Increased investment in adaptation will be a critical element in building resilience to the physical impacts of climate change and there is a crucial need to both align finance flows with climate-resilient development, as well as mobilising additional resources for necessary adaptation measures. This chapter provides an overview of adaptation finance, associated concepts and methods, and explores sources and mechanisms for increasing adaptation finance. This includes the importance of government policy in creating an enabling environment for aligning finance and investment flows with adaptation needs and the particular role of the insurance sector in this endeavour.

Net Zero+

13. Financing adaptation amid increasing climate risks

Abstract

This chapter draws on contributions to the horizontal project carried out under the responsibility of the Environment Policy Committee, the Development Assistance Committee and the Insurance and Private Pensions Committee.

Increased investment in adaptation will be critical for building resilience to the physical impacts of climate change. Consistent with Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement, there is a need to align finance flows with climate-resilient development and mobilise additional resources for necessary adaptation measures. Measures will be context-specific, but evidence suggests that there is a large unmet need for finance to implement necessary and urgent investments in adaptation.

Both public and private entities play a key role in financing adaptation. While additional public spending is essential to achieve adaptation goals, the adaptation investment gap cannot be filled by public funds alone. Beyond specific adaptation funding, all financial flows, whether public or private, domestic or international, will have important consequences for climate resilience. In addition to radically increasing spending on adaptation, financing adaptation also means aligning all finance flows and investments with resilience objectives to ensure they do not undermine adaptation efforts.

This chapter provides an overview of adaptation finance, associated concepts and methods, and explores sources and mechanisms for increasing adaptation finance, including the role of insurance.

Scaling up adaptation finance and aligning investment with climate resilience

The need to scale up adaptation finance

There is a large untapped potential for cost-effective investments in adaptation measures. (Neumann et al., 2021[1]) estimate that proactive adaptation can reduce the overall cost of climate change by a factor of 15. Looking at potential interventions, studies have found average benefit-cost ratios ranging from 2:1–10:1 for a sample of investments, including nature-based solutions (NbS) for flood risk management and climate-resilient infrastructure (Global Commission on Adaptation, 2019[2]) (Hallegatte, Rentschler and Rozenberg, 2019[3]). In terms of scale, the Global Commission on Adaptation has identified USD 1.7 trillion of potential investments across just five potential interventions.

Estimated adaptation financing needs for developing countries alone stand at between USD 140‑300 billion per year by 2030 and USD 280-500 billion per year by 2050 (UNEP, 2021[4]). This covers a wide range of potential adaptation efforts, ranging from education and training to the building of protective infrastructure, as well as building evaluation tools and strengthening the monitoring capacity of institutions (NAP Global Network, 2017[5]). Evaluating climate risks and adaptation needs also requires funding of researchers and expertise, observational technologies and data creation. Finally, adaptation planning requires capacities to analyse adaptation needs and translate them into adaptation objectives and plans.

Increasing adaptation needs also create new market opportunities, such as new adaptation technologies, innovative insurance schemes or data observation and collection tools. Some estimates put the value of the market created by adaptation at USD 26 trillion.1

Aligning investments with resilience

Financing adaptation requires not only mobilising additional funding but aligning investments from private and public actors with resilience. National governments should ensure coherence of local adaptation spending across sectors and levels of governments, and their alignment with national adaptation goals. At the same time, the funds needed for adaptation often far exceed public budgets and require the private sector to fill the gap (The World Bank, 2021[6]). Strengthening the enabling environment is essential for influencing the direction of the trillions of euros of investments that are made each year. Representing more than 80% of the investments made each year in OECD countries,2 the private sector constitutes an essential source of financing for adaptation. As companies experience or prepare for foreseeable effects of the impacts of climate change, they could autonomously finance part of their adaptation. The provision of private capital is especially key in financing large-scale projects such as building new infrastructure for which public-private co-operation is necessary (OECD, 2021[7]).

The need to align finance with climate-resilient development is embedded in article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement, yet efforts to define and operationalise this concept are at an early stage. A recent OECD paper defines the concept of "climate resilience-aligned investments” (Mullan and Ranger, 2022[8]), developing a framework for climate resilience financing based on three key principles. First is the identification and management of physical risks arising from climate impacts such as drought or floods. The analysis of these risks includes forward-looking information projecting future impacts and should take into account the intersection between hazards, exposure and vulnerability. The second “do no significant harm” principle is based on holistic risk management, which ensures that investments do not increase the risk faced by others (e.g. by increasing the risk of downstream flooding or damaging biodiversity). The third principle stipulates that investments must be aligned with adaptation strategies and objectives. The framework aims both to align all investments, i.e. to ultimately move away from financing projects that undermine resilience, and to increase “positively aligned” investments, which directly finance adaptation actions in line with relevant goals and plans (e.g. NAPs).

Aligning finance with adaptation and resilience goals does not necessarily mean divestment from activities that face higher physical climate risk. Indeed, this would risk drawing capital away from the most at-risk communities and potentially lead to maladaptation. Financial risk management without adaptation alignment would have negative outcomes for the most climate-vulnerable communities and particularly for lower-income countries and other developing countries with high vulnerability such as small island developing states (SIDS). Rather, alignment implies divestment from activities that create risk and proactively supporting adaptation and resilience efforts.

The public sector has an essential role in strengthening the enabling environment for adaptation aligned finance. First, governments can generate and share information on the risks and opportunities of climate change as well as promote guidelines and best practices to adapt to climate change. By investing in data sharing platforms and risk mapping tools (e.g. the Adaptation Support Tool from Climate ADAPT, a partnership between the European Commission and the European Environment Agency (EEA)),3 public institutions share climate data and climate risk assessments as a public good, and enable businesses and civil society to better understand the challenges associated with their activities (Mullan and Ranger, 2022[8]). Moreover, the public sector can gather information about successes and failures in financing adaptation to then guide private investors. The availability of knowledge about both climate impacts and how to finance adaptation allows investors to better manage current and future risks of climate change for their assets. By raising awareness of the benefits and avoided costs of adaptation measures, knowledge accumulation can also lead to proactive and autonomous efforts by others to manage those risks.

Governments can also support alignment by communicating clear adaptation objectives and needs, and by defining appropriate measures and targets to achieve them (Mullan and Ranger, 2022[8]). Governments can go further by defining the actors responsible for these actions as well as identifying potential funding needs and sources. The more detailed and long-term the government's strategy is, the more the various actors will be able to integrate the risks and opportunities of climate change into their investment strategies.

Governments have a range of economic and regulatory instruments to influence investments in the real economy (Mullan and Ranger, 2022[8]):

Grants: to support socially beneficial actions such as research and development of adaptation technologies, training, or changes in water use and agricultural practices. Subsidies are particularly useful for initiating changes in practice or usage. For example, the city of Linz, Austria helped residents to install green roofs by covering the cost of their installation up to 30%.4 Similarly, France subsidises the energy retrofitting of buildings by granting tax credits.5

Taxes and charges: to discourage negative externalities. These have the dual advantage of providing an incentive to reduce activities that cause social costs while generating revenues that could be spent on adaptation. For example, Germany has a rainwater tax that is charged based on the impermeable area of a property, thereby encouraging the use of nature-based solutions. Since 2012, French municipalities have also been allowed to apply a tax on soil sealing, which aims to limit soil artificialisation and encourage the use of permeable surfaces.6

Regulation and standards: to make sure project holders incorporate resilience issues into new investments. For example, the FAST-Infra Sustainable Infrastructure label encompasses climate resilience, as does the prototype certification framework for the Blue Dot Network. At the local level, for example, by revising urban planning, municipalities can limit new investments in flood-prone areas. Similarly, new building code standards can be set to increase spending in buildings and make them more resilient to weather events.

Risk transfer and insurance: the extent to which climate-related risks are held by the government creates incentives to invest in managing climate-related risks, and has distributional consequences. Reforms to provide transparency on risk ownerships can increase predictability and reduce moral hazard.

Governments can also act as catalysts for investment through innovative financial instruments such as blended finance instruments. The combination of low (perceived) return on investment and high risk remains a major barrier to private sector investment in most adaptation-related projects (The World Bank, 2021[6]). Mechanisms such as blended finance can include performance-based market incentives, provide technical assistance to project owners, and absorb some of the risk that investors incur through debt swaps or climate risk guarantees and insurance. By dedicating a small amount of domestic public funds or international multilateral funds, countries can remove investment barriers and raise large amounts of private capital for adaptation (OECD, 2021[9]).

In this regard, the strategic use of grant or concessional finance by multilateral development banks (MDBs) can be highly impactful. Institutional reforms in MDBs, including reducing shareholder expectations for return on equity and better targeting of performance indicators, can help to shift them from a role as sole financiers of projects towards a focus on mobilisation of broader financial flows and catalytic activities such as policy support and capacity development. In this manner, MDBs can help to create an enabling environment for the alignment of finance flows with climate-resilient development in developing countries (OECD, 2021[10]). This kind of catalytic activity can also be important for activities such as the greening of developing country financial systems.

Countries can also issue green bonds to finance specifically designated adaptation projects. Green bonds differ from regular bonds in their use, as they must only be used to finance "green" projects, which can be related to biodiversity, pollution, climate change mitigation, or adaptation (OECD, n.d.[11]). According to the Global Center on Adaptation, almost 1 300 green bonds (16% of all green bonds issued up to September 2020) included adaptation and resilience objectives (Global Center on Adaptation (GCA), 2021[12]). As an illustration of the growing need to finance adaptation, the first bond fully dedicated to climate resilience, was launched by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in 2019, raising USD 700 million. Although the value of green bonds issued increased four-fold between 2017 and 2021,7 they still represented less than 1% of all bonds issued in 2022.8

Governments should also lead by example by ensuring that resilience is mainstreamed in all public spending and investments, particularly given that many of the relevant investment needs are within the competence of public authorities. The aim of this is to ensure that there are sufficient resources to achieve an acceptable level of risk while also aligning public spending with the reality of mounting physical climate risks. Key tools for achieving this include mainstreaming into budget planning, budget tagging (to identify trends in spending), and reform of procurement policies (such as using life-cycle costing) to reflect the benefits of adaptation. For a more detailed discussion of aligning public budgets and procurement with climate policy objectives, see Chapter 5.

Beyond the role for governments, investors and investor coalitions themselves can drive progress by demanding adaptation-aligned investment opportunities. They can also articulate frameworks and minimum standards for what information they require from investees. For example, The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC) has released a set of investors’ expectations on the management of physical risks and opportunities (IIGCC, 2021[13]).

Progress to date on financing adaptation

Despite the clear case for aligning public and private financial flows with adaptation needs, the extent to which this is taking place remains unclear. Information about domestic public spending on adaptation remains scarce. Few OECD countries highlight adaptation spending in their National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) or Adaptation Communications. Among those that do, Austria has estimated its spending for adaptation to be EUR 480 million per year (Austria, 2021[14]). South Korea has tracked and reported past spending for specific adaptation activities, for example, spending USD 3.5 million on developing crop-specific impact assessments, but does not provide broader aggregate figures (South Korea, 2021[15]). Similarly, the extent to which private investment contributes to climate resilience is unknown. One estimate suggests that private sector spending for adaptation is less than USD 1 billion per year (Buchner et al., 2021[16]) while the World Bank suggests that private sector financing for adaptation may already be substantial (The World Bank, 2021[17]). The OECD estimates that official development finance mobilised USD 4.4 billion of private finance for adaptation in 2020 (OECD, 2023[18]).

Multilateral development banks have made significant commitments to financing adaptation in recent years. In December 2017, together with the International Development Finance Club (IDFC), MDBs announced their vision for aligning financial flows with the objectives of the Paris Agreement, with one building block being dedicated to adaptation and climate resilience (Mullan and Ranger, 2022[8]). In December 2018, MDBs again declared their commitment to actively manage physical climate risks and co-operate to catalyse low-emissions and climate-resilient development.9 As noted in Chapter 5, there have been calls for a reform of MDBs, including at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, to better enable their implementation of these goals.

Finance flows for adaptation are only comprehensively measured as part of International public finance. Here, recent estimates show that while mitigation finance still represents the majority of all climate funding in 2020 (58%), adaptation finance almost tripled between 2016 and 2020, mostly due to investment in a few big infrastructure projects (OECD, 2022[19]; OECD, 2022[20]).

To date, the amount of funding mobilised by OECD countries in response to extreme weather events is likely to be considerably higher than funding for ex ante adaptation measures. For example, the German federal government set up a EUR 30 billion reconstruction fund to help victims of the 2021 flood (Reuters, 2021[21]). Compared to this, the third German Adaptation Action Plan (APA III) only allocated EUR 420 million to flood protection measures for the period 2020-2025. In Japan, central government budget data for both ex ante and ex post disaster management expenditure has been annually published since 1980 and shows a clear trend in increased funding for post-disaster recovery and reconstruction. In Colombia, post-disaster spending has grown on average by 65.26% per year (1998-2008), while pre-disaster spending only increased by 22.08% over the same period (OECD, 2018[22]).

Part of the challenge in accurately measuring adaptation finance flows is that defining what constitutes adaptation finance remains complex. Adaptation is often integrated into broader investments: in some cases, there will be identifiable marginal costs (e.g. raising a bridge) related to adaptation, but in others, adaptation responses are harder to quantify as they may involve broad changes in the way a project is implemented (e.g. relocating a planned infrastructure asset). Appropriate adaptation responses are also context-specific, so the contribution of an investment to adaptation will depend on a variety of factors.

A precise definition of adaptation finance is open to debate, particularly in terms of whether to count the marginal cost of adaptation measures or the entire value of projects. Recognising the need to clarify what is meant by adaptation finance, many entities have created their own definitions (see OECD (2020[23]) for a recent review). One of the first attempts to define adaptation finance was the Rio Markers, developed by the OECD to track flows of international finance for adaptation (OECD, n.d.[24]). Development agencies use these markers to track how their investments are allocated to one or several environmental objectives, including adaptation. Multilateral development banks have also joined forces to set “Common Principles for Climate Change Adaptation Finance Tracking” (MDB Climate Finance Tracking Working Group and the IDFC Climate finance Working Group, 2018[25]). This classification is used to measure the share of total project cost that belongs to adaptation.

Other efforts seek to elicit the adaptation part of private investments, such as taxonomies relying on process and sector-based classification of adaptation activities. For example, the recently released EU Taxonomy10 and the Inter-American Development Bank’s (IADB’s) adaptation solutions taxonomy11 can be used to characterise private finance as participating in one or more climate finance objectives. These taxonomies aim to change investor behaviour by making it mandatory to report investments according to these classifications, with the ultimate aim of influencing finance flows.

Despite the lack of quantitative information on adaptation spending, a review of OECD countries’ NAPs, NASs and Adaptation Communications provides an insight into the importance that countries place on finance for effective adaptation to climate change. Financing is mentioned in almost all NAPs and several countries have dedicated sections to adaptation finance, while others identify adaptation finance as one of a small selection of top priorities for their adaptation strategies. Other initiatives have also been taken to enhance adaptation finance outside of the NAP process. For example, to support adaptation financing, Australia created a council of financial regulators to implement regulatory measures to help the financial sector better understand climate risk and address regulatory gaps undermining the consideration of climate risk.

There is growing interest in resilience issues within the financial sector itself as well, driven by the increasingly visible costs of climate-related extreme events and increasing financial opportunities offered by a changing climate. Several initiatives are underway to address this issue. For example, the recommendations and guidance issued by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) are supported by over 3 000 organisations worldwide, representing USD 27.2 trillion in assets under management. The Coalition for Climate Resilient Investment brings together 120 public- and private-sector members to help increase private- and public-sector spending on resilience.

Some sectors, notably insurance, already have long-established procedures for managing physical climate-related financial risks. However, the focus here has been primarily on managing current risks rather than projected future risks even though it is clear that climate impacts will increase even if mitigation targets are met. This is due to the short timescale upon which asset and investment decisions are made. In addition, damages from physical climate risks to date, at least in more advanced economies, have been moderate compared to other sources of financial risks (Mullan and Ranger, 2022[8]).

To effectively harness growing interest from the financial sector in aligning financial flows with adaptation needs, initiatives such as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria could play a considerable role, including by facilitating investment in resilient infrastructure. But such initiatives first need to overcome a number of issues. In particular, there needs to be measurement of financial flows and collection of data on how they align with adaptation efforts (Box 13.1). There is also the need to ensure financial sector commitments are implemented with integrity (see Chapter 9). Similarly, private sector-led adaptation efforts that align with responsible business conduct (RBC) guidelines can play an important role in enhancing climate resilience. They must first overcome challenges regarding the traceability of actions and accountability (see Chapter 9).

Box 13.1. Data for private investment in resilient infrastructure

One of the barriers to investment in resilient infrastructure is the lack of data. This data issue has been raised in various international discussions but, in particular, is reflected in Policy Message VII of the Outcome Document of 2021 G20 Infrastructure Investors Dialogue Financing Sustainable Infrastructure for the Recovery (October 2021). It calls to “[p]romote further consistency in data collection through improved methodologies and common terminologies, in particular in the ESG and new technologies area…”. Having more data available is intended to address the information asymmetry in infrastructure financing. This leads to greater certainty and clarity for investors when they consider investments in sustainable infrastructure.

However, data availability on resilient infrastructure still faces multiple challenges. First, there is a need to define infrastructure to harmonise basic data collection as there is currently no internationally recognised definition of infrastructure for these purposes. The OECD’s Working Party on National Accounts has developed an infrastructure definition to facilitate the data collection and comparison of statistics based on the System of National Accounts, which could be a useful starting point. A second challenge lies in defining what resilient infrastructure is. Despite extensive discussions on sustainable infrastructure to date, there is still no clear understanding of what it might constitute. The definition of sustainable infrastructure characteristics can be based on the many public and private sector initiatives on sustainable finance and infrastructure in recent years. A final challenge relates to the lack of availability of ESG data. While ESG-adjacent data exists, ESG-assessed data is not publicly available, and thus it is currently not possible to assess the performance of sustainable infrastructure. This lack of data is partly the result of the high cost of producing ESG data. Given the nature of infrastructure projects, infrastructure data is inherently expensive to produce and ESG data is even more resource-intensive. Greater implementation of existing sustainable infrastructure labels and the development of indicators could enable the dissemination of ESG data. Initiatives such as FAST-Infra, Blue Dot Network and the collection of QII indicators could contribute to and create a data repository for sustainable infrastructure in the future.

Source: OECD.

The role of the insurance sector in building resilience

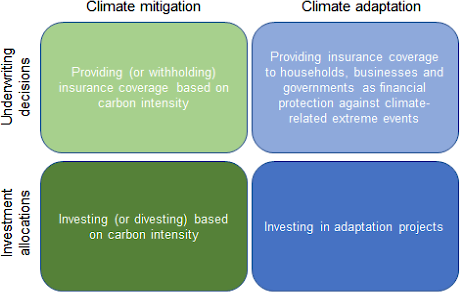

The insurance sector plays a particularly notable role in enhancing efforts to align financial flows with adaptation and resilience needs.12 While climate change poses physical and transition risks to the insurance sector, the sector can also significantly contribute to climate mitigation and adaptation through investment allocation and underwriting decisions (Figure 13.1).

In recent years, a number of international initiatives have been set up to support the sector in these efforts. These include the UN-convened Net-Zero Insurance Alliance, Insurance Development Forum, ClimateWise, the Sustainable Markets Initiative, the Munich Climate Insurance Initiative, the UN Principles for Sustainable Insurance, and the Global Shield against Climate Risks.13 In line with these trends, many (re)insurance companies have also taken steps to withdraw or reduce the coverage they provide to companies involved in coal and (to a lesser extent) other types of fossil fuel activities.14

Figure 13.1. Contribution of insurance to climate change mitigation and adaptation

Source: OECD.

Climate risks and the resilience of the insurance sector

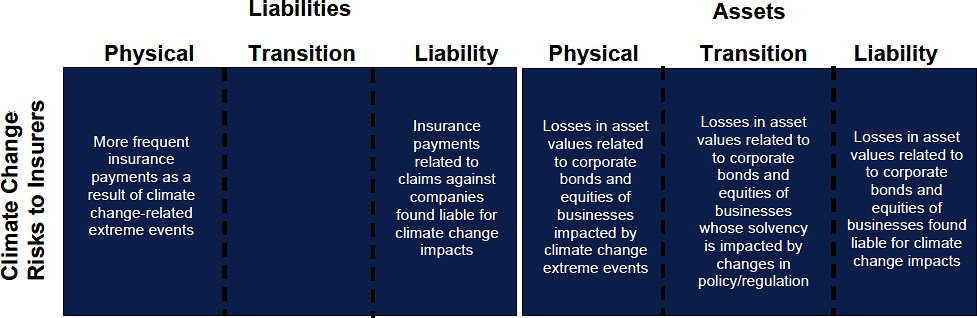

The physical, transition and liability risks of climate change pose significant risks to the insurance sector. These risks include those impacting insurers’ assets (i.e. investments held to fund obligations to policyholders) and liabilities (i.e. the obligations created by the insurance coverage provided to households and businesses15). The types of risks as they apply to both liabilities and assets are outlined in more detail below (Figure 13.2).

Figure 13.2. Principle climate change risks to (re)insurance companies

Source: OECD.

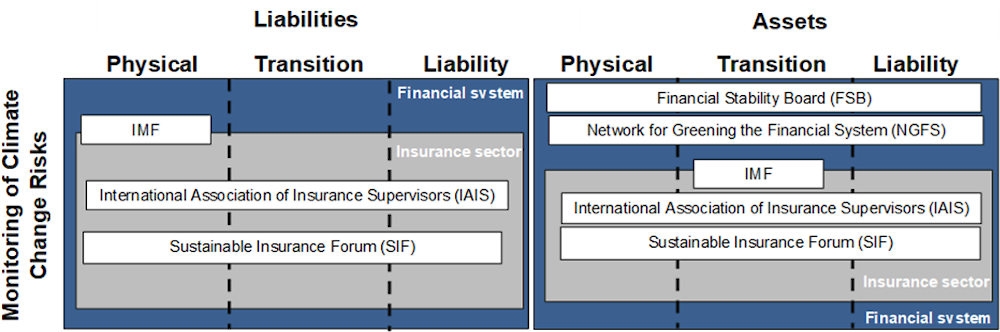

Monitoring these risks to insurance has been an important area of focus for international organisations, and individual regulatory and supervisory authorities overseeing risks to the insurance sector and broader financial system (Figure 13.3). International organisations and financial sector regulators are developing common tools (such as scenario analyses) to support the assessment of climate risks to insurance companies, with a particular focus on asset-related risks. The International Association of Insurance Supervisors has established a Climate Risk Steering Group with an initial focus on contributing to the development of scenario analysis and other supervisory tools for monitoring climate risks to the insurance sector. There have also been increasing efforts to collect data to assess liability risks for insurers as a result of the coverage they provide to households and businesses, although these risks have been more challenging to assess.16

Figure 13.3. Monitoring of climate change risks to the insurance sector and broader financial system

Source: OECD.

The level of financial protection provided by the insurance sector to other parts of the financial system (particularly banks) is also receiving increasing attention. For example, the Financial Stability Board’s recommendations for enhancing supervisory oversight of climate-related risks to the financial sector includes a need to enhance the monitoring of risk transfers between the banking and insurance sectors (Financial Stability Board, 2022[26]).

Insurance sector contributions to climate change adaptation

Insurance coverage for climate perils can play a critical role in absorbing the costs of future climate damages and losses, supporting economic recovery in the aftermath of climate disasters, and ultimately building resilience. However, in many developed and developing countries, the level of insurance coverage for climate and other disaster-related damages and losses is relatively low, meaning that households, businesses and governments ultimately absorb a significant share of these costs. Increasing damages and losses from more frequent and/or more severe climate disasters could limit the availability of affordable insurance in the future and lead to larger uninsured losses for households and businesses. This will be the case if the amount of premiums needed to be collected to cover higher losses leads to a cost of coverage that is beyond the willingness (or capacity) of households and businesses to pay (EIOPA, 2021[27]). In this way, supporting adaptation measures to reduce the overall risk of climate impacts will be the only sustainable means to limit the increase in future climate damages and losses, and prevent potential disruptions to the availability of affordable insurance coverage that could result. In a number of countries and/or regions, increasing losses from climate-related impacts has led to concerns about the availability of affordable insurance coverage, such as for cyclone-related wind and flood damage in Australia, wildfires in California (United States) and floods in Ireland (OECD, 2021[28]).

The Insurance and Private Pensions Committee has developed an analysis of the potential contributions the insurance sector could make to climate change adaptation and ways to enhance that contribution. The insurance sector can play a role by identifying assets at risk, and encouraging and investing in risk reduction and adaptation (as a complement to government investment in adaptation):

The insurance sector is at the forefront of developing sophisticated risk analytical tools such as catastrophe models. These tools can provide probabilistic estimates of the level of climate risk to homes, buildings and public assets in specific locations, taking into account individual building structural characteristics as well as any existing protections at the community level (e.g. flood barriers).

Leveraging its claims experience and risk analytics, the insurance sector can provide expertise to climate policy makers, individual policyholders and wider communities on adaptation and risk reduction measures that can provide effective protection against climate perils;

In applying premium pricing that reflects the level of risk at the level of individual policyholders, the insurance sector can provide an important risk signal and incentives for adaptation and risk reduction; and,

Through its role in funding (and sometimes managing) post-event reconstruction, the insurance sector can make an important contribution to supporting resilient reinstatement (also referred to as “build back better”).

However, in harnessing the full force of the insurance sector’s contribution to climate change adaptation, a number of regulatory, technical, business model and competitive constraints need to be considered. These include:

The sector’s ability to accurately quantify future climate risk based on analysis of hazard exposure and vulnerability. The accuracy of risk information and signals can be impacted by uncertainties related to the level of future emissions (and resulting climate conditions); the impact of climate change on future hazard frequency and severity; and future changes in exposure and vulnerability as a result of economic and population growth in areas at risk, and levels of investment in adaptation and risk reduction. In addition, the demand for future climate risk analytics may be constrained by the short-term nature of insurance contracts, leading to a focus on near-term rather than longer-term climate conditions.

While the insurance sector recognises the value of its risk management, risk reduction and adaptation expertise (and invests in sharing that knowledge with governments, communities and individual policyholders), the ability of the insurance sector to provide targeted advice – which could involve significant costs – is limited, particularly in the context of smaller insured risks (i.e. for which limited premiums are collected).

There is only limited evidence that providing information on risk, including advice and services to support risk reduction, leads to the implementation of adaptation measures by policyholders. However, this may be partly due to regulation that limits (possibly inadvertently) the ability of insurance companies in some countries to provide risk management services (e.g. home sensors and monitoring services that can detect and/or prevent water or fire damage) to policyholders because of legal restrictions on the involvement of insurance companies in non-insurance commercial activities. Rules may also exist in countries where unfair trading practices that could undermine premium pricing requirements are restricted.

Competitive factors, risk assessment capacity and regulation (in some countries) can impact the ability of insurance companies to charge premiums to individual policyholders that are truly reflective of the level of risk and therefore effectively incentivise risk reduction.17

In addition, risk-reflective pricing may not sufficiently incentivise policyholders to undertake costly risk reduction or adaptation measures when it would be in exchange for premium discounts that take many years to fully recoup the cost of the adaptation investment. Longer-term insurance coverage contracts could support better risk signalling and incentives, although they would lead to a significantly higher cost of premiums for policyholders and could be detrimental to market competition by impeding policyholders’ ability to change insurance providers.

While investing in risk reduction is usually most cost-effective during the reinstatement of a damaged property, insurance companies have little incentive to absorb the additional cost of resilience improvements – particularly where policyholders are free to seek coverage from a competitor who will then benefit from the resulting reduction in risk. Insurance companies are only obligated to repair an insured property to its pre-existing state and would have no way to ensure that any additional payments made to policyholders for betterment could be recouped through future premium earnings or reductions in future losses – as the policyholder could seek coverage from another insurance company.

Opportunities to enhance the role of the insurance sector

The underwriting and investment decisions of insurance companies – as providers of financial protection and significant portfolio investors (and, in some cases, as third-party asset managers) – can have important implications for driving climate resilience. This includes through the development of sophisticated risk analytical tools, leveraging the sector’s expertise in risk analytics and risk reduction measures, providing important risk signals and incentives, and contributing to resilient reinstatement efforts.

Although there are challenges to harnessing the full potential of these efforts, there are also a number of opportunities to enhance the sector’s contribution to adaptation, building on the above. These include the following:

While not the main objective of insurance supervision, enhancing regulatory and supervisory efforts to ensure that insurance companies are appropriately monitoring climate risks is incentivising the development of longer-term climate risk assessments. For example, the Bank of England’s 2021 Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario exercise required certain insurers to provide a quantitative assessment of the impact of climate on future losses which led to the development of risk analytics to help insurers meet this requirement (Clarke and Latchman, 2021[29]).

Policy and regulatory requirements that impede the provision of risk management and mitigation services, and the setting of risk-reflective premiums could be examined by governments to determine whether the benefits18 of these restrictions outweigh the costs of restricting the insurance sector’s role in advising on and incentivising risk reduction and adaptation19 (or whether other (or modified) approaches20 might be able to achieve these objectives while still contributing to climate adaptation). Insurance regulators or supervisors could encourage insurance companies to provide better and more targeted information on climate risk and potential adaptation investments that policyholders can make.

The insurance sector and government could provide more co-ordinated support for resilient reinstatement (i.e. rebuilding damaged property to be more resilient) – which is likely a more cost-effective approach to managing the financial impacts of climate risks than providing compensation for damages and losses after an event. Insurers could also be encouraged to make coverage available (at an additional cost) for resilient reinstatement.

Chapter conclusions

A primary reason for the insufficient progress made on building climate resilience is the clear lack of finance for adaptation efforts. While progress has been made on setting national and subnational adaptation objectives, no comprehensive assessment of the financing needs of meeting these objectives exists. Challenges in defining what counts as adaptation efforts, and then measuring these, confound this problem. Overcoming barriers to scaling up adaptation finance is not only a task for governments. Rather, financial markets and the private sector also have an important role to play, as with mitigation efforts. In particular, the insurance sector holds considerable promise for advancing progress on financing adaptation.

References

[30] ACPR (2021), A first assessment of financial risks stemming from climate change: The main results of the 2020 climate pilot exercise, Banque de France.

[14] Austria (2021), Austria’s Adaptation Communication.

[16] Buchner, B. et al. (2021), Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021.

[29] Clarke, A. and S. Latchman (2021), Helping Clients Respond to the Bank of England, AIR Worldwide, https://www.air-worldwide.com/blog/posts/2021/8/helping-clients-respond-to-the-bank-of-englands-2021-climate-biennial-exploratory-scenario/ (accessed on 11 June 2022).

[27] EIOPA (2021), Report on non-life underwriting and pricing in light of climate change, European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority.

[26] Financial Stability Board (2022), Supervisory and Regulatory Approaches to Climate-related Risks.

[12] Global Center on Adaptation (GCA) (2021), Green Bonds for Climate Resilience - State of Play and Roadmap to Scale.

[2] Global Commission on Adaptation (2019), Adapt Now: A Global Call for Leadership on Climate Resilience, https://gca.org/reports/adapt-now-a-global-call-for-leadership-on-climate-resilience/ (accessed on 25 January 2023).

[3] Hallegatte, S., J. Rentschler and J. Rozenberg (2019), Lifelines, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1430-3.

[13] IIGCC (2021), Building Resilience to a Changing Climate: Investor Expectations of Companies on Physical Climate Risks and Opportunities, https://www.iigcc.org/download/building-resilience-to-a-changing-climate-investor-expectations-of-companies-on-physical-climate-risks-and-opportunities/?wpdmdl=4902&refresh=645bfff23a70c1683750898.

[32] Insure Our Future (2022), 2022 Scorecard on Insurance, Fossil Fuels & Climate Change, Insure Our Future, https://global.insure-our-future.com/scorecard/.

[25] MDB Climate Finance Tracking Working Group and the IDFC Climate finance Working Group (2018), Lessons Learned from Three Years of Implementing the MDB-IDFC Common Principles for Climate Change Adaptation Finance Tracking, https://www.idfc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/mdb_idfc_lessonslearned-full-report.pdf.

[8] Mullan, M. and N. Ranger (2022), “Climate-resilient finance and investment: Framing paper”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 196, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/223ad3b9-en.

[5] NAP Global Network (2017), Financing National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Processes: Contributing to the achievement of nationally determined contribution (NDC) adaptation goals.

[1] Neumann, J. et al. (2021), “Climate effects on US infrastructure: the economics of adaptation for rail, roads, and coastal development”, Climatic Change, Vol. 167/3-4, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03179-w.

[18] OECD (2023), Private finance mobilised by official development finance interventions.

[19] OECD (2022), Aggregate Trends of Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2020, Climate Finance and the USD 100 Billion Goal, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d28f963c-en.

[20] OECD (2022), Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2016-2020: Insights from Disaggregated Analysis, Climate Finance and the USD 100 Billion Goal, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/286dae5d-en.

[7] OECD (2021), “Building resilience: New strategies for strengthening infrastructure resilience and maintenance”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 05, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/354aa2aa-en.

[28] OECD (2021), Enhancing Financial Protection Against Catastrophe Risks: The Role of Catastrophe Risk Insurance Programmes, OECD.

[10] OECD (2021), Investing in the climate transition: The role of development banks, development finance institutions and their shareholders.

[9] OECD (2021), The OECD DAC Blended Finance Guidance, Best Practices in Development Co-operation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ded656b4-en.

[23] OECD (2020), Developing Sustainable Finance Definitions and Taxonomies, Green Finance and Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/134a2dbe-en.

[22] OECD (2018), Assessing the Real Cost of Disasters: The Need for Better Evidence, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264298798-en.

[11] OECD (n.d.), Green bonds: Mobilising the debt capital markets for a low-carbon transition.

[24] OECD (n.d.), OECD DAC Rio Markers for Climate: Handbook, https://www.oecd.org/dac/environment-development/Revised%20climate%20marker%20handbook_FINAL.pdf.

[31] Prudential Regulation Authority (2022), Results of the 2021 Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario (CBES), Bank of England, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/stress-testing/2022/results-of-the-2021-climate-biennial-exploratory-scenario.

[21] Reuters (2021), German cabinet backs 30 bln euro flood recovery fund, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/german-cabinet-backs-30-bln-euro-flood-recovery-fund-2021-08-18/.

[15] South Korea (2021), 3rd National Climate Change Adaptation Measures (2021-2025) Detailed Implementation Plan.

[6] The World Bank (2021), Enabling Private Investment in Climate Adaptation and Resilience : Current Status, Barriers to Investment and Blueprint for Action.

[17] The World Bank (2021), Enabling Private Investment in Climate Adaptation and Resilience: Current Status, Barriers to Investment and Blueprint for Action.

[4] UNEP (2021), Adaptation Gap Report 2021 The Gathering Storm - Adapting to Climate Change in a Post-pandemic World.

Notes

← 1. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/publications_ext_content/ifc_external_publication_site/publications_listing_page/adapting-to-natural-disasters-in-africa?cid=IFC_LI_IFC_EN_EXT

← 4. https://france-renov.gouv.fr/aides/credit-impot#:~:text=Cette%20aide%20fiscale%20s'%C3%A9l%C3%A8ve,euros%20par%20personne%20%C3%A0%20charge

← 5. https://france-renov.gouv.fr/aides/credit-impot#:~:text=Cette%20aide%20fiscale%20s'%C3%A9l%C3%A8ve,euros%20par%20personne%20%C3%A0%20charge

← 7. https://www.climatebonds.net/market/data/

← 8. The Climate Bonds Initiative estimates the value of green bonds released in 2022 at around USD 1 trillion, while the International Capital Market Association estimates the value of global bonds at around USD 128 trillion. (https://www.icmagroup.org/market-practice-and-regulatory-policy/secondary-markets/bond-market-size/ ).

← 10. https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/tools-and-standards/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en

← 12. A global architecture for climate and disaster risk finance and insurance includes all financial instruments and corresponding institutional structures that can be used for the management and transfer of climate-related risks. Insurance solutions are a prominent example and thus the focus of this section. Besides insurance, risk financing also includes other instruments that can provide fast and reliable pay-outs in case of catastrophes, such as Contingent Credits, Contingency Reserves, or Credit Guarantees.

← 13. The UN-convened Net Zero Insurance Alliance is focused on encouraging low-carbon underwriting and investment decisions through a commitment by participants to achieve net-zero targets in underwriting and investment portfolios. The Insurance Development Forum (IDF) is focused on addressing climate-related financial protection gaps in developing countries. ClimateWise works to align underwriting and investment with climate goals. The Sustainable Markets Initiative (Insurance Task Force) focuses on both sustainability in underwriting and investment decisions, and addressing climate-related financial protection gaps in developing countries. The Munich Climate Insurance Initiative aims to support climate resilience in developing countries through the implementation of climate insurance solutions. UN-convened Principles for Sustainable Insurance encourages sustainable underwriting and investment (including from a climate change perspective) through a commitment by participants to adhere to sustainable underwriting and investment principles. The Global Shield against Climate Risks is a joint initiative of the G7 and the Vulnerable Twenty Group of Finance Ministers (V20), which was officially launched at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh in 2022. The Global Shield will support instruments designed to strengthen resilience and provide rapid financial assistance when a climate-related disaster has impacted vulnerable communities. This includes various financial protection instruments such as social protection systems or insurance schemes tailored towards the needs of the country.

← 14. According to Insure our Future, an international campaign aimed at encouraging insurer exit from underwriting coal, and oil and gas activities, approximately 41 (re)insurers have placed restriction on providing coverage for the coal sector (representing 39.3% of the primary insurance market and 62.1% of the reinsurance market) while 13 (re)insurers have placed restrictions on providing coverage for the oil and gas sector (Insure Our Future, 2022[32]).

← 15. For example, a changing climate is expected to increase the frequency and/or intensity of a range of climate-related perils, including floods, storms and cyclones, wildfires and droughts. More frequent or more intense climate-related disasters – as well as continued development in hazard-prone locations – will lead to increasing damages to homes, businesses and public assets, and losses as a result of disrupted livelihoods and business interruption. To the extent that these losses are insured, insurance companies will face increasing losses as a result of the claims they pay.

← 16. A few individual insurance supervisors (e.g. France, United Kingdom) have undertaken stress tests or other types of analyses of the impact of climate change physical risks on insurance liabilities (see: (ACPR, 2021[30]) (Prudential Regulation Authority, 2022[31]).

← 17. In some countries, premium pricing is subject to a simplified pricing framework due to the existence of a catastrophe risk insurance programme that pools risks into a mandated pricing framework that requires that only certain criteria are considered in price-setting, thereby reducing the extent to which premiums fully reflect the level of underlying risk.

← 18. These types of restrictions are most often imposed in order to protect consumers, ensure broad affordable coverage or support competitive markets.

← 19. While risk-based pricing – and particularly the offer of premium discounts – should encourage policyholders to invest in risk reduction, there is mixed evidence on whether advice on risk reduction options and incentives through premium pricing are effective in leading to policyholder risk reduction investment. There are a number of other challenges that might impede policyholder risk reduction action, including the high cost of risk reduction measures relative to the potential benefits in terms of reduced premiums (among other challenges).

← 20. For example, in jurisdictions where risk-based pricing is limited by rating approval requirements or the presence of catastrophe risk insurance programmes that apply flat (or relatively flat) pricing frameworks, policyholders could be provided with information on what the risk-based (actuarial-based) premium would be if there were no impediments to risk-based pricing. This would at least provide a price signal to the policyholder related to the level of risk that they face even if the actual premium paid may not provide a significant incentive for risk reduction (a shift towards greater risk-based pricing would be more effective in creating such incentives). It could also provide a signal to governments on where risk reduction or adaptation investments should be made (for example, if households in a specific community are facing unsustainable levels of current or future risk).