Climate change is not the only crisis governments face. Events of recent years have highlighted how global socio-economic shocks can severely change the landscape for climate policy implementation. This chapter reviews evidence on COVID-19 recovery spending and efforts taken to address the socio-economic consequences of Russia’s war on Ukraine, assessing associated challenges and opportunities for the net-zero transition.

Net Zero+

3. Unpredictable and overlapping global crises: risks and opportunities for climate policy

Abstract

This chapter draws on work carried out under the Environment Policy Committee (the Green Recovery Database) and the Committee on Industry, Innovation and Entrepreneurship (forthcoming work on innovation and recovery), as well as a background paper prepared for the OECD Round Table on Sustainable Development.

Global events of recent years have highlighted how global socio-economic shocks can dramatically change the landscape for climate policy implementation, even as evidence of the severity of the climate emergency continues to mount. The COVID-19 pandemic, the lingering measures taken to contain it, and stimulus packages aimed at launching economic recovery continue to have profound implications for climate policy globally. The impacts of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine have exacerbated these pressures and come with their own climate policy implications. Such crises highlight the need to ensure the resilience of the net-zero transition in the face of shocks, while also seizing opportunities to accelerate climate ambition and build resilience to climate impacts.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences for climate policy

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed major challenges and offered numerous opportunities for global climate action. Lockdown measures initially enacted to limit the spread of the virus temporarily pushed down global emissions trajectories but emissions have since rebounded to their highest-ever levels as economies recover. With some exceptions, supply chains proved to be resilient during the initial waves of the pandemic, but rapid economic recovery in some parts of the world coupled with ongoing virus restrictions elsewhere – particularly in major manufacturing regions – led to supply-chain bottlenecks. This raised commodity prices and exerted inflationary pressures, unsettling economies worldwide even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

As the virus became more manageable, government spending switched from emergency rescue measures to recovery plans. These aimed to restart economies in the near term while building resilience to future shocks, emphasising an opportunity to “build back better”. The immense scale of these recovery packages enables government support for restructuring economies in line with net-zero trajectories. At the same time, recovery stimulus spending has helped spur demand and broad inflationary pressures. Recovery spending in the wake of the war in Ukraine also has an important role to play in improving energy security and diversifying the energy mix.

The following section reviews the most recent evidence from the OECD Green Recovery Database1 and Low-Carbon Technology Recovery Database to assess what lessons can be drawn from COVID-19 recovery spending as governments turn from stimulus measures towards regular policy making.

Does COVID-19 recovery spending align with climate ambitions?

The OECD Green Recovery Database collects and tracks information on measures related to COVID-19 recovery for which a clear positive or negative environmental impact can be identified. It includes new measures specifically targeting COVID-19 recovery and prior measures that were enhanced, accelerated or extended as part of recovery plans. At its last update in 2022, the database contained 1832 measures from 44 countries and the European Union (OECD, 2022[1]).

The most recent data show that green or environmentally friendly spending increased into 2022, from USD 677 billion in September 2021 to USD 1 090 billion in April 2022, amounting to 33% of total recovery spending (up from 21% in 2021). Spending with “mixed” and “negative” impacts on the environment also increased, though to a lesser extent, accounting for only 14% of recovery spending. The remaining half of recovery spending was not found to have a direct environmental impact (OECD, 2022[1]). These estimates are supported by other recovery trackers developed separately, such as the International Energy Agency (IEA) Sustainable Recovery Tracker and the Oxford Global Recovery Observatory (O’Callaghan et al., 2021[2]).

The increase in greener spending linked to COVID-19 recovery does not account for other government expenditure with environmental implications. According to pre-COVID-19 estimates, environmentally harmful government support together annually amounted to more than USD 680 billion globally,2 including subsidies for fossil fuel production and consumption3 and potentially environmentally harmful agricultural practices (OECD, 2022[1]; OECD, 2021[3]). Although not directly comparable, these numbers indicate that in just over two years, harmful support measures were similar in magnitude to the total amount of green recovery spending identified in the database (which itself accounts for more than 90% of total global economic stimulus packages adopted in response to the pandemic). As recovery packages will be spent over multiple years, these estimates highlight the stark climate implications of policies intended to shield households and affected sectors from high-energy prices in the wake of crises such as COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine. Careful consideration is needed to ensure energy affordability for those in need without derailing climate-policy ambitions.

Although 20% of measures cover all economic sectors, most recovery measures in the database target specific sectors. Energy and ground transport are the most targeted sectors, receiving 26% and 21% of recovery spending with environmental implications respectively (OECD, 2022[1]).

A key gap in recovery efforts is the lack of spending targeting innovation and skills development. Only 8% of measures focus on promoting research and development (R&D), and 2% on job skills upgrades (OECD, 2022[1]). Innovation and skills development are key components of an accelerated transition to net zero while also providing key economic stimulus to help withstand shocks. This is clearly reflected in the fact that the few R&D measures identified in the database almost all have a positive impact on the environment. Although recovery efforts only provide a partial picture of overall green innovation support by governments, this gap nonetheless warrants further exploration.

Building on the OECD Green Recovery Database and the Oxford University Global Recovery Observatory database, the OECD Low Carbon Technology Recovery Database (LTRD) assesses the impact of recovery spending specifically on low-carbon technologies across 51 countries (members of the OECD, the European Union and G20). These collectively represent 89% of global GDP and 79% of global annual CO2 emissions. In total, 1149 measures involving government spending toward low-carbon technologies have been identified, amounting to USD 1.3 trillion. This includes measures that are not considered in the most recent data in the Green Recovery Database such as the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which was initially announced in 2021 as the Build Back Better Act but was then amended and finally passed into law as the IRA in August 2022. The IRA adds an additional USD 412 billion to overall recovery spending (accounting for almost 50% of green recovery spending covered by the Green Recovery Database).

The vast majority of technology-related recovery spending is focused on scaling up existing technologies. Compared to the recovery packages following the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, the response to the COVID-19 crisis appears to have placed more emphasis on R&D and demonstration. Among measures for which the innovation stage could be determined, roughly 5% of total green recovery funding was channelled towards support for R&D (2.5%) and demonstration projects (2.8%). An additional USD 34 billion (2.5% of low-carbon recovery spending), while not specifically mentioning R&D or demonstration, is channelled at technologies at the pre-adoption stage based on their Technology Readiness Level (TRL). In total therefore, around 8% of recovery funding targets pre-commercialisation phases, and 92% adoption and deployment phases, again with significant country differences (Aulie et al., Forthcoming 2023[4]). This appears to be a very significant contribution to closing the USD 90 billion funding gap in R&D and demonstration until 2030 highlighted by the IEA Net Zero Emissions Scenario.

Nine percent of low-carbon technology recovery funding is specifically dedicated to supporting emerging technologies with a clear priority on hydrogen, and to a lesser extent on carbon capture and storage, smart grids, zero-emission buildings and advanced batteries. Again, the regional prioritisations here differ, where hydrogen has been the main priority in many EU countries (including France, Germany and Belgium), New Zealand and the United Kingdom, while CCUS received priority in Norway, Australia and Denmark. Smart grid technology played an important role in Hungary, Estonia, Italy, Korea and Canada, while low-emission buildings dominate in Korea. In contrast to other countries, the United States manage to spread efforts across several emerging technologies, including hydrogen, CCUS, smart grid, nuclear innovation and advanced batteries (Aulie et al., Forthcoming 2023[4]).

How does this technology spending compare to investment needed to reach carbon neutrality? The IEA estimates that USD 3.3 trillion and USD 4.2 trillion would need to be invested in clean energy annually by 2030, in the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) and the Net Zero Emission 2050 Scenario (NZE), respectively. Existing policies are expected to induce USD 2 trillion of annual investments by 2030 (IEA Stated Policies scenario), implying that USD 1.3 trillion and USD 2.2 trillion is needed in additional annual investments by 2030 to achieve the SDS and NZE scenarios, respectively, including both private and public financing. As such, total recovery funding targeting low-carbon technologies equals about the additional annual investments needed to reach net zero, keeping in mind that recovery spending is one off and will be spent over multiple years. This implies that, while recovery spending makes a welcome contribution to closing the carbon neutrality investment gap, it falls short of being on track to meeting net zero needs. It is also important to note that projections of additional annual investment needs include both public and private sector investments. The public sector (including recovery spending) is only anticipated to directly contribute 30% of the necessary finance for meeting net zero globally (Vivid Economics, UNFCCC Race to Zero campaign and the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, 2021[5]). Assessing the capacity for recovery spending on low-carbon technologies, and indeed other public technology finance, to crowd-in private investment is therefore paramount.

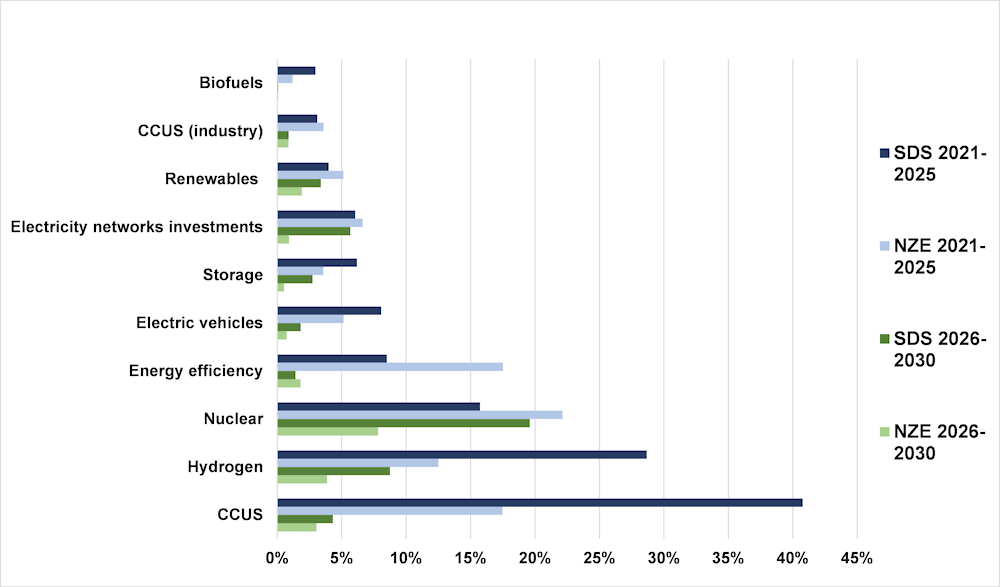

The role of recovery spending in making up the investment gap differs across technology groups, time periods and scenarios (Figure 3.1). Between 2021 and 2025, low-carbon recovery spending makes a significant contribution to global investment needs projected by the Sustainable Development scenario and the Net Zero scenario for CCUS (over 40% of average needs in the SDS scenario), hydrogen-based fuels (30% of investment needs) and, to a lesser extent, nuclear energy and energy efficiency (between 10% and 20% of investment needs). The contribution of recovery spending to investment needs in electric vehicles, energy storage, electricity networks and renewables is significantly smaller at about 5%-7%, and marginal in biofuels and CCUS for industry specifically. Therefore, while recovery packages make a significant contribution – in particular for CCUS, nuclear, energy efficiency and hydrogen – they fall short of filling the potential annual average investment gap towards 2030 to be on track with net-zero targets (Aulie et al., Forthcoming 2023[4]).

Figure 3.1. Annual average low-carbon recovery spending in selected technologies as a share of annual investment needs in IEA scenarios, 2021-2025 and 2026-2030

Note: Some of the technologies are summed across sectors, such as energy efficiency (from buildings and industry) and renewables (industry and power generation/fuel supply) and hydrogen (industry, fuel supply (clean fuels) and transport).

Source: OECD Low-carbon Technology Recovery database (version March 2023); IEA.

Lessons on net-zero spending for governments

COVID-19 recovery spending offered a clear opportunity to channel investment towards the net zero transition and climate action more broadly. Although spending has become increasingly green over time, clear gaps remain, with a substantial number of measures entailing a negative environmental impact, and the green portion of total recovery spending only at one-third.

As governments move from one-off recovery spending to annual budget policies, it is important to ensure that support measures intended to shield vulnerable households from high-energy prices do not work against green spending.

While post-COVID-19 stimulus packages have oriented investment towards sectors and key technologies key for a low-carbon transition, they cannot by themselves close the investment gap needed by 2030. They must now be accompanied by more ambitious complementary climate policies that would induce private investment and trigger the deeper structural changes made necessary by net-zero targets and the current fossil-fuel energy price crisis.

The impact of COVID-19 on global supply chains and investment

The COVID-19 pandemic placed unprecedented stress on global supply chains. International logistics constraints, supply shocks due to bottlenecks in labour markets, trade and transport, manufacturing, and food systems, and radically shifting demand and consumption patterns worldwide were all disruption factors (OECD, 2020[6]; OECD, 2022[7]; OECD, 2020[8]; Brenton, Ferrantino and Maliszewska, 2022[9]). These stresses also have implications for the net-zero transition, particularly as they restrict the flow of critical minerals for low-carbon technologies and the diffusion of low-carbon goods themselves. Key technology deployment such as solar photovoltaic (PV) installations suffered a considerable dip during the pandemic because of supply-chain bottlenecks and local mobility restrictions (OECD, 2020[8]; Goldthau and Hughes, 2020[10]).

Government responses to the pandemic have often hinted at increasing trade protectionism. Recovery strategies aim to shore up domestic production and manufacturing in order to stimulate national job creation and growth. Although increasing supply chain resilience is a key policy priority, particularly in the wake of the war in Ukraine (see below), protectionism could jeopardise the global trade and investment networks that brought down low-carbon technology costs in the past decade (Goldthau and Hughes, 2020[10]). To ensure resilience, governments must build an enabling environment for domestic industries while continuing to reap the benefits of international trade and investment, including diversification (OECD, 2022[7]).

Supply chain stresses in food systems highlight the importance of an open and predictable international trade environment to ensure continued access to key goods (OECD, 2020[6]). Rather than shortages, accessibility (including trade barriers and concerns around affordability) has been the primary stressor in food systems. This underlines the need for safety nets (e.g. stockpiling) to safeguard short-term accessibility in times of shock or crisis. A similar lesson can be drawn for the resilience of low-carbon supply chains: i.e. maintain international trade openness to drive continued long-term cost decreases and innovation while also diversifying supply chains and maintaining necessary domestic safety nets (e.g. stockpiling key minerals and other inputs to low-carbon production).

In addition to supply-chain bottlenecks and the threat of protectionist response policies, government stimulus spending has contributed substantially to global demand surges and associated inflation. This has been exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. While it remains difficult to untangle the exact extent of COVID-19 recovery stimulus in driving inflation, the resulting high investment costs are a clear obstacle to accelerated and resilient climate action (for more detail on this see Chapter 5). Governments will need to carefully target recovery efforts following future shocks to minimise inflationary pressures.

Implications of the war in Ukraine for climate policy

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has had far-reaching consequences well beyond the severe suffering in Ukraine itself. Impacts on global energy and food markets, as well as the broader economic situation, have created serious short-term challenges with implications for longer-term policy, including climate change policy. This section considers policy responses taken in the first six months following the invasion of Ukraine, with a focus on the implications of energy and macroeconomic policies for the transition to net-zero emissions. The section draws on a background paper prepared for the October 2022 meeting of the OECD Round Table on Sustainable Development.4

Energy supply disruptions due to the war in Ukraine have spurred a strong political focus on energy security that could in fact accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels, especially as renewable electricity sources become competitive with thermal power generation. However, near-term policy responses, including those aimed at managing high energy prices and costs of living, risk running counter to the transition. Governments need to ensure that necessary short-term deviations from net-zero paths do not lock in carbon for decades ahead.

The reduction in energy supplies from Russia and Ukraine due to sanctions and war-related supply disruptions initially led to sudden and sharp increases in energy prices. In mid-2022, European gas prices rose to about ten times their average over the previous five years. Although prices have since fallen due to successful campaigns to fill gas storage facilities, efforts to reduce energy demand, and a relatively mild winter in Europe, it is likely that price pressures will remain for several quarters ahead given Europe’s constraints in accessing alternative sources of gas supply. Global food prices also surged by nearly 20% in the months following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine due to war-related disruptions and concerns about possible impacts on global markets. These have since eased (FAO, 2022[11]).

These price increases have been responsible for the majority of the increase in headline inflation rates, reaching levels not seen in most countries since the two great oil shocks of the 1970s and inflation spike in 1988. Annualised consumer price index (CPI) inflation in OECD countries was over 10% in July 2022, its highest in over three decades. Higher energy prices, together with restrictions on energy supplies, are bearing down on the level of activity of many economies and the world as a whole. The OECD’s March 2023 interim economic outlook showed that global GDP growth was down to 3.2% in 2022 with a further fall to 2.6% projected for 2023 with a distinct change of a recession – a marked slowdown relative to expectations prior to the war – with a distinct chance of a recession (OECD, 2023[12]).

Energy and macroeconomic policy responses

Widespread sanctions have been imposed on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine. In parallel, many countries have taken urgent steps to develop new or modified energy policies. Some of these are well aligned with climate goals, such as focusing on demand-side policies to encourage or enforce reduced demand and ramping up clean energy deployment through enhanced support programmes and streamlined planning processes. Others are less so, such as a push for new investment in liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and pipelines, and turning to fossil-based thermal power generation.

On the macroeconomic side, central banks have consistently been raising interest rates to prevent initial inflation due to higher energy and food prices from triggering a generalised price/wage spiral. Monetary policy has been tightening in most advanced economies and in a majority of emerging market economies. Until very recently, fiscal policy was also being tightened in most countries, following the large fiscal expansions of the COVID-19 stimulus policies discussed above. Measures of discretionary fiscal policy (as measured by changes in the cyclically adjusted budget position) indicate that, in 2021, G7 economies were set to tighten their collective fiscal position by a substantial 5.2% of GDP, largely driven by the magnitude of the change in the United States.

Since mid-2022, however, the situation has changed quickly and dramatically. Several countries, including across the EU and the UK, have introduced policies to offset a significant part of the effect of higher energy prices on household users and, in many cases, industry. By late 2022, the European package was some 2.2% of EU GDP, and larger still in the UK and Germany as a proportion of GDP, with the total across the EU and UK estimated at EUR 500 billion.

Changing political circumstances

In recent years, climate change policies have become increasingly interrelated with social and political considerations. For example, regions dependent on fossil fuel production are concerned not only about job insecurity but also the distributional impacts of climate policies on lower income groups. Such distributional effects have been brought into sharp focus following the rise in energy prices due to the war in Ukraine. The impacts of higher costs of living are unequally distributed (Blake and Bulman, 2022), disproportionately impacting people on low incomes – especially with respect to household energy use – leading to significant pockets of poverty in many OECD countries and grave poverty in parts of the non-OECD world. Policies are being put in place to protect the poorest in many societies from increases in costs of living they could not otherwise bear, but the design of these measures matters greatly, as discussed below.

Such measures are being taken in an increasingly fractured international political environment. Beyond the breakdown of relations between most OECD countries and Russia, the war in Ukraine has stoked tensions with other non-OECD countries, including over sanctions. These tensions are affecting collaboration on climate change and clean energy, including through the UNFCCC process. This was apparent at COP27 in 2022, where significant progress on accelerating the transition to net zero was mostly lacking, though notable progress was made on adaptation finance and through the establishment of a “loss and damage” fund.

Better aligning near-term policy responses with the climate challenge

Some macroeconomic and energy-related policies enacted in response to near-term developments resulting from the war in Ukraine are indeed consistent with longer-term energy and macroeconomic aims. In other cases, however, there are important inconsistencies between evolving near-term and long-term objectives. This includes the risk of locking in fossil fuel infrastructure that could last decades, running counter to needed net-zero pathways, or creating stranded assets if forced into early retirement.

Energy policies broadly aligned with net zero

Many energy policies implemented since the beginning of the war in Ukraine have been well-aligned. Despite the current crisis, most countries have not backtracked on their overall climate goals and ambitions. Many have stated aims to progressively phase out fossil fuels and accelerate the transition towards clean energy while promoting and supporting energy efficiency. Moreover, the war in Ukraine has increased the desire of many countries to reduce dependency on imported fossil fuels and spur development of home-grown clean energy supply chains. A key example is the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which contains a range of measures and incentives designed to reduce the demand for energy and increase its supply from renewable sources. Faced with the consequences of Russia’s war on Ukraine, many near-term energy policies seek to accelerate the penetration of renewables, energy efficiency and other clean-energy technologies, thereby broadly aligning with longer-term energy goals.

On the energy supply side, cases of policy changes that are broadly aligned with long-term goals include accelerating the scaling-up of renewable electricity by supporting deployment of mature technologies; ramping up investment in energy innovation; and deployment of new technologies during the early stage of their development. Ramped-up policies for clean energy have also been oriented towards supporting new infrastructure, in particular power networks, storage, hydrogen, and initiating and accelerating new nuclear power programmes. Energy-supply policies also require a speeding-up of enabling regulation, pricing, planning, and investment. Time-consuming legal processes are often cited as a major obstacle to rapid deployment of renewables (McWilliams et al., 2022[13]). In response, the EU and the UK, for example, have recently announced plans to simplify their permission policies on rooftop PV in order to promote self-consumption (Climate Action Tracker, 2022[14]). Likewise, the German government has initiated major reforms aimed at the expansion of solar and wind, pledging to make additional sites available for renewable energy projects and to remove bureaucratic barriers in order to accelerate planning and approval processes (McWilliams et al., 2022[13]).

Energy policies not aligned with net zero

While a number of recent energy policies are broadly consistent with longer-term energy aims, there are a number of initiatives whose perceived near-term imperatives are not aligned with, and may even impede, longer-term net-zero objectives.

On the energy supply side, this includes cases where efforts to diversify from Russian fossil fuels has led investment in supply and infrastructure of other fossil fuels. It is important that governments take necessary steps to ensure that measures taken to ease immediate, urgent supply concerns are genuinely temporary and do not lock in supply over the longer term. There are plans for new LNG terminals in Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, and Greece, which, if they all come on stream, could significantly increase Europe’s LNG import capacity (Financial Times, 2022[15]).

Given development lead-times, this Europe-wide rush to build new LNG import terminals will not deliver instantly and risks prolonging reliance on fossil fuel energy supply beyond what is feasible for a net-zero emissions trajectory. It also increases the risk of creating stranded assets should demand for gas fall away before the expected lifetimes of terminals as the net-zero transition gathers pace. In addition, the overall cost of imported LNG will need to cover more than regasification and storage infrastructure in importing countries: it must reflect the need for more expensive infrastructure upgrades to LNG terminals in exporting countries. As accountability for net-zero commitments intensifies, costing of the climate change implications of methane leaks in the supply chain must also be taken into account.

In the near term, meeting energy demands will require recommissioning, extending the life of, or even investing in additional capacity in thermal fossil fuel plants, with the risk of locking in exposure to future risks of energy unaffordability and insecurity, and of growing damage from local air pollution and climate change. This effect was strong in mid-2022 due to it being a poor year for hydropower (due to droughts) and nuclear (due to heatwaves and extensive maintenance outages in France). Examples of thermal revival include Germany, which is delaying the closure of some coal- and oil-fired power plants, and Austria, where a retired coal power station is being renewed. The Netherlands is lifting its limit on power from coal, and France is preparing a coal plant as a reserve for the winter. While the immediate emissions impact of coal recommissioning in Europe may not be significant, it is important that their operation remains temporary (Ember, 2022[16]).

Further risk of locking in high carbon production comes from the granting of new exploration rights or permits, and initiating and accelerating new domestic oil and gas production infrastructure. The United States overturned the Biden administration’s 2021 pledge to suspend new leases for oil and gas companies by allowing oil and gas drilling to resume on federal lands as part of the Inflation Reduction Act (Reuters, 2022[17]). The UK is also looking to expand licencing of North Sea oil and gas fields.

On the demand side, policies to reduce consumer energy costs in the near term (e.g. price caps, non targeted reductions in excise duty, or policies that reintroduce fossil-fuel subsidies) may encourage longer-term fossil-fuel energy use. The design of such measures is important to ensure that they reach those who most need them and that they are aligned with longer-term climate goals. OECD analysis shows that measures need to be targeted, and that measures designed around income support are preferable to those focusing on price support: their fiscal cost tends to be lower, and they also better preserve incentives to reduce energy demand (OECD, 2022[18]). However, recent data show that policies implemented to date have mostly been untargeted price-support measures (OECD, 2022[18]).

In addition, reduced support for renewable energy investment funded through energy bills may curtail funds for the deployment of low-carbon technologies and systems. For example, the UK temporarily scrapped the “green levy” that typically accounted for around 8% of household energy bills (FT Adviser, 2022[19]).

Alignment of macroeconomic policies with climate goals

Concerted action by central banks to raise official interest rates is important to contain inflation in the near term, but also to ensure the medium-term economic stability necessary for investment. However, higher rates do not necessarily align with the longer-term aim of promoting the strong investment needed for the net zero transition and sustainable economic growth. This is important, as some clean energy technologies are likely to remain vulnerable to higher nominal interest rates for a period. These technologies tend to be capital-intensive with their full profit potential yet to be realised, meaning that future benefits are discounted more highly and carry less weight when assessing the business case. They are therefore more vulnerable to higher costs of capital. Other less mature sectors, including green hydrogen, clean steel, cement, and clean aviation and shipping, while offering enormous potential, are not yet sufficiently cost-effective to be scaled up without substantial policy support, in particular in a higher-cost-of-capital environment. The implications of this are further discussed in Chapter 5.

The implications of the income- and price-support measures to partly shield households and firms from high energy and other prices can also run counter to longer-term aims of reducing public deficits and transitioning away from fossil fuels and increasing energy security. Similarly, near-term actions by fiscal authorities to provide income support to sections of society hardest hit by rising energy and food prices do not necessarily align with longer-run concerns to contain the size of the public debt. In any case, enhanced perception of limited fiscal space is likely to limit public resources available to promote and deploy clean infrastructure.

Chapter conclusions

Disruptions such as a pandemic or war have the potential to derail efforts on climate policy. In particular, COVID-19 recovery spending and efforts to protect populations from the social and economic consequences of the war against Ukraine are not always aligned with climate policies. Beyond the immediate policy alignments and misalignments highlighted in this chapter, these two crises have laid bare the potential for such disruptions to derail efforts on climate policy and the need to design policies that not only accelerate the transition to net-zero emissions but focus on the resilience of the transition itself when faced with unpredictable disruptions and shocks.

The policy implications of the COVID-19 pandemic and war against Ukraine cannot be seen in isolation from other global events of recent years, going back to the financial crisis of 2008. They are also occurring in the context of global “mega-trends” such as a rapidly changing labour market, ageing societies, digital transformation of economies and, of course, environmental impacts related to climate change, biodiversity loss, degrading ocean health, and the potential for tipping points within these, all of which will come with their own challenges and opportunities.

With this broader perspective, it is clear that climate policy efforts need to be married to efforts to ensure economic resilience in order to remain durable over the long term.

References

[20] Aulie, F. et al. (2022), Will post-COVID-19 recovery packages accelerate low-carbon innovation?, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/2022GGGSD-IssueNote2-Will-post-COVID-19-recovery-packages-accelerate-low-carbon-innovation.pdf.

[4] Aulie, F. et al. (Forthcoming 2023), Did covid-19 accelerate the green transition? An assessment of public investments in low-carbon technologies., OECD, https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/2022GGGSD-IssueNote2-Will-post-COVID-19-recovery-packages-accelerate-low-carbon-innovation.pdf.

[9] Brenton, P., M. Ferrantino and M. Maliszewska (2022), Reshaping Global Value Chains in Light of COVID-19 : Implications for Trade and Poverty Reduction in Developing Countries, World Bank, http://hdl.handle.net/10986/37032.

[14] Climate Action Tracker (2022), Global reaction to energy crisis risks zero carbon transition: Analysis of government responses to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, https://climateactiontracker.org/publications/global-reaction-to-energy-crisis-risks-zero-carbon-transition/.

[16] Ember (2022), Coal is not making a comeback: Europe plans limited increase, https://emberclimate.org/insights/research/coal-is-not-making-a-comeback/.

[11] FAO (2022), FAO Food Price Index, https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/foodpricesindex/en/.

[15] Financial Times (2022), Europe’s new dirty energy: The ‘unavoidable evil’ of wartime fossil fuels, https://www.ft.com/content/b209933f-df7f-49ae-8f82-edc32ed622a6.

[19] FT Adviser (2022), Energy bill support package not long-term thinking, advisers say, https://www.ftadviser.com/your-industry/2022/09/12/energy-bill-support-package-not-longterm-thinking-advisers-say/.

[10] Goldthau, A. and L. Hughes (2020), “Protect global supply chains for low-carbon technologies”, Nature, Vol. 585/7823, pp. 28-30, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02499-8.

[21] IEA (2022), Global Energy and Climate Model, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-and-climate-model.

[13] McWilliams, B. et al. (2022), “A grand bargain to steer through the European Union’s energy crisis”, Bruegel Policy Contribution 14, https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/PC%2014%202022_0.pdf.

[2] O’Callaghan, B. et al. (2021), Global Recovery Observatory, https://recovery.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/tracking/.

[12] OECD (2023), OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2023: A Fragile Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d14d49eb-en.

[22] OECD (2022), Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2022: Reforming Agricultural Policies for Climate Change Mitigation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7f4542bf-en.

[1] OECD (2022), “Assessing environmental impact of measures in the OECD Green Recovery Database”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3f7e2670-en.

[7] OECD (2022), “International trade during the COVID-19 pandemic: Big shifts and uncertainty”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d1131663-en.

[18] OECD (2022), “Why governments should target support amidst high energy prices”, OECD Policy Responses on the Impacts of the War in Ukraine, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/40f44f78-en.

[3] OECD (2021), Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2021: Addressing the Challenges Facing Food Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2d810e01-en.

[23] OECD (2021), OECD Companion to the Inventory of Support Measures for Fossil Fuels 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e670c620-en.

[8] OECD (2020), “COVID-19 and the low-carbon transition: Impacts and possible policy responses”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/749738fc-en.

[6] OECD (2020), “Food Supply Chains and COVID-19: Impacts and Policy Lessons”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/71b57aea-en.

[24] OECD and IEA (2021), Update on recent progress in reform of inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption, http://www.oecd.org/fossil-fuels/publicationsandfurtherreading/OECD-IEA-G20-Fossil-Fuel-Subsidies-Reform-Update-2021.pdf.

[17] Reuters (2022), U.S. to resume oil, gas drilling on public land despite Biden campaign pledge, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-resume-oil-gas-drilling-public-land-despite-bidencampaign-pledge-2022-04-15/.

[5] Vivid Economics, UNFCCC Race to Zero campaign and the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (2021), Net Zero Financing Roadmaps, https://www.gfanzero.com/netzerofinancing.

Notes

← 2. Agricultural support that potentially undermines the sector’s sustainability average at around USD 338 billion per year in 2018‑20, and USD 391 million in 2019-2021 in the 54 OECD and emerging countries covered by the OECD Agriculture Policy Monitoring reports (OECD, 2021[3]; OECD, 2022[22]). OECD and IEA data show that government support for the production and consumption of fossil fuels across 81 major economies totalled USD 351 billion in 2020. More recent OECD/IEA figures indicate fossil fuel support increased markedly in 2021 to over USD 700 billion with further increases expected in 2022 due to the lingering effects of COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine (OECD, 2021[23]; OECD and IEA, 2021[24]).

← 3. Environmentally harmful support measures initiated in response to the COVID-19 pandemic are made up primarily of time-limited fossil fuel support and aviation tax changes. These data do not consider recent government support measures in response to the war in Ukraine and the current economic climate of high energy prices and soaring inflation, on which data is still emerging.