This chapter analyses the continuous education and training (CET) ecosystem in Berlin. It does so in three parts. The first part provides a descriptive overview of CET participation in Berlin and puts Berlin’s CET participation rates into both a national and international perspective. The second part provides an overview of Berlin’s CET landscape, focussing on the institutional setting and existing policy instruments to increase participation in continuous education and training. It further describes existing bottlenecks in service provision. Best-practice examples from other German federal states and OECD cities are provided throughout the chapter. The third part then zooms in on promising initiatives that could help Berlin increase CET participation among vulnerable population groups.

Future-Proofing Adult Learning in Berlin, Germany

4. Strengthening adult learning for inclusion and social mobility

Abstract

In Brief

CET participation in Berlin is low compared to other OECD cities and German federal states. Participation in formal and non-formal CET outside the workplace is low in Berlin compared to international peer cities across the OECD. Labour Force Survey data shows that around 10% of individuals aged 25 to 64 participated in formal or non-formal education and training outside the workplace in the four weeks prior to their interview in 2019. Microsensus data shows that less than 14% of individuals aged 15 or over participated in formal or non-formal work-related CET in the year 2019, the lowest share among Germany’s federal states.

One of the key reasons for the low CET participation rate in Berlin is the large share of microenterprises, self-employed and own-account workers. In Berlin, 83% of Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) employ fewer than five employees. In addition, 13.5% of Berlin’s total employed were self-employed in 2019, a much higher share than in all other German federal states. The majority among the self-employed are own-account workers, i.e. self-employed without any employees. In Berlin, both awareness of existing measures as well as the take-up of instruments remains very low among Berlin’s microenterprises, suggesting that support beyond financial incentives is necessary to increase CET participation among employees in SMEs. Own-account workers in Berlin currently receive little support to overcome their financial and time constraints to participate in life-long learning.

The wide range of adult learning guidance services in Berlin caters to many different groups specifically but can also make it difficult for learners to navigate through offers. Next to the offers by the Bundesagentur für Arbeit (“Federal Employment Agency”; BA), different Senate departments offer CET guidance services to a range of target groups, with some overlap. Among the existing online offers, the visibility of the comprehensive Berliner Weiterbildungsdatenbank (“CET database Berlin”; WDB) could be improved and become a promising tool to facilitate participation in learning and training offers. Such efforts could form part of a wider public outreach campaign to foster awareness of the benefits of lifelong learning.

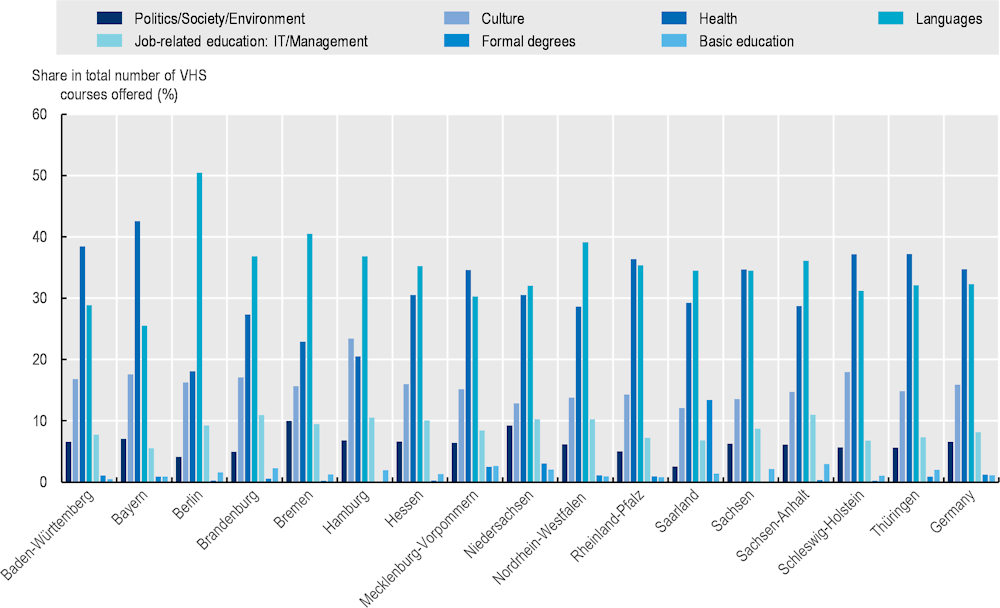

CET and career guidance measures exist for migrants, but offers are scattered and some synergies are left unexploited in Berlin. The courses in highest demand in Berlin’s Volkshochschulen (“Adult education centres”; VHS) are German language courses taken by migrants and refugees. However, Berlin’s VHS currently do not offer institutionalised career, education or labour market guidance to these groups. Among the non-institutionalised existing measures, it is not always clear why some guidance services only target refugees, but leave out other migrants who likely face similar obstacles on the labour market.

Promising initiatives that target vulnerable groups have emerged within Berlin’s social economy. Berlin has an active social economy that supports and complements adult learning measures by the Public Employment Services (PES), the federal government, and the federal state government. For example, social economy actors target groups such as functionally illiterate adults through basic education and literacy courses as well as refugees through courses on digital skills that do not require German language skills.

CET participation in Berlin: a national and international comparison

Continuing learning beyond initial education is essential for adults to keep up with a rapidly changing world of work. Labour market megatrends in digitalization, the automation of production processes and a changing demography impact the skills required to perform jobs. Participation in CET measures that aim to update and upgrade skills continuously is therefore essential to maintain the employability of people and increase labour force participation. Adult learning systems therefore have to be evaluated on participation metrics and obstacles to participation in adult learning that could prevent some individuals or groups from participating in education and training beyond their initial education. This section provides an overview of formal and non-formal CET participation in Berlin and puts participation rates into national and international perspective.

There are three types of CET participation: formal, non-formal and informal education. Different survey data sources consider different types of learning when asking survey participants if they engaged in education and training in a specified period prior to the interview. The reference period also largely differs between data sources. Thus, any national and international comparison needs to ensure comparability by specifying both the type of learning or education it refers to and the reference period it considers. Definitions of the three different types of learning and how these are measured in the survey data used within this report are detailed in Box 4.1.

Box 4.1. Differences between formal, informal and non-formal education and their measurement in different German data sources

To measure and compare participation in training and education across countries and regions, it is necessary to define the type of education and training the individuals engage in. The reference period needs to be considered to make data sources comparable.

Types of training

Three different types of education are typically distinguished in official data sources (OECD, 2021[1]).

Formal education and training: Formal education is intentional learning within institutions recognised by government authorities, which last for a minimum of one semester. Examples of formal education include upper secondary school and university studies.

Non-formal education and training: Non-formal education is intentional, institutionalised learning of either less than one semester within institutions recognised by government authorities, or education and training outside educational institutions. Non-formal education includes courses, workshops, guided on-the-job training and seminars.

Informal education and training: Informal education refers to less organised forms of intentional learning outside an institutional environment. Informal education can happen in daily life, in a family environment or in the workplace.

Main data sources to measure participation in training

Three main data sources are used within this report to compare CET participation in Berlin to other regions and cities.

The first is the European Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS). The EU-LFS reports data on formal and informal education individuals participated in within four weeks prior to the interview. Importantly, the EU-LFS does not include guided on-the-job training (GOTJ), one of the main forms of non-formal education and training in most EU member states (European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, 2015[2]). EU-LFS based CET participation rates are calculated as the number of 25 to 64 year olds who participated in training, divided by the total population aged 25 to 64.

The second data source used for this study is the German Microcensus. The German Microcensus captures job-related training and retraining measures such as lectures or weekend courses, the attendance of technician or master schools as well as the attendance of job-related courses and seminars. Work-related training can take place within the company or at the workplace, in special training centres of companies, associations or chambers of crafts. It can also take place as distance learning. A requirement for counting as a participant in GOTJ is a completed initial education or adequate work experience. Courses that serve the general education or formal vocational training do not count as work-related training. The report uses the measure as a crude proxy for GOTJ; the data captures both training at the workplace and away from it. The CET participation rates based on the Microcensus are calculated as the share of individuals in the labour force aged 15 and above who participated in GOTJ over the past 12 months, divided by the total labour force.

The two measures based on the EU-LFS and the Microcensus thus complement each other. However, the different reference periods, the different underlying populations as well as the limited overlap between the two mean that they cannot be added up to an aggregate measure. Both measures are estimates based on the sampled population rather than population counts.

A third data source referenced in this report is the IAB Establishment Panel. The IAB Establishment Panel is an annual survey of approximately 16 000 businesses, representative on the federal state level. Two CET measures can be calculated based on the survey: The first measure is the share of businesses offering education and training. Surveyed companies are classified as offering CET if they either offered training themselves during working hours or covered (parts of) the costs of internal or external training courses for at least one of their employees within the first two quarters of the given year. The denominator is then the total number of companies. The second measure is the share of employees that participated in job-related training in the first two quarters of the year. Surveyed businesses are asked to estimate (or, if possible, accurately count) the number of employees who participated in CET over the past six months. This number is then summed up over all companies within a given region and the sum is then divided by the total number of employees in the region.

Despite broadly capturing the same metric, the German Microcensus and the IAB Establishment Panel can show very different CET participation rates. The main reason is the underlying population: The Microcensus-based CET participation estimates are calculated as a share of the entire labour force, which includes both the unemployed and the employed aged 15 and above. The employed in the Microcensus also include own-account workers, a group excluded from the IAB Establishment Panel. For example, in Berlin, own-account workers made up 11% of all employed in 2017 (Senatsverwaltung für Integration, 2019[3]).

It should further be stressed that none of the three CET participation measures used within this study includes informal education or training. Unlike the German Microcensus and the EU-LFS, the IAB Establishment Panel does not explicitly exclude informal learning. However, it is unclear to what extent employers are able to factor in informal learning when estimating the number of CET participants within their company. The inclusion of informal education and training is also the main reason why CET participation rates in Germany calculated based on other (Eisermann, Janik and Kruppe, 2014[4]).

Source: European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (2015[2]), Job-related adult learning and continuing vocational training in Europe a statistical picture; Senatsverwaltung für Integration (2019[3]), Solo-Selbstständige arbeiten oft prekär und schlecht bezahlt; Eisermann, Janik and Kruppe (2014[4]), Participation in adult education: The reasons for inconsistent participation rates in different sources of data.

CET participation does not capture all human capital accumulation, especially in cities. As a result, baseline statistics on formal an informal CET participation rates are likely to underestimate the full extent of learning and training that raise human capital. Of the types of learning described in Box 4.1, informal learning is not included in the data analysis conducted for this study. Academic research on learning in big cities shows that the relatively higher amount of social and business contacts in cities facilitate informal learning. Box 4.2 describes the link between population density and informal learning. Consequently, data on CET participation in Berlin comes with the caveat that it might only offer an incomplete picture. To mitigate this issue, this section also compares Berlin to other major OECD metropolitan areas that would have similar patterns of informal learning.

Box 4.2. The link between population density and informal learning

A study by de la Roca and Puga (2017[5]) finds that higher wages in cities are not explained by the spatial sorting of more productive workers into big cities, nor by static agglomeration advantages of big cities. Instead, workers who move to cities receive an immediate static premium and gain valuable work experience quickly upon arrival. Further evidence suggests that these findings can be generalised to an even larger degree: The size of the labour market where the work experience was acquired partly explains differences in future wages (Peters, 2020[6]).

The main takeaway of these studies is that learning in big cities – or dense urban environments – often takes place outside of classrooms.

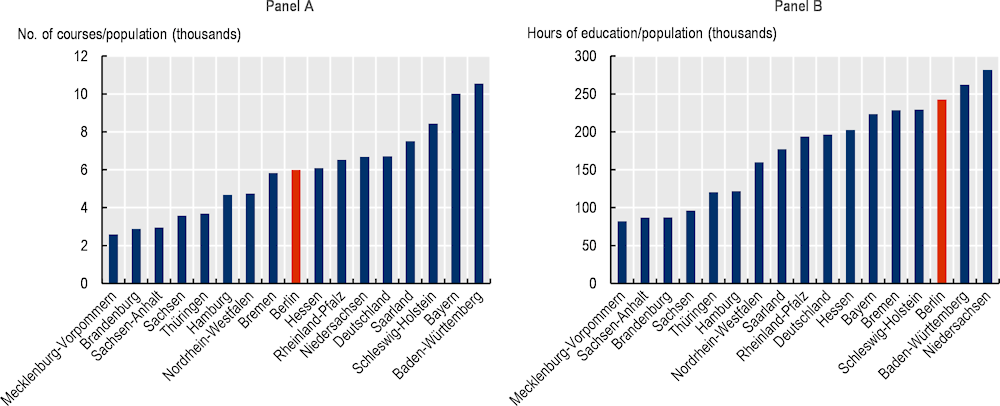

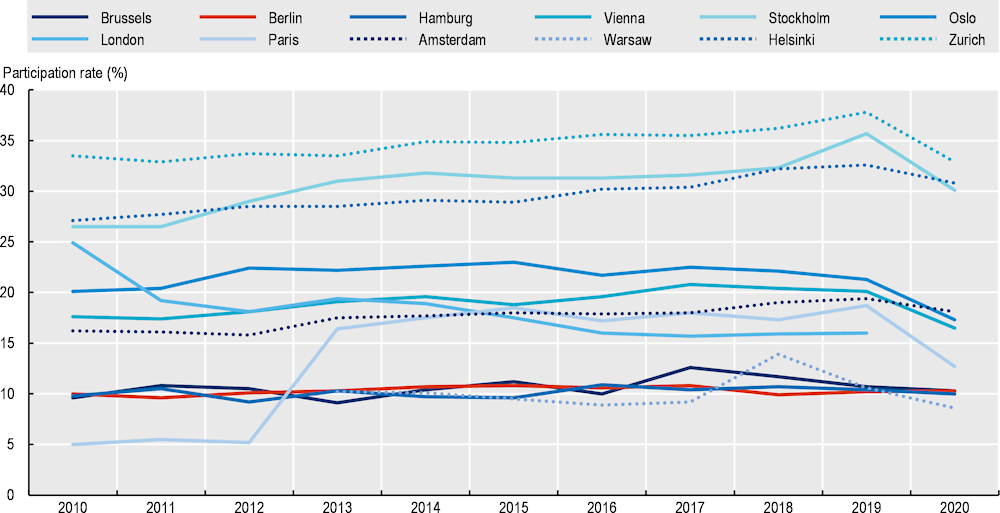

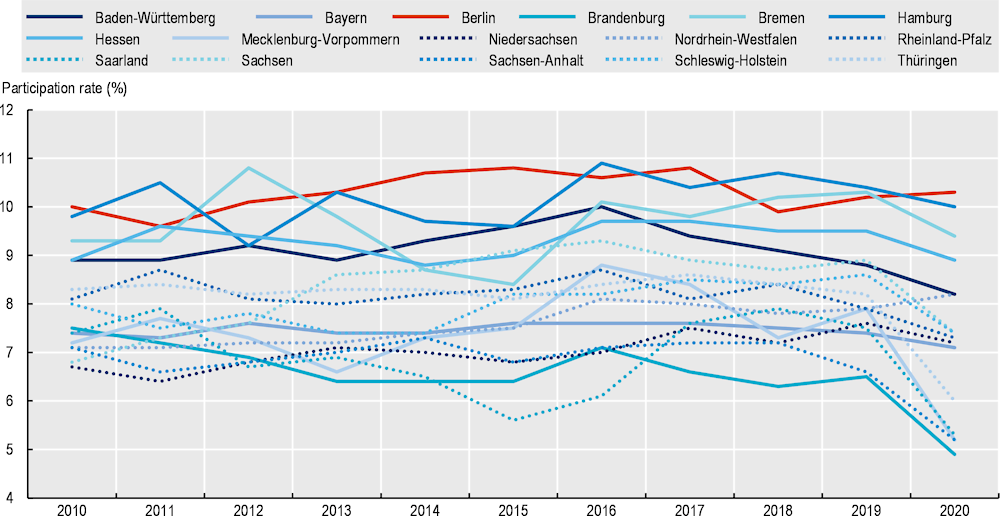

Participation in formal and non-formal CET outside the workplace is low in Berlin compared to international peers across the OECD. Figure 4.1 shows the share of individuals aged 25 to 64 who participated in formal or non-formal (excluding on-the-job) education and training in the four weeks prior to the interview between 2010 and 2020. The graph compares Berlin to other OECD cities. Berlin’s CET participation rate remained constant at around 10% over the observation period. Internationally, Brussels (Belgium) and Warsaw (Poland) show similar participation rates in formal and non-formal (excluding on-the-job) education and training. Other OECD cities such as Helsinki (Finland), Stockholm (Sweden) or Zurich (Switzerland) have much higher participation rates than Berlin. In 2020, participation rates stood at 30.8%, 30.1% and 32.9% respectively in these cities. In London (United Kingdom) and Paris (France), the capital regions of similarly sized European countries, the most recent reported participation rates were 16% and 13% respectively, well-above the level of Berlin.

In Germany, CET participation rates in formal and non-formal education in Berlin are on a par with other city states and higher than in non-city federal states. Figure 4.2 shows the share of individuals aged 25 to 64 who participated in formal or non-formal (excluding guided on-the-job) education and training in the four weeks prior to the interview between 2010 and 2020. The graph compares Berlin to the other German federal states. The national comparison shows that Berlin’s participation rate in formal or non-formal (excluding on-the-job) education and training is on the same level as Hamburg’s and Bremen’s, the other German city states. In 2020, participation rates in these cities were 10.0% and 9.4% respectively. All non-city German federal states report slightly lower participation, down to 5.3% in the federal state of Saarland in 2020. Between 2019 and 2020, participation increased only in Berlin and the federal states of Nordrhein-Westfalen. It should be noted that these participation rates are unadjusted and do not account for differences in age and education of the respective population in the different federal states.

Figure 4.1. Participation in education and training that excludes guided on-the-job training is low in Berlin compared to other OECD metropolitan areas

Note: Brussels refers to the Brussels capital region. Paris refers to the Île de France region. Amsterdam refers to the Noord-Nederland region. The data does not include guided on-the-job training.

Source: Eurostat Regional Database [trng_lfse_04], based on EU-LFS data.

Figure 4.2. Participation in education and training that excludes guided on-the-job training is high in Berlin compared to other German federal states

Note: The data does not include guided on-the-job training.

Source: Eurostat Regional Database [trng_lfse_04], based on EU-LFS data.

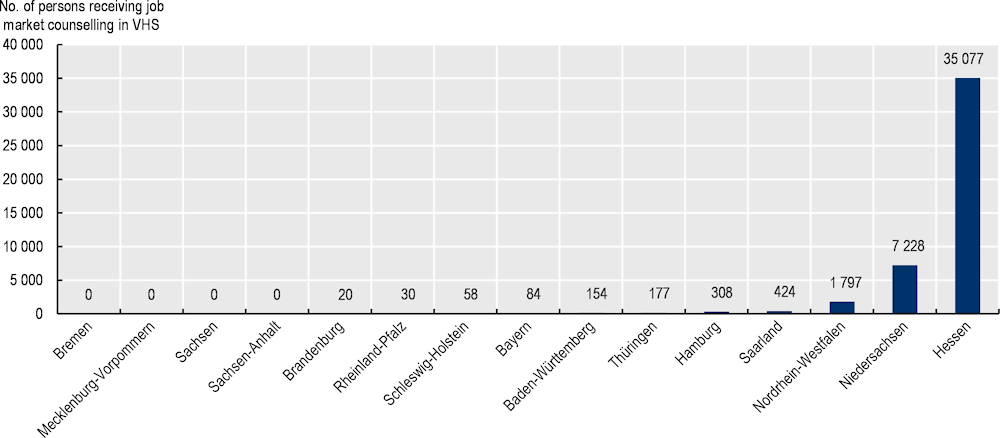

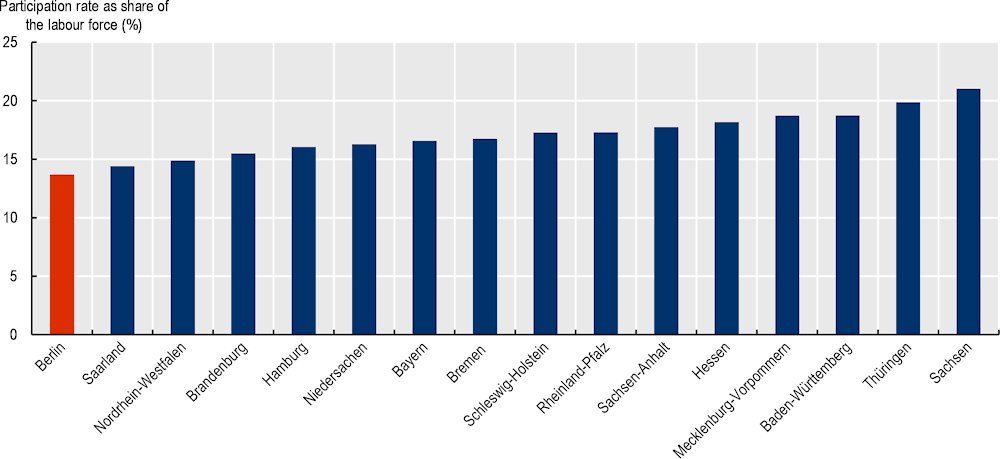

Berlin lags behind all other German federal states for work-related CET. While Berlin has relatively high CET participation outside the workplace the picture is much less favourable for work-related formal and non-formal CET. Based on the most recent Microsensus data, less than 14% of individuals aged 15 or above participated in formal or non-formal work-related CET in 2019. In Sachsen and Thüringen, the two states with the highest participation, around 21% and 20% of the labour force participated in such CET offers respectively (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3. Berlin lags behind other German federal states for work-related formal and non-formal CET participation

Note: Work-related CET participation refers to any participation in further education and training as well as retraining programmes of individuals aged 15 and above, either on the job or outside the job. Participation in CET requires completed initial education. General adult education for purposes other than professional development is not included in the CET measure. The denominator is the regional labour force (“Erwerbspersonen”).

Source: OECD calculations based on Microcensus Germany.

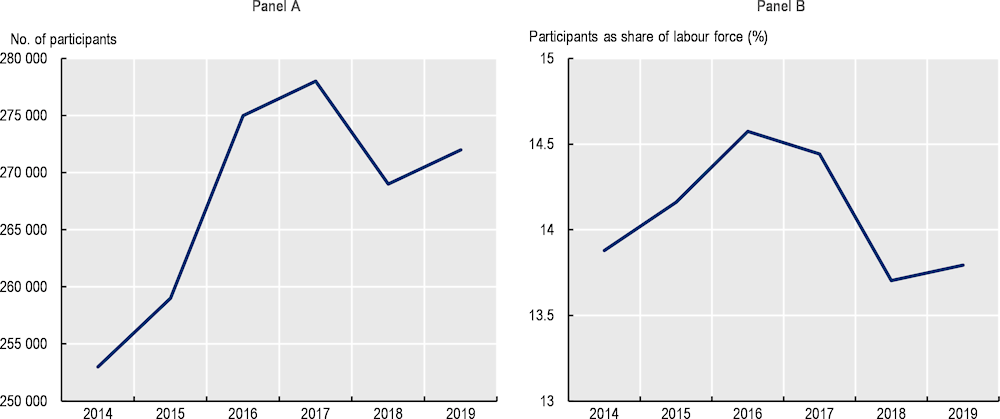

Low work-related CET participation rates in Berlin are not a new phenomenon. For the period since 2014 for which comparable statistics based on the German Microcensus can be produced, work-related CET participation was constant at around 14% of the labour force (Figure 4.4, Panel B). The estimated total number of participants grew from 253 000 in 2014 to 272 000 in 2019, in line with the growth of the labour force in Berlin (Panel A). Consequently, work-related CET has not increased in Berlin despite its growing importance in a rapidly changing labour market (see Chapter 2). The data from 2019 do not take account the effects of the pandemic. Since COVID-19 caused a range of social-distancing measures and took a financial toll on many firms, it likely reduced work-related CET further.

Unique demographic, social and economic characteristics by themselves cannot explain the low CET participation rate in Berlin. A 2018 study by the Deutsche Institut für Erwachsenenbildung (“German Institute for Adult Education”; DIE) calculates expected CET participation rates in all German federal states accounting for structural regional differences, such as the local age structure, average education levels and differences in average income. Holding these variables constant, the study shows that Berlin only utilised 77.4% of its CET potential in 2015, the second lowest value in Germany. Only the federal state of Saarland utilised less of its CET potential (75.4%). On the other hand, some federal states such as Baden-Württemberg and Rheinland-Pfalz managed to reach CET participation rates above their potential, with 119.7% and 117.3% respectively (DIE and Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018[7]).

Figure 4.4. The share of Berlin’s population participating in work-related formal and non-formal CET has remained constant over time

Note: Work-related CET participation refers to any participation in further education and training as well as retraining programmes of individuals aged 15 and above, either on the job or outside the job. Participation in CET requires completed initial education. General adult education for purposes other than professional development is not included in the CET measure. The denominator of the right-hand side figure is the regional labour force (“Erwerbspersonen”).

Source: OECD elaboration on Microcensus Germany.

Local demographic, social and economic characteristics can only account for one third of the differences in CET participation rates across Germany. Thus, other factors such as the quality of CET, visibility of the different CET offers, cooperation between different local CET actors and the CET guidance infrastructure are likely to play an important role (DIE and Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018[7]).

CET offered by Berlin’s companies is heavily dependent on the company size. Table 4.1 shows the share of companies offering education and training courses to employees by company size. The first column shows the size of the company measured by the number of employees. The second column shows the share of companies in the respective size category that offered education and training courses to their employees in 2019, the year before the COVID-19 outbreak. In 2019, only 49% of companies with fewer than 10 employees offered education and training opportunities to their employees. This share rises sharply with the size of the company: Among companies that employed 10 to 49 employees in 2019, the share stood at 70%, while almost all larger companies employing 50 or more individuals offered employees some form of job-related training.

The share of companies offering training and education courses dropped sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially among very small enterprises. Comparing the second and third column of Table 4.1 reveals that the share of companies offering training and education to employees dropped sharply in Berlin. In 2019, 57% of all Berlin based companies offered some form of education or training to employees. In 2020, that share dropped to 33%. While companies of all sizes reduced their CET offer, very small enterprises (less than 10 employees) recorded the largest relative fall (-42%), followed by enterprises with 10 to 49 employees (-40%).

Table 4.1. CET offered by companies of all sizes dropped sharply during COVID-19

Education and training offered by company size in Berlin, 2019 and 2020

|

Size of the company by number of employees |

Share of companies offering CET in 2019 |

Share of companies offering CET in 2020 |

|---|---|---|

|

<10 |

49% |

28% |

|

10 to 49 |

70% |

42% |

|

50 to 249 |

91% |

65% |

|

250+ |

97% |

76% |

|

Total |

57% |

33% |

Source: IAB Establishment Panel, waves 2019 and 2020.

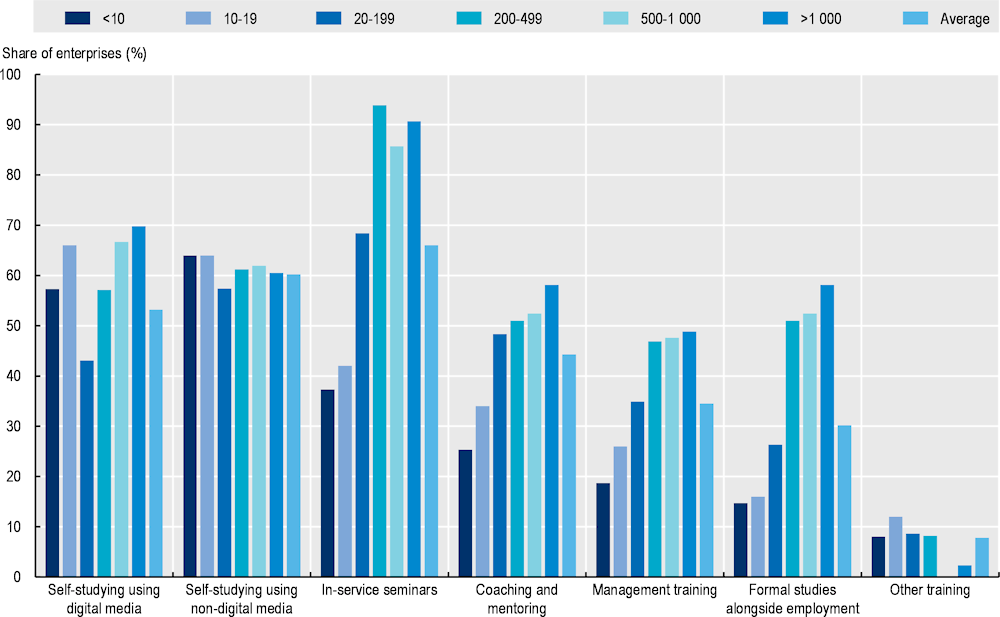

The type of training offered by companies in Berlin also depends on the company size. Data from an Industrie- und Handelskammer Berlin (“Chamber of Commerce and Industry”; IHK Berlin) survey conducted in 2019 shows that smaller companies more often rely almost exclusively on self-studying instruments to train their employees. Figure 4.5 shows that 53% and 60% of Berlin’s companies (that are IHK Berlin members) offer self-studying using digital media and self-studying using non-digital media respectively, with little variation across companies of different size. However, companies with larger numbers of employees more often offer non-self-studying training instruments. For example, only 37% of companies that employ fewer than 10 employees offer in-service seminars, compared to 94% of companies employing between 200 and 499 salaried employees. Similar trends can be seen in coaching and mentoring, management training and the possibility of pursuing formal studies alongside employment. The gap between the share of the smallest companies and the share of companies employing between 200 and 499 employees that offered these types of training in 2019 stood at 26 percentage points, 32 percentage points and 36 percentage points respectively.

SMEs and microenterprises in particular tend to underinvest into CET due to a lack of resources and insufficient investment incentives. The issue of little CET investment in small companies is not a Berlin-specific problem and exists for two main reasons: First, SMEs may lack the financial and human resources to offer job-related training. Second, they may lack the incentives to invest into their staff since more qualified staff may demand higher wages; if SMEs are unwilling to pay workers according to their additional (marginal) productivity after new skills are acquired, these workers may leave the firm and small businesses suffer a net loss from the training investment (Brunello et al., 2020[8]).

However, the lack of awareness of training needs, the lack of capacity to assess skill needs and the lack of knowledge about existing training opportunities may also play a role for underinvestment into CET in SMEs. Recent OECD research shows that very small SMEs in particular often do not have their own human resource department and rarely employ specialists on skill development. Assessing skill needs, developing targeted training measures and obtaining external funding are often time-intensive tasks that require specialist employees (OECD, 2021[9]).

Investment into CET by small companies in Berlin may therefore be too low. Additional investment into CET leads to upskilling in workers that allows them to transition into higher quality jobs, earn higher salaries and create additional tax income. Incentivising SMEs to invest more into CET through financial and logistic support can thus be desirable if there is evidence that such measures could lead to an increase in structured education and training offered within or by the small company.

Figure 4.5. Small companies in Berlin rely heavily on self-studying methods

Note: "Management training" refers to the German Aufstiegsfortbildung, a type of training that aims to qualify employees to take on management responsibilities and advance their careers.

Source: Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Berlin (IHK Berlin), “Aus- und Weiterbildungsumfrage 2019”.

The share of very small businesses among SMEs in Berlin is slightly higher than in other German regions, exacerbating the problem of underinvestment into CET. In Berlin, 83% of SMEs employ fewer than five employees, compared to 81% in Germany. In total, 58% of Berlin’s working population was employed by SMEs in 2018 (KfW Research, 2018[10]). Even small differences in company size among SMEs may make a large difference in CET offers. Table 4.2 and Figure 4.5 show that training offers drop sharply in microenterprises, compared to SMEs with 20 or more employees.

Another factor that might hold back CET participation in Berlin is self-employment. The share of self-employed among all employed is much higher in Berlin than in other German federal states. Figure 2.11 shows that 13.5% of Berlin’s total employed were self-employed in 2019, a share much larger than in all other German federal states. In addition to the large number of self-employed in Berlin, own-account workers made up 11% of all employed, corresponding to 74% of all self-employed (Senatsverwaltung für Integration, 2019[3]). In Germany as a whole, 54.4% of all self-employed were own-account workers in 2019. Thus, a much larger share of the self-employed in Berlin are own-account workers than in other German cities and regions.

Own-account workers tend to participate very little in continuous education and training, even compared to other self-employed. Across the OECD, CET participation among own-account workers is very low compared to all other workers. OECD analyses show that conditional on age, gender and education, only adults outside the labour force and the unemployed are less likely to participate in CET courses. Compared to the employed, own-account workers are 11% less likely to receive education or training. On the other hand, their willingness to participate in CET is similar to that of full-time employees (OECD, 2019[11]).

The low participation of own-account workers in education and training is explained in parts by their relatively stricter financial and time constraints. Own-account workers often work longer hours due to additional time needed to look for future work assignments. The cost of training is another major barrier to CET participation among own-account workers. Public financial support programmes typically target the employed or the unemployed, such that both the direct and the indirect costs of CET have to be borne by own-account workers themselves. Own-account workers also tend to have fewer legal rights to training since they lack union representation (OECD, 2019[11]).

In summary, Berlin’s low CET participation in international comparison and its very low work-related CET in national comparison are likely caused by a combination of factors. The main challenge is the large share of very small firms, self-employed and own-account workers. The obstacles these groups face to participate in education and training in larger numbers were likely aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to additional financial pressure and new challenges such as social distancing requirements within companies. Pre-existing trends towards the automation of production processes and the need for digital skills accelerated. Policies are therefore needed to re-invigorate CET in Berlin. The next section takes a closer look at Berlin’s CET landscape.

Berlin’s CET landscape: Funding and service delivery

As CET ultimately benefits the learner, there are important questions on when and how to use public funds to increase CET participation. CET is important as it prepares adults for their future careers and ensures that companies remain competitive by developing skills in their workforce that respond to changes in production processes. Thus, the main incentive to invest into CET lies with individuals and companies. Nevertheless, some individuals and companies face barriers to CET participation that well-targeted policy instruments can overcome. This section provides an overview of Berlin’s CET landscape. It introduces the main actors in Berlin, distinguishes between different types of instruments used and analyses complementarities between services offered by the German federal government and the government of Berlin.

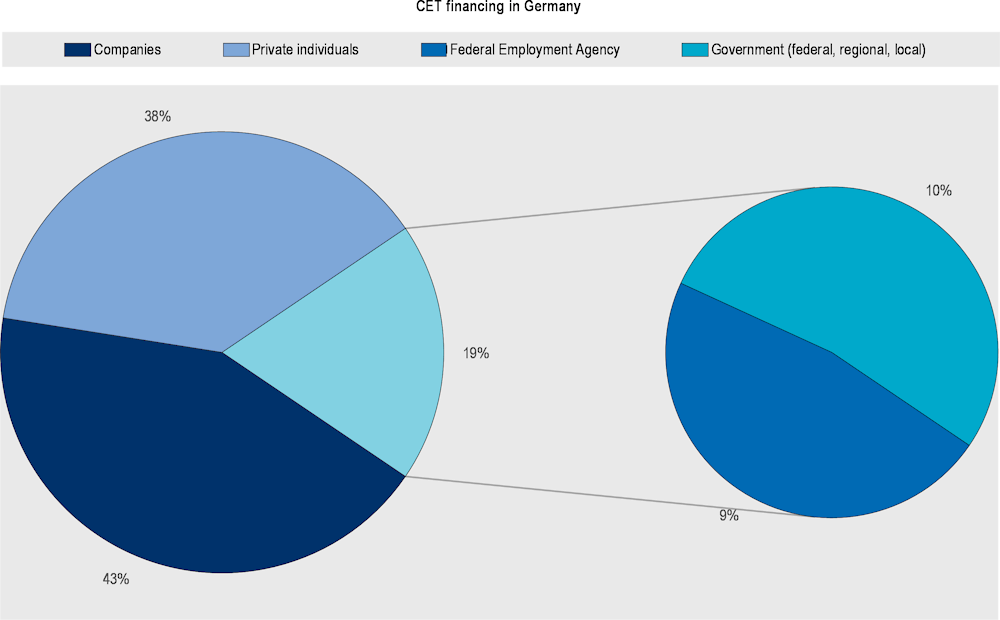

CET measures in Germany mostly receive funding from individuals and companies. Figure 4.6 shows funding of adult learning beyond initial education in Germany by different sources. In 2015 – the latest year for which a detailed funding breakdown is available – private individuals and companies were responsible for 38% and 43% of total funding respectively. Public funding accounted for the remaining 19%. The public funding comes from the BA and directly from the federal, regional and local governments in approximately equal parts. The BA is funded primarily through unemployment insurance contributions.

The CET landscape in Germany is characterised by a high degree of decentralisation. Individuals and enterprises are generally the main entities responsible for CET uptake and the provision of training. Within its governance structure, companies, the social and economic partners, CET providers and the government at national and federal state level are all involved in shaping CET offers and curricula (OECD, 2021[1]). On the one hand, such a decentralised system is widely recognised for achieving training provision that can be tailored to regional context. On the other hand, the coordination between different stakeholders that is required to make such a system efficient is a major challenge.

Figure 4.6. CET measures in Germany are mostly funded by individuals and companies

Note: 2015 is latest data available. The Federal Employment Agency is funded primarily through unemployment insurance contributions.

Source: Dohmen and Cordes (2019[12])

The main actors in continuous education and training in Berlin

Fundamentally, three different types of CET in Berlin can be distinguished by their respective target group. The first type is CET offered to the unemployed in the form of active labour market policies (ALMPs). The primary goal of these measures is to integrate the unemployed back into the labour market, thus ensuring that skills match those demanded on the labour market and unemployment spells do not become too long. The second type is CET offered to the employed to build on their existing skills. The primary objective of such CET is to improve the labour market position of participants and ensure their adaptation to changing job skill requirements. The third type is general adult education, which offers a broad set of education and training courses. It is open to anyone in the population, regardless of age or employment status. Its objective is not primarily labour market related.

Different actors within the Berlin CET landscape are responsible for delivering CET guidance and education and training depending on the target group. Similar to other German federal states, a range of actors are involved in the guidance and delivery of CET:

The Bundesagentur für Arbeit – Regionaldirektion Berlin-Brandenburg (“Regional Directorate of the Federal Employment Agency – Berlin-Brandenburg”; BA); The BA is the German Public Employment Service (PES) and primarily focusses on the implementation of active labour market policies targeting the unemployed. Main services include linking clients to jobs and vocational training, career counselling, employer counselling, supporting job-related education and training as well as supporting the labour market integration of people with disability. Recently, the BA has also adopted measures geared towards CET of the employed. The BA has 10 regional directorates, with the directorate for Berlin-Brandenburg responsible for Berlin.

The Senatsverwaltung für Integration, Arbeit und Soziales (“Berlin Senate Department for Integration, Labour and Social Affairs”; SenIAS); The SenIAS complements some measures offered by the BA through additional active labour market policies that target specific segments of both the employed and the unemployed.

The Job Centers, jointly managed by the BA and the SenIAS, provide job market guidance and training to unemployed who are social assistance (“Hartz 4”) recipients.

The Volkshochschulen (“Adult Education Centres”; VHS), coordinated by the Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugend und Familie (“Senate Department for Education, Youth and Family”; SenBJF); VHS offer general adult education open to anyone with courses generally not designed to support labour market prospects of participants.

The Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Berlin (“Berlin’s Agency for Civic Education”; LPBB); LPBB is a non-partisan institution to offer civic education under the supervision of SenBJF.

The Senatsverwaltung für Gesundheit, Pflege und Gleichstellung (“Senate Department for Health, Care and Equality”; SenGPG); SenGPG offers job-related CET guidance to women specifically.

Private sector companies; Private sector companies provide on-the-job training to employees at their own discretion.

Social partners; Social partners such as trade unions and employer organisations and economic partners such as Chambers of Commerce and Trade and Chambers of Skilled Crafts play a key role in consulting on legislative processes at the federal state level, shaping regulations on ALMPs and formal vocational CET, negotiating collective and company agreements that affect CET provision (OECD, 2021[1]).

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other social economy actors; NGOs and other social economy actors target specific vulnerable segments of the population and provide training and education services that foster societal and labour market integration.

On the ground, job-related CET and CET counselling financed by the BA, the Job Centers and the SenIAS is primarily delivered through certified private Bildungsträger (“CET providers”). A certification as a CET provider can be obtained through a fachkundige Stelle (“expert office”) listed in Germany's national accreditation body’s database. A certification is required for all measures funded by the BA, the Job Centers and the SenIAS and is generally valid for three years. Employers offering on-the-job training generally do no need to be certified.

A striking feature of Berlin’s CET landscape is the strict institutionalised distinction between job-related CET and general adult education. Work-related CET in Berlin is the joint responsibility of the BA Berlin-Brandenburg and SenIAS and delivered through certified CET providers. General adult learning is separated from these labour market related efforts. It is primarily delivered through the 12 VHS, which are institutions of the Berlin boroughs and are run and equipped by them at their own responsibility following the Berlin Schools Act (Section 123). The SenBJF performs regulatory tasks of citywide importance. This includes the regular publication of a comparative performance and quality development report and issuing of fee and remuneration regulations that are valid throughout Berlin’s VHS. The independence of the VHS mean that they have almost complete discretion over their curricula.

The recent passing of a new law on adult learning in Berlin has further cemented the VHS as an integral part of Berlin’s CET system. The law came into force in August 2021. It makes three major contributions to general adult education in Berlin: First, it provides legal safeguarding to the VHS and Berlin’s LPBB. Second, adult learning providers can apply for official recognition as adult learning providers and use their status to apply for government funding. Third, the visibility of adult learning will be increased through regular reports on adult education in Berlin and the establishment of an Erwachsenenbildungsbeirat (“Adult Learning Advisory Board”). The new law is described in more detail in Box 4.3.

While positive for general adult education, the law exemplifies the strong divide between general adult education and labour market specific training in Berlin. For example, as shown in Box 4.3, the advisory board includes only one member jointly appointed by the Industrie- und Handelskammer (“Chamber of Commerce and Industry”), the Berliner Handwerkskammer (“Chamber of Crafts Berlin”) or the Vereinigung der Unternehmensverbände in Berlin und Brandenburg (“Association of businesses in Berlin and Brandenburg”). Its membership is otherwise heavily skewed towards the representation of vulnerable minority groups. The link to Berlin’s labour market and wider local economy is almost entirely missing. Other OECD cities such as London do not distinguish between civic education and work-related education and training as strictly, but rather acknowledge that economic and societal objectives are intertwined. Box 4.4 describes London’s approach to adult learning in more detail.

Box 4.3. The new law on “adult learning in Berlin”

The new law on adult learning in Berlin was developed under the leadership of the SenBJF. It was passed in May 2021 and came into effect in August 2021. The law makes three major contributions to strengthening general adult education in Berlin.

First, the existing public adult education facilities in Berlin, the twelve local adult education centres (VHS) in Berlin and the Berlin Agency for Civic Education will be legally safeguarded. For the VHS, this means that important stipulations on course offers, equipment, digital infrastructure, quality standards for course instructors and participants are now legally enshrined. The Berlin Agency for Civic Education has a legal basis for the first time. Stable funding for education and training counselling is also part of the new law.

Second, any institution in Berlin that offers adult education can now apply for the status of a "recognized institution for adult education in Berlin". Such status then allows institutions and organisations to apply for newly created funding opportunities for important and innovative projects and programs. Funding is administered by the SenBJF.

Third, the law aims to improve public visibility of adult education through sparking public debate and advertisement of existing offers. An adult education advisory board will be set up for this purpose and a regular report on the status of adult education in Berlin will be published.

The new adult education advisory board brings together experts on adult education from different political, social, academic and business organisations, associations and institutions. Among its 31 board members, most are appointed due to their roles within the VHS system or are appointed directly and indirectly due to their political and administrative roles within Berlin’s adult learning landscape. A large number of seats on the board is also reserved for representatives of minority groups. For example, one member each is appointed by the State Advisory Council for Integration and Migration Issues, the State Advisory Council for People with Disabilities, the Women's Political Advisory Council and an organization representing the interests of lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender and intersex people. On the other hand, the advisory board includes only one member jointly appointed by the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Chamber of Crafts Berlin and the Association of Businesses in Berlin and Brandenburg. The Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund (“German Federation of Trade Unions”) also appoints only one board member under the current configuration.

Source: Senatsverwaltung für Bildung (2021[13]), Erwachsenenbildungsgesetz vom Parlament beschlossen: Historischer Tag für Lebenslanges Lernen in Berlin; EBiG, § 16 - § 18 Teil 6 - Berliner Erwachsenenbildungsbeirat („Berlin adult education advisory board“)

Box 4.4. Combining economic and societal objectives in adult learning in London, UK

Since 2019, the Greater London Authority (GLA) has been responsible for London’s annual £320m Adult Education Budget (AEB) and has since produced several skills strategies that aim to upskill and reskill London’s adult population. The Skills Roadmap for London is the latest skills strategy introduced by the Mayor of London in 2022. It has the main objective to “create a positive impact for Londoners in terms of both economic and social outcomes, including health and wellbeing” (Greater London Authority, 2022, p. 13[14]). The strategy will therefore be evaluated on key economic indicators such as improvements in London’s employment rates and income levels, but also on wellbeing measures that relate to Londoners’ life satisfaction. New survey data will be collected in London for this purpose.

While the key objective of London’s skills strategy is to support low-income individuals and households in moving into better jobs, the “no wrong door” approach lies at its centre: So-called Integration Hubs will ensure that different types of services collaborate and learning opportunities are provided independently of where individuals make first contact. These services include London’s PES and the UK’s National Career Service but also link support agencies working in health or services targeting disabled people and youth to adult learning opportunities.

The skills strategy in London encompasses both general adult education and adult learning focussed on better labour market integration. Adult learning services provided through the AEB cover a wide range of work-related training but also offer training in basic literacy, numeracy, digital and core employability skills. English language courses target London’s large migrant community.

Source: Greater London Authority (2022[14]), Skills Roadmap for London.

Different types of continuous education and training instruments are delivered by the national and the federal state government of Berlin

Four policy instruments to encourage CET participation can be distinguished: CET guidance, financial incentives for individuals, education and training leave and financial incentives for companies. The general idea of all measures is to increase CET participation of individuals for whom the (long-term) benefits of education and training is larger than the direct or indirect (short-term) cost. Depending on the barrier to participation individuals face, different instruments can be deployed. CET guidance is used to raise awareness of CET services and increase participation of individuals who either did not know about existing offers or were not able to navigate these offers on their own. Education and training leave improves the conditions for CET participation by removing work-related time constraints that hamper participation rates. Financial incentives loosen financial constraints of individuals or companies or incentivise participation of individuals who may be unaware of the benefits.

Guidance on education and training

A plethora of CET guidance providers exist in Berlin. Table 4.2 gives an overview of the different CET guidance offered in Berlin, listed by the actors involved and their respective target groups. The main guidance providers are the SenIAS in its Berliner Beratung zu Bildung und Beruf (“Berlin Guidance on Education and Profession network”; BBB) and the BA’s Lebensbegleitende Berufsberatung im Erwerbsleben (“Lifelong Vocational Guidance for adults in employment”; LBBiE). Smaller-scale guidance offers exist, with some complementing existing services offered by the main providers (IQ-Netzwerk, Grundbildungszentrum Berlin) and some existing for historical reasons (Berufsperspektiven für Frauen). CET guidance offers in the Berlin’s VHS also exist, but are currently limited in scope, an observation discussed in more detail in section 3.2. The BA and the Job Centers also provide CET guidance to the unemployed specifically.

The CET guidance offered by the BA is open to all individuals, while SenIAS also targets some population groups specifically. The SenIAS operates a network of counselling centres. The network consists of seven career guidance centres that are open to all individuals and three more specialised centres. The specialised centres target individuals seeking further formal education (Fachberatung berufliche Qualifizierung), SMEs (Qualifizierungsberatung in KMU), migrants seeking language training (Erfolg mit Sprache und Abschluss) and refugees seeking general career guidance (Mobile Beratung zu Bildung und Beruf für geflüchtete Menschen; MoBiBe). Geographically, the counselling centres are spread out evenly across Berlin’s boroughs (OECD, 2022[15]).

Table 4.2. CET guidance in Berlin

Overview of CET guidance offered in Berlin by provider and target group

|

Original name |

English name |

Actors involved (incl. funders) |

Target group |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Berliner Beratung zu Bildung und Beruf, BBB |

Berlin Guidance on Education and Profession network |

Senate Department for Integration, Labour and Social Affairs, SenIAS |

All individuals |

|

Fachberatung berufliche Qualifizierung, FbQu |

Vocational qualification counselling |

SANQ e. V. |

Individuals seeking a formal diploma via partial qualifications |

|

Erfolg mit Sprache und Abschluss, EMSA |

Success with language and qualification |

Arbeit und Bildung e. V. |

Migrants |

|

Qualifizierungsberatung in KMU |

Qualification guidance for SMEs |

GesBiT mbH |

SMEs |

|

Mobile Beratung zu Bildung und Beruf für geflüchtete Menschen, MoBiBe |

Mobile counselling on education and careers for refugees |

KOBRA (Berliner Frauenbund 1945 e.V.), Senate Department for Health, Care and Equality |

Refugees |

|

Lebensbegleitende Berufsberatung im Erwerbsleben, LBBiE |

Lifelong Vocational Guidance for adults in employment |

BA |

All individuals |

|

Volkshochschulen, VHS |

Network of adult education centres |

VHS |

All individuals |

|

IQ-Netzwerk |

IQ-Network |

BMAS, ESF, BAMF, BMBF, BA |

Migrants |

|

Berufsperspektiven für Frauen |

Guidance network Career Progression for Women |

Senate Department for Health, Care and Equality |

Women |

|

Grund-Bildungs-Zentrum Berlin, GBZ |

Centre for Basic Education |

Senate Department for Integration, Labour and Social Affairs, VHS |

Low-qualified adults |

Source: OECD (2022[15]).

All centres offer a wide range of CET guidance services, with some overlap between the services provided by the SenIAS and the BA. These services include counselling on formal education and training, professional (re-)orientation, CV writing, access to employment, career development, application procedures, CET while employed, learning strategies and sources of CET funding. Additional in-house services include the mapping of skills and formal education, the provision of a computer to facilitate the browsing of online databases, and support with the administrative steps in applications for jobs and education measures (OECD, 2022[15]). While both the SenIAS and the BA offer comprehensive CET guidance services, navigating through different very similar offers may not always be straightforward and could potentially discourage some individuals.

An overview of adult learning and CET offers is available online through national databases such as Kursnet (“Course net”). Kursnet is the BA’s main nationwide online platform that functions as a search tool for CET offers. Other nationwide online tools hosted by the BA include Karriere und Weiterbildung (“Career and CET”), Erkundungstool Check-U (“Exploratory Tool Check-U”), Berufsentwicklungsnavigator (“Career Development Navigator”), berufe.tv (“jobs.tv”) , berufsfeld-info.de (“Occupational Field Info”), Typisch ich (“Typical Me”) and Lernbörse (“Learning Bourse”). Different websites target different segments of the population, such as young people, people interested in vocational training and occupations, employed individuals who want to advance their skills and the general public (OECD, 2021[1]).

The SenIAS also operates the Berlin-specific Berliner Weiterbildungsdatenbank (“CET Database Berlin”; WDB). The database includes around 40 000 entries from approximately 1 100 adult education providers. It is updated daily. Its interface is easy to operate and only requires users to enter their postcode and the CET field in which they are interested. Users can also limit the geographical search distance to display offers in their vicinity. WDB’s main focus is on professional development courses but it also includes a wide range of courses offered by the VHS on topics related to civil society, politics and culture. A cooperation exists between the WDB and the Brandenburg-specific similar database Weiterbildung Brandenburg (“Further education in Brandenburg”). In the main WDB search portal, the offers of both databases are displayed. WDB also offers generic links to general CET funding options for each course in the database. However, to increase take-up of these financial instruments, displayed funding options could be tailored to individual needs more precisely and links to required documents could be provided.

The WDB also offers further in-built services for companies and adult education providers but could. Companies can use WDB’s interactive instruments to analyse the need for qualification within their own establishment. They can also send inquiries to adult learning providers to find suitable offers. Information on CET funding opportunities for companies are also available within WDB. However, feedback from social partners gathered by the OECD for the purposes of this report also revealed that employers often find it difficult to navigate the WDB. Future updates of the database could specifically address employers on the WDB’s home page. Adult learning providers primarily use the platform to publish their offers, which they can then also cross-post in other CET databases such as the nationwide Kursnet.

Financial incentives for individuals

Financial incentives for individuals can take different forms but generally aim to remove financial constraints that hamper CET participation. The main forms of financial incentives offered to individuals are education allowances, loans at preferential rates, CET premiums, scholarships, CET subsidies, tax incentives and education vouchers (OECD, 2021[1]).

In 2020, the German federal government offered 10 such financial incentive schemes. The different programmes funded by the German federal government are summarised in Table 4.3. On the highest level, these can be distinguished by the type of policy instrument, their respective target group and the scope of the measure. Target groups are often narrowly defined and eligibility depends on a range of socio-economic characteristics such as the level of education, age, employment status and income. The scope of the measure refers to the type of training the programme supports.

Table 4.3. Different types of financial incentive schemes offered by the German federal government

|

Programme name |

English translation |

Type of instrument |

Target group |

Scope of CET |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aufwendungen für die Aus- und Fortbildung |

CET expenses |

Tax incentive |

Tax payers participating in CET |

Job-related training |

|

Bildungskredit |

Education loan |

Loan |

18-35 year olds |

Vocational and higher CET, internships |

|

Aktivierungs und Vermittlungsgutschein |

Activation and counselling voucher |

Voucher |

Courses of occupational inclusion and activation |

Job-related training |

|

Bildungsgutschein |

Education voucher |

Voucher |

Unemployed, persons threatened by unemployment or low educated |

Jon-related training |

|

Bildungsprämie |

Education grant |

Voucher |

Low-income workers |

Job-related specialist courses, interdisciplinary trainings (non-formal) |

|

Aufstiegs-BAföG |

Upgrading training assistance |

Allowance |

Adults with a IVET degree |

Formal CET |

|

Zukunftsstarter |

Future starter |

Allowance |

25-35 year olds without IVET degree and/or in low-skilled jobs |

IVET |

|

Aufstiegsstipendium |

Advancement stipend |

Scholarship |

Adults with initial vocational qualification and work experience |

Academic studies |

|

Weiterbildungsstipendium |

CET stipend |

Scholarship |

Graduates of initial vocational training; <25 years old |

Specialist courses, interdisciplinary training, higher education courses |

|

Weiterbildungsprämie |

CET premium |

Premium |

Unemployed individuals |

Formal CET courses of >2 years |

Source: Summary table based on (OECD, 2021[1])

The wide range of financial incentive instruments allows for targeting specific segments of the population but bears risks of low take-up. The first potential issue is that individuals may find it hard to navigate through the different offers and are unlikely to be aware of all the different funding options. The second risk pertains to the narrowly defined target groups and type of CET covered. Without an overarching framework, such specific targeting may lead to some individuals “falling through the cracks”. For example, earlier OECD work notes that individuals who find their skills and qualifications to become less relevant in the labour market do not have options to upgrade their skills on their own initiative but have to rely on government measures targeted at employers (OECD, 2021[1]). Box 4.6 describes the two new laws that govern these financial support options for employers – the Qualifizierungschancengesetz (Skills Development Opportunities Act”) and the Arbeit-von-morgen-Gesetz (“Work of Tomorrow Act”) – in detail.

The German federal states further complement these financial incentives according to regional needs, but Berlin did not offer additional financial incentives to individuals before the COVID-19 pandemic started. In 2019, 10 out of 16 German federal states offered additional vouchers covering direct costs for job-related CET. The target group of these additional offers were mostly low-educated and low-income individuals, as well as employees and owners of small and micro enterprises (OECD, 2021[1]). However, some measures also target the development of specific skills. One example includes the “Bavarian education cheque”, a programme that ran until July 2021. It was supported by the European Social Fund and paid EUR 500 to employees who aimed to develop their digital skills in training courses that last a minimum of 8 hours (Bayerischen Staatsministeriums für Familie, 2021[16]). In addition to education vouchers, 8 out of 16 federal states offered CET premiums for formal vocational upskilling qualifications in 2019 (OECD, 2021[1]).

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Berlin’s SenIAS introduced a CET premium for workers who were forced to reduce their working hours during the pandemic. Like other OECD countries, Germany introduced a job retention scheme in the form of short-time work (Kurzarbeit) to contain the employment fallout caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since March 2020, firms can request financial support from the federal government if 10% of their workforce are affected by cuts in working hours. Public employment services reimburse employers for these reductions in working hours while employees continue to receive parts of their salaries for hours they do not work (OECD, 2021[17]). To encourage uptake of education and training among affected employees, the SenIAS introduced an additional premium. Employees working reduced hours receive EUR 250 monthly if they participate in education or training measures every day of the month. Longer or shorter training courses are supported proportionally against this benchmark. Only courses offered by the BA Berlin-Brandenburg are eligible for support (Senatsverwaltung für Integration Arbeit und Soziales, 2021[18]).

Due to the high share of own-account workers in Berlin compared to other German regions and cities, they present a natural target group for city-level initiatives. As detailed above, both the share of self-employed in total employment and the share of own-account workers among the self-employed are higher in Berlin than in other German cities and regions. Across the OECD, CET among own-account workers are supported through five main instruments: Tax deductions, subsidies, financial incentives, wage replacement schemes and employment insurance plans (OECD, 2019[11]).Box 4.5 provides an example from Vienna, Austria, where training is financed for some own-account workers.

Box 4.5. The Waff training account – education and training options for own-account workers in Vienna, Austria

While support schemes are typically implemented by national governments, some city-level initiatives exist that also target own-account workers. In Vienna, Austria, the Waff Training Account provides training grants to certain own-account workers who have their business license or their main residence in Vienna, are in possession of a valid trade license, are insured under the Commercial Social Security Act and do not employ any employees.

Waff funds training and further education aimed at expanding entrepreneurial skills and training to improve commercial and business skills. The latter include courses in the areas of accounting, controlling, office organization or time management. Courses to acquire and improve digital skills are also funded. These include courses in the areas of social media, Photoshop, ICDL or e-billing. Finally, Waff also funds language courses such as business English or business German. Formal education that leads to degrees is not covered.

Waff covers 80% of the total training costs, up to a maximum of EUR 2 000. There is no limit on the number of courses that can be attended until the maximum coverage is reached. To ease facilitation, applications can be submitted before the training course begins up until four weeks after the start date of the course.

Source: OECD (2019[11]), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work; Waff (2021[19]), Weiterbildungsförderung für Ein-Personen-Unternehmen (EPU).

Educational leave law

The educational leave law in Berlin is generous compared to other German federal states. Educational leave laws are a competence of the German federal states and allow employees to take leave from work for educational purposes. All but two federal states have such educational leave laws. Table 4.4 shows the generosity of these measures by German federal states. Most states offer employees five days of educational leave per year. Berlin’s model of offering 10 days per two years adds some flexibility to the generic model. Under the law, educational leave is granted for job-related training and political education. Political education is understood as a broad term that covers general adult education on broader societal issues.

Table 4.4. The generosity of educational leave laws across German federal states

|

Federal State |

Educational leave law |

Paid leave |

Reimbursement of wages for employers |

Duration of leave |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Baden-Württemberg |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

5 days per year, cannot be cumulated |

|

Bayern |

No |

– |

– |

– |

|

Berlin |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

10 days per 2 years |

|

Brandenburg |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

10 days per 2 years; accumulation of leave entitlements possible based on written agreement between employer and employee |

|

Bremen |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

10 days per 2 years |

|

Hamburg |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

10 days per 2 years |

|

Hessen |

Yes |

Yes |

Enterprises with <20 employees can request wage subsidy of 50% for job-related CET and civic education; all enterprises can request 100% wage subsidy for training courses for the purpose of voluntary work (Ehrenamt) |

5 days per year, can be cumulated over two years |

|

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern |

Yes |

Yes |

Enterprises can request EUR 55-110 wage subsidy per day |

5 days per year, cannot be cumulated |

|

Niedersachsen |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

5 days per year, can be cumulated over 4 years |

|

Nordrhein-Westfalen |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

5 days per year, can be cumulated over 2 years |

|

Rheinland-Pfalz |

Yes |

Yes |

Enterprises with <50 employees can request wage subsidy of 50% of average salary in the Federal State |

10 days per 2 years |

|

Saarland |

Yes |

Yes |

2 days + 4 half days per year |

|

|

Sachsen |

No |

– |

– |

– |

|

Schleswig-Holstein |

Yes |

Yes |

5 days per year, can be cumulated over 2 years |

|

|

Sachsen-Anhalt |

Yes |

Yes |

5 days per year, can be cumulated over 2 years |

|

|

Thüringen |

Yes |

Yes |

5 days per year, can be cumulated over two years if rejected |

Note: The new Berliner Bildungszeitgesetz (“Berlin educational leave law”) came into effect on September 1, 2021.

Source: Overview for federal states based on (OECD, 2021, p. 129[1]) with additions from Berliner Bildungszeitgesetz (BiZeitG; “Berlin educational leave law”, version July 5, 2021).

Participation in educational leave remains relatively low in Berlin, but a slight upward trend is visible over the past decade. In 2018, the latest year for which complete data is available, 16 520 employees in Berlin took educational leave. This corresponds to approximately 1% of the underlying eligible population. In absolute terms, the number of educational leave takers thus increased significantly compared to the year 2010, when 9 834 took advantage of this measure. However, as the size of the labour force also grew over the same time period, the relative number of participants only increased marginally (Figure 4.7).

The vast majority of employees taking educational leave did so to pursue work-related training. In 2018, 85% of educational leave takers pursued work-related training. Around 10% took time off work to take courses on political education. Another 5% of educational leave takers engaged in a combination of both types of CET.

Figure 4.7. The total number of educational leave takers in Berlin is growing slowly over the years

Note: Data on the share of educational leave takers not yet available for years following 2017.

* Data reporting for the year 2019 is incomplete and likely to be revised upward.

Source: OECD illustration based on data provided by SenIAS.

Women in Berlin are more likely to take educational leave than men. The data shown in Figure 4.7 can be further disaggregated by gender and the level of education. In 2018, 57% of educational leave takers were female, a continuation of a historical trend. Since 1991, women constituted more than 50% of educational leave takers in every recorded year.

Individuals without professional qualification constitute a negligible share of educational leave takers. Only 7% of employees taking time off work for educational purposes did not hold any professional qualification. EU-LFS data shows that the share of Berlin’s labour force without professional qualification (a level of education below upper secondary education) among 25 to 64 year olds stood at 12.9% in 2018. Thus, low-educated individuals are underrepresented among those who take educational leave, even though they are among the groups to benefit the most from additional training or education.

Financial incentives for companies

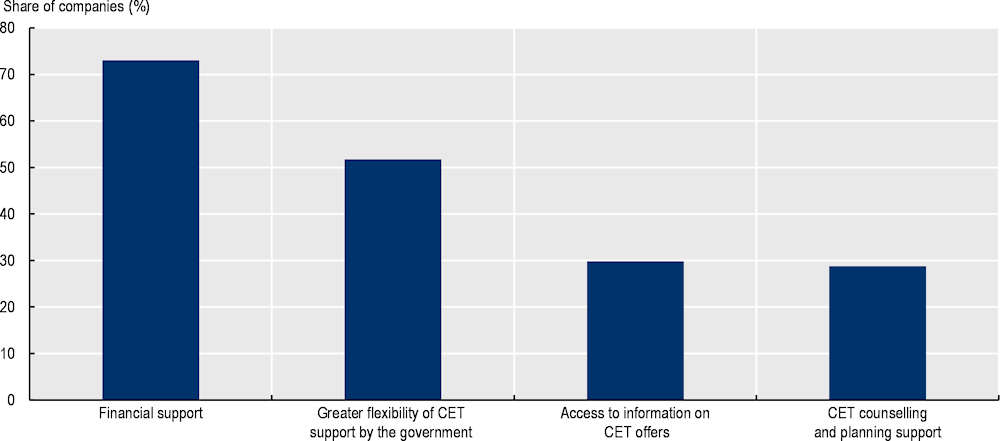

Companies in Berlin stress the importance of financial incentives for expanding their CET offers. Figure 4.8 shows that 73% of Berlin-based companies surveyed by the IHK respond that financial support would be the most useful type of support to help them expand their in-house CET. 52% of companies state that greater flexibility of financial support by the government would be helpful. Access to information on CET offers and support in CET planning are further reasons mentioned by 30% and 29% of surveyed companies respectively.

The German federal government does offer generous financial incentives to increase CET in small companies. The German federal government has recently passed two new laws, the Qualifizierungschancengesetz (“Skills Development Opportunities Act”) and the Arbeit-von-morgen-Gesetz (“Work of Tomorrow Act”) that support companies in their efforts to offer CET to employees. The amount of the subsidy depends on a range of parameters such as the size of the company, the share of workers within the company who require training, the type of CET offered and the education level and work experience of participants. Very small companies can get up to 100% of their incurred direct and indirect cost reimbursed. Box 4.6 describes these laws in more detail.

Figure 4.8. Enterprises in Berlin declare financial support the main type of support needed to expand CET within the company

Note: Based on a sample of 560 companies.

Source: Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Berlin (IHK Berlin), Sommerumfrage 2021 (“summer survey 2021”).

Unlike other federal states, Berlin does not offer additional financial incentives to companies to improve CET participation. In Germany, 13 out of 16 federal states complement the instruments provided by the federal government (OECD, 2021[1]). Some of these measures predate the new instruments laid out in the Skills Development Opportunities Act and the Work of Tomorrow Act and are therefore likely to be phased out. However, some of these complementary initiatives fill important gaps: For example, federal states generally support education and training opportunities without any lower limit on their duration. Therefore, they add some flexibility to measures funded under the countrywide Skills Development Opportunities Act and the Work of Tomorrow Act, where the minimum course duration is three weeks to be eligible for funding. Measures on the federal state level are often co-funded by the European Social Fund (ESF) (OECD, 2021[1]).

Box 4.6. Germany has recently introduced two new laws that strengthen financial support for training and education measures offered by SMEs

Skills Development Opportunities Act

The Qualifizierungschancengesetz (“Skills Development Opportunities Act”) came into effect in January 2019. It is part of the German national training strategy and replaces the 2006-2019 WeGebAU Programme, under which subsidies were granted to SMEs. The WeGebAU Programme specifically targeted older workers and adults with low levels of education. The primary aim of the new Skills Development Opportunities Act is to widen access to subsidised training opportunities for all workers if these are affected by structural change or work in professions characterised by a shortage of skilled workers (Engpassberuf). Under the new law, CET measures can be subsidised if the training lasts for at least four weeks and the participating worker has at least three years of work experience.

The amount of the subsidy depends on the size of the company, the share of workers within the company who require training, the type of CET offered and the education level and work experience of participants. Both part-time and full-time training options are supported as long as the minimum training duration is met.

Direct training costs of CET offered within SMEs with fewer than 10 employees, training for workers above the age of 45 and training for low-educated workers are fully covered. Large companies of more than 2500 employees can only claim up to 20% of the training costs, reflecting their higher ability and willingness to offer training in-house.

Indirect training costs, i.e. wage costs accruing to the employer while workers are undergoing training measures, are also covered. Cost coverage rates again depend on a range of parameters similar to those of the direct training costs. In SMEs with fewer than 10 employees, between 75% (the baseline) and 100% of wage costs can be claimed, depending on the education level of the participating employee. In larger SMEs up to 250 employees, between 50% (the baseline) and 100% of the wage costs are covered, depending on the education level of the participating employee.

Work of Tomorrow Act

The Arbeit-von-morgen-Gesetz (“Work of Tomorrow Act”) builds on the Skills Development Opportunities Act and expands on some details. The law came into effect in October 2020. It increases some of the subsidies offered to companies that are affected by structural change. Most importantly, it reduces the minimum duration of training measures eligible for subsidies from four to three weeks. It also increases funding for training by ten percentage points if at least every fifth employee in a company needs further training. For SMEs that employ more than 10 and fewer than 250 employees the ten percentage point increase only requires 10% of employees to be in need for training.

Source: OECD (2021[1]), Continuing Education and Training in Germany.

However, early data for the whole of Germany shows that the take-up of these new measures remains low, in particular among the smallest SMEs. A survey conducted by the BA in October/November 2020 suggests that only one in ten German companies make use of the new financial instruments that aim to support CET. Among surveyed companies that employ fewer than 10 employees, only 26% were aware of the new instruments, compared to 67% of companies that employ more than 250 employees. Only 6% of the smallest companies had made use of the financial support measures, compared to 35% among large companies. Companies that employ between 11 and 250 employees fell in between these extremes on both metrics (Institute for Employment Research, 2021[20]).

Employers name five reasons for the low-take up of financial support to increase CET offers. Fifty-three percent of German companies that were aware of the CET financial support options but did not make use of them responded not having found suitable CET courses and programmes for their employees. 37% responded that the administrative burden was too high, 34% responded refused to engage with the BA, 30% of the surveyed companies responded that their employees were not interested in CET and 27% responded that the minimum duration to become eligible for financial support was too long (Institute for Employment Research, 2021[20]). Taken together, a lack of awareness among small employers in particular and the lack of (human) resources to navigate through offers appear to be the major bottlenecks that hamper take-up.

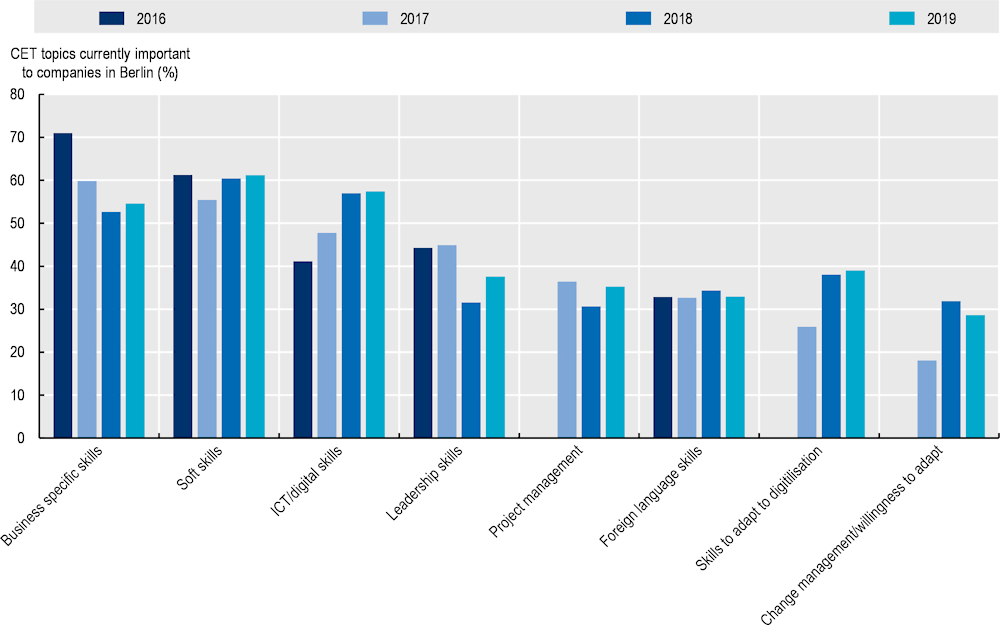

Despite the low take-up of financial support measures, employers in Berlin continue to attach importance to CET, with a rising need for digital skill development. Figure 4.9 shows that the overall importance of CET for employers has approximately stayed constant. However, some CET content have gained importance among employers, while the development of some other skills has become less relevant. For example, the share of employers that named digital skills and the ability to adapt to digitalisation has increased by 16 and 13 percentage points respectively between 2016 (2017) and 2019. On the other hand, the share of employers that named business specific skills as a particular important CET topic dropped by 16 percentage points over the same period. The development of other skills, such as project management and the ability to speak foreign languages, has stayed constant. Taken together, the findings imply that Berlin’s employers acknowledge the increasing importance of skills that allow employees to adapt to a changing labour market.

Figure 4.9. Employers in Berlin increasingly attach importance to digital skills training

Note: Sample size differs between years. N(2016)=436; N(2017)=480; N(2018)=335; N(2019)=223.

Source: Chamber of Commerce and Industry (IHK) Berlin - Education and Further Education survey

To engage Berlin’s SMEs in local skill development, innovative solutions are needed. The analysis in this chapter suggests that financial support is important but by itself often insufficient to increase training and education offers in SMEs. At the same time, the need for updating and upgrading employees’ skills within SMEs according to structural labour market changes is evident. Other cities across the OECD have therefore started to acknowledge the need to go beyond financial incentives. For example, the city of Vantaa, Finland, has started to contact SMEs proactively. Training programmes are then developed jointly with SMEs. Box 4.7 describes the approach taken by the city of Vantaa in more detail.

Box 4.7. Supporting growth and social investments in SMEs through skill development in Vantaa, Finland

The city of Vantaa, the fourth biggest city of Finland, has identified the need to develop a new model to support education and training in SMEs.

The Urban Growth Vantaa project brings together relevant city departments, education providers, research institutes and businesses in Vantaa to develop a local jobs and skills ecosystem with the aim to support both local SMEs and their employees in employment, upskilling and digitalization. The primary target group of the initiatives are low-educated adults employed by SMEs who do not traditionally fall into the category of continuous learners. This specific group is often at risk of job loss due to the automation of production processes. A second target group are executives of SMEs who aim to grow their company responsibly.

Employees in SMEs are typically supported through a co-created apprenticeship services programme. These apprenticeships are targeted at individuals as an opportunity to earn a vocational degree. Urban Growth Vantaa’s solution is to contact companies to introduce training ideas and their benefits to SME decision makers and employees simultaneously. In a first step, SMEs with 10-200 employees are contacted by the project coordinators. SMEs then undergo a needs assessment to identify skill needs through surveys. SMEs are then informed of the different CET options that could develop these relevant skills. A discussion with the individual employees then follows and an appropriate apprenticeship is identified for them. The apprenticeships are free of charge for employees and SME continue to pay their full salaries. If the reduction in working hours at full salary cannot be borne by SMEs, financial support schemes exist.

Alternatively, employees of SMEs can be trained in a so-called growth-coaching programme. The programme follows a similar structure but takes a forward-looking approach. Business development needs are identified in consultation with SME executives and employees then undergo the appropriate training to meet these needs.

The Urban Growth Vantaa project further acknowledges resource constraints faced by SMEs and introduces the idea of a “one-stop-shop”. To this end, the project assigns a project account manager to each SME who coordinates CET efforts with a company representative.

The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) granted approximately EUR 4 million in funding for the project. The project has thus far reached 70 SMEs and provided training or support to 714 adults. It initially runs from January 2019 to April 2022.

Source: Urban Innovative Actions Initiative (2021[21]), Urban Growth-GSIP Vantaa - Growth and Social investment Pacts for Local Companies in the City of Vantaa.