Public finances alone are not enough to meet transition needs. Aligning investment and financial markets and getting private sector buy-in is critical but current commitments too often lack credibility. This chapter looks at how government policies can harness and redirect key public and private finance flows including by strengthening financial market practices through focusing on environmental, social and governance (ESG) rating and investment approaches, and strengthening metrics used to track financial sector progress can better support finance flows aligned with the transition. Finally, the chapter addresses the role of the private sector in ensuring the resilience of net-zero commitments and their transition pathways.

Net Zero+

9. Aligning finance flows and private sector action with a resilient net‑zero transition

Abstract

This chapter draws on contributions to the horizontal project carried out under the responsibility of the Investment Committee including the Working Party for Responsible Business Conduct and the Environment Policy Committee.

Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement calls for “making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and climate-resilient development” (UNFCCC, 2016[1]). It recognises the critical role of finance in enabling large-scale emissions reductions and adaptation to climate impacts. Tracking financial sector progress in aligning finance flows with these objectives and addressing opportunities to further scale aligned finance is key to ensuring the immediate and longer-term resilience of the net-zero transition.

Although financial markets are beginning to integrate climate transition risks and opportunities into investment decision making, constraints remain to the efficient and scaled mobilisation of finance into net‑zero aligned activities. This chapter looks at how strengthening market practices by focusing on environmental, social and governance (ESG) rating and investment approaches, and strengthening metrics used to track financial sector progress, can better support scaled and aligned climate finance flows in accelerating the transition.

In addition, this chapter focuses on how government policies can harness and redirect key public and private finance flows in such a way that they do not increase the vulnerability or fragility of systems or undermine net-zero goals but, rather, accelerate a resilient net-zero transition. Two important examples are used to exemplify how and where these policy actions can take hold. First, an examination of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and specific recommendations of the OECD FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit.1 Second, an examination of how investment treaties promote long-term lock-in of emissions-intensive investment, potentially disincentivising governments’ implementation of ambitious climate policy.

Lastly, this chapter addresses the role of the private sector in ensuring the resilience of net-zero commitments and their transition pathways. First, by ensuring commitments are being implemented with integrity, avoiding greenwashing (United Nations, 2022[2]) and safeguarding against adverse impacts across other areas of business operations or responsibilities. Second, by strengthening the resilience of global supply chains critical for the net-zero transition.

Measuring climate alignment of finance flows through real-economy investments

Climate “alignment”, or the consistency of finance with climate policy goals, entails scaling up finance for activities aligned with the Paris Agreement. This includes financing activities and economic sectors transitioning towards low greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions while also building resilience to the impacts of climate change. This can be done through market practices that enable the reallocation of capital towards greener alternatives; discourage capital flows to GHG-intensive projects; and embed environmental integrity to ensure the resilience of these efforts.

The climate alignment of financial stocks and flows can be measured by looking at the subsequent alignment of real-economy investments and activities. OECD analysis shows that very low volumes of real-economy investment are, in fact, aligned with climate mitigation objectives (Box 9.1). Moreover, climate-alignment assessments of financial assets based on a number of different methodologies have all found a high degree of misalignment of financial stock with the Paris Agreement temperature goal (Noels and Jachnik, 2022[3])

Despite these initial results, tracking progress on alignment with the level of detail needed to effectively assess the impact of decarbonisation incentives remains difficult. This is due to the lack of granular climate performance data and reference points, comparable and transparent methodologies, and credible metrics (OECD, 2021[4]). Moreover, the inconsistencies and gaps in the methodologies used to assess the climate alignment of finance can allow for greenwashing and threaten the environmental integrity of efforts to channel finance into climate-aligned activities. For example, a partial coverage of asset classes could result in decisions to move emissions-intensive assets from listed to unlisted companies where the latter are currently less scrutinised by climate-alignment assessment methodologies. These circumstances could result in, on aggregate, emissions not being reduced though disclosure is improved (Noels and Jachnik, 2022[3]).

Box 9.1. Measuring the alignment of real-economy investments with climate mitigation policy goals

Initial assessments of the alignment of real-economy investments with climate mitigation policy goals conducted by the OECD demonstrated that investments can only be considered aligned with climate mitigation policy objectives in very limited cases.

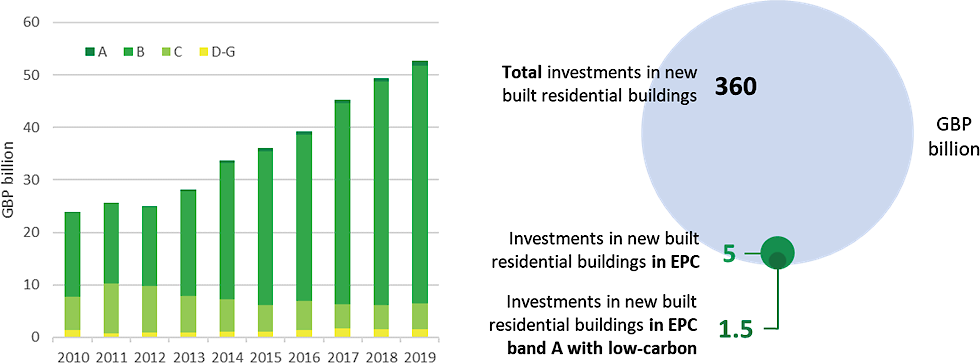

Between 2019 and 2021, the OECD Research Collaborative on Tracking Finance for Climate Action conducted three country-sector pilot studies, covering the building sector in the United Kingdom (Jachnik and Dobrinevski, 2021[5]), the transport sector in Latvia (Dobrinevski and Jachnik, 2020[6]), and the manufacturing sector in Norway (Dobrinevski and Jachnik, 2020[7]). The results indicated that in all cases only very limited volumes of investments could be considered as aligned. For example, the results of the United Kingdom building sector pilot study showed that less than 1% of new construction investments between 2010 and 2019 could be considered consistent with net-zero objectives (Jachnik and Dobrinevski, 2021[5]).

The outcomes of the pilot assessments were significantly influenced by the availability of comprehensive and/or granular data on investments, financing, GHG emissions, and the level of detail required by alignment reference points used. While emissions and decarbonisation efforts are best analysed at the financial asset level, reference points (including climate mitigation scenarios) are typically provided at a higher level of aggregation (e.g. at the sector or country level).

Moreover, the studies revealed challenges in exposing the direct links between real-economy investments, and financing sources and financial intermediaries. While real-economy investments can be traced more closely than financial stocks to climate objectives, decisions relating to capital allocation in the financial system – as directed by market practices including ESG ratings and related investment approaches – strongly influence real-economy progress on climate action.

Figure 9.1. Investments in newly built residential buildings, by Energy Performance Certificate band, 2010-2019 (GBP billions)

Strengthening financial market practices

Financial institutions committing to net zero is becoming mainstream, whether they are asset owners or multinational banks, including under the umbrella of coalitions.2 A number of initiatives set out guidance on metrics and information to be reported by investors and financial institutions in relation to their low-emissions transition and net-zero strategies. These include, among others, the Financial Stability Board (FSB)-affiliated Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) to establish disclosure guidance; and the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) to create reporting standards.

Yet, investment decisions are still hampered by different uncertainties, notably relating to national climate policies (e.g. support schemes, carbon pricing) and new or unproven technologies which will increasingly be relied upon to further reduce GHG emissions. Additionally, in practice, many net-zero initiatives take the form of coalitions or frameworks, which, while putting forward overall guidance, do not provide a concrete methodological approach for tracking progress (Noels and Jachnik, 2022[3]). Even among initiatives providing tracking methodologies, there is significant variation in alignment assessment results due to differences in perspectives (and a lack of consensus on a range of methodological dimensions). For example, some methodology providers find absolute emissions metrics to be more relevant whereas others prefer an “economic intensity contraction” approach (where GHG emissions are divided by economic output) as it is more closely linked to decoupling. This means the same financial asset could be deemed climate-aligned by some assessments but not by others (Noels and Jachnik, 2022[3]).

There is also evidence that financial market participants hesitate to provide transition financing for companies on the basis of insufficient clarity on how to assess credible corporate alignment with a pathway in line with the Paris Agreement temperature goal (OECD, 2022[8]). This highlights the need to continue to further develop indicators, metrics, and methodologies to assess climate alignment of assets to better inform financial market participants and policy (Noels and Jachnik, 2022[3]). These challenges are further addressed below in the context of ESG investing.

Within industries, some GHG-intensive firms that are acknowledging stranded assets and making progress on their transition plans are showing an improved enterprise value (OECD, 2021[4]; OECD, 2021[9]). This firm-level progress is vital for financial institutions whose own net-zero targets will rely on GHG reductions by their borrowers or portfolio assets. Fully capturing such real-economy progress and managing portfolio risks in assessments of climate alignment will require comprehensive coverage of financial assets and asset classes as well as further approaches at the portfolio level (Noels and Jachnik, 2022[3]).

Alignment of ESG rating and investing approaches with the net-zero transition

ESG investing refers to the process of incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into asset allocation and risk decisions so as to generate sustainable, long-term financial returns. ESG investing has become a leading form of sustainable finance due to its perceived potential to deliver financial returns, align with societal values, and contribute to sustainability, including climate-related objectives.

Driven by market participants showing greater awareness of the impacts of physical and climate-transition risks on financial stability and market efficiency, ESG rating providers and investment funds are increasingly integrating metrics aligned with environmental impact, climate risk mitigation, and strategies to scale use of renewable energy and climate-related innovation. In this way, ESG rating and investing approaches can help to align finance flows with net-zero objectives and accelerate the transition. They could also strengthen the resilience of the transition itself by ensuring that finance flows are evaluated not only with respect to climate, but also with respect to their interlinked governance and social implications. This will be important where adverse outcomes related to corporate governance, people and communities could undermine progress made on climate.

There has been important progress in developing ESG rating and investing approaches, particularly with respect to the environmental pillar (Box 9.2). However, to better harness these methodologies as tools to accelerate net-zero transitions, it will be important that they focus less on rewarding disclosure practices and more on rewarding alignment of issuer activities with climate objectives. This will provide markets with the information needed to better align their investments with ESG criteria and thereby climate objectives.

Box 9.2. The environmental pillar of ESG progress and opportunities for reform

ESG rating providers appear to give greater weight to the existence of climate-related corporate policies, targets and objectives than actual climate metrics, namely a corporation’s reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and emissions intensity over time and increased investment in climate mitigation, adaptation and renewable energy.

OECD analysis finds that high environmental pillar scores do not always mean that a firm has reduced its greenhouse gas emissions and emissions intensity over time or increased use of and investment in renewable energy. Rather, it is the firm’s disclosure of climate risks and opportunities that is prioritised. This makes the environmental pillar a less useful tool for assessing or indicating a company’s current level of short-term reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and emissions intensity, and investment in environmental R&D and renewable energy.

While the E pillar of ESG ratings can be an important tool to ensure capital is allocated to investments that support an accelerated transition to net zero, to fully realise this potential the above shortcomings need to be addressed by both government policies and good practices.

Further, in harnessing the role of ESG investing in a resilient transition, reform efforts need to take into account ESG investing in emerging markets and developing economies, and not just the developed world. This is critical as carbon emissions in developing countries have not yet peaked (see Chapter 5) and these economies will need significant and increasing financing to reduce emissions and adapt to climate impacts.

However, emerging economies can often be at a disadvantage due to lower ESG scores and low investment allocations from ESG funds, as highlighted by a recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) study (IMF, 2022[12]). Addressing issues of higher cost of capital; strengthening enabling environments for investments; supporting the development and deepening of financial systems; and carrying out risk-based due diligence aligned with OECD recommendations can support the financial sector and businesses in responsibly engaging in developing countries and higher-risk sectors and supply chains.

Metrics to support tracking financial sector progress against net-zero commitments

To ensure that market practices (including ESG investing) and related climate policies encourage climate-aligned finance flows, it is necessary to track the progress financial institutions and investors towards their net-zero commitments. One of the main obstacles to this is the current lack of comparable and quality metrics.

For example, interim emissions reductions targets (e.g. for 2030) are often set at disparate target years and values in contradiction with emerging good practices (such as using harmonised interim target years or science-backed scenarios). In addition, as interim targets are not required to be set along linear trajectories from the base year to the target year, they can range widely across financial institutions in terms of their level of ambition. This raises obvious questions about how such targets are established and precisely what “progress” means across various non-linear pathways, creating a number of uncertainties. For example, is a financial institution that is advancing in a linear manner toward a modest interim target making more or less progress than a peer that is falling short of a much more ambitious interim target, particularly if the latter has achieved greater reduction of gross emissions during this period? How does one evaluate the ambition and credibility of a target based on known technologies such as the production of electric cars versus unproven or nascent innovations such as hydrogen fuel? To what extent does a pathway depend on GHG emissions reductions versus carbon offsets (and do such offsets align with environmental integrity)? Indeed, corporate-related financial assets are more often found to be misaligned with climate goals when assessment methodologies explicitly exclude the use of offsets (Noels and Jachnik, 2022[3]).

Clarity on these dimensions is important in ensuring consistency and comparability across measurements and the assessment of progress towards commitments. A range of complementary metrics will be needed to provide a more nuanced and comprehensive view of the contribution of finance to reaching climate policy goals (Noels and Jachnik, 2022[3]). Aside from GHG performance metrics, non-GHG-based metrics relating to production plans, capital expenditure and technology-based metrics can usefully inform progress towards climate policy goals. Such metrics should cover different temporal perspectives (backward-looking, current and forward-looking). Moreover, more methodological developments for financial asset classes other than corporate equity (i.e. real estate and sovereign bonds) are needed to cover all portfolio segments of financial institutions (Noels and Jachnik, 2022[3]).

Achieving progress in the short-, medium- (through interim targets) and long-term (net-zero targets) suggests that financial intermediaries need to make fundamental changes to their portfolios and lending policies, and strategic and operational changes to incorporate climate transition at many levels within organisations. To this end, the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group’s 2022 Sustainable Finance Report includes a recommendation that governments and international organisations and networks could consider measures to enhance the accountability and comparability of financial sector net-zero commitments in a manner consistent with their mandates and objectives (G20 SFWG, 2022[13]).

Progress on harnessing key finance flows

Drawing on two specific examples, this section focuses on: (i) harnessing Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and specific recommendations of the OECD FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit; and (ii) the operation of investment treaties as an important part of the public policy framework governing finance flows. Both FDI and the finance flows associated with investment treaties represent substantial shifts in capital that need to be increasingly directed towards a resilient net-zero transition.

Accelerating the transition to net zero through foreign direct investment

FDI can play a critical role in promoting sustainable development. For the host country, it can support growth and innovation, generate quality jobs, raise living standards and improve environmental sustainability. It can accelerate the net-zero transition through: (i) direct investment in technologies, services and infrastructure; and (ii) “FDI spillovers” or the added positive impact of FDI by multinational enterprises with access to innovative low-carbon technologies and operating procedures that could boost environmental performance.

FDI can contribute to environmental and climate objectives, particularly when coming from jurisdictions with more stringent environmental regulation – FDI accounted for 30% of global new investments in renewable energy in 2020. However, foreign investors can also worsen environmental outcomes; for example, by offshoring highly polluting activities to countries with less stringent regulations or inducing a race to the bottom with respect to environmental standards as countries compete to attract FDI. The latter, in particular, can inhibit the resilience of the net-zero transition.

Uncertainty and unpredictability are barriers to green or climate-aligned FDI. Green investors, like all investors, seek a stable, predictable, and transparent investment environment in which to identify bankable projects. Efforts to mobilise green investment to support an accelerated and resilient net-zero transition will fail to meet these criteria unless governments ensure a regulatory environment that provides investors with fair treatment and confidence in the rule of law, notwithstanding disruptions or shocks.

The OECD FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit (OECD, 2022[14]) outlines specific enabling conditions and policies to attract investment contributing to reducing GHG emissions, and relating to (i) governance, (ii) regulation, and (iii) targeted support measures.

Governance

Setting a clear, long-term net-zero transition trajectory linked to the national vision for growth and development is critical. This allows investors to understand transition risks and attracts foreign investment that contributes to the country’s climate agenda. Transparency and predictability, which are critical for investment decisions in general, matter even more when considering returns on investments with long time horizons.

A strategic framework for addressing climate change should integrate climate objectives across sector strategies and plans; translate national-level emissions targets into science-based targets at the sector level; include key performance indicators to measure outputs and outcomes and establish procedures to collaborate effectively with other relevant public agencies and stakeholders – including the private sector. Clearly delineating the role of private investors, both domestic and foreign, in achieving climate objectives can help tailor investment promotion efforts to target investors.

Measuring and tracking the impact of FDI on carbon emissions, and its potential contribution to decarbonisation can also help identify appropriate policy responses. Collection and production of timely and internationally comparable data on FDI by sector is important for monitoring its contribution to decarbonisation.

Regulation

The OECD Policy Framework for Investment (PFI) (OECD, 2015[15]) and its chapter on Green Growth provide insights on global good practices for creating a regulatory framework conducive to green investment; reiterating the governance recommendations referred to above. More specifically, the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index suggests that some sectors critical to decarbonisation efforts remain partly off-limits to foreign investors in many countries – notably, transport, electricity generation and distribution, and construction. Removing discriminatory restrictions on FDI in these sectors would open up opportunities for climate-aligned FDI and associated spillovers such as knowledge transfer and technology deployment. Services typically associated with lower carbon emissions and in some cases those that are crucial for energy-saving technologies (e.g. digital services) are also often restricted from foreign participation. This stops FDI from contributing to the net-zero transition.

Regulatory reform to address this, as well as environmental regulations and standards that reinforce climate goals more broadly, can help level the playing field for foreign investments in climate-friendly technologies, services and infrastructure. Countries should regularly assess whether their technology and performance standards are in line with long-term climate goals.

Targeted support measures

Policies conducive to FDI will not automatically result in a substantial increase in green or climate-aligned FDI. In addition to general climate policies that internalise the cost of emissions, targeted financial and technical support, and information sharing can help address market failures that reduce the competitiveness of climate-aligned investments.

In particular, investment promotion agencies (IPAs) are key players in bridging information gaps that may otherwise hinder the realisation of foreign investments and their potential sustainable development impacts. The primary role of IPAs is to create awareness of existing investment opportunities, attract investors, and facilitate their establishment and expansion in the economy, including by linking them to potential local partners. Most IPAs prioritise certain types of investments over others. The prioritisation approaches and tools adopted by IPAs should reflect the national investment promotion strategy and the climate considerations embedded therein. Since few economies can offer an attractive environment for all low-carbon technologies and all segments of their value chains, IPAs should review and identify specific economic activities where they see potential to develop and scale low-carbon activities. They should also design targeted investment promotion packages combining a variety of tools that range from intelligence gathering (e.g. market studies) and sector-specific events (inward and outward missions) to proactive investor engagement (one-to-one meetings, email/phone campaigns, enquiry handling).

Achieving a role for investment treaties in climate-aligned finance

Investment treaties are an important part of the public policy framework governing finance flows but remain largely unregulated when it comes to alignment with climate objectives, specifically Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement (Novik and Gaukrodger, 2022[16]). In its April 2022 report, Working Group III of the IPCC expressed concern that much of international governance still promotes fossil fuels and highlighted the role of investment treaties and investor-state dispute settlement.

Investment treaties (including investment chapters and provisions in trade agreements as well as stand-alone investment treaties) are entered into by governments to protect and encourage foreign investment. They provide treaty-covered investors with protection from financially adverse impacts of government action (i.e. policy action that may financially injure projects funded by an investor) in host countries. Government actions that are covered include policy action that could result in discrimination, uncompensated expropriation of property, a failure to provide “fair and equitable treatment”, or limitations on rights to transfer capital. In this way, investment treaties can de-risk foreign investment, acting as a form of political risk insurance, and in instances where compensation claims can be made via investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) – a process of ad-hoc international arbitration.

In the context of the transition to net zero, policy efforts to curb demand and limit supply of fossil fuels will have financial impacts on investors, likely impacting fossil fuel projects funded by foreign investment and covered by an investment treaty. In such a scenario, i.e. where a government revokes licenses or permits to restrict the development of fossil fuels in its territory or detrimentally affects fossil fuel projects funded by a treaty-protected foreign investor, foreign investors can claim against the government in ISDS for damages, including loss of profits.

While there have been few government policies creating stranded fossil fuel assets to date, some of the first non-discriminatory OECD government policies directed at gradual exits from coal have generated major claims in ISDS (Braun, 2021[17]) or agreements to pay billions of Euros, reportedly, in exchange for release from ISDS claims (Reuters, 2020[18]). This is an important consideration when looking to bolster the resilience of the global net-zero transition. The implementation of net-zero commitments by governments may be deterred by the threat of ISDS litigation or awards, with the issuing of such awards potentially diverting crucial public finance flows from climate mitigation, particularly in the global south.

Investor-state dispute settlements have the highest average claim for payment and highest average number of binding awards requiring payment of any legal system in the world (Gaukrodger, 2022[19]). Between June 2017 and May 2020, the mean amount claimed in ISDS cases was USD 1.1 billion. The mean amount awarded to a successful claimant has recently risen since from June 2017 by more than 184% to USD 315.5 million (Hodgson, Kryvoi and Hrcka, 2021[20]).

Fossil fuel coverage and claims are often at issue. As of May 2022, at least 231 ISDS cases were a result of investments in fossil fuels – constituting close to 20% of the total known number of cases (Tienhaara et al., 2022[21]). Seven of the ten largest ISDS damages awards against governments under investment treaties have involved fossil fuel investor claimants, each for over USD 1 billion and all in the last 15 years (UNCTAD, 2022[22]). Law firms are advising investors who are likely to be adversely affected financially by government action pursuant to their climate-change commitments, such as the phase-down of coal and other fossil fuels, to engage in corporate structuring to maximise access to ISDS.

There is limited evidence of governments considering the alignment of their investment treaties with the Paris Agreement or global climate-accountability mechanisms such as the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). Given widespread government commitments to net zero, and, in particular, to ending support for coal and all fossil fuels abroad, it is important that they prioritise such alignments. This should include analysing the substantial finance flows associated with fossil fuels that are currently supported by investment treaties, particularly in light of the insurance-like characteristics of the support provided to treaty-covered investment.

There is growing recognition of investor-state dispute settlements as potential deterrents to ambitious government policy on climate change and the need to rethink investment treaty policies and frameworks. Strong public-private collaboration on a range of conceptual and operational issues will be important for such change. Well-designed investment treaties can contribute to climate-aligned finance and investment, prevent fossil fuel lock-in, drive action towards net-zero emissions and better support the resilience of the transition.

Private sector-led action towards resilience and integrity

Businesses play a key role in scaling climate ambition and implementing net-zero transition, channelling policy commitments and related finance and investment into aligned activities across the real economy. Net-zero commitments are growing among companies and financial institutions. More than one-third of the world’s largest publicly traded companies have set net-zero targets (Science Based Targets, 2021[23]; Net-Zero Tracker, 2022[24]).

The private sector also has an important role in ensuring the resilience of these commitments and their transition pathways. First, by ensuring commitments are being implemented with integrity without greenwashing (United Nations, 2022[2]) and safeguarding against adverse impacts across other areas of businesses’ operations or responsibilities. Second, by strengthening the resilience of global supply chains that are critical for the net-zero transition. In examining how businesses can drive progress in these areas, this section draws on the OECD responsible business conduct (RBC) framework to support these efforts.

Implementing net-zero commitments with integrity

The proliferation of sustainability standards over the past 30 years has created a crowded and sometimes confusing landscape for business and policy makers alike. A broad range of net-zero guides, coalitions, frameworks, methodologies, benchmarks and standards have emerged to support the private sector in setting GHG emissions-reduction targets; measuring, cutting and disclosing their GHG emissions; and aligning their activities with net-zero transition pathways. While this has led to an increase in net-zero pledges, there has been growing concern about their credibility.

Preliminary OECD analysis and external assessments, notably the recent report of the UN High Level Expert Group on the Net-Zero Emissions Commitments of Non-State Entities (UN HLEG) (United Nations, 2022[2]), reveal considerable variation in how voluntary private sector climate commitments materialise in practice. They also raise concerns about the quality of commitments with regard to the credibility and transparency of their methodological approaches.

This has led to significant concerns over greenwashing, with businesses committing to net zero while simultaneously investing in fossil fuels; engaging in environmentally destructive activities such as deforestation; purchasing questionable carbon credits rather than reducing emissions throughout their value chains; and lobbying in such a way that goes against climate objectives. The UN HLEG report identifies the lack of a level playing field as an important underlying barrier to implementing net zero with credibility (United Nations, 2022[2]).

In addressing these challenges, lessons can be drawn from the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) on Responsible Business Conduct (RBC) and the OECD Due Diligence Guidance (together forming the “RBC Framework”) on supporting a resilient net-zero transition through the credible implementation of net-zero commitments by businesses (Box 9.3).

Box 9.3. The OECD Responsible Business Conduct Framework

RBC sets out an expectation that all businesses – regardless of their legal status, size, ownership or sector – avoid and address negative impacts of their operations while contributing to sustainable development in the countries where they operate. This expectation is enshrined in the OECD Guidelines for MNEs and related OECD due diligence guidance.

OECD Guidelines for MNEs

The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (the “MNE Guidelines”) consist of government-backed recommendations to multinational enterprises (“MNEs”) operating in or from Adhering countries. The MNE Guidelines are currently the only authoritative, government-backed instrument on RBC operating at the international level. The recommendations cover all areas of business responsibility: disclosure, human rights, employment and industrial relations, consumer interests, bribery and corruption, science and technology, competition, taxation and the environment. The MNE Guidelines include the expectation that businesses carry out risk-based due diligence to identify, prevent and mitigate actual and potential adverse impacts related to each of these areas and account for how these impacts are addressed.

A number of provisions across different Chapters of the Guidelines intersect with climate mitigation and adaptation considerations for business. For example, and in the context of mitigation specifically, the Environment Chapter provides that enterprises should have an environmental management system in place, which includes establishing “measurable objectives and, where appropriate, targets for improved environmental performance and resource utilisation”. This expectation also includes periodically reviewing the continuing relevance of these objectives and that where appropriate, “targets should be consistent with relevant national policies and international environmental commitments”.

The Environment Chapter also provides that businesses should “continually seek to improve corporate environmental performance at the level of the enterprise and, where appropriate, of its supply chain” and references a number of activities including: the “development and provision of products or services that […] reduce greenhouse gas emissions”; “promoting higher levels of awareness among customers of the environmental implications of using the products and services of the enterprise, including, by providing accurate information on their products (for example, on greenhouse gas emissions […]”; and “exploring and assessing ways of improving the environmental performance of the enterprise over the longer term; for instance, by developing strategies for emission reduction”.

Importantly, a number of the expectations related to climate-change responsibilities extend beyond the Environment Chapter and are embedded in chapters on General Policies, Disclosure, Science and Technology, Human Rights, Competition and Consumer Interests.

Targeted update to the MNE Guidelines

The Working Party on Responsible Business Conduct is considering options to ensure that the MNE Guidelines and their implementation remain fit for purpose. Pursuant to this, in 2021, the Working Party initiated a Stocktaking of the MNE Guidelines to help identify key issues for a potential targeted update. The Stocktaking Report identified climate change as a priority issue and text on climate change has been added to a proposed updated draft of the MNE Guidelines. The public consultation on the draft ended in February 2023, with the outcome of the targeted update expected to be issued later this year.

OECD Due Diligence Guidance for RBC

To help businesses (including financial institutions and investors) implement the MNE Guidelines, the OECD developed the Due Diligence Guidance for RBC as well as specific sector guidance. These provide concrete recommendations on how businesses can identify, prevent and mitigate actual and potential adverse impacts of their operations (including in their supply chains, business relationships and investments) on people and the planet while contributing to sustainable development.

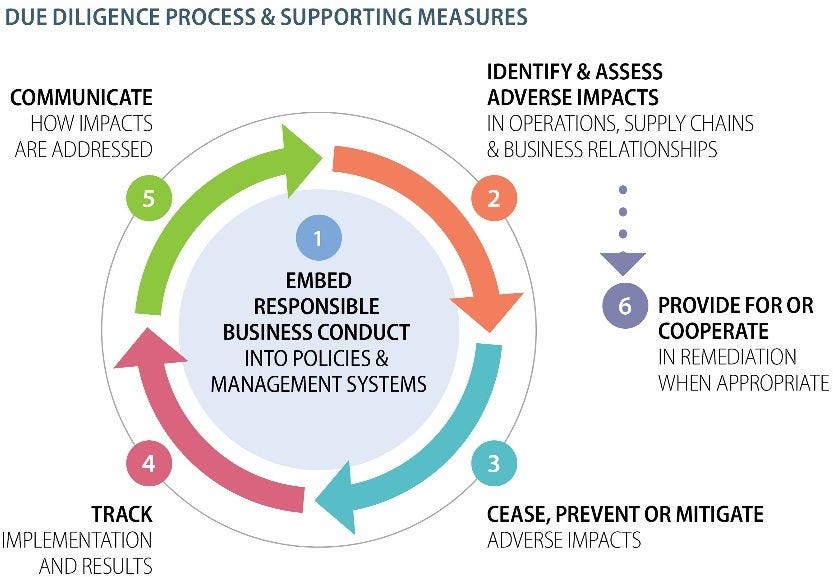

The core measures for implementing RBC due diligence are outlined below (Figure 9.2). These six steps together with detailed practical actions and examples for implementing them are described in more detail in the OECD Due Diligence Guidance.

Figure 9.2. The due diligence process

RBC expectations relevant to the net-zero transition include businesses having a responsibility to i) reduce GHG emissions and the adverse climate-related impacts of their operations on people and the planet; and ii) strengthen the climate resilience of companies, including across supply chains, to address and adapt to the impacts of climate change (this extends to addressing impacts on workers, local communities and the natural environment) (OECD, 2021[32]).

The comprehensive nature of the RBC framework means that in implementing net-zero commitments (and the expectations referred to above), businesses are also required to take into account the interlinkages with other areas of business responsibility including those extending to disclosure, science and technology, human rights, workers, competition and consumer interests (OECD, 2021[32]). In this way, the MNE Guidelines offer a framework to support businesses in avoiding or mitigating adverse impacts stemming from the implementation of net-zero commitments and their transition pathways, thereby strengthening the credibility and consequently the resilience of net-zero transitions globally.

Building the resilience of supply chains critical to the transition

The comprehensive approach of the RBC framework also provides guidance for businesses, trade unions, and governments in strengthening the resilience of global supply chains more broadly (OECD, 2021[33]). This is relevant to not only building robust supply chains in response to the impacts of climate change but ensuring that supply chains critical to the net-zero transition can bounce back from global shocks and disruptions (including, but also going beyond, those related to climate impacts).

The debate on how to build long-term resilience in supply chains, including how to diversify supply chains while remaining unwaveringly committed to open and rules-based trade, is at the forefront of policy discussions following the COVID-19 pandemic and has been amplified most recently by Russia’s unprovoked war against Ukraine (see also Chapter 3).

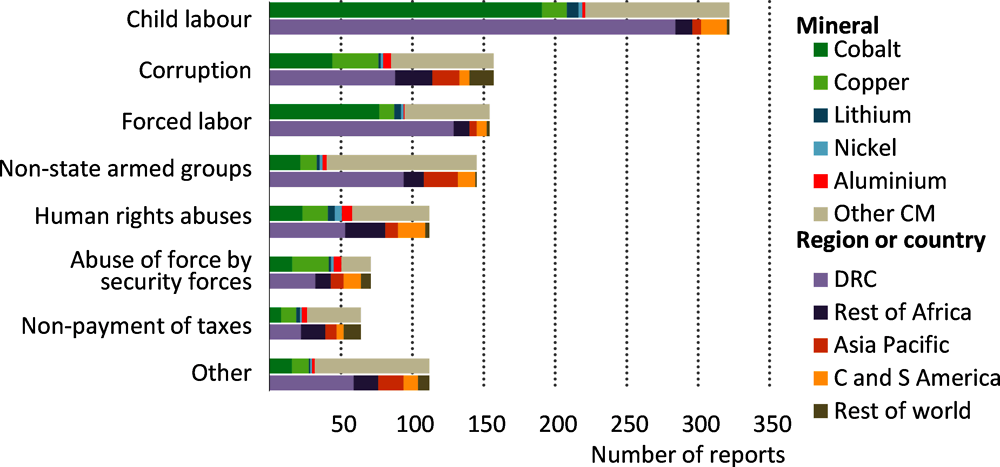

This is especially evident in the context of sourcing critical raw materials needed for the transition to renewable energy. As mentioned in Chapter 5, achieving the climate mitigation objectives of the Paris Agreement would mean quadrupling minerals supply for clean energy by 2040 (IEA, 2021[34]). To diversify sourcing of these materials, sourcing from conflict-affected or high-risk areas will be unavoidable. The production of critical minerals is highly concentrated in a few countries, including areas where RBC-related risks are prevalent (Figure 9.3) (Katz, 2021[35]). For example, it is estimated that nearly 50% or more of current volumes of cobalt, copper and are found in areas with significant governance challenges (IEA, 2021[34]). Recent estimates also suggest that more than half of the world’s resources of energy-transition minerals and metals are located on or near the lands of Indigenous peoples, whose rights and claims over their lands and natural resources require specific processes for extracting companies and related government authorities (Owen et al., 2022[36])

Figure 9.3. Public reports of RBC-related risks by mineral supply chain and by region (2017-2019)

Incidences of RBC-related adverse impacts can erode public support for mining projects and increase scrutiny from downstream industries, investors and civil society. This potentially leads to short-term production disruptions and local and international resistance to mining investments. This may, in turn, limit the supply of critical minerals and metals, jeopardising the resilience of the net-zero transition. Failure to properly manage these risks may also expose governments and companies to regulatory, ethical and reputational criticism.

RBC standards play an important role in supporting the responsible operation of minerals supply chains. By providing guidance on how to mitigate adverse risks and impacts, including in a way that is necessary to attract needed investment, the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (the Minerals Guidance) and the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Meaningful Stakeholder Engagement in the Extractive Sector can help businesses and governments strengthen the durability of critical minerals supply chains through RBC. This, in turn, supports the resilience of the net-zero transition, given its reliance on energy-transition minerals and metals (Box 9.4).

Box 9.4. Shared standards on RBC in promoting responsible supply of critical raw materials

Shared standards and practices on RBC are essential to promote trust, facilitate trade and ensure the sustainable supply of goods (see also Box 10.1). These elements are all critical to building the resilience and durability of supply chains, and their ability to bounce back from global shocks and disruptions.

An inability to identify and mitigate environmental and social harms can make it difficult to obtain – and maintain – a social licence to operate; exacerbating community tensions and leading to community pressure, adverse publicity and regulatory challenges. There have been numerous cases in recent years where local opposition has stopped or slowed new minerals developments; for example, high-profile lithium projects in Bolivia and Serbia (IEA, 2022[37]).

Specific supply chain incidents may also give rise to short-term supply disruptions with implications for supply chains and prices. For example, safety failures can harm workers and lead to long-term interruptions to operations. In addition, corruption in the mining sector and a volatile business climate appear to be associated with periodic shut-downs and shake-downs of mine sites producing energy transition minerals – which all can be better identified and mitigated when robust RBC due diligence is conducted.

Having sound RBC management practices in place before a shock occurs can help businesses respond faster and more effectively, thus minimising the severity of its impact. After a shock has occurred, an RBC-based response can contribute to minimising environmental and social impacts while also preventing or limiting the cascading effects of disruptions, thus strengthening the entire supply chain. Conversely, irresponsible business practices can amplify the knock-on effects and environmental and social impacts of disruptions (OECD, 2021[33]). In this way, the RBC framework is also an important tool for supporting private sector action aligned with a just transition by integrating the consideration of social and environmental adverse impacts into business decision making and risk management processes.

With the rise of legislation such as the EU Conflict Minerals Regulation or Section 1502 of the U.S. Dodd-Frank legislation, observing shared standards and establishing responsible sources of supply is increasingly becoming an imperative for companies and a factor of strategic security of supply in ensuring the resilience of these supply chains critical to the net-zero transition. (OECD, 2021[33])

Furthermore, unco-ordinated strategies and competitive behaviours (i.e. strategic stockpiling, commodity speculation, fuel price rises) among key actors, including governments, engaged in the global race to supply and procure minerals could inadvertently derail the net-zero transition and impede the scaled development of clean technologies needed to meet global climate goals. Promoting a level playing field and strengthening policy efforts aimed at all tiers of the value chain – from mining to end-use products – based on RBC standards can create a common baseline and help foster an orderly and fair transition toward net zero (OECD, 2021[33]).

Source: OECD, IEA.

Chapter conclusions

An accelerated and resilient net-zero transition necessitates the climate alignment of finance flows. Strengthening market practices is critical in enabling these efforts and safeguarding the resilience of the transition by ensuring investments result in long-term net-zero-aligned action in the real economy. Although there is progress, market practices require further reform in driving these efforts. This includes improving global collaboration, interoperability and comparability across ESG investing approaches; strengthening the availability and use of reliable, comparable, and high-quality metrics and data to assess physical and transition climate risks and opportunities; and harnessing ESG approaches to focus more on the alignment of real-economy investments with climate objectives.

In addition, government policies can work to harness and redirect key public and private finance flows to accelerate the net-zero transition and ensure they do not increase the vulnerability or fragility of systems, undermining the resilience of the transition itself. Scaling and directing Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to align with net-zero objectives, as recommended by the OECD FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit3, is a key example. Exploring how investment treaties potentially threaten the resilience of the net-zero transition or support the climate alignment of finance flows, is a second.

More broadly, businesses are a critical conduit for realising emissions reductions and adaptation through their direct operations and across their supply chains. Private sector net-zero commitments need to be implemented with integrity. This means not only avoiding greenwashing but taking into account “just transition” priorities across all areas of business operations. The OECD Responsible Business Conduct (RBC) framework guides governments and businesses in implementing these responsibilities, including on supply-chain due diligence to improve supply-chain resilience (especially in the context of climate impacts). OECD Due Diligence Guidance can also play a key role in the responsible and sustainable sourcing of critical raw materials required for the transition to renewable energy.

References

[10] Boffo, R., C. Marshall and R. Patalano (2020), ESG Investing: Environmental Pillar Scoring and Reporting, http://www.oecd.org/finance/esg-investing-environmental-pillar-scoring-and-reporting.pdf.

[17] Braun, S. (2021), Multi-billion euro lawsuits derail climate action, Deutsche Welle, https://www.dw.com/en/energy-charter-treaty-ect-coal-fossil-fuels-climate-environment-uniper-rwe/a-57221166.

[7] Dobrinevski, A. and R. Jachnik (2020), “Exploring options to measure the climate consistency of real economy investments : The manufacturing industries of Norway”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 159, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1012bd81-en.

[6] Dobrinevski, A. and R. Jachnik (2020), “Exploring options to measure the climate consistency of real economy investments: The transport sector in Latvia”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 163, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/48d53aac-en.

[13] G20 SFWG (2022), 2022 G20 Sustainable Finance Report, Sustainable Finance Working Group, https://g20sfwg.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2022-G20-Sustainable-Finance-Report-2.pdf.

[19] Gaukrodger, D. (2022), “Investment treaties and climate change: The alignment of finance flows under the Paris Agreement”, https://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/oecd-background-investment-treaties-finance-flow-alignment.pdf.

[20] Hodgson, M., Y. Kryvoi and D. Hrcka (2021), “2021 Empirical Study: Costs, Damages and Duration in Investor-State Arbitration”, https://www.biicl.org/documents/136_isds-costs-damages-duration_june_2021.pdf.

[37] IEA (2022), Why is ESG so important to critical mineral supplies, and what can we do about it?, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/why-is-esg-so-important-to-critical-mineral-supplies-and-what-can-we-do-about-it.

[34] IEA (2021), The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions, https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ffd2a83b-8c30-4e9d-980a-52b6d9a86fdc/TheRoleofCriticalMineralsinCleanEnergyTransitions.pdf.

[12] IMF (2022), Scaling up Climate Finance in Emerging market and developing economies.

[5] Jachnik, R. and A. Dobrinevski (2021), “Measuring the alignment of real economy investments with climate mitigation objectives: The United Kingdom’s buildings sector”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 172, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8eccb72a-en.

[35] Katz, B. (2021), Making global value chains for critical minerals more resilient through diversification and due diligence.

[24] Net-Zero Tracker (2022), Net-Zero Stocktake 2022: Assessing the status and trends of net zero target setting, https://zerotracker.net/insights/pr-net-zero-stocktake-2022.

[3] Noels, J. and R. Jachnik (2022), Assessing the climate consistency of finance: taking stock of methodologies and assessing their links to climate mitigation policy objectives, OECD, https://one.oecd.org/official-document/ENV/EPOC/WPCID(2022)12/REV1/en.

[16] Novik, A. and D. Gaukrodger (2022), Investment Treaties and Climate Change: Paris Agreement and Net Zero Alignment - agenda, https://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/draft-agenda-oecd-investment-treaties-climate-change-conference.pdf.

[11] OECD (2022), “ESG ratings and climate transition: An assessment of the alignment of E pillar scores and metrics”, OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers, No. 06, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2fa21143-en.

[14] OECD (2022), FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit.

[8] OECD (2022), OECD Guidance on Transition Finance: Ensuring Credibility of Corporate Climate Transition Plans, Green Finance and Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7c68a1ee-en.

[33] OECD (2021), Building more resilient and sustainable global value chains through responsible.

[4] OECD (2021), ESG Investing and Climate Transition: Market Practices, Issues and Policy Considerations, https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-investing-and-climate-transition-Market-practices-issues-and-policy-considerations.pdf.

[9] OECD (2021), Financial Markets and Climate Transition: Opportunities, Challenges and Policy Implications, https://www.oecd.org/finance/Financial-Markets-and-Climate-Transition-Opportunities-Challenges-and-Policy-Implications.pdf.

[32] OECD (2021), The role of OECD instruments on responsible business conduct in progressing.

[26] OECD (2018), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct.

[27] OECD (2018), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment and Footwear Sector, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264290587-en.

[28] OECD (2017), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Meaningful Stakeholder Engagement in the Extractive Sector, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252462-en.

[29] OECD (2017), Responsible business conduct for institutional investors: Key considerations for due diligence under the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.

[30] OECD (2016), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas: Third Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252479-en.

[15] OECD (2015), Policy Framework for Investment, 2015 Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208667-en.

[25] OECD (2011), OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, 2011 Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264115415-en.

[31] OECD/FAO (2016), OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264251052-en.

[36] Owen, J. et al. (2022), “Energy transition minerals and their intersection with land-connected peoples”, Nature Sustainability, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00994-6.

[18] Reuters (2020), German government approves lignite compensation contract, https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/german-government-approves-lignite-compensation-contract-2020-12-16/.

[23] Science Based Targets (2021), The Net Zero Standard, https://sciencebasedtargets.org/net-zero#:~:text=The%20SBTi's%20Corporate%20Net%2DZero,rise%20to%201.5%C2%B0C.

[21] Tienhaara, K. et al. (2022), “Investor-state disputes threaten the global green energy transition”, Science, Vol. 376/6594, pp. 701-703, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abo4637.

[22] UNCTAD (2022), “Investment dispute navigator”, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-dispute-settlement.

[1] UNFCCC (2016), Decision 1/CP.21 - Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-first session, held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015, https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf#page=2.

[2] United Nations (2022), Integrity Matters: Net Zero Commitments by Businesses, Financial Institutions, Cities and Regions.

Notes

← 1. The OECD FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit offers a framework for governments to leverage the catalytic role of foreign direct investment in financing the SDGs and supporting an inclusive and sustainable recovery and future growth.

← 2. For example, the UN-convened Asset Owners Net Zero Alliance and the Net Zero Asset Managers both launched in 2019, the UN’s Environmental Programme’s Financial Initiative’s (UNEP FI) Net Zero Banking Alliance launched in 2021, and the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) launched at COP26 in 2021, bringing together existing and new net-zero finance initiatives, representing 450 financial firms with a total and estimated USD 130 trillion in assets under management.

← 3. The OECD FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit offers a framework for governments to leverage the catalytic role of foreign direct investment in financing the SDGs, and supporting an inclusive and sustainable recovery and future growth.