This chapter offers a comprehensive diagnosis of the region of Gotland, Sweden. The chapter compares Gotland’s development against national trends and a benchmark of other OECD islands and remote regions at Territorial Level 3 (TL3). It starts by presenting Gotland, its population and demographic trends, spatial and administrative structure, including some characteristics and challenges related to island economies. The chapter then describes Gotland’s economy and labour market patterns. The final section examines key factors for regional development and the well-being of its citizens, such as globalisation, accessibility, public services and the shift to a zero-carbon economy.

OECD Territorial Reviews: Gotland, Sweden

1. Socio-economic characteristics and trends

Abstract

Assessment and key findings

Gotland has distinctive geographic and administrative characteristics. Gotland is an island located centrally in the Baltic Sea. It has both municipal and regional powers, thus being at the same time one of the largest municipalities and the smallest region of Sweden in terms of number of inhabitants (about 60 970). The OECD classifies Gotland as a predominantly rural remote TL3 region (see Annex 4.B for explanation of OECD typology). Gotland’s main city, Visby, is home to about 26 000 inhabitants and offers a large share of jobs, infrastructure, trade and services of the island. Close to 60% of Gotlanders live outside Visby.

As an island, Gotland faces a number of specific challenges and opportunities. Insularity plays an important role in shaping Gotland’s socio-economic development as well as its identity and culture. As an island economy, Gotland must address a lack of critical mass, vulnerability to climate change (e.g. summer droughts and sea level rise), remoteness to international markets, higher costs to deliver services, seasonality and difficulties in attracting high-skilled labour. Notwithstanding these challenges, it also possesses a number of important assets including raw materials, a high potential for renewable energy, a high-quality university, very good broadband connectivity and a relatively diversified economy, making it an attractive location for tourists and internal migrants1 alike.

Geography and accessibility determine settlement patterns on Gotland. Gotland’s population has been growing in recent years due to migration flows. Most migrants are nationals coming from the coastal mainland, especially from Skåne, Stockholm and Uppsala and are working-age families with children. Although Gotland is performing better than benchmark islands, its population is growing slower than the Swedish average and settlement patterns remain uneven across the island. At the same time, Gotland’s population is ageing. Gotland’s demographic trends point to growing youth and elderly dependency ratios and a reduction of the working-age segment despite an influx of migration. Elderly dependency on Gotland is well above the Swedish average and the remote regions benchmark but similar to other island regions. These demographic trends present a number of challenges for both the delivery of public services and the sustainability of traditional economic sectors given that farmers, teachers and other occupations need to find successors.

Gotland’s economy is lagging in the Swedish context but performing above peer regions. Gotland has a relatively well-developed regional economy and outperforms comparable benchmark regions from European Union (EU) islands and OECD remote rural regions across a wide range of indicators. Yet, it can be considered less competitive than other Swedish regions. Gotland’s gross domestic product (GDP) is below the national average but stands significantly higher than peer islands and remote regions. Also, in terms of productivity, Gotland displays the lowest level across Swedish regions but performs better than the islands benchmark and similarly to remote regions.

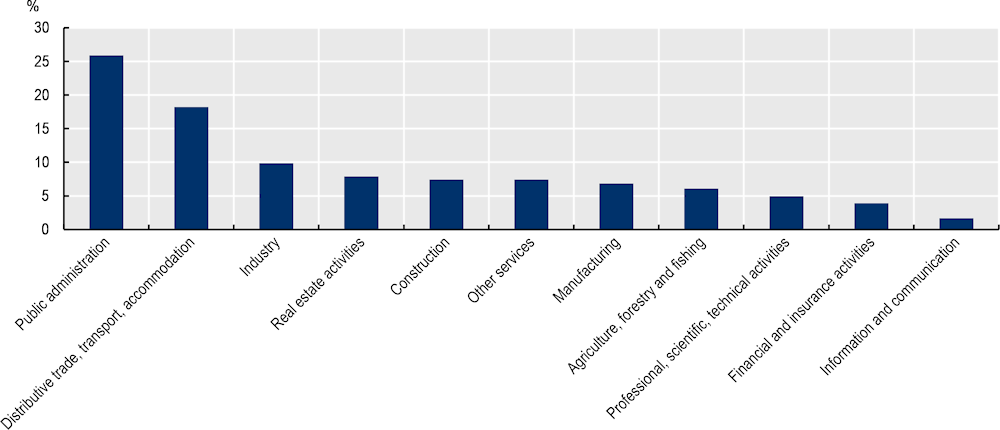

Despite its island economy, Gotland is a relatively diversified region. Gotland’s economy is dependent on the public sector, which contributes to 26% of gross value added (GVA), and trade and transport (18.2%). The remaining sectors do not each produce more than 10% of GVA: industry (9.9%), real estate (7.9%), construction (7.4%), general services (7.4%), manufacturing (6.8%), agriculture, forestry and fishing (6.1%). Amongst these, tradeable activities represent around 25% of the regional economy. Gotland’s small- and medium-sized enterprises’ (SMEs) share of national exports (60%) ranked second in 2018, demonstrating the importance of SMEs for the island. Nevertheless, Gotland’s limited size and export capacity makes it, in per capita terms, the least export-driven Swedish region.

The labour market on Gotland is diversified but small and seasonally dependent. The labour market on Gotland is relatively diversified across the island despite its small size. The employment rate for 15-74 year-olds on Gotland in 2016 (63.3%) was below the national average (67.1%). Apart from the public sector, the island is specialised in primary sectors, including agriculture and material processing activities, particularly quarrying and cement production. These are complemented by a strong tourism sector, which largely depends on Swedish tourists. Unemployment on Gotland has remained stable over the past 15 years, fluctuating between 6% to 8%, in line with the national trend. When compared to remote regions, Gotland records much lower rates, while they are higher if compared to peer EU island regions. Despite its good education system, Gotland records lower levels of education than the national average and also faces relatively high student dropout rates before reaching university, making it difficult for employers to find highly skilled workers.

Megatrends create challenges but also new opportunities for Gotland, which must be able to adapt and equip itself adequately. The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a profound process of rethinking the organisation of production systems, trade and supply chains, as well as the provision of services and the utilisation of new technologies, globally but also regionally and locally. In this new context, development policies for Gotland should aim at increasing productivity over the medium to long run by maximising the potential agglomeration benefits of its capital city Visby, fostering innovation across the entire entrepreneurship ecosystem in the region and making the most of its central position in the Baltic Sea to reach new markets. The island also needs to do more to attract and retain skilled labour and address existing bottlenecks in land use and the real estate market. The university has a central role to play in training a skilled workforce and in linking the island to international knowledge hubs. At the same time, Gotland should take advantage of opportunities related to its green economy potential and digital connectivity. This will enable further economic diversification and add more value to existing areas of economic specialisation. All this will require effective local and regional governance and strong multi-level governance relations.

Introduction

This chapter provides a summary of the main strengths and challenges Gotland faces at the regional level. It takes stock of the main trends observed on Gotland and compares these to other similar OECD islands and rural territories. The chapter comprises three main sections. It begins by presenting an overview of the geographic and settlement context in the region. It then looks at the economic performance on Gotland and its level of well-being over the past years including during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, with that of comparable OECD regions. The chapter then examines the enabling factors that can enhance well-being in the region.

To better compare the performance of Gotland against relevant regions (see full list in Annex 4.A), the analysis in the chapter makes use of two benchmarks, one based on comparable islands and a second based on remote regions:

The islands benchmark is made up of seven islands of similar administrative level (TL3). Each island has its own particular characteristics (surface, population, geography) but also faces similar constraints and characteristics as Gotland. The islands include EU medium-sized islands within the EU islands classification:

The islands of Åland, Finland.

Bornholm, Denmark.

Chios, Samos and Zakynthos, Greece.

The islands of Lewis and Harris, and Orkney, United Kingdom.

The remote regions benchmark is developed to explore the challenges Gotland faces based on its low level of accessibility, and therefore similar in characteristics to a remote region. It consists of a benchmark of 40 regions from 8 countries. The complete list is in Annex 4.A. In order to select the regions, a three-step methodology was used:

Select regions with the same rural typology as Gotland (non-metropolitan remote regions, or NMR-R, according to the revised OECD classification – see also Annex 4.B).

Select regions within 50% above and below the population of Gotland (demographic criteria).

Select regions within 50% above and below the surface area of Gotland (surface area criteria).

In addition, benchmarks against the national average and OECD average are also conducted for select indicators:

The national average compares to the national average in a certain number of indicators, to understand the performance of a region relative to other regions in the country, its strengths and weaknesses.

The OECD country average aims to put into perspective Gotland’s performance in relation to all TL3 regions from the OECD’s 38 member countries.

Gotland location, geographic conditions and settlement patterns

Geographic characteristics are unique on Gotland

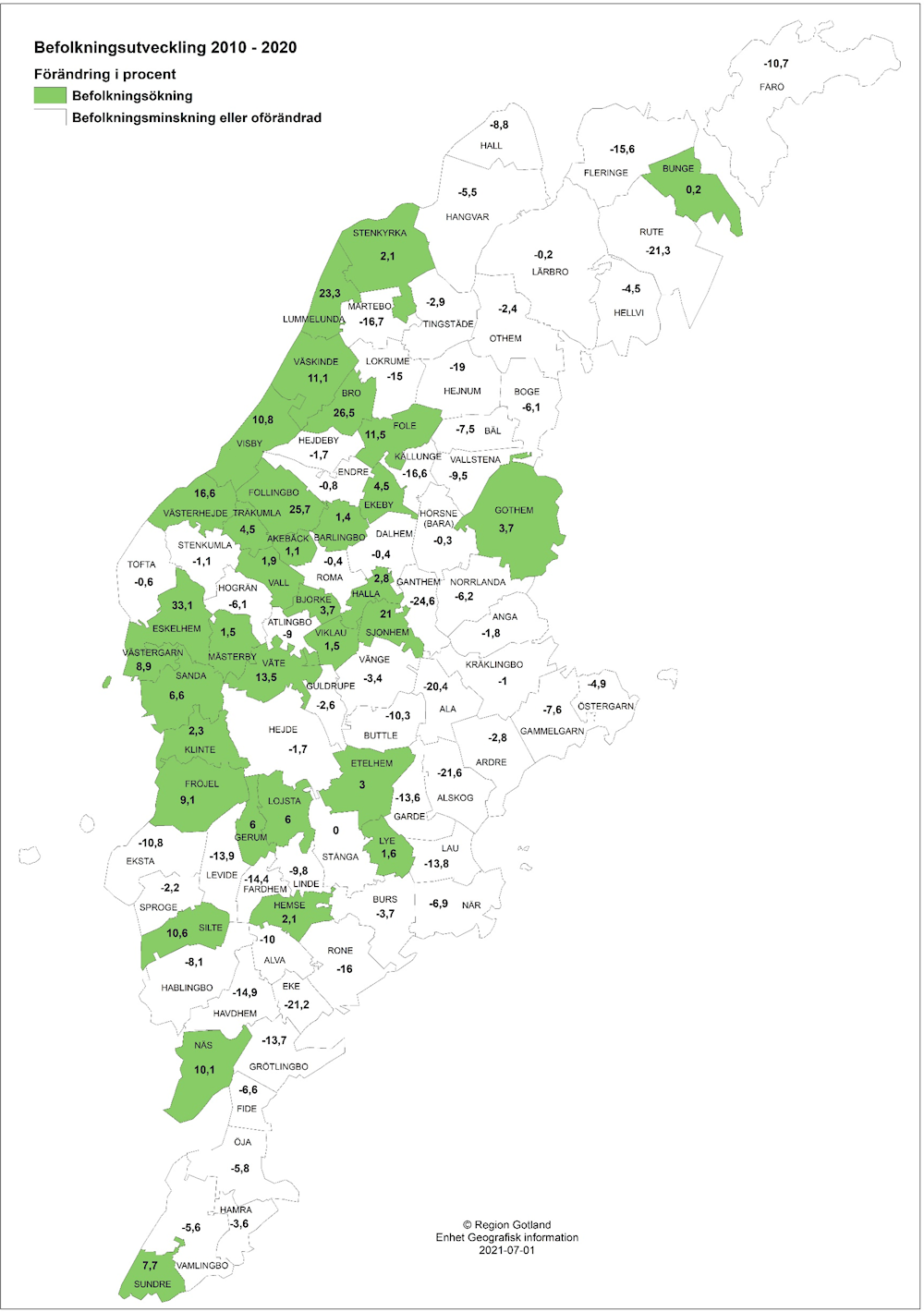

Gotland is a unique territory in Sweden. While the country has numerous islands and long coastal lines, the region of Gotland is by far the largest island and is located the furthest from the mainland. Gotland is also the largest island in the Baltic Sea (3 140 km²). It represents only 0.8% of Sweden’s land area, slightly smaller than the region of Stockholm. With a population of about 60 970 (Statistics Sweden, 2021[1]), Gotland is the least populated Swedish region.2 It is located in the centre of the Baltic Sea (Figure 1.1). The distance to mainland Sweden is about 90 km. If measured according to the ferry locations, from Gotland’s main city Visby, distances are about 150 km to Nynäshamn, 120 km to Oskarshamn and 100 km to Västervik. About 150 km separates the fishing port of Herrvik in eastern Gotland from the coast of Latvia. Gotland’s population density (population per square kilometre) is lower than the national average (19 compared to 24) (Region Gotland, 2021[2]). Apart from being an island, it is also a predominantly rural remote region according to the OECD TL3 revised typology (see Annex 4B). Visby is home to about 26 000 inhabitants and concentrates a large share of jobs, infrastructure, trade and services of the island. Close to 60% of Gotlanders live outside Visby.

Along with significant governance and service delivery responsibilities relative to its population size and administrative capacity, Gotland enjoys a strong cultural and regional identity built through history and local conditions, a rich environmental ecosystem and one of the most important limestone reserves used for cement production in Sweden (SGU, 2018[3]).3

Figure 1.1. Gotland’s location in the Baltic Sea

Source: Own elaboration with PowerBI with data from Statistics Sweden (2021[4]), “Gotland - minskad arbetslöshet”, https://tillvaxtverket.se/statistik/regional-utveckling/lansuppdelad-statistik/gotland.html?chartCollection=8#svid12_a48a52e155169e594d5b3e6.

As an island, Gotland faces a number of specific challenges and opportunities

Insularity determines the development trajectory of islands – Gotland is no exception. Insularity describes a phenomenon of permanent physical discontinuity and peripherality deriving from particular geomorphological conditions in connection to specific social, cultural and economic factors (see Box 1.1). Economically, islands often depend on primary sector activities (e.g. agriculture and fisheries), hyper‑specialisation (e.g. either in the primary or the tertiary sector) or seasonal activities (e.g. tourism). In general, long-term development perspectives are fragile even on high performing islands, because of the predominance of low value-added activities based on the exploitation of often-scarce resources (ESPON, 2013[5]). Overall, islands often face less favourable conditions for economic growth and general well-being than the mainland. On many islands, incomes tend to be lower, infrastructure and services costlier, investment more demanding and means of transport poorer. In addition, many islands suffer from a limited supply of resources such as water, energy, living space and arable land (CoE, 2005[6]).

These bottlenecks and a lack of economic diversity accentuate the vulnerability of island economies to fluctuations in macroeconomic conditions and to global megatrends (CoE, 2005[6]), which include globalisation, population ageing and migration, technological change (e.g. automation, decentralised energy production and the Internet of Things) and climate change. However, island and rural economies, such as Gotland, are also endowed with valuable means to tackle these challenges, such as strong local identities and an abundance of natural resources (OECD, 2020[7]).

Table 1.1 provides an overview of possible vulnerabilities and potential opportunities facing island economies, including Gotland.

Table 1.1. Challenges and opportunities facing island economies

|

Themes |

Challenges |

Opportunities |

|---|---|---|

|

Economic |

|

|

|

Environment |

|

|

|

Social and institutional |

|

|

Source: OECD (forthcoming[8]), “Island economies”, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Box 1.1. Characteristics of island economies

Islands are a key feature of the national territory of many countries. In the OECD, Sweden (267 570 islands), Norway (239 057), Finland (178 947) and Canada (52 455) have the most islands (WorldAtlas, 2021[9]). In the EU, islands account for over 20.5 million inhabitants, about 4.6% of the entire population of the EU-27 (Haase and Maier, 2021[10]). In the case of some European countries such as Greece, Italy and Spain, these constitute up to 20% of their territory with up to 12% of their population (EU, 2017[11]).

The term “island” is a very wide notion1 and is not easily defined. The only fixed, shared commonality is the fact that they are surrounded by water. Apart from that, islands differ greatly in many characteristics, such as size, administrative configurations, geographical location (e.g. proximity or remoteness from the mainland) and population size. Despite this, many islands share additional common and specific permanent characteristics that clearly distinguish them from mainland territories (CoE, 2005[6]). These are generally described within the concept of “insularity”. Insularity does not refer merely to a geographical situation but rather to a phenomenon of permanent physical discontinuity and peripherality deriving from a particular geomorphological condition in connection to specific social, cultural and economic factors (ESPON, 2013[5]; Deriu and Sanna, 2020[12]). From the socio-economic point of view, insularity, especially on small islands, includes limitations in economic activity (e.g. tourism), reliance on subsistence economy and in some instances dependence on public subsidies. In addition to their specialised nature and limited diversity of economic activities, many island economies are also experiencing development constraints related to environmental vulnerability, limited local market size and inadequate and/or costly transport links with the mainland.

Overall, there are two main strands of economic analysis connected to islands:2

First, analysis based on the concepts of small scale. The findings highlight that small markets, small pools of human resources, limited capital, etc., are typical of many islands and can become bottlenecks that slow down socio-economic development and hamper the efficiency of public administration.

Second, the challenges related to the geographic position, including issues of peripherality, isolation and remoteness of islands. Thus, the geographic position and nature of the islands, characterised by the concept of insularity, are characteristics identified essentially as a handicap that hinders the ability of these territories to reach the same standards of quality of life, e.g. in relation to the provision of the same or similar level of services and work opportunities offered on contiguous continents (Deriu and Sanna, 2020[11]).

1. Eurostat defines islands as territories having with a minimum surface of 1 km², which are located at a minimum distance of 1 km between the island and the mainland of 1 km, with a resident population of more than 50 inhabitants and no fixed physical link with the mainland (Eurostat, 2018[50]).

2. See for example: Armstrong, H.W. and R. Read (2004), “Small states and island states: Implications of size, location and isolation for prosperity”, in J. Poot (ed.), On the Edge of the Global Economy, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp. 191-223; Baldacchino, G. (2007), “Introducing a world of islands”, in A World of Islands, Agenda Academic/University of Prince Edward Island, Canada, pp. 1-29; Carbone, G. (2018), Expert Analysis on Geographical Specificities – Mountains, Islands and Sparsely Populated Areas – Cohesion Policy 2014-2020, DG Regional and Urban Policy, European Commission; Deidda, M. (2014), “Insularity and economic development: A survey”, Working Papers CRENoS, Vol. 14/07; ESPON (2019), Bridges, Balanced Regional Development in areas with Geographic Specificities; EC (2019), Europe’s Jewels – Mountains, Islands, Sparsely Populated Areas, European Commission.

Source: World Atlas (2021[9]), World Map/World Atlas/Atlas of the World Including Geography Facts and Flags, https://www.worldatlas.com/ (accessed on 13 December 2021); Haase, D. and A. Maier (2021[10]), Islands of the European Union: State of Play and Future Challenges, European Parliament; EU (2017[12]), “European Economic and Social Committee on “The islands of the EU: from structural disadvantage to inclusive territory””, 2017/C 209/02, Official Journal of the European Union; CoE (2005[6]), “Development challenges in Europe’s islands”, https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/X2H-Xref-ViewHTML.asp?FileID=10912&lang=EN; ESPON (2013[5]), ESPON 2013 Programme: The Development of the Islands-European Islands and Cohesion Policy (EUROISLANDS), https://www.espon.eu/programme/projects/espon-2013/targeted-analyses/euroislands-development-islands-%E2%80%93-european-islands (accessed on 13 December 2021); Deriu, R. and C. Sanna (2020[11]), “Insularità: una nuova Autonomia attraverso la cooperazione tra le Regioni insulari euromediterranee”, https://www.sipotra.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Insularit%C3%A0-una-nuova-Autonomia-attraverso-la-cooperazione-tra-le-Regioni-insulari-euromediterranee.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2021).

Gotland has a unique administrative composition

The region is the only one in Sweden that is both a municipality and a region

Sweden is divided into 290 municipalities and 21 counties or regions (TL3). Municipalities and regions have their own self-governing local authorities with different responsibilities. Differently from the other local and regional governments in Sweden, Gotland has both municipal and regional powers, thus being at the same time one of the largest municipalities and the smallest region of Sweden (SKR, 2021[13]). The region and municipality also function on the same budget (Region Gotland, 2021[2]).

Sweden’s municipalities and regions are responsible for providing a significant proportion of all public services. They have a considerable degree of autonomy and independent powers of taxation. Local self‑government and the right to levy taxes are stipulated in the Instrument of Government, one of the four pillars of the Swedish Constitution.4 Gotland’s governance and subnational finance system and responsibilities will be discussed in detail in Chapter 4.

Geography and accessibility determine settlement patterns on Gotland

Gotland’s population is growing slower than the Swedish average but faster than other islands, with uneven settlement patterns across the island

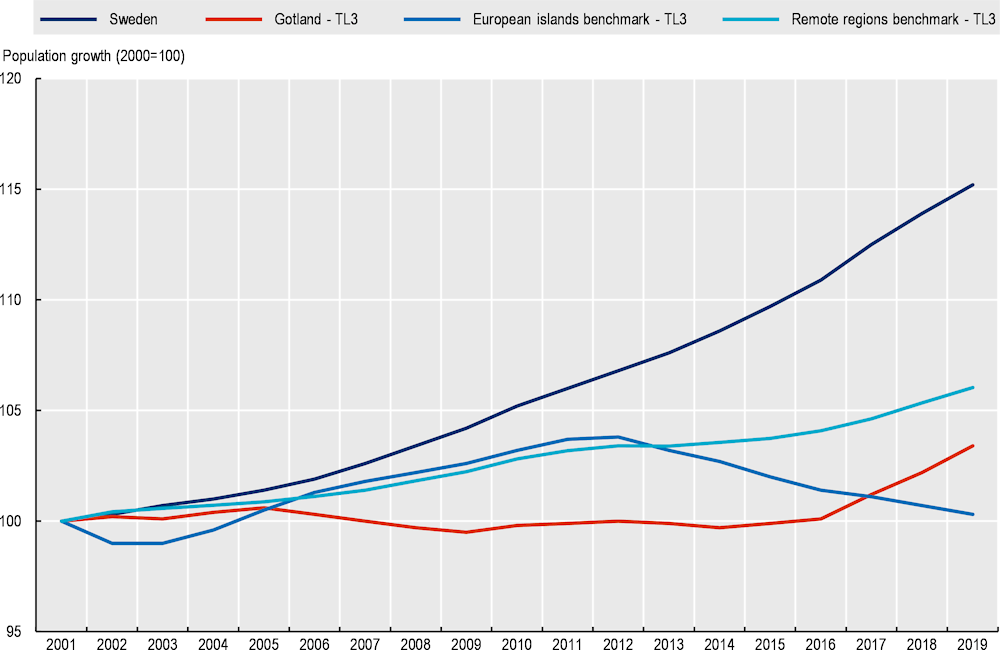

The demographic situation of Gotland is characterised by recent population growth and dependence on (internal) migration. While the population in Sweden as a whole has increased steadily during the last decades, the population on Gotland has been more uneven. The rate of population growth is lower than the Swedish average (3.4% in the period 2001-19 compared with the Swedish average of 15.2%) (Figure 1.2). Since 2014, however, the island has experienced rapid population growth from around 57 000 to 59 700 people in 2019, surpassing 60 000 inhabitants for the first time in 2020 (Region Gotland, 2021[2]).

Figure 1.2. Population of Gotland, TL3 benchmarks and Sweden, 2001-19

Note: The figure represents population growth using the year 2000 as the base year (2000=100).

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

This constant growth that occurred with the recovery from the economic and financial crisis of 2008, has been entirely driven by migrants from other regions of the country, while the natural population growth has been in decline as deaths exceeded birth (Trinomics, 2021[15]). Figure 1.2 also shows that Gotland’s population growth is similar to OECD remote regions but different from European islands. The islands have suffered a sharp decline since the financial crisis and are no further ahead now than they were 20 years ago.

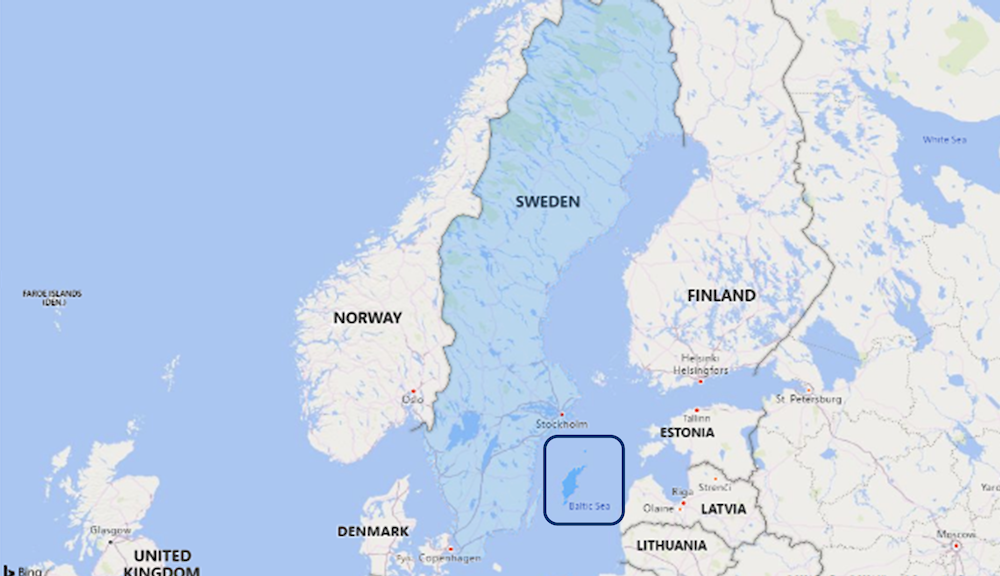

Within Gotland, different settlement trends are present across the different parishes in terms of population growth, with some prospering more than others. Gotland is made up of 92 parishes,5 most of which have a fairly low number of inhabitants. Over 2010-20:

About 59 parishes have declined in population – the largest decreases can be found in Ganthem (‑24.6%), Alskog (-21.6%) and Rute (-21.3%).

Eskelhem (+33%), Bro, (26.5%) and Follingbo (+25.7%) have the highest growth rates (Figure 1.3). In general, the largest increases in population growth can be found on the west coast of the island, in close proximity to Visby. This may be due to the fact that many people live outside but commute to work in the regional capital.

Figure 1.3. Population trends in Gotland’s parishes, 2010-20

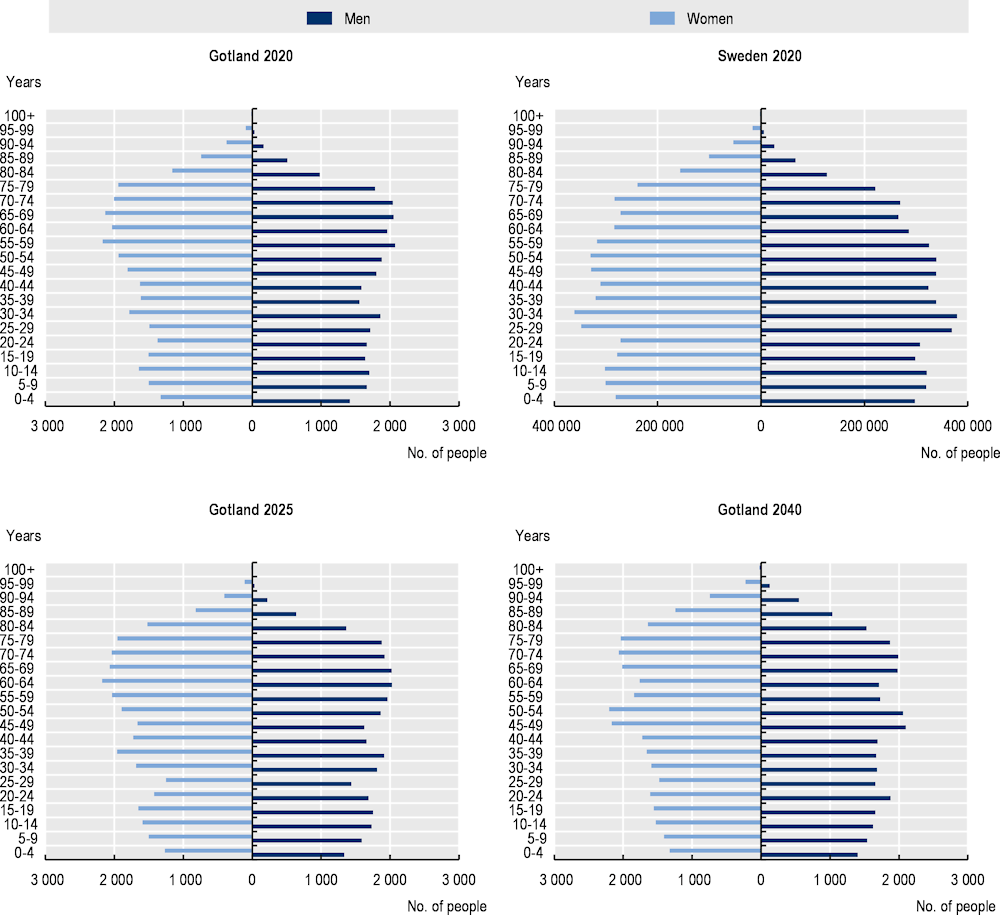

Figure 1.4. Age structure projections for Gotland, 2022, 2025 and 2040, and Sweden, 2020

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

The average age on Gotland in 2020 was 45.2 years and the average life expectancy was 84.3 years for women and 80.6 for men. The share of the elderly population (percentage of population aged 65 or more) was 26.1% on Gotland compared to the national average of 22.1%. Gotland is also the county with the highest share of elderly people in all of Sweden, the region with the fastest growth rate, increasing 4.8% between 2010 and 2020, compared to a Swedish average increase of 2.2% (Statistics Sweden, 2021[17]). Furthermore, during the COVID‑19 pandemic, the size of the non-resident retired/elderly population increased, leading to growing demands on health and community services (Gotland's Project Team, 2021[18]).

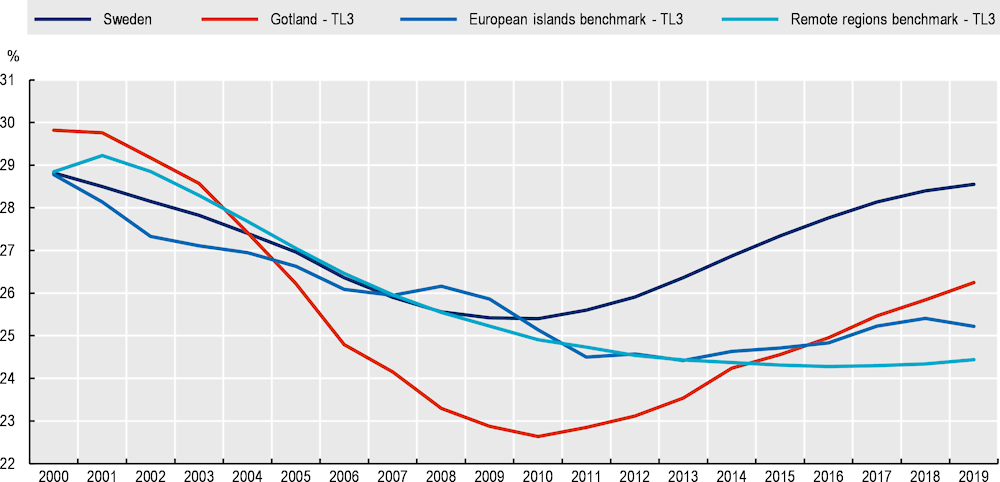

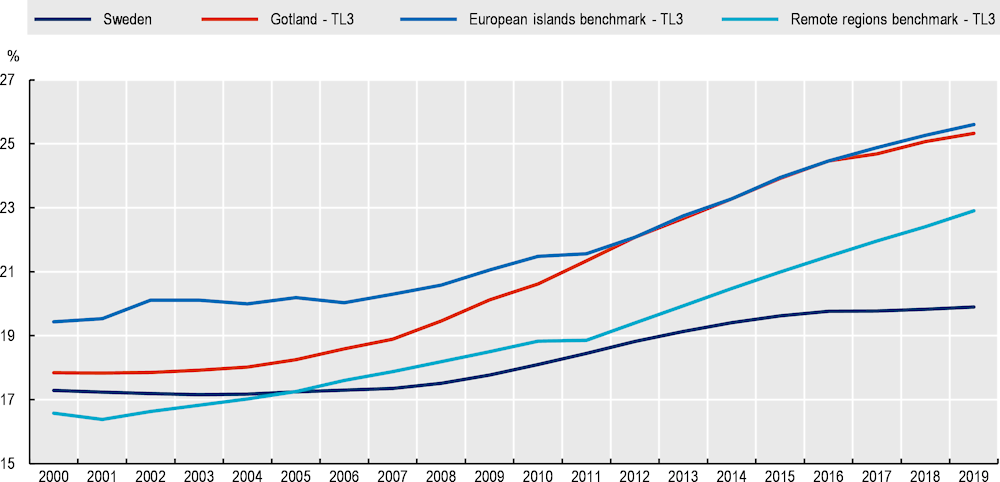

An influx of working-age adults with children (Figure 1.8) has brought growth to Gotland’s youth dependency ratios, which now exceed both island and remote region peers (Figure 1.5). However, Gotland’s population is ageing. Figure 1.6 shows that elderly dependency on Gotland is high and growing, well above the Swedish average and the remote region benchmark, and in line with other island regions.

Figure 1.5. Youth dependency ratio, 2000-19

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

Figure 1.6. Elderly dependency ratio, 2000-19

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

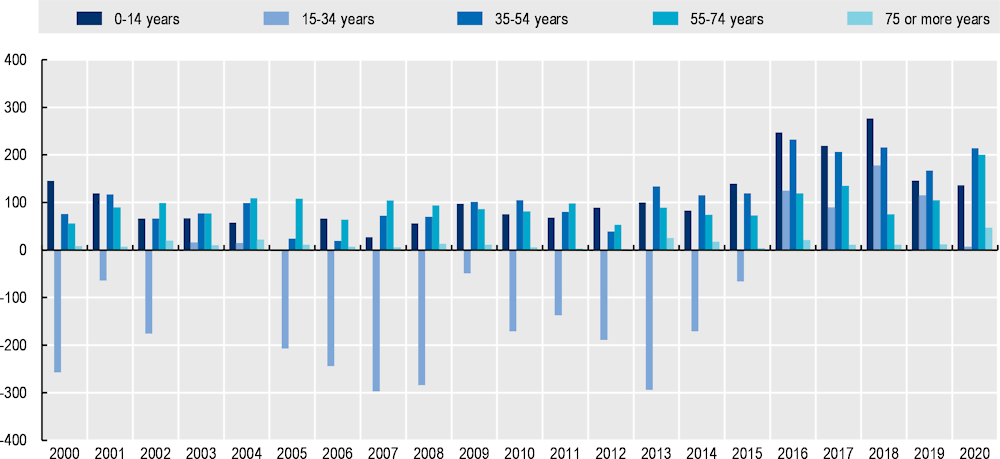

Internal migration results in population growth but the working-age segment is still reducing

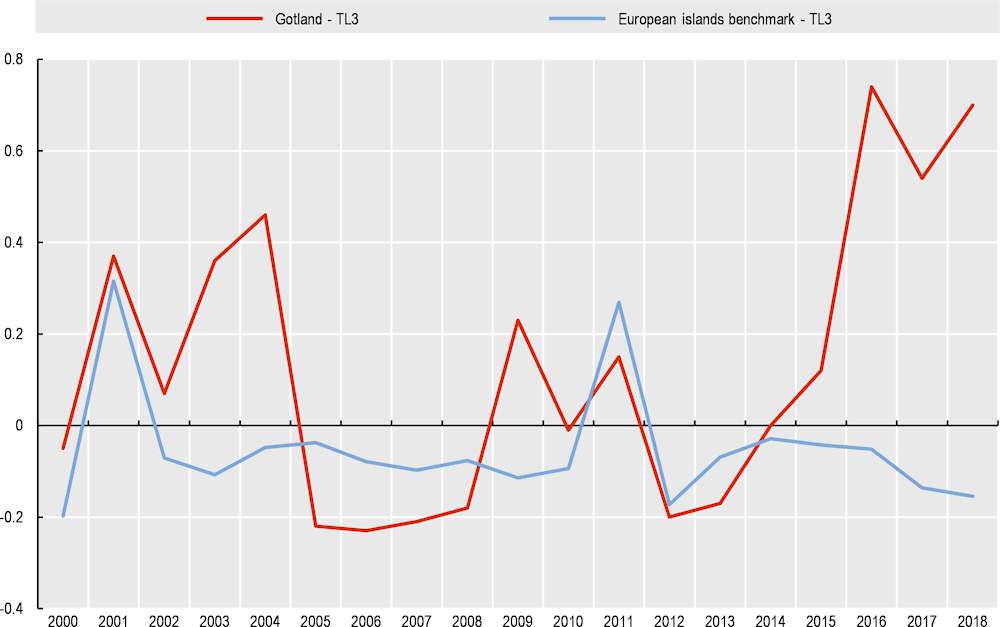

Like in many TL3 island benchmark regions, the (internal) migration trend on Gotland has been uneven in the last 20 years (Figure 1.7). Between 2015 and 2017, a steep increase is visible in migration. This might also be linked to the large number of refugees who arrived in Sweden in 2015 and 2016 and were distributed across the territories.

Although Gotland experienced outmigration in its young adult group (15-34 year-olds) between 2005 and 2015, the flow has reversed across all age groups in recent years. While fewer young adults have been leaving the region, Gotland has also seen a steady inflow of core working-age adults (35-54) with children. At the same time, migration in age groups more than 55 years of age has increased in recent years (Figure 1.8). In 2020, around 2 850 people migrated to Gotland and 2 250 left the island. Domestic migration accounted for almost 85% of the demographic changes. The inflows and outflows occurred mainly to and from Götaland, Skåne, Stockholm, Västra and Uppsala. Foreigners on Gotland are about 9.4% less than the average of Swedish counties, ranked bottom, just after Jämtlands (12.1%) and Västerbotten (13.2%) (Statistics Sweden, 2021[4]) (Figure 1.9). Finland is the most common country of origin for foreign residents, followed by Syria, Germany, Poland and Norway (Region Gotland, 2017[19]).

Figure 1.7. Regional net migration, Gotland and TL3 islands benchmark, 2000-19

Note: The horizontal line shows that the inflow and outflow are equal, and therefore have not produced a migration imbalance. A positive value indicates that the region has a positive migration balance and a negative value indicates that people have left the region to a greater extent.

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

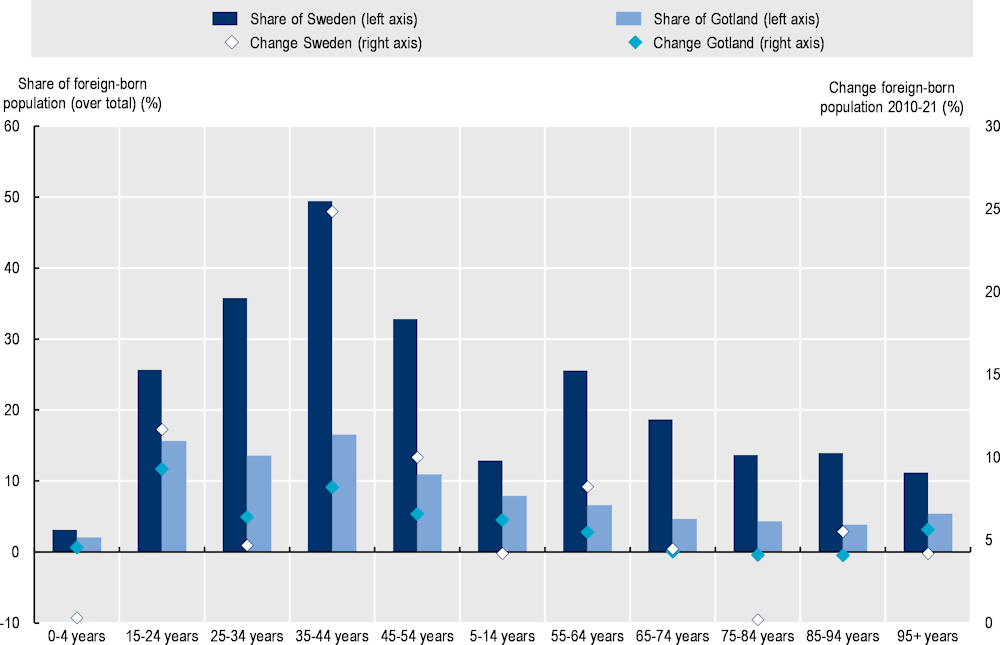

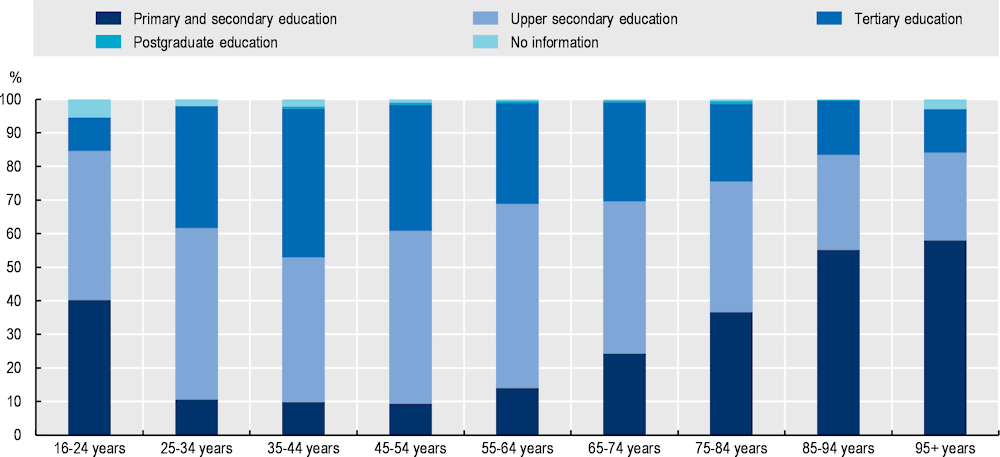

Gotland’s foreign-born population6 in 2020 stood at 5% of the total, 3 times less than the national average (17%) (Figure 1.9). In terms of age groups, the foreign-born population occupies the highest share in the 15-44 age group (9% in the 25-34 age group and 7% in the 35-44 age group). In the case of Sweden, the age group is the same but with much higher shares at around 24% of the population. The age groups in which foreign-born people are least present are the youngest (1 to 24 years old) with 3% of the total and, from 75 years of age onwards, it starts to decrease to 2% of those over 95 years of age who came to settle on the island in the past. The same trend is observed at the country level, with the youngest (3%) and the oldest (7%) having the least weight in the total population.

Figure 1.8. Migration balance by group of age, 2000-19

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

Figure 1.9. Share of foreign-born population over total population and change, Gotland and Sweden, by age group, 2010-21

Note: Each age group (X-axis) has a different share of the foreign-born population (vertical columns on the lefthand Y-axis). Moreover, the change in this share over the last decade is represented by the markers on the graph (righthand Y-axis).

Source: Statistics Sweden (2021[4]), “Gotland - minskad arbetslöshet”, https://tillvaxtverket.se/statistik/regional-utveckling/lansuppdelad-statistik/gotland.html?chartCollection=8#svid12_a48a52e155169e594d5b3e6.

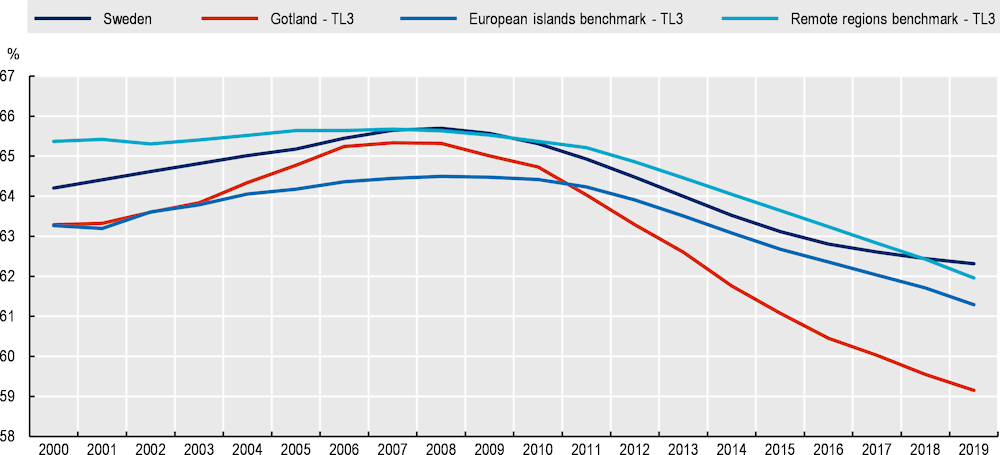

The inflow of many internal Swedish and international migrants has led to an increase in the population but not in the working-age segment. In 2019, the working-age population as a share of the total population has declined in comparison to 2000, from 63.3% to 59.15% (Figure 1.10). According to Statistics Sweden’s latest population projection, Gotland is estimated to reach about 65 000 inhabitants by 2030 and rise to over 70 000 by 2070. The same projections suggest that the decline of the working-age population (15‑64 years) will stop in the next decade and remain stable at around 55% of the population in the following years (Statistics Sweden, 2021[20]). It would therefore seem that the island’s job market may remain in a fairly healthy condition at least for the next years. This, however, depends on the continued trend in migratory flows that are supporting this trend. In fact, according to projections, natural population growth will continue to be negative on Gotland (Trinomics, 2021[15]). Without a steady stream of new arrivals, a decline both in terms of the total working-age population and in absolute terms would be inevitable. The percentage of the elderly population is estimated to rise to around 30% by 2060 and young people will make up 17% of the population in the next 40 years.

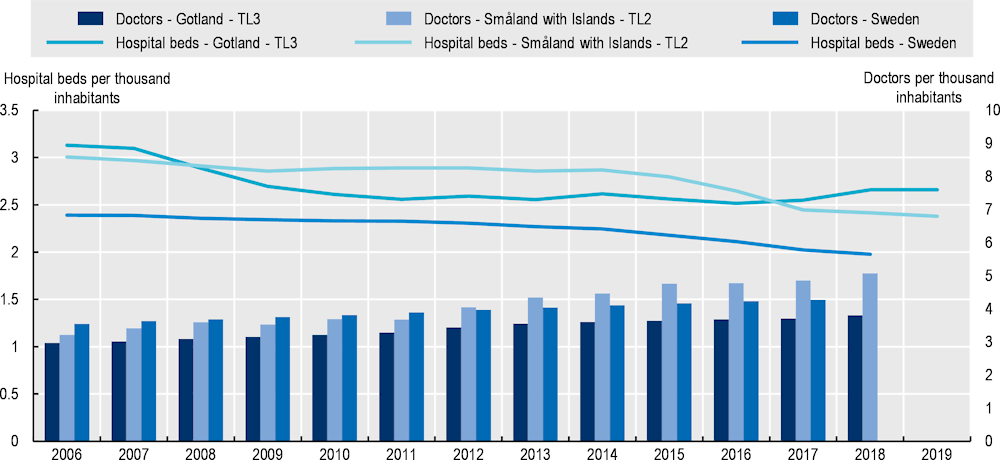

Gotland’s older population profile is likely to create a higher demand for health and other key services in the future. It also results in a smaller potential labour force than other regions in Sweden. Figure 1.9 shows a similar share of the working-age population (15-64 year-olds) over the total population, which amounts to 59% on Gotland, 62% in Sweden, 61% in the TL3 European islands benchmark and 62% in TL3 remote regions. As the proportion of the working-age population decreases, the shortage of labour force will intensify. Already, in 2020, about 24% of employers in the Gotland business community declared difficulties in finding labour with the appropriate skills7 (Region Gotland, 2021[2]). The island’s demographic challenge in terms of the ageing workforce is particularly relevant in some key sectors such as ageing/retiring farmers, teachers, doctors and public administration.

Figure 1.10. Share of the working-age population (15-64 year-olds) over the total population

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

Assessing Gotland’s economic competitiveness

Gotland is lagging in the Swedish context but performing above peer regions

Gotland’s geographic location shapes its settlement pattern and economic performance. As an island economy, it must address the lack of critical mass, remoteness from international markets, higher service delivery costs, seasonality and difficulties in attracting high-skilled labour. Yet, it also contains to its advantage a number of assets including raw materials, a high potential for renewable energy, a high-quality university, a relatively diversified island economy and an attractive location for tourism and migrants (from Sweden and abroad) alike. This section examines the trends in Gotland’s economy and benchmarks these against the national trend and with comparable regions from the island as well as remote locations across a number of economic indicators. The next section will then examine some critical enabling factors that can help raise the competitiveness of the economy and improve the well-being of its island inhabitants.

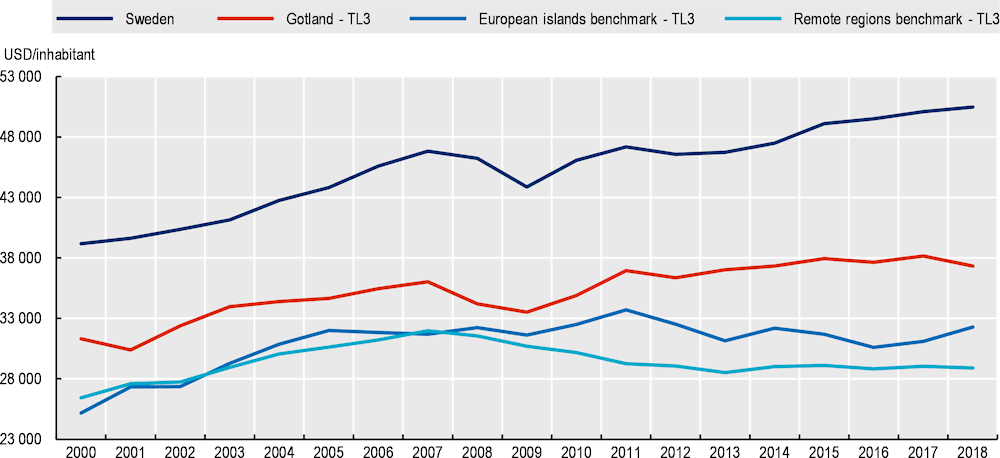

Although Gotland records the lowest GDP per capita amongst Swedish counties in 2019 (Regionfackta, 2021[21]), it demonstrates a good standard of living when compared to the other OECD benchmark regions. The island recorded a GDP per capita of USD 37 323 (purchasing power parity, PPP) in 2018, below the OECD (USD 45 217) and the national average (USD 50 473) but above the level of comparable islands (USD 32 925) and remote regions (USD 28 904) (Figure 1.11).

The gap in GDP per capita with respect to the national average has widened over the past 2 decades, from 20% below the average in 2000 to 26 below in 2018. When compared to peer regions, however, Gotland’s economy has performed well since 2009, its GDP per capita growing on average by 1.2% annually, against a lower rate (0.23%) observed in peer island regions and a contraction (-0.67%) in remote regions over the same time period.

Figure 1.11. Trends in GDP per capita (USD PPP) on Gotland, in Sweden and peer regions, 2000-18

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

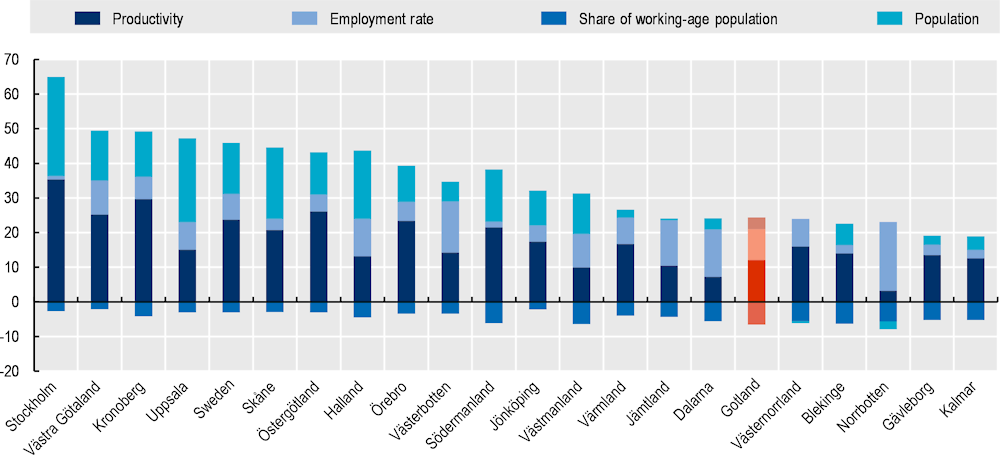

Despite its small size, Gotland’s contribution to GDP growth over the last two decades was above that of five larger Swedish regions: Blekinge, Gävleborg, Kalmar, Norrbotten and Västernorrland (Figure 1.12) (OECD, 2021[22]). A growth decomposition analysis also displays the important role productivity growth played in the growth contribution, followed by gains in the employment rate. In contrast, demographic factors (population growth) had a much lesser role and, in particular, a reduction in the share of the working-age population even had a negative contribution.

Thus, GDP growth is driven on Gotland by a significant increase in productivity (12.1%), followed by the employment rate (8.8%) and, as in the country’s other regions, slowed down by the fall in the share of the working-age population (Figure 1.12). Stockholm, in fact, has productivity values that have pushed GDP growth (35.4%), followed by population growth (28.5%).

Figure 1.12. GDP growth varies considerably across Swedish regions, 2000-18

Note: Data are adjusted for changes in the perimeter of some regions during the period. This has a minor impact on the results.

Source: OECD (2021[22]), OECD Economic Surveys: Sweden 2021, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/f61d0a54-en

Productivity grew faster than in other islands but lags to national standards

A megatrend that is affecting almost all OECD countries alike is population ageing and decline. In order to ensure economic growth remains resilient against this phenomenon and sustainable over the medium and long terms, OECD countries and regions must pay particular attention to productivity in the economy. On Gotland, despite the reduction in the working-age population, productivity has been contributing actively to regional and national GDP growth (Figure 1.14). There is potential to raise it further.

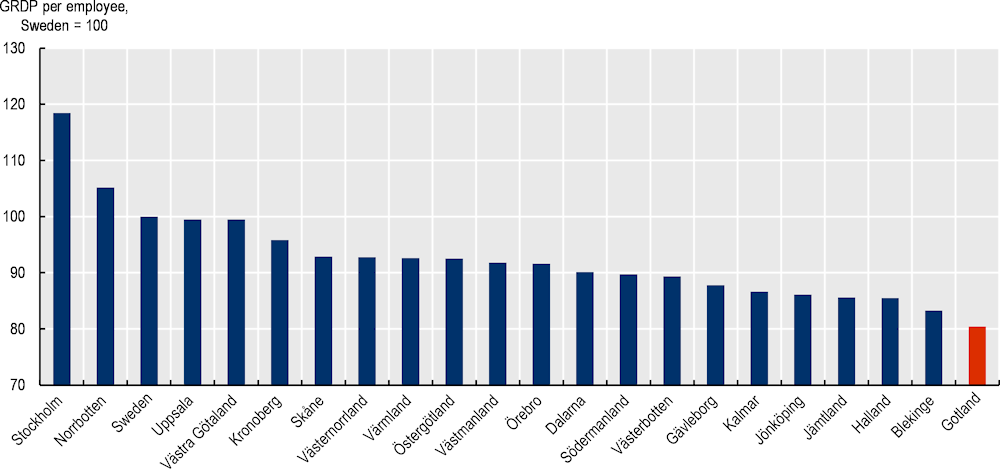

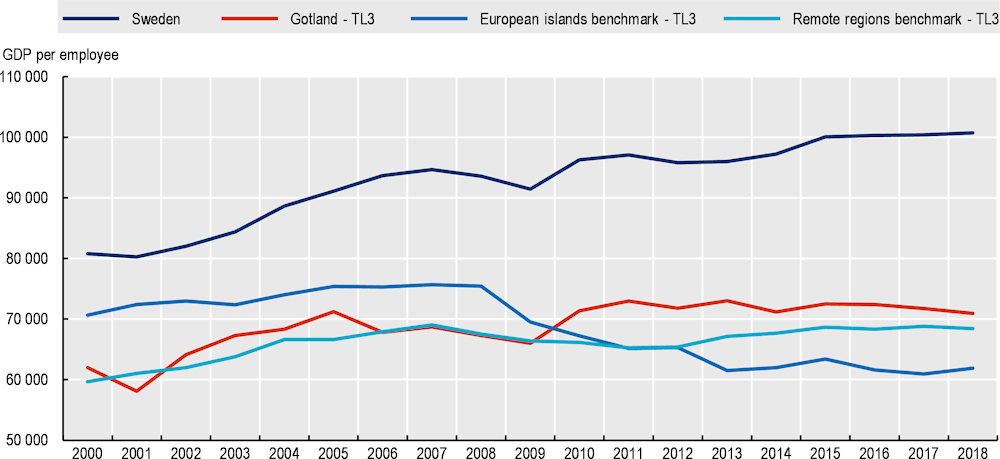

In the national context, Gotland observes the lowest level of labour productivity as a region (Figure 1.13) and, although the gaps with respect to the national level have also increased, from 23% below the national average in 2000 to 30% in 2018, when compared to peer regions, productivity trends on Gotland have been competitive (Figure 1.14).8

In 2001, labour productivity on Gotland was below the average productivity of benchmark European island regions and OECD remote regions. Fifteen years later, it had increased to above the average productivity of both benchmark regions.

Productivity growth since 2009 on Gotland has been above (0.8%) the growth rate of peer European island regions (-1.28%) and peer remote regions (0.33%).

Raising productivity on Gotland will be critical to sustaining high living standards and growth over the medium and long terms. Productivity in regions is driven by a wide range of factors including agglomeration effects, innovation and investment intensity, economic specialisation, skills of the labour force and quality of infrastructures. In this respect, Gotland has the potential to raise productivity by: maximising the potential agglomeration benefits of its capital city Visby; fostering innovation across the entire ecosystem in the region attracting skilled labour by further improving its attractiveness (e.g. in terms of quality of life and services in areas such as health, digital access, family planning, housing, etc.); addressing challenges of seasonality in its labour market; and adding more value to existing areas of economic specialisation.

Figure 1.13. Labour productivity varies significantly across regions, 2018

Note: GRDP: Gross regional domestic product in SEK.

Source: OECD (2021[22]), OECD Economic Surveys: Sweden 2021, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/f61d0a54-en;

Figure 1.14. Productivity on Gotland, in Sweden and TL3 benchmark, 2000-18

Note: Measured as USD, constant PPP, current prices base year 2015, per employee.

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

The next section examines Gotland’s economic specialisation followed by the performance of its labour market.

Despite its insularity, Gotland has a relatively diversified economy

Gotland’s economy in terms of size is relatively small across national and OECD standards. With a total population of about 60 900 inhabitants in the region and the capital city Visby hosting approximately 26 000 inhabitants in 2021, its size of internal markets is relatively small, limiting the potential for reaping agglomeration benefits when considering that OECD functional urban areas start at around 50 000 inhabitants.

This implies that niche markets and tradeable activities are key to raising productivity in the region:

Tradeable activities typically include manufacturing, some service sectors, resource extraction and utilities. Tradeable sectors are those goods and services that are exported to other regions or countries either as final or intermediate goods. Productivity in tradeable activities tends to be larger than in non-tradeable activities across OECD countries and regions. Therefore, they are key activities for remote regions such as Gotland to raise productivity.

Another source of potential productivity can be derived from niche markets. These are differentiated products and markets in which Gotland can specialise and has a competitive advantage. Enhancing innovation in the region can add more value to these activities and hence raise productivity.

Gotland’s economy is highly dependent on the public sector, which contributes to 26% of GVA, and trade and transport (18.2%). The remaining sectors do not each produce more than 10% of GVA, led by industry (9.9%), real estate (7.9%), construction (7.4%), general services (7.4%), manufacturing (6.8%), and agriculture forestry and fishing (6.1%), (Figures 1.15 and 1.17). Amongst these, tradeable activities represent around one-quarter of the regional economy, led by manufacturing and processing of primary sector activities (OECD.stat, 2021[14]):

Food production and processing play an important part in the regional economy and are sustained by a constant flow of investments over time. Just under three-quarters of the island’s surface is dedicated to agriculture and forestry. About 85-95% of food production and processing activities are tradeable, and exported outside the island. For example, Sweden´s largest brand of organic meat Smak av Gotland (Taste of Gotland) is included in Gotland’s abattoirs portfolio. The abattoir is one of the largest industries on the island (in terms of turnover and workplace) and exports about 98% of its beef and pork production to the mainland (a smaller percentage abroad). (Gotlands Slagteri AB/Svenskt Butikskött, 2021[23])Further, many farms diversify their activities, often also operating in the energy and tourism sectors (Region Gotland, 2017[19]). For example, local farm shops had peak years in both 2020 and 2021 (LRF Gotland, 2021[24]).

Non-metallic mineral products, wood and manufacturing industries are also key tradeable activities in the island. In particular, the extraction and processing plants for non-metallic mineral products (e.g. cement and limestone) are important contributors to the island’s economy. Moreover, their contribution has remained broadly stable over time, including during the COVID‑19 pandemic. There are (multinational) mining companies present on Gotland: Cementa, Nordkalk AB and SMA Minerals. The cement production plant in Slite accounts for three‑quarters of all cement used in Sweden and also accounts for an important supply chain linked to the production of cement, spread throughout the island (Region Gotland, 2021[2]; Trinomics, 2021[15]).

Tourism is another important element of Gotland’s economy (Trinomics, 2021[15]). Tourism on Gotland is concentrated in the period from mid-June to mid-August but efforts are being made to extend the season year-round. During the summer, the population of Gotland more than doubles, from about 60 000 inhabitants to 130 000 in July. As in many islands, seasonal variations mean increased traffic congestion and pollution and higher pressure on infrastructure and services (e.g. water, waste management and public transport). They also limit the possibility for many local businesses to maintain qualified workers all year long.

Up to 6 000 people work in the hospitality industry during the summer. They fall to 2 000 in low season but a large number of people are employed in connected activities such as the food and retail sector, transport, construction, and the cultural and creative industries for example. Tourism turnover on Gotland was quite stable before the COVID-19 pandemic, amounting to about SEK 4 000 million per year in the period 2016‑19, compared to SEK 306 000 million in 2019 for Sweden (OECD, 2020[25]). As in other OECD countries, tourism was hard hit during the COVID-19 pandemic. On Gotland, before the pandemic, over 2.2 million people visited the island annually reaching more than 1 million overnight stays. This amount was reduced to 1.3 million visitors in 2020 and guest nights dropped to 724 155 guest nights (Table 1.2). The share of foreign tourist guest nights has remained the same in recent years and accounts for 11% of total guest nights. Foreign visitors primarily come from Denmark, Germany and Norway (CAB Gotland, 2021[26]).

Figure 1.15. Share of Gotland’s economy by activity, 2017

Note: The GVA values for “Other services” correspond to 2015 as there is a statistical error in the data from that year onwards.

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

Table 1.2. Number of passengers and guest nights, 2017-20

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Passengers |

2 240 131 |

2 235 885 |

2 269 138 |

1 358 034 |

|

Guest nights |

1 004 876 |

1 002 751 |

1 025 521 |

724 155 |

Source: CAB Gotland (2021[26]), Regional Housing Market Analysis Gotland County 2021, https://www.lansstyrelsen.se/download/18.1d275504179f614155f3c07/1627887471773/BMA%202021.pdf.

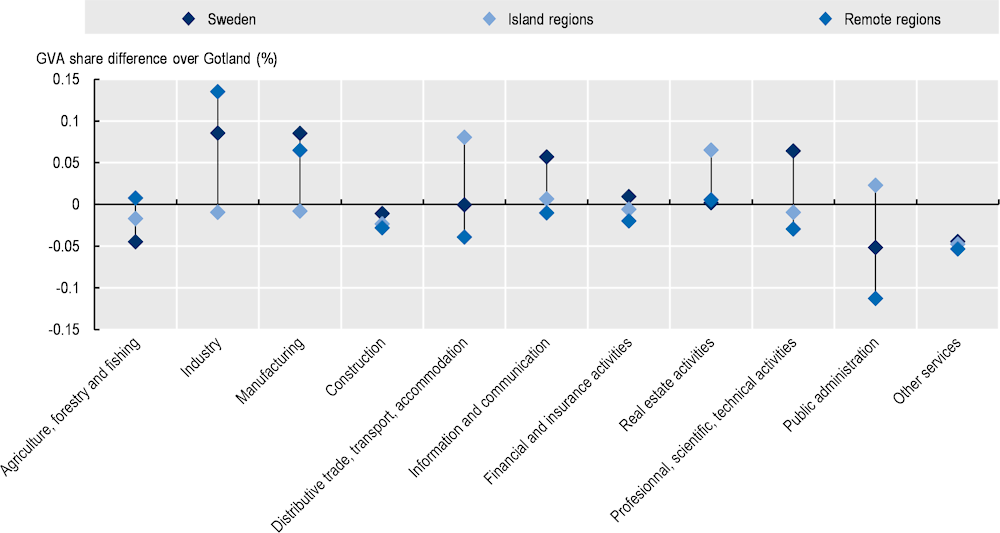

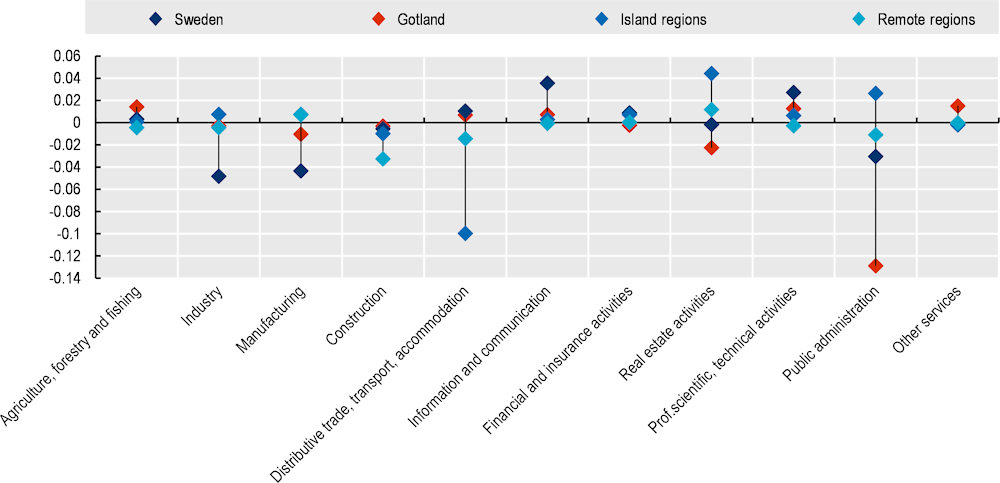

An analysis of economic specialisation reveals that Gotland is highly specialised with respect to Sweden and peer regions from islands and remote places, in construction and in other services (Figure 1.16):

When compared to Sweden and as expected, Gotland is more specialised in agriculture, forestry and fishing, public administration and other services, and less specialised in industry, manufacturing, information and communication, financial and insurance activities and professional scientific and technical activities.

When compared to peer island regions from the EU, Gotland is more specialised in agriculture, forestry and fishing, financial and insurance activities, professional scientific and technical activities, and a bit more specialised in manufacturing and industry. In contrast, Gotland is less specialised in distributive trade, transport, accommodation, information and communication and real estate activities.

When compared to remote regions, Gotland is less specialised in industry, manufacturing, agriculture, forestry and fishing but more specialised in the remaining sectors.

Figure 1.16. Specialisation on Gotland with respect to Sweden, island and remote regions, 2017

Note: Above the value of 0 indicates a higher level of specialisation on Gotland with respect to Sweden, island and remote regions. Industry includes the mining sector.

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

Figure 1.17. Change in the structure of the economy (GVA change), 2017 compared to 2005

Note: The GVA values for the category ‘’Other services’’ correspond to 2015 as there is a statistical error in the data from that year onwards. The calculation is based on the GVA of 2017 over 2005 in USD, constant prices, constant PPP, base year 2015. For a definition of what real estate includes, see https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/seriesm/seriesm_4rev4e.pdf.

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_ECONOM.

The analysis also reveals that despite the high reliance on the public sector, which contributes to 30% of GVA, this specialisation is similar to peer island economies from the EU. Nevertheless, the benchmark with remote regions reveals they are less specialised in public administration than Gotland.

The trends over the last 15 years reveal consistency in Gotland’s specialisation in agriculture, distributive trade, scientific professions as well as other services have experienced small increases. This stands in contrast to public administration, which experienced a sharp fall. This suggests that despite its high reliance on the public sector, the region is gradually becoming less reliant on public activities.

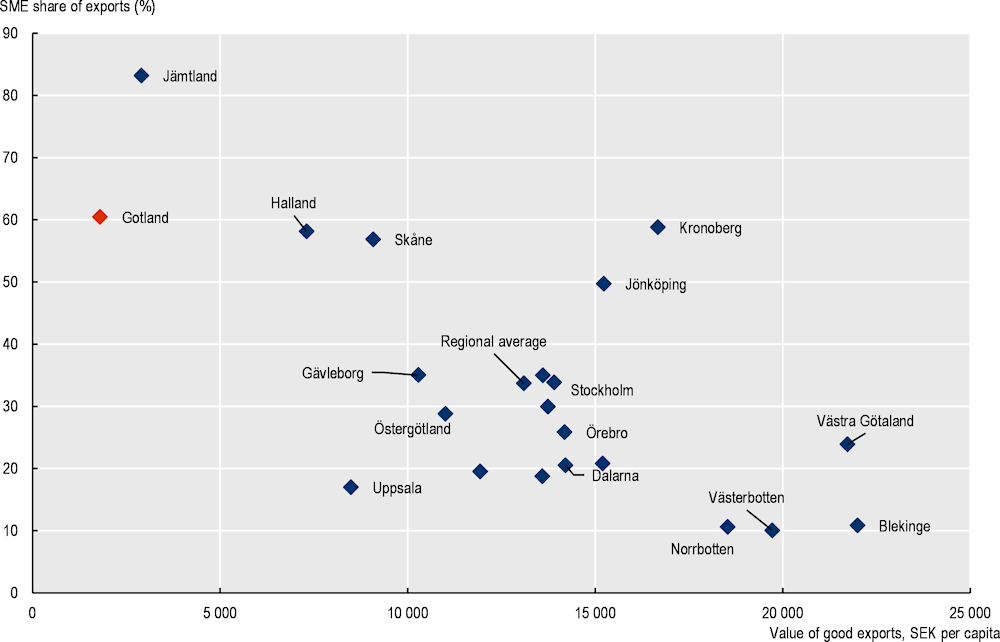

Gotland’s SME share of national exports (60%) ranks second after Jämtland (83%) in 2018, demonstrating the importance of SMEs to the island. Nevertheless, Gotland’s limited size and export capacity make it, in per capita terms, the Swedish region that exports the least (SEK 17 990 per capita, far from the country’s regional average of SEK 130 960) (Figure 1.18).

Figure 1.18. Goods export in Swedish regions, 2018

Note: Goods export value per inhabitant in SEK thousands in 2018 distributed by workplace, divided by county. The proportion of goods export value in different counties in 2018 that comes from SMEs (0–249 employees).

Labour market trends

Unemployment on Gotland is well below the national average

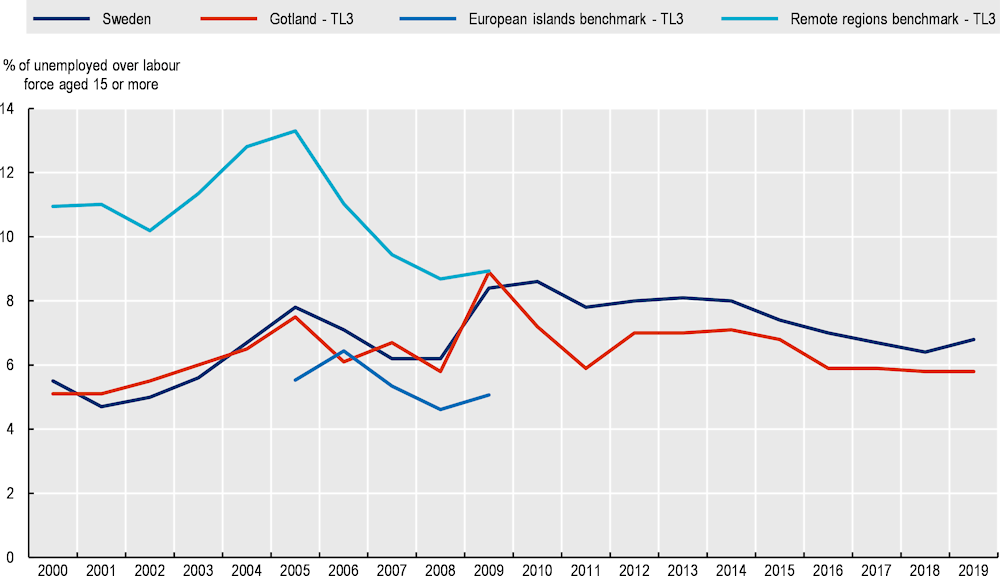

The labour market on Gotland is defined by small-scale but reasonably diversified sectors. Also, a large part of the labour market is seasonally defined, expanding during the summer months and shrinking in the winter. Unemployment on Gotland has remained stable over the past 15 years, fluctuating between 6-8% and peaked during the 2008 global financial crisis. This rate and its trend over time were in line with the Swedish rate of unemployment. In relation to benchmark regions, before the global financial crisis, Gotland recorded lower rates compared to peer remote regions, while they were slightly higher compared to peer EU island regions.

Figure 1.19. Unemployment rate, 2000-19

Note: Islands and remote regions benchmarks only available up to 2009, Gotland up to 2016. The value for 2019 has been added using unemployed population data from Eurostat data and working-age population from the OECD database.

Source: OECD.stat (2021[14]), Regional Economy (database).

The labour market on Gotland is diversified but small and seasonally dependent

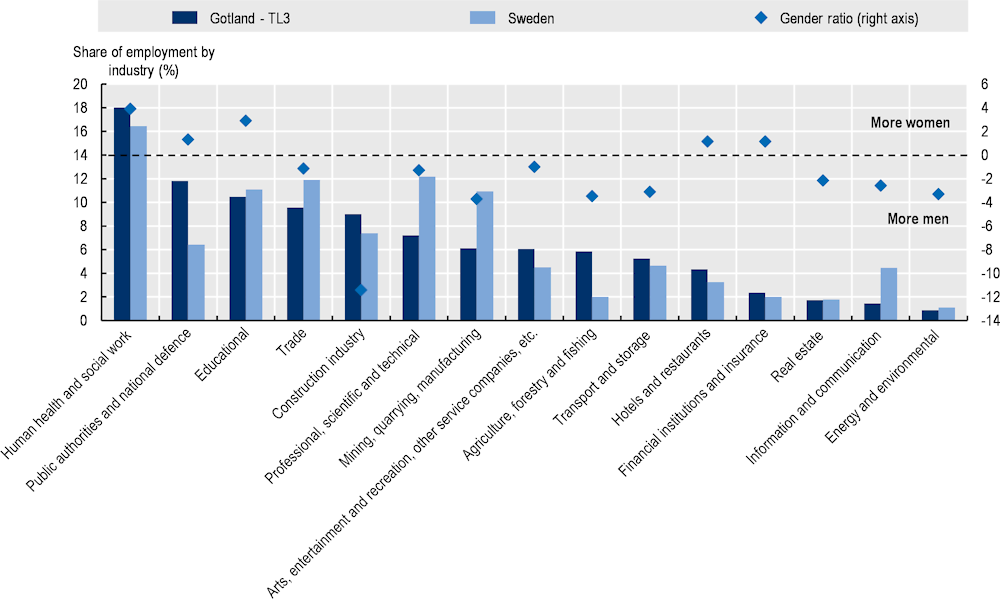

In terms of employment, the employment rate for 15-74 year-olds on Gotland in 2016 (63.3%) was below the national average (67.1%), with the public sector accounting for a large share of employment (Figure 1.20) followed by trade and construction. Agriculture and forestry, non-metallic mineral products and wood and manufacturing industries are smaller but important contributors to overall employment in the region. The largest employers include Region Gotland, the Swedish Social Insurance Agency, Cementa, Payex AB and the Swedish Armed Forces (Region Gotland, 2021[2]).

The tourism sector is highly seasonal, creating about 4 000 extra jobs during the summer months (OECD, 2020[25]). Managing this seasonality to meet the summer tourism demand represents a policy challenge. Although summer students can pick up part of the job demand, attracting sufficient temporary workers from outside is always a challenge, considering the scarcity of affordable rental housing in summer.

In terms of participating in the labour market, the traditionally male-dominated sectors are also present on Gotland with higher male participation in the construction industry, mining, quarrying and manufacturing, agriculture, forestry and fishing and transport and storage. In line with this, the traditionally female-dominated sectors are also present on Gotland, especially health, social work and education (Figure 1.20). More can be done to support women to move into private sector jobs. In terms of youth aged 18-24, those not in education, employment or training amounted to 3.2% on Gotland against 3.9% nationally, and those participating in active labour market programmes on Gotland were 8.8%, higher than the national average of 6.5% (Region Gotland, 2017[19]).

Figure 1.20. Employment by Industry and gender balance, Gotland and Sweden, 2020

Note: The gender ratio shows the number of times that there are more workers of one gender over the other. That is, negative values show that there is a higher proportion of male workers over female workers. Positive values imply a higher value of female employees in the sector.

Source: Statistics Sweden (2021[4]), “Gotland - minskad arbetslöshet”, https://tillvaxtverket.se/statistik/regional-utveckling/lansuppdelad-statistik/gotland.html?chartCollection=8#svid12_a48a52e155169e594d5b3e6.

Enablers for regional well-being

Megatrends like globalisation, population ageing and migration, as well as technological and climate change create challenges but also new opportunities for regions and territories that will be able to adapt and equip themselves adequately. Rural economies are experiencing increased competition from less developed countries as the offshoring of manufacturing jobs to emerging economies with cheaper labour costs has gradually decoupled the production of tradeable goods away from central locations. Furthermore, the shift to a service economy has more largely benefitted cities, while most rural regions are still over-specialised in traditional primary activities (OECD, 2020[7]). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a profound process of rethinking the organisation of production systems, trade and supply chains, as well as the provision of services and the utilisation of new technologies, globally, regionally and locally (OECD, 2020[7]).

Innovation and entrepreneurship

Gotland is an island of entrepreneurs, yet most stay small and the share of young entrepreneurs and research and development (R&D) expenditure is low

Innovation is today a major driving force for economic growth and competitiveness in the OECD. Rural regions can benefit from a broader perspective of innovation by creating ecosystems that encourage new practices and ideas in a wider range of activities (R&D and investments in technology are important but the concept of innovation is wider) (OECD, 2020[7]). Innovation strategies should support a wide range of collaboration and partnerships among public, private, not-for-profit and educational organisations to foster regional and local specialisation and competitiveness. Regions that host tradeable industries in extractive activities, agriculture and tourism, such as Gotland, should focus their policy on fostering the access of local firms to global value chains, facilitating knowledge sharing to encourage collaborative innovation and providing local businesses and the labour market with the required skills and physical and soft infrastructure (OECD, 2020[7]).

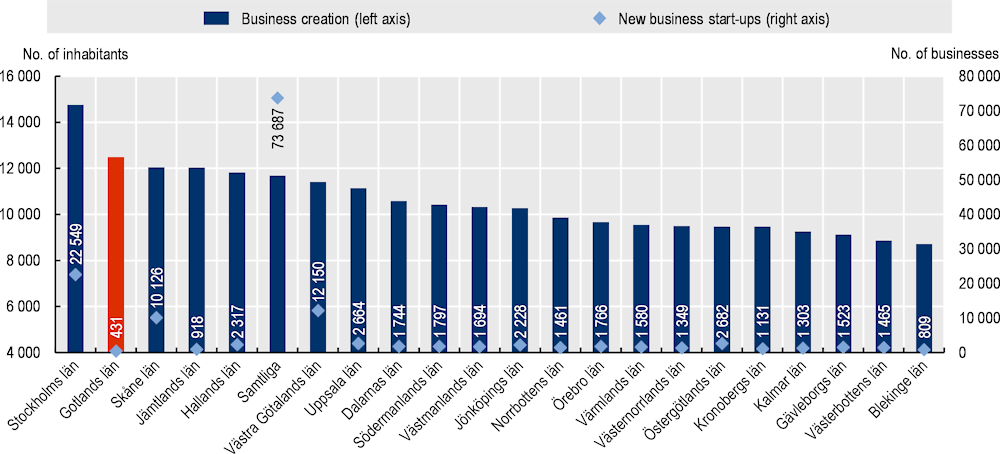

Gotland is high in entrepreneurial spirit. Between 2019 and 2020, around 430 businesses were started each year. Adjusted for population, the county has the second-highest share of start-ups (Figure 1.21). Despite that, it has the lowest rate of young start-up founders compared to other countries, with a rate of only 20% under 31 years of age, compared to the Swedish average of 25% in the same age bracket. Furthermore, a larger than average share of start-ups is founded by those over the age of over 50 (31% against 24% nationally).

Most enterprises on Gotland are founded by Swedish citizens (85%), one of the highest in Sweden. Many urban places such as Skåne, Stockholm and Västmanlands have higher numbers of start-ups by foreign-born, likely due to the higher number of migrants. Regarding female entrepreneurship, Gotland compares well to other counties and ranks slightly above the Swedish average of 32%. However, there is ample room for improvement given that only about 33% of start-ups on Gotland were women-led in 2020 (Tillväxtanalys, 2021[28]). Similarly, Gotland could do more to profit from young, female, migrant and older entrepreneurs and, more generally, from the unemployed or inactive. Further, with regards to the large share of the elderly population on the island, there are considerable opportunities in drawing on the skills of older people for mentorship and advice in terms of entrepreneurship.

Figure 1.21. Total business creation and per capita on Gotland and in Swedish regions, 2020

Note: By gender, the business creation on Gotland has been 33.1% women (183) and 65.6% men (248).

Source: Regionfakta (2021[29]), Newly-started companies per 1000 inhabitants

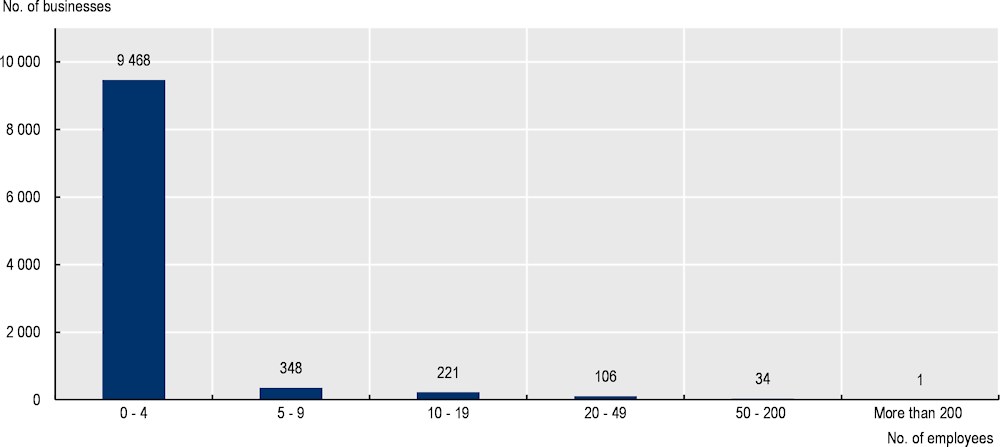

Small and micro businesses make up a large majority of all companies in the municipality of Gotland: 91% (9 468) of all privately owned workplaces (10 178) have 0-4 employees and only 3% have over 50 employees (Figure 1.22). A 2017 survey with entrepreneurs from Gotland indicated that 82% of small business owners demonstrated a willingness to grow with 74% seeing good expansion opportunities. The largest barriers to growth were attributed to the difficulty in finding skilled labour, political uncertainty and the high cost of hiring (Företagarna, 2018[30]).

Figure 1.22. Privately owned workplaces by employees on Gotland, 2022

Note: The figure encompasses the following variables: workplaces, municipality of Gotland, privately owned.

Source: SCB (2022[31]), Statistikdatabasen [Statistics Database], https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

High levels of R&D expenditure are viewed as a vital enabling factor for innovation. On Gotland, R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP is extremely limited. While there is no data on private sector expenditure for R&D, public sector expenditure per GDP stands at 0.03% and higher education expenditure at 0%. This is significantly lower than in many other regions and might also be a reason for limited growth in SMEs.

Land use and housing

Gotland’s geographic and economic characteristics make effective land use even more crucial than other territories.

How land is used affects a wide range of outcomes, from quality of life, such as the length of commute, to the environmental sustainability of urban and rural communities, including the possibility for climate change adaptation and mitigation. Furthermore, the economic importance of land is immense and land use policies play a crucial role in determining land and property prices (OECD, 2017[32]). Gotland’s limited availability of land makes land use a particularly sensitive policy issue.

In Sweden, municipalities have three main responsibilities related to land use. They are responsible for comprehensive planning and the comprehensive plan, which is mandatory and concerns land use. Second, according to the Act on the Housing Supply Responsibility of Municipalities, each municipality must plan for housing supply in the municipality based on established guidelines. The guidelines aim to create conditions for everyone in the municipality to live in good housing and to promote appropriate housing supply measures. Public housing companies can be a means to implement the measures. Third, they provide the technical infrastructure required to develop the land, such as roads and water and sewage disposal networks. In cases where municipalities own land, this gives them the opportunity to directly choose how they want to use it or if they want to sell it for development.

Municipalities are required to develop a comprehensive plan (CP) and detailed plans. The CP sets the strategic framework for the detailed development plan, which is a legally binding instrument setting out rights and obligations regarding the use of land. CPs cover the entire territory of a municipality and form the basis of decisions on the use of land and water areas. Since April 2020, the CP functions as a tool for visionary and strategic decisions that co-ordinate superior national and regional goals, programmes and strategies. The plan-making is supervised by the national government through the county administrative boards (CABs). CABs check the compliance of CPs with national guidelines (such as areas of national interest) (OECD, 2017[32]). Gotland is in a unique position regarding the CP process. As an island, Gotland has no need to consult with neighbouring jurisdictions to co‑ordinate and harmonise their CPs.

This system has been described as imbalanced between actors, top-down and disincentivising active land use planning because local planners are often unclear about which national interests will be judged by the CAB as prevalent or possible in co-existence. This can cause planners to delegate the decision to space-specific authorisation procedures and discourages planning based on potentials and opportunities, often leaving the wider countryside “unplanned” (Solbär, Marcianó and Pettersson, 2019[33]) . All of Gotland is overlaid by different areas of national interest, including minerals, the airport, energy production, outdoor life, ports, armed forces, natural conservation and cultural protection, and coastal lines. This means that planning for housing space, sewage facility locations, transport routes and development of alternative industries, for instance, almost always encounters areas of national interest. While the designation as areas of national interest does not prevent development per se, it does limit local planning flexibility and often forces decision-making on a case-by-case basis. While activities on these lands that took place prior to designation can continue, it is often very difficult to change land uses in ways that conflict with their designation.

One example of conflicting land use necessities on Gotland is linked to housing, food production and processing. Gotland has the highest area of cultivated and grazing farmland per capita in Sweden. Just under three-quarters of the island’s surface is dedicated to agriculture and forestry. In 2020, about 23% of the farmland was cultivated with certified organic production; 50% of grassland was also organically certified. Furthermore, beef, lamb, pork, poultry and horse farms characterise the landscape of the island (Statistics Sweden, 2021[34]). In this framework, Gotland’s land regulations set that any construction built on agricultural land must be allocated exclusively for agricultural use and not, for example, housing or holiday homes (Gotland's Project Team, 2021[18]).

These examples are illustrative of how spatial and land use planning is closely connected to much broader policy and development agendas. Defining how spaces are used determines if objectives such as producing renewable energy, providing affordable housing, producing food or goods and services can be reached and how. Land use is therefore linked to policy objectives on multiple levels and extends across sectoral issues, involving an ever-wider array of actors in the structure of governance (OECD, 2017[35]).

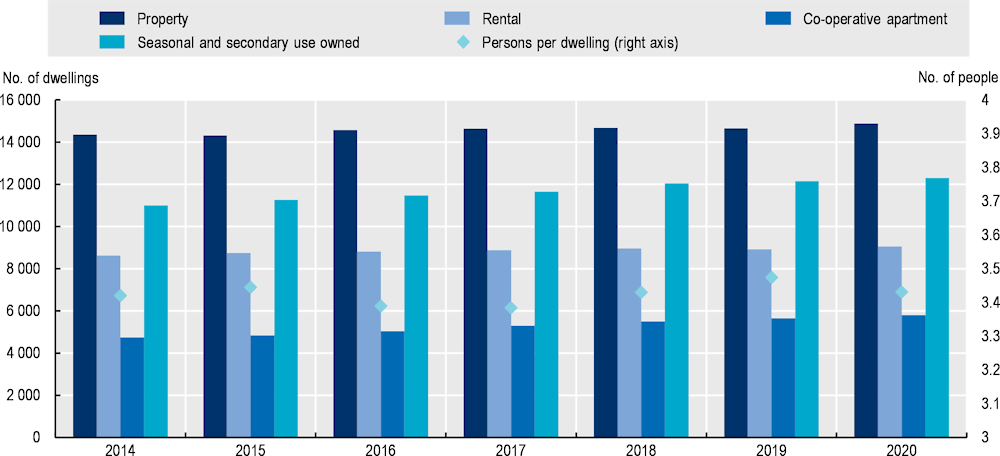

Gotland is experiencing faster price increases in housing than other regions and most new building supplies are holiday homes

The housing stock on Gotland is largely stable and only increasing slowly. The largest housing increases can be observed in seasonal and secondary homes as well as housing that is owned by co-operatives and rented to shareholders (Figure 1.23). This is in line with the data on building permits: between 2010 and 2020, of the 2 184 building permits granted, 1 277 or 58% were for second or holiday homes. Overall, approximately 40% of the total amount of housing is second homes. This is twice as much as the national average (OECD, 2020[25]). The large share of holiday homes directly impacts the housing accessibility of the resident population. Thus, the regions experience an increase in the ratio of persons per dwelling, which stands at 2.4 for Gotland with holiday and second homes, above the OECD average (2.6) and the national average (2.2), but increases to around 3.4 when values for second and holiday homes are excluded (and the housing stock decreases while the population remains the same).

Figure 1.23. Housing availability by type and per capita on Gotland, 2014-20

Note: Dwellings per capita calculation excludes values for second or holiday houses.

Source: Statistics Sweden (2021[4]), “Gotland - minskad arbetslöshet”, https://tillvaxtverket.se/statistik/regional-utveckling/lansuppdelad-statistik/gotland.html?chartCollection=8#svid12_a48a52e155169e594d5b3e6.

The lasting popularity of the island with second homeowners has impacted on the housing market and has fuelled the rise in housing prices (for both purchase and rent). In 2020, Gotland was the fourth most expensive county in Sweden. The average yearly rent per square metre was SEK 1 128 on Gotland and SEK 1 120 for the Swedish average. In addition, prices have increased significantly in the past years, leaving the municipality to rank 5th among the 290 Swedish municipalities in the country with the highest price increase (CAB Gotland, 2021[26]).

Combined with a comparatively low average income, the high housing prices make it difficult even for groups that are generally not considered socio-economically vulnerable to find or afford housing on Gotland. People with little or limited income are even more disadvantaged. Housing affordability can be broadly defined as the ability of households to buy or rent adequate housing, without impairing their ability to meet basic living costs. This also has repercussions on the attractiveness of the island and the ability of the island to attract (or retain) not only much sought-after talent but also other key professionals, e.g. in healthcare, hospitals and schools. Furthermore, the fact that office space on Gotland is the fifth most costly in Sweden often hinders the possibility to hire additional staff, when needed (Gotland's Project Team, 2021[18]).

The presence of many holiday homes and the seasonality of occupancy have also led to the creation of a large amount of short-term rental contracts that exclude the summer months. This is because landlords are able to rent apartments to tourists over the summer at a higher cost than during the rest of the year. Consequently, university students, seasonal workers and other low-income groups have no place to live during the summer when the island is occupied by tourists. For example, out of 497 student apartments, 272 (55%) offer 10-month contracts. For university students, this also means they have limited opportunities to land summer jobs or gain work experience on the island, which could lead to future employment and is much needed from a labour market point of view (Gotland's Project Team, 2021[18]).9 In the long run, this development can also endanger social cohesion (for example, creating friction between wealthy people on vacation and people of the lower middle class, who pays high rents and are not always able to find a stable residence).

Table 1.3. Price change in housing on Gotland, 2020

|

Gotland |

|

|---|---|

|

Price change in percentage in 1 year |

+9 |

|

Price change in percentage in 5 years |

+44 |

|

Price change in percentage in 10 years |

+61 |

|

Price change in percentage in 20 years |

+289 |

Source: Statistics Sweden (2021[17]), “Folkmängd, andel invånare som är 65 år och äldre”, https://tillvaxtverket.se/statistik/regional-utveckling/lansuppdelad-statistik/gotland.html?chartCollection=7#svid12_a48a52e155169e594d5b3e6.

Accessibility (transport and digital) is of central importance to life on the island

Accessibility plays a central role in local and regional development because the quality and mix of infrastructure (transport, services and digital) in a community or region can influence the path of economic development and the perceived quality of life of residents. Furthermore, accessibility to a territory defines the cost and availability of goods and services to be transported to and from that territory. As an island, Gotland depends on effective and efficient connectivity to mainland Sweden and beyond. Yet, the high cost of transport of goods and people limits the potential of island businesses to participate in national and international markets.

Transport infrastructure between Gotland and the national mainland is well developed but comes at a cost, while links to other Baltic neighbours are limited

Good transport options are critical for Gotland’s residents and businesses. By ferry, it takes about three hours to travel to Gotland. Stockholm can be reached by air in 40 minutes. This allows daily trips to and from the national mainland. Visby Airport has regular air traffic all year round and daily connections to Arlanda, Bromma and Stockholm airports. Before the pandemic, there were also regular connections to Gothenburg and Malmö, among other places. In 2018, 2 100 people commuted from Gotland, approximately half of them to Stockholm County; over 1 200 commuted to Gotland, of which half were from Stockholm County. There is a large seasonal variation throughout the year for transported passengers by both ferry and plane (in summer, passengers are almost ten times greater in number than in winter months) (OECD, 2020[25]).

The state is responsible for ferry traffic, which is contracted every ten years by the Swedish Transport Administration (Trafikverket). The ferry service (Destination Gotland) runs between Visby-Nynäshamn (approximately 150 km) and Visby-Oskarshamn (approximately 120 km). The ferries are high-speed vessels and the travel time is just over 3 hours. About 25% of passenger travel goes to the south line (Oskarshamn) and 75% to the northern (Nynäshamn). The transport of goods is evenly distributed on the two lines. The ferries transport both goods and passengers. In 2019, more than 1.8 million passengers travelled with the ferries, of which about a third were Gotland residents. Travelling and transporting goods have continuously increased over the years; however, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to significantly less travel than in previous years. Between January and September 2020, passenger numbers decreased by up to 40% for Gotlanders travelling and 31% for visitors; flights also decreased by 7.4%. 2021 numbers have recovered but are not yet reaching 2019 levels: passenger numbers for Gotlanders especially remain low (Destination Gotland, 2021[36]). Overall, transport is largely linked to mainland Sweden, though a new ferry connection just recently opened to Rostock in Germany. If businesses seek to grow (e.g. fostering internationalisation, broadening export markets and increasing qualified labour force) and the island wants to become more attractive to non-Swedish visitors and migrants, new connections to other Baltic countries will be essential.

Ticket prices for the ferry to Gotland vary depending on the season, line and departure time. In peak season (e.g. Easter and summer holidays), prices can be more than double the off-season price for both Gotlanders and visitors. However, Gotland inhabitants benefit from an annually adjusted maximum price, which is set for residents, resident cars and goods, while standard market pricing applies to visitors (OECD, 2020[25]). Recently, Destination Gotland has announced a 10% price increase from March 2022 because of raised fuel costs caused by a renewed application of reduktionsplikt (or “the duty to reduce”), a national law that aims at reducing gas emissions all over Sweden. This increase may be a critical threshold for all export from the island, especially for the agro-food industry that in parallel is experiencing increased costs for input goods and new peaked energy prices (Gotland's Project Team, 2021[18]).

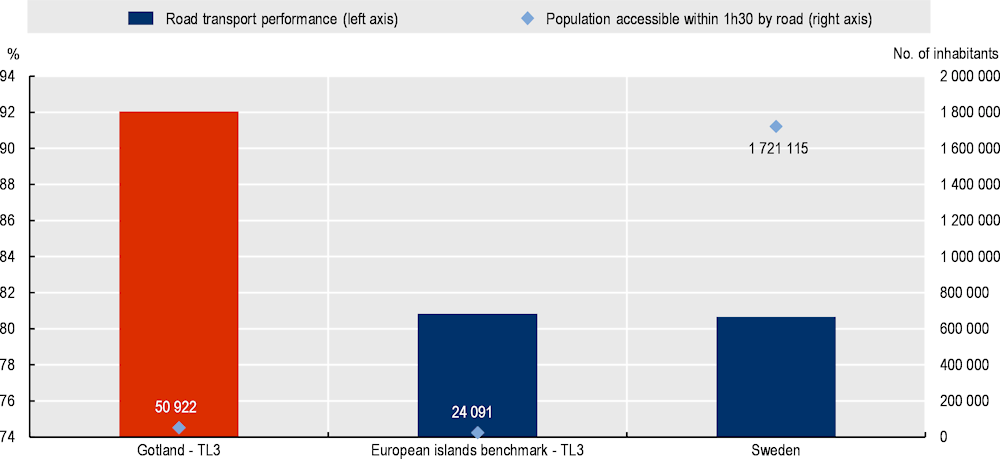

Road transport performance and accessibility on the island are good. Gotland is outperforming both the European islands benchmark as well as the Swedish average (Figure 1.24). Nearly all of Gotland’s population can be reached within a 90-minute drive. Hemse, Slite, Visby and the other towns are important for providing services and jobs. As the largest town, Visby has the majority of jobs and also the most commuters. In 2018, it had a positive net commuting rate of about 5 000 people; just over half of working in Visby also lived there, whilst 2 600 people commuted out of Visby. While about 50% of Gotland’s population can reach Visby in less than 10 minutes by car, about 11% must travel between 30 and 40 minutes and only 1.4% need to travel more than 60 minutes to reach the town. Buses from Visby serve most places within Gotland (Region Gotland, 2018[37]).

Figure 1.24. Road transport performance and population accessible within a 90-minute drive, 2019

Note: The Road Transport Performance is calculated using the following ratio: road_acc_1h5 (number of people who can be reached within a 90‑minute drive from a given location / popl_120 km (number of people living in a 120 km radius of that location) x 100.

Source: Eurostat (2020[37]), Road Transport Performance in Europe, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/working-papers/2019/road-transport-performance-in-europe (accessed on 12 October 2021).

Currently, according to the Swedish Road Administration, national roads count an average of 700 vehicles per day on Gotland in comparison to the national average of 1 500 (Gotland's Project Team, 2021[18]). While road transport performance is good most of the year, dependence on one mode of transportation creates challenges in the summer months, when the population swells and additional visitor cars populate the island, leading to congestion on roads nearby Visby harbour (in connection to ferry arrivals and departures) and close to scenic spots and beaches. To alleviate the problem, the Hanseatic town of Visby, with its small and narrow streets, is closed to cars during the summer and the biking infrastructure in the island is currently being improved.

Gotland is largely car dependent and has the highest share of passenger cars per 1 000 inhabitants in Sweden (Table 1.4). The island also counts the highest proportion of petrol cars in Sweden (76% compared to the national average of 61%). After industry, transport is the sector on Gotland most dependent on fossil energy. This makes the problem of decarbonising transport on the island one of the main challenges for its transition to a sustainable energy system (Swedish Energy Agency, 2019[38]). Overall, there are 35 175 passenger vehicles registered on Gotland, of which 5.5% can be driven on alternative fuels, including electricity (compared to 7.3% in Sweden) (Region Gotland, 2017[19]). Rechargeable electric vehicles make up 0.39% of the public vehicle fleet (compared to 0.55% nationally). Gotland has a relatively well-developed charging infrastructure with around 50 destination chargers. Although petrol vehicles make up the bulk of Gotland’s public vehicle fleet, the region has made numerous investments to increase the use of renewable energy in transport, including setting a requirement for the operation on biogas for buses, taxis, ambulances and garbage trucks. In 2016, there were 511 gas vehicles registered on Gotland, which can be refuelled with locally produced biogas at four locations: two in Visby, one in Alva and one in Lärbro (Swedish Energy Agency, 2019[38]).

Table 1.4. Passenger cars per 1 000 inhabitants, 2020/21

|

Region |

Number of cars per 1 000 inhabitants |

|---|---|

|

Gotland County |

611 |

|

Dalarna County |

584 |

|

Norrbotten County |

570 |

|

Jämtland County |

569 |

|

Värmland County |

554 |

|

Kalmar County |

549 |

|

Västernorrland County |

547 |

|

Blekinge County |

540 |

|

Halland County |

534 |

|

Gävleborg County |

533 |

|

Jönköping County |

525 |

|

Kronoberg County |

515 |

|

Västerbotten County |

504 |

|

Örebro County |

496 |

|

Västmanland County |

495 |

|

Södermanland County |

493 |

|

Skåne County |

476 |

|

Östergötland County |

475 |

|

Västra Götaland County |

461 |

|

Uppsala County |

433 |

|

Stockholm County |

399 |

|

Sweden |

517 |

Source: Regionfakta (2021[39]), Personbilar per 1 000 invånare, https://www.regionfakta.com/gotlands-lan/infrastruktur/personbilar-per-1000-invanare/.

Digitalisation: Broadband connection on Gotland is remarkably good and an advantage for development

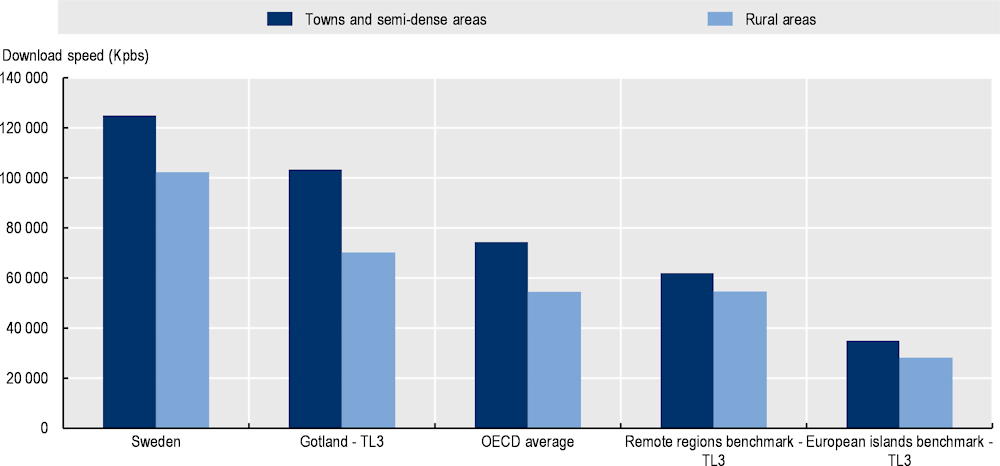

Gotland has a very well-developed fibre optic network throughout the island and occupies a leading position among the regions of the country. In 2020, 88% of the population/households had access to the fibre optic network (Table 1.5). Almost 92% of the permanent population/households have access to the network and just over 60% of all properties with holiday homes. Also, in terms of connectivity speeds, the island compares extremely well. It not only ranks better than the OECD average for all sub-regional categories but also performs better than the remote regions and island benchmarks across the board. In the villages category, Gotland even outperforms the Swedish average (Figure 1.25). Download speeds are increasingly important because online applications require higher data transmission rates. Low transmission capability and speed severely limit access to content-dense applications and websites. As a result, fast stable Internet access has become a necessity for those wishing to benefit from the full economic potential of the Internet (Ibrahim and Bohlin, 2012[40]).

Continuous upgrades to rapidly evolving digital infrastructure will be required to keep places fully connected in the future and ensure Gotland remains at the technological frontier. It is good that it is in the process of expanding its capacity, in terms of both fibre optic and 5G.

Table 1.5. Broadband coverage – Share of households with fixed broadband in 2020

|

Municipality/Region |

Number of households |

Share of households (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Gotland County |

29 168 |

88.0 |

|

Sweden |

4 972 695 |

82.6 |

Source: Regionfakta (n.d.[41]), Bredband via fiber, https://www.regionfakta.com/gotlands-lan/infrastruktur/bredband-via-fiber/.

Figure 1.25. Download speed connectivity by typology, 2020

Note: Kilobytes per second (Kbps) of download speed. Territorial typology based on DEGURBA (EC, 2020[42]). The degree of urbanisation was designed to create a simple and neutral method of classifying areas that could be applied in every country in the world. It relies primarily on population size and density thresholds applied to a population grid with cells of 1 by 1 km. Towns and semi-dense areas consist of contiguous grid cells with a density of at least 300 inhabitants per km2 and are at least 3% built up. They must have a total population of at least 5 000 inhabitants. Rural areas are cells that do not belong to a city or a town and semi-dense areas. Most of these have a density below 300 inhabitants per km2. Cities have not been included they have a population density that does not apply.

Source: Ookla’s Open Data Initiative (2022[43]).

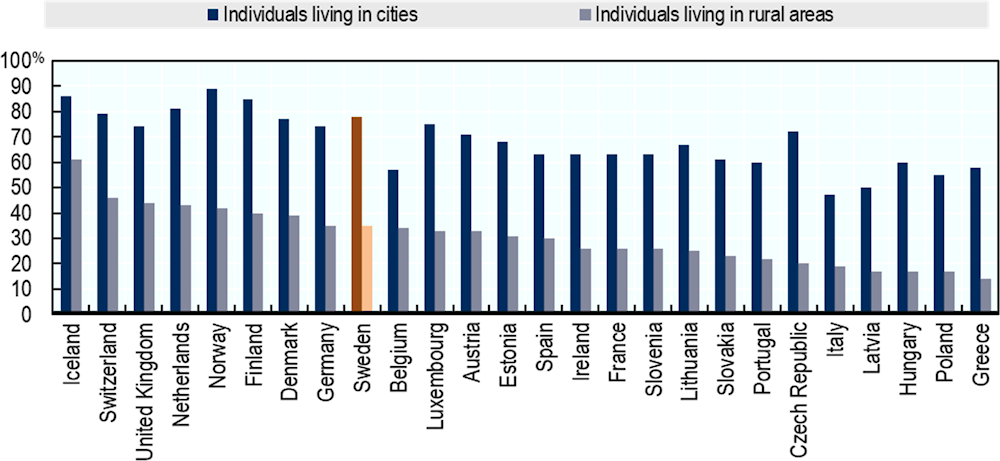

Digitalisation and the use of high-quality broadband are good bases for creating new market opportunities for island communities. They can favour increased productivity, economic growth and access to the most important services such as health and education, and are a highly determining factor in terms of attractiveness because they help to overcome distances and allow for accessibility to services, information and markets (OECD, 2020[7]). However, the development of a solid digital infrastructure for an island such as Gotland does not depend solely on the availability of solid fibre optic or 5G networks. The concomitant presence of other complementary factors is equally crucial, such as having the skills and capability to use these digital technologies. While data on the TL3 level on digital skills is not available, countrywide data shows that individuals living in rural areas often have fewer digital skills than their counterparts living in cities. Digital skills are broadly defined as the skills needed to use digital devices, communication applications and networks to access and manage information.

Figure 1.26. Share of individuals living in rural areas and cities in Europe with basic or above digital skills, 2019

Note: Not all OECD countries are covered by the data source. For further information on the Eurostat classification of areas by degree of urbanisation, see https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/degree-of-urbanisation/background.

Source: OECD (2021[44]), Delivering Quality Education and Health Care to All: Preparing Regions for Demographic Change, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/83025c02-en; EC (2017[45]), The European Social Survey, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cros/content/european-social-survey_en.

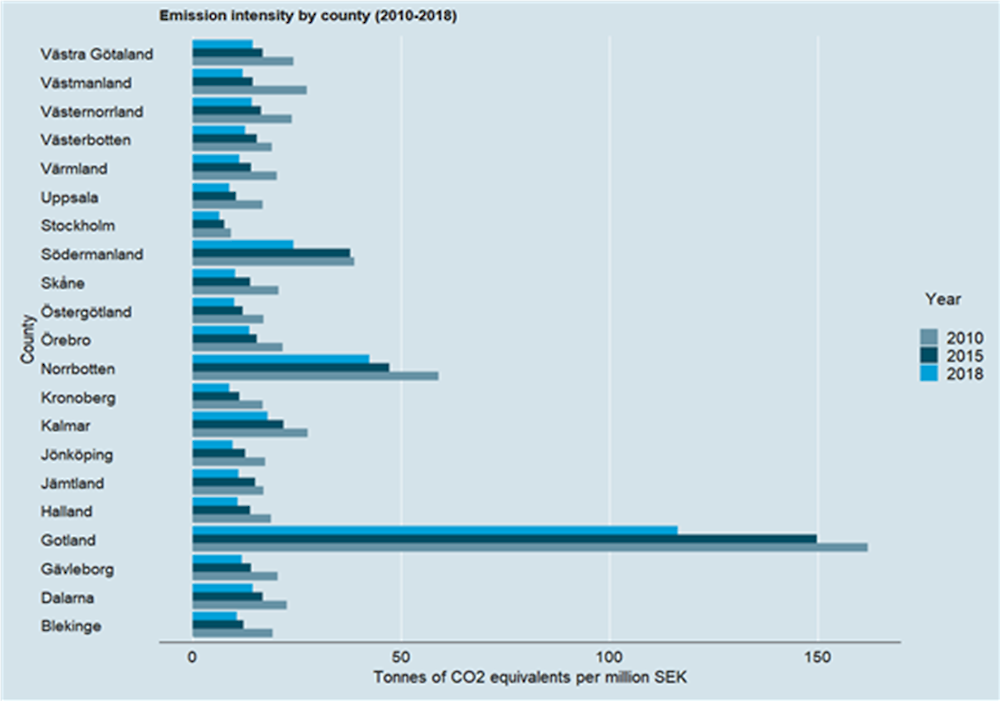

Education and health: Public services are of high quality on Gotland, which adds to the regional attractively but is expensive to maintain