The recovery from COVID-19 represents a unique opportunity to advance towards a greener development model in LAC. Citizens in the region show a high level of concern for environmental issues, suggesting that the green transition should be at the centre of a new social contract that reconnects society and institutions. To make the green transition possible, new institutions and policies to support those that will be temporarily affected by this transition are needed. A just green transition requires mechanisms to foster inclusive dialogue across all stakeholders and to build consensus around reforms, paying particular attention to overcoming the complex political economy of such a broad reform agenda. It is equally important to ensure that public institutions can work strategically and in close co-ordination, with a coherent, long-term view of making the green agenda a centrepiece of national development strategies.

Latin American Economic Outlook 2022

Chapter 5. How to make it possible: Governing the green transition

Abstract

The green transition is an opportunity to renew the social contract in LAC (infographic)

Introduction

Moving the green transition forward is an immense task. In addition to the large financing needs associated with the green agenda (Chapter 4), green policies must be able to bring all interests on board so that the transition is possible, as well as fair, inclusive and sustainable. Taking into account the cross-cutting nature of the green agenda and the fact that it will leave winners and losers (at least temporarily), balancing the social, economic and institutional trade-offs arising from the transition and communicating them effectively is fundamental for its success. Coherent and inclusive policies are key to ensure an orderly green transition that accounts for its potential short-term challenges and costs, and supports vulnerable groups and sectors throughout the process.

This chapter analyses the institutional challenges posed by the green transition and presents policy options to address them. The first section takes as a starting point the fact that there is broad concern among citizens of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) around the seriousness of climate change and the importance of the green agenda. This section highlights that the green transition is not only an unavoidable agenda to address the existential threat of climate change but also an opportunity to restore dialogue and trust and improve well-being in the region. As such, green policies must be mainstreamed as part of a new social contract in LAC.

Moving the green agenda forward requires adequate, timely and transparent sharing of information as well as creating support for and avoiding resistance to policies that have strong and differentiated impacts across socio-economic groups, territories and generations. As such, the second section explores how to build consensus towards the green transition, making sure that all actors are effectively informed and involved in the process.

The third section argues that, for the green transition to be successful, policy instruments must be strengthened, with the coherence and long-term perspective of the agenda being fundamental. It analyses in detail the role of National Development Plans (NDPs) and other institutional mechanisms. The chapter concludes with key policy messages.

The green transition as the backbone of a new social contract

A new social contract that balances environmental sustainability with the needs of different socio-economic groups, territories and generations

The coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis exposed the weak foundations of the existing development model and aggravated the four structural development traps faced by LAC (OECD et al., 2021[1]). In pre-COVID-19 years, social grievances and higher aspirations for better living conditions already indicated that the pillars sustaining socio-economic progress through the years of bonanza (since the mid-2000s) needed rethinking. The rise of social discontent, marked by a wave of protests that started in 2019 and continued throughout 2020-22, confirmed the need to reach a new, overarching consensus and bridge the divide between society and public institutions.

These expressions of social discontent highlight the imperative for LAC countries to renew their social contract, to build back from the COVID-19 crisis in a more sustainable and inclusive way (OECD et al., 2021[1]). Social discontent is indeed partly driven by the impact of the crisis, but it also has a structural and multi-dimensional nature and can be explained by unmet aspirations for better jobs, quality public services, greater political representation and efforts to preserve the environment.

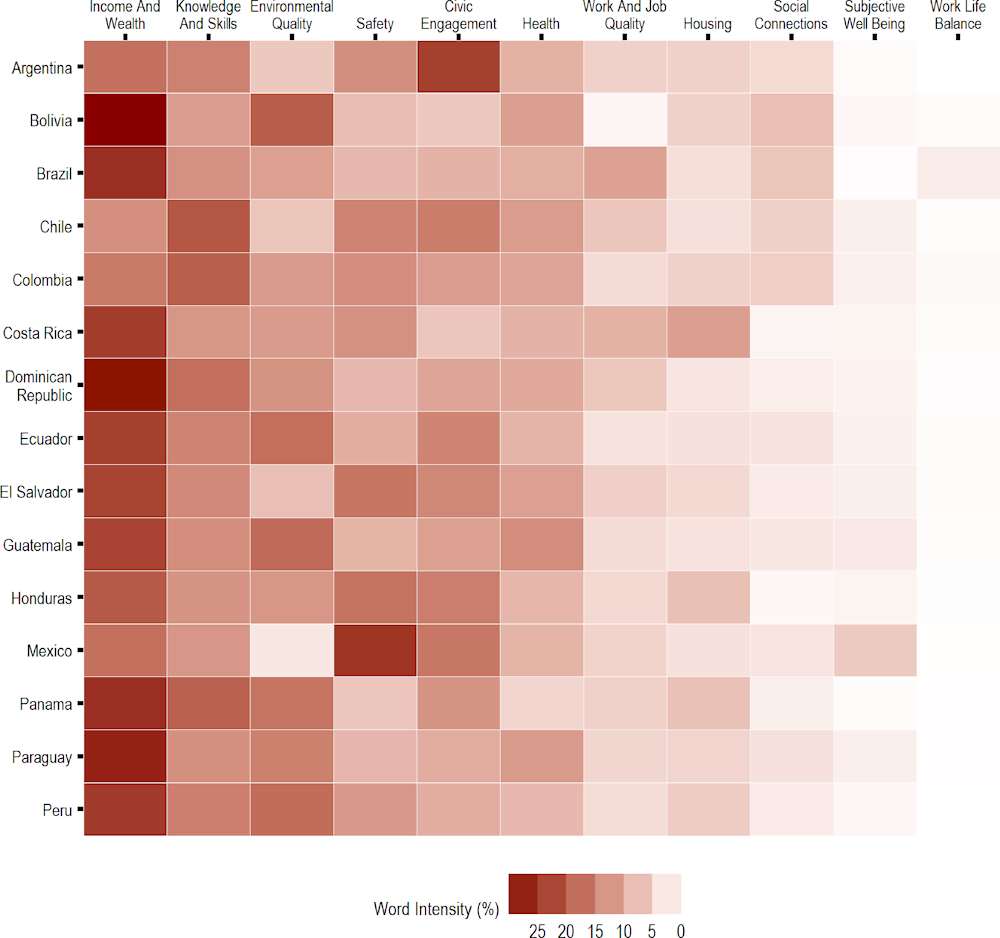

Given the widespread support for green policies in LAC, as well as the concern about climate change, the green transition can become the backbone of a new social contract that seeks to increase citizens’ well-being. This new social contract should rethink the present development model from a multi-dimensional perspective, putting the green dimension at the centre. This would entail advancing towards more sustainable production and consumption strategies, stronger welfare systems adapted to the challenges of the green transition, and green financing for development models to underpin these efforts. As green policies can have asymmetric impacts across socio-economic groups, territories and generations, adopting an intersectional approach will be crucial in order to balance the various costs and benefits and to gain support – and avoid backlash – around the green agenda (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1. Enhancing green dimensions of the social contract to improve people’s well-being

|

Improving people's well-being |

Across |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Socioeconomic groups (incl. income, gender, ethnic and racial) |

Territories |

Generations |

||

|

|

Promoting sustainable production strategies |

Providing quality green jobs and investing in retraining programmes for “brown workers” |

Defining transition strategies adapted to local skills and endowments (resource-rich vs. resource-poor communities) |

Fostering green growth and sustainable resource management |

|

Through |

Strengthening social protection and public services to support the transition |

Expanding the reach of social protection systems and social climate funds to support the transition from brown to green jobs |

Ensuring wide territorial coverage and investing in flexible mitigation and adaption mechanisms to respond to shocks and extreme weather events |

Better welfare systems to shield people from the adverse effects of climate change on health, income across time etc. |

|

|

Expanding sustainable financing for development |

Fairer and stronger tax systems that discourage polluting and wasteful practices |

Strengthening local financing and insurance mechanisms. Deepening local green markets |

Sustainable debt management and impact investment |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The current global crisis may be understood as a “critical juncture” – that is, an exceptional time of severe crisis that redefines what is possible (ECLAC, 2020[2]). In effect, when facing extreme circumstances and tensions, many actors become more willing to change the status quo, thus opening windows of opportunity for social, economic and political change (Capoccia and Kelemen, 2007[3]; Weyland, 2008[4]). In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, the role of the state has been expanding, mostly through temporary interventions; a renewed social contract could respond to the need to adapt and strengthen state capacities in the medium and long term. This entails progressively building genuine welfare states, which in turn requires new social and fiscal pacts (ECLAC, 2022[5]; Arenas de Mesa, 2016[6]). Such welfare states must be adapted to the future, address the new risk structure, guarantee the broadening of the scope of rights, and urgently respond to the challenges of low productivity, social vulnerability and inequality, institutional weakness, and technological and climate change (ECLAC, 2022[5]).

Citizens’ opinions about green policies: Where does the LAC region stand?

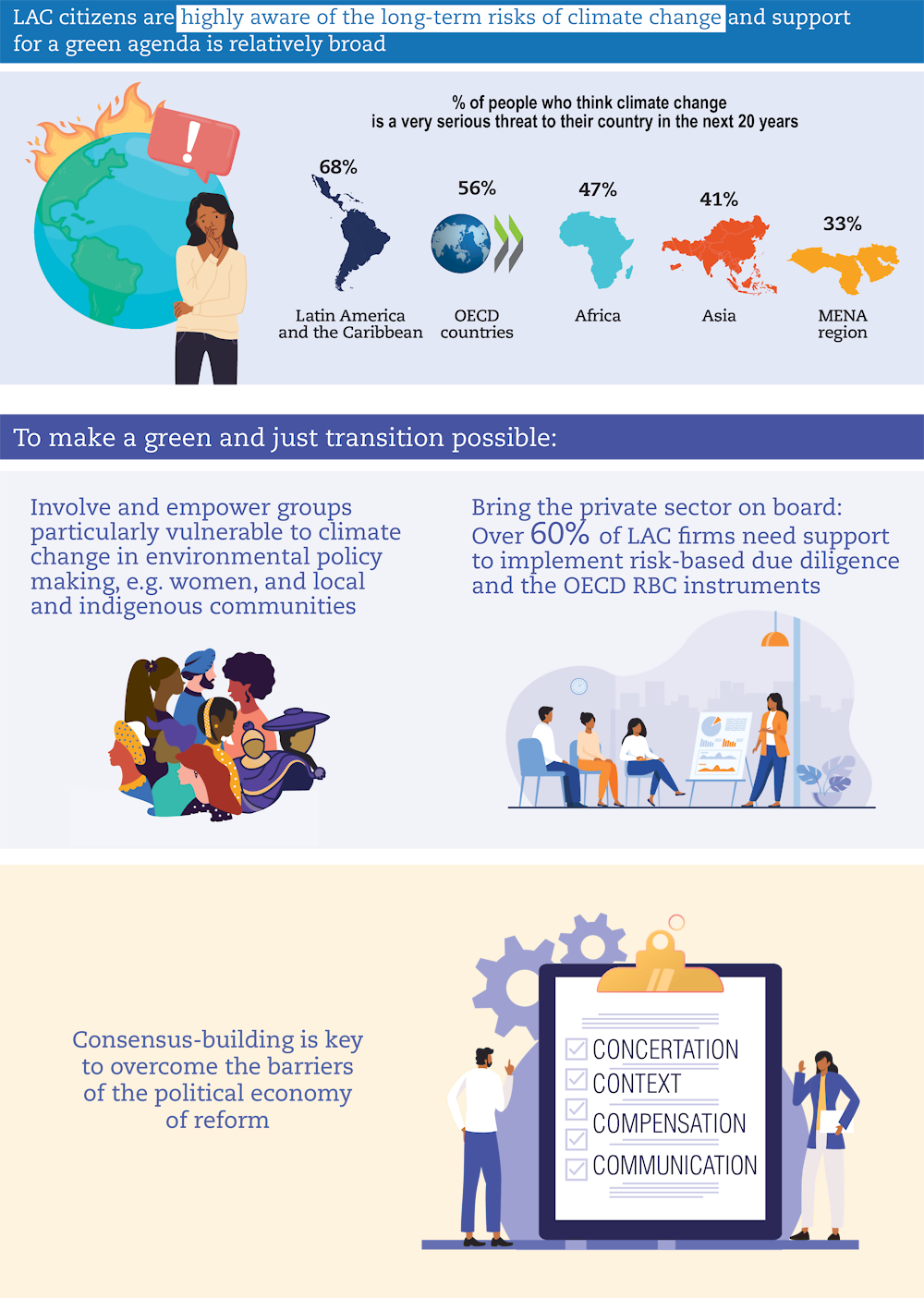

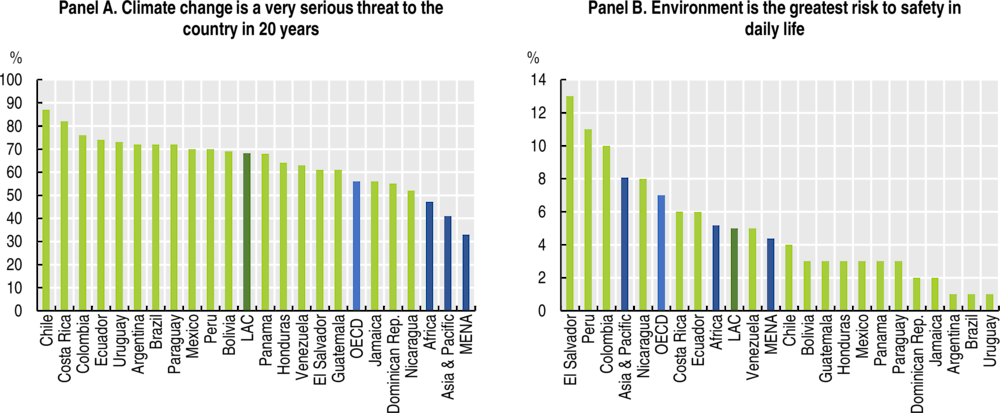

Latin Americans’ concern about climate change is among the highest globally (Figure 5.1, Panel A) (Dechezleprêtre et al., 2022[7]; Ipsos, 2021[8]). On average, 68% of LAC citizens recognise climate change as a very serious threat to their country in the next 20 years vs. 56% in countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 47% in the African continent, 41% in Asia and the Pacific, and 33% in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Among the most concerning issues for LAC citizens are the depletion of natural resources, water pollution and deforestation; globally, on average, the top environmental priorities are global warming, air pollution and waste management (Ipsos, 2021[8]).

Nonetheless, when asked about the greatest risk to their safety in daily life, LAC citizens tend to be less concerned about the environment than those in OECD countries and on a par with those in the African continent (Figure 5.1, Panel B). Multiple factors could converge in framing long-term (e.g. 20 years) and short-term (e.g. daily life) concerns, including lack of exposure to or awareness about the immediate effects of climate change, which may indicate a greater need for awareness-raising campaigns. The presence in LAC of more important risks to safety in daily life, including violence and unsafe work environments, may also explain the relatively minor importance placed on the environment (Figure 5.1, Panel B). When asked about the most important problem in their country, less than 1% of LAC citizens mention environmental problems or global warming. They instead place greater importance on unemployment and the economy, although priorities vary across countries (Latinobarometro, 2021[9]). This raises the need to frame the green transition as part of a more comprehensive strategy (e.g. the United Nations 2030 Agenda) that encompasses economic, social and institutional objectives.

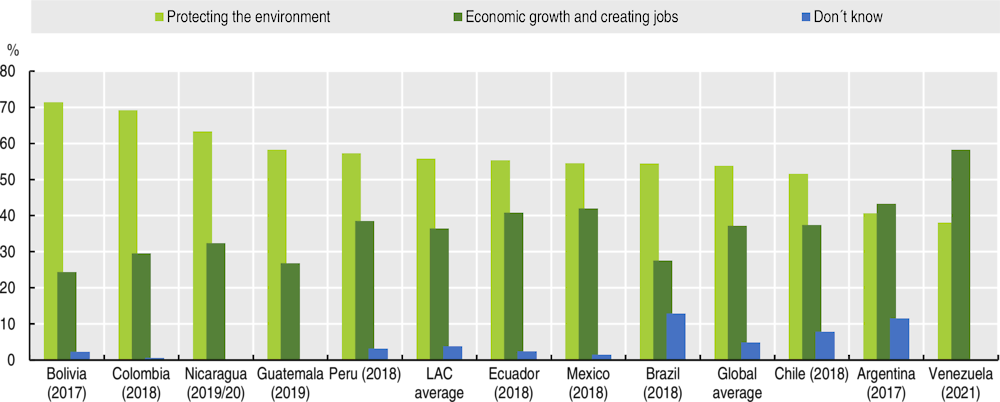

Overall, despite framing climate change and environmental issues as a longer-term (instead of immediate) problem, the majority of LAC citizens are willing to make sacrifices to protect the environment. A majority of citizens in Latin America (55.8%) think that the environment should be given priority, even if it causes slower economic growth and some loss of jobs, slightly above the global average of 53.8% (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.1. LAC citizens are highly aware of the long-term risks of climate change but tend to see the environment as a lesser risk in daily life

Notes: Question for Panel A: “Do you think that climate change is a very serious threat, a somewhat serious threat, or not a threat at all to the people in this country in the next 20 years? If you don’t know, please just say so”. Question for Panel B: “In your own words, what is the greatest source of risk to your safety in your daily life? Environment”.

Source: (Lloyd’s Register Foundation, 2020[10]).

Figure 5.2. A majority of LAC citizens think that the environment should be given priority, even if it causes slower economic growth and some loss of jobs

Note: Question: “Here are two statements people sometimes make when discussing the environment and economic growth. Which of them comes closer to your own point of view? A. Protecting the environment should be given priority, even if it causes slower economic growth and some loss of jobs; B. Economic growth and creating jobs should be the top priority, even if the environment suffers to some extent”.

Source: (Inglehart et al., 2022[11]).

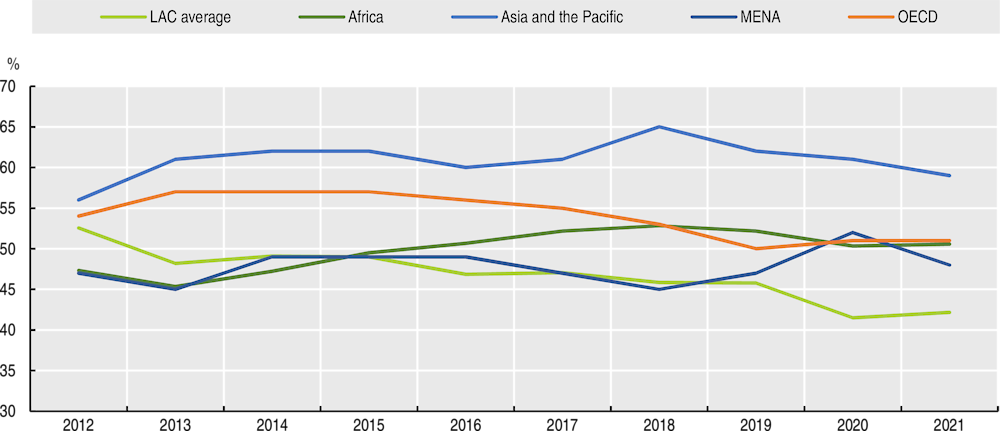

At the same time, in recent years, a greater share of LAC citizens is growing more dissatisfied with efforts to preserve the environment (Figure 5.3) and is calling for governments to act to fight climate change (Ipsos, 2020[12]). Among the regions analysed, LAC is the most dissatisfied with efforts to preserve the environment. The share of people satisfied with efforts to preserve the environment fell from 53% in 2012 to 42% in 2021 (Figure 5.3). The lowest levels of satisfaction with national preservation efforts were found in Brazil (23%) and Chile (19%); the greatest were found in some Central American countries, including Costa Rica (62%) and Guatemala (57%) (Gallup, 2022[13]). An SMS survey conducted in 13 Caribbean states in 2022 found that more than half of respondents (51%) believed that not enough is being done on climate action in their country (GeoPoll, 2022[14]). Overall support for the idea that the government and businesses – rather than individuals – should undertake the real efforts towards sustainability and environmental preservation is lower in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru than the global average (WIN, 2022[15]). Dissatisfaction with efforts to preserve the environment or the low levels of trust in government and firms in LAC may explain the preference for a more individualistic approach. As the green transition implies an all-of-society effort, this raises the need to deepen social cohesion and bridge the gap between citizens and institutions.

A further level of disaggregation helps in understanding which subgroups of citizens are more or less likely to be in favour of fighting climate change or supporting green policies. Based on the AmericasBarometer 2016/17, the most significant predictor of climate change concern in the LAC region is education, although wealth also plays a role. Worries about being affected by a natural disaster are almost as important as education in predicting climate change concern. It is therefore likely that attitudes about climate change may be shifting in the Caribbean in response to increased exposure to destructive natural disasters (Evans and Zeichmeister, 2018[16]).

Figure 5.3. On average, LAC citizens are becoming more dissatisfied with efforts to preserve the environment in their country

Note: Question: “In this country, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with efforts to preserve the environment?”.

Source: (Gallup, 2022[13]).

Concern about climate change is consistent across the political spectrum. Interestingly, in the United States, identifying as a conservative is associated with a 25% decrease in climate change concern compared to political centrists. In LAC, there is almost no difference in level of concern between centrists and liberals, and only a small although statistically significant decrease in concern among conservatives (Evans and Zeichmeister, 2018[16]). The broad concern for the environment across the political spectrum is also confirmed by the representation of green parties in national legislatures, as in Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico. These parties show mixed ideologies, with positions ranging from the far right to the left, especially in Brazil and Mexico (McBride, 2022[17]). Moreover, indigenous movements with an environmental agenda have also gained power in legislatures, most notably the Movement Toward Socialism party in Bolivia and the Pachakutik Movement in Ecuador (Rice, 2017[18]).

The COVID-19 crisis may have changed perceptions of climate change and support to fight it. A study conducted in February 2021 in 16 economies, including Brazil and Mexico, finds that the pandemic heightened concern about climate change. However, those who lost jobs or suffered income shocks due to COVID-19 were more reluctant to support green recovery policies that may require some short-term costs (Mohommad and Pugacheva, 2021[19]).

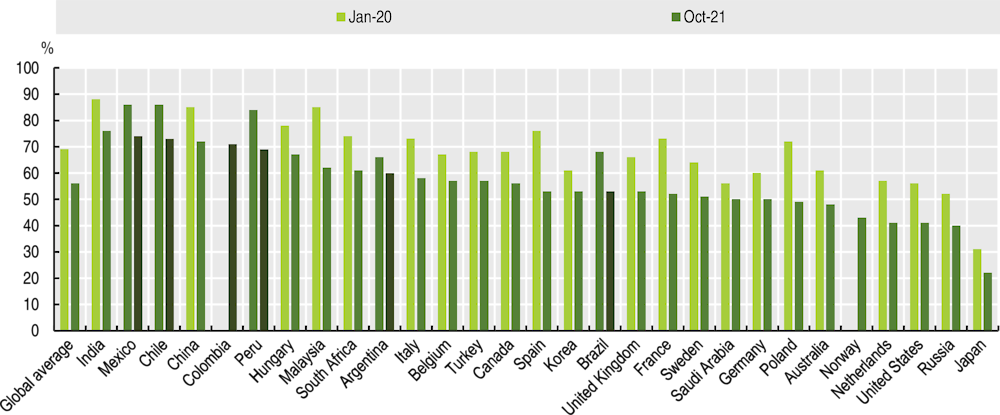

Income-driven considerations may therefore become more important for some parts of the population, despite high concern about climate change. Evidence from the 2008 global financial crisis shows that large, negative income shocks can affect the way people rank priorities towards a greater concern for jobs over climate change (Scruggs and Benegal, 2012[20]). A comparison of pre- and post-pandemic behavioural preferences shows that Latin Americans remain among the citizens most willing to change their behaviour out of concern about climate change. However, the changes to daily life caused by the pandemic resulted in decreasing concern about the environmental impact of products and services they buy or use (Figure 5.4). Protecting income and livelihoods in the near term is therefore key to sustaining support for climate-oriented green recovery policies (Mohommad and Pugacheva, 2021[19]). It is particularly necessary to understand the needs and aspirations of the vulnerable. This subgroup has expanded as a consequence of the crisis; although it may share middle-class aspirations, its more unstable and precarious position makes it more prone to prioritise everyday issues over environmental considerations.

Figure 5.4. Citizens’ concern about the environmental impact of their consumption habits decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic

Note: Question: “Over the past few years, have you made any changes regarding the products and services you buy or use, specifically out of concern about climate change?”.

Source: (Ipsos, 2021[21]).

Overall, this shows that the high concern about climate change and support for tackling environmental issues among LAC citizens could make the green transition the binding element of a wider social contract for the region. It is therefore key to consider the green transition as part of a comprehensive set of economic, social and institutional policies to advance towards a more inclusive, just and sustainable development agenda. However, as illustrated by the increasing discontent caused by the rising energy and fuel prices, these policies must also mitigate the short-term impacts of the transition on the most vulnerable groups in order to be politically viable (Section below on political economy).

Rising mistrust of public action and institutions may hamper the green transition

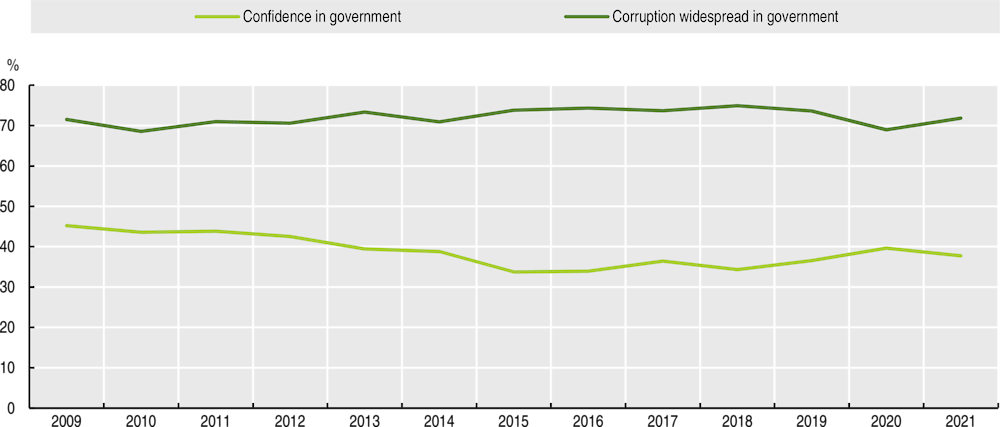

While Latin Americans may support a drive towards sustainability and a green economy in view of the risks posed by climate change and environmental degradation, they have little confidence in the efficiency and neutrality of public action and institutions. Even prior to the pandemic, rising mistrust was a common feature in LAC (OECD et al., 2019[22]; Maldonado Valera et al., 2021[23]). Trust in key public and political institutions – including the national police, the government, the judiciary, congress, electoral authorities and, at the lowest level, political parties – was persistently low and has tended to fall since the 2010s. In 2020, confidence was lowest in legislatures (20%) and political parties (13%) (Latinobarometro, 2021[9]). The share of the population with confidence in the government declined from 44% in 2011 to 38% in 2021. The share of people who think that corruption is widespread in the government has been consistently higher than 70% in the past decade, with the exception of 2020 (69%), and stood at 72% in 2021 (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5. Low trust in institutions and the perception of widespread corruption are key structural problems in LAC

Trust is the cornerstone of democracy and public governance. Declining confidence in institutions can result in lower compliance with the law in general, as well as a decreasing observance of civic duties, such as paying taxes (OECD et al., 2019[22]; Rothstein, 2011[24]). Lower trust can also negatively affect the government’s ability to implement reforms, thereby directly affecting citizens’ well-being. This poses a challenge for defining a common policy agenda towards a green transition backed by a broad and long-term consensus. Low trust requires paying attention to the political economy of reforms and promoting institutional change, as well as specific measures to improve efficiency, transparency, accountability and the policy coherence of public institutions. In the face of a complex endeavour, institutions and public authorities in the region should leverage support for environmental policies to table a larger discussion around the pillars of the welfare state and the social contract. Growing concern about climate change and support for green recovery policies during the pandemic have built momentum for the discussion of renewed and sustainable social pacts centred around the environment and sustainability. The green agenda may therefore help build coalitions supporting a wider reform agenda in the region. Effective and evidence-based communication around the green agenda can also strengthen the credibility of government action and positively enhance key drivers of trust.

Political economy of the green transition: The need to build support and avoid resistance to change

In moving the green transition forward and making it the centrepiece of a new social contract in LAC, policy makers must be aware of the political economy issues that may enable or limit their efforts. A green transition involves a shift of resources among economic sectors and political constituencies, as well as institutional and policy changes, that may trigger the opposition of some interest groups (Arent et al., 2017[25]). Similarly, such a transition goes beyond formal government institutions and includes other stakeholders, such as informal networks, civil society, the private sector, specific lobbying groups, and a wealth of actors and structures operating at various levels, from local to international (Worker and Palmer, 2021[26]; Edenhofer et al., 2014[27]). These actors may have competing interests and political priorities, shifting public opinions, and different levels of exposure to climate policy.

Understanding these political economy dynamics can better position policy makers to anticipate the response to green policies and identify actions to support coalitions, shift incentives and amplify the contributions of non-state actors to advancing the green transition (Worker and Palmer, 2021[26]). In fact, vested interests and rent-seeking arrangements may make it extremely difficult to change the status quo. This is especially relevant in a context marked by low trust and deep intersecting inequalities, where powerful elites can greatly influence political decisions, hampering the building of broad consensus and implementation of inclusive social and fiscal pacts (OECD et al., 2021[1]).

A transparent governance and policy process can strengthen social cohesion and boost the prospects for building wider social and political consensus for sustainability. Stronger accountability mechanisms and citizen oversight can contribute to promoting integrity and avoiding policy capture. To boost trust in public policies, governments should develop mechanisms for recognition, participation and conflict resolution. More generally, it is crucial to improve the rule of law and the quality of democracy. These can be enhanced by implementing open and participatory policy decision-making processes; strengthening mechanisms for accountability and efficiency; and improving information and the quality of public debate by ensuring greater access to information systems and transparency bodies, as well as greater media openness and transparency (Maldonado Valera et al., 2022[28]). On this matter, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government includes provisions to promote citizen and stakeholder participation throughout the policy cycle, and greater transparency and access to information (OECD, 2017[29]). In addition, the OECD Guidelines for Citizen Participation Processes suggest a ten-step path to design, plan, and implement a citizen participation process, from the identification of a problem to solve to the evaluation of the process and the cultivation of a culture of participation. These Guidelines also suggests eight guiding principles that help ensure the quality of these processes, namely purpose, accountability, transparency, inclusiveness and accessibility, integrity, privacy, information, and evaluation (OECD, 2022[30]).

Building consensus for a green, inclusive and just transition

A green, inclusive and just transition requires institutional mechanisms to foster dialogue and build consensus around reforms. Otherwise, entrenched stakeholders may try to pull the process in opposite directions, with some promoting and others obstructing change (Arent et al., 2017[25]). Similarly, a green transition may bring not only benefits but also significant costs and negative impacts – across the board and for specific socio-economic groups – at least in the short term (Chapters 1, 3 and 4). Mitigating these short-term costs and communicating about them in a relevant, timely and transparent manner is important to bring the temporary losers on board, to strengthen the credibility of government action, and to generate perceptions of responsiveness and reliability among the population.

Policy makers must factor in these dynamics when reflecting on how to govern the green transition to make it possible and just. Among other considerations, it is important to identify and involve key stakeholders in the policy-making process from the beginning; to bring on board interest groups to avoid having them work against the climate action strategies; to understand the socio-political context to appropriately adjust the speed and scale of the transition; to devise a clear communication strategy, based on key outcomes, to shape the transition narrative; and to design a comprehensive set of policies to support people throughout the transition and avoid certain groups or sectors feeling disproportionately affected by it. As described below, these principles can be broadly summarised under four Cs: 1) concertation; 2) context; 3) communication; and 4) compensation (Cabutto, Nieto Parra and Vázquez Zamora, 2022[31]).

Concertation of the interests of all parties through inclusive and participatory processes

Initial loss of jobs, increased tax burden, transport and energy price increases, and more stringent regulations for some business activities may generate opposition to the green agenda, particularly if all interested parties are not involved in the decision-making process from the beginning. Identifying key stakeholders, as well as the institutions and networks through which they act, is therefore vital.

The complexities of the green transition imply that the public sector will need support from civil society, intermediary bodies and the private sector to move forward the agenda (Sections below on the role of civil society and the private sector). One of the most important short-term effects of the green transition involves employment contraction in some activities as the production structure shifts to more sustainable ones (Chapter 3). These transformations will require the involvement of trade unions, business associations, local leaders and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Thus, the transition requires a full mobilisation not only of government but also of society.

A protected and promoted civic space is a prerequisite for such collaboration between civil society and governments and for a more inclusive green transition. Such a space is defined by the OECD as the set of legal, policy, institutional and practical conditions necessary for non-governmental actors to access information, express themselves, associate, organise and participate in public life (OECD, 2021[32]). To participate throughout policy- and decision-making cycles, evaluate results, express their views and provide oversight of government activities, citizens and civil society organisations (CSOs) need the guarantee – by law and in practice – of fundamental civil rights such as freedoms of expression, peaceful assembly, association and the right to privacy. Governments are thus encouraged to support a vibrant civic space as an enabling environment for citizens and non-governmental actors to fully exercise their democratic rights and actively engage on environmental issues (OECD, 2022[33]). Some practical actions may include the improvement of the enabling environment for CSOs by facilitating access to funding and simplifying the legal regime, as recommended in the OECD Open Government Review of Brazil (OECD, 2022[33]).

Engaging in transparent and participatory processes can have multiple benefits. First, it can help identify appropriate policies that safeguard the interests of all stakeholders. Given the cross-sectoral nature of the green transition, a multi-stakeholder process can help conciliate various interests and achieve a negotiated policy stance. Moreover, the process of engagement with key stakeholders can help sustain a high level of support for climate reform policies beyond short-term political cycles, even during political transitions, thereby preventing conflicts of interest or reform rollback when leadership changes (OECD et al., 2021[1]; UNECA, 2020[34]). For instance, past experiences with the phase out of fossil fuel subsidies show that successful reforms require extensive consultation in design and implementation (UNECA, 2020[34]).

To broaden the dialogue and boost the sense of ownership of agreements achieved, considerable effort must be made to give voice and influence to sectors and population groups that have been discriminated against or excluded, as well as to groups more vulnerable to shocks and emergencies. The state should maintain effective venues for dialogue and participation and have a decisive mediating role to ensure the interests of all actors are fully represented and not silenced by majority decisions. Citizen participation and social movements are significant in driving major changes and influencing the political agenda.

Deliberative processes are useful instruments to build consensus around policy challenges that require complex trade-offs and a long-term vision. A relatively recent example, directly connected to the green transition, is the 2019-20 French Citizens’ Convention on Climate, which was set up as a direct response to social mobilisation in the country (OECD, 2020[35]). Although less common in LAC, climate assemblies are a representative deliberative process dealing exclusively with environmental issues. They involve a group of randomly selected citizens who are statistically stratified to make up a microcosm of society that deliberate based on evidence and information to provide policy recommendations to public authorities. Examples have taken place in Spain, the UK, Finland, France and Denmark (OECD, 2020[35]). In Brazil, a similar deliberative process took place in 2019 with the creation of the Citizen Council of Fortaleza, with 40 randomly-selected residents deliberating on solid waste management (Pogrebinschi, 2020[112]).

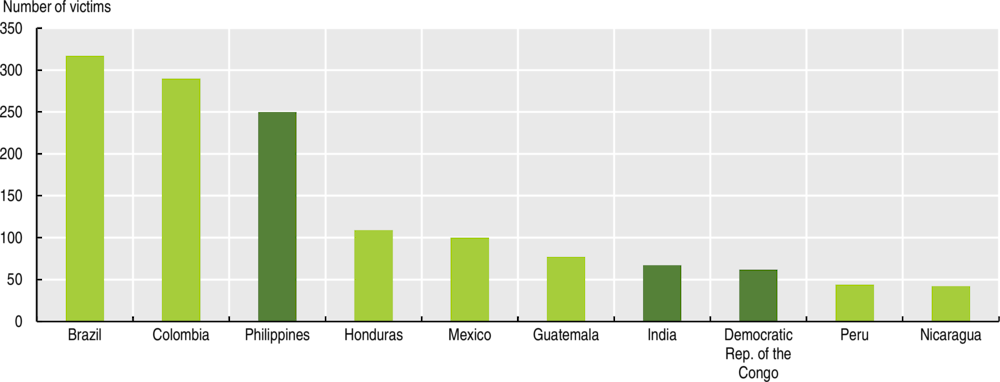

Protecting environmental defenders and local communities is a prerequisite of any real participatory process. Social conflicts associated with natural resources are increasing, and social environmental defenders can be at risk of physical harm. Between 2012 and 2020, 1 540 land and environmental defenders were murdered around the world, with LAC accounting for over two-thirds of killings, making it the region most affected by threats and attacks targeting human rights defenders and environmental activists (Figure 5.6) (Frontline Defenders, 2022[36]). These killings relate mainly to land use issues and the mining and extractive activities sector.

Figure 5.6. Number of environmental defenders murdered in LAC and other countries, 2012-20

Understanding the context to find the right policy pace and sequencing

There is no single blueprint for a successful green transition. Each country should balance local needs and priorities and adapt the speed and scale of the reform process to the socio-political context. For instance, fiscal policy is key to support the ambitious efforts needed to achieve the transition. However, as households and businesses are still recovering from the COVID-19 crisis, in the short term, governments may prefer to avoid increasing the fiscal burden and instead focus on policy options that may still contribute to strengthening public finances (e.g. intensifying the fight against tax evasion and avoidance or eliminating ineffective tax expenditures).

In the post-pandemic era, context-specific considerations are vital for the recovery. Well-designed green recovery plans (e.g. investments in renewable energy infrastructure, public and low-carbon transport options, clean-up of polluted sites) can be more acceptable than environmental tax reform (Vona, 2021[38]). For instance, investments in research and development (R&D) can foster innovation for the green transition and are also politically acceptable (OECD, 2019[95]). Depending on the context, policy makers may prefer to bundle reforms into a comprehensive package so that losses from one reform are compensated by gains from others, e.g. embedding income support schemes for poor households in wider energy subsidy reform packages. Or, if this is not possible, to reach specific agreements and incremental policy advances in areas with potential for accord (OECD et al., 2021[1]). For instance, by reacting early to a mix of climate change and geopolitical concerns, Sweden has strengthened the security and sustainability of its energy supply through a gradual energy transition based on consensus among the parties. Among others, it introduced a tax on CO2 emissions and grants for heating networks powered by bioenergy since the 1990s. In 2003 it further introduced a system of green certificates that strengthened renewable electricity output by 13.3 TWh between 2003 and 2012 (Cruciani, 2016[114]).

Communicating effectively to build trust and favour consensus

In the context of polarised political discourse and rising mis- and dis-information, a commitment to evidence-based analysis and effective communication is imperative to frame a clear transition narrative and reach broad consensus (Matasick, Alfonsi and Bellantoni, 2020[39]). In particular, aversion to environmental policies may be due to misinformation and stereotypes, which often highlight the income costs of policies over their health benefits. Public communication1 is a powerful tool, as ideas and narratives can shape what stakeholders see as the problem in climate policy and the potential solutions. Communicating results in an effective manner, both within the public administration and outside, can also improve the responsiveness and reliability of government action (OECD, 2021[40]). Transparent communication about the reasons behind potential delays in implementing specific plans or adjustments required during the course of action can help mitigate feelings of disillusionment.

Solid analysis and research by authoritative institutions, together with targets and indicators, are essential to build the case for action. This requires investing in data collection, building strong and independent national statistical offices, co-ordinating data publication and sharing across agencies, and committing to ex post evaluation. At present, data on the environment and climate change are still scarce globally. In particular, few statistical indicators have been developed to monitor oceans (United Nations Sustainable Development Goal [SDG] 14), sustainable consumption and production (SDG 12), gender equality (SDG 5) and sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11) (OECD, 2022[41]). In addition to this, out of the 231 unique indicators in the SDG framework, 114 have an environmental angle, but only 20 of those provide for gender-specific and/or sex disaggregation, evidencing a shortage of indicators to support gender-sensitive environmental policy making (Cohen and Shinwell, 2020[107]; OECD, 2021[108]).

Statistical capacity development for environmental and related issues is key to communicate the urgency of the green agenda to citizens and to make informed decisions. Investments should aim to facilitate data accessibility, comprehension and reuse in order to generate public value and have an impact on policy making (OECD, 2019[42]; OECD, 2018[43]; Grinspan and Worker, 2021[44]). Avoiding data fragmentation across agencies is also important. For instance, in Costa Rica, strong political support for open data from the Ministry of the Presidency helped establish institutional arrangements among agencies for continuous data provision and led to the development of the National System of Climate Change Metrics (SINAMECC), an online open platform for climate-related data (Grinspan and Worker, 2021[44]).

A number of issues pertaining to scientific communication and climate change communication more specifically should not be overlooked. These include the necessity to communicate complex data and scientific discoveries without turning people off; the importance of exhorting citizens to act against climate change without sending apocalyptic messages that may be disempowering; and the need to create empathic connections between climate change and citizens’ everyday lives to avoid framing it as an abstract, isolated and faraway problem (Olano, n.d.[45]; Yale Climate Connections, 2017[46]).

Public institutions seeking to engage citizens on climate change action need to invest in the professionalisation of the public communication function, including on areas such as audience and behavioural insights. Indeed, the OECD Report on Public Communication finds that governments’ focus on audience insights can be improved, with just 27% of Centres of Government (CoG) conducting this activity at least on a quarterly basis. Also, governments may not always be the best placed to circulate certain messages. Enlisting third-party messengers as vehicles for official information and developing partnerships with scientists or community leaders can help engage citizens in the green agenda in a more compelling manner, while amplifying the reach and trustworthiness of communication. The use of community messengers and influencers as relatable and trusted voices can also improve how inclusive communications are of diverse groups in society. Such people can help to identify under-served groups and the barriers to information. Choosing appropriate formats that can engage diverse audiences, on line (e.g. social media) and off line (OECD, 2021[40]) is also of the essence. More tailored messages are more likely to resonate than mainstream channels or content. By helping communicators account for the cognitive factors, barriers and biases shaping how people navigate an increasingly complex, crowded information ecosystem, the application of behavioural science can help engender more compelling communication (OECD, 2022[47]).

Compensating those who stand to lose to bring everybody on board

From the perspective of increasing the political acceptability of the green transition, governments will have to think about a comprehensive series of actions to support citizens and communities throughout the journey. The transition involves several monetary and non-monetary distributional effects, which policy makers should study carefully. In turn, policy actions undertaken will determine whether potential losers bear the costs of the transition, affecting the level and intensity of resistance to green policies.

To increase support for such policies, policy makers should distinguish between small and large distributional effects of climate policies and find the appropriate combination of revenue-recycling schemes (e.g. mechanisms that earmark income generated from carbon taxation to return it back to society), industrial and retraining policies, and compensation packages. When environmental policies are part of a broader political package, small distributional effects of climate policies may become almost irrelevant for political acceptability if offset by other policies (OECD et al., 2021[1]). For instance, bundling a carbon tax and policies promoting greater fiscal progressivity in a fiscal reform package may help reduce resistance to the potential income effect of the carbon tax (Vona, 2019[48]).

The argument is different when green policies have large distributional effects, most notably when resulting in job losses. Large distributional effects can also be spatially concentrated, as extractive or energy-intensive industries tend to be located in the same area, creating large constituencies that oppose green policies and influence the ideology of locally elected members of parliament (Vona, 2019[48]). In this case, the post-coal labour market transition in the Ruhr region in Germany shows that investing in long-term planning promoting industry diversification, active labour market policies and retraining facilities can help from both equity and political acceptability perspectives; by mitigating negative income effects and supporting the transition from brown to green jobs, such investment can decrease resistance to such transition policies (Chapter 3; Arora and Schroeder, 2022[113]).

Overall, environmental policies and resulting compensation schemes should aim to be fair, efficient and cost-effective. However, as aversion to specific types of policies may go beyond these considerations, calculations of political acceptability should also inform environmental policy making (Vona, 2021[38]). For instance, environmental tax reform raises stronger opposition than lump-sum redistribution or spending on green projects. This is due to the fact that upfront carbon compensation provides an immediate and direct benefit, while the benefits from lower labour taxation are harder to calculate, as they are indirect and uncertain.

Similarly, beyond compensation schemes (redistribution), and in view of creating a broad constituency in favour of green policies, general interventions aimed at tackling inequality (predistribution) may help expand the size of the middle class, increasing the number of citizens wealthy enough to care more about collective goods and the environment. In this regard, universal social protection and universal access to social services (notably education and health) are essential not only to compensate or render potential losses acceptable to large sectors of LAC societies but also to avoid deeper and/or new inequality gaps, as well as unintended poverty increases arising from a structural transition to sustainability.

Role of citizens and civil society, including the crucial role of women and local communities

Civil society participation can strengthen the outcome of a green transition envisioned as truly inclusive. Moreover, expanding quality spaces for civic participation can improve citizens’ well-being. Realising that citizens have a role to play boosts civic engagement and a sense of belonging. If sustained over time, civic participation could also have a positive effect on social inclusion mechanisms by giving visibility to the needs of vulnerable groups and creating spaces for exchange. Civil society’s participation throughout the cycle of green policies can play a vital role in the outcomes, as the inclusion of public views is closely linked with the sustainability of green projects (IDB, 2021[49]). An enabling environment, which encompasses a conducive legal and policy environment safeguarding freedom of association, is central to ensure that CSOs can operate in a free and autonomous manner and reach their full potential. On the contrary, active and effective participation in the policy cycle is hindered if CSOs are struggling to operate, arbitrarily dissolved or overburdened with disproportionate administrative obligations.

Civil society can bring new insights and innovative practices through local knowledge. It can also help anticipate emerging issues and support effective policy implementation by fostering trust among stakeholders. Making the different stages of the policy cycle accessible to members of communities directly affected by green policies also incentivises higher levels of transparency.

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government refers to stakeholders, grouping together both citizens and any interested and/or affected party such as civil society organisations (OECD, 2017[29]). Involving citizens and/or stakeholders is equally important, but their participation should not be treated identically. The line between these groups can be blurry and, in reality, is not always perfectly neat. Both groups can enrich public decisions, projects, policies, and services. Stakeholders can provide expertise and more specific input than citizens through mechanisms such as advisory bodies or experts’ panels. Involving citizens can bring diversity by including rarely heard voices, it can help raise awareness and facilitate public learning about an issue and, in the medium to long term, it can strengthen democratic feelings and trust in institutions. The National Council of Environment (CONAMA) in Brazil, a national consultative and deliberative body involving government representatives and non-governmental stakeholders, is an example of participatory practice in environmental matters taking place in the region. Established in 1981, CONAMA has the authority to establish regulations for polluting activities and to carry out environmental impact studies for public and private projects (CONAMA, 2018[105]). Another example is the Climate Change online platform “BA Cambio Climatico” of the city of Buenos Aires that gathers open environmental data and promotes citizen participation for a greener city. The platform was co-developed with citizens and stakeholders through meetings, interviews, a hackathon, and eight roundtable discussions with over 600 inhabitants (OIDP, 2020[106]).

The regional Escazú Agreement2 is an important tool to improve policy coherence and the transparency and accountability of national governance. The agreement aims to promote civic participation in environmental matters along three key dimensions: 1) access to environmental and climate information; 2) involvement in decision making; and 3) access to environmental justice. Enacted in 2018, the agreement entered into force in 2021 and has been signed by 24 countries and ratified by 12 LAC countries. It offers a benchmark and a guide for countries, giving legitimacy and support to these processes of change (Chapter 6; ECLAC, 2018[50]).

Women as key actors to address climate change

Given their over-exposure to the effects of climate change, the perspective of women can ensure that measures against climate change are inclusive and comprehensive. Women are more vulnerable to climate change impacts than men as they are more likely to be in poverty, have less access to basic human rights, such as free movement and land acquisition, and are more dependent on the natural resources which climate change threatens the most (Ward, 2022[117]). The Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) 2019 shows that the level of discrimination in social institutions in LAC is highest in Haiti (39.9) and lowest in Colombia (15) (OECD, 2019[118]). Understanding their realities and including their life lessons throughout the policy cycle will help build more robust climate mitigation and adaptation actions and programmes. Moreover, by raising their visibility, women can become more relevant actors. This presence, such as their inclusion in vulnerability assessments, can have positive effects (IDB, 2021[49]; OXFAM, 2018[51]).

The processes of climate change adaptation and mitigation should be gender sensitive. Policies that consider gender sensitivities acknowledge these vulnerabilities and incorporate them throughout the policy cycle to produce stronger responses. A comprehensive green transition should also identify and recognise the potential women and girls have as agents of change. In LAC, women represented only 7% of environment ministers in 2021 (OECD, 2021[52]). Including women in environmental decision-making roles could increase not only the gender focus of environmental policies but also their effectiveness (OECD, 2021[52]; Strumskyte, Ramos Magaña and Bendig, 2022[109]). At a local level, women can be key actors in emergency agencies. For example, women in small villages of the Caribbean tend to know its members, making them better able to identify who is missing or hurt after a natural disaster, to organise shelters and to provide aid (IPCC, 2014[53]).

An integrated approach to gender equality and environmental sustainability – i.e. recognising the gender-environment nexus – could help to alleviate limitations to gender equality and women’s economic empowerment and enhance women’s role in environmental sustainability and green growth (OECD, 2022[110]). In agriculture, creating opportunities to increase women’s ownership of rural land is a key priority, as it is often correlated with greater food security, greater bargaining power at household and community levels, greater economic independence, better child nutrition and lower levels of gender-based violence. While most women in LAC work the land, only 18% on average are land-owners. Although female land-ownership levels in LAC are higher than the global average of around 15%, high heterogeneity remains in the region, ranging from below 9% in Guatemala and Belize to over 30% in Peru (FAO/IFPRI, 2018[115]; Deere, Alvarado and Twyman, 2012[54]).

Promoting opportunities for young women and girls to study and to develop in green jobs will also help raise gender sensitivity and close the gender pay gap. Gender stereotyping in childhood and youth tends to discourage female presence in technical sectors that are critical for the green transition and the future of jobs, such as sciences, physics, computational molecular biology and digital technology (OECD, 2021[52]). Moreover, women and girls from local communities hold unique traditional knowledge and practices that could be key inputs for green jobs and the circular economy in general. A good example is the improvement they could bring to land use and farming, as they tend to know and employ ancient uses of plants and animals.

Community-driven development to engage local communities in social and environmental policy solutions

Locally led adaptation and mitigation efforts recognise that local communities are on the frontlines of climate change and are often best placed to identify solutions. It is therefore important to support the power of local communities to influence adaptation efforts. To avoid overburdening local partners, a more equitable distribution of power and resources towards local communities should take into account specific contexts, local cultures and interests at play. In turn, communities should be supported in the development of new capabilities (WRI, 2021[56]).

Local communities and actors rarely have a voice in the decisions that most affect them. Current top-down approaches should be replaced by new models in which local actors have greater voice, representation, power and resources to build resilience to climate change. Several LAC countries have recognised in their legal frameworks the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) of indigenous peoples, which are also expressed in different forms in the ILO Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (no.169), ratified by 15 LAC countries, and the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The convention does not only include the right to prior consultation with indigenous peoples on any legislative or administrative measures that may affect them, but also their participation in the formulation, implementation and evaluation of plans and programmes. In Peru, the experience of the prior consultation with indigenous peoples on the Framework Law on Climate Change has resulted in the creation of the Indigenous Peoples’ Platform to Address Climate Change for managing, formulating and following up on proposals on climate change mitigation and adaptation by indigenous groups (FIIAPP, 2021[116]).

Local communities should be engaged as partners in advancing the green transition. One way to link communities and marginalised groups with higher-level policy making is to provide flexible funding to local actors. This means according local actors a certain autonomy to adjust activities according to local priorities and changing circumstances. Updating climate finance implementation mechanisms and providing technical and financial assistance needed to achieve locally relevant and effective development impacts are some examples of ways to make this possible (WRI, 2021[56]; World Bank, 2021[57]). Community leaders can play a key role in designing and implementing investments in green programmes that correspond to their community’s priorities.

Principles for locally led adaptation are intended to guide communities as they advance adaptation and mitigation programmes, seek funding, and undertake practices with increasing ownership by local partners. Three strategies can help: 1) putting design and funding in the hands of local actors; 2) enhancing institutional and technical capacity building; and 3) ensuring monitoring, evaluation and learning (WRI, 2021[56]).

Locally led does not mean locally isolated. Three aspects are important for the success of locally led green initiatives. First, local champions play a key role to advance reforms, maintaining a balance between local leadership and external support to ensure policy agendas are aligned with local goals. Second, an understanding of the local context and the political economy dynamics is needed to ensure the viability of policy reforms. Last, aligning the time horizons of policies with local priorities and capacities is relevant to avoid implementation gaps and find adaptable solutions that are seen as legitimate by local communities.

Role of the private sector: Responsible business conduct to support a green and just transition

The private sector is a key player to achieve sustainable and inclusive development and move the green agenda forward. As businesses are responsible for a significant share of environmental impacts, they are integral to a greener economy and society. The climate crisis highlights the central role of businesses and the need for firms to work with policy makers and other stakeholders to urgently adopt climate mitigation and adaptation actions. Public-private collaboration is also key for the creation of an enabling policy environment and an institutional framework that facilitates the twin digital and green transitions.

A number of policy-, science- and industry-led drivers have encouraged environmental action by the private sector (OECD, 2021[58]). Governments are increasingly using legislation and regulation as policy tools to promote more responsible business practices and sustainable financial flows. New legislation, particularly on human rights and environmental due diligence in global supply chains, has emerged in multiple jurisdictions in recent years.3 For instance, in February 2022, the European Commission adopted a proposal for a directive on mandatory corporate sustainability due diligence with respect to human rights and environmental impacts (Chapter 6). Likewise, companies increasingly recognise their responsibility to address their social and environmental impact, enhance supply chain resilience and respond to sustainable consumption patterns.

Instruments for responsible business conduct

Responsible business conduct (RBC) sets out that all businesses, regardless of their legal status, size, ownership or sector, must avoid and address the negative impacts of their operations, supply chains and other business relationships while contributing to sustainable development in the countries where they operate (OECD, 2022[59]; OECD, 2019[60]). The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (MNE Guidelines) and related OECD due diligence guidance4 champion RBC to help companies rise to the challenge of transitioning to a green economy and preserving the world’s greatest wealth: our natural ecosystems. The MNE Guidelines are the only multilaterally agreed and comprehensive code of RBC that governments have committed to promoting.

All governments adhering to the MNE Guidelines have the legal obligation to set up a National Contact Point (NCP) for RBC. NCPs are agencies established by governments to promote the MNE Guidelines, provide related due diligence guidance and handle non-judicial grievance mechanisms. Since 2000, close to 600 specific instances have been handled by NCPs in over 100 countries and territories (OECD, 2022[61]). To date, 51 governments have a NCP for RBC, including 8 in the LAC region (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay).

International RBC instruments can play a pivotal role in advancing the green transition in LAC by mainstreaming internationally agreed standards and safeguards into business decisions and actions (OECD, 2021[58]). For instance, Chapter VI of the MNE Guidelines (Environment) calls on enterprises to take account of the need to protect the environment and public health and safety, and generally to conduct their activities in a manner contributing to the wider goal of sustainable development. The environment chapter envisages that enterprises should have in place an environmental management system, with measurable objectives and targets, and should explore ways to improve environmental performance over the longer term. The guidelines also recommend that firms promote higher customer awareness of the environmental implications of using their products and services. The private sector is increasingly being held accountable on matters relating to RBC and the environment. As much as 24% of all specific instances submitted to NCPs made reference to provisions of the environment chapter of the MNE Guidelines (OECD, 2021[58]).

Risk-based due diligence is a key element of RBC. It refers to a process through which businesses identify, prevent and mitigate their actual and potential negative impacts and account for how those impacts are addressed. By implementing due diligence, businesses can not only mitigate the impacts of climate change and advance adaptation efforts but also be a major source of green finance and play a decisive role in making the green transition a driver of better jobs, greater respect for human rights, and increased integrity and trust. Carrying out due diligence is critical to ensure that business action on climate also takes into account social and human rights implications, possible trade-offs (or unforeseen adverse impacts across various risk areas as a result of action to address climate-related risk areas), and risk prioritisation considerations.

RBC practices in the region

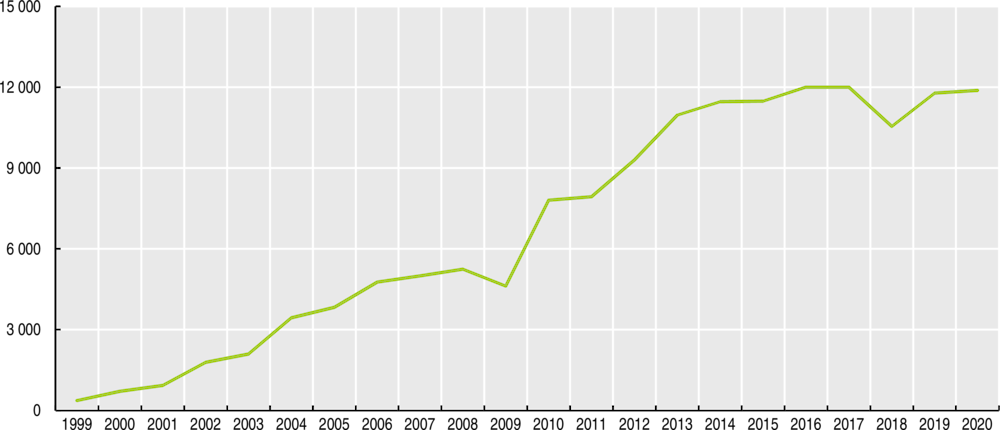

As a response to the growing role firms play in preserving the environment and to increasing scrutiny by society, the private sector – globally and in LAC – has increased reporting on RBC and sustainability issues, as well as adoption of environmental management systems. The sustainability reporting rates of the largest 100 companies by revenue in LAC are among the highest in the world. It has increased by 6 percentage points, from 81% in 2017 to 87% in 2020, compared to 95% in North America and 85% in Western Europe. Mexico (100%), Brazil (85%), Argentina (83%), Colombia (83%) and Peru (81%) rank above the global average (77%), while Panama (60%), Costa Rica (56%) and Ecuador (31%) remain below (KPMG, 2020[62]). In the financial sphere, the number of signatories of the Principles for Responsible Investment doubled in emerging markets over 2019-21, with Brazil being among the emerging countries with the highest number of signatories (OECD, 2022[104]). Adoption of environmental management systems has gradually increased among firms in LAC, signalling greater awareness of sustainability criteria (Figure 5.7). However, growth in the number of ISO 14001-certified enterprises is mainly attributed to efforts made by firms in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico (ECLAC, 2021[63]).

Figure 5.7. Number of LAC firms adopting environmental management systems increased more than thirtyfold since 1999

Note: This indicator provides information on the number of companies certified to ISO 14001. The figures include both private companies and public organisations. The international standard ISO 14001 is part of the family ISO 4000. This standard applies to any company, independent of its activity, size or country of operation, that is implementing an environmental management system on the basis of compliance with national legislation and continuous improvement of its performance.

Source: (ECLAC, 2021[63]).

According to the OECD 2021 Business Survey on RBC in LAC,5 the majority of businesses surveyed have taken steps to manage social and environmental risks: 75% of respondents indicate they have in place a policy setting out RBC expectations and 55% report on their RBC-related practices. However, practical implementation of RBC remains a challenge in LAC countries. Only a minority of businesses seem to conduct risk assessments along the supply chain to minimise the negative impacts of their activities and maximise their positive contributions to sustainable development. Only 40% of respondents adopt a due diligence process when risks are identified, and only 21% take into account suppliers and business partners beyond Tier 1 in the supply chain. In addition, only 36% of businesses are familiar with the support that NCPs can provide to promote and facilitate RBC. Nevertheless, according to the survey, businesses are keen to fill the implementation gap for RBC and to address environmental, social and human rights issues in their supply chains. Over 60% indicate the need for further support and trainings to implement risk-based due diligence and the OECD RBC instruments (OECD, 2021[64]).

Key sectors linked to environmental impacts and climate change risks in LAC: Agriculture and extractives and minerals

Environmental considerations are of particular relevance for some main sectors of activity and trade in LAC, and thus support adoption of RBC practices and standards. For instance, the extractive and minerals sector plays a major socio-economic role in LAC. However, it causes significant environmental and social impacts, including cases of water, air and soil pollution, deforestation and loss of biodiversity. These impacts can also fuel social conflict. An increasing number of industry initiatives aim to address these issues. For instance, extractive companies in the region started to identify and assess environmental risks by tracking and disclosing data from mining sites (OECD, 2022[65]).

Through expansion of land use or increased yields, the agricultural sector can also contribute to environmental degradation, such as forest and biodiversity loss, soil degeneration, water pollution and overexploitation, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Many agricultural companies operating in the region are taking on these challenges, for example by using certification schemes and developing innovative technologies for sustainable production (OECD, 2022[66]).

To address the negative impacts in these key sectors, it is important that companies have strong internal due diligence mechanisms and policies, and that they integrate relevant environmental standards and international best practices into their operations. Environmental impacts from business activities are usually better managed and avoided when companies have created adequate spaces for dialogue, consultation and engagement with stakeholders throughout the supply chain due diligence process (OECD, 2017[67]). Stakeholder engagement can be more effective and better help identify and address risks when it is: 1) two-way, meaning that parties freely express opinions, share perspectives and listen to alternative viewpoints to reach mutual understanding, with some degree of shared decision-making power; 2) in “good faith”, meaning that parties engage with the genuine intention of understanding how stakeholder interests are affected by enterprise activities; and 3) responsive, meaning that there is an active implementation of commitments agreed to by parties (OECD, 2017[67]). In both the agriculture and the extractives and minerals sectors in LAC, the private sector has made efforts to engage more effectively with local stakeholders and communities, for instance through multi-stakeholder initiatives and dialogues (OECD, 2022[66]; OECD, 2022[65]).

Promoting integrity and avoiding policy capture

Undue influence exerted by the private sector can act as a major barrier to advancing the green transition. Indeed, conduct by businesses in the political arena, or what is known as corporate political activity, can have an impact on policy direction and outcomes (Zinnbauer, 2022[68]). Some companies may have an interest in capturing policy making to delay or limit the changes it will bring about, with the ultimate objective of preserving the status quo and protecting their market power. For instance, power and energy are two sectors with strong vested interests in blocking potentially disruptive developments. Incumbents in these sectors often have significant political influence at the top levels of decision-making circles and are particularly prone to political corruption (Arent et al., 2017[25]). In LAC, there is a general widespread perception of policy capture by powerful elites; 73% of the population in 2020 believed that their country was run to the benefit of a few. In Argentina, Chile, El Salvador, Guatemala and Peru, the private sector was seen as holding the most power in the country, ahead of the government (Latinobarometro, 2021[9]).

Stronger regulations to promote integrity and accountability in the private sector are fundamental to a successful green transition. Lobbying and political finance regulations can ensure greater integrity. Relevant issues regarding lobbying include: strengthening the transparency and integrity of corporate interest representation; increasing the transparency of funding, membership composition and decision-making practices in the lobby target-setting adopted by lobbying and business associations; and supporting development and adoption of good practice principles, such as the 2010 OECD Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying. Several LAC countries including Argentina (2003), Colombia (2011), Chile (2014), Mexico (2010) and Peru (2003) have adopted lobbying laws or regulations. Chile, Colombia and Mexico have lobbyist registers; among these, Colombia does not impose sanctions for non-compliance. Only four countries (Argentina, Chile, Mexico and Peru) require that the agendas of public officials be made public and five countries (Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico and Peru) require the disclosure of names of members of permanent advisory bodies (OECD, 2020[69]).6 Early observations confirm that countries with a regulatory framework to enhance the transparency of lobbying activities and policy making generally ensured a greater degree of accountability in policy decisions during the COVID-19 crisis (OECD, 2021[70]).

Political finance regulation is strongly regulated in LAC, with the exception of some countries in Central America (International IDEA, 2020[71]). However, an implementation gap persists: in 11 of 12 countries surveyed, cash contributions were still allowed in 2018, making it easier to circumvent political finance regulations. Moreover, digital technologies and social media are creating “grey areas” that make tracking digital advertisements for political parties and candidates more complex (OECD, 2021[70]).

As lobbying, political finance, corporate governance and, more broadly, RBC are increasingly connected, better co-operation is needed among experts, practitioners, regulators and advocates in these domains. Interlinking data streams through harmonised data frameworks and common identifiers is among measures that could help policy makers better monitor the influence of business in the policy-making process. The ability to triangulate disclosures made by politicians, businesses and lobbying associations on their activities could significantly increase transparency and accountability (Zinnbauer, 2022[68]).

A strategic view of the green transition: Preparing public institutions

Many LAC countries’ constitutions such as Argentina, Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru and Venezuela already recognise the right to a healthy environment but, in practice, this may be difficult to enforce (UN, 2022[55]). Moving the green agenda forward will require institutions to evolve accordingly and to be ready to address the numerous challenges this will bring. A high level of co-ordination will be necessary to design and implement a systemic green transition (Chapters 2 and 3). An integrated vision of this transition will facilitate reaching consensus around green policies while reconciling diverging views and interests (Section on political economy). In practical terms, this integrated vision will be essential to co-ordinate actions across sectors and levels of government, and will provide a coherent approach that can guide actions and delivery mechanisms throughout the process.

Policy coherence and multi-level governance

Achieving a holistic green transition will require enhancing policy coherence for sustainable development across levels and sectors of government. Given the complex interconnections among economic, social and environmental challenges, policy coherence can help policy makers better understand the impacts and spillovers of policies.

Policy coherence has three main objectives (Soria Morales, 2018[72]). The first is to help foster synergies and minimise trade-offs across sectors. For instance, an increase in agricultural land use could undermine efforts in halting biodiversity loss and preserving terrestrial ecosystems. In contrast, fostering sustainable agricultural practices can help increase food sovereignty while supporting water use efficiency targets, especially as agriculture is the major user of the world’s freshwater withdrawals.

The second is to help reconcile local, regional and national policy objectives with internationally agreed objectives and avoid fragmented responses. Most policies and objectives related to climate change and sustainable development are a responsibility shared across levels of government or are critically dependent on local actions. It is therefore important to foster co-ordination and alignment of objectives.

The third is to address the transboundary and long-term effects of policies. In particular, informed choices about sustainable development need to consider the long-term impact of policy decisions on the well-being of future generations.

Effective and inclusive institutional and governance mechanisms are important in addressing policy interactions (OECD, 2021[73]). The nature of wicked problems, such as climate change, demand a co-ordinated centre of government (CoG), able to provide horizontal and comprehensive responses that include as many key actors as possible. To ensure their long-term outcome, horizontal green policies should be enhanced across various ministries (e.g. planning, finance, environmental and social ministries) but also with key stakeholders inside and outside public institutions.

Policy co-ordination and coherence in green policies must also occur vertically, among the CoG, subnational governments, municipalities and their main stakeholders. This allows the CoG to oversee high-level co-ordination mechanisms and take an active role in aligning multi-department work plans with clear mandates and resources, ensuring that activities align with government priorities. Moreover, it could avoid policy duplication and overlap and respond to citizens’ growing demands for better service delivery. It could also generate cost reductions and positive synergies, e.g. in dealing with issues such as service provision. For instance, water governance can be most effective when looking at hydrological instead of administrative boundaries (e.g. river basin management).

Beyond political short-termism: Linking policy instruments and long-term plans for the green transition in LAC

Climate change and the green transition are complex issues requiring substantial planning and investments. However, as the short-term costs of these actions could be more evident than their long-term benefits, governments are often constrained by public opinion and short-term political cycles, as well as by vested interests, which can derail policies to address these complex, longer-term challenges. It is therefore important that governments have a long-term vision to articulate their actions, such as National Development Plans (NDPs) and strategies, as well as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), climate strategies, defined policies, regulations and sector plans to underpin their pledges (see Annex Table 5.A.1 in Annex 5.A1).

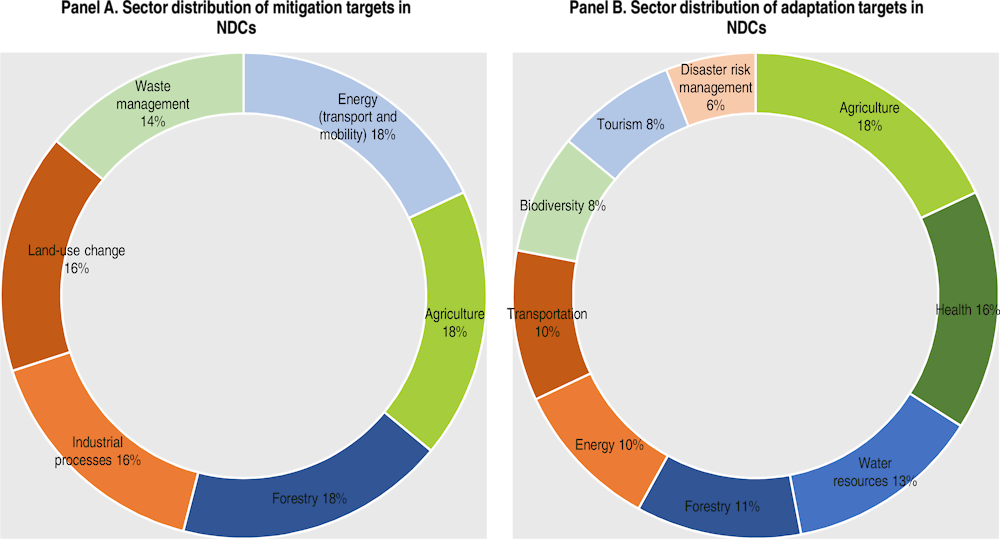

Nationally Determined Contributions: Overview of main priorities with regard to the green transition

LAC governments are aware of the requirement to transition to a greener society. This is why, in 2015, in accordance with the Paris Agreement, several LAC countries committed to developing their own NDC plans, i.e. climate action plans to cut emissions and adapt to climate change impacts. These documents provide information regarding mitigation targets, adaptation actions and economic diversification plans, with the primary objective of reducing GHG emissions to limit global warming to below 2°C – preferably to below 1.5°C – compared to pre-industrial levels by 2030. Countries also developed National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), which are flexible processes that build on each country’s existing adaptation activities, helping integrate climate change into national decision making.

NDCs and NAPs allow countries to establish concrete targets, measures and policies allowing stakeholders from all sectors and institutions to contribute from their specific technical and budgetary capabilities and setting the basis for national climate action plans. These platforms also allow countries to co-ordinate whole-of-government approaches by committing to targets that are more ambitious and that help pivot away from imposed top-down targets towards self-determined, bottom-up pledges. The projected impact of NDCs and NAPs can be aggregated to show where LAC governments stand in relation to climate goals and to highlight institutional and financial needs at the ground level. Article 13 of the Paris Agreement also establishes an Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF) under which countries are required to communicate progress in the implementation of their NDCs.

Even though early adoption and implementation of the NDC framework has led to some ambitious decarbonisation plans in LAC countries, as well as to considerable advances in the energy and transport sectors, there is still a long way to go in terms of implementation. As some countries submit the second iteration of their NDCs, the main challenge is to transform these ambitious objectives into measurable results (Cárdenas, Bonilla and Brusa, 2021[74]). Out of the selected 14 LAC countries analysed in this section, only the Dominican Republic, Panama and Peru have proposed or developed a national monitoring system to track the effective implementation of their commitments. For instance, Panama’s National Climate Transparency Platform aims to facilitate the collection, management and dissemination of climate-related data in a consultative and transparent manner (Wetlands International, 2021[75]).

Of the countries analysed, 12 had submitted an update of their NDCs by April 2022 (Table 5.2), primarily strengthening their targets and monitoring methodology. Updates from Ecuador and Uruguay are pending; as they submitted their first NDCs in 2019 and 2017, respectively, they are still under the five-year renewal commitment. Most countries in the Caribbean have submitted updated NDCs, apart from the Bahamas and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Trinidad and Tobago submitted its first NDC in 2018 and thus remains in the five-year renewal commitment.

Regarding total GHG emission reduction targets committed to by LAC countries in their NDCs, comparison is not straightforward, given the difference in baseline scenarios and reference years employed. Costa Rica’s 2020 NDC update is among the few that are rated 2°C compatible (CAT, 2020[76]). By contrast, despite a 50% GHG emission reduction target by 2030 with respect to 2005 (Figure 5.9), Brazil’s 2020 and 2022 NDC updates allow higher emissions than the 2016 NDC (Unterstell and Martins, 2022[77]; CAT, 2022[78]). Mexico’s 2020 NDC update also decreased its emission reduction ambition with respect to the 2016 NDC (CAT, 2020[79]).

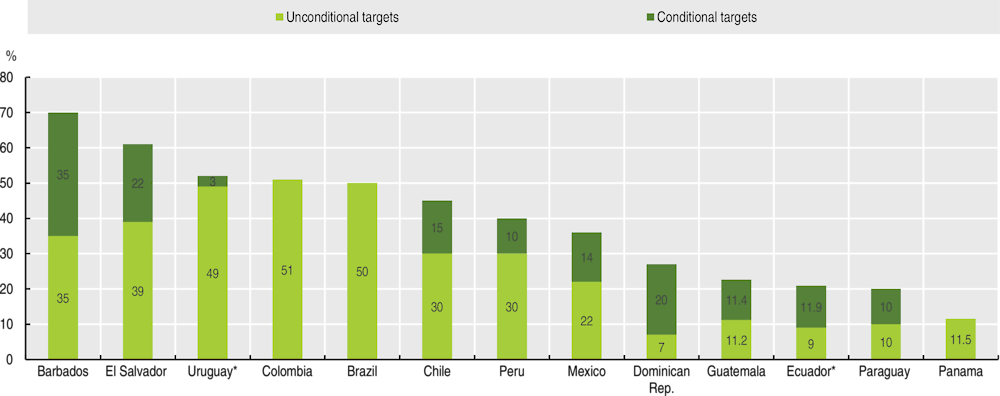

While Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica and Panama established only unconditional targets, the majority of countries also set conditional targets – i.e. commitments that directly depend on the delivery of international funding (Chapters 4 and 6) (Figure 5.8). The latter is especially true for some heavily-indebted Caribbean countries that are currently struggling with the negative effects of climate change. For instance, the Barbados’ 2021 NDC update commits to a GHG emission reduction target of 35% relative to business-as-usual emissions in 2030 without international support (unconditional), which could increase up to 70% with international support (conditional). Similarly, given that the intensity and frequency of climate change impacts are above the ability of the country to adapt, the sectoral targets set in the NDC of Antigua and Barbuda are entirely contingent upon receiving international support for technology transfer, capacity building and financial resources, with an estimated cost of around USD 1-1.7 billion (United States dollar) (UNFCCC, 2021[80]).

Figure 5.8. For many LAC countries, achieving the most ambitious emission reduction targets depends on external funding

*Ecuador and Uruguay targets refer to 2025, not 2030.

Notes: Total GHG emission reduction targets correspond to the sum of unconditional and conditional targets. Argentina and Costa Rica did not officially set a relative target. Antigua and Barbuda did not officially set an economy-wide GHG emission reduction target in its updated NDC.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on countries’ NDCs.