This Chapter focuses on the current status of social accountability in Brazil and seeks to identify ways to improve its implementation within a broader integrated open government agenda. The Chapter outlines the legal, policy and regulatory frameworks in place which underpin the existing institutional arrangement for this type of accountability. It then elucidates the main web of public bodies with a relevant mandate and suggests recommendations to safeguard their autonomy and ensure they can fulfil their assigned responsibilities. Lastly, the Chapter highlights some of the existing initiatives and mechanisms for greater vertical and horizontal accountability and offers ways to take a more forward-looking approach to their implementation, coupled with high-level commitment for improved responsiveness across the public administration.

Open Government Review of Brazil

8. Towards a more accountable and responsive government in Brazil

Abstract

Introduction

The aim of increasing accountability in the public sector has been an underlying objective of many open government policies and initiatives. The 2016 OECD Report on Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward found that improving accountability is one of the most common objectives of open government strategies, second only to enhancing transparency (OECD, 2016[1]). Furthermore, as the dimensions of what constitutes open government have expanded over recent decades, so too has the concept of accountability, which has become a key element of good governance discourse (Bovens, Schillemans and Goodin, 2014[2]) given its ability to improve government processes and performance and restore citizens’ trust in governments. For this reason, the 2017 Recommendation of the OECD Council on Open Government (hereafter “OECD Recommendation”) identifies accountability as a core principle of open government in support of democracy (OECD, 2017[3]).

This Chapter will focus primarily on defining the parameters for vertical accountability in Brazil in addition to a focus on elements of horizontal accountability. In this context, horizontal accountability refers to how the different branches of the state, namely the executive, the legislative, the judiciary, as well as independent institutions, hold each other to account on behalf of citizens. This also consists of formal relationships within the state itself, whereby state actors have the formal authority to either restrain or demand explanations of one another (Lührmann, Marquardt and Mechkova, 2017[4]). This form of accountability is also emphasised in the 2017 OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity, which highlights the need for effective oversight alongside risk management, enforcement and sanctions, and stakeholder participation (OECD, 2017[5]). Furthermore, the 2012 OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance also notes vertical and horizontal gaps that can occur in administrative accountability and stresses the need for transparent frameworks for accountability for effective regulatory reforms (OECD, 2012[6]).

In contrast, vertical accountability signifies the direct relationship between the government and stakeholders and the ways in which the public can play a role in holding the public administration to account. Citizens can vote out elected officials, engage in demonstrations and protests, communicate with public bodies through online portals, provide feedback on policies and services, submit complaints, lobby public officials, and take an active role in monitoring and evaluating the public decision-making process. In these ways, stakeholders can apply different forms and levels of pressure to state actors (Harris and Schwartz, 2014[7]) through broader participatory processes in both their institutional and non-institutional forms (see Chapter 5 for further discussion). Stakeholder engagement seeks to improve the government-citizen relationship while leaving ultimate responsibility – and thus accountability – in the hands of officials who answer to the public.

Overall, the legal, policy, and institutional frameworks for different types of accountability are well-established in Brazil, and while accountability has been historically perceived through the lens of internal control and social control1, several public bodies have made progress in moving beyond this interpretation in their own practices and initiatives. In general, the necessary structures for accountability exist in Brazil but oversight bodies need to be safeguarded, both through the protection of their independence and an allocation of adequate human and financial resources – before they can be fortified to the extent needed to fulfil and – in some cases – expand their remit. Furthermore, while there are many opportunities for citizens to engage with their government, Brazil – as is the case for many countries – does not yet have a coherent vision for, and high-level commitment to, an overarching approach to accountability that is proactive rather than reactive. Efforts to improve accountability and responsiveness – similarly to those undertaken under the framework of their broader open government agenda – can also be fragmented and prone to overlap and could benefit from more clearly defined responsibilities for each public body involved.

The Chapter will thus provide recommendations to support Brazil in taking a more holistic approach to accountability within an integrated agenda for open government reforms efforts. In particular, it emphasises the need to strengthen social accountability, meaning the direct involvement of citizens and other stakeholders in contributing to ensuring accountability across the public administration, given its links to the other open government principles of transparency, integrity, and stakeholder participation. In this regard, the Chapter focuses on how Brazil could empower an existing public body with the mandate of a traditional Ombudsman institution to improve oversight and while also upgrading the existing platforms and processes for stakeholder engagement and feedback on public policies and services.

Taking a forward-looking approach to accountability

Governments must move beyond bookkeeping origins towards stronger democratic accountability

Representative democracies are underpinned by accountability by default, as they rely on the will of the public in choosing the elected officials that they wish to represent them. Today, citizens and stakeholders are calling for more accountability than ever in public decision-making, following decades of economic, financial, and social crises, as well as in the response and recovery to the COVID-19 crisis (Southern Voice, 2021[8]). In this context, accountability creates an environment that promotes learning, generates incentives and enables desirable risk-taking and innovation while contributing to a more resilient system of checks and balances. Moreover, engaging stakeholders in oversight processes can lead to greater citizen buy-in with policies and reforms, and this reciprocal relationship can give the government the legitimacy needed to make difficult decisions. Furthermore, prioritising accountability can contribute to reinforcing democratic systems as they tackle growing public discontent, which has been exacerbated by rising socio-economic inequality, political polarisation, general perceptions of corruption and inefficiency, and low trust in government (Pew Research Center, 2019[9]).

The concept of accountability has its historical origins in bookkeeping and the need for individuals and organisations to provide an account of their financial activities and their use of public funds, originally intended as a way to track government spending and demonstrate evidence against wrongdoing (Bovens, Schillemans and Goodin, 2014[2]). The modern movement for accountability has grown to encompass a much wider range of possibilities than the sole responsibility and duty of a public official or public body to citizens, to now consider a complete reconfiguration of government structures and the fundamental ways in which public bodies operate, with citizens and stakeholders at the centre (Hood, 2010[10]). In this way, the term no longer carries a rigid accountancy image related to audits or financial administration but can now relate to all forms of policy-making while carrying a promise of justice, integrity, and fairness (Khotami, 2017[11]). In fact, the World Bank states that there are several accountability relationships within a public administration (Stapenhurst and O’Brien, n.d.[12]) and for this reason, an all-encompassing approach to accountability through a sound system for feedback and oversight on a continuous basis is necessary.

In the context of this review, the OECD defines accountability as a relationship referring to the duty of government, public entities, public officials, and decision-makers to provide information on – and be responsible for – their actions, activities and performance. It also includes the right and responsibility of citizens and stakeholders to have access to this information and have the ability to question the government as well as to reward or sanction performance through electoral, institutional, administrative, and social channels. Lastly, it also involves governments using internal institutional and administrative mechanisms to reward and sanction government institutions, civil servants, and frontline providers in their delivery of government policies and services.

Accountability often involves two distinct stages: 1) answerability, which is the obligation of the government to provide information and justification for its activities, which may or may not lead to enforcement or sanctions (Schedler, Diamond and Plattner, 1999[13]) and; 2) enforcement, which is the power of the public and the institution responsible for accountability to sanction (Fox, 2007[14]). While backward-looking accountability focuses on identifying fault and allocating appropriate sanctions, governments should move towards a more forward-looking approach on ensuring accountability throughout the decision-making process, identifying potential challenges, and communicating to and involving stakeholders at each stage, as well as reporting on eventual outcomes.

Outlining the flows, forms, and mechanisms for a holistic overview of accountability

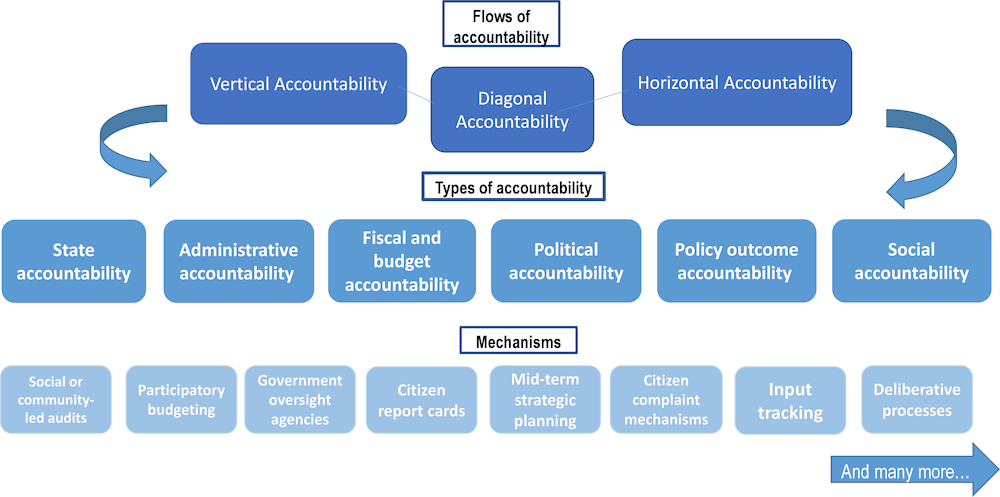

Governance frameworks as we know them are being constantly reshaped – whether due to progress in information and communication technology, increased digitalisation and innovation in the public sector, adapting systems to address global challenges and crises, or merely through responding to increased demands from civil society and citizens for opportunities to engage with their public officials. These transformations also modify accountability lines as they develop. Despite this evolution, there are broadly three main directional flows of accountability: vertical, horizontal, and diagonal (Figure 8.1) as well as various forms and mechanisms for accountability (Table 8.1) that can be identified.

Figure 8.1. Mapping different types of accountability

Note: This is an inclusive but not exhaustive list of all types of and mechanisms for accountability.

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Horizontal accountability is not the sole responsibility of one organ or public entity, but of many institutions and public officials who must ensure that government activities and decisions respond to citizens’ needs and demands. As aforementioned, it refers to the different branches of the state, namely the executive, the legislative, the judiciary, as well as independent institutions (e.g. ombudsman, supreme audit institutions, and special commissions) holding each other to account on behalf of citizens through a system of checks and balances and oversight. This could include internal sanctions when these responsibilities are not met as well as potential penalties or consequences for failing to answer claims. There are often opportunities for the public to seek redress through these formal mechanisms (e.g. complaints and appeals to Ombudsman, information commissioners, and public prosecutors) (Transparency and Accountability Initiative, 2017[15]).

Vertical accountability involves the direct relationship between citizens and the public administration and is generally used to refer to the ability of the public to hold its government accountable through elections and political parties. It can also include more informal methods of participation – citizens can protest, lobby, devote monetary resources, publicise government failures and engage in conscientious objection, amongst others, to apply pressure to public bodies (Harris and Schwartz, 2014[7]).

Diagonal accountability is a much-debated term with varying definitions. The prevailing view being that it is a hybrid form of accountability, which operates between the dimensions of vertical and horizontal accountability by engaging citizens and CSOs directly in the workings of public entities designed to increase accountability (Open Government Partnership, 2019[16]). This form of accountability emphasises the ability of civil society and a free and independent media to constrain the exercise of state power as well as the importance of citizen participation in civic organisations and informal movements to promote social capital, which in turn contributes to good governance (Walsh, 2020[17]).

Table 8.1. Selected forms of accountability

|

Selected forms of accountability |

|

|---|---|

|

State accountability |

State accountability refers to the need to ensure that public entities hold each other to account through checks and balances. Consequently, this form of accountability is closely linked to horizontal accountability. Examples of state accountability include the structures and mechanisms in place to ensure separation of the executive, legislative and judicial branches, as well as the role of independent institutions such as the ombudsman, information commissions, Supreme Audit Institutions, or supranational entities for oversight. |

|

Administrative accountability |

Administrative accountability refers to a robust system of internal control measures that ensure that institutions and public servants are carrying out tasks according to agreed performance criteria, and using mechanisms that reduce abuse, improve adherence to standards, and foster learning for improved performance (McGarvey, 2016[18]). Internal control systems are preventative and incorporate risk management to detect inefficiencies that can affect the effectiveness of public entities. This form of accountability can be vertical and horizontal but rarely diagonal as it tends to underpin the distinct lines of responsibility between different departments and units in their respective duties. |

|

Fiscal and budget accountability |

Ensuring transparency and accountability throughout the budget cycle and fiscal proceedings can contribute to more efficient and effective service design and delivery (OECD, 2015[19]). These processes can also be enhanced with commitments to citizen engagement throughout the budget cycle, for example, through initiatives such as participatory budgeting (Harrison and Sigit Sayogo, 2014[20]). Fiscal and budget accountability is also horizontal as public administrations can evaluate the transparency of use of public funds and ensure that there are clear impact assessments of how financial resources are used and whether they are meeting their intended objectives. It can also be diagonal as there are ways for citizens to directly participate in monitoring the budgetary process, for example, by having a role in community procurement oversight and contracting and input tracking. |

|

Political accountability |

Political accountability can be defined as “a formalised relationship of oversight and sanctions of public officials by other actors”, which is decided through free and fair democratic elections (Bovens, 2007[21]). Political accountability refers to the constraints created by a wider system regarding the behaviour of public officials which allows citizens to remove individuals from public office. It can also refer to the wider hierarchy within government, such as the answerability of a minister to their parliament. As political accountability increases, the cost to public officials of taking decisions that benefit their private interests also grows, disincentivising corrupt practices. |

|

Policy outcome accountability |

Policy outcome accountability can ensure that policy-makers account for their performance by monitoring and evaluating policy outcomes and making relevant performance information on their achievements available in a timely manner (Bovens, Schillemans and Goodin, 2014[2]). The purpose of this process is threefold: policy makers are held accountable, there is an opportunity to learn from the past and most significantly, evidence-informed policy-making is fostered. Some of the mechanisms include creating a regulatory framework for policy monitoring and evaluation; establishing a clear mandate with dedicated resources for key actors to collect, analyse, and use performance information and data for more effective service design and delivery; increasing the availability and quality of performance information; and integrating a greater degree of evidence-informed decision-making in the policy-making process (Bovens, Schillemans and Goodin, 2014[2]). As an innovative new way of looking at the outcomes of government policies, strategies and programmes and undertaking more impact assessment, this form of accountability can be vertical, horizontal, and diagonal depending on the mechanisms employed. |

|

Social accountability |

Social accountability plays a key role in ensuring that the voices of the public are heard (Malena, Forster and Singh, 2004[22]). The term social accountability is frequently used to describe the direct involvement of citizens, CSOs, and the media in ensuring accountability in state institutions (Lührmann, Marquardt and Mechkova, 2017[4]). Strong mechanisms for stakeholder engagement, feedback, and consultation also contribute to a more responsive government that centres citizens in public decision-making and quality control of policies and services. The role of civil society and media in their capacity as watchdogs and whistle-blowers to highlight any false information shared by governments is also crucial for social accountability. Moreover, public entities can partner with civil society to ensure accountability. This could, for example, include oversight institutions with a specific mandate for stakeholder engagement with watchdog organisations, a central government monitoring local governments or agencies use of funds with the support of local CSOs, or a regulatory agency partnering with media to investigate the roll-out of services of a public body (World Bank, 2013[23]). |

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

The Brazilian context for accountability

Alongside the notable benefits of greater accountability for good governance, it also has a critical role in the functioning of a modern economy and for wider societal well-being (International Monetary Fund, 2005[24]) as it supports the domestic private sector and contributes to more secure public-private investments. Many of the advantages of accountability – including the avoidance of policy capture and corruption – are imperative for domestic business growth. Strong mechanisms for accountability thus implicitly demonstrate more effective and efficient governance, making a country a more reliable and attractive trade partner for foreign direct investment (FDI). In fact, the 2017-2018 edition of the World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Index found that some of the most problematic factors for doing business in Brazil were perceptions of corruption, inefficient government bureaucracy, policy and government instability, and an insufficient capacity to innovate (World Economic Forum, 2018[25]).

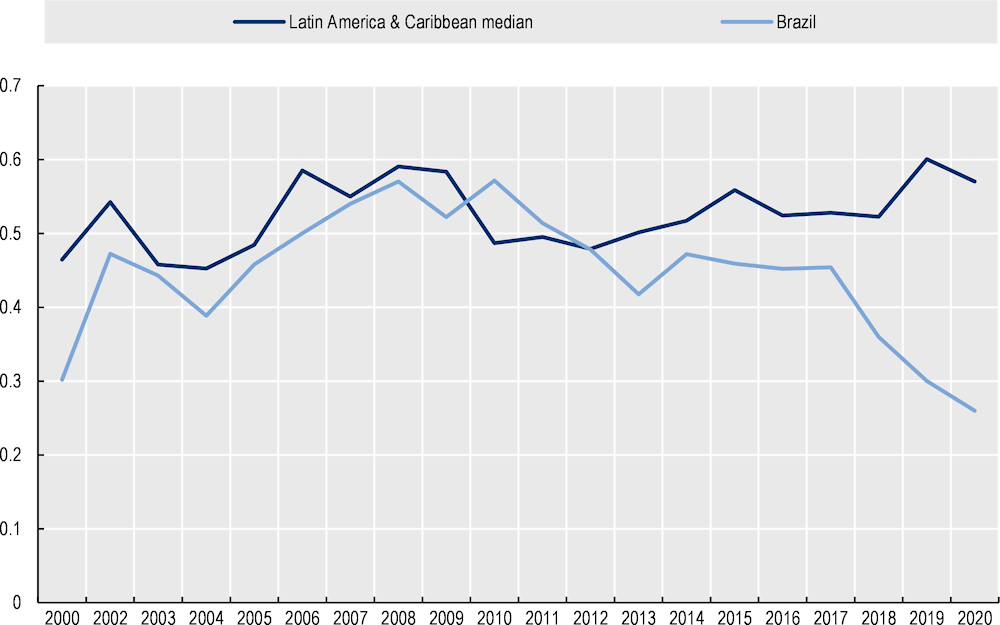

The setting for accountability in Brazil benefits from the existence of a broad network of institutions with a mandate for internal control and oversight to ensure that checks and balances are maintained. However, over recent years – as in other countries around the world – Brazil’s institutions have not been immune to weakening and are suffering from lower levels of citizen trust. Trust levels across OECD countries stood at 45% even before the pandemic (OECD, 2019[26]), with Brazil falling far below the OECD average at 17% in 2018 (OECD, 2020[27]). As data from the 2018 Latinobarómetro shows, this is also coupled with low levels of support for democracy more generally, at 34% in Brazil at the time (International IDEA, 2018[28]) (Latinobarómetro, n.d.[29]). Furthermore, Brazil ranks at 96th place out of 180 in Transparency International’s 2021 Corruption Perception Index (CPI) (Transparency International, 2021[30]) and their 2019 Global Corruption Barometer found that 54% of citizens believed that corruption had increased in the previous 12 months (Transparency International, 2019[31]). Moreover, their score in the 2020 World Bank Voice and Accountability Index (World Bank, 2020[32]) decreased from its highest in 2010 (0.57) to its now lowest in over two decades (0.34) (see Figure 8.2).

Figure 8.2. Brazil in the World Bank Voice and Accountability Index, 2020

Legal, policy and regulatory frameworks for accountability in Brazil

The Brazilian Constitution and other relevant national frameworks provide safeguards for accountability

The Background Report submitted for the OECD Open Government Review of Brazil outlined a number of comprehensive legal frameworks for accountability in the country. Firstly, the Constitution of Brazil references the principle of accountability in Article 70, Sole Paragraph:

Accounts shall be rendered by any individual or legal entity, public or private, that uses, collects, keeps, manages or administers public funds, property and securities or those for which the Union is responsible, or that assumes obligations of pecuniary nature in the name of the Union (Government of Brazil, 1988, with amendments through 2017[33]).

Furthermore, the separation of the legislative, the executive and the judicial powers are declared to be “independent and harmonious among themselves” (Government of Brazil, 1988, with amendments through 2017[33]), an essential element of horizontal accountability. Title III, Chapter VI of the Constitution also states that the Federal Union should not intervene in the activities of the states, except to ensure compliance with constitutional principles, one of which includes “the rendering of accounts of the direct and indirect public administration (Government of Brazil, 1988, with amendments through 2017[33]). The Constitution also grants opportunities for decentralised internal control at the subnational level, with Article 34 noting that the Union will not intervene in the States or Federal District except to ensure compliance with the constitutional principle of “rendering of accounts of direct and indirect public administration” (Government of Brazil, 1988, with amendments through 2017[33]).

In addition to the Constitution, there is a wide range of legislation relevant to horizontal accountability, including laws and decrees on administrative improbity, public integrity, lobbying, fiscal responsibility and whistleblowing, among others, with the aim of guiding public officials on their duties and responsibilities to the public (see Chapter 2 on the Enabling Environment). For example, the Fiscal Responsibility Law (Law 101 from 2000) establishes guidelines for budgetary and financial affairs and delineates clear penalties for the non-compliance of any public body (Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, 2000[34]). In addition, Decree 10.153 from 2019 provides means to protect whistle-blowers who denounce misconduct in public bodies (Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, 2019[35]). Lastly, the Law on Administrative Improbity (Law 8.429 from 1992) provides for the punishment and sanctions applicable to public officials in case of unlawful behaviour in the exercise of their role (Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, 1992[36]). However, amendments made in October 2021 (Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, 2021[37]) “loosened some of the provisions” of this law and altered 23 of its 25 articles (Tauil & Chequer Advogados, 2021[38]). Some of the changes included, for example, the need for acts of administrative improbity that violate the principles of the public administration to result in “significant damages” if they are to be subject to sanction (Tauil & Chequer Advogados, 2021[38]). The Ministério Público also now has the exclusive right to file improbity lawsuits (Tauil & Chequer Advogados, 2021[38]). While there are divergent opinions on the implications of these changes, CSOs interviewed during the OECD fact-finding mission raised concerns that these amendments could create potential for increased impunity, for example, because specific intent is required to deem an act as misconduct and the statute of limitations has been reduced.

Significant steps have been taken to improve accountability in Brazil through an overarching cross-government approach for both the centre of government and line ministries. In 2017, the President of Brazil committed to improving public governance through alignment with “the principles of trust, responsiveness, integrity, regulatory improvement, accountability and transparency” through the introduction of the National Policy for Public Governance Decree (Decree 9.203 from 2017) (OECD, 2017[39]). This Decree was key in setting a standard for all public bodies regarding the implementation of monitoring and control mechanisms for risk management alongside its obligation for all public bodies to approve an integrity plan (see Chapter 3 for an overview of the main laws and decrees guiding open government reforms in Brazil). The decree also mandated that each public organisation develops its own public integrity programme and integrity management unit to address and mitigate its risks in the institution (Vieira and Araújo, 2020[40]). In this regard, the CGU has also created a public integrity panel that presents a panoramic view of public ethics in the Federal Executive branch, as discussed in Chapter 3 on Governance Processes and Mechanisms. Lastly, it also led to the establishment of an internal control unit and a control advisor in each ministry to ensure adherence and compliance to good practices (Aranha, 2018[41]). In 2018, the OECD found that the full implementation of this decree could help to advance a culture not only of correction but of prevention (OECD, 2017[39]). Furthermore, the National Open Government Policy (Decree 10.160 from 2019) includes the improvement of policy-making through better spending, more effective prioritisation, and reduced corruption among its core objectives (Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, 2019[42]). Moreover, one of the most significant laws for accountability in regards to public-private interactions is the Brazilian Anti-Corruption Act (Law 12.846 from 2013), which targets corrupt business practices in Brazil and defines administrative and civil penalties for any individuals involved (Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, 2013[43]). Lastly, the Law on Conflicts of Interest (Law 12.813 from 2013) prohibits any public officials from engaging in activities that may involve the disclosure of information that benefits either themselves or a third party (Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, 2013[44]).

Several legal frameworks also promote vertical accountability and responsiveness to stakeholders and citizens. Regarding stakeholder participation, the legal framework is comprehensive but scattered, with elements in federal and local legislation as well as in dedicated policy areas (see Chapter 5 on Citizen Participation). That said, several laws and policies do encourage feedback and engagement with stakeholders and citizens through vertical accountability mechanisms, for example, the legislative frameworks, ordinances and decrees underpinning the ouvidorias (see Box 8.3 for legal frameworks that strengthened the ouvidorias). The Brazilian Constitution, while not directly creating these offices, provides the first legal grounding for the establishment of the ouvidorias (Government of Brazil, 1988, with amendments through 2017[33]). Article 37, paragraph 3 states that the law will regulate types of participation for users in governmental bodies in regards to the provision and quality of public services, the access of users to administrative information, and lastly, the regulation of complaints “against negligence or abuse in the exercise of an office, position or function in government services” (Government of Brazil, 1988, with amendments through 2017[33]). This original wording provided the basis for the development of the current network of offices. The Constitution also explicitly called for the establishment of Justice ouvidoria offices as well as for the Public Prosecutor’s Office, with powers to receive complaints and accusations from any interested party against members or bodies of the Judicial Branch and the Public Prosecutor’s Office (Government of Brazil, 1988, with amendments through 2017[33]). A number of additional legislative frameworks, ordinances and decrees solidified and consolidated the importance of stakeholder participation for vertical accountability over the last decade, demonstrating Brazil’s commitment to improving responsiveness and receiving feedback from citizens.

Brazil could upgrade its approach to social accountability through its Open Government Partnership National Action Plan and an open government strategy

As is the case in many OECD countries, Brazil’s definition of and approach to accountability is not clearly defined in any policy document. However, the Law of Introduction to the Norms of Brazilian Law provides a broad overview of how public decision-making should function in the administrative, judicial and internal control spheres (Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, 1942, with amendments through 2018[45]). Furthermore, Brazil’s most recent Open Government Partnership (OGP) 4th and 5th National Action Plans provide some insight into the country’s conceptualisation of accountability and its role within the open government agenda (Office of the Comptroller-General of Brazil, 2018[46]) (Office of the Comptroller-General of Brazil, 2021[47]). As discussed in detail in Chapter 2 on the Enabling Environment, Brazil is currently implementing 12 commitments from their 2021-2023 action plan (Office of the Comptroller-General of Brazil, 2021[47]). It is significant to note that accountability is an underlying objective of many of Brazil’s OGP commitments. For example, many of their previous commitments (see also Chapter 2) contribute to fostering accountability, such as the opening of budget data and government procurement as well as the institutionalisation of civil society participation and the consolidation of social participation initiatives. Furthermore, their 5th Action Plan includes commitments that contribute to greater diagonal accountability by involving civil society actors in a collaborative laboratory “to promote understanding, build standards and share experiences related to laws, practices, processes, methods, data and other important resources for fighting against corruption” (Office of the Comptroller-General of Brazil, 2021[47]). Horizontal accountability is also prioritised in their commitment to create a national computerised system to “build a database on human rights violations that allows integration with other systems used by subnational entities” (Office of the Comptroller-General of Brazil, 2021[47]).

However, while the government is highly committed to transparency (see Chapter 6), their plans include fewer concrete initiatives for enhancing accountability and responsiveness. The 4th Action Plan noted that “an accountable and responsive government establishes rules, norms and mechanisms which oblige governmental agents to justify actions, act according with received criticisms or demands and take on the responsibility of complying with their duties” (Office of the Comptroller-General of Brazil, 2018[46]). Notably, while this statement does not include a concrete definition of accountability itself, it does resonate with several important elements of a forward-looking approach, including the importance of responsiveness and the need to act upon feedback received from stakeholders and citizens. The plan also outlined three distinct stages of accountability:

1. Government renders accounts;

2. Government addresses doubts and justifies its actions;

3. Government is accountable. (Office of the Comptroller-General of Brazil, 2018[46])

This approach highlights an ex-post view of accountability as an “after the fact” process. Furthermore, there are no concrete commitments outlined in the plan that aim at improving how the government “addresses doubts and justifies its actions” (Office of the Comptroller-General of Brazil, 2018[46]). During the OECD fact-finding mission it was confirmed that Brazil’s view of accountability emphasises sharing documentation, offering an account of decisions made, and showing how funds have been used, as accountability tends to be related mostly to internal control. In addition, stakeholder or citizen participation in particular is seen through the lens of social control or social accountability (see Upgrading social accountability through improved engagement and feedback). As discussed in Chapter 5, there is significant overlap in the accountability and participation agendas, as they are seen as being intertwined under the broad concept of social control. However, as previously mentioned, while broader participatory processes do indirectly contribute to accountability, the aims and objectives of participatory initiatives in comparison with accountability initiatives do differ as while participation prioritises collaboration and inclusive decision-making, social accountability prioritises answerability, responsiveness, offering feedback, and addressing complaints.

The introduction of an Open Government Strategy (see Chapter 2 on the Enabling Environment) could be used as a tool to further a more concrete interpretation of accountability. Within this strategy, Brazil could articulate a clear definition of accountability within the framework of its broader open government objectives. This definition could also serve to communicate and mainstream this concept across the public administration and support more harmonious co-ordination based on mutual understanding. One example in this regard is Colombia, which defines accountability (Law 1757 from 2015) (Government of Colombia, 2015[48]) as a process made up of a set of norms, procedures, methodologies, structures, practices and results through which the public administration entities at the national and territorial level and public servants report and explain the results of their management to citizens, civil society, and other public entities and control bodies, based on the promotion of dialogue. It also references accountability as an expression of social control that includes requests for information and explanations alongside a broader evaluation of management (Government of Colombia, 2015[48]). Following on from this, Brazil could also include measurable targets on accountability in its 6th OGP action plan that emphasise both improving existing mechanisms for horizontal and vertical accountability (as discussed in further detail below) as well as enhancing feedback and responsiveness to stakeholders.

Towards a more responsive public administration in Brazil

Need to empower a body with the traditional mandate of an Ombudsman institution

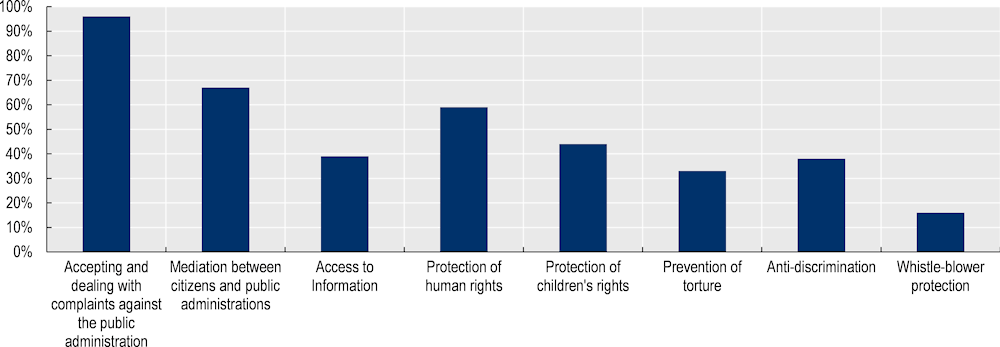

As the 2017 OECD report The Role of Ombudsman Institutions in Open Government notes, Ombudsman institutions play an important role in advancing a wider open government culture across the public administration (OECD, 2018[49]). Ombudsman institutions are independent offices that ensure that citizens are protected from violations of their civic rights as well as any negligent or deliberate errors or unsatisfactory decisions made by public officials (Batalli, 2015[50]). Ombudsman institutions regularly make important contributions and recommendations on public administration reforms, based on their expertise and insights about service delivery at national and sectoral level (OECD, 2018[49]). They also monitor and exercise control over the activities of state authorities, address administrative irregularities, and consider citizens’ complaints against public bodies or officials who breach civic rights and freedoms (see Figure 8.3 for common areas of activity). In this regard, they can submit proposals to amend legislation or revise unlawful practices of the bodies of state authorities, to prevent a recurrence of such instances (OECD, 2018[49]).

According to the International Ombudsman Institute, a number of key features ensure their independence and credibility. In general, the role of these offices is enshrined in the constitution, with the strongest legal frameworks preventing political choices for the appointment of its head (Gottehrer, 2009[51]). In addition, these offices usually operate separately from the executive branch of government to guarantee impartiality and have the right to initiate investigations even if a complaint has not been formally submitted by a citizen (Gottehrer, 2009[51]). This imbues the Ombudsman office with an ability to identify and combat corruption and make proposals for greater accountability.

Due to their position as an institution that is close to citizens and stakeholders and interacts with them regularly, they have a unique ability to advance the open government principles of transparency, accountability, and stakeholder participation in their own functions (OECD, 2018[49]). Some countries have Ombudsman offices at both the national and sub-national levels of government such as Australia and Mexico, while other nations have Ombudsman offices only at the sub-national level, as in Canada and Italy (OECD, 2021[52]). In both arrangements, embedding citizen and stakeholder participation in their work can lead to more accurate and effective recommendations from this body to the rest of the public administration due to a greater range of inputs and expertise. In this sense, the Ombudsman can demonstrate the value of openness concretely. Moreover, these bodies can also promote open government by developing guidelines and codes of conduct for public officials that prioritise open government practices and processes (OECD, 2018[49]).

Figure 8.3. Ombudsman institutions areas of activity according to their mandate

Note: 94 Ombudsman institutions participated in the survey. OIs’ mandates can involve a wide variety of areas of activity.

Source: Responses to the 2017 OECD Survey on the Role of Ombudsman Institutions in Open Government (OECD, 2018[49])

Contrary to neighbouring countries in the region, Brazil does not have a traditional and independent Ombudsman institution that has a mandate for all steps of an accountability cycle, that is to say: to monitor, investigate and sanction. Furthermore, no institution is currently fully in line with the Paris Principles and accredited by the Global Alliance for National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI, n.d.[53]) which stipulates specific criteria as outlined below (Box 8.1).

Box 8.1. Ombudsman institutions for accountability

United Nations Paris Principles

The Paris Principles represent the first set of standards for National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs) and were endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 1993 (Resolution A/RES/48/134) (ENNHRI, n.d.[54]). The Principles set out the main criteria that NHRIs are required to meet:

They must be established under primary law or the Constitution;

They should have a broad mandate to promote and protect human rights;

They must have formal and functional independence;

They must commit to pluralism and representation of all aspects of society;

They must benefit from adequate resources and financial autonomy;

They should have freedom to address any human rights issue that arises;

They must issue annual reports on the national human rights situation;

They should cooperate with national and international actors, including civil society (ENNHRI, n.d.[54]).

An overview of Ombudsman models

Linda Reif identifies two different Ombudsman models (Reif, 2004[55]). The classical model consists of those developed in the image of the Swedish institution, which often had non-coercive powers and existed as accountability mechanisms to advise and oversee the activities of public officials (Reif, 2004[55]). In contrast, the hybrid model adopted by Latin American countries in the late 20th century often had a particular focus on not only accountability in the public sector, but also the broader protection of human rights. In Latin American and Caribbean countries, the Ombudsman is often considered “an independent investigator authorised to respond to the demands of citizens who “need a mechanism to control the abuses of the authorities and private individuals” (González Volio, 2003[56]).

Democracies in the region were preceded by “governments generally characterised by the lack of accountability and responsiveness on one hand and the pervasiveness of graft and state abuse of citizens’ rights on the other hand” (Uggla, 2004[57]). The period of democratisation in Latin America during the 1980s and 1990s led to a number of institutional reforms, which intended to enhance and strengthen the rule of law, accountability and other values associated with good governance (Uggla, 2004[57]). The Latin American model thus often gives explicit priority to the protection of human rights. These offices also often have promotional and educational functions and can transfer cases to the Public Ministry so that the latter can initiate a criminal prosecution when necessary (González Volio, 2003[56]).

Both the Public Prosecutor’s office (Ministério Público) and the Public Defender’s office (Defensoria Pública) play an important role in regard to oversight, and the Defensoria in particular shows potential to fulfil the traditional responsibilities of an Ombudsman institution. Both bodies are essential to core democratic functioning of the Brazilian state but differ in their responsibilities and jurisdiction. Broadly, the Federal Public Ministry has the mission of overseeing compliance with the law at each level of government in Brazil while the Public Defender's Office ensures access to justice and acts as the pro-bono defence of those who cannot afford a lawyer (Gazeta Do Povo, 2015[58]). In Brazil, a number of bodies collaborate at the national and subnational levels to ensure accountability for human rights abuses and to protect civil liberties in particular. The below table provides an inclusive but not exhaustive list of these bodies and their key attributions (Table 8.2), including the Ministério Público and the Defensoria Pública.

Table 8.2. Oversight institutions for civic freedoms and rights in Brazil and their key attributions

|

Name |

Level of government |

Key attributions regarding civic space |

|---|---|---|

|

Public prosecutor’s offices (Ministério Público), in particular the units in charge of citizens’ rights |

Federal and state |

Oversee state actions and ensure accountability for violations of constitutional rights. External oversight over police activity. |

|

Public defenders’ office (defensorias públicas) |

Federal and state |

Advise citizens and defend their interests and rights. |

|

Federal Supreme Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal) |

Federal |

Judges legislation at federal and state level and breaches of principles regarding civic rights and freedoms foreseen in the Constitution. Highest court of law in Brazil. |

|

National Human Rights Hearing Office |

Federal |

Receives and deals with complaints denouncing human rights violations. |

|

Councils (conselhos) |

Federal, state, municipal |

Discuss violations and recommend actions to prevent and protect rights. |

|

Secretariats (Justice, Citizens, Human Resources, etc.) |

State, municipal |

Co-ordinate and implement public policy actions for the promotion and protection of civic rights. |

|

Ouvidorias in ministries and public entities |

Federal, state, municipal |

Receive and deal with complaints and suggestions from citizens on public services. |

|

Inspector General offices (Corregedorias) |

Federal, state, municipal |

The national corregedoria exercises external oversight of police activity and combats intentional violent crimes. |

|

Special courts (juizados especiais) for small cases |

Federal, state, municipal |

Moderate, judge and execute cases of lesser complexity. |

Note: According to the National Council of Public Prosecutors’ latest annual report, the “National corregedoria has given a new focus to correctional activity, implementing the thematic corrections in public security, with greater emphasis on ministerial action in the areas of penal execution, external control of police activity and combating intentional violent crimes” (National Council of Public Prosecutors, 2021[59]).

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Support the Defensoria Pública in taking a more strategic role as a traditional Ombudsman

The Defensoria Pública (Public Defender’s Office) is responsible for defending human rights and providing legal advice and guidance to citizens, especially those who are not able to afford such costs (UNHCR Brazil, n.d.[60]). The offices at the federal and state levels provide services free of charge to citizens, especially the most disadvantaged and vulnerable members of society. They are guaranteed by the Constitution (Government of Brazil, 1988[61]). Their latest report (CNCG, CONGEDE and DPU, 2021[62]) shows that public defenders are present in all federal public bodies of Brazil. However, public defenders’ offices currently cover only 44.5% of judicial districts (comarcas). These judicial districts are comprised of one or two municipalities, meaning that there are just 3 defenders available for every 100 000 inhabitants. Other districts are partially supported due to working groups and itinerant programmes, which include buses, vans, and boats that travel to remote areas transporting teams of judges, prosecutors, public defenders, conciliators and, in some cases, professionals from other areas, such as doctors and psychologists (Ipea, 2015[63]). In 2019, public defenders’ offices provided a record high number of legal assistance consultations (19 522 126) and generated 2 630 157 judicial processes (CNCG, CONGEDE and DPU, 2021[62]). Specialised advisory services for defending vulnerable groups and rights is available in 71% of federal units.

The Defensoria legally protects individual and collective rights in both a judicial and extrajudicial capacity. In this sense, its areas of focus correlate quite closely with the work of a traditional independent ombudsman institution. In addition, the Defensoria can, in fact, file class-action lawsuits on behalf of citizens and urge the government to act. For example, one such recent case involved the Defensoria filing a lawsuit at the Supreme Court to demand that the government issues a plan to ensure that states and municipalities receive adequate oxygen supplies in hospitals during the COVID-19 crisis (The Brazilian Report, 2021[64]). Significantly, a 2004 constitutional amendment grants administrative, functional and financial autonomy to public defenders’ offices, guaranteeing their independence from the executive (Government of Brazil, 2004[65]). Some Brazilian jurists have argued that the constitutional mission as well as its institutional characteristics would allow for the classification of the Office as an Ombudsman: "The performance of the Ombudsman's role by the Defensoria is delimited by the scope of its institutional purposes, which are especially linked to the defence of low-income and vulnerable individuals and groups" (National Association of Public Defenders (ANADEP), 2015[66]).

Despite the importance of the Defensoria in holding the government to account on issues of civil liberties among others, their role is not currently being optimised. Interviewees stressed that the offices are increasingly suffering from a lack of human resources and qualified and interested personnel, a challenge which can hinder them from effectively defending citizens and which they expect to become a more prominent issue in years ahead. In particular, skills and capacity shortages can prove detrimental to the ability of government organs and public officials to reach their full potential, and at worst, can lead to negligence. Furthermore, financial autonomy remains a challenge, as these offices rely on the National Treasury and successive budget cuts have compromised the expansion of the state Defensoria offices, which had been foreseen in a 2014 constitutional amendment (Federal Senate, 2021[67]; Government of Brazil, 2014[68]; Ipea, 2013[69]). A comparative analysis between the institutions that make up the Brazilian justice system reveals that the budget allocated to the Defensoria in 2021 was 313% lower than that of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, and 1 575% lower than that of the judiciary (CNCG, CONGEDE and DPU, 2021[62]). This contrasts with the number of staff per institution. The number of public defenders is 88% less than the number of public prosecutors and 162% less than the number of judges, magistrates and ministers of the judiciary. Brazil could demonstrate their understanding of the importance of this strategic body by channelling the appropriate financial resources and protect them in the future through for example, earmarking their allocation.

The presence of Defensoria offices across the country, as foreseen in the constitutional amendment, is an important instrument of access to justice for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged members of society. In general, Brazil could seek to address the challenges that they face by affording them the resources needed to match their responsibilities. This could include predictable and adequate funding, independent of the political cycle, which is essential to the Defensoria’s independence and fundamental in ensuring their ability to respond to the growing demand for their services and in fulfilling their core mandate.

The Defensoria currently advocates on behalf of citizens and operates independently of the federal government, meaning that it is a suitable candidate for further development and expansion of its remit regarding monitoring and oversight of civic freedoms in Brazil. Moreover, given the Public Ministry’s independence from the other three branches of government alongside its safeguarded budget, in theory it could also be a well-placed body to undertake this role. However, recent issues surrounding its appointment process and accusations of politicisation means that the independence of the Public Ministry would need to be sufficiently strengthened, before it would have the capacity to perform as an effective independent oversight institution for civil liberties. In light of this context, Brazil could thus take a long-term view to considering the development of the Defensoria into a traditional Ombudsman institution in line with the Paris Principles (see Box 8.1), through the creation of a specific working group that would assess this proposal and produce concrete recommendations on the changes required. This Ombudsman institution could also have a clear mandate for promoting the values of open government, similarly to the Ombudsman in Argentina, which has strategic oversight of the open government agenda (Office of the Ombudsman of Argentina, n.d.[70]).

Empower the Ministério Público for oversight of civic freedoms and rights and addressing constraints

As aforementioned, the Public Prosecutor’s Office (Ministério Público Federal) is mandated by the Constitution to “oversee the effective respect by public powers and services of the rights secured in the Constitution, promoting the necessary measures to guarantee them”, including “to exercise external control over police activity” (Art. 129 Item VII) (Government of Brazil, 1988, with amendments through 2017[33]).The Brazilian Constitution grants its public prosecutors with three substantial responsibilities – to defend individual rights, to maintain legal order, and to uphold the democratic regime (Federal Public Ministry, n.d.[71]). This fourth branch is comprised of four divisions that operate at the national and local level. These include: 1) The Federal Public Ministry (MPF); 2) The Public Ministry of Labor (MPT); 3) The Military Public Ministry (MPM); 4) The Public Ministry of the Federal District and Territories (MPDFT) (Federal Public Ministry, n.d.[71]). Public prosecutors investigate potential crimes and irregularities identified at their own initiative or reported by public agencies or citizens. Based on the results of their investigations, they can submit a case to the judicial system. It was noted in the fact-finding mission that public prosecutors also have the power to administer penalties and sanctions to public officials and bodies. The Public Prosecutor’s Office is currently the source of most of the major civil cases for the defence of rights that are brought before the judiciary (Néri de Oliveira, 2021[72]). Prosecutors can also act preventively and extrajudicially, through recommendations, public hearings and agreements (Public Prosecutor's Office, n.a.[73]).

The Public Ministry releases annual report on its activity and management through its own online portal. The latest 2020 report on the results of the performance of the MPF notes that the website had 7 242 972 visitors that year, with many millions more engaging with their Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts (Federal Public Ministry, 2020[74]). The report provides a detailed breakdown of the petitions received from citizens and stakeholder and whether they amount to criticism, suggestions, or specific complaints. The Public Ministry responded to 94.2% of these submissions in a timely manner. The report also outlines how many were completed versus how many were forwarded to an external body, but does not provide any further detail on their status at the time of writing. An earlier “Studies and Statistical Surveys of Performance” report available on the website (Federal Public Ministry, n.d.[71]) for 2015‑17 found that there were 332 897 judicial processes and 16 104 extrajudicial procedures during that time period in the area of citizens’ rights. However, this report does not provide a breakdown per right nor by the status of those that were filed as judicial actions (Federal Public Ministry, 2017[75]). The Public Ministry could begin to more widely disseminate this data on the status of judicial processes and share it with citizens through their portals and social media accounts, this would also enable the MPF and relevant external stakeholders to gain an accurate overview of its performance and identify potential trends.

As mentioned above, according to the Constitution, the Public Prosecutor’s office is formally independent and the procedure is set out by article 128, paragraph 1 (Government of Brazil, 1988, with amendments through 2017[33]). Once nominated for a role, prosecutors are broadly immoveable and cannot, an aspect for which Brazil has been historically lauded as a model in the region. In addition, the prosecutors (career members of Public Ministry) themselves are autonomous and are not submitted to the head of Public Ministry for approval of their duty (Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, 1993[76]). However, during the fact finding mission, concerns regarding emerging weaknesses in its autonomy were raised. Several public officials and civil society interviewees stressed the need to strengthen the role of the Public Ministry and highlighted some recent limitations on their autonomy. For example, while the procedure for appointing the head of the Ministry is outlined in the Constitution, a non-tacit process known as a “Triple list” approach has become an informal norm whereby the President chooses from a list composed of the three most qualified candidates voted by public prosecutors involved in the process. This practice is not provided for by law, but rather has become a tradition (National Association of Attorneys of the Republic, 2019[77]). Notably, however, this protocol was not followed during the two most recent appointments in 2019 and 2021 (National Association of Attorneys of the Republic, 2019[77]). A triple list approach to the nomination of the Chief Public Prosecutor is a democratic practice that generates legitimacy as it is sourced by the broader Public Ministry, and as such, it could be further protected. In order to do so, a triple list could be legally installed and guidelines on the process could be created to advise the public officials involved.

In addition, civil society interviewees in the fact-finding mission noted that public prosecutors often have a huge volume of work. This can affect their capacity to thoroughly investigate to the extent required related to a broader challenge of inadequate human and financial resources for the workload, which can be detrimental to the quality of investigations as well as the quantity that prosecutors can afford to effectively pursue. It is important to note that this is despite the fact that the Federal Police also have competences in undertaking such investigations. The main function of the Federal Police is to uncover criminal offenses that act against the interests of the federal government, its autonomous bodies, and public enterprises, as well as “other offenses with interstate or international repercussions” as provided by law (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, n.d.[78]). While the Federal Police undertake investigations, they cannot prosecute crimes as only the Public Ministry can present complaints to the judiciary, which then initiates proceedings which are either civil or criminal (Aranha, 2018[41]). In this regard, Brazil could commit to reinforcing the role of the Ministry by evaluating whether their workload burden affects prosecutors’ abilities to fulfil their role.

Mainstreaming Brazil’s approach to accountability across the public administration through high level commitment and coordination

A number of bodies in Brazil are well-placed to promote a forward-looking approach to accountability and to encourage greater coordination across the public administration. Where the CGU focuses more specifically on policy-making, coordination, and implementation of internal and social control across the public administration, the OECD interviews revealed that both the Government Secretariat of the Presidency of the Republic (SEGOV) and Casa Civil could promote political articulation for accountability in Brazil. During the OECD fact-finding mission, it was mentioned that Casa Civil has a key role in core pillars of accountability and takes a traditional reporting approach to the concept as a “rendering of accounts for each body”. For example, Casa Civil contributes to the “evaluation and monitoring of government action and the management of agencies and entities of the federal public administration” as well as “coordinating and monitoring the activities of the Ministries and the formulation of projects and public policies” (Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, 2019[79]). They also directly assist the President in formulating his annual message (Mensagem ao Congresso Nacional) to Congress upon the opening of the legislative session each year (Government of Brazil, 1988, with amendments through 2017[33]) (Center for Research Library, n.d.[80]), as required by Article 84 of the Constitution. This address accounts for any decisions made and offers a statement justifying the activities undertaken and planned during the President’s tenure. Moreover, the primary function of SEGOV is to “guarantee the uniformity of the communication for the Federal Executive Branch” (OECD, 2020[81]) and thus this body could commit to high-level articulation of a pioneering approach to accountability. Casa Civil and SEGOV could learn from other international good practices from centre-of-government offices in exploring a more advanced view of accountability and supporting collaboration and coordination with the other bodies in charge of administrative accountability and budget and fiscal accountability.

Due to the complex institutional arrangement for accountability in Brazil, most public bodies with a mandate for accountability must collaborate and coordinate “to develop joint actions, match priorities, work together in special operations, and exchange information” (Aranha, 2018[41]). In fact, several have existing cooperation agreements to this effect and the number of such agreements has been expanding in Brazil (Aranha, 2018[41]). Given that the CGU’s position as a Comptroller offers an overview of the public administration – it could commit to creating a holistic overview of how public bodies currently work together regarding internal control and the ways in which collaboration could be further encouraged to identify potential misconduct. The CGU could also take a systems thinking approach to change, by focusing on how current governance frameworks, processes and methods can better work in tandem while reducing silos and improving operations overall (Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI), n.d.[82]). Regarding coordination of bodies with a mandate for accountability, Brazil could also draw inspiration from Colombia’s new National System of Accountability (Sistema Nacional de Rendición de Cuentas – SNRdC) which is currently being implemented in compliance with Decree 230 from 2021 (Government of Colombia, 2021[83]). This system articulates the set of public bodies, principles, norms, strategies, policies, programmes, and mechanisms involved in coordinating and enhancing the activities carried out within the framework of the accountability and also aims to facilitate citizen monitoring and evaluation of the planning and management commitments of state entities at the national and subnational levels (Government of Colombia, 2021[83]).

Because of the close connection between the SEGOV and Casa Civil on political articulation of accountability as well as their interaction with the CGU, which coordinates the concrete implementation activities related to internal control, all three bodies could endeavour to communicate a move away from a traditional control and compliance based perspective. Both the SEGOV and Casa Civil could utilise the suggested legal harmonisation of the open government agenda and the development of an Open Government Strategy as recommended in Chapter 2, to articulate and promote a more pioneering definition of and approach to accountability. In this regard, they could collaborate on high-level messaging to increase support across the public administration. One notable example is Finland, which currently ranks 3rd in SGI indicators on executive accountability (Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI), 2019[84]), and which promotes its vision for open government and accountability through a specific Open Government Strategy (OECD, 2021[85]).

Streamlining and increasing collaboration between public bodies with mandates for administrative accountability, policy outcome accountability, and fiscal and budget accountability

The CGU, Casa Civil and SEGOV could work closely with other bodies in Brazil that are currently in charge of other forms of accountability to map their current initiatives in this regard and integrate these existing practices with more forward-looking practices for horizontal accountability, including mid-term planning, strategic foresight and risk analysis. Currently, Brazil has a wide range of mechanisms for vertical and horizontal accountability that span different forms of accountability, including administrative, fiscal and budget, and policy outcome accountability, many of which are led by the CGU with involvement from different public bodies (see Table 8.3).

Table 8.3. Selected vertical and horizontal mechanisms for accountability in Brazil

|

Mechanism |

Objectives |

|---|---|

|

TIME Brasil programme |

This programme was created in 2019 by the CGU to assist states and municipalities in improving public management, creating more accountable institutions, and strengthening anti-corruption efforts (Office of the Comptroller General, n.d.[86]). |

|

The Diretoria de Transparência e Controle Social (DTC) civil society training |

The DTC within the CGU provides training for civil society on monitoring and evaluation of government activities (see Chapter 3) and promotes opportunities for stakeholder involvement in oversight. |

|

Observatório da Despesa Pública (ODP) |

This unit of the CGU applies scientific methodology and technology with a view to making more strategic decisions by monitoring public. The objective of the ODP is to contribute to the improvement of internal control and to function as a support tool for public management. The results generated by the unit serve as input for the audits and inspections conducted by CGU (Office of the Comptroller General, n.d.[87]). |

|

Inspections from Public Lotteries |

The CGU’s lottery programme randomly targets the federal funds transferred to Brazilian municipalities with less than 500 000 inhabitants (Aranha, 2018[41]). Under this framework, the CGU sends approximately 10 auditors to 60 randomly-selected municipalities each year to ensure funds are effectively channelled to the agreed-upon policy areas (Aranha, 2018[41]). |

|

Plano Mais Brasil programme |

The programme began in 2019 (Ministry of Economy, n.d.[88]) with the objective of improving the operating environment and creating conditions that protect public accounts from any fraudulent activity or misappropriation. The overall aim is then to “offer fiscal stability to the Union and subnational entities” (Ministry of Economy, n.d.[88]). |

|

Portal de Compras Públicas |

This portal opens up public procurement processes for interested stakeholders and citizens (Government of Brazil, 2020[89]) |

|

Anti-corruption taskforces |

The Lava Jato anti-corruption taskforce is an example of one of the most notable mechanisms for accountability. It used innovative tools, including plea-bargaining and the exchange of financial information with foreign authorities to retrieve almost USD 800 million to be returned to the state (Le Monde, 2021[90]). It resulted in almost 280 convictions, including many political leaders and lawmakers (Council on Foreign Relations, 2021[91]). |

Note: The Anti-Corruption Task Force was dismantled by Brazilian prosecutors in February 2021 (The Economist, 2021[92]). Reasons for its dissolution included both leaked accusations of misconduct and sidelining of appropriate procedures as well as the President’s statement that “there isn't any corruption" left to be investigated in the government (Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), 2021[93]). Source: (Office of the Comptroller General, n.d.[86]), (Office of the Comptroller General, n.d.[87]), (Aranha, 2018[41]), (Ministry of Economy, n.d.[88]), (Government of Brazil, 2020[89]), (Le Monde, 2021[90]), (Council on Foreign Relations, 2021[91]).

Given the role of the CGU for administrative accountability as the “internal control body of the Brazilian government responsible for defending public assets and for increasing transparency, through audit, internal affairs, ouvidorias, and corruption prevention and fighting” (Office of the Comptroller General, n.d.[94]) (see the OECD Report on Strengthening Public Integrity in Brazil (2021) (OECD, 2021[95]) for more information), this office has an overview of which public bodies can advance this new vision for accountability. As the CGU is also in charge of promoting the principles of open government across the government, the office operates as an important liaison between public bodies at both the federal and local levels and can collaborate with and encourage other bodies to fulfil their potential regarding accountability.

In this regard, another key actor in Brazil’s accountability web is the Federal Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União - TCU), which is crucial for fiscal and budget accountability while also having opportunities to promote social accountability. The TCU is the main external control institution of the federal government and functions as its Supreme Audit Institution (SAI) (Federal Court of Accounts (TCU), n.d.[96]). The TCU guides public officials by promoting “a more effective, ethical, responsive and responsible Public Administration” (Federal Court of Accounts (TCU), n.d.[96]) and their responsibilities broadly cover traditional budget and fiscal accountability processes such as accounting, contracting, and procurement, undertakes performance audits, and investigates financial fraud or a misappropriation of funds in public bodies (Federal Court of Accounts (TCU), n.d.[96]). The OECD report Supreme Audit Institutions and Good Governance stresses the importance of SAIs as key democratic institutions (OECD, 2016[97]), and as such, the TCU is “a critical inducer of change in the Brazilian government towards better governance” (OECD, 2017[39]). Historically, SAIs have had limited interaction with citizens but increasingly, there are opportunities for greater civic engagement in monitoring and scrutinising governments’ use of public funds. There are several examples of partnerships in which civil society organizations and SAIs have worked together toward shared goals through social audits, cooperation with journalists and academics, citizen focus groups and others in the United States, Mexico, India, and more (Global Integrity, 2018[98]) (United Nations, 2013[99]). In fact, maintaining public dialogue and encouraging engagement through participatory monitoring and evaluation and audit processes can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the use of public resources by involving more actors in identifying suboptimal use of funds or risks of corruption (Governance and Social Development Resource Centre, 2006[100]).

Several actors including the CGU, SEGOV, Casa Civil and the TCU also have a role to play in policy outcome accountability. This form of accountability places the emphasis less on the process and more on the results of particular policies and so it is usually dependent on setting standards, benchmarks and key criteria in accordance with outlined objectives. Different initiatives that aim to encourage an outcome-oriented approach are for example, internal policy implementation analysis, which anticipates challenges that may arise and lead to failed targets, excessive costs, and even political backlash. Similarly, strategic mid-term planning also exposes the steps behind what may appear to be a successful process which could include uncover corruption, bribery, or a simple mismanagement of funds (OECD, n.d.[101]). The TCU already prioritises policy outcome accountability in many regards and already works to provide insight and foresight, by anticipating the vulnerabilities, challenges and opportunities for the Brazilian government to address integrity risks and systemic vulnerabilities (OECD, 2017[39]) for better outcomes. The CGU, Casa Civil, SEGOV and the TCU could further promote their role regarding these forms of accountability, for example in the President’s Annual Accountability report sent to National Congress and commit to improving “strategic planning and policy making by improving the links between policy interventions and their outcomes & impact” (OECD, n.d.[102]) across the public administration.

Encouraging innovations in accountability at the subnational level

The OECD Questionnaire for Subnational Governments for the Open Government Review of Brazil yielded several good practices from the state and municipal level. For example, the City Hall of Belo Horizonte has a transparency portal with links to the annual balance sheet of government spending, remuneration of public officials, summary records on budget execution, reports of government activities, information on public-private contracts and instructions on accessing information (City Hall of Belo Horizonte, n.d.[103]). The State Government of Rio de Janeiro also shares contracts, bids, and meeting records on its website for public consumption as well as public calls for tenders (State Government of Rio de Janeiro, n.d.[104]). The State Government of Paraíba has a Citizenship Portal with information on government activities relating to health, public security, and environment as well as a direct link to the State Ouvidoria (State Government of Paraíba, n.d.[105]). Similarly, the City Hall of São Paulo provides detailed guidance in simple language on how and when citizens should file a complaint to the Ouvidoria of their municipality (City Hall of São Paulo, n.d.[106]). The City Hall also has a webpage for Public Accountability, where it posts annual balance sheets, and in particular, data on public funding channelled to civil society organisations (City Hall of São Paulo, n.d.[107]).

While the COVID-19 crisis exacerbated many challenges for Brazil, it did also raise some opportunities for innovations in accountability at the national and subnational level (see Box 8.2) that could be emulated both by other states, municipalities, and cities as well as in other public bodies at the federal level. Brazil could work to sustain this momentum and continue the trend of finding new and improved ways of improving oversight processes. One potential platform for sharing experiences and lessons learned in this regard could be through an Open Government Council or an informal open government network, as recommended in Chapter 4 on Governance Mechanisms and Processes.

Box 8.2. COVID-19 in Brazil and innovations in accountability

In combatting the global health, social, and economic crisis presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries have taken unprecedented and wide-ranging measures aimed at curtailing the spread of the virus, often without due legislative process (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2020[108]). In contrast, the pandemic has unveiled “deep-seated inequalities” with many of the most vulnerable population groups being the most disproportionately affected (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2020[108]). Brazil’s response in particular has generated controversy with Médecins Sans Frontières deeming it to be “the worst in the world” (The Guardian, 2021[109]) and the Lowy Institute’s Covid Performance Index giving Brazil the lowest country ranking as of 9 January 2021 (Lowy Institute, 2021[110])1. Increased calls for accountability led to an ongoing Senate probe and investigation (in PT: Comissão Parlamentar de Inquérito - CPI) into President Bolsonaro’s handling of the pandemic in April 2021 (Reuters, 2021[111]). However, Brazil turned the tide with its vaccination programme and has administered a total of 369,527,744 vaccine doses as of 25 February 2022 (World Health Organisation, 2022[112]).

Despite the response of the executive branch, a 2021 study identified a number of promising initiatives on internal control that arose during the pandemic at both the state and federal level (Vinicius de Azevedo Braga, Caldeira and Sabença, 2020[113]). These accountability initiatives linked to the ouvidorias were characterised by “innovation aimed at improving existing structures or practices” while horizontal accountability initiatives “were anticipatory and mission-oriented” (Vinicius de Azevedo Braga, Caldeira and Sabença, 2020[113]). The OECD defines anticipatory innovation governance (AIG) as the “broad-based capacity to actively explore options as part of broader anticipatory governance, with a particular aim of spurring on innovations (novel to the context, implemented and value shifting products, services and processes) connected to uncertain futures in the hopes of shaping the former through the innovative practice” (OECD, 2019[114]). Some interesting examples and good practices at the state level outlined in the aforementioned study illustrate this concept and demonstrate a concrete commitment to enhancing accountability through innovative processes.

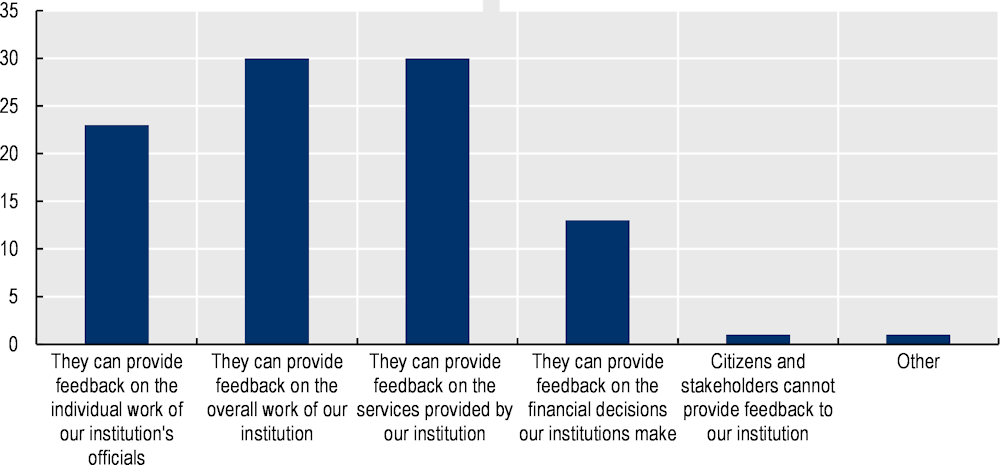

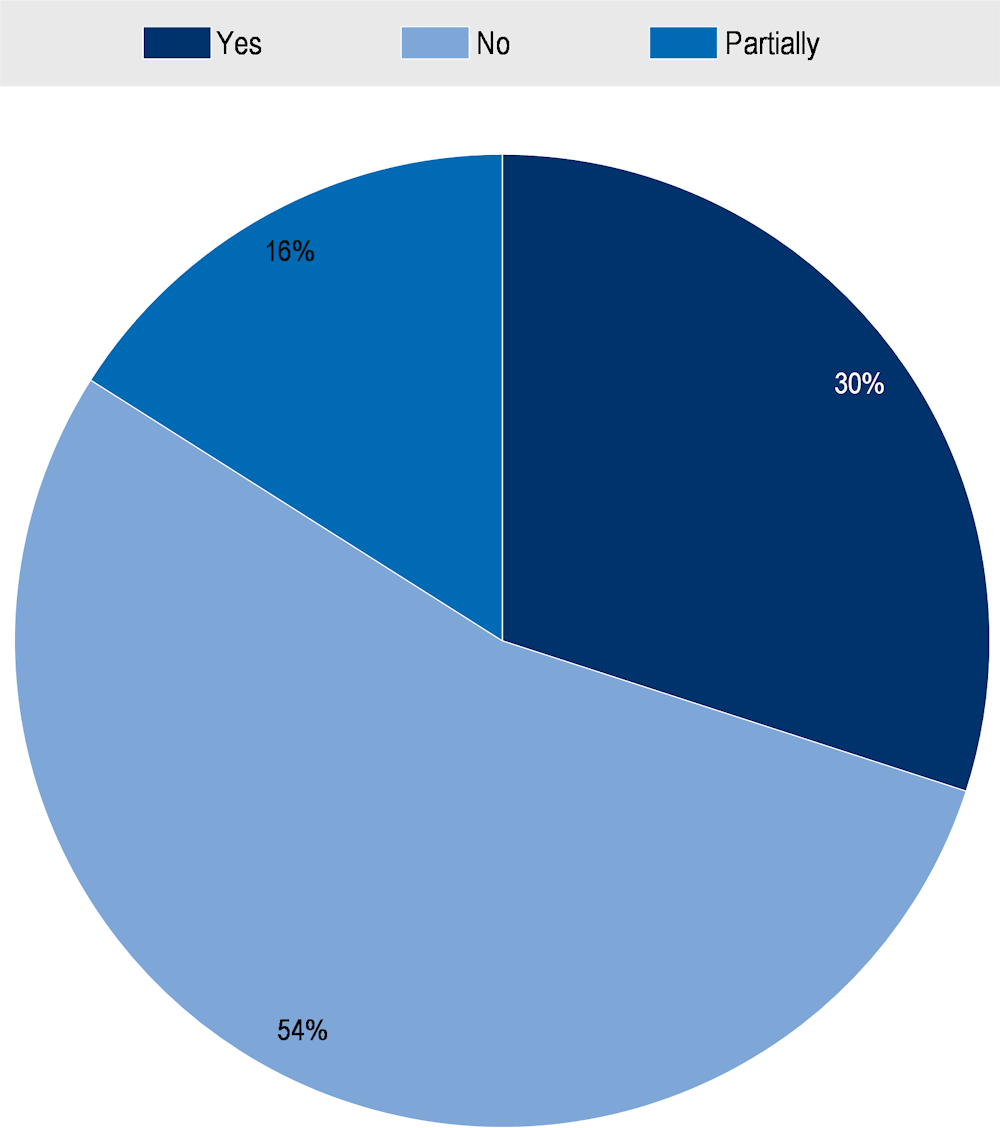

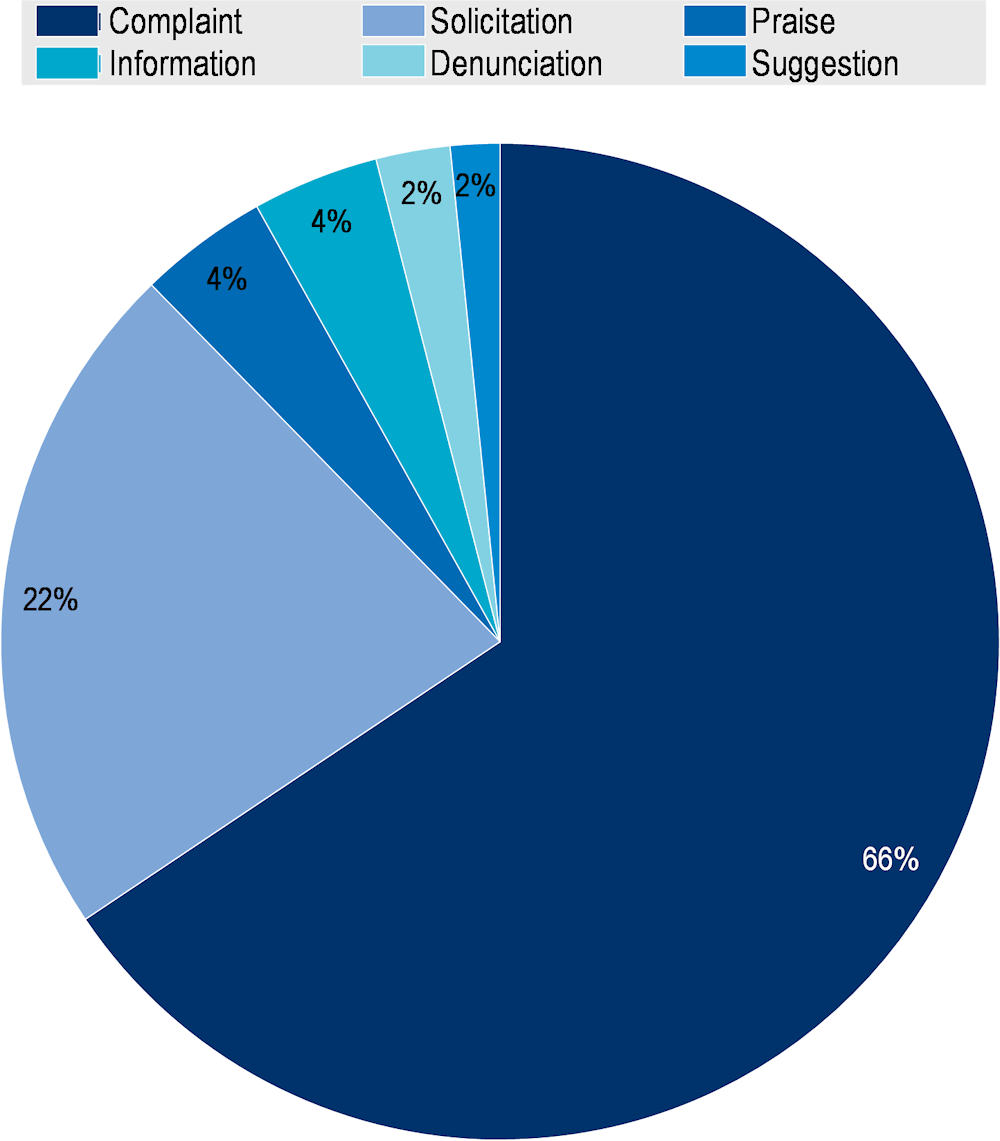

For example, the “Antifake CE” initiative in the State of Ceará was established to find and denounce fake news relating to COVID-19 while “Plantão Coronavirus (Coronavirus On Call)”, a channel on the social media of the Secretariat of Health, redirected requests for accurate information to public officials (Vinicius de Azevedo Braga, Caldeira and Sabença, 2020[113]). Furthermore, the General Comptroller’s Office of the State of Mato Grosso remodelled their “Ask the State General Comptroller” channel and issued bulletins about the status of coronavirus in their area. 11 states also dynamically adapted their internal auditing procedures to the crisis, for example through setting additional alert and risk analysis mechanisms to the creation of specific commissions to this effect. In other states, monitoring and evaluation was also improved through the intensive use of intelligence tools, the simplification of auditing reports, and the creation of specific functionalities in existing portals for demands relating to COVID-19 in particular (Vinicius de Azevedo Braga, Caldeira and Sabença, 2020[113]). São Paulo also had a number of good practices, including Cidade Solidária, which was a partnership between São Paulo City Hall and civil society organisation “to coordinate donations and volunteers to tackle pandemic social and economic effects” (Open Government Partnership, n.d.[115]).