Public trust varies significantly across different institutions. The OECD Trust Survey asks respondents to indicate their level of trust in the national government, local government, civil service, the judiciary and legal system, political parties, parliaments and congresses, the media, intergovernmental organisations, and other people. This chapter presents cross-national levels of trust across these institutions and explores the degree to which different institutional traits – like reliability, responsiveness, integrity, openness and fairness – significantly correlate with levels of trust in OECD countries.

Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy

2. How trustworthy is your government?

Abstract

Key findings and areas for attention

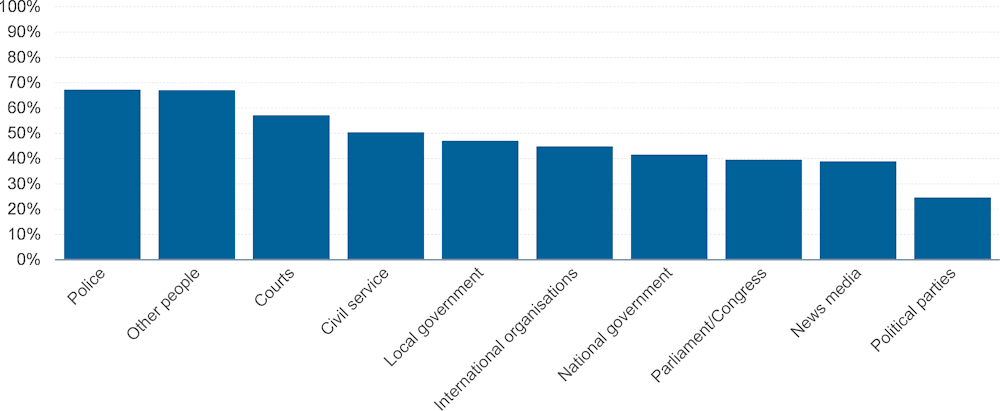

The OECD Trust Survey asks respondents a series of straightforward questions exploring how much they trust different institutions of government. In response to these questions, only four out of ten people say that they trust their national government, on average across OECD countries. Local governments and civil servants fare slightly better: nearly half of respondents, cross-nationally, say they trust their local government, and a similar share trust civil servants. A majority of respondents trust the courts and the police in their country, while support is relatively low for political parties, legislative institutions like parliament and congress, and the media.

Several measures of government reliability (e.g. future pandemic preparedness), perceptions of having a say in what the government does, government openness in accounting for views from a public consultation, and confidence in the government’s capacity to enact future-oriented reforms have the most statistically significant relationships with trust in national government.

Perceptions of government reliability, fairness and responsiveness have a statistically significant relationship with trust in the civil service. Satisfaction with administrative services, perception of fairness by public employees in treating different people or applications for public benefit, confidence in the government’s use of data for legitimate purposes, feelings of having a say in what the government does, and responsiveness of government agencies to adopt innovative ideas have the most statistically significant relationships with trust in the civil service.

Perceptions of government openness, reliability and responsiveness is strongly related to trust in local government. People’s perceptions that they can voice views on local government decisions and have a say in what the government does, together with satisfaction with administrative services, perception of government preparedness for future crises and responsiveness of public agencies to adopt innovative ideas are the variables with the strongest statistical relationships with trust in the local government.

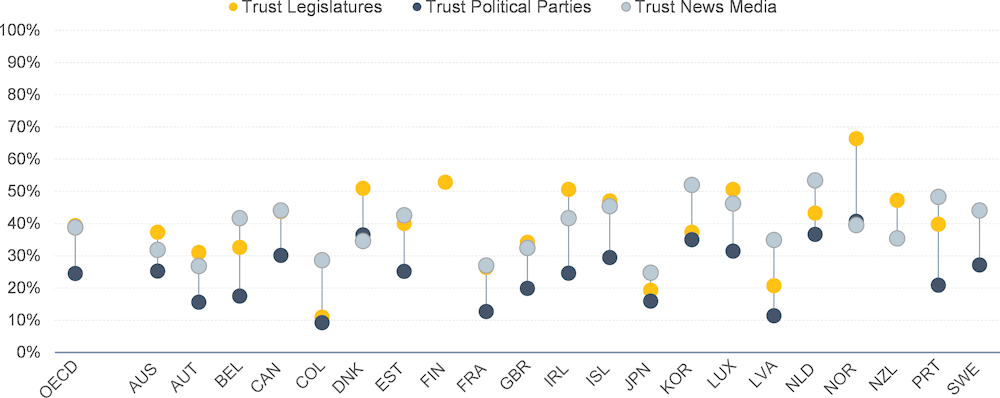

What do people in OECD countries say when asked how much they trust different government institutions? Different institutions and actors elicit different responses. On average across countries, people tend to have high trust in other people. When thinking about government specifically, respondents on average trust their local government more than they trust their national government, and they trust civil servants most of all. Respondents also have fairly high levels of trust in institutions of justice, like the police, courts and the legal system. In contrast, representative legislative institutions, the media and political parties tend to fare the worst – across countries, respondents are most sceptical of these institutions (Figure 2.1).

It is worth noting that awareness of different levels and Ministries in government, as well as their differing responsibilities, can also vary enormously across countries. For this (and other) reasons, Trust Survey questions were adapted to fit local contexts and needs in participating countries, and should be continuously evaluated for cross-national comparability (Box 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Trust in other people and the police is relatively high, while political parties are viewed with scepticism

Note: Figure presents the OECD average of share of countries who reported they trust a given group or institution. Respondents were asked, “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust [insert name of institution]?” In this report, results 0-4 are grouped as not trusting; a result equal to 5 is considered neutral; and results 6-10 are grouped as trusting. Respondents could also choose the answer choice “Don’t know.” For more detailed information please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

Box 2.1. Improving the OECD Trust Survey to adapt to different national contexts

The OECD Trust Survey attempts to harmonise the measurement of trust in government institutions across OECD countries. This implies making the questions and therefore results as comparable as possible. A detailed methodological document, which includes an overview of the national samples, survey methods and a table presenting the different questions asked in different countries, and identifies challenges in the interpretation of results in a cross-country setting, is available at http://oe.cd/trust.

The very nature of a cross-national survey implies trade-offs between country-specific and cross-nationally comparable information. Specific questions in one country may not be relevant in other countries, which complicates comparability. For example, the OECD’s general Likert-scale question on “trust in the judiciary and the legal system” is in line with the grouping of these institutions in other cross-national surveys (for instance, the Gallup World Poll asks for a yes/no response to questions about “confidence in the judicial system and courts”), but it may be more relevant to further disaggregate these institutions in future iterations of the Trust Survey. The prosecution, the courts, the executive-level Ministry of Justice and other aspects of the legal system could be evaluated independently in survey questions. The results in Korea illustrate the possible benefit of better clarifying these institutions: while Korea’s result for trust in the judiciary and the legal system (grouping) is in the lower half of the OECD’s cross-national results, Korea performs well in the more focused question on perceptions of the political independence of the judiciary. Other institutions of government may merit a closer look, as well, such as tax agencies or national statistical offices, which play an important role as providers of information in a context where information sources are not always trusted (Chapter 6).

There is also likely some systematic, country-specific bias in responses even if careful steps are taken to prepare question wording and response choices. For example, the OECD Trust Survey uses a best practice 11-point scale for most questions in this survey (see Box 4.1 in Chapter 4). Yet survey-based research suggests, for example, a greater propensity for a “middle response” to Likert scale-type questions in Asian countries and a higher propensity for responses on more extreme ends of the scale in Latin American countries (Moss and Vijayendra, 2018[1]; Yoshino, 2015[2]). This aligns with some of the results in the OECD Trust Survey in, for example, Japan, where a relatively high share of respondents tend to report a mid-range (neutral) response or a “Do not know” response (see Figure 1.2 in Chapter 1). This seems to be of particular concern on the questions asking generally about trust in different institutions – perhaps related to the confounding factors point in the previous paragraph about trust in the judiciary. In a very few questions, the shares of “don’t know” respondents are higher than the average also in Denmark, France and Sweden.

The 2021 Trust Survey was the inaugural survey wave, and the OECD is committed to continuously improving the survey questionnaire and analysis to improve cross-national comparability while also recognizing unique cultural, institutional, and socioeconomic contexts in different countries. Some areas worth investigating further in country-specific and cross-national research include: country-specific propensities to select “middle” or “neutral” categories or a “Don’t know” responses; carrying out cognitive tests to assess clarity and interpretability of some questions in different cultural contexts; and testing alternative methods to increase accuracy of responses in certain population groups generally less represented in sample surveys.

A few national adaptations

In some cases, countries suggested an adaptation of the question wording in advance of the survey to fit better their national institutional and cultural contexts or to collect additional insights.

For example, in Mexico, as in many other federal countries, the configuration of different levels of government is complex. The three levels of government - federal government, state and municipal are each charged with some degree of public goods provision in some cases overlapping. It is therefore often difficult for respondents to know exactly which level of government, or which Ministry, delivers which services or programme. Asking people about “government” therefore, risks misinterpretation. Thus the Mexican National Statistical Office (INEGI) asked respondents about their level of trust in the President and Governors of states. While the trust estimates for the President match the results of national opinion polls collected around the same time, for the purposes of cross-national harmonisation, there is a risk that an individual person is mistaken for the institution of the executive. For this reason, estimates for “trust in the civil service” is sometimes used in lieu of “trust in the national government” for Mexico in this report.

Mexico’s INEGI administered the new Trust Survey questions in collaboration with the administration of their regular, ongoing national survey on the quality and impact of government services and procedures at different levels of government, the Encuesta Nacional de Calidad e Impacto Gubernamental (ENCIG). ENCIG looks more closely at the specific outcomes for different actors, institutions and levels of government. This may be a fruitful approach for future iterations of the OECD Trust Survey.

Similarly, New Zealand excluded some questions that would have violated guidance on political neutrality of public agencies issued by the Public Service Commission. Specifically, the questions on “trust in national government” and “trust in political parties” were not asked. Questions on policy priorities, government use of data, perceived integrity of elected officials, and change of policies to public feedback were also excluded from the questionnaire in New Zealand.

Other countries sought to address additional topics or gathered information on diverse groups. Ireland, for example, included additional questions on interpersonal trust and social capital based on hypothetical situations involving a lost wallet. The United Kingdom asked about satisfaction with specific public services, while Portugal included exploratory questions to assess the perceived importance of science and citizen engagement in the policy‑making process. New Zealand asked background questions on ethnicity as a demographic variable. The results of these country-specific investigations are being evaluated in OECD case studies or by national statistical offices.

2.1. The civil service and local governments are viewed as more trustworthy than national governments

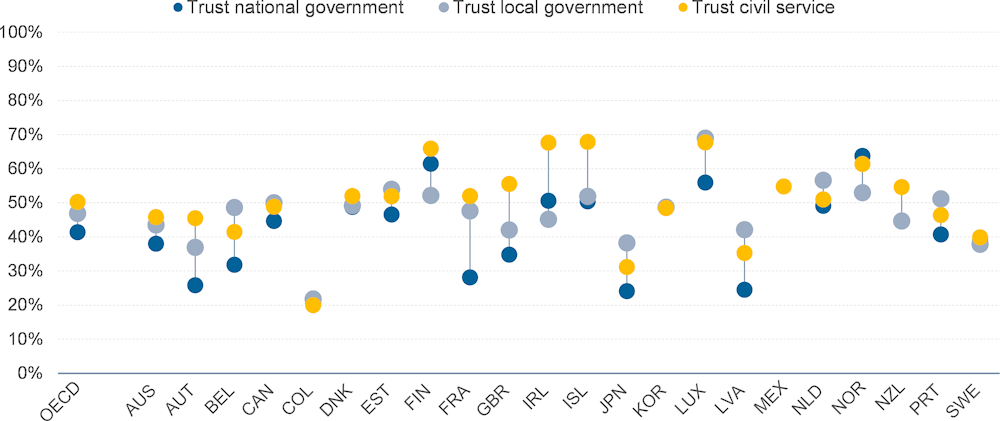

When asked about their degrees of trust in different levels of government, only about four in ten respondents (41.4%) trust their national government, on average across OECD countries, with rates over 50% in Norway,1 Finland, Luxembourg, Ireland and Iceland. 14.8% hold a “neutral” position when evaluating whether they trust their government, and 41.1% tend not to trust their government (Chapter 1).

Local governments tend to inspire more confidence. On average across countries, 46.9% of people say they trust their local government and only 32.4% say they do not trust their local government. Civil servants fare better than the more general local and national governments: half (50.2%) of respondents, on average, say that they trust civil servants in their country. Importantly, fewer than one-third of respondents say that they do not trust civil servants.

However, differences in trust across institutions can also vary widely within countries. For example, 67.6% of respondents in Ireland trust the civil service, while only 50.6% the national government and fewer than half trust the local governments (Figure 2.2). The gap is similar in France.

It should be noted that Japan has high shares of respondents who either feel neutrally about trust in government and civil service or selected “Don’t know,” which is not associated with a number value on the scale. Taken together, a solid majority of respondents in Japan either trust, hold a neutral view, or report they are unsure whether they trust the national government, the local government and civil service. This may suggest an important flexibility in terms of trust in government in Japan and the interpretation of these responses should be explored further (Box 2.1).

Figure 2.2. People generally trust their civil service and local government more than their national government

Note: Figure presents the share of response values 6-10 in three separate questions: “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the [national government / local government / civil service]?” For New Zealand, data for trust in national government are not available; for Mexico data on trust in national and local government are not available. For more detailed information please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

The fact that the civil service is viewed as more trustworthy than the more abstract concepts of “national government” and “local government” may be cause for cautious optimism. Civil servants are, in many ways, the human face of government institutions; they work directly and professionally with citizens and users of government services (OECD, 2021[3]). Civil servants are important representatives of government processes and programmes and can be particularly effective and well-perceived when they are autonomous from political influence (Dahlström and Lapuente, 2021[4]). This relatively higher satisfaction with civil servants also aligns with relatively positive perceptions of government reliability (Chapter 4).

Even in countries where trust in the national government was low in cross-national comparison in November 2021, such as Austria – perhaps reflecting the start of the fifth wave of COVID-19 in that country – trust in the civil service remained higher. This suggests some longstanding, structural, underlying confidence in public sector workers.

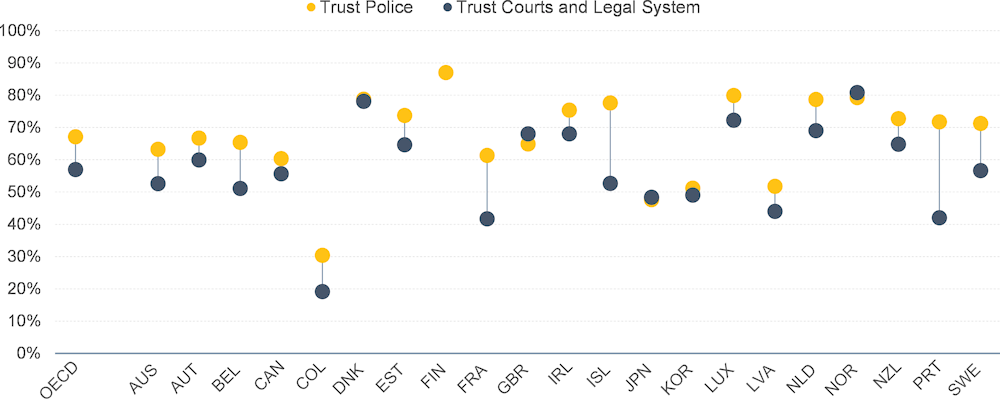

2.2. The police and the courts fare better than elected officials

Public institutions tasked with security and justice also tend to be viewed positively. Over two-thirds (67.1%) of respondents, on average across countries, say that they trust the police. Just over half – 56.9%, on average – trust the courts and legal system (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3. Public trust in the police, courts and legal system is generally high

Note: Figure presents the share of response values 6-10 in three separate questions: “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the [police / courts and the legal system]?” Mexico is excluded from this figure as the data for trust in police and courts and legal system are not available. For Finland, data on trust in courts and legal system are not available. For more detailed information, please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

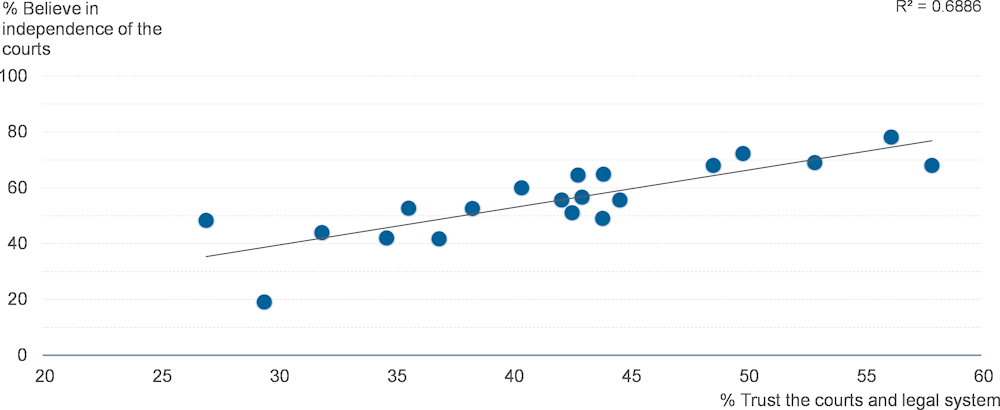

This result roughly aligns with the share of respondents on average who think that courts make decisions free of political influence plus the share who hold a “neutral” view of courts’ independence (Chapter 5). The perceived independence of the courts is positively correlated cross-nationally with public trust in courts and the legal system (Figure 2.4).

It should be noted that the question on “trust in the judiciary and the legal system” may elicit different responses across countries depending on the national organisation of the various functions, and it may be more relevant to further disaggregate these institutions in future iterations of the Trust Survey. The results in Korea, for example, illustrate the possible benefit of better clarifying these institutions: while Korea’s result for trust in the judiciary and the legal system (grouping) is in the lower half of the OECD’s cross-national results, Korea performs well, and above the OECD average, in the more focused question on perceptions of the political independence of the judiciary.

Figure 2.4. Trust in the courts and legal system is positively associated with perceptions of independence of the courts

Note: This scatterplot presents the share of “trust” responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the courts and legal system?” on the x-axis. The y-axis presents the share of “likely” responses to the question “If a court were about to make a decision that could negatively impact the government’s image, how likely or unlikely do you think it is that the court would make the decision free from political influence?” Finland, Mexico and Norway are excluded as the data on judicial independence are not available. For more detailed information, please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

Across countries, one group consistently elicits strong feelings of low trust: political parties. On average only 24.5% of respondents trust political parties, while 55.5% do not trust political parties. Respondents also have relatively weak levels of trust in representative legislative institutions – parliaments and congresses. Only 39.4% of respondents, on average across countries, report trusting their country’s legislative institution. In Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Norway and Luxembourg a small majority do trust their parliament. Indeed, in Norway trust is higher in the parliament than it is in the national government, local government and civil servants.

These results fit into a broader pattern of feelings of disempowerment. Respondents have relatively low levels of confidence in the integrity of elected officials and high shares of people feel their voices are not incorporated in government policy making (Chapter 6). Trust in the national legislature is also strongly influenced by political preferences; while even people who voted for the parties in power do not inherently trust their parliament or congress, people who hold opposing political views exhibit considerably lower levels of trust in their national legislature and in government in general (Chapter 3).

Other institutions do not fare much better in perceptions of trust. Only 38.8% of respondents, on average, say they trust the news media.

Figure 2.5. Trust in political parties, national legislatures and the media is low throughout the OECD

Note: Figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to two separate questions: “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust [Parliament or Congress (varied by country) / political parties]?” The “trust” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “Do not trust” is the aggregation of responses from 1-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. Mexico is excluded from the figure as data are not available; for Finland and New Zealand, data on trust in political parties are not available. For more detailed information please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

2.3. In most countries, respondents are more confident in their government’s reliability than its responsiveness

These levels of trust in different institutions are driven by governments’ performance in different aspects of governance. The OECD Trust Framework sets out measurable guidelines to estimate where governments are viewed as performing well and where they may be falling short – with direct implications for trust (Chapter 1, Box 1.2).

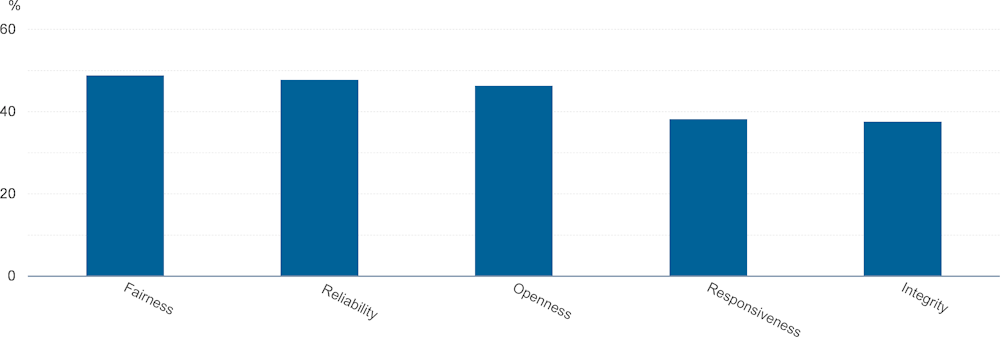

In nearly every country, respondents are more confident in their government’s reliability than its responsiveness. On average across countries, 47.7% of respondents consider their government reliable and 38.2% say their government is responsive (Figure 2.6). A majority of respondents in half of the surveyed countries (Luxembourg, Denmark, Ireland, Korea, New Zealand, Norway, the Netherlands, Estonia, Iceland, Canada and the United Kingdom) consider their government reliable, as measured by questions on future pandemic preparedness, government use of personal data, and the stability of business conditions. In contrast, in only one country – Korea – do a majority consider their government to be responsive, i.e. responding well to public feedback about policies and services and adopting innovative ideas to improve public services. Estimates of reliability and responsiveness also tend to have a statistically significant relationship with trust in regression analyses, as well (Section 2.4).

Figure 2.6. Governments fare better on measures of reliability than on responsiveness

Note: Figure presents the OECD average of “likely” responses across questions related to “reliability”, “responsiveness”, “integrity”, “openness”, and “fairness” (see OECD Trust Framework in Chapter 1). For more detailed information please find the survey method document at OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust).

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

An analysis of government values – also defined in the Framework (Chapter 1) – tells a more complicated story. Governments fare best on respondents’ feeling that their own application for a government benefit or service would be treated fairly, one of the dimensions of fairness in the OECD Trust Framework. In general, respondents are sceptical that government “openness” includes real opportunities to engage in the policy‑making process – but most feel that they can find information about administrative procedures fairly easily. On average, across countries, 46.2% of respondents consider their government “open”. Perceptions of government integrity are also relatively poor, as evidenced by the average values across questions about petty bribery, revolving doors arrangements for elected and appointed officials, and the political independence of the courts. Only 37.6% of respondents, on average across countries, are confident in the integrity of their government (Figure 2.6).

Interestingly, differences – or the range of results – across countries are relatively low for questions where governments on average scored poorly, such as changing unpopular policies in response to public opinion, using the results of a public consultation, and perception of the likelihood that a high-level political official would refuse a private sector job offer in exchange for a political favour. This means that there is relatively broad agreement, cross-nationally, that governments are not doing well in these areas. In contrast, there is more variation across countries on the questions where governments tended to fare better, on average – on the availability of information on administrative procedures, the legitimate use of personal data, preparedness for a new serious contagious disease, and the fair treatment of applications for public benefits.

Simply put, there is much more agreement among respondents on areas in which governments need to improve, while opinions are more divided on higher-performance areas. This suggests, possibly, a common agenda for OECD countries to address those areas where perception of government performance is widespread low, and benchmark policies and results among countries to continue improve those areas where perceptions are more varied.

2.4. Digging deeper: Exploring possible causal relationships between institutions and trust

Most of the figures in this report present descriptive indicators of public perceptions of different institutions and trust in government. The Trust Survey data are a useful tool for understanding, for example, what share of a national population has confidence in different institutions, services and processes – and for understanding characteristics and perceptions of people who trust (or do not trust) government. This descriptive evidence helps to give a global understanding of the relationship between institutions and trust.

Understanding the causal relationship between institutions and trust – in other words, how public governance causally affects trust – is a much more complicated task, especially with observational data. Even with the most sophisticated econometrics, the causal relationship between institutions and trust likely moves in two directions. Effective institutions and policies drive trust in government, and trust in government can make institutions and policies more effective. There is also collinearity and interactive effects across different aspects of governance that make it difficult to establish the causal effect of one particular variable. For example, the Trust Survey finds that respondents distrust politicians and are also sceptical of their ability to use their political voice; it is likely that these kinds of variables have an interactive relationship and jointly affect trust.

With these caveats in mind, a simple logit regression analysis of the Trust Survey data presents some evidence of the statistically significant relationship between different institutions and trust in the national government, local government and civil service. Using the pooled cross-national Trust Survey dataset and country fixed effects, we find that different factors are associated with trust in the national government, the civil service or the local government (Box 2.2).

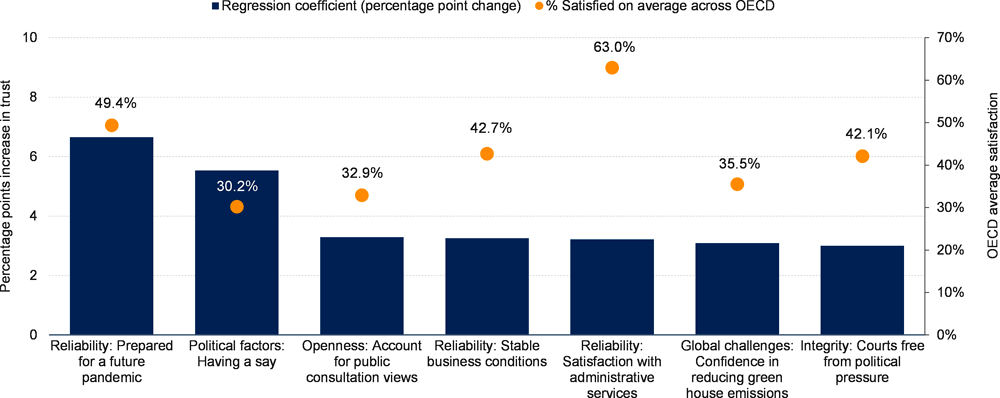

2.4.1. Selection of factors most significantly related to trust in national government

Most of the questions in the Trust Survey can be categorised into the different public governance components of the OECD Trust Framework: reliability, responsiveness, integrity, fairness and openness. Within these, the results on reliability seem to matter most in supporting trust in government.

The use of a regression in the Trust Survey microdata helps us understand the strength and nature (e.g. positive, negative) of the relationship between the dependent variable – trust – and a series of independent variables from the Trust Framework (Box 2.2).

When analysed in a logit regression, all survey questions on reliability have a significant and positive relationship with trust in the national government. For example, holding all other conditions equal, moving from the typical citizen to one with a slightly higher level of confidence in the preparedness to future disease2 is associated with an increase of 6.7 percentage points in the level of trust in the national government. This coefficient, in percentage points, is represented by the blue bar in Figure 2.7 (scale on left y-axis). An increase in people’s confidence on two other “reliability” questions is associated with an increase of around 3 percentage points in trust in the national government (Figure 2.7).

Political drivers, such as the perception of having a say in what the government does, government openness in accounting for views from a public consultation, confidence in the capacity of government to support reforms for the future, and perception of independence of courts, are the other variables with the strongest statistical relationship with trust in the national government.

While these results show how important these factors are vis-à-vis promoting trust, governments face different starting points in how satisfied people are with these different governance factors now. Only 30.2% of respondents, on average cross-nationally, say they feel they have a say in what the government does (right axis in Figure 2.7) – yet this is a fairly important variable related to trust in the national government, as indicated by its relationship with a 5.5 percentage point increase in trust.

Figure 2.7. Reliability and feelings of political voice are significantly related to trust in national government

Note: The figure shows the most robust determinants of self-reported trust in national government in a logistic estimation that controls for individual characteristics, self-reported levels of interpersonal trust, and country fixed effects. The model includes 18 countries; Finland, Mexico, New Zealand and the United Kingdom are not included, mainly due to missing variables. All variables depicted are statistically significant at 99%. Only questions derived from the OECD Trust Framework (Chapter 1) are depicted on the x-axis, while individual characteristics such as age, gender, education, political orientation, which also may be statistically significant, are not shown.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

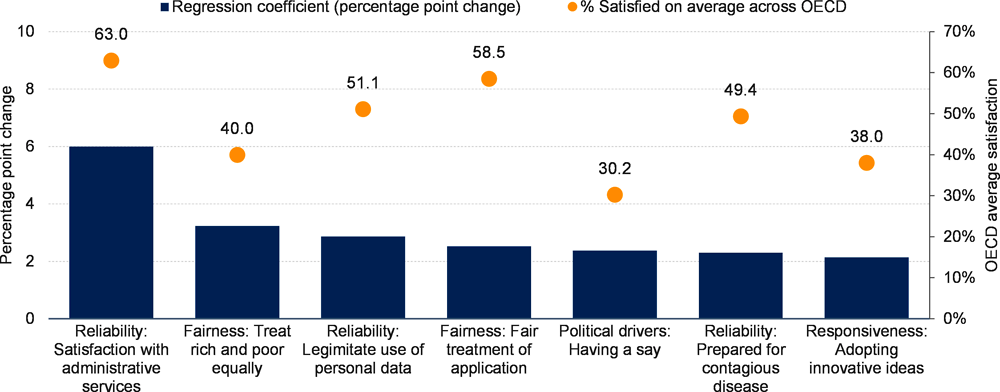

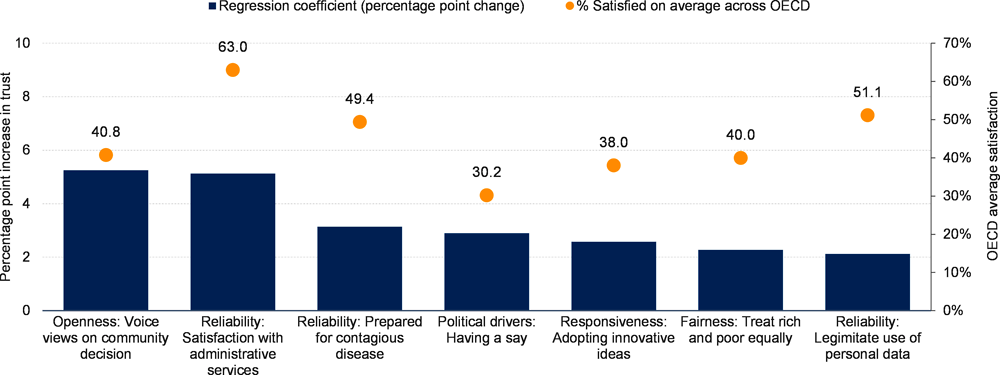

2.4.2. Selection of factors most significantly related to trust in the civil service

Reliability, fairness and responsiveness have the strongest statistically significant relationship with trust in the civil service. Holding all else constant, moving from the typical citizen to one slightly more satisfied with administrative services is associated with an increase of 6 percentage points in the level of trust in the civil service (Figure 2.8, measured by blue bar related to left y-axis). The perception that rich and poor people are treated fairly in applications for public benefits, confidence that the government uses data for legitimate purposes, and confidence in government preparedness for a contagious disease are the other variables most strongly related to trust in the civil service (Figure 2.8).

At the same time, the cross-national average level of satisfaction with the variables shown in yellow vary quite a bit (Figure 2.8). Average values vary from 30.2% of people (cross-nationally) reporting that they can have a say in what the government does to 63% satisfied with administrative services (Figure 2.8, illustrated with the yellow dot related to the right axis). In other words, the starting point in people assessments of government varies across policy dimensions – some policy areas may have a positive and statistically significant relationship with trust, and already benefit from high level of satisfaction (e.g. satisfaction with administrative services). Others are areas that need more improvement.

Figure 2.8. Reliability and fairness have a significant relationship with trust in the civil service

Note: The figure shows the most robust determinants of self-reported trust in civil service in a logistic estimation that controls for individual characteristics, self-reported levels of interpersonal trust, and country fixed effects. The model includes 18 countries; Finland, Mexico, New Zealand and the United Kingdom are not included, mainly due to missing variables. All variables depicted are statistically significant at 99%. Only questions derived from the OECD Trust Framework (Chapter 1) are depicted on the x-axis, while individual characteristics such as age, gender, education, political orientation which also may be statistically significant are not shown.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

2.4.3. Selection of factors most significantly related to trust in local government

What influences trust at the local government level? People’s views of government openness and reliability have a statistically significant relationship with trust in the local government. Holding all else constant, moving from the typical citizen to one slightly more confident3 about voicing views on local government decisions or slightly more satisfied with administrative services is associated with an increase of five percentage points in the level of trust in the local government, respectively (Figure 2.9, blue bars associated with the left Y-axis). The other survey questions on reliability (preparedness for future disease, and legitimate use of private data), together with feelings of having a say in what the government does, perceptions that public agencies adopt innovative ideas, and perceptions of equal treatment by public officials, are the other variables with the strongest relationships with trust in local government. At the same time, the starting point in people’s assessment of government varies across policy areas. While a majority of respondents, on average across OECD countries, are satisfied with administrative services (63%) and the use of personal data (51%), only 41% of respondents feel they would be able to voice their views and 30.2% to have a say in what the government does (Figure 2.9 yellow dots, right axis).

Figure 2.9. Openness and reliability are significantly associated with trust in local government

Note: The figure shows the most robust determinants of self-reported trust in local government in a logistic estimation that controls for individual characteristics, self-reported levels of interpersonal trust, and country fixed effects. The model includes 18 countries; Finland, Mexico, New Zealand and the United Kingdom are not included, mainly due to missing variables. All variables depicted are statistically significant at 99%. Only questions derived from the OECD Framework (Chapter 1) are depicted on the x-axis, while individual characteristics such as age, gender, education, political orientation which also may be statistically significant are not shown.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

These results provide a first exploration of the main factors associated with trust in national government, local government and civil service and show that, on average across countries, these factors vary across institutions. Analysis for specific countries would highlight significant difference within this aggregate picture.

Box 2.2. Logit regression assessing the significance of different factors related to trust

The regression results in Section 2.4 present the statistical significance of the relationship between trust in national and local government and civil service, vis-à-vis independent variables – potential “drivers of trust” – in the Trust Survey dataset. These regressions covers 18 countries with the most fully available and comparable data on institutional trust and its determinants: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Estonia, France, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, and Sweden.

The empirical analysis of the drivers of trust is based on logistic regressions. The logit explores the degree to which trust has a significant relationship with respondents’ perceptions of responsiveness, reliability, openness, integrity, and fairness of government and public institutions – the core components of the OECD Trust Framework (Chapter 1). These five dimensions are operationalised utilizing 14 variables, originally measured on a 0-10 scale.

Institutional trust, here the dependent variable, is separately measured using three different variables: trust in the national government, trust in the local government, and trust in civil service. The survey question is phrased as follows: “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust each of the following?”. For the logit regression the dependent variable is recoded as a dummy. It takes value 0 for responses 0-4 on the original 11-points scale, and value 1 for responses 6-10. Response 5, “Don't know” and “Prefer not to say” are excluded.

In addition to these core components, the predictors include 5 variables measuring: internal and external efficacy (both on an 11-points scale), satisfaction with administrative services (same scale), confidence in one’s country’s ability to respond to the ecological challenge (5-points scale), and affiliation with national government (i.e. whether the respondent voted for the incumbent). Overall, the final set of predictors consists of 19 variables. All of them (but the last one) are standardised.

For each dependent variable, a sub-set of predictors is selected based on stepwise regression. All models include the following control variables: socio-demographics (age, gender, education), interpersonal trust, and country dummies. Variable weights are included in the regression. Each country weighs equally. Missing data are excluded using listwise deletion.

In Figures 2.7, 2.8, and 2.9, the coefficients (blue bars, with percentage point change scale in the left y-axis) are average marginal effects. They read as the percentage points change in trust associated with a one-standard-deviation change in the predictor.

Only the most significant public governance drivers are presented, but it is worth noting that socioeconomic or other individual-level traits (not shown) are often statistically significant. Having voted for the incumbent government, for example, is the independent variable with the largest (and significant) relationship with trust in national government. Having voted for the incumbent is also statistically significantly related with trust in the local government, though the size of the coefficient is smaller. The results are largely robust to the choice of model; the direction and significance of coefficients are similar when an ordinary least squares model is applied.

References

[4] Dahlström, C. and V. Lapuente (2021), “Bureaucracy and Government Quality”, in The Oxford Handbook of the Quality of Government, Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/OXFORDHB/9780198858218.013.31.

[1] Moss, F. and B. Vijayendra (2018), When difference doesn’t mean different: Understanding cultural bias in global research studies, Ipsos.

[3] OECD (2021), Public Employment and Management 2021: The Future of the Public Service, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/938f0d65-en.

[5] Saglie, J. et al. (2021), Lokalvalget 2019: Nye kommuner – nye valg?, Nordic Open Access Scholarly Publishing, https://doi.org/10.23865/NOASP.134.

[2] Yoshino, R. (2015), “Trust of Nations: Looking for More Universal Values for Interpersonal and International Relationships”, Behaviormetrika, Vol. 42/2, pp. 131-166, https://doi.org/10.2333/BHMK.42.131.

Notes

← 1. The OECD Trust Survey finds that trust in national government is slightly higher – by about 2 percentage points – than trust in local government in Norway. While it is a very small difference, this stands in contrast to the order of trusted institutions in other countries and in contrast to the results of a Norwegian elections study that measured trust. In this 2019 Norwegian elections study, trust in the municipal council is 5.7 on average – in line with the OECD average result, but higher than trust in the national parliament (5.5) and the national government (5.4) (Saglie et al., 2021[5]). These differences demonstrate that trust levels fluctuate. One potential source of these discrepancies is the timing of the surveys. Trust tends to be higher following elections, which could have influenced the trust averages in the local election study, while the OECD trust survey was fielded during the COVID-19 pandemic.

← 2. In the model this is measured as an increase in one standard deviation.

← 3. In the model this is measured as an increase in one standard deviation.