The chapter demonstrates differences in the structure and supply of social services among Spanish Autonomous Communities. First, it deals with the structure of service provision in territorial and functional terms. Secondly, it presents the regulatory and real ratios of social services professionals to the population. Finally, it presents the eligibility and co-payment criteria for social services.

Modernising Social Services in Spain

4. There are differences in actual access to social services across Spain

Abstract

4.1. Differences in the set-up of services and in territorial organisation

Regional laws define the structure of social services systems from two perspectives: territorial and operational. From the territorial perspective, decentralisation is the basic principle for the provision of services in almost all cases, aiming to bring them into proximity with users. The principle of proximity is also reflected in the systems’ operational structure, which has two levels of care: basic or primary care, and specific care. The first level – classified in the different laws as community, basic or primary care social services – is the people’s first point of contact with social services and includes services for the entire population that do not distinguish between specific groups with particular needs. These services include information, social promotion and guidance, home care and support in social emergencies. Municipalities or local authorities have traditionally provided these services to meet the most basic social needs of the population. The second level of services is provided at regional level and comprises services involving specialised care and services that respond to the specific needs of certain groups (such as older people, people with disabilities) and are classified according to subjective criteria.

4.1.1. Regulatory differences in the organisation of social services

Table 4.1 summarises the main aspects of the geographic arrangement and the levels of care as established in regional laws. In most autonomous communities, services are organised in two levels (referred to here as primary care and specialised care), with primary care generally being provided and managed locally (in the basic zone or municipality) and specialised care being managed regionally and provided at a higher territorial level (i.e. in a larger territorial unit); however, the modes of organisation are diverse. In some communities (Community of Madrid, Murcia, Galicia), there is no formal geographic arrangement for social services, but even in these cases, the general rule is that basic services tend to be provided and managed in close proximity to users, i.e. by municipalities.

The zoning varies among the autonomous communities: Galicia has one level; most communities have two, but several have three (Asturias, the Balearic Islands, Extremadura and Valencia), four (Madrid) and even five levels (the Basque Country). Moreover, population criteria are very diverse, with some autonomous communities giving great importance to certain isolated municipalities or towns.

It is also worth mentioning the important taxonomic differences, which make it more difficult to establish a unified or harmonised overview of these structures. For example, Andalusia and Aragon structure their territory in two levels. In Andalusia, the smallest territorial unit is called a “basic zone” and the largest is called an “area”, while in Aragon, the smallest territorial unit is called a “basic area” and the largest is called a “sector”. Such differences also appear in the terms used to describe the operational structure: the first (or geographically closest) level of care may be called “basic care”, “primary care”, “and general care level” or “community service”. A variety of terms are also used for the second level of care (or specialised services).

Each autonomous community established a territorial and operational structure that differs from the others in a number of details, although they all obey common principles. In the vast majority of cases, these differences are due to historical reasons (sometimes the territorial organisation has elements that are very old), to the needs of each territory, to interactions with other services – particularly health services, which have their own deeply embedded geographical and operational structure – or to the management capacity of local entities.

Table 4.1. Geographic arrangement and operational structure of social services

|

Region |

Territorial units |

Operational structure |

|

Andalusia |

2 levels: – basic zones – areas |

2 levels of care: – primary level of social services (provided at the basic-zone level, managed by the municipality) – specialised level of social services (provided at the area level, managed by the autonomous community) |

|

Aragon |

2 levels: – basic areas (51) – sectors (3) |

2 levels of care: – general social services (provided at the area level, managed by the municipality) – specialised social services |

|

Asturias |

3 levels + special zones – basic zones – districts – areas (8) |

2 levels of care: – general social services (provided at the basic-zone level, managed by the municipality) – specialised social services (provided at the area level, managed by the autonomous community) |

|

Balearic Islands |

3 levels – basic zones – areas – islands |

2 levels of care: – community services * basic (at the basic-zone level, managed by the municipality) * specific (provided at the area and island level) – specialised services (provided at the area level, managed at the island and autonomous community level) |

|

Canary Islands |

No map available - municipalities - town councils |

2 levels of care: – primary care and community social services – specialised social services |

|

Cantabria |

2 levels: – basic zones (22) – areas (4) |

2 levels of care: – basic services (provided at the basic-zone level, managed by the municipality) – specialised services (provided at the area level, managed by the autonomous community) |

|

Castile‑La Mancha |

2 levels: – zones – areas |

2 levels of care: – primary care (provided at the zone level, managed by the municipality) – specialised care (provided at the area level, managed by the autonomous community) |

|

Castile‑León |

2 levels + zones with specific needs – social action zones – social action areas |

2 levels of care + other structures – first level or basic action (provided at the zone level, managed by the municipality) – second level or specialised (provided at the zone level, managed by the autonomous community) |

|

Catalonia |

1 level: – basic areas |

2 levels of care: – basic social services (provided and managed at the municipal level) – specialised services (provided at the supra-municipal level) |

|

Extremadura |

3 levels: – basic units – basic zones – areas |

2 levels of care: – basic social care (provided at the basic-unit level, managed by the municipality) – specialised care (provided at the zone level, managed at the area level) |

|

Galicia |

municipalities and associations of municipalities (61 entities) |

2 levels of care: – community services (provided and managed at the municipal level), divided into * basic * specific – specialised services (under regional jurisdiction) |

|

La Rioja |

2 levels: – basic zones – territories |

2 levels of care: – first level (provided at the basic-zone level, managed by the municipality) – second level (provided and managed at the regional level) |

|

Community of Madrid |

No definition available in a regulatory text 4 levels: – basic zone – territory – district – area |

2 levels of care: – primary care (provided at the basic-zone level, managed by the municipality) – specialised care (no information found) |

|

Murcia |

No clearly defined arrangement municipalities and associations of municipalities |

2 levels of care: – primary care (municipal provision and management) – specialised care (regional provision and management) |

|

Navarre |

2 levels: – basic zones (44) – areas |

2 levels of care: – primary (provision at the basic-zone level and managed by the municipality), divided into * basic social services (municipal) * specific structures (regional management) – specialised services (regional scope, regional management) |

|

Valencia |

3 levels: – basic zones – areas – departments |

2 levels of care: – primary (managed by the municipality), divided into * basic social services (basic zones) * specific structures (areas) – secondary (departments) |

|

Basque Country |

5 groups: – maximum proximity services – high proximity services – low proximity services – medium proximity services – centralised services |

2 levels of care: – primary care (local and managed by the municipality) – secondary (managed at the level of the province or the autonomous community) |

Note: Territorial units are listed from the smallest to the largest. Levels of care do not always correspond to a single territorial unit; the table shows the most frequent or representative case. The nomenclature used in the regional regulatory texts has been respected.

Source: OECD questionnaires, regional social services laws and social services maps.

This structuring of social services can result in a fragmentation of the network and a lack of continuous or integrated care, as highlighted by several studies. The operational structure compartmentalises services, separating primary and community care services from specialised services, and thus hindering the provision of integrated solutions focused on personal trajectories. This suggests that organisational change is needed (Fresno, 2018[1]) However, in several autonomous communities this need for integrated solutions is partly met by primary care that comprises both basic and specialised care. Navarre, for example, emphasises the importance of a vertically integrated public social services system and of response models that propose “care packages” with sectoral itineraries. Navarre’s strategic plan foresees social services centres providing technical support to basic social services and care becoming more efficient (Gobierno de Navarra, 2019[2]). Cantabria meanwhile highlights the lack of a sufficient operational and strategic leadership structure above the basic zone level (Hendrickson, 2019[3]). Similarly, Catalonia’s new strategic plan envisages implementing co‑ordination mechanisms between services and the use of shared assessment instruments and protocols.

4.1.2. Varying numbers of facilities due to differences in regional planning

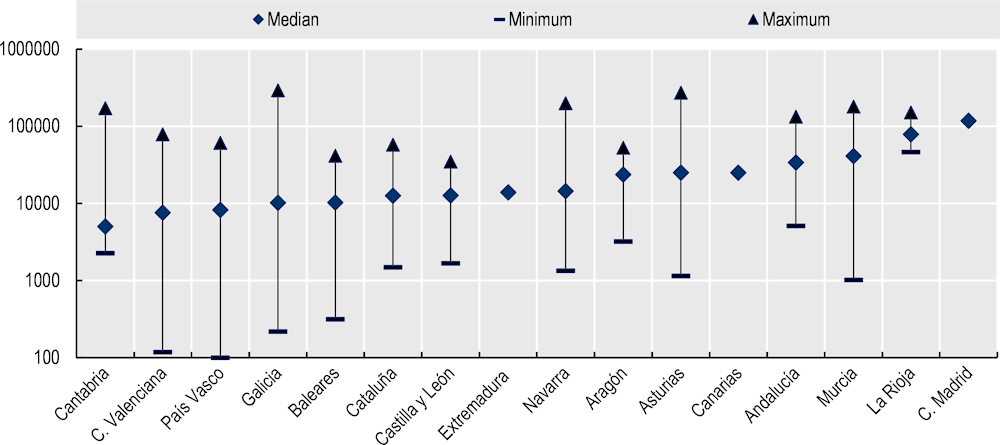

Social services centres offer information and guidance to help individuals and families address problems. They initiate procedures to apply for assistance and services in the catalogue or to obtain the certificate of entitlement. These centres exist throughout Spain and have close links with the local population. For potential users, they are almost always the gateway to the regional or municipal social services network. In general, people are assigned to the centre closest to their place of residence. Figure 4.1 illustrates the enormous differences in potential user numbers among the social services centres. These data are for 2018 and have remained stable over the last decade. The regional average for number of residents in a geographical area covered by a social services centre ranges from 5 045 in Cantabria to 118 312 (approximately 20 times more) in the Community of Madrid. Numbers also vary widely within the autonomous communities. For example, in Valencia, the smallest centre (in terms of potential users) serves an area with only 118 inhabitants, while the largest, located in a densely populated urban area, serves more than 79 000. The number of inhabitants per centre depends on several factors:

Population density. In areas with a high incidence of rural population (such as Galicia or Cantabria) the average number of inhabitants per social services centre is lower.

Demand for social services. In poorer areas or areas with an older population, the effective number of users will be higher than in areas with a large but younger population.

The size of the social services centres. In areas with a larger population and higher demand, centres tend to be bigger and employ more professionals.

Figure 4.1. Social services centres serve highly variable population areas

Note: Castile‑La Mancha is not included due to lack of data. In the Canary Islands, an approximate estimate has been used for the average. Logarithmic scale.

Source: 2021 OECD Social Services Questionnaire.

Even when these factors are taken into account, inter- and intra-regional differences in the number of potential users of the centres are extremely high. This suggests that some centres are undersized and cannot meet the needs of the population,1 especially when demand spikes, for example in an economic or health crisis.

4.2. Differences in human resources for the provision of services

4.2.1. Regulatory ratios

The term “regulatory ratios” refer to the number of professionals who provide some service over the number of potential or actual users of the service. These proportions or ratios can be regulated (or not) by relevant authorities; for example, in the areas of health services and public employment services it is common that professionals/users ratios (or at least the minimum acceptable ratio) are regulated. In the area of social services, eight autonomous communities have not established minimum staffing levels. In those that have, the minimum ratios range from 1 500 inhabitants per professional to 4 000 inhabitants per professional. Table 4.1 shows minimum ratios of primary care professionals (including administrative staff) per inhabitant established in the respective regional regulations.2 All the overall ratios, except for La Rioja’s, are close to the median of one worker per 2 616 inhabitants. Aragon, Navarre, Galicia and Valencia are the only autonomous communities to differentiate ratios according to population criteria.

In general, minimum ratios of professionals decrease as the population increases. While ratios are better than the median in small towns, in large localities, the population density is much higher and consequently the number of inhabitants per professional is higher.

Table 4.1. Statutory minimum ratios for primary care professionals

|

|

|

Approximate ratios, in inhabitants per professional (4) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Region |

Regulatory status (1) |

Overall |

Small localities(2) (<5 000) |

Medium localities (5 000‑20 000) |

Large localities (>20 000) |

|

Andalusia |

0 – No explicit regulation |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Aragon |

1 – Strictly demographic criteria |

1 848 |

1 667 |

1 640 |

2 235 |

|

Asturias |

1 – Strictly demographic criteria |

.. (3) |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Balearic Islands |

1 – Strictly demographic criteria |

2 307 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Canary Islands |

0 – No explicit regulation |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Cantabria |

0 – No explicit regulation |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Castile‑La Mancha |

0 – No explicit regulation |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Castile‑León |

0 – No explicit regulation |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Catalonia |

1 – Strictly demographic criteria |

3 000 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Extremadura |

1 – Strictly demographic criteria |

3 000 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Galicia |

2 – Linked to regional planning |

2 931 |

2 857 |

2 907 |

3 000 |

|

La Rioja |

2 – Linked to regional planning |

4 000 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Community of Madrid |

0 – No explicit regulation |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Murcia |

0 – No explicit regulation |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Navarre |

1 – Strictly demographic criteria |

1 584 |

1 111 |

1 405 |

2 236 |

|

Valencia |

1 – Strictly demographic criteria |

2 187 |

2 500 |

1 625 |

2 437 |

|

Basque Country |

None found |

|

|

|

|

Notes: Approximate ratios calculated using current regulations. Some autonomous communities (for example, Galicia or Navarre) have established differentiated ratios according to the population of the local entity and the type of territory. In these cases, the table also indicates an approximation of these differentiated ratios. (1) For ease of reading, the numbers of inhabitants per professional are grouped into three categories: above the national median (orange), around the median (yellow) and below the median (green). (2) Municipality, county or other local entity defined in the territorial planning. (3) Asturian regulations only indicate the minimum number of workers per social work unit. (4) Includes social workers, educators, psychologists and administrative assistants. (5) The Basque Country does not establish specific ratios in its regulations, but states that an adequate ratio is between 2 000 and 3 000 inhabitants per professional.

Source: OECD questionnaires and regional legislation.

The table on staffing ratios established in the regulations is complemented by professionals/inhabitants ratios actually observed. Table 4.2 shows estimates made based on 2018 data on staff working in primary care services and number of inhabitants in each autonomous community.3

Between 2012 and 2018, all autonomous communities showed an improvement in their primary care staffing ratios. For example, in Andalusia, the average fell from 3 605 inhabitants per professional in 2012 to 3 294 inhabitants per professional in 2018. In the Community of Madrid (excluding the City of Madrid), the average fell from 6 426 inhabitants per professional in 2012 to 5 770 inhabitants per professional in 2018. Taking a weighted average over the autonomous communities who reported this information for each year, the ratio decreases from 2 889 inhabitants per professional in 2012 to 2 132 inhabitants per professional in 2018.

Although it is not possible to attempt a direct and detailed comparison between the minimum ratios established by the regulations and the ratios observed, in many regions the difference between them is relatively low. Although the ratios observed in Aragon and Valencia in 2018 are not close to the minimum ratio established in their respective regional regulations, they are close to their median regulatory ratios. This is because the overall regulatory ratio corresponds to the average of several ratios set according to the type of territory and demographics, resulting in a relatively low overall minimum ratio.

Disparities between the regions persist, although they are smaller than a decade ago. Some autonomous communities have ratios below the minimums established in their regional regulations, where they exist, and/or below the median ratio calculated from all existing regulations. For example, despite the aforementioned improvement in the ratio observed in the Community of Madrid, it remains below the median ratio of 1 worker per 2 619 inhabitants, due to the region’s very high population density. Similarly, in 2018, Extremadura had an overall ratio of 1 primary care worker per 3 764 inhabitants, which is lower than the minimum ratio established in its regulations and more than 30% lower than the median ratio. Conversely, in 2018 Castile‑León, Catalonia and Murcia had ratios well above the median, with 1 worker per 1 622, 1 681 and 1 236 inhabitants, respectively.

Table 4.2. Observed ratios for primary care professionals

|

Region |

Inhabitants |

Primary care staff (1) |

Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Andalusia |

8 408 980 |

2 553 |

3 294 |

|

Aragon |

1 308 728 |

588 |

2 226 |

|

Asturias |

1 028 244 |

406 |

2 533 |

|

Balearic Islands |

1 166 920 |

1 635 |

714 |

|

Canary Islands |

2 177 050 |

1 833 |

1 188 |

|

Cantabria |

580 229 |

1 302 |

446 |

|

Castile‑León |

2 409 164 |

1 485 |

1 622 |

|

Catalonia |

7 600 065 |

4 521 |

1 681 |

|

Extremadura |

1 072 863 |

285 |

3 764 |

|

Galicia |

2 701 743 |

1 519 |

1 779 |

|

La Rioja |

312 884 |

121 |

2 586 |

|

Community of Madrid |

6 549 520 |

2 029 |

3 228 |

|

Murcia |

1 478 509 |

1 196 |

1 236 |

|

Navarre |

647 554 |

1 567 |

413 |

|

Valencia |

4 963 703 |

1 818 |

2 730 |

Notes: Data for 2018, except Cantabria (2017) and the Community of Madrid (2019). No information was found for Castile‑La Mancha and the Basque Country. (1) To improve comparability with other autonomous communities, staff numbers have been corrected in Andalusia and Asturias (exclusion of home‑help assistants).

Source: Cantabria and Navarre: Hendrickson (2019[3]), Informe sobre la situación de la atención primaria de servicios sociales en Cantabria. Madrid: Comunidad de Madrid (2021), Estudio sobre la situación de los servicios sociales en la Comunidad de Madrid. Information for the rest of the autonomous communities comes from an analysis by the authors based on the OECD Social Services Questionnaires.

4.2.2. Composition of human resources

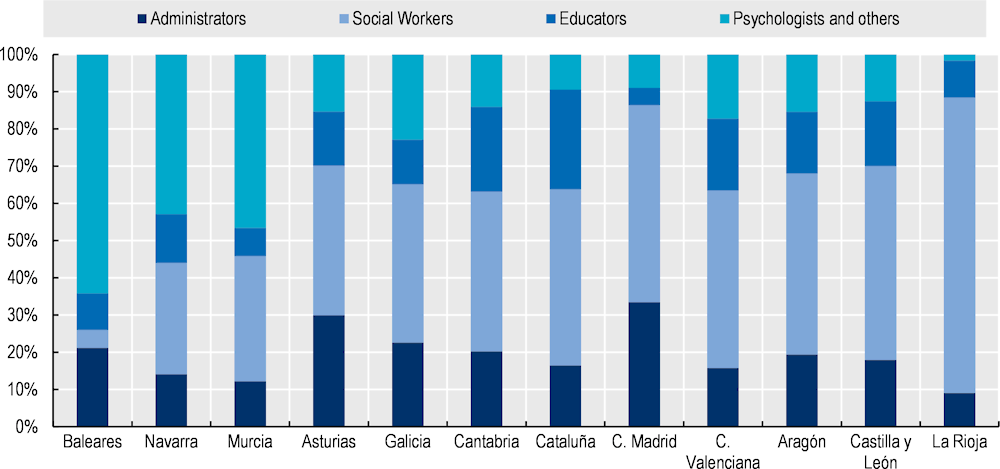

To provide users with personalised care, social services have a multidisciplinary teams with diverse professional profiles. Various studies carried out by the autonomous communities highlight the importance of human resources in social services and the lack of adequately trained personnel to respond to the needs of the population. In surveys, professionals emphasise the need for more administrative personnel and more social workers. These staff shortages force professionals to dedicate a lot of time to administrative tasks and make it difficult for them to provide social intervention and support.

Figure 4.2 shows the breakdown of the different professional profiles working in primary care. Social workers are the largest group, accounting for around 40‑50% of the staff. Administrative workers are also a large group, although with large regional variations. The percentage of educators also varies, ranging from 10‑11% in La Rioja and Galicia to more than 20% in Cantabria. There tend to be fewer psychologists; they account for around 5‑6% of workers in most regions, reaching almost 10% in Castile‑León.

Figure 4.2. Social workers represent the largest share of social services professionals

Note: Andalusia, the Canary Islands and Extremadura are not included for reasons of comparability. Castile‑La Mancha and the Basque Country are not included either as no data were found for these regions. To ensure comparability, the “psychologists” category has been merged with “other professional profiles”. The breakdown by professional category only covers staff financed by the autonomous community governments.

Source: OECD Social Services Questionnaires and Comunidad de Madrid (2021), Estudio sobre la situación de los servicios sociales en la Comunidad de Madrid.

Several studies and strategic plans highlight the need to clarify professional profiles, improve continuous staff training and offer external advice and support to professionals. The issue of training, especially in relation to changes to the role of social workers, is raised by several regional strategic plans. In surveys, social workers have suggested that the regulatory framework should be improved with regard to staff training and career progression opportunities (Ararteko, 2016[4]) Improving the regulatory framework would make it possible to adapt the supply of social workers to the reality of demand, according to whether multidisciplinary or specialised workers were needed. Improving the training offer would also create more opportunities for mobility (Hendrickson, 2019[3]). Most social workers consider that the training received is insufficient for technical and administrative staff. In this context, (Castillo de Mesa, 2017[5]) offers interesting ideas on integrating Big Data into training for social workers. As an example of improved training, in Catalonia universities are collaborating in the design of specialised postgraduate training courses and there are plans to establish mechanisms for accreditation and competency acquisition.

Staffing ratios do not correspond to the reality of demand, which can lead to overwork and sometimes burnout among professionals. In Spain, the social and health services sector has the highest rates of absenteeism, driven by sick leave and work-related illnesses (Lizano, 2015[6]). Social workers in the Basque Country emphasise that demand for social services varies in type and intensity by municipality. This variety is not accounted for in the ratios, which suggests that staff numbers and profiles are not necessarily adapted to the demand. In Asturias, although staffing ratios slightly exceed the recommended minimum, there is a widespread perception of overwork, especially in the more urban areas and basic zones, where demand is higher. In contrast, in Cantabria, social workers in rural areas (less than 10 000 inhabitants) are more likely to suffer from overwork than those in urban areas (Hendrickson, 2019[3]). Making frequent car journeys is considered a source of stress. In addition, the lack of a team co‑ordinator tends to lead to social workers (who are responsible for keeping the public informed, in addition to their interventions) passing some responsibilities on to the social educators. If each municipality or area provided an assessment of local demand, ratios could be adapted to the real demand (Ararteko, 2016[4]).

Interventions vary considerably among the autonomous communities in terms of care provided and intensity of work. In certain autonomous communities, such as Asturias, the Balearic Islands and Murcia, the average number of cases is 60 per worker per year, while in Galicia it is around 40. In contrast, in Aragon, the average is 250 per worker and in Cantabria, it is over 300. There is also great variability within the autonomous communities: workers may handle twice as many cases as a regional colleague, or four times as many. In Aragon, for example, the minimum number of cases is 77 and the maximum 373. In Extremadura, numbers can vary by a factor of 10, with caseloads ranging between 25 and 250. These case numbers are in line with those found in a study by the General Council of Social Work, which states that “42% of social work professionals have a high caseload, which hinders their ability to maintain high standards and a personal approach and compels them to focus on managing resources rather than the guidance and decision making needed to implement an appropriate intervention project” (Consejo General del Trabajo Social, 2018[7]).

There are several additional issues with the working conditions of social services personnel, including psychosocial risks and pay, especially when we consider disparities between permanent public administration staff and temporary workers. Workers’ psychosocial risks are affected by overwork and, to a lesser extent, by users’ aggressive behaviour (Ararteko, 2016[4]). Navarre’s 2011 exceptional report noted the lack of training and established procedures for workers in specialised services dealing with conflict, leading to workers having to take responsibility for managing conflict where it arises (Ararteko, 2011[8]). In several autonomous communities, lower salaries compound job instability due to temporary contracts for workers on these contracts, especially in private companies.

4.3. Inequalities in the criteria for access to services and benefits

4.3.1. Eligibility criteria

As mentioned in previous sections, the portfolio or catalogue is the instrument that defines social provision in that region (see Chapter 3, Note 3). As such, in addition to listing the benefits and services and their legal nature – both enforceable and conditional – it also includes other key specifications, such as criteria for accessing benefits, conditions for financing them, and the sectors of the population targeted by each benefit. Municipal registration and/or residency status is often a requirement to access many services and benefits.

The autonomous communities that mention the residency requirement in their regulations may use different terms. For example, regulations in Castile‑León and Extremadura establish “legal residency” in a municipality of the region as a requirement to access the RMI benefit. In La Rioja, Cantabria and Asturias, however, regulations insist on “effective” and “uninterrupted” residency, while Murcia, Catalonia, Galicia and the Community of Madrid require “effective” and “continuous” residency to qualify for this benefit (Marquez, 2018[9]). Furthermore, in many cases, a minimum length of municipal registration and/or residence in the respective autonomous community is required, which also limits people who may apply. Regulations differ in terms of the time period required, which may be unspecified or vary from a few months to several years. For example, to access the RMI payments in the Basque Country claimants must have been registered in a Basque municipality for at least three years, but when receiving the benefit, they can spend up to 90 days a year outside the region without losing their right to this benefit (although payments will stop after a month or less). To access social emergency assistance, the requirement is six months of municipal registration.

Residence requirements constitute objective difficulties for people (in general foreigners) who cannot prove residency, especially if they are in an irregular situation. For this reason, the municipal registration requirements have been relaxed in many autonomous communities (for example the Balearic Islands, the Community of Madrid, Castile‑La Mancha and the Basque Country) for certain benefits relating to situations of social emergency.

Conversely, in some cases, requirements may indirectly impede access to certain services. For example, in Galicia, financial assistance to pay electricity bills or for people at risk of eviction takes the form of subsidies and, therefore, requires that the beneficiaries have no debts with the public administration. This can complicate access because the potential beneficiaries are precisely those at risk of poverty (often indebted) and inability to access these benefits exacerbates the situation.

4.3.2. Differences in co-payment criteria for access to social services

Many services are not free of charge and are subject to co-payment (i.e. the user must pay a portion of the cost of the service). The vast majority of services subject to co-payment are the most expensive, such as residential care or home care. Although all the autonomous communities to finance social services use co-payment, there are enormous differences in the criteria that determine access to them (eligibility) and in the way in which beneficiaries’ contributions are calculated. These differences inevitably generate disparities in access to certain services between users in different regions, in terms of either eligibility or ability to meet the co-payment costs. Family mediation, residential care and home care are good examples of this situation.

In most of the autonomous communities, family mediation is subject to co-payment, except when it is provided by legal aid. Only Castile‑La Mancha, La Rioja and Valencia guarantee all their citizens free access to this service. In the other regions, the service is only free for families that meet the requirements for free legal assistance when the mediation is initiated by a judicial authority. In these cases, the family’s income must not exceed twice the minimum wage at the time the service is requested. Other criteria relevant to the economic capacity of the applicant are also taken into account, such as assets or financial burden arising from family responsibilities. Some autonomous communities, such as Aragon, also define intermediate cases where, in certain economic or social circumstances, the competent department may authorise free provision of the service. In the Canary Islands, the user’s contribution depends on his or her economic capacity, although the criteria are not specified in the family mediation law (Decree 144/2007).

Residential care (see Table 4.3) is regulated at the state level by Act 39/2006 and by extensive regional legislation. In its 2012 plenary session, the Territorial Council of the System for Autonomy and Care for Dependency launched an evaluation of the development and application of Act 39/2006. The evaluation revealed differences in the autonomous communities’ methods for determining a beneficiary’s economic capacity. In some regions, the applicant’s net worth or the total income received was not taken into consideration when calculating economic capacity. As a result, in 2012, co-payments by beneficiaries with Grade I (i.e. moderate) dependency varied from 60.6% in Castile‑León to 72.8% in Extremadura, while the national average was 55.2% (del Pozo-Rubio, Pardo-García and Escribano-Sotos, 2017[10]). Although Act 39/2006 established users’ contribution at one‑third of the cost of the service, in practice users pay more than this, with regional differences. This situation can be attributed to the decision to prioritise reducing the public debt.

Table 4.3. On average, residential care users contribute with about 40% of the costs, but there are large differences between autonomous communities

|

Region |

Criteria determining E (Eligibility) (1) and P (level of co-payment or contribution) |

Share of the reference cost |

Appears in the catalogue |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E |

C |

Statutory minimum |

Statutory maximum |

Observed mean (2) |

E |

C |

|

|

Andalusia |

Recognised dependency, with residential care specified in the Individual Care Programme (ICP) |

Income, assets, social and family situation, cost of the service |

0% |

Not available, sets aside a minimum amount for personal expenses |

33.4% (central state‑subsidised, 2019) |

No (4) |

No (4) |

|

Aragon |

Grade II or III dependency recognised, with residential care specified in the ICP; over 64 years of age or with a disability level of 33% or higher |

Income, assets, age, dependents |

0% |

90% (100% if holder of a similar benefit) – 19% of the IPREM |

42.1% (public, 2019) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Asturias |

Recognised dependency |

Income, assets, age, dependents |

0% |

100% – 25% of the IPREM |

16.8% (public, 2015) |

No |

No |

|

Balearic Islands |

Dependency recognised and specified in the ICP; over 55 years of age or with a disability |

Rent, dependents |

80% of the economic capacity if it is lower than the IPREM |

90% – 10% of the IPREM (annual) |

38.4% (public, 2019) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Canary Islands |

Not available |

Financial capacity |

Not available |

Not available |

17.6% (public, 2015) |

No |

No |

|

Cantabria |

Recognised dependency, with residential care specified in the ICP |

Income, assets, age, dependents, cost of the service |

15%, if the economic capacity is lower than the IPREM |

90% – 30% of the monthly amount of the non-contributory benefit if the economic capacity is greater than five times the IPREM |

46.1% (public, 2019) |

No |

No |

|

Castile‑La Mancha |

Recognised dependency, with residential care specified in the ICP |

Not available |

0% |

Determined by the regulations governing the benefit |

34.0% (public, 2015) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Castile‑León |

Older people in a situation of dependency or severe functional disability |

Income, assets, age, dependents |

Various criteria calculated on the basis of regional indicators |

Various criteria calculated on the basis of regional indicators |

49.7% (public, 2019) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Catalonia |

People over 64 years of age in a situation of dependency and/or social risk |

Income, assets, age, dependents, reference cost of the service |

0% |

Depends on the service |

34.4% (public, 2019) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Extremadura |

Not available |

Not available |

Not available |

Not available |

17.3% (public, 2015) |

No |

No |

|

Galicia |

Recognised dependency, with residential care specified in the ICP |

Income, assets, age, dependents, cost of the service (contribution increases with the degree of dependency) |

70% of the economic capacity if it is equal to or less than 75% of the IPREM |

90% of the economic capacity if it is greater than 284.81% of the IPREM |

35.0% (public, 2017) |

No |

No |

|

La Rioja |

Grade II or III dependency recognised, with residential care specified in the ICP; over 60 years of age (except for Grade III with neurodegenerative disease) |

Economic capacity (in some cases, including that of family members or cohabitants) |

0% |

Not available |

55.8% (public, 2019) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Community of Madrid |

Recognised Grade II or III dependency, with residential care specified in the ICP |

Income, assets, age, type of care home |

86% of the economic capacity (public care homes) or EUR 950 per month (state‑subsidised care homes) or 90% of the cost of the service |

86% of the economic capacity (public care homes) or 85% of the average subsidised price (subsidised care homes) or 90% of the cost of the service |

20.9% (public, 2019) |

No |

No |

|

Murcia |

Recognised Grade II or III dependency, with residential care specified in the ICP |

Income, assets, age, dependents |

100% of the economic capacity – 20% of the IPREM, if the economic capacity is less than the reference price increased by 20% of the IPREM (6) |

100% of the reference price, if the economic capacity is greater than the reference price increased by 20% of the IPREM |

44.6% (central state‑subsidised, 2019) |

No |

No |

|

Navarre |

Grade II or III dependency recognised, with residential care specified in the ICP (7); over 65 years of age or under 65 with cognitive impairment |

Financial capacity |

Not available |

Not available |

81.0% (public, 2019) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Valencia |

Recognised dependency, with residential care specified in the ICP |

Income, assets, social and family situation, nature and frequency of service |

0% |

The total fee may not exceed, in any case, 90% of the reference unit cost of the service, which shall be established annually in the budget law of the Regional Government |

26.3% (public, 2019) |

No |

No |

|

Basque Country |

People over 64 years of age in a situation of dependency |

Not available |

Not available |

Not available |

49.8% (public, 2019) |

Yes |

Yes |

Note: ICP stands for individual care plan. IPREM stands for Indicador Público de Renta de Efectos Múltiples [Public Multiple Effects Income Indicator]. The regulations governing user contributions are regional, except for Act 39/2006, which is statewide. (1) Benefits under the System for Autonomy and Long-term Care for Dependency are universal for all Spaniards who have resided in Spain for at least five years, including a minimum of two years immediately prior to making the application. (2) The type of establishment (public or subsidised) and the reference year are given in brackets. (4) Law specifying the minimum services exempt from co-payment. (6) The minimum amount per month for personal expenses, equivalent to 20% of the IPREM, will rise to 40% of the IPREM in June and December. (7) There is also a “supportive housing service” with different requirements.

Source: OECD Social Services Questionnaires, regional social services laws. Average observed contribution data from the Instituto de Mayores y Servicios Sociales [Institute for Older Persons and Social Services – IMSERSO].

Following the evaluation of the application of Act 39/2006, the plenary session of the Territorial Council proposed a framework regulation establishing minimum criteria for beneficiaries’ contributions to the cost of benefits. Decree 20/2012 establishes that beneficiaries’ contributions shall depend on the type and cost of the service, as well as the economic capacity of the beneficiary, determined by their assets and income. For all services, contributions are progressive and cannot exceed 90% of the reference cost. The decree sets rules for minimum contributions and for determining who may be exempt from co-payment.

The Decree 20/2012 also sets reference prices for home care: EUR 14/hour for personal care and EUR 9/hour for other home care (see Table 4.4). Various autonomous communities have used these provisions to implement criteria for assessing the economic capacity of beneficiaries. Aragon, Asturias, Cantabria and Murcia have issued regulations that use the decree’s terms. Asturias and Cantabria reduce beneficiaries’ contribution to the cost of home care since beneficiaries whose economic capacity is equal to or less than the monthly Indicador Público de Renta de Efectos Múltiples (IPREM) or Public Multiple Effects Income Indicator do not contribute to the cost of the service (see Table 4.4). However, the regions’ regulations do not fully respect the Territorial Counsel’s criteria in all cases and, furthermore, they are presented differently and use different wording to the text of the Territorial Council, contrary to principles of equality and transparency (Boletín Oficial del Estado, 2018[11]). Although in most of the autonomous communities, economic the user’s income and assets determine capacity, not all regional regulations use the terms of Decree 20/2012 to calculate these values. The IPREM is not always used, either because is just not taken into account (as in the Canary Islands and Catalonia) or because an alternative indicator is used (as in Castile‑León). In addition, some autonomous communities only partially apply the minimum levels of economic capacity specified in the decree. For example, the Balearic Islands and Valencia set beneficiaries’ maximum contribution to services in the System for Autonomy and Long-term Care for Dependency at 90%, without specifying the minimum economic capacity by type of service.

Table 4.4. The average contribution of users of home care: from 2% to 44% of the hourly cost of the service

|

Region |

Criteria determining E (Eligibility) (1) and C (level of co-payment or contribution) |

Share of the reference cost |

Rate in EUR/h/user (2019) (2) |

Appears in the catalogue (E and C) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E |

C |

Statutory minimum |

Statutory maximum |

average observed above the established price (2) |

|||

|

Andalusia |

Dependency recognised by the ICP, or home care prescribed under basic community services |

Economic capacity, defined on the basis of income, asset, age |

0% if economic capacity is lower than the IPREM |

90% if economic capacity is greater than the IPREM |

2% |

13.28 |

No (4) |

|

Aragon |

People in a situation of dependency recognised by the ICP, caregivers, or people living alone without support or with limited capacity and autonomy |

Income, assets, age, IPREM, dependents |

0% if economic capacity is equal to or less than the IPREM |

90% |

16% |

17.4 |

Yes |

|

Asturias |

Dependency (older people with reduced personal autonomy; people with disabilities; minors whose families are unable to provide adequate care) |

Income, assets, age, IPREM, dependents |

0% if economic capacity is equal to or less than the IPREM |

75% |

12% |

11.96 |

No |

|

Balearic Islands |

Dependency recognised in the ICP, or population at social risk |

Personal care hours indicator, household chores indicator |

0% if economic capacity is equal to or less than the IPREM |

65% |

26% |

16.5 |

Yes |

|

Canary Islands |

Not available |

Income, assets, age, IPREM, dependents |

EUR 20 per month |

90% |

Not available |

13 |

No |

|

Cantabria |

People in a situation of dependency |

Income, assets, age, dependents, cost of the service |

0% if economic capacity is equal to or less than the IPREM |

90% |

38% |

14.67 |

No |

|

Castile‑La Mancha |

People in a situation of dependency |

Not available |

Not available |

Not available |

24% |

12.4 |

Yes |

|

Castile‑León |

People who have requested an assessment of their degree of dependency, or have reduced personal autonomy; vulnerable minors; family groups with serious difficulties (various types) |

Income, assets, age, own indicator, dependents |

Various criteria calculated on the basis of regional indicators |

Various criteria calculated on the basis of regional indicators |

15% |

16.26 |

Yes |

|

Catalonia |

Accreditation of the situation of need or of the situation of dependency |

Income, assets, age, dependents, reference cost of the service |

Not available |

Not available |

9% |

16.25 |

Yes |

|

Extremadura |

Not available |

Not available |

Not available |

Not available |

12% |

9.04 |

No |

|

Galicia |

People in a situation of dependency |

Income, assets, age, IPREM, dependents, degree of dependency |

EUR 15 euros per month |

39.95% for Grade III dependency |

23% |

9.42 |

No |

|

La Rioja |

Grade II or III dependency recognised and specified in the ICP |

Economic capacity, size of municipality where the claimant resides |

Not available |

Not available |

24% |

14.33 |

Yes |

|

Community of Madrid |

Dependency recognised in the ICP |

Income, assets, age, IPREM, dependents, degree of dependency |

0% if economic capacity is equal to or less than the IPREM |

90% |

9% |

16.27 |

No |

|

Murcia |

People in a situation of dependency and/or need specified in the ICP |

Income, assets, age, IPREM, dependents |

0% if economic capacity is equal to or less than the IPREM |

90% |

44% |

10.86 |

No |

|

Navarre |

People in a situation of dependency |

Nature and frequency of service, income and assets, social and family status |

0% |

90% |

27% |

15.08 |

Yes |

|

Valencia |

Dependency recognised and specified in the ICP |

Nature and frequency of the service, income and assets, social and family status |

Not available |

90% |

Not available |

14 |

No |

|

Basque Country (8) |

Persons in a situation or at risk of dependency |

Economic capacity, income, assets (7) |

Not available |

Not available |

29% |

14.22 |

Yes |

Note: ICP stands for individual care plan. The regulations governing user contributions are regional, except for Act 39/2006, which is statewide. (1) Universal for Spaniards who have resided in Spain for at least five years, including a minimum of two years immediately prior to making the application, there are exemptions at the state level. (2) The type of establishment (public or subsidised) and the reference year are given in brackets. (4) Law specifying the minimum services exempt from co-payment (7) The Provincial Council of Álava has a decree regulating participation and economic capacity. (8) Corresponds to an average. Álava: 88.1%; Biscay: information not available; Gipuzkoa: 16.7%

Source: OECD questionnaires, regional social services legislation. IMSERSO for average observed participation.

References

[4] Ararteko (2016), La situación de los servicios sociales municipales en la Comunidad Autónoma de Euskadi. Situación actual y propuestas de mejora.

[8] Ararteko (2011), Infancias Vulnerables - Informe extraordinario de la Institución del Ararteko al Parlamento Vasco.

[11] Boletín Oficial del Estado (2018), BOE-A-2018-135, https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2018/01/04/pdfs/BOE-A-2018-135.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2021).

[5] Castillo de Mesa, J. (2017), “El trabajo social ante el reto de la transformación digital. Big data y redes sociales para la investigación e intervención social”, Comunitania Revista Internacional de Trabajo Social y Ciencias Sociales, https://doi.org/10.5944/comunitania.15.17.

[7] Consejo General del Trabajo Social (2018), III Informe sobre los servicios sociales en España.

[10] del Pozo-Rubio, R., I. Pardo-García and F. Escribano-Sotos (2017), “El copago de dependencia en España a partir de la reforma estructural de 2012”, Gaceta Sanitaria, Vol. 31/1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.09.003.

[1] Fresno, J. (2018), Algunas prioridades para los servicios sociales en España.

[2] Gobierno de Navarra (2019), Plan estrategico de los servicios sociales de Navarra, 2019-2030.

[3] Hendrickson, M. (2019), Informe sobre la situación de la atención primaria de servicios sociales en Cantabria.

[6] Lizano, E. (2015), “Examining the Impact of Job Burnout on the Health and Well-Being of Human Service Workers: A Systematic Review and Synthesis”, HUman Service Organization Managment, pp. 39(3):167–181, https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2015.1014122.

[9] Marquez, A. (2018), “Requisitos comunes apra el acceso a las prestaciones economicas de garantía de ingresos”, Temas Laborales, Vol. 143, pp. 87-123.

Notes

← 1. Several autonomous communities informally confirmed the reality of this situation during the interviews conducted by the OECD.

← 2. When the regulations establish a single overall ratio, this value has been indicated. Where minimum staffing levels are linked to population ranges and/or territorial organisation criteria, approximate averages have been established according to three types of geographic unit: small (less than 5 000 inhabitants), medium (between 5 000 and 20 000 inhabitants) and large (more than 20 000 inhabitants). To establish these averages, we have calculated the average population in the corresponding ranges (i.e. without taking into account the actual population of the geographic units, which we do not know) for each type of geographic unit and the average of the minimum team of professionals established in the regulations, without differentiating administrative personnel from social workers, educators or psychologists.

← 3. The ratios given here are approximate. This is for several methodological reasons: (i) the number of professionals working in primary care reported in the questionnaires may refer to slightly different perimeters; this may derive, among other things, from the geographical and operational arrangement of each autonomous community; (ii) the number of professionals is not corrected for possible cases of part-time work, which may be more frequent in certain autonomous communities than others; and (iii) when the data in the regulations clearly did not correspond to the total number of professionals working in primary care, they were corrected using alternative sources.