Gender-based violence (GBV) and intimate partner violence (IPV) often escalate over time. Early and preventative interventions are therefore critical to limiting harm. Co‑ordination across service providers can ensure that women undergo appropriate danger assessments and receive adequately tailored support, and that perpetrators are consistently held to account to prevent violence from escalating. Unfortunately, stigma, distrust of public authorities, and other factors mean that many women only report their perpetrators and seek help when their relationship reaches the point of crisis. At this point, it is crucial that crisis response teams provide accessible services and can refer victims/survivors to co‑ordinating partners for rapid intervention to save lives.

Supporting Lives Free from Intimate Partner Violence

2. Preventing violence from taking root: Integrated services from prevention to crisis support

Abstract

Key findings of this chapter

Intimate partner violence (IPV) often escalates over time, which makes timely and effective intervention key to limiting exposure to prolonged and/or increasing severity of violence. This chapter takes stock of how countries use integrated services to achieve as early intervention as possible, and to provide timely and effective interventions as soon as women report their perpetrators. This chapter finds that:

Barriers to reporting IPV are high, making it too challenging for many women to report their partners and/or seek help. Understanding these barriers is one step towards being able to lower them.

One way for countries to combat gender-based violence (GBV) against women is to focus prevention efforts on highlighting sexist acts and behaviour resulting from harmful gender norms that may not qualify as severely enough to be classified as violence under the Istanbul Convention, but that can be precursors for later GBV and IPV. Countries should also aim to speed up society-wide normative changes that support gender equality and nonviolence.

When victims/survivors overcome reporting barriers, the degree of danger they face should be appropriately assessed. Risk assessments tend to be most accurate when they are well-co‑ordinated and standardised across agencies and providers. Service provision – especially for high-risk cases – works well when it is co‑ordinated through case management and/or MARACs since these can help agencies share relevant information about the case and victims/survivors to navigate complex systems and access appropriate services at the right time.

Preventative measures need to target perpetrators of IPV in order to achieve holistic and sustainable solutions to violence. Violent men are often re‑offenders in multiple relationships and victims/survivors sometimes return to their abusers, so working with perpetrators is crucial to prevent re‑victimisation and new victimisation. Information-sharing across different actors within the justice sector as well as across different sectors would contribute to making measures more effective.

Reporting often first occurs at a point of crisis, so initial points of contact with crisis and emergency services crucially need to offer effective referrals to partners to keep victims/survivors safe in an emergency. Two cornerstone sources of crisis support are telephone helplines and crisis centres, and these work best when they have established partners and immediately applicable referrals.

2.1. Partner violence often escalates over time, making timely intervention key

Intimate partner violence (IPV) often escalates in frequency and/or severity over time (Kebbell, 2019[1]). Abusers may escalate their violence, for example, if they feel that they no longer have control or worry that their partner is preparing to leave the relationship (National Domestic Violence Hotline, 2022[2]). Women exposed to escalating violence may find themselves in increasingly precarious situations where earlier intervention could have prevented harm.

This chapter takes stock of how countries use integrated services to achieve as early intervention as possible, and to provide timely and effective interventions as soon as women report their perpetrators. It first discusses how barriers to reporting are particularly problematic in cases of escalating violence, making early intervention key to limit the length of time and severity of violence from partners. Second, the chapter describes the value of co‑ordinating services through case management and risk assessment, to ensure that the risks of the occurrence and escalation of violence are not underestimated. Third, it discusses how interventions can incorporate the treatment of perpetrators to ensure that the intervention is holistic and sustainable. Finally, the chapter explains that effective and integrated cornerstone services such as emergency helplines and crisis centres are essential to give immediate assistance as a first stop when women do report.

2.1.1. Barriers to formal reporting can enable violence to escalate

Leaving an abusive relationship is difficult and often takes months or years. Some victims/survivors stay with (or return to) their abuser because they find value in other aspects of the relationship. They may miss aspects of their life they shared with their abuser, such as their children, their social circles, their home, or their pets. They might be able to compartmentalise the violence as only one facet of an otherwise tolerable or enjoyable relationship (Patrick, 2021[3]). Many are highly committed to achieving a non-violent relationship, are emotionally attached, and think that things may change in future (Nicholls et al., 2013[4]).

But inadequate public supports for victims/survivors can also make it harder for women to leave a relationship. Not least because violence tends to escalate over time, it is critical for service providers to understand and lower barriers to reporting violence.

Across countries, there are widespread problems with under-reporting of GBV and IPV (UN Women, 2022[5]). Violence goes unreported for various reasons, including (but not limited to) financial dependence on the abuser, stigma, a lack of social and formal support networks, not believing that the legal system (including police) will work with the victim/survivor, and a fear that the perpetrator might retaliate or take away children (Marchbank, 2020[6]). In a cross-national survey of victims/survivors in the European Union,1 on average 9% of victims/survivors reported not contacting the police after their most serious incident of physical and/or sexual violence because they felt that the police would not believe them. 7% believed that they did not think the police could do anything, and 4% felt they would not be believed (Chapter 5).

Interviews conducted by a legal advocacy group in Canada illustrate the apprehension of the time, money and mental investment required to report perpetrators. One victim/survivor respondent illustrates the burden of reporting sexual assault made worse by their concern with being met by disrespect by the justice system: “I don’t have the time or the energy to have somebody treat me like I’m dumb or question my motivations” (Prochuk, 2018[7]).

Women are most likely to report violence and seek support from public services when violence becomes unbearable or when they fear for their lives (Barrett, 2011[8]; Barrett, Peirone and Cheung, 2020[9]; Fanslow and Robinson, 2010[10]). This finding is supported in diverse cultural contexts. For instance, a study from the Czech Republic indicates people are more likely to report IPV when it is perceived as more severe, and especially when there is a fear that the victim’s life is in danger. At the same time, the likelihood of reporting to police is lower for sexual assaults compared to non-sexual forms of physical violence, perhaps because stigma around sexual assaults is more prevalent than for non-sexual acts of violence (Podaná, 2010[11]). A study in India finds that women were most likely to report spousal violence (albeit still rarely to formal institutions) when they experienced it in multiple forms: sexual, physical and emotional abuse (Leonardsson and San Sebastian, 2017[12]). Similarly, research in Korea finds that women are most likely to initiate help-seeking from formal institutions when they experience violence‑related injuries or the perpetrator abuses their child (Kim and Lee, 2011[13]).

Women facing multiple and intersectional disadvantages may find it harder to report and seek help (Chapter 6). The ease with which women feel able to report their crime can be influenced by factors like citizenship status, language fluency, financial means, employment status, overall physical and mental health and parental status (Marchbank, 2020[6]). Historical tensions also exist between police and marginalised populations that could make people less inclined to seek help from these formal institutions. Members of Black, Indigenous or other ethnically marginalised communities, as well as sex workers, members of the LGBTI+ community, and homeless women may be hesitant to seek help due to negative past experiences with formal institutions, and especially the police (Mundy and Seuffert, 2021[14]; OECD, 2020[15]).

2.1.2. Prevention measures should target sexist acts as precursors to gender-based violence

Prevention and early intervention are key strategies to avoid escalating violence and critical moments of crisis. Indeed, GREVIO – the monitoring arm of the Istanbul Convention – stresses the importance of measures and policies targeting any sexist act, and not only measures targeted at helping women in crisis (Council of Europe, 2022[16]). For example, the 2015 amendment to the French Labour Code does this well in that it prohibits any act related to a person’s sex where the purpose or effect is to violate the dignity or create an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment (Council of Europe, 2022[16]). Awareness-raising and sensitising among the public, firms and public institutions can speed up the ongoing progress toward more gender-equal cultures and norms.

Measures targeting early stages of violence, toxic masculinities and negative social norms are useful because they target gender‑based behaviours that may not reach the threshold of severity that would be classified as violence under the Istanbul Convention. These behaviours are useful to address in themselves, but also because they often are the precursors to violence and manifest the structural gender inequalities that in many cases are the foundation for more severe forms of violence against women (Council of Europe, 2022[16]). Similarly, the Council of Europe’s work on addressing GBV among young people highlights a range of preventative and early intervention efforts, including training professionals, educating children and young adults, and raising public awareness, as critical to addressing the root causes of GBV (Box 2.1) (Pandea, Grzemny and Keen, 2019[17]).There are few evaluations from OECD member countries on how well preventative programmes and pilots work to address GBV against women. It is therefore encouraging that the UK Home Office has committed to invest GBP 3 million in 2022‑23 towards programmes that improve the understanding on what works to prevent violence against women and girls (UK Home Office, 2022[18]).

Box 2.1. Addressing deep-seated gender inequality is key to combatting gender-based violence

GBV and IPV against women need to be considered in the context of the historically unequal relationship between men and women in society. This form of violence is rooted in pervasive gender inequality, discrimination and harmful cultural norms that benefit men over women. Both the driving cause and motivation behind GBV against women is for a man to exert power and control over a woman. This can involve one or several aspects of a woman’s life, including her body, her mind, her economic situation, her sexuality and/or her reproductive functions. As such, GBV is part of a social mechanism that keeps women in a subordinate position to men.

To end gender-based violence, there need to be sustained efforts to address society-wide gender inequalities and traditional gendered norms. Societal acceptance of these harmful traditional gender norms helps perpetuate cycles of violence. Preventative measures should aim to empower women and combat gendered norms in order to achieve longer-term attitudinal changes. An important part of this work will involve work with boys and men to sensitise them to GBV and provide tools to help perpetrators use non-violent forms of communication.

Importantly, any preventative efforts targeting gender-based violence must be accompanied by a comprehensive and holistic effort to ensure gender equality in education, employment, political life, and society at large – to ensure that women are participating on an equal playing field in all walks of life.

2.1.3. Promoting gender equality through society-wide normative change

Eradicating IPV is often framed as a responsibility of women to escape violent relationships, but at the societal level there is nothing that is more important than addressing the harmful norms that perpetuate violence. Violence has become embedded in the socialisation of children, and perhaps especially in boys and young men. Violence represents a prominent element of the coming-to-be of patriarchal masculinities to varying degrees across cultures (Box 2.1) (UN Women, 2016[25]; Pappas, 2019[26]; OECD, 2020[27]).

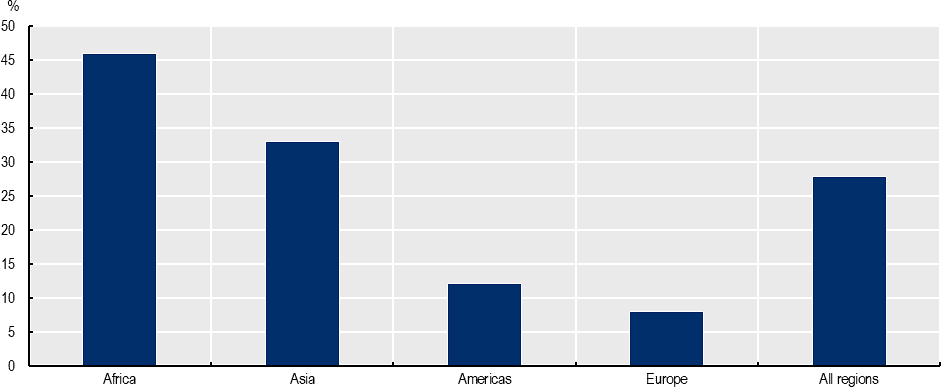

Internalised harmful gendered norms means that some men and women are able to justify violent behaviour. Indeed, many women accept that violence can be justified behaviour in certain circumstances: over one‑quarter of women think IPV can be justified across countries in the world (Figure 2.1). The acceptance of IPV is more common in countries in Africa where 46% of women on average think that husbands can be justified in beating their wives, compared to in European countries where only 8% of women think so (Figure 2.1). It is important to challenge and transform the harmful social norms that justify IPV into ones that promote gender equality and nonviolence (OECD, 2020[27]).

Figure 2.1. Over one‑quarter of women across world regions think IPV can be justified

Note: Data illustrate the share of women who think husbands are justified in hitting or beating their wives for at least one of the specified reasons, including if she burns the food, argues with him, goes out without telling him, neglects the children or refuses sexual relations. Regional averages refer to simple (unweighted) averages over countries.

Source: (OECD, 2019[28]), OECD Gender, Institutions and Development Database (GID-DB), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=GIDDB2019.

It is critical to target social norms among both men and women that historically have played a role in normalising violence, creating stigma against speaking out, and allowing violence to be perpetuated in society. In practice, such norms take shape in practices such as victim-blaming, the internalised acceptance of domestic violence by women themselves, and inadequate response by law enforcement agencies. Victim-blaming attitudes contribute to sustaining a climate of tolerance that discourage actions to combat IPV and allows social indifference.

Restrictive norms of masculinities, such as belief in the male breadwinner mode, or the idea that important decisions – such as matters of financial, sexual or reproductive nature – should be taken by men, foster a culture of power imbalances in heteronormative couples. Challenging these norms, or the feeling that these norms are being challenged, can also initiate and exacerbate IPV. For example, men who report being stressed due to lack of work, or who report feeling ashamed about their financial or economic situation, are almost 50% more likely to commit violence against their female partner than those who do not report feeling stressed (OECD, 2021[29]). Such financial and other stressors can become more prevalent in economic crises, such as that experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stress and other factors can provide false justification or excuses for violence in the minds of both victims/survivors and perpetrators, and discourage disclosure or intervention.

Stopping violence against women needs to start well before the onset of a perpetrator’s violent behaviour. Most behaviours are learned in early childhood and it is very hard to undo violent tendencies, as was established in the UK’s public consultation Violence Against Women and Girls Call for Evidence in 2020 (UK Home Office, 2022[18]; UK Home Office, 2020[30]).

Although the OECD QISD-GBV 2022 (Annex A) did not ask specifically about country interventions and sensitising men and boys from a young age, some examples have emerged. For example, the Government of Japan reported dedicating 33 million yen to early prevention programming in school education in 2022. Specifically, thematic textbooks have been created to raise awareness and prevent children from becoming perpetrators, victims or spectators to sexual assault over the life course. In addition, utilising the textbooks, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology has launched a project that accumulates guidance examples (OECD ISD-GBV, 2022). Similarly, in 2022, the Spanish Government Office against GBV allocated 6.5 million euros in subsidies and grants to raise awareness and prevent GBV, including programmes to raise awareness and prevent digital GBV or centred in working masculinities with young boys and teenagers (Ministry for Equality, 2022[31]).

A third example can be taken from Costa Rica, where the National Policy for the Care and Prevention of Violence against Women of All Ages Costa Rica 2017-2032 (PLANOVI) has a considerable focus on promoting an anti-sexist culture and masculinities for gender equality and anti-violence (Alonso and Valverde, 2017[32]).

At the international level, strategies promoted by UN Women to achieve sustained normative changes include focussing on early education, working with men and boys, supporting advocacy, awareness-raising, community mobilisation, legal and policy reforms. One example of this is the NGO Equimundo in Brazil that focuses on engaging men and boys as allies in gender equality, by working to promote healthy manhood and violence prevention (Equimundo, 2022[33]). Equimundo has also launched a Global Boyhood Initiative in several countries, including the UK, to help foster healthy and inclusive norms among boys (Equimundo, 2023[34]).

2.2. Co‑ordinating services can ensure that risk is appropriately assessed

Too often, tragedy strikes when early warning signs are overlooked or minimised, and violence subsequently escalates. Co‑ordinated risk assessments and case management can be valuable tools to help ensure that the risk of violence is appropriately assessed, and that adequate services are then provided to the help-seeker.

2.2.1. Risk assessments are a key preventative tool, especially if co‑ordinated well

Cases of IPV need to be adequately assessed for risk by service providers so that immediate risk can be reduced, a safety plan can be developed, and the appropriate services and/or referrals can be provided (Roeg, Hilterman and van Nieuwenhuizen, 2022[35]; Council of Europe, 2011[36]). Often categorised as “danger assessments” (Campbell, Webster and Glass, 2009[37]), risk assessments aim to establish the degree of threat an abuser poses, produce transparent and defensible indicators for intervention and treatment decisions, and be informative for providing the services required to help prevent further IPV to those who need it most (Nicholls et al., 2013[4]; Northcott, 2012[38]).

Risk assessment tools may consider the perpetrator and their likelihood to re‑offend, while others may consider the victim and their likelihood of re‑victimisation. In other words, some tools are designed to predict recidivism, while others focus on violence prevention and risk management – and some do both (Northcott, 2012[38]). Risk assessment tools are most commonly used by justice agencies such as police and courts, though their use has been adopted by social workers addressing both victims and perpetrators, by health professionals, and staff in shelters and related protection centres (EIGE, 2019[39]).

IPV risk assessments can be deployed following three general approaches: (i) unstructured clinical judgment; (ii) structured clinical judgment; and (iii) the actuarial approach (Northcott, 2012[38]; EIGE, 2019[39]).

Unstructured clinical judgement, also known as clinical enquiry, is an informal method employed by service providers assessing risks related to IPV (WHO, 2013[40]). Using this method, professionals such as police, social workers and health care workers do not use official guidelines, but instead use information collected through conversation and make a subjective judgement about the threat posed in the current situation. Without proper training about IPV and its various, context-specific aggravating factors, service providers may not be able to assess risk accurately.

Structured clinical judgement, also known as guided clinical approach, follows a set of guidelines describing specific, minimum risk factors associated with IPV. It subsequently provides recommendations about information gathering to inform safety planning, risk management and case management (Northcott, 2012[38]; EIGE, 2019[39]). Structured clinical judgement is therefore more consistent and transparent than unstructured clinical judgments (Northcott, 2012[38]). For an example of a structured clinical judgement tool, see Box 2.2.Structured clinical is more flexible than third risk assessment method, the actuarial approach (EIGE, 2019[39]).

Actuarial risk assessments incorporate a value scale for each of the items in the assessment inquiry and use an algorithm to then generate a “score” used to assess risk. On the one hand, the actuarial approach provides a standardised method for assessing risk, which can be methodically deployed by professionals who may not necessarily be trained in addressing cases of IPV. Because risk here is based on set criteria, results are perceived as more reliable and can be easily replicated across settings. On the other hand, the actuarial approach limits professionals to a fixed set of criteria that may not accurately capture context-specific or intersectional risk factors, or may underestimate dynamic factors which may change the level of risk beyond the time of assessment (Northcott, 2012[38]; EIGE, 2019[39]). This can lead providers to underestimate risk and refer the help-seeker to inadequate services. For an example of an actuarial risk assessment tool, see Box 2.2.

Among OECD countries in the European Union, a majority have developed or endorsed specific risk assessment tools at the national level to encourage standardised implementation (Table 2.1 and Box 2.2). In the United States and Canada, subnational governments have done the same, and in Australia, subnational governments may develop their own frameworks in conjunction with national risk assessment principles for domestic violence (Toivonen and BackHouse, 2018[41]).

Box 2.2. Structured clinical approach versus actuarial approach to risk assessment in the OECD

Spousal Assault Risk Assessment Guide (SARA)

SARA is cited as one of the most commonly-deployed structured (or guided) clinical approaches to assessing risk in situations of IPV. It was developed by scholars to measure the level of risk through non-actuarial, professional judgement guided by a 24‑item framework, though an abridged version was developed in parallel (the Brief Spousal Assault Form for the Evaluation of Risk, B-SAFER). The guide has since been updated on three occasions to keep up with IPV research, most recently in 2015. SARA, as well as B-SAFER, have been adopted by providers, and have been cross-validated for predictive accuracy, in a number of countries in the OECD.

The tool guides practitioners through items related to the nature of abuse, perpetrator factors and victim vulnerabilities. Importantly, SARA requires that professionals are properly trained to assess situations of IPV, have access to all relevant information, including clinical and justice sector files, and for both victims and perpetrators participate in interviews.

Ontario Domestic Assault Risk Assessment (ODARA)

ODARA is a commonly deployed actuarial approach to assessing risk of recidivism in situations of IPV in Canada. It was first developed in Ontario, Canada, using police data which was collected from over 500 known IPV offenders over five years. ODARA gained currency in Canada in the early 2000s and has been adopted on the ground – and cross-validated in studies – across the OECD.

The tool focusses on predicting whether a perpetrator will reoffend based on statistical analysis of 13 items. Each item is assigned a value of zero (“no”) or one (“yes”), and level of risk is determined by the sum of values across 13 items, including, for instance, prior domestic or non-domestic assault in police records, victim/survivor fear of future assaults and if victim/survivor is facing barriers to support such as lack of resources or geographical isolation. Although it can be helpful to quantify risk on a scale, some scholars argue that lower mid-range scores are “a point of ambiguity” which may require additional or complementary risk assessment approaches, including professional judgement facilitated through structured or unstructured means. Indeed, one survey of Canadian police officers nationwide found that one‑third of police officers use more than one tool when assessing cases of IPV for risk.

Source: for SARA (EIGE, 2019[39]; Northcott, 2012[38]; The Risk Management Authority Scotland, 2019[42]) and for ODARA (Hegel, Pelletier and Olver, 2022[43]; Saxton et al., 2020[44]; GR Counselling, 2005[45]; Waypoint, 2021[46]).

Table 2.1. Many countries have risk assessment tools standardised at the national level

Main actors of risk assessment and risk management, and level of standardisation

|

Country |

Main actors of risk assessment and risk management |

Regulated and/or standardised at national level |

|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

Police, intervention/violence protection centres, justice system, health professionals in hospitals, men’s counselling centres |

Yes for police and intervention/violence protection centres |

|

Belgium |

Police, social workers, health professionals, public prosecutors |

No |

|

Czech Republic |

Police, victim support centres |

Yes |

|

Denmark |

Police, social services |

Yes, the police have a risk-assessment guide |

|

Estonia |

Police, probation services, victim support services, social services (child protection, social workers), NGOs |

Yes |

|

Finland |

Police, social services, health services, victim support centres |

Yes |

|

France |

Victim support centres, health services |

No |

|

Germany |

Police, specialised counselling services, victim support centres, perpetrator programmes, women’s shelters, youth welfare agency, social workers, law-enforcement agencies |

No |

|

Greece |

Victim support centres, NGOs, police |

No |

|

Hungary |

National Crisis Management and Information Telephone Service, crisis centres, secret shelters, transitional housing services, crisis management clinics, victim support centres. Also through a signalling system which mandates reporting (for some members by law) across a range of sectors, including (but not limited to) health care service providers, the police, the public prosecutor's office, the Court of Law, probation services, victim support as well as compensation organisations, correctional institutions, and children's rights representatives. |

Yes, legal and/or uniformly used professional protocols (by type of institution) |

|

Ireland |

Police, probation services, health professionals, social services |

Yes |

|

Italy |

Police, law-enforcement agencies, victim support centres, perpetrator programmes, emergency departments, judiciary |

No |

|

Latvia |

Police, social departments, victim support centres |

No |

|

Lithuania |

Police |

Yes |

|

Luxembourg |

Police, public prosecutor, victim support centres, service in charge of perpetrators |

No |

|

Netherlands |

Victim support centres, health professionals, law-enforcement, child protection, social workers |

Yes |

|

Poland |

Police, social services, health professionals, education professionals, victim support centres |

Yes |

|

Slovak Republic |

Police, victim support centres |

Yes |

|

Slovenia |

Police, social workers, victim support centres, NGOs working with perpetrators |

Yes |

|

Spain |

Police, victim support centres, forensic assessment units inside institutes of legal medicine and forensic sciences, prison and probation services. Viogén System is a web application that integrates all information of interest in specific cases to make a risk estimation, monitor the case, provide protection and a “Personal Safety Plan”, and carry out preventive steps by issuing warnings to the different institutions involved. |

Yes |

|

Sweden |

Police, social services, prison and probation services, victim support centres |

Yes |

|

Türkiye |

Police, gendarmerie, social services |

Yes |

|

United Kingdom |

Police, victim support centres |

Yes |

Source: Table excerpted and edited from (EIGE, 2019[39]) “Risk Assessment and Management of Intimate Partner violence in the EU”. Additional country comments incorporated following OECD member country feedback.

Once a risk assessment is made, service providers must determine the best course of action to manage risk for women experiencing IPV. The EIGE contends that multiagency arrangements for risk management are most effective, citing multi‑agency risk-assessment conferences (MARACs) as a prominent example.

As with many other public responses to intimate partner violence, however, risk assessments face challenges in implementation. The European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) highlights how little empirical evidence exists to evaluate the accuracy and effectiveness of risk assessment tools and related risk management practices (EIGE, 2019[39]). Scholars have also cited the inconsistent application of various tools across different frontline responders and service providers (Kebbell, 2019[1]; Roeg, Hilterman and van Nieuwenhuizen, 2022[35]). There is the persistent challenge of ensuring that victims/survivors are linked up with adequate service provision and protection after a risk assessment is made.

Finally, for any of these risk assessments, time is of the essence: a process that takes too long can leave women in severe danger of an escalation of violence.

2.2.2. Co‑ordinating services through case management gives victims/survivors a lifeline

The landscape of possible services available to victims/survivors of IPV is often complex and hard to navigate – from locating a provider and getting the right referrals, to applying for services, and finally accessing services for which they are eligible. Navigating complex systems can be especially difficult for women who might have experienced traumatic brain injuries, mental health issues, long-term stress and psychological trauma, including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This makes cognitive function more challenging (Valera et al., 2019[47]).

Case management services can help women find and receive the support they need from the system, and they are a common tool for service integration, along with referral systems, physically co-located services and data sharing (Chapter 1). Most OECD countries have systems where experts help women navigate support systems through case management.

Case management services focused on IPV are often established and operated by non-governmental providers specialised in supporting victims/survivors of violence, especially where they take a lead on offering as many services as possible for help-seeking women (Chapter 6). In many of the ISD examples presented in this report, caseworkers play a prominent role, which can improve the experience for clients – though it can be very challenging for a single caseworker.

As the chapters in this report illustrate, many national and local governments in OECD countries have partnered with local non-governmental providers on the ground to build up a case management infrastructure. In Estonia, for example, the Government has partnered with local service providers to assign case co‑ordinators to support women in navigating the help-seeking process. In addition to counselling and emergency shelter, women’s support centres also offer case management services to co‑ordinate supports offered by a variety of partner organisations, including public services, through regular meetings. Case workers create a safety plan which includes a schedule of inter-related activities and, importantly, an agreement on the safe exchange of information between parties (OECD QISD-GBV, 2022, see Annex A).

Similarly, in Australia, a national GBV case management scheme exists. Social workers at Services Australia identify family and domestic violence by applying a risk-assessment model. Social workers at Services Australia provide professional casework to people impacted by family and domestic violence, through support and interventions including referral to external support services. Last year, social workers at Services Australia assisted over 100 000 people experiencing family and domestic violence (OECD QISD-GBV, 2022). Women benefitting from the Keeping Women Safe in their Homes (KWISITH) initiative in Australia (Chapter 4) also benefit from case management support.

2.2.3. MARACs help ensure communication between relevant providers for the highest risk cases

Results from the OECD QISD-GBV 2022 reveal a relatively common and noteworthy regionally or locally deployed case management initiative: multi‑agency risk-assessment conferences (MARACs), or similar case conferences bearing slightly different names (Box 2.3). These meetings are conducted for the most severe cases of GB and bring together relevant police officers, health care workers, public prosecutors, social workers, child welfare providers and case managers, on a regular basis (sometimes weekly), to ensure the long-term safety and continuity of care for clients who are particularly at risk of severe IPV. These are valuable for ensuring that case‑relevant information is shared to promote the stability and security victims/survivors most at risk of serious harm and escalated violence.

Such case conferences are reported to exist in countries like Australia, Austria, the United Kingdom (England, Scotland and Wales), Finland and New Zealand, though service delivery arrangements – such as how frequently they meet and how referral pathways work – may vary in different national and local contexts depending on need and resources. In the United Kingdom, the first MARACs were established over 20 years ago, and although the mechanism is not enshrined in law, it has now been adopted in 260 jurisdictions nationwide. The non-governmental organisation SafeLives UK acts as a steward for the initiative, supporting regional and local authorities to establish or improve MARACs according to pre‑determined standards and guiding principles that place help-seekers at the centre of service delivery (Jaffré, 2019[48]).

A past evaluation of the MARAC initiative across the United Kingdom suggests that “for every GBP 1 spent on MARACs, at least GBP 6 of public money can be saved annually on direct costs to agencies such as the police and health services,” (SafeLives UK, 2010[49]). Respondents to the OECD’s non-governmental provider consultation (Chapter 6) also point out the value of case conferences, albeit under the condition that partners are well-co‑ordinated and take seriously their input. Indeed, participants can more easily take part in MARACs on equal footing when participants see all contributions, including their own, as equally valuable to the GBV case management (Cleaver et al., 2019[50]; Moylan, Lindhorst and Tajima, 2017[51]; Ekström, 2018[52]; Mundy and Seuffert, 2021[14]). For instance, one respondent to the Consultation thought that cross-sectoral case meetings were extremely helpful, but only if representatives from other sectors had the relevant training and interest. To understand better the conditions under which these conferences work, further evaluations to assess clients’ and providers’ outcomes should be conducted.

Box 2.3. MARACs: Multi‑agency risk assessment conferences show promise

Case conferences in Austria increase co‑operation and limit re‑victimisation

MARACs were first piloted in two police districts of Vienna in 2011 with the overarching aim of preventing domestic and family violence through improved, co‑ordinated responses by service providers. The Viennese MARACs were subdivided into two sections: a section for case‑related co‑operation, and a section for structural networking. The first group deals with concrete cases of domestic violence by inviting relevant providers from the police, the Youth and Family Office, and the legal sector together with violence intervention centre staff to meet monthly to discuss cases of repeat and severe violence. The second group is a steering committee involving a broader range of agencies, including the 24‑Hour Women’s Emergency Helpline, the children’s protection centre, women’s shelters, health organisations, counselling services and probation services. This second group serves as a platform for professional exchange and networking and meets once per year with the aim of preventing DFV at the structural level.

In 2014, additional MARAC pilots were launched in several districts of Tyrol and Lower Austria. These more recent pilots are led by the police and meet monthly or bi-monthly depending on the case load.

In addition to MARACs, informal, ad hoc case conferences (MACCs) have been implemented by local violence protection centres. The participating institutions are the same as with MARACs and vary according to cases’ requirements. For example, the Upper Austrian Violence Protection Centre invites the victim (and if necessary an interpreter) to meetings in an effort to promote transparency. In other provinces, violence protection centres invite local public prosecutors and judges in order to improve co‑operation and the acceptance of risk assessments.

Evaluations of the pilots have shown promising results by improving the level of inter-institutional co‑operation. It was found that the Austrian MARACs prevent further victimisation through co‑ordination and joint effort of the organisations involved. A few areas of improvement were identified. Qualifying risk criteria should be standardised to ensure maximal case inclusion and the benefits of MARACs can be promoted within police institutions, to increase police attendance.

Integrated Safety Response in New Zealand de‑escalate violence and improve provider collaboration

In 2016, two family violence Integrated Safety Response (ISR) pilots were launched in Christchurch and Waikato. Like MARACs, ISRs are hosted by Police and bring together service providers from Ministry of Children (Oranga Tamariki), the Department of Corrections, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Social Development, the Ministry of Education, District Health Boards, the Accident Compensation Corporation, local specialist family violence non-government organisations and services that emphasise Maori culture and values (kaupapa Māori services). These multi‑agency interventions aim to provide immediate safety of victims/survivors and children. The ISRs also work with perpetrators to prevent further violence. ISR locations have weekly Intensive Case Management meetings to discuss new episodes of family violence that have been identified as “high risk” during daily Safety Assessment Meetings, to create a joint response plan, and to follow up on previously identified cases that require continued attention and action.

The ISR is supported by a dedicated electronic case management system that tracks tasks and enables information sharing between service providers. This System is updated during regular case meetings and as agencies complete agreed-upon actions in support of families.

Evaluation of the pilots (2017 and 2019) showed that one‑third of included cases had been successfully de‑escalated in terms of risk, and two‑thirds presented no further episodes of violence. A majority of service providers reported improved information sharing (90%) and improved collaborative working relationships (88%).

Service provision has been integrated, with 73% of people that had experienced violence, and 50% of people who used violence, received additional services including access to counselling, legal support, parenting programmes, safety programmes, alcohol and drug programmes, and mental and physical health support.

The evaluations recommended increasing coverage of rural areas, improving responses for children and youths, and improving efficiencies in managing increasing number of referrals.

MARACs are mainstreamed nation-wide in the United Kingdom

The first MARAC in the United Kingdom was organised at the grassroots level in 2003 and was eventually mainstreamed nation-wide by the organisation SafeLives, with government support. Nearly 300 MARACs now exist in every district of England and Wales, with increasing presence in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

MARACs are chaired by local police, with the support of a dedicated co‑ordinator who receives referrals, drafts meeting agendas and ensures follow-up on agreed courses of action. Independent Domestic Violence Advisers (IDVAs) attend the meetings to advocate for the help-seeking individual. They are joined by members of local police, housing authority, health authority and education and child service authority. They regularly convene – sometimes weekly or bi-weekly – to share relevant information about each case, according to the existing data protection protocols established by SafeLives. Together, MARAC participants write tailored action plans for each of the cases, and the IDVA holds the other agencies to account.

In 2021‑22, over 120 000 cases were addressed in the United Kingdom via MARACs; 15.3% of cases involved ethnic minority victims/survivors, 8.5% of cases involved victims/survivors with disability; 6.2% of cases involved a cis-gendered male victim and 1.4% of cases involved victims who identify as LGBTI+.

While these case conferences are meant to address only the most severe cases of domestic and family violence, where individuals may be at risk of serious harm or murder as a result of domestic abuse, this is not always the case in practice. In some places, it is not uncommon for cases that do not meet risk qualification to nonetheless be referred to MARACs as a result of insufficient general services for people experiencing GBV that is not (yet) life‑threatening.

Source: (OECD QISD-GBV, 2022, see Annex A); (Amesberger and Haller, 2016[53]; Joint Venture, 2019[54]; New Zealand Police, 2020[55]; SafeLives, 2022[56]; SafeLives, 2022[57]).

2.3. Managing perpetrators is essential to sustain violence‑free lives

To achieve holistic and sustainable solutions to IPV, services supporting women escaping violence should also integrate perpetrator responses in parallel. Violent men are often re‑offenders who affect the lives of multiple victims/survivors for years. In addition, it is often difficult for women with violent partners to leave their partners completely, especially if they have children together. Working with perpetrators can help prevent further violence and new victimisation.

The immediate response to perpetrators’ violence may come from the justice sector, e.g. the police. Compared to other sectors, such as health or housing, the justice sector is particularly well-placed to interact directly with perpetrators of violence to prevent further violence from occurring (Chapter 5). However, the justice sector alone cannot correct perpetrator behaviours, especially when rates of reporting, prosecution and conviction in the justice system remain low (EIGE, 2019[58]; Garner and Maxwell, 2009[59]).

Perpetrator intervention programmes have sometimes been integrated into broader, integrated systems of accountability and justice, where national standards are developed to consistently hold perpetrators accountable across sectors and systems, including police, courts, corrections, perpetrator offender programs and services, child protection services, community services etc (Australian Government, 2016[60]). The Australian Department of Social Services acknowledges “a strong need for integration and co‑ordination between those services and systems directly intervening with perpetrators, those that support women and their children and those that engage with perpetrators on other issues” (Australian Government, 2016[60]).

Yet more can be done to co‑ordinate across sectors for sustained change and to target the reasons behind violence. Interventions can be initiated at the point when women seek help to promote enduring behavioural change in perpetrators, even if no civil or criminal charges are pursued. This approach can help find holistic solutions in individual cases and also contribute to a norm change that can help reduce the prevalence of IPV on a broader scale.

Drawing on the well-established example of MARACs in the United Kingdom, some scholars have suggested that MARACs offer a good framework for incorporating and monitoring perpetrator responses. Through this lens, MARACs are not only well-suited to offer protection to women experiencing violence; they can also be critical in preventing further violence through more systematic tracking and engagement of perpetrators (Tapley and Jackson, 2019[61]).

Although the 2022 OECD Questionnaire did not ask explicitly about services targeting perpetrators, a number of countries do offer perpetrator-related programming (Table 2.2) – suggesting that this is a policy area receiving increasing attention across countries. Several countries focus on counselling and behavioural interventions.

Table 2.2. Perpetrator-focused responses in the OECD

|

Australia |

The Men’s Referral Service provides national direct telephone and online support for men who are using violent and controlling behaviour. No To Violence, which provide the Men’s Referral Service, received additional funding during the onset of COVID‑19. In 2021-22, the Men’s Referral Service provided support to over 7 000 contacts. |

|

|

Austria |

A number of Counselling Centres for Violence Prevention have been established for help-seeking perpetrators of violence, in addition to related, regional men’s counselling centres. Perpetrators of violence are legally obligated to receive counselling where restraining or barring orders are issued. Counselling is required by law for everyone who has been expelled and must be completed for at least 6 hours at a Counselling Centre for Violence Prevention. The Austrian Chancellery also funds 380 “Family Counselling Centres” across the country to address family issues including IPV. Family Counselling Centres are staffed by a multidisciplinary team of social workers, doctors, psychotherapists, and law professionals; and some of the Centres are specialised in working with perpetrators of violence. |

|

|

France |

30 “Centres de prise en charge des auteurs de violences conjugales” (CPCA) were created in 2020‑21, offering perpetrators of domestic violence psychological and medical support, as well as socio-professional support aimed at integration into employment. |

|

|

Ireland |

Following the “Second National Strategy on Domestic, Sexual and Gender-based Violence” (2016 – 2021), the Department of Justice and the National Office for the Prevention of Domestic, Sexual and Gender-based Violence (COSC) have partnered with non-governmental organisations to deploy the “CHOICES Program”, which offers male perpetrators of violence individual and group counselling sessions with the goal of long-term behavioural change. The Program also offers a parallel, independent women’s support service for the partner or ex-partner of the perpetrator, for the duration of the programme implementation, and for three months following his completion of the programme. |

|

|

New Zealand |

In New Zealand, the Ministry of Justice contracts NGOs to deliver safety and non-violence courses and support services to parties to protection orders and their children. In addition, perpetrator intervention programming and specialist staff are part of local Integrated Safety Response. |

|

Note: This table presents a non-exhaustive list of perpetrator interventions in the OECD. OECD QISD-GBV 2022 (Annex A) did not ask about perpetrator intervention programmes and these services were offered spontaneously by responding countries.

Source: OECD QISD-GBV 2022 (Annex A); (Irish Department of Justice, 2022[62]; Ministere Charge de l’Egalite Entre les Femmes et les Hommes, 2022[63]).

There are challenges to implementing perpetrator-focused programmes. When perpetrator interventions are put in place with aims to prevent further violence, it is not always clear how and in what ways perpetrators are to be held accountable (ANROWS, 2020[64]). Investing in domestic violence perpetrator programs, especially when public funds are limited, may also be politically challenging as it may detract from the immediate need of victims/survivors. Even where service providers acknowledge that perpetrators need support to effect behavioural change, there is a concern that offering such services trivialises the violence and its effects on victims/survivors (Bellini et al., 2019[65]).

More evaluations of programmes and best practice can help ensure that funds are used in a way that best supports victims/survivors. The European Network for the Work with Perpetrators of Domestic Violence (WWP) acknowledges a lack of monitoring and evaluation of perpetrator programs, making it difficult to define elements of effective intervention (Pauncz, 2020[66]). In the United Kingdom, a five‑year investigation into the effectiveness of perpetrator programmes suggests significant behavioural improvement among participants across all measured outcomes, though the report emphasises that programme completion could actually exacerbate risk “if professionals and the courts consider that the risks are being managed by a programme and so de‑escalate the case,” (Verney, 2021[67]). In Australia, monitoring and evaluation of perpetrator programmes are fairly advanced, with national standards established in 2015 in an effort improve coherence between victim and perpetrator systems and to direct reform in the area of perpetrator interventions (Box 2.4).

Box 2.4. Setting national standards for perpetrator programmes helps limit further violence

Focussing on perpetrator accountability, the Australian Government established the National Outcome Standards for Perpetrator Interventions (NOSPI) in 2015 to act as guiding principles for targeted perpetrator interventions, such as limitations on interactions between male perpetrators and the women and children against whom they have used violence, as well as behavioural change initiatives.

The six National Outcome Standards are:

1. Women and their children’s safety is the core priority of all perpetrator interventions;

2. Perpetrators get the right interventions at the right time;

3. Perpetrators face justice and legal consequences when they commit violence;

4. Perpetrators participate in programmes and services that change their violent behaviours and attitudes;

5. Perpetrator interventions are driven by credible evidence to continuously improve; and.

6. People working in perpetrator intervention systems are skilled in responding to the dynamics and impacts of domestic, family and sexual violence.

These are supported by a number of tools, including risk assessment frameworks, and a set of outcomes and indicators. After data quality has been assured, the set of indicators should help policy makers quantify results of targeted programming.

The NOSPI create inter-sectoral connections between police and correctional services; courts; perpetrator and offender programs; child protection agencies; and various community services related to mental health, alcohol and other substance use services, housing and homelessness services, employment support, and family-related services for all affected parties. Strategies include improved and increased information sharing between agencies, streamlined referral pathways between sectors, expedited protective orders and case management services for all parties involved in domestic violence incidents.

While the standards were developed at the national level, they create a framework against which state and territory governments can monitor local initiatives to hold perpetrators of violence accountable, and to reduce overall incident of violence, as well as offender recidivism. In Victoria, for example, perpetrator programs are evaluated through over 35 indicators which span domains of appropriateness, effectiveness, and efficiency and are populated through primary and secondary data collection, notably through personal interviews and a tailored, service provider data collection tool.

Source: (OECD QISD-GBV, 2022, see Annex A); (Australian Department of Social Services, 2016[68]; Deloitte, 2019[69]; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021[70])).

2.4. When crises emerge, an integrated response helps

By the time a victim/survivor finally reports violence, they are often in a situation that is very risky or unbearable. Integrating crisis and emergency services with the sector that a help-seeker first comes into contact with in a crisis situation, such as police services or the healthcare system, is therefore essential. Crisis response services refer to dedicated resources that exist to respond to IPV-related events as they occur. Crisis response services need to connect to related supports that can be mobilised to ensure continuity of care in aftermath of crisis.

The first point of contact in a violent crisis can be sector-specific or more general. In case of an IPV crisis, the first responders are often sector-specific actors including the police, health care professionals or emergency shelter staff. These sector-specific crisis responses are discussed in the following chapters.

Two more general crisis-response mechanisms exist in all countries however: dedicated telephone helplines and dedicated crisis centres. These services play cornerstone roles in supporting women to seek help if the police or emergency health care services are not directly involved.

2.4.1. Ensure that common helplines operate established referral pathways

Telephone helplines play an important role in making specialised support, advice and services accessible to women affected by all forms of violence (Council of Europe, 2022[16]). Reflecting their important role in service provision, the Istanbul Convention mandates that states set up state‑wide telephone helplines available 24 hours, seven days a week, free of charge. These helplines should provide advice to callers, confidentially or with due regard for their anonymity, in relation to all forms of violence covered by the Convention” (Council of Europe, 2011[36]). Several countries have set up helplines to assist victims/survivors of violence. Recently, the EU also set up a common helpline to support victims/survivors of GBV, as announced in November 2022 (European Commission, 2022[71]).

Telephone helplines should aim to connect those affected by violence with trained professionals to ensure easy and confidential access to information and counselling in all relevant languages. Some countries have taken special measures to ensure that the helplines are accessible to all people.

The 016 helpline in Spain, launched in 2007, provides advice in cases of all kinds of violence against women in 53 languages. It is accessible to callers with disability, using visual interpretation services, textphone and an on-line chat function (Government of Spain, 2019[72]; Council of Europe, 2022[16]; Ministry of Equality, 2023[73]). Austria makes use of interpreters to overcome language barriers and ensure that callers still access advice from expert social workers (Lobnikar, Vogt and Kersten, 2021[74]).

It is important that the helpline number is widely advertised to the public and that professionals are able to refer callers to face‑to-face services (Council of Europe, 2022[16]). For instance, the Swedish national telephone helpline on violence against women (Kvinnofridslinjen) can be one model of practice. The helpline addresses all forms of violence against women and more than half of women in Sweden knows that the helpline exists. Well‑trained and experienced social workers and nurses are able to refer callers to locally-available specialist support services (Council of Europe, 2022[16]).

The helplines are often delivered with support from non-governmental providers. For instance, the government in Denmark funds the national non-governmental organisation Lev Uden Vold (Live without Violence) to provide more and better assistance to people affected by all forms of domestic violence and rape, including intimate partner violence. As part of its work, the unit operates the Danish national helpline. The helpline is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and accepts calls from victims and perpetrators of violence, their relatives and professionals seeking assistance and advice (OECD QISD-GBV, 2022).

It is encouraging to see that several countries have set up national helplines in recent years as a response to the Istanbul Convention entering into force, including Albania, Finland, Monaco, Montenegro, and Serbia (Council of Europe, 2022[16]). Japan has also extended their domestic violence counselling helplines to 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and also incorporated text messaging services and email consultations (UN Women, 2020[75]).

2.4.2. Digital tools became more common during the COVID‑19 crisis

During the COVID‑19 pandemic, many countries responded to confinement policy measures by introducing innovative solutions to traditional help-seeking resources. During confinement it was difficult for many women experiencing abuse to call a helpline while trapped at home with their abuser. Many helpline services therefore established internet-based lines of communication, including via e‑mail and through web- or application-based chat services (OECD QISD-GBV, 2022); (UN Women, 2020[75]). Many helpline services therefore established internet-based lines of communication, including via e‑mail and through web- or application-based chat services (OECD QISD-GBV, 2022); (UN Women, 2020[75]).

For instance, victims/survivors of violence in Madrid can now access an instant messaging service that offers psychological support, and across Spain, one helpline‑style initiative combines crisis and case management services by using technology to connect emergency support workers, case workers and qualifying women experiencing IPV in real time (Box 2.5).

Spain is not alone in having used technology to better reach women in need of support: many of the respondents to the OECD Questionnaire were able to provide further examples of how the COVID‑19 pandemic had prompted them to come up with innovative ways of providing support and services (Table 2.4). In Lithuania, for example, technology providers have developed an algorithm that can detect and identify victims/survivors and refer them to support services (UN Women, 2020[75]).

The private sector, too, has teamed up with government to respond to IPV-related crisis. Vodafone, for example, developed an app that is now in use in at least 11 countries that enables women to local support during a crisis and access other local resources (Box 2.5).

Box 2.5. Using technology in new ways during the pandemic

Crisis and case management service for women experiencing IPV and GBV in Spain

Since 2005, the Servicio telefónico de atención y protección para víctimas de violencia de género (ATENPRO) has provided 24/7 crisis and case management services to women experiencing intimate‑partner violence. Financial support from the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan Funds will help update ATENPRO devices and extend the service beyond IPV to include all forms of violence against women.

ATENPRO is a service available by request or referral, and requires users to meet two conditions:

they must no longer be cohabitating with perpetrators;

they must participate in a special care programme offered in their autonomous region.

Service users are equipped with a mobile device which acts as a direct line to support workers nearby. Whenever necessary, service users can contact the help-centre staff, who either guide them or mobilise the necessary resources to care for and protect them. In some cases, electronic devices may also be imposed on perpetrators of violence to ensure compliance with active judicial measures.

ATENPRO seeks to achieve three main objectives. First, it provides users with a sense of security and peace of mind by offering information, advice and a guaranteed line of communication at all times. Second, it creates a social network of support within users’ known environment, including non-aggressive family and friends, which can help boost users’ self-esteem and improve their quality of life. Third, it actively monitors users’ situations through regular contact via the mobile application. It is also inclusive, in that the mobile nature of the service can improve access for women living in rural and remote communities, elderly women and women with disability. It also helps ensure that the care response is continuous.

ATENPRO is delivered by the Ministry of Equality through annual collaboration agreements with the Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces. In 2022, more than 17 000 users used the service across regions. In November 2021, the Minister of Equality announced that the service will be extended to cover all forms of GBV against women – including sexual exploitation and trafficking – by 2023. The Ministry estimates that this marked increase in service coverage will extend protection to 50 000 women – around three times the current uptake level.

Additionally, since 2009, a remote monitoring system – el Sistema de Seguimiento por Medios Telemáticos de las Medidas y Penas de Alejamiento en el ámbito de la Violencia de Género – has attempted to monitor the movements of perpetrators. In situations where the court system has limited perpetrator’s movements, this system makes it possible to monitor perpetrator’s compliance with precautionary measures and restraining orders that prohibit proximity to the victim/survivor.

The monitoring system consists of two essential elements: devices for the victim/survivor and the perpetrator, as well as the services from a control centre (Cometa). The devices are GPS-controlled in order to prevent perpetrators from approaching victim/survivors in sensitive locations such as their home, children’s school, supermarket, workplace or gym. Victims’ devices have a panic button in case of emergency. Cometa is responsible for installing, maintaining and removing the devices. They also handle all events that the devices indicate on a 24/7 basis.

The main purpose of the monitoring system is to increase the safety and protection of victims of IPV. It provides permanently-updated information about issues that affect compliance or non-compliance of precautionary measures or sentences, or any possible (accidental or deliberate) incidents in the operation of the equipment used.

Remarkably, there have been zero cases of femicide against the women protected within the Cometa system since its introduction in 2009.

Vodafone Foundation apps against abuse provide information, support and services

The Vodafone Foundation provides a good example of how technology can be used to help connect victims/survivors of GBV with services. The Foundation has a portfolio of apps available free of charge in many countries, including in 8 OECD countries. The apps offer a range of services, support and advice available directly on smart phones.

One of the larger platforms, BrightSky, launched in the United Kingdom in 2018, has since been made available in 10 countries. For those with immediate need for help, the app helps users to locate their nearest domestic violence support centre. It also contributes to awareness-raising by providing information that enables users to assess the safety of a relationship, find out about different forms of abuse and how to help a friend that may be affected. The Foundation has teamed with postal workers in the Czech Republic so that postal workers who have received training about how to recognise signs of abuse also have been encouraged to recommend the app to women who are affected (Chapter 6).

Source: For Spain: (OECD QISD-GBV, 2022) (Government Office against Gender-based Violence, 2022[76]; Council of Ministers, 2021[77]; Minisitry of Equality, 2021[78]; Ministry of Equality, 2015[79]) and for Vodafone: (PostEurop, 2020[80]; Vodafone, 2022[81]; Ministry of Equality, 2023[82]).

Table 2.3. The COVID‑19 pandemic confinement policies prompted more and new service delivery

Help-line related policy measures that supported victims/survivors during COVID‑19 confinement periods

|

Belgium |

Since the start of the COVID‑19 crisis and confinement, the Brussels line has received three times the number of calls as pre‑COVID‑19. The listening ranges have been extended from 20 to 30 hours of listening per day and the chat has also been extended from 2 to 10 hours per day. |

|

Chile |

SernamEG’s services were provided differently to meet the needs of beneficiaries during COVID‑19. Silent communication channels were incorporated as alternatives for women in a situation of confinement, the Web Chat 1455 and WhatsApp +56997007000, as confidential, private and secure guidance tools, operating 24 hours a day and attended by specialists in communication on support protocol. In the case of the improvements made to the 1455 helpline, in particular the silent channels, Web Chat and WhatsApp, these were financed in 2020 by Facebook for a period of 3 months. After this period, the resources were reallocated from SernamEG’s budget. |

|

Finland |

Additional funding was allocated to Nollalinja for opening a chat service in 2021‑22, although future funding of the service has not been confirmed. |

|

Germany |

The project “Helpsystem 2.0” supports women’s shelters and specialist support services with the professional handling of the digital challenges of the COVID‑19 pandemic. The core of the project is improving technical equipment, the necessary digital qualification of staff and the professional translation of support for women and girls affected by violence. |

|

Israel |

New tools were developed, including a) so-called “quiet lines”, which are secret referrals or inquiries by designated SMS messages; b) technological platforms; and c) increased accessibility to services, including phone lines computer-based communication and social media applications is being developed. |

|

Portugal |

New means of communication and distanced assistance were developed and reinforced. These include video call, SMS, Messenger, WhatsApp and email. The telephone service was also reinforced, while keeping in place face‑to-face assistance in urgent situations, with rotating teams. |

|

Türkiye |

Helpline service started being offered through WhatsApp and BİP applications. |

Note: This table presents a non-exhaustive list of measures that supported victims/survivors during COVID‑19 confinement periods.

Source: OECD QISD-GBV 2022 (Annex A).

2.4.3. Crisis centres provide services to help those in the most urgent situations

Physical crisis centres can be effective to help victims/survivors when they need most urgent help. Despite efforts to support early intervention and effective service provision to prevent women from becoming seriously injured, there are still many who are not able to report their perpetrator before they end up in critical situations and require urgent assistance. This is reflected in the Istanbul Convention, where specialised sexual violence crisis centres that provide medical and forensic examinations, trauma support and counselling (Council of Europe, 2011[36]). In line with the Convention, many member countries have in place dedicated crisis centres, both for sexual violence and for GBV that is not necessarily sexual (Table 2.4).

Hungary’s response to QISD-GBV 2022 (Annex A) illuminates the necessary continuum of support from prevention to crisis response. Hungary offers a national network of 20 crisis centres, 8 secret shelters, 22 halfway houses and 7 crisis management clinics. Of the crisis management clinics, “the priority for victim support is to provide assistance as soon as possible, in order to resolve problems before they escalate into violence and to prevent the need to flee home if problems that indicate or lead to domestic violence develop” (emphasis added). In these facilities, legal, psychological and social work support is also available. At the same time, the crisis centres, shelters and halfway houses offer an important source of cross-sector care when violence does occur.

Table 2.4. OECD countries report that they operate at least some dedicated crisis centres

Examples of national-level, multidisciplinary GBV crisis support centres, including sexual violence centres

|

Finland |

Seri Support Centres are accessible 24/7 to individuals of any gender identification aged 16 and older who have experienced sexual violence occurring less than one month from their visit. Services include crisis care and support, forensic medical examinations, access to psychologists and social workers, medications, vaccinations or emergency contraception, treatment follow-up plans and a referral service to psychiatrists and third sector or municipal officials. Services are offered without necessarily having to make a police report. The first Seri Support Centre was established in 2017 in Helsinki; there are now 21 SERI Support Centres in Finland, and three more centres are planned to be established by end of 2023 |

|

Hungary |

Complex services are provided by 20 crisis centres, 8 secret shelters, 22 halfway houses and 7 crisis management clinics. These services include sheltered accommodation and full physical care as needed, assistance from professionals (lawyer, psychological counsellor, social worker), and assistance through social work tools. This can include finding a safe housing solution, assistance in solving life management problems, identifying and managing sources of income, identifying external family contacts, strengthening parenting roles, psychological counselling, referral to health care services, providing community programmes, legal as well as childcare advice. These services are often provided by NGOs but are publicly funded and involve the participation of different Ministries. |

|

Israel |

A nationally funded domestic violence emergency centre (the “Aluma Centre”) was recently opened to act as a 24/7 “emergency room for domestic violence”. The Centre provides interdisciplinary support to women and their children, including access to specially trained police officers, mental health specialists for adults and children, mediation services, legal experts and a network of relevant community-based service providers. The Centre is also equipped with dormitories to provide temporary emergency shelter. In addition, the Welfare Ministry established 165 regional domestic violence centres, 59 of which are dedicated to the Arab sector, and four of which serve the ultra-Orthodox sector. |

|

Japan |

“One‑stop Support Centres for Victims of Sexual Crimes and Sexual Violence” exist in every prefecture and offer immediate medical assistance, psychological support and legal support. |

|

Korea |

One‑stop centres known as “Sunflower Centres” have been established within 32 metropolitan hospitals to respond to adult-survivors of violence, including sexual violence, and their families. Sunflower Centres offer psychological and legal counselling, in addition to medical support, including forensic medical services in the wake of sexual violence. Regionally operated “1366 Hotline Centres” offer 24/7 support to women experiencing domestic or sexual violence in 18 cities, the first of which was established in 2001. The Centres collaborate with other counselling centres, shelters and Sunflower centres to provide multidisciplinary support to help-seeking women through referrals. |

|

Latvia |

The central government funds, in part, the Marta Centre, which provides women experiencing violence with access to a social worker, legal advisor, and psychologist. The social worker also acts as a case manager to facilitate help-seeking. |

|

The Netherlands |

There are 16 Centres for Sexual Violence (CSG) offer 24/7 access to doctors, nurses, psychologists, social workers and sexologists. |

|

Slovenia |

The Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities funds, in whole, two crisis centres for women and their children. The Centres provide an integrated, multidisciplinary approach in the prevention of domestic violence, and includes accommodation for up to 3 weeks which can be extended for an additional 3 weeks. After this period of emergency accommodation, they have the option of moving to NGO-operated safe houses for up to one year. |

|

Spain |

Since 2020 there are two crisis centres in Spain: one in Asturias and one in Madrid. The Government Office against GBV is currently working to establish a crisis centre in each Spanish province, and in the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla. It will establish 52 centres by December 2023 using financial support from the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan Funds. In addition, Crime Victim Support Offices provide a public service of integrated support and care in legal, psychological and social aspects for victims of crime. Support for victims is offered in four stages: shelter advice, information, intervention (in legal matters, in psychological matters and social aspects) and supervision. |

|

Türkiye |

The Ministry of Family and Social Services oversees 81 nation-wide “Violence Prevention and Monitoring Centres” (VPMCs) which provide psychosocial, legal, health-related, educational and vocational support, in addition to counselling services and police liaison officers on site. The Centre staff is employed by the ministry, and specific services are staffed through inter-ministerial and inter-governmental agreements, whereby interdisciplinary staff are paid by their own institution. For example, the police liaison officer is paid a salary through the Provincial Security General Directorate; the expert who comes to the VPMCs on certain days of the week to provide vocational consultation works at the Provincial Directorate of Labour and Employment Agency. |

|

United Kingdom |

The Secretary of State for Health commissions 47 sexual assault referral centres (SARCs), which provide an integrated response to sexual violence and rape, irrespective of age, gender or when the assault or abuse occurred. Services include comprehensive forensic medical examination; follow up services which address the client’s medical, psychosocial and ongoing needs; and direct access or referral to an Independent Sexual Violence Adviser (ISVA) who supports help-seekers by way of case management services. |

Note: This table presents a non-exhaustive list of ISD practices related to crisis support in the OECD for survivors of violence. Additional

comments incorporated following OECD members’ review.

Source: OECD QISD-GBV 2022 (Annex A); (Consejo de Ministros, 2021[83]; Government of Spain, 2019[72]).

Similar to other forms of social service provision, it is difficult for countries to achieve equitable geographic coverage to support victims/survivors, especially in rural areas. This is true even in countries with relatively strong policy commitments to crisis centres. For example, a recent report by the Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada assesses the shelter and resource needs of women living in the remote northern communities of Canada. Their data suggests that “90 to 150 beds are available across Inuit Nunangat for an estimated population of 15 850 Inuit women, resulting in a maximum average of one bed per 106 women” (Pauktuutit, 2019[84]). And in the most remote communities without shelters, housing support is even more difficult to come by for help-seeking women. They also highlight the comparatively higher cost of travel (both in money and time) to and from services as a unique barrier to help-seeking for women living in rural and remote communities.