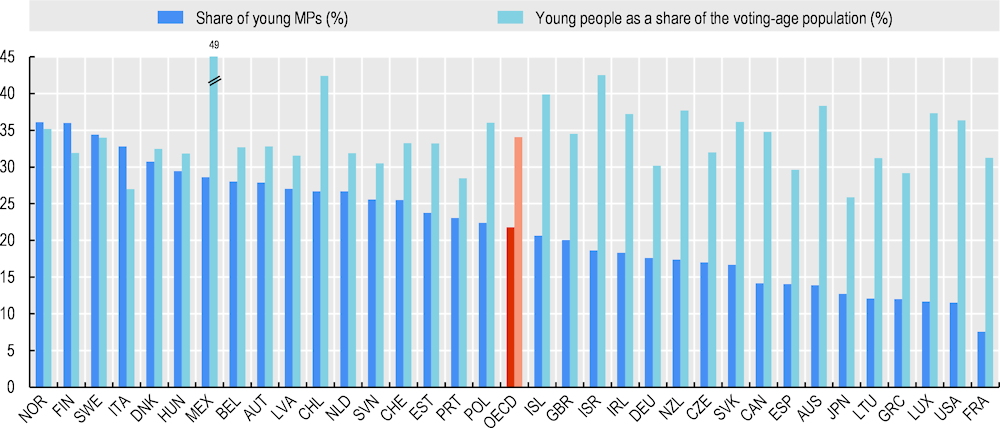

In a context of low levels of trust in government and dissociation of some groups of citizens from traditional democratic institutions, citizens are expecting public administrations to be more representative of their interests and needs. This chapter discusses how governments can respond through more inclusive public participation, including by protecting civic space, ensuring the integrity of the electoral process, averting undue influence in public-decision making, and promoting inclusive and well-governed stakeholder participation in rule making. It also looks at participatory policy making and service design and delivery, developing people’s capacities to participate in public decision making, and strengthening people-centred justice for greater participation and trust. The second section focuses on strengthening democratic representation, including making elected bodies and executives more representative of the population; fostering a diverse, representative, and responsive civil service; and delivering on the promise of representation.

Building Trust and Reinforcing Democracy

2. Upgrading participation, representation and openness in public life

Abstract

2.1. Introduction

In a context of low levels of trust in government and dissociation of some groups of citizens from traditional democratic institutions, citizens are expecting public administrations to be more representative of their interests and needs, and to actively engage with them as partners. As we look towards the looming environmental emergency, the effects of the pandemic, and the threats coming from recent global challenges, the difficult decisions to transform our societies and economies require constructive public debates and engagement that yield buy-in from all citizens and stakeholders on urgent and sometimes difficult reforms.

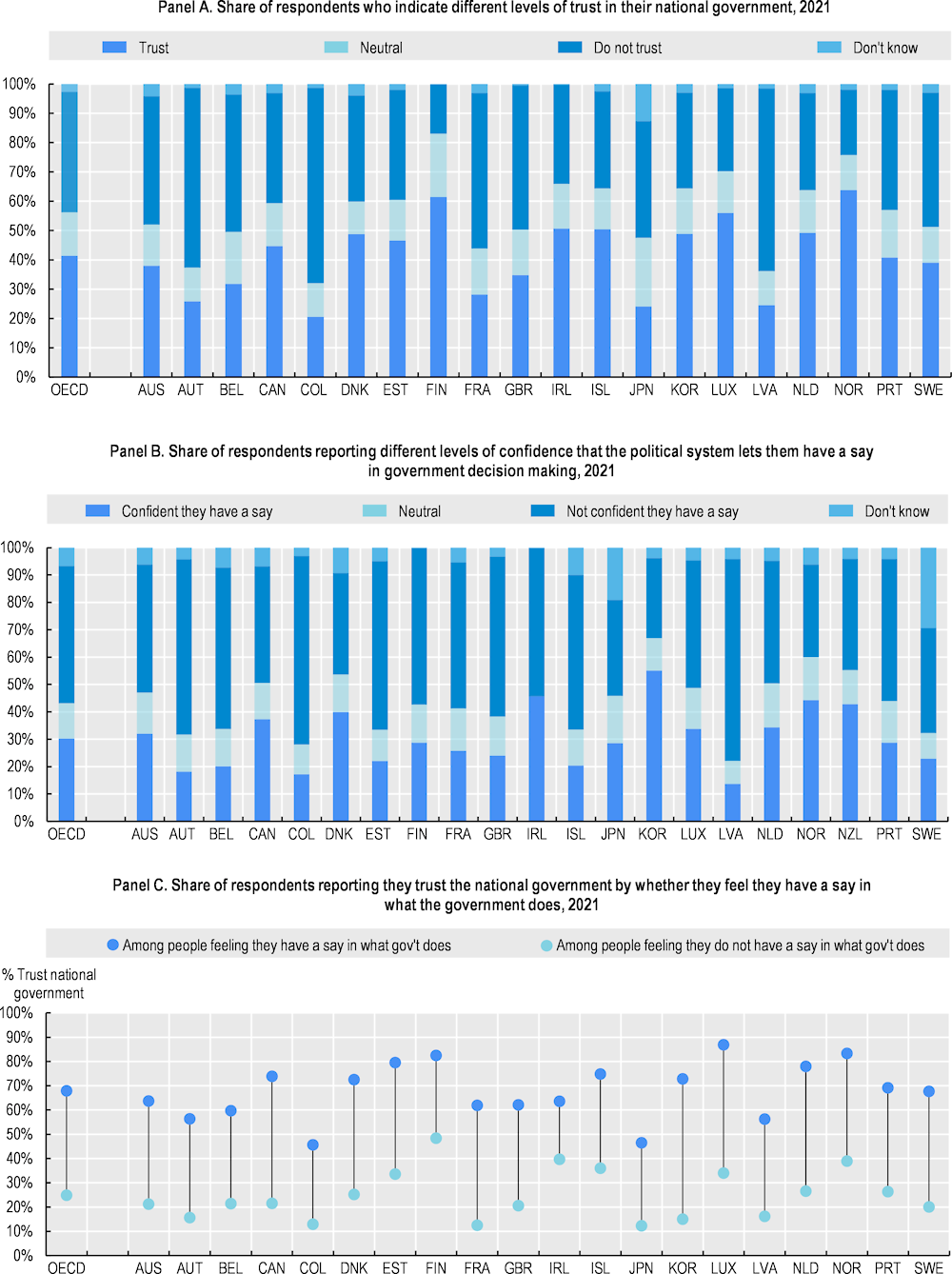

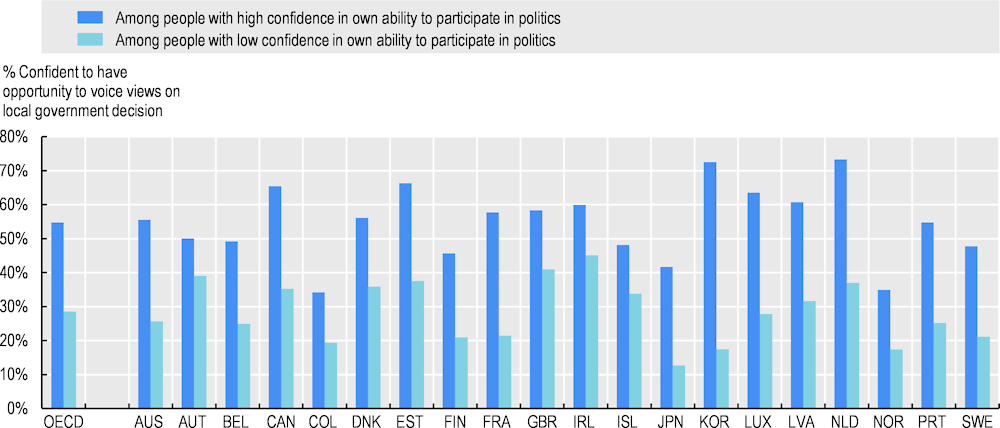

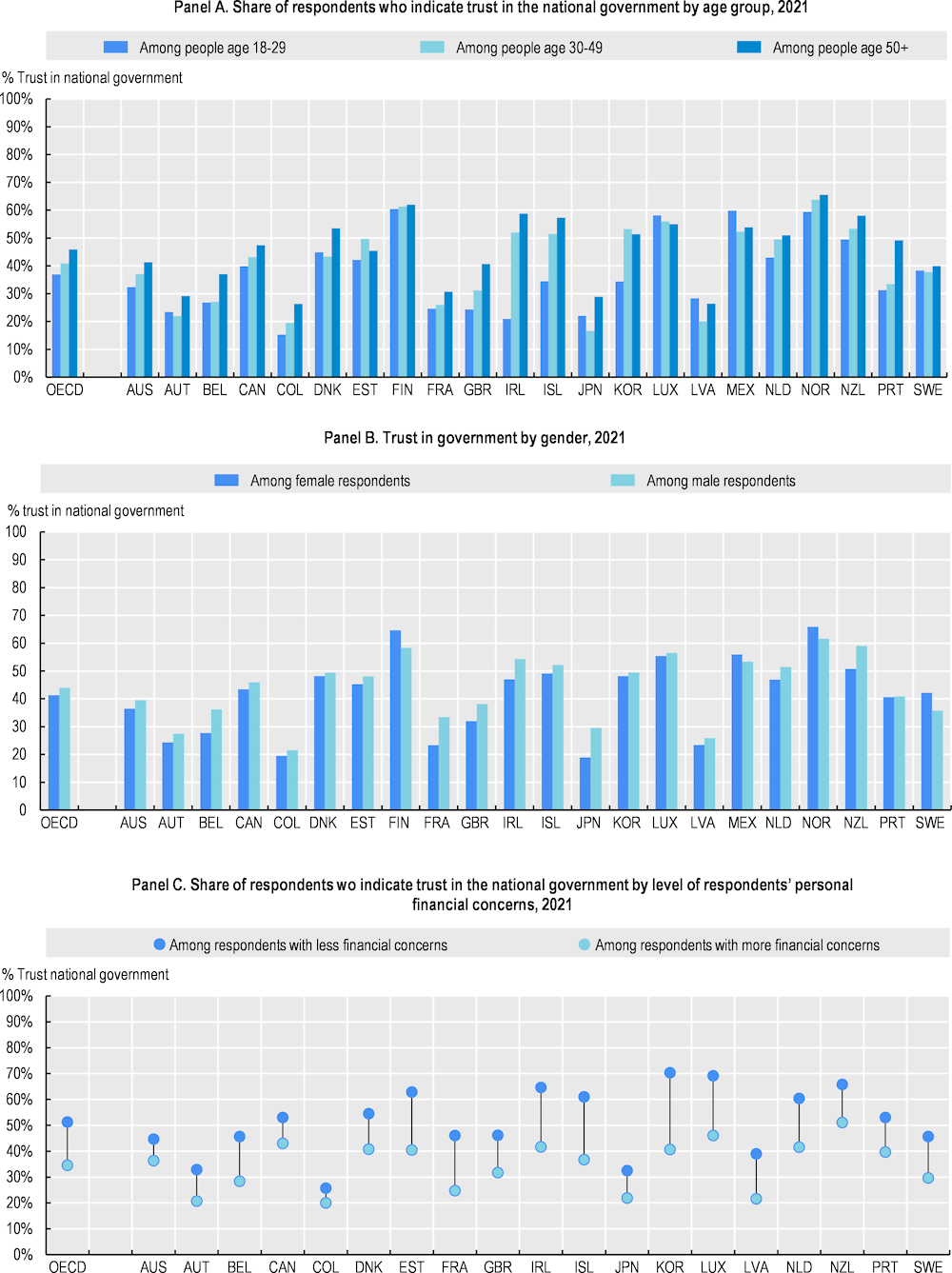

As countries fought to emerge from the largest health, economic and social crisis in decades, trust levels decreased in 2021 but remained slightly higher than in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis (OECD, 2021[1]). The inaugural OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions (“OECD Trust Survey”) finds that public confidence is evenly split between people who say they trust their national government and those who do not. The Survey shows that it takes a long time to rebuild trust when it is diminished; it took about a decade for trust to recover from the 2008 crisis. It also finds a widespread sense of lack of opportunities for citizens to exercise effective political voice and to have meaningful engagement. Less than one-third of people (30.2%) on average across 22 OECD countries say the political system in their country lets them have a say. More than four in ten respondents (42.8%) say it is unlikely that the views shared in a public consultation would influence policy making (OECD, 2022[2]).

These trends mark an important shift and prompt a fundamental questioning of the role citizens should play in public decision-making and how public institutions, parliaments, and governments can better represent them. The question is whether in a more representative, participatory and deliberative democracy, there can be evolution in the two-way relationship between everyday people and their governments. An increased role in policy making and in service design and delivery would involve a strengthened form of democracy that would not only be “of the people, by the people, for the people”1 but also increasingly with the people. What is called for is a historical move towards a more diffused and shared conception of democratic governance, which also includes a more inclusive role for public institutions and officials tasked with ensuring that the polices and services they design and implement are more representative of society, at all levels of government.

This chapter focuses largely on the cutting-edge issues, challenges and practices that concern advanced democracies, and how participation and representation matter and are evolving beyond elections.2 It does not review the traditional pillars of representative democracy and the basic considerations underpinning free and fair elections, nor the role of Parliament, which is core to representative democratic systems. Nevertheless, separate analysis should be carried out to review the cutting-edge evolution of Parliaments in democracies and how they could further evolve to strengthen representation.

Figure 2.1. Key measures of people’s engagement and trust in government

Source: OECD (2022[2]), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

2.2. Creating opportunities for inclusive public participation

Participation allows citizens and stakeholders to influence activities and decisions of public authorities at different stages of the policy cycle. The OECD Recommendation on Open Government (OECD, 2017[3]) distinguishes among three levels of citizen and stakeholder participation, which differ according to the level of involvement: information; consultation; and engagement.3

In this chapter, participation refers to the involvement of citizens within politics and public decision making. Participation is democratic “when every individual potentially affected by a decision has an equal opportunity to affect the decision” (Warren, 2002, p. 693[4]). It includes “all the ways in which stakeholders can be involved in the policy cycle and in service design and delivery” and refers to the efforts by public institutions to hear views, perspectives, and inputs from citizens and stakeholders. It includes more traditional forms of public engagement, such as consultation, as well as newer innovative practices. Active participation in democratic processes, in policy making, and in public service design and delivery is also essential to ensure that public decisions and services align with society’s needs, desires, and preferences. It is all the more important in a context where only one in three adults believe they have a say in what government does, and that people tend to be dissatisfied with government efforts to reduce inequalities (OECD, 2017[5]).

This section begins by covering the foundations necessary for active participation and then explores key trends in electoral processes, participatory policy making, and service design and delivery. It includes protecting and promoting civic space,4 both online and offline, as well as enabling a citizenry that is informed, empowered, and has agency and efficacy, meaning that people feel they are empowered and have the opportunities to influence change. The section concludes by illustrating current innovative forms of public participation, including deliberative democracy, which is conceptualised as a new form of citizen representation rather than participation, hence bridging the two themes of this chapter. Finally, this section covers key issues such diversity and inclusion in stakeholder engagement, as well as the importance of engagement with all branches and levels of government, in line with the OECD definition of Open State (OECD, 2017[3]).

2.2.1. Promoting and protecting civic space as a precondition for participation

Ensuring a healthy civic space is a precondition for citizen participation. It is about creating the necessary environment within which people can exercise their democratic rights. The elements of healthy civic space come in many shapes and sizes in OECD countries, such as constitutions guaranteeing human rights, independent oversight mechanisms over government decisions, autonomous and independent news organisations, protection programmes for human rights defenders, portals responding to freedom of information requests, strategies supporting civil society organisations, and online fora to provide feedback on public services. Protected civic spaces are underpinned by respect for fundamental civic freedoms (e.g. freedoms of expression, association, and assembly), rule of law and non-discrimination; protected media freedoms and digital rights; an enabling environment for civil society; and opportunities to actively participate in decision making that affects people’s lives.

While legal frameworks governing civic space are generally strong in OECD countries, there are challenges related to their implementation. More than two-thirds (72%) of OECD countries almost always allowed and actively protected peaceful assemblies in 2021 except in rare cases of lawful, necessary, and proportionate limitations, according to the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute (2021[6]) while 81% of OECD countries allowed civil society organisations to organise, associate, strike, express themselves, and criticise the government without fear of official sanction or harassment in 2021. Press freedom is largely protected in OECD countries compared with other countries, but it has nonetheless worsened in recent years both under government action and that of other members of society. The proportion of OECD countries where the situation is regarded as favourable for journalism has halved in the space of six years, according to Reporters Without Borders, and there is a trend towards public vilification of journalists (OECD, forthcoming[7]).

The onset of COVID-19 has led to increased pressures on aspects of civic space, with heightened concerns about racially motivated discrimination and exclusion, in addition to surveillance and privacy. The response to COVID-19 created additional challenges on this front with some governments resorting to extraordinary tools to respond to the pandemic, including invoking emergency powers that can create tensions with democratic governance by (temporarily) restricting civil liberties and limiting the authority of local governments, without the appropriate democratic safeguards and oversight.

A complex and uneven picture appears among OECD countries. While civic space is under pressure in some, in many others where oversight institutions are strong and there is a long-standing commitment to democracy and civil liberties, it is more accurate to describe the situation as evolving with a “push and pull” between a backslide in certain areas and revival in others. For example, 46% of OECD countries have public institutions that specialise in addressing discrimination and promoting equality (OECD, forthcoming[7]), while 91% of OECD countries prohibit hate speech and have introduced a plethora of initiatives to curb the phenomenon (OECD, forthcoming[7]). Canada, Germany and the Netherlands have recently enhanced civic space by passing legislation that protects journalists and their sources from undue disclosure and surveillance measures. Nineteen OECD countries have created a specific ombudsperson for youth or children at the regional or national/federal level to protect civic space for these groups, promote their rights, and hold governments accountable. Moreover, eleven more OECD countries have created an office dedicated to children or youth within the national ombudsperson office, or included youth affairs as part of its mandate (OECD, 2018[8]).

Many governments have actively protected and promoted civic space and provided additional support to the Civil Society Organisation (CSO) sector during the pandemic. Special state subsidies were introduced in Austria, Canada, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania and Sweden. In Austria, a 2020 law established a support fund, with CSOs reporting that they were engaged and consulted with throughout the process. In Canada, special COVID-19 calls supported the efforts of ten CSOs helping citizens to think critically about the health information they found online, to identify mis- and dis-information, and limit the impact of racist and/or misleading social media posts relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. In Germany, while there was no overall national pandemic-related CSO support, initiatives were undertaken in certain regions. Ireland launched a COVID-19 Stability Fund to assist community and voluntary organisations delivering critical frontline services for disadvantaged groups. In July 2021, the members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) committed to take various steps to better ensure the respect, protection, and promotion of civic space in their work by adhering to the DAC Recommendation on Enabling Civil Society in Development Co-operation and Humanitarian Assistance (OECD, 2021[9]).

Transparency is of critical value for democracy and reinforcing civic space. Wide communication and information together with government initiatives to raise citizens' awareness can further promote and protect civic space. Various crises (ranging from financial to health-related), recurring corruption scandals, and the rise of mis- and disinformation have increased the need and demand for more timely and accurate information and data from governments and more open and transparent decision-making processes(see Chapter 1). The responses to the COVID-19 crisis have shown, for example, that many decision makers have yet to fully realise that the principles of transparency and access to information are even more important in times of crisis. Evidence shows that they concretely contribute to the design and delivery of policies and services, which are better tailored to citizens’ needs and expectations, and allow the population to monitor the proper use of public funds. Access to information and effective public communication5 are also enablers of citizens’ understanding of, and compliance with, governments’ measures and allow all interested parties to engage in an informed dialogue with public institutions on the decisions that affect their lives. Going forward, governments at all levels need to ensure that access to public information provisions are robust, implemented, enforced, monitored and promoted. Additionally, working towards more transparent, inclusive, evidence-based and responsive public communication will be needed to ensure citizens can engage in meaningful dialogue with their government (OECD, 2021[10]).

Changing demographics, tensions related to immigration, polarisation, social exclusion and discrimination all constitute challenges to inclusive citizen participation. The OECD Civic Space Scan of Finland (2021[11]) revealed that even in countries such as Finland with a strong commitment to democracy, civil society, and civic participation as well as an impressive international standing related to press freedom, rule of law and respect for civic rights, a sustained effort will be essential to maintain high standards. As in many other countries, hate crimes and hate speech hamper open debate and freedom of expression by seeking to intimidate and silence people. To counter this trend, the OECD oversaw a citizens’ panel on tackling hate speech and harassment of public figures in Finland in February 2021, which generated a wide range of recommendations for the government from a representative group of society.

2.2.2. Ensuring the integrity of the electoral process in the current context and countering foreign interference in elections

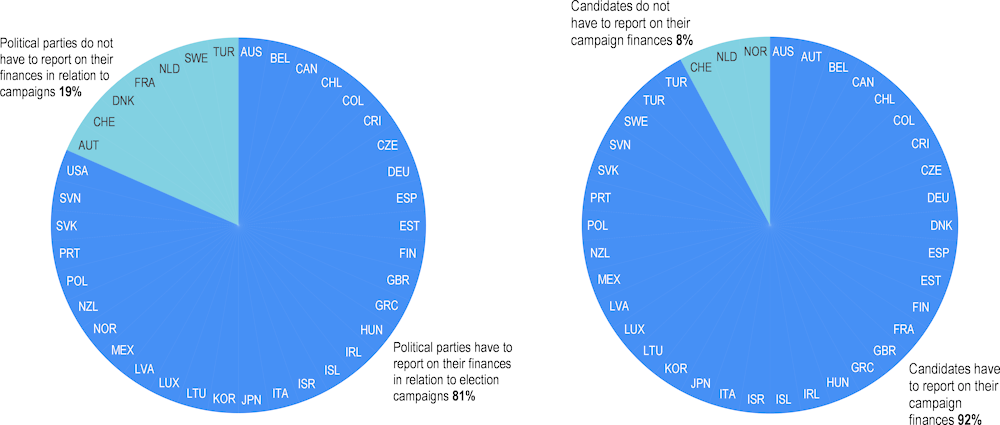

With the necessary environment and the right skills to participate, citizens should be better prepared to participate in democracy. However, a first hurdle to positive participation can be the electoral process itself. A central element of representative democratic systems is effectively protecting the right of all citizens to vote. Elections and electoral processes must also uphold the highest levels of integrity and transparency, for instance through regular financial reporting by political parties. This takes place in all but one (Switzerland) OECD countries (OECD, 2021[12]). In addition, 92% of OECD countries also require candidates to report on their campaign finances to an oversight body (Figure 2.2). In 81% of OECD countries, political parties must report on their finances in relation to election campaigns. Yet, while transparency on campaign finance is greater than on lobbying, OECD countries’ experiences have revealed that several shortcomings still exist and are vulnerable to exploitation by powerful special interests.

Figure 2.2. Separate reporting information on election campaigns by political parties and/or candidates in OECD countries

Source: Adapted from IDEA (n.d.), Political Finance Database, www.idea.int/political-finance/, in OECD (2021[12]), Lobbying in the 21st Century: Transparency, Integrity and Access, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c6d8eff8-en.

In addition to transparency, the search for the right balance and level of funding allowed from private stakeholders remains a significant matter in some countries. Upholding the integrity of electoral campaigns also requires attention to the growing, sophisticated use of data and digital platforms by political parties to influence voters. Whereas electoral campaigns naturally involve the collection of voters’ opinions and political advertising, how and the extent to which this is being done has dramatically changed, sometimes undermining applicable rules on electoral campaigns and privacy. The Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018 showed the impact of misinformation and data harvesting to target specific individuals with false information. The misuse of data illegitimately harvested from 50 million users of Facebook,6 cast doubt on the outcome of strong democratic processes such as the US 2016 elections or the UK 2016 Brexit referendum. As such, the European Union recognised in its Democracy Action Plan published in December 2020 that online platforms have made it more difficult to maintain the integrity of elections and protect the democratic process from disinformation and other manipulations.

For this reason, policy makers should consider establishing stronger safeguards for the ethical use of voters’ data, digital technologies, and digital platforms during electoral campaigns. This includes ethical standards7 and safeguards to limit the use of data and analytics for excessive psychological profiling and micro-targeting of individuals and groups, protect against the misuse and abuse of social media- and digital platforms, and improve overall transparency in digital campaigning. An example of a country that has started work in this area is the United Kingdom, where in June 2021 the central government made a statement that the upcoming Elections Bill will legislate to extend the existing in-print regime to digital campaigning material. In the development of the new provisions, the government had engaged with social media companies, political parties and the UK Electoral Commission. The European Commission is also set to introduce in 2022 a legislative proposal to enhance transparency of political advertising and communication, and the commercial activities surrounding it, so that the source and purpose of such paid-for political material are more clearly identified.

Electoral justice and effective resolution of electoral complaints are integral to the integrity and legitimacy of an election. Challenges posed by new technologies to the integrity of elections (e.g. misuse of data, disinformation, cybersecurity threats, targeting) (European Commission, 2021[13]; Garnett and James, 2020[14]), require strengthened capacities of justice systems to respond to disputes emerging during electoral campaigns or elections. Providing effective remedies to these challenges and contested electoral results requires updating legal frameworks to ensure their legitimacy. The former are indeed foundational for holding governments and contestants accountable, thus improving the quality of governance and helping counter corruption and impunity. In addition, such legal frameworks should allow political competitors to access legal redress, rather than turning to extra-legal measures or unrest (Kofi Annan Foundation, 2016[15]). Limited access to justice systems on electoral integrity may undermine citizens’ trust in electoral management and outcomes and ultimately undermine democracy. At the same time, in the era of information technology and social media, courts are playing a crucial role elaborating standards to balance electoral integrity and the rights of participation and freedom of speech (Dawood, 2021[16]).

The challenges of election integrity seem to increase when foreign political interests are involved. There are rising concerns over foreign state-led influence and the risks that such influence represents to liberal democracies (OECD, 2021[12]). Foreign political parties and governments may intentionally seek harm or influence elections for commercial, geopolitical, or personal gain, through a variety of means including technology companies, content service providers and other online intermediaries, as well as lobbying, communications and public relations firms, sometimes used in co-ordination with illicit cyber activities. Foreign interests may also use affiliations to state sponsored media services or cultural institutes as channels of influence. Given the significant risks involved when foreign governments influence domestic politics and elections, it is necessary to increase transparency concerning these activities. In addition, the provision of effective legal remedies and increased capacities, both in national and international courts, are key to protect electoral rights from foreign interference.

Some countries have adopted specific frameworks covering foreign government influence, such as the United States Foreign Agents Registration Act or the Australian Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Act (OECD, 2021[12]). Both these schemes cover political activities intended to influence government officials or the public. The UK Government announced in May 2021 the creation of a Foreign Influence Registration (FIR) Scheme to counter foreign interference and protect research in sensitive subject areas. The types of activities that are currently considered could include lobbying, the funding of political campaigning, the work of think tanks, political communications and public relations; or the acquisition of ideas, information or techniques produced by certain sensitive science and technology sectors. The European Commission also announced the development of a common framework and methodology for collecting evidence on foreign interference, as well as a toolbox for countering foreign interference and influence operations. Lastly, the French Government announced in June 2021 the creation of a national agency to combat the manipulation of information coming abroad aimed at “destabilising the state”. The objective of this new agency will be to identify and determine the origin of possible foreign digital interference targeting key democratic processes.

Foreign interference requires justice systems to provide timely responses to reduce risks and maintain public trust. Estonia’s Supreme Court adjudication within seven days (International IDEA, 2019[17]), is an example of how this can be achieved. However, the foreign dimension adds complexity, with courts encountering obstacles in collecting evidence and the consequent delay in procedures (Dawood, 2021[16]). Judicial review of reinforced campaign restrictions, limitations to donations, and the constitutional protection of the right to vote without interference (Ringhand, 2021[18]) are key to guard against the effects of foreign interference, ensure compliance and increase trust in electoral management and institutions more broadly. Both judicial training and public awareness are important elements in a context of growing foreign interference and complexity of the methods used. Finally, inter-agency collaboration and co-ordination with law enforcement are necessary to allow for early detection of disinformation and cybersecurity threats (International IDEA, 2019[17]). The global nature of these challenges calls for multilateral initiatives (Schmitt, 2021[19]), including strengthened international judicial co-operation, global awareness campaigns and reinforced international remedies. Many of these issues will be picked up in Pillar 1 of the Reinforcing Democracy Initiative (see Chapter 1).

2.2.3. Averting undue influence in public-decision making processes: promoting transparency and integrity in lobbying and other policy influence processes

Lobbying in all its forms, including advocacy and other ways of influencing governments, is a natural and normal part of the democratic process. It gives different companies and organisations access to the development of public policies and opportunities to share their expertise, legitimate needs and evidence about policy problems and how to address them. This information from a variety of interests helps policy makers understand options and trade-offs, and can ultimately lead to better policies. Yet, depending on how they are conducted, lobbying activities can lead to negative policy outcomes and greatly erode trust in government. At times, there may be monopoly of influence by those that are financially and politically powerful, at the expense of those with fewer resources and connections. Evidence has also shown that the design, implementation, execution and evaluation of public policies and regulations administered by public officials may be unduly influenced through the provision of biased or deceitful evidence or data, as well as by manipulating public opinion or by using other practices intended to manipulate the decisions of public officials (OECD, 2021[12]). Public policies that are misinformed and respond only to the needs of a special interest group result in suboptimal policies.

Evidence regularly emerges showing that the abuse of lobbying practices can result in negative policy outcomes, for example inaction on climate policies. Deceitful, misleading and non-transparent lobbying, as well as revolving-door practices that led to deregulation of high-risk activities, were also partly at the origin of the 2008 financial crisis. The COVID-19 crisis, marked by the rapid adoption of stimulus packages, often through urgent and extraordinary procedures, has exacerbated these risks. Lessons learned from previous shock events show that lobbying by powerful interests with closer connections to policy makers can lead to biased stimulus packages and responses, negatively affecting the resilience of societies and economies in the longer term.

At the OECD level, 22 countries have now adopted a tool to provide transparency over lobbying (OECD, 2021[12]). A majority of these countries have public online registries where lobbyists and/or public officials disclose information on their interactions. Eighteen countries (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, France, Germany, Ireland, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Mexico, Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) and the European Union have voluntary or mandatory public registries in place where lobbyists disclose information on their activities. An alternative, and sometimes additional approach taken, is to place the onus on the public officials who are being targeted by lobbying activities, by requiring them to disclose information on their meetings with lobbyists through “open agendas” (Lithuania, Spain, United Kingdom and the EU) and/or by requiring public officials to disclose their meetings with lobbyists to their superiors (Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia). Lastly, in addition to lobbying registers and open agendas, other countries provide transparency on lobbying by mandating ex post disclosures of how decisions were made (Iceland, Luxembourg, Poland and Latvia).

Yet, even when transparency exists, information disclosed is usually not sufficient to allow for public scrutiny. Countries that publish information through lobbying registries and open agendas disclose some information identifying who is behind lobbying activities, but not as much on which decisions and public organisations are specifically targeted, as well as how lobbying is being conducted. To ensure greater transparency over which specific interests lobbied key decision-making processes, governments can consider several policy options. First, governments with existing lobbying registers can scale up lobbying disclosure requirements to include information on the objective of lobbying activities, its beneficiaries, the targeted decisions and the types of practices used, including the use of social media as a lobbying tool. Second, another approach is to require key public officials involved in decision-making processes (e.g. ministers and cabinet members, heads of regulatory agencies) to disclose information on their meetings with lobbyists through open agendas. Lastly, governments could mandate ex post disclosures of how legislative or regulatory decision were made. The information disclosed can be a table or a document listing the identity of stakeholders met, public officials involved, the object and outcome of their meetings, as well as an assessment of how the inputs received were factored into the final decision.

In addition, today’s 21st century of information overload, with the rise of social media, has made the lobbying phenomenon more complex than ever before. The avenues by which stakeholders engage with governments encompass a wide range of practices and actors, including the increased use of information activities, grassroots mobilisation and social media to shape policy debates, inform or persuade members of the public to put pressure on policy makers and indirectly influence key democratic processes.

Lastly, lobbyists (whether in-house or as part of a lobbying association) require clear standards and guidelines that clarify the expected rules and behaviour for engaging with public officials. Where adequate governance standards are lacking within companies to address lobbying-related risks, lobbying activities can have serious reputational repercussions and raise concerns for citizens and key stakeholders such as investors and shareholders. Investors increasingly see the lack of transparency over companies’ lobbying and political engagements, and its inconsistencies with their positioning on environmental and societal issues, as an investment risk (Principles for Responsible Investment, 2018[20]). In recent years, pressure from investors and leading asset managers to better take into account corporate lobbying and political financing as a risk to the environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance of companies has had a key influence on companies’ business strategies (OECD/PRI, 2022[21]). Countries could therefore consider encouraging companies and organisations to establish standards that specify how to ensure integrity in these methods of influence. Standards could cover issues such as ensuring accuracy and plurality of views, promoting transparency in the funding of research organisations and think tanks, and managing and preventing conflicts of interest in the research process. Also, setting clear standards for companies in the provision of data and evidence could help ensure integrity in decision making. These standards could also specify voluntary disclosures that may involve social responsibility considerations regarding a company's involvement in public policy making and lobbying.

This new context calls for a more comprehensive consideration of lobbying activities, to include the whole spectrum of practices, risks and options that countries can use and have used for mitigation. The Public Governance Committee (PGC), through the Working Party of Senior Public Integrity Officials (SPIO) is in the process of revising the OECD Recommendation on Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying (OECD, 2010[22]), to reflect the evolving lobbying and influence landscape, and to guide efforts by all actors, across government, business and civil society, in reinforcing the frameworks for transparency and integrity in policy making.

2.2.4. Inclusive and well-governed stakeholder participation in rule making

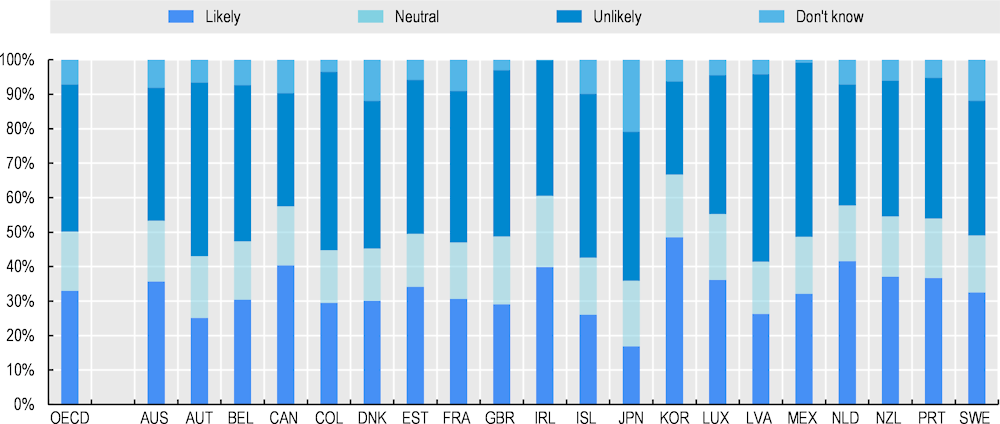

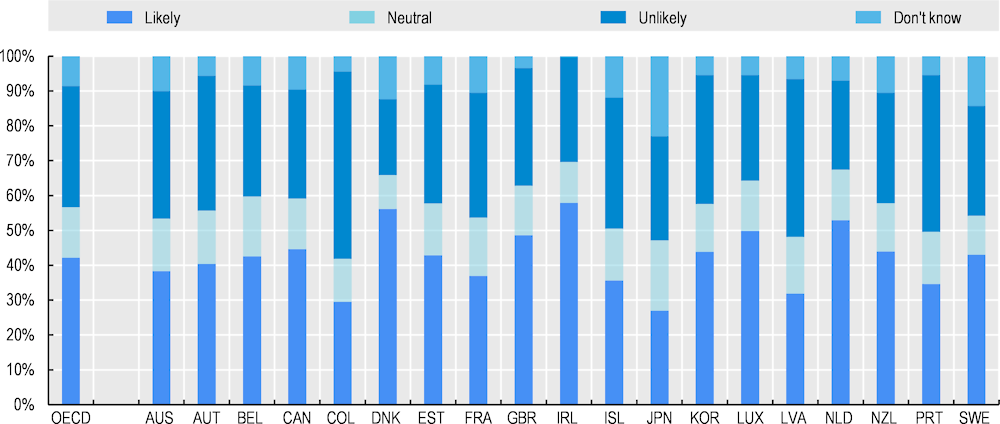

Stakeholder participation is one traditional way in which governments engage individual citizens, associations, and businesses in the policy-making process outside of the electoral cycle. It is increasingly perceived not only as fundamental for understanding stakeholders’ needs but also for improving trust in government. Analysis from the OECD Trust Survey shows that the perception of meaningful engagement opportunities and the ability to have a voice on political matters are strongly associated with levels of trust in local and national governments (OECD, 2022[2]). In addition, the Survey finds that less than a third of respondents are confident that the government would use inputs given in a public consultation (Figure 2.3). It is recognised that making decisions without stakeholder engagement may lead to confrontation, dispute, disruption, boycott, distrust and public dissatisfaction (Rowe and Frewer, 2005[23]). Formal, written, public consultation is the most common form of consultation in the policy-making process. Consultation makes preliminary analysis available for parliamentary and public scrutiny and allows additional evidence to be sought from a range of interested parties to inform the development of the policy or its implementation. Stakeholder participation across different institutions in government may take different forms. For example, legislatures traditionally hold hearings or inquiries where they can take evidence from a range of stakeholders, and individual legislators engage with citizens through constituent services. New Zealand has been exploring how to consistently lift community engagement in recent years, particularly in the areas of policy development. An example of this is the introduction of an engagement framework based on the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) guidance as part of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the terrorist attack on Christchurch masjidain on 15 March 2019. A community of practice and reporting on the use of the framework has been established to capture lessons learnt and ensure continuous improvement.

Figure 2.3. Very few think that the government would adopt views expressed in a public consultation

Note: Figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If you participate in a public consultation on reforming a major policy area (e.g. taxation, healthcare, environmental protection), how likely or unlikely do you think it is that the government would adopt the opinions expressed in the public consultation?” The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries. In Mexico, the question was formulated in a slightly different way. Finland and Norway are excluded from the figure as the data are not available. For more detailed information please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD (2022[2]), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

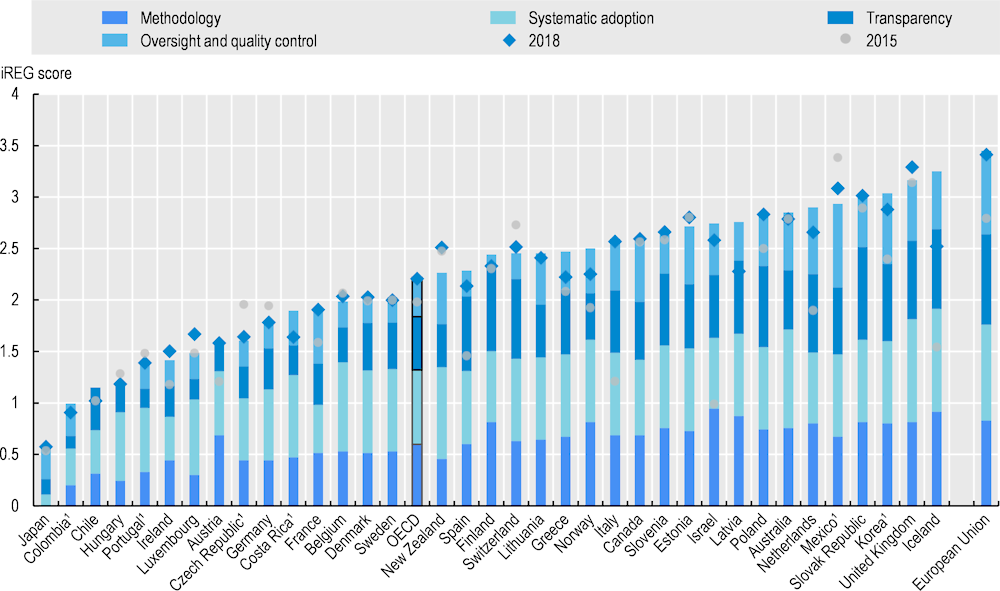

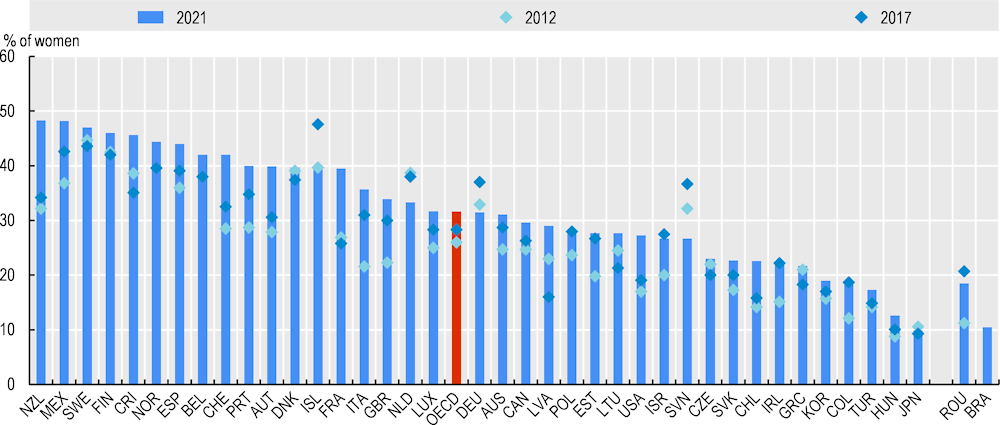

Effective stakeholder participation is also important in the making, implementing, and reviewing of rules and regulations. The central objective of regulatory policy – ensuring that regulations are designed and implemented in the public interest – can only be achieved with help from those subject to regulations (citizens, businesses, social partners, CSOs, public sector organisations, etc.). Citizens can offer valuable inputs on the feasibility and practical implications of regulations. Apart from potentially improving regulatory design, stakeholder engagement also can improve regulatory “outputs” such as improved compliance rates, desired behavioural changes in market participants, and improved trust in government. Moreover, improving regulations has the potential to strengthening economic performance by fostering a more competitive and inclusive society. The OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance (OECD, 2012[24]) calls on governments to follow principles of open government, including transparency and participation in the regulatory process to ensure that regulations serve the public interest and are informed by the legitimate needs of those interested in and affected by regulation. Still, examples where decisions are made without the involvement of those affected are still too common. The OECD Indicators of Regulatory Quality show that most OECD countries have systematically adopted stakeholder engagement practices and require that stakeholders be consulted (Figure 2.4) especially in the process of developing new regulations. However, OECD countries do not yet systematically allow for the participation of stakeholders in the development of regulations throughout the policy cycle. Most OECD countries consult with stakeholders on draft proposals, but only a few consult systematically at an early stage, a situation that has not improved in the last few years. When it comes to the decision maker’s table, centres of government play a critical role in determining the extent of stakeholder involvement (Box 2.1).

Figure 2.4. Composite indicators: Stakeholder engagement in developing primary laws, 2021

Notes: Data for 2014 are based on the 34 countries that were OECD members in 2014 and the European Union. Data for 2017 and 2021 include Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia and Lithuania. The more regulatory practices as advocated in the 2012 Recommendation a country has implemented, the higher its iREG score. The indicator only covers practices in the executive. This figure therefore excludes the United States where all primary laws are initiated by Congress.

1. In the majority of OECD countries, most primary laws are initiated by the executive, except for Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Korea, Mexico, and Portugal, where a higher share of primary laws are initiated by the legislature.

Due to a change in the political system during the survey period affecting the processes for developing laws, composite indicators for Türkiye are not available for stakeholder engagement in developing regulations and RIA for primary laws.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014, 2017 and 2021.

Box 2.1. Role of the centre of government

Electoral mandates are not only about meeting campaign and coalition agreement promises – promissory representation – but also about making complex policy choices. Centres of government (CoGs) are uniquely suited to ensure that government decision-making processes are more inclusive and representative. This was most recently demonstrated by the increase in co-ordination instances (20 out of 26, 77%), and number of stakeholders participating in co-ordination meetings called by the CoG (19 out of 26, 73%) in several OECD countries. Among the countries that increased stakeholder participation mechanisms, almost all expected to keep this change during the economic recovery (OECD, 2021[1]).

Centres of government often produce and disseminate guidance to policy makers concerning consultations and community engagement. CoGs therefore have the ability to improve the quality of these efforts and the overall inclusive nature of decision-making processes. For example, Canada’s Privy Council Office for instance offers a wide range of public engagement tools and resources which include: public engagement principles, guidance on how to analyse consultation data, activities to design engagement experiences, case studies to learn from and a community of practice (Government of Canada, 2021[25]). Likewise, as part of the Policy Project’s Policy Methods Toolbox, New Zealand’s Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet created 6 community engagement resources for policy makers (New Zealand Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2021[26]). Furthermore, the UK Cabinet Office has published a revised set of government consultation principles, which give guidance to government departments on conducting stakeholder consultations (Government of the United Kingdom - Cabinet Office, 2018[27]).

Centres of government are also responsible for ensuring items presented to cabinet are aligned with certain standards of quality, including on stakeholder consultation. In Ireland and Norway, the centre of government has issued various guidelines with standards and good practices for policy development and stakeholder consultations. Governments can take advantage of this review function to ensure the decision-making process is sufficiently inclusive: 43% of centres of government verify the item has been subject to an “adequate consultation process”, and 51% have the authority to return items to line ministries if the consultation process is inadequate (OECD, 2018[28]).

To avoid losses of trust and legitimacy, regulators need to be honest and transparent about the limits of regulation. This can be achieved through the adoption of comprehensive risk communication strategies, which clearly communicate to the affected subjects what the risks are, the probability of things going wrong and the magnitude of potential impacts (with and without government regulations). Governments also need to be aware of who will be affected by regulations and how. Any groups of stakeholders that might be disproportionately affected should be identified and consulted with. Preferably, stakeholders should be mapped already at the inception of the process, before the regulations are being drafted. This also might mean actively reaching out to those who might not have the necessary resources for getting engaged or might not be sufficiently informed on the opportunities to be consulted (OECD, 2017[29]).

Box 2.2. Ensuring participation in the development of infrastructure projects

The OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Infrastructure (OECD, 2020[30]) provides guidance on how governments can facilitate the participation of users and impacted communities during the relevant phases of the project life cycle.

It is key to ensure that all affected stakeholders and citizens have an equal chance to shape the infrastructure solutions that directly affect their lives. For example, meaningful stakeholder engagement, is a powerful platform to articulate women’s infrastructure preferences and claims (OECD, forthcoming[31]). It also provides an opportunity for women to get together to discuss their interests, interact with actors in positions of power and act collectively to seek solutions (UN Women, 2020[32]). Governments can also diversify the methods for engaging women and vulnerable populations in order to ensure more balanced stakeholder consultation processes on infrastructure questions. Equal participation of women and men in on-going community-based consultation meetings or committees, consultations with gender equality specialists, gender focus group discussions and workshops are some examples of tools that can promote a more participatory stakeholder engagement in infrastructure planning, decision making and implementation (UN Women/UNOPS, 2019[33]; OECD, forthcoming[31]).

Source: (OECD, 2017[29]; OECD, 2020[30]).

2.2.5. Taking the next step from consultation to engagement: Participatory policy making and service design and delivery

Fostering more effective and inclusive citizen participation is at the heart of the global open government movement, which has shaped the international discourse on fostering better government-citizen relations for the past decade. One of its main goals is to mainstream participation in all policy areas and at all levels of government. In close collaboration with the Open Government Partnership (Box 2.3), the OECD has been at the forefront of the global open government agenda, including through its Recommendation on Open Government (OECD, 2017[3]), which is the first and only internationally recognised legal instrument in the field. Today, 78 countries in the world that are members of the Open Government Partnership (including 75% of OECD Members) are implementing Open Government Action Plans co-created with citizens and stakeholders that have resulted in numerous innovative participatory initiatives (OGP, 2021[34]).

Box 2.3. The Open Government Partnership (OGP)

The Open Government Partnership (OGP) is an international alliance between governments and civil society to promote open government. Launched in 2011 by 8 countries, the OGP currently consists of more than 78 countries around the world, including a growing number of local governments, as well as numerous civil society organisations.

Upon joining this partnership, governments work together with civil society organisations to develop and implement two-year action plans to promote open government topics (in recent years, some countries such as Spain have started implementing their first four-year action plans). These action plans are co-created between public institutions and non-public stakeholders, such as civil society organisations, and can cover reforms (also called ‘commitments’) on any aspect of open government, including: access to information, open data, open innovation, and beneficial ownership, to name but a few. Each commitment includes concrete milestones, or intermediary outputs. In addition to a periodical self-assessment conducted by the government, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) regularly assesses the implementation of commitments contained in the action plans. In the framework of the IRM, independent researchers review the progress undertaken and their impact for openness against pre-set criteria. Typically, the whole OGP process is governed by a common body, a country’s Multistakeholder Forum.

In order to be eligible to join the OGP, a government must meet the following criteria: 1) ensure fiscal transparency through the timely publication of essential budget documents; 2) have an access-to-information law that guarantees the public’s right to information and access to government data; 3) have rules that require public disclosure of income and assets for elected and senior public officials; and 4) ensure openness to citizen participation and engagement in policy making and governance, including basic protections for civil liberties.

Source: OGP (n.d.), About Open Government Partnership, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/about/; OGP (n.d), Independent Reporting Mechanism, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/people/independent-reporting-mechanism-irm/

Proactive transparency, public consultations, increased use of referenda, as well as multiple kinds of participation initiatives have become common practice across OECD countries. For example, data from the OECD Survey on Open Government (OECD, forthcoming[35]) shows that 84% of OECD countries have a government-wide online portal to involve citizens and stakeholders, and good practices can be found across the OECD membership such as Portugal’s national participatory budget or Mexico City’s consultation to crowdsource its constitution. The increased uptake of these initiatives has strengthened democracy as they reinforce trust, build civic capacity, and bring public decisions closer in line with what people want. However, they often happen too late in the decision-making process, only reach a tiny proportion of the population concerned, or do not achieve the intended outcomes and impacts (OECD, 2018[28]). Moreover, exercises like town hall meetings, petitions, and written consultations are all susceptible to disproportionate influence by political or special interests by their design. They also tend to limit inputs to public opinion rather than public judgement.

Guidance on when, who and how to consult is therefore critical to making sure that it happens systematically and throughout the policy cycle. The OECD’s Citizen Participation Guidelines (OECD, forthcoming[36]) provide specific indications to public authorities about engaging citizens in policy making. These guidelines aid policy makers in understanding the differences in engaging citizens versus other stakeholders, the design considerations to ensure inclusiveness, as well as guidance in defining the issue, the scope for influence, the point in the decision-making process, the most appropriate methodologies and tools, as well as how to follow-up and close the feedback loop. They also include numerous examples of good practices.

Beyond these traditional consultation processes, governments and parliaments are going further to provide more and better opportunities for people to participate in public decision making in between elections. They are experimenting with new forms of open, collaborative public decision making and public service design and delivery. For example, public authorities are increasingly using civic lotteries, a tool used to convene broadly representative groups of people, based on the ancient practice of random selection (sortition), to tackle public policy challenges through citizens’ assemblies and juries (OECD, 2020[37]). Representative deliberative processes like citizens’ assemblies have numerous benefits. They broaden participation to a much wider, more diverse group of people. They guard against the outsize influence of organised interest groups and lobbies. By giving people time and resources to hear from experts and stakeholders, deliberate, and formulate collective recommendations, these processes create the conditions for everyday people to grapple with complexity and exercise public judgement. Selection by civic lottery means that the privilege of representation has been extended to a much larger and more diverse group of people than through elections alone. Members of citizens’ assemblies and juries have a mandate to act in the name of the public good, putting themselves in the shoes of others, rather than to merely give their personal point of view. These design features explain why citizens’ assemblies and other representative deliberative processes are considered as new forms of representation, as well as new forms of participation, by notable political theorists like Hélène Landemore and Mark Warren. And they have shown to be effective tools for solving complex policy problems and enhancing public trust. Recently, parliamentary committees are also increasingly involving citizens more directly in their functioning through the use of deliberative processes like citizens’ assemblies and citizens’ juries (OECD, 2021[38]).

Box 2.4. Deliberative democracy

What is deliberative democracy?

Deliberative democracy is the wider political theory that claims that political decisions should be a result of fair and reasonable discussion among citizens.

What is a representative deliberative process?

Deliberative democracy is most often implemented by initiating representative deliberative processes. These are processes in which a broadly representative body of people weighs evidence, deliberates to find common ground, and develops detailed recommendations on policy issues for public authorities. Examples of such processes include citizens’ juries and citizens’ assemblies.

Source: OECD (2020[37]), Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/339306da-en.

One notable way in which democracy has been evolving is the move towards permanent forms of deliberative democracy that create spaces for everyday people to exercise their civic rights and duties beyond voting. These permanent citizens’ councils function alongside parliament, bringing everyday people into the heart of public decisions in an ongoing way, as a complement to representative democratic institutions (OECD, 2021[38]). Rather than requiring political will to initiate an ad hoc process, these institutional changes have ensured that public participation and deliberation are part of the ‘normal’ public decision-making process. These new institutions are not a replacement, but a complement to the existing democratic architecture, making it richer and more inclusive. They improve decision making by bringing public judgement to democracy on an ongoing basis. There is not just one way to approach the question of institutionalisation, as the OECD policy paper Eight Ways to Institutionalise Deliberative Democracy (OECD, 2021[38]) highlights by explaining examples of eight different models that have been applied in different countries and at all levels of government. The OECD’s Evaluation Guidelines for Representative Deliberative Processes (OECD, 2021[39]) also have additional recommendations for how to evaluate institutionalised forms of deliberative democracy.

Box 2.5. New mechanisms for public decision making

Engaging young people

Mechanisms and channels to engage youth in policy making include affiliating advisory youth councils to government or specific ministries (as happens in 53% of OECD countries) or youth councils at national and sub-national levels (as happens in 78% and 88% of OECD countries respectively).

In Denmark, the Ministry of Environment and Food has established a Youth Climate Council advising the Ministry in the areas of climate change, environmental protection, farming and food production.

In New Zealand, the Ministry of Education has created an advisory group composed of 12 members aged 14 to 18, which are expected to inform the Ministry on the impact of activities and measures adopted within the education field as well as share their insights about education policies.

Since 2016, in France the Conseil d’orientation des politiques de Jeunesse (CoJ) brings together representatives from ministries and youth organisations to advise the Prime Minister on legislative and regulatory drafts on issues relating to youth.

Spain has also recently adopted a Youth Strategy 2022-2030, and the views of children and young people are sought in matters which impact young people's lives through the Spanish State Council for the Participation of Children and Adolescents.

Use of deliberative processes by parliamentary committees

The Scottish Parliament has commissioned multiple Citizens’ Juries since 2019: on Land Management and the Natural Environment (21 randomly selected citizens) and on Primary Care (35 randomly selected citizens took part in three panels). Recommendations that members of these representative deliberative processes developed then informed land management and the natural environment inquiry and fed into and the primary care inquiry.

In June 2019, six Select Committees of the UK House of Commons jointly called a Citizens’ Assembly on how the UK should tackle climate change (Climate Assembly UK, 2019[40]). Citizens’ Assembly took place from January to March 2020 and brought together 108 randomly selected citizens from all walks of life. The UK Government has since used the Climate Assembly’s recommendations in its report to inform its Net Zero Strategy.

In 2016-2017, the Parliament of Luxembourg initiated a deliberative poll, where 60 randomly selected citizens in six panels have deliberated over the proposed constitutional reforms. Their recommendations were presented to the Parliamentary Committee on Constitutional Review to help inform their decisions.

The “deliberative wave” is gaining momentum as more and more public authorities are turning towards deliberative democracy as a complement that strengthens representative democracy. The OECD Database of Representative and Deliberative Processes and Institutions includes 577 examples of such processes being used across OECD Member countries at all levels of government, to address complex and wide-ranging policy issues regarding climate change, infrastructure decisions, strategic and public planning, amongst others (OECD, 2020[37]). For example, Ireland’s numerous citizens’ assemblies since 2016 have provided concrete recommendations that have formed the basis for constitutional changes on same-sex marriage, abortion, divorce, and blasphemy. The assembly’s recommendations formed the basis for proposed legislative changes that informed the public’s vote in referendums on each of these issues. The Irish citizens’ assembly on climate’s recommendations were also largely adapted and referenced in the 2021 Climate Act.8

The large number of deliberative democracy examples provides a solid evidence base of how they need to be designed to be useful for policy makers and trusted by the public. The extensive analysis of these examples forms the basis of the OECD’s Good Practice Principles on Deliberative Processes (OECD, 2020[37]), which provide guidance to policy makers and practitioners for ensuring high quality, impactful, and trustworthy processes. The OECD’s Evaluation Guidelines for Representative Deliberative Processes (OECD, 2021[39]) further operationalise these principles and help ensure that high standards can be met. While it is a positive development that more and more governments are creating the conditions for everyday people to play a meaningful role in policy making, it is important that when these processes are designed and implemented, that they follow evidence-based principles of good practice to ensure they are legitimate, accountable, and trustworthy practices.

There also needs to be further consideration for how the follow-up of the recommendations from deliberative processes will happen from the very outset. Expectations need to be clear for citizens as well as for the role that legislatures and governments will play, and who holds responsibility and accountability for the response. Further analysis about how these new institutions are functioning and reflection about other permanent forms of participatory and deliberative democracy are needed. Additional future scenarios should include digital or hybrid settings for these deliberative processes, as well as the inclusion of emerging technologies to support public deliberation. Successful institutionalisation requires appropriate investment of resources, especially so that it is possible to fulfil the aspirations of equality and inclusivity. Breaking down barriers to participation also involves paying people for their time, as well as providing travel and caring expenses or services. Another main challenge is that this permanent transformation and institution building requires an accompanying shift in the mind set of policy makers and public servants about their role and their relationship with citizens. This can be facilitated by the organisation of ad hoc capacity building activities and the inclusion of these principles and practices in the curricula of national schools of public administration. As is the case with representative democracy, it will also be necessary to ensure that deliberative democracy mechanisms meet integrity and quality requirements set for other democratic institutions, including lobby regulations, conflict of interest rules and possibly other standards, as well as has mechanisms and processes in place to ensure solid discussions that prevent excessive and extreme outcomes.

The move towards new participatory mechanisms has also extended to traditional public governance tools such as budgeting, through participatory budgeting initiatives, and public procurement (Box 2.6). The former tends to be mainly at the local level – where they are arguably most effective - and to be applied to only a very limited portion of funds. Portugal, which provides a rare example of participatory budgeting at the national level, has allowed citizens to decide on specific investment proposals (initially for a total of EUR 3 million in 2017 and then for a total of EUR 5 million out of around EUR 91 billion in 2018). Still, the use of these mechanisms needs to pay attention to the potential to bypass the checks and balances provided by parliaments and the ease with which organised groups can sometimes capture these processes to serve their own interests (OECD, 2019[44]). Public procurement can be also used as a strategic policy tool to achieve stronger and more inclusive democratic governance through citizen participation. The OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement (OECD, 2015[45]) calls upon countries to foster transparent and effective stakeholder participation through inclusive and open policy-making processes and participation in public procurement processes.

Box 2.6. Citizen and stakeholder participation in the budget process and public procurement

The budget is government's most comprehensive policy document, where policy objectives are reconciled and implemented in concrete terms. It should allow citizens and their representatives to understand government priorities and provide input on policy choices, to track implementation, and to hold government to account when objectives are not being met. The parliament may engage with citizens and civil society organisations at different stages of the budget process.

A growing trend for parliaments in OECD countries to hold a pre-budget debate with citizens and civil society where they may signal budget priorities to government. Of those parliaments holding pre-budget debates, about half send the results of the pre-budget debate as a report to the government (OECD, 2019[44]).

The Canadian Parliament’s Finance Committee holds a pre-budget consultation in Ottawa as well as in different areas across the country. Any person or group is eligible to participate in the public consultation process in person or by written submission. The results of the process are published online. At the other end of the budget cycle parliaments can also involve citizens in their scrutiny of the annual report.

At the other end of the budget cycle, the Dutch Parliament’s V-100 brings together 100 participants from civil society to ask questions on ministries’ annual reports for the previous budget year. Citizens are selected by the ProDemos, Centre for Democracy and the Rule of Law. The Parliament is then able to use the work of citizens participating in V100 during the debate on Accountability Day when the Minister of Finance presents the Central Government's annual financial report to the House of Representatives.

Participation in public procurement process can take many forms. These include consultations for reforming the public procurement system including its legal framework, consultations on citizen’s needs / procurement plans, and participation in overseeing individual procurement processes (OECD, 2015[45]). A number of countries provide examples of this practice, for example, in Mexico social witnesses (testigos sociales) are required to participate in all stages of the federal public procurement procedures above certain thresholds as a way to promote public scrutiny and citizen participation. In Peru a citizen control mechanism (Monitores Ciudadanos de Control) allows citizens to visit construction sites at the beginning, during, and/or completion of public works to monitor the construction progress. Colombia’s anti-corruption mobile application “Elefantes Blancos” promotes citizen control of white elephant projects (neglected, abandoned or overbilled public works projects) allowing them to report projects and follow up on case investigations. These participation mechanisms contribute not only to ensuring the transparency and credibility of the public procurement system but also reinforcing democratic governance (OECD, 2015[45]).

Future scenarios of participatory democracy should include resilient physical and digital public spaces as core features. Many cities have built community centres that cater to youth needs, from mental health to employment counselling and advice, and provide a physical place outside home and school to congregate, for instance the Maison de la jeunesse in Paris. Similarly in Athens, the city transformed schools after hours into community spaces at the height of their refugee crisis to help connect newcomers to the city's civic and social fabric. On the digital front, beyond the numerous digital tools available to consult and engage citizens or the use of interactive technologies and digital channels such as social media, future scenarios should prioritise the development of adapted and accessible digital infrastructures that reinforce democracy. This means that as governments transform how they deliver to their citizens (e.g. increased use of data and algorithms), how they enable citizens to elect and interact with their representatives (e.g. electronic voting, virtual meetings), as well as how citizens participate in the public debate and decision making (e.g. social media, hybrid citizens’ assemblies) ensuring equal accessibility needs to remain a priority. Technological choices need to be compatible with democratic values such as inclusiveness and equality, and data and technology used in ways that are transparent, ethical and accountable. These considerations will be essential to build trust in the technology, and in the outcomes of all digital democratic processes (see Chapter 5).

Local participatory practices led by local or regional governments can effectively shape, strengthen and deepen inclusive public participation. At the local level, there is a unique opportunity to link and involve citizens, business, CSOs, and community representatives in the policy-making process in a more tangible way. This is why local governments around the world are often the leaders in innovations that aim to ensure government works better, costs less and is more responsive and accountable to local residents (OECD, 2019[46]). The UK innovation foundation, NESTA, for example, is one of the most prominent pioneers of public and social labs as a means of addressing societal challenges through evidence-based local experiments. Similarly, the Argentinean Province of Santa Fe established an innovation lab to increase citizen participation through policy co-creation. The local level is also prone to implement more innovative approaches, such as Besaya’s Citizens’ Jury on Fair and Inclusive Ecological Transition in Cantabria (Spain), or Bogota’s (Colombia) permanent Citizen Assembly for urban policies. Recognising the prominent role that local governments play in promoting participatory practices, citizen engagement and innovative and experimental not only helps better responding to citizen’s needs, but also enables building people’s trust in local government while improving integrity, efficiency and equity of local government operations (OECD, 2019[46]). Many participatory efforts have a regional dimension but the degree of citizens’ engagement and civic participation varies greatly across regions within countries. The OECD Regional Well-being indicators compare the degree of civic engagement across regions, and highlight the significant divides that exist within certain countries. While there is certainly a continuity among the principles, practices and lessons learned between all levels of governments, finding the right level of government for participation and representation to ensure that citizens are not excluded from the political process is essential.

The dynamics of citizen participation at the local level has consequences in terms of actors, processes and impacts that are worth investigating and promoting in their own right. The subnational level is closer to people, both in terms of decision making and in the provision of basic services. Hence, interactions between government and citizens are usually more direct at this level and the potential for citizens to influence and participate in public decisions is higher at the local level, with real consequences both for citizens and public authorities. Countries are integrating this reality into their open government agendas, and slowly moving towards an effective integration of other levels of government and branches of the State. For example, more than 50 local governments have joined the OGP to develop their own action plan and OECD countries like Mexico have established a co-ordination mechanism and guidelines for subnational entities to develop transparency and participatory initiatives. Colombia has been the first OECD country to develop an Open State policy that is exploiting vertical collaborations among administrations to maximise the opportunities citizens have to engage with relevant public offices seamlessly, regardless of their territorial jurisdiction. The OECD Open State framework was developed, among other things, to support members’ efforts to better integrate the promotion of participatory practices across all levels of governments (OECD, 2019[47]). The framework recognises that the local level has to be a key player in the effective construction of an Open State and proposes a specific approach to openness, designed for the subnational level.

Participatory models can also be used to empower indigenous groups and communities in decision making. In New Zealand, iwi (Māori tribes) hold certain rights and responsibilities alongside the Crown which are recognised in the Treaty of Waitangi. In recent years, New Zealand has been exploring governance models which give effect to these rights and responsibilities and distribute decision making between iwi (or other Māori groups) and the Crown. Some of these are local models, which enable a particular iwi to make decisions about land or assets that it holds customary responsibilities towards. Others are national. For example, Te Mātāwai is an independent statutory entity, made up of representatives of iwi, Māori organisations and the Crown, which leads work to protect, promote and revitalise the Māori language. The use of these models can strengthen the recognition of indigenous groups’ rights and interests and enable indigenous values and approaches to be reflected in decision making. In turn, this can enable the exploration of innovative practices, which are more tailored to communities’ needs and can achieve better outcomes.

Beyond promoting participation channels and mechanisms, actively seeking citizen’s feedback on their experience with public services can help improve service performance and delivery enhancing trust in public institutions. Citizens’ satisfaction with public services can affect not only the quality of the services, but the overall stance of citizen on the impact and quality of public institutions more broadly. For instance, the US Transportation Security Administration (TSA) put in place a programme to explore employee and customer experience relying on employee surveys and complaint data to analyse how communication from transportation security officials could help improve costumer experience. Similarly, countries such as Australia, France and Norway have set up regular surveys to gauge citizens’ satisfaction with public services (Baredes, 2022[48]).

Overall, these innovative forms of participation, from consultation to engagement and deliberation, are promising to renew governance mechanisms in established democracies by mobilising everyday people in addition to traditional stakeholders. A new balance is now to be found with traditional stakeholders that are more experienced with public decision-making processes but increasingly less representative of all segments the population, and with representative institutions, which need to upgrade and modernise to keep pace with this evolution. At the same time, new participatory mechanisms need to embed the full institutional requirements to protect integrity of decision making and allow the search for consensus through solid processes for solid outcomes. Rather than competing, as it has sometimes happened, these two parallel trends should build on each other’s strengths with the common goal of increasing the robustness of traditional and new democratic institutions.

2.2.6. Strengthening democratic fitness: Developing people’s capacities to participate in public decision making

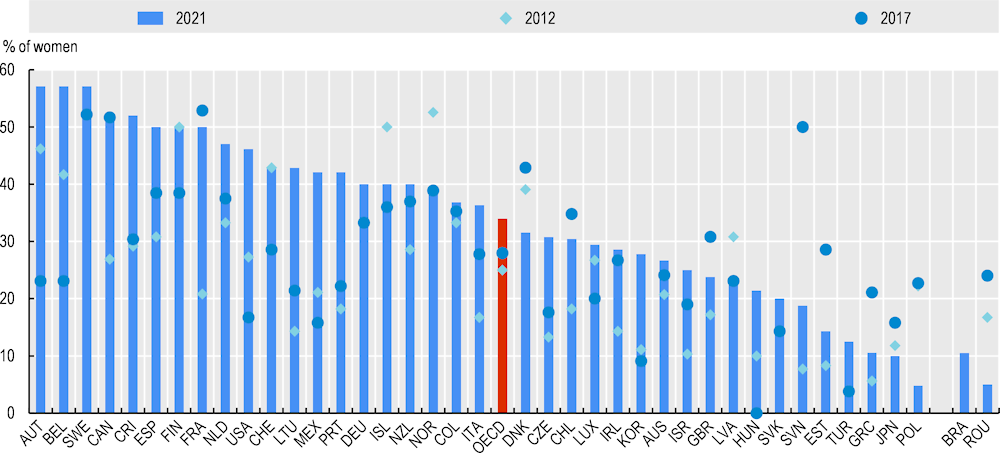

Beyond healthy institutions and processes, democracy requires people to have the right capacity and capability to actively participate in the democratic system. Research based on an analysis of 30 European countries highlights that an individuals’ self-perception of their ability to understand political processes (internal efficacy) has a positive effect on any form of participation (Prats and Meunier, 2021[49]). The OECD Trust Survey finds that peoples’ confidence in their own ability to participate in politics matters for whether they feel that they can voice views on local and national governments’ decisions (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Confidence in own ability to participate in politics matters for whether people feel like they can voice views on local government decisions

Note: Figure presents the average share of respondents who are confident to have the opportunity to voice their views on local governance issues, sorted by respondents’ level of confidence in their own ability to participate in politics. The share of respondents who are confident to have the opportunity to voice their views is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 to the question “If a decision affecting your community is to be made by the local government, how likely or unlikely do you think it is that you would have an opportunity to voice your views?”; The group of people with high confidence in their ability to participate in politics consists of responses from 6-10 to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all confident and 10 is completely confident, how confident are you in your own ability to participate in politics?”; the group with low confidence consists of responses from 0-4. In Finland and Norway the question was phrased slightly differently. Mexico is excluded from this figure as data on confidence in own ability to participate in politics are not available. New Zealand is excluded from this figure as the question was phrased substantially differently. For more detailed information please find the survey method document at (http://oe.cd/trust).

Source: OECD (2022[2]), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

Formal and non-formal civic and citizenship education in schools and through extra-curricular activities can be instrumental in this regard. A well-functioning democracy relies not only on the good institutional design, but also the knowledge, skills and engagement of its citizens. Empowering citizens to understand their rights and fully participate in their societies is an important element of the mission of schools in all OECD countries (OECD, 2017[50]). In 2016, the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) (Wolfram Schulz, 2016[51]) found that greater civic knowledge is related to pupils expected electoral participation as well as a number of other outcomes, such as students giving greater value to behaviours like obedience to the law and respect for other people’s opinions, and greater endorsement of gender equality and equal rights for ethnic and racial minorities. In addition, the study found that students’ perception of a classroom climate that is open for discussions of political and social issues and students’ experiences with engagement at school are also linked to higher civic knowledge and with students’ intention to engage in civic life in the future. These findings support the idea that school education can deliver civic outcomes by offering students the possibility of experiencing a democratic climate in a broad sense, rather than simply providing instruction on civic matters more narrowly (OECD, 2017[50]).

Social economy organisations are also key actors for strengthening society’s democratic fitness. The social economy refers to the set of associations, c-operatives, mutual organisations, foundations and social enterprises whose activity is driven by values of solidarity, the primacy of people over capital, and democratic and participative governance (OECD, 2017[50]). A range of social economy actors specifically work to increase the capabilities of vulnerable groups and disadvantaged people to participate in public life. Social enterprises, youth associations or co-operatives that enable informal workers to transition to formal labour are examples of social economy organisations that pay a specific attention to empower their members and make sure they get themselves heard in the public debate. Social economy organisations put democracy at the heart of their organisational model, most of them applying the principle “one member, one vote” in their decision-making processes. They also encourage participatory management and inclusive governance to offer a space for discussion to a wide range of stakeholders. Because of the nature of their activities and the way they operate, social economy actors are considered as “vehicles” for active citizenship and participatory democracy (Noya and Clarence, 2007[52]). They offer spaces for citizens to engage in societal projects and possibly influence the public debate, e.g. through membership or volunteering. These characteristics (internal and external democracy) make them “labs for democracy” where citizens can develop their capacities to participate in the democratic system.

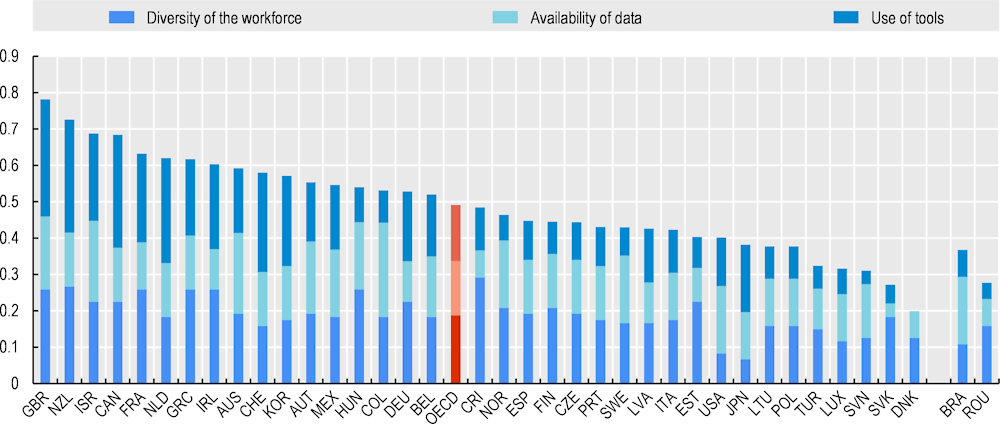

Many services that people were used to requesting, accessing, or buying in the physical world and through analogue channels have been affected by the transformation brought about by the digital age. In terms of democratic participation, the exercise of political rights has benefited from tools such as digital voting, online consultation or participation platforms, and, increasingly, digital identity tools. The Korean government, for example, launched an interactive platform, Gwanghwamoon 1st Street, where citizens can suggest policy and service ideas, generate social discussions and monitor how their suggestions have shaped public policies. In considering the opportunities and risks of digital tools on democratic participation, it is important to think about how they can support governments to be more responsive, protective and trustworthy in the way they transform the civic experience of citizens with the State (Welby, 2019[53]) and secure equal access to all. For people to truly benefit from these changing practices, they need to be equipped with the skills and tools to thrive in the digital age (OECD, 2021[54]). As more and more governments increase the use of digital technologies for democratic participation, digital skills can to some extent be considered as democratic skills, and it is important for governments and public institutions more broadly to be proactive to avoid exacerbating digital divides.