This chapter focuses on the governance and evidence‑based design of end-of-life care (EOLC) systems. The COVID‑19 crisis has shed a light on the unpreparedness of EOLC services to emergencies, causing disruption in service provision for people at the end of life. Poor governance can also exacerbate fragmentation in the care that people receive at the end of life. It highlights the weakness of EOLC research and data, which hinders benchmarking and prevents best evidence to inform policy making. Countries have already started to promote community care and technology in EOLC during the pandemic, and further efforts could be undertaken. Information sharing and case management can be useful tools to provide more integrated care to people with complex needs approaching death. EOLC would also benefit from better evidence produced through a scale up in research, improvement of data linkages and design of indicators.

Time for Better Care at the End of Life

6. Strengthening governance and evidence‑based design for end‑of‑life care

Abstract

Introduction

The landscape of end-of-life care1 (EOLC) has changed substantially in the last decade due to changes in demographics, medical technologies and disease patterns, resulting in a large number of people who live with conditions requiring palliative care (Leung and Chan, 2020[1]). Moreover, the recent rapid growth of palliative care services signals a shift towards broader acceptance of EOLC and palliative care within health care systems and the wider public, which has resulted in the greater uptake of these services by patients and their families (Chen et al., 2014[2]).

This chapters finds that more could still be done to strengthen the governance and evidence‑based of end-of-life care. The COVID‑19 pandemic has also shown the paramount importance of ensuring continuity of services despite wider pressures on the health and care system, including national emergencies. It has also raised the need of delivering end-of-life care in different care settings outside the hospital while also increasingly relying on digital solutions. In addition, EOLC is often fragmented, with individuals having several people involved in different aspects of their care. This can be confusing for the individual as well as their relatives and informal carers. More investment in research for palliative care and EOLC would help to improve symptom control and adequately meet demand (Sleeman, Gomes and Higginson, 2012[3]).

Health and social systems that can withstand pressures during emergencies such as economic downturns and pandemics will benefit individuals by avoiding bottlenecks in care as well as lack of compassionate care for dying patients. Ensuring sound EOLC research and data informs decision-making and offering integrated and adaptable EOLC services are important elements to improve care for those at the end of life and their families and carers. Good care co‑ordination of EOLC services means people receive the cohesive care and services, which are joined-up and provide an overall benefit. The availability of sound data is an important driver of effective management of EOLC. EOLC research is essential for policy makers to make informed and sound decisions and can help to improve the quality of EOLC services while sharing knowledge and research among countries. Finally, sufficient data and evidence, together with policy coherence help systems to be more adaptable.

The remainder of the chapter is organised as follows. Section 6.1 highlights the importance of the sub‑principles of a well-governed and evidence‑based system in EOLC. Section 6.2 illustrates the consequences of system lacking such focus, while Section 6.3 explores policies and best practices to improve information, integration and adaptability.

Key findings

Few countries issued specific guidelines for health workers to adapt palliative care to the COVID‑19 pandemic. Guidelines from only five countries mentioned both palliative care needs and mode of delivery. Because of the surge in demand, frontline workers in primary care and long-term care had to provide end-of-life care with insufficient training and knowledge. Insufficient medication such as morphine and oxygen in those settings made end-of-life care more challenging. A systematic review of evidence across countries suggests that discussions on advance care and end-of-life care declined. Social distancing rules led to isolation at the time of death and lack of support for relatives.

EOLC is often fragmented, requiring different services in different locations. More could be done to improve co‑ordination for users. 60% of countries do not have any programme or strategy to implement an integrated approach across different levels of government or across ministries. Because of uncoordinated care, people experience delayed discharges and many care transitions, with more than half of patients moved to another care setting at least once in the last three months of life. Hospitalisations occurred in two‑third of cases for people at home, due to a decision to provide more life‑sustaining care.

Data infrastructure in OECD countries is still weak because end-of-life care data requires strong data linkages which are not yet in place in most countries. Only nine OECD countries collect data integrated into health and social information systems which can be used for end-of-life analysis. Nearly half of the responding countries did not collect EOLC data through specific indicators that were integrated into broader health and social care information systems nor had a system in place to monitor and evaluate palliative care. This hinders evaluation of care progress and international benchmarking.

Research in EOLC is insufficient and not high-quality due to low funding and ethical and methodological challenges to gather information from the population. Less than 30% of OECD countries have a national research agenda and less than 16% a local research agenda on the topic. This leads to lack of strong evidence about best practices of care and such gaps in high-quality evidence hinder policy prioritisation and the translation into optimal care practices.

Policy options

In anticipation of future shocks, countries could develop new models of palliative care with an increased emphasis on training frontline health and social care workers, ensuring supplies of medicines and equipment, and promoting advance care planning and the use of technology for palliative care consultations to scale up services in case of surge demand. Luxembourg made efforts during the COVID‑19 pandemic to ensure that people in need of EOLC could receive adequate care at home, without being hospitalised, when possible. The United States developed an online platform to provide specialist palliative care remotely and training for generalist palliative care.

Care co‑ordination can help the end-of-life care experience and reduce the extent of hospital care. Sharing information through electronic notes sharing or shared electronic systems – such as those available in Australia and Costa Rica – represents an essential step to support care co‑ordination and integration. Care co‑ordinators such as the nurse liaison in Ireland or the mobile palliative care teams in Belgium can also support a more integrated system.

Countries could maximise the use of the wealth of available data by developing links across different datasets. The availability of linked and timely data would facilitate the calculation of meaningful internationally comparable indicators of care quality at the end of life, resulting in international benchmarking and support to the policy making around EOLC. Sweden has the Swedish Register of Palliative Care for that purpose. Other countries such as Ireland and England focus on publishing and monitoring key performance indicators.

Countries could improve research capacity on end-of-life care by promoting funding and developing institutional capacity to increase research projects on EOLC. Some countries, including Belgium, Ireland, France, and the Netherlands, have developed strong organisations supporting palliative care research. Addressing knowledge gaps in cost-effectiveness and models of care can contribute to putting EOLC higher in the policy agenda and improve training for professionals.

6.1. Why are good governance and evidence‑based design in end-of-life care important?

This section outlines why it is critical to ensure that end-of-life care has continuity of services despite wider pressures on the health and care system, is integrated across care settings, and reflects the latest research, data, and evidence. Each component or sub-principle of the well-governed and evidence‑based principle (adaptable, integrated, data-driven and research-based) is discussed. The remaining principles are discussed in the different chapters of the report while the overview Chapter 1 presents the overall framework.

The first sub-principle is that care is adaptable to withstanding pressures between and during emergencies, such as economic downturns and pandemics. A systems-level approach is necessary to ensure high standards and quality of EOLC for patients and families, as well as the well-being of staff, are maintained despite external pressures (Hanna et al., 2021[4]). Adaptability of EOLC is important to foster resilience in the face of disruptions and shocks, but it also helps with changes in population preferences over time and adapting to socially and culturally diverse groups.

The second sub-principle is that EOLC is integrated across the health care system and all care settings, as well as across and within levels of government, regardless of underlying conditions. Ensuring quality EOLC requires collaborative, cohesive, and co‑ordinated care across settings. Integrated care models need to be flexible and supported by clear, well-considered protocols and policies, with a well-resourced multidisciplinary approach fundamental to ensuring the provision of integrated care (Evans, Harding and Higginson, 2013[5]). From a patient perspective, the provision of integrated care enables them and their caregivers to navigate between services more easily and empowers them to manage their care needs across different stages of their end-of-life journey (Thomas-Gregory and Richmond, 2015[6]).

The third sub-principle is that EOLC is data driven. Data on EOLC needs to be collected, utilised to monitor and manage the immediate care of the individual patient, as well as evaluate and improve standardised care for all patients and families (Davies et al., 2016[7]). Data may include administrative data, clinical data, as well as patient and family reported outcome and experience data, with insights drawn upon to improve care (Bainbridge and Seow, 2016[8]). Missing data, data fragmentation and an insufficient data infrastructure represent challenges to monitor the quality of care and to allow for better integration (Rajaram et al., 2020[9]).

The last sub-principle relates to EOLC being research-based. Investment in EOLC and palliative care enables the delivery of high quality, evidence‑based palliative care, critical for maintaining a good quality of life. This includes funding research into pain and symptom management, psychosocial support, appropriate medical interventions, and maintenance of quality of life for the patient and their family. Research producing information on preferences of place of death, patients’ experiences and outcomes can direct the provision of care towards patients’ needs and preferences while also providing crucial information to patients and their families facing difficult care choices. Research can create opportunities for collaborative work, facilitate interdisciplinary approaches, and support decision-making by clinical teams, patients, and carers. International collaboration and knowledge‑sharing, as well as sharing successful funding frameworks that support research focused on benefits for patients, their families and those close to them is also critical (Higginson, 2016[10]). Evidence from research needs to be better embedded into national policies, plans and regulations. Research findings can only change outcomes if adopted and implemented by health care systems, organisations and clinicians (Evans, Harding and Higginson, 2013[5]).

6.2. The consequences of a lack of well-governed and evidence‑based end-of-life care

This section highlights current shortcomings in the governance of end-of-life care and its consequences. Research and data on the topic are still underdeveloped and thus rarely incorporated into policy making. Care provision is hardly integrated within settings of care and across government departments. The current pandemic has shed light on the lack of preparedness of end-of-life care services for emergencies.

6.2.1. Countries have been unable to scale up care during the pandemic

At the onset of COVID‑19 crisis, countries were particularly unprepared for a pandemic, and most countries had not developed specific palliative care guidelines for emergencies. Many countries issued specific guidelines for health systems in the first months of pandemic onset, but palliative care was rarely included. Among 20 countries that issued guidelines on infection control in long-term care, only five mentioned specific provisions for palliative care needs and mode of delivery (Canada, Latvia, Luxembourg, Portugal and the United States); Ireland included the possibility of transferring people at the end of life across settings to ensure they are provided with the palliative care they need; and Slovenia activated a helpline for health care workers to receive counselling on the provision of palliative care services (Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[11]). Additionally, Australia and Denmark recommended relaxing the visitor bans for patients at the end of life (OECD, 2020-2021[12]). In Ireland, guidance provided information on the care for patients with COVID‑19, supportive therapies at the end of life, and advance care planning in residential settings (HSE - Ireland, 2020[13]).

Even when specific guidance on palliative care and end-of-life care existed, substantial gaps were identified. In the COVID‑19 guidance documents concerning palliative care, key aspects of palliative care, practical guidance, and broader structural and co‑ordination considerations were largely absent (Gilissen et al., 2020[14]). In particular, guidance for the health and social care sector did not include holistic symptom assessment and management at the end of life, comprehensive ACP communication, and support for family including bereavement care. Only a few made specific recommendations regarding symptoms at the end of life and nonphysical (ethical, cultural psychological, social, or spiritual) needs were hardly addressed. Moreover, the COVID‑19 pandemic hindered discussions surrounding advanced care planning both inside and outside the hospital due to the overwhelming situation (Hirakawa et al., 2021[15]). Recommendations related to end-of-life care were not specific enough with respect to staff training regarding communication and decision-making, referral to specialist palliative care or hospice, support for staff, and deployment of staff, such as moving palliative care staff from acute settings to the community.

As a result of the surge in deaths during the pandemic and the lack of specific provision for such services, the provision of end-of-life care was greatly impacted during the COVID‑19 pandemic, leading to increased hardship for those needing such care. The increase in mortality directly and indirectly had an impact on all parts of the health care system (see Box 6.1). Increased demand had also a large impact on palliative care needs, especially in certain settings. For instance, in the United Kingdom, deaths in care homes increased by 220%, while home and hospital deaths increased by 77% and 90%, respectively (Bone et al., 2020[16]). Fear of COVID‑19 infections and hospitals being overwhelmed led to a change in behaviour: in the United States there was a decline in emergency department (ED) and inpatient visits across the country by 38% and 46%, between March and May 2020 (Zhang, 2021[17]).

Specialised palliative care teams were not always able to support other workers and the patients in the community (Marie Curie UK, 2021[18]; Santé publique, 2020[19]). Some palliative care wards were transformed into COVID‑19 wards, reducing the availability of beds for people in need of end-of-life care. There was an unplanned shift towards home and end-of-life care and towards nursing home end-of-life care during the pandemic. This shift left first-line health and social care professionals in the challenging position of managing end-of-life care, even as they did not have the right knowledge of palliative care nor were proficient in communication on those topics. In the United Kingdom, for instance, community nurses and General Practitioners (GPs) experienced a substantial increase in the need for and complexity of palliative and end-of-life care such as having to provide more symptom management and bereavement support (Mitchell et al., 2021[20]). In Belgium, health care workers in primary care felt unprepared to manage the crisis, probably because of the insufficient use of ACP and the lack of end-of-life care guidelines, elements that make it challenging to make decisions during the crisis (Service public fédéral, 2020[21]). COVID‑19 disproportionally affected those residing in care homes, leading to a surge in palliative care needs and creating enormous pressures to deliver high-quality EOLC with the result of an increased emotional toll on staff (Bone et al., 2020[16]). Delivery of quality care was compromised in all settings because of staff shortages. Several studies suggest decreased advance care planning and end-of-life discussions with residents and relatives because of social distancing measures or lack of staff availability, reversing progress achieved in palliative care in previous years (Spacey et al., 2021[22]). Finally, the lack of essential supplies and a medicine shortage, in particular oxygen and sedatives, challenged the provision of quality care (Marie Curie, 2021[23]).

Such challenges together with the impact of lockdowns and restricted visitation rights led to lonely situations at the end-of-care. People in nursing homes and hospitals experienced restrictions in visitation rights. Countries adapted the guidelines progressively in this respect. In Austria, several organisations provided guidelines on end-of-life care and visiting restrictions were lifted for people at the end of their life in nursing homes (Adelina Comas-Herrera, 2020[24]). Australia and Denmark also recommended relaxing measures that banned visitors for people at the end of their life (Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[11]). Similar measures were adopted for people in hospitals or ICU, especially if they tested positive for COVID‑19. In many instances, professionals adapted and used remote or telephone consultations. Even so, it was sometimes challenging to include relatives in end-of-life care decisions and even more to provide support. The process of grief and bereavement was also more complex for family members because of visiting restrictions (Fadul, Elsayem and Bruera, 2020[25]).

Box 6.1. The impact of COVID‑19 on mortality

COVID‑19 has led to an important number of deaths since early 2020. The total world cumulative mortality is 6.55 million as of October 2022. This represents approximately 829 confirmed deaths per million population worldwide. As of mid‑2021, the average across the OECD was of 1 285 deaths per million, ranging from 5 deaths per million inhabitants in New Zealand to 3 070 deaths per million in Hungary. COVID‑19 contributed to a 16% increase in the expected number of deaths in 2020 and the first half of 2021 across OECD countries (OECD, 2021[26]).

For some countries and some time periods, the number of confirmed deaths is much lower than the true number of deaths due to COVID‑19. The comparability of COVID‑19 deaths has been hampered by differences in recording, registration, testing and coding the cause of death. Excess mortality provides a measure of mortality that is less affected by these differences but is capturing other causes of death. Excess mortality – the number of deaths over and above what would have been expected at a given time of the year – has been used to measure the impact of the pandemic overall. Across all countries, excess mortality was positive for all but one country (Norway) and was 60% higher that reported deaths in 2020 but was more moderate in 2021. On a global scale the number of excess deaths in 2020 was estimated to be 3 million and the total cumulative death count over the entire period is estimated to be twice or four times the current count of confirmed deaths. The Economist estimates the global COVID‑19 deaths to be four times the confirmed deaths, while HIME’s estimates them to be less than 3 times higher than the confirmed data (Adam, 2022[27])

There has also been an indirect increase in mortality due to delayed care, which is more difficult to quantify. For instance, cancer screening and referrals were significantly delayed during the pandemic, Data from Health at a Glance 2021 shows that the proportion of women screened for breast cancer within the last two years fell by 5 percentage points in 2020 (OECD, 2021[26]). Such delays have a negative impact on mortality due to associated delays in cancer diagnosis. Evidence shows that delaying surgical treatment for cancer by four weeks was associated with a 7% increase in the risk of death, while a delay of systemic therapy or radiotherapy increases death by 13% (Hanna and al, 2020[28])

Visits for cardiac and cerebrovascular events declined, causing worse outcomes. Hospital admissions for such patients declined, especially at the beginning of the pandemic, and the reduction in hospital visits for minor events appears to be related to more risk of complications and mortality for those finally reaching hospitals. Other disruptions in care pathways such as delays in ambulance time and critical interventions have been associated in higher mortality in some studies (OECD, 2021[26]).

The pandemic has led to a decline in life expectancy in 24 of 30 OECD countries. In the United States, for instance, the decrease in life expectancy was 1.67 years, translating to a reversion of 14 years in life expectancy gains (Chan, Cheng and Martin, 2021[29]). Across several countries, the excess years of life lost due to the pandemic in 2020 were more than five times higher than those associated with the seasonal influenza pandemic of 2015.

6.2.2. Fragmented systems undermine effective end-of-life care delivery

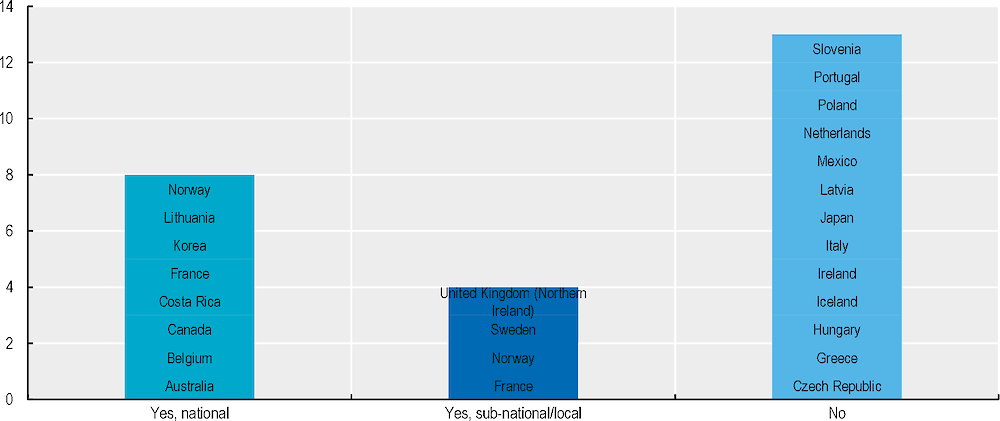

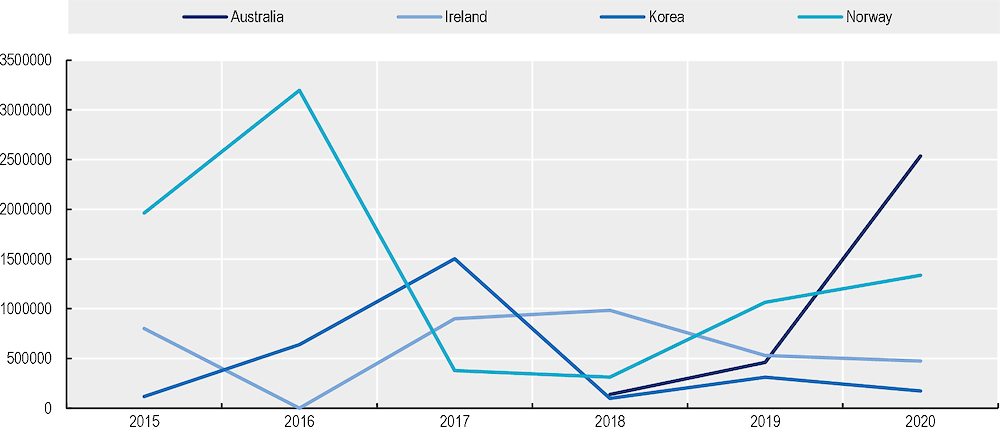

Despite increased awareness of EOLC across countries, policies are not always well co‑ordinated. Among 23 OECD countries surveyed, 60% do not have any programme or strategy to implement an integrated approach across different levels of government or across ministries. Among the countries that reported such programmes/strategies, seven countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Costa Rica, France, Lithuania, and Norway) issued them at the national level and four (France, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom (Northern Ireland) at the subnational/local level (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1. Programmes/strategies for integrated cross-government approaches to EOLC governance

Patients often experience multiple transitions near the end of life. An analysis of European countries highlights that more than half of patients in all countries were moved to another care setting at least once in the last three months of life, between 5% and 12% of patients were transferred three times or more in the same period, and 1 in 10 patients who died non-suddenly experienced a transition in the final three days of life (Van den Block et al., 2015[30]). Such transitions affect the continuity and quality of care. Most often such end-of-life care transitions are late hospitalisations for people residing at home. Furthermore, the VOICES survey for bereaved families shows that more than a third of respondents reported poor co‑ordination between inpatient and outpatient services in England (United Kingdom) (ONS, 2016[31]). Similarly, only around one‑third of the VOICES survey’s respondents in New Zealand reported that co‑ordination between hospital and other services worked well (Reid et al., 2020[32]).

Preventable hospital readmissions are frequently a consequence of poorly managed transitions. There is evidence from cross-country studies of admission to hospitals that could be considered unnecessary and/or remaining in acute hospitals for longer than necessary, which can also result in unnecessary high costs (Cardona-Morrell et al., 2017[33]). Such hospital admissions and frequent transitions appear to be related to the need for life‑prolonging treatment because of the challenge of managing clinical complications in primary care settings and the lack of availability of palliative care outside hospitals (Van den Block et al., 2015[30]). Repeated hospital admissions at the end of life and intensive care unit (ICU) admission can lead to worse quality of life for the patient including increased emotional and physical suffering, as well as caregiver distress (Bernacki and Block, 2014[34]; Leith et al., 2020[35]; Wang et al., 2016[36]; Zhang et al., 2009[37]). There is also evidence that delayed hospital discharges can occur among palliative care patients, particularly because of the challenges in co‑ordinating the discharge planning and finding appropriate services outside hospitals (Catherine Thomas, 2010[38]).

With population ageing and changing family structures an important share of people at the end of life are in nursing homes and there is often a lack of co‑ordination among acute care, hospital palliative care and long-term care. According to data collected by the European Association of Palliative Care, in the majority of responding countries collaboration only happens “sometimes” between long-term care workers and palliative care specialists. In only three OECD countries (Austria, Belgium, Lithuania) collaboration happens “always” or “most of the times”, and in three other OECD countries (Czech Republic, Israel, Italy) collaboration happens “very rarely” (Arias-Casais N, 2019[39]). Lack of funding also hinders integration of palliative care into long term care facilities. Only half of the surveyed countries report dedicated funding for the provision of palliative care in long-term care facilities, including nine OECD countries (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) (Arias-Casais N, 2019[39]).

Uncoordinated care can also lead to overtreatment, particularly with respect to medication. People in later life often have more than one medical condition and take a range of different drugs to treat these. While polypharmacy (taking multiple medicines) is in many cases justified for the management of multiple conditions, inappropriate polypharmacy increases the risk of adverse drug events, medication error and harm – resulting in falls, episodes of confusion and delirium (OECD, 2019[40]). Polypharmacy may also lead to higher hospitalisation and institutionalisation. OECD data shows that polypharmacy rates among older people vary more than 11‑fold across countries: it ranges from 22.3% of those 75+ to 68% in primary care and from 7.5% to 87% in long-term care. More targeted studies show that a substantial share of older persons with life‑limiting diseases receive drugs of questionable clinical benefit during their last three months of life: 32% of adults continue to take such drugs and 14% receive them for the first time (Morin et al., 2019[41]). This suggest that different policies play a role, such as the establishment of targeted polypharmacy initiatives in some countries, including prescribing policies. Lack of training and guidance of professionals as well as the co‑ordination of drug prescribing among professionals might contribute to adverse drug-related events. Research also shows that having an interprofessional health team can co‑ordinate polypharmacy and prescribe drugs if necessary (Dahal and Bista, 2022[42]).

6.2.3. Lack of appropriate data prevents benchmarking

Previous OECD work has shown that health lags far behind other sectors in harnessing the potential of data and digital technology and this is even more so for end-of-life care. Missing data, data fragmentation and an insufficient data infrastructure pose significant barriers to the analysis and integration of data for ongoing quality improvement in palliative care services and precludes the examination of gaps at a system level (Rajaram et al., 2020[9]). Data collection on quality of care and pathways at the end of life linked to cause‑specific mortality is limited.

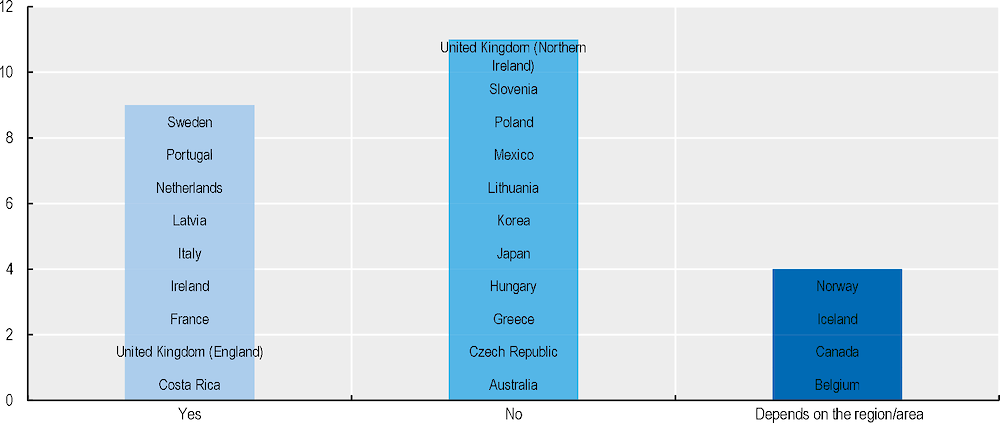

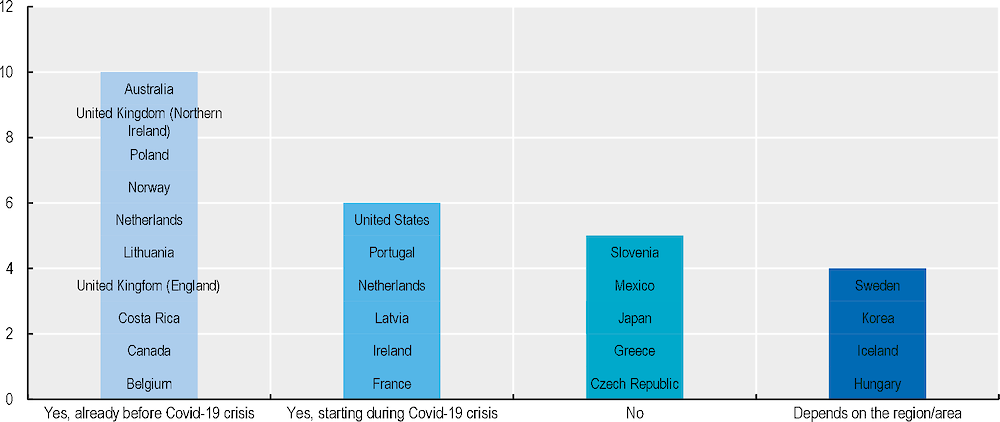

Collecting and sharing timely data is still an underdeveloped practice across OECD countries. Figure 6.2 indicates that an important share of OECD countries surveyed (46%) did not collect EOLC data through specific indicators that were integrated into broader health and social care information systems. Furthermore, four countries (Belgium, Canada, Iceland, and Norway) reported that the collection and integration of data in information systems varied across regions/areas. Only nine countries (Costa Rica, France, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, and the United Kingdom (England) reported performing such collection and integration of data.

Figure 6.2. End-of-life care data are not always collected and integrated into health and social care information systems

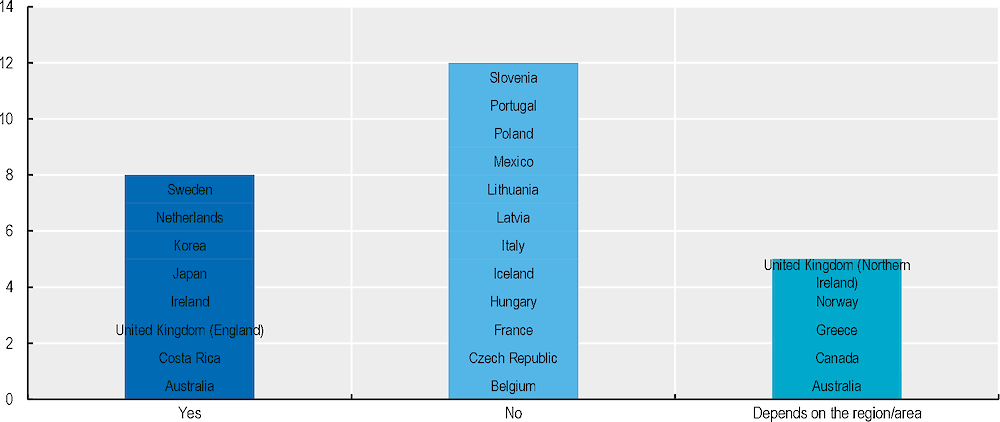

In a survey of OECD countries, nearly half of the responding countries (12 out of 25) held no system in place to monitor and evaluate palliative care experiences and outcomes such as patient reported outcomes (PROMs) and experiences (PREMs) (Figure 6.3). Eight countries (Australia, Costa Rica, Ireland, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom – England) reported having some system in place and five countries (Australia, Canada, Greece, Norway, the United Kingdom – Northern Ireland) reported that the existence of such systems may vary across regions/areas. For instance, in Belgium, only very little information is collected on end-of-life care. The Flemish community only collects indicators on the place of death and the presence of Advance Care Planning (ACP – see Chapter 3 for definition), and only in nursing homes (OECD, 2020-2021[12]). Canada has no national standardised system for collecting indicators on EOLC and when such indicators exist, there is variability about the extent to which they are integrated into broader health and social information systems (OECD, 2020-2021[12]). Nevertheless, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) has compiled the available information on access to palliative care in Canada in its latest report on the topic (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018[43]). Japan has two surveys which are undertaken every few years and target people who have experienced cancer or bereaved families of people who have died from cancer, but they do not use established evaluation indicators nor validated PROMs or PREMs. Nevertheless, they serve as useful surveys to capture the experience of families at end of life.

Figure 6.3. Nearly half of OECD countries report a lack of systems to monitor and evaluate palliative care experiences and outcomes

Countries reported severe data constraints when attempting to collect data on hospitalisation at the end of life for the OECD pilot data collection on end-of-life care. The lack of interlinked data hampered the collection of many indicators as it is possible to look at hospital admissions but not necessarily for those who died within a given period. As an example, Belgium is not able to follow up with patients after they leave the hospital, while Germany reported not being able to link databases as needed. Data on medication used at the end of life and on the length of stay in palliative care programs were the least available across countries. The OECD National Health Data Infrastructure and Governance survey conducted in 2020‑21 highlights that 12 out of the 23 respondent countries claim to not use data linkage at all or in less than 60% of their databases for the same purpose (Oderkirk, 2021[44]).

Without reliable indicators and its monitoring, it remains challenging to provide information on the progress of end-of-life care within a country as well as to benchmark countries internationally. Indicators can inform decision-makers about the gaps and challenges in care provision and can be used to decide resource allocation and strengthening activities. With the absence of such indicators, it is challenging for countries to establish baselines, as is currently the case.

6.2.4. Weak research generates information gaps and can hinder adequate policy making

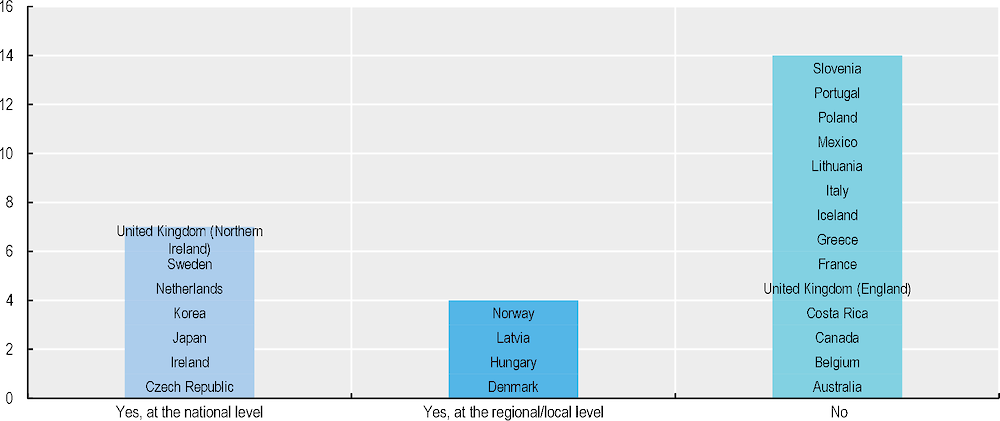

A research agenda in end-of-life care remains rare: most surveyed OECD countries (14 out of 25) do not possess a research agenda for EOLC at the national, regional, or local level. Such agenda would help provide strategic direction on how effort and resources will be focused and provide research priorities. It would encompass research on different areas such as mental health service improvement, pharmaceutical development, biomedical research, or other areas related to EOLC (Figure 6.4). Less than 30% of surveyed countries (Czech Republic, Ireland, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom (Northern Ireland) possess a research agenda at the national level, while 16% of countries have developed research agendas (Denmark, Hungary, Latvia, Norway) at the local level. In Canada, despite the Framework on Palliative Care recognising research on this topic as a priority, no national research agenda for EOLC exists. Nevertheless, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research provides funding for palliative care research (OECD, 2020-2021[12]).

Figure 6.4. Most countries report having no end-of-life care research agenda

In several countries, research on end-of-life care is underfunded and remains limited, compared with studies into the prevention and cure of life‑limiting conditions. In the United Kingdom, despite the high number of publications compared to other European countries, less than 0.3% of the GBP 500 million spent on cancer research in the United Kingdom is allocated to palliative care. Funding for non-cancer conditions is likely to be even less (Higginson, 2016[10]). Similarly, in the United States, a study reported that from 2011 to 2015, the 461 grants related to palliative care research awarded by the NIH in the United States represented 0.2% of total NIH research awards (Brown, Morrison and Gelfman, 2018[45]). Three NIH institutes – the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute for Nursing Research, and the National Institute on Aging – accounted for 80.2% of all awards distributed for palliative care in the United States (Brown, Morrison and Gelfman, 2018[45]). Aldridge et al. point out that the limited investment in palliative care research may be attributable to there being no federal agency specifically charged with a focus on palliative care and on persons with serious illness, with NIH institutes being largely disease‑specific (Aldridge et al., 2016[46]).

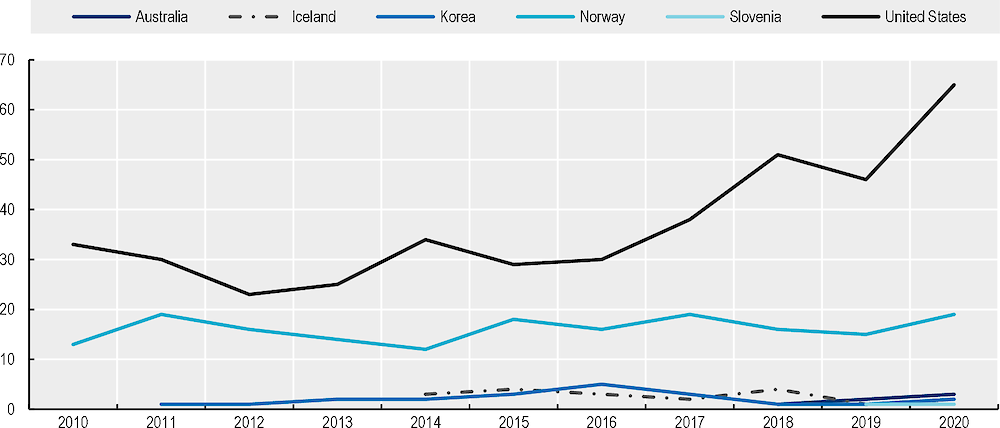

Among the OECD countries for which data was available, public funding for EOLC/palliative care research seems to have fluctuated in recent years. The investment increased in the years following the World Health Organization’s (WHO) first-ever resolution to integrate palliative care into national health services, policies, budgets, and health care education, in May 2014. In particular, public funding in Norway recorded a peak in 2014 (USD 3.6 million in PPP), in Korea in 2017 (USD 1.5 million in PPP) and in Ireland in 2019 (USD 1 million in PPP). Funding has since then decreased in many countries. One exception is Australia, whose data are only available for 2018‑20, and for which public funding for research in EOLC/palliative care grew in those years (Figure 6.5).

Figure 6.5. Public funding for end-of-life/palliative care researched fluctuated in recent years

Together with the magnitude of public funding, the number of publicly funded research projects is also an indication of amount of research dedicated to these topics. Among the OECD countries that provided data, the United States undertook by far the highest number of publicly-funded research projects reaching 65 projects in 2020 – a number that has increased over time. The number of projects as well as the amount of public funding remains small in this area compared with other health research topics. In comparison, there were 630 research grants in the United States as of mid‑2021 for cancer (American Cancer Society, 2021[47]). In other OECD countries, the number of projects remains limited and has been stable or it has decreased. In 2020, Norway funded 19 projects, while Australia, Iceland, Korea, and Slovenia had either 1 or 2 public funded research projects on the topic (Figure 6.6). According to an analysis by the European Association for Palliative Care, the number of scientific publications on palliative care between 2015 and 2018 varied widely across European countries. The United Kingdom recorded the highest number (2 448 publications), followed by Germany (1 153), France (814), Italy (698), the Netherlands (650) and Spain (627). Central and Eastern European countries recorded the lowest levels, with fewer than 10 publications across the three years analysed (Arias-Casais N, 2019[39]).

Figure 6.6. The number of publicly funded projects varies widely across OECD countries

Experts point to significant research gaps in palliative and end-of-life care and a weak and inconsistent evidence base, as a result of lack of prioritisation and underfunding (Evans, Harding and Higginson, 2013[5]). There are methodological gaps, as studies remain observational instead of based on evaluation and there only a small number of clinical trials have been conducted (Sonja McIlfatrick, 2018[48]). A systematic review of the literature found that gaps in research study design were present in 40% of the papers, with a lack of studies following people over time, pointing to the need to improve recruitment of study participants and use of randomisation (Antonacci et al., 2020[49]). Palliative care has historically faced problems conducting study designs like randomised control trials due to the ethical complications and the quality of studies is often low (Clark, Gardiner and Barnes, 2020[50]). Similarly, because of ethical and medical challenges, studies are more often focused on providers rather than highlighting the views and experiences of patients (Hasson et al., 2020[51]).

Research in end-of-life care is also predominantly disease‑specific, while there is a lack of evidence on some socio-demographic groups. Study design includes less often those with chronic conditions and people living with multi-morbidity or the ‘oldest-old’ (people 80 or above). Research related to experiences and practices of end-of life care in long-term care facilities and hospices is lacking, with much research hospital-based (Antonacci et al., 2020[49]). Interviewed experts also point out to research on cancer, followed by dementia, while research on other diseases at the end of life is rarer. As an example, in 2018 in the United Kingdom, Cancer and Neoplasms were the second most funded area of health research, after the research on generic health relevance. Research on cardiovascular diseases, respiratory, renal, and urogenital diseases, which are also likely to require end-of-life care, was much smaller and represented less than one‑third of the expenditure on cancer research (Mikulic, 2020[52]).

Additionally, there is a lack of strong evidence for important topics highlighting the appropriateness and affordability of care. Gaps in research evidence exists in appropriate timing of introduction of palliative care, and innovative models for delivering care such as how services should be delivered, particularly outside hospitals (Philip and Collins, 2020[53]). Further gaps in knowledge can be found in the provision of culturally sensitive care, with a lack of culturally appropriate services meaning those at the end of life from diverse cultural backgrounds may feel uncomfortable with current palliative services or feel dissuaded from using or accessing end-of-life care entirely (Antonacci et al., 2020[49]). Related to that, reasons for inequalities in access and policies to promote equitable access to care depending on the location and socio‑economic or cultural group remain poorly documented and understood (Hasson et al., 2020[51]). Understanding grief and bereavement and support and needs of carers is also another area for which more research is needed (Antonacci et al., 2020[49]). Overall, there is a lack of research on cost-effectiveness and evaluation of interventions.

6.3. What policies are being pursued to ensure care is well-governed and evidence‑based?

6.3.1. Promotion of end-of-life care expertise in community settings and the use of technology can make end-of-life care systems more adaptable

It is important for end-of-life care services to respond rapidly. This requires ensuring that adapted protocols for symptom management are available, shift more resources into the community (including to non-specialists), and use technology to communicate with patients and carers (Etkind et al., 2020[54])

Integrating end-of-life care into pandemic and crisis planning would be crucial to avoid shortages and poor quality of care. In the future, to ensure better preparedness, it would be paramount to include EOLC experts in task forces and decision-making during emergencies in facilities to allow the prioritisation of the needs of people at the end of life. This strategy, together with establishing palliative care guidelines and protocols on the provision of EOLC during emergencies would ensure more expertise on this topic in different care settings. Several countries have already moved in that direction. Some countries issued specific guidelines on end-of-life care, while others included end of life care and palliative care within broader guidelines or guidelines for long-term care. Luxembourg published specific guidelines on providing EOLC during the pandemic and Ireland published information around the transfer of people at the end of life across settings of care, provided information around the supportive therapies for COVID‑19 patients at the end of life and around ACP in residential settings (Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[11]). In the United Kingdom (England) already in April 2020 guidelines highlighted that palliative care support should be made available where appropriate and in collaboration with relevant health and social care providers (Adelina Comas-Herrera, 2020[24]). In the United States, the CDC also developed recommendations and resources for people with serious illness and their relatives, as well as for clinicians to support them in providing the right end-of-life care. Care settings-specific guidance was also available (Adelina Comas-Herrera, 2020[24]). In Canada, general guidelines on COVID‑19 included considering the potential increase in demand of EOLC services. Guidelines advised, among other measures, to prioritise community support for people at the end of life, when possible, to reduce exposure to COVID‑19 (OECD, 2020-2021[12]). In 2021, Canada also published a report summarising the effects that the pandemic had on end-of-life care, the lessons learnt, and successful measures put in practice to minimise end-of-life care services disruption (Health Canada, Healthcare Excellence, CPAC, CHCA, 2021[55]). Belgium and France included measures to ensure the provision of palliative care within the guidelines on the care and support for older people during the COVID‑19 crisis (Government of France, 2020[56]), while Norway included a section on palliative care among general COVID‑19 guidelines (Helsedirektoratet, 2020[57]).

Improving the use of advance care planning (ACP) and improving the availability of specific supplies in different care settings would allow carers to be better prepared for such events (Santé publique, 2020[19]). The pandemic heightened the importance of having conversations around preferences recorded in the form of ACP and having a surrogate decision-maker in the event of rapid deterioration of prognosis, bleak prospects for recovery and transfer across care settings. The United Kingdom (England) published specific guidelines for children and young people with end-of-life care needs, who were cared for in a community setting, as well as clinical guidance for supporting compassionate visiting arrangements for those receiving care at the end of life. Guidance on verification of death in times of emergency and ACP were also issued during the pandemic (OECD, 2020-2021[12]). Innovations to promote the use of ACP have also taken place at a small scale during the pandemic, which could be implemented more widely. For instance, in the United States, a pilot was performed coupling a highly trained palliative care hospice staff with staff from primary care and resulted in a great outreach for the completion of ACP after one single discussion (Gessling et al., 2021[58])

The COVID‑19 pandemic has accelerated the recognition that all people working in health services should be competent in supporting those dying and their families. To preserve continuity of care, it is important to conduct rapid training and find better ways of integrating specialist expertise within primary and community settings which can respond swiftly to increased needs and reduce disparities in access. Nursing homes would also need to ensure the availability of palliative care advice. Enhanced palliative care and end-of-life care provided at home or in a home‑like setting requires training of primary care professionals and likely a stronger development of hospital at home approaches, as an alternative to hospital admission or as step-down care after a hospital stay with sufficient medical supplies for symptom management and staffing. In this sense, Belgium recommends the implementation of a middle care level of palliative services for those no longer requiring hospitalisation but not yet well enough to stay at home or in a nursing home (Service public fédéral, 2020[21]). In the United States, a project piloted at hospitals in collaboration with the Center to Advance Palliative Care, is developing an online platform to provide specialist palliative care remotely, while simultaneously developing training for generalist palliative care to be given to individuals within a given hospital system (Blinderman et al., 2020[59]). Luxembourg made further efforts to ensure that people in need of EOLC could receive adequate care at home, without being hospitalised, when possible. People dying at home or in nursing homes had emergency access to a medication kit containing morphine and other EOL medication to give comfort at the end of their life. They could also have emergency access to oxygen therapy at home and in nursing homes, even at night and during the weekends. Oxygen extractors were distributed upon request within 3 hours between April 2020 and March 2021, within 12 hours between April 2021 and March 2022 and within one day since then. Canada also developed the use of palliative symptom management kits, which could be kept in community health care providers or at patients’ homes (Health Canada, Healthcare Excellence, CPAC, CHCA, 2021[55]). In July 2020 Italy increased investment in home care to improve the availability of palliative care at home. The investment specifically aims at ensuring adequate home care services across all regions to reduce regional disparities in the access to care.

Wider availability of training would help sharing the expertise on EOLC among different care workers. The Swedish Register of Palliative Care (SRPC) developed knowledge support to respond to the pandemic. It produced a checklist of medicines that were widely distributed free of charge to municipalities and regions to minimise the disruption to the provision of EOLC during the crisis. Canada provided training on evaluating respiratory distress to care teams including a set of professionals (physicians, pharmacists, and nurses) (Health Canada, Healthcare Excellence, CPAC, CHCA, 2021[55]). The National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW) also supported and shared knowledge during the crisis, for instance through the publication of Q&As for health care professionals (OECD interviews, 2021). Slovenia activated a telephone counselling service to provide health care workers with adequate information around the use of palliative care services (Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[11]). The University of Chile provided free access to palliative care training to all health care professionals during the pandemic (Universidad de Chile, 2020[60]). Several countries have started to develop online training. In Canada, Pallium Canada offered learning modules and webinars – the Learning Essential Approaches to Palliative Care – targeting health care practitioners providing EOLC during the pandemic. The training fees were waived for six months, and the training targeted all health care providers, reaching 11 000 registrations (Pallium Canada, 2021[61]). In Norway, in September 2020, the National Competence Service for Aging and Health published a new free e‑learning course on palliative care for the older people and seriously ill people with COVID‑19. The training is open to all health care workers at the municipal level and touches upon the symptom supporting, clinical observations to identify health deterioration and palliative care (National Competence Service for Aging and Health, 2020[62]). Portugal is planning to make online courses on palliative care available for all health care staff before the end of 2022.

In addition to supporting health care professionals, some countries also developed support for informal caregivers and people living with serious illness and reaching the end of their life. Austria developed telephone hotlines, online support networks, guidance, and resources, while the Austrian Red Cross offered online courses for informal caregivers (LTCCOVID, 2020[63]). Canada provided online resources for grief and bereavement support to caregivers and family members and France provided psychological support to patients and their families (Government of Canada, 2020[64]; Government of France, 2020[56]). The United Kingdom provided tips on mental well-being together with information on where to seek psychological support, while in the United States the CDC published recommendations for people living with serious illnesses and their caregivers (Adelina Comas-Herrera, 2020[24]; Department of Health and Social Care, 2020[65]).

The use of technology at the end of life could be further explored to improve co‑ordination of care and care continuity, reduce the movement of patients across settings of care and ensure good communication between patients and their relatives during emergencies. Good use of technology can simplify access to end-of-life care by allowing the sharing of documents across service providers and between patients and clinicians. During the pandemic, technology has led to reducing the movement of people at the end of life across care settings, facilitating the use of care at home or in nursing homes. Finally, the use of technology facilitated contacts between patients and their relatives, who were not always able to access care facilities. Of the 25 OECD countries surveyed (Figure 6.7), 10 (40%) indicated they used digital technology to make EOLC services more accessible prior to COVID‑19 pandemic, for instance to receive medical advice in video call, connect patients and family via digital devices, or access documents and medical records online, while 6 countries (24%) made it available during the COVID‑19 crisis. 5 (20%) have not made any use of digital technology.

Figure 6.7. Since the COVID‑19 pandemic, most OECD countries use technology to improve accessibility of end-of-life care services

Some countries used technology prior the pandemic, but its further development boosted the use of teleconsultations and ensured contacts between patients in care facilities and their relatives. This was the case of Belgium, which used technology to ensure accessible EOLC services already prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, but this use accelerated during the pandemic. Nevertheless, the use of technology is not yet regulated by a legal framework, except for access to medical records (OECD, 2020-2021[12]). In Canada, the Ontario Telemedicine Network is part of a government agency and provides virtual palliative care. It consists of the provision of palliative care services at home to minimise the movement of people at the end of life across settings of care. Among the services provided, people can receive virtual visits with doctors, mental health coaching and short training on symptom monitoring. People are also provided with easy-to‑use health kit and will be assigned a nurse to virtually keep in touch with (OTN, 2021[66]). In the United States, prior to the COVID‑19 crisis digital technology was used for EOLC, however the COVID‑19 pandemic has led to changes in the use of telehealth services. The Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services has provided Medicare hospices flexibilities in telehealth and telecommunications technology during the public health emergency. Hospice providers can provide services to a Medicare patient receiving routine home care through telecommunications technology, while face‑to-face encounters for purposes of patient recertification for the Medicare hospice benefit are conducted via telehealth means (Nakagawa et al., 2020[67]). Moreover, Sweden is currently developing some self-monitoring tools (e.g. monitoring weight and exhalation). The project is still in the experimental stage (OECD interview, 2021). Online bereavement support groups may also assist grieving family members (Fadul, Elsayem and Bruera, 2020[25]).

In recent years, and particularly during the pandemic, there has been increasing interest towards the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in health care broadly, including EOLC. The potential of AI to predict clinical outcomes was already explored back in 2018 (Rajkomar et al., 2018[68]), but the COVID‑19 crisis has boosted the use of AI as a diagnostic tool and an epidemiological instrument. As an example, the COVID‑19 detection neural network (COVNet) is a tool used to diagnose COVID‑19, which demonstrated accurate and able to distinguish COVID‑19 from other lung conditions and pneumonia (Li et al., 2020[69]) (Kedia, Anjum and Katarya, 2021[70]). To what extent AI can be applied to support diagnoses and health care provision is still under analysis. Nevertheless, examples of the use of AI to support clinicians to predict when a person is reaching the end of life already exist. In fact, recognising when a patient is dying and starting a conversation around death and dying at the right time often represents a challenging task for clinicians. In the United States, the Stanford University hospital, the University of Pennsylvania, and a community oncology practice in Seattle are using AI to scan patients’ medical records and notify health care workers when a patient is likely to die within a year. This tool allows clinicians to start conversations around death and care planning while the patient is still able to understand their health status and express care preferences (Robbins, 2020[71]).

6.3.2. Information-sharing and case management can contribute to seamless transitions and more integrated care

People receiving integrated EOLC appear to be more likely to die where they wish, to initiate palliative care earlier on, to receive less acute care and to experience better quality of the dying process (Groenewoud et al., 2021[72]; Vanbutsele et al., 2020[73]). Improving care co‑ordination at the end of life involves, in part, policies to enhance information sharing, the use of case management or other innovative models to enhance integration which are detailed below.

Poor communication and information sharing between services is a barrier to achieving high-quality care at home, especially due to out-of-hours professionals not having full-records (Standing et al., 2020[74]). In turn, increased communication and collaboration across service providers can lead to earlier detection of EOLC needs, avoiding unnecessary acute treatments at the end of life (Groenewoud et al., 2021[72]). Part of information sharing starts with guidelines to standardise forms, clinical documentation, and assessment tools. A review of the evidence from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence established that low-cost methods of information sharing, such as patient held records, would be likely to reduce costs by reducing the duplication of tasks by numerous health care professionals (NICE, 2019[75]). Results from the survey conducted on OECD countries indicate that of the 23 countries which responded, 64% (16) had a system of secure electronic note sharing for EOLC at national, regional, or local level (OECD, 2020-2021[12]).

Shared electronic systems or electronic notes sharing helps can help ensure continuity of information for professionals delivering care. Among the countries where electronic notes sharing is in place, Australia has national data on the activity and characteristics of palliative care services, which is collated in the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s (AIHW’s) Palliative Care Services in Australia online web report (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021[76]). Additionally, Australia has a national digital health record system called “My health record”, where information about the patient can be uploaded and shared across the health care system. The system is not specific for EOLC, but some features that can be particularly useful for people reaching the end of their life, such as the possibility to upload ACP and to nominate a person close to the patient who can help manage the digital records. The system is still voluntary, thus there is no full coverage of the population (OECD, 2020-2021[12]). Costa Rica has the Unique Digital Health Record (EDUS), at public health care facilities, where all care services received by the patient can be shown, including the control of pain and symptoms (OECD, 2020-2021[12]). In the United Kingdom, the Electronic Palliative care Co‑ordinating Systems (EPaCCSs) provides several different electronic solutions that aim to capture patient wishes and preferred place of death and improve co‑ordination of care in real time, through enabling the sharing of information across health and social care services. Other countries are making efforts to develop electronic notes sharing, such us the Netherlands. A current project in the Netherlands is aiming to achieve four main goals: i) strengthening integrated health care delivery across settings and sectors; ii) enabling comprehensive public health monitoring and management; iii) capitalising on recent innovations in health information infrastructure and iv) fostering research and innovation in technologies and treatments that improve health and health care (OECD, 2022[77]). Norway collects data on the use of drugs by prescription, with the National Prescription Drug Registry (NorPD) able to breakdown data by gender, age, and geography (Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), 2021[78]). There has also been discussion around creating one comprehensive medical record per patient, merging different registries, but no practical change has taken place yet (OECD interview, 2021).

A meta‑analysis highlight that the best practice model for palliative care includes case management which requires co‑ordination of services beyond the health care sector, including social services and pastoral care. This would involve the integration of specialist palliative care with primary and community care services, and enable transitions across settings, including residential aged care. Such a model was associated with significantly reduced time in hospital and caregiver burden (Luckett et al., 2014[79]). Intermediate palliative care is provided as an alternative to hospital admission or as step-down care after a hospital stay and can be provided at home or in dedicated intermediate care beds in community hospitals or care homes: it is often referred to as hospital at home. Intermediate palliative care at home was associated with increased odds of dying at home and reduced symptom burden (IHUB, 2019[80]).

Many countries also developing innovative solutions such as care networks to promote care integration across care settings. In Belgium, mobile units from hospitals act as a liaison between the hospital and home organising discharges from hospitals and contacting primary and secondary teams for the patient. The country has also introduced an initiative to transfer knowledge on EOLC across professionals. Palliative care physicians and home care physicians meet with four other colleagues without a specialised background on EOLC, to organise peer education sessions and spread professional knowledge around the topic. Since 2010, Italy provides palliative care through networks of palliative care (Reti locali cure palliative and reti regionali cure palliative). They consist of networks of palliative care providers that communicate and co‑ordinate to ensure that patients have adequate palliative care that is people centred, integrated and available to everyone who needs it. Professionals are regularly trained and provide care according to an integrated and multiprofessional patient pathway (Ministry of Health - Italy, 2021[81]). In Italy, a model of clinical governance for the development of Palliative Care Local Networks was developed and piloted for the development of integrated pathways for people in need of palliative care (Fondazione G. Berlucchi & Fondazione Floriani, 2015[82]).In Sweden there is an integrated care programme for people in need of EOLC regardless how close they are to the end of their life. The programme aims to integrate palliative care in the treatment of diseases as early as possible. It is developed in the framework of the co‑operation with Regional Cancer Centres (RCC) and the Sweden’s Municipalities and Regions (SKR) (Swedish Palliative Care Register, 2020[83]).

OECD countries are also putting in place further efforts to improve the integration of palliative care across different government departments and with primary care. In Australia, several measures are currently in place to improve integration on the provision of end-of-life care. The National Palliative Care Strategy (2018) included a specific goal related to governance, which aims at developing a governance structure under the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, involving all state and territory governments and the national Australian Government working together. Moreover, the Greater Choice for At Home Palliative Care (GCfAHPC) measure provides funding to improve the integration of palliative care provision across Primary Health Networks (PHNs). The initiative aims at improving the co‑ordination across health services, developing a system that allows early referrals to palliative care and strengthening the community support for people’s relatives. It also aims at providing resources to local communities and work with local providers to ensure the availability of home‑based palliative care to meet the communities’ needs for palliative care. The pilot was introduced in 2017 across 11 (out of a total of 31) PHNs that were selected to participate. From 1st of July 2021 all PHNs received funding to co‑ordinate palliative care activities in their regions (Australian Government, 2021[84]). In Northern Ireland, the Palliative Care in Partnership (PCIP) programme aims to provide a single direction and regional work plan for the continuing improvement of palliative and EOLC across all care settings. PCiP aims to ensure that people who would benefit from a palliative care approach have the same opportunity for support and service regardless of where they live or what life limiting condition they have been diagnosed with, with recent focus on improving EOLC initiatives across the government departments.

A systematic review of the evidence indicates a clinically important benefit of a care co‑ordinator in reducing the use of community services, hospital and ICU admissions and visits, visits to accident and emergency and death in hospital (NICE, 2019[75]). For instance, in Ireland, a palliative care nurse liaison to ensure that the discharge plan is in place prior to discharge, establishes links with the primary care team and undertakes a follow up visit, if deemed necessary (Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, 2010[85]). Lincolnshire, in England (United Kingdom), established the Palliative Care Co‑ordination Centre (PCCC) to co‑ordinate the provision of community care for people nearing their end of life. It centralised the co‑ordinating the booking of community care for patients nearing the end of their lives. The PCCC improved care co‑ordination while also reducing the burden of work of nurses, by taking up administrative tasks (King's Fund, 2011[86]).

6.3.3. Linking data and designing appropriate indicators should enhance monitoring

To ensure high quality EOLC is provided to those in need, it is paramount to improve data-quality and availability. EOLC indicators require linkages across mortality data registries and data on care provision (e.g. settings of care, enrolment in palliative care programs, pharmaceuticals). Several institutional barriers including poor institutional arrangements and governance models currently undermine the linkage and the sharing of data among public authorities. Only 16 countries have mortality data containing an identification number which could be used to link datasets and 10 countries (Australia, Austria, Czech Republic, Finland, Israel, Korea, Latvia, the Netherlands, Slovenia, the United States) regularly link health care data to mortality data (Oderkirk, 2021[44]).Comprehensive health data governance with legislation and policies that allow health data to be linked and accessed can help harness the potential of data in end-of-life care. Experts also highlighted the need to build expertise in the field of safe data linkage techniques and looking at opportunities to gather other data sets (Davies et al., 2016[7]).

Certain countries have moved forward in linking data or undertaking surveys on this topic. Scandinavian countries, in particular, make widespread use of shared unique identifiers, strong collaboration between data holding bodies, an established legal basis for the collection and use of data, and broad public approval for the use of linked administrative data (Davies et al., 2016[7]). Australia developed the Australian Palliative Care Outcomes Collaborative (PCOC), which comprises data on specialist palliative care. Australia has further focused on data development and created a Palliative Care and End of Life Care Data Development working group to improve EOLC data collection and development. Experts from Korea reported the existence of a web-based system to monitor basic information on terminally ill patients and the provision of EOLC. Germany has launched the Palli-MONITOR project, which allows people receiving palliative care and their relatives to communicate their physical, psychological, social, and spiritual symptoms to the teams through their smartphone, tablet, or computer, on a weekly basis. As of 2022 the initiative is ongoing and an observational study is planned to evaluate its success (Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss, 2022[87]). In Japan, surveys on patient experience and surveys reported by bereaved families conducted by National Cancer Centre include questions on palliative care, while in Estonia, it is a legislative requirement to carry out patient experience surveys for every health provider. In the United States, while Government-wide national systems are not in place, the CAHPS® Hospice Survey samples the primary caregivers of deceased hospice patients and covers topics including treatment of symptoms, hospice team communication, caregivers’ own experience, and rating of hospice care (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020[88]).

Experts in several countries have highlighted that data on EOLC could be produced using routine data or through information provided via primary care. In Belgium and the Netherlands, to collect a population-based level end-of-life care data across patient groups and care settings, a collaboration was set up with the nationwide Sentinel Network of General Practitioners in both countries, which was followed by Spain and Italy. All participating Sentinel GPs were asked to fill in a short registration form on the care the deceased received in the last phase of life (Van den Block et al., 2013[89]). A similar data collection via a questionnaire sent through GPs was piloted in Australia coupled with data extraction from electronic medical records on medication and investigations and highlighted the feasibility of collecting such data but the need to address the challenge of non-response rate (Ding et al., 2019[90]). Other countries are still underutilising the potential of data. Safe and ethical secondary use of data is often cited as a barrier preventing access to routine data for research.

Monitoring and evaluating end-of-life care using indicators can help to understand effectiveness, performance and determine priorities for improvement (NSQHS, 2021[91]). High data quality and availability require the use of standardised data collection tools and registries but also a discussion on the right indicators to measure good quality outcomes, and a broader range of population-based metrics, such as including the number of hospital admissions towards the end of life. Some countries are still currently working on the development of performance indicators. This is the case of Costa Rica, where the National Center for Pain Control and Palliative Care recently developed indicators and quality standards that are under analysis to be implemented in the future (OECD, 2020-2021[12]). Luxembourg is also planning on reducing avoidable admissions at the end of life for people living in nursing homes since the pandemic and will be monitoring this indicator.

Some countries have already well-established datasets for end-of-life care or indicators. In Sweden, the Swedish Register of Palliative Care is a central source of information with an extensive data collection used by governmental bodies, caregivers, and researchers (OECD interview, 2021). The register was created in 2005 and builds upon a questionnaire on end of life (ELQ) composed by 30 questions. The questionnaire is answered by health care staff after the deaths of the patient and focuses on the care provided in the patient’s last week of life (The Swedish Register of Palliative Care, 2021[92]). In Ireland, National Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are included in the Health Safety and Executive (HSE) Annual Service Plan, while monthly Management Data Reports include accessibility measures (access to specialist inpatient bed and triage in inpatient care or specialist palliative care services within the community or treatment within their home), care standards (multidisciplinary care planning), as well as specialised measures for children’s palliative care. In the United Kingdom, since 2013 a team at the Cicely Saunders Institute, King’s College London, leads the Atlases of Variation, which helps identify unwarranted variation and assess patient populations and outcomes, as well as service provided, to support improvement (National End of Life Care Intelligence Network (NEoLCIN), 2018[93]). A separate indicator reporting the percentage of deaths with three or more emergency admissions in the last three months of life is used to measure the quality of EOLC services, and how well people are supported in the community (Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, 2020[94]). At the local level in England the use of dashboards is promoted to monitor outcomes and inequality.

6.3.4. Making end-of-life care a research priority is critical to address knowledge gaps

Investment in palliative care research is critical to building the evidence base for palliative care integration and securing funding for the expansion of palliative care services across settings (Aldridge et al., 2016[46]). Investment in EOLC research can support informed decision-making, facilitate quality improvement of EOLC services, and foster knowledge‑sharing, informing national and international policy making. For instance, patient-reported improvement in breathlessness using an integrated support service has shown the potential to improve patient quality of life and symptom control with no additional health care costs (Higginson et al., 2014[95]), and has attracted interest internationally (Higginson, 2016[10]). A meta-review has demonstrated that some palliative care models may contribute to improvements in quality of care via lower rates of aggressive medicalisation in the last phase of life, accompanied by a reduction in costs (Luta et al., 2021[96]).

There is a need to continue to build capacity in many countries and address barriers to research. Such barriers include in part cultural barriers to discuss death and suffering among study populations. Greater awareness and reducing stigma around death through public campaigns will help to shift attitudes of researchers and the general public on this topic. More importantly, public efforts should also target addressing broader systemic barriers, especially the limited number of funding sources for palliative care, lack of well-trained investigators, as well as institutional capacity (Chen et al., 2014[2]). Moving forward, governments could encourage more research to overcome knowledge gaps which are particularly salient and prioritise funding for research with respect to timeliness of access, models of care and cost-effectiveness.

High quality EOLC research must include an approach that is methodologically sound to advance evidence on what works or not. Unfortunately, conducting the ‘gold standard’ randomised controlled trials (RCTs) is not always feasible because of the complex multi-morbidity in end-of-life care, difficulties in achieving adequate sample sizes, and high attrition rates. Visser et al. suggests nonetheless that high quality research can be achieved with non-RCT methodologies, but which have equivalent validity and size. This is possible through a pooling of resources and using multiple research tools in combination with a “mixed method” approach (Visser, Hadley and Wee, 2015[97]). Another possibility is the integration of routine assessments into clinical practice and the using clinical administrative databases. Similarly, researchers have suggested strategies to address sampling concerns with the development of a taxonomy to guide clinical trial recruitment but also supplementing this through statistical approaches to deal with missing data and attrition (Aoun and Nekolaichuk, 2014[98]).

Several OECD countries are promoting research in this area through funding and the development of specific research centres.

In Belgium the government finances one research group from the Free University of Brussels, which focuses on EOLC research. Moreover, in 2009 the Belgian Healthcare Knowledge Centre (KCE research institute) received public funding for research on EOLC (OECD interviews, 2021).

In Norway, the government does not have a specific fund for EOLC research, but when research funding is obtained from the EU, the Norwegian Government adds one‑third of the value to the grant, to incentivise research. Moreover, the Norwegian Cancer Society plays an important role in research, for instance by supporting the European Research Centre for palliative care (located in Oslo). The Norwegian Government also revises guidelines and national action plans on palliative care every 2 years, to incorporate the latest research results. (OECD interview, 2021).

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), in the United Kingdom, invested 22 million pounds over the past 5 years into EOLC research. The NIHR funded 16 partnerships in 2022 to establish networks and collaborations across the whole country. Furthermore, the Department of Health and Social Care commissioned research, due for publication in late 2022, on assuring quality and reducing inequalities in end-of-life care for people who die at home.

Similarly, the United Kingdom (Northern Ireland), France and the Netherlands have organisations supporting palliative care research.

The Northern Ireland Palliative Care Research Forum encourages collaboration among palliative care researchers and practitioners to improve research capacity and promote research initiatives and ideas that are relevant, important to service users and stakeholders, and improve practice and service delivery. Ireland has the All Ireland Institute of Hospice & Palliative Care, a collaborative of hospices, health and social care organisations and universities on the island of Ireland. The institute also has a Palliative Care Research Network including leading researchers from partner organisations that focus on palliative care research that has high impact, builds research capacity, and drives collaboration.

France created the national platform on end-of-life care in 2018, with the aim of improving the quality of research and to foster collaboration and networking among researchers. Since the establishment of the platform, research projects and thesis on end-of-life care have increased in France, with 10 additional projects in the time span of one years, between 2020 and 2021 (Plateforme nationale pour la recherche sur la fin de vie, 2021[99]). France has also included the improvement of EOLC research and the dissemination of resulting evidence in the national plan 2021‑24. The plan states the willingness of the ministry to further develop the national platform on end-of-life care and provide it with additional funding (French Ministry of Health, 2022[100]).