Recent digitalisation efforts in Kazakhstan have supported development of a widely accessible and affordable internet. However, existing infrastructure limits the digital uptake of firms, as the quality of internet remains below the levels required for business usage, while coverage remains low in some rural and small urban areas. Policy so far has not resolved these issues, and there is insufficient data on firms’ digital use and needs. The regional public sector could play a central role in addressing these gaps by taking a leading role in the monitoring of digital infrastructure rollout and quality, for instance by developing and financing high-speed local networks, and systematically collecting data on business digital use and needs to ground policy-making.

Improving Framework Conditions for the Digital Transformation of Businesses in Kazakhstan

2. Address remaining digital quality and connectivity gaps

Abstract

Challenge 1: The quality of mobile internet has deteriorated recently, while broadband connectivity remains limited in rural and small urban areas

Successive national connectivity plans have resulted in a fairly advanced and affordable network of ICT infrastructure

Since the early 2000s, successive national connectivity plans have succeeded in developing a fairly advanced network of ICT infrastructure providing affordable and quality access to internet in most of Kazakhstan’s urban centres. In terms of access, nearly universal mobile coverage has been in place since 2015 at least, with the population covered by 2G or higher networks reaching 98% in 2019, while access to broadband internet remains more modest (ITU, 2022[1]). Internet access has also become widely affordable across the country, with fixed and mobile subscription costs falling in recent years; they are now well below the UNESCO’s affordability target of 2% of Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. Fixed subscription costs stood at 0.85% of GNI per capita in 2020, compared to a 2.3% average for the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), while mobile subscriptions costs are among the lowest in the world at 0.33% of GNI per capita, compared to 1.0% in CIS countries and 2.6% globally (ITU, 2022[1]; ITU, 2021[2]; Cable, 2022[3]). Improvements have also been made on the quality front, with about three quarters of the population covered by 4G internet in 2021, while the download and upload speeds of broadband lines have doubled on average since 2017 (EIU, 2022[4]). Digital connectivity at large has also progressed in Kazakhstan, with a significant reduction in the rural-urban connectivity gap1, with 89% of the rural and 91% of the urban population having access to broadband networks in 2019 (ITU, 2022[5]).

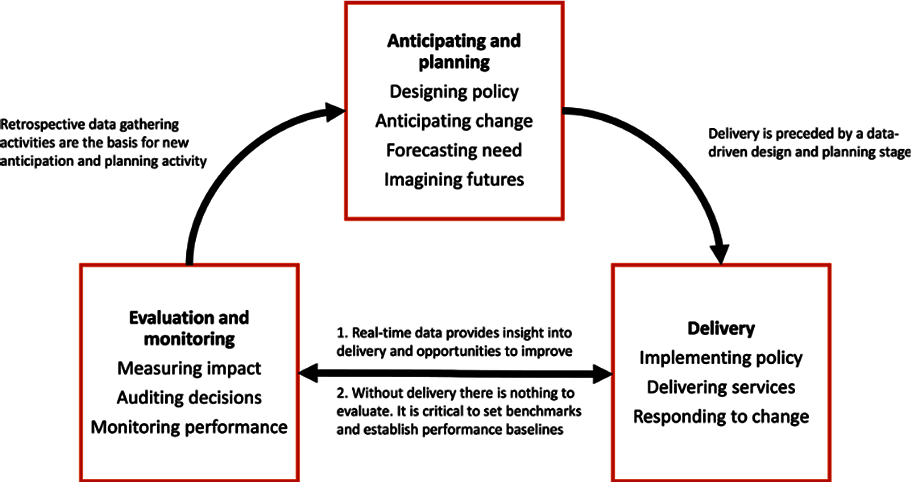

Gaps in terms of network quality and speed mainly affect rural areas

While fixed internet is a key driver for SME digitalisation, broadband uptake in Kazakhstan remains low compared to OECD countries. Broadband subscriptions per 100 households rose only slightly, from 13.1 in 2015 to 13.8 in 2021, compared to 33 on average in high-income countries (ITU, 2022[5]; OECD, n.d.[6]). Though there are no data available on small businesses specifically, only 7.8% of medium and large enterprises reported having access to fixed broadband internet in 2020 (Figure 2.1), while 48% of small business indicated having a website in the latest World Bank Enterprise survey, compared to almost 90% for large businesses (World Bank, 2021[7]). Access to fixed broadband internet varies widely among regions, ranging from 4.3% in Aktobe Region to 15.2% in neighbouring Atyrau. In 2019, the number was even lower (5.9%), with the recent increase being presumably at least partially due to the effects of COVID-19. As a result, only 11% of medium and large enterprises reported using digital technologies in 2020, and while no data is available for SMEs, OECD interviews suggest that the numbers could be even lower for the latter (National Statistics Office, 2022[8]).

This trend might suggest persistent gaps in broadband quality and access. One reason might be a persistent urban-rural network quality divide: while high-quality fixed broadband subscriptions have an average upload and download speed of at least 206.6 Mbps, the remaining 46% of subscribers have access to less than 10 Mbps (EIU, 2022[4]; ITU, 2022[5]). Since existing telecom infrastructure is primarily located along main highways and in densely populated urban areas, high-quality fixed broadband is concentrated in very large urban areas, leaving the rest of the country to work with lower quality internet (UNESCAP, 2020[9]). However, even within large urban centres, OECD interviews indicated that internet speeds can remain below the levels required for business usage (FCC, 2022[10]).

Figure 2.1. Internet use of firms, and quality of available networks

Note: In 2021, fixed broadband average speed stood at 55 for upper-middle income countries, and 113 for high-income countries, while the mobile broadband average speed stood at 25 and 51 respectively.

As a result, OECD interviews confirmed that mobile hotspots and linked mobile devices have become the primary source of internet access for the majority of the population and of small businesses. However, doing so constrains the ability of firms to further advance their digital uptake, as mobile internet is less adapted to the levels of data and digital technology usage associated with business operations (FCC, 2022[10]). In addition, progress in improving mobile network quality has stalled since 2019, with the 2021 mobile up- and down-load speeds slightly deteriorating on average compared to 2019 (Figure 2.1), indicating increasing strain on the mobile sector which could further impede small firms’ digital uptake.

Recommendation 1: Kazakhstan can mobilise the regional public sector to improve quality and coverage of mobile and fixed networks

Despite substantial efforts to build a large network of ICT infrastructure, firms, especially the smallest among them, remain marginal users of internet and digital services. Kazakhstan has started to address these issues, but could do more to bridge the connectivity gap. In particular, the regional and local public sector (e.g. Akimats or Maslikhats at the oblasts or district level) could be mobilised to develop (i) an evaluation process for digital infrastructure needs, rollout and quality, and, where needed, (ii) high-speed “municipal networks”, in co‑operation with other public or private actors.

Bridging connectivity gaps is a matter of access, affordability and quality. If the two former have been addressed rather successfully in Kazakhstan, the quality of connections remains variable and sometimes below the speeds required for business applications. The same is true for mobile internet. The government could develop an integrated evaluation process to assess digital infrastructure rollout and quality. First, this would require defining key performance indicators (KPIs) to set a minimum level of digital coverage and quality. The indicators should be user-needs based, and combine a qualitative and quantitative approach. Once these are defined, and regularly reviewed, data should be collected on a regular basis, from both operators and end-users (households and businesses), and analysed by the competent authorities at the regional and central level to adapt policies where needed (Box 2.1). For instance, the Ministry of Digital Development, Innovation and Aerospace Industry (MDDIAI) and Atameken, the National Chamber of Entrepreneurs, could review, on a quarterly or semi-annual basis, internet quality gaps and related business needs and challenges. Given that rural and small urban areas usually have a unique set of issues associated with their low density and distance to core network facilities, the KPIs could be adapted regionally, requiring close co-operation and co‑ordination between the central, regional, and municipal levels of government.

Box 2.1. Data-driven regulation in the telecom sector to improve network quality and coverage

In 2016, Arcep, France’s communication regulator, initiated data-driven regulation for the sector. Arcep created three map-based websites, "Mon réseau mobile" (My mobile network), "Carte Fibre" (Fibre access maps) and "Ma connexion internet" (my internet connection), complementing the regulator’s traditional toolkit, and providing end-users with up-to-date digital connectivity information.

Information contained in these websites comes from performance tests carried out by Arcep itself, as well as data and feedback provided by local and regional authorities, operators, and businesses.

Arcep has supported the emergence of third-party measuring and testing tools, making its data and “Regulator’s toolkit” available online, with a view to incorporating their findings into the information available on “Mon réseau mobile”. In 2020, four local authorities and the French national rail company had conducted such measurement campaigns.

Assessing coverage gaps across France has therefore become easier, and the large stakeholder engagement created by the initiative, especially at the local level, allows for a quick translation into policy action.

Source: (OECD, 2021[13]; Arcep, 2020[14]).

In Kazakhstan, as in many OECD countries, beyond network quality, a coverage gap persists mostly between urban and small urban and rural areas. Narrowing this gap is critical to strengthening the overall economic development of these regions and the competitiveness of their small firms and entrepreneurs. Since the “last-mile” connectivity initiative has not been successful so far in connecting these regions, their municipal or regional governments, in co‑operation with local interest groups and citizen-led initiatives could facilitate, build, operate or finance high-speed networks, compensating for the absence of operators. Across the OECD area, such municipal networks have been successful in extending connectivity in regions where deployment by national communication companies was lacking or deemed unprofitable; they have contributed to increased competition, and therefore lower prices, in areas where coverage was partially provided by national operators (Mölleryd, 2015[15]) (Box 2.2). However, institutional framework conditions, in particular open competition in the telecom market, have proved an important enabler of such bottom-up initiatives in OECD countries such as Mexico, Sweden, the UK, and the US (OECD, 2021[13]).

Box 2.2. Municipal and community networks in OECD countries

In rural and remote areas, municipal community co-operatives have been formed to build fibre networks in Sweden, Finland, the United States and other OECD countries.

Sweden’s high fibre take-up was enabled by a wide deployment of municipal networks since the liberalisation of the communication market in the mid-1990s, covering entire municipalities, serving homes and businesses and connecting cell towers. Their business model relies on open networks where municipalities act as physical infrastructure providers offering wholesale access to retailers on a non-discriminatory basis. Across the OECD, other models exist, characterised by vertically integrated telecommunication operators present both in wholesale and retail markets.

In Finland, a non-profit municipality-owned fibre network (“Sunet”) connects 55 villages in the rural western part of the country. The network is used by a variety of private-sector service providers to offer connectivity packages to consumers. Sunet has also been successful in lowering the barrier to entry for service providers, thereby supporting competition, by billing consumers directly a fixed fee for the network’s maintenance instead of charging for providers’ access to its infrastructure. It has been financed through a bank loan guaranteed by the local municipalities, coupled with a contribution from the national government.

In the United States, North Dakota, among the country’s most rural and sparsely populated state, had better speed fibre access rates in June 2020 than the current average level in both rural and urban areas nationwide. Key to this success was the Dakota Carrier Network (DCN), a consortium of small, independent rural companies and co-operatives that purchased the rural exchanges of the incumbent telephone company in the late 1990s to form a state-wide umbrella organisation that covers 90% of the state’s land area and 85% of its population. The development of its fibre network has been funded by the federal state through the Broadband Technology Opportunities Programme (BTOP).

Similar networks have also been deployed in the United Kingdom (Broadband for the Rural North) and Mexico, and rely mainly on a mix of streamlined regulatory approvals at the local level (which reduces costs), voluntary work contributed by local residents, and funding support from the government.

Source: (OECD, 2021[13]).

Challenge 2: Lack of data on business use of internet and related needs limits the development of policies to support firms’ take-up of digital technologies

Kazakhstan has developed data-driven policies to improve network quality and coverage

Over recent years, Kazakhstan has increasingly turned towards data-driven policies, especially to improve the quality and coverage of digital infrastructure networks. For instance, under the NDS, citizen-reporting platforms have been created as a monitoring tool for minimum internet speed requirements imposed on operators in remote rural and small urban areas (Government of Kazakhstan, 2017[16]). The online platform gathers complaints about internet quality and is linked to the Interdepartmental Commission on Radio Frequencies and local state telecom authorities. It verifies connection quality and fines telecom operators immediately should quality fall below the minimum threshold.2 OECD interviews indicate that the system has enabled the improvement of internet connection quality, especially in Kazakhstan’s border areas, which face the lowest quality. OECD interviews further find that the MIID also developed monthly public-private dialogue (PPD) with the Council of Operators since 2020, where the owners of main telecommunication infrastructure and towers and large business associations discuss infrastructure bottlenecks and challenges. However, neither regional governments nor small last-mile operators are part of such meetings, which limits their effectiveness in gathering the relevant actors – national and local operators, regional authorities, and the private sector – to address often highly localised issues.

In addition, one of the main objectives of the current NDS, DigitEL, is the development of data-driven government by 2025. The “attentive and effective state” initiative aims at creating a unified data collection process to ground policy decisions, including the development of user feedback for public services, and more importantly the automatic collection and treatment of data relevant for policy-making. However, in its current state, the initiative only targets industrial data to be monitored by the public revenue committee (Government of Kazakhstan, 2021[17]). If proven effective, the initiative could be expanded in the coming years to new sectors, where it could thereby serve as an important tool for gathering data about the digital needs and use of businesses.

More systematic and comprehensive data collection about business needs and challenges could help improve provision of digital connectivity and usage

Kazakhstan’s digital strategies have succeeded in creating a wide and effective network of e-government services and the conditions for developing data-driven government. However, during the interviews conducted by the OECD, the lack of systematic and comprehensive data collection about the needs and challenges of businesses in relation to their digital uptake, beginning with access to quality and affordable ICT infrastructure, was repeatedly mentioned.

Atameken and other business associations gather some qualitative data on business digital needs and challenges, but Kazakhstan has no systematic and comprehensive data collection on firms’ access to and use of the internet. The Statistical Office collects some data on internet use of medium and large-sized industrial enterprises, without collecting information on businesses active in other sectors or from SMEs. Digital indicators are mainly collected for individuals, leaving aside important information such as business subscriptions to mobile and fixed internet (National Statistics Office, 2022[8]). Similarly, the digital one-stop-shop (OSS) “Government for Business” launched early this year aims at creating a direct interaction channel between the government and SMEs (Government of Kazakhstan, 2021[17]). The portal provides entrepreneurs with access to public services and support measures of government entities, such as Atameken or DAMU, and access to digital commercial systems, though it does not provide an opportunity for businesses to report and seek advice on the barriers or challenges they might face in their digital transformation.

In addition, beyond the monthly gatherings between the MIID and large operators on infrastructure challenges mentioned above, no public-private dialogue mechanisms exist involving all stakeholders in the digital infrastructure sphere. Consequently, a gaps assessment at the regional or national level is missing. Where it does exist, it is ad hoc and generally through the lens of operators. This represents a significant limitation on efforts to foster the digital uptake of firms, as on the demand side businesses lack an important channel to discuss and report issues to business associations and local and central governments, while the public sector has a hard time analysing precise evolutions and determining best policy actions to support firms in their digital journey.

Recommendation 2: Improve data collection on firms’ digital usage and needs and develop data-driven support policies on that basis

In order to address the remaining digital quality and connectivity gaps, Kazakhstan could (i) regularly and systematically collect data on firms’ use of digital infrastructure and services and the barriers they face; (ii) develop regular public-private dialogue (PPD) mechanisms at national and regional level to discuss the state of digital infrastructure; and (iii) generalise the use of data-driven public sector approaches to support the digital transformation of firms.

Accurate data are essential to effective policy-making. National statistical offices (NSOs) in OECD and partner countries regularly collect (on a quarterly and annual basis) data pertaining to the basic access to and use of internet and digital tools by businesses, including as access to the internet, mobile and broadband subscriptions, and use of digital tools. In addition, they provide detailed data by firm size, sector of activity and location, allowing for the detection of connectivity and digital uptake gaps between small, medium and large enterprises. Kazakhstan’s NSO could develop similar systematic data collection, to supplement its data on digital and SME topics. Atameken or other business associations could also build on their existing networks to conduct regular surveys of firms, especially SMEs, to gather qualitative data on their use of digital infrastructure and services as well as their experience and the barriers they face in doing so. The introduction of regular PPD mechanisms, at both national and regional levels, would complement such an approach, by offering a regular platform for exchange between central, regional, and municipal authorities, large operators on the supply side, and end-user private sector representatives on the demand-side. For instance, Atameken could head such an initiative and liaise with the Akimats or Maslikhats at the oblasts or district level, the MDDIAI, and the Association of National Telecom Operators. Such a systematic dialogue mechanism would ensure the government is up to date on the needs of the private sector and can adapt its policies accordingly.

Once developed, comprehensive data collection on business use and needs in relation to the digital transformation could inform policy-making and monitoring to support infrastructure rollout and the digital transformation of firms. Kazakhstan could expand the data-driven public sector strategy laid out in the DigitEl programme to telecom infrastructure, while defining a data governance model fitting the specific needs of both the sector and of small firms (Government of Kazakhstan, 2021[17]).

Box 2.3. Collecting firm-level data to inform policy on business digital services and infrastructure

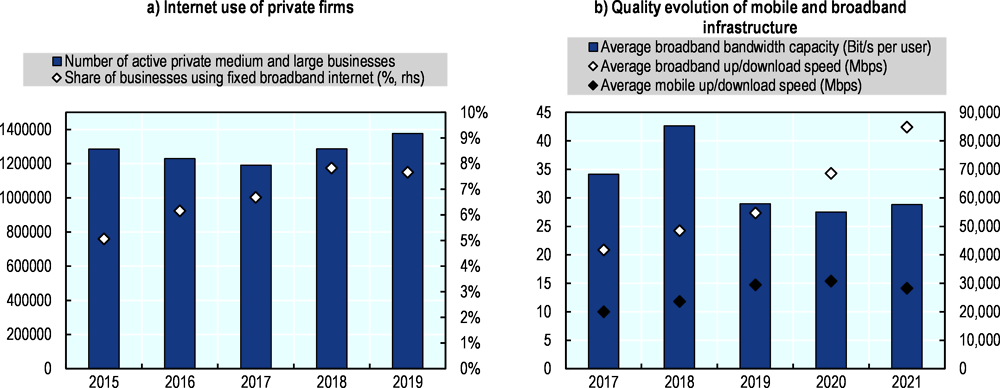

Applying data to generate public value

For data to support effective policy-making, OECD research indicates the importance of a sound governance structure, built on an iterative three-step cycle: (i) anticipatory governance, (ii) design and delivery, and (iii) performance management:

The anticipation and planning phase requires understanding the type of data needed and how they can be used in policy design. This phase is therefore an opportunity to anticipate changes and needs for both data and policy. Data sources cover both new qualitative and quantitative data, and data generated through the evaluation of previous policies.

The delivery phase consists in the implementation of analytical tools and the definition of effective performance measurements to be able to read the collected data and apply any resulting insights to amend policies and activities where needed.

The final phase is evaluation and monitoring to measure the impact and performance of policies, based on insights from data generated through the “delivery” phase.

Figure 2.2. Generate public value through data-driven public sector approaches

References

[14] Arcep (2020), Data-Driven Regulation: Arcep looks back at five years of “data-driven regulation”, https://en.arcep.fr/news/press-releases/view/n/data-driven-regulation-081220.html (accessed on 20 June 2022).

[12] Bureau of National Statistics (2022), Small and Medium Enterprises (database), https://stat.gov.kz/official/industry/139/statistic/6 (accessed on 29 April 2022).

[3] Cable (2022), Worldwide mobile data pricing 2021, https://www.cable.co.uk/mobiles/worldwide-data-pricing/ (accessed on 28 April 2022).

[11] DAMU (2020), Annual Report on SMEs Development in Kazakhstan and its regions, https://damu.kz/upload/iblock/192/Damu_Book_2019_EN.pdf.

[4] EIU (2022), The Inclusive Internet Index (database), https://theinclusiveinternet.eiu.com/ (accessed on 21 April 2022).

[10] FCC (2022), Broadband Speed Guide, https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/broadband-speed-guide (accessed on 28 April 2022).

[17] Government of Kazakhstan (2021), Digital Era Lifestyle Programme.

[16] Government of Kazakhstan (2017), State programme “Digital Kazakhstan:, https://digitalkz.kz/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/%D0%93%D0%9F%20%D0%A6%D0%9A%20%D0%BD%D0%B0%20%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B3%D0%BB%2003,06,2020.pdf.

[1] ITU (2022), Digital Development (database), http://itu.int (accessed on 27 April 2022).

[5] ITU (2022), World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database online, https://www.itu.int/pub/D-IND-WTID.OL-2021/fr (accessed on 29 April 2022).

[2] ITU (2021), The affordability of ICT services 2020, https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/publications/prices2020/ITU_A4AI_Price_Briefing_2020.pdf.

[15] Mölleryd, B. (2015), “Development of High-speed Networks and the Role of Municipal Networks”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 26, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrqdl7rvns3-en.

[8] National Statistics Office (2022), Share of large and medium-sized industrial enterprises using digital technologies (database), https://stat.gov.kz/api/getFile/?docId=ESTAT410029 (accessed on 3 May 2022).

[13] OECD (2021), Bridging digital divides in G20 countries, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/35c1d850-en.

[18] OECD (2019), The Path to Becoming a Data-Driven Public Sector, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/059814a7-en.

[6] OECD (n.d.), OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/20780990.

[9] UNESCAP (2020), In-depth national study on ICT infrastructure co-deployment with road transport and energy infrastrutcure in Kazakhstan, https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/In%20depth%20national%20study%20on%20ICT%20infrastructure%20co-deployment%20with%20road%20transport%20and%20electricity%20infrastructure%20in%20Kazakhstan%2C%20ESCAP.pdf.

[7] World Bank (2021), World Bank Enterprise Survey.

Notes

← 1. The term “connectivity gap” refers to gaps in access and uptake of high-quality broadband services at affordable prices in areas with low population densities and for disadvantaged groups compared to the population as a whole (OECD, 2021[13]).

← 2. At the time of writing, a new draft law is under consideration to increase the liabilities of the operators in case of low or deteriorating network quality.