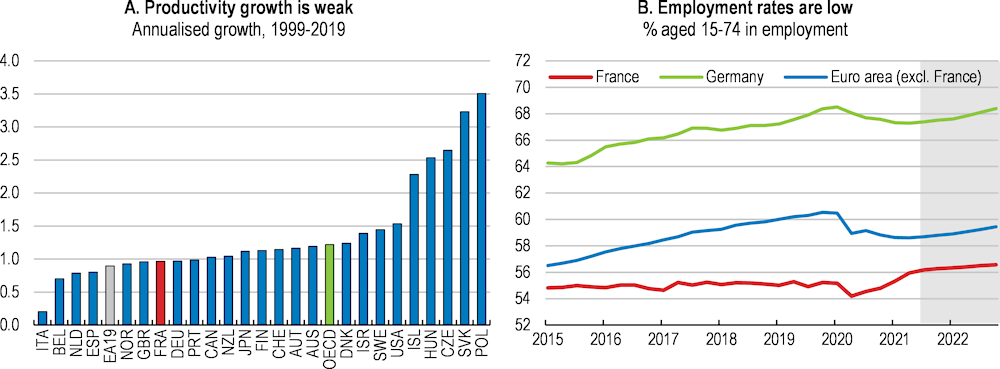

The French economy has bounced back following an unprecedented contraction during the COVID-19 pandemic. The fall in activity in 2020 was the sharpest since the end of the Second World War. As in other OECD countries, successive waves of COVID-19 cases reduced life expectancy by around half a year in 2020 (close to the OECD average; Figure 1.1). Economic activity and employment have bounced back swiftly since May 2021. Yet, the recovery remains conditional on the full normalisation of the health situation and an effective shift to more inclusive and sustainable growth once the remaining health restrictions are lifted.

OECD Economic Surveys: France 2021

1. Key policy insights

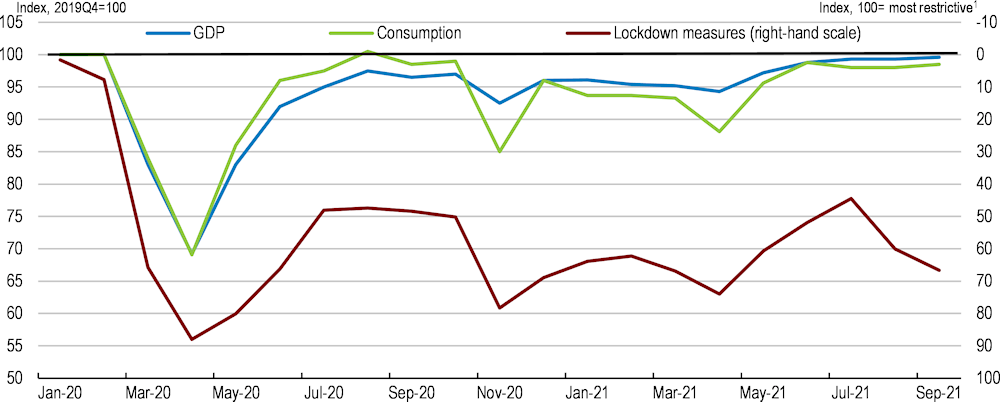

Figure 1.1. The pandemic caused a deep economic and social recession

1. EA4 is the simple average for Germany, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands.

2. Excess mortality compared to the weekly average for 2015-2019, as a proportion of the population.

3. The Oxford Index (COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, stringency index) is based on nine indicators, including closures of schools and workplaces, and travel restrictions.

Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections, and Mortality: Excess deaths by week, 2020 and 2021 (databases); Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford; ECDC (2021), Epidemic Intelligence, national weekly data.

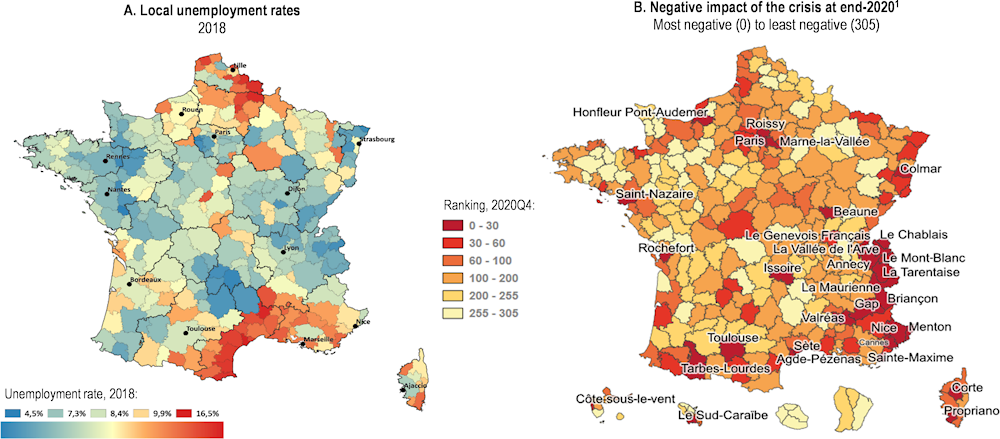

Despite effective emergency economic and social measures, the pandemic has weighed on the most vulnerable. Together with automatic budget stabilisers, the emergency measures allowed for relatively stable per capita disposable income and a minor fall in employment in 2020. However, older people, those born abroad and those living in the poorest, most densely populated municipalities were most affected by the first wave of the virus in 2020 (Insee, 2020a; Dubost et al., 2020). In early 2021, income losses were perceived as more frequent among the most vulnerable: low-income households, young people and the self-employed (Clerc et al., 2021). The number of minimum income recipients had increased sharply in the second part of 2020 and, despite a marked decline thereafter, it remained 2.8% above its 2019 level in July 2021 (Drees, 2021).

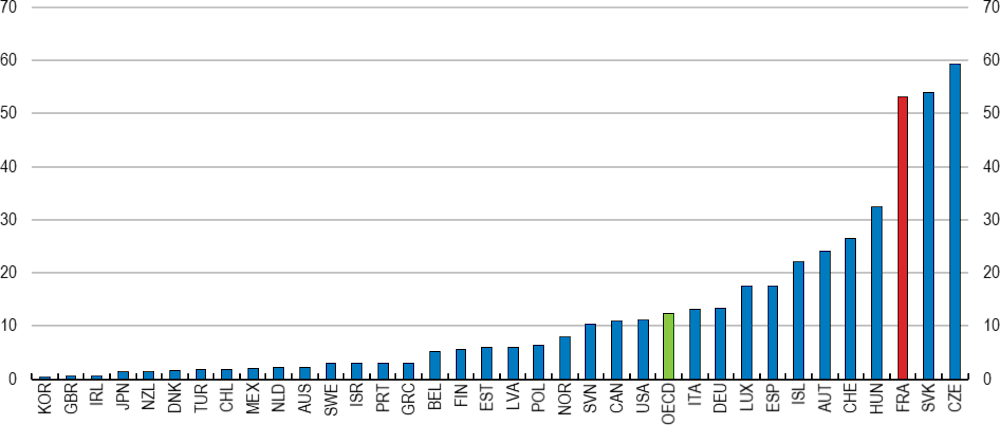

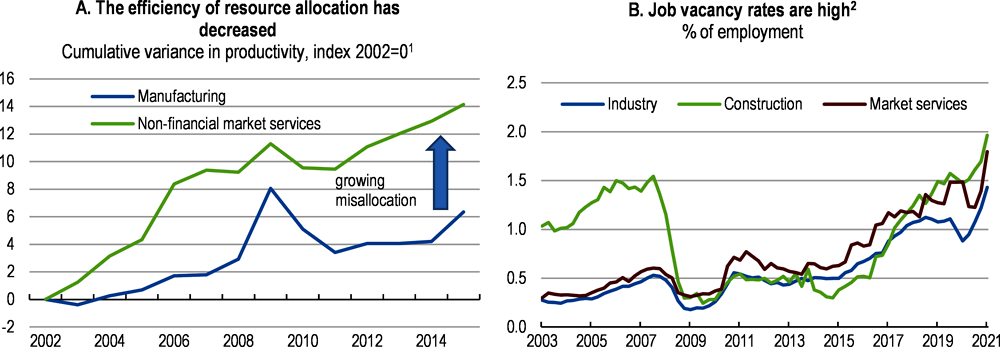

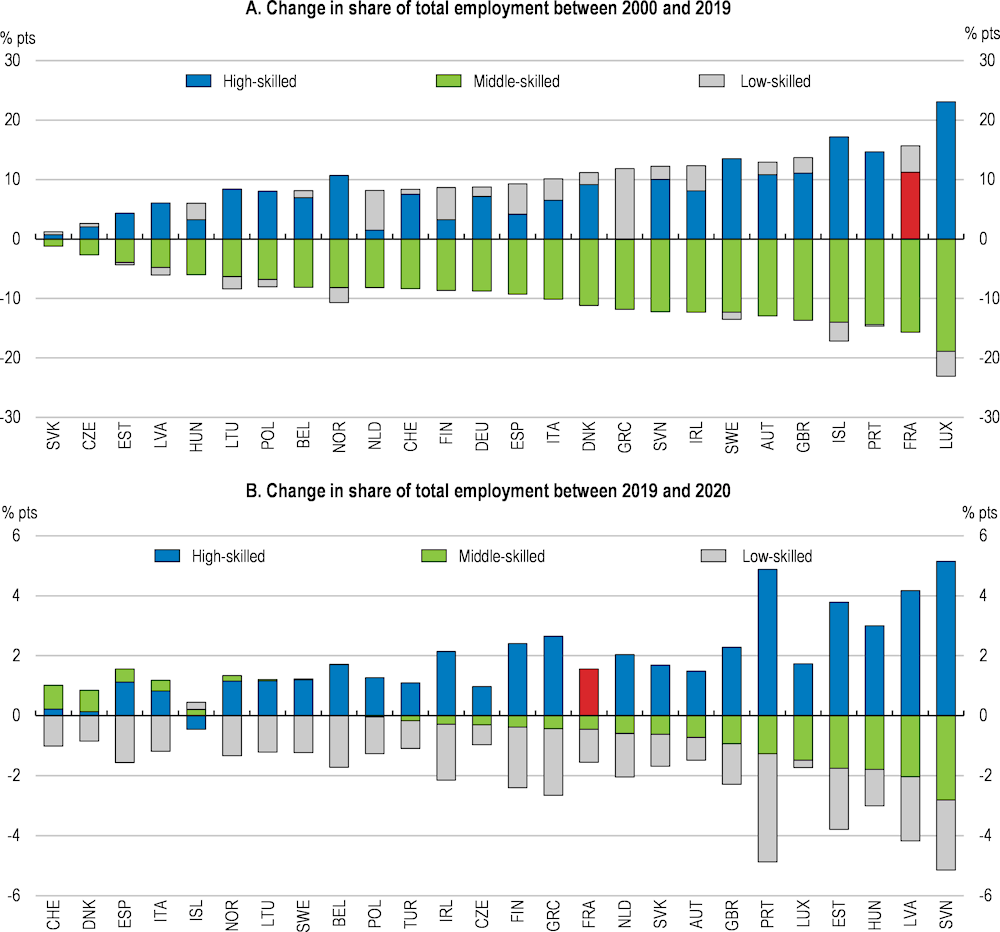

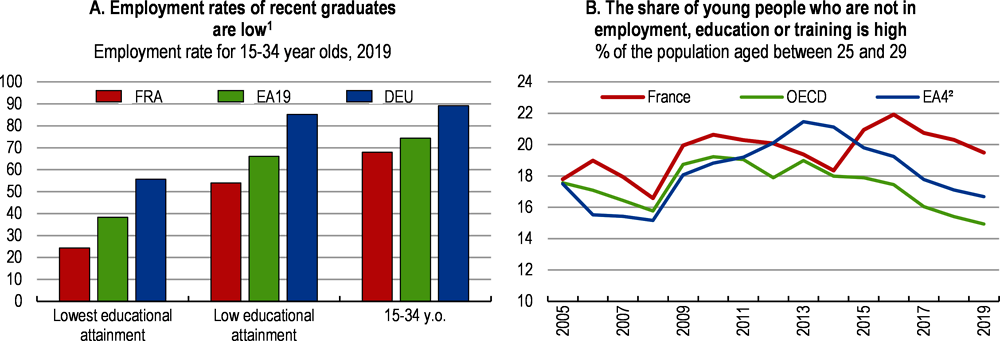

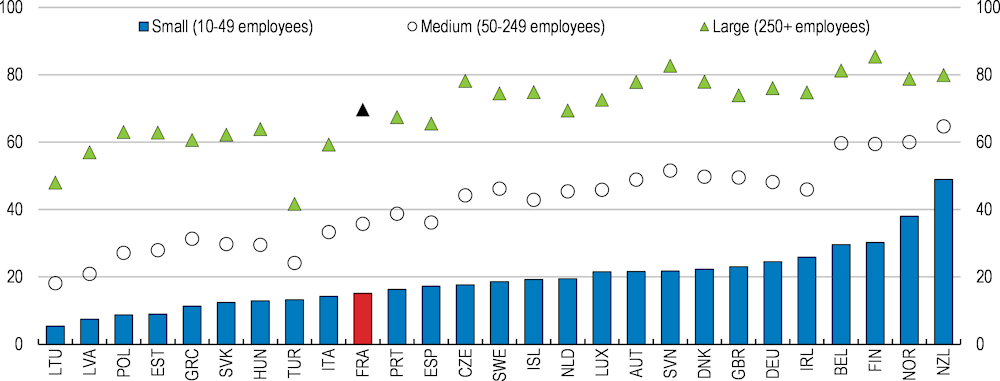

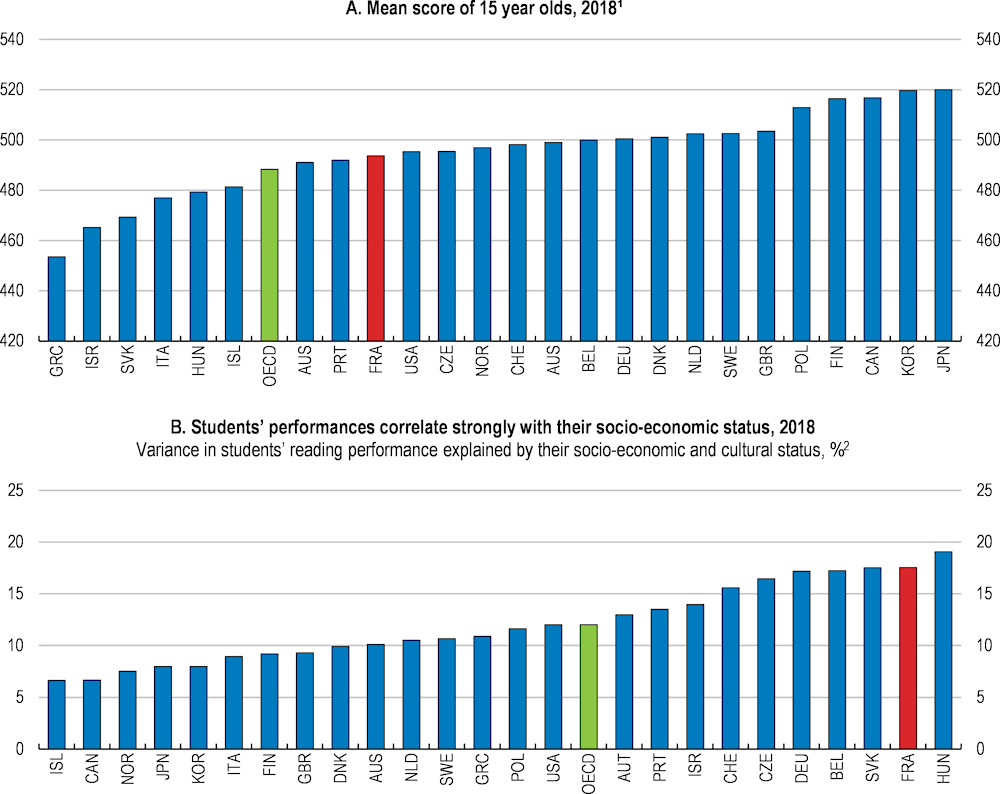

Before the crisis, the medium-term economic performance had been disappointing. As in most other advanced economies, growth in living standards as measured by per capita GDP had been constrained by the slowdown in productivity gains, while employment rates were still relatively low (Figure 1.2). Despite the rise in real wages, households’ purchasing power per unit of consumption, a better way of measuring the standard of living, had been stagnant for around 10 years (Insee, 2021a). Too many low-skilled workers and young people were excluded from the labour market, and unequal opportunities weakened cross-generational social mobility (OECD, 2019a).

Figure 1.2. Improving employment and productivity are long-term challenges

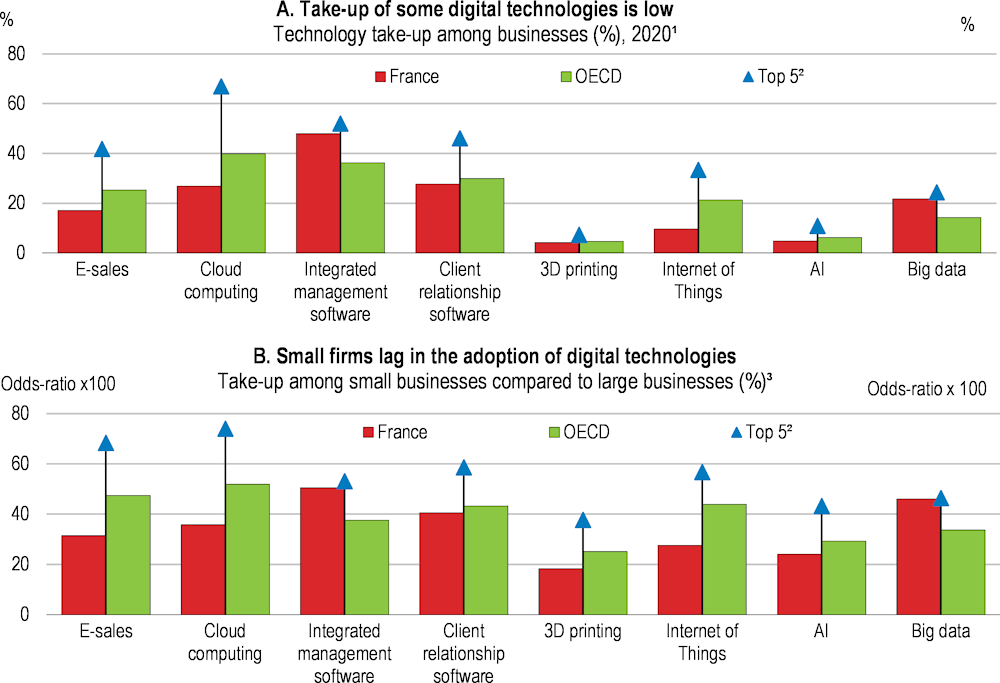

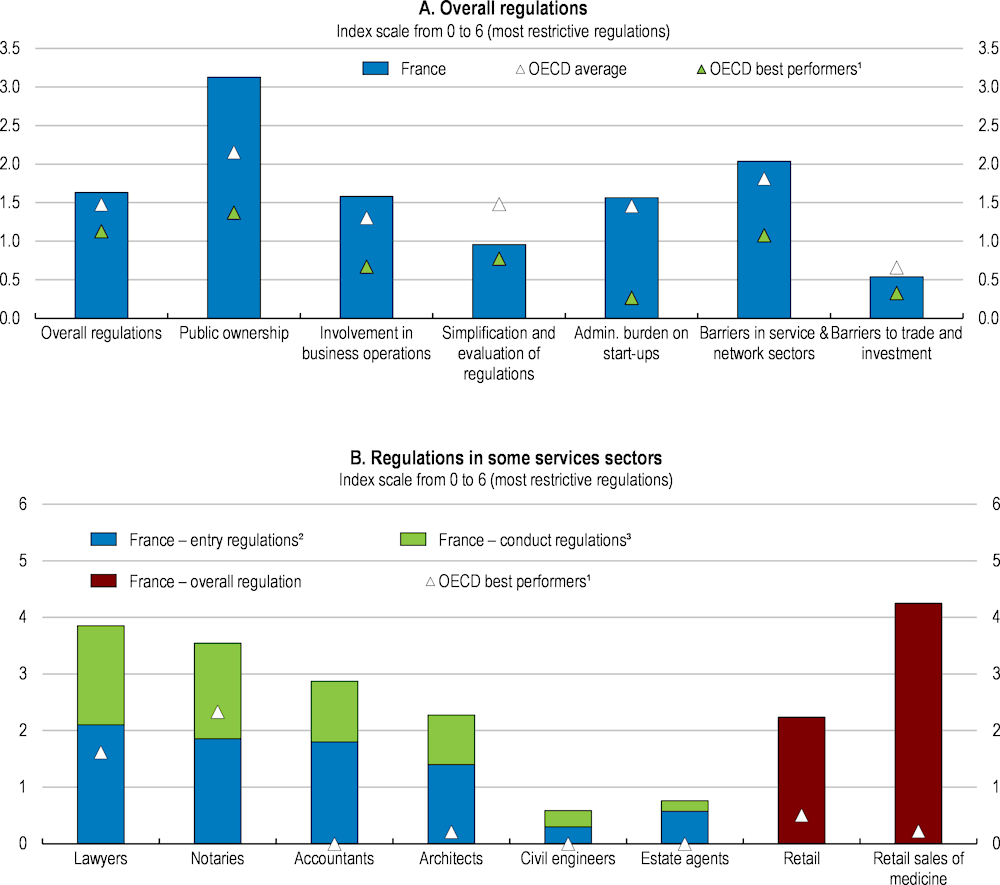

France should build on the recovery plan and the reform programme under way since 2017 to ensure a steady recovery and more inclusive growth. Though the economic rebound has been strong over the summer 2021 and France has limited school closures during the epidemic waves of 2020-21, the pandemic has highlighted a number of weaknesses in the French economy, including inadequate digitalisation among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), a mismatch between labour force skills and business needs and a persistently poor record in innovation (OECD, 2019a; CNP, 2019). The challenge is therefore to stimulate growth and create quality jobs while encouraging the digital and green transitions and ensuring the social acceptability of the reforms (Chapter 2; Dechezleprêtre et al., forthcoming). The key recommendations formulated in this Survey could generate further growth in per capita GDP, a measure close to average income, of 1.2% after 10 years.

Against this background, the main messages of this Survey are as follows:

Public policy should continue to support activity while shifting the focus of support measures towards viable businesses and sectors to allow the necessary reallocations in the economy as the recovery gains traction.

The recovery plan must encourage stronger and more sustainable growth, notably the shift to a digital economy and the green transition (Chapter 1). Structural reforms should boost productivity. Accelerating the pace of emissions reduction requires strengthened economic incentives while ensuring social acceptability.

Policies must prevent the crisis from exacerbating unequal opportunities. Building the skills of young people and low-skilled workers, facilitating professional transition and reducing territorial disparities would promote more inclusive growth.

Public debt is historically high and requires a medium-term fiscal consolidation plan to gradually lower spending. This strategy should be based on spending reviews and improved expenditure allocation.

1.1. The pandemic has caused an unprecedented recession

Emergency measures cushioned the impact of the crisis

The government implemented extensive direct budgetary support to households and businesses in 2020 and 2021. The cost of the emergency measures was around EUR 70 billion in 2020 (2.9% of 2019 GDP), according to the national accounts (RF, 2021a). In 2021, the measures will cost close to EUR 64 billion (2.6% of 2019 GDP) (Box 1.1), and implementation of the recovery plan would provide support amounting to 1.6% of 2019 GDP, notably through public investment (Box 1.2). The strengthened job retention scheme covered up to 29% of private-sector employees (full-time equivalent) in April 2020 at an estimated cost approaching EUR 35.5 billion between March 2020 and July 2021 (DARES, 2021a). Additionally, the solidarity fund, which was created to support small businesses and the self-employed, made payments to more than 2 million businesses amounting to EUR 36 billion - 1% of GDP - (IGF-France Stratégie, 2021a and 2021b; Secrétariat du Comité Cœuré, 2021).

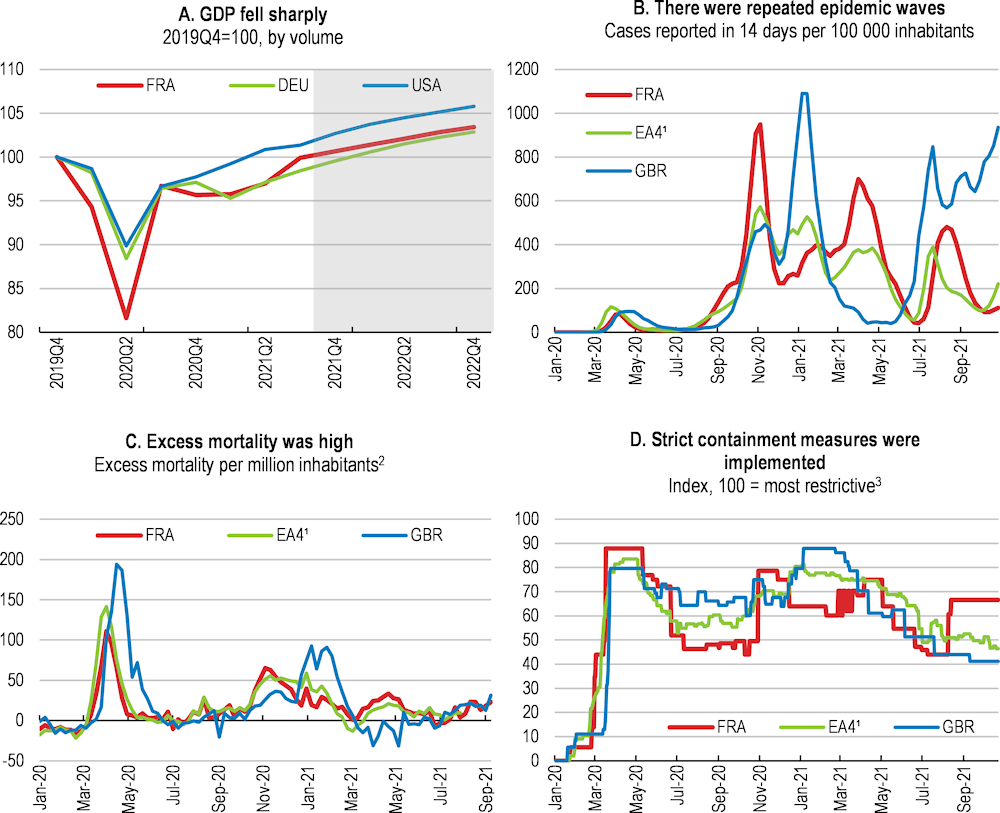

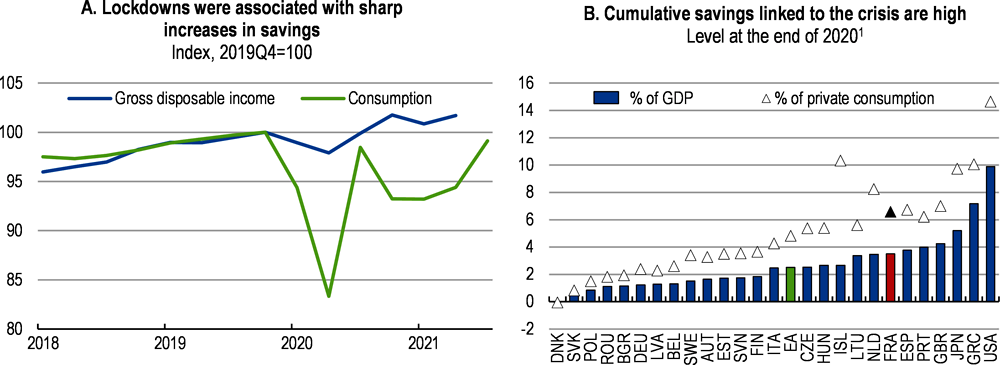

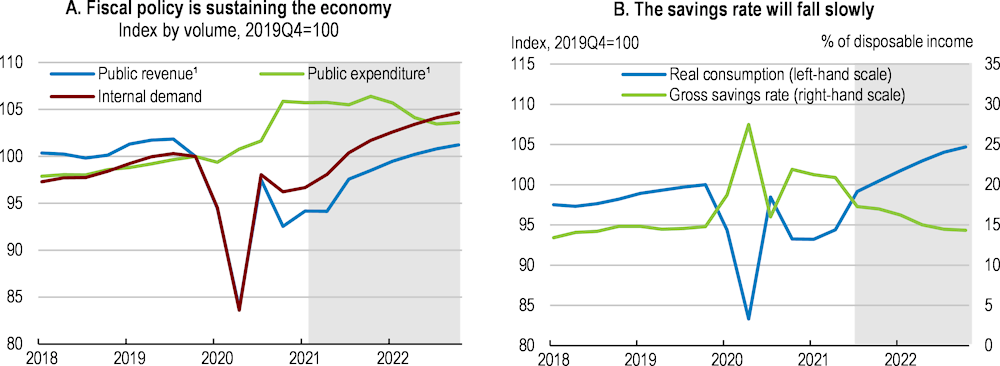

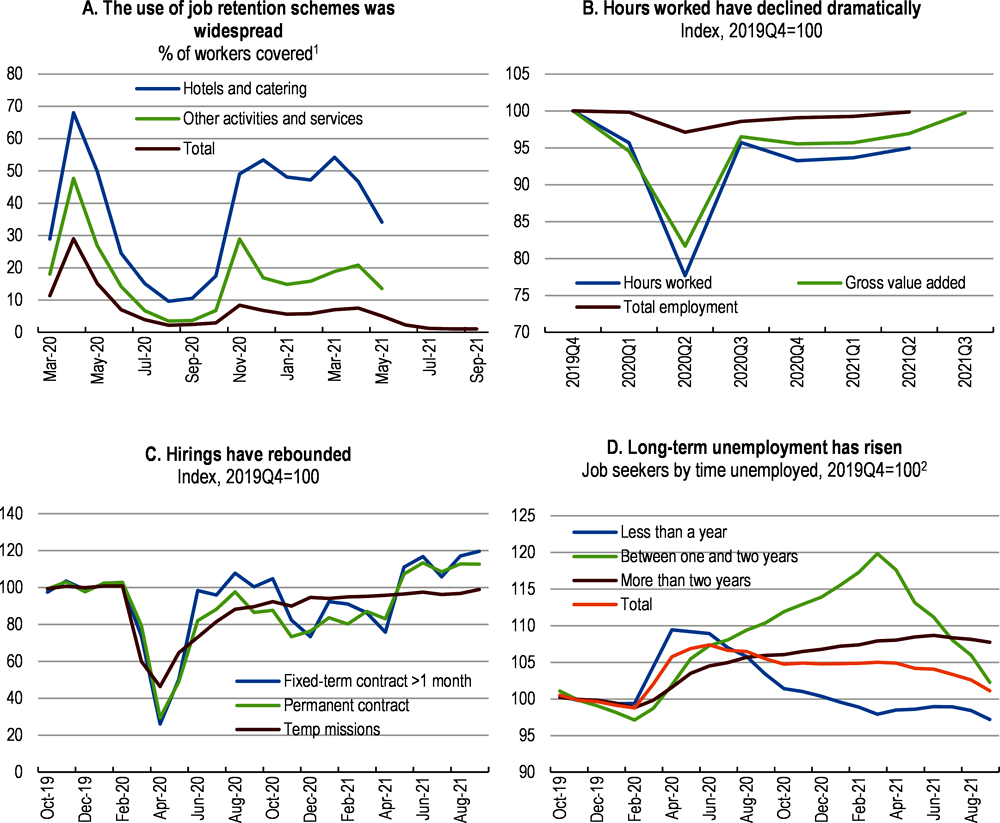

Emergency income support schemes have had a major impact. The job retention scheme, whose conditions are generous in international comparison (OECD, 2021a), was extensively used, leading to a limited fall in employment during the crisis (Figure 1.3). As a result, disposable household income continued to rise in 2020 despite the fall in GDP. Combined with the drop in consumption (Table 1.2), this generated high levels of savings, which rose to close to EUR 110 billion above the pre-crisis trend at end-2020 (around 4% of GDP in 2019), a particularly high level compared to other OECD countries (Figure 1.4; OECD, 2021b; Banque de France, 2021a). Also, as budget support significantly curtailed the recession, this reduced indirectly their budgetary cost: the net cost of the six principal support measures amount to between 67% and 81% of their gross cost in 2020 (Canivenc and Redoulès, 2021).

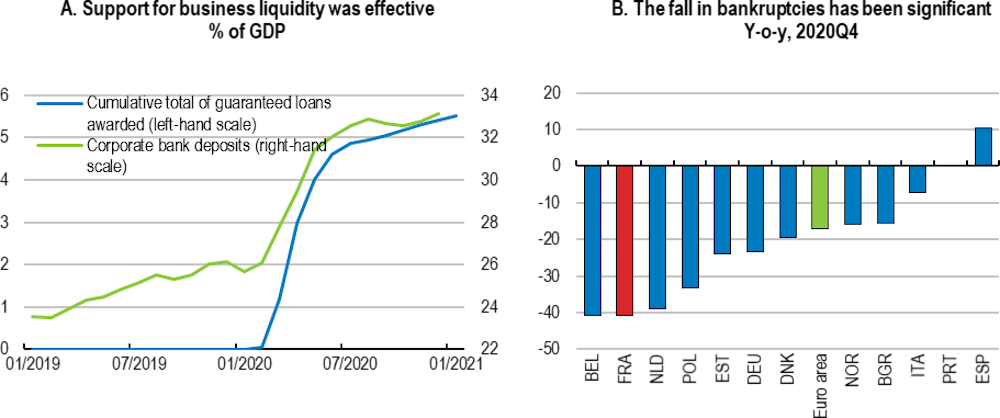

Extensive indirect support provided liquidity to businesses. More than EUR 142 billion (5.8% of GDP) in government guaranteed loan (PGE) was made available since March 2020benefitting to close to 40% of businesses (Figure 1.6 and Box 1.3; Husson, 2021). This ranks France below Spain and Italy in terms of guaranteed loans, but above Germany and the United Kingdom (IGF-France Stratégie, 2021b). Government guarantees were targeted chiefly at SMEs and export businesses, enabling them to enjoy more favourable finance terms than other loan guarantee schemes set up in Germany, Spain or Italy (Anderson et al., 2021). Moreover, together with other mechanisms, deferrals in the payment of taxes and social contributions by businesses and the self-employed also benefited corporate cash reserves. At the same time, macro-prudential regulations were eased (Box 1.4).

Box 1.1. The main fiscal measures to support economic activity in 2020-22

The French authorities introduced many timely emergency support measures since March 2020. They were subsequently supplemented by the France Relance recovery plan and the investment plan to 2030 (Box 1.2). As a result, the planned public funding amount to close to 8.8% of 2019 GDP across the years 2020-22 (according to national account definition; Table 1.1, excluding the investment plan to 2030). Added to this are measures with no effect on the fiscal balance that total up to EUR 327.5 billion in guarantees and EUR 76 billion in cash measures for businesses.

Table 1.1. The main fiscal measures to support the economy in 2020-22

|

2020 EUR billion |

2021 EUR billion |

2022 EUR billion |

Total 2020-22 EUR billion |

Total 2020-22 % of 2019 GDP |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A. Emergency measures (total)1 |

69.7 |

63.8 |

8.1 |

141.6 |

5.8 |

|

Job retention schemes (excluding those in the recovery plan in 2021) |

26.5 |

9.3 |

35.8 |

1.5 |

|

|

Solidarity fund and related support |

15.9 |

23 |

38.9 |

1.6 |

|

|

Health spending |

14 |

14.8 |

5 |

33.8 |

1.4 |

|

Exemptions from social contributions |

5.8 |

2.6 |

8.4 |

0.3 |

|

|

Extended duration of unemployment benefits and delayed reforms of unemployment insurance |

3.9 |

5.3 |

0.3 |

9.5 |

0.4 |

|

Other measures |

3.6 |

8.8 |

2.8 |

15.2 |

0.6 |

|

B. Recovery Plan, France Relance (total)1 |

1.8 |

38.2 |

30.1 |

70.1 |

2.9 |

|

Planned European funding |

16.5 |

10.6 |

27.1 |

1.1 |

|

|

A. Emergency measures, % of 2019 GDP |

2.9 |

2.6 |

0.3 |

5.8 |

|

|

B. Recovery Plan, % of 2019 GDP |

0.1 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

2.9 |

1. Includes only those measures that affect the fiscal balance in the national accounts.

Source: RF (2021), Rapport Économique Social et Financier 2022, October 2021, Government of the French Republic.

The key emergency measures are:

The job retention scheme: the scheme was made more generous for businesses and workers (OECD, 2021). The share payable by employers, which was zero between March and May 2020, varies across sectors. In the most affected sectors such as hotels and catering, the share remained at zero until the end of August 2021 and has increased gradually. In other sectors, the share has been rising since June 2020 and is set at 40% since September 2021. However, businesses that are still affected by sanitary restrictions (administrative closures, people density limits) or those in hard-hit sectors whose turnover has fallen by more than 80% continue to be subsidised in full until the end of October 2021.

Solidarity fund: the fund comprises flat-rate support to the smallest businesses experiencing a significant fall in turnover that meet certain conditions. The scheme was later extended to the sectors most affected by the crisis, such as hotels and catering, and the conditions on business size were lifted in December 2020 (Cour des comptes, 2021). In 2021, further assistance for “fixed costs” was also introduced to cover 70% to 90% of the operating losses off businesses subject to trading restrictions (RF, 2021).

Exemptions from social contributions: these involved the sectors most affected by the crisis.

Source: Cour des comptes (2021), Le budget de l'État en 2020 (résultats et gestion), report of 13 April 2021; RF (2021), Rapport Économique Social et Financier 2022, Government of the French Republic; OECD (2021), OECD Employment Outlook 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Figure 1.3. The job retention scheme contained the employment fallout

1. Employment rates are calculated in respect of the population aged between 15 and 64.

Source: Eurostat (2021), Employment and Unemployment (LFS) – detailed quarterly results; OECD (2020), OECD Employment Outlook 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Figure 1.4. The shock on household income was limited, leading to large savings

1. Cumulative savings as a result of the crisis are estimated using excess household deposits, meaning the difference between savings levels at December 2020 and a hypothetical level that assumes that, in 2020, deposits rose at the average rate for the previous five years.

Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

Box 1.2. The recovery plan, France Relance and the investment plan to 2030

The France Relance recovery plan commits to EUR 100 billion worth of measures, the majority in 2021‑22, including EUR 87.3 billion according to the national account definition. This includes France’s recovery and resilience plan worth around EUR 39.4 billion financed through the European Recovery and Resilience Facility (RF, 2021; EC, 2021). This effort is part of the Next Generation EU recovery plan that has enlarged fiscal space and will provide EUR 750 billion (about 5.5% of EU27 2019 GDP) of grants and loans to member states, funded by EU debt issuance (OECD, 2021). The main measures of France Relance are organised into three main fields:

The ecological transition (EUR 30 billion), including measures to improve the energy performance of buildings, increase rail freight, develop the use of decarbonised hydrogen and support businesses to make the transition;

Competitiveness and innovation (EUR 34 billion), including EUR 20 billion in tax cuts over two years (maintained at EUR 10 billion per annum subsequently), corporate equity-building measures and support for digitalisation; and

Social inclusion, employment and territorial cohesion (EUR 36 billion) including employment subsidies (targeted at young people and the most vulnerable), additional finance for the healthcare sector, and additional support for local government and lifelong learning.

In addition, the authorities announced a new investment plan to 2030 in October 2021. The plan, worth EUR 30 billion until 2027, would complement France Relance and notably target further investment in the energy sector (EUR 8 billion), as well as the health and transport sectors (EUR 7 billion and EUR 4 billion, respectively).

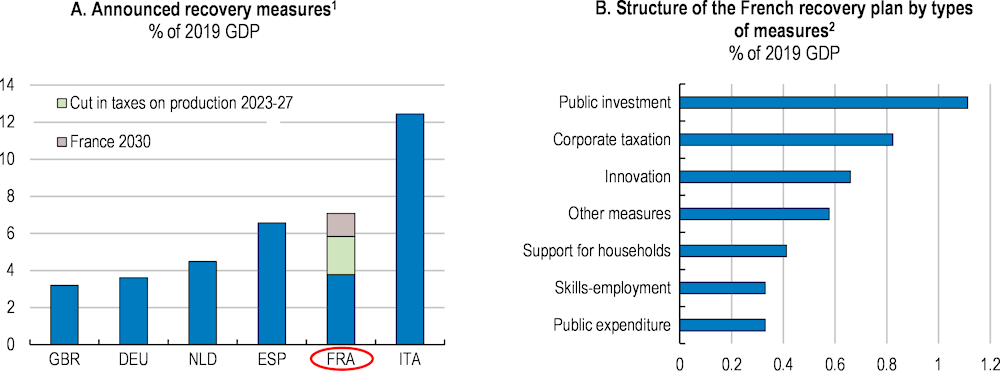

When compared internationally, the estimated recovery expenditures would rank France in an intermediate or high position, when the investment plan to 2030 and permanent business tax cuts are included (Figure 1.5). The permanent business tax cuts (EUR 10 billion annually) bring the estimated level of support to around 7.1% of 2019 GDP for the period 2020-27. Government estimates, excluding the 2030 investment plan, indicate a cumulative impact of 4% on GDP in the period 2020-27, including through support for public investment in 2020‑22 and positive spillovers from the EU recovery plan (RF, 2020).

The Monitoring and Evaluation Committee for Business Support Measures established in April 2020 and chaired by Benoît Cœuré published an initial evaluation report of France Relance in October 2021 and an evaluation through research projects is planned in 2022. The initial report notes that the objectives in terms of the amounts to be committed have been achieved or are in the process of being achieved. Yet, the medium-term effects of the plan on energy efficiency, labour-market integration of young people, as well as productivity and resilience of value chains remain uncertain (Comité d’évaluation du plan France Relance, 2021).

Figure 1.5. The recovery plan emphasises public investment

1. The measures announced cover only measures that impact the budget balance up to end-2027 at most.

2. The planned business tax cuts are accounted for in 2021-22 only. The EUR 4 billion of the 2030 investment plan in 2022 are assumed to raise public investment.

Source: OECD estimate based on IGF-France Stratégie (2021), Rapport Final du Comité de suivi et d’évaluation des mesures de soutien financier aux entreprises confrontées à l’épidémie de Covid-19, July 2021, and national sources; RF (2020), Rapport Économique Social et Financier 2021, Government of the French Republic.

Source: RF (2021), Plan National de Relance et de Résilience, Government of the French Republic; RF (2020), Rapport Économique Social et Financier 2021, Government of the French Republic ; EC (2021), Commission Staff Working Document: Analysis of the recovery and resilience plan of France, European Commission ; OECD (2021), OECD Economic Surveys – European Union, OECD publishing, Paris; Comité d’évaluation du plan France Relance (2021), Premier rapport, Octobre 2021.

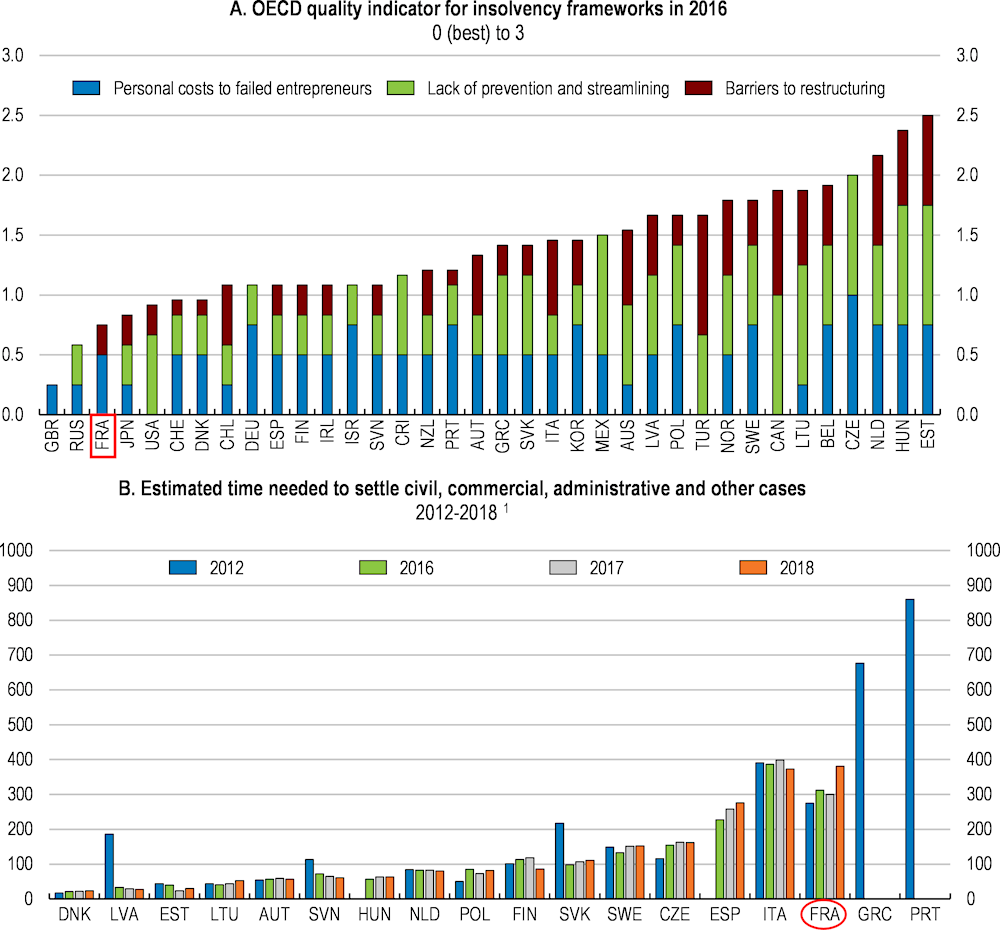

Support for business liquidity and temporary adjustements to banking regulations limited credit constraints (Figure 1.6). The annual growth in bank loans to non-financial businesses stood at 13.3% in December 2020, the highest level since 2008 (Banque de France, 2021b). As a result of both the temporary administrative changes to reduce the likelihood of petitions for bankruptcy, and the reduced activity in the courts because of the pandemic, creditworthy businesses with low cash reserves and high levels of debt were prevented from going bankrupt.

At end-2020, bankruptcies had fallen by more than 40% in France compared to the previous year, against a 17% drop in the euro area (EC, 2021a). By safeguarding otherwise viable businesses, this policy minimised the hysteresis effects of the crisis on the economy’s production capacity. According to simulations run by the Ministry of the Economy, the proportion of French businesses that would have become insolvent during 2020, on account of the impact of the crisis, was halved as a result of public support (Hadjibeyli et al., 2021). This support did not significantly influence the key factors for business failure in 2020 (Cros et al., 2020; Hadjibeyli et al., 2021).

Figure 1.6. Support for business liquidity was effective

Source: Banque de France (2021), Financial situation of households and firms; EC (2021), Quarterly registrations of new businesses and declarations of bankruptcies – statistics, European Commission.

Box 1.3. Measures to support the liquidity of businesses and strengthen their equity in 2020-21

Initial key liquidity measures

Government guaranteed loans (PGE) has accounted for EUR 142 billion of loans (5.8% of 2019 GDP) between March 2020 and August 2021(Figure 4). Representing up to 25% of turnover, PGEs enable recipient businesses to apply to spread their repayments over between one and five years at the end of the first year and, in some cases, depreciate their capital only at the end of the second year. The scheme was mainly deployed from end-March 2020 to end-2021. Small and medium-sized enterprises account for 75% of the sums allocated (Secrétariat du Comité Cœuré, 2021).

Deferrals of social contributions mainly involved very small enterprises (VSEs). VSEs, which represent around 20% of all employment, account for 56% of all deferred social contributions (IGF-France Stratégie, 2021). Non-financial business debt, in particular involving deferrals of social security and tax payments, amounted to EUR 25 billion (1% of 2019 GDP) in March 2021.

Credit mediation supported businesses in difficulties. It handled close to 14 000 case files between March and December 2020 and, in half of cases, a solution was found with the banks.

The State supported Air France-KLM with a EUR 7 billion shareholder loan.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) guarantee mechanisms have been expanded (OECD, 2021). They include the establishment of a EUR 25 billion European Guarantee Fund to deploy up to EUR 200 billion in finance to businesses throughout the European Union.

Tax credit advances and the carry-back procedure were relaxed in 2020 and 2021.

Tools to develop business equity and improve savings allocation

The long-term loan scheme (prêts participatifs Relance) guarantees business loans and was introduced in May 2021. These long-term highly subordinated loans (loans that mature after eight years where the principal is repaid only from the fifth year and that are subordinate to all other bank debts) are intended to support business investment. This mechanism could mobilise EUR 20 billion in finance, that is around 6% of non-financial business investment in 2019 (MEFR, 2021).

Created in October 2020, the Relance label aims to guide private savings towards dedicated investment funds. The label is based on a set of investment rules and environmental, social and governance criteria controlled by the French Treasury. As of September 2021, around 200 funds were labelled “relance” and amounted to around EUR 16 billion, including EUR 3.6 billion for insurers. Some 70% of the labelled funds are invested in the equity and quasi-equity of French businesses and more than 50% in SMEs and medium-to-large-sized enterprises (MEFR, 2021).

Incentives for households to invest in SMEs have been strengthened. Income tax deductions were increased to 25% for equity subscriptions from August 2020 to December 2021.

Source: Secrétariat du Comité Cœuré (2021), Chiffres clés de la mise en œuvre des mesures de soutien financier aux entreprises confrontées à l’épidémie de Covid-19; OECD (2021), Economic Survey 2021 – European Union, OECD Publishing, Paris; IGF-France Stratégie (2021), Rapport d’Étape du Comité de suivi et d’évaluation des mesures de soutien financier aux entreprises confrontées à l’épidémie de Covid-19, April 2021; MEFR (2021), Renforcer le bilan des entreprises pour la relance: présentation des prêts participatifs Relance et des obligations Relance, Ministry of the Economy, Finance and the Recovery.

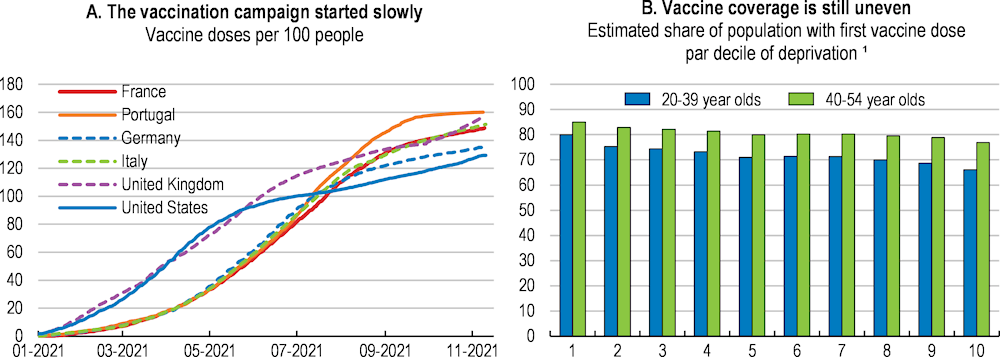

The acceleration of the vaccination campaign supports the recovery

The vaccination rollout has significantly eased pressure on intensive care units and will help to sustain the economic recovery. Although, as in the rest of Europe, the vaccination campaign got off to a slow start, it gained significant speed in the spring and summer 2021 when vaccination centres opened and vaccines were made available to healthcare professionals, and later with the implementation of the health pass. At the beginning of November 2021, 74.6% of the population was fully vaccinated, and 76.4% had received their first injection (Figure 1.7; Santé Publique France, 2021a), higher than European average rates (ECDC, 2021). At the same time, France rolled out its testing campaign, based on broad capacity and free testing until October 2021, for an estimated cost of EUR 7.7 billion in 2020-21 (0.3% of 2019 GDP).

Figure 1.7. The vaccination programme has been scaled up but remains perfectible

1. The deprivation index is defined at the municipality level as the first principal component of four variables (median income per consumption unit, the share of secondary school graduates in the out-of-school population aged 15 or over, the share of workers in the active population aged 15-64 and the share of unemployed in the active population aged 15-64).

Source: Caisse nationale de l’Assurance Maladie (2021), Taux de vaccination (en %) par indice de défavorisation au 24 octobre 2021; Our World in Data (2021), COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people.

Ensuring a steady recovery requires achieving an even broader vaccination coverage and making changes to preventive health measures. The vaccination strategy prioritised the elderly and people with comorbidities that were at risk of developing more severe diseases. The authorities also took welcome measures to target the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, such as the introduction of mobile teams. In view of the low vaccine coverage among some healthcare professionals (Santé Publique France, 2021b), vaccination was made mandatory for healthcare and care home workers, as in the United Kingdom. However, in early November 2021, vaccine coverage was significantly lower in the most deprived areas (Figure 7; Ameli, 2021) and lower than the European average for those in the 80+ age group (ECDC, 2021). The priority is therefore to scale up vaccination even more for the most fragile and vulnerable communities.

As in other countries, the spread of more infectious or more severe variants is still a risk (Advisory Panel on COVID-19, 2021a and 2021b). In order to control their spread and prevent further waves of the epidemic, the authorities introduced protective measures in summer 2021, including the health pass, social distancing in places open to the public and the administration of booster shots for the vulnerables, thus reducing the scale of potential rebound in certain business sectors. Capacity to screen adults and young children rapidly will also have to continue to grow to ensure the success of the test, track (especially upstream) and isolate (especially for people arriving from at-risk countries) strategy. Additionally, capacity to sequence variants should continue to increase. In addition, the aid to achieve higher vaccination globally should continue. The French government plans, in a welcome move, to share around 60 millions doses of COVID‑19 vaccine before the end of 2021 (PR, 2021; OCDE, 2021m).

Beyond the health challenges, the crisis has underlined the importance of anticipating and preventing risks (Pittet et al., 2020 and 2021). Planning for major risks should be the subject of recurring general and specific exercises, such as stress tests of logistical capacity, and reflected in specific targets that are regularly reviewed, such as preparation of operational capacity. All-hazards risk analyses should also include highly unlikely situations such as the simultaneous occurrence of a combination of improbable multi-hazard risks (for example, a flood followed by an earthquake) whose potential cost is very high, to ensure that response capacity is adequate.

Local risk management strategies should involve greater commitment and the formulation of a shared vision that brings together local governments and the national authorities. Little account is taken in planning and urban development policies of specific risks (such as flooding) or the comprehensive multi-hazard view of risks, including health-related, climatic, geological, seismic and technological risks (OECD, 2017a; 2018a). In Japan, the national and local authorities are closely linked through national and subnational “national resilience plans”. The aim of the plans is to ensure that the electrical, digital, rail, airport and flood-prevention infrastructures can perform as planned in the event of disaster (OECD, 2021c).

1.2. The economy bounced back when health restrictions were lifted

Macroeconomic policies are supporting domestic demand and the recovery

GDP growth will be around 6.8% in 2021 and 4.2% in 2022, and economic activity returned close to its pre-crisis levels in the third quarter of 2021 (Table 1.2 and Figure 1.8). Health restrictions have had an ever-decreasing effect on consumption patterns and mobility (Insee, 2021b; Banque de France, 2021c). After a poor start in 2021, the economy rebounded as the epidemic lessened, the vaccination campaign accelerated and health restrictions were relaxed. Moreover, while supply constraints weakened industrial performance at the beginning of 2021 and increased again over the summer 2021, some of them should gradually fade (Insee, 2021c).

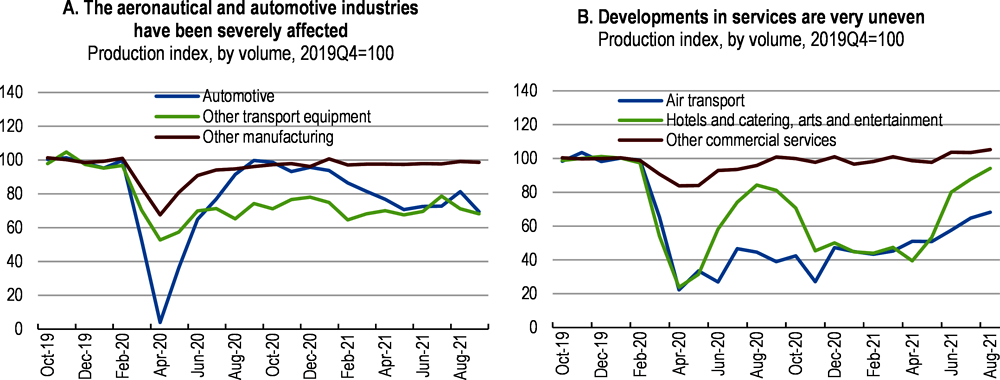

The economy strongly rebounded at the beginning of summer 2021. Despite a further wave of COVID-19 cases over the summer, the lifting of health restrictions and the reopening of certain sectors has sustained a rapid rebound in consumption (Insee, 2021d; Banque de France, 2021g). Activity in restaurants, bars, leisure and air travel services (around 14% of output in non-financial service sectors in 2015), which in March 2021 was at less than 50% of its level at end-2019, therefore recovered (Figures 9 and 10). Moreover, demand from trade partners also bounced back swiftly, and exports are likely to slowly return to previous levels following their historically low levels of 2020 and mid-2021.

Figure 1.8. The economic impact of the epidemic and containment measures has fallen

1. The Oxford Index (COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, stringency index) is based on nine indicators, including closures of schools, workplaces and travel restrictions.

Source: Insee (2021), Après l’épreuve, une reprise rapide mais déjà sous tensions, October 2021; Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

Fiscal measures strongly support domestic demand. The emergency economic and social measures (Box 1.1) together with the gradual lowering of the housing tax, will considerably lessen the crisis’ effects on household incomes and purchasing power, despite the planned cut in unemployment benefits. The recovery and 2030 investment plans and support measures that protected corporate production capacity will also support business investment. However, although robust in 2020 and during the first part of 2021 (Figure 1.2), business investment will be restrained by high levels of gross debt in some firms as well as ongoing uncertainties (notably related to the health situation and trends in aggregate demand).

The recovery will support a moderate decrease of the unemployment rate. New hires and outflows from unemployment rebounded over the summer 2021. Yet, as the take up of the job retention scheme is declining rapidly, the increase in the number of hours worked in 2021 will be sustained chiefly by an increase in working time per employee (Figure 1.11). Moreover, the normalisation of the labour force, following its dip in 2020, will temporarily push the unemployment rate upwards (Table 1.2). As these factors fade out, the labour market will tighten further. Recruitement difficulties, notably for skilled staff, have already increased significantly (DARES, 2021b).

Figure 1.9. Fiscal policy and domestic demand are driving the recovery

1. Total public revenue and expenditure is deflated by the GDP deflator. Public revenue excludes European funding in 2021 and 2022.

Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

Table 1.2. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

France |

Current prices EUR billion |

Percentage changes, volume (2014 prices) |

||||

|

GDP at market prices |

2 298.6 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

-8.0 |

6.8 |

4.2 |

|

Private consumption |

1 241.0 |

0.8 |

1.9 |

-7.2 |

4.8 |

6.8 |

|

Government consumption |

543.4 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

-3.2 |

6.4 |

1.9 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

517.3 |

3.3 |

4.1 |

-8.9 |

12.0 |

3.7 |

|

Final domestic demand |

2 301.7 |

1.4 |

2.1 |

-7.0 |

6.3 |

4.2 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

21.6 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

|

Total domestic demand |

2 323.4 |

1.4 |

2.1 |

-6.8 |

6.6 |

4.5 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

711.6 |

4.6 |

1.5 |

-16.1 |

8.2 |

7.5 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

736.4 |

3.1 |

2.4 |

-12.2 |

7.3 |

8.4 |

|

Net exports1 |

-24.8 |

0.4 |

-0.3 |

-1.1 |

0.1 |

-0.4 |

|

Note: |

||||||

|

GDP deflator |

_ |

1.0 |

1.3 |

2.5 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

|

Harmonised consumer price index |

_ |

2.1 |

1.3 |

0.5 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

|

Core HICP2 |

_ |

0.9 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

|

Unemployment rate3 (% of active population) |

_ |

9.1 |

8.5 |

8.1 |

7.8 |

7.6 |

|

Gross household saving (% of disposable income) |

_ |

14.1 |

14.7 |

21.0 |

19.1 |

15.0 |

|

General government financial balance |

_ |

-2.3 |

-3.1 |

-9.1 |

-8.0 |

-5.0 |

|

General government gross debt |

_ |

121.1 |

123.5 |

146.5 |

146.5 |

146.6 |

|

General government gross debt, Maastricht definition (% of GDP) |

_ |

97.7 |

97.4 |

115.1 |

115.2 |

115.3 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

_ |

-0.8 |

-0.3 |

-1.9 |

-1.0 |

-1.8 |

1. Contributions to changes in real GDP, actual amount in the first column.

2. Harmonised consumer price index, excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco.

3. Including overseas departments.

Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database) and updates.

Figure 1.10. Business activity remains very uneven

Source: Insee (2021), Industrial production index (IPI) and services production index (SPI).

Figure 1.11. The labour market has been seriously affected

1. Monthly trend in actual take-up of short-time work schemes (shown as FTE) in the two sectors where the scheme was used most.

2. Job seekers registered at Pôle Emploi at the end of the month in categories A, B and C in metropolitan France.

Source: Secrétariat du Comité Cœuré (2021), Chiffres clés de la mise en œuvre des mesures de soutien financier aux entreprises confrontées à l’épidémie de Covid-19; DARES (2021), L’emploi intérimaire; DARES (2021), Les demandeurs d’emploi inscrits à Pôle emploi; ACOSS (2021), Déclarations préalables à l'embauche; Insee (2021), Quarterly national accounts – detailed figures.

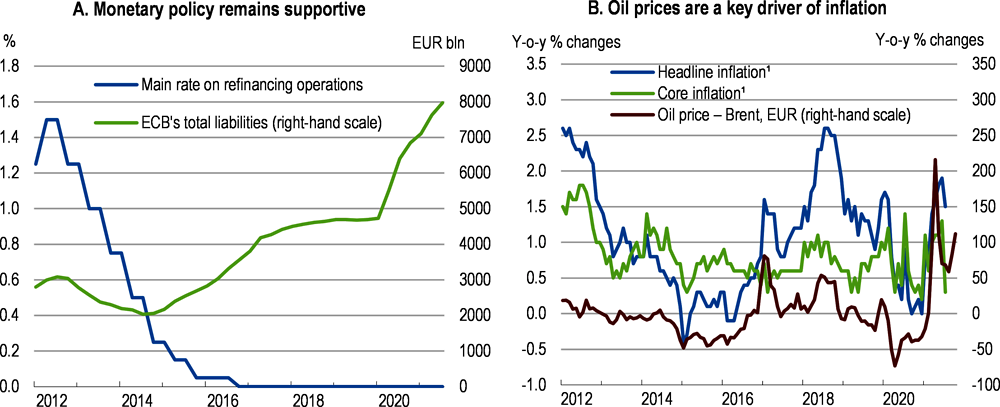

Core inflation will rise in 2021-22 (Figure 1.12). Since the beginning of 2021 and with an acceleration over the summer, the increase in commodity prices, particularly of oil and gas, together with supply problems driven both by the vigorous rebound of demand and disruption to some value chains, have been exerting upward pressure on consumer prices (Banque de France, 2021c; Insee, 2021c). So far, the trend in commodity prices has only partially been passed on in business sales prices (Banque de France, 2021e) and the scale of spare capacity in the economy is temporarily holding down core inflation. Yet, the resilience of the labour market and rising labour market shortages are set to support a pick-up in wages.

Figure 1.12. Core inflation will remain moderate

1. Harmonised indices.

Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database) and updates; ECB (2021), “Financial Market Data: Official Interest Rates”, Statistical Data Warehouse (database), European Central Bank, Frankfurt.

The risks surrounding these projections are historically high

In the short and medium term, the risks surrounding these projections are high. Passenger transport, tourism, cultural services and the aeronautical industry will probably carry lasting scars. Demand for these goods and services has fallen, and recovery is highly dependent on the health situation. Businesses have also accrued significant debt, and some of them will face liquidity and solvency issues, potentially leading them into bankruptcy. A slower recovery among France’s main trading partners in the euro area would also delay recovery in France. By contrast, a larger drop in the savings accrued during the crisis, swift use of recovery funds at European level and a faster-than-predicted recovery in international tourism would stimulate growth. Finally, a number of large potential shocks could also alter the economic outlook significantly (Table 1.3).

Table 1.3. Events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Vulnerability |

Possible outcome |

|---|---|

|

Further national or global epidemic waves, potentially linked to the emergence of new variants that are more infectious or cause more severe disease. |

Failure to combat the pandemic could increase pressure on the health system and require further preventive measures that could revert the economic recovery, particularly for the hotel and catering, tourism and leisure services sectors. |

|

Rapid, uncontrolled rise in bankruptcies. |

The overloading of commercial courts could considerably prolong the time taken to restructure debt, lead to deterioration in the banks’ balance sheets and raise risk premia and could reduce the supply of bank loans. |

|

Significant re-evaluation of interest rates. |

A sharp rise in borrowing costs would increase the pressure on public finances and the banking system. |

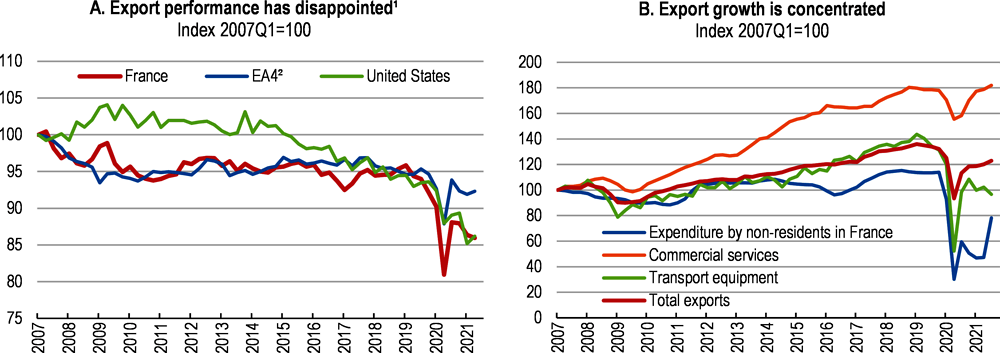

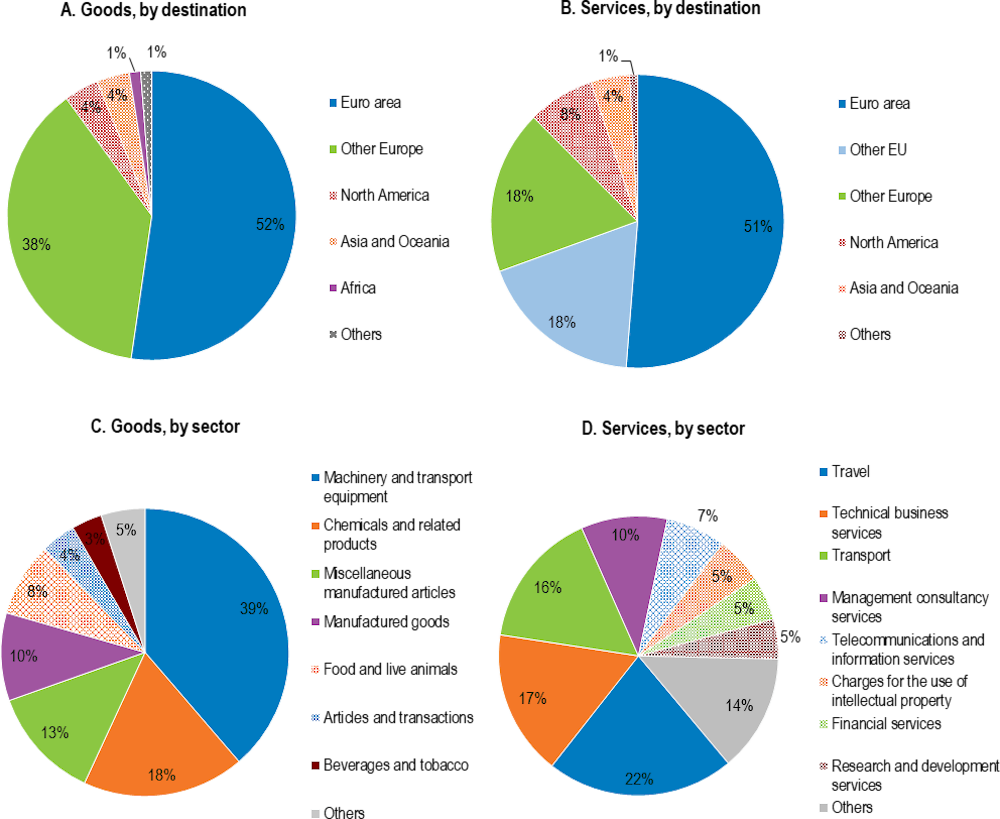

Trade performance is a key vulnerability for the French economy. France’s foreign trade performance is unsatisfactory, as exports have never returned to the levels attained on the export markets since the 2007/8 crisis and fell steeply in 2020 (Table 1.2 and Figure 1.13). In particular, in 2021Q2, exports of transport equipment, including large exports of aeronautical and space equipment, and expenditures by non-residents remained well below their end-2019 levels (Figures 1.13 and 1.14; Insee, 2021b). In mid-2021, these sectors still showed adverse changes in activity and in their outlook for recovery in the short term (Banque de France, 2021e; Berthou et Gollier, 2021). Additionally exports of services, which had been growing rapidly since 2007, had only partly rebounded. Furthermore, French businesses, which in part focused their growth strategy on increasing the numbers of their production sites, saw rapid falls in income linked to foreign direct investment. As a result, the current account has been in deficit since 2007 and stood at -1.9% of GDP in 2020.

Figure 1.13. Export performance is disappointing

1. Difference between export growth and export markets’ growth, in volume terms (based on export markets as of 2010).

2. EA4 is the simple average for Germany, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands.

Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database) and updates; Insee (2021), Quarterly national accounts (database).

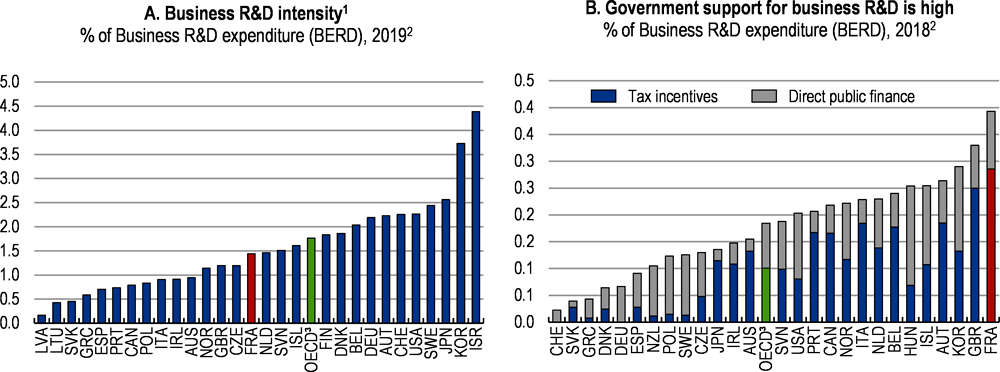

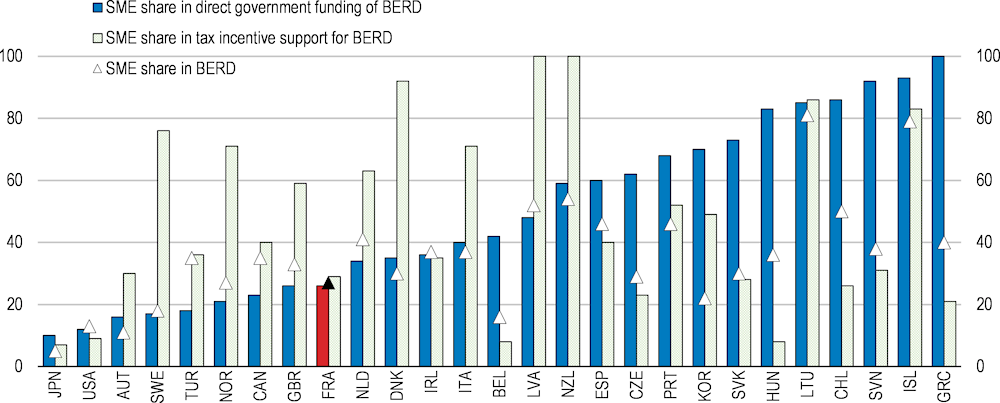

Productivity gains and improvements in non-price competitiveness are necessary to reduce exposure to external trade shocks. France’s export-market shares had stabilised over 2012-19, as the intergration of emerging countries in international trade slowed and the tax credit for competitiveness and employment (CICE) and other labour tax cuts on low and average wages have considerably reduced the labour cost of low-skilled workers. However, labour costs remain relatively high for some skilled jobs (Paris, 2019). Moreover, although the non-price competitiveness of French exports appears good in the aeronautics, cosmetics and beverages sectors, it is only average in major sectors of world trade such as machinery, electrical equipment, vehicles or pharmaceuticals (Burton and Kizior, 2021). Non-price competitiveness is notably hampered by weaker innovation than in the best performing economies.

Figure 1.14. Structure of exports

Per cent, 2019

Note: In panel C, “others” includes mineral fuels, lubricants and related materials, crude materials, and animal and vegetable oils. In panel D, “others” includes insurance and retirement-savings services, construction and cultural services

Source: OECD (2021), International Trade Statistics (database).

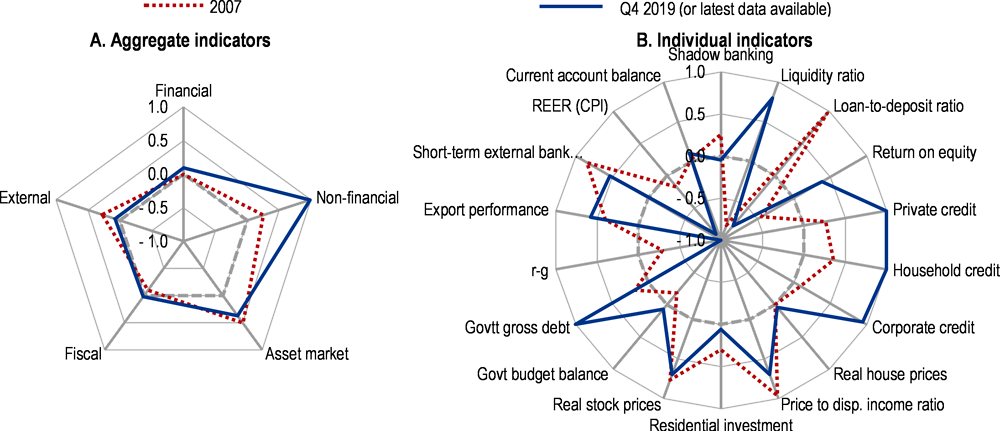

1.3. Financial risks have increased

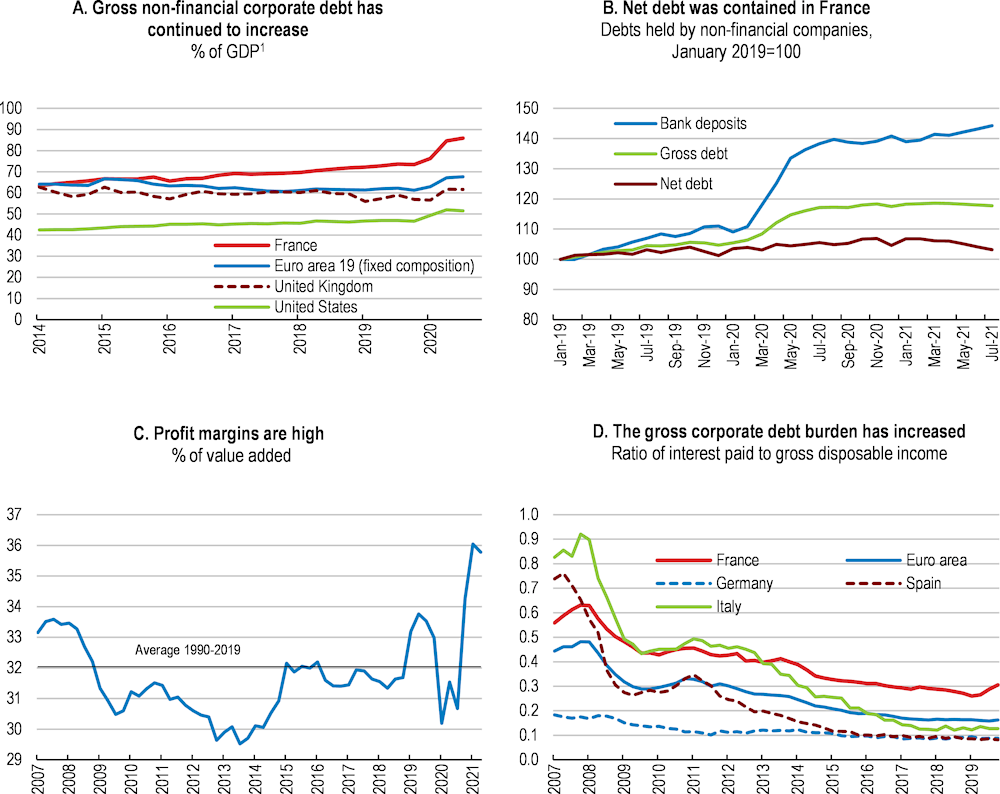

Financial vulnerabilities were contrasted before the crisis. French banks had more robust levels of equity and liquidity than in 2007 (Figure 1.15; Banque de France, 2020a). This sound situation, together with fiscal and monetary support, has so far enabled banks to effectively face increased funding needs (OECD, 2021l). However, the crisis has exacerbated pre-existing risks related to the upward trend in private debt (both household and corporate), public debt, as well as some vulnerabilities in market finance and asset management (Figure 1.15; OECD, 2019a).

The crisis has increased gross corporate debt. Non-financial businesses entered the health crisis after three years of buoyant activity, rising profit margins, low interest rates and strong cash reserves. The rise in indebtedness was down to medium and large enterprises: debt for SMEs was falling (Bureau and Py, 2021). However, non-financial corporate debt rose from 73% of GDP at end-2019 to close to 88% in 2020. This rise was largely linked to SMEs, state-backed loans and the fall in GDP (see above). Although high cash reserves and intragroup borrowing moderated the risks for the businesses involved (Khder and Rousset, 2017; Banque de France, 2020b), the combined effects of an uncertain economic outlook and an increase of payment delays undermines the financial situation of some businesses, especially some of the smallest ones (IGF-France Stratégie, 2021b).

Figure 1.15. Prior to the crisis, the risks related to public and private debt were high

Index scale of -1 to 1 from lowest to greatest potential vulnerability, 0 refers to long-term averages since 19701

1. Each aggregate macro-financial vulnerability dimension is calculated by aggregating (simple average) normalised individual indicators from the OECD Resilience Database. Individual indicators are normalised to range between -1 and 1, where -1 to 0 represents deviations from long-term average resulting in less vulnerability, 0 refers to long-term average and 0 to 1 refers to deviations from long-term average resulting in more vulnerability. Non-financial dimension includes: total private credit (% of GDP), private bank credit (% of GDP), household credit (% of GDP) and corporate credit (% of GDP). The asset market dimension includes: growth in real house prices (year-on-year % change), house price to disposable income ratio, residential investment (% of GDP) and real stock prices. Fiscal dimension includes: government budget balance (% of GDP) (inverted), government gross debt (% of GDP) and the difference between real bond yield and potential growth rate (r-g). External dimension includes: current account balance (% of GDP) (inverted), short-term external bank debt (% of GDP), real effective exchange rate (REER) (relative consumer prices) and export performance (exports of goods and services relative to export market for goods and services) (inverted).

Source: Calculations based on OECD (2021), OECD Resilience Statistics (database).

Continuing to provide liquidity to small and medium-sized enterprises and to strengthen their equity in a targeted manner is key for a resilient recovery (Figure 1.16). French businesses’ liquidity appears adequate, but the profitability of some firms (excluding public support) has been very significantly affected, and the time taken for business-to-business payments has increased (Gonzalez, 2021). While the impact of the crisis on the corporate financial situation is currently limited (IGF-France Stratégie, 2021b), the pace of the phasing out of emergency support and the implementation of the recovery plan will be critical. Extending guaranteed loans could be a partial solution: during the 2008-09 crisis, such extensions made it possible to save jobs and limit public spending (Barrot et al., 2019).

Figure 1.16. Non-financial gross corporate debt has risen rapidly

1. The non-financial corporate debt is consolidated by subtracting assets from the non-financial corporate sector’s liabilities.

Source: Banque de France (2021), “Endettement des agents non-financiers: comparaisons internationales”, Webstat database; Insee (2021).

France has introduced several measures to support equity finance, which should help to reduce the risks of high corporate debt (Demmou et al., 2021; IMF, 2021; OECD, 2020f). The main instrument – Prêt participatif Relance – incentivises the private sector to mobilise highly subordinated long-term loans backed by public guarantees (Box 1.3). While the scheme combines features of market-led selectivity and limits the administrative cost for the government, few businesses have applied so far. The insufficient business awareness about the scheme and the debt-status of the instrument may have limited its attractiveness, as well as is design and complex status (IMF, 2021). If take-up remains weaker than planned or equity needs persist, support may have to increase and the instruments adjusted, for example by selectively providing greater equity through regional investment funds co-managed by the public investment bank (Bpifrance), the regions and private partners. Moreover, further structural measures concerning insolvency procedures and corporate financing are likely to contain the systemic risks (see below).

The valuation of commercial real estate requires careful monitoring, as the French market was very buoyant in 2019, and, at that point, France was already the most expensive market among the major European countries (Banque de France, 2021b; 2018). The crisis has also accelerated profound change with a boom in homeworking that could result in a reduction in office space (ACPR, 2021; Bergeaud and Ray, 2020). The systemic consequences of the price correction experienced in this market appear limited, since the direct exposure of the insurance and major commercial banks to the commercial real estate sector accounts for less than 5% of their balance sheets (HCSF, 2017). For the moment, they are apparently resilient enough to weather a sharp price correction in prices in the office space segment of commercial real estate. However, the correction under way could reduce business investment by having a bearish effect on assets that could be used as collateral (Fougère et al., 2019).

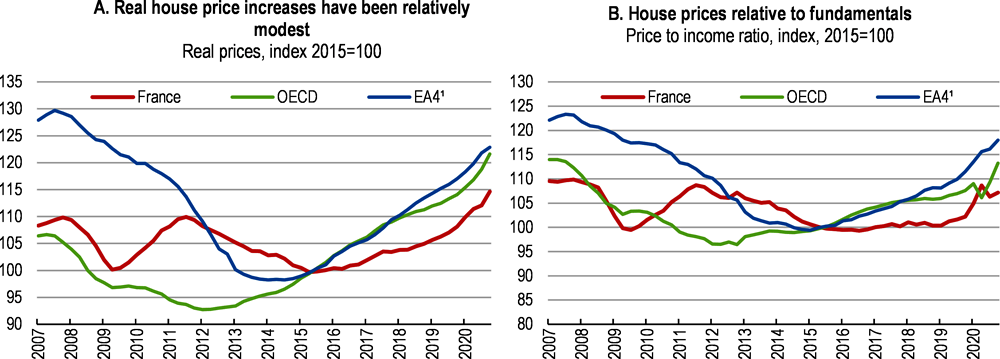

Household credit was also at an all-time peak before the crisis (Figure 1.15). The progressive easing of conditions for mortgage loans noted in recent years have made households more vulnerable, but the measures taken by the High Council for Financial Stability (HCSF) in December 2019, and then again in January 2021, made mortgage conditions more stringent (Box 1.4). The increase in real house prices since mid-2015 is less than the average for the euro area and the OECD (Figure 1.17). Price-to-rent and price-to-income ratios remain below the average for the OECD, and increases have slowed from their highs in 2011. Moreover, the nature of mortgages, which are primarily at fixed interest rates – 96% of the outstanding mortgage market in 2019 (ACPR, 2020) – speaks for the resilience of household solvency. However, a sharp increase in banks’ financing costs would adversely impact the profitability of their mortgage stock. Moreover, a sharp repricing of household assets (particularly housing) or a drop in household income if the recovery were to disappoint, would make households less solvent.

Figure 1.17. Housing market trends

1. EA4 is the simple average for Germany, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands.

Source: OECD (2021), Analytical House Price Indicators (database).

Against this background, the profitability of the French banking system should be carefully monitored. In mid-2021, the bank capital ratio remains high and close to the euro area average at close to 16% (CET1, Basel III), whereas the total capital ratio stood at 19.4% (ECB, 2021). Before the crisis, the gross ratios of non-performing loans held by French banks were low by comparison with other European countries and they have not increased so far (HCSF, 2020; Banque de France, 2021f). However, the profitability of European and French banks was low even before the crisis (OECD, 2021d; ACPR, 2021). An increase in banks’ credit risk linked to potential corporate bankruptcies and the cost of the risk could accentuate the weakness of the banks’ revenues. Even though the European measures have reduced the cost of risk (Box 1.4), the credit outlook could prove challenging. A rise in the banks’ perception of risk could push them to tighten credit standards, while an adjustment of state guarantee programmes and the need to improve corporate balance sheets could reduce corporate demand for credit.

Box 1.4. Monetary policy measures and adjustments to financial regulations in 2020-21

European regulations

The European Central Bank (ECB) expanded its asset purchase programme, allocating a further EUR 1 970 billion to the total (equivalent to 16.5% of euro area GDP for 2019; OECD, 2021). The programme is essentially a EUR 1 850 billion pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) under which net purchases will continue until at least March 2022 and to which some of the limits imposed on asset purchases by the ECB itself will not apply.

In order to preserve banking credit and liquidity, the ECB announced further targeted longer-term refinancing operations, made the funding conditions offered under targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) more favourable, and relaxed the criteria it applies when determining which assets are acceptable as collateral.

The regulatory requirements governing banking capital and liquidity ratios have been temporarily relaxed, notably through amendments to the regulation on capital requirements and the introduction of a degree of flexibility on the prudential treatment of non-performing loans (NPLs). In order to preserve bank capital, the ECB asked banks not to pay dividends or buy back shares.

Targeted amendments of the rules that apply to capital markets have been applied. Regulations on prospectuses, in the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II) and rules on securitisation, have been amended to allow issuers to raise funds quickly and facilitate recourse to securitisation, including for NPLs, so that the banks can make more loans.

Key national measures

The High Council for Financial Stability (HCSF) fully released the counter-cyclical capital buffer in March 2020.

The recommendation of the Banque de France and the ECB on the temporary suspension of any cash dividend and of any share buyback that was formulated in March 2020 was relaxed in December and extended to September 2021.

The HCSF has recommended greater prudence in granting mortgage loans. In December 2019, it recommended that debt-service-to-income ratios should not be greater than 33% (35% since January 2021) and that the loan maturity should not exceed 25 years. The recommendation will become binding in January 2022 (HSCF, 2021).

Source: OECD (2021), Economic Survey 2021 – European Union, OECD Publishing, Paris; HCSF (2021), Décision D-HCSF-2021-7 relative aux conditions d’octroi de crédits immobiliers, 29 September 2021, High Council for Financial Stability.

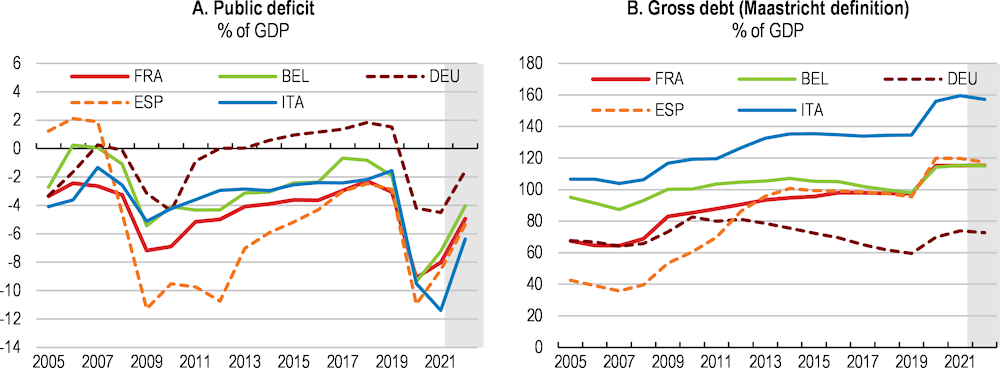

1.4. Reforming public finance to sustain the recovery

Continuing and targeting short-term support

France had been making some progress in reducing its public deficit between 2012 and 2019. It had fallen from 5.0% of GDP in 2012 to 2.5% in 2018. In 2019, by excluding a significant one-off expense caused by replacing the competitiveness and employment tax credit (CICE) with reduced employers’ social security contributions, the public deficit was 2.1% of GDP. Buoyant growth and the fall in unemployment had more than compensated for the emergency provisions made in the wake of the “yellow vests” movement. Yet, the crisis and the associated fiscal support have pushed the deficit to 9.1% of GDP in 2020. The ratio of gross public debt to GDP rose sharply in 2020, as in most OECD countries (Table 1.4 and Figure 1.18).

Figure 1.18. The deficit and public debt are historically high

Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database) and updates.

Fiscal support must be maintained until the recovery has been firmly established, but it needs to become more targeted and more limited to facilitate the reallocation of resources after the pandemic. However, in the event that risks associated with the ongoing health situation materialise, or if the recovery proves weak, it would be appropriate to retain the flexibility of the current approach, which allows public policy to be tailored to the evolution of the pandemic. This could include mobilising the state guarantee given to numerous loans.

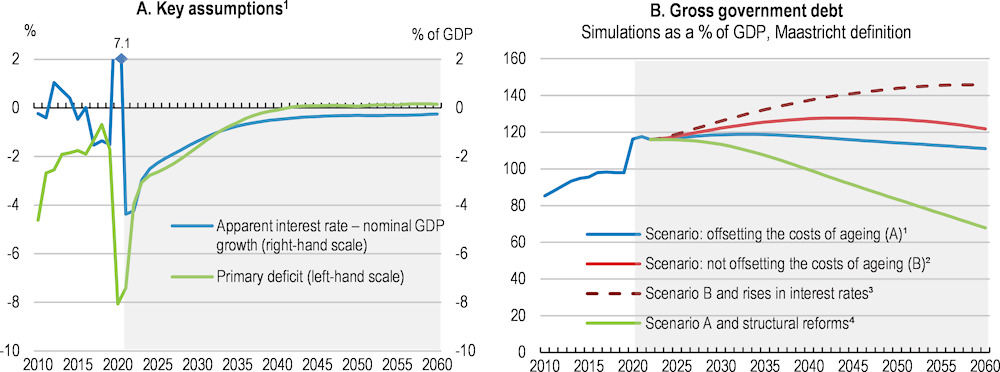

According to OECD projections, significant efforts will be required to stabilise France’s public debt at close to 120% of GDP in 2060 (Maastricht definition; Figure 1.19). Beyond 2022, the assumption is that the increase in the costs of ageing will be fully offset and that additional measures will stabilise the debt. Otherwise, the debt-to-GDP ratio will remain close to 120% of GDP and could rise to close to 150% of GDP in 2060 if the rise in interest rates proves greater than projected under the initial assumptions (Figure 1.19). That would threaten the viability of the public finances. Although clouded by significant uncertainty, the outcomes are in line with recent analyses by the Committee on the Future of the Public Finances (Commission pour l’avenir des finances publiques, CAFP) and the European Commission (CAFP, 2021; EC, 2021b)

Table 1.4. Key fiscal indicators

As a percentage of GDP

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

20211 |

20221 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Spending and revenue |

|||||||||

|

Total expenditure |

57.2 |

56.8 |

56.7 |

56.5 |

55.6 |

55.3 |

61.7 |

59.9 |

56.6 |

|

Total revenue |

53.3 |

53.2 |

53.1 |

53.5 |

53.3 |

52.3 |

52.6 |

51.9 |

51.7 |

|

Total revenue excluding European funding in 2021-222 |

53.3 |

53.2 |

53.1 |

53.5 |

53.3 |

52.3 |

52.6 |

51.3 |

51.3 |

|

Net interest payments |

2.1 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

|

Budget balance |

|||||||||

|

Fiscal balance |

-3.9 |

-3.6 |

-3.6 |

-3.0 |

-2.3 |

-3.1 |

-9.1 |

-8.0 |

-5.0 |

|

Primary fiscal balance |

-1.8 |

-1.8 |

-1.9 |

-1.3 |

-0.7 |

-1.7 |

-7.9 |

-7.0 |

-4.1 |

|

Cyclically adjusted fiscal balance² |

-2.6 |

-2.3 |

-2.3 |

-2.4 |

-2.2 |

-3.3 |

-2.5 |

-5.6 |

-4.7 |

|

Underlying fiscal balance3 |

-2.6 |

-2.5 |

-2.2 |

-2.4 |

-1.9 |

-2.4 |

-2.5 |

-6.1 |

-4.9 |

|

Underlying primary fiscal balance3 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

-0.4 |

-0.7 |

-0.3 |

-1.0 |

-1.4 |

-5.2 |

-4.0 |

|

Public debt |

|||||||||

|

Gross debt (Maastricht definition) |

94.8 |

95.6 |

98.0 |

98.1 |

97.7 |

97.4 |

115.1 |

115.2 |

115.3 |

|

Net debt |

75.3 |

77.2 |

79.3 |

77.5 |

78.0 |

78.7 |

94.5 |

95.9 |

96.2 |

1. Projections.

2. The European funding received by France will be EUR 16.5 billion and 10.6 in 2021 and 2022, respectively.

3. As a percentage of potential GDP. The underlying balances are adjusted for the cycle and for one-offs. For more details, see OECD Economic Outlook Sources and Methods.

Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database) and updates.

In order to set the debt-to-GDP ratio on a sustainable path and increase the efficiency of public spending, it is necessary to better identify the costs and benefits of each public policy while reducing the fragmentation of the budgetary processes. There are over 90 000 public entities in three categories of public administration (Cour des comptes, 2020a). This makes it difficult to identify clearly the scale and total cost of public policies and hampers the ability to make decisions on the allocation of resources. Various budgetary processes exist alongside each other and could be consolidated (Moretti and Kraan, 2018).

The establishment of a consultative body comprising representatives of the State, social security and subnational governments, and regularly opening a general debate on public revenue and the conditions for fiscal balance could increase the efficiency of the fiscal framework. The new body could be given responsibility for establishing and rolling out an expanded, multiannual expenditure rule with sectoral objectives while the High Council for Public Finances (HCFP) could be made responsible for sounding the alarm in the event of a significant deviation from the multiannual trajectory (Cour des Comptes, 2020a). Expenditure rules have a positive track record of successfully curbing the deficit bias in some European countries, such as the Netherlands and Sweden (OECD, 2021p). As envisaged by a 2021 draft law, following its analysis of the macroeconomic assumptions of the main annual budget and with a longer preparation period, the HCFP could be tasked to analyse and publish an opinion about the realism of the budgetary forecasts and evaluate their compliance to the multiannual trajectory for public finances.

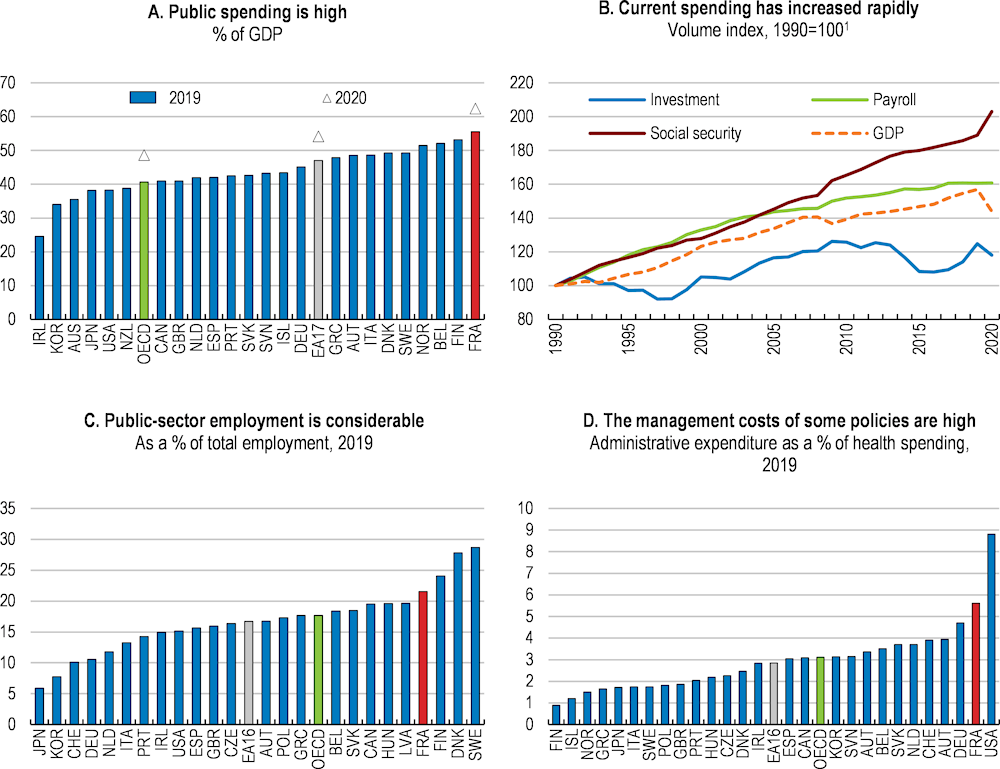

The authorities will have to regularly evaluate the efforts to rationalise public expenditures and improve their efficiency. In-depth spending reviews are necessary to implement an ambitious programme to significantly and progressively lower public spending and increase its efficiency. Public spending is among the highest in the OECD when compared to GDP, especially where social expenditures are concerned (OECD, 2020g), and welfare benefits and payroll grew strongly after the 2008-9 economic and financial crisis (Figure 1.20) and require growing tax revenues.

While the administrative costs of some expenditure are high, the outcomes in terms of reducing social and regional inequalities and performance in the education system and innovation were disappointing (see below). Established in 2017, the Comité Action Publique 2022 identified potential efficiency gains to reduce public spending. Nevertheless, the results were modest so far. The process supported the welcome modernisation of some services delivery and some reorganisation of human resources. Yet, there were no precise performance targets for public service quality or budget savings. Spending reviews could be designed to assist in identifying areas for potential savings, and improving alignment of public expenditure with strategic and political priorities, as in Canada and the United Kingdom (Box 1.5). Regular evaluations of the effects of spending reviews would be key to ensure their efficiency (OECD, 2017a).

Box 1.5. Spending reviews in Canada and the United Kingdom

Canada’s Policy on Results (2016) prioritised the achievement of results across government by enhancing transparency on which resources are allocated to achieve them and through better use of evidence including use of performance information and spending reviews (OECD, 2019). Spending reviews focused on thematic areas of spending, such support for innovation, management of fixed assets. These reviews look at spending across all of government and apply a results-driven, rather than a fiscally-driven, approach to spending assessment.

The United Kingdom is an example of linking spending reviews to mid-term fiscal strategy. Such multi-year spending reviews were introduced in 1998 (EC, 2020). They usually set 3 to 4 year capital and current budgets for each ministry, with the final year of each spending review period becoming the first year of the subsequent one – deliberately designed to deal with the rising uncertainty associated with medium-term targets.

Source: EC (2020), Spending Reviews: Some Insights from Practitioners – Workshop Proceedings, European Economy Discussion Paper, No. 135 ; OECD (2019), Budgeting and Public Expenditures in OECD Countries 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Figure 1.19. Putting debt on a sustainable path requires structural reforms

1. These assumptions are taken from the long-term model described in Guillemette and Turner (2021). In the model, the rise in spending related to ageing is offset in full, and the primary deficit develops endogenously and stabilises public debt in the long term at 2021 levels.

2. This scenario includes the costs of ageing as described in European Commission Table III.1.137 (2021c).

3. Compared to the assumptions in scenario A, the rate is 125 basis points higher in 2025 and remains stable thereafter.

4. The “OECD-recommended reforms” scenario adds the estimated effects of the reforms recommended in this Survey (Box 1.5 and Table 1.6). This scenario assumes a rise of 1.2% in potential GDP by 2033.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), June and November; and European Commission (2021), “The 2021 Ageing Report: Economic and budgetary projections for the EU Member States (2019-2070)” Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.

France also lacks long-term projections for public spending and debt. The public finance trajectories presented by the government have a five-year time frame (CAFP, 2021). Even though the annual Stability Programmes include an indicator of long-term sustainability and some long-term simulations are also published for the pension system, regularly publishing long-term debt projections for the general government and expanding the mandate of the High Council for Public Finances (Haut Conseil des finances publiques, HCFP) to include analysing the extent to which the assumptions for these projections are realistic would be steps in the right direction. For example, in the Netherlands and the United States, independent fiscal institutions are responsible for analysing long-term fiscal sustainability in periodic documents with 40- and 30-year time horizons.

Figure 1.20. Public spending efficiency must improve

1. Expenditure is deflated by the GDP deflator.

Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); OECD (2021), OECD Health Statistics 2020; OECD (2019), Government at a Glance 2019; Insee (2021), The national accounts.

Improving the allocation of public spending to support more sustainable growth

A strategy to reduce public expenditures in France should include improving their efficiency, particularly those related to local governments and tax expenditures. Lowering the public sector wage bill, and reducing pension spending in relation to GDP by raising the retirement age and easing longer careers should also be a priority. This would make it possible to finance much needed investment, especially in digitalisation, skills and the environment (Table 1.6; EC, 2021c; Guillemette and Turner, 2021). At the same time, the reduction of public spending should be associated with higher incentives for greener investment (Table 1.6 and Chapter 2). This strategy would lead to lower tax rates in the medium run, notably on labour, increasing potential growth (Fournier and Johansson, 2016). This would allow to deepen the recent reforms of in-work benefits (Prime d’Activité) and personal income taxation, which have raised work incentives, but remain perfectible (Sicsic and Vermesh, 2021; Blanchard and Tirole, 2021).

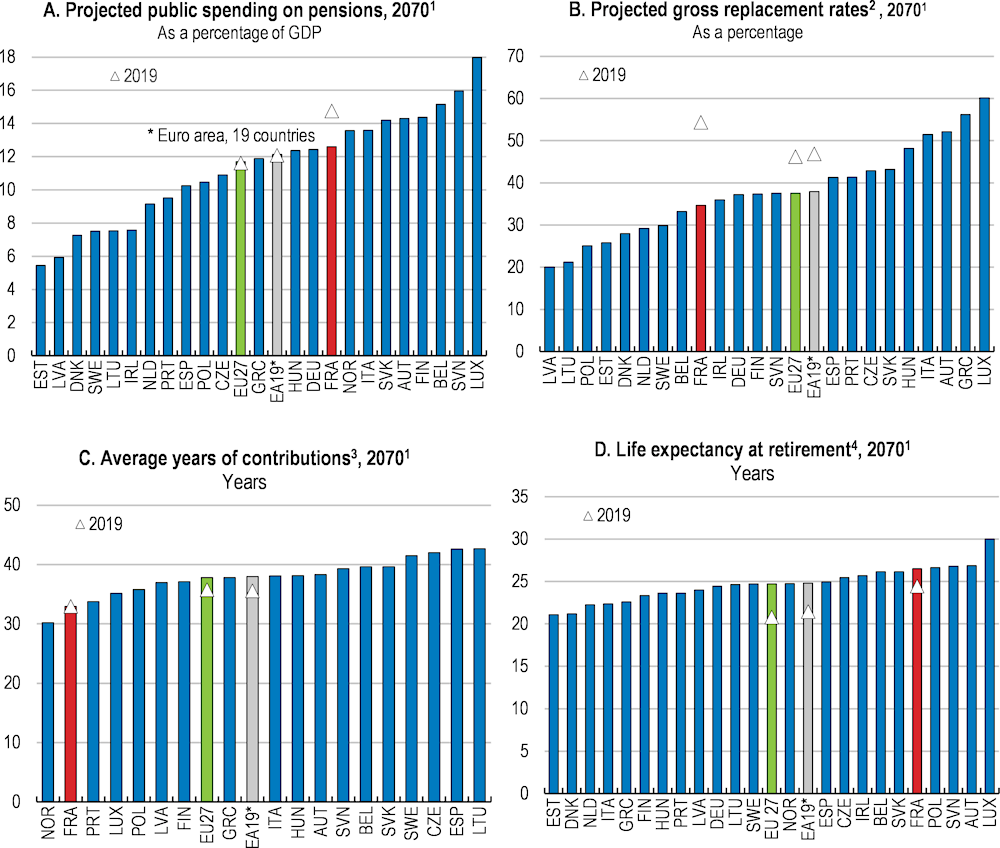

Reforming the pension system

The relatively low average effective retirement age implies high public spending on pensions and low labour participation rates among older workers, which adversely affect medium-term growth. Public pension spending is among the highest in the OECD area at about 14% of GDP (Figure 1.21). However, under the current legislation, public expenditures on pensions are set to remain broadly stable until 2040 and decline thereafter according to the projections from the European Commission (EC, 2021c). Indeed, several reforms until 2014 have increased the minimum affiliation period, progressively increased the statutory retirement age, raised incentives to delay retirement and indexed pension on prices (rather than wages) (Bellon, 2020; COR, 2021). Under the current rules, the financial sustainability of the pension system will be ensured by a rapid lowering of replacement rates (Figure 1.21), and a decline of the average pension compared to the average wage (EC, 2021c; COR, 2021). According to these projections, in 2070, projected public pension spending would be close to the euro-area average.

Figure 1.21. Public spending on pensions is set to decline alongside replacement rates

1. European Commission projections (2018).

2. Gross replacement rates are measured as the very first pension benefit relative to the last wage before retirement.

3. Average contributory period for new pensions. Contributory periods can increase for several reasons, such as, for example, rising statutory retirement ages that force employees or higher employment rates.

4. Life expectancy at average retirement age.

Source: European Commission (2021), “The 2021 Ageing Report: Economic and budgetary projections for the EU Member States (2019-2070)”, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.

The pension system suffers from numerous weaknesses. The effective contributory period to the public pension system is among the lowest in the European Union, whereas the payment period is far longer than the European average (Figure 1.22). Weak employment rates and labour market weaknesses, as well as the low effective age of exit from the labour market, reduce contribution periods and pension rights (OECD, 2019a). Moreover, the complex structure of the pension system – 42 different pension regimes coexist – prevents workers from knowing what their pension entitlement will be. The coexistence of multiple schemes with different rules also undermines labour mobility, and contributes to the inequity of the pensions system, fostering mistrust.

Several measures would be desirable to raise the employment opportunities of older workers and promote an age-inclusive workforce. Despite a significant increase over the past decade, the employment rate of the 55-64 year old remained more than 18 percentage points lower than in Denmark, Germany or Finland in 2019. Increasing the statutory retirement age in line with life expectancy through smooth and predictable indexation mechanisms could accelerate the rise in the effective retirement age (OECD, 2017c). A revision of bonuses could also make gradual retirement more attractive (OECD, 2020a). In addition, it will be important to ensure the convergence of the parameters of the special pension regimes in the private sector that often allow for earlier retirement (COR, 2016). Such measures should go hand in hand with measures to raise the employability and training of older workers and address age-based discrimination (OECD, 2019f).

The political economy of a pension reform will be key for its success. To be socially acceptable and politically feasible, the reform will need to strike a balance between a partial recognition of acquired rights, to the extent that public finances can accommodate it, possible compensations of the aggregate impacts, along with mechanisms to support the population in the reform process (OECD, 2015). Building on the reduced number of branches and the 2017 reform of social dialogue, programmes to promote quality jobs for older workers could be designed and experimented with social partners at the sectoral level to be tailored to sector-specific working conditions and skill needs. Improving working conditions and easing access to part-time jobs and flexible work arrangements would be ways to give older workers greater choice and lengthen working lives. Finland, for example, has implemented flexible working hour schemes for older workers (OECD, 2020h), and the waste sector in France has developed a comprehensive framework to reduce health risks (Bellon, 2020). Similarly, targeted support for learning could be effective in increasing the labour market attachment or probability to re-enter employment of older workers (Van Hoof and Van den Hee, 2017). The Netherlands for instance has training vouchers available to individuals above 55; and Canada has a subsidy program targeting older workers aged 45-64.

The plan to move to a single, points-based pension system was a move in the right direction. The design of adequate contributions and solidarity mechanisms will be key to a successful move to a single pension system (Boulhol, 2019). A systematic reform such as that of 2019 will need to ensure a better visibility of future pension levels and to take into account differences in working conditions and their effects on health for older workers (Boulhol, 2019; Blanchard and Tirole, 2021). To avoid creating inequities between workers and retirees, it will also be necessary to review the rules for adjusting past earnings based on wages and adjust the other parameters to ensure the sustainability of the pension system. Such reform should also address the current shortcomings in family-related pension benefits. They are heterogeneous across pension schemes, and the third child top-up tends to benefit more men than women and affluent families (Vignon, 2018). Survivor pension schemes could also be reviewed to increase incentives to work and reduce their costs (OECD, 2020a).

Better regulating social expenditures

The government temporarily provided a welcome rise in social spending during the crisis but France’s social expenditures require structural reform. In 2019, before the crisis, social expenditures represented 31% of GDP compared to the OECD average of close to 20% (OECD, 2020g). Moreover, it has grown at an annual rate of 2.7% over the last decade. The deviation from the OECD average is chiefly the result of the pension system (see above) and the recent growth in expenditure broadly reflects population ageing (Gouardo and Lenglart, 2019; DREES, 2021). However some cash benefits for care or assistance to individuals show scope for savings (Cour des Comptes, 2021d). Social expenditures, excluding pensions, amount to close to 40% of the difference in the total general government expenditures to GDP ratios between France and the Euro area average (Table 1.5).

Whether it is unemployment benefit and income support, housing assistance or family benefits, French social spending is high. Even though the benefits sharply reduce cash poverty, there is room for improvement (OECD, 2019a). The government's decisions to partially undo pensions index-linking in 2019 and 2020 and the reforms under way in respect of unemployment insurance are steps in this direction. The simplified automated scales set out as part of the Universal Income Guarantee (Revenu Universel d’Activité) would also be a move in the right direction by reducing potential tenants' access costs as well as management costs.

Additionally, housing policy instruments could also be reviewed as spending in this area is markedly higher than the European average (Table 1.5). In addition to measures to encourage a flexible rental market (see below), personal housing assistance could be targeted more narrowly at the poorest households (Cour des Comptes, 2021d). In order not to sustain inequalities between households with similar incomes depending on their access or not to social housing, setting rental supplements in relation to income, length of the tenancy and better adjusting social housing rent based on the perceived quality of the social dwelling is needed. This could also increase mobility within the social housing sector and between the social and private housing sectors (Trannoy and Wasmer, 2013).

Table 1.5. Composition of public spending by main component

20191,2

|

France |

Allemagne |

Euro Area3 |

OCDE3 |

France vs Euro Area (difference)ro |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

% of GDP |

% of GDP |

% of GDP |

% of GDP |

% points |

Share in total difference (%) |

|

|

Total public spending |

55.4 |

44.9 |

43.7 |

42.4 |

11.7 |

100 |

|

Primary spending |

53.9 |

44.1 |

42.7 |

40.7 |

11.2 |

96 |

|

Wage bill |

12.2 |

7.8 |

10.4 |

10.3 |

1.8 |

15 |

|

Investment |

3.7 |

2.5 |

3.3 |

3.5 |

0.4 |

3 |

|

Education4 |

4.7 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

4.4 |

0.6 |

5 |

|

Housing and collective equipment |

1.1 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

5 |

|

Social expenditures |

31.0 |

25.9 |

22.4 |

19.8 |

8.6 |

74 |

|

Pension |

14.0 |

10.2 |

10.0 |

8.2 |

4.1 |

35 |

|

Health |

8.5 |

8.2 |

5.7 |

5.6 |

2.8 |

24 |

|

Family |

2.9 |

2.3 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

0.7 |

6 |

|

Active labour market policies |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

3 |

|

Unemployment |

1.5 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

5 |

|

Housing |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

4 |

Note: 1. Or latest available year. 2. Numbers may not add to totals because of rounding, overlapping across selected spending categories and non-universal coverage of all spending categories.. 3. Non-weighted averages of available data. 4. Excluding pre-primary education.Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook 110 Database, OECD Social Expenditure Database (SOCX); OECD Education at a Glance 2021 Database and National accounts.

Containing local government spending

Simplifying the multiple layers of sub-central governments – known as the “mille-feuille” – could serve to make spending more efficient and, in due course, realise substantial savings. The 2014-15 territorial reforms reduced the number of regions in metropolitan France from 22 to 13 and increased the size of inter-municipal co-operation structures. They also created new governance bodies for large urban areas (métropoles). Detailed objectives were lacking however, and early indications suggest that cost savings in the short run have been limited since the merging of regional administrations were either partial or done based on the most attractive conditions. Additionally, the reforms did not fully streamline the allocation of responsibilities across different levels of local governments, suggesting significant room for efficiency gains in this area (Cour des comptes, 2017a). Additionally, the first assessments of the introduction of metropolitan areas (métropoles) and regions (régions) are unconvincing. They have so far not yet had the expected structural impact on the mutualisation of local capacities and transfers of responsibilities across administrative levels (Cour des comptes, 2019; 2020c).

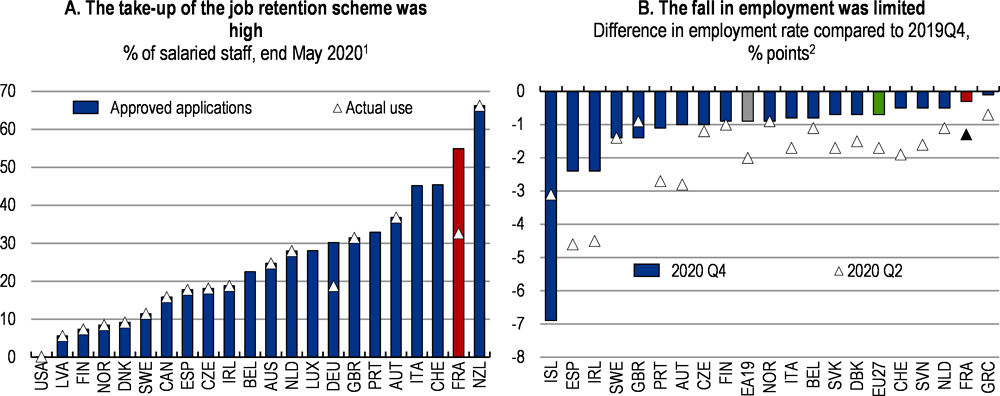

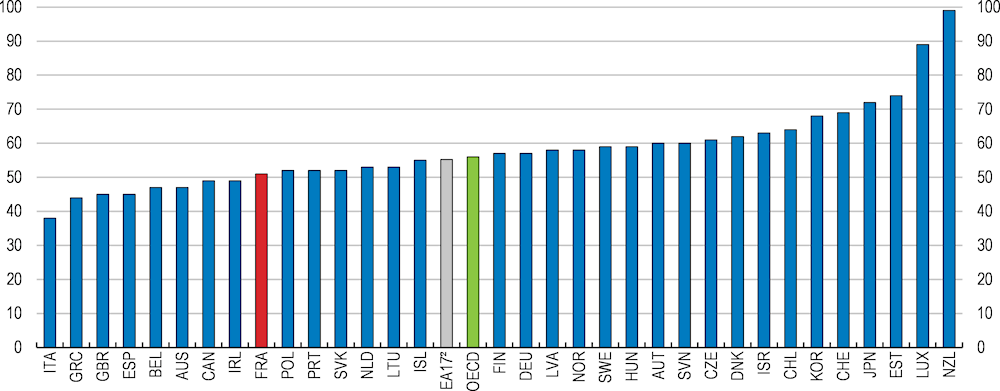

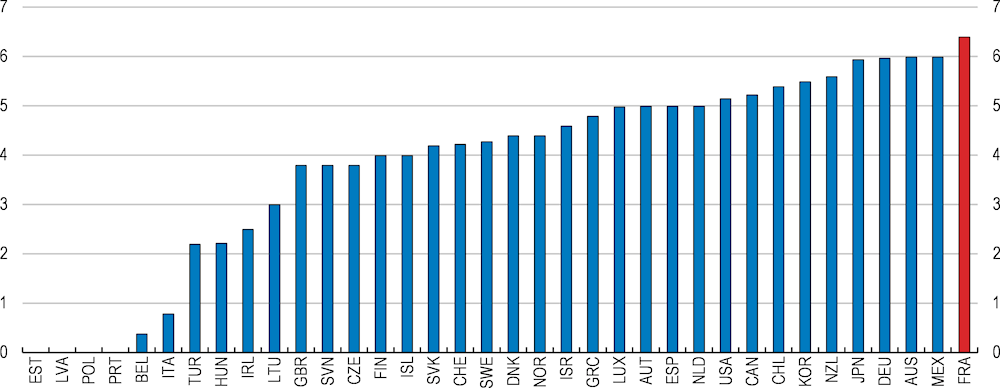

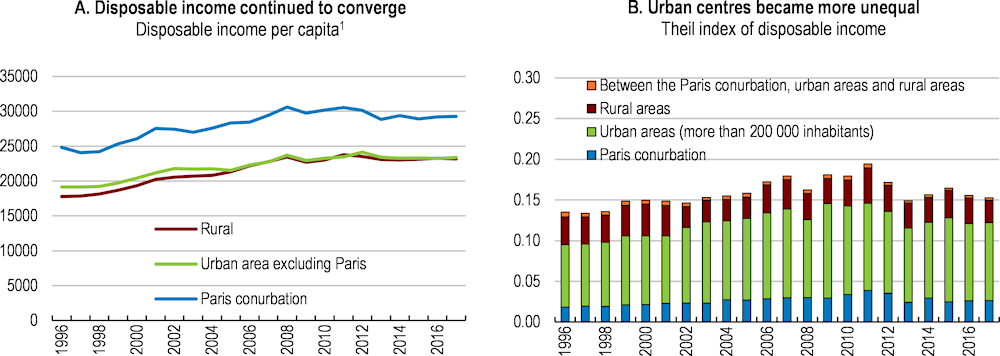

Continuing efforts to streamline small municipalities would help achieve further efficiency gains. French municipalities are small in international comparison, and French metropolitan areas are among the most administratively fragmented in the OECD (Figure 1.22). Small municipalities make it more difficult to internalise spatial spillovers in terms of urban planning, environmental costs and public services provision. They also compound co-ordination problems by spreading expertise more thinly. Asymmetric arrangements, in which responsibilities for municipalities are differentiated based on population size or urban/rural criteria, could be further developed in that respect (Allain-Dupré, 2018). The differentiation of responsibilities depending on the category of inter-municipal cooperation structures is a step in that direction. Pilot experiments like the Danish “Free Municipality” programme would also be helpful to identify the asymmetric arrangements that result in the strongest benefits. Moreover, ensuring that regulations applying to subnational governments are proportional and tailored to them would help limit the effects of those regulations on public spending (Lambert and Boulard, 2018).

Intergovernmental transfers need to reflect local governments’ spending needs more accurately in order to contain public spending growth. The main central government transfer to the municipal sector (dotation globale de fonctionnement, DGF) is complicated, as it includes multiple layers, including several equalisation components that benefit nearly all municipalities. Moreover, the lump-sum component of the DGF tends to perpetuate past spending patterns that can lead to sizeable inequalities across jurisdictions (Cour des comptes, 2016). Giving cost-based approaches a stronger role by defining a basic set of collective goods and services for delivery by local governments would help better reflect actual spending needs of municipalities.

Figure 1.22. French municipalities are fragmented

Average number of municipalities per 100 000 inhabitants, 2016

Reducing inefficient tax expenditures

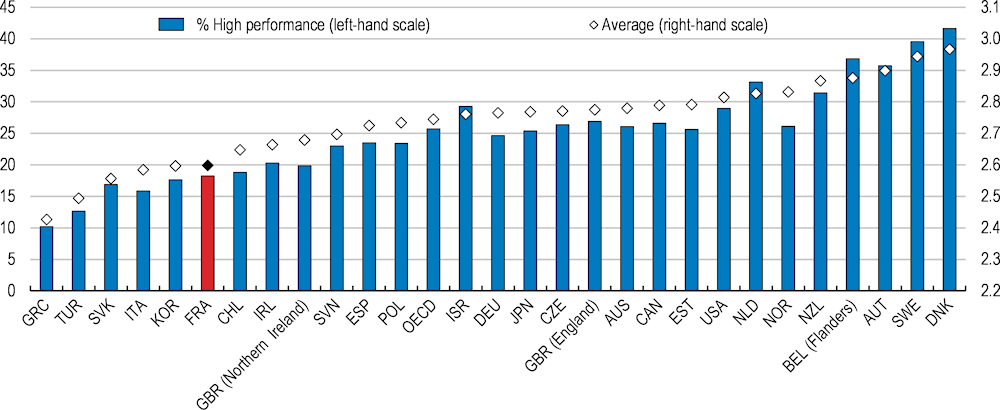

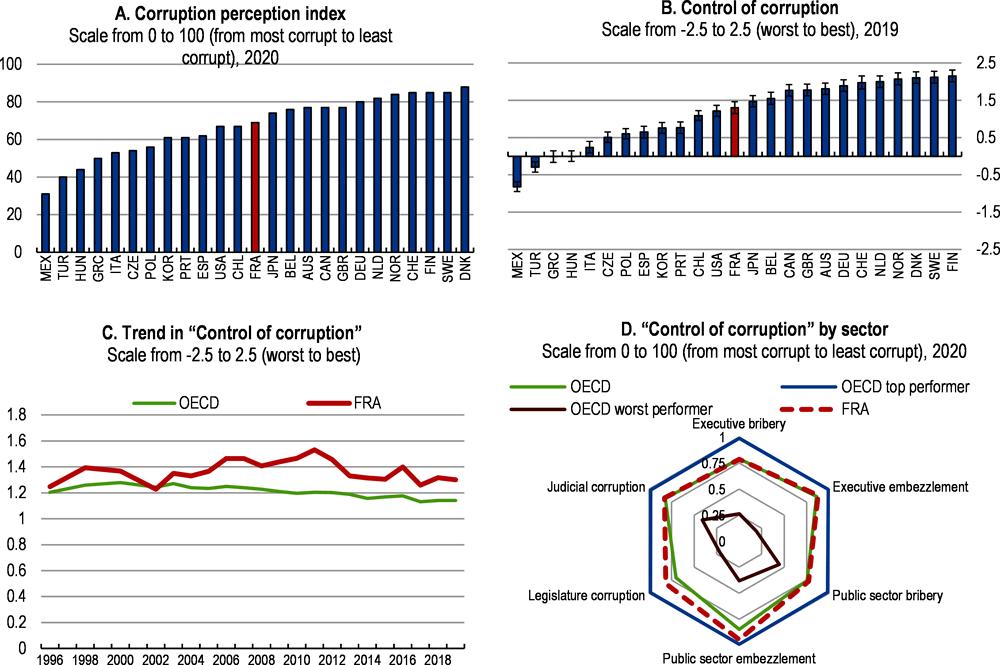

Tax expenditures are high at about EUR 80 billion in 2019 (3.4% of GDP, excluding the CICE) and can be gradually streamlined to improve the effectiveness of the tax system and its redistributive effects. These tax expenditures relate to various areas and objectives such as the tax preferences in favour of the housing sector; reduced VAT rates and VAT exemptions; or exemptions from inheritance and gift taxes, which benefit the wealthiest households (OECD, 2019a). In the short term, the high rates of saving and the surplus saving accumulated by households during the crisis would justify the removal of tax breaks on saving flows. The VAT system is complicated by the use of many reduced rates on selected items and exemptions, leading to substantial VAT revenue shortfalls (Figure 1.23). For example, the reduced rates on housing maintenance, development and renovation work have a limited impact on employment in terms of revenue cost and tend to benefit the wealthiest households (CPO, 2015). Moreover, once the recovery has gained traction in these sectors, it would be reasonable to review the reduced rates on hotels and restaurants, which have largely benefitted the owners of the businesses concerned (Benzarti and Carloni, 2019), and the most affluent households. Broadening the tax bases will have to be accompanied by lower tax rates, particularly the progressivity of the tax wedge on low- and middle-income households, to strengthen social cohesion.