In most countries, hospitals account for the largest part of overall fixed investment and hospital beds provides an indication of the resources available for delivering inpatient services. However, the supply of hospital beds influence on admission rates has been widely documented, confirming that a greater supply generally leads to higher admission numbers (Roemer’s Law that a “built bed is a filled bed”). Therefore, beside quality of hospital care (see Chapter 7), it is important to use resources efficiently and assure a co‑ordinated access to hospital care. Increasing the numbers of beds and overnight stays in hospitals does not always bring positive outcomes in population health nor reduce waste.

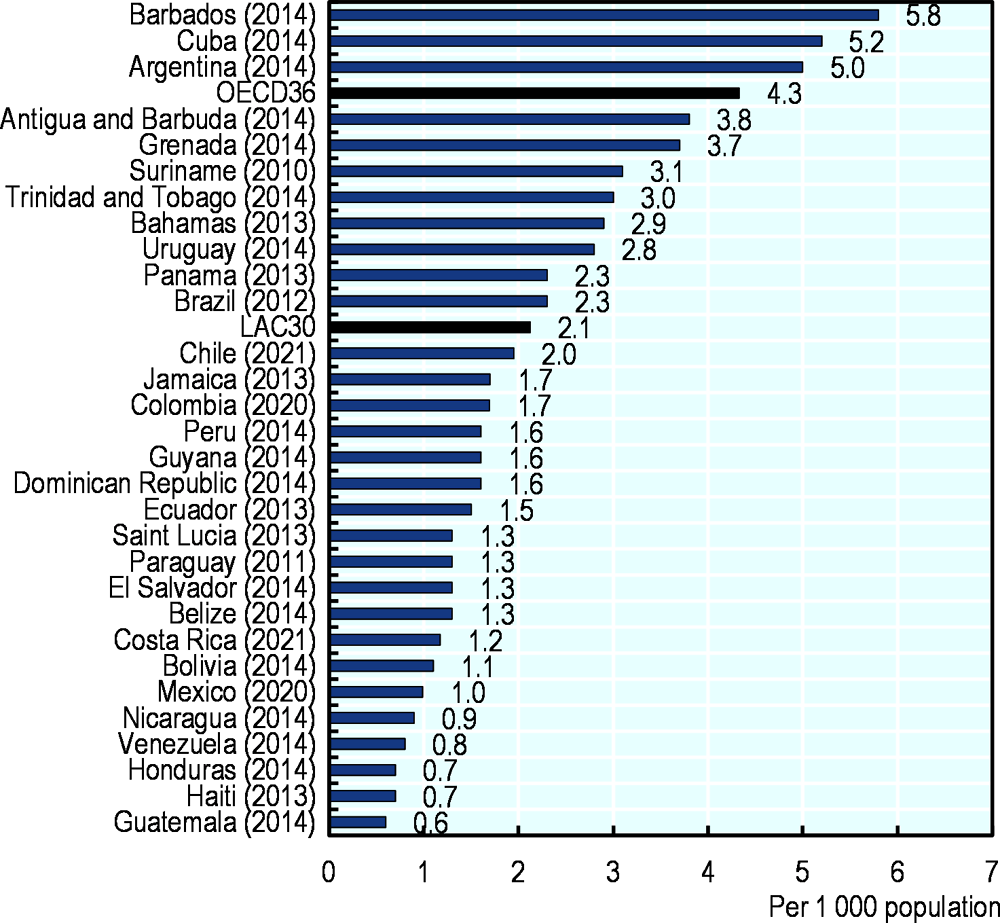

The number of hospital beds per capita in LAC is 2.1, lower than the OECD average of 4.3, but it varies considerably (Figure 5.7). More than five beds per 1 000 population are available in Barbados, Cuba, and Argentina, while the stock is equal or less than one per 1 000 population in Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Venezuela, Nicaragua and Mexico. These large disparities reflect substantial differences in the resources invested in hospital infrastructure across countries.

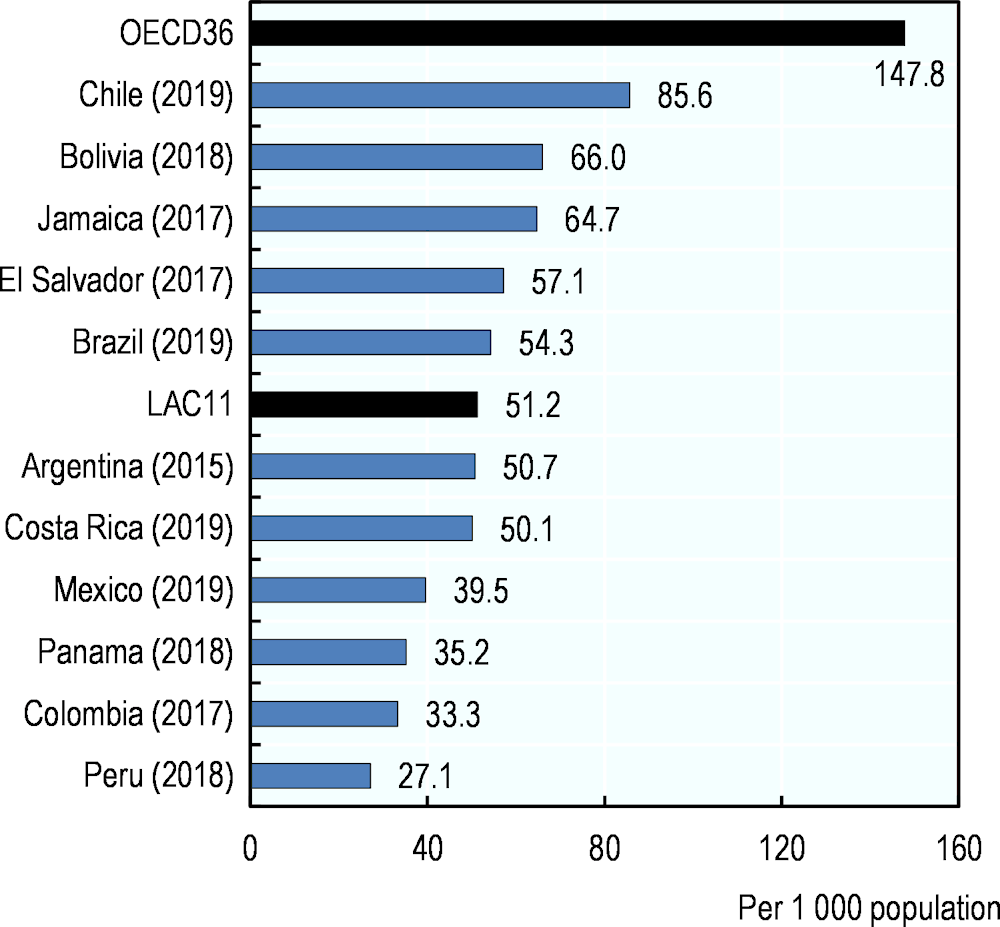

Hospital discharge is at an average of 51.2 per 1 000 population in 11 LAC countries with data, compared with the OECD average of 147.8 (Figure 5.8). The highest rates are in Chile and Bolivia, with over 85 and 66 discharges per 1 000 population in a year, respectively, while in Peru, Colombia, Panama and Mexico there are less than 40 discharges per 1 000 population, suggesting delays in accessing services. In general, countries with more hospital beds tend to have higher discharge rates and vice versa. However, there are some notable exceptions. El Salvador and Bolivia have a low number of beds but a relatively high discharge rate, while Argentina has a higher density of hospital beds than the OECD average but a discharge rate lower than the LAC11 average.

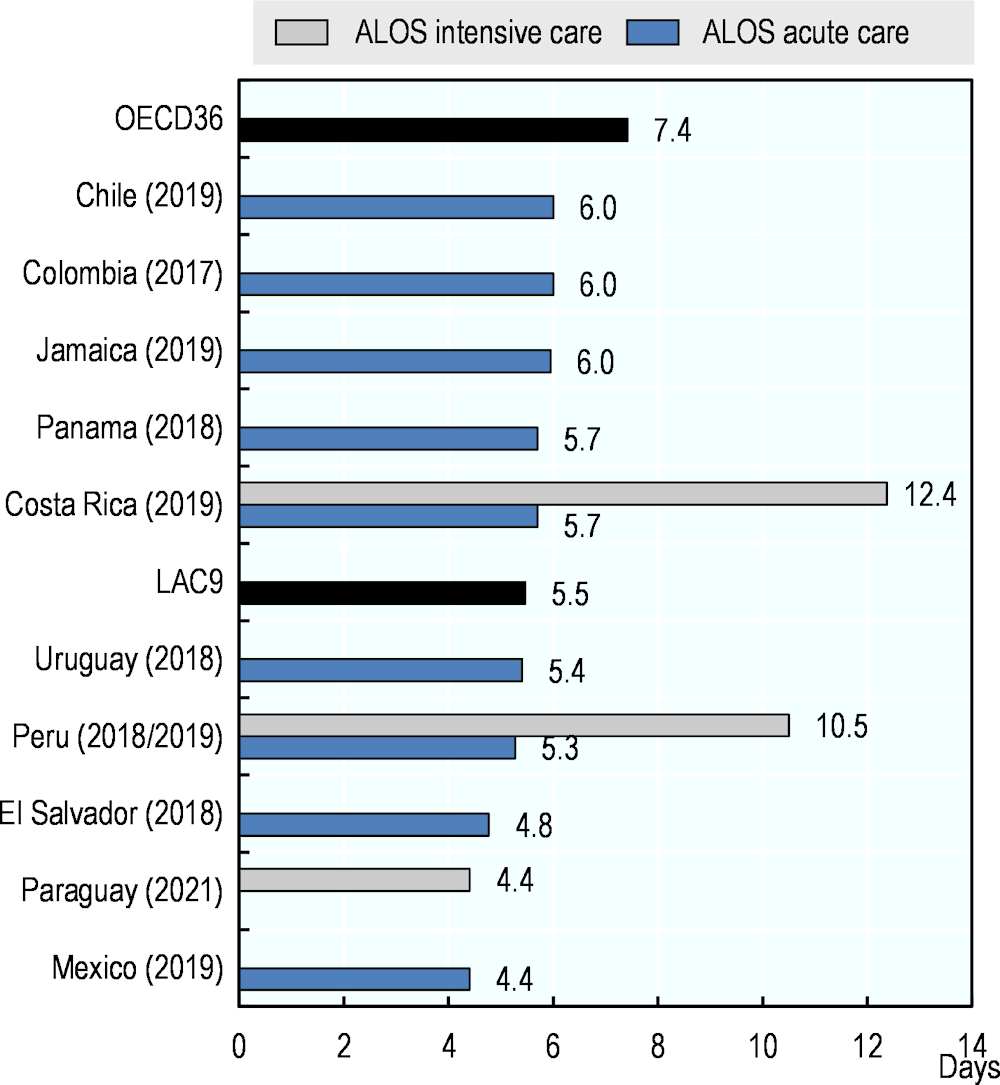

In nine LAC countries with data, the average length of stay (ALOS) is 5.47 days, lower than the OECD average of 7.42 (Figure 5.9). The longest ALOS is of 6 days Chile, Colombia and Jamaica, while the shortest length of stay is under 4.4 days in Mexico. The ALOS assesses appropriate access and use, but caution is needed in its interpretation. Although, all other things being equal, a shorter stay will reduce the cost per discharge and provide care more efficiently by shifting care from inpatient to less expensive post-acute settings. Longer stays can be a sign of poor care co‑ordination, resulting in some patients waiting unnecessarily in the hospital until rehabilitation or long-term care can be arranged. At the same time, some patients may be discharged too early, when staying in hospital longer could have improved their health outcomes or reduced chances of re‑admission (Rojas-García et al., 2017[1]).

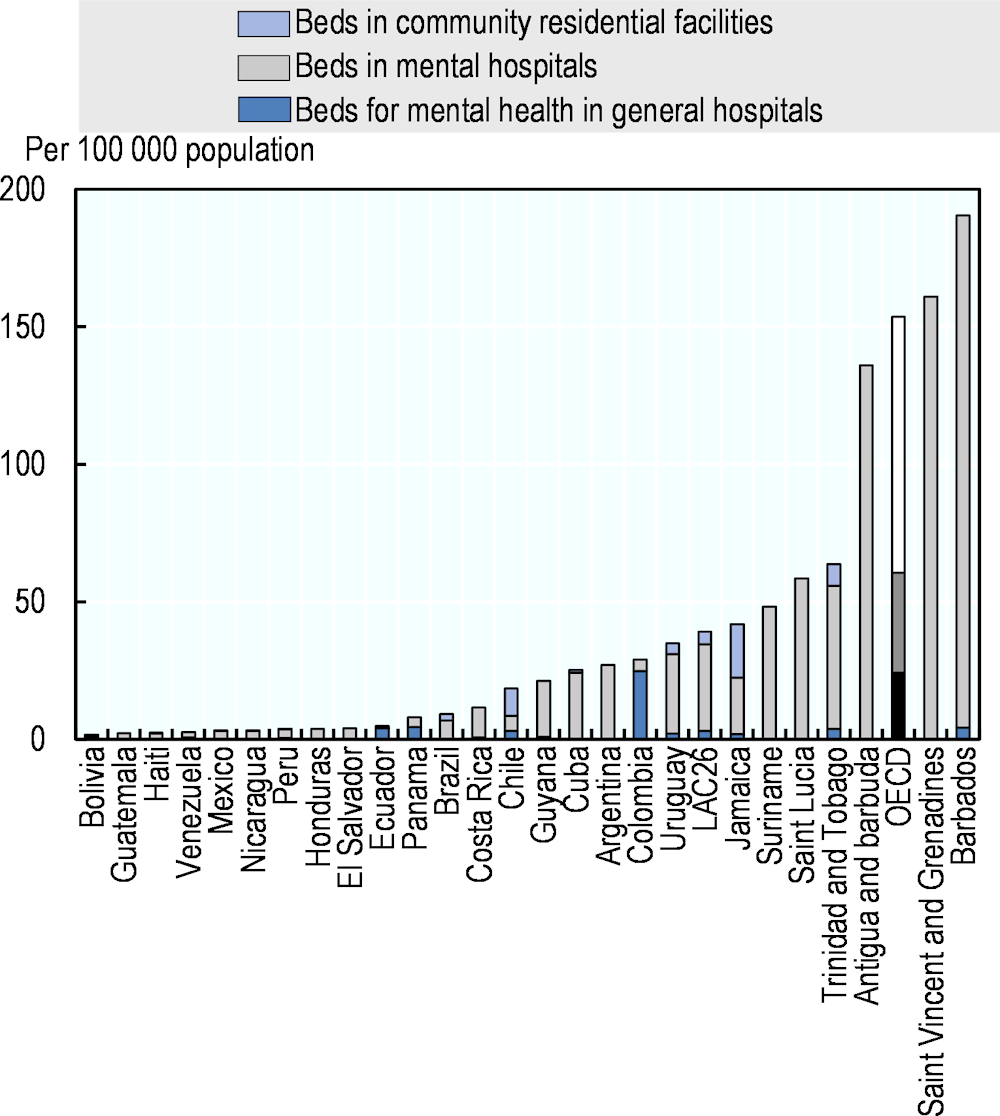

When having a look specifically at mental health beds, LAC26 has on average 39 beds per 100 000 population, from which more than 31 are in mental hospitals, this is around a quarter of the density in OECD countries on average, with over 160 mental health beds per 100 000 population, from which more than 186 are in mental hospitals. Only Barbados in LAC26 has a higher density of mental health beds than the OECD average, with more than 190 beds per 100 000 population. Bolivia, Guatemala, Haiti, and Venezuela have less than 3 mental health beds per 100 000 population (Figure 5.10).