This chapter provides a brief snapshot of recent macroeconomic development in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia (EECCA), including the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and issues related to ongoing recovery. It also shows how Russia’s war against Ukraine is affecting the country’s ecosystems and human health, as well as the policy environment for green reforms in the region more broadly. As a precursor to more in-depth discussion in Chapters 3, 4 and 5, it also highlights key environmental challenges in the region and recent progress to address them using selected Green Growth Indicators.

Green Economy Transition in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia

2. Recent socio-economic and environmental trends towards sustainable development in EECCA

Abstract

Recent macroeconomic development

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia (EECCA)1 have been undergoing profound changes, while pursuing their transformation towards market economies and democratic societies. Even as they conserved some of their Soviet-period specialisations, most of the region’s economies underwent major structural changes, trade liberalisation and privatisation. For example, the share of the service sector in the economy has dramatically increased in most EECCA countries (Gevorkyan, 2018[1]).

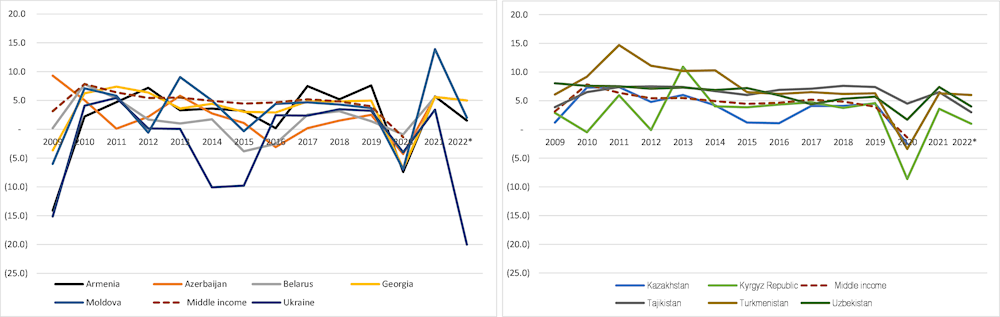

On average, the EECCA region had maintained relatively good economic growth rates over the past two decades (3.4 % on annual average from 2001 to 2021) (World Bank, 2022[2])). However, the macroeconomic situations surrounding the EECCA region have been turbulent over the past decade (Figure 2.1). The global financial crisis in the late 2000s drops in commodity prices and political instability in Armenia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan, for example, have all affected economic growth rates in EECCA countries.

The most recent external shocks to EECCA economies are the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic consequences, and Russia’s war against Ukraine launched in February 2022. The impact of COVID-19 pushed down gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates by 5-13 percentage points across all EECCA countries in 2020 (Figure 2.1). While year-on-year GDP growth started to pick up again to more than 3% in the region for 2022 (World Bank, 2022[3]), the war in Ukraine has led to a significant recession. It is forecasted now for almost all EECCA countries and likely to worsen depending on how the war in Ukraine evolves (World Bank, 2022[3]; EBRD, 2022[4]; Kammer et al., 2022[5]). The GDP contraction of -0.2% that is projected for EECCA countries,2 excluding Ukraine, for 2022 could be downgraded further.

Figure 2.1. GDP growth rates between 2009 and 2022 in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia

The post-COVID-19 recovery and Russia’s war in Ukraine are forcing the EECCA region to make decisions under significant uncertainties associated with a complex combination of challenges. They include increased commodity and energy prices, pressure on energy security, refugee flows, and significantly reduced remittances and tourist inflows. These emerging challenges also compound longer-term development policy agendas, such as eradication of poverty and discrimination, gender equality and provision of social security. At the same time, countries are trying to address climate change, biodiversity loss and other environmental degradation. These emerging and protracted challenges require EECCA countries to re-evaluate how governments run their economies and pursue various development agendas.

Effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on climate and energy policies across the EECCA region

Prior to Russia’s large-scale aggression against Ukraine, EECCA countries had already made significant progress on aligning their environmental and climate policies with global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and adapt to the negative impacts of climate change. The countries had also adopted a variety of policy and fiscal instruments to support recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic combined with the goals of building robust, resilient and sustainable economies (OECD, 2021[6]).

The war in Ukraine has caused tens of thousands of casualties, an associated humanitarian crisis, a large number of besieged and displaced people both within Ukraine and abroad, and significant negative economic impacts. The environment, natural resource base and infrastructure have not been spared by the war [See Box 2.1 and OECD (2022[7])].

The war has also created major policy challenges and already led to a geopolitical and economic reconfiguration across most of the EECCA countries. It has already led to sanctions on Russia by OECD countries (and Russian countersanctions), as well as trade disruption and the significant increase in energy and commodity prices (Berlin Economics & OECD, 2022[8]).

Climate and energy policies of EECCA countries, among other policy domains, may face significant alterations due to the impacts of the war through multiple channels. Key results of a recent analysis of the effects of the war in Ukraine on climate and energy policies in the EECCA region are highlighted below (Berlin Economics & OECD, 2022[9]).

First, energy price developments severely affect the EECCA countries’ economies. Russia is a major exporter of oil, oil products, natural gas, coal and nuclear fuel. The war led to an increase in global crude oil prices. The price of natural gas and coal has risen even more compared to the oil price.

Second, the price increase for food and metals has had a significant negative impact on the economies of the EECCA countries, and the rest of the world; Ukraine and Russia are major producers of a variety of metals and agricultural goods. Transport of products from Ukraine has been facing severe disruptions due to the war and Russia’s blockade of trading routes. The European Union has partially sanctioned Russian steel. Meanwhile, Russia has banned exports of several agricultural commodities. The impact of the shortage of food exports available on the market is particularly affecting low-income countries that depend on imports from Russia or Ukraine.

Conversely, many EECCA countries rely on metals and mining for large parts of their GDP and exports (e.g. Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan). For them, higher prices might incentivise production increases in the short- to mid-term. This could adversely impact GHG emissions and implementation of climate policies.

Third, the global macroeconomic situation for most economies across the world has changed drastically. Prior to the invasion, EECCA countries were already facing supply constraints and inflationary pressures due to compromised supply chains since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since Russia’s aggression, the economic outlook for all EECCA economies except Azerbaijan has been revised downwards due to trade disruptions, high food prices and insecure energy supplies.

Public debt has significantly increased since the start of the pandemic. A weaker regional macroeconomic situation could complicate the countries’ effort towards more ambitious national climate policies. Debt aggravates financing of climate-related investments from domestic sources. Yet lower growth may lead to lower GHG emissions in the short term (at the expense of improved economic and social conditions).

Fourth, since Russia’s war against Ukraine began, OECD Member countries are aiming to reduce dependence on Russian energy. In the short term, this means oil-producing countries will need to produce more domestic energy or try to diversify energy carrier import partners. In the long term, it means reducing overall fossil-fuel consumption by increasing decarbonisation.

Russia supplies a significant part of the energy mix of most EECCA countries. Parts of their energy infrastructures are even owned by Russia. All countries cover a significant share of their energy supply with oil products, and most countries (except Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) have relatively high levels of natural gas in their energy mix. Kazakhstan is heavily reliant on coal, while Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan rely on a mix of coal and hydropower. Hydropower also plays an important role in Georgia and to a lesser extent in Armenia. In the Central Asian countries, coal is mostly domestically extracted, while Armenia, Georgia and Moldova have almost no domestic fossil-fuel production.

Countries maintaining strong relations with Russia face a somewhat complex set of incentives. These countries may face lower fossil prices, which weakens incentives to reduce fossil consumption. However, remaining price risks and political uncertainty in long-term relations with Russia have already led to the emergence of a new energy security paradigm. This emphasises the risk of depending on fossil imports from a single supplier (Berlin Economics & OECD, 2022[8]).

Energy export industries in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan have so far had windfall revenues due to high oil and gas prices. This increases the incentive to further expand export volumes. They could do this by increasing production, if faster extraction is possible. They could also conserve energy domestically as the opportunity cost of forgone export revenues has increased. However, export transmission capacity is limited. Consequently, an expansion of production cannot be directly translated into a further increase of exports (Berlin Economics & OECD, 2022[8]).

The emerging energy security concerns – high long-term fossil-fuel prices and increased price uncertainty – are expected to continue driving expansion of renewable energy sources in the medium- to long-term. Many countries in the region are working to strengthen their energy independence. Increasing energy efficiency and domestic energy production, in particular from renewable energy sources, provide an attractive alternative (Berlin Economics & OECD, 2022[8]). This holds especially true for Moldova and Ukraine, as well as Georgia. These countries have applied for EU membership and, therefore, need to implement more stringent EU regulation.

Box 2.1. Examples of environmental impacts of Russia’s war against Ukraine

Ukraine had made steady economic and environmental progress in recent years (OECD, 2022[10]). Russia’s war against Ukraine has been attacking such progress, setting back hopes for an independent, green and sustainable Ukraine. The economic impacts have also been significant. Recent estimates of the damage to housing, infrastructure and other non-residential buildings exceed USD 100 billion (Kyiv School of Economics, 2022[11]).

Apart from human casualty and economic damages, the war has also led to significant environmental destruction. Forests, land and marine ecosystems to water, sanitation and waste management infrastructure have all been damaged. This widespread and severe damage is bringing immediate and longer-term consequences for human health and ecosystems in Ukraine.

Strikes on refineries, chemical plants, energy facilities, industrial depots or pipelines have caused leaks of toxic substances, fires and building collapses and severely polluted the country's air, water and soil. This pollution can cause longer-term health threats like the risk of cancer and respiratory ailments. The Ukrainian Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources estimates that approximately 1.4 million people in Ukraine have no access to safe water. A further 4.6 million people have only limited access, due to damaged water supply infrastructure. Ukraine has also begun enhanced epidemiological surveillance of cases displaying cholera symptoms.

The amount of waste has dramatically increased. It includes damaged or abandoned military vehicles and equipment, shell fragments, civilian vehicles, building debris or uncollected household or medical waste, due to military operations. Some of this waste is toxic, including shell fragments, medical waste, or building debris containing asbestos, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and heavy metals.

The Ministry of Environmental Protection also estimates that 900 protected natural areas of Ukraine have been affected by Russia’s military activities. This means that approximately 30% (an estimated 1.2 million ha) of all protected areas of Ukraine suffer from the effects of war.

Source: OECD (2022), Environmental impacts of the war in Ukraine and prospects for a green reconstruction, www.oecd.org/ukraine‑hub/en/; Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources (2022), “Digest of the key consequences of Russian

aggression on the Ukrainian environment for June 9-15, 2022”, https://mepr.gov.ua/news/39320.html; and Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources (2022), “Damage to natural reserves and protected ecosystems, https://mepr.gov.ua/en/news/39144.html;

Main trends in greening the EECCA economies: State of play in 2022

This section provides a snapshot on how the environmental footprint of economic activities in the region has evolved over the past few years. Then, it is followed by Chapter 3, which will highlight a number of policy developments and challenges related to the journey of EECCA countries towards a green economy.

The OECD developed a measurement framework, called “Green Growth Indicators” in 2011, to track the progress towards green economy. The frame work consists of four main areas: productivity; natural asset base; quality of life; and policies. These indicators answer such questions as: Are we becoming more efficient in using natural resources and environmental services? How does greening growth generate economic opportunities? Is the natural asset base of our economies being maintained? Does greening growth generate benefits for people? See OECD (n.d.[12]) for further details of the Green Growth Indicators Framework and related publication and materials.

In the EECCA region the work on Green Growth Indicators started in 2012. Kyrgyzstan was the first country to pilot-test this set, followed by Armenia, Azerbaijan, Moldova and Ukraine since 2013 (see Box 2.2). Two regional reports have been developed. In 2019, Kazakhstan became the second among Central Asian countries, developing the GGIs and integrating the measurement of green growth into the regular reporting and planning system.

The Green Growth Indicators have been used to collect environmental data for the EECCA countries. This, in turn, can help the countries track and communicate progress in greening their economies, inform decisions and demonstrate accountability to national and international stakeholders. It can also raise public awareness about the links between economic growth and environmental protection, and compare progress between countries.

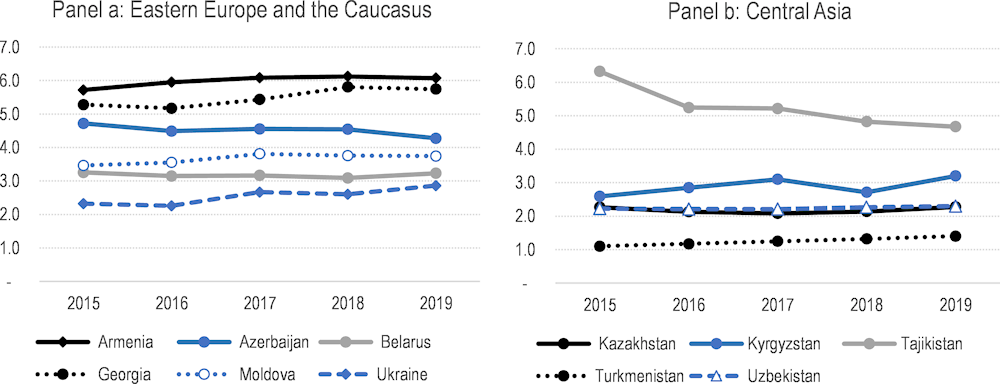

Carbon and energy productivity, resource productivity and multifactor productivity3 capture the efficiency with which economic activities (production and consumption) use energy, other natural resources and environmental services. In many EECCA countries, such as Armenia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Ukraine and Turkmenistan, both carbon dioxide (CO2) and energy productivities of the economies have improved substantially over the past five years. This means that economic growth partially decoupled from CO2 emissions and use of energy. Higher CO2 and energy productivity reflect a less polluting, more resource-efficient economy. However, pressure remains as CO2 and energy productivity continue to be much lower than the European average (7.23 USD/kg of CO2 in 2019). Some EECCA countries perform even less well than the world average (3.68 USD/kg of CO2 in 2019) (Figure 2.2 and Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.2. CO2 productivity (GDP per unit of energy-related CO2 emissions: USD per kg of CO2, 2015 price)

Note: CO2 productivity is measured based on production.

Source: OECD.stats Green Growth Indicators, https://stats.oecd.org/.

Figure 2.3. Energy productivity (GDP per unit of TPES: USD, 2015 price)

Note: TPES=Total Primary Energy Supply.

Source: OECD.stats Green Growth Indicators, https://stats.oecd.org/.

Indicators on environmental quality of life allow EECCA countries to monitor how environmental conditions and environmental risks interact with the quality of life and well-being of people. These indicators also point out how the amenity services of natural capital support well-being. Further, they can show the extent to which income growth is accompanied (or not) by a rise in overall well-being.

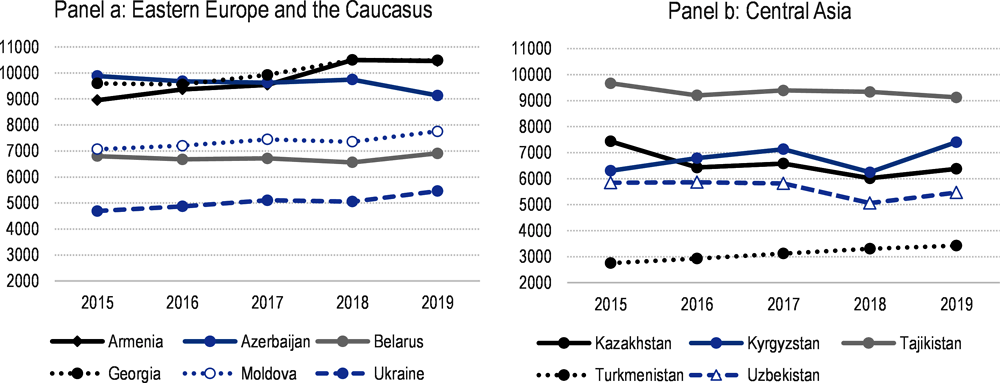

One indicator, for example, tracks fine particulate matter (PM2.5), one of the most serious pollutants globally from a human health perspective. In EECCA countries, exposure of the population to PM2.5 remains high. However, mortality (premature deaths) attributed to PM2.5 exposure has generally decreased in all countries over the past few years (Figure 2.4). Still, this mortality level is significantly higher than the EU average (382.5 per million inhabitants). Armenia and Ukraine have the most attributed deaths relative to population, with about 1 000 per million inhabitants in 2019.

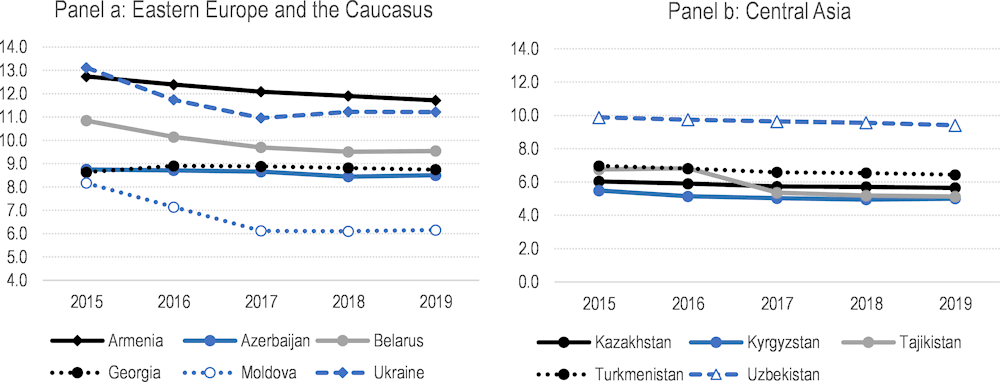

Associated welfare costs of premature deaths due to PM2.5 pollution represented in the EECCA region are also significant, despite the general trend of a decreasing rate over the past few years (Figure 2.5). In particular, welfare costs from premature deaths in Armenia, Ukraine and Uzbekistan are 10-12% of GDP equivalent. This is three to four times higher than the EU average of 3%, and double the worldwide rate (5.8%).

Figure 2.4. Mortality from exposure to ambient PM2.5 (per 1 000 000 inhabitants)

Figure 2.5. Welfare costs of premature mortalities from exposure to ambient PM2.5 (percentage of GDP)

Note: This indicator uses estimates of premature mortality and morbidity attributable to ambient PM2.5 air pollution to value the economic cost in dollar terms. This estimates the major health damages of population exposure to ambient PM2.5 from exposure-response relationships that have been established by global research on air pollution and health. The cost of premature deaths is estimated from the value of statistical life (VSL). VSL is a measure of how much individuals are willing to pay for a reduction in the risk or likelihood of premature death. VSL is influenced by income level and other factors; it is unique for each country.

Source: OECD.stats Green Growth Indicators, https://stats.oecd.org/.

The economic opportunities and policy responses indicators presented in this section aim at capturing the economic opportunities associated with green growth. They can help assess the effectiveness of policy to promote green technology and innovation, environmental goods and services, investment and financing, prices, taxes and transfers. In the EECCA countries, more economic opportunities associated with green growth can be unlocked. This includes investment in environmental protection, development of environmentally friendly technologies and removal of fossil-fuel subsidies that can reduce fiscal deficits, make renewable energy more competitive, and lower carbon and air pollution.

In this context, the recent inclusion of the Eastern Europe and Caucasus countries in the OECD-IEA database on fossil-fuel subsidies is an important milestone in transparency (OECD, 2021[13]). It also recognises the efforts of the governments of the Eastern Europe and Caucasus countries to disclose information on the size of their support to the energy sector. Further discussion and data can be found in Chapter 5.

Box 2.2. Good practice example: Using Green Growth Indicators for better policy making in Moldova and Ukraine

Some of EECCA countries have developed national sets of Green Growth Indicators (GGIs), which provides useful lessons for further improvement of the application of the Indicators across the region. In 2021, Moldova and Ukraine updated their national sets of GGIs with support of the EU-funded EU4Environment programme. This was an opportunity to access the countries progress towards a green economy in the recent years, with data sets up to 2020.

In Moldova, this was a first attempt to evaluate the implementation of the National Programme on the Promotion of Green Economy and its Action Plan 2018-20, based on GGIs. It also provided insights for the development of several strategic policy documents – the Program on the promotion of Green Economy and its Action Plan 2022-27 and the Environmental Strategy 2030.

The report revealed the positive trends, such as increase in efficiency of using natural resources (increase in carbon, energy and water productivity), maintain of natural asset base (slight increase in afforestation and protected areas), improve in quality of life (decrease of exposure of the population to fine particulate matter, increase in people’s access to safely managed drinking water services). The analysis also draws attention of policy-makers to the remaining challenges which require further action, such as increase in the forest share, improve waste management and recycling, reduce water pollution, promote eco-innovation, green jobs, enhance energy efficiency, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and scale up green investment.

To give more visibility to the analysis and its policy messages, a dedicated online platform on GGIs was created, first of its kind among the EECCA countries. The platform is hosted by the Ministry of Environment’s website, and available in English and Romanian languages.

The results of this analysis were also presented to the Inter-ministerial Working Group for the promotion of Sustainable Development and Green Economy in Moldova, which is the high-level co-ordination body on green economy promotion in the country. It was established jointly by the Ministry of Economy and Ministry of Environment in 2015.

In Ukraine, the special focus of the analysis was on monitoring implementation of the national environmental policy of Ukraine using GGIs. The analysis aimed to carry pilot monitoring of the implementation of the Law of Ukraine, “On Main Foundations (Strategy) of the State Environmental Policy of Ukraine for the Period until 2030”. The analysis revealed the positive results of the steps taken by the country towards a green economy in the recent years. Examples include increase in efficiency of using natural resources (increase in carbon and energy productivity), protection of natural asset base (increase of protected areas, decreasing pressure on freshwater resources), improve in quality of life (decreasing emissions of all pollutants, increasing share of households equipped with sewerage in rural areas).

The analysis also draws attention of policy makers to the areas which need further improvements – household waste, share of forest cover, dynamics of the protected species, degradation of agricultural lands, a high level of air pollution and associated mortality and economic costs, low research, and development expenditures. This exercise took place in light of the country’s commitments under the EU Association Agreement and engagement towards EU Green Deal.

Source: EU4Environment (2022), Towards Green Transformation of the Republic of Moldova: State of Play in 2021. Monitoring progress based on the OECD green growth indicators; EU4Environment (2022), Towards a Green Economy in Ukraine Work in Progress – 2019-20.

References

[8] Berlin Economics & OECD (2022), “Effects of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on climate and energy policies in the European Union’s Eastern Partnership and Central Asian countries”, Discussion Paper, GREEN Action Task Force, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/environment/outreach/ENV-EPOC-EAP(2022)6.pdf.

[9] Berlin Economics & OECD (2022), Effects of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on climate and energy policies in theEuropean Union’s Eastern Partnership and Central Asian countries, Prepared for the 2022 GREEN Action Task Force Annual Meeting, https://www.oecd.org/environment/outreach/ENV-EPOC-EAP(2022)6.pdf.

[4] EBRD (2022), “Regional Economic Prospects”, webpage, https://www.ebrd.com/what-we-do/economic-research-and-data/rep.html (accessed on 9 September 2022).

[1] Gevorkyan, A. (2018), Transition Economies, Routledge, London, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315736747.

[5] Kammer, A. et al. (2022), How war in Ukraine Is reverberating across world’s regions, IMF blog (15 March 2022), https://blogs.imf.org/2022/03/15/how-war-in-ukraine-is-reverberating-across-worlds-regions/ (accessed on 20 August 2022).

[11] Kyiv School of Economics (2022), “Direct damage caused to Ukraine’s infrastructure during the war has reached over USD 105.5 billion”, News, Kyiv School of Economics, https://kse.ua/about-the-school/news/direct-damage-caused-to-ukraine-s-infrastructure-during-thewar-has-reached-over-105-5.

[10] OECD (2022), “OECD-Ukraine Memorandum of Understanding”, webpage, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/countries/ukraine/oecd-ukrainememorandumofunderstanding.htm (accessed on 9 September 2022).

[7] OECD (2022), “War in Ukraine: Tackling the Policy Challenges”, webpage, https://www.oecd.org/ukraine-hub/en/ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

[6] OECD (2021), Aligning short-term recovery measures with longer-term climate and environmental objectives in Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia, GREEN Action Task Force, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/environment/outreach/ENVEPOCEAP(2021)4-GreenRecoveryEECCA.pdf.

[13] OECD (2021), Fossil-Fuel Subsidies in the EU’s Eastern Partner Countries: Estimates and Recent Policy Developments, Green Finance and Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/38d3a4b5-en.

[12] OECD (n.d.), Green Growth Indicators, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/green-growth-indicators/ (accessed on 18 August 2022).

[3] World Bank (2022), Europe and Central Asia Economic Update: War in the Region, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eca/publication/europe-and-central-asia-economic-update.

[2] World Bank (2022), World Development Indicators, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

Notes

← 1. EECCA countries include Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Republic of Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

← 2. Calculated based on individual country GDP growth forecasts for nine EECCA countries. Turkmenistan is excluded due to lack of data.

← 3. OECD Green Growth Studies, Green Growth Indicators 2017.