To finance a development model that is inclusive, sustainable and resilient the Dominican Republic needs to mobilise further public and private resources. On the public side, further tax revenues that reduce inequalities can be levied by rethinking the tax structure, rationalising tax exemptions, and fighting tax evasion. Similarly, there is space to improve the quality of public spending, to ensure its efficiency and increase its impact. Regarding the private sector, strengthening the role of the financial system is crucial to mobilise the necessary resources for development. Actions include further developing the banking system, strengthening the public debt market, and deepening the private debt market. The chapter first examines public finance, analysing revenue and expenditure and exploring potential areas for improvement. It then analyses the financial system and ways to improve private sector finance and further develop capital markets. Finally, the chapter presents the main conclusions and offers policy recommendations, arguing that advancing towards a more robust “financing for development” model will necessitate agreement on a comprehensive fiscal pact.

Multi-dimensional Review of the Dominican Republic

4. Financing for development in the Dominican Republic: Towards a more inclusive, resilient and sustainable model

Abstract

Introduction

The aftermath of the COVID‑19 crisis and the complicated external context have highlighted pre-pandemic structural challenges in the Dominican Republic such as low mobilisation of resources for development. The country needs to mobilise more resources in order to finance an inclusive, sustainable and resilient development model, Nevertheless, the country is currently in the difficult position of shouldering the costs of managing the crisis, external shocks and financing the recovery, and, more broadly, puts the “Financing for Development” model under stress.

In this context, this chapter seeks to explore where the Dominican Republic stands in its capacity to build a “Financing for Development” model that is inclusive, sustainable and resilient. The chapter aims to examine and address the per-pandemic structural challenges that the Dominican Republic faced to mobilise the necessary public and private resources. To this end, Chapter 4 is organised into three main sections. The first examines public finance, analysing revenue and expenditure and exploring potential areas for improvement that could increase the country’s fiscal capacity. The second section focuses on the financial system and on how to improve private sector finance, as well as on the potential for further developing capital markets. The final section of this chapter presents the main conclusions and offers a number of policy recommendations, arguing that advancing towards a more robust “financing for development” model will necessitate agreement on a new and comprehensive fiscal pact.

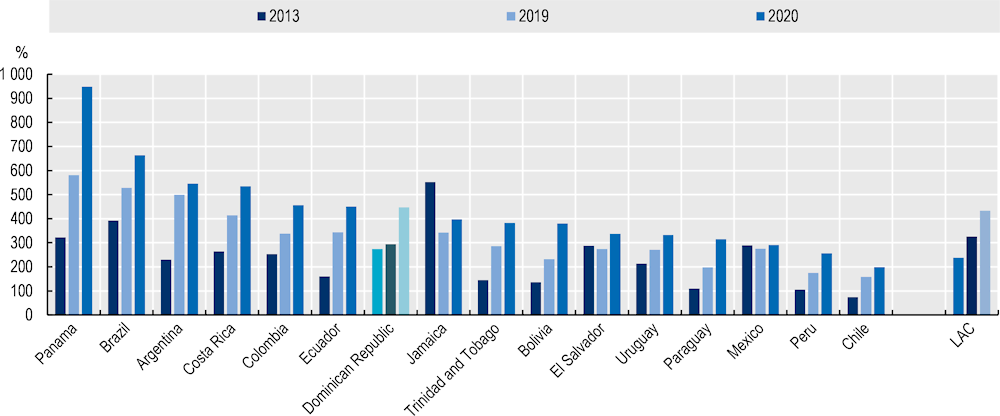

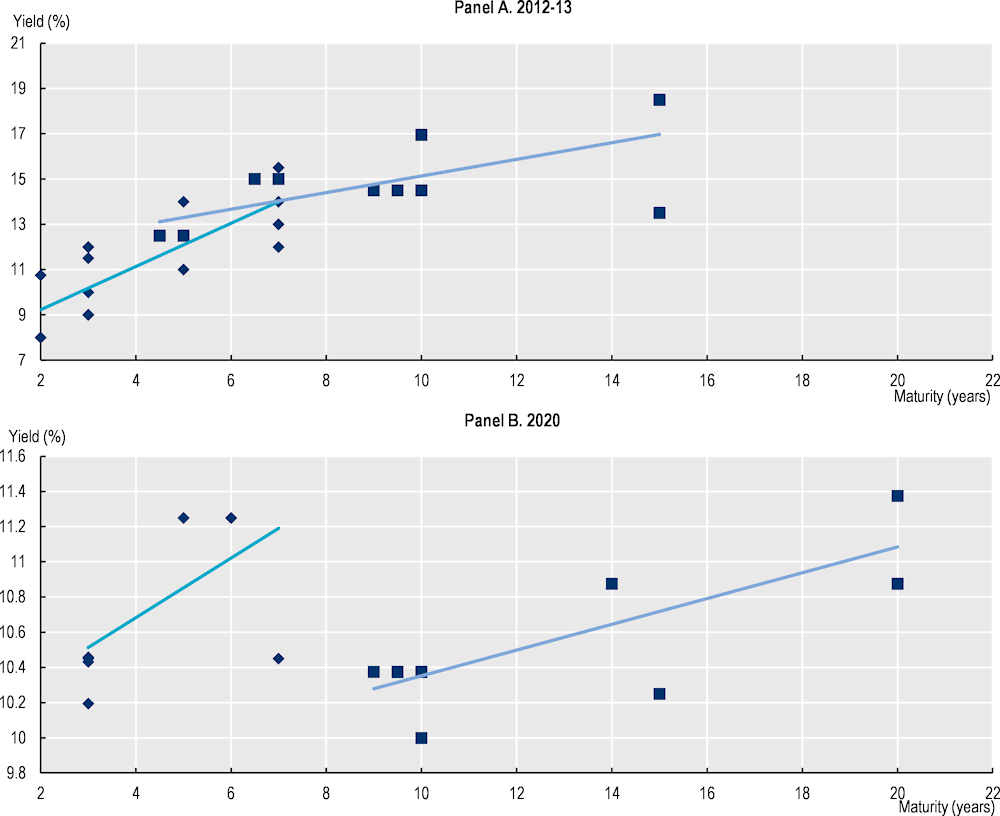

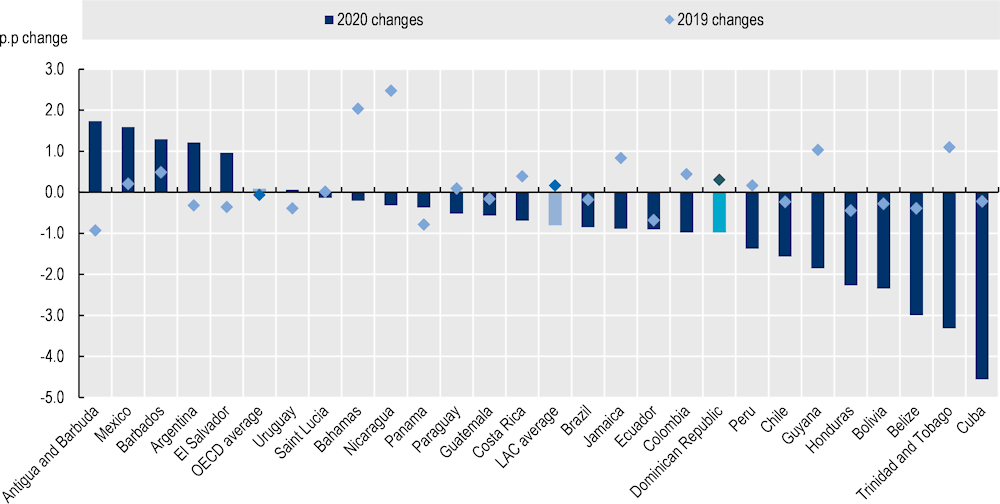

Public finance in the Dominican Republic

As in other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), the COVID‑19 pandemic pushed the Dominican Republic’s government to take urgent action in response to the crisis. Various emergency programmes were put in place to support households, businesses and workers, including the Employee Solidarity Assistance Fund (Fondo de Asistencia Solidaria al Empleado; FASE), which covered up to 70% of salaries for employees whose contracts had been suspended due to COVID‑19 pandemic lockdowns, and which also supported small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that continued to operate with the same staff. Other programmes targeted more vulnerable populations with specific cash transfers, such as the Programa de Asistencia al Trabajador Independiente (Pa’ Ti programme) for independent workers, or the Quédate en Casa (Stay at home) programme for households with at least one member who was particularly vulnerable to COVID‑19 (Cejudo, Michel and de los Cobos, 2020[1]). These actions involved a high fiscal cost, and social spending rose by 57.3% in 2020 compared with 2019 (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2022[2]). Between April and June 2020, the cost of these measures represented 1.1% of gross domestic product (GDP) (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2021[3]). As in the rest of the LAC region, tax reliefs were used in the Dominican Republic to mitigate the economic impacts of the crisis, mainly in the form of tax deferrals. These were applied to both direct (personal income tax) and indirect (goods and services) taxation and, in some cases, were applied to specific sectors, such as tourism (OECD et al., 2022[4]), where, for example, the deadline for filing and paying income tax (and the “simplified tax regime”) was extended and those who owed additional taxes had the option of paying in four interest-free instalments. Overall, tax measures coupled with the economic slowdown decreased tax revenues in the Dominican Republic by around 7% (or 1% of GDP) in 2020, while the average fall in tax revenue in LAC in 2020 was 4% (Figure 4.1) (OECD et al., 2022[4])

Figure 4.1. Evolution of tax receipts in LAC, year-on-year real variation in percentage, 2020

Note: The LAC average represents the unweighted average of 26 LAC countries included in this publication and excludes Venezuela due to data availability issues. The OECD average represents the unweighted average of the 38 OECD member countries. Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica and Mexico are also part of the OECD (38).

Source: (OECD et al., 2022[4]).

The COVID‑19 pandemic hit at a time when fiscal space in the Dominican Republic was traditionally tight, mainly due to particularly low levels of tax revenues and generally higher expenditures. In this context, the short-term requirements for responding to the crisis, combined with the lower levels of tax collection associated with reduced economic activities, pushed fiscal deficit of the central government to 6.6% of GDP in 2020, compared with the 0.7% average during the years following the 2008 financial crisis (ECLAC, 2021[5]; BCRD, 2022[6]). Similarly, the medium-term costs of the post-COVID‑19 recovery, and the reforms needed to overcome long-standing structural challenges, will demand stronger mobilisation of public finance.

Tax revenues can be strengthened through a combination of measures, including rethinking the tax structure, rationalising tax exemptions and fighting tax evasion

Increasing tax revenues is a key policy objective for the Dominican Republic, but achieving this goal presents numerous structural challenges and complex choices. A variety of policy options can lead to greater tax revenues; identifying these and finding the right balance of measures will be crucial for success and for maintaining the taxation system as a catalyst for equality and economic growth. This section analyses the structure of the taxation system in the Dominican Republic and identifies potential areas for policy action that should be at the centre of the debate for fiscal reform and a broader fiscal pact. In particular, it is argued that the main areas of action should revolve around the following: 1) rethinking the tax structure; 2) rationalising tax expenditures; and 3) fighting tax evasion and avoidance.

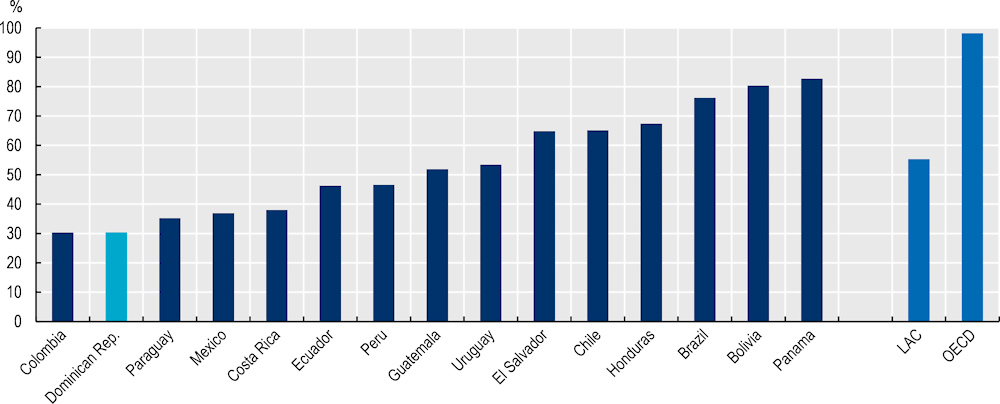

Tax revenues are low in the Dominican Republic compared with the LAC and OECD averages, and are insufficient to finance the post-COVID‑19 recovery

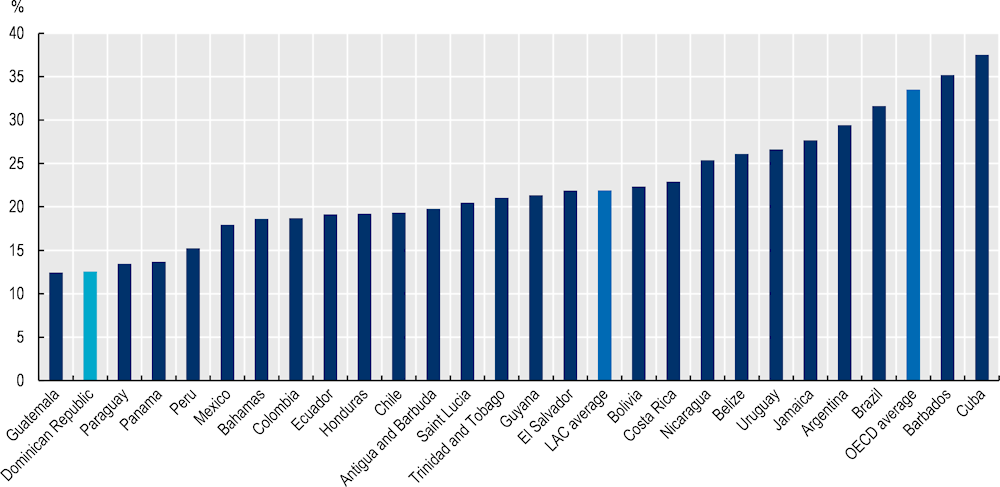

There is space for increasing tax revenues in the Dominican Republic, which represented 12.6% of GDP in 2020. This is the second-lowest tax-to-GDP ratio in the LAC, only just above that of Guatemala (12.4%) and just below those of Paraguay (13.4%) and Panama (13.7%) (OECD et al., 2022[4]). These figures are particularly low when compared with the tax-to-GDP ratios in countries such as Brazil (31.6%) and Uruguay (26.6%), and to some Central America and Caribbean countries such as Trinidad and Tobago (21.1%) and Costa Rica (22.9%). Tax revenues in the Dominican Republic are low in comparison with the LAC average of 21.9% and the OECD average of 33.6% (Figure 4.2). Furthermore, tax revenues in the Dominican Republic have remained relatively constant during the last decade: they had increased before the pandemic in 2019 by slightly more than one percentage point since 2010, when the tax-to-GDP ratio stood at 12.4% (OECD et al., 2022[4]). This is similar to the LAC tax-to-GDP ratio average over the same period. Moreover, in the Dominican Republic tax revenues as a percentage of GDP remain at a lower level than before the 2008 international financial crisis.

Figure 4.2. Tax revenues as a percentage of GDP in the Dominican Republic, LAC and OECD, 2020

The Dominican Republic’s tax structure shows some imbalances that suggest potential areas for readjustment in order to increase tax revenues, expand the tax base and build a more efficient and equitable tax system

Indirect taxes are the main source of tax revenues, although their efficiency could be improved in order to increase tax collection

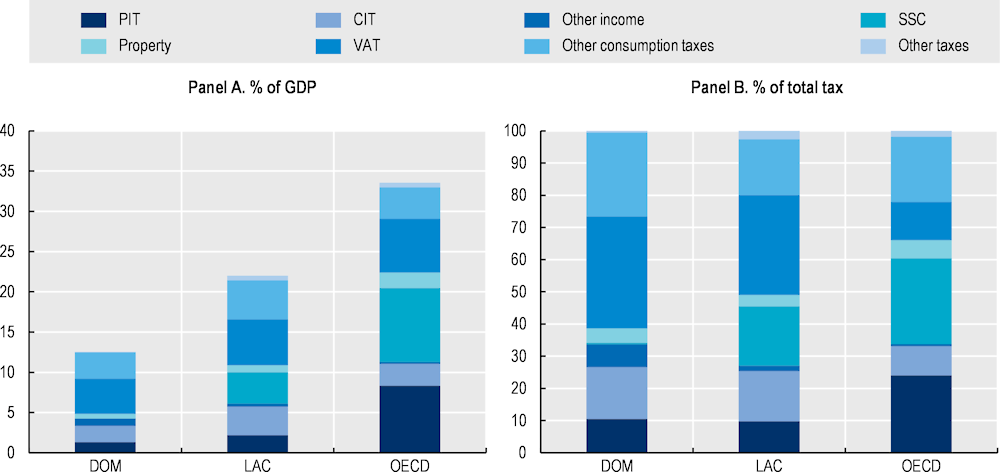

The tax structure in the Dominican Republic is particularly reliant on the indirect taxes that are levied on goods and services (Figure 4.3). They account for almost two-thirds (60.7%) of total tax revenues, representing 7.6% of GDP in 2020. This is well above the average share that indirect taxes contribute towards total tax revenues in LAC (48.4% of total tax revenues) and among OECD member countries (32.1% of total tax revenues), although revenues from indirect taxes account for a higher proportion of GDP both in LAC (10.5% of GDP) and in OECD member countries (10.6% of GDP) than they do in the Dominican Republic.

The main source of indirect taxes is value added tax (VAT), known in the Dominican Republic as the tax on the transfer of industrialised goods and services (Impuesto sobre Transferencia de Bienes Industrializados y Servicios; ITBIS), which accounts for more than one-half of total revenue from indirect taxes. The VAT rate in the Dominican Republic is set at 18%, the fifth-highest in the LAC region along with Peru (also 18%) and behind Argentina, Chile, Colombia and Uruguay. In the Dominican Republic VAT accounts for 34.7% of total tax revenues, above the LAC average of 31.0% (Figure 4.3, Panel A). However, tax revenues from VAT represent 4.4% of GDP in the Dominican Republic, below the LAC average of 5.7% (Figure 4.3, Panel B). The proportion of tax revenues collected from the ITBIS has increased steeply since the 1990s, when it represented 15.1% of total tax revenues, and from 2000, when it represented 20.5%. From 2010 onwards, this has remained stable at around 34% of total tax revenues (OECD et al., 2022[4]).

Figure 4.3. Tax structure in the Dominican Republic, LAC and OECD member countries, 2020

VAT is generally perceived as a tax with large collection potential; it can therefore be an important source of revenue to finance the COVID‑19 pandemic recovery as well as more general longer-term development (OECD, 2021[8]). Particularly in contexts of high informality, where the tax base is reduced, VAT could help increase revenues from the informal sector as it taxes some of the goods and services that informal businesses purchase. It can also act as an incentive for informal companies that do business with formal companies, and that wish to request VAT recovery, to formalise (OECD, 2017[9]).

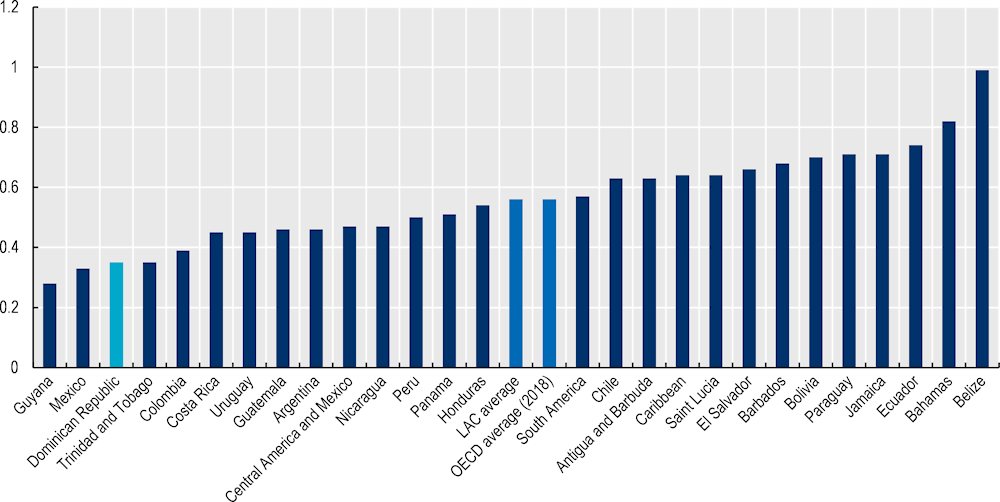

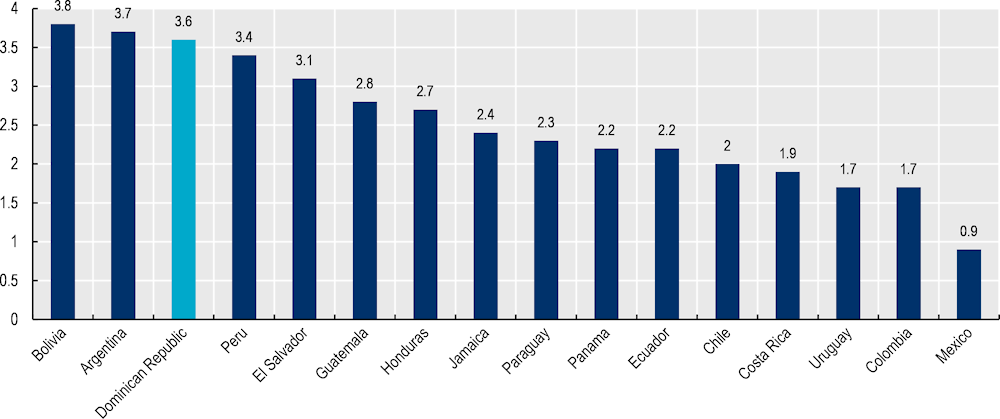

Significant scope exists to strengthen VAT functioning and design in order to improve its revenue-raising capacity in the Dominican Republic. In fact, despite the high share of total tax revenues collected through the ITBIS, there are a number of inefficiencies in the collection of this tax. In fact, the VAT Revenue Ratio (VRR) in the Dominican Republic is low relative to that in other LAC countries. The VRR measures the difference between the VAT revenue that has actually been collected and what theoretically could have been raised if the VAT were applied at the standard rate to the entire potential tax base, as in a “complete” VAT regime under full compliance. The VRR in the Dominican Republic is one of the lowest in LAC, at 0.35, well below the LAC and OECD averages of 0.56, and the average in the Caribbean sub-region of 0.71 (OECD et al., 2021[10]) (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4. VAT Revenue Ratio (VRR) in LAC countries and OECD

Low efficiency in VAT collection is caused by a variety of factors, including tax evasion, tax exemptions and weaknesses in tax administrations (Schlotterbeck, 2017[11]). VAT evasion is one critical factor that accounts for low VRR levels in the Dominican Republic, reaching a level of 43.8% in 2017 (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2018[12]). VAT evasion in the Dominican Republic is one of the highest in the LAC region, well above the LAC average of 30.1% (see the section on Fighting Tax Evasion). Similarly, ITBIS exemptions are used, with numerous specific goods and services being exempted from the ITBIS; this could partly explain the low VAT efficiency (see section on Rationalising Tax Expenditures). Exempted goods include educational materials, medicines, health services, financial services, utilities, non-conventional or renewable energy equipment, and the supply of inland transportation services of individuals and cargo. Exempted services include education, cultural services and electricity (KPMG, 2022[13]).

In order to improve ITBIS efficiency and increase tax revenues from this source, one option is to rethink existing exemptions and reduced rates. This option should be explored with caution, as many of those exemptions are intended to favour access to basic goods and services for the general population. However, these exemptions can be regressive in certain cases, as some of these goods and services are consumed in larger proportions by wealthier socio-economic groups. Similarly, in contexts of high informality, ITBIS exemptions may only have limited success in supporting low-income families, as these citizens buy some of their basic goods from the informal sector, and hence do not pay the ITBIS. This implies that keeping a uniform ITBIS rate for all formal consumption could actually be progressive, as it will mostly be paid by those who can afford it (Bachas, Gadenne and Jensen, 2020[14]). If a reduction of ITBIS exemptions is complemented by targeting social spending towards lower-income groups, it could result in higher ITBIS revenues (and overall fiscal revenues) without affecting people who are really in need.

Improving compliance is another relevant option for increasing ITBIS revenue, particularly through the use of digital tools. Two important areas of action will be expanding the use of electronic invoicing (e‑CF) (introduced in the Dominican Republic in early 2019) and advancing towards making it compulsory, and strengthening the implementation of the destination principle (O’Reilly, 2018[15]). One increasingly relevant challenge is linked to the growing importance of e‑commerce in the modern economy. This is particularly true in LAC, which is one of the fastest growing e‑commerce regions in the world, particularly as a result of the COVID‑19 pandemic. This expansion poses significant challenges to VAT collection, as the growth in online sales of services and digital products is not subject to effective provisions under traditional VAT rules. Similarly, there is an increased volume of imported low-value goods from online sales on which VAT is not collected effectively via traditional customs procedures (OECD/WBG/CIAT/IDB, 2021[16]).

VAT must adapt and modernise in line with an ever-evolving digital economy (Pineda and Gonzalez de Frutos, 2021[17]). Achieving correct and fair taxation of the digital economy could provide additional revenues, but faces key challenges in terms of VAT. The OECD’s VAT Digital Toolkit for Latin America and the Caribbean is useful in this context. By its very nature, the digital economy is constantly evolving and innovating with new forms of doing business and buying products and services, meaning that current legislation can easily fall behind. Similarly, and in particular in the case of VAT, providers are not always located in the same country where the product or service is consumed (and where the VAT is collected), complicating the taxation of the sale. Therefore, innovative solutions are needed for better collection of VAT, as outlined in the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project Explanatory Statement (OECD, 2015[18]). There are two key options: first, reduce or eliminate VAT exemptions on imports of low-value goods. These exemptions were designed to avoid an overload of customs but are no longer a problem thanks to the development of technology. Second, apply the OECD’s vendor model, which consists of the supplier (“vendor”) of these goods, or the digital platform or another intermediary that intervenes in the supply, being liable for collecting the VAT and remitting it to the jurisdiction of taxation (OECD/WBG/CIAT/IDB, 2021[16]).

Alternative and innovative policies should also be kept in mind as possible means of raising further revenues from VAT. For example, personalised VAT is a policy that has been used by other LAC countries to compensate low-income taxpayers and reduce the regressive nature of VAT. As a means of reducing these inefficiencies and encouraging formalisation, countries such as Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Uruguay have introduced personalised VAT, which consists of refunding VAT paid to targeted population groups. This refund can be total or partial and can be structured as a refund or as compensation (Barreix et al., 2022[19]). Simulations suggest that the incidence of VAT would be proportional to the level of income. In the case of the Dominican Republic, the use of personalised VAT in 2018 would have resulted in the lowest income decile contributing 0.05% of GDP instead of 0.10%, while the highest income decile would have contributed 0.97% of GDP instead of 0.64%. In terms of successful implementation of personalised VAT, the Dominican Republic’s access to digital technologies and information, and expanded use of the e‑CF, is essential (Barreix et al., 2022[19]).

Excise taxes represent the second-largest source of indirect taxes in the Dominican Republic, although their importance has diminished in the last decades. Excise taxes are commonly used to raise revenues and to discourage the consumption of specific products and services. The Dominican Republic levies two types of excise taxes: the Impuesto Selectivo al Consumo (which is a selective consumption tax,ISC), and a selective tax that depends on the value of the product. These taxes levy revenues on specific products or services, such as tobacco products, hydrocarbons, alcohol, telecommunication services and wire transfers. In 2020, taxes on specific goods and services accounted for 23.9% of total taxes (or 3.0% of GDP), higher than the LAC average of 15.9% in terms of total taxes, but below it in terms of share of GDP revenue (3.5% of GDP). The role of taxes on specific goods and services has considerably diminished in the Dominican Republic: in 1990 they accounted for more than one-half of total revenue. More than 50% of these revenues come from taxes on fuels and petroleum derivatives, while about 35% is derived from alcohol and tobacco (OECD et al., 2022[4]). In the case of fuel, there is space to increase revenues, as the fuel excise tax rates in the Dominican Republic are below the OECD average; for example, its tax rate on gasoline is USD 1.45 (United States dollars) per gallon, considerably below the OECD average of USD 2.24 per gallon (World Bank, 2021[20]).

Revenues from personal income taxes are limited due to a narrow tax base and the impact of widespread informality

Taxes on income and profits accounted for almost one-third (33.7%) of total tax revenues in 2020 in the Dominican Republic, higher than the LAC average (26.9%) and slightly lower than the OECD average (33.1%, registered in 2020) (OECD et al., 2022[4]). Of these revenues from taxes on income and profits in the Dominican Republic, 30.5% corresponded to personal income tax (PIT) and 47.1% to corporate income tax (CIT), these being the two main sources of direct taxation.

Revenues from PIT are relatively low by international standards, suggesting a potential area for improving tax collection. Since 2000, PIT in the Dominican Republic has remained below 11% of total tax revenues, increasing slightly from 8.5% in 2000 to 10.5% in 2020. This is less than half the average share of tax revenues from PIT in OECD member countries (24.1%) and is similar to the average share of PIT revenues in LAC (9.7%) (Figure 4.3, Panel A). PIT revenues represented 1.3% of GDP in the Dominican Republic in 2020, well below the averages in LAC (2.2%) and in OECD member countries (8.3%) (OECD et al., 2022[4])(Figure 4.3, Panel B).

Several factors limit PIT revenues in the Dominican Republic. These include a small tax base, a high concentration of income earners at low income levels, and high levels of informality and tax evasion.

Expanding the PIT tax base represents a challenge for various reasons. While lowering the minimum taxable personal income threshold could be a possibility, the viability and desirability of this option should be carefully analysed in a country where 57% of the workforce is informally employed (see Chapter 3), most of which have relatively low levels of income. In this respect, making sure that specific groups pay taxes, for instance those who are in informal but still earn relatively high levels of income will be vital. In fact, the estimated rate of PIT non-compliance was 57.1% in 2017, which represents around 1.7% of GDP (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2018[12]). Utilising new technologies (e.g. large-scale automated data) to cross-check PIT with information from online vendors could help reduce tax evasion (World Bank, 2021[20]).

Rationalising tax exemptions, deductions or credits could also increase the tax base and PIT revenues. The existence of generous exemptions, deductions or tax credits also limits the tax base. These include exemptions on travel allowances, Christmas bonuses, deductions on education, contributions to social security, and for those who contribute to the Solidarity Fund for Cultural Patronage (World Bank, 2021[20]).

Innovative PIT policies could be a useful tool for increasing formalisation and expanding the tax base, and hence tax revenues. For instance, negative income tax (NIT) or the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) are good examples of innovative tools that could generate fewer distortions or disincentives to formalisation than traditional tools. For individuals who are unemployed or informally employed, NIT guarantees revenue from a traditional cash transfer. The main advantage to this is that someone who is employed in the formal sector will continue to receive government aid, plus their salary. The benefits only fade gradually as wages begin to increase and the worker stops receiving support and begins to pay income tax. This type of programme guarantees that wages are higher in the formal sector, and is much more affordable than universal basic income, as it is targeted at a specific population and not at all individuals (Pessino et al., 2021[21]).

CIT is a main source of tax revenue, but this can impose a high burden on some domestic firms outside Free Trade Zones

CIT is one of the main sources of tax revenues collected in the Dominican Republic. Tax revenues from CIT account for 15.6% of total tax (2.1% of GDP), which makes it the second-largest source of tax revenues after the ITBIS (Figure 4.3). CIT has been on the rise since 2010, when it represented 8.8% of total taxes (1.1% of GDP), but CIT revenues as a percentage of GDP are substantially lower in the Dominican Republic than the averages for LAC (3.6% of GDP) or OECD average (2.8% of GDP) (OECD et al., 2022[4]). The increase in CIT revenues happened despite the decrease in the statutory tax rate from 29% in 2011 to 27% in 2015, where it has since remained. This tax rate is near the 28% average in the LAC region but above the 22% average among OECD countries. The increase in CIT revenues despite falling rates can be partly explained by recent reforms that aimed to reduce distortions and widen the tax base (World Bank, 2021[20]).

The corporate tax rate in the Dominican Republic is near the LAC average, yet CIT efficiency levels are low. CIT efficiency refers to the actual CIT revenues that are collected relative to the potential CIT that could be raised, and is calculated as a ratio of actual CIT revenues as a share of GDP by the weighted average of the statutory tax rate. Of the LAC countries where the efficiency rate has been calculated, the Dominican Republic lags behind Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay, and only outperforms Ecuador and Guatemala. Increasing the revenue efficiency of the Dominican Republic’s CIT to the LAC average would boost revenue collection by an estimated 0.9% of GDP (World Bank, 2021[20]).

Low CIT revenues and efficiency can be explained by the proliferation of tax incentives and high tax evasion. The Dominican Republic has traditionally used tax incentives to attract investment, such as via Free Trade Zones (FTZs). Tax incentives are targeted tax provisions that provide favourable deviations from the standard tax treatment and can take many different forms and designs (Celani, Dressler and Hanappi, 2022[22]) (Box 4.1). Sectors that have benefited from tax incentives include mining, forestry, energy, tourism and border development areas.

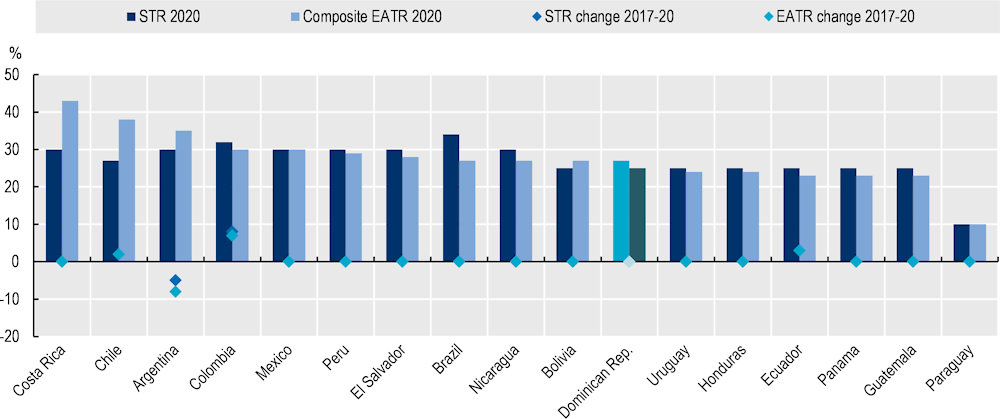

Generous tax treatment measures can reduce the actual tax liabilities faced by companies and can be usefully assessed through a forward-looking effective tax rate (ETR) (Hanappi, 2018[23]). The ETR differs from the statutory tax rate because the rules of fiscal depreciation, a number of related provisions (e.g. allowances for corporate equity, half-year conventions and inventory valuation methods) and tax incentives might reduce tax liabilities (OECD, 2020[24]).1 The Dominican Republic’s effective average tax rate (EATR), excluding incentives, is 2.2 percentage points lower than the statutory rate (Figure 4.5). This is similar to other LAC economies, such as Guatemala (1.9 percentage points lower than the statutory rate), Colombia (1.9 percentage points lower), Nicaragua (2.8 percentage points lower) and Brazil (6.7 percentage points lower), indicating generous corporate tax bases (Botey et al., forthcoming[25]). Providing generous tax incentives can result in much lower ETRs (Box 4.2). Moreover, corporate tax evasion in the Dominican Republic is as high as 61.9%, or a tax gap of 4.2% of GDP (see Section on Fighting Tax Evasion) (ECLAC, 2020[26]; Ministerio de Hacienda, 2018[12]).

Figure 4.5. EATRs in LAC, excluding incentives

Note: STR refers to standard statutory rate. EATR refers to effective average tax rate.

Source: Botey et al. (forthcoming[25]).

Box 4.1. Building an Investment Tax Incentives Database

Tax incentives for investment are frequently used worldwide, including in LAC countries. Tax incentives are targeted tax provisions that provide favourable deviations from the standard tax treatment in a country. They can potentially promote investment and positively affect output, employment, and productivity, or other objectives related to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). If poorly designed, they may be of limited effectiveness and could result in windfall gains for projects that would have taken place regardless of the incentives. Tax incentives can also reduce revenue-raising capacity, create economic distortions, increase administrative and compliance costs, and potentially increase tax competition. Striking the right balance between an efficient and attractive tax regime for domestic and foreign investment and securing the necessary revenues for public spending and development is a particular concern in developing countries.

The widespread use of tax incentives globally, along with concerns about their net impact, is an important policy concern for national governments and the international policy community. Recent OECD research provides insights into tax incentive policies and increases the policy relevance of tax incentive analysis, with the objective of helping policy makers make smarter use of tax incentives and reform inefficient ones.

The OECD Investment Tax Incentives Database (ITID) systematically compiles quantitative and qualitative information on the design and targeting of CIT incentives across countries using a consistent data collection methodology. For each tax incentive, the ITID includes information along three dimensions (Figure 4.6): instrument-specific design features, eligibility conditions, and legal basis. As of July 2021, the database covers 36 developing countries in Eurasia, the Middle East, North Africa, Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Future additions to the ITID could include LAC countries.

Figure 4.6. Key dimensions of the OECD ITID

(Celani, Dressler and Wermelinger, 2022[27])present the methodology and key classifications underlying the ITID and provide the first descriptive statistics based on information from the 36 included countries. Tax incentive designs are multidimensional, complex, and often specific to a certain sector, region or investor within a country. Adjusting design features of incentives in specific contexts can improve tax incentive policy making by, for example, improving effectiveness or limiting forgone revenue. However, this also reduces transparency and can have unintended effects. ETR analysis can help make complex features of tax incentives comparable (Box 4.2) and is an additional step towards developing policy guidance based on detailed information from the ITID.

Source: Elaboration based on (Celani, Dressler and Wermelinger, 2022[27]).

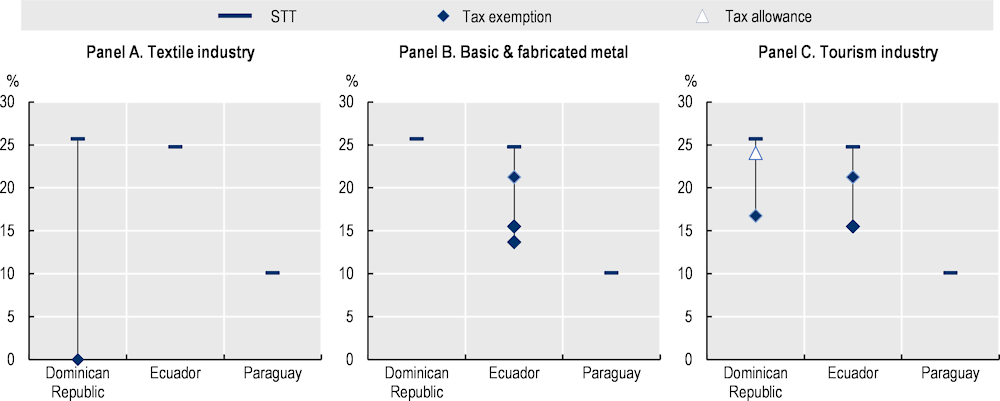

Box 4.2. Assessing tax incentives for investing in LAC using ETRs

As in most countries around the world, governments in LAC countries frequently use tax incentives to reduce the tax costs of investment in specific activities, sectors and locations. Comparison of preferential tax treatments is not straightforward, as tax incentive designs and targeting strategies are complex and multidimensional. Tax incentive analysis should account for such complexities and evaluate them jointly with standard tax system features, as these provide the starting point with respect to which incentives provide relief, and can vary across countries. ETR-based analysis can capture the combined effects of the standard tax system and tax incentive designs. It allows comparison between the effective tax costs associated with a given investment across locations, sectors and activities. The OECD is currently conducting new research to extend the ETR methodology for estimating ETRs under tax incentives in order to evaluate the incentives’ effect on providing tax relief and to develop recommendations for policy reform (Celani, Dressler and Hanappi, 2022[22]).

This box illustrates how the ETR framework can be useful in analysing investment tax incentives. It presents ETRs for a standardised investment project in three industries (textiles, metals and tourism) in the Dominican Republic, Ecuador and Paraguay. Figure 4.7 presents ETRs under standard tax treatment, i.e. excluding tax incentives (denoted by the horizontal black marker) and accounting for industry-specific tax incentives, if available. The blue diamonds represent tax exemptions and the white triangles represent tax allowances. Multiple markers in a specific country and industry indicate that various incentives apply, depending on additional eligibility conditions. For example, investment in tourism in Ecuador (Panel C) benefits from a ten-year tax exemption when located in an Economic Special Development Zone and a five-year exemption otherwise.

Investment tax incentives lower the tax costs of investment to various degrees across the three industries and countries. While the Dominican Republic and Ecuador start from a 25% standard ETR, they offer tax incentives that substantially lower effective taxation in some industries. For example, ETRs can be as low as 0% in the Dominican Republic’s textile industry and up to 45% lower than standard taxation in Ecuador’s metal industry (13.7% compared with 24.8%). While Paraguay does not use CIT incentives, it applies a relatively low standard CIT rate, reaching the lowest ETR in the three countries’ metal and tourism industries.

Figure 4.7. Investment tax incentives lower ETRs across industries

EATR under standard tax treatment (STT) and investment tax incentives in the corresponding

Note: This figure considers investment tax incentives and STT on 1 January 2020. EATRs are calculated for a standardised investment in a single non-residential building asset. STT considers country-specific standard CIT rates, asset-specific capital allowance rates and cost recovery method. Temporarily or permanently tax-exempt income does not give rise to standard capital allowances.

Source: Authors’ elaboration on (Celani, Dressler and Hanappi, 2022[22]).

As a member of the OECD/Group of Twenty (G20) Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS), the Dominican Republic has agreed on the two-pillar solution to address the challenges of digitalisation and globalisation. This two-pillar solution, which has been agreed by 135 countries and jurisdictions, aims to ensure that multinational enterprises (MNEs) pay their fair share in taxes. Pillar One aims to ensure a fairer distribution of profits and taxing rights among countries with respect to the largest MNEs, which are the winners of globalisation. Pillar Two aims to limit tax competition by putting a floor on CIT through the introduction of a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15% that countries can use to protect their tax bases. The new framework for international tax and the agreed Detailed Implementation Plan envisages implementation of the new rules by 2023 (OECD, 2021[28]).

Property and wealth taxes have great potential for expansion while improving the efficiency and equality of the system

Property taxes in the Dominican Republic account for a small proportion of total taxes levied. These taxes are an appropriate tool for taxing the wealthiest families and increasing the redistributive power of the tax system in a country where large inequalities persist. Indeed, recurrent taxes on property have been found to be among the least detrimental to growth and can have a positive impact on equity, while being difficult to evade due to the immobility of the tax base (O’Reilly, 2018[15]).

Property taxes accounted for 0.7% of GDP (or 5.0% of total taxes) in the Dominican Republic in 2020. Their main components are recurrent taxes on immovable property or real estate (11% of total property and wealth taxes), recurrent taxes on net wealth (18%), inheritance and gift taxes (2%), taxes on financial and capital transactions (62%), and other or non-recurrent taxes (7%) (OECD et al., 2022[4]). Immovable property and real estate taxes and inheritance and gift taxes are of special interest because of their potential to raise further revenues with low distortionary effects and high redistributive impact.

Real estate taxes and inheritance and gift taxes remain a potential revenue source for Dominican authorities. These account for 2% of total property taxes, well below the levels in OECD member countries, which average 7%. These taxes not only generate few changes in behaviour, as net wealth in later life is not sensitive to changes in inheritance tax, but can also be highly progressive and can generate greater equality of opportunity. Gifts, for example, are highly tax responsive and are not commonly used as a strategy for reducing inheritance taxes. A main advantage of these types of taxes is that they are relatively easy to levy, as the tax is levied at the time that the property or inheritance is transferred. Given the low levels of tax revenue from these types of taxes in the Dominican Republic, it could be worth strengthening their design and implementation and rationalising the exemptions. Although the political costs of this kind of reform can be high as it mostly affects the elites, in a context of growing inequalities and social unrest, it can have clear benefits, especially in a situation of low tax morale and low trust in institutions (OECD et al., 2019[29]; Pineda et al., 2021[30]; OECD, 2019[31]; Jiménez et al., 2021[32]).

Taxes on immovable property accounted for 0.06% of GDP in 2020 (11% of total property and wealth taxes) in the Dominican Republic. These taxes are low when compared with the LAC average of 0.4% of GDP, or with the average in OECD member countries of a little more than 1% of GDP. These figures suggest that there is still room for further improvements concerning property tax in the Dominican Republic (OECD et al., 2022[4]).

A number of factors undermine tax revenue from immovable property in the Dominican Republic. There is a low level of property registration due to high levels of informality, which erodes the tax base. The tax base is also eroded by high threshold exemptions (all properties below DOP 8 138 353.26 (Dominican pesos) are exempt, almost the average price of a two- or three-bedroom house in Santo Domingo). Similarly, only urban properties are required to pay property tax, and foreign property investments in selected tourist zones are also exempt. The lack of a unified and easy-to-access property registry results in a system with high transaction costs and creates uncertainty among the business sector, hampering investments. Two systems coexist simultaneously: the Title Registry (Registro de Títulos), also known as Sistema Torrens Dominicano, and the Civil Registry and Mortgage Conservatorship (Registro Civil y Conservaduría de Hipotecas), also known as Sistema Ministerial. The Title Registry covers only 13% of total properties in the Dominican Republic, whereas the Mortgage Registry has better coverage but provides weaker legal protection. As only one out of every four properties is registered with the Directorate General of Internal Taxes (Dirección General de Impuestos Internos), a very low proportion of properties are taxed and property values are outdated.

Correct and up-to-date information alongside a capable tax administration are essential to unleashing the potential of immovable property taxes. The tax base for the immovable property tax is the appraised value that the local authorities calculate, but often the information that authorities have is outdated and thus differs from the market value. Therefore, reducing the gap between the appraised value and the market value is a key priority and an exercise in adjustment that needs to be regularly performed. This must be accompanied by an up-to-date land and property registration in central cadastres that makes real efforts to formalise informal settlements. Digital maps, aerial photographs or geographic information systems could also be useful tools. Colombia is a good example of a country where the tax base is determined by decentralised cadastral offices and is based on self-declaration in some cities. Any structural changes to the tax base must be accompanied by strengthening local tax authorities, a stronger co‑ordination with the national tax authority and the property registry, and rationalisation of tax exemptions (Ehtisham, Brosio, and Jiménez, 2019[33]; OECD et al., 2022[4]; World Bank, 2021[20]).

The efficiency of taxation on specific sectors (like energy) can be improved, and new taxes can be explored in areas like the digital economy or the green transition

In the Dominican Republic initiatives have already slowly started to create a framework for environmental taxes. For instance, at the end of 2012 the Dominican Republic introduced a tax concerning either new or used vehicles, which is determined based on carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration per kilometre. In addition to the existing rate of 17% for registration of the first licence plate, tax is calculated based on the declared value of the vehicle in Customs and on the CO2 emissions in grammes per kilometre, with rates of up to 3%. Other current initiatives include medium-term projects, such as Bono Verde to finance solid waste treatment or the 0.2% Green Tax on the import and production of goods with a high proportion of solid waste such as paper, wood, tires and batteries (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2018[12]).

The potential of environmental taxes (such as carbon taxes) needs to be balanced with measures to protect more vulnerable groups. Among the different tools available, carbon taxes are a simple and cost-effective way to limit climate change, increase tax revenues and limit health damage from local pollution (OECD, 2019[34]; OECD, 2021[35]). Other taxes (such as creating a tax for vehicles that are more than ten years old in order to protect the environment and biodiversity from pollution) offer a new opportunity to raise tax revenues and promote green growth. Moreover, a green tax, or Impuesto Verde, is currently being analysed as a selective tax on the consumption of final goods and intermediate goods that generate solid waste. A rate of 0.2% would be applied to the product for both imported and local goods in order to create a “green bonus”. The effects of climate change and green policies such as environmental taxes will further expose the most vulnerable, highlighting the need for compensation schemes. These schemes could include cash transfers, in-kind transfers and support for retraining.

The digitalisation of the economy has led to important challenges in business models and in the value-creation processes of companies. One proposal currently under discussion is to extend the 18% VAT (ITBIS), or the 10% Selective Consumption Tax, to digital platforms such as Netflix, Spotify, Uber, Cabify and Airbnb, as well as online gaming and data storage platforms. Estimates suggest that the potential of VAT revenue derived from taxes on digital services could have represented 0.4% of the Dominican Republic’s GDP in 2018, 0.5% in 2019 and 0.6% in 2020 (Jiménez and Podestá, 2021[36]). These efforts are essential not only for diversifying tax sources, but also for guaranteeing fair competition between these international platforms and local companies that provide these services.

Table 4.1. Strengthen tax revenues by restructuring the tax mix

|

Policy recommendation |

Challenges and opportunities for implementation |

|---|---|

|

1.1 Rebalance the tax structure to increase the share of direct taxes and increase progressivity |

|

|

Launch a technical and political discussion on the feasibility of decreasing the minimum taxable personal income, so that high-income deciles are effectively included. |

The country must calibrate and evaluate the sensitivity of the tax rates to reach an optimal balance between collection and equity. |

|

Explore the potential of personalised VAT (ITBIS) as a way of increasing the overall revenues from these taxes while compensating low-income taxpayers and thus reducing the regressive nature of VAT. |

In the implementation of new and innovative taxes, the increases in administrative costs will increase and must be considered. This due to the creation/adaptation and training of the area in charge of identifying the target population and carrying out the compensations. |

|

1.2 Enhance the revenue potential of other taxes |

|

|

Strengthen property registries in order to boost revenues from property taxes by: 1) moving towards a unified and simplified property registry with an up-to-date land and property registration in central cadastres, and 2) reducing information asymmetries in immovable property; closing the gap between the appraised value and the market value is a key priority and an adjustment that needs to be regularly performed. |

A fundamental action is to strengthen the cadastre department (update values) alongside a study to assess the cost-opportunities and calculate how much revenue is foregone. Similarly, Inter-institutional co-operation that allows obtaining the value of the properties in real time through an interconnection of databases will be essential. A proposal is to evaluate the strategy of having a graduated rate for IPI (real estate tax), which increases according to the aggregate value of the properties owned. This would entail a change in legislation, as well as internal measures to detect irregularities and potential evasion of this tax. |

|

Explore the potential of new taxes adapted to the emerging economy, such as digital and green taxes, which serve the dual purpose of raising revenues while creating the incentives for a greener and more digitalised development model. |

In the case of green taxes, it will require an amendment of the tax code law, national consensus backed by strong political will (see section and recommendations on fiscal pact). |

Note: Based on the meeting held on 23 June 2022, to discuss the draft analysis and policy recommendations with officials from the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Economy, Planning and Development (MEPyD), the Central Bank, the National Statistics Office (ONE), the World Bank, the IDB and the European Union.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Rationalising tax expenditures can create fiscal space and improve the overall impact of the tax system in terms of equity and efficiency

Tax expenditures represent the amount of forgone revenue as a result of special tax provisions that reduce or eliminate the tax liability for specific individuals, economic sectors or businesses. Tax expenditures can be defined as “resources not collected by the state, due to the existence of incentives or benefits that reduce the direct or indirect tax burden of specific taxpayers in relation to a benchmark tax system, in order to achieve certain economic or social policy objectives” (CIAT, 2011[37]). These tax expenditures are typically used by governments to achieve different economic, social and equity objectives by providing specific conditions to incentivise behavioural change. Tax expenditures take the form of exclusions, exemptions, allowances, credits, reduced rates or tax deferrals.

Figure 4.8. Tax expenditures in selected LAC countries as a percentage of GDP, 2021 or latest year available

Source: Authors’ calculations based on national sources, (Redonda, von Haldenwang and Aliu, 2021[38]) and (Peláez Longinotti, 2019[39]).

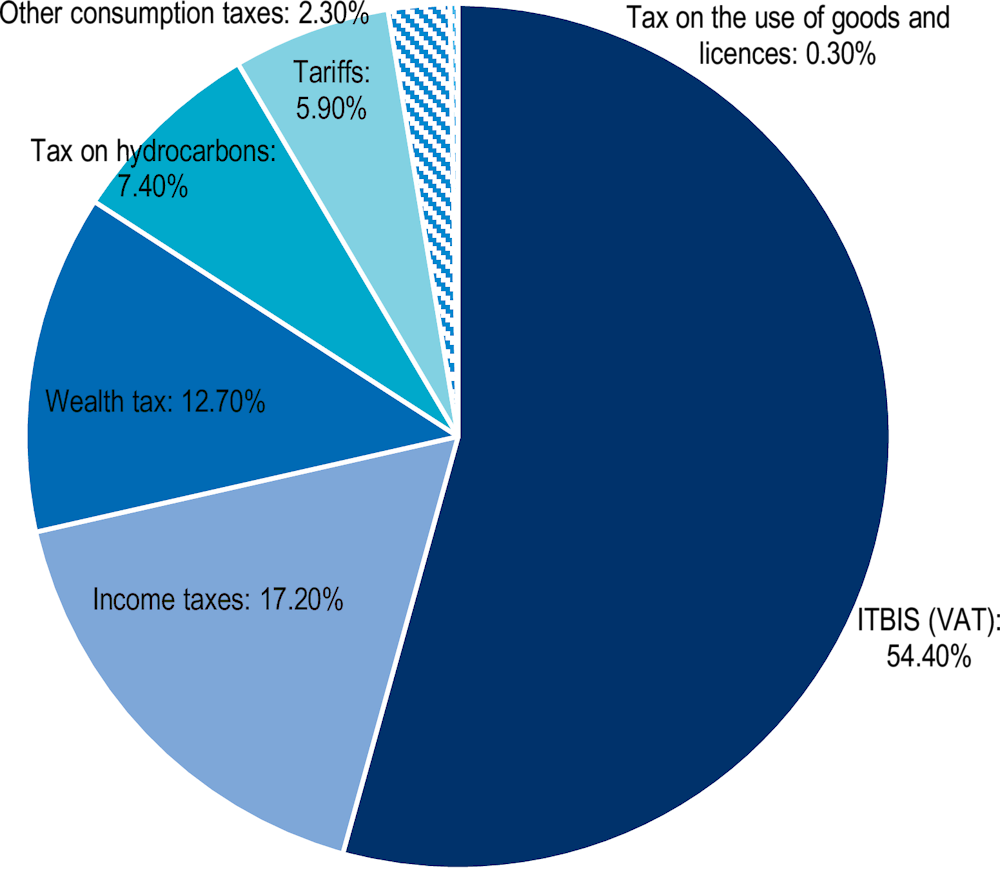

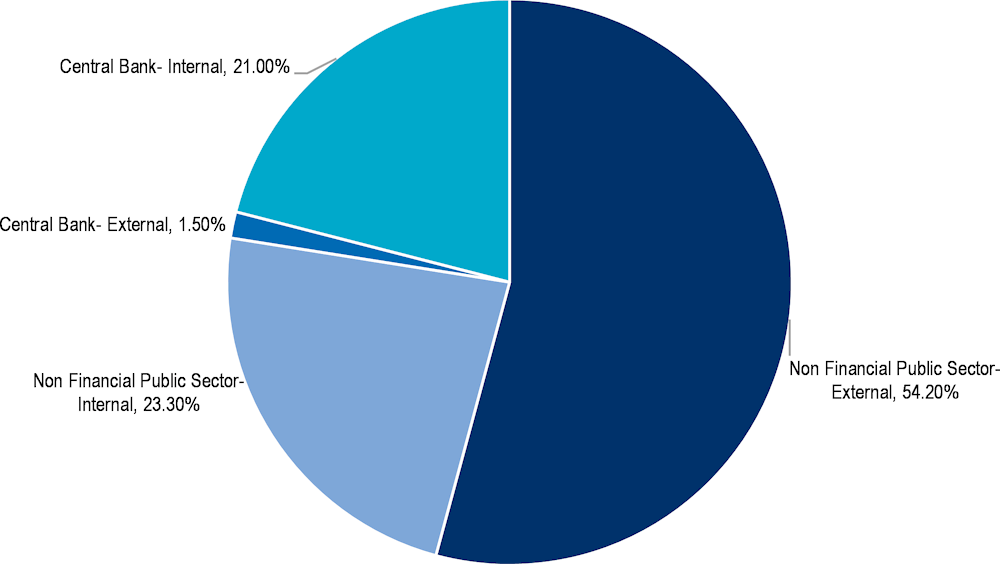

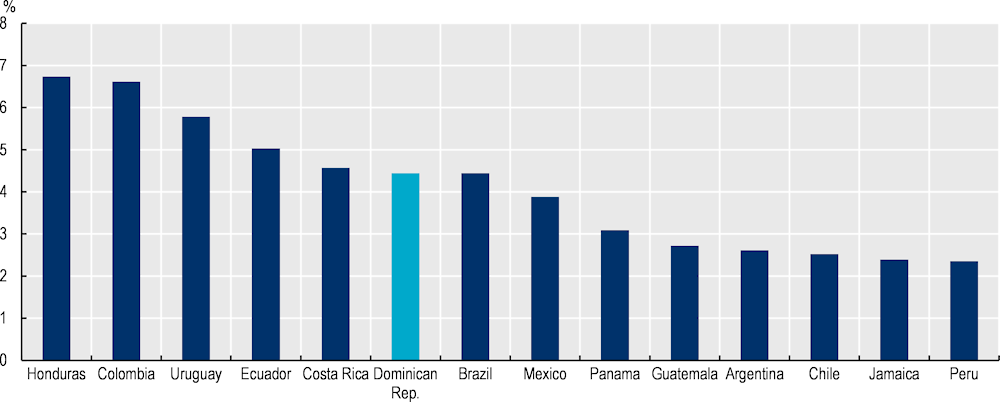

Tax expenditures represent a significant amount of financial resources in the Dominican Republic. In 2020, tax expenditures accounted for 4.6% of GDP, one of the highest levels in the LAC region (Figure 4.8). Most tax expenditures in the Dominican Republic are associated with indirect taxes. In 2021, as much as 70.1% of tax expenditures came from indirect taxes, with the majority of them related to the ITBIS (54.4% of total tax expenditures) and taxes on hydrocarbons (7.4%) (Figure 4.9). Tax expenditures from direct taxes represented the remaining 29.9% of total tax expenditures, and was split between income taxes (17.2% of total tax expenditures) and wealth tax (12.7% of total tax expenditures). Tax expenditures from the ITBIS represented 2.41% of GDP, and all tax expenditures from indirect taxes accounted for 3.12% of GDP, while those resulting from direct taxes represented 1.32% of GDP, divided between 0.76% of GDP from income taxes and 0.56% from wealth and property tax (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2020[40]).

In a country where tax revenues as a share of GDP are low (and among the lowest in the LAC region), exploring the potential to rationalise these tax expenditures is critical. Indeed, the narrow tax base observed in the Dominican Republic is partly the result of widely implemented tax provisions, which are often not well designed or targeted. This can lead to regressive tax expenditures that provide greater benefits to those who need them less, or that are not conducive to job creation or economic growth. Likewise, the proliferation of tax expenditures increases the complexity of the tax system, creating greater opportunities for evasion and tax planning. In sum, tax expenditures can undermine tax revenue collection, increase inequalities, reduce efficiency and add complexity. A reform or the elimination of outdated, poorly targeted tax expenditures that do not achieve the associated policy objectives can be a source of greater tax revenue by broadening the tax base while supporting a more effective, equal and simple tax system.

Figure 4.9. Tax expenditure breakdown, as a percentage of total tax expenditures, 2021

There is room to evaluate the distributional and efficiency implications of tax expenditures in the Dominican Republic. In the case of the ITBIS, which is the main source of tax expenditures (Figure 4.9), around 88% of tax expenditures in 2013 benefitted higher-income groups (World Bank, 2019[41]). There is scope to reconsider exemptions of non-essential goods and services; for instance, those related to tourism or certain cultural products. This could increase tax revenues from the ITBIS. Other exemptions could also be re-evaluated, as long as their potential elimination is accompanied by measures to support and compensate the most vulnerable groups, such as direct cash transfers or targeted reductions of social security contributions.

A non-negligible share of tax expenditures is derived from income taxes (Figure 4.8). Regarding PIT, there is scope for reconsidering some of these exemptions, particularly because these taxes tend to be progressive in nature, meaning that tax provisions in this domain can limit their positive distributional impact (OECD/DIAN, 2021[42]; Solidaridad, 2018[43]).This is the case in the exemptions on expenditure in education, which have the rationale of incentivising investment in education but can end up benefitting people with higher levels of income, as evidence points to wealthier people making greater use of these advantages (OXFAM, 2020[44]).

When examining tax expenditures from the perspective of productive sectors of the economy, FTZs, power generation, tourism and mining account for the largest share, altogether representing 23.8% of the total tax expenditure expected in 2021 (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2021[3]). FTZs and special zones in border regions provide particularly strong privileges to the firms operating in these areas of the country, significantly undermining CIT revenues. In 2020, 692 firms were part of Free Trade Zones, contributing 3.2% of the GDP; these firms were mostly concentrated in services (23.4% of total firms), tobacco and derivatives (14.3%), textiles (12.6%) and agroindustrial products (7.8%) (CNZFE, 2021[45]). FTZs account for 13.5% of total tax expenditures in the Dominican Republic, while tourism accounts for 3% and mining accounts for 1.8%. These exemptions represent a cost of around 1.8% of GDP and also include fuel for electricity generation, imports for production in FTZs, and some taxes on property. Within this share, FTZs account for 0.6% of GDP and exemptions within the tax on hydrocarbons for electricity generation represent 0.4% of GDP (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2021[3]).

The advantages granted to firms in FTZs and other special tax regimes raise an important question about whether they generate more benefits than costs and, consequently, whether there is scope to restructure some of these tax regimes in order to increase the tax base and overall tax revenues. Several studies have been conducted in the Dominican Republic to evaluate the convenience of these regimes, with mixed results. The World Bank (2017) used administrative data on income tax declarations in order to assess the net benefits of totally exempting firms in FTZs in the Dominican Republic from paying CIT. The results showed that while these firms create a greater number of jobs compared with those that are not part of this special regime (FTZs create three times more employment than non-FTZ firms), that job creation comes at a very high cost: each of those jobs costs five times more in terms of revenue forgone. In addition to this, the Inter-American Center of Tax Administrations (CIAT) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN‑DESA) (2018) conducted a cost–benefit analysis using administrative data on tax incentives for the tourism sector from 2002 to 2015. The conclusions of this study pointed out that the negative impact of the costs of these tax incentives on GDP is greater than the benefits. Investment in infrastructure rather than fiscal incentives would definitely be more profitable for both the tourism sector and economic growth. More recently, a cost-benefit analysis of the FTZs concluded that, at the aggregate level, this regime has an average net positive annual contribution of 2.7% of GDP, including the direct and indirect effects (Cardoza, Vidal and Taveras, 2019[46]). However, when the results are analysed at the company level, around 16% of all companies operating in FTZs create greater tax expenditures than benefits, suggesting that a more granular evaluation of these tax regimes can help identify specific firms or sub-sectors whose participation in them is not justified.

Periodical assessments are needed in order to continuously evaluate the distributional and efficiency implications of tax expenditures. The Dominican Republic’s Ministry of Finance already publishes tax expenditure reports, providing a good overview of forgone revenues. However, the analysis could be further developed to more explicitly present how tax expenditures contribute to the policy objectives they were designed to achieve, including economic growth, job creation or supporting lower-income groups. If the social benefits of these tax expenditures are not greater than the social costs, or if there is a better mechanism through which to deliver those benefits, then the tax expenditures should be reconsidered. Similarly, in the case of special tax regimes, regular cost–benefit analyses should be conducted in order to carefully evaluate their contribution to achieving policy objectives, given that these are a major source of forgone tax revenues that need well-grounded justification. In the Dominican Republic, information on the net benefits of these special tax regimes is scarce and should be expanded to all special regimes.

Avoiding arbitrariness in the criteria for admitting firms into FTZs and other special tax regimes by setting up clear qualification conditions can be an effective policy for limiting the forgone tax revenue as a result of the FTZ special tax regime. In this respect, the governance of special economic regimes must also be redesigned so as to reduce the excessive influence of private interests, which tend to shape the criteria in their favour in order to perpetuate their advantageous position. Once implemented, these systems generate significant benefits for the recipients, thus serving vested interests with a particular motivation to keep the incentives in place and to make their modification extremely difficult (Daude, Gutiérrez and Melguizo, 2014[47]). Including all tax expenditures in the tax code, or giving the Ministry of Finance responsibility for granting all these incentives, could be effective methods of reducing arbitrariness.

Table 4.2. Rationalise tax exemptions to raise revenue capacity and improve the overall impact of the tax system in terms of equity, efficiency and simplicity

|

Policy recommendation |

Challenges and opportunities for implementation |

|---|---|

|

2.1 Rethink tax exemptions on main sources of revenue |

|

|

Rethink VAT (ITBIS) exemptions in order to improve efficiency and reduce its regressive impact – for example, exemptions applied to financial services or to the imports of low-value goods, or exemptions on certain non-essential goods and services such as those related to tourism or certain cultural products. Measures aimed at reducing VAT exemptions should be accompanied by clear measures to compensate lower-income groups, such as direct cash transfers or the targeted reductions of social security contributions. |

It would be of key importance to periodically and accurately estimate the corresponding fiscal sacrifices and political/social costs of eliminating or implementing tax exemptions. |

|

Evaluate PIT deductions, such as exemptions for educational expenditure, which can be regressive |

It was suggested than rather tax exemptions, it would be better to apply a general tax and compensate possible affected sectors. |

|

2.2 Evaluate the overall impact of special economic regimes and consider a gradual phasing out of those where the costs – in terms of forgone tax revenues – outweigh the benefits |

|

|

Rethink tax incentives associated with special economic regimes through periodical assessments in order to ensure that their distributional and efficiency implications are evaluated regularly. |

Reconsidering the tax incentives should consider the legislative and political/social costs. |

|

Include an analysis in tax expenditure reports of how these incentives contribute to key development objectives such as economic growth, job creation or supporting lower-income groups. |

A cost-benefit methodology similar for tax expenditures is needed, and to be used and published periodically. In that sense, Law 253-12 must be enforced (the law establishes that the governmental institutions that administer laws that contemplate exemptions or exonerations must submit to the Ministry of Finance to undergo a cost-benefit analysis of the incentives). |

|

Limit the potential arbitrariness associated with special economic regimes by, for example, strengthening the criteria for admitting companies; rethinking the governance of these regimes in order to balance the distribution of power; including all tax expenditures in the tax code; or giving the Ministry of Finance the main responsibility for granting all these incentives |

The criteria and institutions that admit companies to these special regimes might need to be re-examined. Similarly, it is important to follow up on the exemption periods granted. |

Note: Based on the meeting held on 23 June 2022, to discuss the draft analysis and policy recommendations with officials from the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Economy, Planning and Development (MEPyD), the Central Bank, the National Statistics Office (ONE), the World Bank, the IDB and the European Union.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Fighting tax non-compliance can be a source of greater tax revenues, while making the tax system more equitable and fair

Tax non-compliance in the Dominican Republic ranks among the highest in the LAC region, and addressing this could be an important source of greater tax collection. Estimated tax non-compliance in the Dominican Republic in 2017 was 61.8% (4.2% of GDP) for CIT and 57.07% (1.68% of GDP) for PIT (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2018[12]). Concerning the ITBIS, tax non-compliance reached 43.5% in 2017, representing 3.6% of GDP (Figure 4.10). In general, tax non-compliance in the Dominican Republic ranks among the highest in the LAC region, although high heterogeneity is observed across countries. In 2017, tax non-compliance for VAT ranged from 14.8% in Uruguay to 45.3% in Panama, while levels in the European Union were as low as 11.5% (Gómez Sabaini and Morán, 2020[48]). Similarly, in 2017 tax non-compliance for PIT ranges from 18.7% in Mexico to 69.9% in Guatemala, and for CIT it ranges from 19.9% in Mexico to 79.9% in Guatemala (Gómez Sabaini and Morán, 2020[48]).

Figure 4.10. Estimated tax loss from VAT non-compliance, 2017 or latest available year (in percentage of GDP)

Recent efforts and experiments to tackle tax non-compliance show that there is room for effective, short-term measures. The Central Tax Administration made attempts to launch coercive policies and initiatives to fight against terrorism financing (which included tax evasion measures) in 2018. Law 155-17 against Money Laundering and Terrorism Financing was approved by the National Congress in 2017, enacted by the President in November 2017 and enforced by the Dominican Republic’s Ministry of Finance from 2018. This law sought to curb tax evasion and other tax-related violations with severe criminal punishments, including prison and substantial monetary fines. Among measures to control tax evasion, the Dominican Republic’s Ministry of Finance increased the number of audited taxpayers, resulting in the probability of being audited increasing from 8% in 2017 to 12% in 2018 (Holz et al., 2020[49]). In order to increase tax morale, high-profile public servants have highlighted the success and accomplishments of this law, and the media widely reported on the imprisonment, preventive detention trials, house arrests, electronic monitoring devices and travel restrictions imposed on taxpayers accused of tax evasion (Holz et al., 2020[49]).

Information campaigns and efforts to raise awareness can have an impact on lowering tax non-compliance. A field experiment conducted in the Dominican Republic put in place a number of “nudges” and assessed their impact on tax compliance among both companies and individuals (Holz et al., 2020[49]). These nudges consisted of sending messages to more than 28 000 self-employed workers and more than 56 000 firms describing prison sentences and publicly announcing tax evaders, and these were found to increase tax compliance, mainly through the channel of decreasing the amount of tax exemptions claimed. The results of the experiment also showed that firm size is a determinant in the effectiveness of the nudges: larger firms were more responsive to the nudges than smaller firms were. Overall, the messages increased tax revenue by USD 193 million (around 0.23% of the Dominican Republic’s GDP) in 2018, of which more than USD 100 million could be attributed solely to the experiment on nudges. This initiative underlines the extent to which a deeper understanding and consciousness of taxpayers could influence their behaviour.

The simplification of the tax system can be beneficial in fighting tax non-compliance, particularly among firms. The existence of multiple tax regimes for different sectors allows firms to undergo aggressive tax planning in order to avoid paying taxes by exploiting gaps and mismatches in the tax rules. These tax planning strategies are not only done locally, but also on an international scale, as businesses artificially shift profits to low- or no-tax locations where there is little or no economic activity, or they erode tax bases through deductible payments such as interests or royalties. This international challenge is addressed by the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS. This framework includes 135 countries and jurisdictions – including the Dominican Republic, which has been a member since 2018 – and outlines 15 domestic and international actions that governments must take in order to tackle tax avoidance. Since its enrolment, the Dominican Republic has participated in many of the associated agreements and actions (such as those related to addressing the challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy, strengthening the transfer pricing legislation to align with OECD standards, and setting requirements for of tax and financial information by MNEs), but it still has to address the existence of possible harmful tax regimes in the country, which are currently being revised or amended. The Dominican Republic has made progress on the implementation of the transparency standard from the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes, and is considered largely compliant with this standard.

Table 4.3. Fight tax non-compliance

|

Policy recommendation |

Challenges and opportunities for implementation |

|---|---|

|

3.1. Use digital tools to fight evasion and to leverage existing international agreements |

|

|

Launch information campaigns, increase efforts to raise awareness, and use nudges, all of which can have an impact on lowering tax non-compliance. |

The country must encourage a tax paying culture through voluntary contributions. To achieve it, taxpayer education (both taxpayers and internal staff), alongside educational campaigns will be essential. |

|

Use new technologies to cross-check information (for example, large-scale automated data and cross-checking of PIT against information from online vendors), as this could help reduce tax evasion. |

The Use of electronic invoicing (e CF) has increased compliance and bill was introduced to expand its coverage and make it mandatory for large companies as of January 2023 Administrative and technological costs of implementing automation should be considered and properly planned. In the case of new technologies, documented examples from other countries must be used. A possible revision of the regulation that regulates the procedure for the application of ITBIS to digital services received in the Dominican Republic and provided by foreign suppliers might be needed. |

Note: Based on the meeting held on 23 June 2022, to discuss the draft analysis and policy recommendations with officials from the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Economy, Planning and Development (MEPyD), the Central Bank, the National Statistics Office (ONE), the World Bank, the IDB and the European Union.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Improving the quality of public spending to enhance its impact on well-being

Public spending plays a key role in development by providing basic public services, decreasing inequalities, protecting vulnerable populations and investing in essential infrastructure to promote inclusive growth. Spending in the form of cash transfers can reduce poverty and inequality in the short term, an important factor in the present day. Effective social spending can also provide a buffer for vulnerable populations, giving them at least partial protection in case of an economic, social or environmental shock (Zouhar et al., 2021[50]). Public spending also plays an important role in providing security, education and healthcare for all, which can reduce inequality and poverty in a country. Investment projects can help a country realise long-term goals for instance by improving infrastructure. The COVID‑19 pandemic forced a strong response from the government of the Dominican Republic, with significant public spending increases. However, this can also be taken as an opportunity to revisit the mechanisms for spending and to prioritise efficient spending that aligns with development goals and has a lasting positive impact.

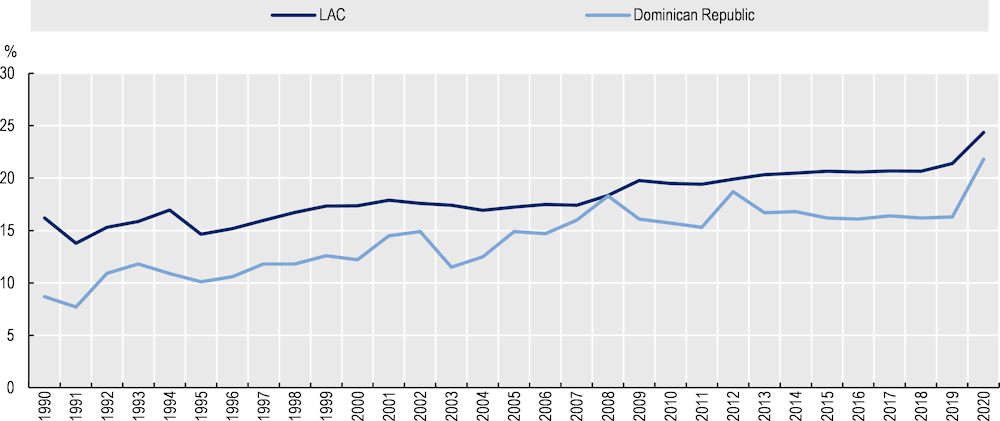

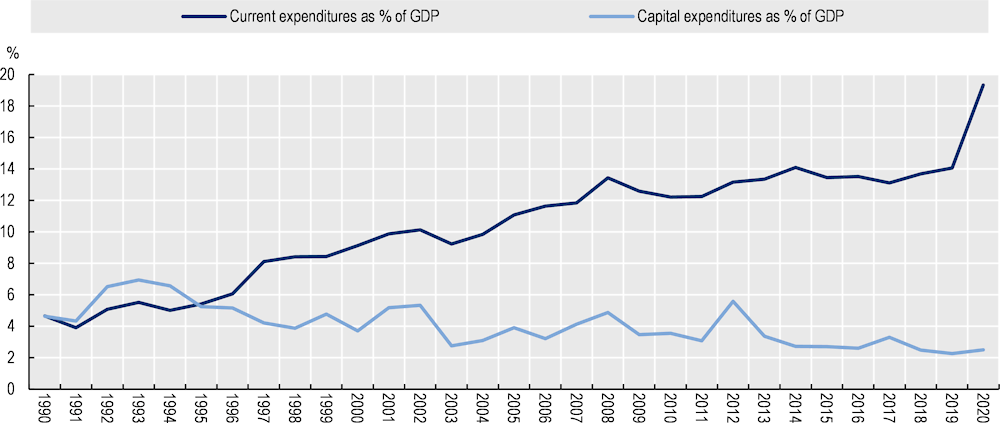

Public spending in the Dominican Republic has recorded sustained growth in the last decades, but has persistently remained below LAC average levels

Public spending in the Dominican Republic has trended steadily upward in the last decades, with a notable spike due to COVID‑19; between 1990 and 2019, public spending increased from 8.7% of GDP to 16.3%. However, the country’s public spending as a share of GDP has consistently been below the LAC average, which was 21.4% of GDP in 2019 (Figure 4.11). Disparities across the region in levels of public spending are large, with countries like Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Uruguay regularly spending over 20% of GDP on public programmes and services in the years prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Figure 4.11. Evolution of public spending in the Dominican Republic, 1990‑2020

The crisis induced by the COVID‑19 pandemic demanded a large increase in public spending in order to finance the necessary health, economic and social protection measures. As a result, public spending as a share of GDP rose dramatically by 5.5 percentage points, reaching 21.8% of GDP in 2020. In LAC, the average public spending as a share of GDP increased to 24% in 2020, with Brazil and El Salvador spending over 30%. Social protection expenditures experienced a particularly steep upsurge, increasing from 1.5% of GDP in 2018 to 4.8% in 2020.

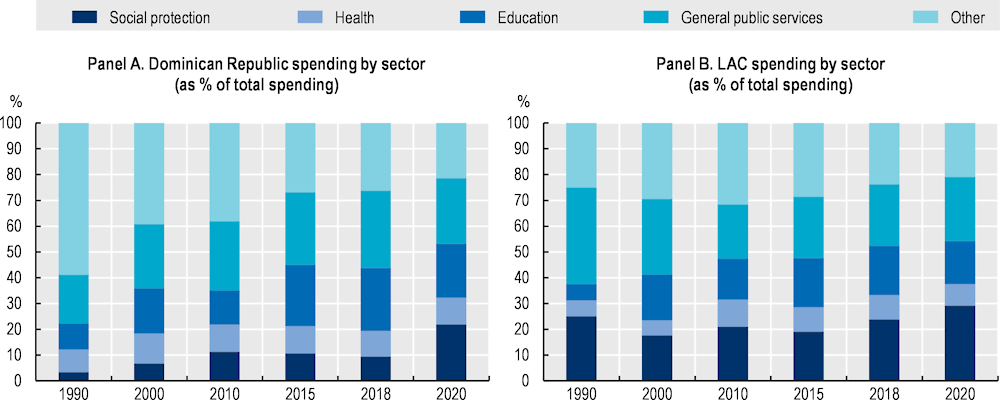

The structure of public spending in the Dominican Republic has notably evolved over the last decades, with public services growing in importance. In 2018, almost one-third (30%) of total public spending was directed towards general public services, representing 4.8% of GDP. Similarly, spending on education rose from 10% of total spending in 1990 to more than 24% in 2018 (3.9% of GDP), mostly owing to the legislative approval of an annual spend of 4% of GDP on education. Social protection expenditures also increased during this time, from 3.3% of total spending in 1990 to 9.4% in 2018 (1.5% of GDP). Spending on public health has grown at a slower pace, however, increasing from 8.9% of total spending in 1990 to 10.5% in 2018 (1.6% of GDP). The main difference between LAC economies is in social protection expenditure; in 2018, this accounted for almost 24% across LAC economies (or 5% of GDP) (ECLAC, 2022[51]) (Figure 4.12). These figures, in general, are below the OECD average, where public spending on health accounted for 9.9% of GDP in 2020 and spending on education made up 4.5% of GDP in 2018 (OECD, 2021[52]; OECD, 2021[53]).

Figure 4.12. Public spending by sector in the Dominican Republic and in LAC (as a percentage of total public spending), 1990‑2020

The COVID‑19 pandemic has further biased expenditures towards current spending, but long-term investments must be protected in order to stimulate sustained growth

The Dominican Republic needs to balance today’s expenditure (current) against tomorrow’s (capital), especially in times of crisis. Pre-COVID‑19 figures show that current expenditure represented 86.2% of total public spending in 2019, with capital expenditure accounting for the remaining 13.8%. The bias against capital expenditure was further accentuated by the crisis, with current expenditure rising from 14.1% of GDP in 2019 to 19.3% of GDP in 2020, representing the vast majority of public spending due to the COVID‑19 pandemic (which accounted for 97% of the increase in public spending in 2020) (Figure 4.13). While the unprecedented impact of the pandemic largely justifies increased public spending in order to protect workers, businesses and households, the recovery will demand a more balanced approach. The multiplier effect of capital spending is often greater than that of public consumption, making the protection of such investments critical during fiscal adjustments in order to reduce costs for long-term output, neutralising the contractionary effects or even stimulating growth in the medium term (Ardanaz et al., 2022[54]). However, budget rigidities make some categories of public spending inflexible, limiting the capacity of policy makers to make any significant adjustment to expenditures.

Figure 4.13. Current and capital expenditures in the Dominican Republic, 1990‑2020

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2022[2]) and (IMF, 2021[55]).

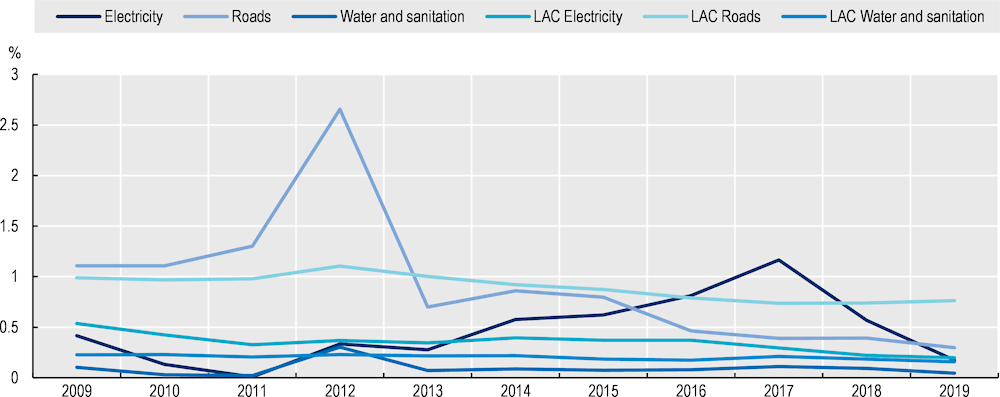

As much as current spending is essential in financing day-to-day basic public services and fostering a faster economic recovery, low levels of capital expenditure can also have strong medium- and long-term effects on economic growth. Addressing and maintaining transport infrastructure, electricity, and sanitation, among other services, has a crucial influence on long-term development. By focusing public spending on short-term programmes, limited funds are left for longer-term infrastructure projects. As of 2019, the Dominican Republic was investing less than 0.5% of GDP in each of the key infrastructure areas of electricity, roads, and water and sanitation. In all three cases, the Dominican Republic spent below the LAC average (Figure 4.14). While Dominican state-owned entities remain dependent on government transfers, over the past few years the government has decreased its overall investment in one of the largest: electricity. While current transfers to this sector have remained steady, the decrease manifests as a reduction in capital expenditures, reflecting a reduction in the overall investment in electricity. The financial performance of the electricity sector is largely determined by oil prices, leading to large losses in 2019 and 2020 and potential risks for government finances in the future. Studies showed that a one-standard-deviation increase in the average price of oil in 2020 would have increased overall costs in the sector by 0.2 percentage points of GDP (World Bank, 2021[56]).

Figure 4.14. Public investment in infrastructure in the Dominican Republic (as a percentage of GDP), 2009‑19

Reduced levels of fiscal space underscore the need to strengthen the efficiency of public spending, increasing its impact on equity and growth

The COVID‑19 crisis has put pressure on public finances in the Dominican Republic. Low levels of public revenues, coupled with the increased pressure on public expenditure to respond to the immediate impact of the crisis, have reduced the room for manoeuvring in financing the recovery. Against this background, the efficiency of public spending emerges as a key policy area, and making the most of the available public resources becomes particularly relevant in order to ensure an inclusive recovery.

Inefficiencies in public spending in the Dominican Republic are relatively large and are estimated to account for up to 3.8% of GDP, although this is below the LAC average of 4.4% of GDP (World Bank, 2019[41]). Inefficiencies are primarily caused by leakages in transfers and procurement waste (World Bank, 2019[41]). In 2018, the Dominican Republic was ranked 131st out of 137 countries in government spending efficiency, and 135th out of 137 countries in the diversion of public funds (WEF, 2018[58]). A government study that examined the quality of public spending between 2008 and 2017 found that the Dominican Republic ranked 9th in the LAC region overall, but ranked among the worst in terms of spending on health (16th in the region out of 17 countries) and education (12th in the region out of 17 countries) (MEPyD, 2020[59]). These results suggest that more efficient and effective spending in health and education could help boost the overall efficiency of public spending in the Dominican Republic and increase the quality of life.

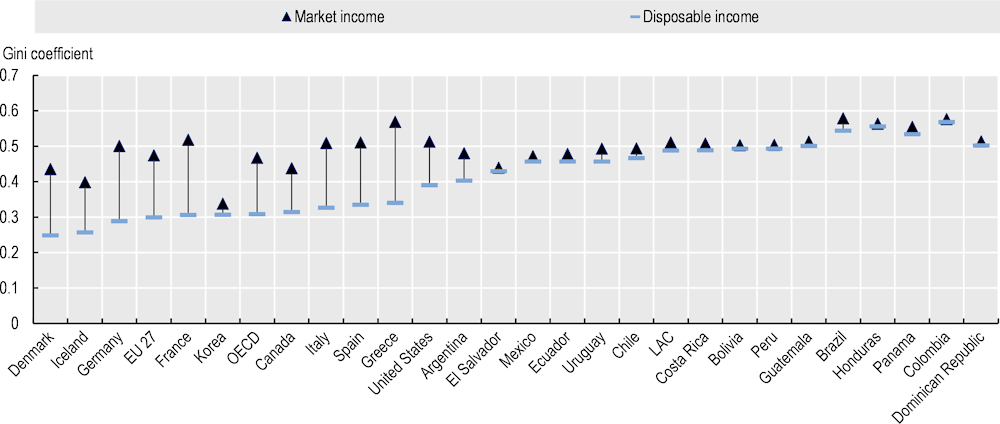

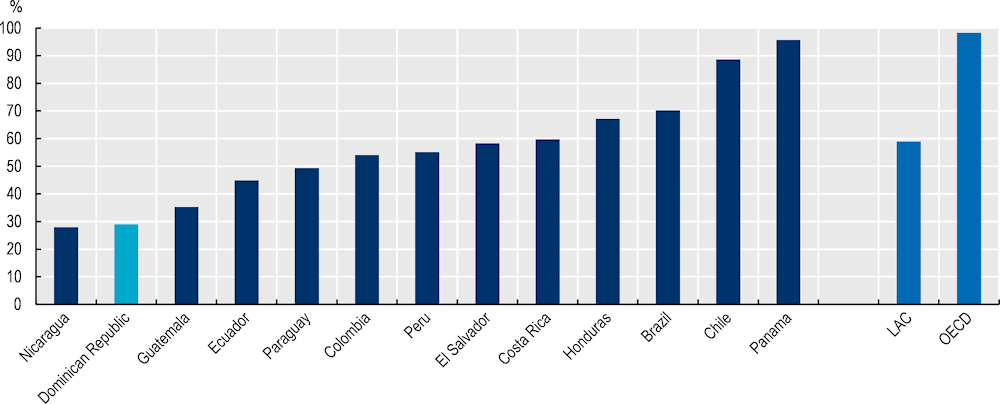

The role of public spending in reducing inequalities in the Dominican Republic is very limited. In fact, taxes and transfers contributed to a reduction of the Gini coefficient by only 1 percentage point, below the average 2 percentage points recorded in LAC economies, and still far from the 16‑percentage-point reduction achieved by OECD member countries on average (Figure 4.15) (Lustig, 2018[60]; OECD et al., 2019[29]).

Figure 4.15. Impact of taxes and transfers on income distribution in the Dominican Republic and selected LAC and OECD member countries

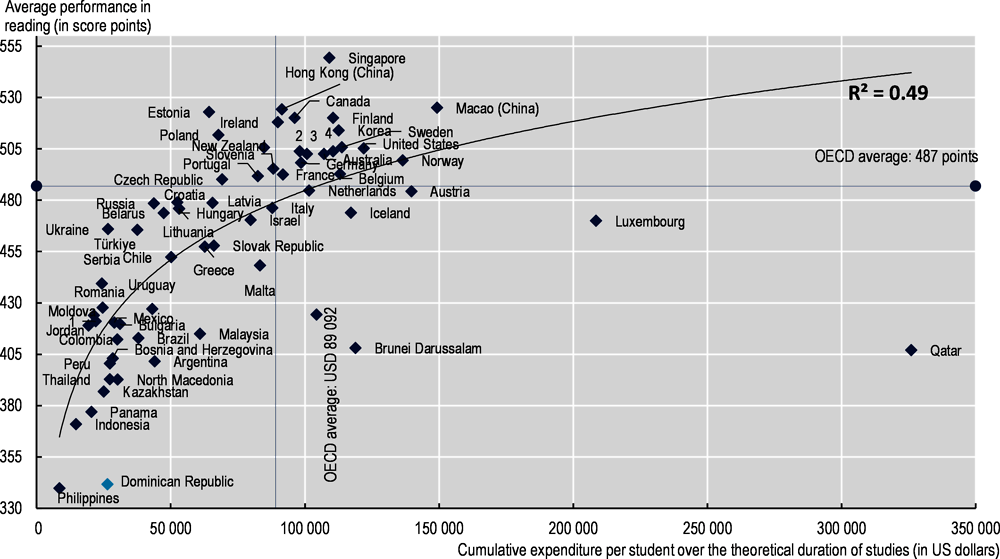

Despite increases in education spending, learning outcomes in the Dominican Republic remain low, and lower than in some countries with similar levels of education expenditures. In 2013, results from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) cognitive test showed that the Dominican Republic had the lowest performance in education in the LAC region. At the time, this was partly attributed to lack of investment in education relative to other countries in the region and also to the poor quality of education spending (OECD, 2013[61]). In the PISA 2018 test, the Dominican Republic scored the lowest among the 79 participating countries in the mathematics and science test, and scored only above the Philippines in the reading test (OECD, 2018[62]). Countries such as Indonesia or Panama managed to achieve better results in PISA tests, while spending a similar amount as the Dominican Republic. Similarly, countries like the Philippines had similar results than the Dominican Republic, but with lower levels of education spending (Figure 4.16). Compared with 2015, results from the 2018 OECD Programme for International Student Assessment showed (PISA) that performance the Dominican Republic in mathematics and sciences was similar, while reading scores were lower (OECD, 2018[62]). These results were achieved in a context of increased levels of public spending in education since 2013, up to 4% of GDP. This performance suggests there are still challenges regarding the efficiency of public spending in education, although investments in education take time to deliver results and some of the impact of increased levels of spending may only become evident in future performance tests.

Figure 4.16. Spending per student aged 6‑15 years and reading performance in PISA (2018)

In the last decade, public spending on health has grown modestly in the Dominican Republic, and key health indicators have shown little improvement. Between 2010 and 2019, life expectancy at birth in the Dominican Republic increased by 2.1 years (from 72.0 years to 74.1 years). The country scores below the LAC average (76.5 years) and far below the regional leaders Costa Rica (80.3 years) and Chile (80.2 years). The Dominican Republic ranks below the LAC average in both numbers of hospital beds per 1 000 inhabitants and average medical and nursing staff per 10 000 inhabitants (below 2 beds and 30 staff). In fact, while public spending in health saw a modest increase from 1.6% to 1.7% of GDP between 2010 and 2017, the share of hospital beds (per 10 000 inhabitants) fell from 1.59 to 1.56 in the same period.

Improving the institutional framework for public spending must be a key priority in order to enhance its impact