This chapter explains the role of civic space as a facilitator of inclusive and effective open government initiatives. It includes a review of the key institutional, legal and policy frameworks governing civic space in Brazil, followed by an analysis of current implementation challenges and opportunities. It also discusses the enabling environment for civil society organisations. The chapter includes concrete and actionable recommendations for the government of Brazil on strengthening the protection and promotion of civic space.

Open Government Review of Brazil

5. Civic space as an enabler of open government in Brazil

Abstract

Civic space as a facilitator and enabler of open government initiatives

The OECD has been helping countries around the world strengthen their culture of open government by providing policy advice and recommendations on how to integrate the core principles of transparency, accountability, integrity and stakeholder participation into public sector reforms, as discussed. The OECD’s work on civic space – defined as the set of legal, policy, institutional and practical conditions necessary for non-governmental actors to access information and data, express themselves, associate, organise and participate in public life – is a continuation of the same effort and it recognises a healthy civic space as a precondition for and facilitator of open government initiatives. In order to maximise their benefits, and ensure that they achieve their full potential, governments need to guarantee that their civic space is open, protected and promoted through clear policies and legal frameworks that set out the rules of engagement between citizens and the state, framing boundaries, and defending individual freedoms and rights (OECD, 2016[1]).

The OECD approach to civic space

The OECD approach to civic space is anchored in the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (see Box 5.1). Since 2021 following the creation of the OECD Observatory of Civic Space in 2019, all Open Government Reviews include a chapter dedicated to civic space based on the OECD’s analytical framework on civic space that is applied to all member and partner countries adhering to the Recommendation.

By fully integrating civic space into its governance work, the OECD thus supports an expansive and holistic understanding of open government that explicitly recognises the importance of the enabling environment (see Table 5.1) (OECD, 2020[2]). For example, when open government data (OGD)1 are shared by public entities, it is crucial for citizens, journalists and civil society organisations (CSOs) to be able to safely and securely access the data on an equal basis to achieve real transparency and democratise its use and re-use. Similarly, it is critical to have strong legal protections for individual rights, functioning and funded complaints mechanisms, and rule of law to achieve real accountability. Effective participation is only possible when all members of society have an equal chance of being consulted, informed, listened to and of expressing their opinions. OECD countries are raising the bar in terms of creating a more ambitious and impactful context for the next generation of open government initiatives. To support this, they have adopted an all-encompassing analytical framework for civic space that focuses on four core pillars: 1) civic freedoms and rights; 2) the impact of media freedoms and digital rights on civic space; 3) the enabling environment for CSOs; and 4) civic participation (see Table 5.1). This framework places cross-cutting issues such as equality, non-discrimination and inclusion at its core.

Box 5.1. Civic space anchored in the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government explicitly recognises the need to create an enabling environment for open government initiatives and reforms. Four of the Recommendation’s provisions are particularly relevant to civic space.

Provision 1 recognises the need to take measures “in all branches and at all levels of the government, to develop and implement open government strategies and initiatives in collaboration with stakeholders”.

Provision 2 advocates for the need to ensure the “existence and implementation of the necessary open government legal and regulatory framework”, in addition to establishing oversight mechanisms.

Provision 7 stresses the importance of proactively making available “clear, complete, timely, reliable and relevant public sector data and information that is free of cost, available in an open and non-proprietary machine-readable format, easy to find, understand, use and reuse, and disseminated through a multi-channel approach, to be prioritised in consultation with stakeholders.”

Provision 8 recognises the need to grant people “equal and fair opportunities to be informed and consulted” and for them to be actively engaged in all phases of public sector decision making and service design and delivery”. It also advocates for specific efforts to reach out to “the most relevant, vulnerable, under-represented, or marginalised groups in society, while avoiding undue influence and policy capture”.

Provision 9 discusses promoting innovative ways “to effectively engage with stakeholders to source ideas and co-create solutions and seize the opportunities provided by digital government tools”.

Source: OECD (2017[3]).

Increasingly, this comprehensive and holistic approach to open government is being adopted within the wider open government community. For example, in 2021, the Open Government Partnership (OGP) reported that while almost half of national commitments sought to strengthen public participation, few of them tackled the essential pre-conditions for this, namely the protection of freedom of expression, assembly and association (OGP, 2021[4]). In response, it launched a call for action to push its members to tackle systemic inequalities, protect civic space and enhance citizen participation as part of the “Open Renewal” campaign (OGP, 2021[5]). In light of the above, and as a founding member of the OGP, Brazil has an opportunity to move from the current technical, compliance-driven approach to open government to a more comprehensive understanding that recognises the role of protected civic spaces for all members of society, both on line and offline, and as an enabler of its open government agenda. Such a shift would help improve the design, delivery and outcomes of Brazil’s many open government programmes and initiatives with clear benefits for the government and Brazilian society as a whole (OECD, 2017[3]). Furthermore, it would help to realise recent commitments made during the US Summit for Democracy (Brazil, 2021[6]).

Table 5.1. Links between the OECD’s open government principles and civic space

|

Civic space as an enabler of open government reforms |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Transparency |

Accountability |

Integrity |

Participation |

|

Targeted transparency initiatives,1 proactive disclosure of information and data, and two-way communication to gather feedback and encourage dialogue facilitated by a free and open Internet, a healthy media ecosystem, a safe environment for journalists and bloggers, and an enabling environment for CSO and citizen participation are pre‑conditions for government transparency. |

Legal protections and functioning oversight mechanisms, as well as rule of law, are essential to ensure equal access to information and relevant policy discussions and decision making for CSOs and citizens, in addition to (hard) accountability2 for violations of the right to participate and other civic freedoms and rights. |

Targeted transparency initiatives,1 and proactive disclosure of information and data facilitated by a healthy media ecosystem, protection for human rights defenders, activists and whistleblowers, and informed civil society and citizens are pre‑conditions for the prevention of policy capture wherein public decision making is directed away from the public interest. |

Protected individual rights (e.g. freedom of expression, association, assembly, privacy and personal data protection), non discrimination, an enabling environment for CSOs, security and protection for activists and rights defenders, robust information ecosystems, and inclusive and accessible opportunities are preconditions for effective citizen participation in governance and decision making. |

1. Targeted transparency initiatives “have the fundamental characteristic of using information disclosure as a way of achieving a concrete public policy goal, such as improving public service delivery in healthcare, education, and transportation, among other sectors” (Dassen and Cruz Vieyra, 2012[7]).

2. Hard accountability refers to measures that “explicitly name a means of enforcing or brokering compliance”. In other words, there are consequences for failure to comply and the means to achieve relevant aims (Foti, 2021[8]).

Non-linear progress and challenges

As a young democracy, Brazil has come a long way since 1985 in terms of creating an enabling environment for civil society and effective public participation. Indeed, Brazilian civil society is vibrant and diverse, with expertise on a wide range of issues. It has been partnering with the government of Brazil over the decades, playing an increasingly important role in improving policies, engaging in participatory mechanisms, delivering services and helping to increase transparency. However, this path in support of citizen and stakeholder participation is not linear. This chapter identifies Brazil’s progress, as well as challenges and setbacks.

Data and global rankings from leading international think tanks and academics show that fundamental aspects of civic space such as the protection of civic freedoms and rights, press freedom, and the environment for CSOs are under increasing pressure in Brazil. This is taking place alongside challenges to the rule of law2 and decreasing opportunities for effective civic engagement (see Chapter 6) (World Justice Project, 2020[10]; HRMI, 2021[11]; V-Dem Institute, 2021[12]). Reporters Without Borders places Brazil 111th out of 180 countries in its 2021 World Press Freedom Index (Reporters Without Borders, 2021[13]), for example. Similarly, CIVICUS considers civic space to be “obstructed” in Brazil as of 2021 (CIVICUS, 2020[14]).3 The V‑Dem Institute’s Liberal Democracy Index, 4 notes a general democratic decline in its latest report (V-Dem Institute, 2021[12]).5

Yet the legal basis for protecting civic space is fairly well established in Brazil, although with recent notable setbacks and exceptions (see Section 5.2). The Constitution provides far-reaching legal guarantees related to civic space, in addition to regulating the relationship between citizens and the state. It describes its intention to “institute a democratic state destined to ensure the exercise of social and individual rights, liberty, security, well-being, development, equality and justice as supreme values of a fraternal, pluralist and unprejudiced society”. It guarantees all those residing in the country key rights, including access to information; freedom of expression, assembly and association; the right to privacy; press freedom; and equality (Library of Congress, 2020[15]). It also guarantees the defence of indigenous persons’ rights and interests (Art. 129); a range of participation rights for individuals, communities, representative groups and CSOs (Art. 10, 58, 79, 82, 194, 198, 204, 216, 227, 231); and environmental rights on the basis of the environment being a “public good for the peoples’ use” (Art. 225). Some of these guarantees are further regulated by federal laws (Library of Congress, 2020[15]). As such, the Constitution forms the bedrock for civic space protections in Brazil and, potentially, for a more ambitious vision for open government.

Brazil also has a National Programme for Human Rights since 1996, which was reviewed in 2002 and 2009, always in consultation with civil society (Government of Brazil, 2009[16]). Its third edition includes as guiding pillars the “democratic interaction between state and civil society”, “development and human rights”, “universalisation of rights in a context of inequalities”, “public security, access to justice and fight against violence”, “human rights education and culture”, and “the right to memory and truth”. A fourth edition of the programme is being considered and a working group composed of government representatives was established in February 2021 to undertake an “ex ante evaluation” of the national human rights policy and provide recommendations for the improvement of its programmes (Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights, 2021[17]). The ministry considers this as “a moment of reflection, diagnosis and evaluation” where it plans “to discuss problems, causes and solutions” to be discussed with civil society in a following stage.6

However, despite this robust foundation, implementation of civic freedoms and rights on an equal basis remains challenging. Some obstacles are long term and particularly complex given Brazil’s history, size and administrative organisation, whereas others have become more prominent in recent years. The rest of this chapter discusses the key legal and policy frameworks governing three of the OECD’s core pillars of civic space – civic freedoms and rights, media freedoms and digital rights and the enabling environment for civil society (as per Table 5.1) - followed by a detailed review of current implementation challenges and opportunities with accompanying recommendations. The recommendations provide a range of practical measures that Brazil can take to protect its civic spaces, both online and offline. They are aimed at a broad range of state institutions and some will require cross-government discussions and approaches, in which the CGU is well placed to play a leadership and coordination role. The fourth pillar of civic space – public participation – is discussed in detail in Chapter 6.

Legal frameworks governing civic freedoms and rights, media freedoms, and digital rights in Brazil

Similar to the vast majority of OECD countries, Brazil has adopted legislation to reflect and ratify the provisions of several key international and regional treaties and conventions governing civic freedoms and rights.7 Core rights related to civic space are largely protected in the Constitution and legislation, with some laws even praised internationally (UNIFEM, 2008[18]; IACHR, 2021[19]). Although legislation governing fundamental rights has improved substantially as a result of the 1988 Constitution, there are however concerns about a recent increase in activity by the executive, mainly through the approval of decrees and provisional measures.8 Organisations consulted as part of this review expressed concerns about the number of new bills in congress that address issues of high relevance for citizens, the speed with which they are being proposed and approved, and the few opportunities for non-governmental stakeholders to engage in relevant debates and decision making. They fear that this side-lines the legislature as an independent body in charge of law making where inclusive debate and collaborative drafting had been gaining ground over the years and that hard-won rights related to civic space, including on the protection of civic freedoms in addition to public security and the rights of indigenous peoples – some of which were won after decades of national struggle and debate – are increasingly under threat.9

Freedom of peaceful assembly and association

Freedom of peaceful assembly is protected by the Constitution. Article 5 states that all persons may hold peaceful meetings, without weapons, in places open to the public, without need for authorisation, so long as they do not interfere with another meeting previously called for at the same place, subject only to prior notice to the relevant authority (Item XVI). This is generally in line with legislation found in OECD Member States, although it is rare for the handling of simultaneous or counter-demonstrations to be set out in constitutions. Although more than 70 bills have been proposed over the years to elaborate this right further, none have become federal law (Article19, n.a.[20]), which may lead to inconsistent and potentially arbitrary handling of assemblies in practice. Some municipalities and states regulate practices related to protests, however, such as a 2019 decree from the state of São Paulo that prohibits the use of masks in protests and requires five days’ advance notice from organisers (Legislative Assembly of the State of São Paulo, 2019[21]; Article19, 2020[22]). In 2021, the Supreme Federal Court ruled that meetings and demonstrations are permitted in public places regardless of prior official communication to the authorities (Supreme Federal Court, 2021[23]), which reflects the practice in many OECD countries, and also international human rights standards as stipulated by the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, whereby the failure to notify an assembly beforehand does not by itself justify an interference with the assembly, especially if it remains peaceful. According to the court ruling, “the constitutional requirement of prior notice is satisfied by the dissemination of information that allows public authorities to ensure that its exercise takes place in a peaceful manner or that it does not frustrate another meeting in the same place”, not having to be an official communication.

Article 5 of the Constitution also foresees total freedom of association for lawful purposes, except for paramilitary association (Item XVII). Associations can be created independent of government authorisation, and state interference in their functioning is explicitly forbidden (Item XVIII); this corresponds with law and practice in many OECD countries and is essential to creating an enabling environment for civic space. Associations have legitimacy to represent their members judicially or extra judicially, when expressly authorised10 (Item XXI). The Civil Code further regulates the establishment and operations of associations, companies and foundations (see Section 5.4.1 for a more detailed review of legal frameworks governing associations) (Government of Brazil, 2002[24]).

Ongoing reviews of the Anti-Terrorism Law (Law 13260/2016) and National Security Law (Law 7170/1983) (see Box 5.2) may also have an impact on freedom of assembly and association.

Freedom of expression/speech

Article 5 of the Constitution sets forth several principles related to freedom of expression, including that no one shall be compelled to do or refrain from doing something except by force of law (Item II) and that manifestation of thought is free, but anonymity is forbidden (Item IV). Expression of intellectual, artistic, scientific and communication activity is also free and independent of any censorship or license (Item IX). Article 220 further determines that the expression of thoughts, creation, speech and information, through whatever form, process or vehicle, must not be subject to any restrictions (Library of Congress, 2020[15]), which is similar to provisions found in constitutions and laws of OECD Member States.

Freedom of expression excludes slander, defamation and injury, which are considered crimes against honour and are subject to imprisonment11 (Government of Brazil, 1940[25]). This is contrary to findings of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which has stated that imposing excessively punitive sanctions such as prison sentences in defamation cases is a disproportionate interference with individuals’ freedom of expression.12 The UN Human Rights Committee has also generally urged states to decriminalize defamation13 (although numerous OECD countries still criminalise it). Freedom of expression also excludes discrimination, with some practices also punishable by imprisonment (Government of Brazil, 1995[26]). Article 208 of the Brazilian Criminal Code considers publicly mocking someone on the grounds of belief or religious function, preventing or disrupting a ceremony or the practice of religious worship, or publicly vilifying an act or object of religious worship to be punishable crimes with between one month and one year of imprisonment or a fine. As stated by different UN bodies, such legislation should not be used to prevent or punish criticism of religious leaders or commentary on religious doctrine and tenets of faith14; it follows that this form of interpreting the law would limit civic space and freedom of expression in general. Legislation regulating freedom of expression of thought and information, Law 5250, dates back to 1967. In 2010, the Supreme Federal Court stated that “Law 5250/1967 does not seem to serve the standard of democracy and press that emerged from the drafting board of the Constituent Assembly of 87/88. However, the total suspension of its effectiveness harms press freedom itself” (Supreme Federal Court, 2010[27]).

Ongoing reviews of the Anti-Terrorism Law (Law 13260/2016) and National Security Law (Law 7170/1983) (see Box 5.2) may also have an impact on freedom of expression.

Press freedom

The 1988 Constitution guarantees press freedom, stating that “the manifestation of thought, creation, expression and information, in any form, process or vehicle shall not be subject to any restriction” (Art. 220). The same article specifies that “no law shall contain any provision that may constitute an obstacle to full freedom of journalistic information in any media vehicle” (§1), that “any and all censorship of a political, ideological and artistic nature shall be forbidden” (§2), and that “the publication of a printed communication vehicle is independent of license from the authority” (§6). Regulations on content, ownership and licences are also included, entrusting the executive with the right to grant and renew concessions, permissions and authorisations for sound and image broadcasting services (Art. 220-223). The 2020 OECD Telecommunication and Broadcasting Review of Brazil found that the country had strengthened its legal and regulatory communication framework in recent years, but that important weaknesses remain, including a complex licensing regime that raises barriers to market entry and may lead to regulatory arbitrage (OECD, 2020[28]). Thus, while generally legislation seems to meet the positive obligation to protect media freedoms, guarantee respect for media independence, and promote media diversity that a variety of international human rights bodies have imposed on states, the above obstacles to market entry and thus to media diversity weaken that aspect of civic space.

The Constitution does not mention any exceptions to press freedom, but anonymity is forbidden (Art. 5, Item IV). Slander, defamation and injury are crimes under the Criminal Code (Art. 138-140), as is publicly inciting crime (Art. 286). The only legislation specifically governing press freedom is from 1953, pre-dating the military regime (Government of Brazil, 1953[29]). A second legislation dating from 1967 regulates freedom of expression of thought and information (Government of Brazil, 1967[30]). In a positive step, two bills were introduced in Congress in 2020 to increase protection for journalists and press freedom more generally (Chamber of Deputies, 2020[31]). Bill PL2378 proposes the criminalisation of conduct that prevents the free exercise of journalism, and Bill PL2393 proposes an increase of penalties for physical injuries committed against media professionals in the exercise of their professional duties or because of them. These were being debated by parliament at the time of writing.

Privacy, data protection and cybersecurity

Article 5 of the Constitution affirms everyone’s right to privacy (Items X-XI) and the confidentiality of correspondence, data and communications, except for law enforcement and criminal investigation purposes (Item XII), which is largely in line with legislation found in OECD Member States. The Civil Code also guarantees the inviolability of private life (Art. 21) (Government of Brazil, 2002[24]). In a significant development in October 2021, the Senate approved an amendment to the Constitution (PEC 17/2019) which makes the protection of personal data, including in digital media, a fundamental right. The proposal has yet to be approved by the National Congress.

Brazil’s Personal Data Protection Law (Law 13709) was passed in 2018 and came into force in 2020. Its purpose is to regulate the use and sharing of personal data, in addition to access, and to protect citizens from any misuse of their personal information. It specifies exceptions for the purpose of public security, national defence, state security, criminal investigation and for data originating from abroad under certain circumstances15 (Art. 4, Item III). Exceptions also include the treatment of personal data carried out exclusively for journalistic, artistic or academic purposes (Art. 4, Item II) and for research by public health authorities, with anonymisation or pseudonymisation of the data where possible (Art. 13). This law also reflects data protection legislation in OECD countries, notably in Europe and other Latin American countries, and contains important safeguards to help enhance civic space.

Decree 10222 of 2020 approved the National Cyber Security Strategy for the period 2020-23. It describes the government’s strategic objectives regarding cybersecurity and proposes several actions to achieve them, such as establishing minimum cybersecurity requirements in public procurement, encouraging the use of cryptographic resources for communication of sensitive matters and developing regulations on emerging technologies. Law 14155, approved in 2021, provides heavier penalties for cybercrimes, such as device hacking, theft and swindling committed electronically or via the Internet. This refers to breaking into someone’s electronic device in order to obtain, alter or destroy data or information without the user’s authorisation.

Open Internet

The 2014 Civil Rights Framework for the Internet (Marco Civil da Internet, Law 12965) establishes the principles, guarantees, rights and duties underpinning Internet use in Brazil. It foresees access to the Internet as a right for all and as essential to the exercise of citizenry, and thereby implements standards established by various international actors, which have emphasised states’ obligations to promote and facilitate universal Internet access by having relevant regulatory mechanisms, providing support, promoting awareness, and ensuring equitable access.16 Article 3 of the law states that “the discipline of internet use in Brazil has the following principles: guarantee of freedom of expression, communication and manifestation of thought, protection of privacy, protection of personal data”, among others. These principles are an important step towards protecting and maintaining civic space.

Box 5.2. Replacing Brazil’s National Security Law and Anti-Terrorism Law

Brazil’s National Security Law (Law 7170/1983) dates from the end of the military rule and defines crimes against national security and political and social order. A bill revoking the law notes that it is “incompatible with the democratic regime embodied in the 1988 Constitution”. Political parties and senators, among others, have voiced their concerns about it violating Brazil’s democratic rule of law, in addition to freedoms of expression and thought. It is also deemed problematic due to its vague wording, harsh penalties and for its perception of protesters as a threat. The Inter-American Commission’s Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression has noted with concern the increase in prosecutions of journalists, using the National Security Law. Projects to revoke it have existed since 1991, culminating in 2021, when the revocation process was finally approved by the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate and sanctioned by the President.

The bill revoking the National Security Law (PL 6764/2002 in the Chamber of Deputies and PL 2108/2021 in the Senate)1 included in its proposal the addition of a set of crimes to the Penal Code considered as “crimes against the democratic state of law”. In a joint letter sent in 2021, 67 civil society organisations (CSOs) asked for different sectors of Brazilian society to be included in the development of the bill and raised concerns about the text, including about the use of imprecise concepts that risked the criminalisation of protests and threatened freedom of expression. Public audiences and meetings were held with CSOs as a result, and the text was revised several times, leading to a better definition of terms and the inclusion of an article stating that “it is not considered a crime to criticise constitutional powers or journalistic activity or claim constitutional rights and guarantees through marches, meetings, strikes, crowds or any other form of political manifestation with social purposes”. This was seen as an important achievement by civil society, although some of the other articles in the bill that were drafted with public participation were vetoed. This included articles that classified the promotion of misleading mass communication and the prevention of the right to demonstrate as crimes, with significant implications for the right to peaceful assembly and the protection of civic space more broadly. In September 2021, the bill was enacted into Law 14197/2021.

The Anti-Terrorism Law (Law 13260/2016) defines terrorist organisations and addresses investigative and procedural provisions to counter terrorism. Brazil also recognises that it needs to be revised and Congress is currently discussing more than 20 bills to amend it. However, the Federal Prosecutor’s Office for Citizens’ Rights has expressed concerns about new measures foreseen in some of these bills, stating that “vague provisions brought in by the proposals may impact fundamental freedoms of expression, demonstration and protest”. This and other concerns were included in an appeal by a group of CSOs to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2019. A letter from United Nations’ rapporteurs to the Brazilian government in 2021 shared reservations about the bills, noting that “this change may lead to limitations on the exercise of fundamental freedoms, including those of opinion, expression, and association and remove protection for civil society actors and human rights defenders”.

One of these bills (Draft Bill 1595/2019) has been opposed by the National Association of Federal Prosecutors and a wide range of police associations.2 It is also opposed by civil society groups, in particular because it enlarges the powers of the executive to take actions against “preparatory acts” of terrorism (Art. 1). Civil society is also concerned about a number of the bill’s articles related to infiltration, surveillance, monitoring and intelligence gathering measures (Art. 5, 6); scenarios in which agents might not be prosecutable (Art. 13); the absence of safeguards for data sharing among different state actors (Art. 14, 15); the absence of external control by civil society of related actions by the state (Art. 17); and the risk of creating incentives for banks and financial institutions to create obstacles to international funding of CSOs (Art. 23) as part of measures to curb financing of terrorism.3 Another bill, 272/2016, also broadens the concept of “terrorism”, using imprecise language to define terrorist acts (Federal Senate, 2016[32]). CSOs note that some of these bills are being classified as urgent and have not been discussed with civil society representatives.

The introduction of broad and imprecise terminology in security and counterterrorism legislation has been central to the closure of civic space and restrictions on civil society across the globe, leading to the arbitrary application of laws and the criminalisation of otherwise peaceful and legitimate activities. OECD. It is crucial that civil society groups are systematically engaged in developing and revising the above laws and in conducting human rights impact evaluations on them in an inclusive and comprehensive manner to ensure they do not negatively impact civic space.

1. Bills to revoke the National Security Law changed the numbering and other bills were attached to the text over the years.

2. Contributions received on 23 September 2021.

3. Contributions received on 20 and 23 September 2021.

Sources: Government of Brazil (1983[33]; 2016[34]; 2021[35]); Federal Senate (2021[36]); Chamber of Deputies (2020[37]; 2020[38]; 2019[39]); Article19 (2021[40]); Pacto pela Democracia (2021[41]); Conectas (2021[42]); Federal Prosecutor’s Office for Citizen’s Rights (2020[43]); Article19 et al. (2019[44]); OHCHR (2021[45]; 2021[46]); OECD (2021[47]); (Supreme Federal Court, 2021[48]); (Vilarreal, 2021[49]). Contributions to the OECD public consultation on civic space received on 28 February 2021 and 30 March 2021.

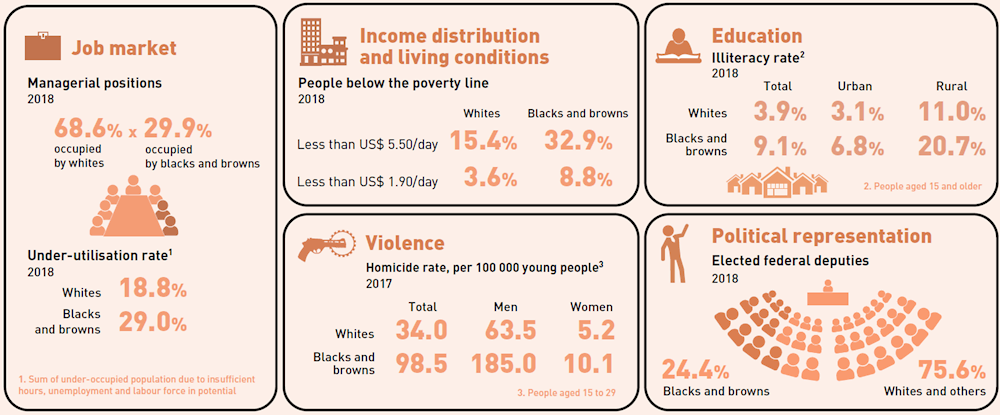

Equality and non-discrimination

As mentioned above, equality and non-discrimination are cross-cutting themes in the OECD’s civic space work as essential preconditions for inclusive and responsive public participation. Also, the discussion on the representativeness and inclusiveness of data is increasingly permeating the policy discourse across OECD countries,17 thus leading to specific actions to ensure that the data generated by the public entities reflects the realities of all population groups (e.g. minorities, indigeneous communities) so that there are no hidden inequalities in the data (see Chapter 9 on Open Government Data).

As such, this chapter includes a review of frameworks related to Afro-Brazilians, women, indigenous and LGBTI (i.e. lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex) persons, as groups that are particularly at risk of discrimination and discriminatory violence. Inclusive policymaking and socio-economic development are among the founding principles of the OECD (OECD, 2020[50]). In the context of Open Government Reviews, discriminatory practices are assessed as they affect people’s relationship with the state, in addition to their ability and willingness to engage with public institutions if they feel undervalued, excluded, unprotected or threatened by them.

One of the fundamental objectives of Brazil as a country, as stated in its Constitution, is to promote the well-being of all, without prejudice as to origin, race, sex, colour, age or any other form of discrimination. Article 5 sets forth that “all are equal before the law, without distinction of any nature”. It further states that men and women have equal rights and duties (Item I) and that no one shall be deprived of any rights because of their religious beliefs or philosophical or political convictions18 (Item VIII). These general equality and non-discrimination principles are in line with those found in the legislation of OECD Member States. The Criminal Code states that injury referring to race, colour, ethnicity, religion, origin, or the condition of elderly or handicapped persons may be sanctioned by one to three years of imprisonment and a fine (Art. 140 §3) (Government of Brazil, 1940[25]). Non-discrimination of specific groups is further regulated by federal law, examples of which are discussed below. Law 7716 of 1989 defines crimes resulting from discrimination or prejudice based on race and colour19. There is no specific mention of sexual orientation in these laws.

Racial equality

The Racial Equality Statute (Estatuto da Igualdade Racial), created by Law 12288 in 2010, was an important step in addressing Brazil’s well-documented history of racial discrimination (Government of Brazil, 2010[51]; Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights, 2018[52]). It was designed to guarantee equal opportunities to people of African descent, protect ethnic rights, and fight discrimination and other forms of ethnic intolerance (Art. 1). According to the law, any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin intending to annul or restrict the equal recognition, enjoyment or exercise of human rights and fundamental freedoms is considered racial or ethnic racial discrimination (Art. 1, Item 1).

Racism is a non-bailable crime with no statute of limitations and implies discriminatory conduct directed at a certain group (National Justice Council, 2015[53]; Government of Brazil, 1989[54]). Law 7716 of 1989 frames racism in terms of specific actions, such as refusing or preventing access to a commercial establishment, preventing access to social entrances in public or residential buildings and lifts, and denying or preventing employment in a private company, among others. Racial injury is a separate crime, usually associated with the use of derogatory words referring to race or colour with the intention of offending a person’s honour (National Justice Council, 2015[53]). Different from racism, racial injury is bailable, is subject to a statute of limitations and a conditional suspension of sentence is possible. A bill was proposed in 2020 to classify racial injury as a crime of racism, upgrading its status and making it non-bailable and with no statute of limitations. It was still under consideration at the time of writing (Chamber of Deputies, 2021[55]).

Challenges related to racial inequality have long been recognised in Brazil and quotas aimed at reducing educational disparities among people of different races and social backgrounds have been implemented by various governments since 2000. Since 2016, federal public universities are required by law (Government of Brazil, 2012[56]) to allocate at least half of their slots to students from public schools and these should be filled by Afro-Brazilians, indigenous and disabled people, reflecting at a minimum the proportion of the population that each group represents. Quotas for Afro-descendants in entry exams for the public service are also foreseen by law (Government of Brazil, 2014[57]). In 2020, the Superior Electoral Court also decided on affirmative measures to support racial equality in electoral campaigns starting with the 2022 elections (Superior Electoral Court, 2020[58]). In a further positive step, in May 2021 Brazil ratified the Inter-American Convention against Racism, Racial Discrimination and Related Forms of Intolerance.

Gender equality and women’s rights

The first item of Article 5 of the Constitution states that “men and women are equal in rights and obligations”, which reflects the wording of key international instruments ratified by Brazil, as well as the constitutions of many OECD Member States. One of the first legislations affecting gender equality, Law 6515, was introduced in 1977. It instituted the same divorce procedure for men and women (Government of Brazil, 1977[59]). Maternity and paternity paid leave was established in the 1990s with the approval of several laws (Government of Brazil, 1991[60]; 1994[61]; 1999[62]). Affirmative action on women’s participation in electoral processes has been foreseen by law for years (Government of Brazil, 1997[63]). Political parties are also obliged to set aside funds to finance electoral campaigns for their female candidates (Government of Brazil, 2015[64]). Even so, the percentage of Women in the Chamber of Deputies remains at 15% (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2021[65]), well below the average of 32% across OECD countries in 202120 (OECD, 2021[66]).

An area in which progress has been made is the legal framework concerning violence against women. The main legal framework is Law 11340 of 2006 (the “Maria da Penha” Law), which was considered a milestone in countering violence against women in Brazil when it was introduced (UNIFEM, 2008[18]). The law criminalised domestic violence, with a penalty of up to three years’ imprisonment and no possibility of conversion into fines or public services, which was possible prior to the law. The law also defined other forms of aggression beyond physical violence, such as psychological, sexual, patrimonial21 and moral22 aggression. It created measures to prevent such crimes and to protect victims, including the removal of the victim or the aggressor from a specific location and the possibility of preventive arrest of the aggressor.

Several amendments have been made to this law, including on the preferential care of victims by female police officers (Government of Brazil, 2017[67]), the imprisonment of aggressors for non‑compliance with protective measures (Government of Brazil, 2018[68]), and the criminalisation of recording of private or sexual content without the consent of all concerned parties (Government of Brazil, 2018[69]). In a positive step, Law 13104 of 2015 also introduced femicide into the Brazilian Penal Code as a particular category of homicide, thereby increasing the sentence in some cases,23 and making gender-based violence of women more visible. A homicide is now considered femicide when the crime involves domestic and family violence and/or discrimination against a woman because of her sex.

In another positive step, the 2017 Labour Law reform, Law 13467/2017, included an article stating that salaries could not be differentiated on the basis of gender and foreseeing a fine and the payment of the difference in such cases (Art. 461).

Indigenous rights

The Constitution recognises indigenous people’s social organisation, customs, languages, beliefs and traditions, as well as their rights over the land they traditionally occupy (Art. 231). This marked a shift from the idea of integration and assimilation of indigenous culture foreseen in the 1973 “Indigenous Statute” (Government of Brazil, 1973[70]) to one of preservation and protection. In the three decades since the 1988 Constitution was introduced, a series of decrees, amendments and laws have also been passed to regulate the constitutional provisions and to protect indigenous people’s rights, culture and land (Public Prosecutor's Office, 2019[71]; FUNAI, 2020[72]). Decree 1775 of 1996 regulated the demarcation of indigenous land by the state, with a key role given to the federal agency for indigenous assistance, currently the National Indian Foundation. The 2002 Civil Code (Government of Brazil, 2002[24]) removed a reference to indigenous peoples as being “relatively incapable” which had been included in the 1916 version (Art. 6, Item III) (Government of Brazil, 1916[73]). Decree 5051 of 2004 ratified the International Labour Organization’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, stating among other things that indigenous and tribal peoples have the right to be consulted about administrative or legislative decisions affecting their collective rights and ways of life, including over their land.

A key bill introduced in 2007 (PL490/2007) and a package of 13 other associated bills since then have sought to change the legal framework governing the demarcation of indigenous land (Chamber of Deputies, 2007[74]; 2021[75]). These include a proposal to establish 1988 as a “temporal mark” for the definition of protected areas, which means that indigenous people seeking protection of their territories had to have been occupying the land in 1988. It also proposes to shift the responsibility for demarcating land from the National Indian Foundation to the National Congress. Another proposal includes the possibility of “contracts aiming at cooperation between indigenous and non-indigenous for economic activities,” including agro-sylvo-pastoral, in indigenous lands, which contradicts a constitutional article that “occupation, ownership and possession” of indigenous lands “or the exploitation of the natural wealth of the soil, rivers and lakes existing therein, are null and void, not producing legal effects, except in the case of relevant public interest of the Federal Government” (Art. 231, § 6) (Government of Brazil, 1988[76]; Instituto Socioambiental, 2021[77]). CSOs have raised a series of concerns about the potential impact of these bills, including that they violate constitutionally guaranteed rights, such as the permanent possession of indigenous lands and the exclusive right to natural resources (Instituto Socioambiental, 2021[78]; APIB, 2021[79]; Indigenous Missionary Council, 2021[80]; de Aguiar, 2021[81]). The package was approved by a commission from the Chamber of Deputies in June 2021 but has not yet been voted on in plenary or by the Senate (Chamber of Deputies, 2021[82]).

LGBTI rights

There is no explicit protective legal framework for LGBTI people in Brazil, although rights for this group have been strengthened over the past two decades. Since 2002, gender reassignment surgery is authorised by the Federal Council of Medicine and is offered by the Brazilian Unified Health System since 2008, for example (National Health Council, 2017[83]). Supreme Federal Court decisions are also notable, including the legal recognition of same-sex unions in 2011 (Supreme Federal Court, 2011[84]; 2011[85]) and the framing in 2019 of homophobia and transphobia practices as a type of racism, covered by Law 7716 of 1989 (Government of Brazil, 1989[54]; Supreme Federal Court, 2019[86]). Government decrees also recognise transvestites’ and transsexuals’ gender identities and allow them to use a different name in the civil registry, including on identity cards (Government of Brazil, 2016[87]; 2018[88]).

Challenges and recommendations on the implementation of civic freedoms and rights, media freedoms, and digital rights in Brazil

Although civic space has a strong legal foundation in Brazil, Brazilians face considerable barriers in exercising related rights in practice, thereby preventing them from effectively participating in policy making and decision making, and in engaging with government institutions on a full and equal basis. This section discusses crucial challenges and recommends ways to address them.

Protecting freedom of peaceful assembly

While the right to freedom of peaceful assembly is guaranteed in the Constitution (see Section 5.2.1), there is no specific legislation detailing what this right includes or how it should be implemented (Peaceful Assembly Worldwide, 2021[89]; Article19, 2014[90]).

In an effort to respond to this gap, in 2017, the Brazilian National Council for Human Rights, the Prosecutor’s Office and the Federal Prosecutor’s Office for Citizens’ Rights participated in drafting Guidelines for Observing Demonstrations and Social Protests, led by the Regional Office for South America of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, together with other institutions in the region (Regional Office for South America of the OHCHR, 2017[91]). The document acknowledges protests as a fundamental element of democratic societies and an essential instrument for the protection and promotion of rights, recognising that many rights have been achieved over the years thanks to public expression of collective demands. It presents international norms for demonstrations and social protests, and offers guidelines for citizens monitoring demonstrations. It does not, however, provide practical guidance to organisers nor to public security entities. It is also hardly referenced by civil society or in the media, indicating that it may not be well known, and as a result, may be narrowly used.

The number of protests arising from social discontent has increased in the LAC region since 2014 (OECD, forthcoming[92]). High social inequality and the perception of widespread corruption are some of the drivers of protests across the region. Although the right to peaceful assembly is generally respected in Brazil, law enforcement officials sometimes employ excessive force against demonstrators (Peaceful Assembly Worldwide, 2021[89]). For example, during nationwide public demonstrations against public transport fares in June 2013, documented violations included the excessive and indiscriminate use of lethal and non-lethal weapons, the disproportionate use of force, and arbitrary arrests, in addition to intimidation practices such as recording and photographing of protestors (National Council for Human Rights, 2017[93]; Article19, 2013[94]; 2013[95]). In 2017, protests against labour and pension reforms in Brasilia were met with the use of lethal weapons by the armed forces, which were called upon to contain the demonstrations (Vettorazzo et al., 2017[96]). In the context of the 2018 elections, electoral courts banned protests at several universities, where protests were interrupted by the police and posters and materials removed (Folha de São Paulo, 2018[97]). After several days of unrest, the Supreme Federal Court annulled the decision by the electoral justice and reiterated that “universities are spaces of freedom and of personal and political liberation” (Supreme Federal Court, 2018[98]). In 2021, several anti‑government protests in over 100 cities were also met with a violent response from the police (Dielú, 2021[99]; BBC, 2021[100]).

Law enforcement agents are required by law to prioritise less offensive instruments over lethal weapons and to use force following the principles of legality, necessity, reasonableness and proportionality, according to Law 13060 of 22 December 2014 (Government of Brazil, 2014[101]). The use of firearms is prohibited against a person on the run who is unarmed, or who does not present “an immediate risk of death or injury to public security agents or third parties” and training for security agents should include content that enables them to use non-lethal instruments, defined as having a “low probability of causing death or permanent injury, temporarily contain, weaken or disable people” (Articles 2 and 3). Furthermore, when injury occurs, medical assistance must be ensured and there is an obligation to communicate what happened to the person’s family or other indicated person (Article 6). Nonetheless, the use of non-lethal armaments typically used in protests, such as rubber bullets, tear gas grenades and other crowd control weapons, has been disproportionate and reportedly caused severe injury (PHR and INCLO, 2016[102]). The use of rubber bullets has resulted in the loss of eyesight of protestors on various occasions in Brazil (Borges Teixeira, 2020[103]; Tomaz and Araújo, 2018[104]; G1, 2016[105]). CSOs have been calling for a ban on their use based on the fact that they are not accurate and can cause significant injury, including to innocent bystanders (Amnesty International, 2015[106]) (Article19, 2021[107]).

In a positive step, in June 2021, the Supreme Federal Court ruled that it is the state’s duty to compensate media professionals who are injured by police officers during news coverage of demonstrations in which there is conflict between the police and demonstrators (Supreme Federal Court, 2021[108]). This followed an appeal by a photojournalist shot in the left eye by a rubber bullet fired by the military police while he was covering a protest in São Paulo in 2000. The injury resulted in the loss of 90% of his vision.

Lessons may also be learnt from practice in neighbouring Colombia, where the government adopted a notable protocol in 2018 for the co-ordination of actions aimed at ensuring a favourable environment for the exercise of peaceful assembly (Colombian Ministry of Interior, 2018[109]). The protocol lists actions that can be taken by authorities before, during and after protests, to protect the right to peaceful assembly, including on the permitted use of force and in the case of disruptions. It has a section about the role of the police in the context of protests, with information about when and how they should intervene. Civil society verification commissions are foreseen in the protocol with the objective of monitoring and verifying that the right of peaceful assembly is being guaranteed and protected. An evaluation after each protest is also proposed, taking into account analysis and documents provided by civil society.

Recommendations

As a cornerstone of democracy, and a key means for citizens to express their views on matters of public importance, it is key for Brazil to consistently protect the right to peaceful assembly. International guidance in this area states that governments have an obligation not just to refrain from violating the rights of those assembling but to actively ensure their rights and to facilitate and enable assemblies. Even when such gatherings turn violent and participants forego the right to peaceful assembly, they still retain other rights, subject to normal limitations, such as those of freedom of expression, association and belief; participation in the conduct of peaceful affairs; bodily integrity; privacy; and an effective remedy for violations of rights (United Nations General Assembly, 2016[110]). The principles of legality, precaution, necessity, proportionality and accountability are central to the right of peaceful assembly, so that force is only used when “strictly unavoidable”, that there is a formal approval and deployment process for any weaponry and equipment used, and that when the use of force is unavoidable, that its harmful consequences are minimised (United Nations General Assembly, 2016[110]).

Consider developing a detailed protocol, in partnership with civil society, on implementation of the right to peaceful assembly in order to ban the use of indiscriminate force and to ensure a consistently favourable environment for the exercise of this right.

Rules on the use of non-lethal weapons as a last resort could be included (e.g. areas of the body to be avoided, when not to use such weapons, the need to warn people before such weapons are used) in addition to details on actions to be taken in case of violence or conflict without affecting other peaceful demonstrators or hindering their right to protest. It could also include preferred techniques to contain violence, in addition to guidance on methods to be avoided, and a ban on certain types of weapons.

Sustained, specific and compulsory training for police on the contents of such a protocol, including on crowd facilitation, planning, coordination and dispersal methods, will be key.

Make practical information available to citizens regarding their rights when organising public meetings and demonstrations, including on: who has the right to organise assemblies; limitations to this right; any prior notification required; regulations regarding interventions, interruptions or relocations by police; legal frameworks regarding apprehensions and the use of force by police; regulations regarding the use of drones; and other frequently asked questions in the Brazilian context. This could be in the form of a web page, for example, which is extensively promoted and outlines Brazil’s commitment to protecting the right to peaceful assembly, in addition to the duties and responsibilities of protestors.

Ensure that any abuse by police or other law enforcement agent is thoroughly investigated and prosecuted in a timely and efficient manner.

Undertake a thorough review to ensure that relevant subnational legislation is in line with international standards.

Challenges related to the right to association are addressed in Section 5.5.

Protecting freedom of expression

Freedom of expression is another cornerstone of civic space. It is guaranteed under the Brazilian Constitution and the government acknowledges its responsibility in the prevention of crimes against persons exercising their right to free speech (Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights, 2020[111]). Brazil’s Civil Rights Framework for the Internet, approved in 2014, also guarantees the right to freedom of expression as a pre-condition for the full enjoyment of the right to Internet access (Art. 8) (Government of Brazil, 2014[112]).

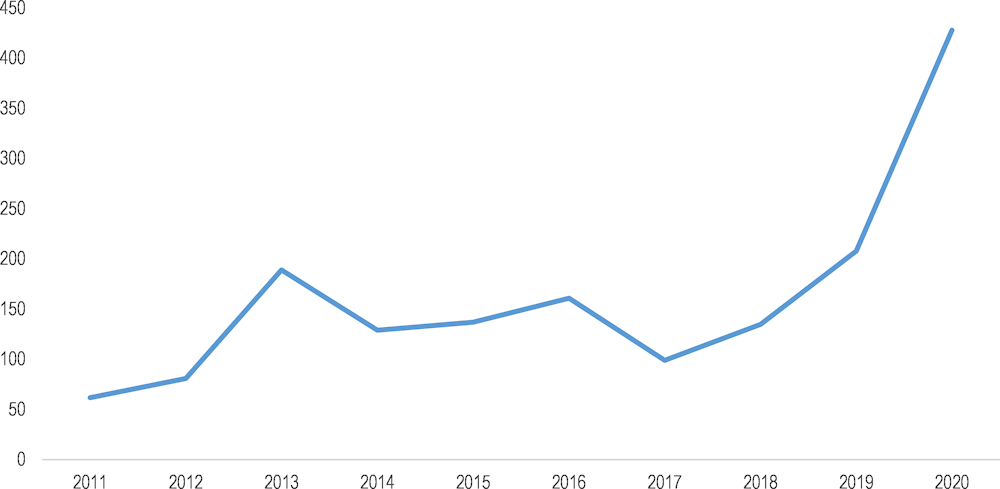

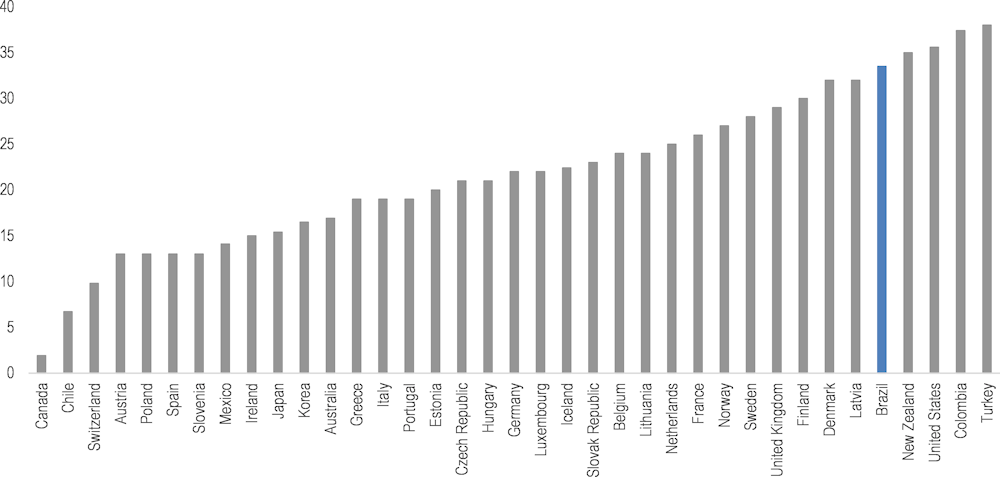

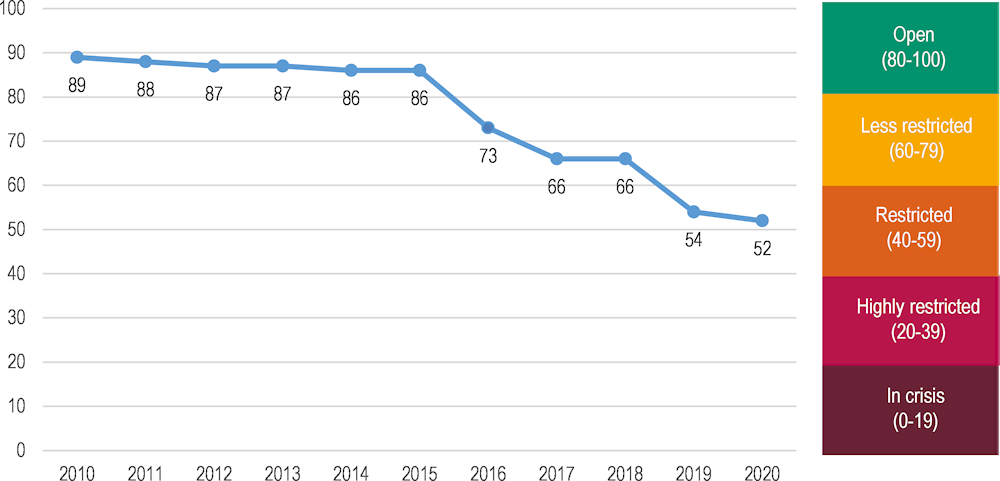

However, implementation of this fundamental right has suffered in recent years. Article19’s Global Expression Report 2021, which assesses the state of freedom of expression around the world, indicates that Brazil has fallen from an “open” to a “restricted” environment in the last ten years (Figure 5.1) (Article19, 2021[113]), against a background of the regional score for the Americas also being at its lowest for a decade. Brazil currently ranks 86th out of 161 countries assessed. As a point of reference, the top five countries in the region where freedom of expression is considered “open” are Uruguay, Canada, Costa Rica, Argentina and the Dominical Republic. The bottom 5 where freedom of expression is “in crisis” or “restricted” are Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Bolivia and Colombia. Brazil experienced the world’s biggest drop in score over one, five and ten years, a decline that has accelerated in the last couple of years. The COVID-19 pandemic consolidated this negative trend, which has also been affected by the rise in mis- and disinformation in Brazil (see Section 5.3.5).

Figure 5.1. Evolution of freedom of expression in Brazil, 2009-19

Notes: The Global Expression metric tracks freedom of expression across the world, assessing how free each and every person is to post on line, to march, to teach and to access the information to participate in society and hold those with power to account. Twenty-five indicators are used in 161 countries to create a freedom of expression score for every country on a scale of 1 to 100, placing countries into 1 of 5 categories: open, less restricted, restricted, highly restricted, in crisis.

Source: Article19 (2021[113]).

Interviewees consulted as part of this review confirmed deteriorating conditions regarding freedom of expression in Brazil, with a detrimental impact on civic space, public debate, and civic engagement more broadly. A significant body of research from think tanks, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and media outlets illustrates that journalists, members of CSOs, members of trade unions, communicators (e.g. bloggers, radio hosts), indigenous leaders, academics, artists, politicians, and public figures are all facing a restricted ability to air critical views24 (Article19, 2021[114]; Igarapé Institute, 2020[115]; Folha de São Paulo, 2020[116]; IACHR, 2021[19]). Article 19 has noted that 50% of the violations against journalists and communicators that it recorded in 2020 were committed by public agents and 18% were racist, sexist or biased against the LGBTI community (Article19, 2021[113]). Several cases have been reported of people being subjected to investigations and arrest,25 with allegations of defamation and contempt of authority (desacato) for criticising the government (Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, 2021[117]; Souza, 2021[118]; Igarape Institute, 2021[119]; Malheiro, 2021[120]). Other particularly serious cases that have been documented, 20 in total, involved killings, attempted killings and death threats, according to Article 19 (Article19, 2021[113]).

The environment for students and academics to freely express themselves and teach and learn has also been affected. Staff, teachers and students, especially of universities, have experienced censorship in the context of protests and debates. For example, in 2018, police officers entered public and private universities in several Brazilian states seizing materials and banning meetings and assemblies of a political nature (Fórum Nacional pela Democratização, 2017[121]). The rulings by electoral judges that had led police officers to do so were later suspended by the Supreme Federal Court (Supreme Federal Court, 2018[122]). According to the latest Academic Freedom report on Brazil from the Berlin-based Global Public Policy Institute and Center for the Analysis of Liberty and Authoritarianism, threats to academic expression also include significant budget cuts and freezes, judicial orders censoring political debates on campuses, and false statements about the academic community, among others (Hübner Mendes et al., 2020[123]).

Instances of artistic censorship have been observed, including the closure of artistic spaces and exhibitions (Moura, 2021[124]; Prisco, 2019[125]). Interference by authorities with plays, publications and works of art have also been widely reported in the last five years (Bergamo, 2021[126]; Angelo, 2020[127]; Fórum Nacional pela Democratização, 2017[121]). The main targets are often artists or works that express a political opinion, or those linked to identity or social agendas, such as the protection of women’s, LGBTI people’s and AfroBrazilian‑ rights and movements.26

Recommendations

As with freedom of peaceful assembly, the exercise of freedom of expression is a fundamental component of every democratic society. Freedom of expression strengthens open government by facilitating transparency, accountability and equal and effective citizen participation.

In line with the Constitution, Brazil is encouraged to commit to reversing negative trends in this area as a means of furthering basic democratic norms by facilitating an environment in which pluralistic public debate and freedom of expression are supported. A first step would be a public acknowledgement of negative trends from the highest levels of government, coupled with a series of commitments to reverse them.

As already noted by the Inter-American Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, public officials have a duty to ensure that their pronouncements and actions do not cause harm to those who contribute to public debate (Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, 2021[117]). Public officials are strongly encouraged to refrain from any measures that may limit or censor the expression of views, in accordance with the constitution, and should be held to account where violations occur. A code of conduct or manual, coupled with mandatory training, could help in this regard.

Protecting press freedom, journalists and the media

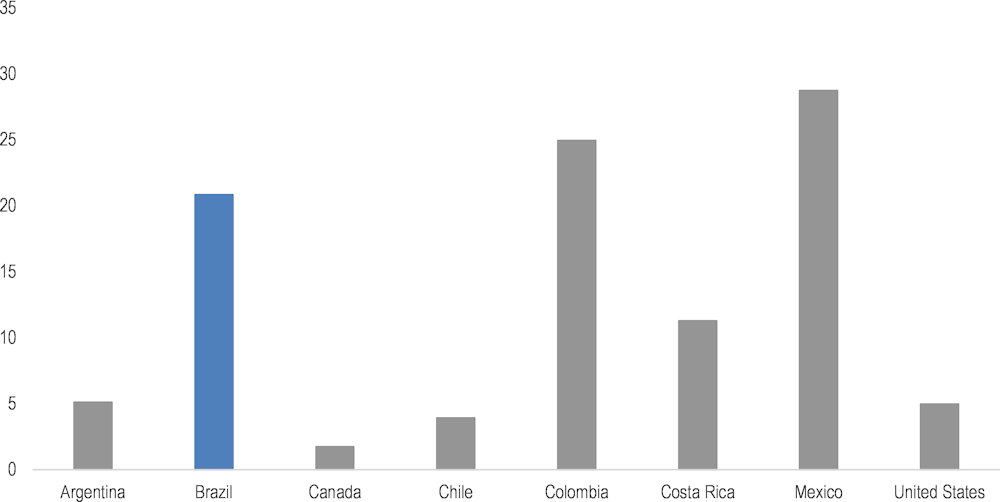

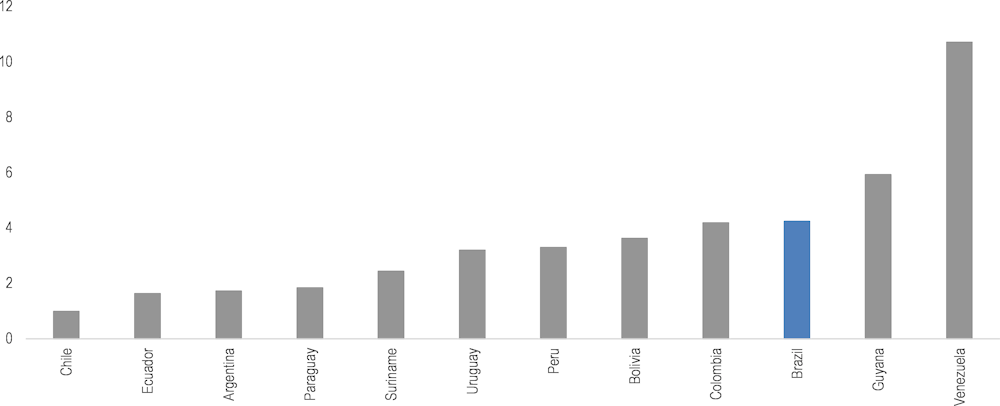

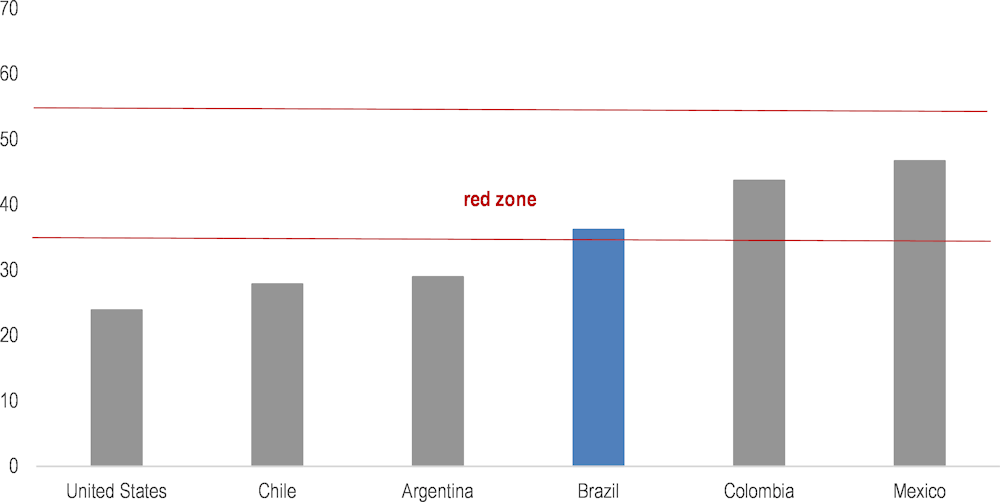

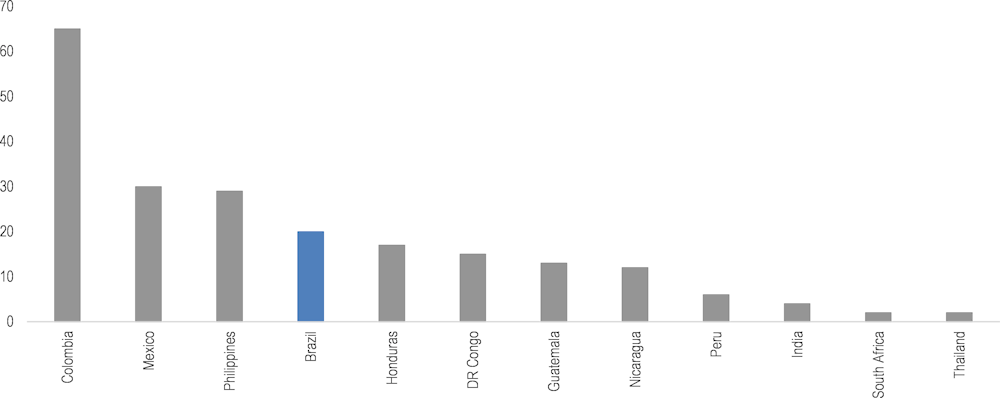

Journalists and communicators are particularly affected by obstacles to freedom of expression in Brazil. Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index for 2021 shows that that Brazil has entered the so-called “red zone” after four consecutive declines, indicating a deterioration of the press environment in the country (Reporters Without Borders, 2021[13]). It now ranks 111th out of 180 countries and territories assessed. As a comparison, the United States ranks 44th, Chile 54th, Argentina 69th, Colombia 134th and Mexico 143rd. Colombia and Mexico are also in the red zone (Figure 5.2). Brazilian expert respondents to the index’s survey reported that journalists practise selfcensorship‑ for fear of civil lawsuits, criminal prosecution, and professional reprisals or attacks on their reputation. They also view the protection of journalists’ sources as threatened by “political power”, “the military”, “judges and prosecutors”, and “organised crime”.27

Figure 5.2. World Press Freedom Index for Brazil and selected countries, 2021

Notes: Scores range from 0 to 100, with 0 being the best possible score and 100 the worst. Scores are based on qualitative and quantitative data on pluralism, media independence, media environment and self-censorship, legislative framework, transparency, the quality of the infrastructure that supports the production of news and information, and violence against journalists and media outlets (Reporters Without Borders, n.a.[128]).

Source: Reporters Without Borders (2021[13]).

The government acknowledges its responsibility in protecting journalists at risk because of their profession, and the investigation, prosecution and punishment of those responsible for crimes committed against them and other communicators in its booklet “Aristeu Guida da Silva” (Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights, 2020[111]). Several initiatives are foreseen in this regard. In a positive development, the Programme for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders (PPDDH) explicitly includes “communicators” since 2018 (now the Programme for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, Communicators and Environmentalists), defined as those performing “regular social communication activities, of professional or personal nature, even if unpaid, to disseminate information aimed at promoting and defending human rights and who, as a result of acting in this objective, are experiencing situations of threat or violence aimed at constraining or inhibiting their performance or work” (Ministry of Human Rights, 2018[129]). There are currently five communicators registered in the programme, located in the states of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais and Ceará.28

The government is also undertaking more targeted actions for the promotion and protection of communicators (Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights, 2019[130]). These include a 2018 campaign to promote the visibility and appreciation of communicators, a training session for PPDDH technicians to act and assist communicators delivered in co-operation with several CSOs, and a workshop to discuss violence against communication professionals and propose actions to reduce it organised in partnership with the National School of Public Administration.

The National Human Rights Council, also linked to the Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights, has a Permanent Commission on the Right to Communicate and to Freedom of Expression. This commission focuses on communicators such as members of community radios or authors of blogs, including those with no professional registration, who need protection to exercise their right to freedom of expression (Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights, 2020[111]). In 2020, the council organised several meetings to discuss challenges such as disinformation, hate speech, political violence on the Internet and attacks on journalists (National Human Rights Council, 2020[131]). It issued several recommendations, including one in 2019 advising public officials to follow international and national standards for freedom of expression, press freedom and the right to information (National Human Rights Council, 2019[132]). The same document reinforced the importance of a public discourse that contributes to the prevention of violence against communicators and to an environment favourable for the free exercise of journalism and freedom of expression. In 2020, the National Human Rights Council published a public note on the high rate of violence against journalists and communicators in Brazil, recognising an increasingly challenging environment for journalism in Brazil due to an increase in hostility (National Human Rights Council, 2020[133]).

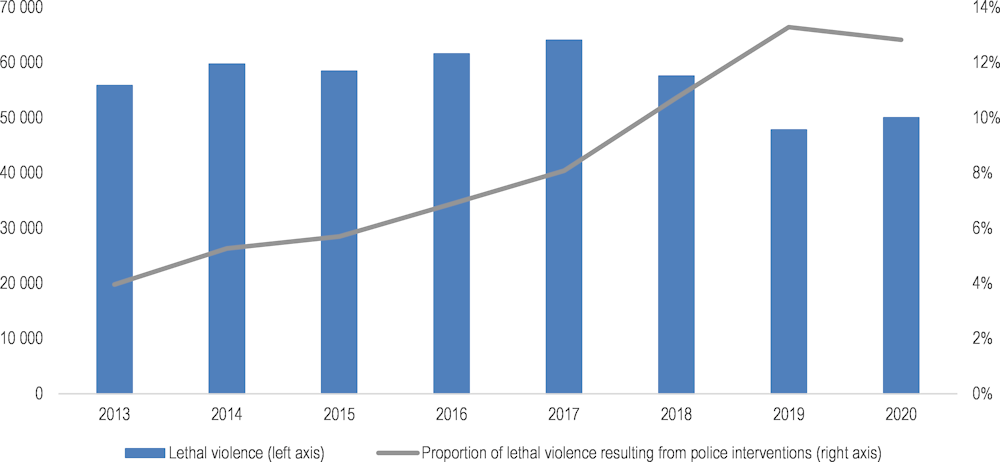

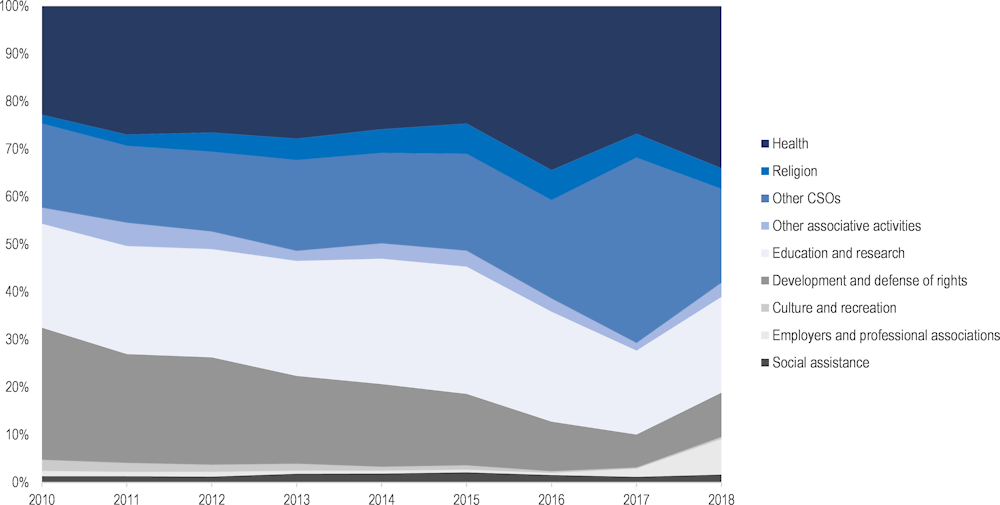

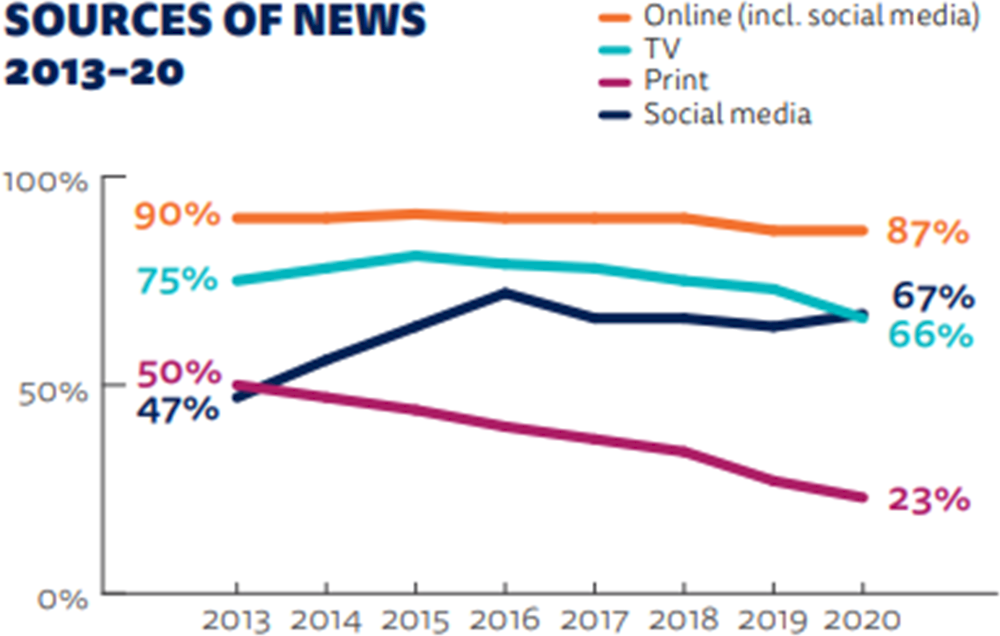

Despite these various efforts, violence against journalists is on the rise. The National Federation of Journalists considered 2020 to be the most violent year since the 1990s for Brazilian journalists, with 428 cases of reported violence – covering physical as well as other forms of violence – against media outlets and journalists (compared to 208 cases in 2019) (FENAJ, 2021[134]) (Figure 5.3). These cases included hate speech, intimidation and censorship, as well as physical aggression and homicide, with 2 journalists killed. By June 2021, two more journalists had been killed (Reporters Without Borders, 2021[135]). Article 19 noted in its 2021 Global Expression Report that journalists are being stigmatised and delegitimised (Article19, 2020[136]). An increase in criminal prosecutions of journalists, stigmatising language, targeted verbal aggression, attacks against journalists and their families using social media and instant messaging applications, physical attacks and threats including kidnapping, judicial actions, and censorship and requests for removal of content are all documented in the 2020 report from the Inter-American Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression (Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, 2021[117]).

The digital sphere is particularly affected: The Brazilian Association of Radio and Television Stations also recorded 7 945 virtual attacks per day on social media in 2020, or an average of almost 6 per minute, with negative posts and derogatory remarks about journalism, the media, journalists or the press on Twitter, Facebook and public Instagram accounts (ABERT, 2021[137]). In a survey conducted for this review, 21 out of 23 responding CSOs identified attacks against journalists and hate speech to be two of the main threats to civic space in Brazil today.

Figure 5.3. Episodes of violence against journalists in Brazil, 2011-20

Data indicate that such violence is frequently committed against journalists from small media outlets, radio broadcasters and bloggers (Article19, 2018[139]). As is common in many other countries, female journalists are also particularly targeted, and offenses against them often include gender-based hostility, comprising online sexual harassment and threats of sexual violence, insults hurled in the street, and lawsuits seeking moral damages over their reporting (ABRAJI, 2021[140]; Posetti et al., 2021[141]; Article19, 2020[136]; Reporters Without Borders, 2020[142]). In July 2020, a group of CSOs presented a complaint during a session of the United Nations Human Rights Council reporting that female journalists had been victims of hostile public declarations and virtual aggressions by government officials at least 54 times over an 18-month period (Terra de Direitos, 2020[143]; Chade, 2020[144]). An emblematic case was that of Patricia Campos Mello, who was accused of trading sexual favours for information leading to a series of online attacks against her involving disinformation and fake pornographic images, as well as rape threats (Posetti et al., 2021[141]). The cyberharassment‑ campaign was so violent that she was forced to hire a bodyguard. She sued and won two court cases for moral damage (Reporters Without Borders, 2021[145]; Neder, 2021[146]; Arcoverde, 2021[147]).

Brazil is also among the ten countries in the world with the highest rates of impunity for the killing of media workers, according to the Committee for the Protection of Journalists (CPJ, 2019[148]). This high rate of impunity is recognised by the National Council of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, which has collected official information on all homicides committed against journalists, press professionals and communicators in the exercise of their profession since 1995 in Brazil (National Council of the Public Prosecutor's Office, 2019[149]). Of the 64 cases of homicides analysed, 32 were duly resolved, 2 were partially resolved, 7 were not resolved, 16 were still under police investigation and for 7 cases it was not possible to obtain information. The report acknowledges that many of the masterminds behind crimes against journalists and communication professionals are not held accountable in Brazil.

Recommendations

Acknowledging the challenges described above, it is crucial for Brazil to continue to strengthen existing efforts to protect journalists, in line with measures already identified by the government in its “Aristeu Guida da Silva” (Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights, 2020[111]), and in consultation with journalists and communicators to address their needs. As part of related efforts, Brazil could:

More effectively promote the PPDDH among journalists and communicators and offer protective measures to all those at risk during the exercise of their profession.

Investigate, prosecute and hold to account those responsible for violence against journalists and other communicators in a timely and effective manner.

Implement other preventive measures such as public communication and information campaigns about the crucial role of journalism in society, and undertake specific and regular training of public officials, and training of police and law enforcement officials. A code of conduct or manual for public officials and sanctions for non-compliance could help in this regard.

Ensure timely and equal access to information and data, including as open data, for journalists and communicators to facilitate their crucial work as intermediaries between citizens and the state, as watchdogs, and as promoters of transparency and accountability (see Chapters 6 and 9).

Media concentration and the risk of political interference

A free and pluralistic media has a direct impact on civic space – and by extension on transparency, accountability and public participation – as it allows diverse opinions and sources of information to circulate and inform national debates and decision making. Media concentration, on the contrary, can hamper balanced and multifaceted conversations and promote one-sided views, thereby igniting polarisation and societal conflicts. Studies observe an association between free press and democracy (Norris, 2008[150]) and between a greater penetration of newspapers, radio and TV and less corruption (Bandyopadhyay, 2009[151]). Countries where much of the public has access to the free press have also been found to have greater political stability and rule of law (Norris, 2008[150]).

With 96% of Brazilian households owning a television (IBGE, 2019[152]), free-to-air (FTA) broadcasting is the medium that reaches the most people and across the greatest distance in Brazil. According to the OECD Telecommunication and Broadcasting Review of Brazil (OECD, 2020[28]), Brazil had 862 nationwide commercial FTA TV channels, 131 nationwide public TV channels (generating own content), 20 874 regional commercial TV channels and 75 regional public TV channels in 2018. Despite the high number of TV channels in the country, audience share is highly concentrated. The three most‑watched channels – Globo, SBT and Record – had a 63% audience share in November 2019. The review also notes that public and government broadcasting are not explicitly differentiated in Brazil, neither by law nor in practice. It observes that the seven public FTA channels29 with significant national coverage in Brazil are all owned by government entities and that the main one is under resourced.

The four major newspapers (Globo, Folha, RBS and Sada) and Internet media (Globo, Folha, Record and IG) also have an audience share above 50%, which indicates a high audience concentration (Reporters Without Borders and Intervozes, 2017[153]). Ownership concentration is also high across different sectors of the media industry: TV, print, audio and other media. Grupo Globo, for example, owns key channels in FTA TV (with Rede Globo as the audience leader), cable TV (with content generated by the subsidiary GloboSat, including GloboNews and other channels), Internet (with the largest Brazilian news portal, Globo.com), radio (with Globo AM/FM and CBN among the ten largest audiences), and recording and publishing markets.

The News Atlas, a mapping of journalistic outlets in Brazil, found that there were no local press vehicles in close to 60% of Brazilian municipalities in 2021, meaning that around 34 million Brazilians do not have access to any journalistic information about the place where they live (Observatório da Imprensa, 2021[154]). The situation is worse in the Northeast and North regions, where 66.3% and 69.8% respectively of municipalities had no registered outlet, creating deserts of news. The News Atlas identified 1 170 new digital vehicles which have now become the second largest category in Brazil, behind radio. The print media saw the closure of 200 channels in 2020.

According to Reporters Without Borders and Intervozes (2017[153]), Brazil also presents a medium to high risk of political affiliation and control over media networks and distribution. The authors also warn of a lack of transparency towards the audience, journalists and regulators in terms of who has control over each media outlet and what their interests are. Although the state controls less popular channels, there is also potential for political influence on commercial mainstream media due to conflicts of interest. Some media groups have a public official among their shareholders, while others have family members who are elected politicians, for example (Financial Times, 2018[155]; Fonseca Figueiredo, 2011[156]). Political interference is also a risk through the selective or discriminatory allocation of funds for state publicity, something that has been observed in the country by international organisations, CSOs and the media itself (Organization of American States, n.a.[157]; Reporters Without Borders and Intervozes, 2017[153]). Media professionals, lawyers and sociologists consulted by Reporters Without Borders for the World Press Freedom Index consider the extent of official interference in appointments to director of the TV and radio regulatory agency in Brazil to be at a maximum and find that government advertising is not distributed equitably across different media.30

Recommendations

Fostering media pluralism and autonomy could have a positive impact on civic space and citizen participation more broadly by creating an environment in which informed public debate can flourish. Some of the recommendations proposed in the OECD Telecommunication and Broadcasting Review of Brazil (OECD, 2020[28]) are particularly relevant for civic space, as they promote press freedom, freedom of expression, transparency and citizen’s capacity for more effective participation. These include the need to:

strengthen the national public broadcasting system by ensuring sufficient funding and the editorial independence of public broadcasters.

foster media pluralism and the diversity of regional and local content, including promoting local and community broadcasters and press vehicles.

ensure that the media and regulatory agencies can operate freely from political influence and that funding for state publicity is allocated equitably and transparently across media channels.

Protecting privacy, and ensuring data protection and cybersecurity

Privacy and data protection are core components of civic space as they help to create the conditions for citizens to inform and express themselves freely, in addition to debating ideas. Surveillance by governments can be used for legitimate national security and other purposes such as crime prevention. But it can also violate peoples’ right to privacy, in addition to acting as an obstacle to their ability to freely express themselves, communicate, organise and associate on an equal basis, if misused or applied in an invasive or arbitrary manner. Privacy and data protection thus support the other fundamental components of protected civic space, including in the digital sphere, such as freedoms of expression, assembly, association, press freedom and autonomy, equal participation in public debate and decision making, and the enabling environment for CSOs (see Section 5.4).