Feeding practices of infants and young children heavily influence their chances of short-term survival and their capacity to realise their long-term potential. They contribute to healthy growth, decrease rates of stunting and obesity and lead to higher intellectual development (Victora et al., 2016[1]). Starting at the beginning of a woman’s pregnancy to the second birthday of her child, the first 1 000 days represent a key opportunity to ensure wellness and create the foundations of a productive and healthy life. Breastfeeding is often the best way to provide nutrition for infants. Breast milk provides infants with nutrients they need for healthy development, including the antibodies that help protect them from common childhood illnesses such as diarrhoea and pneumonia, the two primary causes of child mortality worldwide (see indicators on “Child mortality” in Chapter 3). Breastfeeding is also linked with better health outcomes as children grow older (Rollins et al., 2016[2]).

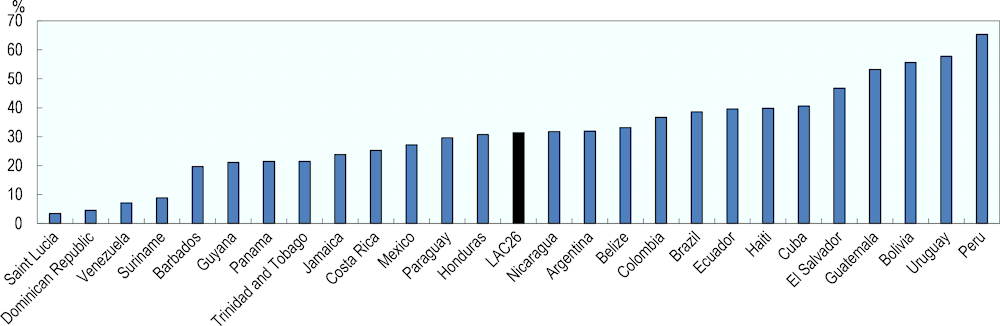

In LAC26, most of the countries reporting data have exclusive breastfeeding lower than the WHO goal with an average of 31% of children exclusively breastfed in the first 6 months of life (Figure 4.3). Over half of infants are exclusively breastfed in Peru, Uruguay, Bolivia and Guatemala, while the rate is lower than one in five in Barbados and less the one in ten in Suriname, Venezuela, Dominican Republic and Saint Lucia.

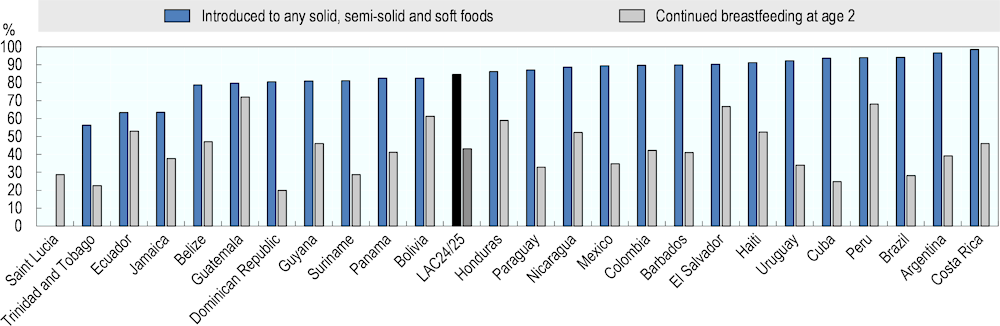

After the first six months of life, an infant needs additional nutritionally adequate and safe complementary foods, while continuing breastfeeding. In 24 LAC countries with data, 84.6% of children receive any solid, semi-solid and soft foods in their diet after the first six months of life, with Jamaica, Ecuador and Trinidad and Tobago below 75%, and Costa Rica, Argentina, Brazil, Peru, Cuba, Uruguay, Haiti and El Salvador above 90%. Moreover, in average, 43% of children in LAC continued breastfeeding until having 2 years old, a rate below 30% in Dominican Republic, Trinidad and Tobago, Cuba, Brazil, Saint Lucia and Suriname, and above 60% in Guatemala, Peru, El Salvador and Bolivia (Figure 4.4).

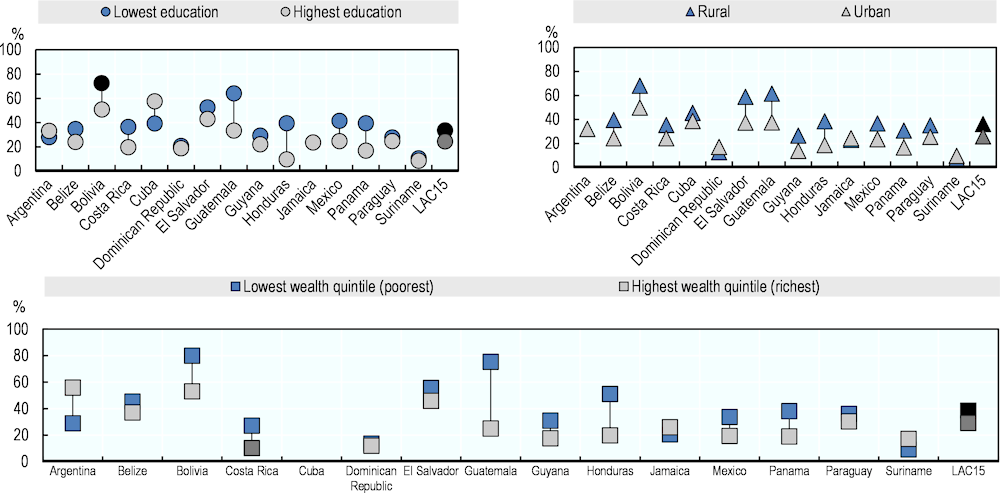

Exclusive breastfeeding is more common in lower and lower-middle income countries rather than higher income in LAC, as well as amongst poorer rural women with lower education than richer women with higher education living in cities (Figure 4.5). However, in countries such as Argentina, Dominican Republic, Jamaica and Suriname, women living in urban areas breastfeed exclusively more than women in rural areas. In Argentina and Jamaica more educated and wealthier women also show higher rates of exclusively breastfeeding, while the same is true for Suriname in the case of wealthier women.

Key factors that can lead to inadequate breastfeeding rates are broad and encompass several dimensions of society. They include unsupportive hospital and healthcare practices and policies, lack of adequate skilled support for breastfeeding, specifically in health facilities and the community, aggressive marketing of breast milk substitutes, inadequate maternity and paternity leave legislation, and unsupportive workplace policies (Rollins et al., 2016[2]).