favourable labour market conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic could have increased involuntary part-time work, exacerbating involuntary part-time work among female workers.

Figure 3.6. Some women work part-time due to caring responsibilities

Note: Sample includes only individuals who work part-time and thus responded to the question.

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS(2019)

3.2.5. Accounting for “hidden” unemployment across Polish regions

Part of the inactive population could return to the labour market if the right conditions were provided and be a critical source of labour supply. Various factors could be leading individuals to inactivity. While some individuals are inactive by choice (e.g. to spend more time with their children) or due to their personal situation (e.g., severe disability limiting physical movement), others remain inactive as they believe there are no jobs available or they are forced to stay home to take care of family due to a lack of childcare or elderly care services. Identifying individuals who remain inactive due to their circumstances and would be willing to work if the necessary conditions were provided is crucial, as putting the right conditions in place could lead to significant economic gains.

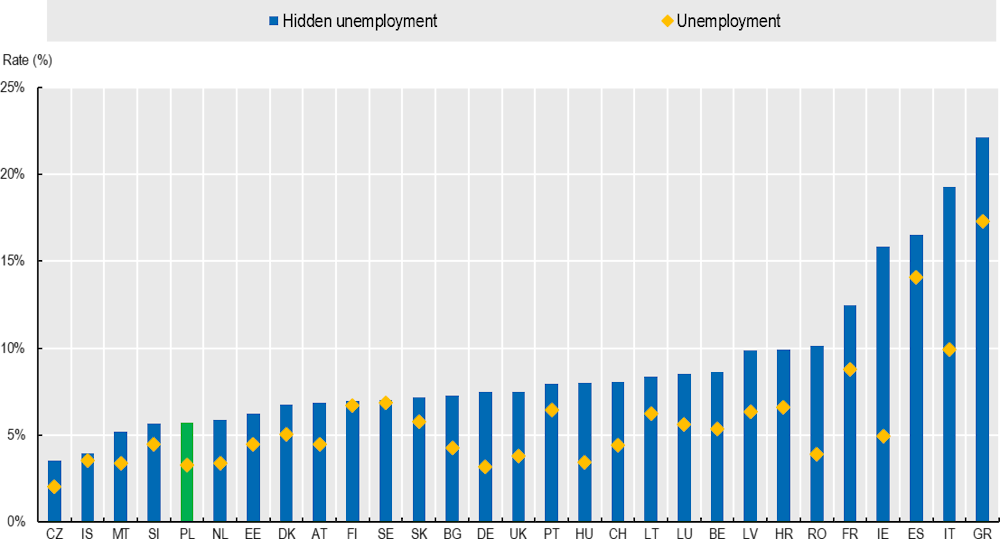

Factoring this group of people into an analysis of unemployment rates across OECD countries and regions reveals pockets of “hidden” unemployment. “Hidden” unemployment is not an official unemployment rate but serves as a useful concept to quantify the share of the economically inactive that could be activated. It thus provides a metric of the extent to which policy can reduce economic inactivity. A detailed description of how “hidden” unemployment is calculated is provided in Box 3.1.

Box 3.1. “Hidden” unemployment – an overview of the methodology applied

The analysis in this chapter proposes an estimate of “hidden” unemployment by accounting for individuals aged between 25 and 54 who may be willing to work or have stopped looking for work for non-economic reasons. It assumes that these individuals can return back to work if the right conditions are provided. The analysis applies the methodology developed in previous OECD work which considers the following groups as “hidden” unemployed (Barr, Magrini and Meghnagi, 2019[2]):

5 percent of individuals with health issues or disability;

Individuals who do not work as they have to take care of other family members (e.g., children or elderly) due to a lack of care facilities;

Individuals within the 25 to 54 age bracket who retire early;

Individuals who believe that there are no available jobs and are therefore discouraged from seeking employment.

Among people with health issues or disability, some individuals would be able to work if work arrangements such as flexible work hours or remote working were compatible with their health conditions. According to a recent OECD study, 5 percent of individuals with health issues or disability in Poland can work if the right conditions were provided (MacDonald, Prinz and Immervoll, 2021[3]).1 The analysis in this chapter applies this ratio when calculating the hidden unemployment numbers.

The denominator in this calculation differs from the traditional unemployment rate as it inlcudes those in the labour force but also those individuals who are inactive due to one of the abovementioned reasons.

“Hidden” unemployment is not an official unemployment rate and should not be confused with hidden unemployment in agriculture

There is no international definition of “hidden” unemployment. The “hidden” unemployment rate proposed here should thus be understood as providing governments with an idea of the economic potential among segments of the population that are not part of the labour force. The term hidden unemployment has also been applied in the context of family farming in the Polish agricultural sector. It sometimes refers to family members employed on very small, family-owned farms that are characterised by low productivity and where work efforts of additional emloyees are largely redundant (OECD, 2018[4]). The “hidden” unemployment rate calculated here should not be confused with the hidden unemployment in agriculture.

1. A comprehensive review of best practices to improve labour market participation of people with health issues and disability can be found in (OECD, 2010[23]).

In 2019, the share of the economically inactive who were willing to work (i.e., the “hidden” unemployment) was on average 11 percent across European countries, almost twice as high as the unemployment rate of 6 percent (Figure 3.7). The gap between the “hidden” unemployment and the traditional measure of unemployment varies across countries. In countries such as Germany, Hungary, Ireland or Romania, the unemployment rates adjusted for “hidden” unemployment is more than two times as high as the unemployment rate. In others such as Sweden or Finland, the gap is much smaller.

Figure 3.7. “Hidden” unemployment can be almost twice the standard unemployment

Note: The unemployment rate adjusted to account for “hidden” unemployment is computed as the number of people unemployed plus those who are inactive for who may be willing to work or have stopped looking for work for non-economic reasons (i.e., people with health issues or disability but who could work; people who take care of relatives due to lack of facilities; people who are early retirees; people who stopped looking for a job because they believe that no jobs are available; and people who do not work for other reasons) as an overall percentage of the labour force plus the inactive for economic reasons as described above. The denominator in this calculation differs from the traditional unemployment rate because it also includes those individuals who are inactive for economic reasons – not only those in the labour force. The sample is limited to those between the ages of 25 and 54. See Box 3.1 for further details.

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS (2019)

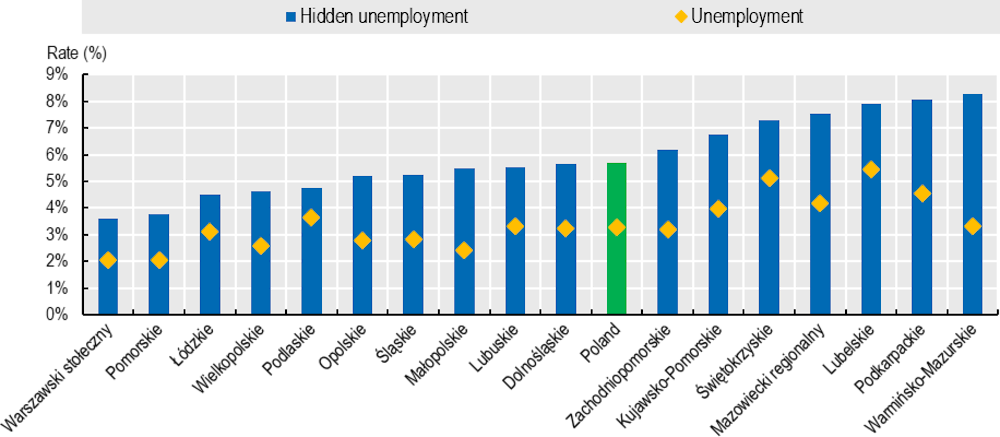

In Poland, taking into account “hidden” unemployment, such a rate would be 5.7 percent which was 75 percent above the standard unemployment rate of 3.3 percent. However, one can see fairly large variations in the difference between these two rates across Polish regions (Figure 3.8). The smallest difference is observed in Podlaskie, where the hidden unemployment rate is 30 percent higher than the unemployment rate. In contrast, in Lesser Poland or Warmian-Masuria, the hidden unemployment rate is more than twice the unemployment rate. While the gap is a consequence of a complex set of factors, it indicates a disadvantage in some Polish regions in utilising their employment potential. This suggests that while the Polish regions had relatively low unemployment rates, the rate could be much higher if people who are not in employment but could potentially work were to be accounted for. If Polish regions provided the right conditions, they could likely increase their labour supply and benefit from a potential that remains untapped for the time-being.

Figure 3.8. Polish regions are underutilising their potential labour supply

Note: The unemployment rate adjusted to account for “hidden” unemployment is computed as the number of people unemployed plus those who are inactive for who may be willing to work or have stopped looking for work for non-economic reasons (i.e., people with health issues or disability but who could work; people who take care of relatives due to lack of facilities; people who are early retirees; people who stopped looking for a job because they believe that no jobs are available; and people who do not work for other reasons) as an overall percentage of the labour force plus the inactive for economic reasons as described above. The denominator in this calculation differs from the traditional unemployment rate because it also includes those individuals who are inactive for economic reasons – not only those in the labour force. The sample is limited to those between the ages of 25 and 54. See Box 3.1 for further details. Regions displayed in Polish language, please refer to figure 1 for English translation.

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS (2019)

3.3. Regional labour markets experience different trends in economic inactivity

One of the striking features of the Polish economic inactivity rates is its decline over the past decade. Economic inactivity in Poland peaked at 37% in 2007 and then declined to 29.4% in 2019. However, this steady improvement on the national level masks region-specific trends that can be linked to local historical, economic and geographical characteristics. This section explores the regional dimension of economic inactivity in more detail. It illustrates the regional factors that shaped these trends using the examples of Lower Silesia and Podkarpacia.

3.3.1. Regional characteristics and the differences in economic inactivity across regions in Poland

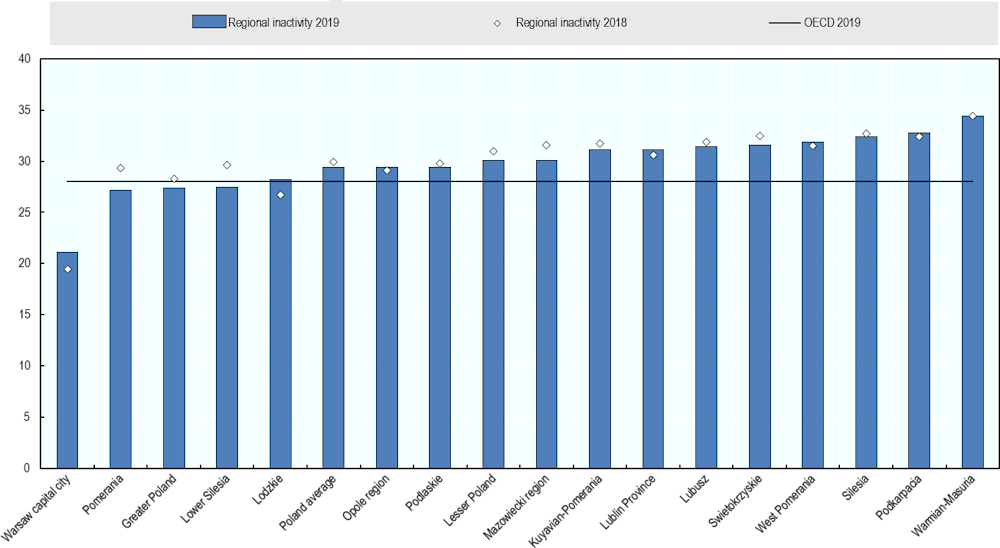

The share of the economically inactive population differs across Polish regions. In 2019, economic inactivity varied by over 13 percentage points between regions. In Warmian-Masuria, economic inactivity reached over 34%, while it was slightly above 21% in Warsaw. In 2019, economic inactivity fell below the OECD average in Pomerania, Greater Poland and Lower Silesia, while it remained above the average across all Polish regions.

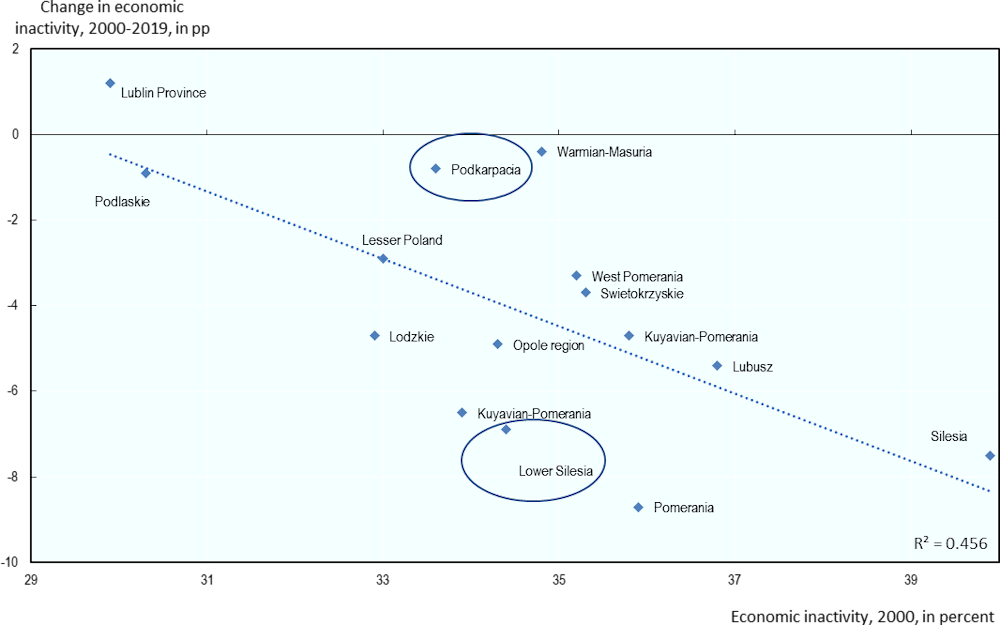

Regional economic inactivity rates converged over the past two decades in Poland. Regions with historically high economic inactivity rates saw their economic inactivity rates declining the most on average. Thus, on average, regions with historically high economic inactivity rates managed to tap into their economically inactive population relatively more, likely due to higher potential at the margin of the economically inactive when inactivity is high. Figure 3.9 shows that these convergence dynamics are able to explain almost half of the fall in economic inactivity across Poland when excluding the Warsaw capital city and the surrounding Mazowiecki region.

Figure 3.9. Economic inactivity rates converged across Polish regions over the past two decades

Note: The sample of TL2 regions excludes the Warsaw capital city and the Mazowiecki region for the lack of available historical data. Changes in economic inactivity rates calculated based on Participation Rate 15-64 (% labour force 15-64 over population 15-64).

Source: OECD Regional Database.

However, some regions outperformed and others fell below the expected convergence across regions. Lower Silesia outperformed compared to the trend and dropped to being one of the regions with the the lowest economic inactivity rates in Poland. Lower Silesia, where economic inactivity stood at 34.4% in 2000 managed to add 6.9% of its working age population to the labour force. On the other hand, Podkarpacia, where economic inactivity stood at 33.6% in 2000 still had an economic inactivity rate of 32.8% in 2019.

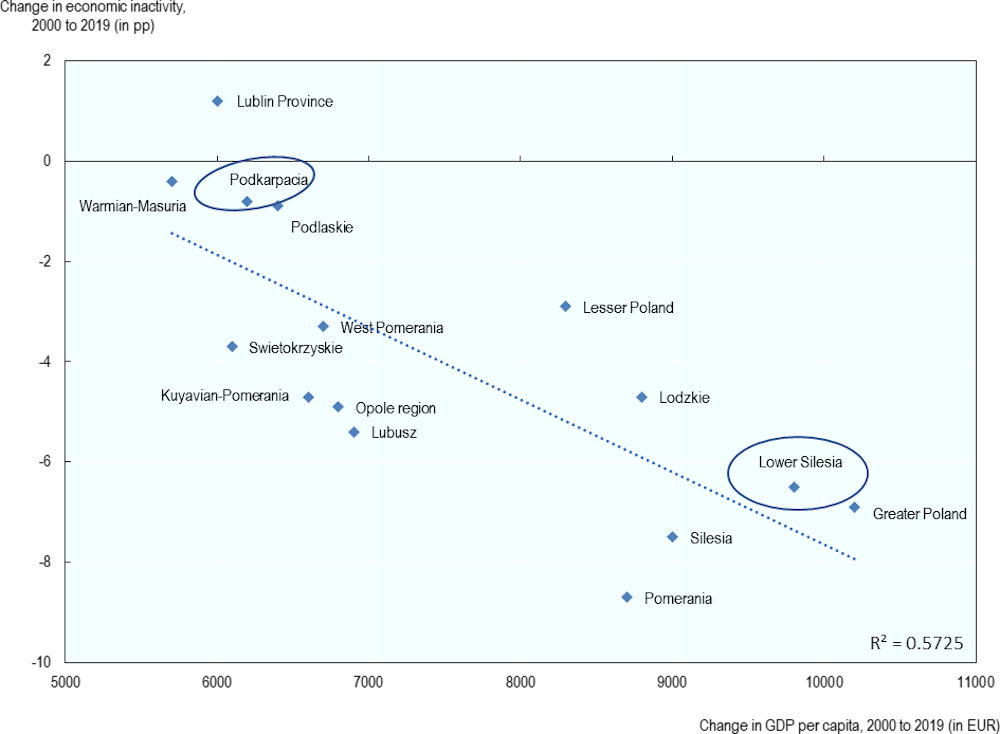

Trends in economic inactivity across Polish regions are closely tied to trends in regional GDP. All regions in Poland saw their per capita production rising sharply over the past two decades. Even in the least economically developed region of Poland, the Warmian-Masurian voivodeship, GDP per capita more than doubled from 2000 to 2019, rising from EUR 3 900 to EUR 9 500 at current market prices. However, other regions such as the Warsaw capital region where economic inactivity is the lowest in Poland, experienced a rise from EUR 10 600 to EUR 30 500 in GDP per capita at current market prices, exacerbating regional inequalities and providing a potential explanation for differing trends in economic inactivity across Polish regions. In fact, over the past two decades, changes in GDP per capita are strongly associated with differences in regional economic inactivity trends, even when excluding the Warsaw capital region as shown in Figure 3.10.

Figure 3.10. Trends in regional GDP per capita and changes in economic inactivity rates

Note: The sample of TL2 regions excludes the Warsaw capital city and the Mazowiecki region for the lack of available historical data. Changes in economic inactivity rates calculated based on Participation Rate 15-64 (% labour force 15-64 over population 15-64).

Source: Eurostat Regional Database (nama_10r_2gdp) and OECD Regional database.

Short-term trends in economic inactivity also vary across Polish regions. Between 2018 and 2019, two-thirds of regions saw the share of economically inactive people decrease, following the national average and generally continuing the long-term convergence dynamic (Figure 3.11). For example, in some regions with high economic inactivity, such as Silesia and Swietokrzyskie, the share of the economically inactive population decreased from 32.7% to 32.4% and from 32.5% to 31.6%, respectively. Conversely, in one-third of the regions, the share of the economically inactive population increased. In some regions, these short-term fluctuations oppose long-term positive trends. For example, in Warsaw capital city and Lodzkie, economic inactivity rose from 19.5% to 21.1% and from 26.7% to 28.2%, respectively, between 2018 and 2019.

Figure 3.11. Inactivity rates increased in a third of Polish regions between 2018 and 2019

Note: Inactivity rates calculated based on Participation Rate 15-64 (% labour force 15-64 over population 15-64).

Source: OECD Regional database.

In Poland, population-level regional differences may explain some of the short-term fluctuations in economic acitivity, but do not appear to be a large factor explaining long-term trends. In other OECD countries, higher regional economic inactivity has been tied to the greater presence of economically inactive groups such as retirees, students or stay-at-home parents (Barr, Magrini and Meghnagi, 2019[2]). In Poland, regions containing student centres include the Warsaw capital region, Kraków in Lesser Poland or Wrocław in Lower Silesia. Between 2018 and 2019 economic inactivity increased in Warsaw capital city and Lodzkie, home to major urban centres. Rises in the student population or other trends related to urban employment may help explain this short-term trend. However, Warsaw capital city, Kraków and Wrocław, contain smaller overall shares of economically inactive people relative to other Polish regions: 21.1%, 30.1% and 27.5%, respectively.

3.3.2. In the case study regions of Lower Silesia and Podkarpacia, the foreign investment and firm size may play a role in diverging economic inactivity rates

Geography and better access to the EU market provide possible explanations for the differing economic trajectories of Lower Silesia and Podkarpacia. Following Poland’s accession to the EU in 2004, both the Warsaw capital region and the Polish regions bordering the EU benefitted from relatively large increases in foreign capital investments (Ambroziak, 2019[5]). The foreign capital stock in regions bordering Germany increased by up to 400% per capita (in West Pomerania). Lower Silesia, a region bordering both Germany and the Czech Republic, with its student and economic hub of the Wroclaw metropolitan region, experienced a rise in its foreign capital stock of around 150%. Most of the foreign capital originated from Germany, but the region also attracted foreign capital from Italy, Switzerland and the USA. In total, 8.6% of Poland’s total foreign capital stock was invested in Lower Silesia in 2017. On the other hand, the per capita foreign capital stock remained virtually unchanged at very low levels in Podkarpacia, Podlaskie and the Lublin Province between 2005 and 2017, regions located at the external border of the EU (Ambroziak, 2019[5]).

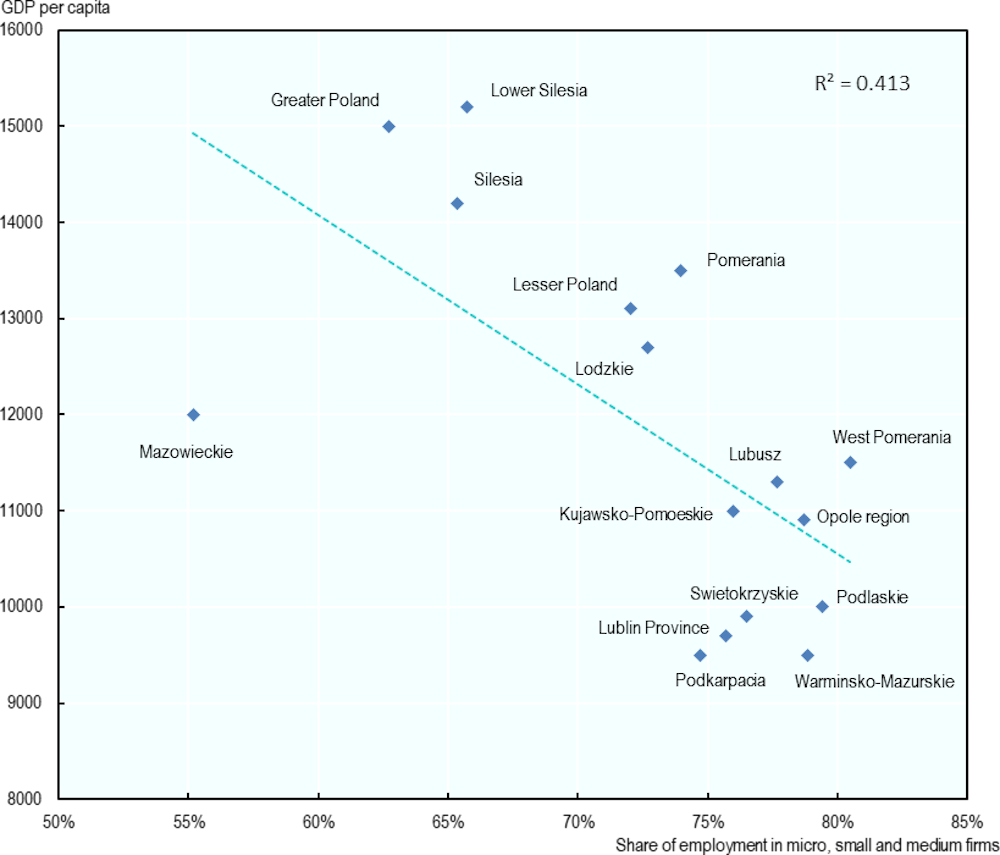

The lack of foreign investment in the East of Poland translates into the lack of large enterprises in these regions. Figure 3.12 shows that the share of local employment in SMEs in total employment is strongly associated with regional GDP per capita across Polish regions, which in turn is linked to economic inactivity. For example, in the regions of Lower Silesia, Silesia and Greater Poland, the share of employment in SMEs stood at 66%, 65% and 63% respectively. In Podkarpackie, Podlaskie and Lublin, the most Eastern regions of Poland, these shares stood at 76%, 79% and 75%.

Figure 3.12. SMEs and regional GDP

Note: The y-axis shows regional GDP per capita in EUR in 2019. The x-axis shows the regional share of employment in companies with 249 employees or less in 2019, thus following a simplified definition of SMEs based only on staff headcount.

Source: Eurostat (nama_10r_2gdp) and Statistics Poland (K25-G454-P2893)

Local level support to SMEs could therefore benefit lagging regions in particular. Technical assistance and mentoring to small businesses at the local level could build on existing local business centres and contact points for EU funds (OECD, 2020[6]). A pilot project to identify local strengths and weaknesses in attracting entrepreneurs with the objective to build “business services centres” in some medium-sized cities (Radom, Tarnów, Elbląg and Chełm) was completed in 2019 (Ministerstwo Rozwoju, 2019[7]). The main recommendations from the pilot include

better cooperation of cities with local universities and secondary schools to improve the local human capital base

work on the image of the city, its cultural offer and leisure activities to attract young workers;

incentivize local developers to build modern office space in collaboration with industries cities are trying to attract.

In addition, a broader strategy of internationalising SMEs could further boost employment and income opportunities in lagging regions. The high economic growth in Poland following its transition to a free market economy can partly be attributed to an increasing internationalisation of firms. However, Poland’s SMEs have not integrated into global value chains the same way as larger companies. One of the key reasons is the low productivity of SMEs in Poland compared to other OECD countries (OECD, 2020[6]). Boosting productivity of small companies in particular could therefore increase their capacity to export, which could improve local income opportunities and encourage labour force participation in lagging regions. Box 3.2 summarizes the key policy levers the OECD recommends in its 2020 OECD Economic Surveys on Poland.

Box 3.2. Key recommendations to support internationalising SMEs from the 2020 OECD Economic Survey

The recommendations to improve the productivity of SMEs in Poland to help their integration into global value chains centre on four key investments: within-firm training, easing red tape for SMEs, investing into transport and digital infrastructure in regions that host large numbers of SMEs and adapt innovation policies to smaller firms.

Enhancing life-long learning and workplace training are essential to make SMEs more competitive. Public support to training programmes can help SMEs cover parts of the relatively high costs they face when training their employees due to low retention rates. Highly skilled managers play a particularly vital role. Managers in SMEs could therefore benefit from the dissemination of high-performing organisational and management practices by the government.

The administrative costs for SMEs could be eased further. These costs relate to setting up new firms, streamlining court procedures, service regulations and tax compliance. For example, in 2019, Poland was the only country in the OECD where the time needed for tax compliance exceeded 300 hours per year (p. 79).

SMEs could also benefit from further public investment into their research and investment. This would not just increase their innovative output but also encourage SMEs to adapt state-of-the-art technology.

Finally, improving transport and digital infrastructure in lagging reasons that host relatively large numbers of SMEs would have a direct effect on decreasing trade costs from these regions.

Source: (OECD, 2020[6])

3.3.3. Large regional agricultural sectors are strongly associated with a lower decline in economic inactivity since 2000

The rapid decline of the large agricultural sector in Poland may still weigh on economic inactivity today. Employment in agriculture declined strongly all across Poland over the past three decades. Overall, the share of employment in the agricultural sector in overall employment declined from 22.6% in 1995 to 9.1% in 2019. In absolute terms, the agricultural sector lost around 1.8 million jobs. With employment in manufacturing only slightly increasing over time, new employment in the wake of high economic growth rates was mostly created in the service sector, which gained around 2.9 million jobs over the 1995 to 2019 period.

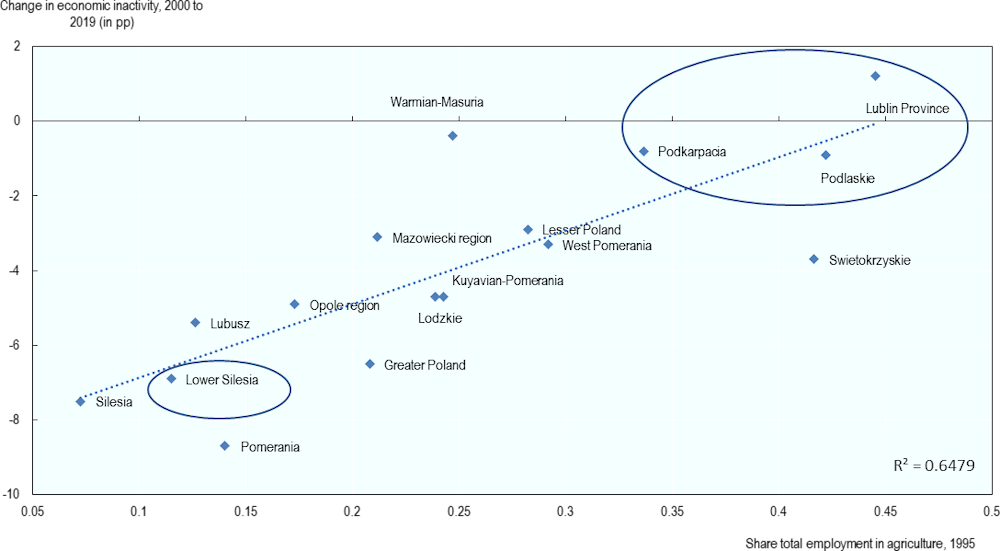

The Eastern regions of Poland bore the brunt of the decline in agricultural activity, providing an additional potential reason for their relatively unfavourable trends in economic inactivity. Apart from the geographical disadvantage, the historical economic sector composition in the Eastern parts of Poland may act as an additional obstacle to faster economic growth and may make these regions less attractive for foreign investment. Figure 3.13 shows the high correlation between the share of agricultural employment in total employment in 1995 and subsequent trends in economic inactivity from 2001 to 2019 for all Polish regions outside the Warsaw capital region. The voivodeships located at the Eastern border, Podkarpacia, Podlaskie and Lublin Province, as well as Swietokrzyskie. had large agricultural sectors, with 34%, 42%, 45% and 42% of the total employed workforce employed in agriculture in 1995. Their ineconomic inactivity rates showed no or very small improvements over the past two decades. On the other hand, regions such as Lower Silesia had a relatively less prominent agricultural sector (12% in total employment in 1995) and experienced a much faster decline in economic inactivity between 2000 and 2019.

Figure 3.13. The historical importance of the agricultural sector and regional trends in economic inactivity

Note: Share of total employment calculated as workers employed in agriculture as a share of total workers employmed. Warsaw capital region excluded due to lack of historical data availability. The change in economic inactivity for the Mazowiecki region pertains to the the 2010 to 2019 period due to the lack of earlier data.

Source: OECD calculation based on Statistics Poland (K4-G380-P2356) and OECD Regional Database.

Similar historical legacy costs have been found in other countries. For example, OECD research has found that local economic structure has also shaped the form and degree of economic inactivity across regions in the United Kingdom Box 3.3.

Box 3.3. Local economic history and economic inactivity

In the United Kingdom, economic inactivity is highest in former hubs for industrial manufacturing

Measuring the share of the economically inactive in cities, OECD research has found that those UK cities which used to house a large mining or manufacturing sector have a higher share of economically inactive people in the 50-64 age range. Mining, manufacturing or logistics represented over half of employment in 1951 in 25 of 32 cities with a higher than average rate of economic inactivity in the UK in 2017. These included cities such as Mansfield, Blackburn and Sunderland in northern England. Such cities also record higher shares of those with long-term illness, which may also contribute to higher rates of economic inactivity as many long-term sick become unable to work.

In these cities, many workers between 50 and 64 also record low levels of qualifications and skills. This could be linked to shortcomings in retraining policies, or a lack of attractive positions for those who used to work in heavy industry in the regions. Many of the cities with the highest shares of jobs at risk of automation also contain the highest shares of economic inactivity, compounding inequalities between regions.

Agricultural employment may exhibit further distortions that are difficult to capture in Labour Force Surveys. Some farm owners employ family members that add little to the productivity of the farm and could be more productively utilised elsewhere (OECD, 2018[4]). This underutilisation of labour is linked to economic inactivity in two ways. First, it may lead to an underestimation of economic inactivity if those employed on family farms report themselves as working in labour force surveys. Second, the lack of work contracts in within-family farm employment leads to similar issues around potential old-age poverty the economically inactive face.

The underutilisation of skills in agriculture persists across Polish regions (OECD, 2018[4]). However, the magnitude of the problem has declined due to the decline in total employment in agriculture. In the regions of Kuyavian-Pomerania, Lublin Province, Lesser Poland, Podkarpacia, Podlaskie and Swietokrzyskie, where the share of agriculture was high historically, the underutilization of labour in agriculture is likely to be strongest (KOŁODZIEJCZAK, 2020[8]).

Regional differences in the size of the informal economy in Poland are unlikely to explain geographical differences in economic inactivity rates. In Poland, around 3% of workers have no written contract at all according to Labour Force Statistics (OECD, 2020[6]). However, while the geographical concentration of informal work coincides with larger economic inactivity rates, these phenomena are unlikely to be linked causally. Rather, they are likely to have the common explanation of fewer attractive locally available income opportunities (see also Box 3.4). Thus, while stricter labour law enforcement remains important, such measures are unlikely to have large effects on regional labour force participation.

Box 3.4. Informal activity across Polish regions

Little research on the informal economy across Polish regions exists but scarce evidence based on the 2010-2014 Human Capital Balance (BKL) survey suggests that there is only limited overlap between the segments of the population engaging in informal work and the economically inactive within the working-age population. While the low- educated and youth are more likely to engage in informal employment, men are more likely to work informally than women across all age-cohorts. The informal economy further exists primarily in medium-sized towns rather than in rural areas (Beręsewicz and Nikulin, 2018[9]). This indicates that informal employment is a phenomenon that differs from the underutilisation of skills found in agricultural areas of Poland (OECD, 2018[4]).

Labour force status itself is a clear predictor of working informally. However, the economically inactive are only slightly more likely to engage in informal activity compared to the full-time employed. Part-time employment, unemployment and long-term unemployment, on the other hand, are strongly associated with individuals’ propensity to engage in informal economic activity (Beręsewicz and Nikulin, 2018[9]). This observation can provide a partial explanation for the persistent observed gap between the registered unemployment rate and the unemployment rate derived from Labour Force Surveys in Poland.

Similar to economic inactivity, informal economic activity is largest in the Eastern regions of Poland (Nikulin and Sobiechowska-Ziegert, 2018[10]; Beręsewicz and Nikulin, 2018[9]). A possible explanation lies in the lower GDP per capita in these regions. The level of regional economic development may reflect the relatively worse formal employment opportunities available, in terms of both income and quality of jobs. Thus, informal employment may be partly driven by the same underlying structural factors as economic inactivity, albeit not necessarily by the same population groups.

3.4. Regional implications of global labour market trends

3.4.1. The COVID-19 pandemic could accelerate automation, compunding risks for those economically inactive

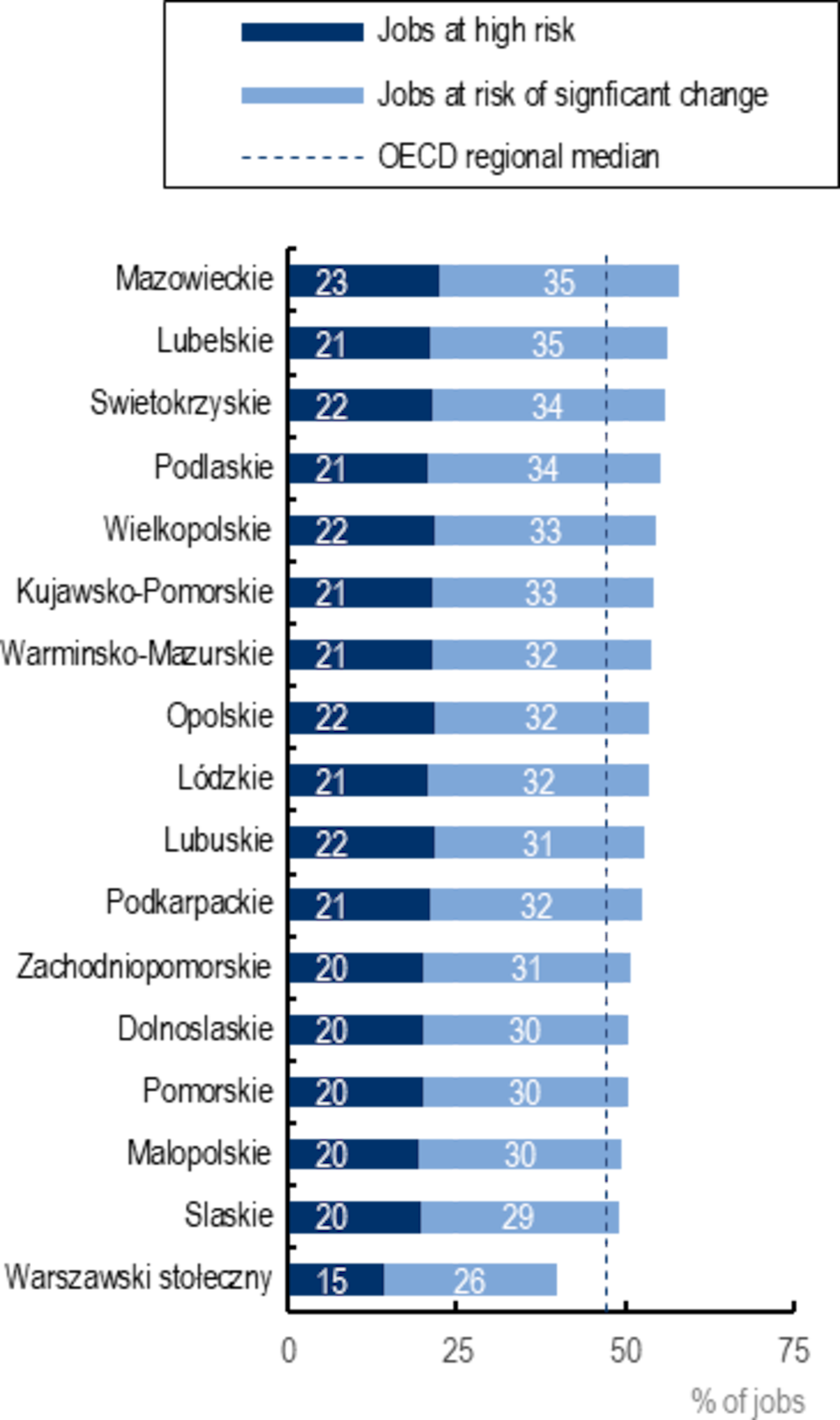

Regions across Poland face a relatively high risk of jobs changing or dissapearing due to automation compared to the average across OECD countries. In the median OECD region, the share of jobs at a high or significant risk of automation is 47.2% (Figure 3.14). According to the OECD, jobs at high risk of automation are like to dissapear completely as over 70% of tasks associated with the job may be replaced by technology, while those at significant risk have between 50% and 70% of their tasks vulnerable to replacement (Nedelkoska and Quintini, 2018[11]). In Poland, all regions but Warsaw capital city, where 40% of jobs are at some risk of automation, face a risk higher than 48%.

The COVID-19 pandemic could accelerate automation within firms. Early evidence suggests companies are digitalising and automating the way they produce and deliver services in response to social distancing requirements and tighter margins (Pissarides, 2020[12]). Evidence from the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis in the United States also shows those areas facing the steepest downturns in employment tended to see firms increase their capital stock and change their skill requirements away from routine occupations (Hershbein and Kahn, 2017[13]). This research posits firms make labour-saving cost changes to their production during crises in the face of tigther marings. Taken together, this process can contribute to “jobless” recoveries in which employment does not recover fully.

The risk of automation varies significantly across regions. In Mazowieckie, Lublin Province and Swietokrzyskie, the OECD estimates 58%, 56% and 56% of jobs to be at significant or high risk of automation respectively, the highest shares in the country (Figure 3.14). In Mazowieckie, 23% of jobs are at high risk of automation, the highest proportion in Poland. In Silesia, Lesser Poland and Pomerania, meanwhile, 49%, 50% and 50% of jobs respectively are at high or significant risk, the lowest shares in Poland after Warsaw capital city. Employment in these regions may be particularly susceptible to automation due to the presence of sectors containing vulnerable occupations, such as construction and manufacturing, major employers in the region. Especially in Swietokrzyskie and Mazowieckie, the share of regional GDP in industry and construction or industry exceeds the Polish national average (European Commission, 2021[14]).

In these regions, those workers who are displaced by changes may face economic inactivity when unemployed spells lengthen, weighing on their economic and social wellbeing. OECD research in the United States has shown that a large share of workers displaced by structural changes have remained economically inactive. In particular, a share of US workers who have been displaced due to import competition have suffered durable losses in income and struggle to find work (OECD, 2019[15]). Many of the specific skills they held for work in export industries may not be reconvertable in local labour markets, weighing on their capacity to find jobs of equivalent quality. In the same way, automation could supress or reshape jobs in Poland’s export-oriented industrial sectors as the effects of the pandemic persist, displacing workers with firm-specific skills durably. Here, an agreement between worker representatives, government and business representatives could ensure a fair and productive transition to a 4.0 industry. Poland can turn to international examples on how to lean on social dialogue to anticipate the effects of automation in industry (Box 3.5).

Figure 3.14. Outside the capital region, most Polish regions have a greather share of jobs at risk of automation than the OECD median region

Note: In Panel A “high risk” refers to the share of workers whose job faces a risk of automation of 70% or above. “Significant risk of change” reflects the share of workers whose job faces a risk of automation between 50% and 70%. In Panel B, high-skill occupations include jobs classified under the ISCO-88 major groups 1 (legislators, senior officials, and managers); 2 (professionals); and 3 (technicians and associate professionals). Middle-skill occupations include jobs classified under the ISCO-88 major groups 4 (clerks); 6 (skilled agricultural workers); 7 (craft and related trades workers); and 8 (plant and machine operators and assemblers). Low-skill occupations include jobs classified under the ISCO-88 major groups 5 (service workers and shop and market sales workers); and 9 (elementary occupations). Regions displayed in Polish language, please refer to figure 1 for English translation.

Source: OECD calculations based on Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012); and EU Labour Force Survey; Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), "Automation, skills use and training", https://doi.org/10.1787/2e2f4eea-en. Figure drawn from OECD (2020), Job Creation and Local Economic Development 2020: Rebuilding Better, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b02b2f39-en.

Box 3.5. In Spain, social dialogue is being used for fair automation

The risk of economic inactivity can be minimised when worker and firm representatives agree on fair transitions

In Spain, decentralisation has allowed for social dialogue to develop signifncatly at the level of regions. In 2019, in the Basque Country, Spain, the region’s social partners and the government relaunched the Mesa de Diálogo Social. The roundtable allows social partners to steer public policies and lay the bases for collective bargaining agreements through thematic work sessions. The work of the roundtable complements firm and sector-level collective bargaining. In 2019, the roundtable addressed public policies challenges such as :

Equality between men and women;

Employment;

Training;

Occupational health and safety;

Industry and;

Lifelong learning.

These discussion bore fruit. The Basque Country created new occupational health and safety observatories, and a renewed commitment from social partners and government to better inform students of Vocational Education and Training (VET) pathways.

The Pacto Social Vasco para una Transición justa a la Industria 4.0

One of the roundtable’s innovative initiatives is the Pacto Social Vasco para una Transición justa a la Industria 4.0, or the pact for a fair transition to a 4.0 industry. As manufacturing remains an important employer in the Basque Country, social partners have agreed the sector’s digitalisation should occur in a fair manner that protects workers and allows them to train for new production processes, or transition to new positions. This approach is especially relevant in the face of COVID-19, which risk increasing the use of labour-saving technology within companies as social distancing requirements endure. The Basque government will also contibute to the transition, putting in place training programmes to retrain workers to respond to skill needs identified by social partners. The region’s public employment service, Lanbide, meanwhile, will find employment for those who lose their jobs. In 2021 negotiations continued for the plan, though social partners are already adapting the plan to COVID-19. Social partners and the government are developing a plan for those sectors facing the sharpest crises to retrain and relocate employees.

Source: (OECD, 2020[16])

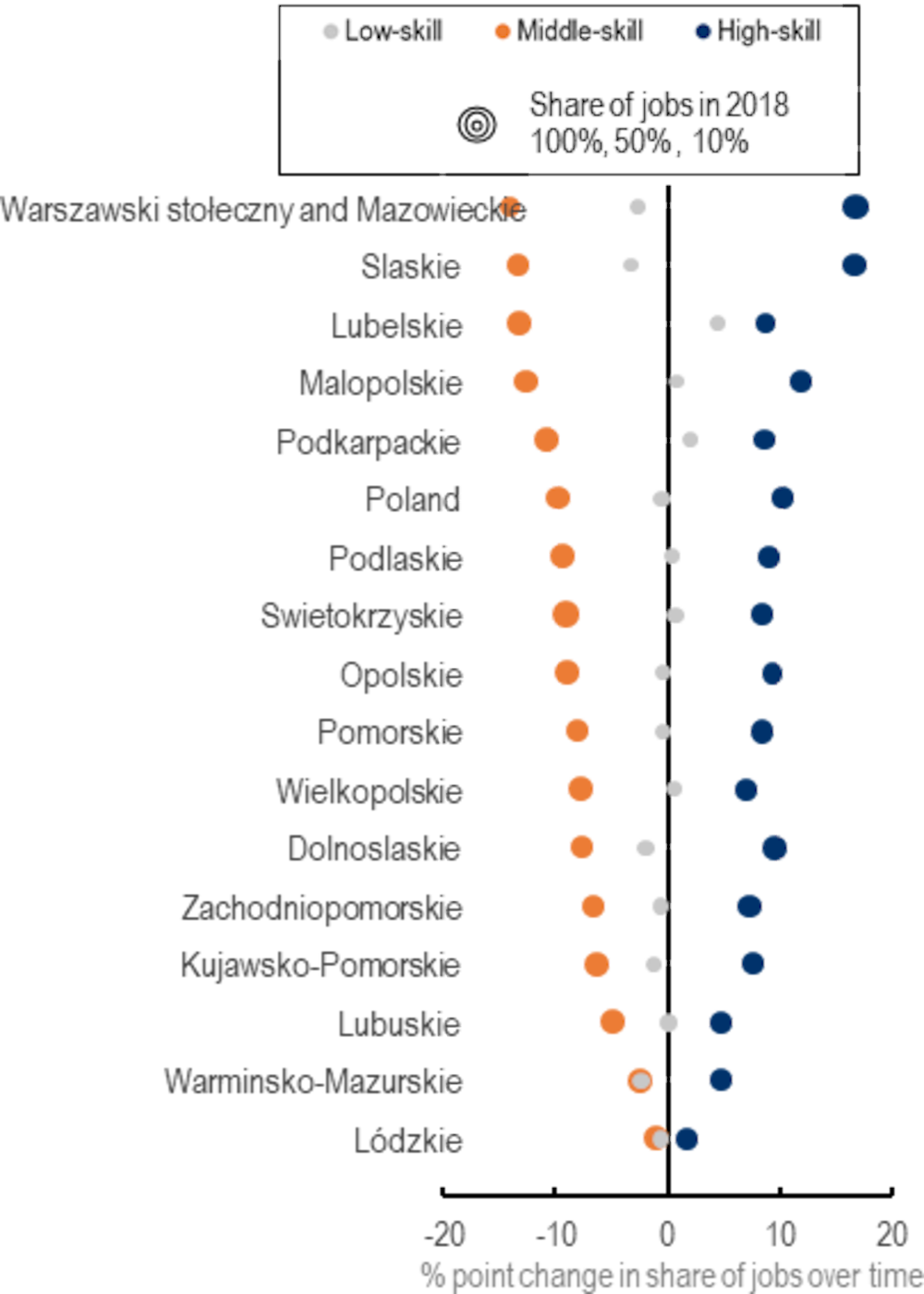

3.4.2. Economic inactivity exists in a polarising labour market in Poland

Since 2000, the Polish labour market has undergone job polarisation. Job polarisation is a process in which the relative shares of high and low-skill jobs grow, while those of middle-skill jobs fall. Job polarisation is a process of change in the occupational structure of an economy. In Poland between 2000 and 2018, the relative share of middle-skills jobs has decreased by 9.8 percentage points, that of high-skill jobs has increased by 10.3 percentage points and that of low-skill jobs has decreased by 0.5 percentage points (Figure 3.15). In total, Poland gained 262 400 low-skills jobs, shed 666 000 middle-skill jobs and gained 2 213 700 high-skill jobs. This a sign the economy is upskilling its jobs. The quality of jobs, however, may not be keeping pace with upskilling as the incidence of non-standard work contracts increased in Poland over this period (Lewandowski, Góra and Lis, 2017[17]).

Job polarisation also shapes economic inactivity by determining labour demand. After the 2008 financial crisis, research has shown that job polarisation, by decreasing the demand for middle-skill occupations in Europe, weighing on the labour market participation of men with lower levels of education (Verdugo and Allègre, 2017[18]). The same research suggests polarisation accelerated following the great recession across Europe. There is a risk of durable labour market exclusion for those with lower levels of education as the occupational structure of the Polish labour market evolves after COVID-19. As the pandemic reshapes demand for Polish exports durably, many workers in trade-related sectors may see their jobs supressed or automated. Although a large-scale wage subsidy policy is maintaining jobs and incomes throughout Poland since 2020, these will likely be lifted progressively across sectors as firms face a redefined demand for their products. Those workers will require social and educational assitance to ensure the pandemic does not discourage and exclude them from participating on the labour market.

Job polarisation in Poland has also unfolded differently across regions. The polarisation pattern has been most noted in the Warsaw capital region, Mazowieckie and Silesia, where middle-skill jobs have decreased by relative shares of 14.1 and 13.3 percentage points, representing a decrease of 162 500 and an increase of 26300 jobs respectively (Figure 3.15). In these regions, the share of low-skill jobs have also decreased by 2.7 and 3.3 percentage points respectively, but low-skill jobs increased in absolute numbers by 9000 and 47300 jobs respectively. Contrary to this pattern, regions such as Lublin Province and Podkarpacia have seen their shares of low-skill jobs increase by 4.5 and 2.1 percentage points respectively. Although predictions remain speculative as the COVID-19 pandemic continues, it is possible those regions that have faced steeper levels of middle and low-skill jobs loss may see lower skill workers at higher risk of falling into economic inactivity as the crisis may accelerate the polarisation pattern.

Polish voivodeships track changes in labour demand within their annual Occupational Barometer. An expert panel gets together annually to fill in questionnaires that asks questions on occupation-specific labour demand. The surveys are then used to forecast within-occuption labour demand. Local labour offices also utilize the survey data to design appropriate training for the unemployed. An alternative approach to the Occupational Barometer is the more skill-oriented “Abilitic2Perform” method applied in Wallonia, Belgium (see Box 3.6).

Figure 3.15. Labour markets are polarising differently across Poland

Note: Regions displayed in Polish language, please refer to figure 1 for English translation.

Source: OECD (2020), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work, https://doi.org/10.1787/9ee00155-en. Figure drawn from OECD (2020), Job Creation and Local Economic Development 2020: Rebuilding Better, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b02b2f39-en.

Box 3.6. Regional skills mapping in Wallonia, Belgium

By mobilising big data and expert groups, the public employment service of Wallonia tracks occupational change

Every year, the Public Employment Service (PES) of Wallonia, Le Forem, analyses skill demand in different sectors. Le Forem’s yearly analyses feed into training offerings for Wallonia’s business clusters. PES staff and industry-specific experts work on different steps of the analysis:

(1) PES staff create occupational reports for each sector using data from the PES;

(2) Sector-specific expert groups, composed of PES staff and outside experts, receive the report;

(3) The groups use a methor known as Abilitic2Perform to idenfity skills required for each occupation and skills group. The groups identify how each sector may evolve;

(4) Expert groups agree on the most likely scenario, and identify how skills needs may evolve;

(5) Training departments receive the results and design training programmes taking into account the results of the analysis.

Industries gain from this process as they can better quantify their skills needs, while job seekers and PES staff can gain better understanding of labour market demand.

In 2020, Le Forem published Métiers en tension de recrutement en Wallonie, identifying three major reasons for labour market gaps:

Candidate profiles do not correspond to the need of a firm, such as qualification, skills, mobility or languages;

Working conditions, whether perceived or real, do not incite job seekers to apply to a job or accept an offer, including due to contract type, wages, hours or physical/mental charge;

Insufficient candidates, as the demand for certain jobs may surpass the number of job seekers available.

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to reshape labour market demand durably. As Job Retention (JR) schemes are eased across OECD countries, this will carry new groups of unemployed looking for work. Skills mapping exercises, particularly those that pair big data use with interviews with industry experts, can help track the way skills demand evolves. Anticipating these changes can ensure that those who face job loss are supported, and that trainining opportunities can orient them into growing occupations.

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2020[16]), originally (Le Forem, 2020[19]).

3.4.3. Regional economic inactivity effects of the green transition

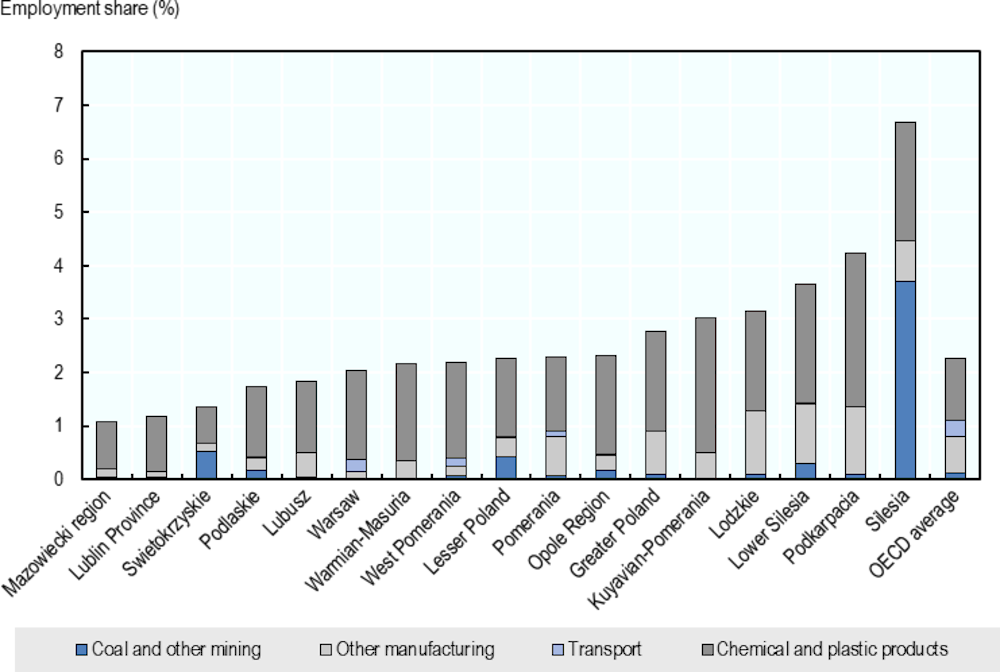

Poland, like other OECD countries, will experience both employment gains and losses due to the transition to net zero greenhouse gas emissions. To become a net-zero emissions economy by 2050, the primary EU target year as envisioned by the Paris agreement, Poland will have to transform its energy system gradually. Jobs will be at risk in industries such as coal and other mining, manufacturing, transport and chemical and plastic production.

Some regions in Poland face a relatively higher risk of job loss due to the net-zero transition. Figure 3.16 shows the employment share in industries at risk in Polish TL-2 regions compared to the OECD average. Most Polish regions only face moderate risks of employment loss. For all regions but Silesia, the share of employment in industries at risk of job loss is below 4.6%, around the OECD average. However, in Silesia, due to its heavy dependence on mining of coal and lignite, the share of employment in sectors at risk stands at 6.7% (Figure 3.16).

Figure 3.16. Employment in industries at risk due to the net-zero transition

Note: The y-axis shows the employment share in industries put at risk until 2040. For details on the methodology, see OECD Regional Outlook 2021 (OECD, 2021, p. 106[20])

Source: (OECD, 2021, p. 5[21])

Place-based policies can help regions such as Silesia to manage the transition to mitigate the risk of employment loss resulting in longer lasting economic inactivity. To avoid a rise in economic inactivity, regions facing job losses due to the net-zero transition can help smoothing that transition through smart local active labour market policies that target those who are likely at risk of job loss. An example of such a policy developed in the Belgian region Flanders is presented in Box 3.7.

Box 3.7. Regional policies to avoid an increase in economic inactivity due to the net-zero transition – an example from Flanders, Belgium

Active labour market policies offered by VDAB, the regional public employment service of Flanders, have started to focus on the green transition by integrating “green skills” into their training programmes. For instance, in the construction sector, programmes have begun integrating sustainable building and energy efficiency methods. VDAB has also developed a building centre to co-ordinate with actors in the building sector and develop training curricula with local partners.

A key feature of VDAB’s approach to the transition of the economy towards green jobs is the devolution of some services to regional employment offices, providing them with flexibility to deliver active labour market policies. District offices can involve local labour market actors and develop strategies based on local realities. The involvement of local actors makes it easier to anticipate risks to specific industries and develop strategies with local companies and unions to ensure processes and workers adopt accordingly.

These partnerships do not take place in isolation but complement VDAB’s Flanders-wide programmes.

Source: (OECD, 2021, pp. 202-203[20])

There will also be employment gains due to the net-zero transition but their geography is less certain. The largest employment gains are likely to occur in renewable power production and the recycling of material. Other gains are likely to come from electric vehicle production and the service sector (OECD, 2021[20]). Since the renewable energy sector is relatively more employment-intensive than the fossil fuel industry, there may be net gains from the transition (European Commission, 2018[22]). However, it is unclear where these gains will occur geographically (OECD, 2021[20]).

“Green skills” could be integrated into Poland’s Occupational Barometer surveys. Poland currently lacks a long-term labour market demand forecast. Such long-term forecasting could be integrated into the existing Occupational Barometer surveys. The on-going matching of the Polish Classification of Occupations and Specialisations to the European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations Taxonomy (ESCO) and the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08) will ensure international comparability of these forecasts.

References

[5] Ambroziak, A. (2019), “Foreign Capital Originating from the EU in Investment and Trade Activities of Polish Regions”, Studia Europejskie -Studies in European Affairs, Vol. 23/4, pp. 109-124, http://dx.doi.org/10.33067/se.4.2019.7.

[2] Barr, J., E. Magrini and M. Meghnagi (2019), Trends in economic inactivity across the OECD: the importrance of the local dimension and a spotlight on the United Kingdom, OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, https://doi.org/10.1787/20794797.

[9] Beręsewicz, M. and D. Nikulin (2018), “Informal employment in Poland: an empirical spatial analysis”, Spatial Economic Analysis, Vol. 13/3, pp. 338-355, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17421772.2018.1438648.

[14] European Commission (2021), Regional Innovation Monitor Plus, Swietokrzyskie and Mazowieckie, https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/regional-innovation-monitor/base-profile/swietokrzyskie.

[22] European Commission (2018), A Clean Planet for all - A European strategic long-term vision for a prosperous, modern, competitive and climate neutral economy, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0773&from=EN (accessed on 17 June 2021).

[13] Hershbein, B. and L. Kahn (2017), Do recessions accelerate routine-biased technological change? Evidence from vacancy postings, Working Paper 22762, https://www.nber.org/papers/w22762.pdf.

[8] KOŁODZIEJCZAK, W. (2020), “HIDDEN UNEMPLOYMENT IN POLISH AGRICULTURE IN 2005-2018-A SIMULATION OF THE SCALE OF THE PROBLEM”, Roczniki (Annals), Vol. 2020/1, http://dx.doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0013.7909.

[19] Le Forem (2020), Métiers en tension de recrutement en Wallonie, https://www.leforem.be/MungoBlobs/1391501709248/202006_Analyse_metiers_tension_recrutement_wallonie_2020.pdf.

[17] Lewandowski, P., M. Góra and M. Lis (2017), Temporary Employment Boom in Poland: A Job Quality vs. Quantity Trade-off?, Discussion Paper Series IZA DP No. 11012, http://ftp.iza.org/dp11012.pdf.

[3] MacDonald, D., C. Prinz and H. Immervoll (2021), “Can disability benefits promote (re)employment?”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers.

[7] Ministerstwo Rozwoju, P. (2019), Podsumowanie pilotażowego projektu “Centra usług biznesowych w miastach średnich”.

[11] Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), Automation, skills use and training, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/2e2f4eea-en.

[10] Nikulin, D. and A. Sobiechowska-Ziegert (2018), “Informal work in Poland – a regional approach”, Papers in Regional Science, Vol. 97/4, pp. 1227-1246, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12306.

[20] OECD (2021), OECD Regional Outlook 2021: Addressing COVID-19 and Moving to Net Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/17017efe-en.

[21] OECD (2021), Regional Outlook 2021 - Country notes - Poland - Progress in the net zero transition.

[6] OECD (2020), OECD Economic Surveys: Poland 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/0e32d909-en.

[16] OECD (2020), Preparing the Basque Country, Spain for the Future of Work, OECD Reviews on Local Job Creation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/86616269-en.

[15] OECD (2019), OECD Economic Survey of the United States: Key Research Findings, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264310278-en.

[1] OECD (2019), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/oecd-employment-outlook_19991266.

[4] OECD (2018), OECD Rural Policy Reviews.

[23] OECD (2010), Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers: A Synthesis of Findings, OECD Publishing, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264088856-en.

[12] Pissarides, C. (2020), As COVID-19 accelerates automation, how do we stop the drift into long-term unemployment?, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2020/07/21/as-covid-19-accelerates-automation-how-do-we-stop-the-drift-into-long-term-unemployment/.

[18] Verdugo, G. and G. Allègre (2017), Labour Force Participation and Job Polarization: Evidence from Europe during the Great Recession, https://www.ofce.sciences-po.fr/pdf-semofce/Labor-Force-Participation-and-Job-Polarization.pdf.