Chapter 6 explores the role of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other actors in providing integrated service delivery (ISD) to victims/survivors of gender-based violence (GBV) and intimate partner violence (IPV). Governments and NGOs can usefully co‑ordinate service provision for a victim/survivor-centred approach. Co‑ordination often comes both in the form of co-location and referrals to established partners. At the same time, restricted flows of information across agencies and providers, together with unpredictable funding streams, risk harming NGOs’ capacity to respond to needs and effectively co‑ordinate services.

Supporting Lives Free from Intimate Partner Violence

6. Partnership in practice: Integrating non-governmental partners in the fight against IPV

Abstract

Key findings of this chapter

For a holistic, whole‑of-state response to gender-based violence (GBV) against women, governments’ direct service provision can be usefully complemented by that of non-government actors. Non-government organisations (NGOs) can play important roles in ensuring a victim/survivor-centred approach to fight IPV.

Often operating locally or based on “by-and-for” services, non-governmental providers can be more nimble than larger government providers and supply specific technical expertise valuable in the local context, keeping victims/survivors at the heart of provision.

Non-governmental providers can also offer a more informal route to help-seeking compared to official government-run services, especially when familiar actors in society are brought in as partners. In this sense, NGOs can both lower barriers to reporting abuse, and bring in actors to form a society-wide response to IPV.

Co-locating services is one useful approach to co‑ordinating services across non-governmental actors and government-run services. Where it is not possible to fully co-locate provision in one place – for instance when services target small populations or in rural areas – partial co-location with specialised services being available on certain days or by facilitated phone calls can be a good option.

Information sharing is key to the effective provision of services but can be especially hard to achieve across government and non-government providers. Clear rules and legislation on how, when and which data can be shared can help to ensure the safety of victims/survivors while being able to share the necessary information to provide appropriate services and avoid re‑victimisation.

Non-government providers typically rely on state funding, but these funding streams are often unpredictable. Unpredictable funding means that NGOs cannot operate in the optimal way, so governments should consider making sure that funding is sufficient and sufficiently consistent to enable longer-term planning.

6.1. Governments need non-government partners to respond to IPV most effectively

Since intimate partner violence (IPV) affects people and their activities throughout all of society, governments do well to partner with civil-society and non-government actors to deliver a holistic response. A “whole‑of-state” approach involves comprehensive legal frameworks, minimum standards for services, clearly outlined roles and responsibilities and buy-in across government (Chapter 1).

In addition to this, governments’ direct service provision can usefully be complemented by non-government actors to achieve holistic, survivor-centred responses. Non-government actors, including charities, social enterprises, schools, employers and places of business – such as pharmacies, grocery stores and hairdressers – can each play a role in a society-wide response to IPV. This chapter considers the role of partnerships between government and non-government actors in delivering integrated services to support victims/survivors of GBV – and IPV in particular. It highlights perspectives of non-government providers in delivering services, describe key challenges they face and explores how effectiveness can be further improved.

The chapter builds on existing research in the area by evaluating the results from novel findings from the 2022 Consultation with Non-Governmental Service Providers serving Gender-Based Violence (GBV) Victims/Survivors (the OECD Consultation 2022, see Annex B) (Box 6.1).

This chapter first argues that non-government actors are well-placed to deliver technical victim/survivor-centred services. Second, it details experiences of partnerships and co-location from the OECD Consultation 2022 and suggests some ways to improve co‑ordination. Finally, it discusses two main challenges faced by non-governmental providers: sharing information and managing funding streams.

Box 6.1. OECD 2022 Consultation with Non-Governmental Service Providers serving GBV Victims/Survivors

The OECD Consultation 2022 (see Annex B) collected responses from 27 non-governmental service providers working to support victims/survivors of GBV. Providers operated in 14 countries, including Belgium, Cameroon, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Mauritius, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Türkiye, and the United Kingdom. All categorised themselves as “non-profit, non-governmental organisation/programme that directly delivers services” except for one provider that described themselves as a “for-profit organisation that directly delivers services”. Given that nearly all respondents are non-profit, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), this chapter sometimes uses the term non-governmental organisation (NGO) in lieu of the more inclusive term non-governmental service provider.

The consulted providers include those who provide fully co-located services, a combination of integrated and co-located services and providing one primary service. The chapter also uses, albeit to a lesser extent, findings from the 2022 OECD Questionnaire on Integrated Service Delivery to Address Gender-Based Violence (OECD QISD-GBV, 2022, see Annex A) to which 35 out of 38 OECD member countries responded. (For more details about the OECD Consultation 2022 and the Questionnaire used in this report see Box 1.5 in Chapter 1, and Annex A and Annex B).

6.2. Non-government actors contribute to a victim/survivor-centred, society-wide service delivery approach

Non-government actors can help improve the coherence and coverage of service delivery by complementing public services. Smaller non-governmental providers operating locally can be more nimble than larger government providers and supply specific technical expertise valuable in the local context, keeping victims/survivors at the heart of provision. Non-governmental providers can also provide a less formal alternative to the state when seeking help, especially when familiar actors in society are brought in as partners. In doing so, non-governmental organisations play a key role in facilitating a “society-wide” response to GBV.

Non-governmental actors are often well-placed to offer victim/survivor-centred support in their community. Local circumstances can differ widely within the same country, and actors closer to the ground are often more tuned into specific circumstances relevant to their populations than national providers. Community needs can vary significantly between regions or even within cities, and geographic variation often compounds socio-economic differences and disadvantage.

For instance, there are significant regional divergences in the prevalence and experience of IPV across Canada, with rural areas facing some different challenges compared to urban areas, including geographical isolation, scarcity of resources and great difficulty keeping clients anonymous (Faller et al., 2018[1]; Beyer, Wallis and Hamberger, 2015[2]; Forsdick-Martz D., 2000[3]). Indeed, rural providers in Canada often improvise because they lack the specific capacities required to respond to a range of diverse needs (Chapter 1). In the United States, women in rural and isolated areas have to travel more than three times farther than women in urban and suburban areas, and over one‑quarter of sampled IPV victims/survivors in rural and isolated areas have to travel more than 40 miles (64 km) to the nearest services (Peek-Asa C., 2011[4]). It is important that services are adapted to the localities they serve, and can respond nimbly, so they can mitigate context-specific challenges experienced by victims/survivors (Box 6.2).

Box 6.2. Complementing governments in providing victims/survivor-centred services

Non-government service provision to support victims/survivors of GBV is widely present in OECD countries. The Istanbul Convention, which many OECD countries have signed, ratified and/or implemented (for more see Chapter 1), emphasises that measures taken to combat domestic violence shall involve, where appropriate, all relevant actors, including civil society organisations. It goes on to mandate that non-governmental actors and civil society be recognised, encouraged and supported at all levels to help combat violence against women (Council of Europe, 2011[5]). This box presents a few examples of how governments work with non-governmental organisations, but the form of funding and support can take many different forms.

Lithuania works with non-governmental providers for specialised services

In Lithuania, non-governmental providers are funded to provide a specialised help services for victims/survivors of GBV through the Specialised Comprehensive Assistance Centres. For instance, they receive financial support from the state budget to provide complex services to children-victim of violence. Within the projects funded by state budget, non-governmental organisation provide services including psychological counselling, psychotherapy, legal services and informational campaigns. Preventive services include positive parenting services, psychological assistance and a Parent Hotline that focuses on psychological consultations provided for free.

Finland entrusts civil-society organisations with providing legal aid and support

The Finnish Ministry of Justice has entrusted Victim Support Finland with a public service obligation to provide and produce general support services for victims of crime under the Victims’ Rights Directive from 2018 to 2027. In 2020, most of the contacts to VSF were related to domestic violence (24%) and sexual crimes (14%).

Ireland funds non-governmental providers to lead on provision of housing and refuges

The Irish Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage’s role is to support the work of local authorities and non-governmental organisation who provide accommodation support to victims of domestic, sexual and gender-based violence. This included capital funding support for the development of new refuges. Support for the provision of new refuges will continue under the capital assistance scheme “Housing for All”.

Source: OECD QISD-GBV, 2022 (Annex A).

6.2.1. Local providers can address local service needs well

The intersection of social identity and various other forms of disadvantage and vulnerability, such as geographical and social isolation, poverty or lack of access to employment and minority status, can increase the risk of exposure to violence from an intimate partner (Faller et al., 2018[1]). Women facing intersectional disadvantages also often face higher barriers to reporting violence and accessing services than women with fewer disadvantages (Baker et al., 2015[6]; UN Women, 2019[7]). The ability to seek and access help can be influenced by for instance citizenship status, language fluency, financial means, employment status, overall physical and mental health and parental status (Marchbank, 2020[8]). In addition, marginalised populations, such as members of Black, Indigenous, or other ethnic minorities, as well as sex workers, members of the LGBTI+ community and homeless people might have negative past experiences or legacy tensions with formal institutions, and especially the police (Mundy and Seuffert, 2021[9]).

Specific local circumstances intersect with other sources of disadvantage for certain groups, which often increases the need for case‑sensitive responses from service providers. For instance, interviews with providers in northern Canada show that many women who need to escape violent partners in the rural and northern regions face a situation where the nearest services are far away and ways of getting to them are limited (Pauktuutit, 2019[10]). In Paris, women’s experiences are shaped by the neighbourhood they live in. A study using survey evidence from different family planning centres the metropolitan Paris area finds that experiences differ markedly across centres in different neighbourhoods within the same larger suburban area. Even after controlling for general instability and centre, women who were undocumented or temporarily documented, were out of work, and/or experiencing housing insecurity were most likely to report violence than their less-disadvantaged peers (Roland et al., 2022[11]).

The value of acknowledging intersectionalities is recognised in the UN Women’s Handbook for National Action Plans on Violence Against Women (UN Women, 2012[12]) recognises that women’s experiences of violence are shaped by social, economic, health and identity factors, and UN Women (2019[7]) highlights the value of specialist services run “by and for” the communities they aim to support. In response, Article 12 of the Istanbul Convention specifically calls on parties to “take into account and address the specific needs of persons made vulnerable by particular circumstances” (Council of Europe, 2011[5]).1

6.2.2. “By-and-for” providers offer valuable expertise to address intersectional needs

To address these intersectional needs, “by-and-for” service providers play an important role. “By-and-for” service provision refers to services that are run by people from the community they aim to serve (Domestic Abuse Commissioner, 2021[13]). Together with other non-governmental providers with specific technical expertise, “by-and-for” providers add value both due to their context-specific knowledge of how to address intersectionalities, and due to their roots in communities, which can help inspire confidence and feelings of safety that are essential to victims/survivors.

These providers can also add value in informing quality standards and the government approach to service provision (UN Women, 2020[14]; Htun and Weldon, 2018[15]). For instance, Jewish Women’s Aid UK provides a secure refuge where Kashrut, Shabbat and festivals are fully observed, which can be an important asset for observant victims/survivors. At Asian Women’s Resource Centre UK, victims/survivors do not need to speak in English if they have a different preferred language and they meet professionals who understand the cultural context of the abuse and perpetrator (Centre for Social Justice, 2022[16]). In the United Kingdom, front line workers identify a need for greater investment in “by-and-for” services, with the limited number of specialist refuges often oversubscribed (Safety4Sisters, 2020[17]). Respondents to the OECD QISD-GBV 2022 valued this specialised technical expertise of non-governmental providers and communicated a desire to protect the independence of these service providers (Box 6.2).

6.2.3. Familiar organisations can be easier to approach than formal government agencies

It is valuable to have diverse, non-governmental actors embedded throughout society who can respond to the needs of victims/survivors. Many women find it difficult to report or seek help for violence, for instance because they experience stigma, have a lack of support networks, or do not believe that they will be treated with respect by formal institutions (Chapter 2).

Barriers reporting and/or escaping IPV can be lowered when victims/survivors have the option to use points of contact in places that are more familiar and less formal than government (Sylaska and Edwards, 2014[18]; World Health Organization and Pan American Health Organization, 2012[19]). Charities, the private sector and other familiar non-government institutions are well-placed to act as points of contact and support that bring services closer to women and increase awareness of the right to a violence‑free life (UN Women, 2020[14]; Council of Europe, 2022[20]). This broadening of opportunities to report and seek help contribute to governments achieving a whole‑of-society approach to respond more effectively to IPV.

One way non-government organisations act as points of contact for women affected by IPV is by training workers in sectors that people often come into contact with, such as education systems, postal systems, and the health care system (Box 6.3; (OECD, 2020[21])). For instance, in the Czech Republic, postal workers received training from the NGO Rosa to recognise signs of domestic violence, communicate with victims about their situation, and offer support and referrals (UN Women, 2020[14]; PostEurop, 2020[22]). In the United Kingdom, the non-governmental organisation Women’s Aid trained Jobcentre staff to support women experiencing domestic abuse in 2019 (Department for Work and Pensions, 2019[23]). Now each Jobcentre Plus has assigned points of contact who support those seeking help in situations of domestic violence (Home Office, 2022[24]).

There is scope for doing more in the area of training staff in service occupations with a high degree of client interface. For instance, a 2017 UK medical school survey showed that while 21 out of 25 surveyed institutions delivered some education around domestic violence, 15 of respondents felt training was inadequate. Eleven of the surveyed institutions reported providing fewer than two hours on the subject over a five‑year course (Potter and Feder, 2017[25]) (Chapter 3).

Some actors in the private sector have taken initiative, too, both in the public sphere and for its own employees. The “One in Three Women” campaign, for example, has brought together 14 multinational companies to develop best practice on supporting employees who are victims/survivors and promoting community outreach. And due to the heightened risk of violence during COVID‑19, Vodafone launched an internal awareness-raising campaign and refocused its global policy on ensuring that employees can work safely from home. Their updated policy details comprehensive workplace support, including ten days of paid safe leave and security measures adapted to remote working from home (UN Women, 2020[14]).

Box 6.3. Pharmacies are well-placed as support hubs since they are regularly visited

Women in Canary Islands, Spain, can use code words to seek help

During the COVID‑19 pandemic, many opportunities to move outside of the home were removed, which prompted the Institute for Equality of the Canary Islands to launch the Mascarilla‑19 (“Mask 19”) campaign. Since pharmacies were one of few essential businesses to remain open during the lockdowns imposed, these provided reliable places from which to provide assistance to victims/survivors of IPV. Woman seeking help could go to a local pharmacy and request a “Mask 19”. The pharmacy staff would then note down contact details, notify the police and contact support workers (UN Women, 2020[14]).

Because of the campaign’s success in Spain, similar initiatives were subsequently launched in Argentina, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and Norway (UN Women, 2020[14]). The success of the programme has also meant that pharmacies continue to play a more important role in the Government’s fight against GBV and IPV in Spain. In 2021, the Government Office against GBV signed an agreement with The General Pharmaceutical Council of Spain to conduct awareness campaigns via pharmacies (Ministry for Equality, 2021[26]).

UK’s pharmacies partner with non-governmental providers to open up as GBV support hubs

During May 2020, pharmacies started providing Safe Spaces within their facilities to support victims/survivors of GBV. The initiative was launched by the UK Says No More campaign and worked with pharmacy chains including Boots, Superdrug, Morrisons, and independent pharmacies. The Safe Spaces offered victims/survivors the possibility to safely contact specialist services (Centre for Social Justice, 2022[16]). By October 2020, a report estimated that one‑quarter of pharmacies across the United Kingdom facilitated a Safe Space in their consultation rooms. Since the launch of the scheme, there had been at least 3 700 visits to a Safe Space. (Hestia, 2020[27]).

6.3. Co-location helps non-governmental organisations provide effective services

One approach to integrated service delivery is the co-location of service provision (Chapter 1). This is approach is increasingly common among non-governmental providers: a large‑scale mapping of shelters in North America, for example, shows that many offer a variety of services at the location of the shelter, as well as through referrals and transfers on an ad hoc basis. The most commonly provided services included crisis management, counselling and mental health support, but children’s needs, education and legal advice were also common (Samardzic and Morton, 2020[28]). This co-located approach is also used by service providers connected to the European Family Justice Center Alliance (for more on this, see Box 1.4 in Chapter 1) and the growing network replicating the “Maison des Femmes” model in France (Box 6.4Box 6.4.). These co-located centres are usually financed privately and publicly.

Co-location of different non-governmental providers in one place can improve victims/survivors’ access to different services and greater technical expertise to address specific needs. When services are co-located and/or operating under established partnerships, there is also potentially less of a need for case managers to assist help-seekers navigate a complex system, thereby potentially improving efficiency and effectiveness.

6.3.1. Service providers report the benefits of co-located services

The OECD Consultation 2022 suggests that non-governmental provider see value in integration, co-location and partnerships to provide services. In response to the OECD Consultation 2022 question “What strategies have worked to improve the efficiency of services and trauma reduction?”, one organisation reports that it helps to have “co‑operation with medical institutions, [a] common understanding what the victim needs are, [and a] multidisciplinary approach”. Similarly, another response finds that “Well-established structures of co‑operation at [the] local level” are successful. The responding organisation goes on to specify: “this includes modelling the usual paths of clients, so that everyone knows what they can do themselves [and] when and to whom to guide to if [additional help is] needed”. Box 6.4 offers an example of co-location in practice.

Box 6.4. Maison des Femmes in France co-locates cross-sector support

The Maison des Femmes (Women’s House) in the suburbs of Paris is a structure that has been specifically dedicated to offering interdisciplinary support by co-locating health, social and judicial services. It is located on the grounds of a public hospital in a separate building and offers services including physical medical care (including contraception, abortion care, clitoral reconstruction surgeries), legal counsel, and psychological consultations (Roland et al., 2022[11]). The model is being rolled out in France and several similar structures have been opened in Bordeaux, Marseille and other cities.

A study compares the clients cared for in the Maison des Femmes with those cared for in two other more typical Family Planning centres women exposed to violence also tend to visit. It is found that despite the centres being geographically very close to each other, survey evidence from clients show that the proportion of women reporting IPV in Maison des Femmes was considerably higher than the proportion in the other two centres. This might suggest that many victims/survivors who seek help are aware of the ability to visit a dedicated centre with co-located specialist services (Roland et al., 2022[11]).

Source: Maison des Femmes (www.lamaisondesfemmes.fr).

The value of co-located services is reflected in the organisational structure of many of the providers who participated in the OECD Consultation 2022. Fifteen of the 27 organisations that responded to the OECD Consultation 2022 reported that they had established partnerships with other organisations working fully or partly in the same location. Eleven focused on providing one primary service, although they also have established partnerships with other local service providers and/or agencies with whom they co‑operate on a regular basis. (One provider did not specify their level of co‑ordination).

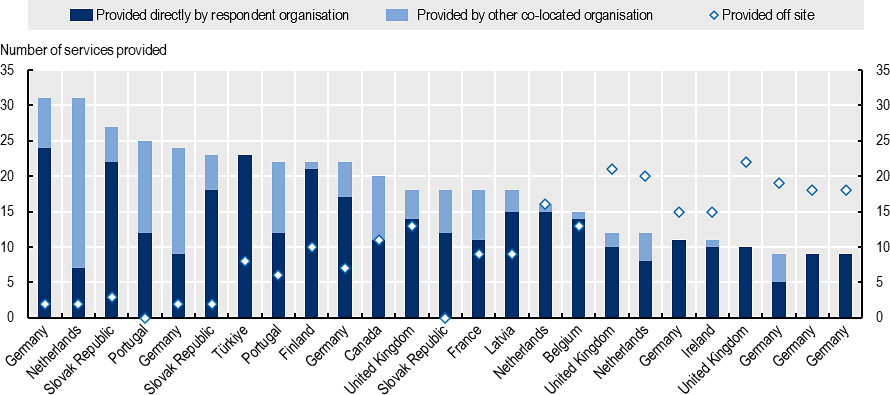

They survey also asked respondents about the nature of service provision. Respondents were asked which services are provided: “(a) directly by your staff; (b) directly by staff working through a co-location arrangement; (c) directly via referral to established partners who visit your organisation to meet with clients; (d) provided directly via referral to an affiliated or unaffiliated provider located off-site; or (e) not available in your area”. The answers, illustrated in Figure 6.1, suggest that when more services are provided on-site, either by the respondent or by a partner provider who is wholly or partly co-located, there tends to be less of a need to refer help-seekers to off-site service providers.

Figure 6.1. Co-location can help increase service provision at one site

Note: x-axis labels present the country name of the responding organisation; the y-axis value is therefore not a nationally-representative value for the listed country. This chart excludes three respondents: organisations from two non-OECD member countries and one due to lack of data.

Source: 2022 OECD Consultation with Non-Governmental Service Providers serving GBV Victims/Survivors (Chapter 1, Box 1.5).

6.3.2. Partner organisations play an important role in offering specific expertise

A single service provider is unlikely to have adequately skilled staff, resources and capacity to address all of the diverse needs of victims/survivors. The OECD Consultation 2022 suggests that some services requiring more technical or specific expertise were more frequently provided by co-located partners. These services are interpretation and translation (11 respondents report that this service is provided through a co-located provider), substance use and addiction counselling services (8), and job training, reskilling or adult education programs (8).

Full co-location may not be feasible for services that are not frequently needed. A solution to this is to partly co-locate services, for example by hosting regular site visits by, or facilitate virtual meetings with, professionals with specific technical expertise. This can be a practical solution in rural areas where full-time professionals may not be needed at every site. Respondents to the OECD Consultation 2022 reported that regular visits by different providers to the respondent’s site was the most frequent co-location/co‑ordination agreement for issues related to support for LGTBI+ victims/survivors, short-term and long-term housing, divorce or child custody related support, children’s school liaisons.

The OECD Consultation 2022 also provides some initial indications that there may be scope for further co-location among some of the organisations that responded. This can be seen for organisations that have made little use of co-location yet refer many help-seekers to off-site providers (Figure 6.1). It was common to provide referrals to services located off site for services related to substance use and addiction counselling services (13 respondents report referring to off-site providers for this service) and job training, reskilling or adult education (11). Other services that were often provided by referral to organisations off-site included civil legal matters (11), legal counselling (11) and matters related to residency status, immigration and asylum (12) as well as second-stage/transitional housing (11) and long-term affordable housing (11).

6.4. Governments can strengthen safe information sharing routines across sectors

Secure and effective sharing of information is essential to providing integrated services, and this is a particular challenge for non-governmental organisations that are less likely to hold or be able to access relevant information about victims/survivors than the government. Effective sharing of information can prevent re‑traumatisation from having to describe experiences of abuse several times and lead to a more efficient and timely public response when women experience violence. At the same time, data privacy is of utmost concern when it comes to victims/survivors of GBV and the risk of personal information leaking increases as more agencies have access to that information (see Chapter 1 for an extensive discussion on problems with data sharing). Several respondents to the OECD Consultation 2022 (see Annex B) suggested that better forms of information sharing – for example, via formal arrangements or an integrated database – are essential to improving outcomes for help-seeking individuals.

Yet data sharing goals face challenges in the field. Providers participating in the OECD Consultation 2022 were asked “How satisfied are you with existing co‑ordination mechanisms between sectors and service providers in your area working to support people who have experienced GBV?”. Only 12 report that they are satisfied or very satisfied, six neither/nor, and nine that they are dissatisfied or very dissatisfied.

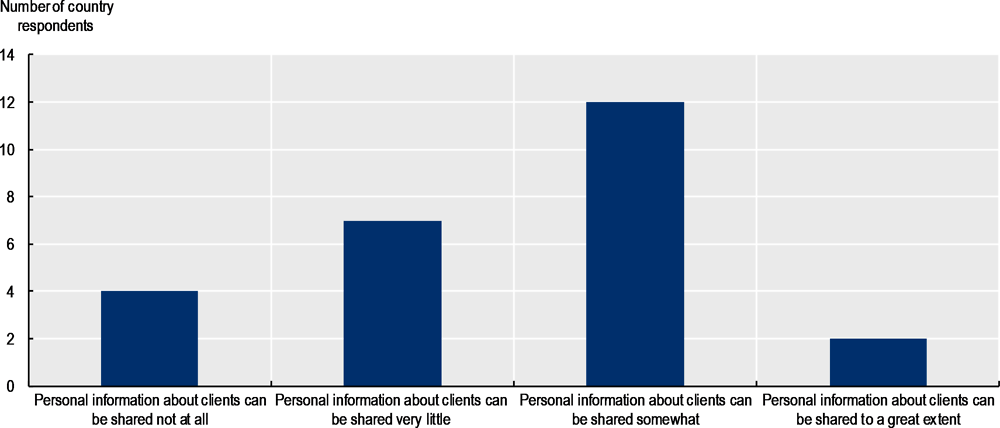

Similar findings emerge from the OECD QISD-GBV 2022 sent to governments. Out of the 26 countries that responded to the question “To what degree can personal information about clients be shared, for example between government and non-governmental agencies or case or social workers and doctors to help reduce the administrative burden and costs for both clients and providers?”, only two report that information could be shared “to a great extent”; twelve report “somewhat”; seven “very little”; and four “not at all” (Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2. Few countries report that client data can be easily shared

Note: Figure 6.2 presents the distribution of responses to the question, “To what degree can personal information about clients be shared (for example between government and non-governmental agencies, case workers, and doctors) to help reduce the administrative burden and costs for both clients and providers?” Two respondent organisations provided two answers. In those instances, the more conservative option was selected as the primary response. 10 respondents are excluded, one responded “don’t know” and nine did not respond.

Source: OECD QISD-GBV 2022 (Annex A).

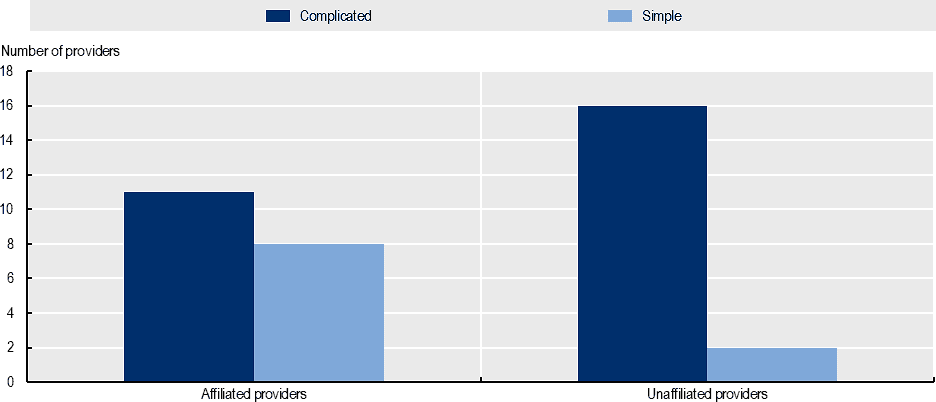

The OECD Consultation 2022 also suggests that partnerships and information sharing go together. Descriptively it appears easier to share case‑related information between affiliated service providers where established partnerships exist, for example, in a situation of co-location. Eight respondents to the OECD Consultation 2022 say that sharing information with affiliated partners is simple or extremely simple, while only two report that information sharing is simple or extremely simple in cases where there are no established affiliation or partnership (Figure 6.3). Part of the reason may be that stakeholders often jointly develop co‑ordinated information-sharing protocols and procedures in collaborative service delivery arrangements, so that they can collaborate to perform informed risk assessments and deliver effective solutions to help-seekers (CACP, 2016[29]). In the absence of such protocols, the norm of client privacy siloes prevails.

Figure 6.3. Partnerships and data sharing go hand in hand

Note: Reports results from two questions; 1 “How simple is it for service providers from your organisation to share case‑related information with other service providers who are affiliated with your organisation through established partnerships, but who are employed by different agencies; for example, in a situation of co-location?” and 2 “How simple is it for service providers from your organisation to share case‑related information with other service providers who are unaffiliated and/or operating in a different sector?”. One respondent is excluded due to lack of data. The figure does not report respondents who respond “Neither simple nor complicated”, which are seven with regards to Affiliated partners and eight with regards to Unaffiliated partners.

Source: 2022 OECD Consultation with Non-Governmental Service Providers serving GBV Victims/Survivors (Chapter 1, Box 1.5).

6.5. Funding streams should be predictable to facilitate stable service provision

External funding for non-governmental providers is often fragmented, limited and short-sighted, making day-to-day operation difficult and meaning that organisations are not always able to provide services to as high a standard (or with as broad coverage) as they aim to. This also makes long-term partnerships, collaborative working and integration harder to achieve. Moreover, research from the social services sector finds that funding that directly targets the integration of service delivery also tends to be short-term in nature, as it often supports time‑limited pilot schemes and trials (OECD, 2015[30]). More predictable funding streams – and funding specifically to achieve efficiency gains, partnerships and cross-sector collaboration – could help provide better services to victims/survivors and help non-governmental providers settle more firmly into cross-sector partnerships and co-located facilities.

6.5.1. Insecure funding risks destabilising service delivery

Non-government providers often flag that their lack of secure funding ends up limiting the services that they are able to operate. Resource shortages and funding delays can be an obstacle to implementation of time‑sensitive action plans, such as in crisis-response intervention (Schreiber, Maercker and Renneberg, 2010[31]). Variable funding streams can also complicate the provision of ongoing services, through limiting the ability of providers to plan strategically for the future and hire and retain staff. This can create a heavy reliance on volunteers (Centre for Social Justice, 2022[16]; Baffsky et al., 2022[32]; Skinner and Rosenberg, 2006[33]). These findings are echoed by respondents to the OECD Consultation 2022. For instance, when asked to describe resources or procedural adjustments that would make a significant impact for clients in the way of streamlining services, one provider responds that “more advice would be possible if the institution were independent of donations.”

Providers responding to the OECD Consultation 2022 report that their funding is often concentrated across few sources. Nine providers (out of 23 answering this question) report that they are receiving funding from three or fewer funding sources. Nine providers also report that 81‑100% of their budget comes from one single funder, with some providers reporting that this large portion is combined with various smaller pots and some reporting few, if any, additional sources. This concentrated funding comes from national, regional or municipal government.

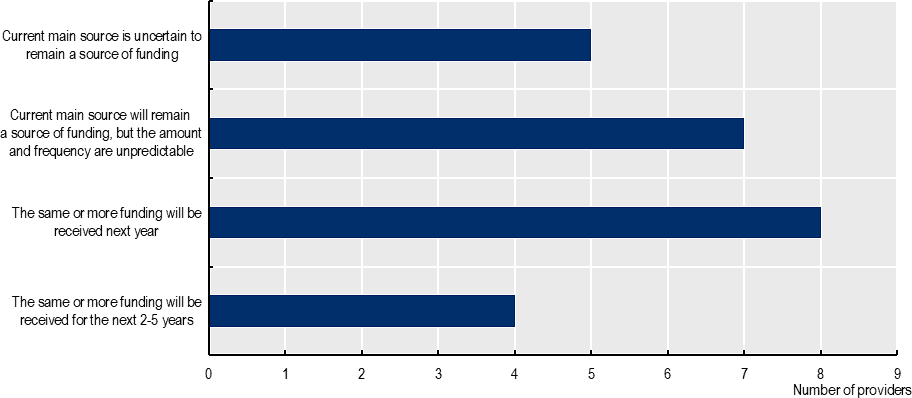

In most of the cases where funding is reported as predictable for at least one year into the future, the government is the primary provider of funds. Only four providers in the OECD Consultation 2022 report that their main source of funding is secure for the coming 2‑5 years. In these cases, the main funder is the government. A further eight providers in the OECD Consultation 2022 are reassured by predictable funding from their main source for the following year (Figure 6.4). Conversely, in three out of the four cases where the main sources of funding came from outside of government (private/corporate funding, charitable trust or internal fundraising), that source of funding is uncertain.

Figure 6.4. Less than half of respondents report that their main source of funding is secure in the coming year(s)

Note: The share of each main funding source of the total budget ranged from 1‑20% to 81‑100%. Three respondents are excluded due to lack of data.

Source: 2022 OECD Consultation with Non-Governmental Service Providers serving GBV Victims/Survivors (Chapter 1, Box 1.5).

Governments can help by protecting funding for non-governmental organisations working to combat IPV. Budgets can be designed to support cross-sector co‑ordination. Lessons can be drawn from the United Kingdom, for example, which recently implemented funding rules to boost investment in mental health services. The funding rules places conditions on re‑financing by central or subnational governments and aims to better ensure continuity and coherence of planning from the top-down. Such provisions have the potential to be effective in the context of gender-based violence, too (Box 6.5).

Box 6.5. NHS England’s mental health investment standard

The National Health Service (NHS) in England introduced a “mental health investment standard” (MHIS) in 2015‑16, to encourage increased spending on mental health services, year-on-year. Since most local mental health funding is not ring-fenced each local NHS Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) determines its own mental health budget from its overall funding allocation. To ensure that (at least nominal) funding for local mental health services increase year-on-year, the MHIS requires that all CCGs in England increase their planned spending on mental health services by a greater proportion than their overall increase in budget allocation that year.

Figures from NHS England’s Mental Health Dashboard indicate that the measures have been able to show some successes. The Dashboard provides a national and local overview of spending on mental health services. It is promising that 2020‑21 was the first year when all CCGs met the MHIS in 2020‑21 (for instance, only 81% of CCGs achieved the Standard in 2015‑16). In 2020‑21, local CCGs spent GBP 12.1 billion on mental health, learning disability and dementia services in England, up from GBP 9.1 billion in 2015‑16. In 2020‑21, this was 14.8% of the total funding allocated to CCGs for health services, up from 13.1% in 2015‑16.

The NHS has also included further spending commitments in its long-term plan. These include a ring-fenced investment fund worth at least GBP 2.3 billion a year by 2023‑24.

Source: OECD QISD-GBV, 2022 (Annex A); (NHS England, 2022[34]; NHS North East London, 2021[35]).

6.5.2. Potential savings from integration require committed investment

Lack of predictable funding streams and the associated difficulty with strategic planning means that co-location, integrated delivery and collaborative strategy often requires targeted funding for that express purpose. Non-governmental providers have a lot to gain financially from co‑ordination with other organisations – not only can co‑ordination help improve the quality and quantity of service provision, it can also offer efficiency gains and cost saving.

For instance, multi-lease arrangements can be more affordable as a result of space‑sharing, thereby making these service hubs less vulnerable to fluctuations in funding. Shared workspaces can allow for a redistribution of operational costs through shared infrastructure, such as conference rooms and office equipment, as well as resources, such as community partners and volunteers (Kurpa et al., 2021[36]; Skinner and Rosenberg, 2006[33]). Some countries, such as Denmark, have started initiatives with targeted funding that aims to encourage a move towards integration and co-location (Box 6.6), but there is scope for more strategic action by other countries in this area.

Box 6.6. Denmark invests in integrated service delivery with non-governmental providers

Denmark has funded a new model with integrated services aimed at prevention (Chapter 1, Box 1.3) and in 2020, Denmark allocated DKK 14.5 million (around EUR 1.95 million) to an intervention-model aimed at providing early and preventive contribution against violence in intimate relations. The model consists of a collaboration between the police, the municipality and a non-governmental organisation. When the police respond to calls of domestic disturbances or violence, they will attempt to motivate the persons involved into starting an ambulatory treatment programme at the NGO in collaboration with the municipality. An early evaluation showed that the model helped secure an earlier response to violence in intimate relations (OECD QISD-GBV, 2022).

Denmark will also provide further support to the non-governmental unit against violence, Lev Uden Vold (Live without Violence), to establish cross-sector partnerships. Lev Uden Vold is to use the new funding running until 2024 to establish partnerships with staff in other sectors, such as the police and health care workers, which interact with victims of violence in intimate relations or perpetrators of such violence (Chapter 1, Box 1.3). The goal is to give the staff in partner sectors relevant tools to identify and help victims of violence in intimate relations or perpetrators of such violence (OECD QISD-GBV, 2022).

References

[32] Baffsky, R. et al. (2022), ““The real pandemic’s been there forever”: qualitative perspectives of domestic and family violence workforce in Australia during COVID-19”, BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 22/337, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07708-w.

[6] Baker, L. et al. (2015), An Intersectional Model of Trauma for Service Providers, VAW Learning Network, https://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/our-work/issuebased_newsletters/issue-15/Issue%2015Intersectioanlity_Newsletter_FINAL2.pdf.

[2] Beyer, K., A. Wallis and L. Hamberger (2015), “Neighborhood Environment and Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review”, Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, Vol. 16/1, pp. 16-47, https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013515758.

[29] CACP (2016), National Framework on Collaborative Police Action on Intimate Partner Violence, CACP, https://cacp.ca/news/national-framework-on-collaborative-police-action-on-intimate-partner-violence.html.

[16] Centre for Social Justice (2022), No honour in abuse: harnessing the health service to end domestic abuse, Centre for Social Justice, https://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/CSJ-No_honour_in_abuse-1.pdf.

[20] Council of Europe (2022), Mid‑term horizontal Review of GREVIO baseline evaluation reports, Council of Europe, https://rm.coe.int/prems-010522-gbr-grevio-mid-term-horizontal-review-rev-february-2022/1680a58499.

[5] Council of Europe (2011), Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence “Istanbul Convention”, Council of Europe, https://rm.coe.int/168008482e.

[23] Department for Work and Pensions (2019), Increased jobcentre support for women experiencing domestic abuse, Department for Work and Pensions, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/increased-jobcentre-support-for-women-experiencing-domestic-abuse.

[13] Domestic Abuse Commissioner (2021), Huge lack of specialist support for LGBT+ victims, Domestic Abuse Commissioner, https://domesticabusecommissioner.uk/huge-lack-of-specialist-support-for-lgbt-victims/.

[1] Faller, Y. et al. (2018), “A Web of Disheartenment With Hope on the Horizon: Intimate Partner Violence in Rural and Northern Communities”, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Vol. 36/9-10, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518789141.

[3] Forsdick-Martz D., S. (2000), Domestic violence and the experiences of rural women in east central Saskatchewan, Domestic violence and the experiences of rural women in east central Saskatchewan, http://www.pwhce.ca/pdf/domestic-viol.pdf.

[27] Hestia (2020), Domestic abuse in lockdown, Hestia, https://www.hestia.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=b9974339-2982-40de-ac88-ed8a0de9a305.

[24] Home Office (2022), Domestic abuse: draft statutory guidance framework, Home Office, https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/domestic-abuse-act-statutory-guidance/domestic-abuse-draft-statutory-guidance-framework.

[15] Htun, M. and S. Weldon (2018), The Logics of Gender Justice: State Action on Women’s Rights, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108277891.

[36] Kurpa, D. et al. (2021), “The Advantages and Disadvantages of Integrated Care Implementation in Central and Eastern Europe – Perspective from 9 CEE Countries”, International Journal of Integrated Care, Vol. 21/4, https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5632.

[8] Marchbank, B. (2020), Making Sense of a Global Pandemic: Relationship Violence & Working Together Towards a Violence Free Society, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/nevr/.

[26] Ministry for Equality (2021), Protocolo de actuación en la Farmacia Comunitaria ante la violencia de género, Ministry for Equality, https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/sensibilizacionConcienciacion/campannas/otroMaterial/farmacias/docs/Protocolo-de-Actuacion-en-la-Farmacia-Comunitaria-ante-la-violencia-de-Genero-nueva-imagen.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2023).

[9] Mundy, T. and N. Seuffert (2021), “Integrated domestic violence services: A case study in police/NGO co-location”, Alternative Law Journal, Vol. 46/1, pp. 27-33, https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969X20984598.

[34] NHS England (2022), NHS mental health dashboard Q4 2020/21, NHS England, https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-mental-health-dashboard/.

[35] NHS North East London (2021), The Mental Health Investment Standard, NHS North East London, https://northeastlondon.icb.nhs.uk/news/publications/the-mental-health-investment-standard/.

[21] OECD (2020), Taking Public Action to End Violence at Home: Summary of Conference Proceedings, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/cbff411b-en.

[30] OECD (2015), Integrating Social Services for Vulnerable Groups: Bridging Sectors for Better Service Delivery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264233775-en.

[10] Pauktuutit (2019), Study of Gender-based Violence and Shelter Service Needs across Inuit Nunangat, Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada, Ottawa, https://www.pauktuutit.ca/wp-content/uploads/PIWC-Rpt-GBV-and-Shelter-Service-Needs-2019-03.pdf.

[4] Peek-Asa C., W. (2011), “Rural disparity in domestic violence prevalence and access to resources”, Journal of Women’s Health, Vol. 20/11, pp. 1743-1749, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2011.2891.

[22] PostEurop (2020), Czech Post - Postal workers and couriers could be close to domestic violence cases, https://www.posteurop.org/showNews?selectedEventId=37470.

[25] Potter, L. and G. Feder (2017), “Domestic violence teaching in UK medical schools: a cross-sectional study”, The Clinical Teacher, Vol. 15/5, pp. 382-386, https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12706.

[11] Roland, N. et al. (2022), “Violence against women and perceived health: An observational survey of patients treated in the multidisciplinary structure ‘The Women’s House’ and two Family Planning Centres in the metropolitan Paris area”, Health and social care in the community, https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13797.

[17] Safety4Sisters (2020), Locked in abuse, locked out of safety, https://www.safety4sisters.org/blog/2020/10/19/locked-in-abuse-locked-out-of-safety-the-pandemic-experiences-of-migrant-women.

[28] Samardzic, T. and M. Morton (2020), A Bucket Under all of the Crack: The Value of Violence Against Women Shelters, University of Guelph, Guelph, https://daso.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/The-Value-of-Shelters-Final-Report_FINAL.pdf.

[31] Schreiber, V., A. Maercker and B. Renneberg (2010), “Social influences on mental health help-seeking after interpersonal traumatization: a qualitative analysis”, BMC Public Health, Vol. 10/634, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-634.

[33] Skinner, M. and M. Rosenberg (2006), “Managing competition in the countryside: Non-profit and for-profit perceptions of long-term care in rural Ontario”, Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 63/11, pp. 2864-2876, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.028.

[18] Sylaska, K. and K. Edwards (2014), “Disclosure of Intimate Partner Violence to Informal Social Support Network Members”, Trauma, Violence & Abuse, Vol. 15/1, pp. 3-21, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26638329.

[14] UN Women (2020), Intensification of efforts to eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls, https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/07/a-75-274-sg-report-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls.

[7] UN Women (2019), The value of intersectionality in understanding violence against women and girls, UN Women, https://eca.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2019/10/the-value-of-intersectionality-in-understanding-violence-against-women-and-girls.

[12] UN Women (2012), Handbook for National Action Plans on Violence against Women, UN Women, https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2012/7/handbook-for-national-action-plans-on-violence-against-women.

[19] World Health Organization and Pan American Health Organization (2012), Understanding and addressing violence against women, World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/77432.

Note

← 1. The Explanatory Report defines those made vulnerable by particular circumstances as “pregnant women and women with young children, persons with disabilities, including those with mental or cognitive impairments, persons living in rural or remote areas, substance abusers, prostitutes, persons of national or ethnic minority background, migrants – including undocumented migrants and refugees, gay men, lesbian women, bi-sexual and transgender persons as well as HIV-positive persons, homeless persons, children and the elderly” (Council of Europe, 2011[5]).