The COVID-19 recovery in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is slowing down, reflecting low potential growth and an increasingly complex international context driven by Russia’s war against Ukraine and an economic slowdown in China. The socio-economic consequences of COVID-19 linger, with poverty and extreme poverty still high. With macroeconomic policy space being reduced, most LAC countries will face the multidimensional challenge of balancing recovery stimulus, financing the green transition, and protecting the most vulnerable, particularly from the impact of inflationary pressures. After analysing the global context, this chapter presents the economic performance and critical factors affecting the pace and shape of the recovery in LAC. The chapter then analyses the weight of climate change on fiscal accounts and explores some options to mobilise further resources to promote the green transition. Before concluding, the chapter discusses the deteriorated post-COVID-19 social conditions, particularly poverty and inequality, and the need to strengthen social protection systems.

Latin American Economic Outlook 2022

Chapter 1. Addressing the structural macro context to drive the green transition

Abstract

Addressing the macroeconomic challenges of LAC to ensure a green and just transition (infographic)

Introduction

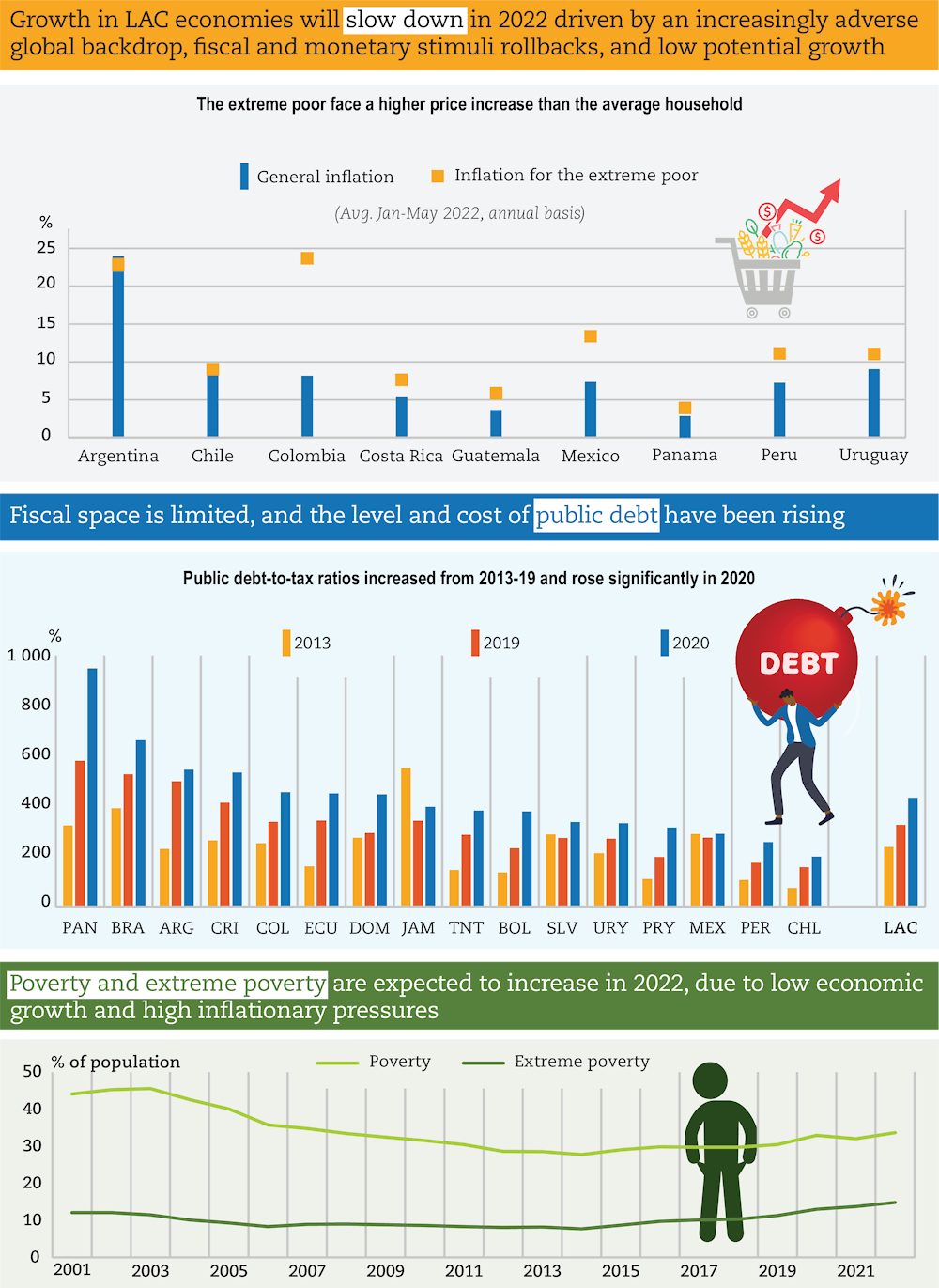

Following a robust economic rebound in 2021, growth in LAC economies will slow down in 2022. This is driven by an increasingly adverse global backdrop, fiscal and monetary stimuli rollbacks, and low potential growth. Inflationary pressures are mounting, and most central banks in the region are raising policy rates.

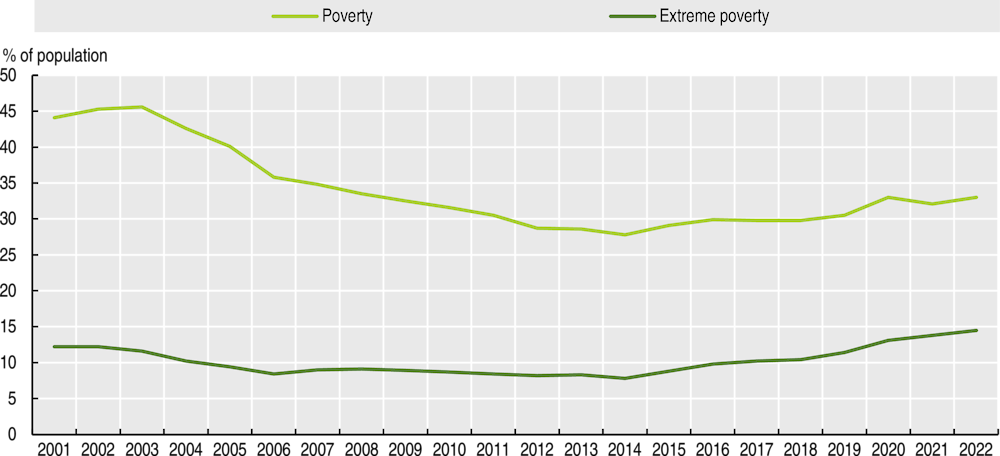

Social challenges from the pandemic remain, with an expected increase in poverty in 2022. Even though there was a decrease in total poverty levels between 2020 and 2021, these are projected to increase in 2022 due to rising inflation, especially in food prices. Extreme poverty did not recede in 2021 and is expected to increase in 2022. It is estimated that, by 2022, 33.7% of the LAC population will be in poverty and 14.9% in extreme poverty (ECLAC, 2022[1]). This has translated into downward mobility in the socio-economic stratum. The incidence of poverty is heterogeneous not only among countries in the region but also among population groups. For instance, women aged 25 to 39 have higher poverty rates than men of the same age in all countries. Inequality in income distribution has also increased in most countries, with current high inflation posing a risk of a further increase (ECLAC, 2022[2]).

With restrictive monetary conditions, fiscal policy management is at the recovery’s core. As in other regions, inflation rates have increased substantially; therefore, most central banks have responded appropriately with interest rate increases. Since the end of 2021, many of the region’s economies have started to withdraw some fiscal stimulus, and tax revenues have increased thanks to the improvement in economic conditions, thus narrowing primary fiscal deficits. LAC economies must support economic conditions and fiscal sustainability, while protecting the most vulnerable through strengthening social protection systems. In the future, climate change and the green transition can weigh heavily on fiscal accounts as natural disasters, the phasing out of fossil fuels from the energy matrix, or stranded assets can diminish revenues. Therefore, the region will need to mobilise resources to compensate for shortfalls and to invest more, better and greener to reduce the adverse effects of climate change and finance the green transition. A green transition goes beyond fighting climate change. It also aims to advance a more sustainable and inclusive model of production and consumption that creates new, quality, green jobs, generates the conditions for workers to successfully navigate the transition, and supports firms to adopt more sustainable production schemes and citizens to change their consumption habits (Chapter 2).

Global economic prospects are weakening stemming from the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation (hereafter “Russia”) and the lingering effects of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and strategies to contain it. The impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will vary across regions, depending on their commercial and financial exposure to Russia or Ukraine. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has also pushed up commodity prices, fuelling inflation. Disruptions in global supply chains, high freight costs, and demand and supply imbalances have contributed to the build-up of inflationary pressures not seen in decades and that go beyond food and energy. Similarly, the zero-COVID policy of the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) continues to weigh on the global outlook and trade flows (OECD, 2022[3]; OECD, 2022[4]).

This chapter first examines the global context, focusing on the consequences of Russia’s war against Ukraine and the growing inflationary pressures. It then presents the economic performance in LAC, highlighting the region’s heterogeneity, external accounts, growing inflationary pressures, and tight fiscal space, especially to finance the green transition and face the adverse effects of climate change. Last, the chapter examines the remaining social consequences of the COVID-19 crisis, focusing on poverty and inequality, the nexus with inflation, and the importance of strengthening universal, comprehensive, sustainable and resilient social protection systems.

An increasingly challenging global context

After the strong recession generated by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the global economy grew at a robust pace in 2021, supported by the advance of vaccination programmes and the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus packages applied by most countries. The economic rebound of 2021 was widespread, with an estimated global growth of 5.8%, much higher than the contraction of 3.4% reported in 2020 (IMF, 2022[5]; OECD, 2022[3]; OECD, 2022[4]).

In 2022, global economic growth has slowed due to deteriorating global conditions, fuelled by the war in Ukraine and the lingering effects of COVID-19, mostly China’s zero-COVID policy. Russia’s war against Ukraine impacted global recovery. Before the outbreak of the war, global growth was projected to return to rates similar to those prevailing before the pandemic, and inflation was seen as a temporary phenomenon. China’s zero-COVID policy has similarly affected the global outlook by creating bottlenecks in international trade and adding to inflationary pressures. Estimates suggest that for 2022 global growth could slow to around 3.0%, and 2.2% in 2023 (OECD, 2022[3]; OECD, 2022[4]).

The impact of the war will vary across regions, depending on their ties to Russia and Ukraine, their main trading partners, their export basket, and their financial exposure. In Emerging Asia, the impact will likely be less acute, as the economic ties with the countries involved in the war are not very strong. Africa also has relatively small investment ties with Russia and Ukraine. Still, Russia’s large-scale aggression against Ukraine will significantly affect its major trade and investment partners, along with the inflationary pressures already causing a food crisis. In LAC, the war can have diverse and significant impacts, although mostly indirectly through higher commodity prices, slow global growth, disruptions in trade, and financial volatility.

For the global economy, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the slowdown in China have at least three relevant channels of transmission

The first channel is an increase in energy and food commodity prices. Considering the importance of Russia in the global energy commodity market, Russia’s war against Ukraine pushed up prices amid pre-existing supply and demand imbalances (Figure 1.1).

In the case of Russia’s war against Ukraine, geopolitical risk and uncertainty from the application of potential larger-scale sanctions have fuelled volatility in global energy markets (Box 1.1). As a result of uncertainty, prices of oil, gas, coal and industrial metals soared in March 2022, and fluctuated around higher levels over the next few months. Energy prices have remained elevated, but a weaker demand from China has eased some of the pressures on metal prices (OECD, 2022[4]).

Beyond energy, the price of food raw materials has further risen due to the disruption of essential trading channels in the cereals and fertilisers segments. Ukraine and Russia contribute 30% of the wheat sold globally and are relevant corn, oats and sunflower producers. Belarus (Ukraine’s border country) and Russia are important exporters of potassium and phosphorus worldwide, minerals that are critical inputs to produce fertilisers used in multiple crops. The agreements that allowed some agricultural exports from Ukraine have helped to ease food price pressures (OECD, 2022[4]).

The increase in commodity prices will weaken the post-pandemic economic recovery by accelerating inflation. Energy and food inflation directly affects the purchasing power of households, limiting private consumption spending, trade, and global growth as well as generating social tensions.

Figure 1.1. Commodity prices

Note: Crude Oil BFO M1 Europe. Soybeans, No.1 Yellow USD/Bushel. LME-Copper Grade A Cash USD/MT. Data accessed 7 October 2022.

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Box 1.1. Could a total embargo on Russian oil shipments lead to a global economic crisis?

At the time of writing, the oil price had risen more than 20% since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, primarily driven by expectations of a drop in Russian crude availabilities rather than effective supply disruptions linked to sanctions. The current economic scenario is reminiscent of the oil crisis of 1973-74 when the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) decided to suspend the sale of crude oil to the United States for its military support to Israel during the Arab-Israeli war. The price of oil quadrupled, causing inflation to rise sharply and central banks to raise interest rates sharply, giving way to a major global recession.

Although a Russian oil crash may have profound inflationary impacts, with severe effects on domestic demand on a global scale, it seems unlikely it will generate a global recession as the one observed almost half a century ago. This is due to the more efficient use of oil that the advanced economies of the West have developed, which translates into less dependence on this raw material.

The global industry has a much lower dependence on oil than in the 1970s. In 1973, for example, the world used about one barrel of oil to produce USD 1 000 of gross domestic product (GDP) (2015 prices) (Ruhl and Erker, 2021[6]). In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, the intensity of oil use had fallen to 0.43 barrels by the same magnitude of global GDP (-56%). Additionally, today there is a more diversified matrix of energy sources, where oil generates about one-third of the world’s energy compared to 53% at the beginning of the 1970s, having ceded space to biofuels and nuclear reactors.

Another no less important element is the development of the fracking industry in the United States in recent years, which has allowed it to improve its oil trade balance. Thus, while harming consumer spending, an oil price shock such as the current one also benefits domestic producers. An energy matrix less dependent on oil and a broader range of producers makes the global economy less vulnerable to abrupt disruptions in crude oil supply and energy price shocks.

The second channel is the disruption of world trade. While, in general, the share of Russia and Ukraine in global trade and production is relatively small, they are critical suppliers of inputs to certain industrial value chains. Russia is one of the world’s leading producers of palladium (26% of global imports) and rhodium (7% of global imports), which are inputs for producing catalytic converters for automobiles. Ukraine supplies more than 90% of the neon used in making lasers used to manufacture American micro-chips. Possible disruptions in the supply of these raw materials could aggravate the supply of semiconductors for the electronic equipment and car industries, worsening the critical shortages observed in these sectors since the beginning of the pandemic. Similarly, Russia and Ukraine together account for about 30% of global exports of wheat, 15% of corn, 20% of both mineral fertilisers and natural gas, and 11% of oil. In the case of China, trade disruptions have arisen as a result of the impact of the strict zero-COVID strategy. In Shanghai and other big cities, the policy has created labour shortages, which affects transport capacity, slows operations in ports and reduces air traffic (OECD, 2022[3]).

The third channel is an increase in financial volatility. Since Russia’s large-scale aggression against Ukraine, global capital markets have experienced high volatility, with an initial plunge on 24 February 2022 and a rebound in the following weeks. The Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index, a proxy of the standard market volatility in international capital markets, reached its highest peak of 2022 in March and has remained relatively high, although still considerably below the volatility seen in 2020 due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Overall, the impacts of Russia’s war against Ukraine and China’s economic slowdown on global capital markets have been more moderate than the pandemic’s. However, as central banks have responded to above target inflation rates, financial conditions have tightened and capital outflows from emerging-market economies have intensified (OECD, 2022[4]).

Central banks are reacting to growing inflationary pressures not seen in decades

One of the main economic policy challenges of Russia’s war against Ukraine is soaring commodity prices, further fuelling inflation. Disruptions in global supply chains, high freight costs, and demand and supply imbalances contributed to the build-up of inflationary pressures not seen in decades. China’s zero-COVID policy can add to inflationary pressures via producer prices (OECD, 2022[3]; OECD, 2022[4]).

Central banks in major economies initially assessed this rise as transitory. However, it has persisted much longer than originally anticipated by authorities, leading to an unexpected global inflationary scenario. In the United States, inflation reached 8.6% year on year in March 2022 – a 40-year high. For some advanced economies, May 2022 had the highest level of inflation. This was observed in the Eurozone, with inflation reaching around 8.0%, Canada (around 7.7%) and the United Kingdom (above 9.0%), where headline and core price growth has already far exceeded the respective official inflation targets.

The main risk of this prolonged deviation of inflation from the target is the de-anchoring of medium- and long-term inflation expectations. Central banks in developed economies are accelerating the speed of monetary policy normalisation by reducing asset purchases and increasing interest rates from historical minimum levels.

The first major central bank to move forward with interest rate normalisation was the Bank of England, raising its benchmark rate from 0.10% to 0.25% in December 2021 and it has since then increased it up to 1.75%. In March 2022, the US Federal Reserve began its cycle of interest rate hikes, applying the first increase of the Fed Funds Rate in four years, from 0.50% to 0.75%. Raising interest rates has continued. In June and September 2022, the US Federal Reserve approved hikes of 0.75 basis points up to 2.37, the largest since 1994 (OECD, 2022[4]).

The European Central Bank (ECB) has also been taking measures towards monetary normalisation, mostly as this region is more directly exposed to Russia’s war against Ukraine. In March 2022, the ECB announced that the pandemic emergency purchase program would come to an end and that it would gradually reduce its debt purchase until the end of June. In July 2022, the ECB raised its key interest rate by half a percentage point, the first increase in over a decade. Similarly, it implemented the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) to ensure that the monetary policy stance is transmitted smoothly across all euro area countries.

Although many emerging economies, particularly in Latin America, have advanced in the withdrawal of monetary COVID-19 stimuli since last year, emerging markets will face challenges as interest rate hikes continue in advanced economies. Higher interest rates may pose risks to highly indebted households and companies, compromising the banking sector (IMF, 2022[5]). Moreover, following the pandemic-related sharp increase in public debt, higher interest rates could threaten sustainability, particularly in countries experiencing lower growth.

The recovery in Latin America is slowing down, reflecting low potential growth

LAC had a strong rebound in 2021. GDP growth in LAC rebounded to above 6% in 2021, driven by fiscal stimulus, more favourable external conditions and the acceleration of the region’s vaccination campaigns, which allowed the economies to reopen. This happened after the region registered one of the most severe output contractions (6.9%) globally in 2020, causing poverty and inequality to rise. However, the recovery was uneven. While several countries regained pre-pandemic GDP levels, decreasing tourism flows and limited fiscal space for stimulus constrained a fuller comeback in the Caribbean and Mexico (ECLAC, 2022[1]).

In 2022, a slowdown in LAC growth is expected as external conditions deteriorate, reopening effects dissipate, and local authorities roll back fiscal and monetary stimuli. The rapid convergence to modest expansion rates reflects low potential growth. Projected economic growth in the region will be insufficient to revert the increases in poverty and inequality accentuated by the pandemic. Inflationary pressures have prompted central banks to increase interest rates since 2021, and the tightening cycle will continue while inflation rates remain above central banks’ targets. Fiscal deficits will narrow in 2022 as governments withdraw spending and activity stabilises. However, debt levels will remain high, and further consolidation efforts might be needed in the medium term to recover fiscal space and debt sustainability. Risks to this outlook stem from a steeper and faster-than-anticipated tightening of financial conditions, new waves of the pandemic, longer-lasting disruptions in global supply chains, political uncertainty in the region, and the repercussions of both Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s economic slowdown.

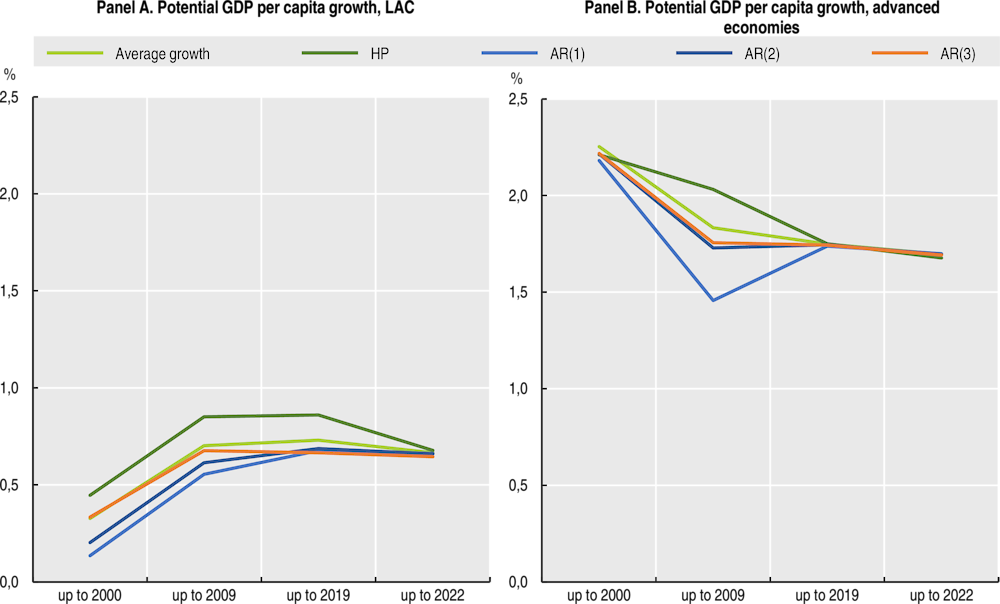

Potential growth, a pre-pandemic structural challenge in LAC, remains stagnated at low levels. Moreover, regardless of how potential growth is calculated, it has weakened. Potential GDP per capita growth has been below 1% since 1980, slightly increasing following the commodity boom (between 2003 and 2013). Since then, per-capita potential output growth has stagnated. Furthermore, potential GDP per capita growth remains below advanced economies, hindering convergence. Over the last decades, the per-capita GDP gap between LAC and advanced economies has narrowed, but gains stopped after 2015 as potential regional output faltered (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Potential GDP per capita growth in LAC and advanced economies, estimated under different methods

Notes: AR = autoregressive model, which uses GDP per capita growth data. The number of lags (1 and 2) was determined by analysing the autocorrelation function and choosing the model that maximised the log-likelihood. HP = the Hodrick-Prescott filter, which was used as an alternative model due to its resilience to short-term shocks to create a smoothed curve (lambda 100). The LAC series refers to the 33 countries covered by the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database, October 2022.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on (IMF, 2022[5]).

Overall effects on LAC of Russia’s war against Ukraine and China’s slowdown remain uncertain and are transmitted through three main channels

The first channel is the effect of higher commodity prices on external accounts. The reduced exposure to Russia and Ukraine limits the direct impact on trade in the LAC region, which does not exceed 1% of the region’s total trade. Only Ecuador (4% of total trade) and Paraguay (8% of total trade) exhibit a more significant exposure to trade with Russia. From the point of view of investment flows, Russia’s involvement in the region is shallow, except for participation in some energy projects in Brazil and Mexico. Therefore, the main impact of the crisis on the LAC region is through the terms of trade because of increases in the prices of energy and some agricultural raw materials.

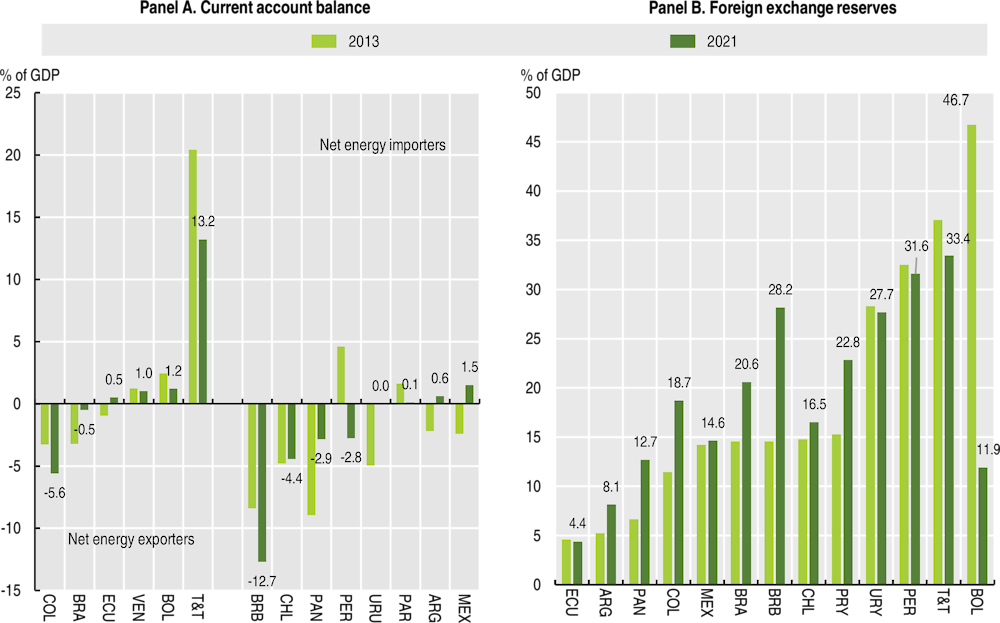

The outcome depends on whether countries are net exporters or importers of energy and food. Net exporters in South America benefit from more favourable terms of trade, improving current account balances, and generating additional fiscal revenues that may stimulate demand and, consequently, growth and employment. Nonetheless, the improvement in the terms of trade may not be significant because of the accumulated increases in imported input prices due to the disruptions in global supply chains. Central American and Caribbean countries experience the opposite effects (Figure 1.3, Panel A). Similarly, the economic slowdown experienced by China and globally affects the trade channel, particularly in economies such as Brazil, Chile, Peru and Uruguay, where China is a crucial trading partner. Negatively affected countries, such as Chile, Panama, Paraguay and Peru, have sufficient international reserves to face the transitory negative shock (Figure 1.3, Panel B) and maintain access to global financial markets at relatively low costs.

Figure 1.3. Current account deficits and international reserves

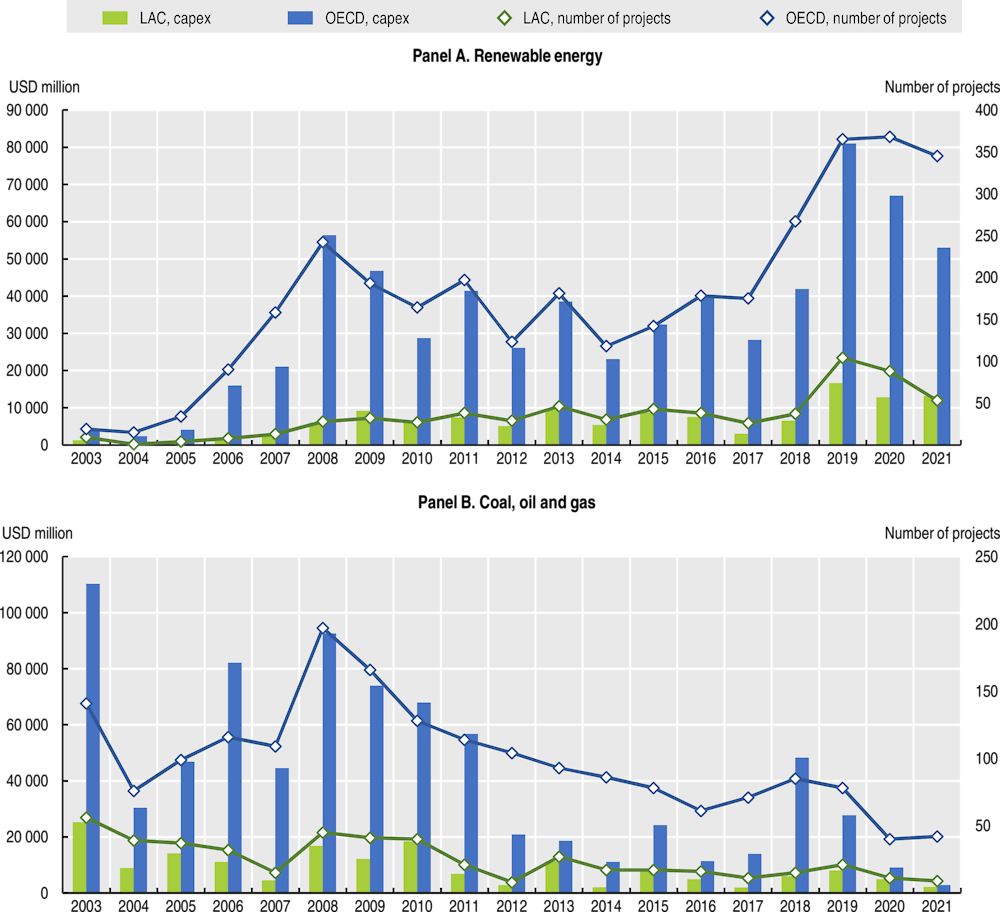

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is essential to finance current account deficits and the green transition. FDI inflows experienced a 56% increase in 2021 (reaching USD 134 billion) after the substantial fall (45%, USD 86 billion) experienced in 2020 (UNCTAD, 2022[7]). Quality FDI can contribute to increasing productivity and deliver a more sustainable recovery and attain decarbonisation goals (OECD, 2019[8]; OECD, 2021[9]; OECD et al., 2021[10]). In terms of decarbonisation and similar to the OECD, FDI on renewable energy reached its peak (both in USD and number of projects) in 2019 and has not yet recovered. Nevertheless, it remains above the pre-2019 levels. In LAC, FDI on renewables remains above the levels invested in oil coal and gas (both in USD and number of projects) (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. LAC and OECD FDI investment in renewable energy and in coal, oil and gas, LAC

Notes: Countries included are Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Saint Lucia, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Source: Financial Times’ fDi Markets database.

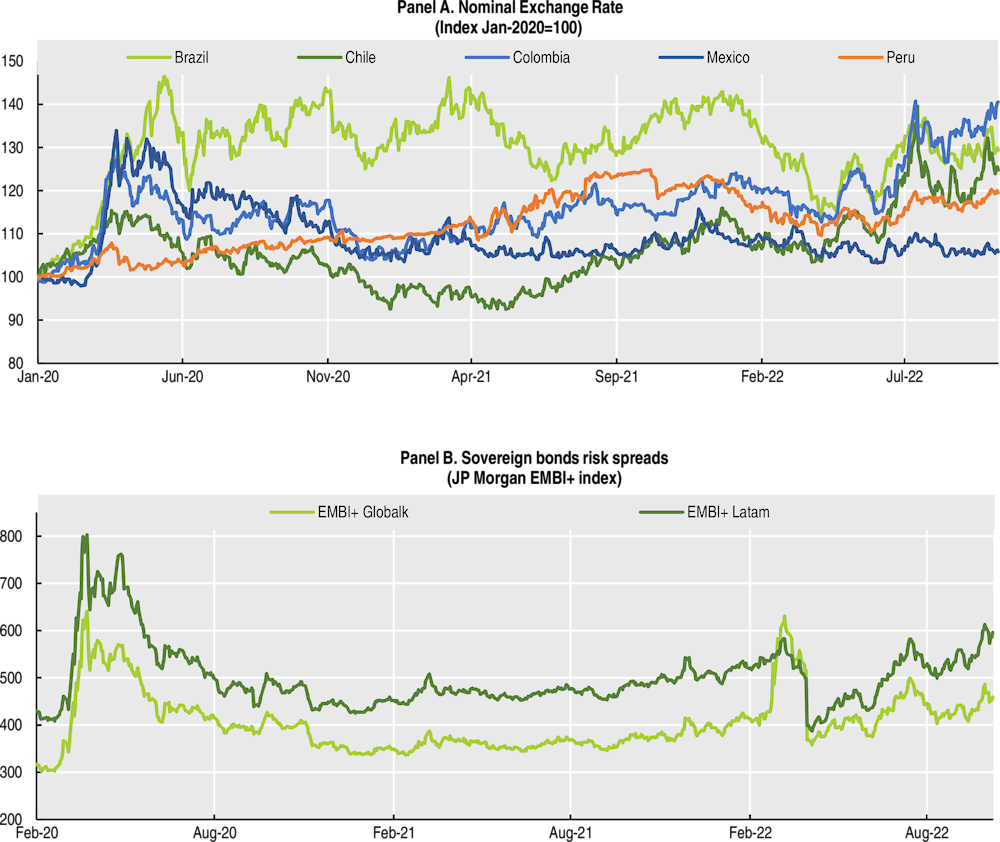

The second channel of transmission is through international financial markets. In addition to the shock in markets generated by the Russian war against Ukraine, other factors including the normalisation of monetary policy in advanced economies, and specific domestic aspects within LAC countries affected capital markets’ behaviour. Between March 2022 and October 2022 risk premia increased, although they remain below the levels seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, during the same period, most local currencies have depreciated (Figure 1.5), with the exception of some economies such as Mexico where it has appreciated. Exchange rate depreciations in most LAC countries follow a trend that precedes the war, and recently is a combination of domestic and external factors, including increases in inflation rates.

Figure 1.5. Nominal effective exchange rate and sovereign bond spreads

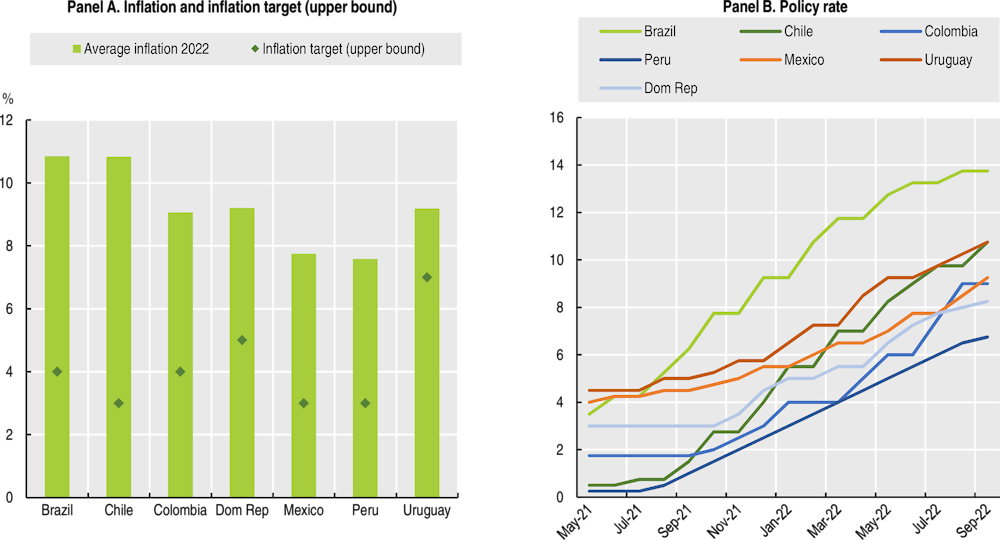

The third channel is the intensification of inflationary pressures. First, the pandemic and its recovery disrupted trade and caused supply bottlenecks, input shortages and increases in transport costs and commodity prices (IMF, 2022[11]). In addition, the war has exacerbated the rise in commodity prices in most LAC countries. As a result, inflation in 2022 has been above the policy target in LAC economies (Figure 1.6, Panel A). In Chile for instance, inflation has risen to a 30-year high (OECD, 2022[12]). Before Russia’s war against Ukraine, the price rise (Figure 1.6, Panel B) had already prompted central banks across LAC to increase interest rates to anchor expectations. As inflationary pressures mount due to the increase in commodity prices, and the US Federal Reserve hikes rates, this process will be difficult to reverse. The marked rise in energy and food prices reduces the purchasing power of households, particularly the more vulnerable, still reeling from the effects of the pandemic. This does nothing to reverse the increase in poverty and inequality in the region, already hampered by the projected weaker economic growth.

Monetary policy should consider and align with climate goals and policies. Different climate policies have distinct implications for the price system, for instance a fixed carbon price can affect price fluctuations (Chen et al., 2021[13]). Similarly, incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into central bank mandates will be critical to efficiently safeguarding price and financial stability given the high-level impact that climate risks could have on the traditional core responsibilities of this institution. Central banks in LAC can share and learn from experiences with other central banks. The ECB aims to monitor the financial system, including private banks, so that the risks from climate change are included (ECB, 2021[14]).

Figure 1.6. Inflation and policy rates in inflation targeting in selected LAC economies

Note: Data are from January to August 2022 (Panel A) and from January 2021 to September 2022 (Panel B).

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream and official sources.

Low fiscal space to navigate the challenging context

To cope with the COVID-19 crisis, public expenditure in LAC reached a historic high of 13.6% of GDP in 2020 at the central government level, an increase of 2.3 percentage points compared to 2019. This level was even higher than that seen during the last economic crisis in 2008, when the increase was 1.1 percentage points (ECLAC, 2022[2]). Social spending is the main component of total public spending (ECLAC, 2022[2]). The countries that stand out for the largest increases in 2020 (with respect to 2019) are Brazil and El Salvador (5.3 percentage points of GDP) and Argentina, Barbados and the Dominican Republic (between 4.2 and 4.6 percentage points of GDP) (ECLAC, 2022[2]).

In 2021, LAC economies started to withdraw the fiscal stimulus and revenues increased with the economic recovery; therefore, primary fiscal deficits for the central government have been narrowing. On average, deficits reduced to 4.2% of GDP in 2021, an improvement of 2.7 percentage points from 2020. Tax revenues increased in 2021 thanks to strong GDP growth, while spending fell as LAC economies reduced emergency transfers (ECLAC, 2022[15]). This came after a drop in tax revenues of 0.8 percentage points in 2020 relative to 2019. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in historic falls in both nominal tax revenues and nominal GDP, with taxes falling more sharply than nominal GDP. There is still some fiscal stimulus related to the pandemic, as current expenditure remains above 2019 levels (IDB, 2022[16]; OECD et al., 2022[17]).

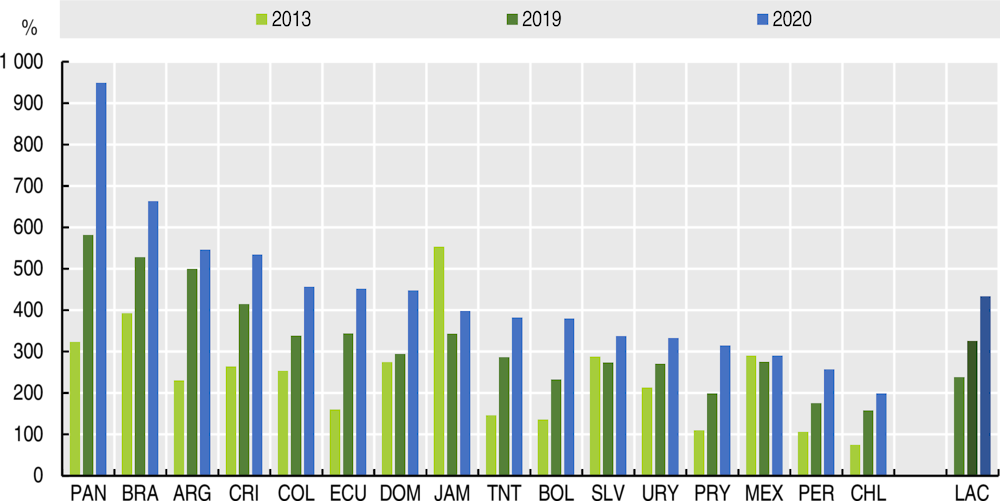

Even though the 2021 recovery helped relieve some of the pressure on fiscal accounts, structurally tight fiscal space in LAC still needs to be addressed. Public debt-to-tax ratios, a proxy indicator of countries’ financial capacity to pay for public debt, were higher in 2019 than in 2013 and increased significantly in 2020 (Figure 1.7).

Tax revenues remain low in LAC. In 2020, the average tax-to-GDP ratio was 21.9% of GDP compared to 33.5% in the OECD. As a result, the gap between the LAC and OECD tax-to-GDP ratios widened to 11.6% of GDP in 2020 from 10.7% in 2019 (OECD et al., 2022[17]). The gap is mainly explained by the region’s low revenues from income taxes and social security contributions relative to the OECD average. The combined share of taxes on income and profits (especially personal income taxes) and social security contributions was much lower in the LAC region than in the OECD (44.1% versus 60.0% in 2019, on average).

Figure 1.7. Gross public debt-to-tax ratio in selected Latin American countries

After a substantial increase in 2020, LAC debt declined in 2021. Debt stood at 53.7% of GDP in 2021, below the 56.5% registered in 2020 (ECLAC, 2022[15]). The economic recovery and rising inflation helped reduce debt, despite fiscal deficits. Notwithstanding, volatility in the financial markets, rising debt costs, and the need to finance the green transition highlight the necessity for adequate, proper fiscal frameworks (including fiscal rules) and globally co-ordinated debt management under key guidelines (Chapter 4) (OECD et al., 2021[10]; Arreaza et al., 2022[19]).

Going forward, LAC economies must support economic conditions and fiscal sustainability, particularly in the face of rising food inflation, financing the green transition, while protecting the most vulnerable through strengthening social protection systems. The composition of the fiscal consolidation, the timing and the balance between capital and current expenditure will play important roles in the shape and inclusiveness of the recovery. If public investment is safeguarded, relative to current expenditure, it can neutralise the contractionary effects of fiscal adjustment in the short run and might stimulate growth in the medium term (Ardanaz et al., 2021[20]). In the short term, the focus should remain in protecting the most vulnerable against rising inflation.

With a tight fiscal space and with high debt levels, countries in the region will need to face the growing negative effects of climate change and finance the green transition. Fiscal efforts should develop comprehensive frameworks that combine decarbonisation and resilience strategies with the promotion of growth and social inclusion (D’Arcangelo et al., 2022[21]).

Natural disasters weigh heavily on fiscal sustainability

Climate change is already challenging fiscal sustainability when natural disasters strike. The frequency of natural disasters in the region has increased over the last decades. An average of 17 hurricanes per year and 23 category-5 hurricanes in total were recorded between 2000 and 2019, mostly affecting Caribbean and Central American countries (OCHA, 2020[22]).

Other natural disasters, such as floods, wildfires and droughts, are common in LAC. They have severely affected the whole region, with flooding and wildfires being the most common events in South America’s Southern Cone. Drought affects the largest number of people in the region, with crop yield reductions in 2018 of between 50% and 75% in eastern El Salvador, central and eastern Guatemala, southern Honduras, and parts of Nicaragua (OCHA, 2020[23]). In 2022, the Southern Cone, traditionally a global pantry for both grains and meat, continues to be hit by severe levels of drought. This has led to a decrease in agricultural productivity, as well as widespread food security concerns (Amaya, 2022[24]). In turn, this has negative effects on GDP of most countries in the region (Banerjee et al., 2021[25]), on their fiscal accounts, and on the most vulnerable (Chapter 2) (Bárcena et al., 2020[26]).

The economic cost of the impact of each natural disaster depends on the level of development of the country, which is also related to its level of preparedness and capacity to respond to natural disasters. On average, a natural disaster results in an increase in the fiscal deficit of 0.3% of GDP for upper-middle-income countries, 0.8% for lower-middle-income countries and 0.9% for low-income countries. The main negative impact is concentrated in a drop in fiscal revenues as a result of the fall in GDP. For lower-middle-income and low-income countries, this reduction in public revenues is equivalent to 0.8% and 1.1% of GDP, respectively (Alejos, 2021[27]). The size of the government’s reaction in the event of a disaster depends not only on the severity of the disaster but also on the government’s rate of compliance in meeting its liabilities – that is, its ability and willingness to meet or exceed its ex-ante commitments to shoulder specific disaster-related costs (OECD/The World Bank, 2019[28]).

The effects of fiscal deficits can be specifically harmful to economies with tight fiscal space and can leave long-term scars on fiscal accounts. Natural disasters can lead to dramatic increases in public debt, the abandonment or postponement of new investment projects, and the procyclicality of fiscal policy, especially for countries that do not have adequate insurance mechanisms for natural disaster risks (such as catastrophe bonds or disaster insurance) (Chapter 4) (IDB, 2021[29]). It is also important to consider that similar negative fiscal effects can be caused by the concentration of multiple non-extreme events in a short period, especially when there are conditions of high exposure and vulnerability in the country.

Some Caribbean economies present the highest levels of indebtedness: in 2020, nearly three-quarters of small states with unsustainable debt levels were in the Caribbean. Natural disasters, alongside poor economic performance, insufficient fiscal restraint and high financing costs in capital markets, are the main reasons for these high debt levels. The cost of debt service for these economies greatly reduces their fiscal space and undermines their ability to react to further shocks and to fund the necessary public services and public investment to drive their development process (OECD et al., 2021[10]).

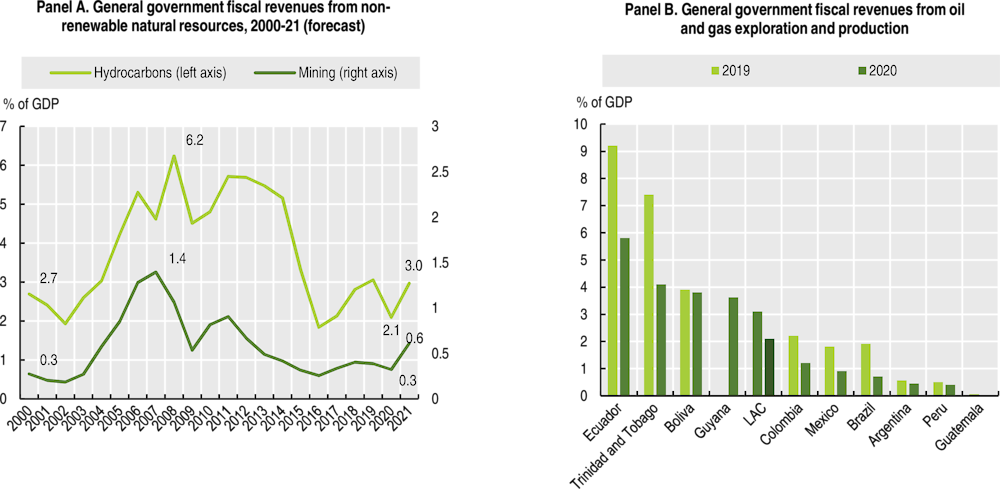

LAC will need to diversify its tax revenue to compensate for the coming fall in public revenues from hydrocarbons in main producing economies

As the world transitions to clean energy sources, demand for non-renewable resources will decline, entailing a drop in public revenues in a group of LAC countries that export hydrocarbons. As alternative technologies become cheaper, and measures to address climate change and implement the Paris Agreement are put in place, demand for oil is expected to fall (IDB, 2021[29]). Before Russia’s war against Ukraine, it was estimated that, in scenarios that meet the Paris Agreement targets, oil production in LAC needed to fall by 60% by 2035, which would entail losing about USD 3 trillion in tax revenue (Solano-Rodríguez et al., 2019[30]; Vogt-Schilb, Reyes-Tagle and Edwards, 2021[31]). Similarly, the role that natural gas plays in the region’s economy will be progressively reduced, leaving half the reserves untapped and reducing associated tax revenues by up to 80% (Welsby et al., 2021[32]).

This phasing out among major hydrocarbon producers will have significant negative effects on fiscal revenues and on foreign exchange. Hydrocarbons are a major generator of foreign exchange, with its exports accounting for one-third or more of total exports in several countries. Concerning fiscal revenues, the exploration and production of oil and gas account, on average, for around 3% of GDP (Figure 1.8, Panel A). This can reach above 15% of total revenues in Bolivia, Mexico, and Trinidad and Tobago and 24.2% in Ecuador (Titelman et al., 2022[33]). These revenues can excede, on average, 3% of GDP and in some cases more than 7%, as in Ecuador and Trinidad and Tobago (Figure 1.8, Panel B) (OECD et al., 2022[17]). If the decline in hydrocarbon revenues is not offset by an increase of those from other sources or economic diversification, these countries will experience large fiscal deficits (Titelman et al., 2022[33]).

Figure 1.8. General government fiscal revenues from non-renewable natural resources in selected LAC economies

Note: For Panel A the series refers to the average of the countries presented in Panel B.

Source: (OECD et al., 2022[17]).

Stranded assets can be an additional cost of inaction against climate change

As climate policies progress in the region and the phasing out of fossil fuels makes headway, hydrocarbon reserves and infrastructure are at risk of becoming stranded assets, resulting in financial losses for LAC economies.

Many economies in the region continue to develop new oil and gas projects that risk ending up as stranded assets. For instance, Argentina, Brazil and Mexico have ambitious plans to increase hydrocarbon production; others, such as Guyana, have plans to start exploiting it on a scale transformative for their economies (IEA, 2017[34]). If all planned fossil fuel power plants were built, there would be a 150% increase in the region’s “committed emissions” (IDB, 2021[29]). In addition, ten coal-based power plants were inaugurated in the last decade, illustrating how, between 2009 and 2016, countries were still choosing coal-based thermal power over other cleaner options, such as solar, wind or hydro (Bermúdez, 2020[35]).

Some types of stranded assets will represent higher costs. For instance, coal technologies are expected to make up a small percentage of the total capacity stranded in the LAC region. Still, the cost associated with the stranding of these assets is the highest. This is because they are more capital-intensive than gas and oil plants and are assumed to have longer lifetimes (60 vs. 45 years) and thus a lower depreciation rate (Binsted et al., 2020[36]).

Economies in the region that are more advanced in their transition to low-carbon energy production are already closing coal-based plants. For instance, in Chile, since the Decarbonisation Plan was announced in 2019, 6 coal-based thermoelectric plants have closed. Another 5 will close by the end of 2024, and the remaining 17 will close before 2040 (Parra, 2021[37]).

Spending decisions should consider the effects of climate change and the green transition

LAC must close its investment gap by allocating more resources in infrastructure to increase resilience and achieve its decarbonisation goals. The region already falls behind in terms of investment. In 2021, it invested around 19.5% of GDP, below the 22% invested in advanced economies and the 39% invested in Emerging and Developing Asia (IMF, 2022[5]). To achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (including resilience and decarbonisation goals), the region will need to increase its investment in infrastructure by about 5% of GDP (Galindo, Hoffman and Vogt-Schilb, 2022[38]). Despite the need for high investment, the region must continue to balance between capital and current spending, using the momentum to finance the green transition.

LAC must invest more to become more resilient against the negative effects of climate change. Climate change increases the frequency of natural disasters and causes changes in precipitation and temperature, along with coastal flooding. The current infrastructure of the region can be vulnerable to these events. New energy, transport, water or telecommunications projects must envisage the risk that these events pose. Moreover, existing infrastructure must be made resilient to these events, while new infrastructure must be created to reduce their effects (e.g. flood control dams, floodwalls or water dams to preserve and redistribute water to zones experiencing droughts). It is estimated that, for every USD 1 invested in making infrastructure and economies more resilient, USD 4 is avoided in impact costs (Galindo, Hoffman and Vogt-Schilb, 2022[38]). Similarly, the region could explore the role of nature-based solutions (NbS) in limiting and managing the current and future impacts of climate change. NbS are measures that protect, sustainably manage or restore nature, with the goal of maintaining or enhancing ecosystem services to address a variety of social, environmental and economic challenges (OECD, 2020[39]).

Although the investment required to achieve resilience is high, spending reallocation and early planning can help reduce costs. Climate strategies are important for anticipating long-term objectives in government planning, managing risks appropriately and greening public spending. To achieve carbon neutrality and climate resilience in 2050 a multi-sectoral climate strategy is needed, that aligns all sectoral strategies and incorporates decarbonisation and resilience criteria into public investment and budget systems (Galindo, Hoffman and Vogt-Schilb, 2022[38]).

Alongside the correct infrastructure, financial frameworks that manage climate-related risks and increase financial resilience are needed. LAC economies must develop frameworks that can manage national risks while promoting global climate financial resilience. As such, frameworks that identify risks and better understand them in terms of their components (hazards, exposure and vulnerability) and sources can play a key role, mitigating financial losses through risk reduction.

Despite best efforts, risk will always remain. Thus, coherent and integrated multipronged government financial strategies must be put in place (OECD, forthcoming[40]). Examples to minimise risk include improved building codes, better territorial and watershed planning, analysis of the budgetary impact of risk, and financial preparedness, including the use of insurance and reinsurance financial instruments (Galindo, Hoffman and Vogt-Schilb, 2022[38]). It is also necessary to scale up investment towards financial instruments such as green, social, sustainable and sustainability-linked bonds (GSSS Bonds) within internationally aligned frameworks that include green standards and sustainable taxonomies (Chapter 4). These will allow for increased and more effective redirection of spending towards sustainable projects that contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation. Additionally, as some adaptation measures are costly, governments must carefully evaluate the ex-post impacts and the probability of disasters occurring. Post-disaster loss assessment can provide qualitative and quantitative information to help identify the strengths and weaknesses of risk assessment.

If fiscal policy is to be effective, it must be through co-ordinated efforts

For any fiscal policy or reform to be effective, it must co-ordinate tax, spending and debt policies, considering the socio-economic and political context through well-defined sequencing of actions. It also needs to be backed by a broad consensus, built through national dialogue and clear communication (Chapter 5). The political economy of fiscal policy is more important than ever (Nieto-Parra, Orozco and Mora, 2021[41]).

Moreover, a fiscal sustainability framework focused on strengthening public revenues will be required to ensure the viability of a growing green expenditure trajectory. In the short term, the region will have to focus on reducing tax evasion (6.1% of GDP in 2018) and on reviewing tax expenditures (ECLAC, 2021[42]). It will also be key for countries to align their tax codes with new international best practices and to strengthen tax frameworks applied to the extractive sector (Titelman, 2022[43]). In the medium term, the region will have to focus on generating more progressive and greener fiscal pacts, with the aim of increasing tax collection and strengthening direct income and property revenues. It will also need a fully-fledged redesign of hydrocarbon taxation and subsidy policies (Chapter 4) (Titelman et al., 2022[33]). Additionally, to guarantee a just transition it will require public investments that attract green private investment (crowding-in); generate direct tax incentives towards renewable energies and decarbonisation, digital inclusion, and research and development; and lay the foundations for universal social protection systems (Chapter 4) (Titelman, 2022[43]). In terms of green tax incentives, special attention must be given to their design in relation to policy objectives. If misused, they can reduce revenue-raising capacity; create economic distortions; erode the principle of equity; increase administrative and compliance costs; and potentially trigger harmful tax competition and windfall gains to investors for projects that would have taken place in the absence of the incentive (Celani, Dressler and Wermelinger, 2022[44]).

Social conditions remain worse than before COVID-19

Poverty and extreme poverty in LAC remain above pre-pandemic levels. By 2022, ECLAC estimated that 33% of the population would be in poverty, and 14.5% would live in extreme poverty as a consequence of limited economic performance and increasing inflation (ECLAC, 2022[1]). Poverty rates in 2022 are the highest since 2008, before the global financial crisis. After the strong increase in 2020 due to the COVID-19 crisis, poverty slightly receded in 2021 due to the strong rebound (Figure 1.9). However, low economic growth and rising inflation in 2022 reversed these small gains. Extreme poverty has steadily increased every year since 2014 – even in 2021, despite the strong rebound (ECLAC, 2021[45]; ECLAC, 2022[1]). The rise of poverty and extreme poverty is a result of massive losses of jobs and livelihoods, low potential growth, high inflation rates, lack of sufficiently strong social protection systems and, in some countries, reduction in emergency income transfers that was not offset by the expected increase in employment income (ECLAC, 2021[45]; OECD et al., 2021[10]; OECD, 2022[12]).

Since the pandemic, there has also been a generalised impoverishment of much of the population in Latin America, which has translated into downward mobility. This means that, since 2020, the low and lower middle-income strata’s share of the population has increased, to the detriment of that of the upper middle- and high-income strata. With the recovery measures and economic upturn in 2021, there was a clear improvement in the middle classes, which regained some of their income. Still, the situation for low-income and low-middle-income classes worsened, and extreme poverty increased (ECLAC, 2022[2]).

Figure 1.9. Poverty and extreme poverty rate evolution

Emergency cash transfers are key to offsetting the negative effects of the pandemic and external shocks on employment income and, therefore, to addressing poverty. However, in most countries, these are not enough to curb the increase in poverty. For instance, compared to the previous years in most countries in the region, the increase in the total income of households that received transfers in 2020 was smaller than the fall in their labour income. The notable exception was Brazil, where the fall in labour income represented a loss in the total income of about 4%, while transfers were equivalent to an increase in the total income of 7% (ECLAC, 2022[2]).

Poverty is heterogeneous not only among countries in the region but also among population groups. Across all countries, the trend shows that women aged 25 to 39 have higher poverty rates than men of the same age. Likewise, poverty rates can be 1.3 to 1.8 times higher for people under age 15 than for the next age group (ages 15 to 39). Additionally, the largest gaps are found in countries with low poverty rates, such as Brazil, Chile, the Dominican Republic and Uruguay. In countries where the incidence of poverty is higher, the gap between age groups tends to narrow (ECLAC, 2022[2]).

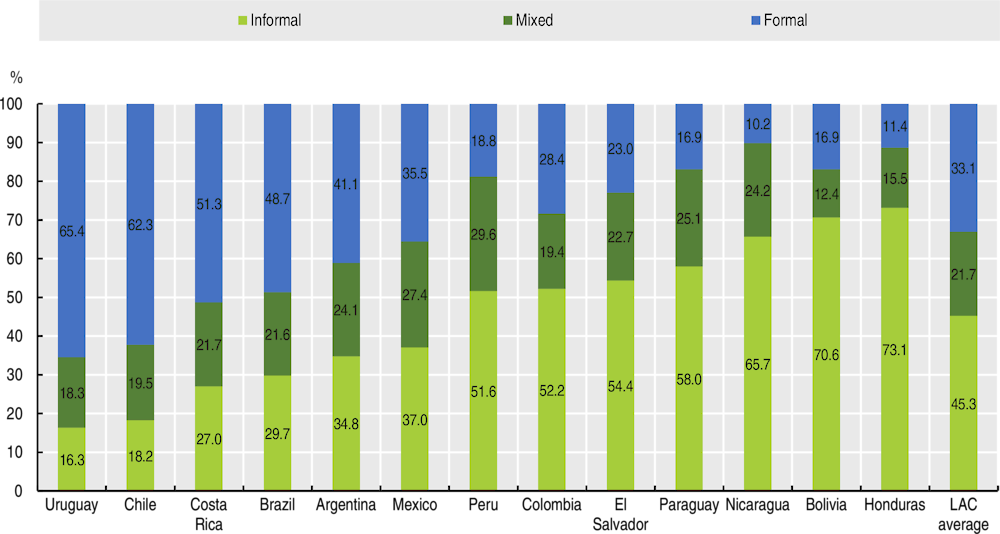

Informality remains a key challenge to tackling poverty and extreme poverty. In LAC, both informal and mixed households account for two-thirds of the total population. On average, almost half (45.3%) of people in LAC countries live in a household that depends solely on informal employment, 21.7% live in households with formal and informal workers (mixed households), and the remaining 33.1% live in completely formal households. In Bolivia, Honduras and Nicaragua, more than 60% of households rely entirely on informal employment, making them especially vulnerable to shocks such as the COVID-19 crisis (Figure 1.10) (OECD, forthcoming[46]).

Figure 1.10. Distribution of overall population, by degree of informality of households, 2019 or latest

Having a perspective on household informality is key to bringing about new policy insights, as the informality status of working members within a household has implications for its dependent members, and indicates the various vulnerabilities to which they are exposed. Such insight is also key to analysing the opportunities that the green agenda will bring to create new high-quality formal jobs in LAC (Chapter 3) (OECD et al., 2021[10]; OECD, forthcoming[46]). This is also the case for analysis that links informality with the structural axes of the social inequality matrix in the region, including a territorial perspective of informality, as this is not a phenomenon evenly distributed within countries (Abramo, 2022[47]; Espejo, 2022[48]). It is crucial that strategies to reduce informality, including those connected to a green transition, take its diverse expressions into account.

Although the slow trend of inequality reduction was reversed in 2020, cash transfers prevented a larger increase than occurred

Inequality in income distribution has also increased in most countries in the LAC region. In 2020, the deterioration in distribution affected the poorest sectors the most, halting the trend of falling inequality that had been slowing down since 2002 and had lost pace since 2010. The Gini coefficient for the Latin American average went from 0.54 in 2002 to 0.46 in 2020, with very slight reductions from 2010 onwards. Countries demonstrating among the highest inequality coefficients in 2020 included Brazil, Colombia and Panama, with averages above 0.50. The lowest coefficients occurred in countries including Argentina, the Dominican Republic and Uruguay, with an index of 0.40. A comparison of the situation in 2017 with that prevailing in 2019 and 2020 shows that inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, increased in nine countries and decreased in six (ECLAC, 2022[2]). The distributional deterioration affected the poorest segments of the population the most (ECLAC, 2022[2]).

To better explain the evolution of changes in inequality among countries, it is necessary to refer to the evolution of average household income. Although there was a decrease in total average, the determining differential factor is the way in which the losses were distributed. In countries where inequality increased, the better-off quintiles lost less than the poorest. In this sense, the fall in income for the poorest quintile was on average 3.2 times the reduction in total income for the richest quintile. Thus, the wage income of the poorest quintile collapsed on average by 39.4%, which represents 5.1 times the decline in wage income experienced by the richest quintile (-7.8%). In contrast, in countries where inequality decreased, the richest quintile contracted the most. (ECLAC, 2022[2]). Emergency cash transfers also contributed to the reduction of inequality. The transfers implemented by states specifically to respond to the drop in income caused by the COVID-19 pandemic were essential in preventing a further increase in inequality. The Gini coefficient would have increased on average by 4% without them, compared to the actual increase of 1% in Bolivia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru and the Dominican Republic. Similarly, in these countries the Atkinson index would have increased to 13.8% without them, compared to its actual growth of 5.1%. (ECLAC, 2022[2]). In other economies, such as Chile, inequality actually dropped from 0.45 in 2020 to 0.39 in 2021 thanks to the import support policies (OECD, 2022[12]).

Strengthening social protection systems will be key to protecting the population

The implementation of social protection measures in response to the pandemic have been central to the welfare of the population but has also highlighted areas for improvement. During the last 15 years, countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have expanded the coverage of both contributory (financed by wages) and non-contributory (financed by taxes) social protection schemes (OECD et al., 2021[10]; ECLAC, 2022[2]). While significant progress has been made in building social protection systems, many informal workers remain often excluded from it (OECD et al., 2021[10]; OECD/ILO, 2019[49]; ECLAC, 2022[2]). More than half of the workers in the region do not participate in any contributory social security system against risks related to illness, unemployment, and old age (ILO, 2018[50]). On average, in the LAC region, more than 60% of economically vulnerable and informal workers do not benefit from labour-based social protection or a social assistance programme (OECD et al., 2021[10]). Despite their lower incomes and greater need for protection, informal workers often fall through the cracks of social protection systems, making many incomes insecure or vulnerable to income poverty affecting their families. Thus, it is fundamental that countries advance towards universal, comprehensive, sustainable and resilient social protection systems (ECLAC, 2022[2]).

Individuals and households in LAC, have a long tradition of informal networks of mutual support to cope with risks and uncertainty, especially in contexts where public options are absent or limited like in rural areas. Informal support is often organised around lifecycle or livelihood risk and vulnerability. Private transfers received from friends, relatives and other households are another element of this form of inter-household informal protection. Around the mid-2010s the share of private transfers in household income varies from 4% in Bolivia and Honduras to around 15% in Costa Rica (OECD/ILO, 2019[49]). However, relying on informal ties or mechanism for protection has several limitations and strong, public social protection systems are essential as part of a social contract to advance towards the exercise of economic and social rights. In the absence of universal access to social protection and social security policies, studies suggest that informal risk-sharing mechanisms are close to efficiency when it protects from idiosyncratic shocks linked to individuals, households, or lifecycle events, such as illness or death. They may fall short when it comes to broader shocks that affect a wider geographical area, such as a neighbourhood or community, which is likely the case for health environmental risks and the broad changes brought by green agendas. This can particularly hurt poorer households, which are already financially constrained (Watson, 2016[51]). It is therefore crucial to strengthen social protection systems that are universal, comprehensive, sustainable and resilient, and which can progressively expand coverage to informal workers, ensuring a green and just transition for all (OECD/The World Bank, 2020[52]; ITF, forthcoming[53]; OECD, 2021[54]; ECLAC, 2021[59]).

Regarding the contributory scheme, some Latin American countries have extended its coverage to informal economy workers. Reasons for success include several measures, such as combining the support for the formalisation of enterprises with access to social protection schemes; extending statutory coverage to previously uncovered workers; adapting benefits, contributions and administrative procedures to reflect the needs of informal workers; and subsidising contributions for those with very low incomes. In addition, several countries expanded the fiscal space needed to scale up social protection programmes financed through general government revenues. These efforts have significantly contributed to building social protection floors that guarantee universal health coverage and at least basic income security throughout the lifecycle, for instance through tax-financed pensions, disability benefits, child benefits, maternity benefits or employment guarantee schemes (OECD et al., 2021[10]) (Chapter 3).

Regarding the non-contributory scheme, according to official information, between 1 March 2020 and 31 October 2021, 33 countries in LAC adopted 468 non-contributory emergency measures and other support measures. These included three types: 1) monetary transfers; 2) in-kind transfers (including the provision of food, medical and education materials, as well as support for labour and productive inclusion); and 3) securing and facilitating access to basic services (water, energy, telephone and Internet) (ECLAC, 2022[2]). There were also measures aimed at containing and reducing household expenses, through tax relief, price setting and control for basic goods, and rents and payment facilities (Brooks, Jambeck and Mozo-Reyes, 2020[55]). While most of these measures were put in place in 2020, given the prolongation and depth of the economic and social consequences of the pandemic, it has been necessary to extend some measures or implement new ones (ECLAC, 2021[45]).

Going forward, it will be necessary to strengthen social protection systems (not only by increasing coverage but also by improving co-ordination and interoperability), make them more flexible against different types of shocks, ensure that they have positive long-term effects and improve their functioning while guaranteeing that they are properly funded.

Social protection schemes or cash transfers should have long-term development goals. Along with guaranteeing adequate levels of income, these goals could be promoting just, green education, labour or formalisation outcomes. For instance, there is evidence that targeted cash transfers, especially conditional, can spur investment in child schooling (OECD et al., 2021[10]; OECD, 2019[56]). Similarly, payments for environmental services can encourage a long-term change in behaviour to prevent future ecosystem degradation (Porras and Asquith, 2018[57]). A good example is Peru. Between 2014 and 2018, the Ministry of Environment and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) developed conditional cash transfers to stimulate community protection of tropical forests in the Amazon region. To date, 188 indigenous communities have been covered, and over 1 800 000 hectares (ha) of tropical forest have been placed under protection. The conditional cash transfers are benefiting indigenous families, which have been able to improve their income levels and livelihoods without endangering their forests. Sustainable development skills are also being developed, as beneficiaries are advised on how to use the conditional cash transfer to initiate and manage projects and to monitor forest conversion (deforestation) (GIZ, 2014[58]).

Governments must also improve the flexibility of non-contributory programmes with strategies that provide protection against different types of shocks, for example natural disasters in some cases exacerbated by climate change. Such programmes should complement existing strategies and programmes that focus on structural poverty with others that ensure income support in the face of systemic (or idiosyncratic) shocks. Social protection must therefore articulate and co-ordinate with disaster management, with a view to increasing social and institutional resilience in order to cope with the impacts of increasing disasters and allow for a transformative recovery that is equitable (ECLAC, 2021[59]). Hence, responsive social assistance programmes should be promoted so that countries can adapt quickly to contingencies and find flexible ways to respond to the needs of individuals and households affected by shocks. These are also key in preventing shocks from systematically translating into persistently higher levels of poverty and inequality (Stampini et al., 2021[60]).

Countries must address the most pressing challenges affecting the functioning of their social protection systems. Efforts include, among others: enhancing information systems and digital platforms to better identify potential recipients and participants; increasing levels of coverage and updated information; improving the institutional framework, considering the various territorial levels working towards a unified social registry, and improving the level of interoperability; improving electronic payment systems; and making income support programmes more sustainable (Stampini et al., 2021[60]; Berner and Van Hemelryck, 2021[61]; Alvarez et al., 2021[62]). Additionally, the COVID-19 crisis highlighted the need to improve co-ordination and interoperability among the labour, health and education systems to enhance countries’ overall social protection systems (Cabutto, Nieto-Parra and Vázquez-Zamora, 2021[63]; IPCC, 2022[64]). It is important to build on the advances in sectoral co-ordination that were consolidated during the pandemic, since they positively influenced the unequal distribution of the social determinants of health, such as poverty and unemployment (IPCC, 2022[64]).

In addition, it is important to take into account a comprehensive view of households when designing social protection systems. For instance, households with only informal workers face different vulnerabilities or in a different magnitude than mixed households, or those with household members working in the formal economy. These differences present an opportunity to design differentiated public policies that address specific needs to effectively mitigate the vulnerabilities and negative consequences of informality on individuals’ and households’ well-being.

Finally, it is essential that social protection systems have funding sources that will ensure their financial sustainability. This can be achieved, in part, by increasing tax revenues through the reduction of generalised subsidies and tax exemptions. For example, energy subsidies have negative externalities (Chapter 4). Among other measures to ensure their financial sustainability are: reducing tax evasion (ECLAC, 2017[65]); creating reserve funds, insurance and catastrophe bonds (Chapter 4); and developing regional risk-sharing mechanisms. The social protection system becomes more resilient and responsive, contributing to the fight against climate change and supporting a just transition to net zero emissions societies (Stampini et al., 2021[60]). This highlights the importance of comprehensive social protection policies that stimulate return on investment, a lever of structural change. It must be channelled in the right direction through public policy instruments – including taxation, financial policy, technology policy and regulatory policy – to increase relative returns for the benefit of the sectors that drive recovery (ECLAC, 2022[66]). However, a fiscal compact for equality and sustainability first requires a social compact to make this possible. The new social contract needs far-reaching political agreement and consensus and a different balance among the state, the market, society and the environment (OECD et al., 2021[10]; ECLAC, 2022[67]).

Innovative tax mechanisms could help increase revenues, promote formalisation and reduce inequalities

Innovative income support policies could be worth exploring to increase progressivity and formalisation in tax systems, although further research is needed and so far it has only been used in advanced economies. In addition to promoting further progressivity in personal income taxes, possible useful policies in LAC include negative income tax (NIT), earned income tax credit (EITC) or personalised value-added tax (P VAT). NIT or EITC programmes generate fewer distortions or disincentives to formalisation of employment than traditional non-contributory welfare programmes (Pessino et al., 2021[68]). They also avoid generating more fiscal pressure while addressing the equity impact of indirect taxes and reducing poverty, in much the same way as cash transfer programmes. NIT guarantees the revenue of a traditional cash transfer – independent of whether a person is unemployed, employed in informality or employed in the formal sector. As such, when a person secures a formal job, income tax benefits are not eliminated (as in traditional welfare programmes); rather, the worker’s net income increases and, as they earn a higher wage, the refundable tax credit gradually reduces to the point they start paying. That the person continues to receive government aid along with a formal salary ensures that formal job wages are higher, more attractive and more affordable. It should be noted that NIT is targeted to a specific population, not all individuals (Pessino et al., 2021[68]).There is evidence that EITC programmes have many positive effects, including increased labour force participation and poverty reduction, as they reward employment. The difference between EITC and NIT is that, for low-income wages, transfers increase proportionately to salary; once the salary is high enough, they gradually reduce to zero. Evidence has also shown that EITC helped to reduce informality in the United States, as it can be complemented by other measures, such as refundable tax credits (as long as a person is formally employed) or demand-side subsidies to firms to incentivise formal employment demand (Pessino et al., 2021[68]). In general, the proposed initiatives have so far been developed and evaluated only in developed countries. Before moving forward with such measures, further research and policies that establish the building blocks are needed, for instance the improvement of the registration/identification of informal workers.

P VAT might be an option to explore to increase fiscal resources while addressing the equity impact of indirect taxes and informality. This strategy consists in applying the VAT to all products and services at a standardised rate and implementing a tax refund based on the incidence of VAT on consumption among the poorest deciles. Using these targeted instruments also addresses the high degree of informality, a feature of most developing countries. As informality makes individuals in the lower deciles invisible, this population rarely benefits from the provision of transfers and public social services. The P VAT is useful in overcoming this situation by including individuals in the informal sector (Barreix et al., 2022[69]).

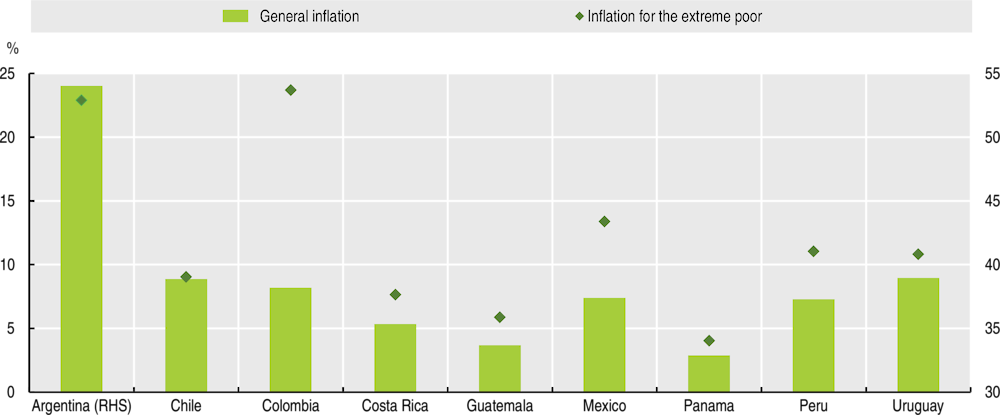

Higher inflation rates hit low-income households the hardest

One of the most concerning effects of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on LAC economies is the rise in global commodity prices. Inflation rates are putting pressure on households’ real incomes and savings, and middle- and low-income households are the most vulnerable (Gill and Nagle, 2022[70]). It is estimated that a 1% rise in inflation increases the share of low-income households by around 7%, while it reduces the share of high-income households by only 1% (Nuguer and Powell, 2020[71]). Consequently, inflation could also exacerbate inequality, aggravating existing social tensions in one of the most unequal regions in the world (Jaramillo and O’Brien, 2022[72]).

There are three main channels through which inflation affects the poorest particularly hard. The first channel is the unprotected nature of their assets, which undermines their purchasing power during shocks. This results from poor access to financial products and financial assets other than cash, such as interest-bearing accounts, that could protect their assets against inflation. The second channel is their income composition. In the formal sector, it depends on wages, pensions and social benefits, which are mostly rigid in the short term and respond more slowly to price volatility than the non-wage income of richer households (Ha, Kose and Ohnsorge, 2019[73]). As 45.3% of the LAC population lives in a household that relies exclusively on informal employment, their incomes are often not indexed and are not protected by social protection systems (Nuguer and Powell, 2020[71]). The third channel is the composition of each household’s consumption basket relative to patterns of price spikes. In emerging economies, 50% of lower-income people’s spending is on food vs. 20% for the rich (Gill and Nagle, 2022[70]). These channels explain why the most vulnerable are suffering the most from current food prices, which are at historic highs, as is the FAO’s Food Price Index. The situation in the agricultural sector is pushing up prices further, as agricultural production is exposed to rising input costs, particularly from fertilisers and fuels (FAO, 2022[74]).

Recognising the heterogeneity in LAC, it is noteworthy that about one-fifth of poor households in developing countries are net food producers; thus, this segment might be positively affected by higher food prices (Gill and Nagle, 2022[70]). However, the recent increase in fertiliser prices has been so steep that it has outpaced the gains from higher food prices, even for net food-producing households (FAO, 2022[75]).

Inflation is affecting the extreme poor on a larger scale than for the national representative household in LAC countries and is pushing millions back into these conditions. There is evidence that the extreme poor face an average price increase 3.55 percentage points higher than the total households in selected LAC countries (Figure 1.11). In Argentina, although year-on-year Consumer Price Index (CPI) growth was higher for the general population in the first four months of 2022, in April, year-on-year inflation was 1.41 percentage points higher for the extreme poor. Prices are driving more people below the poverty line, pushing millions into food and energy insecurity. It is estimated that in LAC, if prices rise by 2 percentage points above a baseline scenario, extreme poverty would increase by 1.1 percentage points compared to 2021 levels, which translates into 7.8 million people joining the 86.4 million who are food insecure. This adds to the reversed trend of poverty reduction that started in 2020 compared to 2019, with poverty and extreme poverty increasing by 2.5 and 1.7 percentage points, respectively (ECLAC, 2022[1]).

Figure 1.11. Year-on-year inflation for the representative consumption basket vs. inflation for the extreme poverty basket, year-to-date average 2022, selected LAC countries

Notes: Year-to-date average of year-over-year growth of national CPIs vs. growth of extreme poverty lines 2022. Extreme poverty lines are based on the cost of a basic food basket that covers basic food needs and provides the minimum caloric requirement of the members of a reference household. The Chilean extreme poverty line also includes a share of non-food basic goods and services. For Colombia and Peru, the food and non-alcoholic beverages division of their CPI was used. For Panama, the data covers the districts of Panama and San Miguelito. Argentina is plotted on the right hand side (RHS) axis.

Source: Local sources, OECD construction based on data from national statistic offices on CPIs and poverty lines.

Policy action is needed to reduce the negative effects of inflation rates on the most vulnerable. In the short run, non-contributory social protection policies, such as cash transfers, school feeding programmes, and food and in-kind transfers, could mitigate negative impacts on poor households, as they did for millions of Latin Americans during the pandemic (Jaramillo and O’Brien, 2022[72]). In the long term, governments should put in place reforms to tackle the structural channels through which poor households’ assets are more vulnerable to inflation. Promoting access to financial products and increasing labour formalisation would protect the value of poor households’ assets and shield them through social protection systems (Ha, Kose and Ohnsorge, 2019[73]). In addition, a more granular measurement of the asymmetric impacts of inflation on various income groups would better guide the design of social protection policies (Gill and Nagle, 2022[70]).

Food, energy and fertiliser security must be addressed. In the short term, governments should keep markets open, avoid trade restrictions and use instruments such reducing value-added taxes on basic consumption baskets. In the long term, greater regional trade integration could generate positive effects on food security, and regional co-ordination in fertiliser production could help achieve a long-term goal of reducing dependence on fossil or mineral fertilisers (ECLAC, 2022[1]). Renewable energy mandates have already generated long-term benefits and have the potential to mitigate the regressive effects of fossil energy price peaks (World Bank Group, 2022[76]). Building a favourable regional ecosystem for green transformation could enable countries to develop more inclusive green energy matrices (ECLAC, 2022[1]).

Key policy messages

Overall, the LAC region is expected to undergo a strong economic slowdown in 2022 due to remaining structural challenges, such as low potential growth and a complicated international context. At the international level, Russia’s war against Ukraine and China’s economic slowdown are making the already challenging scenario of low potential growth and high social vulnerabilities in the LAC region even more challenging. In particular, main indirect channels of Russia’s war against Ukraine relate to lower global GDP growth, disruptions in trade, and higher volatility in both commodity prices and capital markets.

The spike in commodity prices affects the region’s economies in different ways, with net exporters in South America benefiting while Central American and Caribbean countries experience the opposite.

Volatility in capital markets and the normalisation of monetary policies in advanced economies could affect LAC. So far, since March 2022, risk premia increased but remain below the levels seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, and currencies have depreciated in the majority of LAC economies, due to domestic and external factors.

Countries in the region face the challenge of achieving sustainable growth, and a green and just transition, while protecting the most vulnerable. However, this is increasingly difficult, as policy space – both monetary and fiscal – is becoming smaller. Growing inflationary pressures have pushed monetary authorities to control inflation rates and to anchor inflation expectations to promote macroeconomic stability and prevent the negative social effects. Regarding fiscal policy, greater spending requirements to support economic recovery face smaller fiscal capacity as a result of higher debt burdens after the COVID-19 pandemic and higher debt service costs. Going forward, climate change and the green transition can weigh heavily on fiscal accounts. Therefore, the region will need to mobilise resources to compensate shortfalls and invest more, better and greener to reduce the adverse effects of climate change and finance the green transition.

Although overall poverty levels declined in 2021 compared to 2020, the economic slowdown of 2022 and rising inflation have erased the gains. As inflation most affects the vulnerable, and there is a declining trend in the number and coverage of social protection programmes implemented to address the COVID-19 crises, it is critical that countries strengthen universal, comprehensive, sustainable and resilient social protection systems.

Box 1.2. Key policy messages

There is an intensification of inflationary pressures that does not appear to be temporary. Central banks across LAC have been increasing policy rates to anchor expectations. In some LAC countries, further increases in interest rates will be necessary to promote macroeconomic stability and limit the negative impact of price increases on the most vulnerable populations.

Unchecked inflation generates poverty traps and takes a particular toll on the most vulnerable, who see their purchasing power quickly erode. With macroeconomic policy space being reduced, most LAC countries will face the multi-dimensional challenge of balancing recovery stimulus, financing the green transition, and protecting the most vulnerable, particularly from the impact of inflationary pressures. The composition of the fiscal consolidation that some economies will undertake plays a key role in the strength and inclusiveness of the recovery.

Fiscal policy will continue to be at the core of the recovery. To be effective, it must take into account the current complex context through well-defined sequencing of actions and be backed by a broad consensus built through national dialogue and clear communication.

A set of tax policy options are available in LAC that could help increase revenues without compromising the recovery. These include measures to reduce tax evasion and avoidance, increase the progressivity of personal income taxes and policies to improve tax compliance, strengthen tax administration and eliminate inefficient tax expenditures.

A green and just transition will require mobilising further revenues to increase investment that aims to reduce climate-related risks (physical and transition risks), and helps to advance a more sustainable and inclusive model of production and consumption that creates new quality green jobs.

Social challenges from the COVID-19 pandemic remain. Households living in poverty and extreme poverty, but also non-poor, low-income and lower-middle-income households, face persisting high inequality and high levels of vulnerability. Inflation exacerbates this, as increases in food, energy and fertiliser prices affect the most vulnerable through various structural channels, such as the nature of their assets and the composition of their income and consumption basket.

To counteract the regressive effects of inflation in LAC, governments should complement monetary measures with fiscal policies, such as social protection policies. These could protect poor households, as they did for millions of Latin Americans during COVID-19. Longer-term policies to protect the value of poor households’ assets include promoting access to financial products and increasing labour formalisation, which would shield them through social protection systems.

Strengthening universal, comprehensive, resilient and sustainable social protection systems will be a key determinant in containing the social crisis.

In response to the episode of rising inflation and to ensure food and energy security, the region has the opportunity to strengthen domestic trade and to foster an integrated regional ecosystem to boost fertiliser security and inclusive energy matrices.

References

Abramo, L. (2022), Policies to address the challenges of existing and new forms of informality in Latin America, United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/47774/1/S2100648_en.pdf.