Climate change is a global problem requiring globally coordinated responses, meaning that development cooperation has a key role to play in supporting design of policies that align development priorities with climate objectives. This chapter draws on OECD work on aligning development and energy transitions, and greening developing countries’ financial systems. It uses these sectoral examples to provide insights into: (i) how a global response to climate action is inherent to resilient climate policy making today, and (ii) the role of development co-operation in supporting aligned transitions towards net zero and countries’ development objectives.

Net Zero+

10. Interlinkages between the net‑zero transition and development

Abstract

This chapter draws on contributions to the Horizontal Project carried out under the responsibility of the Development Assistance Committee.

Achieving the Paris Agreement goals requires a transition towards net-zero emissions globally, with the types and speed of climate action by countries depending on their national circumstances and capabilities. This necessitates a globally co-ordinated response, with policy approaches tailored to differing national circumstances, and financial and non-financial support to developing countries. Due to economic and population dynamics, developing countries are set to account for the bulk of energy generation and consumption – and, on current trajectories, emissions growth – in the coming decades. They will need strong development co-operation providers to enable their net-zero transitions (IEA, 2021[1]).1

Given the scale of the climate emergency described in Part I of this report, the development process is now inextricably interwoven with policy responses to climate change. This is apparent in the need to adapt and build resilience to the increasingly severe impacts of climate challenge to which large numbers of people are particularly vulnerable (discussed further in Part III). It is also true as developing countries consider how to accelerate their development process while implementing progress towards net-zero emissions in their national context.

The momentum of development transitions can be leveraged to progress in tandem with transformative action on climate.

This chapter draws on OECD work on aligning development and energy transitions, and greening developing countries’ financial systems. It provides insights into: (i) how a global response to climate action is inherent to resilient climate policy making today, and (ii) the role of development co-operation in supporting aligned transitions towards net zero and countries’ development objectives.

The role of development co-operation in climate-aligned development

Important synergies or points of alignment exist between development objectives and a resilient net-zero transition, particularly in the longer term. Given the limited resources and financing challenges of developing countries, and the need to avoid redundancies and contradictions in development and climate efforts, understanding the relationship between climate and development is critical (OECD, Forthcoming[2]).

Developing countries’ heightened vulnerability to climate change impacts poses broad risks across socio-economic systems. This makes climate adaptation objectives essential and inseparable from the development process. Economic development is a driving force for reshaping sectors and systems, and allows governments to align socio-economic systems with the transition to net zero.

Recent global events have also demonstrated the interconnected nature of development and climate priorities, and the need to consider both in safeguarding the resilience of local and global action towards net zero. For example, amidst the enduring effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war of Ukraine, limited fiscal space, volatile market frameworks and significant tightening of monetary policy in response to inflationary shocks may lead developing countries to favour fossil fuel-based technologies (see also Chapter 3). Even in cases where renewable energy is increasingly cheaper than fossil fuel alternatives, financial constraints and the need to universally provide affordable and reliable energy services represent formidable challenges for developing countries (Taskin, 2022[3]). Development co-operation has a crucial and evolving role to play in this process (IEA, 2021[1]). It should provide general support for energy transitions in partner countries and specific support via multilateral and bilateral development banks (OECD, 2021[4]).

IEA analysis finds that policy support, capacity building and direct financing is needed to promote market maturity and lower risks to private capital to increase willingness to invest in net-zero technologies and related projects in developing countries. Development co-operation needs to use all levers of support – provision of financial resources, capacity building and policy support (OECD, 2019[5]; World Bank, 2020[6]), and has a particular role in supporting just energy transitions in developing countries.

The two sector-focused examples below illustrate how development co-operation can act as a conduit for aligned development and the net-zero transition, and work towards embedding resilience in the net zero transitions.

Aligning climate and development priorities to drive the net-zero transition: the energy sector in developing countries

Meeting developing countries’ rising energy demands is important for delivering development priorities, enabling growth and reducing poverty (Stern, 2011[7]; Shahbaz et al., 2018[8]; Burke, Stern and Bruns, 2018[9]). Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 sets the objective of universal access to modern energy services for all and establishes targets to be attained by 2030 for energy access, renewable energies and energy efficiency.

Developing countries generally focus on three main priorities when developing their energy systems:

Modern energy services such as electricity and clean cooking play a crucial role in decreasing poverty, achieving better health and education, and reducing inequalities. Today, 733 million people lack access to electricity and 2.4 billion people lack access to clean cooking appliances and fuels (IEA, IRENA, UNSD, World Bank, WHO, 2022[10]). Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the world was off track to reach universal access to energy by 2030. The ensuing global energy crisis is now expected to increase the number of people living without electricity by nearly 20 million in 2022, mostly driven by an increase in unserved populations in sub-Saharan Africa (IEA, 2022[11]). Insufficient access to finance is a key barrier to progress on energy access: in countries with the largest access deficits, the level of finance is only around one third of required volumes to reach SDG 7 (Sustainable Energy for All, 2021[12]).

Energy affordability is a priority for developing countries in order to meet growing demand and safeguard and build on past development gains. Developing countries collectively make up almost two-thirds of the global population today and will drive global population growth over the coming decades. This population growth, combined with the energy access challenge, rapid urbanisation, growth in industrial activity and increasing demands for a better quality of life translate into developing countries representing the largest sources of global energy demand growth (IEA, 2021[1]).

Energy security. Disruptions in energy supply and systems have the potential to limit economic and societal development. This leads to countries taking a long-term and short-term approach to energy security by addressing energy supply investments in line with development needs and strengthening the ability of the energy system to react to sudden changes in the supply-demand balance (Taskin, 2022[3]).

Developing countries’ net-zero transitions must reflect and respond to all three priorities in order to maintain progress in the face of development objectives interlinked with global shocks or disruptions.

Moreover, while all developing countries recognise the universal provision of affordable and reliable energy services as crucial to their development, the specific relevance attached to this priority differs depending on individual countries’ development stage. For example, some developing countries may give higher priority to reliability and security, given their economic dependence on hard-to-decarbonise industries like steel and cement. For others, particularly some on the African continent, affordability is the absolute priority, which requires advances on energy and material efficiency to help curtail demand growth (IEA, 2022[13]).

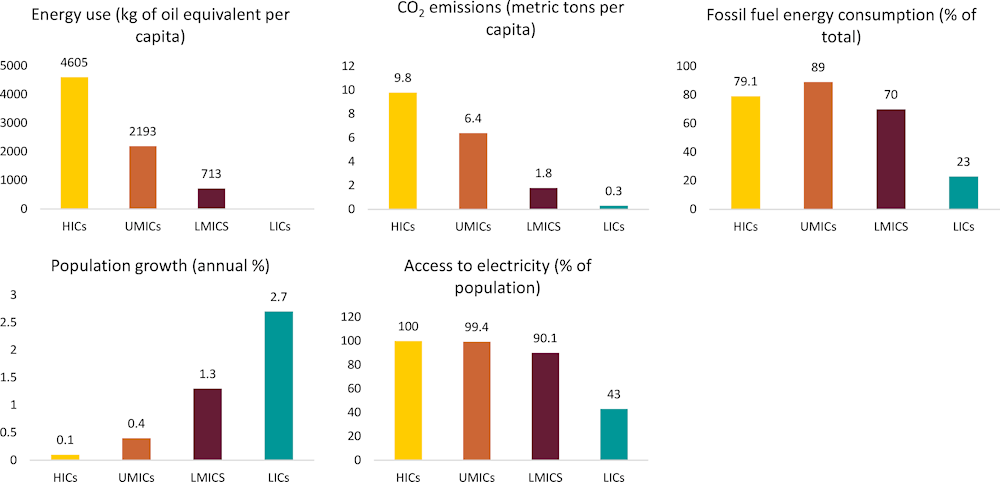

Further, developing countries’ existing energy mixes vary widely depending on their level of development, available resources, and policy choices. Some developing countries are among the largest energy consumers globally, while others are major energy suppliers. Some are leading the deployment of clean energy technologies while others are just beginning to strengthen policies for clean energy promotion. Figure 10.1 provides an overview of selected indicators highlighting the different starting points of developing countries in their energy transitions. This demonstrates the importance of taking into account varying developing country contexts when pursuing policy approaches that support development (particularly in the context of energy) transitions and transitions to net zero.

Figure 10.1. Selected indicators relevant for energy transitions

Note: HICs = High-income countries; UMICS = Upper middle-income countries; LMICs = Lower middle-income countries; LICs = Low-income countries. No data available for energy use for LICs.

Source: (World Bank, 2022[14]).

Development finance for the energy sector

Large shares of bilateral and multilateral development finance have supported the energy sector in the last decades, reflecting the importance of energy for development and developing countries’ expressed priorities. From the 1980s until the mid-1990s, the share of multilateral development finance for energy oscillated between 15% and 20% of total multilateral finance while bilateral development finance for energy was in the range of 5% to 10% of total bilateral support (Taskin, 2022[3]).

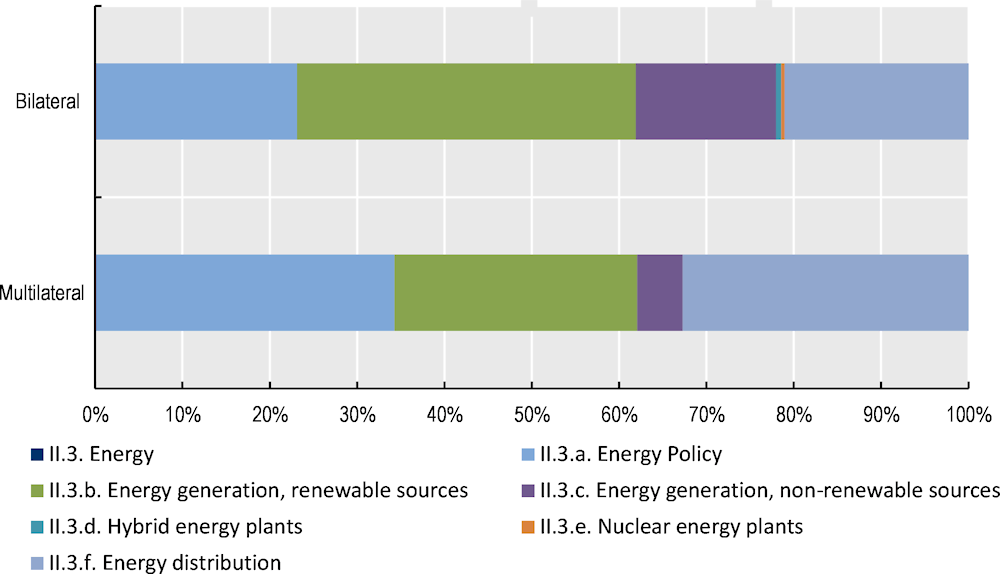

Support to the energy sector usually targets three main areas: i) energy policy, ii) energy distribution and iii) energy supply (see also Chapter 5). All three have a key role to play in net-zero transitions (Figure 10.2). Since 2016-2020, support to renewable energy supply has been the major focus of both bilateral and multilateral institutions, followed by energy distribution and energy policy (Taskin, 2022[3]). A large part (74%) of bilateral official development assistance (ODA) for energy policy has a mitigation objective.

Figure 10.2. Bilateral and multilateral support to energy sub-sectors

Support to strengthen energy policy for the transition is particularly important given the wide-ranging and often system-level challenges many developing countries face in pursuing ambitious sustainable energy policies. This includes establishing policy frameworks that enable commercial capital to be mobilised for the transition (OECD, 2022[16]).

The three key target areas for development finance directed to the energy sector of developing countries also demonstrate the overlap between development and net-zero transition priorities for this sector and how development co-operation can be utilised in harnessing synergies between both transitions. Specific challenges and opportunities for this process are addressed below.

Policy and financing challenges for developing country energy transitions

A surge in clean energy investment in developing countries to USD 1 trillion annually in 2030 can help address the emissions growth projected for developing countries while strengthening developing countries’ development prospects (IEA, 2021[1]).2 Renewable energy power production has a low levelised cost of energy (LCOE) in an increasing number of developing countries (IEA, 2021[1]; IRENA, 2022[17]; IEA, 2021[18]).3 Relatedly, clean energy investment in developing countries is a cost-effective way to reduce emissions on a global basis. Around 35% of the emissions reductions that occur in developing countries over the next decade are estimated to have negative abatement costs, meaning they would reduce emissions and save money (IEA, 2021[1]).

Two interlinked challenges need to be addressed to increase investment:

First, developing countries have constrained access to finance to drive the transition due in part to underdeveloped domestic financial sectors.

Second, developing countries often have limited capacities, including to develop ambitious Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and sector-level decarbonisation plans, both of which involve developing sustainable energy policies and regulations, and integrating these into NDCs and long-term low-emissions strategies (LTSs).

Developing countries lack access to capital

While there is no shortage of global capital, developing countries often lack access to it. This makes upfront investment in, for example, renewable energy difficult. While renewable energy power production is overall cheaper, it is more capital-intensive than fossil-fuel alternatives (IEA, 2021[1]; IRENA, 2022[17]; IEA, 2021[18]). This is especially challenging as the cost of capital is consistently and significantly higher in developing countries than in developed countries (Box 10.1), making it more difficult for developing countries to raise debt finance and meet expected return rates on equity.

This is particularly relevant as private, debt-financed investments are expected to play a major role in funding the net-zero transition. While today’s energy investments in developing countries rely heavily on public finance (in particular, through state-owned enterprises), the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that a decisive shift in financing towards private sources is needed to meet energy needs and reach net zero (IEA, 2021[1]). However, the amounts of private finance mobilised for the net-zero transition in developing countries are below expectations (OECD, 2022[16]). Instead, most private climate finance currently mobilised by developed countries targets projects in middle-income countries with relatively conducive enabling environments and low-risk profiles (OECD, 2022[16]). Development co-operation must go beyond transaction-level approaches such as blended finance and increase support for greening financial systems.

Box 10.1. Challenges associated with the cost of capital in developing countries

Developing countries are among the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and require large amounts of finance to green their economies and invest in adaptation actions. However, mobilising climate finance for developing countries has been a challenge, and capital flows have consistently fallen short of the level needed. Heightened macroeconomic risks, underdeveloped or shallow financial sectors, and challenges associated with investing in projects such as an absence of strong contract enforcement and other arrangements that support predictable revenues or subsidies that continue to favour investment in unsustainable technologies lead to higher economy-wide costs of capital in developing countries. Hence, their insufficient access to finance. More specifically, the IEA outlines that nominal financing costs in developing countries are up to seven times higher than in Europe or the United States (IEA, 2021[1]). This is particularly significant given the capital intensity of low-carbon investments, as described above.

These challenging conditions can result in a “climate investment trap” severely limiting low-carbon investments in developing countries. In the face of high weighted average costs of capital (WACCs), investors are frequently deterred from investing in low-carbon assets and technologies in developing markets, leading to insufficient mitigation efforts. This potentially results in worse climate and economic impacts in developing countries, which may reinforce domestic risks and hinder development of financial markets, feeding back into high WACCs in a vicious circle (Ameli et al., 2021[19]).

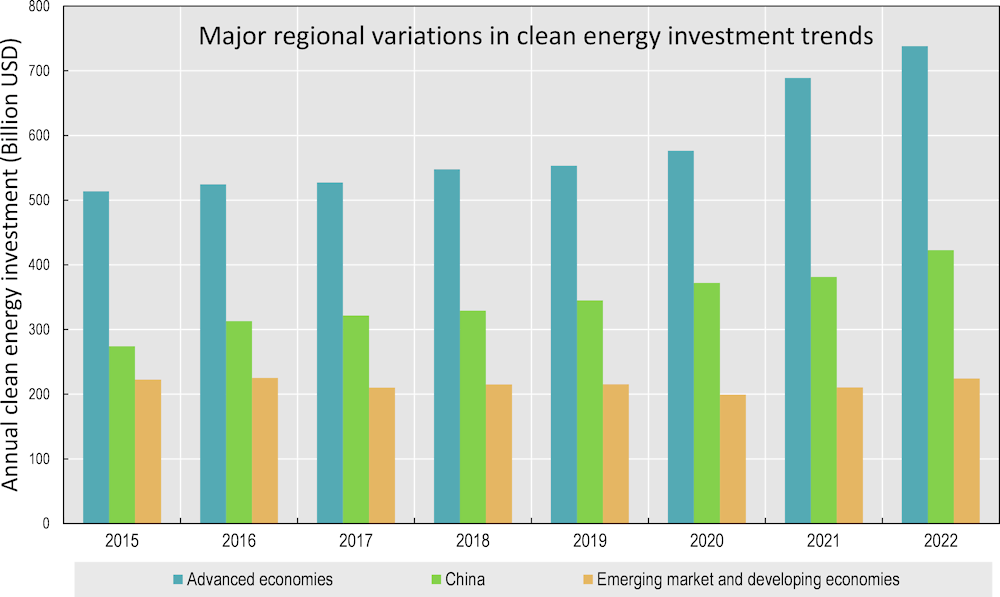

In the face of these challenges, investment has remained limited in developing countries (Figure 10.3). While clean energy investment worldwide has risen significantly since the signing of the Paris Agreement, it remains broadly at 2015 levels in developing countries (with the exception of China) (IEA, 2022[20]). This growing gap will need to be addressed for a global net-zero transition.

Figure 10.3. Trends in annual clean energy investment by region

Greening developing countries’ financial systems

Greening the financial systems of developing countries is critical to aligning development and climate objectives – including and beyond the energy sector – and enabling a resilient global transition to net zero.

The Sharm el Sheikh Implementation Plan for the first time expressly referenced the need to transform the “financial system and its structures and processes, engaging governments, central banks, commercial banks, institutional investors and other financial actors” (UNFCCC, 2022[22]) in order to operationalise Article 2.1 (c) of the Paris Agreement and deliver on the investment required to reach net zero emissions. The strategic use of development finance to green developing countries’ financial systems will be key to supporting progress on this commitment (OECD, 2019[23]).

Box 10.2. Defining “green” financial systems

This section, based on the OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS), defines green financial systems as: systems of public and private finance that integrate nature and climate-related externalities and allocate and intermediate financial resources on true cost and risk-effective pricing.

Existing approaches to green financial systems include:

Policy and regulatory action by governments to establish financial sectors that integrate nature and carbon externalities into financial decision-making, including through carbon markets and pricing, energy tax and subsidy reform, and emission trading systems.

Public financial management and budgetary processes that seek alignment with environmental objectives.

Policy and regulatory action by central banks and financial regulators to mitigate climate- and other nature-related risks to the financial sector, including through enhanced supervisory review and risk disclosure.

Action by financial institutions to create and use instruments and products that account for nature- and climate-related risks and opportunities (for example, green bonds, and improve the needed evidence base, e.g. taskforces on climate-and nature-related financial disclosures) (OECD, forthcoming[24])

Source: OECD.

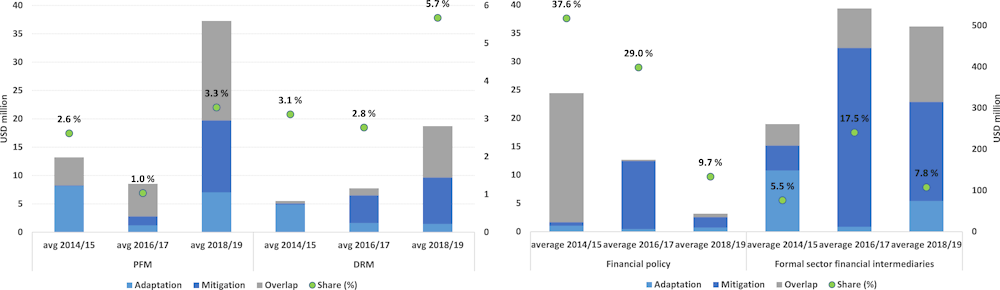

Development co-operation has long supported the development of public and private financial systems in developing countries. Such support is targeted towards five key sectors: (i) public finance management, (ii) domestic revenue mobilisation, (iii) financial policy, (iv) financial intermediaries, and (v) monetary institutions. However, a top-down analysis of climate-related development finance (via the OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS)) reveals that efforts to support developing countries in greening their financial systems remains limited to date.4 As further detailed in Box 10.3 below, there is a clear opportunity to strengthen the role of development finance in supporting the systemic integration of climate objectives across developing countries’ financial systems.

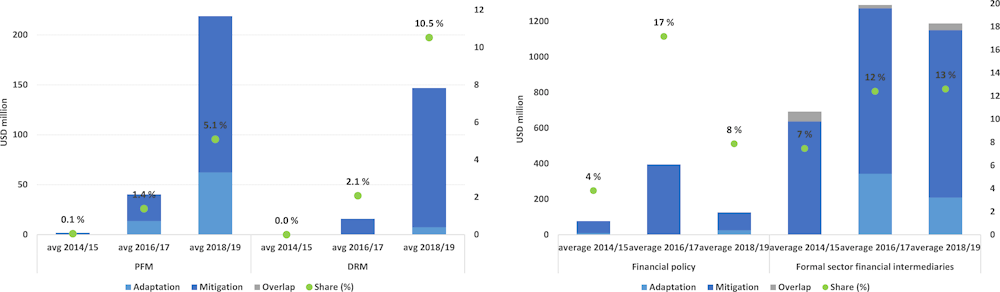

Specifically, climate-related development finance from all providers increased from 2014 to 2020, amounting to USD 98 billion in 2020 (OECD, 2022[25]). In contrast to climate-related development finance overall, there is no identifiable pattern in climate-related support to financial systems for the 2014‑2020 period (See Figure 10.4 on support from bilateral donors and multilateral funds, and Figure 10.5 on support provided by MDBs). This is noteworthy given countries’ 2015 commitment to align all financing flows with the global mitigation and adaptation goals as expressed in the Paris Agreement, Article 2.1(c), (UNFCCC, 2015[26]; UNFCCC, 2015[26])), and developed countries’ commitment to support developing countries in their contribution to the Paris Agreement goals (Article 9).

Moreover, despite the relevance assigned to central banks and financial regulators to address climate change - as reinforced in the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan – climate-related development finance to monetary institutions did not involve significant volumes over the 2014-2019 period.

Box 10.3. Initial assessment of trends and flows for climate-related support to financial systems in developing countries

Climate-related support to formal sector financial intermediaries (FSFI) such as banks and insurance companies from bilateral sources and multilateral funds reached an average of USD 433 million per year from 2014 to 2019. This was followed by support to financial policy amounting to USD 185 million per year on average (Figure 10.4).

Figure 10.4. Climate-related development finance (Rio market methodology) provided to sectors relevant for financial systems development

Note: PFM = Public finance management; DRM = Domestic revenue mobilisation; FP = Financial policy; FSFI = Formal sector financial intermediaries; avg = average. Climate-related support to monetary institutions not depicted as limited in absolute and relative terms.

Source: Creditor Reporting System (database), https://stats.oecd.org/; Climate Change OECD DAC External Development Statistics (database), http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/climate-change.htm.

In relative terms, however, the share of climate-related finance supporting financial sector policy overall was the highest over 2014-19, with 25% on average. Relevant support to public finance management (PFM), domestic revenue mobilisation (DRM) and support to monetary institutions was much less pronounced, reaching respectively USD 20 million, USD 11 million and USD 3 million on average per year over the same period. Although climate-related support in PFM and DRM increased overall from 2014 to 2019, climate-related support for financial policies decreased significantly in absolute and relative terms.

Across sectors, support targeted mitigation and adaptation objectives, while support to FSFI focused on mitigation only.

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) focused their support to green financial systems over 2014 to 2019 both in absolute and relative terms on support to formal sector financial intermediaries (FSFI).

Following a steep increase after 2014/15, climate-related support to FSFI reached on average USD 1 billion, or 11% of support to these institutions overall. This is likely based on the business model of development banks that relies on the provision of loans – for example in the form of green credit lines – and less on the provision of policy and regulatory support and capacity building.

Climate-related support to PFM and DRM by MDBs increased over 2014-2019 in both absolute and relative terms, with particularly steep increases from 2016/17 to 2018/19. Across sectors and years, support from MDBs to green developing country financial systems focused on mitigation (Figure 10.5)

Figure 10.5. Climate-related development finance provided by multilateral development banks to sectors relevant for financial systems development

Note: PFM = Public finance management; DRM = Domestic revenue mobilisation; avg = average . Climate-related support to monetary institutions not depicted as limited in absolute and relative terms.

Source: Creditor Reporting System (database), https://stats.oecd.org/; Climate Change OECD DAC External Development Statistics (database), http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/climate-change.htm.

As is the case for support provided by bilateral providers and multilateral funds, climate-related development finance to monetary institutions did not involve significant volumes over the 2014-2019 period, despite the relevance assigned to central banks and financial regulators in promoting climate-related risk management in the financial sector, strengthening financial stability in a changing climate, and mobilising finance for climate outcomes.

Support to green financial systems in different country groups and via different instruments

Between 2014 and 2019, support to green financial systems was mostly provided to middle income countries (MICs). FSFI were almost exclusively supported in MICs. Low-income countries (LICs) rely more on informal and semi-formal financial institutions than FSFI, such as microfinance institutions ( (Demirgüç-Kunt and Singer, 2017[27])). Support from bilateral providers and multilateral funds in 2014-2019 reflects this, with 62% of climate-related development finance to financial institutions supporting the latter institutions.

Bilateral providers extended their support to green financial systems in LICs exclusively through grants, including in the areas of PFM and DRM. MDBs used both loans and grants in their support to LICs, with a stronger focus on loans. Importantly, in 2014-2019 support to green financial systems in LICs targeted to a larger degree adaptation objectives than in other income groups (44% of support focused on adaptation). Interestingly, support to green financial systems in SIDS focused largely on mitigation objectives.

Source: OECD.

Chapter conclusions

Development processes and climate policy action are inextricably linked. The systemic integration of climate priorities into development processes and policy can drive alignment and help to communicate the developmental interest of countries’ climate action. This has the additional benefit of embedding a multidimensional approach to climate policy action – a critical component to strengthening the resilience of the global net zero transition.

Understanding and responding to the interconnections between both development and climate transitions requires a strong focus on the energy sector. While developing countries have different starting positions to their energy transitions, they generally face two main challenges: Insufficient access to capital and insufficient capacities for the transition. This lends itself to “a common approach” to how development co-operation is provided by developed countries in the context of energy sector transitions.

Further to the energy sector focus, greening the financial systems of developing countries is essential to aligning development and climate objectives – including and beyond the energy sector, and enabling a resilient global transition to net zero. The Sharm el Sheikh Implementation Plan for the first time expressly referenced the need to transform the financial system in order to deliver on the Paris Agreement’s objectives.

While support to developing countries’ public and private financial system is a major focus of development co-operation, there is no positive trend in climate-related support to these systems and relevant sectors. In particular, despite the importance attached to central banks and regulators in enabling and driving the transition, no significant support – in absolute terms – can be detected from initial analyses.

References

[19] Ameli, N. et al. (2021), “Higher cost of finance exacerbates a climate investment trap in developing economies”, Nature Communications, Vol. 12/1, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24305-3.

[9] Burke, P., D. Stern and S. Bruns (2018), “The Impact of Electricity on Economic Development: A Macroeconomic Perspective”, International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics, Vol. 12/1, pp. 85-127, https://doi.org/10.1561/101.00000101.

[27] Demirgüç-Kunt, A. and D. Singer (2017), “Financial inclusion and inclusive growth: A review of recent empirical evidence”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper.

[13] IEA (2022), Africa Energy Outlook 2022, https://www.iea.org/reports/africa-energy-outlook-2022.

[11] IEA (2022), For the first time in decades, the number of people without access to electricity is set to increase in 2022, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/for-the-first-time-in-decades-the-number-of-people-without-access-to-electricity-is-set-to-increase-in-2022.

[20] IEA (2022), World Energy Investment 2022.

[1] IEA (2021), Financing Clean Energy Transitions in Emerging and Developing Economies, https://www.iea.org/reports/financing-clean-energy-transitions-in-emerging-and-developing-economies.

[18] IEA (2021), The cost of capital in clean energy transitions, https://www.iea.org/articles/the-cost-of-capital-in-clean-energy-transitions.

[10] IEA, IRENA, UNSD, World Bank, WHO (2022), Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report, https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/data/files/download-documents/sdg7-report2022-full_report.pdf.

[17] IRENA (2022), Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2021, https://www.irena.org/publications/2022/Jul/Renewable-Power-Generation-Costs-in-2021#:~:text=Globally%2C%20new%20renewable%20capacity%20added,at%20least%20USD%2050%20billion.

[25] OECD (2022), Climate Change: OECD DAC External Development Finance Statistics, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/climate-change.htm.

[16] OECD (2022), Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2016-2020: Insights from Disaggregated Analysis, Climate Finance and the USD 100 Billion Goal, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/286dae5d-en.

[15] OECD (2022), OECD Creditor Reporting System, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1.

[4] OECD (2021), Investing in the climate transition: The role of development banks, development finance institutions and their shareholders, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/Policy-perspectives-Investing-in-the-climate-transition.pdf.

[5] OECD (2019), Aligning Development Co-operation and Climate Action: The Only Way Forward, The Development Dimension, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5099ad91-en.

[23] OECD (2019), Aligning Development Co-operation and Climate Action: The Only Way Forward, The Development Dimension, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5099ad91-en.

[2] OECD (Forthcoming), Economic development and the climate transition: a review of the interlinkages between two transformative processes.

[24] OECD (forthcoming), Greening developing country financial systems: An overview of approaches and insights on the role of development co-operation.

[21] OECD (forthcoming, 2023), The role of the cost of capital in clean energy transitions.

[8] Shahbaz, M. et al. (2018), “The energy consumption and economic growth nexus in top ten energy-consuming countries: Fresh evidence from using the quantile-on-quantile approach”, Energy Economics, Vol. 71, pp. 282-301, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2018.02.023.

[7] Stern, D. (2011), “The role of energy in economic growth”, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 1219/1, pp. 26-51, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05921.x.

[12] Sustainable Energy for All (2021), Energesing Finance - Understanding the Landscape, https://www.seforall.org/system/files/2021-10/EF-2021-UL-SEforALL.pdf.

[3] Taskin, Ö. (2022), Supporting developing countries’ net zero transition: An introduction to development co-operation providers’ approaches, ONE,.

[22] UNFCCC (2022), Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2022_L21_revised_adv.pdf.

[26] UNFCCC (2015), Paris Agreement.

[14] World Bank (2022), , https://data.worldbank.org/.

[6] World Bank (2020), Transformative Climate FinanceA: A new approach for climate finance to achieve low-carbon resilient development in developing countries, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33917/149752.pdf.

Notes

← 1. This support includes delivering the commitment of providing and mobilising USD 100 billion per year and the broader support of development co-operation providers such as the commitments outlined in the OECD DAC Declaration on a new approach to align development co-operation with the goals of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change.

← 2. Excluding the People’s Republic of China.

← 3. The fall in costs is particularly important for utility-scale solar PV which can now compete with the cheapest new fossil fuel generation capacity, reaching a weighted average LCOE of USD 0.057/kWh (against costs for new coal power plants in the range of USD 0.055/kWh and USD 0.148/kWh). Other technologies such as concentrated solar power, onshore and offshore wind are also competitive or cheaper than fossil fuel-related electricity generation, without taking into account positive externalities.

← 4. Outlined in OECD background paper on “Greening financial systems in developing countries”.