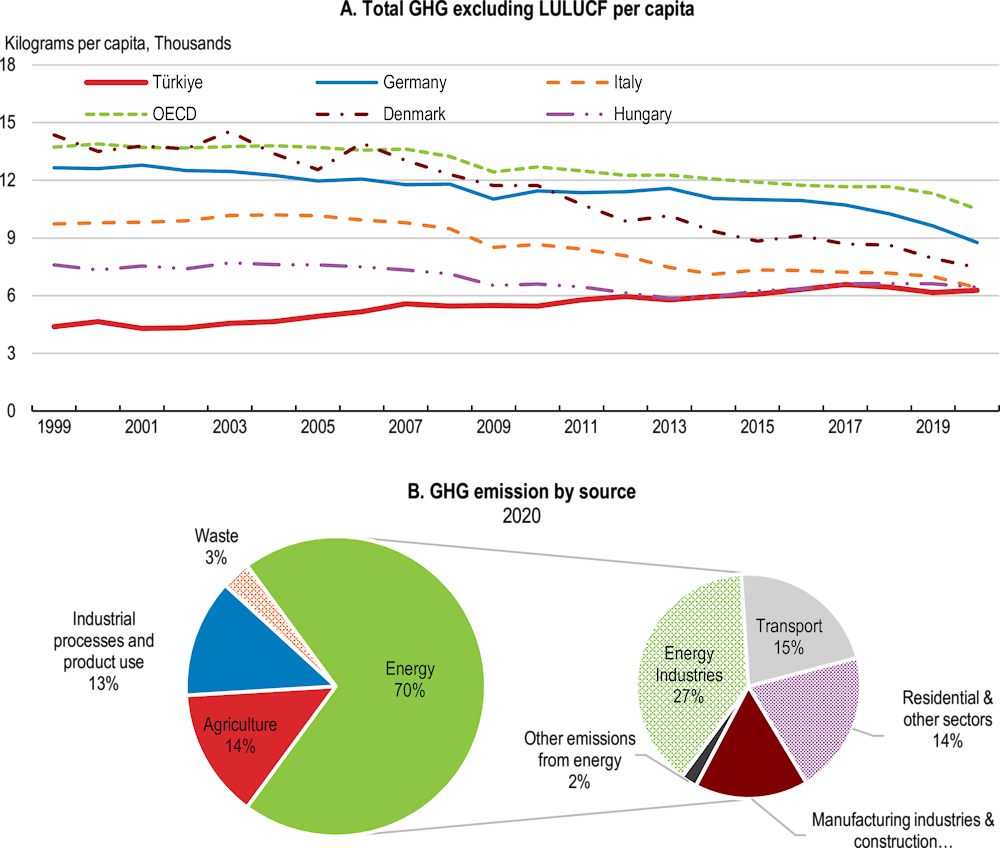

Türkiye has been one of the fastest growing economies in the OECD over the past two decades. GDP per capita rose at an average annual rate of 6% between 2000 and 2021, the poverty rate was cut in half and the share of people participating in the labour market increased by 10 percentage points. Income per capita has converged relatively quickly towards the level in advanced economies, although progress has stalled in recent years (Figure 1.1).

OECD Economic Surveys: Türkiye 2023

1. Key policy insights

Making the economy more resilient will require ambitious reforms

Figure 1.1. Income convergence has been fast, but has stalled in recent years

Convergence in GDP per capita to OECD level

Note: Data on GDP per capita is expressed in USD (current prices and PPPs).

Source: OECD (2022), OECD Productivity database.

The driving force behind economic convergence has been the highly dynamic private sector, which has seized new opportunities in international markets. Labour reallocation towards the services sector has been a key feature. At the same time, the manufacturing sector has become better integrated into global value chains. Türkiye’s exports now account for more than 1% of the world demand for goods and services.

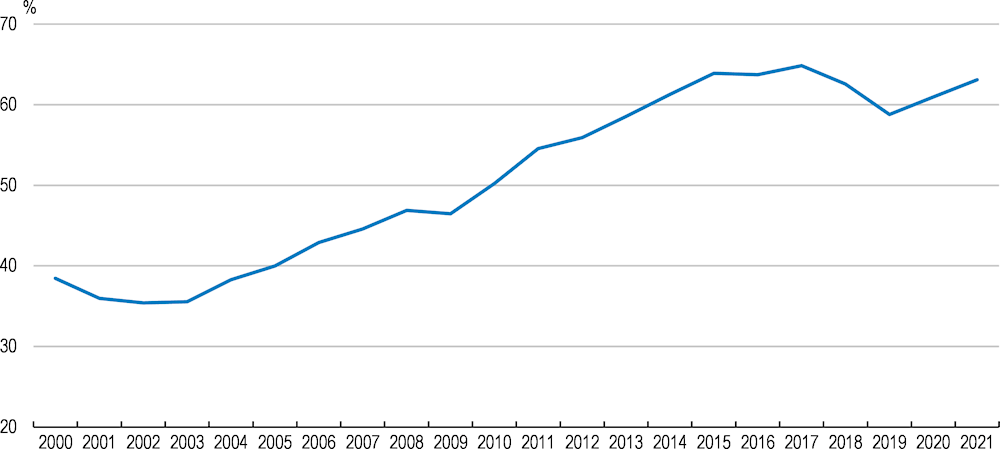

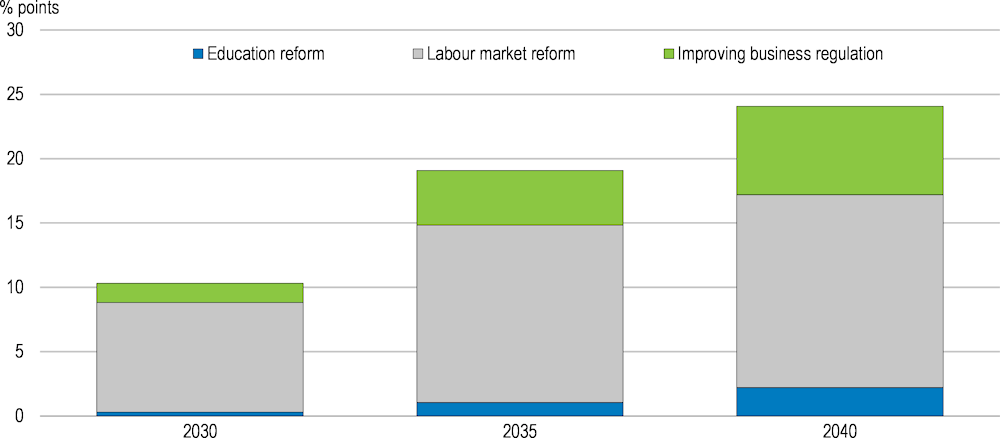

Türkiye’s economy also benefits from a young and dynamic population. While the median age in the average OECD country is 40, Türkiye boasts one of the youngest populations, with a median age of 33. Two thirds of the Turkish population is of working age (15-64) and less than a tenth is above 65. Yet, this “demographic dividend” will gradually decline, slowing future potential growth (Figure 1.2). This underlines the need to better leverage existing human resources, in particular youth and women, whose labour participation is low (Chapter 2).

Figure 1.2. The demographic dividend is declining, weighing on potential growth

Contributions to potential output growth per capita

Source: OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), for further information see Annex in Y. Guillemette D. (2021)[149].

Economic vulnerabilities have intensified in recent years and the risk of macroeconomic instability has increased. In 2022, average annual consumer price inflation reached 72.3% for the first time since 1998, while the lira has lost more than half of its value relative to the US dollar since the beginning of 2021. Inward foreign direct investment flows have stagnated and, as a share of GDP, are the lowest among OECD countries. The current account deficit has widened and is expected to reach 5½ per cent of GDP in 2022. In July 2022, foreign exchange reserves fell to one of the lowest levels in the past decade but they subsequently recovered somewhat. Public sector contingent liabilities have increased, including from the savings guarantee scheme for those converting their foreign currency deposits into lira deposits.

These vulnerabilities are making the economy less resilient to shocks. The country experienced four recessions during the past 25 years and the volatility in economic growth, measured by the standard deviation of annual GDP growth, was four times higher than on average in the OECD. High economic volatility increases uncertainty, deters investment, and can drag down trend growth (Bloom et al., 2012[1]; Ramey and Ramey, 1995[2]) thus putting Türkiye’s efforts to reach high-income status at risk.

To make the economy more resilient, it will be essential to equip young people with the skills to adapt to changing labour market needs. Learning outcomes of Turkish students are low by international standards and adults tend to lack adequate problem solving and information processing skills. Many young people, especially women, are neither employed nor in education or training.

Economic resilience could be strengthened by making the regulatory framework more predictable and flexible. Strict product and labour market regulations contribute to a dual economy with a large informal and semi-formal sector coexisting with large companies, mostly conglomerates. Strict regulations limit the entry of new firms, shielding incumbents from internal and external competition. Ensuring a rules-based, level-playing field for firms requires enforcing rules without exemptions.

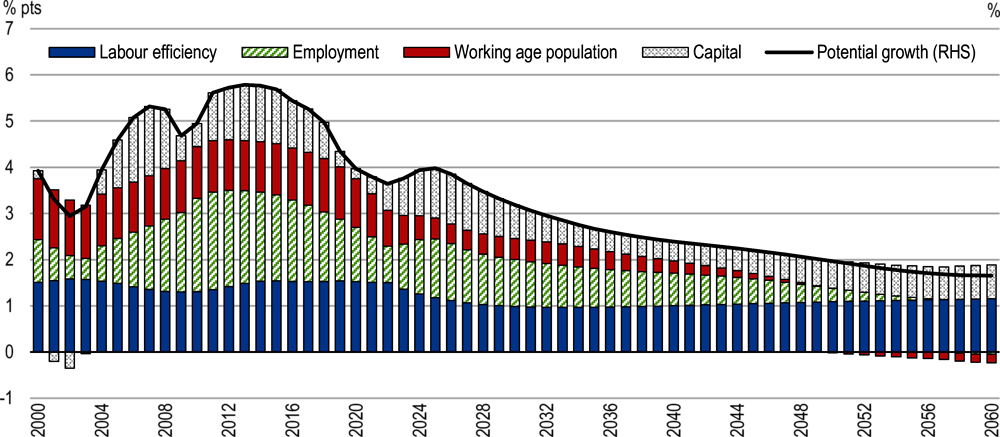

Reforms in these areas have significant potential to address Türkiye’s vulnerabilities, reduce economic volatility and improve living standards. Simulations based on the OECD long-term growth model (Guillemette and Turner, 2018[3]) suggest that an ambitious reform package that would strengthen Türkiye’s regulatory framework and improve educational outcomes could boost GDP per capita by more than 10% by 2030 (Figure 1.3). This reform package would help Türkiye’s economy resume its convergence process towards other OECD countries.

Figure 1.3. Structural reforms can help increase standards of living and make growth sustainable

Cumulative difference from baseline GDP per capita (no policy change) scenario, by policy area

1) Education reform: improving the PISA score to the OECD average 2) Labour market reforms: reducing the gap vis-à-vis the OECD in labour market participation by half 3) Improving business regulations: improvement of PMR indicator to the OECD average.

Source: OECD simulations based on OECD Economics Department Long-term Model.

Against this background, the main messages of this Survey are:

1. Anchoring inflation expectations is key to promote investment and growth. To this end, domestic and international confidence in the independence of the central bank needs to improve, including by reducing the turnover of the Bank’s board. Monetary policy should be tightened. Policy rate increases should be timed carefully and accompanied by clear communication about future moves. The primary fiscal balance surplus should be restored and a medium-term strategy is called for to prepare for long-run fiscal challenges.

2. Strengthening the country’s resilience to shocks and structural change will require a conducive business climate and improved rule of law that enable resources to flow to the most promising activities and firms. Increasing labour force participation and employment of women should be a priority. Equipping the population with the right skills is also important (see Chapter 2).

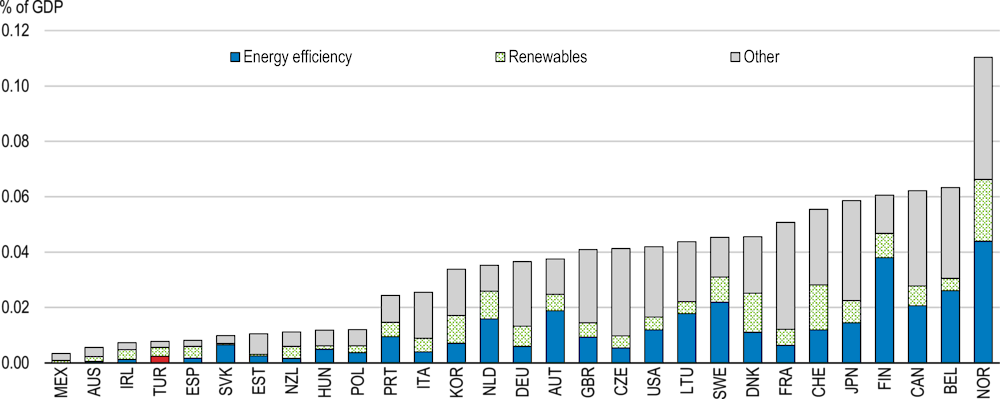

3. The economy will also need to become more resilient to climate change and energy shocks, through adaptation policies, a greening of the energy mix and improvements in energy efficiency.

The recovery from the pandemic was robust, but risks have intensified

The economy is set to slow

Türkiye is one of the world’s very few countries that avoided an annual economic contraction in 2020 in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic (Box 1.1). Strong base effects after the slowdown in 2019, coupled with buoyant consumer spending and unusually robust exports, helped the country to mark one of the fastest recoveries among OECD countries (Figure 1.4, Panel A). The economy expanded by 11.4% in 2021, the fastest growth in the past five decades, and by 6.2% in the first three quarters of 2022 (year-on-year).

Figure 1.4. Türkiye has experienced a strong economic recovery

Private consumption has been the main driver of economic growth (Figure 1.4, Panel B). Real household consumption grew by an astonishing 15.3% in 2021, the highest growth in Türkiye’s history. Pent-up demand during lockdowns supported household consumption in the recovery phase. The rise in inflation also led some households to frontload their purchases, in particular of durable and semi-durable goods. At the same time, measures to facilitate access to credit adopted during the pandemic coupled with low interest rates have contributed to high demand for loans.

Consumer spending has also been supported by labour market developments, with employment and participation rates rapidly recovering to pre-pandemic levels. Türkiye’s employment gains following the pandemic have been the strongest in the OECD area. The services sector, which was hit hard during the pandemic, was responsible for more than half the employment gains during the recovery. Many people have returned to the labour market, particularly young people and women, whose labour force participation now exceeds pre-pandemic levels. Large employment gains have been coupled with significant wage increases. The minimum wage has been raised four times since 2021, by 20% in January 2021, 50% in January 2022, 30% in July 2022 and a further 55% in January 2023 – around 65% of workers in formal employment earn wages in the vicinity of the official minimum wage. Despite labour market recovery, the unemployment rate and labour force participation remain well below the OECD average and informal employment remains widespread (see Chapter 2).

The contribution of gross investment to GDP growth has been negative since 2021, mainly due to the depletion of inventories (Figure 1.4, Panel B). Although manufacturing investment increased somewhat, investment in construction has deteriorated, and foreign direct investment has been weak due to elevated uncertainty.

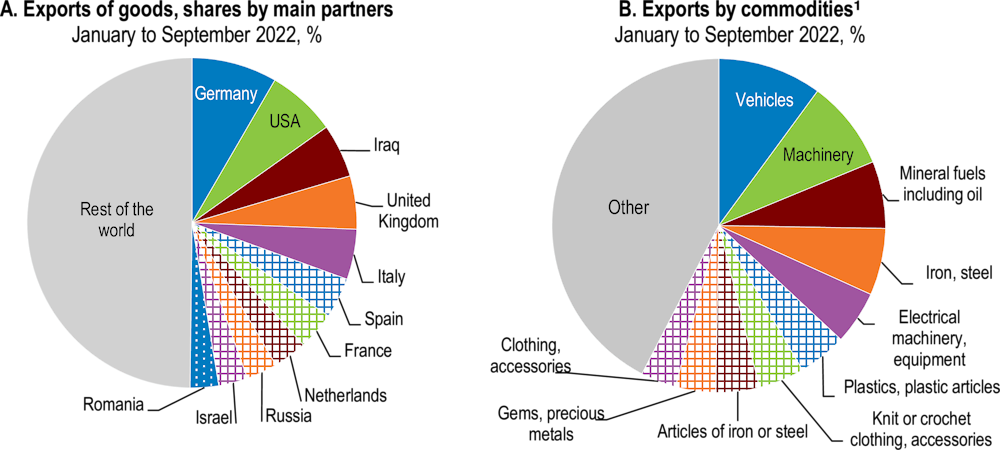

Exports have been a key driver of growth. In 2021, exports of goods and services increased by nearly 25% in real terms owing to the depreciation of the lira along with supply chain disruptions in other countries. Turkish exporters have been able to exploit opportunities from the Asian supply chain disruptions, benefitting from the country’s shorter distance to Europe. Empirical evidence suggests that a 10 percentage point decrease in shipping reliability globally boosts Türkiye’s exports by approximately 5% (World Bank, 2022a). Export growth has been broad-based across exported products.

Activating unused productive capacities has been instrumental to the export expansion. Existing product lines have driven most of the expansion, while the contribution of new markets or new product lines has been smaller (CBRT, 2022[4]). Exports of goods have increased mainly to EU countries and the United States, which are Türkiye’s main trading partners (Figure 1.5). Türkiye has increased its market share in the European Union for textile and clothing, agricultural, plastic and wood products, which typically do not require additional large investments (World Bank, 2022[5]). In recent months, exports to Russia have also increased significantly, but their share remains low (around 3%).

Figure 1.5. Exports by trading partner and by commodity

1. Based on the two-digit Harmonized System.

Source: Turkstat, "Foreign Trade Statistics, September 2022".

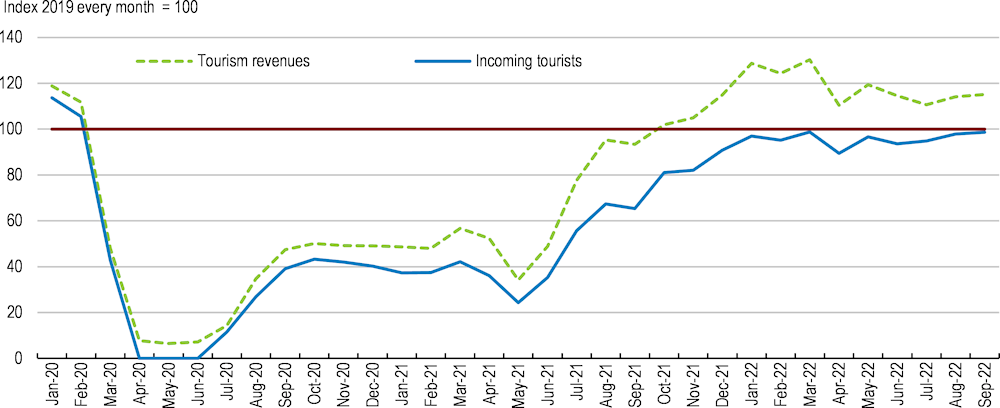

Exports of services, particularly tourism, have rebounded to their pre-pandemic levels. The tourism sector, brought to a standstill by globally-applied restrictions during the pandemic, has recovered in 2022 despite geopolitical tensions. Revenue, as well as the number of tourists, have returned to their pre-pandemic levels (Figure 1.6). The number of Russian tourists, which accounted for the largest group visiting Türkiye in previous years, has decreased by more than a third in the first nine months of 2022 compared to 2019. But this was compensated by the increasing number of tourists from European countries. Aided by the depreciation of the lira, Türkiye has become an even more attractive destination for European tourists (World Bank, 2022[5]).

Figure 1.6. The tourism sector has recovered

Note: Data from January 2020 are based on the corresponding monthly data in 2019.

Source: Turkstat, "Tourism income, number of visitors and average expenditure per capita by months, 2012 - 2022".

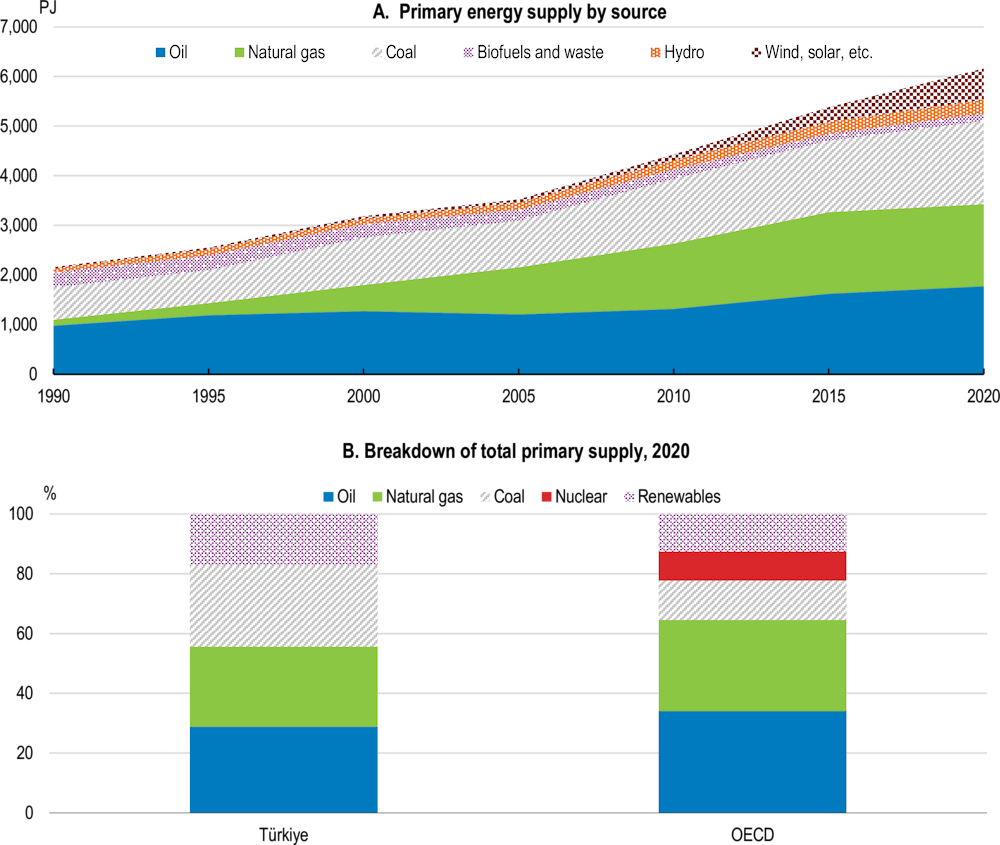

In contrast, imports of goods and services have been subdued, increasing by only 2.4% in real terms in 2021, partly due to the depreciation of the lira. Imports of capital goods have been weak reflecting limited investment activity and elevated uncertainty. Russia has remained the main trading partner in terms of imports, accounting for nearly 17% of all imports in the first 10 months of 2022 (up from 11% in 2021) -- Türkiye has not imposed sanctions on Russia after the start of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Despite some progress in terms of energy security (see below), Türkiye remains heavily dependent on imports: 93% of oil consumption and 99% of gas consumption are imported.

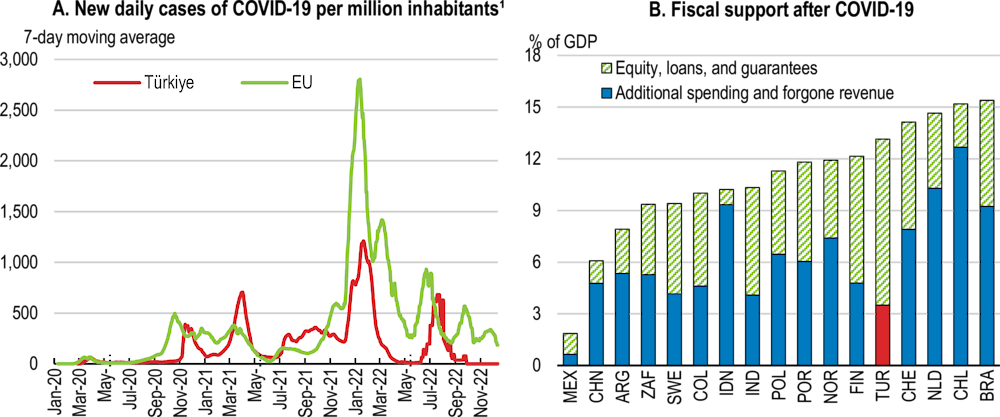

Box 1.1. Türkiye’s response to the Covid pandemic

The last infectious wave peaked during summer 2022 (Figure 1.7, Panel A), but there have been far fewer casualties than in previous waves, thanks to the wide vaccination rollout. As of October 2022, 63% of the population had been fully vaccinated. This represents about 86% of the population over 18 years. The vaccination rate among adults is slightly higher than the EU average (83.5%). In terms of health outcomes, Türkiye has been less affected by the pandemic than high-income countries (Wang, 2022[6]).

The pandemic caused a 10.3% fall in real GDP in the second quarter of 2020, but the economy recovered strongly in the third quarter. Informal workers and the tourism sector were hit particularly hard. To mitigate the social and economic impacts, Türkiye provided relatively generous fiscal support. The total fiscal package amounted to 13% of GDP (Figure 1.7), mostly consisting of concessional credits to households, businesses loans and guarantees schemes (OECD, 2021[7]).

Figure 1.7. The Covid-19 crisis in Türkiye

1. The last data point refer to 31 December 2022.

Source: Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org; and IMF (2021), Fiscal Monitor Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic, October.

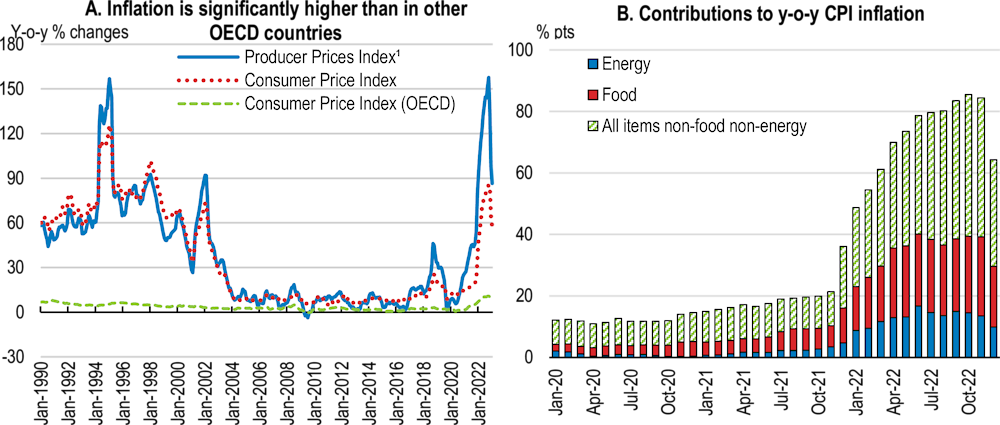

Strong domestic demand, supported by low interest rates, and the surge in global commodity prices have pushed inflation to the highest levels in the OECD area. Moreover, lira depreciation has put pressure on import prices. In 2022, consumer price inflation reached 72.3%. Producer prices were up by 128%, the highest rate in almost 30 years (Figure 1.8, Panel A). The large difference is explained by high energy and import prices, which have more strongly affected producer prices. The sharp rise in energy and other commodity prices - triggered by the pandemic and subsequently the war in Ukraine – contributed significantly to overall CPI inflation (Figure 1.8 Panel B). Inflation pressures are however becoming broad-based, as revealed by the sharp increase in consumer prices for non-food and energy items (Figure 1.8, Panel B).

Inflation is having a particularly negative effect on vulnerable groups. Households in the first decile allocate nearly 70% of their budget to food and housing, twice as much as the corresponding share for a typical household in the upper decile (World Bank, 2021[8]). Recent hikes in minimum wages have brought real wage growth into positive territory, but only in the short term as strong monthly inflation growth will quickly deplete these real income gains.

Figure 1.8. Inflation has soared

1. Producer price index refers to domestic industrial activities.

Source: OECD (2022), OECD Monthly Economic Indicators (database); Turkstat; and OECD Consumer Prices (database).

Economic growth is projected to slow over the next two years (Table 1.1). Monetary policy will remain supportive with the main policy rate being highly negative in real terms. However, weak external demand and persistent geopolitical uncertainties will weigh on investment and limit export growth. Indeed, leading indicators – such as electricity production – already signal a gradual moderation of economic momentum. Very high and persistent inflation will curtail household purchasing power while heightened uncertainty will weigh on investment. Inflation is projected to decline somewhat due to base effects but to remain above 40% over the projection period, reflecting a gradual pass-through of the recent lira depreciation, plus higher producer prices and wage increases, to consumer prices.

Table 1.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2009 prices)

|

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

Projections |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Current prices (TRY billion) |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP)¹ |

3,758.8 |

0.8 |

1.9 |

11.4 |

5.3 |

3.0 |

3.4 |

|

Private consumption |

2,111.9 |

1.6 |

3.0 |

15.7 |

15.2 |

4.1 |

3.4 |

|

Government consumption |

552.0 |

4.0 |

2.2 |

2.7 |

0.2 |

3.0 |

2.3 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

1,115.0 |

-12.4 |

7.3 |

7.4 |

2.8 |

2.8 |

3.8 |

|

Stockbuilding² |

-10.7 |

0.1 |

4.5 |

-7.0 |

-6.4 |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

3,768.1 |

-2.1 |

8.7 |

4.1 |

2.2 |

3.1 |

3.3 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

1,171.0 |

4.6 |

-14.6 |

24.9 |

12.2 |

4.4 |

4.2 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

1,180.3 |

-5.4 |

7.1 |

2.4 |

4.2 |

4.8 |

3.6 |

|

Net exports² |

-9.3 |

3.1 |

-6.9 |

6.4 |

2.8 |

-0.3 |

0.1 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

|

|

|||||

|

GDP deflator |

|

13.8 |

14.9 |

29.0 |

91.7 |

51.1 |

46.1 |

|

Consumer price index |

|

15.2 |

12.3 |

19.6 |

72.3 |

44.6 |

42.1 |

|

Core inflation index3 |

|

13.4 |

11.2 |

18.3 |

58.6 |

45.6 |

42.1 |

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

|

13.7 |

13.1 |

12.0 |

10.7 |

10.3 |

10.0 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

|

0.7 |

-5.0 |

-1.7 |

-5.6 |

-3.8 |

-2.5 |

|

General government fiscal balance (% of GDP)4 |

-4.8 |

-5.1 |

-3.9 |

||||

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP)4 |

32.6 |

39.7 |

41.8 |

||||

1. Based on working-day adjusted series.

2. Contribution to changes in GDP. Stock building includes statistical discrepancy.

3. Consumer price index excluding energy, food, non-alcoholic beverages, alcohol, tobacco and gold.

4. OECD projections do not cover the fiscal account due to the absence of a unified national general government accounting system. IMF Fiscal Monitoring Reports are used to evaluate Türkiye’s fiscal position.

Source: OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); and forthcoming OECD Economic Outlook 112 database.

Risks have intensified

Risks are unusually high and tilted to the downside. The adverse effects of the war on prices and economic activity could become much greater. Commodity prices could increase, adding pressures on inflation as Türkiye is heavily dependent on imported oil and gas. Moreover, higher costs arising from shortages of critical raw materials, or further disruptions to transportation and trade could have sizable negative effects on the economy. A complete cessation of energy exports from Russia to Europe could significantly affect Türkiye’s main trading partners and thus weigh on exports (Table 1.2).

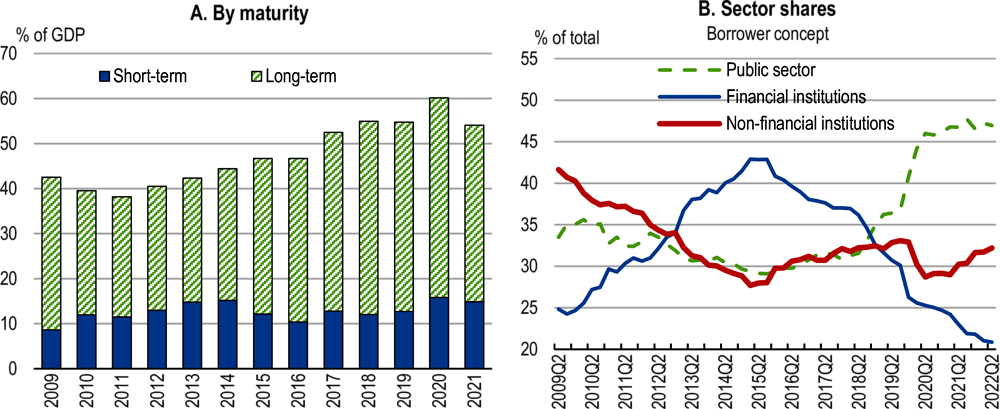

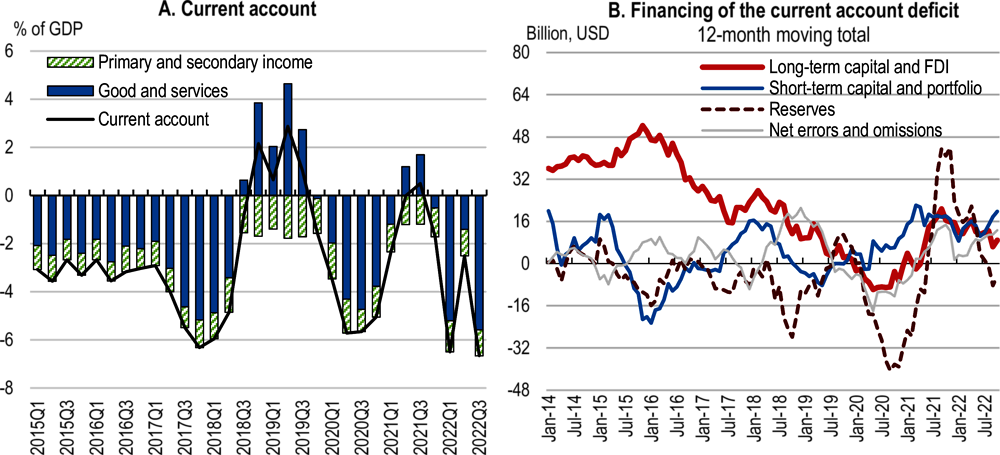

The current account deficit poses a risk (Box 1.2). It widened at the beginning of 2022, reflecting the surge in global energy and commodity prices and the depreciation of the lira (Figure 1.9, Panel A). It is projected to reach 5½ per cent of GDP in 2022, the highest deficit in almost a decade, despite strong tourism receipts over the summer. Moreover, its funding has shifted from relatively stable sources to more volatile ones since the mid-2010s (Figure 1.9, Panel B). Foreign direct investment inflows have remained well below their early 2010s level. Sales of foreign reserves financed a large part of the current account deficit up to the start of 2021. From 2021, foreign currency inflows of unknown origin, classified as “net errors and omissions” and which typically capture movements in Turkish savings from abroad, have played a growing role, covering approximately a third of Türkiye’s current account deficit in the first half of 2022.

Figure 1.9. The external position has weakened

Note: In Panel B, short-term capital movements include short-term net loans of banking and real sector and bank deposits. Long-term capital movements consist of long-term net loans of banking and real sector and the bonds issued by banks and the Treasury to abroad. Positive reserves mean an increase in reserves. Positive net errors and omissions mean foreign exchange (FX) entrance.

Source: OECD calculations based on CBRT; and OECD (2022), Balance of Payments (database).

Türkiye has large external financing needs. As of October 2022, external debt maturing within a year stood at USD 186 billion, corresponding to approximately 20% of GDP. Short-term external debt has increased since 2009 (Figure 1.10). Debt refinancing measured by the external debt rollover ratio has remained high, suggesting that companies have retained access to external finance (World Bank, 2022[5]; CBRT, 2022[9]). Still, they could face a refinancing risk were market sentiment to deteriorate. Public sector external debt has also increased in recent years (Figure 1.10, Panel B). Gross reserves cover around 60% only of short-term external debt on a remaining maturity basis. Moreover, the bulk of the short-term debt stock is denominated in foreign currencies. Further swings in the lira exchange rate could affect both the private and public sectors, making debt service payments in lira terms costly and unpredictable.

Figure 1.10. External debt has increased over the past decade

Box 1.2. Türkiye’s financial turmoil in 2018

In 2018, financial conditions in advanced countries had started to tighten after a prolonged period of extremely accommodative monetary policy with negative effects on capital flows to emerging markets. Moreover, risk perceptions towards these markets had further increased due to rising trade policy uncertainty and a slowdown in global trade. In the summer of 2018, portfolio investment to emerging markets slowed significantly and bond yields in these countries increased, reflecting higher risk premia.

Prior to the worsening of the global economic environment in 2018, Türkiye’s external vulnerabilities were increasing. The current account was widening and reached around 6% of GDP at the beginning of 2018. Corporate debt had increased by 20 percentage points in the course of four years and in 2018 stood at 170% of GDP with around 65% of the debt denominated in foreign currency. External debt was steadily increasing since 2011 and reached 54% of GDP in 2018.

In the summer of 2018, the uncertain global economic environment combined with these vulnerabilities and international tensions led to a lira sell-off and capital outflows. In August 2018, the exchange rate depreciated by nearly 40% in two weeks; the risk premia and long-term interest rates rose strongly. The financial market volatility had significant real sector impacts. The depreciation of the lira increased debt service costs, which strained firms’ liquidity and solvency. The number of bankruptcy protection filings soared. Inflation surged to close to 25% in September 2018 and business and household confidence fell. GDP contracted by 6.4% and 12.2% (annualised) in the third and fourth quarter of 2018 respectively.

Foreign exchange liquidity was released as a response to financial market pressures by cutting banks’ reserve requirements and limiting their engagement in cross-currency swaps. The central bank raised its benchmark policy rate in September by 625 basis points to 24%, which supported the exchange rate and the required economic adjustment. A “Comprehensive Plan Against Inflation” was announced in October 2018, based on administrative price freezes and voluntary private sector price cuts for targeted items of the consumer basket over two months, subsequently accompanied by temporary VAT cuts (OECD, 2018).

Table 1.2. Tail risks that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Vulnerability |

Possible outcomes |

|---|---|

|

Dramatic escalations of the Russian war in Ukraine — expanding to other countries. |

Dramatic decline in demand from the main trading partners would reduce exports, with negative impacts on employment. Uncertainty would curb consumption and business investment. Energy prices could increase further with adverse effects on vulnerable groups. |

|

The emergence of new virus variants could limit the efficacy of vaccines and lockdowns could be introduced again. |

Output, investment and trade growth would be affected. |

|

Inflation could spiral out of control and become entrenched. |

High inflation would further erode household incomes and spending, hitting vulnerable households particularly hard. |

The monetary and financial policy framework needs to be strengthened

Monetary policy needs to be tightened

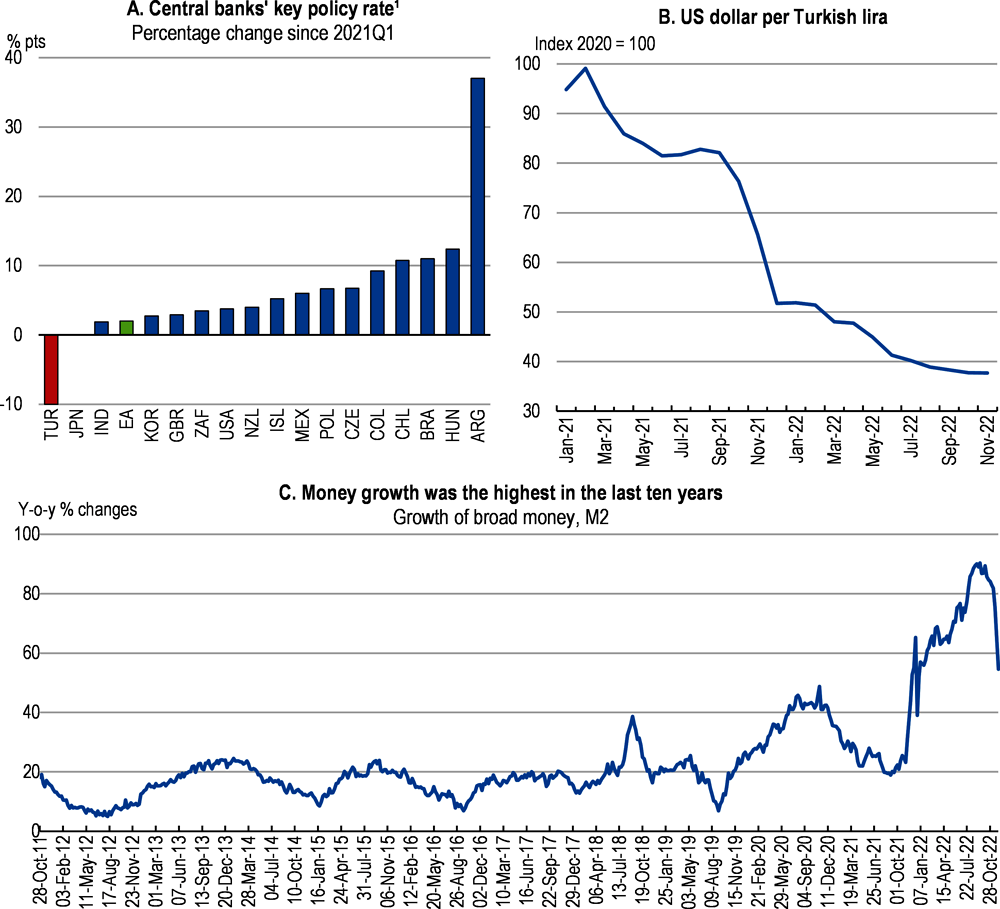

Monetary policy has been accommodative, with credit conditions more favourable to export and industry sectors in line with the new policy frameworks (Box 1.3) and Box 1.4). The Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye (CBRT) has reduced its base rate by 10 percentage points since September 2021 while economic activity was strong, inflation accelerated, and the current account deficit widened. Türkiye is the only OECD country that has cut its policy interest rates since early 2021 (Figure 1.11, Panel A), placing additional pressures on the lira.

Box 1.3. New policy frameworks have been introduced

The Türkiye Economic Model was introduced in December 2021. It aims at increasing export competitiveness and private investment, while reducing the current account deficit permanently This Model prioritizes investment, employment, production and exports, aiming a healthy current account balance by providing low-cost accessible loans to productive and export sectors and controlling inflationary demand pressures through macroprudential measures. The primary objective of the Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye (CBRT) is to achieve and maintain price stability. The “liraisation strategy” is a key and new element to reduce external pressures on prices and strengthen the effectiveness of monetary policy. Announced in December 2021 by the Monetary Policy Committee, it places the Turkish lira at the core of monetary and financial policies. According to the CBRT, this approach is tailored to meet the specific needs of the Turkish economy and address its vulnerabilities, in particular the high level of dollarisation and the persistent current account deficit which reduce monetary policy effectiveness.

With the liraisation strategy, the CBRT is relying on a lira deposit saving scheme with an exchange rate guarantee, collateral diversification, and liquidity management regulations (see below) to strengthen the demand for liras and direct loans to productive and exporting sectors, by foregoing reserve requirements for exporters, investors and SMEs. According to the CBRT, low interest rates targeted to productive sectors mitigate cost pressures, and thus inflation, and increase the economy’s growth potential. This, combined by tighter financial conditions for consumer loans, is expected to reduce the current account deficit.

Various policy measures and tools are used to support the liraisation strategy and increase international reserves:

A foreign exchange-protected deposits and participation accounts scheme (KKM). This scheme compensates savers for potential exchange rate losses (Box 1.6).

A new differentiated reserve-requirement scheme. The CBRT imposes security based reserve requirements on TL denominated commercial loans , except for those financing SMEs, exports, investments and agricultural loans. It also applies a higher reserve requirement ratio for banks with excessive credit growth.

The facility of advance loans against investment commitment was announced and has been financed by the CBRT resources. The facility aims to increase exports and investments in the production of import-substitution goods by offering low-interest and long-term (10 year) Turkish lira loans with no principal repayment for two years.

Exporters are required to exchange 40% of their foreign currency revenues into liras.

Figure 1.11. The policy interest rate has been cut and the lira has depreciated

1. The latest data refer to the policy rate on 2 December 2022.

Source: OECD Monthly Monetary and Financial Statistics (MEI); BIS; and CBRT.

Domestic and international confidence in the independence of the CBRT needs to be strengthened. The financing of government debt by the central bank has been marginal and based on the regulatory environment, the degree of independence of the CBRT has been similar to that of many other central banks of OECD countries (Romeli, 2022[10]). However, legislative changes since 2018 have weakened this position (ECB, 2020[11]). Since 2018, the tenure of the central bank’s top management has been shortened, conditions for the removal of the governor eased and the 10 years relevant experience qualification and terms of office of deputy governors were removed. De facto, changes in the central bank’s board members have been frequent, with four changes in governor within a four-year period. Interest policy cuts in the context of persistently high inflation have been interpreted by markets as the result of political interference reducing the independence of the central bank.

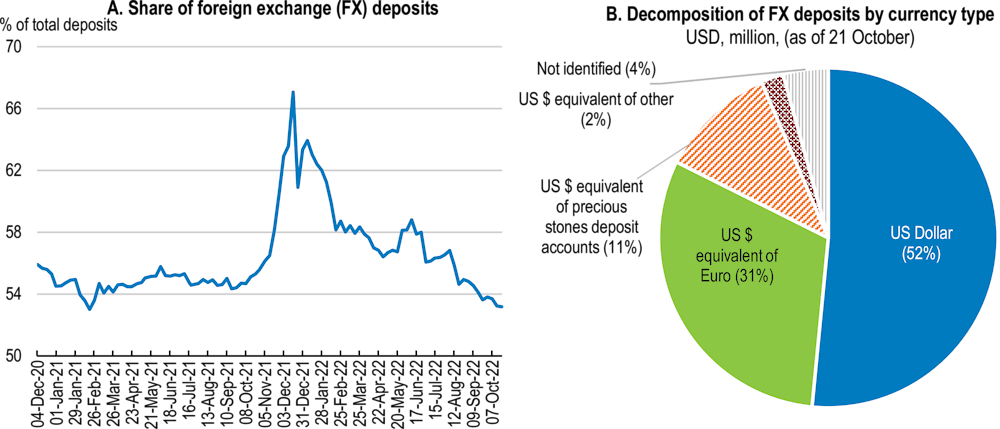

The lira has lost more than half of its value vis-à-vis the US dollar since the beginning of 2021 (Figure 1.11, Panel B). Türkiye’s credit rating was downgraded by all three major agencies in 2022. Inflation expectations suggest that market participants have lost trust that inflation will converge to the 5% central bank’s target. In December 2022, inflation expectations for 12 months ahead stood at 35%. The depreciation of the lira has prompted the population to protect its savings by converting lira deposits into dollars, euros and other hard currencies. By the end of 2021, the share of deposits held in foreign currencies had increased to 68% (Figure 1.13). This put further pressure on the lira and boosted inflation. The difference between the policy interest rate and inflation has risen sharply.

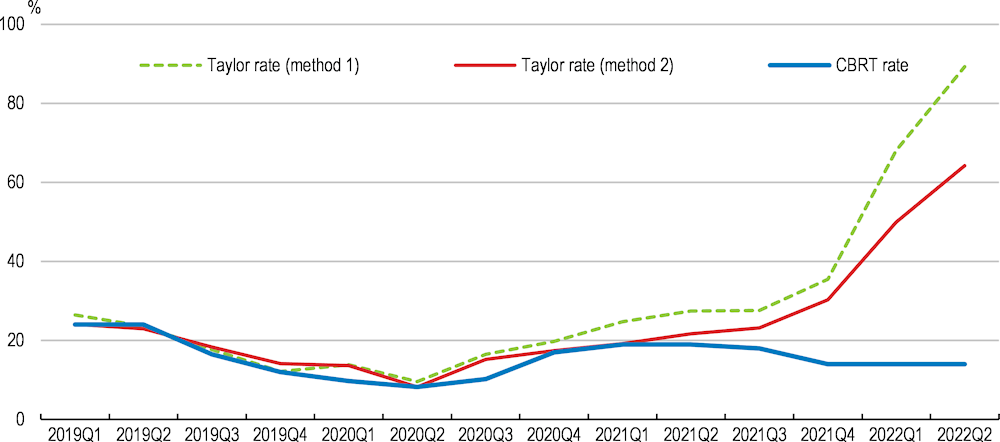

Box 1.4. The Taylor rule benchmark

The Taylor rule provides a simple benchmark to assess the conduct of monetary policy based on a relationship between a central bank’s policy rate, inflation and economic growth (Orphanides, 2007[12]). While the Taylor rule can help policymakers communicate, there are alternative rules to guide monetary policy. Considerations used in the Taylor rule may not be the only relevant ones when taking monetary policy decisions. In particular, it does not account for the sources of inflation.

In Türkiye, the optimal interest rate as suggested by the Taylor rule and the central bank’s main policy rate were very close up to the first quarter of 2021 but have diverged since then (Figure 1.12). In the summer of 2021, when the monetary easing cycle started, inflation was 15 percentage points above the central bank’s target and most output gap estimates suggest that the economy was overheating (CBRT, 2022[4]). Most OECD economies, including the euro area and the United States (EC, 2022[13]), (FED, 2022[14])saw a growing divergence between their inflation target and actual inflation in 2022. This can lead to deviations between Taylor rule estimates and the policy stance. The gap for Türkiye has been larger however.

Figure 1.12. Taylor rule estimated interest rates

Note: The Taylor rule interest rate is calculated as: i = average potential growth + inflation + 0.5 * output gap + 0.5*(inflation – inflation target). Method 1 uses actual inflation while method 2 uses inflation expectations.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); and CBRT.

To reduce the dollarisation of the economy, the authorities have introduced a foreign exchange-protected deposits and participation accounts scheme (KKM), encouraging holders of foreign currencies to convert their funds into liras. The government has committed to compensate savers for any losses if the decline in the exchange rate exceeds the interest rate offered by banks on KKM deposits. For example, if the lira depreciates by 50%, holders of KKM lira deposits would receive the equivalent of a 50% interest payment (banks would pay around 14% plus a compensation by the government of 36%). The authorities have further increased incentives for companies and households to participate in the KKM saving scheme. First, Parliament approved a corporate income tax exemption on companies’ gains resulting from the conversion of foreign currency holdings into liras. Second, banks whose lira deposits make up less than 50% and between 50% and 60% of all deposits will be charged 8% and 3% commission respectively, on foreign exchange required reserves. The KKM scheme was originally set up for one year and was extended to the end of 2023.

Figure 1.13. After a sharp increase, the share of foreign currency deposits has declined

Note: In Panel A, the latest data point refers to 21 October 2022. In Panel B, the category "Not identified" include foreign exchange deposits of resident and non-resident banks.

Source: CBRT.

The introduction of the KKM in December 2021 has helped increase the share of lira deposits and slow the depreciation of the lira, but the budgetary cost may be high. By the end of December 2022, the KKM saving scheme had attracted TRY 1.4 trillion deposits, i.e. around 10.3% of GDP and more than 15% of all banking deposits. The KKM scheme has thus helped reverse dollarisation as the share of deposits held in foreign currency has decreased significantly, returning to the level seen before monetary easing (Figure 1.13). The KKM saving scheme presents some risks, however. Although the lira was relatively stable at the beginning of 2022, it had lost almost one third of its value compared to dollar between January 2022 and October 2022. As a result, the Treasury had paid almost TRY 91.6 billion (0.6% of GDP) to KKM deposit holders as of November 2022. The scheme’s ultimate costs to the Treasury will depend on exchange rate developments and the duration of the scheme. If the lira depreciates further, the scheme’s guarantee could have larger fiscal costs - with further adverse effects on confidence.

The authorities have introduced other measures to strengthen the lira and prop up foreign reserves. Since April 2022, exporters have been required to exchange 40% of their foreign currency revenues into liras. The new housing package introduced in May 2022 offers a cheap mortgage interest rate (0.89% per month) to people willing to convert their foreign currency holdings into liras or transfer their gold to central bank.

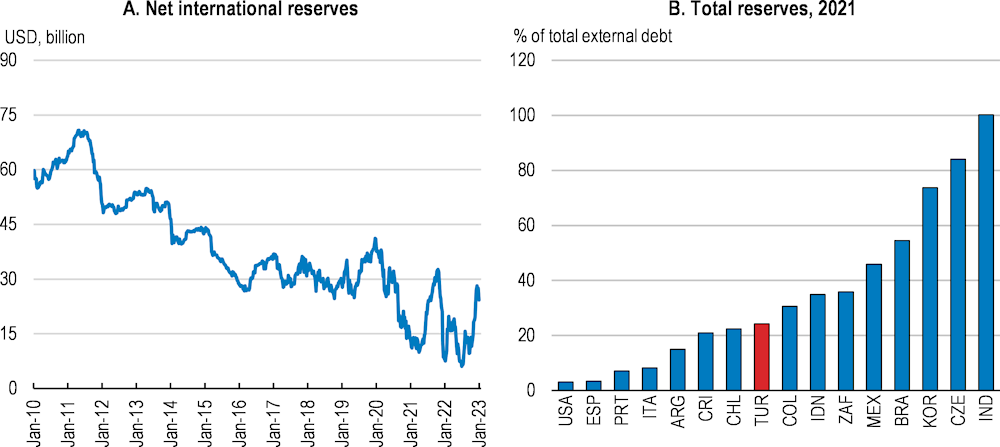

Despite these measures, foreign exchange reserves have shrunk, against the backdrop of market interventions to support the currency. The central bank directly intervened late in 2021 for the first time since 2014. Gross foreign currency reserves – the measure used by the central bank to communicate – recovered somewhat and reached USD 128.8 billion in December 2022, equivalent to around four months of imports. Net reserves - foreign exchange assets minus liabilities - fell in July 2022 to their lowest level in 20 years but recovered somewhat in January to USD 24.3 billion (Figure 1.14, Panel A). Reserves are also low by international standards (Figure 1.14, Panel B) and net reserves excluding short-term swaps (including domestic commercial banks and foreign central banks) are negative. Active communication by the central bank regarding various aspects of its reserve position, including net reserves and swaps, would improve transparency and bolster confidence as recognised in the previous OECD Economic Survey (OECD, 2021[7]).

Figure 1.14. Foreign reserves have decreased

Note: In Panel A, the latest data point refers to 6 January 2023.

Source: CBRT; and IMF, International Financial Statistics.

Domestic and international confidence in the independence of the central bank should be strengthened by extending the tenure and reducing the turnover of the Bank’s board members. The policy rate should be raised to counter inflation and signal the central bank’s firm intention to bring inflation back to target. Credible forward guidance, with clear communication and carefully calibrated tightening, would help re-anchor inflation expectations. Foreign exchange-protected deposits should be gradually phased out.

Table 1.3. Past recommendations and actions taken in monetary policy

|

Recommendations |

Actions taken |

|---|---|

|

Restore the independence of the Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye, including with legislative measures. Maintain the real policy interest rate in positive territory as long as inflation and inflation expectations diverge from official projections and targets. |

The Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye has reduced its base rate by 10 percentage points since September 2021 |

|

Replenish foreign reserves as conditions allow. Communicate actively on the foreign reserve position according to the information needs of financial markets. |

Foreign reserves have declined, but recovered somewhat in the second half of 2022. |

|

Outline and communicate a coherent macroeconomic policy framework encompassing fiscal, quasi-fiscal, monetary and financial policies. |

The authorities have adopted new policy frameworks, with a different approach to monetary policy (Box 1.3 ). |

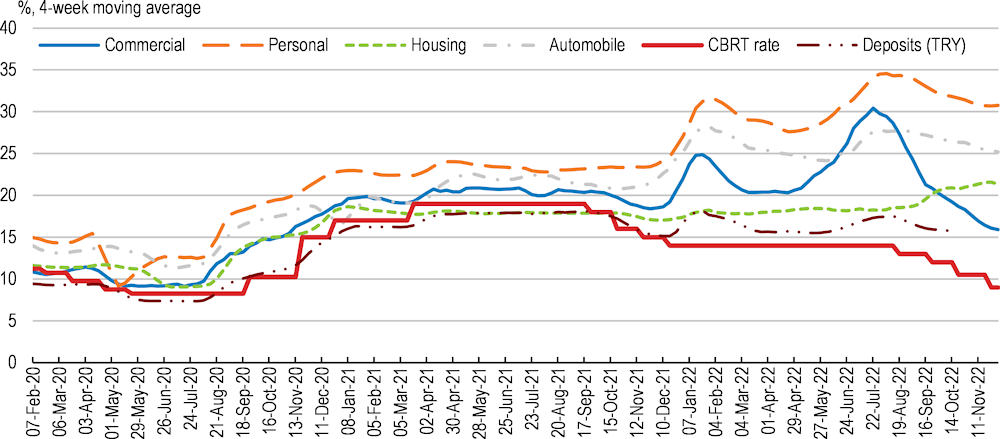

Financial stability risks should be monitored closely

While the authorities have cut the main policy rate, financial conditions for some types of loans have tightened. Since April 2022, macro-prudential policies and collateral measures have been implemented in response to growing macroeconomic imbalances. The 20% reserve requirement for certain lira-denominated commercial loans has been replaced by a 30% securities holding requirement. There are large variations in lending rates across uses (Figure 1.15), in line with the new monetary framework aimed at supporting productive sectors and reducing the current account deficit (Box 1.3). At the same time, some loans are excluded from the reserve requirements such as investment loans, loans to export companies and loans to SMEs.

To strengthen monetary policy transmission and reduce the gap between the central bank’s benchmark rate and the average rate on commercial loans, the central bank introduced measures in August 2022. Banks with interest rates on new loans exceeding the central bank’s benchmark by 1.4 times (or by 1.8 times) now face additional collateral requirements amounting to 20% (or 90%, respectively) of the value of new credits. These measures have helped reduce commercial rates in August 2022 (Figure 1.15).

Figure 1.15. Lending rates have risen despite cuts in the policy rate

Interest rates by types of loans

Note: Commercial loans excludes overdraft accounts and credit cards. The latest data points refer to 2 December 2022.

Source: CBRT.

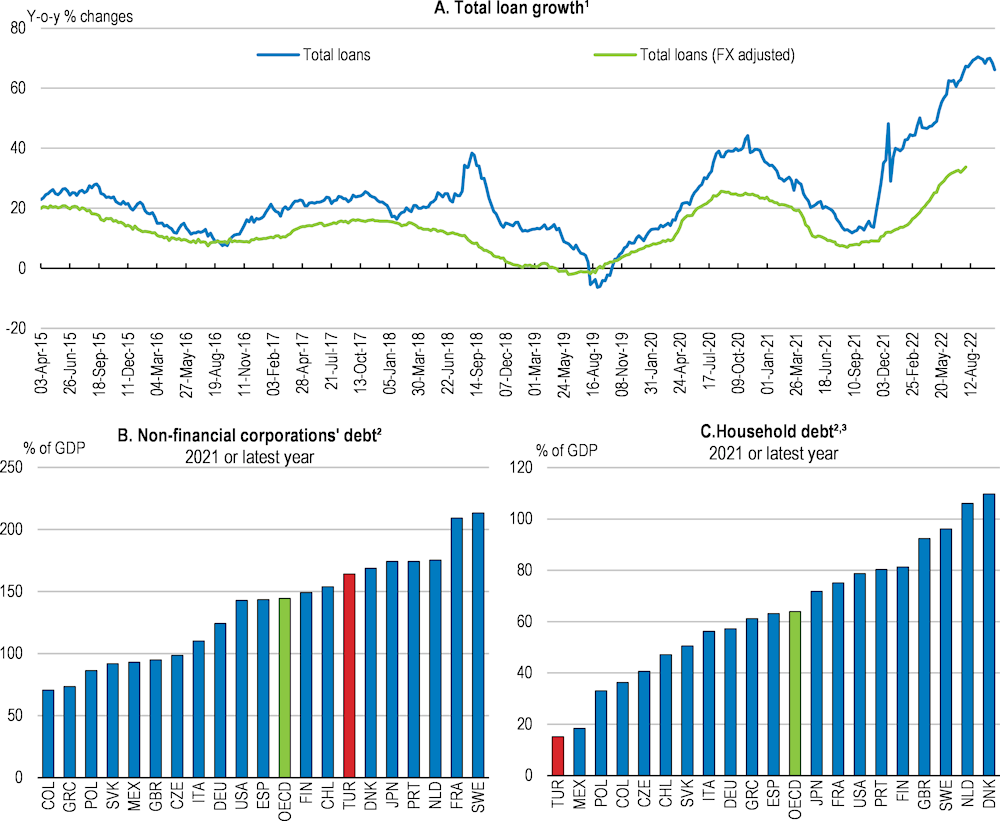

Corporate debt could become a source of fragility as the economy slows. Corporate sector profitability increased significantly in 2021 and in the first half of 2022 due to strong economic activity and demand. However, corporate loans have risen fast and corporate debt stood at 150% of GDP in 2021. The share of corporate debt denominated in foreign currency has declined since 2018 (CBRT, 2022[9]), but still stood at around 60% in the second quarter of 2022, with foreign currency debt largely concentrated among exporters. Overall, the corporate sector’s net position in foreign currency is negative, implying that it is exposed to the risk of a lira depreciation. Between 2017 and 2020, the share of foreign exchange losses in total corporate costs increased due to depreciation (World Bank, 2022[5]). Still, foreign-currency debt of the corporate sector is concentrated among companies that may be in a better position to manage their exposure, most of which are large and natural hedgers.

Financial risks from the household sector remain low as household debt stands at less than 20% of GDP, well below the OECD average (62% of GDP). Household financial assets increased significantly on the back of a strong growth in deposits and the FX protected savings accounts (see above). Household loans denominated in foreign currency are marginal, as Turkish residents with no foreign currency income are generally prohibited from taking foreign currency loans.

Figure 1.16. Loans have grown fast in nominal terms

1. FX adjusted adjust the level of loans due to exchange rate movement. Total banking sector includes participation banks. Non-performing loans are excluded.

2. According to the system of national accounts (SNA), debt is obtained as the sum of the following liability categories: special drawing rights (AF12), currency and deposits (AF2), debt securities (AF3), loans (AF4), insurance, pension, and standardised guarantees (AF6), and other accounts payable (AF8).

3. The household sector includes non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH).

Source: OECD (2022), OECD Financial Dashboard, OECD National Accounts database, OECD Financial Accounts database; BRSA Weekly Bulletin and CBRT.

The banking sector has performed well recently but the worsening economic outlook coupled with increasing macroeconomic vulnerabilities may create challenges. The banking sector has benefitted from the increase in net interest margins. Banks have adjusted up their lending rates to businesses and consumers, while deposit rates have remained low. Rising inflation has also raised their earnings from bonds linked to consumer prices, while strong credit growth has boosted fees. As of November 2022, the banking sector recorded a net profit of TRY 389 billion, a 417% increase compared to the previous year.

The banking sector’s liquidity position is strong. Short and long-term liquidity indicators are above legal lower limits and historical averages (CBRT, 2022[9]). Banking sector capitalisation exceeds regulatory floors. The non-performing loans (NPLs) ratio decreased to 2.4% in August 2022, although this largely reflects the strong growth in new lira loans (i.e. the denominator). The ratio of debt collections of non-performing loans to NPL additions remains strong (CBRT, 2022[9]).

Banks’ asset quality could be affected by worsening economic conditions. Financial stability risks should continue to be monitored by the Financial Stability Committee. In this regard, publishing banking sector stress tests could help strengthen domestic and international confidence. Public banks hold approximately 40% of all deposits in Türkiye and have played a crucial role in efforts to uphold demand during the Covid pandemic using concessional credits to households and businesses. Therefore, their exposure to credit risk has increased. Early this year, the Sovereign Wealth Fund injected TRY 51.5 billion (USD 3.5 billion, 0.4% of GDP of additional capital into six public banks. As mentioned in the previous OECD Economic Survey, competition between public and private banks (including banks’ financing) should be closely examined in light of international good practices (OECD, 2021[7]).

Table 1.4. Past recommendations and actions taken in financial policies

|

Recommendations |

Actions taken |

|---|---|

|

Re-evaluate and reduce the weight of government-owned financial institutions. Maintain a neutral framework for banks’ credit allocation decisions. |

The share of state-owned banks in total banks’ assets declined from 47.5% to 46.3% and in total loans from 45.3% to 43.7%. |

|

The authorities should communicate on how they evaluate and address the risks of deterioration in banks’ asset quality. The results of the stress tests of individual banks and of the banking system as a whole should be disclosed to the public. |

The Financial Sector Evaluation Programme (FSAP), including stress tests for banks, will be completed at the end of 2022. |

Fiscal policy should become more prudent

The headline deficit has declined but contingent liabilities are increasing

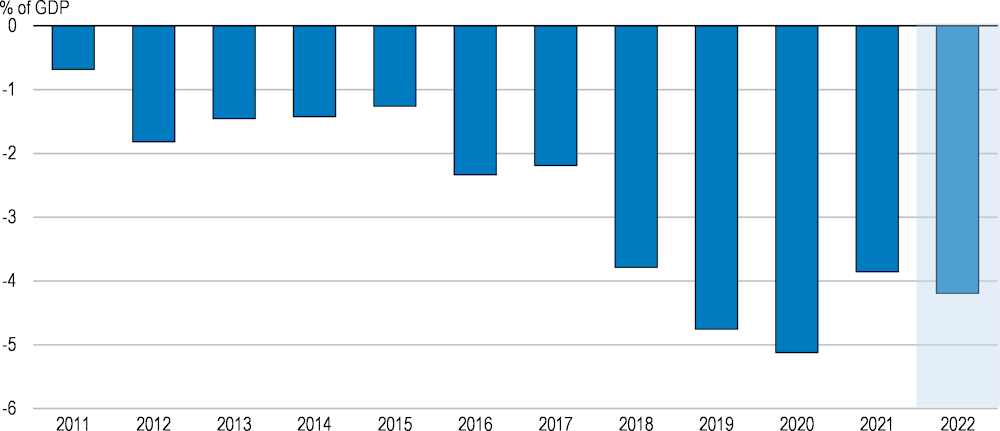

Prudent fiscal policy has been an important policy anchor over the past two decades in Türkiye. The fiscal deficit increased in 2020, partly due to the pandemic response (Figure 1.17). The fiscal stimulus package to mitigate the socio-economic impact of the pandemic, although smaller than in other OECD countries, amounted to nearly 4% of GDP (IMF, 2021[15]).

Figure 1.17. The fiscal position has weakened over the past decade

Headline fiscal deficit

Note: Projected data in 2022.

Source: IMF (2022), World Economic Outlook Database, October.

Tax revenues have grown strongly in recent years, by nearly 40% in 2021 and by 108% in the first half of 2022. These outcomes have been driven by the strong economic rebound, but also by higher-than-expected inflation since taxes due are calculated based on nominal incomes. Revenues from a tax restructuring and improved tax collection have also played a role.

Despite strong tax revenues, the deficit is expected to worsen somewhat in 2022, to 4.2% of GDP (Figure 1.17). Evidence from other countries confirms that higher inflation leads initially to higher tax revenues, while spending pressures typically rise over time (IMF, 2021[16]). Indeed, in Türkiye current expenditures are increasing much faster than budgeted, particularly wages and transfers. Public wages have increased by an 30%, while family benefits and pensions (including the minimum pension) have all been adjusted to compensate for the surge in inflation. In 2022, the government also introduced several measures to shield citizens from high energy and food prices (Box 1.5).

The government should address the adverse distributional impacts of higher energy prices but avoid jeopardising fiscal sustainability. Energy users have few options for cutting demand dramatically in the very short run. Thus, energy price increases have significant adverse effects on households and businesses. Türkiye’s support measures to households include non-targeted price support measures, such as tax cuts on energy (Box 1.5). Evidence from other countries shows that such measures do not allow demand to adjust to supply constraints, which could exacerbate commodity shortages and sustain future inflation (Vaitilingam, 2022[17]; OECD, 2022[18]; Neely, 2022[19]). Tax reductions also weaken price signals, and thus incentives to reduce consumption. Moreover, their budgetary cost can be high over time (OECD, 2022[18]). Instead, targeted income support measures should be used as they allow for a more sustainable policy response if high prices persist.

Box 1.5. Measures to shield households from high energy prices

In 2022, the authorities have implemented several measures to cushion households from the impact of energy price inflation, amounting to a total of 0.6% of GDP, including:

1. Two electricity fees have been abolished: (i) the TRT (state-run broadcaster) payment and (ii) the Energy Fund payment. The removal of these fixed electricity fees reduced the electricity bill for households by 2.7%, at an expected cost of around TRY 2.5 billion (0.02% of GDP).

2. For all households, the government pays 50% of the electricity bills and 75% of the natural gas bill. Vulnerable households receive additional transfers ranging from TRY 900 to 2 500 twice a year. For households including individuals suffering from chronic diseases or sustained by life support devices, a further 5 p.p. will be added to the subsidy. The expected cost will be approximately TRY 10 billion.

3. Türkiye has adjusted electricity tariffs for low-consumption households by increasing the monthly limit, from 150 kWh to 240kWh, below which electricity is cheaper. Below a monthly consumption of 240 kilowatt-hours, electricity is paid at TRY 1.21 per kilowatt-hour, and above at TRY 1.97 per kilowatt-hour.

4. The VAT rate on electricity used in residences and agricultural irrigation has been lowered from 18% to 8%, at an expected cost of around TRY 9 billion (0.06% of GDP).

Contingent liabilities have inflated public spending and there are risks that costs increase further. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) are one of Türkiye’s main contingent liabilities. Türkiye is the largest PPP market in Europe and is one of the leading countries relying on PPPs for the provision of infrastructure such as airports, energy plants, highways, hospitals and ports. The PPP burden on the budget could increase significantly since PPP projects have guarantees for foreign currency-denominated payments. Because of the sharp depreciation of the lira, these payment guarantees and usage fees have risen. The central bank has warned of exposure to exchange rate risk due to PPP project financing from foreign markets in foreign currencies (CBRT, 2016[20]) Another contingent liability arises from the KKM lira saving deposit scheme (see above, Box 1.6). Additional contingent liabilities are associated with policy measures implemented during the pandemic. A large portion of this support was off-budget and amounted to almost 10% of GDP, including public bank loans, government loan guarantees, and equity injections for both financial and non-financial firms. A significant share of these loans and guarantees were granted to households, firms and self-employed under financial constraints, and can become non-performing if the economy weakens.

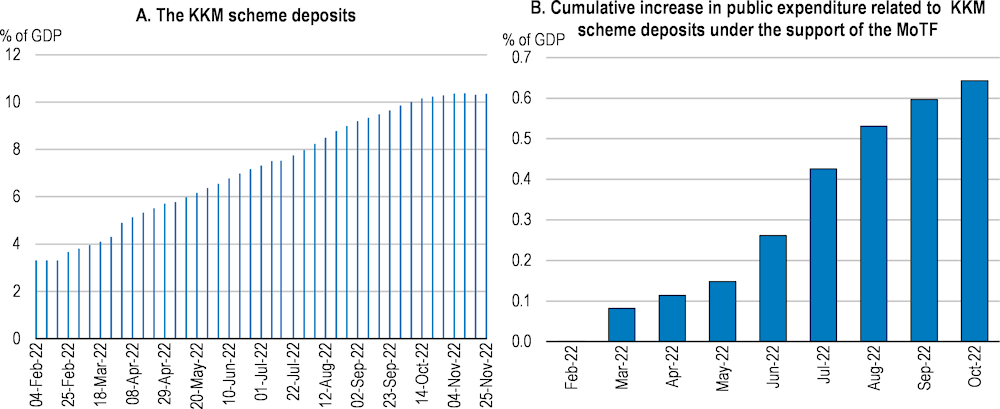

Box 1.6. Potential contingent liabilities from lira deposits that protect against lira depreciation

Since the end of 2021, the amount of lira deposits that protect against lira depreciation (KKM) has increased to reach 10.3% of GDP in December 2022, although it has been relatively stable in recent weeks (Figure 1.18, Panel A). Out of these deposits, those that have been converted from foreign currency (around 5% of GDP) are under the purview of the central bank and newly open KKM deposits (around 5% of GDP) are under that of the Ministry of Treasury and Finance (MoTF). The exchange rate guarantee can result in a high cost if the exchange rate depreciates. Data on the realised cost of the KKM schemes are available only for those supported by the MoTF. As of September 2022, these costs had reached 0.6% of GDP (Figure 1.18, Panel B).

Figure 1.18. The KKM scheme deposits are increasing public expenditures

Assessing the potential fiscal cost of the KKM scheme requires making assumptions on maturity, level of deposits and exchange rate developments. If the lira depreciate by 1 percentage point above the interest rate offered by commercial banks, then fiscal costs increase by 0.025% of GDP in 2023, assuming a three-months maturity and current level of deposits.

The expansion of contingent liabilities is increasing vulnerabilities to shocks. Closely monitoring contingent liabilities and improving fiscal transparency would help contain these vulnerabilities. As recommended in the previous OECD Economic Survey, Türkiye should publish a regular Fiscal Policy Report making risks related to public financial liabilities fully transparent (OECD, 2021[7]). There is also a need to further strengthen the framework for supervising and monitoring PPPs. Today, Türkiye’s legal structure regarding PPPs is fragmented, with legislation varying across different sectors. Instead, generic PPP-enabling legislation that would comprehensively regulate PPPs is needed (Eroğlu, 2021[21]). There is also room to improve the transparency of PPPs. Although annual reports provide information about total contract values along with yearly disbursements for realised liabilities and forecasts for three-year rolling liabilities, contract specifics such as government guarantees as well as analysis about contingent liabilities are missing.

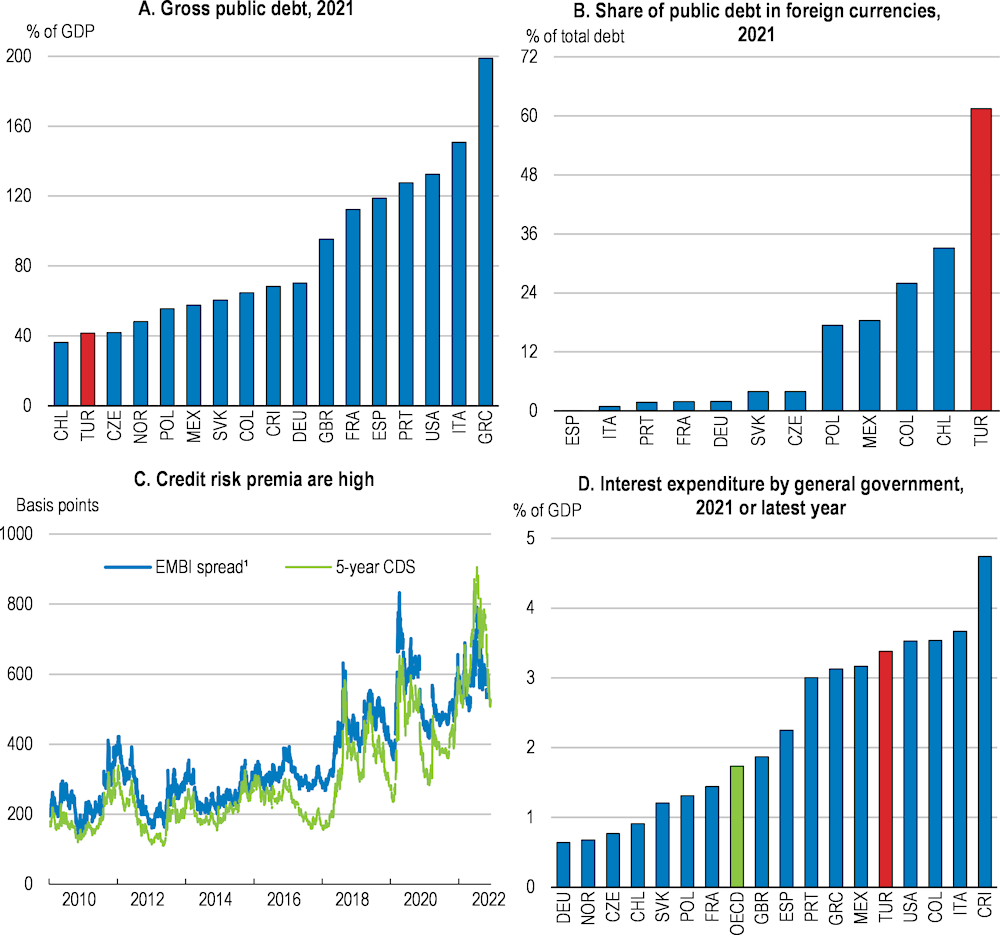

Government debt is set to increase further

Besides contingent liabilities, rising debt servicing costs are causing fiscal pressure. Türkiye’s government debt-to-GDP ratio is relatively low. Yet, because of the high risk premia, the government’s interest payments are high by international standards (Figure 1.19). Türkiye’s risk premium in intraday trading has increased this year and even surpassed 800 basis points. Additional risks stem from the structure of the debt. The share of debt denominated in foreign currencies has increased from 39% in 2017 to over 60% by 2021. In addition, 22% of the domestic debt is linked to the CPI index, which considerably raises the burden on public finances in the context of soaring inflation. The government expects to face an extra TRY 900 billion (0.7% of GDP) in interest costs in 2022, compared to 2021 (CBRT, 2022[4])). The bulk of government debt (75%) is held by the banking sector. In recent months, the lira bond yields has been decreasing as banks have been buying lira bonds as requirements for collateral and bank reserves (see above).

Figure 1.19. Government debt is low, but its structure makes it prone to risks

1. Stripped spread in basis points of the JP Morgan Emerging Market Bond Index (EMBI). Global index for Türkiye. The last data point refers to 12 December 2022.

Source: Factset; Refinitiv; IMF (2022), World Economic Outlook, October; and BIS.

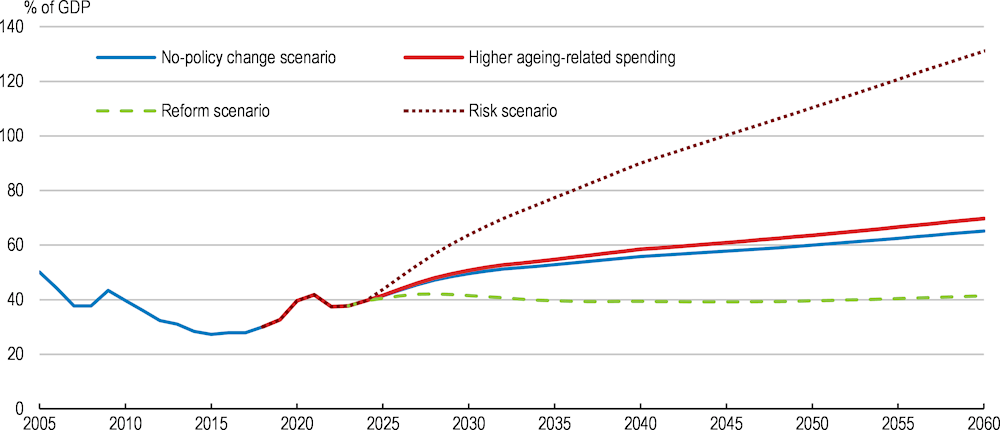

In the absence of reforms, government debt is expected to continue rising in coming years (Figure 1.20). If some risks associated with the current macroeconomic imbalances, high inflation, possible further lira depreciation and large contingent liabilities materialise, the fiscal deficit would widen and the interest rate on public debt would rise (Risk scenario). Reducing these risks and implementing labour and product market reforms will help put debt on a sustainable path and relieve fiscal pressure (Reform scenario). This would involve tightening monetary policy coupled with prudent fiscal policy. More specifically, the government should adhere to its plan to bring the primary balance back to a 1% surplus as envisaged in the economic reform programme (EC, 2021[22]).

Figure 1.20. More fiscal consolidation efforts are needed to reduce public debt

General government debt, Maastricht definition

Note: The no-policy change scenario assumes a continuation of the policy stance of 2021 with a deficit of 3.8% of GDP, with macroeconomic indicators based on the forthcoming OECD Economic Outlook 112 database and the OECD long term database. The higher ageing-related spending scenario assumes that health expenditures and pension transfers are higher by 0.2 percentage points of GDP than the no-policy change scenario. The risk scenario assumes that the deficit will increase by 2 percentage points and risk premia by 1 percentage point. The reform scenario assumes higher growth based on the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model (see Figure 1.3) and a fall in the interest rate on the debt by 1 percentage point.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), forthcoming; Guillemette, Y. and D. Turner (2018), "The Long View: Scenarios for the World Economy to 2060", OECD Economic Policy Paper No. 22.

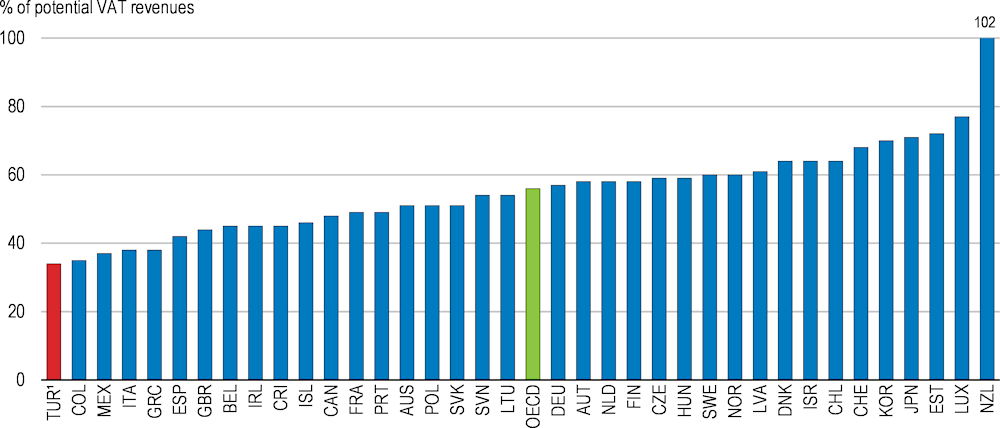

The tax base should be broadened

In addition to macroeconomic stabilisation, the authorities should address longstanding challenges, such as improving spending efficiency and broadening tax revenues. This can also help to finance various reforms (Box 1.7). Türkiye has one of the lowest tax-to-GDP ratios (24% of GDP) in the OECD, ranking 33rd out of 38 OECD countries in 2020 (OECD, 2021[7]). Statutory rates for the personal income tax, social contributions and VAT are broadly in line with OECD averages. However, the tax base is narrow and the number of taxpayers is low: less than 30% of the population actually pay the personal income tax compared to 60% in the OECD countries). In this regard, it is important that the authorities reform the labour market to promote formal job creation (Chapter 2).

Reducing exemptions would help broaden the tax base, thereby increasing revenues. Due to exemptions and discounts, approximately 24% of total tax revenues are waived (Bakanlığı, Hazine ve Maliye, 2018[23]; Gercek, 2019[24]). VAT revenues are particularly low compared to their potential (Figure 1.21). Evidence from other countries suggests that spending measures, such as transfers in cash or in kind, are considerably more efficient to achieve distributional objectives than reduced VAT rates (IMF, 2020[25]). For example, Türkiye applies lower VAT rates on theatre, cinema tickets or restaurants, which is particularly regressive as they benefit higher-income households disproportionately. Moreover, differential rates significantly complicate VAT administration and cause complexity in defining what goods precisely fall under the reduced rate.

The government should also make less frequent use of tax restructuring. In general, tax restructurings for unpaid tax liabilities are used to incentivise agents who have undeclared assets held offshore to regularise their tax position. There have been 13 tax restructurings since 2000 and in this context 37 tax laws have been enacted under different names. By resorting frequently to tax restructurings, the government has created disincentives for tax compliance. The large number of tax restructurings does undermine their effectiveness, as taxpayers may decide to postpone their tax compliance and just wait for the next tax restructuring. As underlined in the previous OECD Economic Survey, the recurrent use of tax restructurings should be discontinued (OECD, 2021[7]).

Figure 1.21. Exemptions and special rates erode VAT revenues

VAT revenue ratio, 2020

Note: The VAT revenue ratio is defined as the ratio between the actual value-added tax (VAT) revenue collected and the revenue that would theoretically be raised if VAT was applied at the standard rate to all final consumption (i.e. (Consumption - VAT revenue) x standard VAT rate). The OECD aggregate is the unweighted average of data shown. Data for Canada cover federal VAT only.

1. Data refer to 2019.

Source: OECD (2022), Consumption Tax Trends 2022: VAT/GST and Excise, Core Design Features and Trends.

Türkiye should carry out expenditure reviews to improve public spending effectiveness. Türkiye is one of the few OECD countries which does not conduct spending reviews (OECD, 2021[26]). In other countries, spending reviews supplement the conventional budgeting process characterised by incremental reallocations of spending. Although public expenditures are low in international comparison, there is room to improve efficiency (EC, 2021[22]). Expenditure reviews can identify large inefficiencies. For example, in the Slovak Republic, spending reviews completed in 2020 identified potential savings amounting to 1.2% of GDP in public employment and wages, defence and IT spending (OECD, 2022[27]). Italy’s central government has conducted multiple spending reviews since the global financial crisis, adopting them as a regular procedure. These reviews have helped the government achieve its savings goals (OECD, 2021[28]).

Experience from other countries suggests that spending reviews should be integrated into the preparation of the government’s budget and prepared early enough in the budget cycle to inform the budget. Spending reviews can be targeted to a specific area or general. Most OECD countries link the spending review process to the annual budget process or the medium-term expenditure framework. The Ministry of Finance should perform a fundamental coordination role, but line ministries should be involved in all stages of the spending process as they are responsible for implementing the decisions (Tryggvadottir, 2022[29]).

Box 1.7. Quantifying the impact of selected policy recommendations

Table 1.5 presents estimates of the fiscal impacts of the suggested reform package. The quantification is merely indicative and does not allow for behavioural responses.

In the short run, the government needs to reduce the structural budget deficit to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio. In the medium to long term, additional fiscal resources are needed to finance the recommended reform package. The reform package focuses on three main areas: (i) education (ii) labour policies and (iii) business regulations.

In addition, tax revenues would increase by 0.6% of GDP by 2030 due to dynamic effects of reforms on GDP growth (see simulation in Figure 1.3)

Table 1.5. Illustrative fiscal impact of recommended reforms

Fiscal savings (+) and costs (-), % current year GDP

|

|

2030 |

|---|---|

|

Costs of reforms |

-1.6 |

|

Strengthening education1 |

-1.6 |

|

Labour market reforms2 |

0 |

|

Improving business regulations3 |

0 |

|

Revenue measures |

1.6 |

|

Reducing tax inefficiencies4 |

1.0 |

|

Environmental taxation5 |

0.6 |

|

Overall budget impact |

0.0 |

Note: 1) Strengthening education: increasing spending in primary and secondary schools to the median of the OECD top 5 performers (1.6% of GDP)

2) Labour market reforms: (i) Make regulations governing permanent work contracts more flexible and increase the scope for fixed-term and temporary work agency contracts. (ii) Streamline subsidies for social security contributions and remove subsidies that provide similar incentives to lower social security contribution rates. (iii) Make statutory minimum wages more affordable for enterprises, for example by setting a minimum wage floor at the national level and promoting collective bargaining at the enterprise level. (iv) Shift social protection from the severance pay system to a broader-based unemployment insurance. Introduce portable severance accounts. (v) Reallocate funds devoted to wage subsidies to well-designed hiring subsidies targeted at most vulnerable groups. (vi) Increase the scope of job placement and counselling services by engaging private job placement and counselling providers through performance-based renumeration. (vii) Improve public job counselling services by leveraging digital tools to directly match vacancies to suitable candidates.

3) Improving business regulation: improvement of product market regulation to the level of the OECD.

4) Reducing tax inefficiencies: Reducing the VAT inefficiency gap to the OECD average.

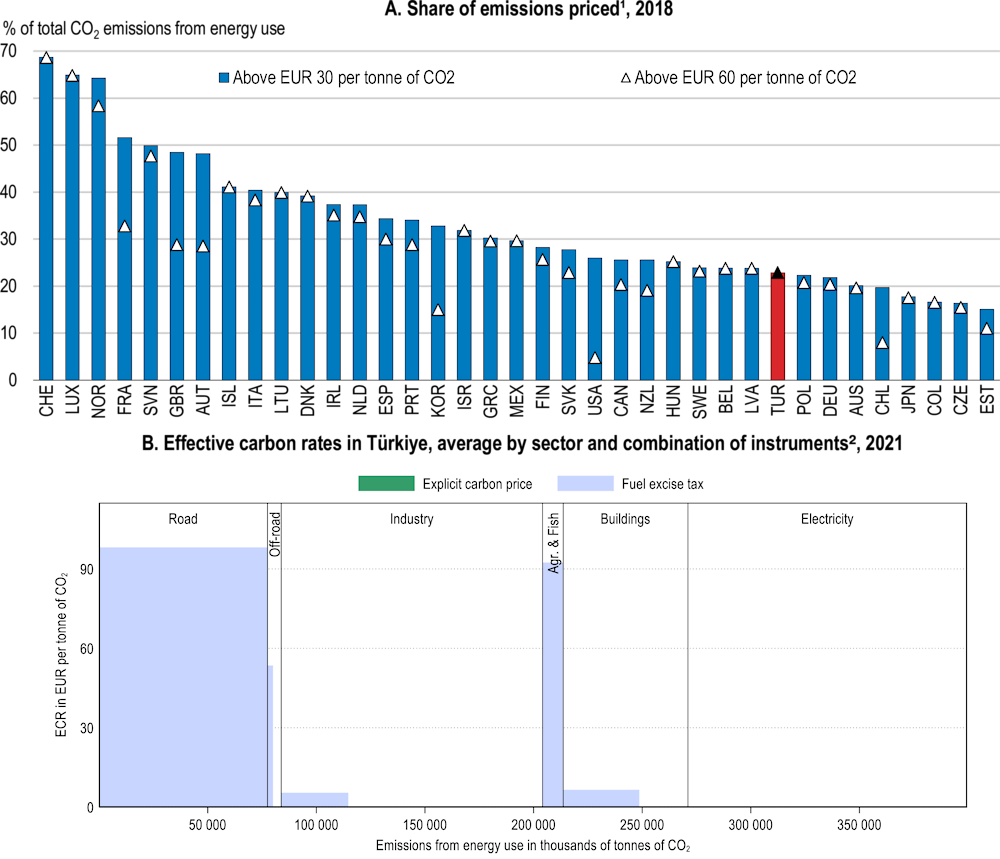

5) Environmental taxation: potential revenues from carbon pricing instruments for Türkiye (Marten and Dender, 2019[30]).

Source: OECD calculations.

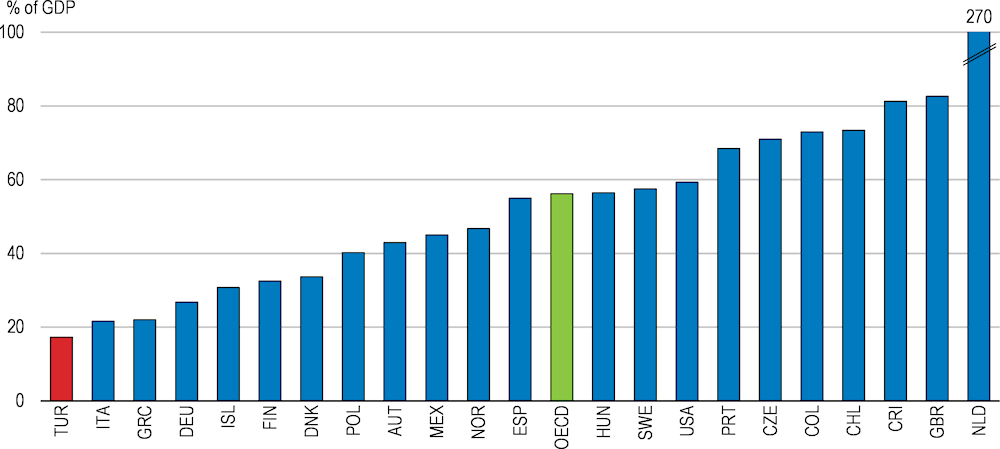

Addressing structural impediments to higher productivity growth

Addressing underlying structural issues will boost domestic and foreign investment and thus contribute to a more resilient economy. The contribution of total factor productivity to GDP growth has decreased during the past decade, reflecting impediments to an efficient allocation of resources (CBRT, 2021[31]; Akat and Gürsel, 2020[32]). Moreover, Türkiye is receiving less foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows than its peers (Figure 1.22).

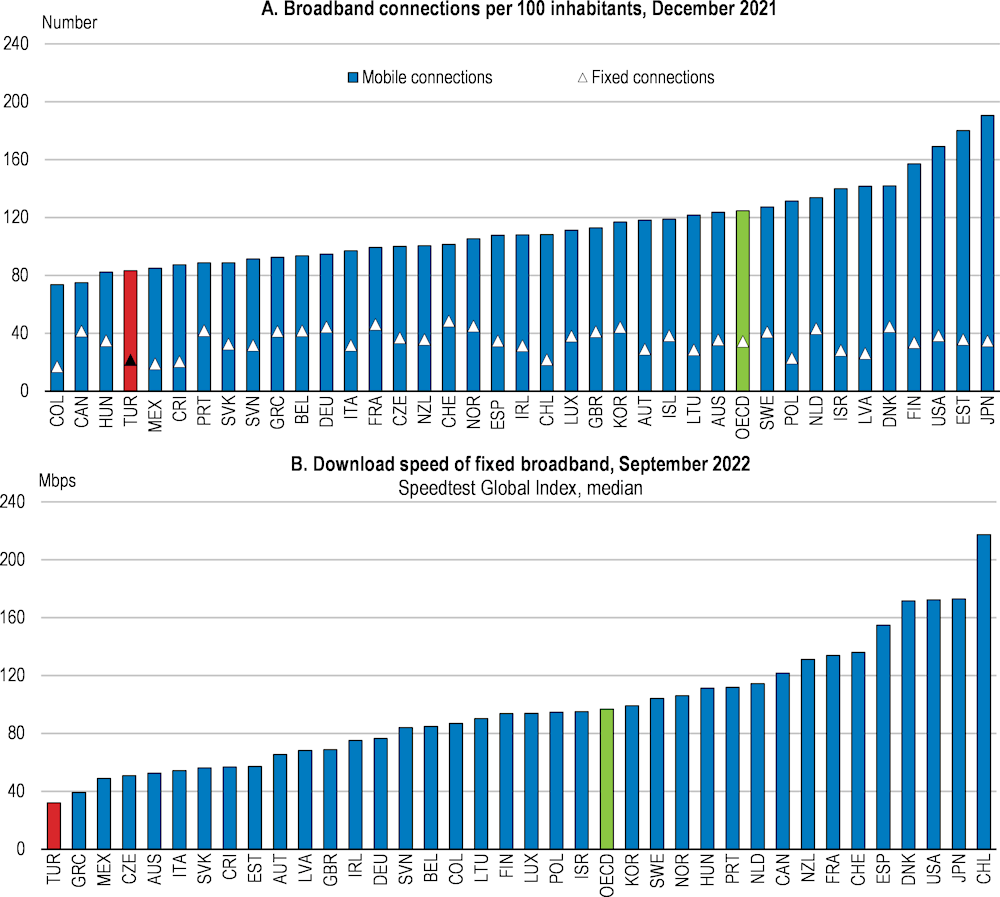

Two main challenges stand out to raise investment and productivity. The first is to foster open competition by ensuring a rules-based level playing field. This will require removing internal and external barriers to competition to reduce business costs, widen the range of goods and services available for people and firms, and promote the allocation of resources to the most promising sectors and firms. At the same time, Türkiye should strengthen the rule of law to ensure that regulations and rules are properly enforced without exemptions. The second challenge is to promote innovation and technological progress by raising R&D support and digitalisation. Empirical evidence further suggests that greater competition and lower trade barriers increase innovation (Bloom, Reenen and Williams, 2019[33]).

Figure 1.22. Türkiye has received less FDI than other OECD countries

Inward FDI stock, 2021 or latest year

Note: The inward FDI stock is defined as the value of foreign investors' equity in and net loans to enterprises resident in the reporting economy.

Source: OECD (2022), OECD International Direct Investment Statistics, "Benchmark definition, 4th edition (BMD4): Foreign direct investment: positions, main aggregates".

Removing barriers to competition

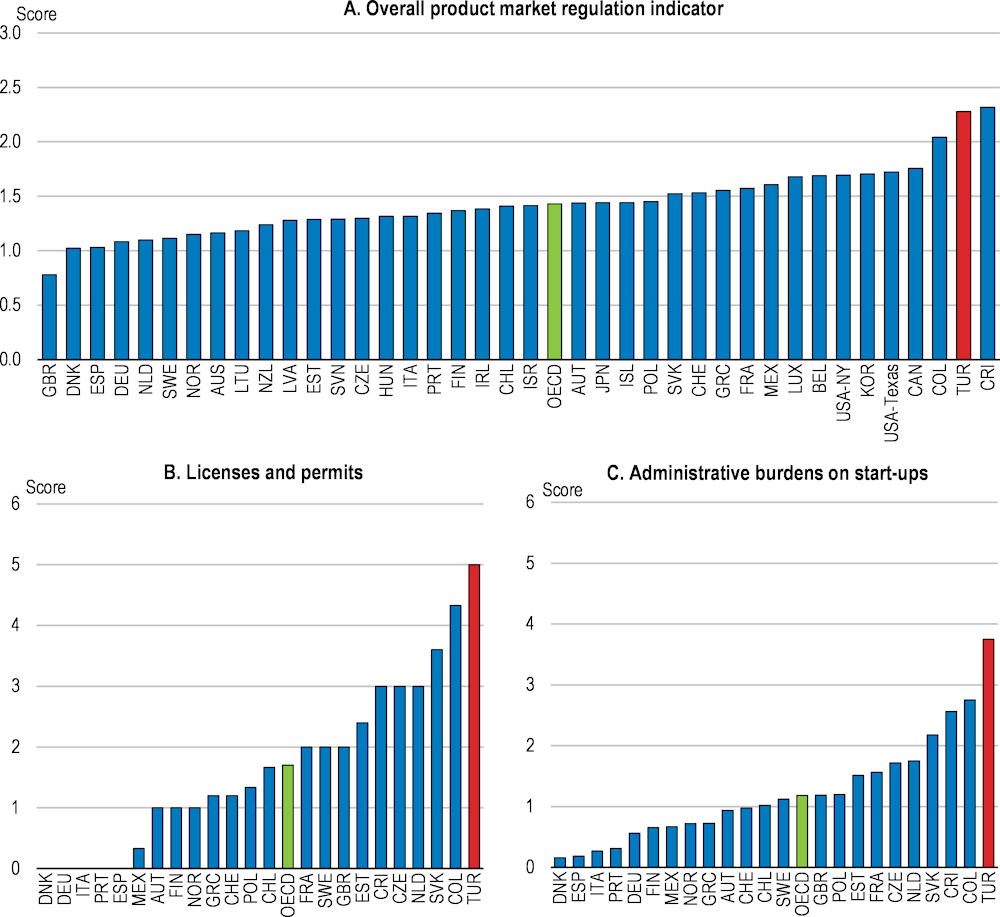

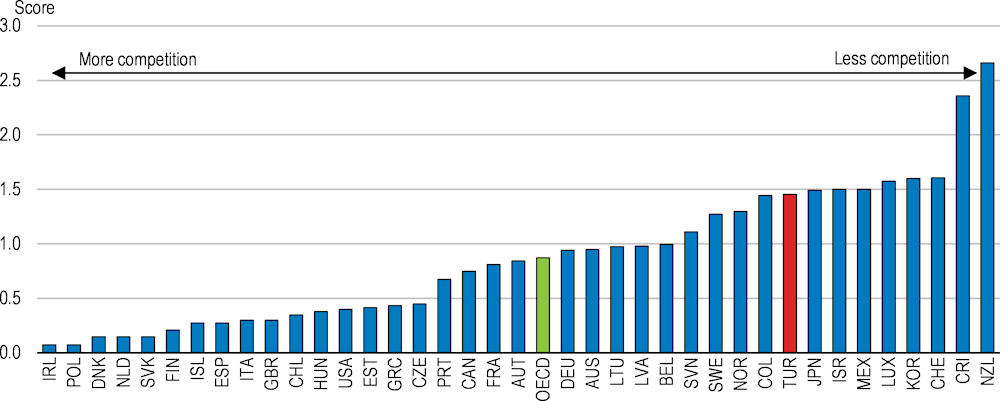

There is ample room to promote open competition in product markets in Türkiye (Figure 1.23, Panel A). Strict regulations shield incumbents from competition and limit the entry of new firms. Complex and burdensome administrative procedures required to obtain permits, licences, or concessions hold back the creation of formal firms. The licensing and permits system is the most restrictive in the OECD, as are entry barriers and administrative burdens on start-ups (Figure 1.23).

Türkiye should consider creating a one-stop shop, where all licenses and authorisations can be issued, and fully enforcing the “silence-is-consent” principle that is in place in many OECD countries. Although the Central Commercial Registration System allows for easy business registration, it lacks a centralised application process for the various licences and permits (OECD, 2019[34]). Portugal’s “Zero Licensing Initiative” has eliminated the need for several licenses from multiple interlocutors and replaced them with simple communication through the Entrepreneur’s Desk, working as a digital single point of contact (OECD, 2020[35]). A similar approach is used by the Slovak government, which has implemented the “Once is Enough” initiative, under which authorities are required to use available registers to access various certificates and licences so that businesses are requested to provide necessary documentation only once for all purposes (OECD, 2022[27]). The “silence-is-consent” principle should be fully enforced. This would reduce the administrative burden related to obtaining permits and licences (OECD, 2019[34]). For those licences and authorisations that Türkiye would keep, an assessment of whether specific licensing requirements create barriers to entry would be valuable and would contribute to improving competition in the country (OECD, 2019[36]).

Figure 1.23. Competition is hampered by domestic regulations

Product market regulation indicator, Scale from 0 to 6 (most restrictive)

Note: Information is based on laws and regulation in place on 1 January 2018 for all OECD countries except Estonia, Costa Rica and the United States (based on 1 January 2019).

Source: OECD (2022), OECD 2018 Product Market Regulation database, oecd.org/economy/reform/indicators-of-product-market-regulation.

Price controls in retail trade are much more widespread in Türkiye than in other OECD countries (OECD, 2022[37]). The prices of more than a quarter of the consumption basket used to measure headline inflation are set by public authorities, for example via price caps (EC, 2021[22]). There is considerable evidence across countries that price controls distort investment decisions and delay market entry (World Bank, 2020[38]). Countries’ experience also shows that reforming price controls can help promote competition and lead to more inclusive growth (World Bank, 2020[38]). The authorities should assess the pros and cons of existing price controls and gradually replace the most distorting ones by better-targeted social transfers to vulnerable households.

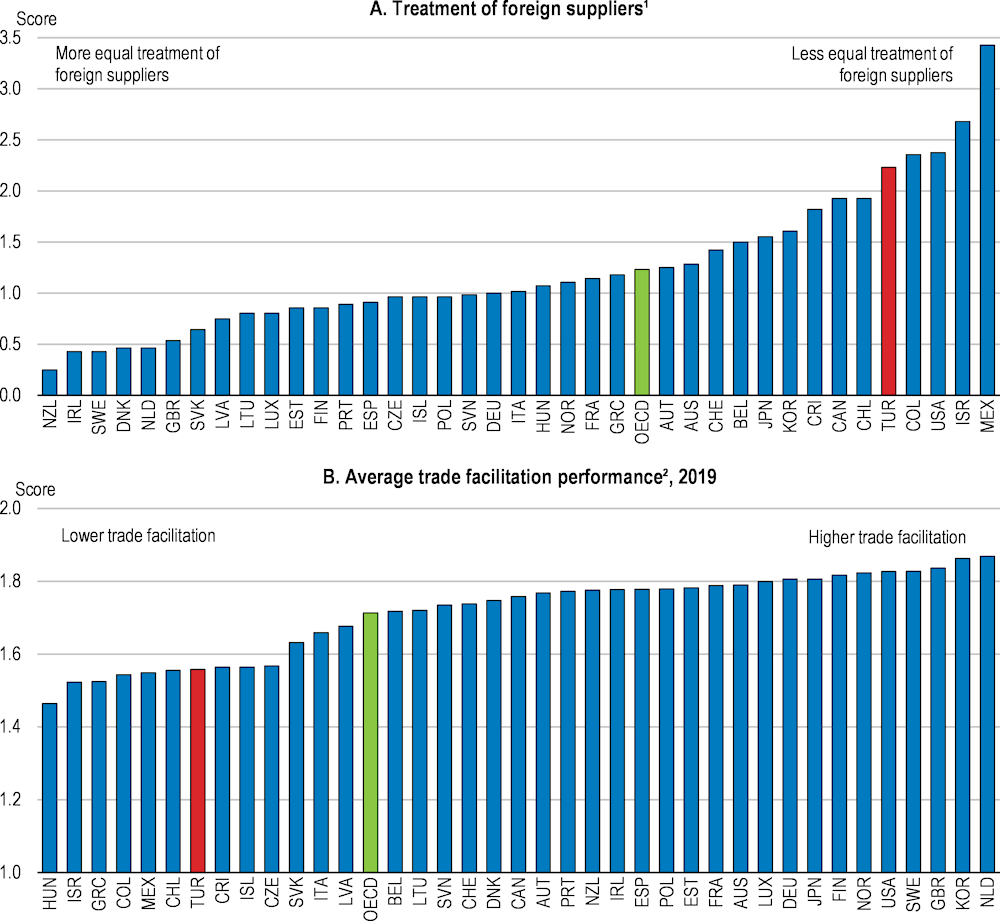

There is also room to further ease barriers to FDI inflows, which are positively associated with higher productivity and higher value-added exports (Blomström and Kokko, 2008[39]; Görg and Greenaway, 2004[40]). The OECD FDI restrictiveness index is close to the OECD average. However, restrictions on foreign ownership are stricter than in other countries (OECD, 2022[41]). Also, the treatment of foreign suppliers is one of the strictest in the OECD area (Figure 1.24, Panel A). While foreign investors are subject to equal treatment, firms using domestic products receive preferential treatment in public procurement processes. Almost half of all international tenders in 2020 involved a domestic price advantage for domestic bidders (EC, 2021[22]).

Figure 1.24. There is room to ease regulations affecting international trade and investment

1. Information is based on laws and regulation in place on 1 January 2018 for all OECD countries except Estonia, Costa Rica and the United States (based on 1 January 2019).

2. The OECD trade facilitation performance indicators are composed of eleven variables measuring the actual extent to which countries have introduced and implemented trade facilitation measures in absolute terms, but also their performance relative to others. The variables in the TFI dataset are coded with 0, 1, or 2. Unweighted average for the OECD aggregate.

Source: OECD (2022), OECD 2018 Product Market Regulation database, oecd.org/economy/reform/indicators-of-product-market-regulation; and OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators, https://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/trade-facilitation.

Tariff barriers to merchandise trade are relatively low, partly due to the EU Customs Union agreement but there is room to streamline technical and legal procedures for products entering or leaving the country (Figure 1.24, Panel B). Reforms with the greatest benefit are in the areas of information availability, advance rulings, fees and charges and external border agency cooperation. Under the aegis of the Trade Facilitation Coordination Committee, efforts to improve the above-mentioned technical and legal procedures continue. As mentioned in the previous OECD Economic Survey, broader coverage of the Customs Union (services) in collaboration with EU partners could foster competition and efficiency gains in the formal sector by spurring structural changes in agriculture, network services and public procurement (OECD, 2021[7]).

Table 1.6. Past recommendations and actions taken in business regulation

|

Recommendations |

Actions taken |

|---|---|

|

Encourage new equity injections and the re-capitalisation of non-financial firms to restore their investment capacity after the COVID-19 shock. Remove any remaining obstacles to their upscaling. |

In November 2021, several procedural adjustments were implemented in order to facilitate IPOs, including cost reduction and reduction of procedural burdens. |

|

Implement the recently introduced arbitration, mediation and framework agreement measures for financial restructurings. Be prepared to phase in additional measures to help courts to deal with insolvencies in case of need. |

The measures to help borrowers in financial difficulty regain their ability to pay were extended but will be valid only until July 2023. |

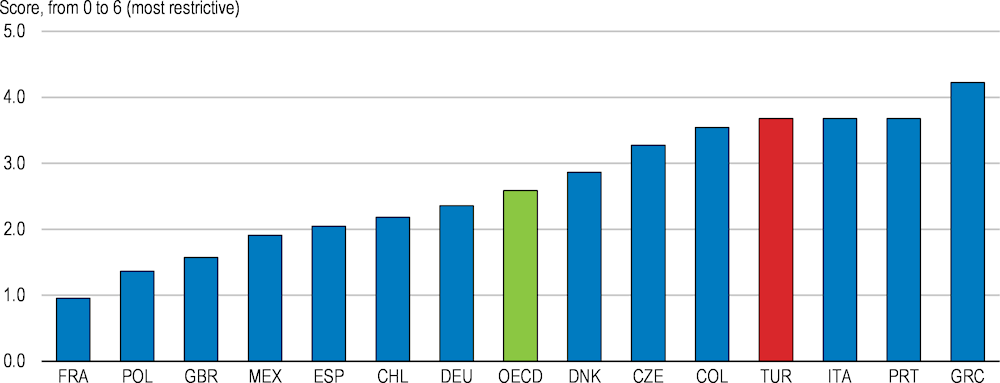

Strengthening the rule of law

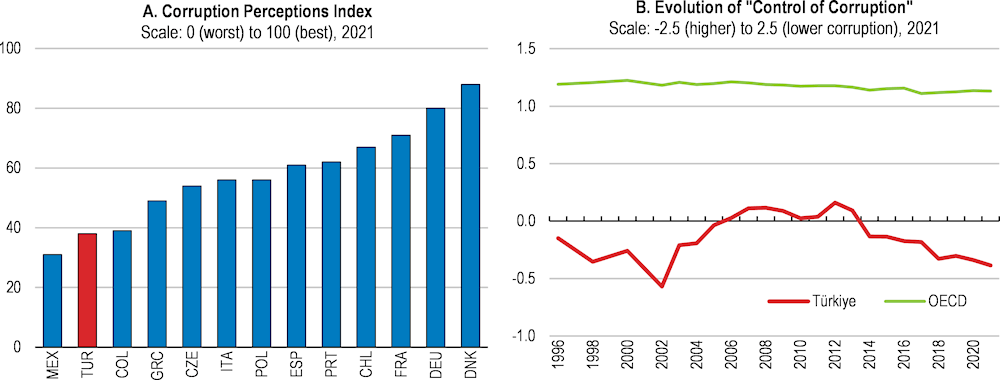

In addition to easing regulations, Türkiye must ensure that regulations and rules are properly enforced without exemptions. Empirical evidence confirms that strong governance and institutions that secure a well-functioning legal system are essential for productivity and competition (Égert and Gal, 2018[42]; Hall and Jones, 1999[43]). The perception of corruption in Türkiye is high, and the situation has deteriorated in recent years (Figure 1.25). Moreover, the new OECD Public Integrity Indicators show that the quality of the anti-corruption framework is low compared to other OECD countries (Smidova, Cavaciuti and Johnsøn, 2022[44]).

Figure 1.25. Perceived corruption is worsening from an already high level

Türkiye should effectively implement its international obligations to fight corruption and adhere to the United Nations Convention against Corruption and the Council of Europe Conventions (EC, 2021[22]). It should adopt an anti-corruption strategy underpinned by a credible and realistic action plan and establish a permanent and independent anti-corruption body. Türkiye also lacks whistle-blower protection legislation covering public and private sectors. This contrasts with most OECD countries, which have dedicated whistle-blower protection laws (OECD, 2016[45]). Although in Türkiye separate obligations are imposed on the health and safety officers to report safety related misconduct, a legal framework for whistle-blower protection is needed and can be aligned with the relevant EU legislation (EC, 2022[46]).

Interactions between interest groups and policymakers should become more transparent (Figure 1.26). Türkiye has made progress in this area. The Public Procurement Authority provides relevant statistics on the procurement process. On top, Türkiye, has introduced a mechanism to identify and address corrupt and fraudulent practices. However, the coverage of public procurement rules is reduced by exemptions, including contracts under TRY 18.6 million (around EUR 1 million), which weighs on transparency (EC, 2021[22]). Finally, Türkiye could follow the example of other OECD countries which have introduced lobbying regulations obliging members with executive power to report contacts with people lobbying to adopt a particular law or regulation.

Figure 1.26. Transparency with respect to interactions with interest groups is low

Product market regulation index for interaction with interest groups

Note: Information is based on laws and regulation in place on 1 January 2018 for all OECD countries except Estonia, Costa Rica and the United States (based on 1 January 2019). It measures the existence of rules for engaging stakeholders in the design of new regulation to reduce unnecessary restrictions to competition and for ensuring transparency in lobbying activities.

Source: OECD (2022), OECD 2018 Product Market Regulation database, oecd.org/economy/reform/indicators-of-product-market-regulation.

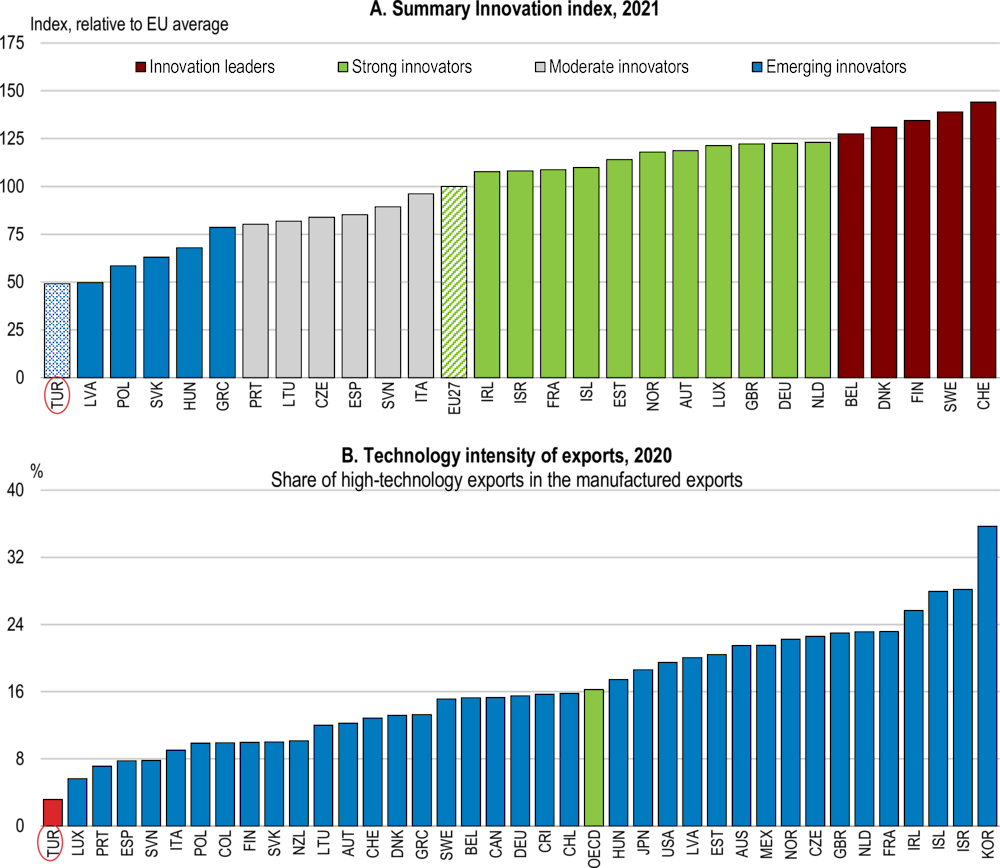

Enhancing research and innovation

Support for technological progress and innovation needs to be strengthened to foster productivity growth and raise living standards sustainably. Innovation performance lags behind other OECD countries (Figure 1.27, Panel A) and there are indications that technological upgrades to production have slowed over the past decade (Akat and Gürsel, 2020[32]). The technology content of exports has not improved significantly over the past decade: Turkish exports are the least technology-intensive among OECD countries (Figure 1.27, Panel B). To promote innovation and technological progress, it is necessary to create a favourable environment for research and development (R&D), including a stable macroeconomic environment (see above), a skilled workforce (Chapter 2), healthy competition and well-functioning product and labour markets (Chapter 2) (Bloom, Reenen and Williams, 2019[33]). In addition to these policies, many OECD countries provide direct and indirect incentives to increase R&D expenditures.

Figure 1.27. Türkiye's innovation performance is weak

Summary Innovation index, 2021

Note: The colours show normalised performance in 2021 relative to the EU 27 average in 2021: green above 125%; grey: between 100% and 125%; blue: between 70% and 100%; and below 70 %.

Source: European Commission, European Innovation Scoreboard 2021; and World Bank, World Development Indicators.

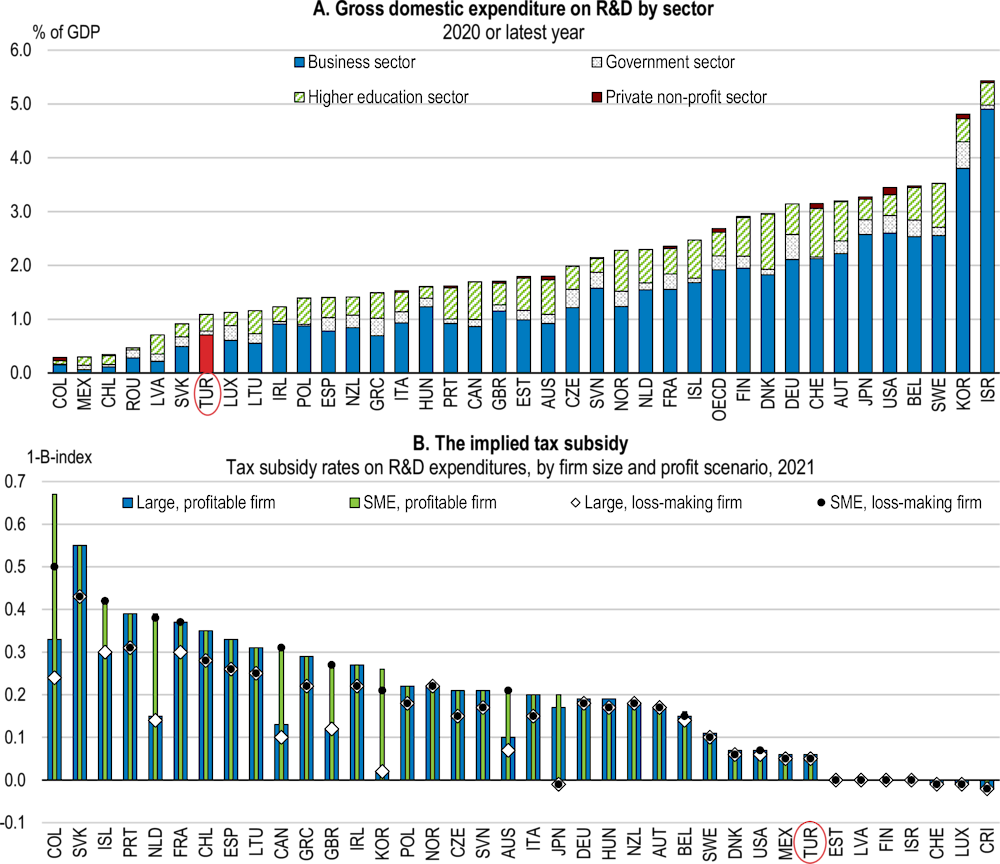

Türkiye’s spending on R&D remains low in international comparison (Figure 1.28, Panel A). Government support has almost doubled in the past 10 years mainly due to higher tax incentives. Türkiye relies on incentives that reduce the cost of R&D: accelerated tax depreciation and equipment used in R&D is exempt from stamp tax, fees and customs duties. Other documents related to R&D, innovation, and design projects benefit from stamp tax exemption. Türkiye also relies on income tax incentives: wages of researchers working in companies established in Technology Development Zones or in specific R&D projects are exempt from income withholding tax. Profits derived from products developed as a result of R&D activities, so called “patent box”, in these parks or Technology development zones are exempt from corporate income tax. Still, the marginal subsidy rate for R&D embodied in the tax system remains significantly below the OECD median for both SMEs and large companies (Figure 1.28, Panel B) and the overall generosity of the preferential tax treatment for R&D investment is much smaller than in most other OECD countries (Appelt, Hanappi and Cabral, 2021[47]).

Figure 1.28. Spending on R&D is low

Note: Implied marginal tax subsidy rates, presented for different firm size and profitability scenarios, are calculated based on headline tax credit/allowance rates, providing an upper bound value of the generosity of R&D tax support, not reflecting the effect of thresholds and ceilings that may limit the amount of qualifying R&D expenditure or value of tax relief. See http://www.oecd.org/sti/rd-tax-stats-bindex-ts-notes.pdf for more details.

Source: OECD (2022), OECD Research and Development Statistics (database); and OECD, R&D Tax Incentives Database, http://oe.cd/rdtax, December 2021.

International evidence suggests that tax incentives that reduce the cost of R&D should be strengthened at the expense of income tax incentives. Generally, R&D tax incentives hold the prospect of generating significant positive long-term growth effects (IMF, 2016[48]; OECD, 2016[49]) but their structure matters. Evidence from other countries shows that incentives that directly reduce the cost of R&D investment, such as tax credits or accelerated depreciation, are more efficient. In contrast, income tax incentives are generally less effective (OECD, 2016[49]; IMF, 2020[25]). Income tax incentives are often redundant, insofar as the investment would have also been undertaken without them. In this regard, evaluations of patent box regimes used in Türkiye show that such regimes either have no discernible impact on R&D or, where they do have an impact, entail significant fiscal costs (Gaessler and Hall, 2018[50]; IMF, 2020[25]). Before changing the R&D tax treatment, the authorities should prepare a proper evaluation of the current incentives.