People’s trust in government depends on demographic and socioeconomic traits like age, gender, educational background, and income, as well as on their perceptions of their social status and their political attitudes. The relative importance of these factors, in addition to broader economic, cultural and institutional conditions in a country, has been shown in in-depth OECD country studies in Korea, Finland and Norway. This chapter presents a stocktaking of the relationship between different traits, socioeconomic conditions and institutional trust across countries.

Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy

3. Socioeconomic conditions and political attitudes: Microfoundations of trust

Abstract

Key findings and areas for attention

People with lower levels of education and income report consistently lower trust in government than other groups. On average across countries, having a university degree is associated with a difference of around 8 percentage points higher trust in government. Similarly, the gap in trust in government when comparing those with the highest and lowest incomes in society is twelve percentage points.

Young people trust government less. On average 36.9% of people aged 18 to 29 tend to trust their government, while the rate is 45.9% for those aged 50 and over. There is also a gender gap in trust with women trusting the government 2.7 percentage points less than men, on average, across countries. Governments should focus on the long-term economic and social consequences of the COVID‑19 crisis on young people, including on opportunities for young people to shape responses and enhance public participation.

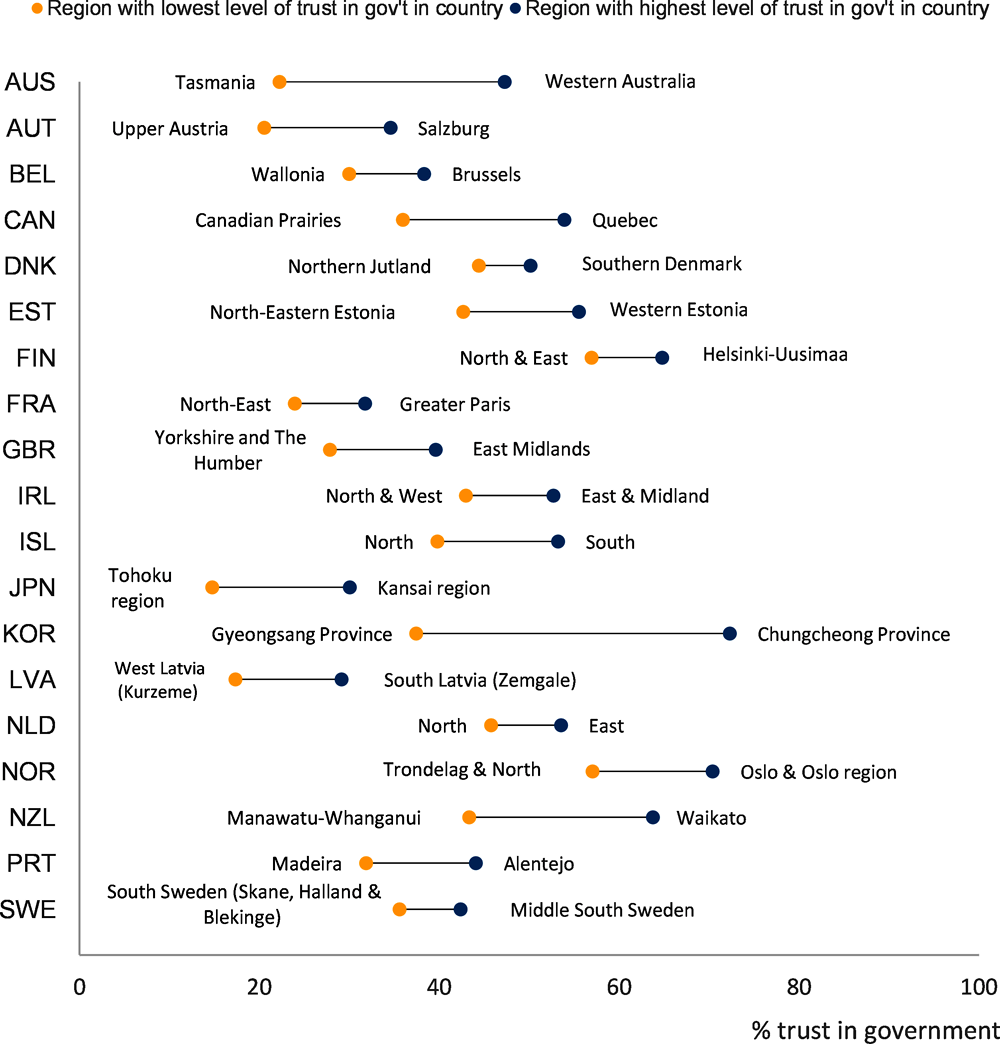

There are considerable differences in trust in institutions across regions within countries. Governments must pay attention to territorial divides to better understand the role of socio-economic factors and dissatisfaction with regional access to public services.

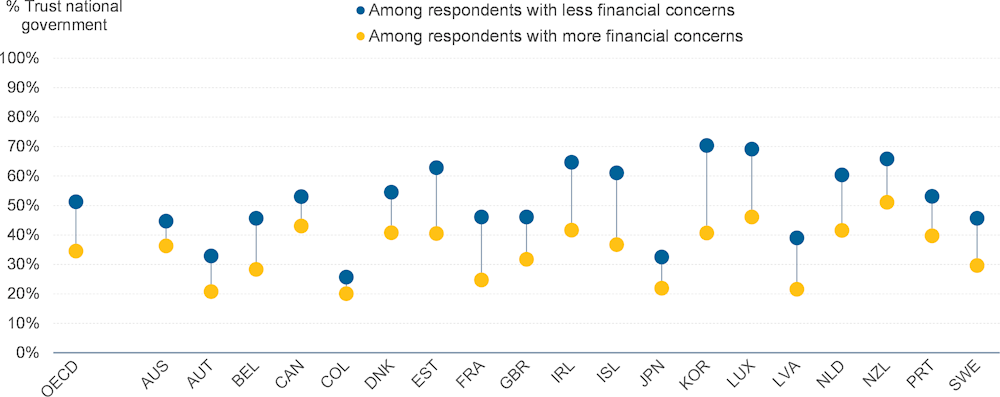

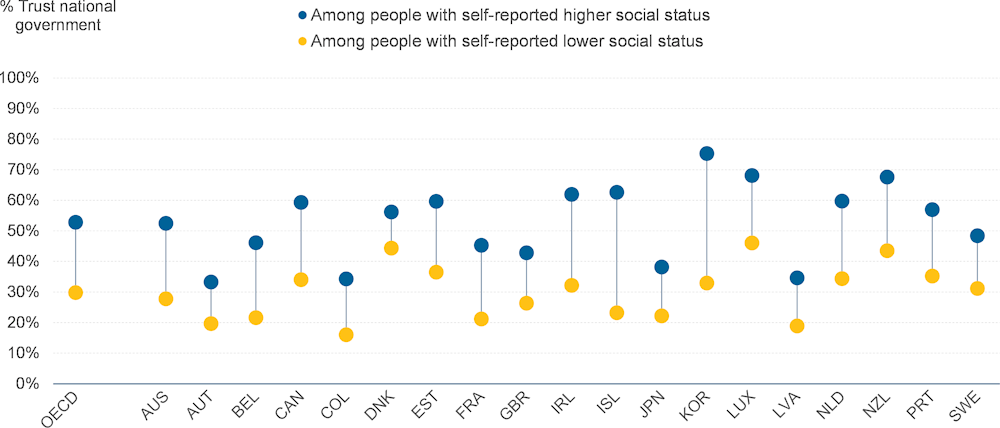

Perceived vulnerabilities seem to matter even more than reported socioeconomic vulnerability measured by income and education. Trust is considerably lower among people worried about their personal financial circumstances: only 34.6% of the financially precarious group trust the government, compared to 51.2% among people with fewer financial worries. The gap in trust between those who consider themselves to have a relatively higher social status and those with a low social status is around 22.9 percentage points.

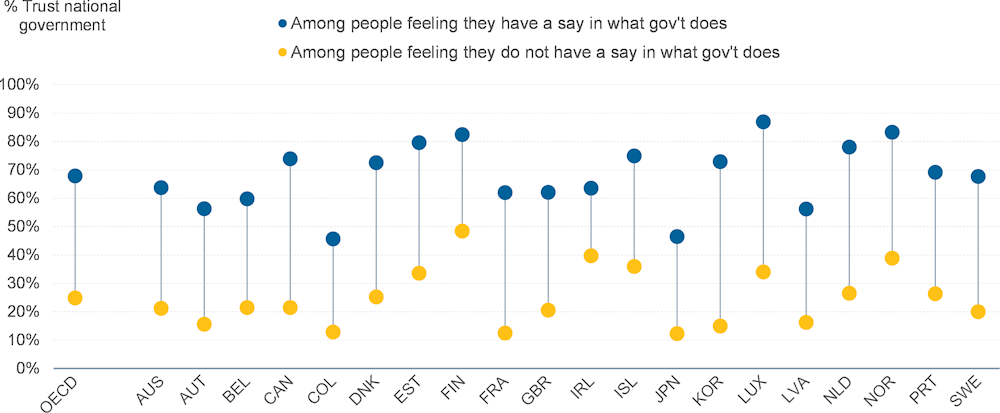

Partisanship and feelings of political efficacy matter, too. People who voted for the government in power are, on average almost twice as likely to say that they trust the government than people who did not vote for the current government. Perhaps related to that, feelings of political disempowerment diminishes trust. Only 24.9% of people who feel they do not have a say in what government does trust the government, on average across countries. Governments must recommit to inclusive governance that incorporates diverse and disadvantaged perspectives in policy design, implementation and reform and increase representation of different views.

These results show that governments face different starting points when attempting to foster trust in public institutions. Understanding key differences and drivers across population groups can help governments to better target and inform public policies.

3.1. People with low income and low levels of education are less trusting of government institutions

Consistent with previous results (Brezzi et al., 2021[1]), the OECD Trust Survey finds that people with higher levels of education or higher income tend to have higher trust in their national government than people with lower levels of education or lower income. On average in OECD countries, having a university degree, relative to only a high school degree, is associated with 8 percentage points higher trust in government. (For more on the scale used for these questions, see Box 4.1).

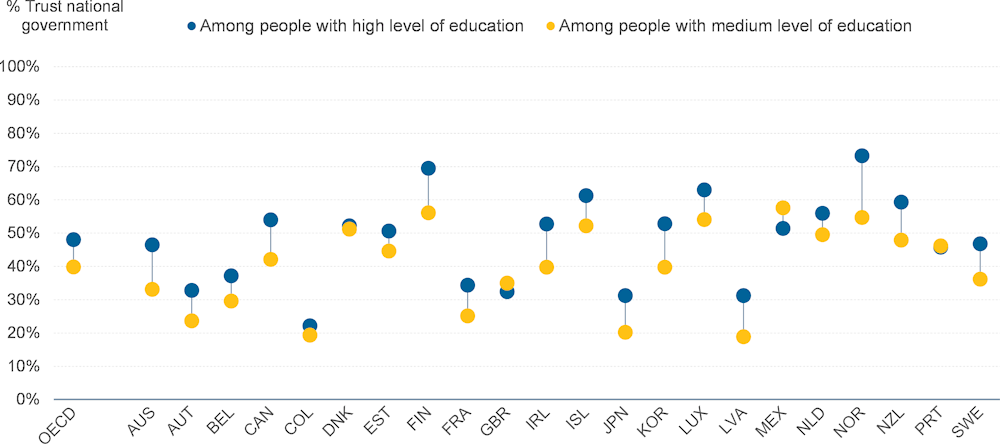

The average level of trust for those with the highest levels of education (university-level/tertiary) is 48.0%, as compared to 39.9% for those with medium levels of education (those who completed upper secondary education, i.e. high school) (Figure 3.1). The largest trust gap between these two groups can be found in Norway (18.6 percentage points) followed by Australia, Finland, Ireland and Korea (more than 13 percentage points). In Colombia, Denmark, Estonia, Portugal, Mexico, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, the trust gaps by education are considerably smaller.

Figure 3.1. People with tertiary education tend to have higher trust in government

Note: Figure presents the national distribution of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?”. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that “trust” the national government (i.e. response values 6-10), grouped by highest level of education. “Higher” education refers to ISCED 2011 levels 5-8, which refers to university-level degrees such as Bachelors, Masters or PhD, while “Medium” education refers to levels 3-4, or upper and post-secondary, non-tertiary education. “Low education” – which refers to less than a completed upper secondary degree – is excluded from this chart due to a lower share of the population in this group in most OECD countries. The trust estimates for the low education group tend to be lower than that of the medium education group. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries. Mexico and New Zealand here show trust in civil service as respondents were not asked about trust in the national government (note that trust in civil service on average tends to be higher than trust in national government). In case of the Netherlands, a translation error could have led to some people reporting medium rather than high level of education. For more detailed information, please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

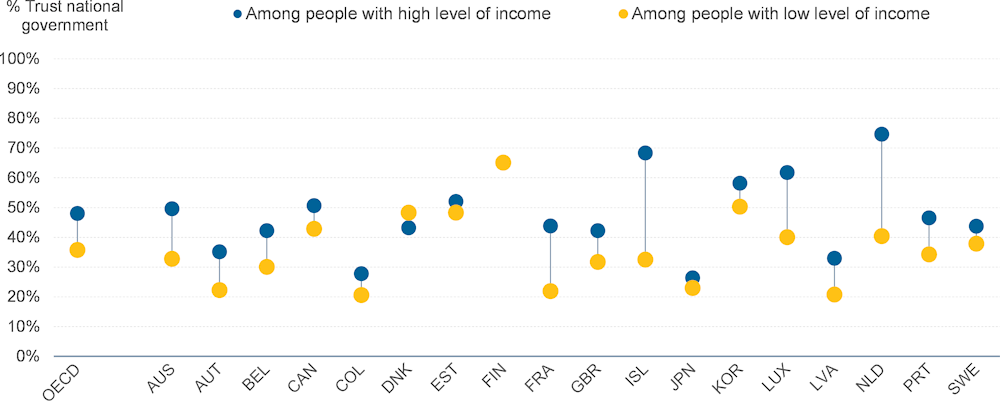

Trust Survey data show that in most surveyed OECD countries people with higher incomes have also greater trust in the national government. 48% of people with earnings in the top 20% of the national income distribution trust the government, as opposed to 35.7% in the bottom 20% of the income distribution (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. In most countries, people with low income tend to trust the government less

Note: Figure presents the national distribution of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust each of the following? The national government”. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that “trust” the national government (i.e. response values 6-10), grouped by income group. “High” and “Low” income refers to top and bottom 20% in national income distribution. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries. Ireland and Mexico are excluded from this figure as the data were not available. New Zealand and Norway are also excluded as data are only available on gross income, which complicates comparisons. Difference between high and low income groups in Finland are very small (0.1 percentage points). For more detailed information please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

3.2. Younger people and women tend to have lower trust in government

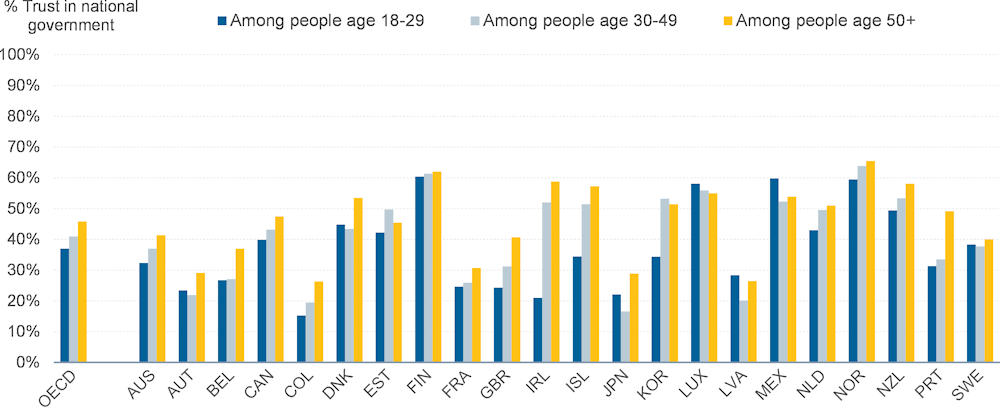

In all surveyed OECD countries, with the exception of Latvia, Luxembourg and Mexico, younger people tend to trust the government less than older people. On average 36.9% of people aged 18 to 29 tend to trust the government, 40.9% of those aged between 30 and 49 trust the government, and 45.9% aged 50 and over do (Figure 3.3). However, there are notable differences across countries. For instance, differences in trust between older and younger people are minimal in Latvia, Estonia, Sweden, Luxembourg and Finland, while they seem comparatively large in Ireland, Iceland, Portugal and Korea.

The economic and social consequences of the COVID-19 crisis have fallen particularly hard on young people, raising growing concerns about the long-term implications it may have on their material conditions and well-being, but also on opportunities for young people to shape responses and enhance public participation (OECD, 2022[2]). Governments can take specific actions to develop capacity for young people to participate, eliminate barriers for meaningful representation, and enhance democratic dialogue with young people on policies to address climate change, rising inequality, and threats to democratic institutions (OECD, 2022[2]).

Figure 3.3. Younger people tend to have lower trust in government

Note: Figure presents the within-country distributions of responses by age group to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust each of the following? The national government”. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that “trust” based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale, grouped by age group. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries. Finland's scale ranges from 1-10 and the higher trust / neutral / lower trust groupings are 1-4 / 5-6 / 7-10. Mexico and New Zealand present trust in civil service as respondents were not asked about trust in the national government (note that trust in civil service on average tends to be higher than trust in national government). Younger age group in Ireland is defined as 18-34 due to statistical disclosure measures. For more detailed information please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: http://oe.cd/trust

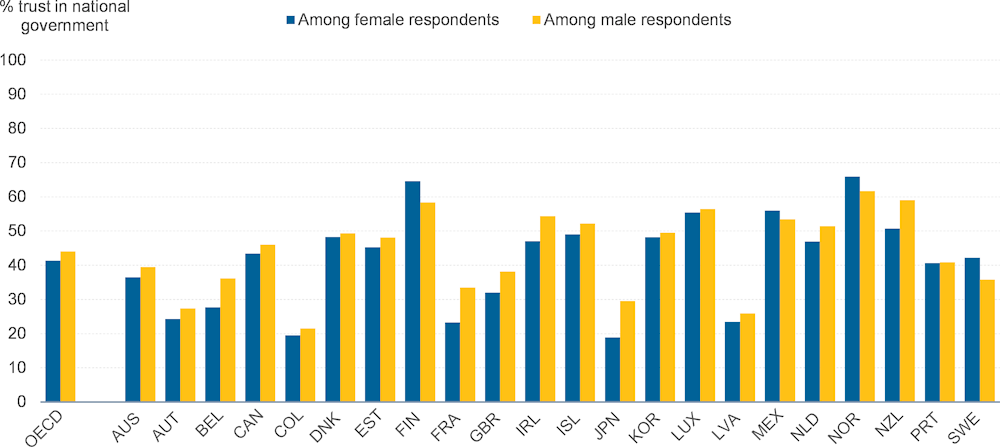

Trust in government also differs by gender, and in almost all surveyed OECD countries women have lower trust in government than men. The gender gap on average across countries is 2.7 percentage points (Figure 3.4).

Many potential causal mechanisms could be driving these results. For example, women’s lower trust in government could be related to lower economic or educational opportunities for women or other forms of structural gender inequality in society. Moreover, women remain underrepresented in politics and public institutions, including in terms of seats in national legislatures and ministerial posts (OECD, 2021[3]). It is noteworthy that the handful of countries in which women have more trust in government than men are some of the Nordic countries: Sweden, Finland and Norway.1 While even these countries have not yet achieved gender parity, they are often considered champions of gender equality within the OECD in terms of women’s economic empowerment, legal rights, and political representation (OECD, 2018[4]; OECD Gender Data Portal, 2021[5]). Women’s relatively higher trust in government in these Nordic countries may reflect women’s more equal opportunities there, at least relative to other countries.

Figure 3.4. In most OECD countries women have lower trust in the national government than men

Note: Figure presents the within country distribution of responses by gender to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust each of the following? The national government”. Shown is the proportion of respondents that “trust” based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 11‑point scale, grouped by gender. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries. Mexico and New Zealand show trust in civil service as respondents were not asked about trust in the national government (note that trust in civil service on average tends to be higher than trust in national government). For more detailed information please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

3.3. Regional variation in levels of trust

Trust in institutions also displays some clear geographical patterns and divisions across different places within countries. For example, differences in trust in institutions between regions can be very large in some countries, such as Korea (34.9 percentage points) and Australia (25 percentage points) for trust in national government or New Zealand (20.4 percentage points) for trust in the civil service (Figure 3.5). Differences between regions are generally smaller in Scandinavian countries, the Netherlands, and France, although cross-country comparison may be limited by the different population size and administrative geography of the available regions; further analysis by typology of regions, whether urban, predominantly rural, or in between, may provide more accurate insights.

There is a need for policy makers to pay attention to these gaps, as territorial disparities in trust could reflect people’s dissatisfaction with regional access to public services, as well as with local socio-economic opportunities and well-being outcomes. These elements can fuel feelings of being “left behind”, as well as disengagement or dissatisfaction with the political system, which can undermine democracy (Dijkstra, Poelman and Rodríguez-Pose, 2019[6]). Increasing the focus on places in decline by developing place-based strategies for regional economic development, and improving public services delivery in rural areas and deprived urban areas, can help address these territorial divides (OECD, 2019[7]).

Figure 3.5. Trust in government shows large regional disparities within OECD countries

Note: Shown here is the proportion of respondents that “trusts” the national government based on aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale, based on responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust each of the following? The national government”. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries. Finland's scale ranges from 1-10 and the higher trust / neutral / lower trust groupings are 1-4 / 5-6 / 7-10. New Zealand shows trust in civil service as respondents were not asked about trust in the national government (note that trust in civil service on average tends to be higher than trust in national government). Colombia, Luxembourg and Mexico are not shown due to data unavailability. Regions within countries are sub-national geographical areas and do not always correspond to administrative regions according to the OECD-EC classification (for more details the Trust Survey methodological note (http://oe.cd/trust) and the OECD Territorial Grid (https://www.oecd.org/regional/regional-statistics/territorial-grid.pdf).

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

3.4. Feelings of insecurity correspond with lower trust in public institutions

Low levels of trust in government and public institutions are also related to perceptions of vulnerability and being left behind economically, socially and politically. The results of the Trust Survey consistently illustrate that people’s personal financial concerns (Figure 3.6), perceptions of relatively lower status in society (Figure 3.7), and feeling excluded from government decision making (Figure 3.8) all negatively influence trust in government.

Economic insecurity or vulnerability can be measured in many different ways, such as unemployment or underemployment, low or irregular income, job insecurity, or high debt, among others. It is also a subjective measure, reflecting one’s perception of their economic status. The Trust Survey shows that a remarkable 63.5% of respondents report that they are “somewhat” or “very” concerned about their household’s finances when looking ahead to 2022 and 2023.

This is important. Economic vulnerability likely affects people’s attitudes towards public institutions, and indeed the survey finds that people with financial worries are much less trusting of the national government than those with few or no financial worries: only 34.6% of the financially precarious group trusts the government, compared to 51.2% among people with fewer financial worries (Figure 3.6). The gap between groups is largest in Korea (30 percentage point gap), followed by Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg and Estonia.

Figure 3.6. People with personal financial concerns are less likely to trust the government

Note: Figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the questions “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust each of the following? The national government”. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that reported to trust the government (response categories 6-10) by their level of financial concern. The marker for higher levels of financial concern represent the aggregation of response choices “Somewhat concerned” and “Very concerned” in response to the question “In general, thinking about the next year or two, how concerned are you about your household’s finances and overall social and economic well-being?”. The marker for lower levels of financial concern represent the aggregation of response choices “Not at all concerned” and “Not so concerned”. New Zealand shows trust in civil service as the question on trust in government was not asked (note that trust in civil service on average tends to be higher than trust in national government). “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries. Finland, Mexico, and Norway are excluded from this figure as the data were not available. For more detailed information please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

Beyond economic or material risks, a sense of one’s own social status appears to be strongly related to people’s level of trust in government. In all surveyed countries, people who report a lower perceived social status (measured as one’s own reported position in society, relative to others) also report a lower level of trust in the national government (Figure 3.7). On average across OECD countries, the trust gap between those who consider themselves to have a relatively higher social status and those with a low social status is around 22.9 percentage points, a value much higher than the difference between actual reported income or education. Differences between groups are particularly pronounced in Korea, Iceland, and Ireland and differences are less pronounced in Austria, Denmark, Japan and Latvia. This provides some early evidence on the importance of social inclusion as a factor related to people’s trust in government.

However, it is important to highlight that survey respondents were reporting their perceptions of their own social status, which was not explicitly defined and could include a number of individual material and non-material factors. As with other characteristics presented in this chapter there could be other underlying factors driving both perceptions of status and trust, such as access to public services, individual preference on state intervention, or opportunities in life related to work and education.

Figure 3.7. People with a low self-reported social status have also lower trust in government

Note: Figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the questions “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust each of the following? The national government”, and “If you imagine status in society as a ladder, some groups could be described as being closer to the top and others closer to the bottom. Thinking about yourself, where would you place yourself in this scale? (1-10 scale)”. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that reported to trust the government by level of self-reported social status. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries. . New Zealand shows trust in civil service as respondents were not asked about trust in the national government (note that trust in civil service on average tends to be higher than trust in national government). Finland, Mexico and Norway are excluded from this figure as the data were not available. For more detailed information please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: http://oe.cd/trust

Finally, people who feel excluded from government decision making have lower levels of trust in government. Feelings of a lack of political voice not only are associated with low (or lack of) political participation,2 but also with low trust in public institutions (Prats and Meunier, 2021[8]).

On average, among those who report they have a say in what the government does, 67.9% of people trust their national government, while only 24.9% report trust in national government among those who feel they do not have a say in what the government does (Figure 3.8). Further, people’s trust in government is also positively related to confidence in their ability to participate in politics. On average for surveyed OECD countries, 53.4% of people that are confident in their own ability to participate in politics have trust in their national government. Yet the figure for those with low confidence in their ability to participate is only 31.5%. In this regard, trust in government is associated with feeling politically included, both at the system, as well as at individual level.

Figure 3.8. People who feel they have a say in what the government does have also higher trust in government

Note: Figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the questions “On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, in general how much do you trust the national government”, and “How much would you say the political system in [country] allows people like you to have a say in what the government does?”. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that report to trust the national government (response categories 6-10) by whether they feel they have a say in what the government does. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries. Mexico and New Zealand are excluded from this figure as respondents were not asked about trust in the national government. For more detailed information please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

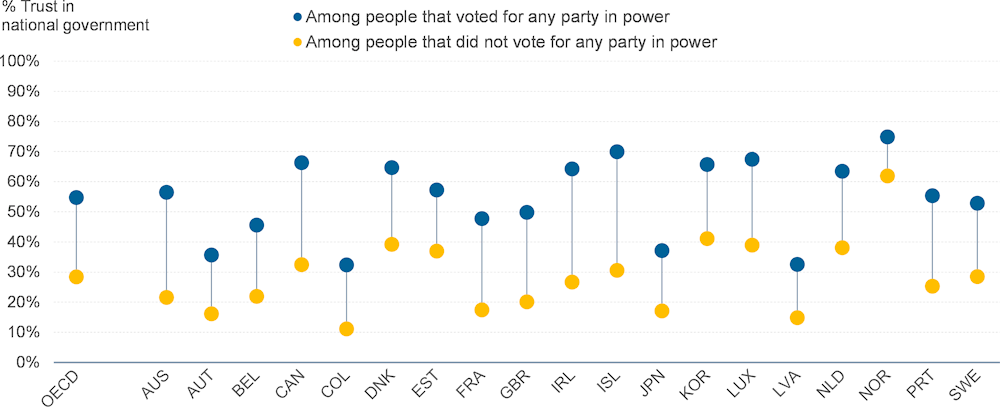

In addition to feelings of having a say in political issues, people’s trust in public institutions is also highly influenced by individual political preferences. Trust in government institutions is generally higher among people who voted for the party or parties currently in power. People who did not vote for incumbents tend to trust all public institutions less, even apolitical ones such as civil service or the police. This may be a signal of people feeling excluded or outside of the democratic system, if they position themselves politically as opposition. This may also indicate a scenario of increasing political polarisation and thus the need to further strengthen the inclusivity of public institutions. On average, trust in the national government is 54.7% among people who voted for the parties in power, while only 28.4% for those who do not vote for the ruling parties (Figure 3.9). Similar results hold across other public institutions, even ostensibly apolitical ones, but the gap tends to be smaller. For instance, 55.6% of those who voted for the incumbent government trust the civil service while the share is only 46% for those who did not vote for party/parties in power.

Figure 3.9. Trust in government is lower for people that did not vote for parties in power

Note: Figure presents the share of people that report they trust the civil service, by whether the party they voted for in the last national election (or would have voted for if they didn't vote) is currently part of the government. Trust in national government based on aggregation of response categories 6-10 to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust each of the following? The national government”. Vote for current government based on question “Is the party you voted for in the last federal (national) election (or would have voted for if you didn't vote) currently part of the government?”. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries. Finland, Mexico and New Zealand are excluded from this figure as the data were not available. For more detailed information please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

3.5. Culture and socialisation play a part

This chapter has illustrated the role that individual-level factors play in mediating trust in government institutions. Yet it is important to note that people’s attitudes towards government do not develop in a vacuum. An individual’s broader cultural, family, political and social environment plays an enormous role in influencing preferences and attitudes towards government throughout a lifetime. This socialisation is a long process spanning from early childhood to old age. It affects many aspects of social life, from interpersonal relationships to political participation (Neundorf and Smets, 2017[9]) (Sapiro, 2004[10]).

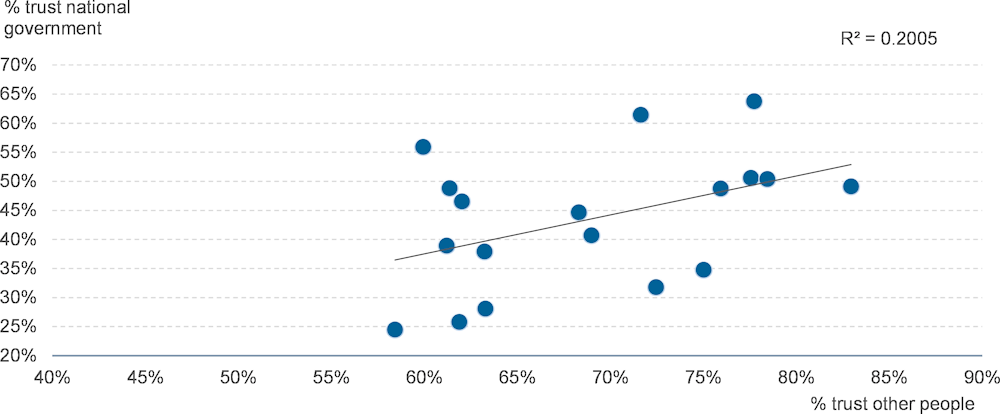

One very simple illustration of the role of culture and socialisation is the relationship between interpersonal trust and trust in government institutions (Figure 3.10). Cross-nationally, there is a positive correlation between reported levels of trust in other people, in general, and reported levels of trust in government.3 While this measure does not fully capture the effects of “culture” or “society”, it helps to illuminate the degree to which other underlying, group-level conditions influence trust in institutions. These less tangible factors could be culture, norms, level of inequality, level of poverty, level of economic development, and/or degree of racial/ethnic heterogeneity, among many other possible determinants. Many of these factors are unobservable – and the factors that can be measured quantitatively likely interact with each other.

The degree of trust in others can also help situate country-specific responses towards trust in general and government specifically; survey responses on trust may reflect diverse cultural or social variation across countries. This should be considered in comparisons on the levels of trust in government.

High levels of interpersonal trust can help citizens to act together, demand policies that benefit them collectively, and hold the government accountable. Given the interplay between interpersonal and institutional trust, governments should consider strengthening the representation of collective interests including of disadvantaged groups, for example by fostering civic space and strengthening collective interest organisations.

Figure 3.10. Trust in government correlates with trust in other people

Note: Figure presents the relationship between the proportion of people that “trust” other people and the share that “trust” in national government, based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale to the questions “On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, in general how much do you trust most people?”, and “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?”. “OECD” represents the unweighted average across countries. Mexico and New Zealand are excluded from this figure as respondents were not asked about trust in the national government. Japan is excluded from this figure as an outlier on interpersonal trust. For more detailed information find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

References

[1] Brezzi, M. et al. (2021), “An updated OECD framework on drivers of trust in public institutions to meet current and future challenges”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 48, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6c5478c-en.

[6] Dijkstra, L., H. Poelman and A. Rodríguez-Pose (2019), “The geography of EU discontent”, Regional Studies, Vol. 54/6, pp. 737-753, https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1654603.

[9] Neundorf, A. and K. Smets (2017), “Political Socialization and the Making of Citizens”, Vol. 1, https://doi.org/10.1093/OXFORDHB/9780199935307.013.98.

[2] OECD (2022), “Delivering for youth: How governments can put young people at the centre of the recovery”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/92c9d060-en.

[3] OECD (2021), Government at a Glance 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

[7] OECD (2019), Making Decentralisation Work: A Handbook for Policy-Makers, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9faa7-en.

[4] OECD (2018), Is the Last Mile the Longest? Economic Gains from Gender Equality in Nordic Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264300040-en.

[11] OECD (2017), Trust and Public Policy: How Better Governance Can Help Rebuild Public Trust, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268920-en.

[5] OECD Gender Data Portal (2021), OECD Gender Data Portal, https://www.oecd.org/gender/data/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

[8] Prats, M. and A. Meunier (2021), “Political efficacy and participation: An empirical analysis in European countries”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 46, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4548cad8-en.

[10] Sapiro, V. (2004), “Not your parents’ political socialization: Introduction for a new generation”, Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 7, pp. 1-23, https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.POLISCI.7.012003.104840.

Notes

← 1. This figure shows women in Mexico trusting government more than men, but note that these estimates for Mexico refer to trust in the civil service, as data on trust in the national government are not available in the Trust Survey in Mexico. While Mexico has well known and persistent barriers to gender equality (see for example (OECD, 2017[11]), this result on the civil service might be related to the relatively extensive reach of the state in many Mexican women’s lives, for example through the build-up of educational and healthcare institutions related to previous conditional cash transfer systems.

← 2. Political participation is broadly understood as those activities undertaken by the public to influence political decisions, either directly or by affecting the selection of persons who make policies (Prats and Meunier, 2021[8]).

← 3. The correlation coefficient at the country level is 0.45. The multivariate regressions at the level of individual respondents confirm a highly significant relationship between trust in the national government and trust in other people.