This chapter provides an overview of the status of freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, association and the right to privacy as cornerstones of democratic life. It discusses related legal protections and exceptions to the full enjoyment of these rights, followed by a review of implementation trends, challenges and opportunities, including in the context of COVID-19. It examines discrimination as an obstacle to equal participation in public policy making. It reviews legal frameworks and practices protecting human rights defenders. Finally, it examines the types of mechanisms that exist to counter violations of civic freedoms, including oversight and complaints bodies and the role of public communication in promoting civic space.

The Protection and Promotion of Civic Space

2. Facilitating citizen and stakeholder participation through the protection of civic freedoms

Abstract

Key findings

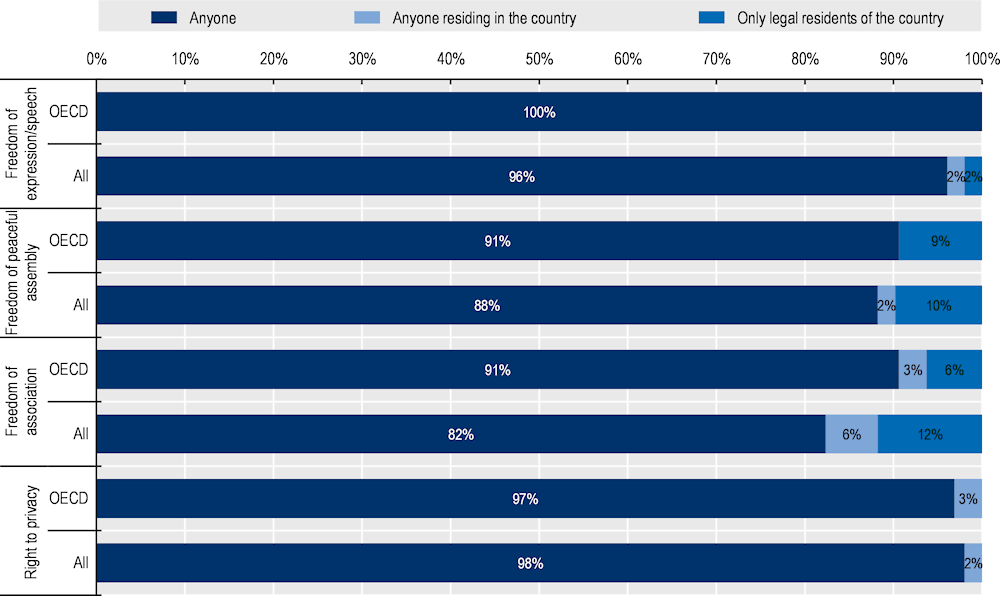

Civic freedoms are generally well protected by legal frameworks in OECD Members and non-Members that participated in the OECD Survey on Open Government. Freedom of expression is a right for anyone present in a country, including irregularly, in 96% of respondents, freedom of peaceful assembly in 88%, freedom of association in 82% and the right to privacy in 98% of respondents.

While most legal exceptions to these rights in OECD Members are in line with international standards, some would benefit from further review to ensure that they do not restrict civic freedoms.

In a context of growing anti-government protests, most surveyed OECD Members permit and facilitate peaceful assembly. But insufficient protection of protestors by law enforcement actors, as well as police violence used against protestors in some contexts, have raised concerns about respecting this right. Court decisions and legal changes have been introduced in some OECD Members to reduce and control the use of force by police during protests.

Despite solid legal frameworks for civic space protection, civic freedoms that underpin democratic life are under pressure in some OECD Members. External data show that the majority (83%) of OECD Members are considered “open” in relation to freedom of expression for example, while 17% of OECD Members are not (Article 19, 2021[1]).

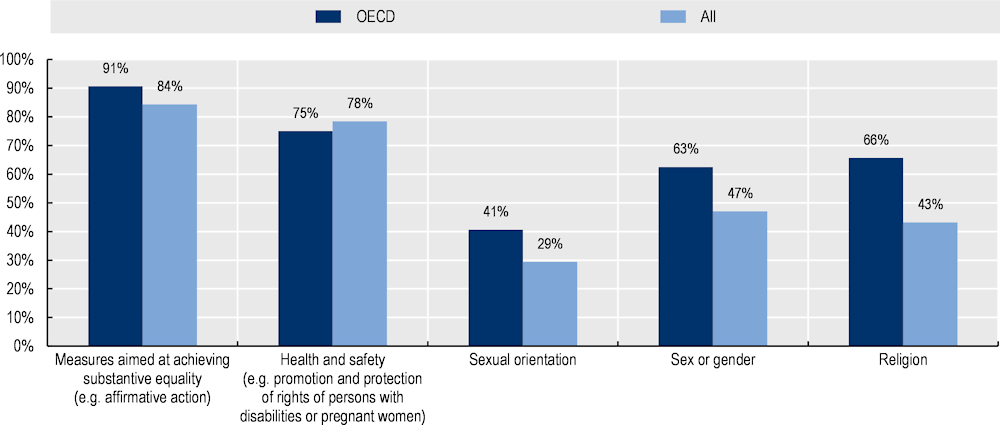

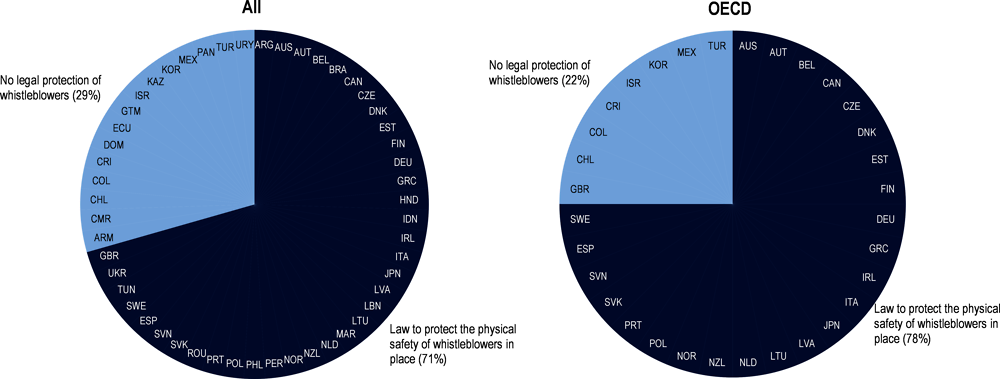

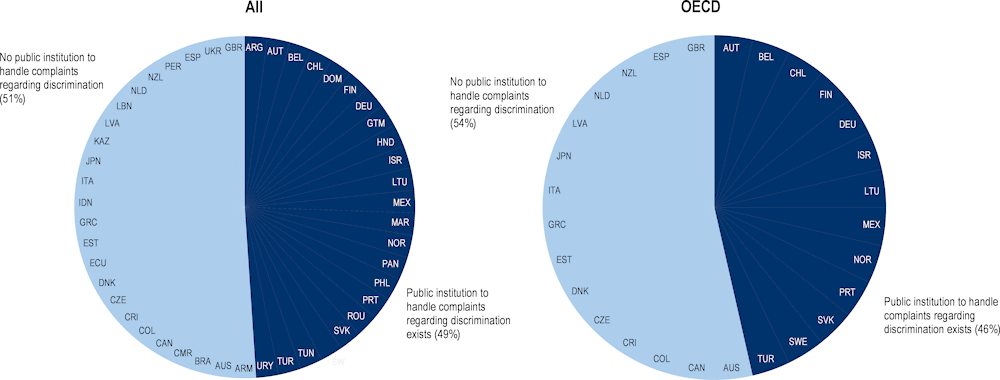

Strong legal frameworks countering discrimination help to enable effective and equal participation and these are supported by affirmative action to support disadvantaged groups, found in 91% of OECD Members and 84% of all respondents. There is an overwhelming trend in OECD Members to prohibit hate speech (97% of respondent OECD Members, 90% of all respondents) as a widely recognised form of discrimination. Almost half of all respondents (46% of OECD Members, 49% of all respondents) have separate institutions that specialise in discrimination cases and in promoting equality.

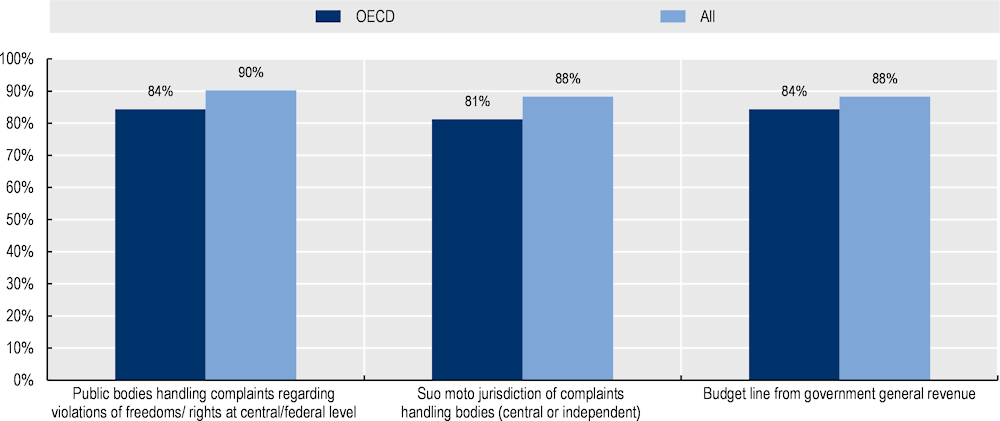

Strong oversight mechanisms are helping to protect civic space. A majority of respondents (84% of OECD Members, 90% of all respondents) have independent public institutions that address human rights complaints. However, basic disaggregation of data (e.g. by age or gender) by these institutions remains rare, hindering the development of prevention and response initiatives targeting affected groups.

Over one-third of OECD Members are leading the way by ending emergency measures that were introduced in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and that affected civic space. As of March 2022, 11 OECD Members were under states of emergency, either due to the pandemic (8 OECD Members) or new emergency measures introduced as a result of the invasion of Ukraine (3 OECD Members).

All respondents would benefit from an ongoing review of the manner in which legal frameworks governing civic freedoms are implemented at the national level, as part of measures to reinforce their democracies. Ongoing monitoring of civic space using disaggregated data to understand emerging challenges and gaps, and cross-government efforts to identify and reverse any negative trends, would also be beneficial.

2.1. The cornerstones of civic space: Legal frameworks governing freedoms of expression, association, peaceful assembly and the right to privacy

Freedoms of expression, association, peaceful assembly and the right to privacy are fundamental civic freedoms that enable effective civic participation.1 These basic rights are an essential precondition for the good governance and development of any democratic society. They are also necessary to ensure the empowerment and well-being of non-governmental actors.

The protection of civic space requires that all people are able to freely express themselves in public, including to critique government decisions, actions, laws and policies, and to hold government actors to account without fear of repercussions. Freedom of peaceful assembly affirms the right of citizens and non‑governmental stakeholders to come together to advance their common interests, including their legitimate right to exercise dissent through peaceful protest and public meetings. Similarly, freedom of association guarantees the right of individuals to form, join and participate in associations, groups, movements, and civil society organisations (CSOs), thereby fulfilling people’s fundamental desire to defend their collective interests. Finally, the state’s duty to protect citizens and stakeholders from abuses of their right to privacy is another prerequisite for a vibrant civic space, as it helps to create the conditions for people to inform, express and organise themselves without undue interference.

The laws, policies and institutions that countries have in place are essential in establishing and protecting civic space. Legal and regulatory frameworks play a critical role in determining the extent to which all members of society, both as individuals and as part of informal or organised groups, are able to freely and effectively exercise their basic civic freedoms, participate in policy and political processes, and contribute to decisions that affect their lives without discrimination or fear.

An analysis of the data from the 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government (Annex A) shows that all 51 respondents to the civic space section of the Survey protect fundamental civic freedoms in national legal frameworks, case law (of higher courts) or by direct application of international human rights instruments, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR). Some of the legally mandated exceptions or conditions to these rights would benefit, however, from further review and revisions to ensure their full compliance with international human rights standards, which are agreed-upon global standards that form the bedrock of democratic societies.

All survey data presented in this chapter pertain to the respondents to the civic space section (32 OECD Members and 19 non-Members) of the 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government (hereafter “the Survey”), except where explicitly stated (e.g. Figures 2.8 and 2.10).

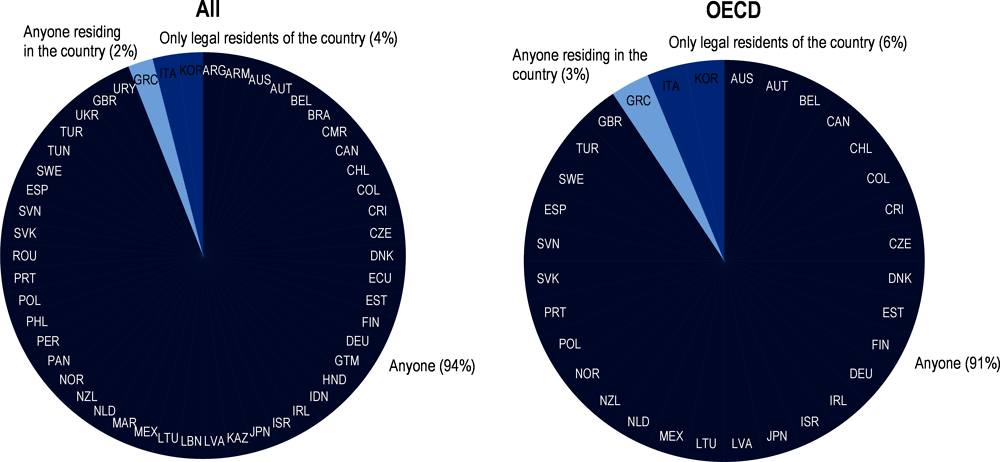

With respect to the question of who may exercise the above-mentioned rights, relevant international human rights instruments do not distinguish between legally recognised citizens and non-citizens.2 However, in some countries, national legal frameworks do distinguish between the two categories, affording fewer rights to those who are not legally recognised.3 For example, Figure 2.1 on legal entitlement to civic freedoms shows that in 96% of respondents, including 100% of OECD Members, relevant legal provisions specify that anyone (meaning anyone physically present in a country, even irregularly) has the right to freedom of expression.

Similarly, 88% of all respondents, including 91% of OECD Members, grant the right to freedom of peaceful assembly to anyone, while Italy, for example, provides this right only to legally recognised citizens, Lithuania provides this right only to legally recognised citizens, European Union citizens, and foreign nationals with permanent residence in the country. Panama grants this right only to residents of the country. In Mexico, the right to freedom of peaceful assembly is only granted to legally recognised citizens where assemblies relate to the political affairs of the country.

In terms of the right to freedom of association, 82% of all respondents, including 91% of OECD Members, grant this right to anyone. While Costa Rica, Lebanon, Panama and Portugal grant this right to persons residing in the country, Cameroon, Italy, Kazakhstan and Romania only grant it to persons residing legally in the country. In Mexico, the right to freedom of association is only granted to legally recognised citizens for associations that focus on political affairs.

The right to privacy is likewise granted to anyone in 98% of all respondents and in 97% of OECD Members. In Costa Rica, the constitution grants the right to private life to anyone but indicates that certain aspects of this right, such as protection of privacy in the home (meaning that nobody may enter without permission, damage or destroy someone’s home) and the inviolability of documents may only apply to persons residing in the country. In Canada, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms only protects individuals against search and seizure, but Canadian courts have applied the right to privacy broadly in all relevant cases, supported by privacy legislation at the federal and provincial levels.

Figure 2.1. Legal entitlement to civic freedoms in all respondents, 2020

Note: “All” refers to 51 respondents (32 OECD Members and 19 non-Members). Data on Canada, Guatemala and Slovenia are based on OECD desk research and were shared with them for validation.

Source: 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government.

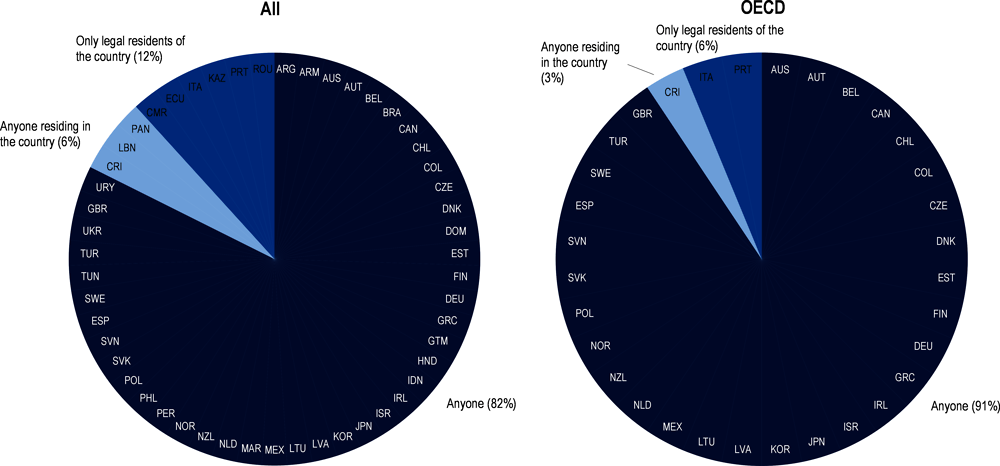

Of all the above rights, entitlement to freedom of association is the most limited with 18% of respondents granting freedom of association only to residents or legal residents (Figure 2.2). Some respondents, including Cameroon, Costa Rica, Kazakhstan and Romania, limit the general exercise of freedom of association. Others, including Italy, Portugal and the Slovak Republic, limit the right to found associations. In the Czech Republic and Finland, legislation prohibits certain public officials from joining associations and only legally recognised citizens or foreigners residing in Finland may join associations “if the purpose of the association is to exercise influence over state affairs” (Finnish Associations Act, 1989[2]).

Figure 2.2. Legal entitlement to freedom of association, 2020

Note: “All” refers to 51 respondents (32 OECD Members and 19 non-Members).

Source: 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government.

Key measures to consider on legal frameworks protecting civic freedoms

Expanding key civic freedoms to non-nationals, including stateless persons, refugees and migrants, would lead to greater compliance with existing international human rights guidance and would ensure that these groups of persons do not suffer discrimination with respect to the exercise of fundamental civic freedoms based on their status.

2.1.1. Freedom of expression

The right to freedom of expression constitutes the foundation of every free and democratic state (UN, 2011[3]; European Court of Human RIghts, 1976[4]; IACHR, 1985[5]) and is one of the main prerequisites for an enabling environment for civil society. This covers the right to hold opinions without interference, as well as the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, orally, in writing or in print.4 Based on international human rights instruments, this right may be restricted where the restrictions are based on law and where it is necessary out of respect for the rights or reputations of others, for the protection of national security or of public order, or for public health or morals.5 The advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence and certain forms of hate speech are likewise prohibited in international human rights instruments.6

Legally mandated exceptions and conditions

Limitations on the right to freedom of expression may entail a wide variety of measures.7 At the same time, restrictions must not jeopardise the right itself, according to guidance from the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Committee (UN, 2011[3]). In particular, freedom of expression is applicable not only to information or ideas that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the state or any sector of the population (European Court of Human RIghts, 1976[4]; IACHR, 2009[6]).

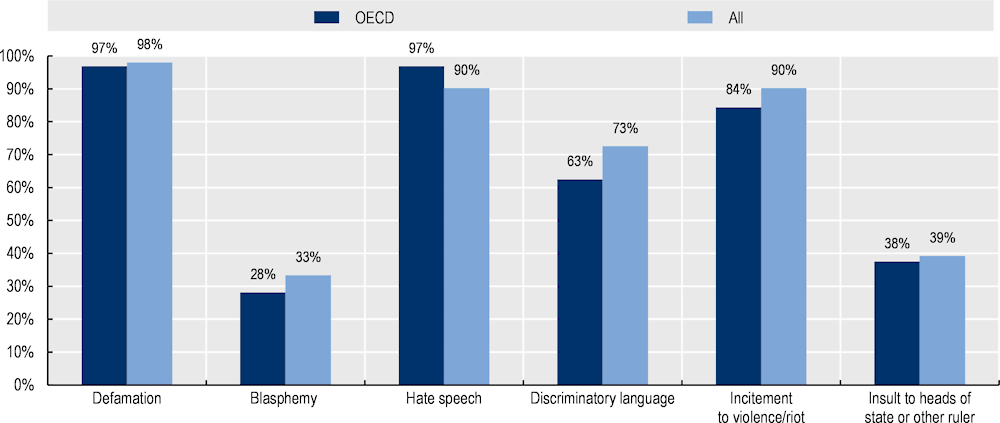

There are several exceptions to freedom of expression that are common across respondents, including defamation, hate speech, incitement to violence and discriminatory language (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3. Legally mandated exceptions to freedom of expression, 2020

Note: “All” refers to 51 respondents (32 OECD Members and 19 non-Members). Data on Armenia, Chile, Guatemala, Honduras, Ireland, Netherland, Peru and Slovenia are based on OECD desk research for at least one category and were shared with them for validation. The data only include laws on national/federal level, countries with laws on state or regional level have been categorised as not having a particular exception. While laws in Belgium, Brazil and Colombia criminalise a lack of respect towards representatives or members of a religion, the countries maintained that such acts were different from blasphemy because these laws criminalise offending people associated with a religion, not the religion or God itself. For this reason, these countries were not included in in the category for blasphemy.

Source: 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government.

Defamation

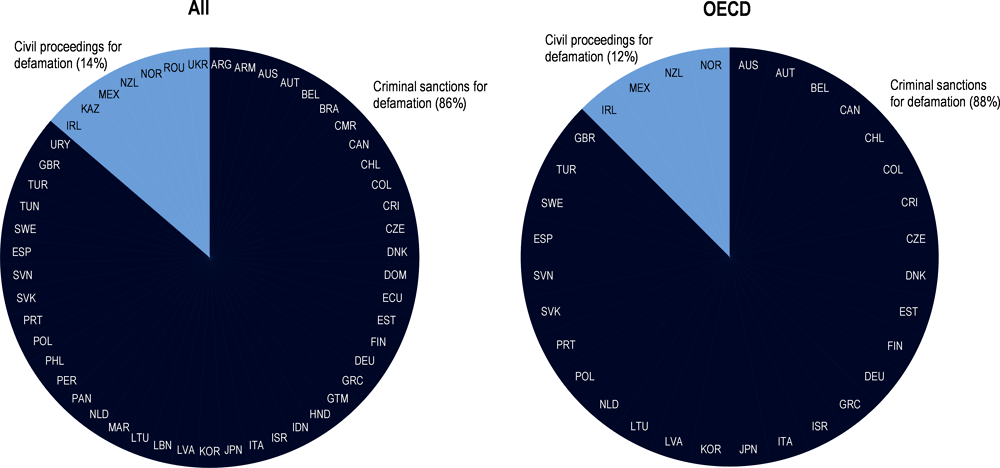

Defamation, defined for the purposes of this report as a false statement, made in any medium (written or orally), which is presented as a fact and which causes injury or damage to the character of the person it is about, is a legally mandated exception to freedom of expression in 98% of all respondents, including 97% of respondent OECD Members (Figure 2.3). While in the majority of respondents a claim must generally be false to constitute defamation, in some respondents, including Japan and Korea, the law does not specify that a statement needs to be false to fulfil the legal requirements of defamation. Figure 2.4 illustrates that while 86% of all respondents have special provisions prohibiting all or certain forms of defamation in their criminal codes, 14% of all respondents, including Mexico, New Zealand and Norway (OECD Members), and Guatemala, Kazakhstan, Romania and Ukraine (non-Members) foresee non-criminal remedies for defamation, such as civil lawsuits leading to damages.

Figure 2.4. Criminal and civil proceedings for defamation, 2020

Note: “All” refers to 51 respondents (32 OECD Members and 19 non-Members). Data on Ireland and Poland are based on OECD desk research and were shared with them for validation.

Source: 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government.

Defamation laws generally aim to protect the reputation of individuals from false or offensive statements and are a balancing exercise between freedom of speech on the one hand and protecting personal reputations on the other. While the protection of a person’s reputation may serve a legitimate interest, criminal sanctions can be viewed as having a greater potential to lead to limitations on civic space, such as censorship and self-censorship, compared with civil remedies, especially when criminal sanctions include prison sentences (UN, 2011[3]; Griffen, 2017[7]). If sanctions are overly broad, there is also a risk of them being abused, including by stifling information and legitimate reporting on matters of public interest. The European Court of Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) have found that imposing excessively punitive sanctions, such as prison sentences in defamation cases, constitutes a disproportionate interference with individuals’ freedom of expression.8 International human rights bodies have thus called on countries to consider decriminalising defamation (CoE, 2007[8]), stressing that criminal law should only be applied in the most serious cases and that imprisonment is not an appropriate penalty (CoE, 2007[8]; UN, 2011[3]).

Thus, while international human rights law permits limitations on speech where necessary out of respect for the rights and reputations of others,9 it is important that defamation laws are formulated carefully to ensure that they comply with the requirements of necessity and proportionality,10 and that they do not serve, in practice, to stifle freedom of expression.11 In its case law, the European Court of Human Rights has often referred to the public interest as a factor to be weighed against restrictions on freedom of expression, when considering whether a restriction is “necessary in a democratic society”. In some cases, it has been ruled that prison sentences may not be imposed as a sanction for defamation in the context of a debate on a matter of legitimate public interest (McGonagle, 2016[9]). Moreover, the court has ruled that a statement that harms or has a negative effect on the reputation of others does not amount to defamation if a sufficiently accurate and reliable factual basis proportionate to the nature and degree of the allegation can be established.12

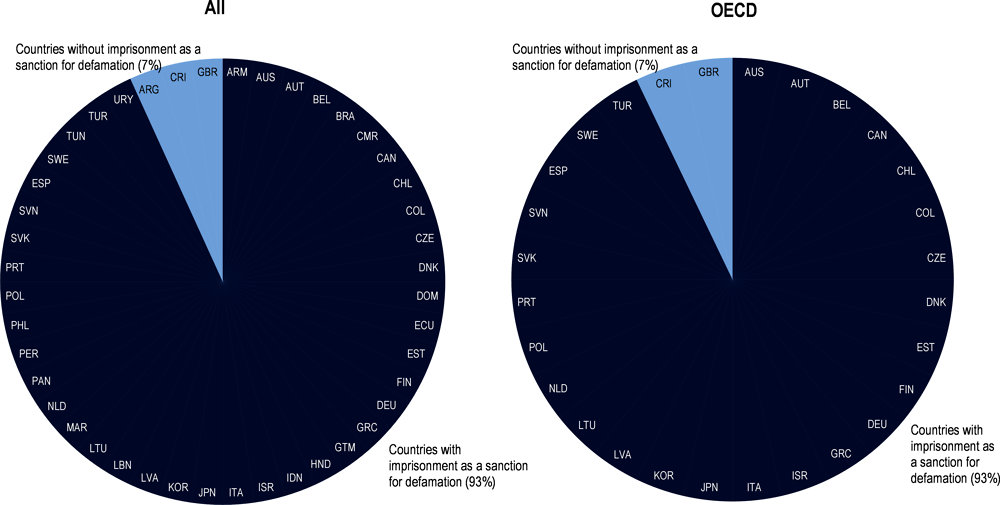

Figure 2.5 illustrates that of the 44 respondents that criminalise defamation, 93% foresee prison sentences as a potential sanction. The percentage (93%) is the same for the 28 OECD Members. Prison sentences range from six months to up to two years in the Czech Republic, Ecuador, Finland, Peru and the Republic of Türkiye (hereafter referred to as Türkiye), up to three years in Japan, Lebanon and Uruguay, up to five years in Canada or even up to six years in Indonesia. In some respondents, committing defamation against heads of state leads to an aggravated punishment.

Figure 2.5. Imprisonment as a potential sanction for defamation, 2020

Note: The graph only displays respondents that have criminal sanctions for defamation, as shown in Figure 2.4. “All” refers to 44 respondents (28 OECD Members and 16 non-Members). Data on Guatemala, Poland and Slovenia are based on OECD desk research and were shared with them for validation.

Source: 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government.

Public interest as a defence in defamation cases has been introduced in defamation laws in some respondents, including in some states in Australia and the United Kingdom and Uruguay. These amendments aim to improve protection for journalists against defamation suits, allowing them to establish that the contents of their publication were in the public interest (Murray, 2021[10]). Public interest was also brought forward as a defence in recent court decisions in a number of OECD Members and non-Members, including Argentina, Brazil and the United Kingdom (Supreme Court of Argentina, 2020[11]; Sao of Brasil Court of Justice, 2016[12]; Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, 2020[13]; United Kingdom High Court of Justice, 2022[14]). In said cases, the respective courts dismissed libel or defamation claims as they found that the contents of the publications of both journalists and private persons and/or the fact that they involved people known for their involvement in public affairs were in the public interest. In the cases before UK courts, the fact that the defendants had believed that relevant publications were in the public interest and that the defendants had behaved fairly and responsibly when publishing the information also played a role.

Moreover, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Lebanon, Lithuania, Morocco and Tunisia have related provisions in their criminal codes or legislation on press, communication and information relating to the dissemination and intentional publication of false facts or news; in the cases of Morocco and Tunisia, this involves situations where there is a risk of disturbing public order or instilling fear.

Figure 2.3 illustrates that 39% of all respondents, comprising 38% of respondent OECD Members, also penalise insulting heads of state. Criminal provisions contain penalties that range from fines to prison sentences of up to six months, one year or even two years (Spain); three years (Belgium and Portugal); or five years (Germany).

There is widespread agreement among international human rights courts and bodies that defamation laws should not offer special protection to the reputation and honour of heads of state or other rulers (CoE, 2007[8]; UN, 2011[3]; IACHR, 2000[15]). This is on the basis that, in any functioning democracy, it is important that the actions of public officials can be closely scrutinised by both journalists and the public and that the limits of acceptable criticism of public officials and politicians should be wider than for private individuals.13 According to international guidance, the existence of such insults is, by themselves, not sufficient to justify the imposition of penalties; all public figures, including those exercising the highest political authority, are legitimately subject to criticism and political opposition. In practice, these laws are hardly implemented in OECD Members. For example, even though it remains a crime to intentionally insult monarchs or heads of state in OECD Members such as Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal or Spain, there have been no prosecutions in the past decades (Venice Commission, 2016[16]).

Hate speech, discriminatory language, and incitement to violence

Figure 2.3 illustrates that 90% of all respondents and 97% of respondent OECD Members prohibit hate speech, defined for the purposes of this report as any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are and aims to incite discrimination or violence towards that person or group, e.g. based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factors (Box 2.1 on hate speech legislation in OECD Members and Section 4.4.2 in Chapter 4). Figure 2.3 also shows that 73% of all respondents (63% of respondent OECD Members) ban discriminatory language. Further, 90% of all respondents and 84% of respondent OECD Members criminalise incitement to violence.14 In some respondents, legislation also prohibits propaganda or agitation that threatens the constitutional system (e.g. Australia, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, Türkiye) or the dissemination of propaganda material from unconstitutional organisations (Germany).

Addressing hate speech remains a considerable challenge, given the need to balance a democratic society’s requirement to allow open debate, freedom of expression and individual autonomy and development with the equally compelling obligation to prevent attacks on vulnerable communities and ensure equal and non-discriminatory participation of all individuals in public life (UN, 2019[17]).

A number of OECD Members have increased their efforts to combat hate speech in recent years, especially online (Section 4.4.2 in Chapter 4). At the same time, non-governmental sources have stressed that these types of laws can also constitute potential threats to civic space when definitions of hate speech are overly broad (Australian Hate Crime Network, 2020[18]; Global Network Initiative, 2021[19]; Article 19, 2020[20]).

The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) as well as the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) have emphasised that racist expression should only be criminalised in serious cases and that less serious cases should be addressed by means other than criminal law.15 Thus, according to the CERD, speech that insults, ridicules or slanders persons, or that justifies hatred, contempt or discrimination, may only be prohibited where it “clearly amounts to incitement to hatred or discrimination”16 (CERD, 2013[21]; ECRI, 2015[22]; ECtHR, 2020[23]; UN, 2013[24]; 2019[17]).

Box 2.1. Hate speech legislation in OECD Members

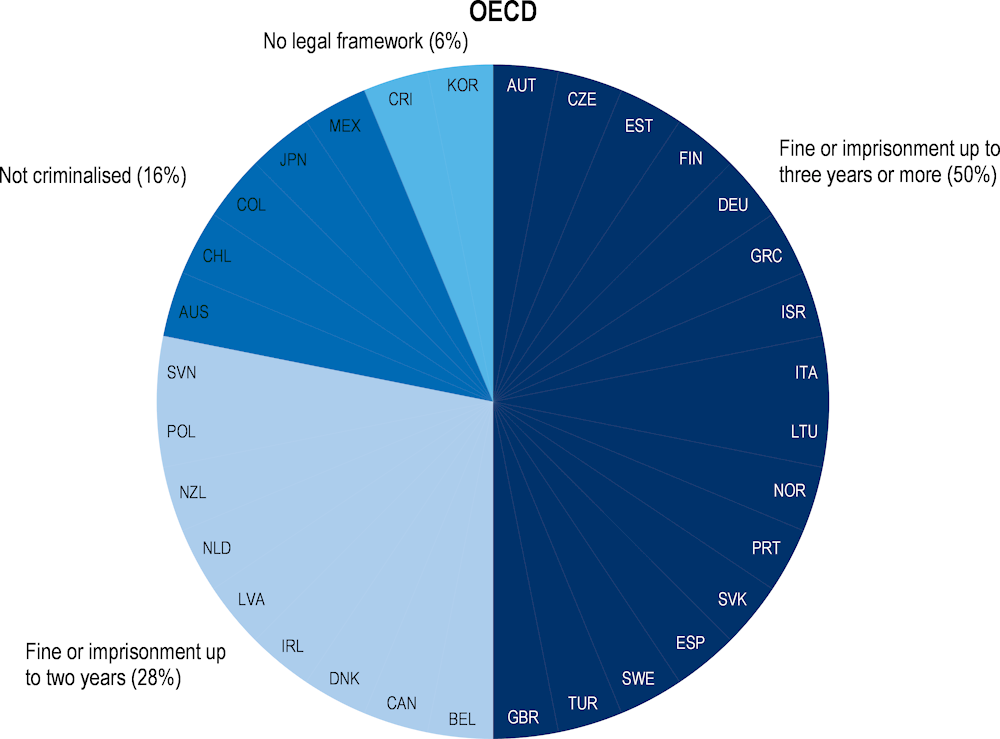

Figure 2.6 illustrates that all OECD respondents, except Costa Rica and Korea, have a legal framework in place governing hate speech or similar actions, either explicitly or implicitly, both on and off line. The respective legal provisions are usually set out in criminal or anti-discrimination legislation. While in most cases, legislation does not mention online hate speech explicitly and rather speaks about general dissemination, which could also be off line, some OECD Members, such as Australia, Chile, Germany, Italy and New Zealand, have separate laws or regulations in place that explicitly address online hate speech.

Figure 2.6. Sanctions for hate speech in OECD Members, 2020

Note: The graph consists of 32 OECD Members. Data on Ireland and the United Kingdom are based on OECD desk research and were shared with them for validation. While Costa Rica has referred to Art. 13 of the American Convention on Human Rights as the legal basis for hate speech as an exception to freedom of expression, it has no national legislation on hate speech. Therefore, Costa Rica is categorised as a country with hate speech as an exception to freedom of expression in Figure 2.3 but with no relevant national legislation in Figure 2.6.

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on the legal frameworks on hate speech provided by respondents to the 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government.

Out of the 94% of respondent OECD Members that have national legislation on hate speech, 78% criminalise it, with varying sanctions. Figure 2.6 illustrates that in 28% of respondent OECD Members that have hate speech legislation in place, the punishment for such statements includes fines and imprisonment ranging from 1 month to up to 1, 1.5 or 2 years. In 50% of respondent OECD Members, the punishment is more severe and amounts to a minimum of 3, 4 or 6 months, or 1 or 4 years, and a maximum of 3, 4, 5 or even 8 years of imprisonment, including in cases where incitement is carried out via the media or otherwise published, where an organised group commits the act, or where incitement leads to or involves violence, clearly endangers public order and safety or is otherwise of a serious nature. In Greece, in cases of imprisonment for at least a year, an additional legal consequence is the deprivation of a person’s political rights from one to five years. Australia, Chile, Colombia, Japan and Mexico ban but do not criminalise hate speech. In Japan, the Act on the Promotion of Efforts to Eliminate Unfair Discriminatory Speech and Behaviour against Persons Originating from Countries other than Japan focuses on awareness-raising, government measures and advice, but does not foresee any punishment for unfair discriminatory speech. In Türkiye, the requisite provision concerns discriminatory treatment based on hatred towards certain groups but lacks the element of inciting hatred or violence towards these groups.

There is thus an overwhelming trend in OECD Members to criminalise hate speech and provide prison sentences for serious cases involving incitement to hatred or violence, with aggravated prison sentences for cases of public incitement or serious violence against certain groups. This would appear to be largely consistent with the international standards set out above.

As a reaction to widespread public concerns, a number of OECD Members, including France, Germany, Israel and the United Kingdom have also adopted new legislation that increases pressure on social media companies to remove hate speech and other harmful content from their platforms within a particular period.1 Demand for better moderation of harmful speech by both social media platforms and governments has increased just as new national regulations on content removal have been criticised by CSOs in some countries for being too broad and sometimes based on opaque and ambiguous criteria, posing a risk to freedom of expression.2

In countries where regulatory mandates are lacking, such as the United States, technology companies have developed their own strategies for identifying harmful material. In both scenarios, governments and companies have faced criticism for measures either being too vague or remaining insufficient (UN, 2021[25]; OECD, 2019[26]), as well as for a lack of transparency and consistency when it comes to enforcing rules on content moderation.3The OECD report An Introduction to Online Platforms and Their Role in the Digital Transformation notes that platforms responsible for carrying out filtering need sufficient clarity and guidance from governments in order to be able to comply with filtering requirements without obstructing freedom of expression (OECD, 2019[26]).

Civil society actors have also raised concerns about leaving human rights compliance in the hands of private sector companies, which are not viewed by them as being sufficiently accountable to take on the role of online regulators. Moreover, there are concerns about the public interest contrasting with the self-interest of the technology companies whose business models create incentives for gaining audiences’ attention and which may promote sensationalist, scandalous and false information as a result (Smith, 2019[27]; Lanza, 2019[28]; Article 19, 2020[20]; Freedom House, 2020[29]). Chapter 4 (Section 4.4.2 on implementation challenges and opportunities for freedom of expression online) provides a detailed overview of government-led measures in OECD Members and beyond to combat online hate speech and/or harassment in OECD Members, including those related to content moderation, co-regulation with the private sector and self-regulation.

1. Even though France was not part of the Survey on Open Government, and the United States did not participate in the civic space section of the Survey, they are mentioned here as examples of countries that have adopted measures to counter online hate speech.

2. The German NetzDG Law, for example, has sparked controversies about the potential negative impacts of excessive regulations on online freedom of expression as social media platforms removed legitimate content under its provisions. Critics have expressed concerns that its provisions are too broad, which may incentivise social media platforms to over-regulate in order to avoid sanctions and thereby remove legal speech (UN, 2019[17]; Freedom House, 2020[29]).

3. In the United States, observers have claimed that content moderation policies to counter hate speech and algorithmic bias lead to the removal of comparatively mild content posted by people of colour, while other speech that appears more inflammatory remains (Angwin, 2017[30]; Freedom House, 2020[29]; Murphy, 2020[31]). In Mexico, a bill on hate speech in June 2020 was criticised by a coalition of CSOs for its vague language. CSOs argued in a position paper that only certain types of speech should be addressed through criminal law due to the potential harm to freedom of expression (Red en Defensa de los Derechos Digitales, 2020[32]).

Source: (OECD, 2020[33]); Article 19 (2020[20]), The Global Expression Report 2019/2020, https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/GxR2019-20report.pdf; United Nations (2021[25]), Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Minority Issues, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Minorities/SRMinorities/Pages/annual.aspx; Smith, R.E. (2019[27]), Rage Inside the Machine: The Prejudice of Algorithms and How to Stop the Internet Making Bigots of Us All, https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/rage-inside-the-machine-9781472963888/; Freedom House (2020[29]), Freedom on the Net 2020: The Pandemic’s Digital Shadow, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2020/pandemics-digital-shadow; United Nations (2020[34]), Observations on Revised Draft (November 2019) of General Comment 37 on Article 21 of the ICCPR; Lanza, E. (2019[28]), Informe Anual de la Relatoría Especial para la libertad de Expresión, http://www.oas.org/es/cidh/expresion/informes/ESPIA2019.pdf.

Blasphemy

Figure 2.3 shows that 33% of all respondents, comprising 28% of respondent OECD Members, have special provisions prohibiting blasphemy, defined for the purposes of this report as an action that shows a lack of respect for a God or religion. Some criminal provisions prohibiting blasphemy or religious defamation17 can give rise to punishment for criticising or offending certain religions or their leaders by imposing either fines or prison sentences of usually up to six months; in some respondents, the prison sentences may run up to one or even three years.

Where expressions go beyond the limits of a critical denial of other people’s religious beliefs and are likely to incite religious intolerance, the European Court of Human Rights has confirmed that states may legitimately consider them to be incompatible with respect for freedom of thought, conscience and religion, and take proportionate restrictive measures.18 The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) has also stated that as far as necessary in a democratic society, national law should only penalise expressions about religious matters that intentionally and severely disturb public order and call for public violence.19

At least two respondents have recently amended their legislation to repeal blasphemy or similar acts. In Ireland, the abolition of the blasphemy act followed a referendum held in 2018, while in Denmark, a provision on blasphemy – that included potential prison sentences – was abolished in 2017, following a prosecution brought in 2017.

Key measures to consider on legal frameworks governing freedom of expression

- Amending defamation laws to ensure that remedies for those whose reputation has been unfairly undermined take the form of a civil suit, not a criminal one and abolishing prison sentences as a potential sanction.

- Reforming relevant legislation so that insults to heads of state are no longer considered an offence, and above all to remove prison sentences as a possible sanction.

- Ensuring that criminal legislation on hate speech is not overly broad and contains the elements of incitement to hatred, violence or discrimination.

Implementation challenges and opportunities, as identified by CSOs and other stakeholders

At the global level, protection for freedom of expression is declining and this was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to CSOs. CIVICUS has documented that some governments took the pandemic as an opportunity to silence critical voices, enforce new regulations regarding censorship and detain activists, for example (CIVIVUS, 2021[35]). According to Article 19’s Global Expression Report (2021[1]), many governments placed disproportionate restrictions on the media and repressed information during the pandemic. Two out of every 3 people, amounting to a total of 4.9 billion people globally, “are living in countries that are highly restricted or experiencing a free expression crisis”, according to Article 19 (2021[1]).

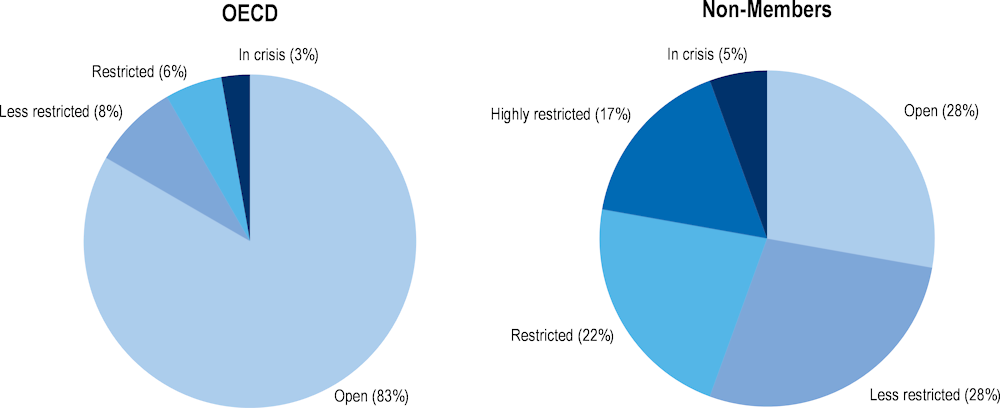

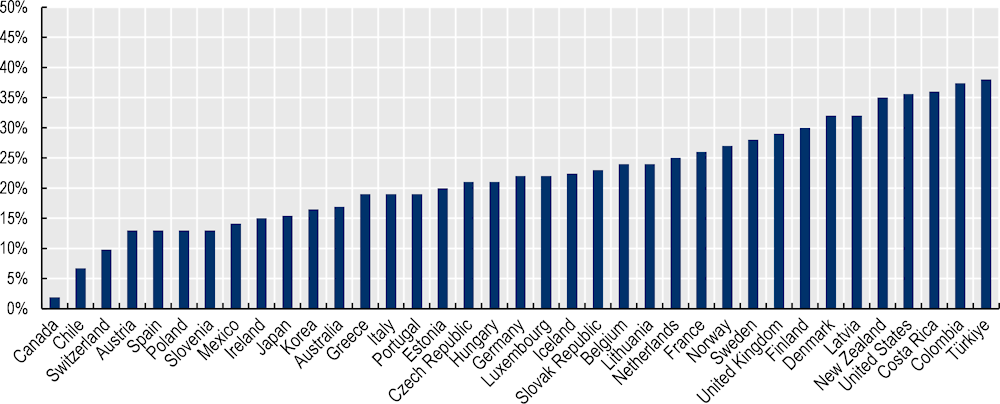

Figure 2.7 provides an overview of freedom of expression rankings from Article 19 for 36 OECD Members and 18 non-Members that responded to the 2020 Survey on Open Government.20 The data, which are based on factual information as well as expert assessment, demonstrate that the majority (83%) of OECD Members rank as “open”, meaning it is possible for citizens to access information and distribute it freely, share their views both on and off line, and to protest in order to hold their governments to account. However, 3 OECD Members (8%) are ranked “less restricted”, 2 OECD Members (6%) as “restricted” and 1 OECD Member (3%) is considered to be “in crisis”. For non-Members, 28% rank as “open”, while several countries are “less restricted” (28%), “restricted” (22%), “highly restricted” (17%) and 1 is considered to be “in crisis” (6%). Identified challenges range from the use of invasive tracking and surveillance tools against human rights defenders and journalists, as well as parliamentary and court shutdowns during the pandemic, to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI)-free declarations at the local government level affecting many citizens’ ability to participate in public life, the erosion of the independence of government branches and threats against human rights defenders (Article 19, 2021[1]).

Figure 2.7. Article 19 freedom of expression ranking, 2020

Note: “OECD” refers to 36 OECD Members, “non-Members” refers to 18 non-Members that responded to the OECD Survey on Open Government. No data were available for Luxembourg, Mexico (as Article 19 Mexico has its own methodology for tracking and measuring the state of freedom of expression in the country) and Panama. For more information on each country’s ranking, consult the Article 19 Global Expression Report 2021 (2021[1]).

Source: Article 19 (2021[1]), The Global Expression Report 2021: The state of freedom of expression around the world, https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/A19-GxR-2021-FINAL.pdf.

Non-Members face greater challenges related to protecting freedom of expression, with several countries falling into the “restricted”, “highly restricted” and “in crisis” categories. However, among non-Members, no one region is a particular outlier. Good practices can also be found in several countries, such as Argentina, Armenia, the Dominican Republic, Peru and Uruguay, all of which rank as “open” (Article 19, 2021[1]). For example, Argentina recognised the right to protest as a constitutional right in 2020 and many countries, including Armenia and Tunisia, saw “great advances” driven by protest movements, according to Article 19 (2021[1]).

As regards the implementation of defamation laws in practice, press freedom organisations and monitoring bodies have indicated that criminal defamation cases continue to be brought against journalists and human rights defenders in retaliation for unwanted investigations or commentary (Freedom House, 2021[36]; OSCE, 2017[37]). Research suggests that occasional convictions continue to take place in countries considered to be strong defenders of media freedom, including several OECD Members, such as Greece (OSCE, 2017[37]) and Italy (Borghi, R., 2019[38]). In some countries, an increasing trend was noted in recent years of convictions for defamation and related prison sentences (OSCE, 2017[37]). While the application of defamation laws protecting heads of state appears to be a dead letter in practice in most countries, they are still being applied in some, including Germany, Poland and Türkiye (POLITICO, 2021[39]; OSCE, 2017[37]).

In recent years, human rights groups and CSOs have also raised concerns about new anti-terrorism and security legislation having potentially negative effects on freedom of speech, including in the Philippines (McCarthy, 2020[40]; Amnesty International, 2020[41]) and Türkiye (ICNL, 2022[42]), given the broad definitions of incitement to terrorism in national laws (Section 4.4.2 in Chapter 4). When legal frameworks governing counter-terrorism are not clearly defined or are overly broad, this can have the effect of silencing speech and legitimate reporting by journalists. The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights has stressed that anti-terror legislation should “only apply to content or activities which necessarily and directly imply the use or threat of violence with the intention to spread fear and provoke terror” (Mijatović, 2018[43]). Moreover, new legislation obliging online content service providers to delete unlawful or criminal content within a short time span, such as in Germany, has raised concerns regarding freedom of expression among CSOs, in the absence of sufficient safeguards to prevent the deletion of lawful content (Article 19, 2020[20]) (Section 4.4.2 in Chapter 4).

Key measures to consider on implementation challenges relating to freedom of expression

Protecting and fostering the implementation of freedom of expression laws as part of a vibrant “public interest information ecosystem”. One way to achieve this is to ensure there is an independent and adequately resourced mechanism in place to monitor, identify and address de facto restrictions on freedom of expression involving affected stakeholders such as specialist CSOs and journalists.

For key measures to consider on legal frameworks to counter hate speech and mis- and disinformation as threats to online civic space, see Section 4.4.2 in Chapter 4.

2.1.2. Freedom of peaceful assembly

Similar to freedom of expression, freedom of peaceful assembly is recognised as a fundamental right in democratic societies21 that is essential for the public expression of people’s views and opinions.22 In line with international guidance, people should, in principle, be able to exercise the right to peaceful assembly in all public spaces, and participants in such events should have sufficient opportunity to manifest their views effectively, within sight and sound of their target audience, or at whatever site is otherwise important to their purpose (UN, 2020[44]; OSCE/ODIHR/Venice Commission, 2020[45]). Moreover, the use of public space for assemblies is as legitimate as other uses of public space and assemblies may not be prohibited or dissolved due to traffic obstructions or inconvenience.International bodies have further stressed that restrictions on the right to freedom of peaceful assemblies should generally not be based on the contents of the messages that they seek to communicate.23

Legally mandated exceptions and conditions

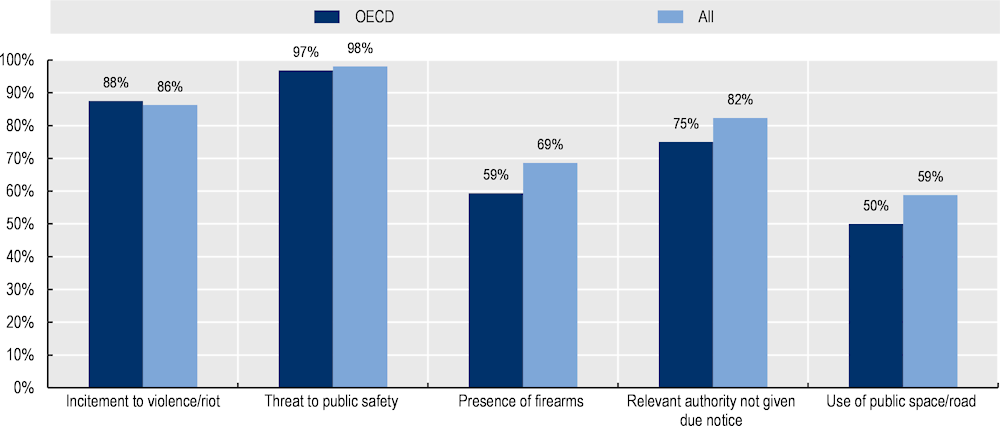

Figure 2.8 shows that the right to freedom of peaceful assembly is limited by a variety of exceptions, exemptions or conditions in OECD Members and non-Members.

Figure 2.8. Legally mandated exceptions to freedom of peaceful assembly, 2020

Note: “All” refers to 51 respondents (32 OECD Members and 19 non-Members). Data on Austria, Colombia, Denmark, Guatemala, Honduras, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia and Sweden are based on OECD desk research for at least one category and were shared with them for validation.

Source: 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government.

Incitement to violence and threat to public safety

Figure 2.8 shows that 86% of all respondents, comprising 88% of respondent OECD Members, prohibit incitement to violence, both generally and specifically in the context of assemblies. Further, 98% of all respondents and 97% of respondent OECD Members allow assemblies to be limited or banned if they constitute threats to public safety. As shown in Figure 2.8, 69% of all respondents and 59% of respondent OECD Members have laws that specify that firearms and other weapons may not be carried at public assemblies.24

As per international guidance, restrictions on freedom of peaceful assembly in cases involving incitement to violence or threats to public safety are considered legitimate. Freedom of peaceful assembly excludes gatherings where organisers or participants have violent intentions or otherwise reject the foundations of a democratic society, for example.25 The European Court of Human Rights has also specified in its case law that the term “peaceful” includes conduct that may annoy or give offence to other individuals opposed to the ideas or claims that it seeks to promote, or that temporarily hinders, impedes or obstructs activities of third parties.26 In practice, this means that assemblies are still regarded as peaceful even if their participants call for unpopular political or social ideas, including, for example, autonomy or secession from a state (ECtHR, 2001[46]), limitations on abortion (ECtHR, 1988[47]) or if they temporarily block traffic (OSCE/ODIHR/Venice Commission, 2020[45]).

There is no indication that any relevant legislation in respondents places the responsibility of guaranteeing public safety during assemblies on the organisers. While laws in a number of respondents, including Cameroon, Latvia, Morocco, the Philippines and Tunisia, stipulate that the organisers of assemblies are responsible for maintaining order and preventing any infringement of the law, the extent to which organisers are held liable for incidents occurring during assemblies depends on how these laws are implemented in practice. According to UN guidance, states are expected to provide adequately resourced police arrangements necessary for maintaining public order and safety and should not oblige assembly organisers to provide such services (Kiai and Heyns, 2016[48]).

Notification of assemblies and use of public spaces

Figure 2.8 illustrates that in 82% of all respondents and 75% of respondent OECD Members assembly organisers are obliged to notify the relevant authority in advance and, in some respondents, such as Cameroon, Ecuador, Italy and Korea, a failure of notification can lead to imprisonment. In Israel, it is a criminal offence to hold a meeting or a march without the required permit or to breach the conditions stated in the relevant license provided by authorities for an assembly.

In 59% of all respondents and 50% of respondent OECD Members, the use of public spaces to hold peaceful assemblies is restricted. In addition to provisions allowing changes to the place or time of an assembly by authorities where this is necessary to protect other interests, laws in certain respondents, such as Armenia, Romania and Tunisia, indicate public spaces where it is not permissible to hold assemblies, or where assemblies are only permissible in certain circumstances, e.g. close to borders, military installations or schools or in areas close to constitutional organs. Germany has a law outlining restricted areas around federal constitutional organs, stating that assemblies in these areas are only permissible insofar as they do not unduly restrict the work of these organs and access to them. In Greece, outdoor assemblies may be prohibited in a specific area, in case of threats involving a serious disturbance of social and economic life. On the other hand, Kazakhstan requires assemblies to be held in certain specialised locations. Other respondents, such as Indonesia and Lebanon, only allow protests to take place at certain times of the day (ICNL, 2021[49]; Right of Peaceful Assembly, 2021[50]).

International human rights bodies have highlighted that advance notification requirements for holding assemblies, while permissible to ensure their smooth conduct,27 may not be used to stifle the freedom of peaceful assemblies and should never turn into de facto authorisation regimes.28 According to international guidance, the failure to notify authorities of an assembly beforehand does not by itself justify an interference with the assembly; especially where assemblies remain peaceful, public authorities are required to exhibit a degree of tolerance.29 Moreover, blanket restrictions on holding assemblies in certain locations should be avoided as they risk being disproportionate30 and can only be justified if there is a real danger of disorder which other less stringent measures cannot prevent.31 International human rights bodies also recommend avoiding designating perimeters around certain official buildings as areas where assemblies may not occur.32 Rather, authorities are advised to justify any time, place and manner restrictions on assemblies on a case-by-case basis.33

In a significant development in Brazil, in 2021, the Supreme Federal Court ruled that meetings and demonstrations are permitted in public places regardless of prior official communication to authorities and that the state is obliged to compensate media professionals injured by police officers during news coverage of demonstrations involving clashes between the police and demonstrators (Supreme Federal Court, 2021[51]).

In Canada, certain court decisions in 2019 and 2020 came to the conclusion that measures regulating public space and health and safety matters did not infringe on the right to freedom of peaceful assembly. In other cases, courts concluded that based on the applicable provincial legislation, local police did not have the legal authority to establish a police perimeter, including baggage searches, around a public park where demonstrators were gathering, and found that the legal requirement to provide advance notice to the police of the time, location and/or route of a demonstration, with deviations leading to liability punishable by fines were not a justifiable limit to freedom of peaceful assembly (Court of Appeal Ontario, 2020[52]; Court of Appeal Québec, 2019[53]). In the United Kingdom, a Policing Bill introduced in 2022 allows the police to impose a start and finish time on public protests and set noise limits, which was criticised by CSOs for overly restricting people’s ability to protest (Weakly, 2022[54]).

Key measures to consider on legal frameworks governing peaceful assembly

- Allowing peaceful assemblies to be conducted in all public spaces, so that participants have sufficient opportunity to manifest their views effectively, within sight and sound of their target audience, avoiding blanket restrictions and justifying any restrictions, for example for security reasons, on a case-by-case basis.

- Ensuring that legal frameworks do not provide for imprisonment as a potential sanction for a failure of notification of assemblies.

Implementation challenges and opportunities, as identified by CSOs and other stakeholders

In recent years, across the world, citizens have been utilising their civic freedoms to engage in mass protests, which have brought issues related to social and economic inequality, corruption, police accountability, violence and calls for greater civic rights to the centre of political debates in many countries. Indeed since 2017, three-quarters (74%) of OECD Members have experienced significant anti-government protests, some of which have occurred on multiple occasions, according to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (2021[55]).

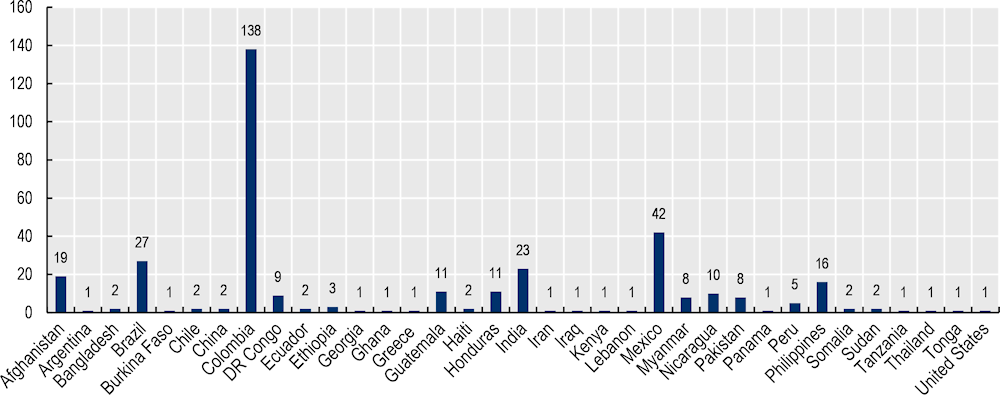

Across all OECD Members and the non-Members that responded to the Survey, the Carnegie Endowment has documented more than 120 significant anti-government protests in its Global Protest Tracker, of which 14 or 37% involved 100 000 or more people taking part (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2021[55]). Several respondents, namely Chile, Lebanon, Korea and the United Kingdom, have experienced protests involving 1 million people or more. Of these protests, 27 in OECD Members resulted in “significant outcomes”, such as a referendum, resignations, dismissals or impeachments of senior government officials or heads of state, a collapse of government or withdrawals of proposed legislation (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2021[55]). More than 25 of these significant anti-government protests were COVID‑19 related, meaning that people were voicing opposition to restrictions, lockdowns and vaccination passes. In addition to these outcomes, new forms of civic activism have emerged in the past years, with much more fluid and informal organisational settings and a focus on the new opportunities brought by technology and digital activism.

While in most OECD Members, citizens can hold non-violent demonstrations without fear of reprisal, organisations monitoring civic space have observed disproportionate limitations on the right to protest in past years in some countries. These have included situations where assemblies were not adequately policed and where participants were not protected (FRA, 2018[56]), as well as the excessive use of police force against protestors in some contexts, and a failure to protect participants and journalists covering the protests, according to multiple sources (Frontline Defenders, 2021[57]; 2020[58]; CIVICUS, 2020[59]; Narsee, 2021[60]; U.S. DoS, 2021[61]; 2020[62]; ENNHRI, 2021[63]). There have also been cases of fatalities and injuries following engagement by state forces in the context of demonstrations (ACLED, 2021[64]; Article 19, 2020[20]). Throughout 2019 and 2020, CSOs and monitoring organisations reported that protestors were met with detentions and the use of excessive force in at least 11 OECD respondents (Freedom House, 2021[36]; U.S. DoS, 2020[62]; 2021[61]; ENNHRI, 2021[65]; Article 19, 2020[20]; IACHR, 2018[66]). In Europe, detentions of protestors were documented in at least 16 EU Member states in 2020, while the use of excessive force was recorded in at least 10 EU Member states (Narsee, 2021[60]).

As a reaction to increased police violence during protests, recent court decisions and legal changes have been introduced in some Latin American countries to reduce and control the use of police force during protests, including in Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico (Corte Suprema de Justicia, 2020[67]; IACHR, 2021[68]; Ministerio del Interior, 2021[69]). In Mexico, a law on the use of police force adopted in 2019 provides for adequate police training and the protection of protestors and permits the use of different levels of force during violent demonstrations. The Mexican National Human Rights Commission filed an Action of Unconstitutionality related to the law, arguing that it did not respect the principles of legality, necessity and proportionality and failed to provide the definition of methods, techniques and tactics of the use of force (Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos, 2019[70]). Civil society groups have also criticised it for failing to specify the circumstances and manner in which certain weapons may be used during assemblies (Amnesty International, 2019[71]; 2019[72]).

A decree passed in Colombia in 2021 permitted the military to police assemblies; this decree was suspended provisionally in July but CSOs have raised concerns that it is a temporary suspension and that potential threat to civic space thus remains (ICNL, 2021[73]). In Peru, a Police Protection Act adopted in March 2020 confirmed that the police was exempt from criminal liability and also expressly repealed provisions of the Law on the Use of Force by the Peruvian Police, which had established the principle of proportionality in the use of force by every police officer. According to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, this amendment contravenes applicable international standards (OHCHR, 2020[74]).

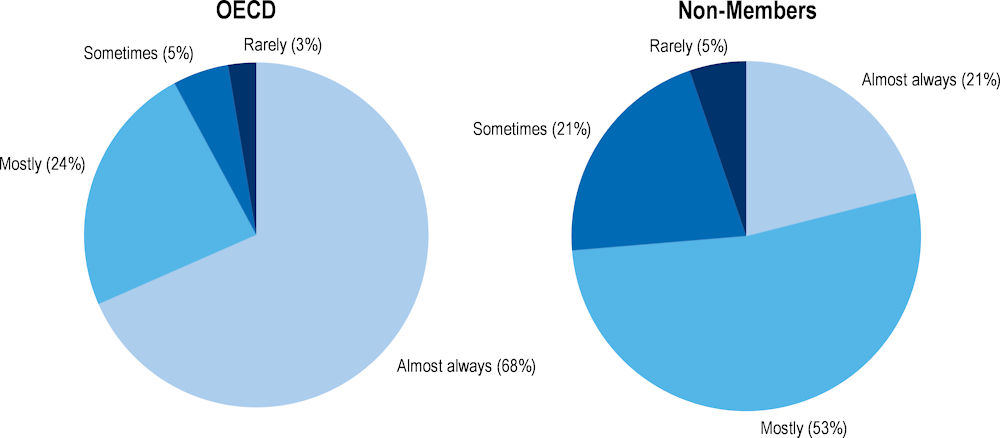

The V-Dem Institute’s indicator on freedom of peaceful assembly, which is based on expert evaluation (Varieties of Democracy Institute, 2021[75]),34 shows that in 68% of all OECD Members, state authorities almost always allow and actively protect peaceful assemblies, except in rare cases of lawful, necessary and proportionate limitations (Figure 2.9). However, there are some exceptions. For example, almost one‑quarter (24%) of OECD Members mostly allow peaceful assemblies and only in rare cases arbitrarily deny citizens the right to assemble peacefully: 2 OECD Members (5%) sometimes arbitrarily deny citizens the right to assemble peacefully and 1 country rarely allows peaceful assemblies.

The situation is more challenging in non-Members where state authorities almost always allow and actively protect peaceful assemblies in 21% of respondents. In more than half (53%) of respondents, state authorities mostly allow peaceful assemblies, while in 21%, state authorities sometimes allow peaceful assemblies. In 1 country (5%), state authorities rarely allow peaceful assemblies.

Figure 2.9. V-Dem Institute indicator for freedom of peaceful assembly, 2021

Note: “OECD” refers to all 38 OECD Members, “non-Members” refers to the 19 non-Members that participated in the 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government. V-Dem asks: “To what extent do state authorities respect and protect the right of peaceful assembly?”. Answers range from 1 to 4, with the least democratic response being “0” and the most democratic being “4”. Responses range from:

0: Never. State authorities do not allow peaceful assemblies and are willing to use lethal force to prevent them.

1: Rarely. State authorities rarely allow peaceful assemblies but generally avoid using lethal force to prevent them.

2: Sometimes. State authorities sometimes allow peaceful assemblies but often arbitrarily deny citizens the right to assemble peacefully.

3: Mostly. State authorities generally allow peaceful assemblies but in rare cases arbitrarily deny citizens the right to assemble peacefully.

4: Almost always. State authorities almost always allow and actively protect peaceful assemblies except in rare cases of lawful, necessary and proportionate limitations.

For the purposes of data visualisation, the authors have designated categories to countries that scored within 0.5 of each of the 5 options (e.g. a score of 2.5 and above was equated to 3, while below 2.5 was equated to 2).

Source: V-Dem (2021[75]), The V-Dem Dataset, https://www.v-dem.net/vdemds.html.

Key measures to consider on implementation challenges relating to peaceful assembly

Actively facilitating the right to peaceful assembly, including by ensuring that law enforcement agencies involved in policing assemblies act in line with international guidance in respecting the rights of participants and bystanders. An emphasis on de-escalation tactics can help to ensure the avoidance of the use of force during protests or, where it is unavoidable, to ensure that it is tempered by strict operating procures and guided by the principles of proportionality, necessity, precaution, legality and accountability to avoid harmful consequences.

2.1.3. Freedom of association

Associations are crucially important for the proper functioning of any democracy; indeed, the European Court of Human Rights has recognised that the participation of citizens in the democratic process is to a large extent achieved through people belonging to associations, in which they exchange with each other and pursue common objectives collectively.35 The court has further found that the failure to respect formal legal requirements cannot be considered such serious misconduct as to warrant the outright dissolution of an association.36 The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) has also noted the right of individuals to associate freely, without interference from public authorities37 and has found that the free and full exercise of this right imposes on states the duty to create an enabling environment in which associations can operate (this same principle has been confirmed in the OSCE/ODIHR-Venice Commission Guidelines on Freedom of Association).38

Legally mandated exceptions and conditions

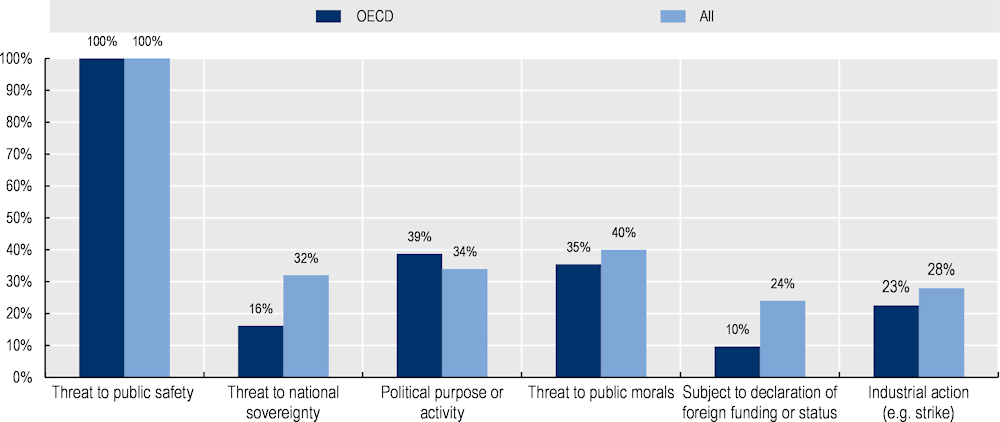

Figure 2.10 illustrates a number of common exceptions, exemptions or conditions to freedom of association.

Figure 2.10. Legally mandated exceptions to freedom of association, 2020

Note: “All” refers to 50 respondents (31 OECD Members and 19 non-Members). Data on Austria, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Ecuador, Germany, Greece, Honduras, Ireland, Italy, Korea, Lebanon, Mexico, Norway, Panama, Peru, the Philippines, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Türkiye, Ukraine and United Kingdom are based on OECD desk research for at least one of the categories and were shared with them for validation.

Source: 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government.

Public safety, public order and national sovereignty

Figure 2.10 shows that, in all respondents, laws state that associations seen as posing a threat to public safety or public order39 may face bans or other restrictions on their freedom of association rights. While most OECD Members have legal provisions that allow restrictions on freedom of association in the interests of national security, only 32% of all respondents and 16% of OECD Members have confirmed that such restrictions are also possible in the interests of protecting or maintaining national sovereignty.40 In most cases, the relevant provisions link national sovereignty to interests set out in international instruments, such as national security and public safety and order.

The joint Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) and Venice Commission Guidelines on Freedom of Association (2015[76]) have recommended a narrow interpretation of the legitimate aims justifying restrictions on freedom of association on the basis of national security and public safety.41 At the same time, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association has emphasised that the protection of national sovereignty is not, in itself, listed as a legitimate reason for limiting freedom of association in relevant international human rights instruments.42

Public morals

Legislation in 40% of all respondents and 35% of respondent OECD Members provides for limitations in cases where associations are seen as posing a threat to public morals (Figure 2.10). The joint OSCE/ODIHR-Venice Commission Guidelines on Freedom of Association (2015[76]) have recommended a narrow interpretation of the legitimate restrictions on freedom of association based on public morals.43 Such threats should thus not be abused to discriminate against associations protecting and advocating for the rights of particular groups, for example, such as LGBTI groups.

Political purpose or activity

A political purpose or activity of associations may lead to limitations in 34% of all respondents and 39% of respondent OECD Members (Figure 2.10). While in most countries, associations generally have the right to criticise public policies, restrictions on the political engagement of CSOs are related to specific situations. Limitations can be: i) linked to CSO activities related to political parties and elections (registering a candidate for election; supporting candidates or an election campaign; direct or indirect financing of a political party or elections); ii) apply to a wider spectrum of public policy activities (in addition to election campaigning, lobbying for or against specific laws, engaging in public advocacy, pursuing interest-oriented litigation or engaging in the policy debate on any issue); or iii) be related to a specific legal status, e.g. with limitations for organisations with public benefit or charity status (for a detailed discussion, including country examples, see Section 5.2.2 on activities of CSOs in Chapter 5).

As far as an association’s political activity and purpose are concerned, the joint OSCE/ODIHR/Venice Commission Guidelines on Freedom of Association (2015[76]) recommend that associations should have the right to participate in matters of political and public debate, while the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers has stressed that associations should be allowed to support particular candidates or parties in an election or referendum, provided that they are transparent about it and that such support is covered by legislation on the funding of elections and political parties (CoE, 2007[77]).

Declaration of foreign funding

While the receipt of funds is regulated by law in most countries and is subject to conditions imposed through international anti-terrorism and anti-money laundering frameworks, only 24% of all respondents and 10% of respondent OECD Members acknowledged that receipt of foreign funds is subject to a declaration (Figure 2.10). Certain countries, notably Israel, Morocco, Tunisia and Türkiye, impose legal requirements or conditions on all associations receiving foreign funding, mostly involving additional reporting obligations, with sanctions imposed on associations for non-compliance (Section 5.4.1 in Chapter 5).

The UN Special Rapporteur on freedoms of assembly and association has highlighted the right of associations to seek, receive and use financial, material and human resources, whether domestic, foreign or international, for the pursuit of their activities, as these are essential to their existence and operations.44 In addition, the Special Rapporteur, the IACHR and the OSCE/ODIHR/Venice Commission Guidelines on Freedom of Association (2015[76]) have noted with concern state legislation and practice restricting or blocking associations’ access to resources on the grounds of the nationality or country of origin, and the stigmatisation of those who receive such resources (Section 5.4).45 Guidance in this area aims to ensure that any such restrictions on associations are narrowly interpreted and applied, so that they neither completely extinguish the right to freedom of association nor encroach on its essence. In particular, as noted by the UN Human Rights Committee and the European Court of Human Rights, countries wishing to prohibit or dissolve associations should be able to demonstrate that such action is necessary to avert a real threat to national security or democratic order and that less intrusive measures would be insufficient to achieve this purpose.46

Industrial action

Figure 2.10 shows that 28% of all respondents and 23% of OECD Members confirmed that while industrial actions or strikes are permissible, constitutions, case law or labour laws set out specific safeguards or legal requirements or only permit certain kinds of strikes. In Lithuania, for example, the relevant service statutes prohibit certain public officials working in sectors providing urgent services, such as police officers or firefighters, from going on strike. In Ukraine, civil servants, members of the police and of the army are not allowed to organise or participate in strikes.

As per the case law of the European Court of Human Rights, complete bans on certain public officials exercising their right to strike require sufficient and solid justification, including for workers providing essential services.47 At the same time, the court has found that a ban on the right to strike of law enforcement agents may be justifiable on public safety grounds and to prevent disorder, given that they are armed and that they need to provide uninterrupted service.48 Similar considerations apply to members of the armed forces, provided that they are not deprived of the general right to freedom of association.49

Key measures to consider on legal frameworks governing freedom of association

- Applying a narrow interpretation of the legitimate aims justifying restrictions on freedom of association.

- Ensuring that associations are free to seek, receive and use financial, material and human resources, whether domestic, foreign or international, in the pursuit of their activities and that any related restrictions are limited to those that are necessary to combatting criminal acts such as fraud, terrorism or money laundering.

Implementation challenges and opportunities, as identified by CSOs and other stakeholders

Freedom of association is an essential element of civic space as it guarantees the right of citizens to actively participate in movements ranging from informal associations to registered organisations and allows them to safeguard and promote issues that affect their lives. Restrictions in practice to this right include, for example, denials or revoking of registration for CSOs, restrictions on their activities, an increase in Strategic Lawsuit against Public Participation (SLAPP) cases against CSOs, difficulties in accessing predictable and consistent public funding, and targeting of groups focusing on particular issues. For a more in-depth discussion on the implementation of freedom of association, see Section 5.2.3 on challenges for an enabling environment for CSOs and Section 5.4.2 on challenges for funding in Chapter 5.

2.1.4. Right to privacy

Privacy or private life is a broad concept that covers a person’s physical and psychological integrity and may embrace multiple aspects of the person’s physical and social identity.50 As stated in international human rights instruments, interferences with this right are possible if they are not arbitrary or unlawful,51 meaning that they need to be based on law,52 be in accordance with international legal provisions, aims and objectives and be reasonable in particular circumstances.53 The American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR) provides protection against arbitrary or abusive interference with persons’ private life, and legitimate aims set out in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) include national security or public safety, as well as the economic well-being of the country, the prevention of disorder or crime, or the protection of health or morals.54 Notably, national sovereignty is not specified as a legitimate aim in itself.55 The European Court of Human Rights has stressed the importance of striking a fair balance between the competing interests of the individual with regard to the right to privacy and of the community as a whole.56

The protection of personal data is of fundamental importance to a person’s enjoyment of the right to a private life, which, as noted by the court, also extends to the collection and storage of private data by the state (Section 4.5 in Chapter 4).57 Generally, according to the case law of the court, interference with individuals’ right to private life are tolerable under the ECHR only where they are strictly necessary to safeguard democratic institutions.58 International human rights bodies have found that relevant legislation must specify in detail the precise circumstances in which such interferences may be permitted and must contain minimum safeguards against abuse.59

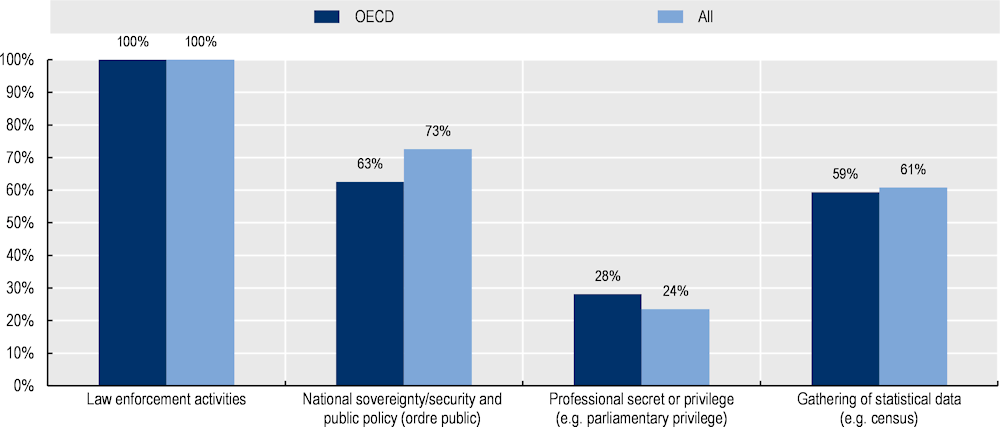

Legally mandated exceptions and conditions

As with other civic freedoms, the right to privacy is limited by certain exceptions, exemptions or conditions in domestic laws, the vast majority of which are permissible under the international legal standards mentioned above. As can be seen in Figure 2.11, all respondents have confirmed that international instruments, constitutions, criminal procedure laws or privacy laws state that interference with this right is permissible in the context of law enforcement activities, for example. Figure 2.11 further shows that 73% of all respondents and 63% of OECD respondents place restrictions on the right in order to maintain national sovereignty or security, or public order.

Further, 61% of all respondents, comprising 59% of OECD Members, have data protection laws and laws on statistics that specify that private data may be requested, obtained and processed in the context of gathering statistical data. In addition, in certain respondents, such as Austria, Canada and Ukraine, legislation provides exceptions to the rights of individuals to access their own personal data to protect professional secrets or privileges, for example, if granting such access could put a trade or business secret at risk (Austria) or in cases where it could impact solicitor-client privilege, the professional secrets of advocates or notaries, or patent or trademarks legislation, among others (Canada); 24% of all respondents and 28% of OECD respondents have this exception.

Legislation has been passed in recent years in some respondents to strengthen state responses against terrorism and other crimes by strengthening wire-tapping and similar capacities, notably in Australia (UN, 2018[78]), Germany (Fischer, 2021[79]) and the Netherlands (Houwing, 2021[80]). This has raised concerns among CSOs and international human rights bodies as it may risk compromising individuals’ privacy rights due to insufficient oversight mechanisms and safeguards to protect them. Similar considerations apply with respect to Türkiye, where following legal amendments in 2020, social networks are obliged to turn over user data to authorities, including for anonymous accounts if criminal cases are launched (Yackley, 2021[81]).

Figure 2.11. Legally mandated exceptions to the right to privacy, 2020

Note: “All” refers to 51 respondents (32 OECD Members and 19 non-Members). Data on Colombia, Guatemala, Ireland, Norway, the Philippines and Slovenia are based on OECD desk research for at least one of the categories and were shared with them for validation.

Source: 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government.

Key measures to consider on legal frameworks governing the right to privacy

Regularly reviewing whether interference with the right to privacy follows legitimate aims and is necessary and proportionate in that respect. Relevant legislation setting out exceptions to the right to privacy in a clear and comprehensive manner, particularly in the context of law enforcement activities or activities that protect national sovereignty or security, can help in this regard.

Implementation challenges and opportunities, as identified by CSOs and other stakeholders

One of the most contested aspects of the right to privacy is the intersection between privacy and state security interests, including surveillance. Human rights bodies and CSOs have repeatedly expressed related concerns in recent years (UN, 2020[82]; ECNL, 2020[83]; Article 19, 2020[20]). The UN Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy has expressed concern about the lack of detailed rules, procedures, guidance and independent oversight at both the national and international levels of surveillance practices, for example (UN, 2018[84]). This results in what he has described as a “patchwork quilt” of frameworks that do not adequately cover the use of surveillance by intelligence agencies, with more than 80% of UN members having no laws to protect privacy “by adequately and comprehensively overseeing and regulating the use of domestic surveillance” as of 2018 (UN, 2018[84]). Human rights bodies and CSOs have argued that the use of social media for such purposes is increasingly common. According to Freedom House, in 2019, at least 40 of the 65 countries covered by the Freedom on the Net Index (of which 15 are OECD Members) had instituted advanced social media monitoring programmes as part of ensuring security, public order or limiting disinformation (2019[85]). Within this context, many citizens are wary of both government and private sector activities related to surveillance. There is a perception of being monitored by governments among some CSOs in the EU, with 7% of CSOs responding to a survey by the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) reporting being surveilled by law enforcement in 2020 (Section 5.6.4 in Chapter 5; for a discussion and key issues to consider related to privacy concerns see sections on personal data protection, artificial intelligence and civic space in Chapter 4) (FRA, 2021[86]).

More recently, concerns have also been raised about COVID-19-related surveillance impinging on people’s right to privacy (Deutsche Welle, 2020[87]; Funk, 2020[88]; Freedom House, 2020[29]; UN, 2021[89]). The pandemic has resulted in a variety of means being used to track the spread of the infection, including: manual contact tracing; the use of Bluetooth, Global Positioning System (GPS) and cell tower tracking and bar and quick response (b/QR) codes and wearable technology; the use of cell tower and other data triangulation sources originally devised as counter-terrorist measures; mandatory check-ins with barcodes and QR codes and vaccine passports (UN, 2021[89]). The Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy has noted the danger of “surveillance creep” or the repurposing of data without permission. In a 2021 report on the pandemic, he noted that the actions taken by some governments had, whether knowingly or unknowingly, “crossed the line” in terms of human rights law and what is “appropriate and acceptable in democratic societies”, with the surveillance methods being used for public health and intelligence gathering purposes becoming blurred and merging, potentially paving the way for the normalisation of intrusive measures (UN, 2021[89]).

Key measures to consider on implementation challenges relating to the right to privacy

- Strengthening mechanisms for the independent authorisation and oversight of state surveillance to ensure that intrusive and arbitrary measures do not become the norm.

- Establishing and maintaining, at a minimum, an independent external authority responsible for authorising and overseeing surveillance measures undertaken by law enforcement agencies to ensure that activists and CSOs conducting lawful activities are not arbitrarily affected. Greater transparency in this area and systematic human rights-based impact evaluations, undertaken with non-governmental actors, could also help to ease concerns about the arbitrary targeting of civil society.

2.1.5. COVID-19-related changes to legal frameworks in OECD Members

As a response to the outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic in early 2020, most countries took immediate legal measures to protect citizens and communities, for which there was widespread public support. While such measures were deemed essential to limit and mitigate the effects of the pandemic and were widely supported by the public, they also restricted civic space, underpinning concerns about the risk of democratic backsliding as a result of the pandemic (Alizada et al., 2021[90]; OECD, 2021[91]). At the start of the pandemic, 21 OECD Members 60 out of 38 declared a state of emergency61 to provide the executive with special powers to prevent the spread of the virus (V-Dem Institute, 2021[92]; ICNL, 2021[93]). By the end of June 2021, 12 of these OECD Members62 were still operating under a state of emergency legislation, indicating a trend towards normalising legislative frameworks over time. The 17 OECD Members that did not declare a state of emergency opted to use other exceptional legal instruments or measures to address the pandemic, as discussed in Box 2.2. As of November 2022, only one OECD Member had emergency measures in place to address the COVID-19 pandemic. Three OECD Members had states of emergency in place, following the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine.

In the majority of OECD Members, emergency measures translated into extensive law-making powers for the executive, sometimes with limited or near to no external and above all parliamentary scrutiny, which was exacerbated by the fact that numerous parliaments were hampered by government lockdowns, and there was frequently no opportunity for remote voting or debate on new laws, practices or technologies being put in place (Murphy, 2020[94]). In a number of OECD Members, the permissible duration of states of emergency and executive ruling by decree is limited and states of emergency may only be extended with the approval of, or upon the initiative of, parliament (though there are also examples where this is within the powers of the government) or become invalid if parliament does not approve them or convert them into law at a later date. In certain countries, parliaments reacted to initially wide and unchecked government powers by later passing legislation foreseeing greater oversight and control powers for parliaments.