This chapter presents insights from additional analysis carried out for the EU only, based on the SME Scoreboard dataset from the EUIPO and the ORBIS database from Bureau van Dijk.

Risks of Illicit Trade in Counterfeits to Small and Medium-Sized Firms

4. IPR Infringement and Enforcement among EU SMEs

Rate and type of IPR infringed

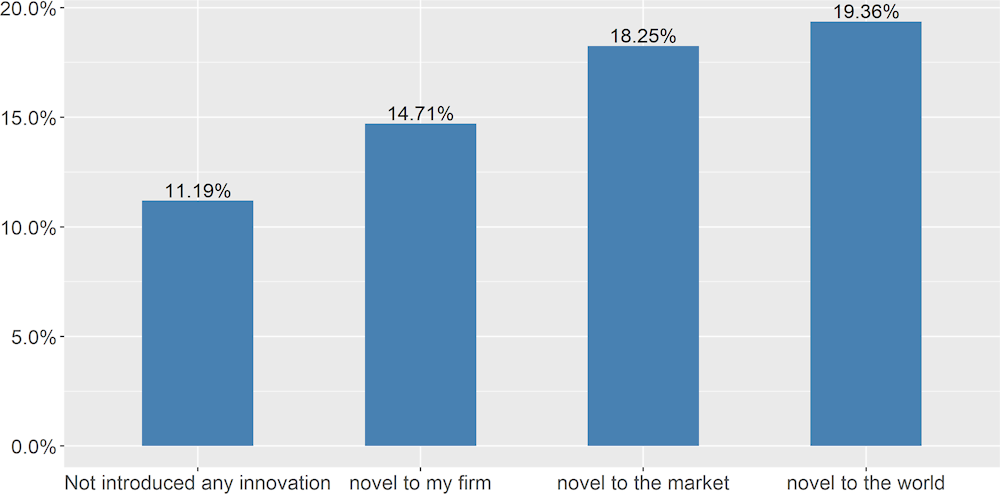

Among SMEs which have registered intellectual property rights, 15% have experienced an infringement of any type of IPR they own. However, as Figure 4.1. shows, this infringement rate is related to their degree of innovation overall. IPR owners that had introduced improvements in the previous three years that were novel to the world reported an infringement rate that was over 8 percentage points higher (19.4%) than those that had not introduced any innovation (11.2%) over that period. The rate of infringement among the IPR owners that introduced improvements novel to their market is also markedly higher than among firms that did not introduce any innovation, or implemented changes that were only novel to their firm.

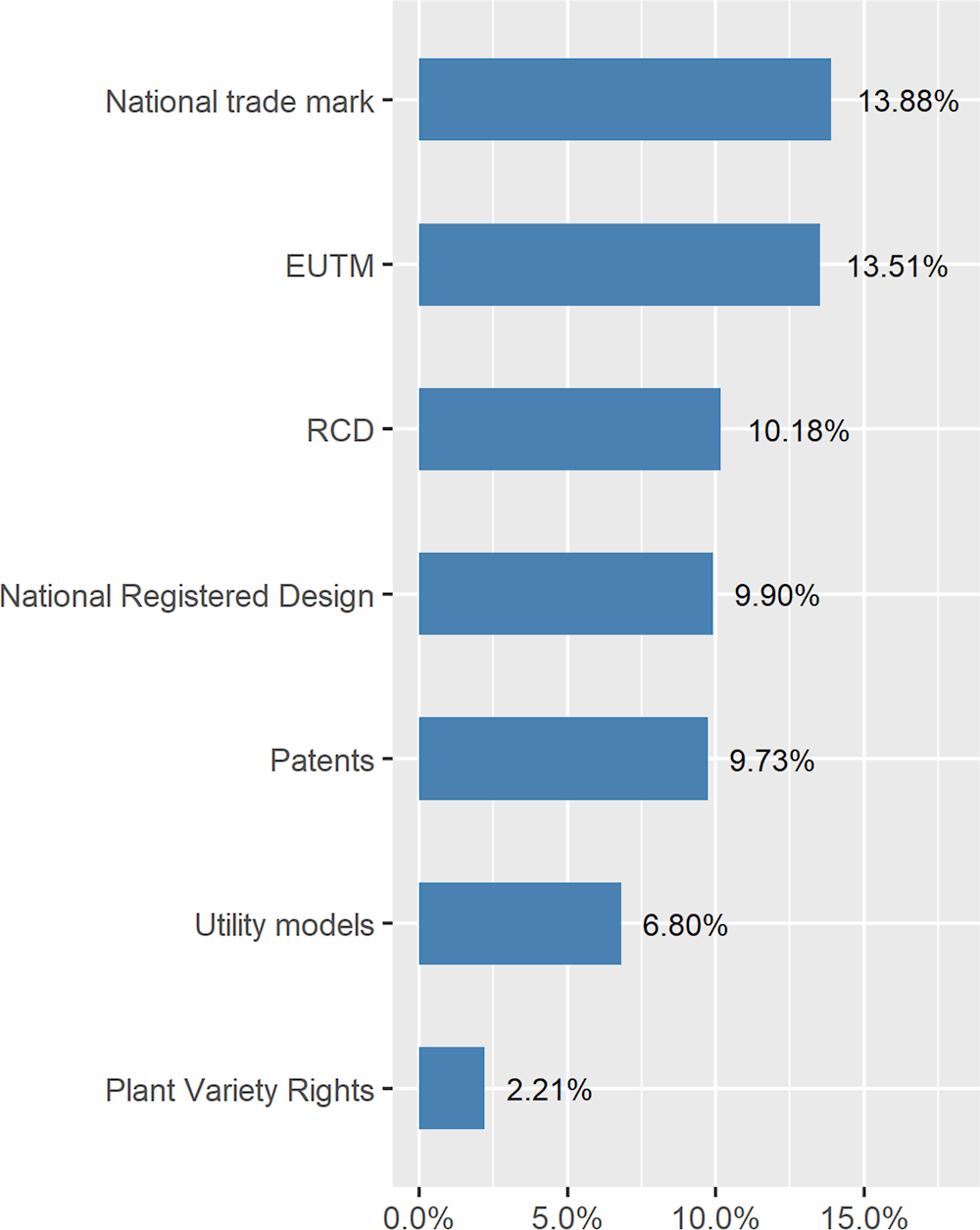

National and EU trademarks are the types of IPR most prone to infringement. As Figure 4.2 shows, over 13% of the SMEs owning either of these two types of trademarks suffered their infringement. The rate for registered designs is approximately 10%, whether registered community designs or national registered designs. The infringement rate reported by the owners of patents is only slightly lower than for national registered designs, at 9.7%. The lowest infringement rates are for utility models and plant variety rights, with the latter barely exceeding 2%.

Figure 4.1. Infringement rates among SME IPR owners, by degree of innovation, 2022

Note: N=3985 SMEs which confirmed having registered IPR and reported the type of innovation introduced in the previous three years, if any. Based on Q15: “Has your company ever suffered from IP infringements for any of the following IP types?”

Source: EUIPO (2022), 2022 Intellectual Property SME Scoreboard, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2814/28513.

Figure 4.2. Infringement rates among SME IPR owners, by type of IPR, 2022

Note: N=4278 SMEs which confirmed having registered IPR. Based on Q15: “Has your company ever suffered from IP infringements for any of the following IP types?”

Source: EUIPO (2022), 2022 Intellectual Property SME Scoreboard, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2814/28513.

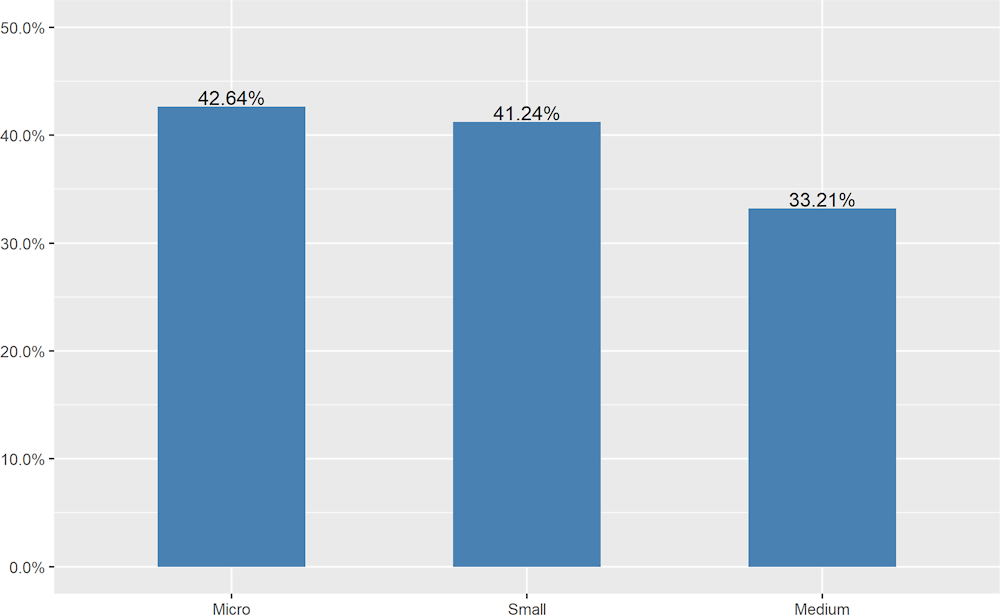

Market monitoring for infringements

Market monitoring is an important first step in the discovery and remedy of potential infringements of registered IPRs. Nevertheless, as Figure 4.3. shows, as many as 40% of SMEs do not monitor their markets for potential infringement of their IPR, or rely only on incidental information on infringement such as customer feedback or information from business partners. The share of firms not employing more systematic monitoring measures is highest among micro firms and lowest among medium-sized firms, with a difference of over 9 percentage points. The share of SMEs not systematically monitoring their IPRs is highest among trade mark owners (40%) and plant variety rights owners (37%). It is somewhat lower among design owners (35%) and utility model and patent owners (34%). This suggests that firm size and resources, and to a lesser degree the type of IPR owned, may be important elements in decisions over whether to engage in systematic monitoring for potential IPR infringements.

Figure 4.3. Monitoring of IPR infringements among SMEs, by firm size, 2022

Note: N=4278 SMEs which confirmed having registered IPR. Based on Q14: “How does your company monitor the market for possible infringement of its IP?” Only firms that chose Option 3 (I rely on the incidental information I receive from my business partners), Option 4 (Customer feedback) or Option 7 (I do not monitor the market) were counted.

Source: EUIPO (2022), 2022 Intellectual Property SME Scoreboard, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2814/28513.

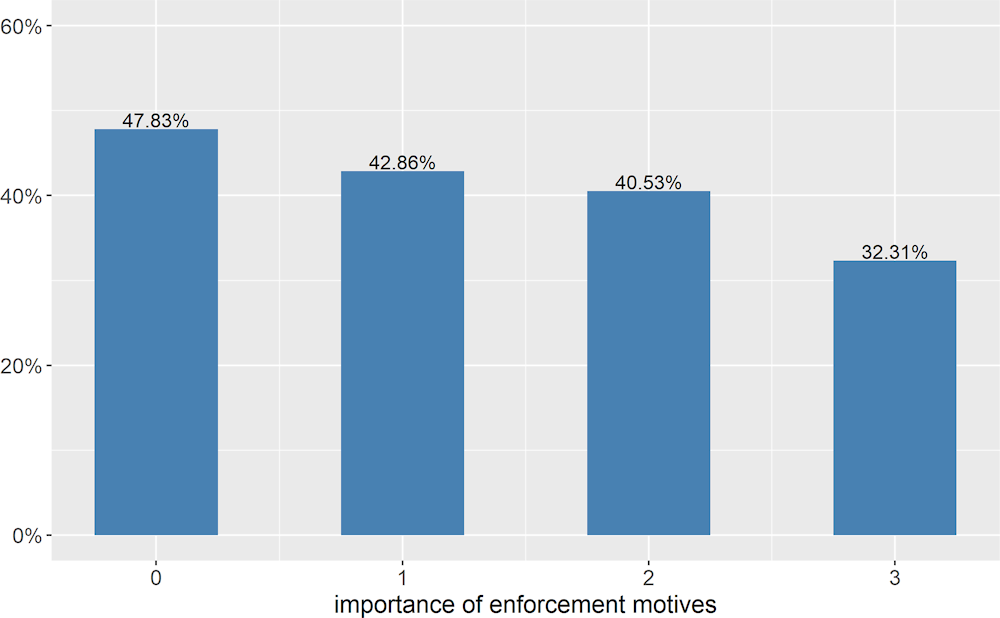

Another potentially important factor behind firms deciding to systematically monitor for IPR infringements is whether they feel registration is useful in discouraging infringement or enforcing their rights. To assess the strength of such awareness as the motive behind IPR registration, we devised a quantitative measure based on Question 8 of the SME IPR survey. This measure considers the number of “enforcement” motives chosen by a firm among the reasons behind its registration of IPR. Three out of the nine possible options in response to this question were related to enforcement: Option 1 (it guarantees better legal certainty of extent of protection); Option 2 (it helps me prevent others from copying my solutions, products or services) and Option 3 (it increases the chances of effective enforcement). How many of these options a firm chose was translated directly into a score for the importance of enforcement motives, as shown on the x-axis of Figure 4.4.. As the figure shows, firms citing more enforcement motives for registering their IPR are less likely to rely on incidental market monitoring or not monitor potential infringements at all.

Figure 4.4. Monitoring of IPR infringements among SMEs, by importance placed on enforcement, 2022

Note: N=4278 SMEs which confirmed having registered IPR. Based on Q14: “How does your company monitor the market for possible infringement of its IP?” Only firms that chose Option 3 (I rely on the incidental information I receive from my business partners), Option 4 (Customer feedback) or Option 7 (I do not monitor the market) were counted. The x-axis measures a proxy for the importance of “enforcement” reasons behind the decision to register IPR registration, as explained in the text.

Source: EUIPO (2022), 2022 Intellectual Property SME Scoreboard, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2814/28513.

These analyses suggest that firm size and registration motivations are related to how firms monitor the market for potential infringement of their IPR. The larger the firm, or the more important enforcement motives were in deciding to register IPR, the more effort it will put into market monitoring for potential infringements, employing measures that go beyond simple incidental information from clients or business partners. However, the analysis did not find any strong relationship between the degree of novelty of firms’ innovations and their infringement monitoring efforts.

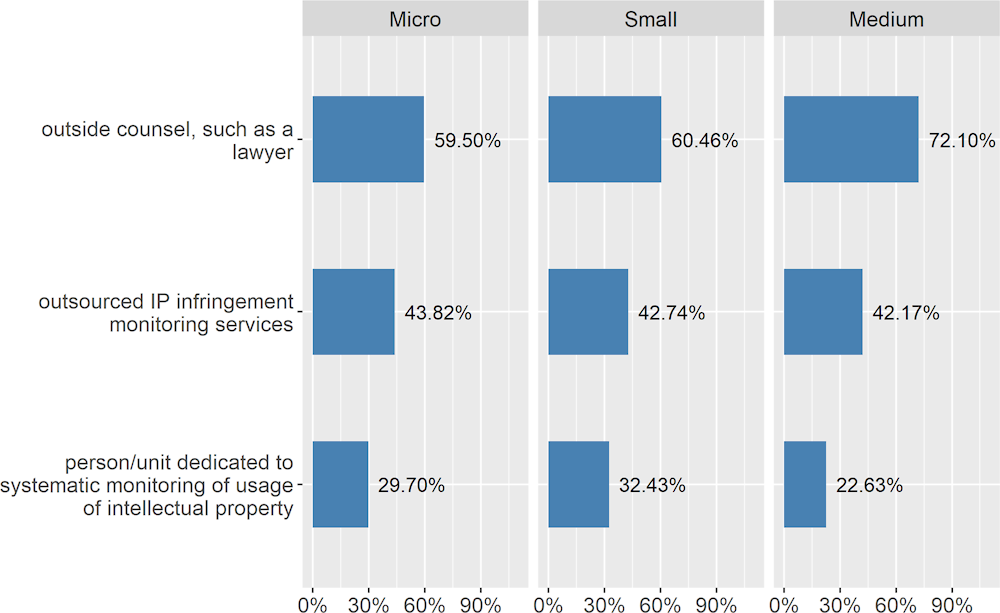

Figure 4.5. Market monitoring methods among SMEs, by firm size, 2022

Note: N=2574 SMEs which confirmed having registered IPR and at least one of the options shown on the plot for Q14: “How does your company monitor the market for possible infringement of its IP?”

Source: EUIPO (2022), 2022 Intellectual Property SME Scoreboard, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2814/28513.

As Figure 4.5. shows, use of outside counsel is the commonest systematic measure employed to monitor markets for potential infringements. Approximately 60% of micro and small SMEs with registered IPR which do not rely only on incidental information for detecting IPR infringements reported using this option. Among medium-sized firms, the share exceeds 72%. Slightly over 40% of those SMEs employing systematic monitoring measures used outsourced infringement monitoring services, with little difference across size groups. The least popular way of monitoring the market for all sizes of firms is to appoint a dedicated employee. The ranking of monitoring measures looks the same among the owners of all types of IPRs, with only slight differences in the share of firms employing each measure.

Impact of infringement

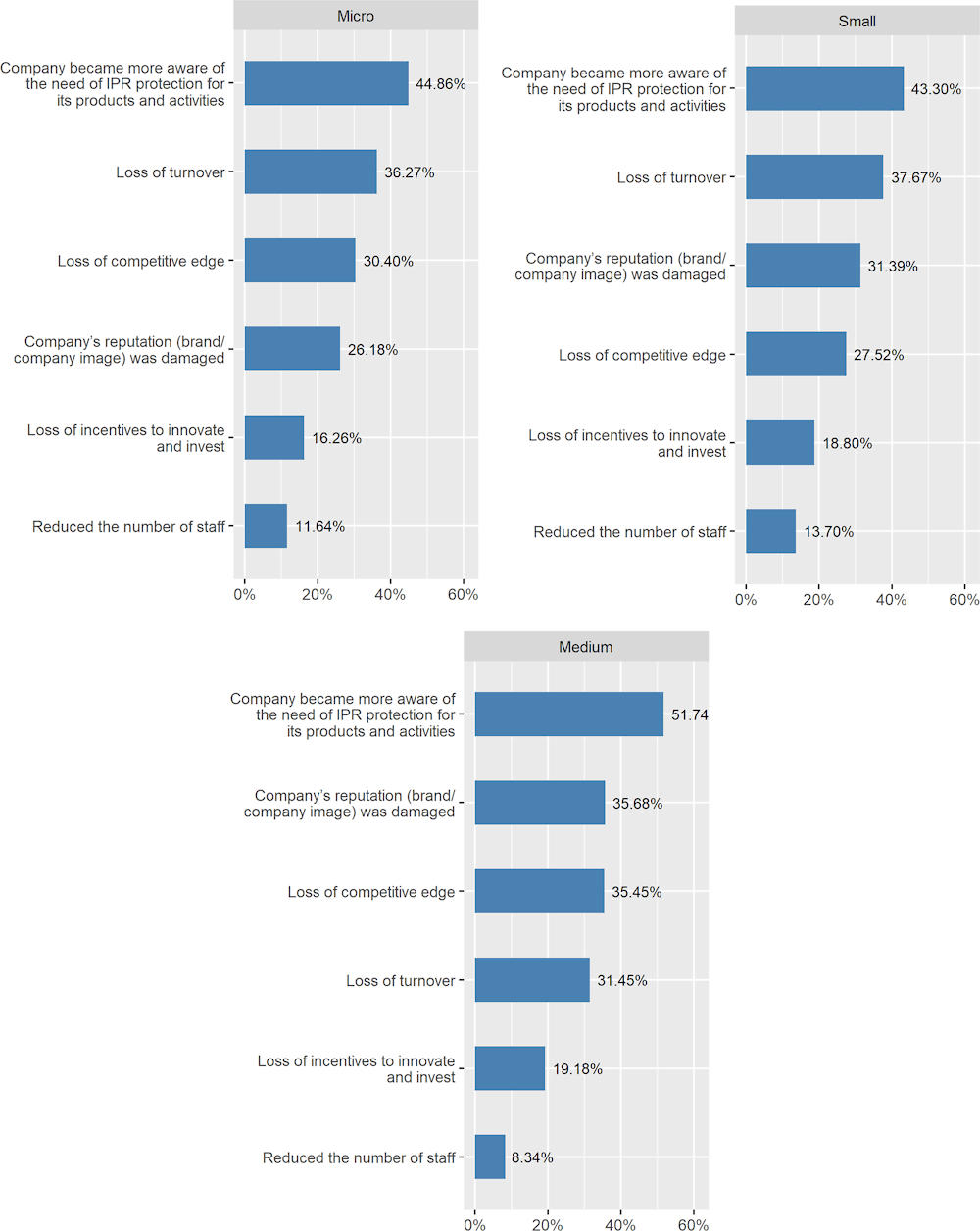

Figure 4.6. Impact of IPR infringement on SMEs, by firm size, 2022

Note: N=1226 SMEs which confirmed having registered IPR, declared being a victim of infringement and provided information on the novelty of implemented innovation, if any. Based on Q16: “How did the infringement affect your company? Please indicate all options that apply.”

Source: EUIPO (2022), 2022 Intellectual Property SME Scoreboard, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2814/28513.

Among SMEs in all size classes, the dominant impact of infringement was greater awareness of the need to protect IPR Figure 4.6. Concerning understanding, many industry experts highlight aspects related to the low quality of counterfeits and the legal risks associated with health and safety threats posed by fakes to unaware consumers. Put differently, for many SMEs presence of counterfeits on the markets increases the probability of being sued by consumers who had problems with fakes and who have bought them believing they were genuine. For SMEs, such potential legal actions from unhappy consumers imply a risk of high costs and significant reputational damage.

The second most frequent impact among micro and small firms was the loss of turnover, but strikingly, this was only ranked fourth among medium-sized SMEs. Instead, these relatively larger firms were more likely to cite reputational damage and the loss of their competitive edge as the impact of IPR infringement.

The notion of the damaging impact of counterfeiting on the innovativeness and competitive edge of SMEs was highlighted in an interview by an owner of an innovative startup, who noted: “We would be much bigger and would have developed three other lines of products if we did not have to compete with all the copy products.”

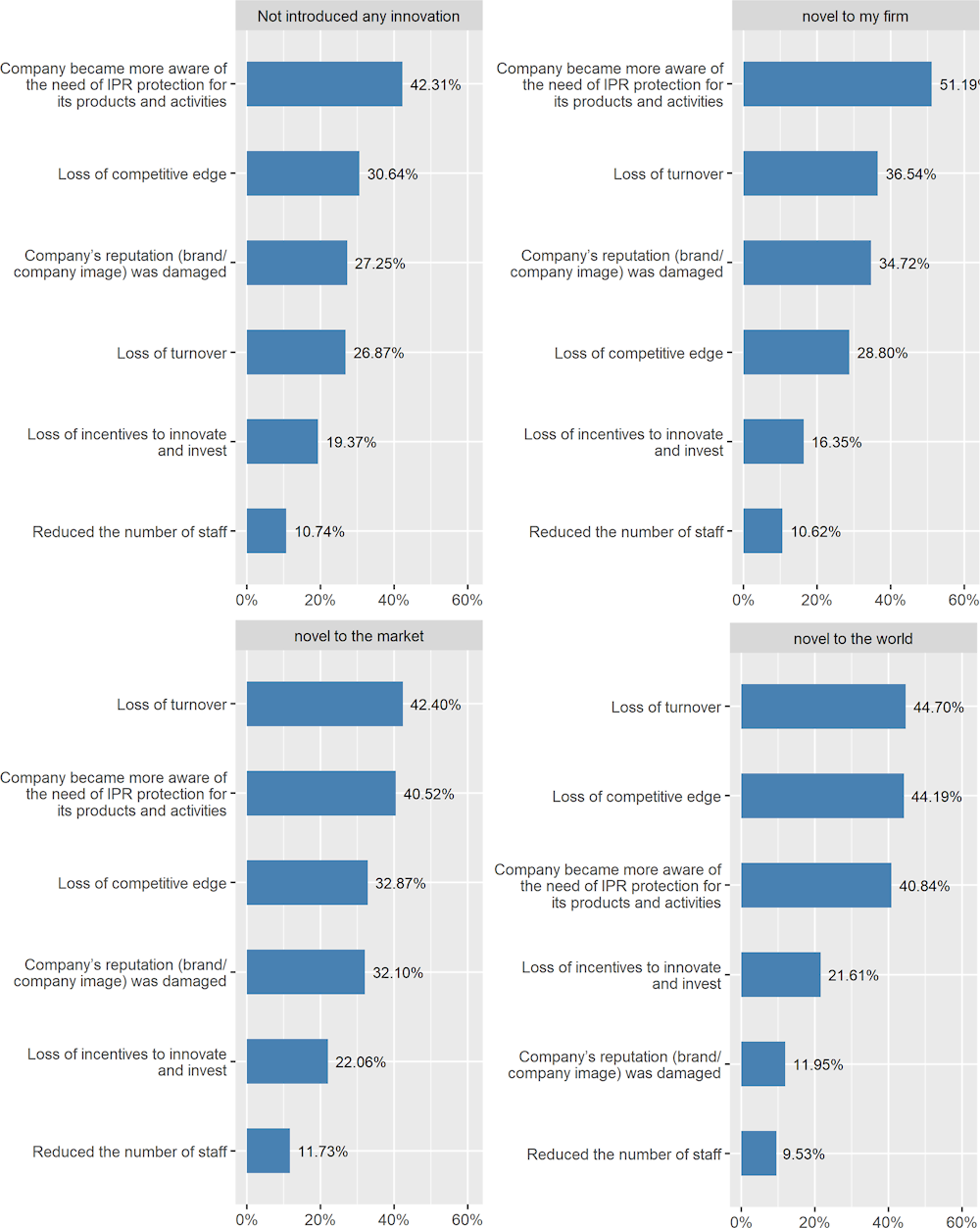

As Figure 4.7. shows, the impact of IPR infringement varies more according to the innovativeness of the firm than its size. Among firms that did not introduce any recent improvements or only those novel to the firm, the dominant impact remains greater awareness. But for the firms that implemented more radical innovations, the main impact was loss of turnover. Over 40% of firms that introduced improvements at least novel to the market and suffered from IPR infringements indicated that they experienced the loss of turnover as a result. In addition, for the SMEs that introduced improvements that were new to the world, loss of competitive edge was the second most frequently reported outcome.

Figure 4.7. Impact of IPR infringement on SMEs, by degree of innovation, 2022

Note: N=1139 SMEs which confirmed having registered IPR, declared being a victim of infringement and provided information on the novelty of implemented innovation, if any. Based on Q16: “How did the infringement affect your company? Please indicate all options that apply.”

Source: EUIPO (2022), 2022 Intellectual Property SME Scoreboard, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2814/28513.

Enforcement of IPR

According to the survey results, direct negotiation with the infringer is the most popular way to enforce IPR for all SMEs, regardless of size. According to the industry delegates, this way works only in the case of patents infringements. In the case of counterfeiting, submitting takedown notices to Internet platforms is the most popular form of enforcement among micro and medium-sized firms.

Interestingly, when submitting takedown notices, SMEs often do not recall their registered trademark, but highlight potential infringement of other IPs such as copyrights or patents. For copyrights, it happens for example when an infringing offering uses an image on the packaging that was pirated from a genuine one, pirated instructions, or pirated advertising images. In such case for an SMEs relying on copyright infringements is more effective, since the protection of copyrights is global, while trademark protection is economy specific. In cases when an SME does not have its trademark registered in the economy of operation of a given on-line platform operates, the legal costs of action that relies on trademark infringement might be too long and risky, and the outcome uncertain. In such cases relying on copyright infringement promises a higher rate of success and take-down of the infringing listing from the platform.

Patents infringement are used to combat counterfeiting, in case of specific solutions provided by on-line platforms to combat IP infringement and attract innovative companies. Such programs (e.g. Amazon’s Neutral Evaluation Program) provide innovative SMEs with a simplified path to fight sellers offering IP infringing products. In many cases these programs are more effective than other ways to enforce SMEs rights. In addition, successful enforcement of SMEs rights, strengthens its reputation with the on-line platform, as an innovative and trusted business.

However, approximately 11% of firms whose IPR has been infringed do not enforce their rights. When asked about most salient reasons for not doing so, the most frequent answer was that enforcement procedures are too lengthy (Figure 4.8). Over one-quarter of the firms that did not decide to enforce their rights explained that the legal fees would be too high, and slightly less than one-fifth indicated the barrier was high court fees. Structured interviews with industry experts re-confirm these findings. SMEs perceive the existing enforcement methods as very costly (in terms of time and resources) and uncertain. In addition, SMEs often lack appropriate information about ways their IP rights can be enforced.

Figure 4.8. Reasons for not fighting IPR infringements among SMEs, 2022

Note: N=135 SMEs which confirmed having registered IPR, declared being a victim of infringement and declared that they were not fighting the infringement. Based on Q18: “Why did you decide not to fight the infringement? Please indicate all reasons why you would refrain from court procedures.”

EUIPO (2022), 2022 Intellectual Property SME Scoreboard, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2814/28513.

IPR infringement affecting SMEs. Focus on survival

So far the analysis has looked at existing SMEs that have suffered from counterfeiting but are still active on the market. However, as noted in interviews with industry delegates, in many cases counterfeiting pushes small companies out of the market, either by forcing the owners to close the business, or, in some cases, by leading to bankruptcy.

This section aims to quantitatively verify the hypothesis that counterfeiting can indeed push SMEs to quit the market. The main research question is therefore: Are SMEs that suffered from infringement of their intellectual property rights less likely to survive than those that did not experience IPR infringement?

The existing academic literature focuses much more on the survival of newly created firms than of mature ones. Nevertheless, it provides some interesting conjectures that may also inform investigation of relationship between IPR infringement and probability of survival of SMEs in general. (Geroski P., 1995[11]) hypothesised that small firms may face relatively low barriers to entry. Therefore, every year large numbers of new firms are set up. However, a substantial number of those firms face high barriers of survival. The barriers are particularly high in first few years after entry and become somewhat lower once firms mature, however the risk of market failure is higher for SMEs than larger firms.

Smaller companies suffer from many disadvantages in comparison to larger firms. They are particularly constrained regarding access to finance (European Commission, 2013[12]). Limited access to finance means they cannot afford to offset risks by pursuing the sort of diversified strategies their better-endowed larger competitors can employ. Their relatively smaller scale of activity also means that SMEs can barely exploit any economies of scale. One of the most viable ways for ambitious SMEs to increase their odds of success is to experiment with new combinations of features (Stam E. et al., 2012[13]) distinguishing their offer from competitors, often by tailoring their products and services to specific market niches (Brüderl J. et al, 1992[14]); (Heirman A. and Clarysse B., 2006[15]). This strategy requires investment in market research and the development of new technologies or creation of new appealing designs. The temporary exclusivity offered by IPRs may be especially important for financially constrained SMEs to help them recover the resources invested in those innovating activities. As seen in Chapter 2, innovative SMEs are more likely to use IPR than their non-innovating counterparts. Intellectual property infringement may be an additional blow to an SME’s market prospects that may tip the balance towards exit.

Data

To test this hypothesis, data from the 2016 edition of SME scoreboard have been merged with data from the Bureau Van Dijk Orbis dataset, reflecting the status in 2021 of firms that took part in the 2015 survey.1.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable survival has been developed based on Orbis. This database contains information about the 2021 status of the firms, including firms that took part in 2015 survey. However, this variable can have 15 different values describing various active statuses and various reasons for ceasing activities. Therefore, the original Orbis variable has been converted to the dummy variable survived, which was given the value true for all firms whose last-known status was "active” and false for firms with other statuses such as “dissolved”, "inactive”, “bankrupt” or "in liquidation”.

Main independent variable

The infringement variable has been calculated based on the answers to Question 6.2 (Has your company ever suffered from infringement of your IP?) and question 6.3 (What kind of IP was infringed?).

The infringement variable takes the value true for those firms that reported that a specific IPR had been infringed and that the firm had previously registered at least one IPR of the same type based on its answers to the Question 2.2 (You previously indicated that your company has registered IPRs. Could you please indicate which type of IPR and how many of each you registered?)

Control variables

Presumably, a firm has better chances of survival if it is linked to the larger and more experienced parent company. It may count not only on its know-how and expertise but also better access to financial resources in case of need.

Orbis includes information on whether a firm is independent or is part of a larger economic group. Based on this information a new variable has been created, taking the value of true where a firm’s Orbis record has been associated with information about a domestic or global ultimate owner, and false where no such information has been associated with a firm’s record.

The positive correlation between survival rates and both age and firm size has been documented in several studies (Audretsch D. B. and Mahmood T., 1995[16]); (Geroski P., 1995[11]). Therefore, our main control variables are the size and age of SMEs.

Size

This variable has been defined based on the most recent information about a firm’s turnover available up to 2015 – the year when the survey took place. The values of this variable have been transformed logarithmically before plugging into models.

Age

Age was defined as difference in years between the year in which the firm was set up and 2015, the year when the survey took place.

Innovative

Innovative was a dummy variable, based on the answers to Question 1.2 (In the last 3 years, did your enterprise introduce new or significantly improved products, processes, organisational changes, marketing changes, other). It takes the value true if the firm reported it had introduced any innovation and false if it did not.

NACE division

Based on Orbis information on the main economic activity of the company, this uses the two-digite European Classification of Economic Activities (NACE) division in which it operates.

Country of seat of a firm

Based on address information stored in Orbis.

Descriptive statistics

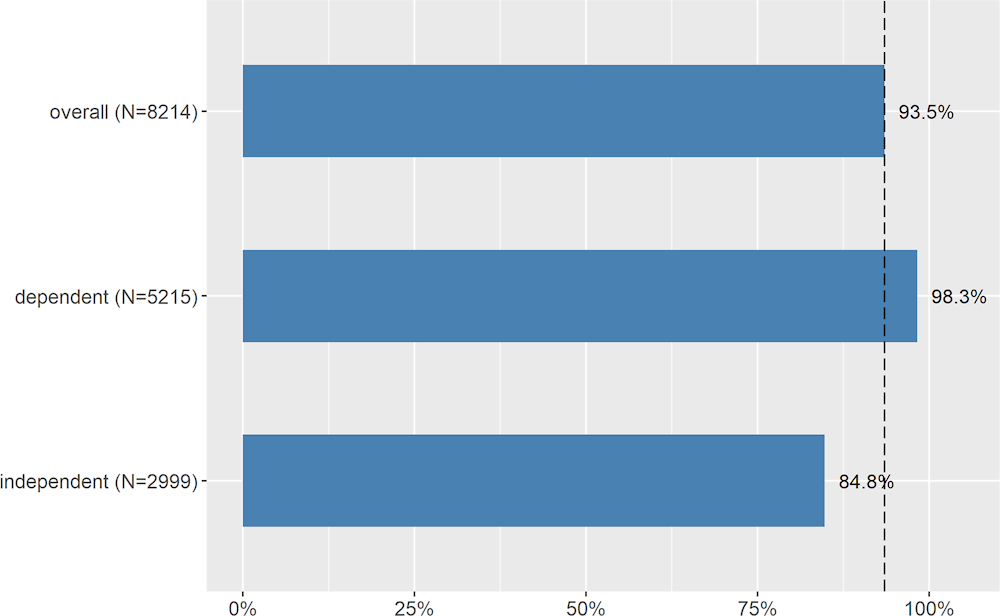

As Table 4.1 shows, the overall weighted survival rate within the entire sample of SMEs that took part in the 2016 SME Scoreboard is high, at 93.5%. However, there is a 13.5 percentage point difference in the survival rate between subsidiaries of other firms and fully independent firms, as shown in Figure 4.9.

Table 4.1. Descriptive statistics

|

Variable |

N |

Mean |

St. Dev. |

Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Suffered any IPR infringement |

8214 |

0.096 |

0.295 |

0 |

|

Patent infringement |

8214 |

0.024 |

0.154 |

0 |

|

Trade mark infringement |

8214 |

0.066 |

0.248 |

0 |

|

Design infringement |

8214 |

0.013 |

0.115 |

0 |

|

Survived |

8214 |

0.937 |

0.243 |

1 |

|

Dependent firm |

8214 |

0.635 |

0.481 |

1 |

|

Innovative |

8214 |

0.619 |

0.486 |

1 |

|

Age |

7996 |

21.2 |

16.2 |

18 |

|

Size (last turnover in the Euro) |

6868 |

5985 |

22710 |

2048 |

Table 4.2. Variables correlation matrix

|

any infr |

pat infr |

tm infr |

des infr |

survived |

dep |

inno |

age |

log size |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Any IPR infringement |

1 |

||||||||

|

Patent infringement |

0.48 |

1 |

|||||||

|

Trade mark infringement |

0.81 |

0.08 |

1 |

||||||

|

Design infringement |

0.35 |

0.11 |

0.15 |

1 |

|||||

|

Survived |

0 |

0 |

-0.01 |

0.01 |

1 |

||||

|

Dependent |

0.06 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.26 |

1 |

|||

|

Innovative |

0.14 |

0.11 |

0.08 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

1 |

||

|

Age |

0.07 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.05 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

-0.04 |

1 |

|

|

Size (log) |

0.11 |

0.06 |

0.09 |

0.05 |

0.07 |

0.24 |

0.07 |

0.26 |

1 |

Figure 4.9. Survival rates within the sample

Note: Share of firms with ‘active’ status in 2021 among the firms that took part in the 2015 SME scoreboard survey. Dashed line set at the mean for entire sample. Shares are calculated as weighted averages taking original weights from SME Scoreboard

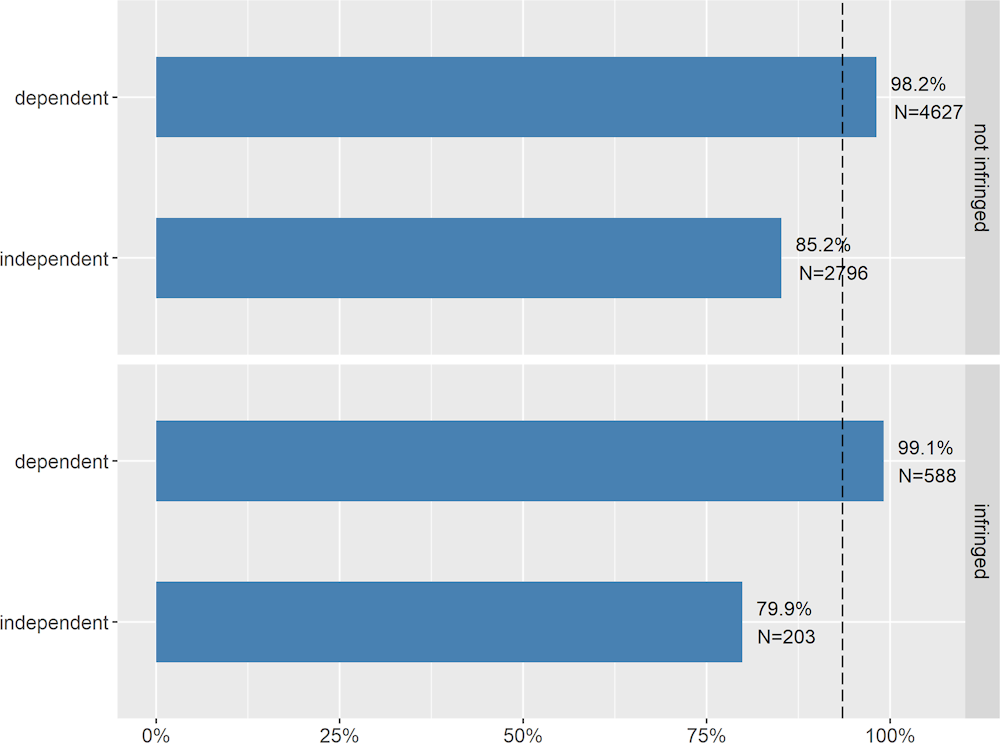

Figure 4.10 shows that this large difference in survival rates extends to sub-groups identified by their IPR infringement status. However, while the difference in the survival rate between dependent and independent SMEs that did not suffer from infringement amounts to 13 percentage points, this difference rises to over 19 percentage points among the firms that did suffer infringement. It is also worth noting that the independent SMEs that suffered from IPR infringement have an over 5 percentage-point lower survival rate than their counterparts that did not.

Figure 4.10. Survival rates among infringed and non-infringed firms

Note: Share of firms with “active” status in 2021 among the firms that took part in the 2016 SME scoreboard. Infringed status established based on any IPR infringement. The dashed line is the mean for the entire sample. Shares are calculated as weighted averages taking original weights from SME Scoreboard

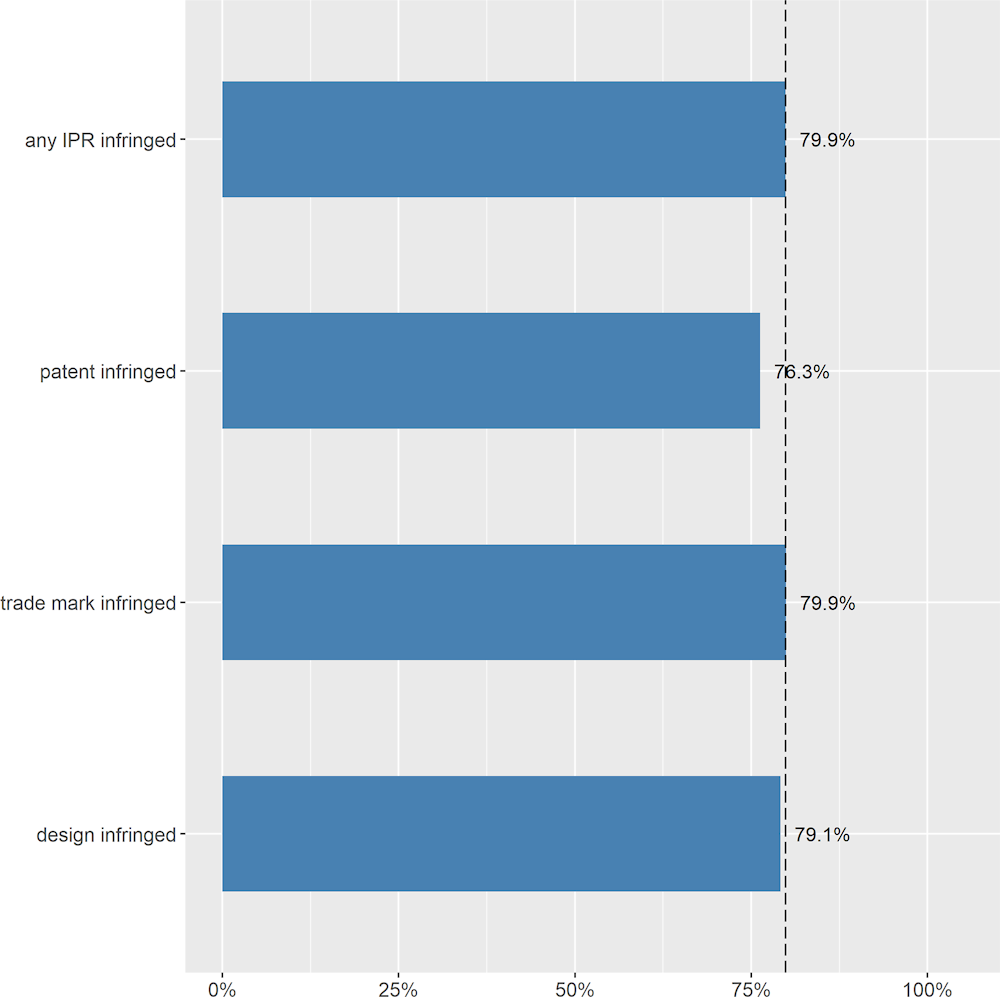

Focusing on independent SMEs that suffered from IPR infringement, Figure 4.11 leads to the conclusion that the biggest reduction in the survival rate is associated with firms that suffered from patent infringement. Their survival rate is over 3.5 percentage points lower than that of independent SMEs that suffered from trademark infringement and almost 9 percentage points lower than that of independent SMEs that did not experience any infringement. For SMEs that own patents, the patented invention usually denotes significant investment and risk associated with bringing new technology to the market, and failure to protect such an invention can be particularly costly.

Finally, the survival rate of independent SMEs that suffered from design infringement is almost 1 percentage point lower than SMEs that suffered from trademark infringement, and slightly over 6 percentage points lower than independent SMEs that had not suffered from IPR infringement.

Figure 4.11. Survival rates within independent SMEs with infringed IPR

Note: Share of firms with “active” status in 2021 among the firms that took part in the 2016 SME Scoreboard. The dashed line is the survival rate for the entire group of independent SMEs with any IPR infringement. Shares are calculated as weighted averages taking the original weights from the SME Scoreboard.

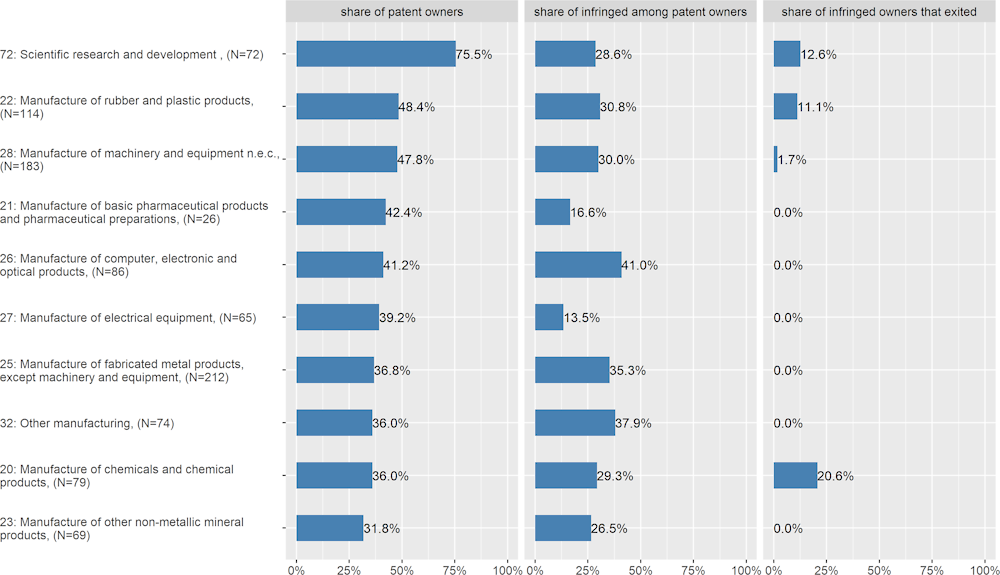

Figure 4.12. Sectorial infringement and exit statistics for patent owners

Figure 4.12 presents the statistics for the 10 NACE divisions with the highest shares of patent ownership in the sample (among divisions with at least 20 firms in the sample)2. Panel 1 presents share of patent ownership among SMEs representing each NACE division. Panel 2 shows the rate of infringement among those patent owners, and panel 3 shows the share of infringed patent owners that did not survive until 2021. The shares are calculated as weighed averages taking the original weights from the 2016 SME Scoreboard.

The figure indicates that patent infringement is particularly damaging to SMEs in the sectors Scientific research and development, Manufacture of rubber and plastic products, and Manufacture of chemicals and chemical products.

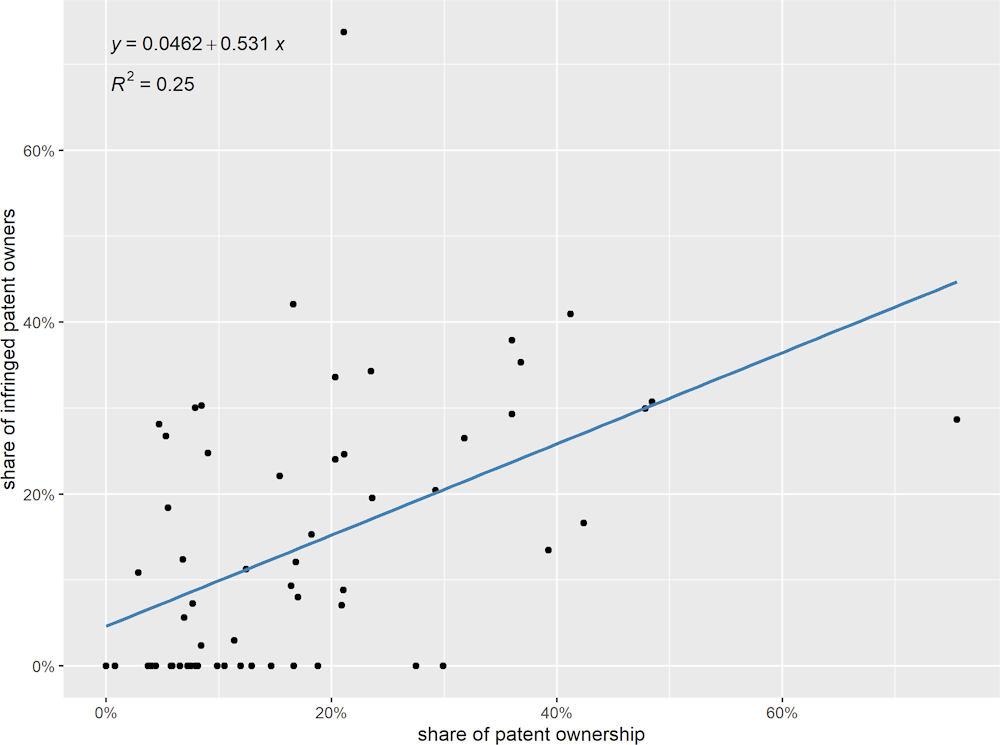

Figure 4.13. Relationship between patent ownership and patent infringement rate

Note: the figure presents the relationship between share of patent ownership and patent infringement rates calculated for NACE divisions with at least 20 firms in the sample. Both shares are calculated as weighed averages taking the original weights from the 2016 SME Scoreboard.

As shown in Figure 4.13, patent infringement rate is positively correlated with the share of patent ownership in the industry. It indicates that patent infringement poses greater challenges in industries where patent protection plays a bigger role in SMEs competitive strategies.

Econometric specification

The descriptive statistics presented in the previous section suggest that infringement may have some negative relationship with survival, especially among independent firms which cannot rely on assistance from their parent company.

As the dependent variable is a dichotomous variable indicating whether a firm had survived until 2021, the standard ordinary least squares model is not adequate for model estimation (Pampel F. C., 2020[17]); (Kennedy P., 2008[18]). Instead, a logistic regression model was used to model the association between the IPR infringement suffered by SMEs and the probability of survival. This method models the logarithm of the odds of survival as a linear combination of infringement event and a set of other crucial control variables.

Results of econometric models

Table 4.3 presents the results of logistic regression models explaining survival of the SMEs in the sample. As can be seen in the first column, where there is no control for the independent status of a firm, the coefficient of IPR infringement is negative, but not statistically significant. It becomes statistically significant once a control for the links with other companies is introduced – as in Models 2, 3 and 4. Its absolute value is 0.419 in Model 3, where the full range of control variables is implemented, including firms’ economic links, size, country of seat, the industries in which they are active, their innovative status and age.

The absolute value of the IPR infringement coefficient is the highest in Model 4 where the observations are restricted to independent firms only, confirming that the negative association between IPR infringement and odds of survival are the strongest for independent SMEs. The values of the IPR infringement coefficients in Models 2 to 4 are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

Table 4.3. Results of logistic models (full sample)

|

Dependent variable: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Survived |

||||

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|

suffered infringement |

-0.105 (0.166) |

-0.373** (0.181) |

-0.419** (0.209) |

-0.581** (0.239) |

|

dependent firm |

2.800*** (0.143) |

2.685*** (0.165) |

||

|

Size (log turnover) |

0.057 (0.038) |

0.011 (0.044) |

||

|

Constant |

18.453 (2,662.857) |

17.048 (2,456.959) |

16.196 (2,746.500) |

16.489 (3,762.424) |

|

Country control |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

NACE division control |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Innovative |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Age |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Observations |

8,031 |

8,031 |

6,739 |

2,209 |

|

Log Likelihood |

-1,654.347 |

-1,362.812 |

-997.916 |

-707.188 |

|

Akaike Inf.Crit. |

3,526.694 |

2,947.623 |

2,221.831 |

1,630.377 |

Note: * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01

Table 4.4 shows the results of logistic regression models run on the subsample of independent firms. For ease of reference, Column 1 reproduces the results of the same model as reported in Column 4 in Table 4.3. The independent variable of interest in this model represents any IPR infringement. The subsequent models replace any IPR infringement variable with specific variables representing infringement of a patent (Column 2), trademark (Column 3) and design (Column 4). The value of infringement coefficients therefore represents the change in the (log) odds of survival for firms suffering infringement of these specific IPRs compared with other independent SMEs that did not suffer such infringement. These models show that the reduction in survival odds is the highest for independent SMEs that suffered patent infringement. The value of the patent infringement coefficient is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

The value of the coefficient for trademark infringement is also negative confirming that, all other things being equal, independent SMEs that suffered from trademark infringement have lower chances of survival than independent SMEs that did not suffer from trademark infringement. This coefficient is however only statistically significant at the 90% confidence level. Finally, the model of design infringement (4) does not allow us to reject the hypothesis that survival chances of independent SMEs that suffered from design infringement are different from the odds of survival than independent SMEs that did not suffer from design infringement, holding other factors constant.

Table 4.4. Results of logistic models (independent SMEs)

|

Dependent variable: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Survived |

||||

|

any IPR (1) |

pat (2) |

tm (3) |

des (4) |

|

|

suffered infringement |

-0.581** (0.239) |

-1.238** (0.481) |

-0.509* (0.272) |

0.184 (0.656) |

|

Size (log turnover) |

0.011 (0.044) |

0.004 (0.044) |

0.010 (0.044) |

0.004 (0.044) |

|

Constant |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Country control |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

NACE division control |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Innovative |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Age |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Observations |

2,209 |

2,209 |

2,209 |

2,209 |

|

Log Likelihood |

-707.188 |

-706.954 |

-708.316 |

-709.935 |

|

Akaike Inf.Crit. |

1,630.377 |

1,629.908 |

1,632.631 |

1,635.869 |

Note: * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01

The models presented in Table 4.3 and Table 4.4 compare survival chances of SMEs affected by infringement to other SMEs, regardless of whether they are IPR owners or not. However, as shown in Figure 2.3, IPR ownership is correlated with higher innovativeness. This may increase the odds of better performance but also increases risks related to uncertain market reception of new products or services. This higher risk profile of IPR owners may therefore also be correlated with lower odds of survival. To control for these aspects, another set of regressions explaining survival odds was run, only within the group of owners of specific IPRs. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 4.5 below.

Table 4.5. Results of logistic models (IPR owners only)

|

Dependent variable: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Survived |

|||

|

pat (1) |

tm (2) |

des (3) |

|

|

suffered infringement |

-1.510*** (0.581) |

-0.010 (0.292) |

-0.631 (0.847) |

|

dependent firm |

4.891*** (0.805) |

3.818*** (0.350) |

5.222*** (0.880) |

|

Size (log turnover) |

-0.038 (0.118) |

-0.042 (0.071) |

-0.097 (0.152) |

|

Constant |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Country control |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

NACE division control |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Age |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Observations |

1,035 |

2,516 |

840 |

|

Log Likelihood |

-80.332 |

-300.276 |

-72.935 |

|

Akaike Inf.Crit. |

358.664 |

814.552 |

345.870 |

Note: * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01

All models were run within the subsample of patent, trademark and design owners. The infringement variable is defined as an infringement affecting respectively their patents, trademarks or design rights.

While all the coefficients related to IPR infringement have the expected negative signs, only the coefficient of the patent infringement in model 1 is negative and statistically significant at 99% confidence level. Model 1 confirms that patent owners that suffered from patent infringement have lower odds of survival than patent owners that did not suffer from patent infringement.

The infringement coefficients in models 2 and 3 have the expected negative sign, however they are not statistically significant. Thus, the null hypothesis that survival odds of the trademark or design owners that suffer from infringement of their IPRs are not significantly different from the survival odds of trademark or designs owners that did not suffer from infringement cannot be rejected based on the available data.

Discussion

With proper controls for other important factors that may be related to a firm’s survival odds, such as age, size, innovativeness or industry, the econometric analysis confirmed the initial intuitions from the descriptive analysis in the first section. Results from the full sample model (Column 3 of Table 4.3) indicate that an SME whose IPR is infringed has 34% lower odds of survival than one that did not experience infringement. Because the probability of survival in the entire sample is relatively high, this translates into a 3 percentage point lower probability of survival for an average SME.

The odds of survival are relatively lower for the subgroup of independent SMEs. Their odds of survival associated with IPR infringement are 44% lower than non-infringed independent SMEs. This translates into a much larger reduction in survival probability than in the general sample, amounting to almost 10 percentage points. The reduction in predicted probability of survival in comparison to an average independent SME is lower for independent SMEs that suffered from trademark infringement (almost 8 percentage points) but much higher for SMEs whose patents were infringed (over 20 percentage points).

Further analysis conducted within the subsample of IPR owners confirmed that patent owners that suffered from patent infringement have lower odds of survival than patent owners which did not experience infringement. In the case of trademark and design owners, the hypothesis that SMEs that suffered infringement have lower odds of survival than trademark and design owners without a history of infringement, has not found sufficient support in the data.

To summarise, in general, this analysis confirms the correlation between IPR infringement and the survival odds of SMEs: IPR infringement is associated with higher risk of market exit in comparison to average SME. This risk is particularly elevated for the most vulnerable, independent SMEs that cannot rely on the expertise or financial help of a parent company. The data did not allow us however to confirm that this lower survival risk for infringed trademark or design owners is different from survival risks of trademark or design owners that did not experience infringement.

Results are clearer in case of patent infringement. Patent owners that suffered from patent infringement have lower odds of survival both in comparison to the average SME as well as to the average patent owner that did not suffer from infringement. The lower odds of survival of infringed patent owners may be related to the high level of investment needed to develop and protect new patented technologies. Infringement of such patents may damage the entire business model of smaller firms.

The analysis presented in this chapter is not without limitations. The most salient of these are as follows.

First, the information about the infringement suffered was self-reported. Our dataset may include cases where the respondents’ belief about infringements suffered might not be confirmed by an objective assessment, such as a judge’s verdict.

Second, the responses in the survey do not allow the exact economic impact of the infringement to be assessed. The impact of the use of a trademark that may be similar to one already registered by an SME may be quite different from the infringement of a vital patent protecting a novel technology or the counterfeiting of a successful new line of products introduced by an SME.

Third, the assessment of the relationship between IPR infringement and survival relies on cross-sectional data from the 2016 SME Scoreboard. This information reflects their infringement status as of 2015. Some firms that were not aware of infringements of their IPR at the time of the survey, or that suffered infringement in subsequent years, may be treated as being unaffected by infringements. This may introduce biases into the analysis, most likely underestimating the relationship between infringement and survival odds.

Fourth, the main focus of the present analysis was a relationship between IPR infringement and the most serious outcome of IPR infringement, namely survival of the firm. Results of the successive SME scoreboard analyses show that infringement may be correlated with other negative consequences affecting performance of SMEs, while not necessarily leading to their demise. Future analyses, focusing on other potential negative aspects related to IPR infringement may shine more light on those complex relationships.

Finally, information in Orbis about firms’ current status may not always be up to date. There are cases of firms that suddenly stop reporting their turnover and/or employment but are still recorded as active. Information about the cessation of activities may be reported to the business register after some delay. Some firms may stay dormant for many years before they officially dissolve.