This chapter looks at the Slovak Republic's existing framework to ensure integrity and transparency in public decision-making processes, and assesses the framework's resilience with respect to the risk of capture of public policies by special interests. In particular, this chapter identifies measures the Slovak Republic could adopt to strengthen access to information for all stakeholders, as well as stakeholder engagement in policy making. This chapter also explores how to strengthen the legislative framework with respect to lobbying, and identifies measures to raise awareness about integrity standards on lobbying for government officials and lobbyists more broadly.

OECD Integrity Review of the Slovak Republic

5. Strengthening transparency and integrity in decision making in the Slovak Republic

Abstract

Introduction

Public policies determine to a large extent the prosperity and well-being of citizens and societies. They are also the main ‘product’ people receive, observe, and evaluate from their governments. While these policies should reflect the public interest, governments also need to acknowledge the existence of diverse interest groups, and consider the costs and benefits for these groups. In practice, a variety of private interests aim at influencing public policies in their favour. It is this variety of interests that allows policy makers to learn about options and trade-offs, and ultimately decide on the best course of action on any given policy issue. Such an inclusive policy-making process leads to more informed and ultimately better policies.

However, experience has shown that policy making is not always inclusive and at times may only consider the interests of a few, usually those that are more financially and politically powerful. Experience has also shown that lobbying and other practices to influence governments may be abused through the provision of biased or deceitful evidence or data, and the manipulation of public opinion (OECD, 2021[1]). Public policies that are misinformed and respond only to the needs of a specific interest group indeed result in suboptimal policy effectiveness.

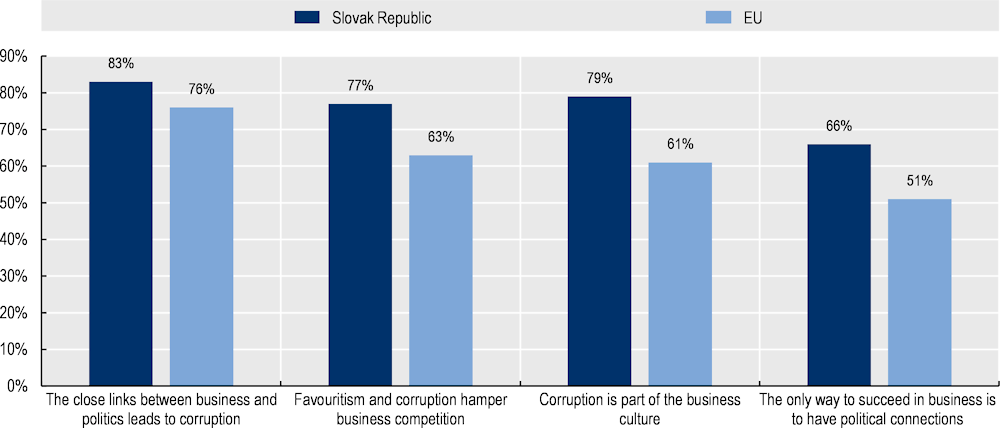

The perception of undue influence and an opaque relationship between public and private sectors is significant in the Slovak Republic. According to the latest 2020 Eurobarometer Survey, more than four out of five respondents in the Slovak Republic (83%) consider that too close links between business and politics in their country lead to corruption, and 66% of respondents believe that the only way to succeed in business is to have political connections (see Figure 5.1). In all these categories, the Slovak respondents are above the EU average, meaning that Slovaks have higher levels of perceived corruption when doing business in the Slovak Republic.

Figure 5.1. Slovaks perceive that close ties between business and politics lead to corruption

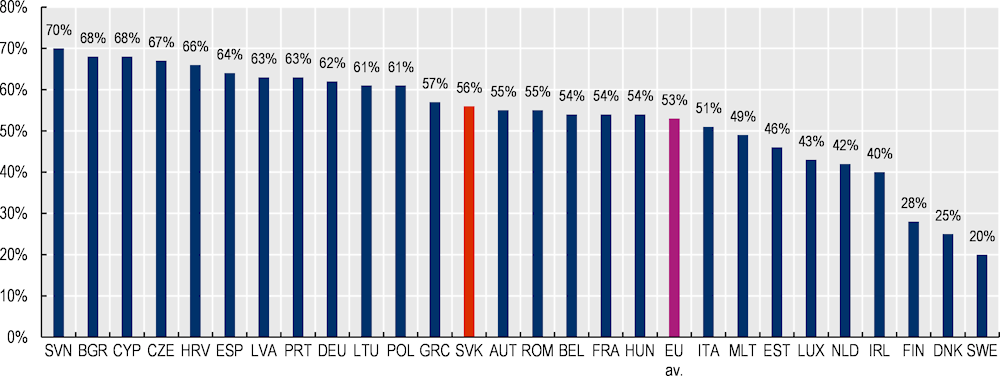

Similarly, the most recent Corruption Barometer for the European Union reveals that 27% of the people in the Slovak Republic think their government does not take their views into account when making decisions (48% at the EU level), and 56% of them think that their government is run by private interests (53% in 19 EU Member states) (see Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2. A majority of Slovaks perceive that the government is controlled by private interests

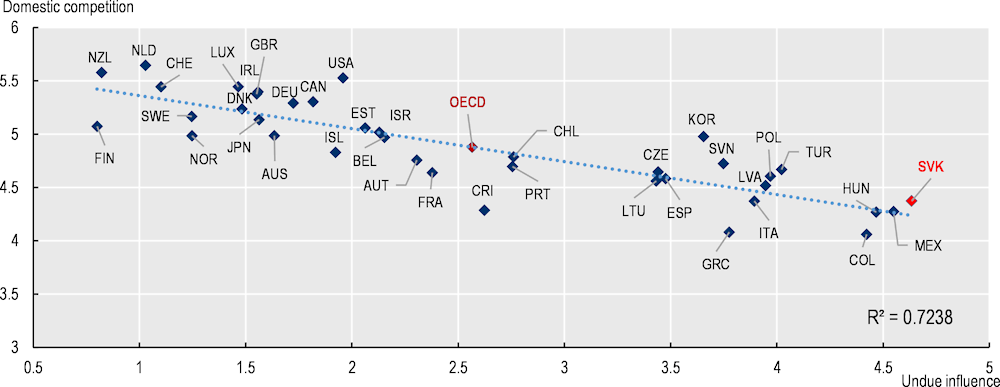

Influencing the policy‑making process by only promoting special interests can have widespread impact and consequences across sectors and the economy as a whole (OECD, 2017[3]). It also implies a misallocation of private resources: activities such as financing political campaigns and parties or investing into lobbying activities are favoured at the cost of investments into product, process or business model innovations, affecting both allocative and productive efficiency and thus growth potential. Studies increasingly show that lobbying and other influence practices conducted without transparency and integrity, and without the involvement of a broad group of stakeholders may either result in abandoning the necessary regulations needed to correct market distortions, or may lead to excessive regulation to protect incumbent elites, resulting in reduced competition and less economic growth. Data from the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018 indeed shows that the Slovak Republic seems to be on average more vulnerable to undue influence than other OECD countries, and exhibits lower levels of perceived domestic competition (see Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3. Strong correlation between high undue influence and low competition

Note: A value of 0 is “low” and a value of 6, “high”. The scores for the “undue influence” indicator have been inverted to reflect that higher scores mean higher levels of undue influence. The World Economic Forum calculates the indicator based on the responses to two questions, relating to judicial independence (“In your country, to what extent is the judiciary independent from influences of members of government, citizens, or firms?”) and favouritism (“In your country, to what extent do government officials show favouritism to well-connected firms and individuals when deciding upon policies and contracts?”).

Source: World Economic Forum (2017).

The Slovak Anti-Corruption Policy 2019-2023 has recognised the risks related to undue influence in the policy‑making process and lobbying. In response to these risks, the ACP identifies as priority number 2 to “Improve the quality of the legislative and regulatory environment” and as objectives to:

“improve the transparency and predictability of the legislative process”

“prevent the capture of the legislative process and regulatory capture by narrow interest groups who pursue their own interest to the detriment of the public interest”

“establish an effective legal framework for regulating lobbying”.

Furthermore, under priority 3 “improve conditions for entrepreneurship”, the ACP stipulates as objective to “strengthen the credibility, transparency and predictability of legal and economic relations between business entities and the State.”

This ambitious agenda demonstrates both the commitment of the Government of the Slovak Republic and the complexity of the issue of curbing undue influence, with multiple stakeholders involved (National Council of the Slovak Republic, public administrations, government, business representatives, advisory bodies, civil society organisations) and multiple dimensions (legislative process, access to information, integrity of public sector employees, political party financing, etc.). Given this complexity, one single policy measure will not be sufficient, and a multifaceted approach will be needed, addressing various dimensions of a broader public integrity system and involving multiple stakeholders. At the same time, the fact-finding meetings have highlighted that the term lobbying has a strong negative connotation in the Slovak Republic, despite that, as argued above, it is part of the policy‑making process. In light of all the above, this multifaceted approach could therefore include the following key elements:

improving access to information

improving stakeholder engagement in the policy‑making process

fostering integrity and transparency in lobbying

awareness raising and stakeholder consultation on lobbying

improving the diversity and transparency in expert groups and advisory bodies

strengthening integrity standards for public sector employees

providing guidelines for lobbyists

improving transparency in the funding sources of civil society organisations

strengthening the framework for political party financing.

A number of these elements have been addressed in previous chapters of this review and only those that have not been covered will be assessed here. The issue of policy party financing falls outside the scope of this review.

Strengthening access to information to increase the oversight role of stakeholders

Access to information (ATI) is the right of the people to know. It is understood as the ability for an individual to seek, receive, impart, and use information effectively. ATI is a necessary precondition for accountability and democracy as it enables citizens and stakeholders, including CSOs, to exercise their voice and contribute to setting priorities, and have an informed dialogue about – and participate in – decisions that affect their lives. Furthermore, access to information plays an instrumental role in facilitating both transparency and accountability. It helps citizens and stakeholders to obtain information to fulfil their role as watchdogs over the proper functioning of government institutions. For these reasons, the citizens' right to know and the legal provisions to access information are significant instruments for combating corruption and for creating a change in culture in the public sector.

The Slovak Republic could consider reviewing the Act on Access to Information to increase its effectiveness

An effective legal framework that clarifies how right to information will be realised is the foundation for a strong access to information system. Core provisions of ATI laws include: the scope, the provisions for proactive and reactive disclosure, the exemptions and denials to grant information to the public, the possibility to file appeals, and the institutional responsibilities for oversight and implementation.

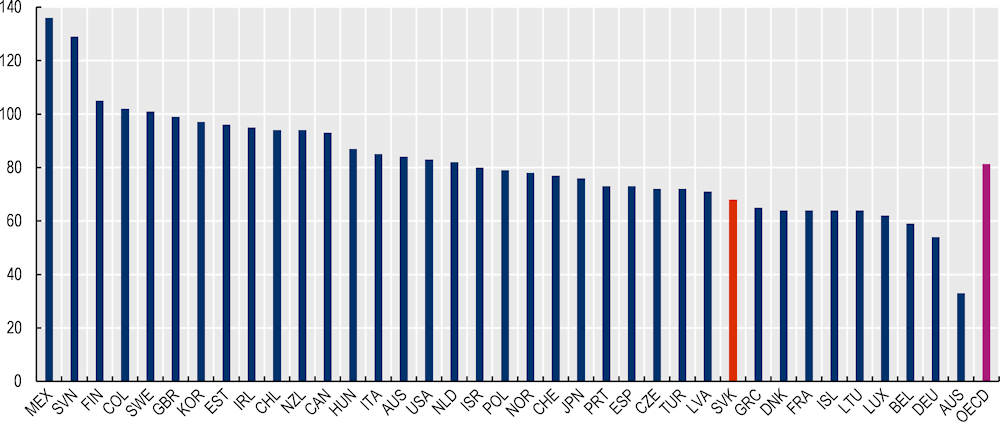

In the Slovak Republic, the right to information is enshrined in the constitution.1 In 2000, the Slovak Republic adopted Act No. 211/2000 Coll. on Free Access to Information and on amendments of certain acts (hereinafter “access to information Act”).2 The Act establishes the provisions to enforce the right to access to information (ATI) provided in the Constitution. However, according to the Right to Information Rating (RTI) the legal quality of the Slovak Republic’s ATI Act is lower than the OECD average of 81 (see Figure 5.4) (RTI Rating, n.d.[4]).3 In particular, several key elements are missing from the current Act, including coverage to all relevant actors, establishing an oversight body, and inclusion of public interest and harm tests. The Ministry of Justice, the current Government Manifesto (for years 2021 – 2024) also comprises government´s commitment to improve the enforcement of the right to information. The Ministry of Justice is preparing an amendment to address among others the enlargement of the scope. The Slovak Republic could continue to move forward with the amendment of the ATI Act and to carry out an inclusive process that ensures that public and private stakeholders’ views and needs are taken into account in the amended act.

Figure 5.4. In terms of its legal framework, the Slovak Republic’s Access to Information Act is below of the OECD average

Note: The maximum achievable composite score is 150 and reflects a strong RTI legal framework. The global rating of RTI laws is composed of 61 indicators measuring seven dimensions: Right of access; Scope; Requesting procedures; Exceptions and refusals; Appeals; Sanctions and protection; and Promotional measures.

Source: Access Info Europe (AIE) and the Centre for Law and Democracy (CLD), Right to Information Rating, https://www.rti-rating.org/

In terms of scope, the ATI Act covers all branches and levels of government (Section 2 of the ATI Act).4 The Slovak ATI Act also covers private entities managing public funds, state-owned enterprises, and other entities performing public functions. The Slovak ATI Act also covers municipalities, entities established by law, and stated-owned enterprises which are established by state or municipalities. With respect to state-owned enterprises, the Act does not reflect changes in ownership structure of state-owned enterprises and does not comprise subsidiaries, so the Slovak Republic could consider introducing in its legal order the dynamic definition of state-owned enterprises to comprise all of them.

Regarding proactive disclosure,5 Section 5 of the Slovak ATI Act provides a mandatory list of information to be proactively disclosed, including the organigram and functions of institutions, as well as policy proposals, legislations and draft laws. The law does not include budgeting documents nor audit reports, however, these elements are disclosed in practice through other legal frameworks such as Act No. 431/2002 Coll. on Accounting, Act No. 423/2015 Coll. on Statutory Audit, among others. However, the fragmentation of disclosure obligations in several laws and regulations can be a challenge for some public officials to be aware of their obligations as well as for stakeholders to use their right. Having a harmonised list of these obligations, either in a single law or in a manual/guide, can simplify procedures and increase proactive disclosure increasing the efficiency of public bodies. The Slovak Republic could therefore consider creating a manual or guide with all legal obligations of proactive disclosure for public bodies.

With regards to provisions for reactive disclosure,6 the Slovak Republic’s ATI Act provides that legal and natural persons can file a request for information. While they do not need to indicate any legal justification or reason for the request, they are required to provide identification (Section 3). According the Ministry of Justice, in practice, the proof of identity is not verified in an information request procedure. This is also the case in some countries such as Chile, where de facto, proof of identity is not required and only demand for an email or contact address to send the requested information. Other countries, such as Mexico, Australia and Sweden, provide this protection de jure, with legislation explicitly protecting the integrity and privacy of individuals and parties that file a request for information.

Public institutions in the Slovak Republic may deny access to information that fall under a list of exceptions, including national security, international relations, protection of personal data, and commercial confidentiality, among others (Section 8-12). International good practice suggests that all exceptions should be clear, probable and with a specific risk of damage to public interest, or legally protected by a personal interest. Public interest tests and harm tests are two common ways to exempt information to ensure that these are proportionate and necessary (Right2Info, n.d.[5]). While the list of exemptions of the Slovak Republic aligns with international good practice, the public interest and harm tests are not provided in the ATI Act. To that end, the Slovak Republic could ensure that the ATI includes clear public interest and harms tests, and provide tailored guidance to support public officials in applying exceptions. One example is the Council of Europe Convention on Access to Official Documents, also known as the Tromsø Convention, which specifies: “Access to information contained in an official document may be refused if its disclosure would or would be likely to harm any of the interests mentioned in paragraph 1 [which state the possible limitations to access to official documents], unless there is an overriding public interest in disclosure” (Council of Europe, 2009[6]).

The Slovak Republic could strengthen implementation of the Act on Access to Information by ensuring public bodies and institutions have the appropriate human and financial resources to handle requests

In addition to a solid legal framework, effective institutional arrangements are also essential to implement the right to information. These arrangements concern several aspects, including where and how information is published, to whom requests can be made, and timeliness of responses.

To facilitate the proactive and reactive disclosure of information prescribed by ATI laws, 52% of OECD countries have established an information office or officer, which means a person responsible for responding to access to information requests on records held by their institutions and/or for the proactive disclose of information according to the law. While the Slovak ATI Act does not provide for such a role, in practice, every public body or institution has its own information unit or information officer/s to handle the requests for information. Aside from facilitating the proactive and reactive disclosure of information, a designated information office or officer can help ensure timelines are upheld. Currently, the ATI act provides that once a request is filed, public bodies/institutions confirm receipt on request of a natural or legal person and provide a response within 8 working days. An extension of 8 working days may apply under specific reasons listed in the Act, such as searching and gathering large amounts of diverse information (Section 17). This threshold is significantly lower than the average delay for response in OECD countries of 20 working days. In case of a denial, the ATI Act requires public bodies to provide a justification to requesters. However, in practice, CSOs reported that the legal timeframe is often not respected in the Slovak Republic as they face frequent delays when requesting information and there have even been cases where no response was provided.

These situations undermine stakeholders’ ability to scrutinise information and to provide timely and evidence-based inputs to draft laws and other public decisions and actions. The information unit or information officer/s in public bodies/institutions receiving requests should ensure that they uphold the timelines. To that end, the government could consider providing additional training and guidance to build officials capacity to review and respond to requests.

The Slovak Republic could establish a body responsible for overseeing the implementation of the Act on Access to Information and receiving complaints of non-compliance

Oversight bodies are another essential feature to ensure an effective access to information system. While the responsibilities of such bodies vary widely among OECD member and partner countries, three broad functions exist: 1) enforcement 2) monitoring and 3) promotion of the law. In the Slovak Republic, the ATI Act does not provide for a single body in charge of carrying out these functions but rather designates different bodies and mechanisms for doing so.

In respect to enforcement, the ATI Act provides for sanctions for non-compliance for the disclosure of untrue or inaccurate information, breaching of obligations or any violation to the right to information (Section 21a). However, according to civil society, civil servants who did not respect the periods for information disclosure stipulated in the law, or did not fully answer the requests, are rarely sanctioned. Requesters may appeal a decision in case of a denial of information, of negative administrative silence (failure to provide a response), breaches of timelines and in case of excessive fees. There are two mechanisms to appeal the decision. First, requesters may file an internal appeal to the public body/institution within 15 days from the delivery of a decision or the expiration of the period for compliance with the request (Section 19). Second, requesters may appeal the public body/institution’s decision to an administrative court. While courts cannot disclose the information directly, they have binding legal opinion that can force public bodies to comply. In addition to both mechanisms (i.e. internal and judicial appeals), most OECD countries also provide the opportunity to file an external appeal to an independent oversight institution (e.g. central government authority, an information commission, Ombudsman).

While not mentioned in the ATI Act, the Public Defender of Rights in the Slovak Republic (Ombudsman Office) can respond to complaints related to possible violation of a right to access to information by a public administration body. This falls under its larger mandate to protect fundamental rights and freedoms, which are defined by the Act No. 564/2001 but not dedicated to overseeing the proper implementation of the ATI Act. While the Ombudsman Office is a valuable recourse for stakeholders, the overall lack of a dedicated oversight body for ATI hinders the effective implementation of the ATI Act in the Slovak Republic and limits the capacity of stakeholders to make further use of this right.

The monitoring and the promotion of the ATI Act fall under the responsibility of each public body or institution subject to the law. For monitoring, each body is responsible for providing a registry of requests with the date of filling of request, subject matter of request, result of compliance with request and the possibility to file an appeal (Section 20). Concerning promotion, each body should disclose the means to obtain information (where the request may be filed, procedure of filling, remedies, etc.) in an accessible web page (Section 5). While these are important measures that should be continued and expanded in each public body, the lack of a single body that centralises the monitoring and promotion responsibilities contributes to a fragmented approach, hindering efficiency and resulting in weaker compliance.

To that end, the government could consider creating an oversight body with a clear and well-disseminated mandate setting clear roles and responsibilities. The institutional autonomy and the independence of public officials within the body are key to ensure impartiality of the decisions and the operations. The enforcement capacity, both in terms of competence to issue sanctions and of having adequate human and financial resources, is crucial for such a body to effectively conduct its mandate. The government could follow the example of the National Institute of Transparency, Access to Information, and Protection of Personal Data (INAI) in Mexico, which has constitutional autonomy and is independent from state authorities (see Box 5.1).

Box 5.1. The National Institute of Transparency, Access to Information, and Protection of Personal Data (INAI) of Mexico

Following the adoption of the Mexican ATI law in 2002, the INAI was first established as a decentralised body of the Ministry of the Interior. Due to its lack of autonomy, many stakeholders, including citizens and politicians across the political spectrum, demanded the creation of an autonomous body, which was then created through a constitutional reform in 2014. Given that the INAI is a constitutional body, it is independent from other state authorities, and therefore free from the influence of the executive, legislative, or judiciary branches of government.

The INAI is composed of seven commissioners who are designated by the Congress of the Mexican Federal Union to guarantee their independence. The law establishes that profiles of stakeholders who have relevant experience in ATI and protection of personal data should be chosen.

Currently, the main role of the INAI is to guarantee that 865 federal public entities grant access to public information in line with the law. It also responds to appeals, co‑ordinates the National Transparency System and promotes transparency and ATI more broadly. Since 2003 until the end of 2020, more than 2 million requests for ATI have been made. In that same period, requesters made more than 100 000 appeals.

The INAI has represented one of the most important democratic advances in Mexico and has been key to expose several high profile cases unveiling corruption and human rights abuses through the use of ATI.

Source: INAI, What is the INAI? https://home.inai.org.mx/?page_id=1626

Improving stakeholder engagement in the policy‑making process

Ensuring the access of all stakeholders to inform and shape public policies is key to achieving better policies. It implies that policy makers will be better informed to legislate and that most interests will be included and represented in policy outcomes. There are several ways to allow for stakeholders’ participation (Box 5.2).

Box 5.2. Types of stakeholder participation

Stakeholder participation, as defined by the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, refers to all the ways in which stakeholders can be involved in the policy cycle as well as in service design and delivery, including information, consultation and engagement.

Information: an initial level of participation characterised by a one-way relationship in which the government produces and delivers information to stakeholders. It covers both on-demand provision of information and “proactive” measures by the government to disseminate information.

Consultation: a more advanced level of participation that entails a two-way relationship in which stakeholders provide feedback to the government and vice-versa. It is based on the prior definition of the issue for which views are being sought and requires the provision of relevant information, in addition to feedback on the outcomes of the process.

Engagement: when stakeholders are given the opportunity and the necessary resources (e.g. information, data and digital tools) to collaborate during all phases of the policy-cycle and in the service design and delivery.

Source: (OECD, 2017[7])

The Slovak Republic could strengthen the Interdepartmental Comments Procedure, and ensure mandatory public consultations are adequately implemented

In the Slovak Republic, the obligation to consult stakeholders – including ministries and other public bodies – for draft laws is enshrined in the Act on Legal Formation on the Collection of Laws in the Slovak Republic (2015). The Interdepartmental Comments Procedure (Medzirezortné pripomienkové konanie) enables any interested party – including civil society organisations, individual citizens and other public bodies – to comment on proposed legislation, access comments made by other contributors, and assess which inputs were included in the legislation. Every governmental organisation must publish proposed legislation on the slov-lex.sk website. A minimum duration of at least 2 weeks for the procedure is established in the legislation, which can be shortened under circumstances specified by the law. Any interested stakeholder can comment through the online portal following compulsory registration. All comments are responded to, and the responses indicate whether they were accepted, partially accepted or rejected, along with a justification. The Portal also includes the possibility of a Collective Comment if a proposal is backed by at least 500 natural and or/legal persons. In this case, the relevant ministry or governmental organisation must consult with the group who made the proposal.

To support implementation of the law, the Office of the Plenipotentiary of the Slovak Government for the Civil Society Development published in August 2020 guidance on involving stakeholders in the consultation process, with information on participation processes and related methodological materials to support engagement (Office of the Plenipotentiary of the Slovak Government for the Civil Society Development, 2020[8]). This guidance can be considered as a positive development in engaging stakeholders in the policy‑making process. However, concerns were voiced by stakeholders that mandatory periods for sending comments were not always respected and collective comments were not always considered. For example, mandatory consultations for the proposal of a new regulation of public procurement were not held (Transparency International Slovakia, 2020[9]; Euractiv, 2020[10]).

Therefore, at a minimum, the Slovak Republic should respect the timeframes outlined in the stakeholder consultation process outlined in the law. This would enhance transparency in government activities and enable all stakeholders to have access to the information they require to perform their oversight role. In addition, the Slovak Republic may also be more proactive in informing stakeholders about upcoming consultations, for example by publishing timelines on upcoming public consultations online. This will allow them to prepare adequately for the consultation process, for example by requesting useful information or data from the government.

The Slovak Republic could improve transparency in the parliamentary stage of the law-making process

Currently, there are no formal procedures to comment on draft legislation during parliamentary stages of the law-making process. In practice, it is common for citizens and interest groups to write directly to MPs and attend committee meetings to express their opinion. Anyone can attend committee meetings, and they are commonly attended by interest groups. There is however no regulation to ensure all interest groups are equally represented. This opacity creates a window of opportunity for stakeholders to influence the legislative process. As a result, the final law is often significantly different from the draft law that was shared during the public consultation procedure. This affects the predictability of the law-making process, negatively affecting the business and regulatory environment.

However, MPs can chose to have a comments procedures (using the same tools and digital infrastructure as the Interdepartmental comments procedure), but this is done on a voluntary basis, as it is not required by the current legal framework. This practice should be applied more commonly, possibly as a default option, and justification should be provided in case this procedure is not followed. Nevertheless, this would require substantial legislative changes; followed by the need to strengthen capacities of MPs' personal assistants and the Chancellery of the National Council of the Slovak Republic. Furthermore, the lists of attendees of committee meetings can be made public in order to provide clarity on who is present or represented. However, such practice should be analysed and applied in compliance with the relevant personal data protection rules. These recommendations are closely linked to the next set of recommendations related to lobbying practices.

Fostering integrity and transparency in lobbying

Lobbying in all its forms is a legitimate act of political participation. It grants stakeholders access to the development and implementation of public policies. Lobbyists, as well as advocates and all those influencing governments, represent different valid interests and bring to policy makers’ attention much needed insights and data on all policy issues.

Lobbying can be beneficial to our societies. Lobbying for green cars or for increasing competition in key economic sectors, are only a few of the examples in which lobbying can benefit not only those with a specific interest but also policy makers, by providing them evidence and data, and ultimately, benefiting society as a whole.

However, the evidence is that policy making is not always inclusive. In fact, evidence regularly emerges showing that the abuse of lobbying practices can result in negative policy outcomes, for example inaction on climate policies. The COVID-19 crisis, characterised by the set-up of emergency task forces and adoption of stimulus packages, often through urgent and extraordinary procedures, also showed that lobbying risks persist, in particular when there is a need for rapid decision making (OECD, 2021[1]).

The Slovak Republic could foster transparency in lobbying through the adoption of a framework covering any kind of activity to influence the policy-making process in all branches of government

The Slovak Republic currently remains without any specific framework regulating lobbying activities. As a result, there is no legal definitions of a lobbyist and lobbying activities (OECD, 2021[1]; Transparency International Slovakia, 2015[11]). Several attempts to adopt legislation have failed in the past (Box 5.3), and the absence of any framework has contributed to negative perceptions of lobbying activities. Indeed, meetings with stakeholders revealed that lobbying activities are often perceived in the Slovak Republic as an opaque activity leading to undue influence.

Box 5.3. Previous attempts to regulate lobbying in the Slovak Republic did not succeed

In 2005, the deputy Prime minister and Minister of Justice proposed an initiative to regulate professional lobbying activities, as part of the commitment to regulate lobbying in the Government Programme from 2002. Under the bill, lobbyists had to publish reports on their lobbying activities every three months, including income and expenditures once a year. The bill did not however cover key actors such as non-government organisations and lobbying activities were narrowed to meetings taking place within the premises of the Nacional Council. The bill was withdrawn from the parliament in the autumn 2005, due to too many amendments submitted from MPs, some of which argued the bill would create too much bureaucracy.

Yet, a new momentum for increasing integrity and transparency in lobbying has emerged in the Slovak Republic, as transparency of law-making processes has become a strategic priority of the Slovak Government, embedded in the Anti-Corruption Policy 2019-2023. Measures 2.1 and 2.5 of the Slovak Anti-Corruption Policy provide for the adoption of a legal framework regulating lobbying, as well as mechanisms enabling a legislative footprint. The Deputy Prime Minister is in charge of proposing a lobbying bill, with the Ministry of Economy as co-manager. The current deadline is set for 31 December 2022.

The OECD Recommendation on Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying (hereafter “The Lobbying Principles”) stipulates that countries should provide an adequate degree of transparency to ensure that public officials, citizens and businesses can obtain sufficient information on lobbying activities. At the OECD level, 22 countries have now adopted a transparency tool to provide transparency over lobbying. A majority of these countries have public online registries where lobbyists and/or public officials disclose information on their interactions. This is the case for example in Australia, Canada, Chile, France, Ireland, and the United States. The Netherlands has a voluntary register in the House of Representatives where lobbying firms, NGOs and businesses can register certain details. Another approach is to require certain public officials to disclose information on their meetings with lobbyists through open agendas (Spain + EU level with senior public officials). Other countries require ex post disclosures of how decisions were made (“legislative footprint”). Iceland, Latvia, Luxembourg and Poland have implemented such requirements (OECD, 2021[1]). The information disclosed can be a table or a document listing the identity of lobbyists met, public officials involved, the object and outcome of their meetings, as well as an assessment of how the input received was factored into the final decision (Box 5.4).

Box 5.4. Ex post disclosures of how decisions were made in Latvia

In Latvia, employees covered by transparency requirements are required to inform the direct manager or the head of the institution of any anticipated meeting with lobbyists, and disclose the information received from lobbyists, including what interests they represent, what proposals were expressed, and in what way they have been considered. If the proposal expressed by lobbyists is considered in drafting or making a decision, this must be indicated in the document related to such a decision (e.g. in the summary, statement, cover letter) and, where possible, made publicly available.

Source: (OECD, 2021[1])

The OECD experience shows that the avenues by which stakeholders engage with governments encompass a wide range of practices and actors, and are also changing in nature and format with wider societal evolutions such as digitalisation and the advent of social media, which has made lobbying more complex than ever before. For example, the phenomenon of “astroturfing”, the practice of creating and funding citizens’ associations or organisations to create an impression of widespread grassroots support for a policy or agenda, was reported by Transparency International Slovakia as a common lobbying practice in the country. In addition, increasing globalisation also further complicates the regulation of corporate influence, as many multinational corporations have become part of the economy of hosting countries, blurring the national boundaries. Thus, the OECD Lobbying Principles make it clear that lobbying should be “considered more broadly and inclusively to provide a level playing field for interest groups, whether business or not-for-profit entities, which aim to influence public decisions”. For example, Canada, Ireland and the EU transparency Register provide a broad definition of “lobbyist” and “lobbying”, imposing transparency measures equally on all the actors who aim to influence decision making (Box 5.5).

Box 5.5. Defining lobbying in national regulations: the cases of Canada, Ireland and the European Union

Regulation of Lobbying Act in Ireland

The 2015 Regulation of Lobbying Act is simple and comprehensive: any individual, company or CSO that seeks to directly or indirectly influence officials on a policy issue must enrol on a public register and disclose any lobbying activity. The rules cover any meeting with high-level public officials, as well as letters, emails or tweets intended to influence policy.

According to the regulation, a lobbyist is anyone who employs more than 10 individuals, works for an advocacy body, is a professional paid by a client to communicate on someone else’s behalf or is communicating about land development. All individuals and entities covered by this definition are required to register and disclose the lobbying activities they carry out and to comply with an established code of conduct.

Regulation of social media as a lobbying tool in Canada and at the EU level

The Canadian Register of Lobbyists and the EU Transparency Register require lobbyists to disclose information on the use of media as a lobbying tool. In Canada, lobbyists are required to disclose any communication techniques used, which includes any appeals to members of the public through mass media, or by direct communication, aiming to persuade the public to communicate directly with public office holders, in order to pressure them to endorse a particular opinion. The Lobbying Act categorises this type of lobbying as “grassroots communication.” Similarly, the EU Transparency Register covers activities aimed at “indirectly influencing” EU institutions, including through the use of intermediate vectors such as media, public opinion, conferences or social events.

Source: (OECD, 2021[1])

In order to set up a comprehensive scope of the regulation, the draft law on lobbying could include a broader approach to lobbying to include any “act of lawfully attempting to influence the design, implementation, execution and evaluation of public policies and regulations administered by executive, legislative or judicial public officials at the local, regional or national level” (OECD, 2021[1]). Indeed, a definition of lobbying should not be limited to professional lobbying, and may include for example CSOs and any other organisations attempting to influence. Moreover, lobbying activities should not be narrowed to a communication between a lobbyist and a public official.

Furthermore, the law could also provide for the public availability of information on lobbying activities. The Lobbying Principles explicitly state that disclosure should capture the objective of the lobbying activity to enable public scrutiny. In Canada for example, the requirement that lobbyists publish monthly communication reports allowed publication of timely information on COVID-19-related lobbying activities, which indicated the objectives of the lobbying activities as well as the public officials and policies targeted (OECD, 2021[1]).

In addition, the law should assign clear responsibilities for monitoring compliance with the lobbying regulations, establish sanctions for non-compliance, and ensure sufficient resources are provided to achieve the objectives of the law. In particular, a key challenge will be to design tools to collect, verify and manage information on lobbying practices, so that it can be published in an open, re-usable format and used to analyse trends in large volumes of data. In particular, data analytics and artificial intelligence can facilitate the verification and analysis of data. For example, France requires the electronic submission of registration and activity reports with features that facilitate disclosures. The High Authority for Transparency in Public Life has now set up an automatic verification mechanism using an algorithm based on artificial intelligence, to detect potential flaws upon validation of annual lobbying activity reports (OECD, 2021[1]).

Awareness raising and stakeholder consultation on lobbying

As in many countries, lobbying has a negative connotation in the Slovak Republic. This stems partly from a number of recent cases of undue influence and corruption through lobbying, but is also founded in a more fundamental and ‘traditional’ distrust in government and politics.

To improve the perception of lobbying among citizens, the Slovak Republic could further promote stakeholder participation in the development and implementation of the lobbying regulations and raise awareness

However, the renewed government commitment in the Slovak Republic and the prospective development of new policy measures on lobbying creates a momentum to curb this negative perception, both through stakeholder engagement in the development and implementation of lobbying regulation, and through awareness raising.

Point C.6 of the Slovak Anti-Corruption Policy recommends that the Secretary General of the Chancellery of the National Council and the Government Plenipotentiary for the Development of Civic Society provide assistance in the preparation of the draft bill on Lobbying. Furthermore, the National Council of the Slovak Republic specified that working group will be established to work on the draft lobbying law. However, as reported by Slovak stakeholders during the fact-finding interviews, the preparation phase has not effectively started and no consultations have yet taken place. The composition of the working group is also not known yet, but will likely include CSOs and private sector representatives. The Slovak Republic could further work with stakeholders and citizens to involve them in the development process of the lobbying framework, and also in its implementation, following the example of Ireland (Box 5.6). Such an inclusive process can help mitigate negative perceptions of lobbying.

Box 5.6. Supporting a cultural shift towards the regulation of lobbying in Ireland

The Irish regulations on lobbying entered into force in 2015 and were informed by a wide consultation process that gathered opinions on its design, structure and implementation, based on the OECD Recommendation on Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying.

The Standards in Public Office Commission established an advisory group of stakeholders in both the public and private sectors to help ensure effective planning and implementation of the Act. This forum has served to inform communications, information products and the development of the online registry itself. The Commission also developed a communications and outreach strategy to raise awareness and understanding of the regime. It developed and published guidelines and information resources on the website to make sure the system is understood. These materials include an information leaflet, general guidelines on the Act and guidelines specific to designated public officials and elected officials.

On 28 November 2018, the Standards in Public Office Commission launched its Code of Conduct for persons engaged in lobbying activities. The definition of this code was also based on a wide consultation process, involving local, national and international actors. All inputs to the consultation were made publicly available on the website of the Commission along with the code.

The Lobbying Act provides for regular reviews of the operations of the Act by the Minister for Expenditure and Reform. The reviews take into account input received by key stakeholders, including those carrying out lobbying activities and the bodies representing them. Reviews showed that there is today widespread support for the Act among lobbyists, despite being one of the strictest laws on lobbying transparency in the OECD. The law quickly dispelled initial concerns and worries that the regulation would inhibit the ability of lobbyists and public officials to interact with each other. The Act recognised lobbying as a legitimate activity, supported the professionalisation of lobbying in Ireland, and provided strong reputational value for lobbyists.

Furthermore, dissemination of the prospective lobbying framework may feature in a broader information and awareness raising strategy for the general public on corruption prevention. The various stakeholders from the private sector and civil society may serve as multipliers of the messages. The key features of an awareness raising campaign are described in chapter 4, and, as also argued there, it would resort to the Ministry of Economy, together with the Corruption Prevention Department of the Government Office, to develop the overall communication strategy, earmark the required resources, and lead its implementation.

Improving the diversity and transparency in expert groups and advisory bodies

An advisory body or expert group (hereafter “advisory group”) refers to any committee, board, commission, council, conference, panel, task force or similar group, or any subcommittee or other subgroup thereof, that provides governments advice, expertise or recommendations. Such groups are composed of public and private sector members and/or representatives from civil society and may be set up by the executive, legislative or judicial branches of government. Governments across the OECD make wide use of these groups to inform the design and implementation of public policy.

Advisory groups can help strengthen evidence-based decision making. However, without sufficient transparency and safeguards against conflict of interest, they may risk undermining the legitimacy of their advice or provide advice that is incorrect or biased, without public scrutiny. Private sector representatives participating in these groups have direct access to policy-making processes without being considered external lobbyists, and may, whether unconsciously or not, favour the interests of their company or industry, which may also increase the potential for conflicts of interest.

To allow for public scrutiny, information on a group’s structure, mandate, composition and criteria for selection must be made available online. In addition, and provided that confidential information is protected and without delaying the work of these groups, the agendas, records of decisions and evidence gathered should also be made transparent. (OECD, 2017[14]).

The Slovak Republic could introduce rules on the establishment, composition and functioning of advisory and expert groups

In the Slovak Republic, there are no mandatory requirements to publish information on expert and advisory groups. Therefore, a first improvement would be to conduct a mapping of the various expert groups and bodies that operate along the different sectors and line ministries. This task could be integrated in the Sectoral Anti-Corruption Plans under the responsibility of each line ministry and government agency. Second, the composition of these groups should be published online, to allow for public scrutiny. Third, for each of these expert and advisory boards, transparent procedures should be in place for the recruitment, selection and remuneration of experts, as well as for management of conflicts of interest. One method of ensuring these good governance practices is through a code of conduct or transparency code for working groups. On this issue, the Slovak Republic may learn from the experience of the Transparency Code for policy working groups in Ireland (Box 5.7).

Box 5.7. Ireland has a Transparency Code for policy working groups

In Ireland, any working group set up by a minister or public service body that includes at least one designated public official and at least one person from outside the public service, and which reviews, assesses or analyses any issue of public policy with a view to reporting on it to the Minister of the Government or the public service body, must comply with a Transparency Code.

Interactions between members of policy working groups are exempt from lobbying transparency requirements only if the working group adheres to the Transparency Code, which requires the group to publish the membership, terms of reference, agendas and minutes of meetings. If the requirements of the Code are not adhered to, interactions within the group are considered a lobbying activity under the Law. The ministry or public body that set up the working group is expected to ensure the Code is implemented

Source: Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, Transparency Code prepared in accordance with Section 5 (7) of the Regulation of Lobbying Act 2015, https://www.lobbying.ie/media/5986/2015-08-06-transparency-code-eng.pdf.

Moreover, although this does not directly concern transparency, a balanced representation of interests in terms of private sector and civil society representatives (when relevant), as well as expertise from a variety of backgrounds, helps ensure equity and diversity in the advice of the advisory group. For example, the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation in Norway published guidelines on the use of independent advisory committees, which specify that the composition of such groups should reflect different interests, experiences and perspectives. The Slovak Republic may consider this type of guidelines as well.

Strengthening integrity standards on lobbying for public officials

Lobbying and influence practices do not happen in a vacuum; there is always an interlocutor on the side of the government, or public sector more broadly, involved. As such, the stronger the integrity mechanisms are for public sector employees, the lower the likelihood that lobbying will lead to undue influence and/or abuse of power. Therefore, it is important to examine this wider ecosystem of integrity standards in the public sector, and understand how they can curb undue influence. For example, effective gift policies can safeguard the neutrality of public sector employees. A sound system for asset declarations can help flag situations of illicit enrichment and undue influence. An effective whistleblower protection regime can both serve as a prevention and detection mechanisms of undue influence through lobbying and abuse of power. A number of these integrity standards are extensively discussed in chapter 2 of this publication. In this section, a selection of additional recommendations are presented dealing specifically with lobbying.

The Slovak Republic could introduce specific integrity standards on engaging with lobbyists for public officials

Policy‑making decisions remain the prerogative of policy makers, who are the guardians of the public interest and balance all considerations for adopting a policy in that light. The Lobbying Principles indicate that countries should provide such standards to give public officials clear directions on how they are permitted to engage with lobbyists and representatives of interest groups. Therefore, integrity standards and ethical obligations on lobbying may be included in a specific lobbying law, or included in the general standards for public officials, such as the code of ethics for public officials.

Depending on the type of document in which they are included, standards for public officials and their interactions with lobbyists may include:

The duty to treat lobbyists equally by granting them fair and equitable access.

The obligation to refuse meetings with lobbyists who did not register (if a mandatory lobbying register is in place).

The obligation to report violations of lobbying-related rules (including rules on gifts) to competent authorities.

The duty to publish information on their meetings with lobbyists (through a lobbying registry or open agendas).

Given the current absence of these standards in the public sector in the Slovak Republic, the government could consider including standards and guidelines for public officials on their interactions with lobbyists and representatives of interest groups in the upcoming law on lobbying and/or in the Code of Ethics currently under development (see Chapter 2). The examples of Australia, Chile and the Netherlands may serve as a source of inspiration (see Box 5.8).

Box 5.8. Standards of conduct and guidelines on lobbying activities for public officials

The Australian Government Lobbying Code of Conduct includes obligations for public officials

Government representative covered by the Lobbying Code of Conduct cannot knowingly and intentionally be a party to lobbying activities by a lobbyist or an employee of a lobbyist who is not on the Register of Lobbyists, or who has failed to inform them that they are lobbyists (whether they are registered, the name of their clients, and the nature of the matters they wish to raise). They must also report any breaches of the Code to the Secretary of the Attorney-General's Department.

The Lobbying Law in Chile establishes obligations for public officials

The Lobbying Law in Chile places the obligation to register information on lobbying on public officials. Public officials and the administrations that employ them have a duty to guarantee equal access for persons and organisations to the decision-making process. Public administrations are not required to respond positively to every demand for meetings or hearings; however, if it does so in respect to a specific matter, it must accept demands of meetings or hearings to all who request them on the said matter.

The Dutch Code of Conduct provides guidelines for public officials to consider indirect influence

While the Netherlands does not have a lobbying regulation adopted at the national level with mandatory standards for public officials, the Dutch Code of Conduct on Integrity in Central Government reminds public officials to consider indirect influence: “You may have to deal with lobbyists in your work. These are advocates who try to influence decision making to their advantage. That is allowed. But are you always aware of that? And how do you deal with it? Make sure you can do your work transparently and independently. Be aware of the interests of lobbyists and of the different possibilities of influence. This can be done very directly (for example by a visit or invitation), but also more indirectly (for example by co-financing research that influences policy). Consult with your colleagues or supervisor where these situations may be present in your work”.

Source: Australia: Lobbying Code of Conduct https://www.ag.gov.au/integrity/publications/lobbying-code-conduct; Chile: Lobbying law https://www.leylobby.gob.cl/; Netherlands: Code of Conduct on Integrity in Central Government, https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stcrt-2019-71141.html

The Slovak Republic could strengthen cooling-off periods before and after public employment

Ensuring integrity in lobbying also involves establishing standards for public officials leaving office. Movement between the private and public sectors results in many positive outcomes, notably the transfer of knowledge and experience. However, it can also provide an undue or unfair advantage to influence government policies if not properly regulated (OECD, 2004[15]; OECD, 2010[16]). The Lobbying Principles state that “[c]ountries should consider establishing restrictions for public officials leaving office in the following situations: to prevent conflict of interest when seeking a new position, to inhibit the misuse of ‘confidential information’, and to avoid post-public service ‘switching sides’ in specific processes in which the former officials were substantially involved. It may be necessary to impose a ‘cooling-off’ period that temporarily restricts former public officials from lobbying their past organisations. Conversely, countries may consider a similar temporary cooling-off period restriction on appointing or hiring a lobbyist to fill a regulatory or an advisory post.” (OECD, 2010[17]).

As also discussed in Chapter 2, the Slovak Republic could strengthen the cooling-off periods before and after public employment. Currently, Article 8 of the Constitutional Act on the Protection of Public Interest in the Exercise of the Public Officials’ Office No. 357/2004 Coll. (“Restrictions following departure from public office”) provides safeguards to regulate certain public officials taking new jobs in the private sector for one year after leaving the public sector. The one-year cooling-off period applies to decision makers7 who, during the two years prior to the end of their service made or took part in decisions regarding a state subsidy or any other form of benefit to natural or legal persons. During the cooling-off period, these public officials may not:

Be employed in an employment relationship with those persons, if their monthly remuneration in this employment is higher than 10 times the minimum wage.

Be a member of the management, control or supervisory body of those persons.

Be a partner, member or shareholder of those persons.

Conclude a contract to act on behalf of these persons.

Given that there is currently no official definition of lobbying in the Slovak Republic, these provisions do not include lobbying as a specific activity that would require the application of a “cooling-off period”. To mitigate risks of conflicts of interests, the Slovak Republic could expand the application of the cooling-off period to members of Parliament, and remove the remuneration criteria.

The Slovak Republic could also consider including in the cooling-off other restrictions such as a prohibition to use confidential information acquired during public office, and introducing a ban on lobbying activities targeting institutions in which public officials were employed or with which they had dealings in their last two years of office. Lastly, another factor to take into account include tailoring the length of the restrictions to the seniority of public officials or type of problem area. For example, a ban on lobbying may be appropriate for a specific length of time, but restrictions on the use of insider information should be for life, or until the sensitive information is public. The new lobbying ban in the Netherlands can be taken as an example of a tailored approach to the level of seniority of public officials (Box 5.9).

Box 5.9. Lobbying ban in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, a circular adopted in October 2020 – “Lobbying ban on former ministries” – prohibits ministers and any officials employed in ministries to take up employment as lobbyists, mediators or intermediaries in business contacts with a ministry representing a policy area for which they previously had public responsibilities. The length of the lobbying ban is two years. The objective of the ban is to prevent retiring or resigning ministers from using their position, and the knowledge and network they acquired in public office, to benefit an organisation employing them after their resignation. The secretary-general of the relevant ministry has the option of granting a reasoned request to former ministers who request an exception to the lobbying ban.

Source: (OECD, 2021[1])

In addition, the Slovak Republic could introduce restrictions on private sector representatives joining the public sector, which can also pose significant risks of conflict of interest. In OECD countries, pre-public employment take various forms, such as bans and restrictions for a limited period, interest disclosure prior to or upon entry into functions, ethical guidance, pre-screening integrity checks or reference checks. The example of the US (see Box 5.10) may be considered.

Box 5.10. Restrictions on private-sector employees being hired to fill a government post in the United States

Once they have taken office, former private-sector employees and lobbyists are subject to a one-year cooling-off period in situations where their former employer is a party or represents a party in a particular government matter. This restriction applies not only to former private-sector employees and lobbyists, but also to any executive branch employee who has, in the past year, served as an officer, director, trustee, general partner, agent, attorney, consultant, contractor or employee of an individual, organisation or other entity. In the case of an employee who has received an extraordinary payment exceeding USD 10 000 from their former employer before entering government service, the employee is subject to a two-year cooling-off period with respect to that employer.

Source: (OECD, 2021[1])

Lastly, the government could also develop a central monitoring mechanism to ensure compliance with the regulation and sanctions in the case of non-compliance. These responsibilities are currently split between the Incompatibility of Functions Committee of the National Council of the Slovak Republic, academic senates, and commissions of the municipal councils. These authorities may rule to grant an exemption from the prohibitions laid down, following a declaration made by a public official, if the prohibition is disproportionate given the nature of the conduct. The authority must publish its decision on the exemption, along with the reasoning, in accordance with Article 7(8) of the Constitutional Act No. 357/2004 Coll. (see Article 8 (4)). A central monitoring mechanism may provide insights on the scale and frequency of cooling-off cases and violations, which may inform policy updates or reallocation of priorities. The example of the French High Authority for Transparency in Public Life may be considered in this regard (see Box 5.11).

Box 5.11. The High Authority for Transparency in Public Life monitors movements between the public and private sector in France

The Act of 6 August 2019 on the transformation of the public service clarified France’s monitoring mechanisms for movements between the public and private sectors, by supressing the Civil Service Ethics Commission and transferring several of its missions to the High Authority for Transparency in Public Life. The integrity agency, which already controlled the asset and interest declarations of high-ranking officials, and administers the register of lobbying, is now the central agency overseeing controls for movements between the public and private sectors.

Post-public employment

Former ministers, local executive chairmen and members of an independent administrative authority must, for a period of three years after the termination of their functions, refer to the High Authority to examine whether the new private activities that they plan to exercise are compatible with their former functions.

The ethical control of the vast majority of public servants is now the responsibility of the administration itself. This control is internalised, insofar as it is carried out by the hierarchical superior of the agent concerned, who can consult the ethics officer if there is a difficulty. The hierarchical authority has serious doubts about the project in question, even after having referred the ethics officer, it can refer the matter to the High Authority. Referral to the High Authority is compulsory certain senior public servants.

Pre-public employment

In 2020, the High Authority for Transparency in Public Life (HATVP) was tasked with a new “pre-nomination” control for certain high-ranking positions. A preventive control is carried out before an appointment to one of the following positions, if an individual has held positions in the private sector in the three years prior to the appointment:

Director of a central administration and head of a public entity whose appointment is subject to a decree by the Council of Ministers.

Director-general of services of regions, departments or municipalities of more than 40 000 inhabitants and public establishments of inter-municipal co-operation with their own tax system with more than 40 000 inhabitants.

Director of a public hospital with a budget of more than EUR 200 million.

Member of a ministerial cabinet.

Collaborator of the President of the Republic.

Source: (OECD, 2021[1])

Providing guidelines for lobbyists

Similar to the integrity standards for public officials, lobbyists share an obligation to ensure that they avoid exercising undue influence and comply with professional standards in their relations with public officials, with other lobbyists and their clients, and with the public.

The Slovak Republic could provide guidelines for lobbyists from the private sector and civil society on engaging responsibly with policy makers

In the Slovak Republic, specific guidelines encouraging the establishment and implementation of lobbying standards in domestic companies and other organisations influencing policy-making processes are not yet in place. Voluntary codes of conduct from lobbyists remain the main tool for supporting integrity for lobbyists. For example, the Slovak Chamber of Commerce and industry has adopted ethical standards. However, a broader set of guidelines for all lobbyists and representatives of interest groups from civil society would provide a level playing field for all lobbyists and set standards for the entire profession.

The Slovak Republic could increase the accountability and responsibility of private sector and civil society organisations in their lobbying activities in various ways. First, the draft law which is currently under development could include clear standards and guidelines for lobbyists that clarify the expected rules and behaviour when they engage with the decision-making process. These standards of conduct could include:

ethical obligations related to registration, for example the duty to certify that the information disclosed in the lobbying register is correct

standards of conduct on how they interact with public officials, for example the obligation to inform public officials that are conducting lobbying activities and the interests they represent, or the duty to present accurate information or not to make misleading claims.

Second, the Slovak Republic could promote responsible engagement by covering in the lobbying standards other influence activities such as activities related to political parties or election campaigns, promoting transparency in the funding of research or think tanks to generate knowledge and insights on particular policy issues, and the provision of gifts and other advantages to public officials. In this sense, the Slovak Republic could follow the example of Canada, whose Code of Conduct for lobbyists provides for a number of integrity standards for lobbyists (see Box 5.12).

Box 5.12. The Canadian Lobbyists’ Code of Conduct

Principles. Lobbyists must abide by core principles of respect for democratic institutions, including the duty of public office holders to serve, integrity and honesty, openness (being frank about their lobbying activities) and professionalism.

Rules

Transparency

Identity and purpose: when communicating with a public office holder, lobbyists must communicate their identity, the organisation or corporate entity on whose behalf the communication is made, as well as the reasons for the approach.

Accurate information: a lobbyist must take all reasonable measures to provide public office holders with information that is accurate and factual.

Duty to disclose: consultant lobbyists must inform each client of their obligations as lobbyists; the responsible office of an organisation shall ensure that employees who lobby on the organisation’s behalf are informed of their obligations.

Use of information: lobbyists must use and disclose information received from a public office holder in the manner consistent with the purpose for which it was shared.

Conflict of interest: a lobbyist shall not propose or undertake any action that would place a public office holder in a real or apparent conflict of interest.

Preferential access: a lobbyist shall not arrange for another person a meeting with a public office holder when the lobbyist and public office holder share a relationship that could reasonably be seen to create a sense of obligation. A lobbyist shall not lobby a public office holder with whom they share a relationship that could reasonably be seen to create a sense of obligation.

Political activities: when a lobbyist undertakes political activities on behalf of a person which could reasonably be seen to create a sense of obligation, they may not lobby that person for a specified period if that person is or becomes a public office holder. If that person is an elected official, the lobbyist shall also not lobby staff in their office(s).

Gifts: to avoid the creation of a sense of obligation, a lobbyist shall not provide or promise a gift, favour, or other benefit to a public office holder, whom they are lobbying or will lobby, which the public office holder is not allowed to accept.

Source: Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying, The Lobbyists’ Code of Conduct, https://lobbycanada.gc.ca/en/rules/the-lobbyists-code-of-conduct/

Proposals for action

Strengthening access to information to increase the oversight role of stakeholders

The Slovak Republic could consider reviewing the Act on Access to Information to increase its effectiveness.

The Slovak Republic could strengthen the implementation of the Act on Access to Information by ensuring public bodies and institutions have the appropriate human and financial resources to handle requests.

The Slovak Republic could establish a body responsible for overseeing the implementation of the Act on Access to Information and receiving complaints of non-compliance.

Improving stakeholder engagement in the policy‑making process

The Slovak Republic could improve transparency in the parliamentary stage of the law-making process.

Strengthening integrity and transparency in decision making

The Slovak Republic could further promote stakeholder participation in the development and implementation of the lobbying regulations and raise awareness.

The Slovak Republic could introduce rules on the establishment, composition and functioning of advisory and expert groups.

The Slovak Republic could introduce specific integrity standards on engaging with lobbyists for public officials.

The Slovak Republic could strengthen cooling-off periods before and after public employment.

The Slovak Republic could provide guidelines for lobbyists from the private sector and civil society on engaging responsibly with policy makers.

References

[6] Council of Europe (2009), Council of Europe Convention on Access to Official Documents, https://rm.coe.int/1680084826 (accessed on 14 December 2021).

[13] Department of Public Expenditure and Reform (2020), Second Statutory Review of the Regulation of Lobbying Act 2015., https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/7ef279-second-statutory-review-of-the-regulation-of-lobbying-act-2015/.

[10] Euractiv (2020), Business associations call for the principles of the legislative process to be observed, https://euractiv.sk/section/spolocnost/press_release/podnikatelske-zdruzenia-vyzyvaju-na-dodrziavanie-principov-legislativneho-procesu/?utm_source=traqli&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=6888&tqid=1PCwaWI9BFMBclg3M1WAGCZB.oXaH0ZA3oIlilsg (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[1] OECD (2021), Lobbying in the 21st Century: Transparency, Integrity and Access, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c6d8eff8-en.

[12] OECD (2020), OECD Public Integrity Handbook, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/ac8ed8e8-en.

[14] OECD (2017), Assessment of key anti-corruption related legislation in the Slovak Republic, https://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/Assessment-anti-corruption-legislation-Slovak-Republic.pdf.

[7] OECD (2017), OECD Recommendation on Open Government, http://www.oecd.org/fr/gov/open-government.htm.

[3] OECD (2017), Preventing Policy Capture: Integrity in Public Decision Making, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264065239-en.

[16] OECD (2010), Post-Public Employment: Good Practices for Preventing Conflict of Interest, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264056701-en.

[17] OECD (2010), Recommendation of the Council on Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0379.

[15] OECD (2004), Managing Conflict of Interest in the Public Service: OECD Guidelines and Country Experiences, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264104938-en.

[8] Office of the Plenipotentiary of the Slovak Government for the Civil Society Development (2020), Participation, http://www.minv.sk/?ros_np_participacia_knizna_edicia_participacia (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[5] Right2Info (n.d.), General Standards for Exceptions to Access, https://www.right2info.org/exceptions-to-access/general-standards (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[4] RTI Rating (n.d.), By Country, https://www.rti-rating.org/country-data/ (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[2] Transparency International (2021), Global Corruption Barometer. European Union 2021, https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/TI_GCB_EU_2021_web_2021-06-14-151758.pdf.

[9] Transparency International Slovakia (2020), Do not restrict transparency, competition or public control of contracts!, https://transparency.sk/sk/neobmedzujte-transparentnost-sutaz-ani-verejnu-kontrolu-zakaziek/.

[11] Transparency International Slovakia (2015), Mapping the Lobbying Landscape in Slovakia, https://www.transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Mapping-the-Lobbying-Landscape-in-Slovakia.pdf.

Notes

← 1. Article 26(5) of the 1992 Constitution notes that “public authority bodies shall be obliged to provide information about their activities in the appropriate manner in the official language. The terms and form of the execution thereof shall be laid by a law”.

← 3. Analysis based on the RTI country ranking, consulted on 22, June, 2021 https://www.rti-rating.org/country-data/.

← 4. Information collected from the 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government (SOG).

← 5. Proactive disclosure refers to the act of regularly releasing information before it is requested by stakeholders. This type of disclosure is essential to achieve more transparency in government as it ensures timely access to public information. It allows citizens to directly access relevant information while avoiding administrative procedures that can often be lengthy and costly. Most ATI laws require the proactive disclosure of a minimum set of public information and data to be published by each institution.

← 6. Reactive disclosure refers to the right to request information that is not made publicly available. These provisions usually describe the procedure for making the request, including who can file the request, the possibility for anonymity, the means to file a request, the existence of fees, and the delay for response to the request.

← 7. Decision makers include members of Governments, heads of central administration bodies, President and Vice-President of the Supreme Court, Prosecutor General and Special Prosecutor, Chairman and Vice Chairmen of the Supreme Audit Office, state secretaries, Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces, director of the Slovak Information Service, mayor of cities and municipalities, presidents of higher territorial unites, selected chairmen of regulatory bodies and other state institutions.