Emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have been steadily increasing their borrowing from the markets following a long period of low interest rates and high levels of global liquidity since the 2008 global financial crisis. The debt levels of EMDE sovereigns reached record highs during the COVID‑19 pandemic and have not yet returned to pre‑pandemic levels. Against this backdrop, macro-financial conditions worsened in 2022 due to soaring inflation, monetary tightening, geopolitical uncertainties and a deteriorating growth outlook. Increasing capital outflows led to a depreciation of EMDE currencies against the US dollar, exacerbating external debt burdens. With further deteriorations in sovereign credit ratings in 2022 and substantial debt due in the coming years, many EMDEs continue to face significant financing risks. This chapter presents an overview of sovereign bond issuance trends in EMDEs in 2022.

OECD Sovereign Borrowing Outlook 2023

3. Sovereign debt issuance trends in emerging market economies

Abstract

3.1. Introduction

The primary objective of this chapter is to analyse the main trends in emerging market and developing economy (hereafter ‘EMDEs’) sovereign bond markets. It presents the structure of sovereign debt issuance, borrowing costs, exposure to interest rate hikes and an overview of credit quality over time across regions. The key source of information is a dataset comprising over 7 500 government securities issued by 102 different EMDEs between 2007 and 2022 (see Annex 3.A for details of the methodology used).

Key findings

EMDE sovereigns’ gross issuances fell to USD 3.8 trillion in 2022, after peaking at USD 4.1 trillion in 2021. The People’s Republic of China (hereafter ‘China’) remained the largest EMDE sovereign issuer, accounting for 37% of the total gross debt issued, the highest share in over a decade.

On aggregate, EMDE sovereigns’ net borrowing fell by 25% in 2022 compared to 2021, with significant differences across regions. The sharpest decrease (88%) took place in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), driven by developments in oil markets, and consequent improvements in the fiscal balances of oil-exporting countries. Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and European issuers, on the other hand, increased their net debt issuances compared to 2021.

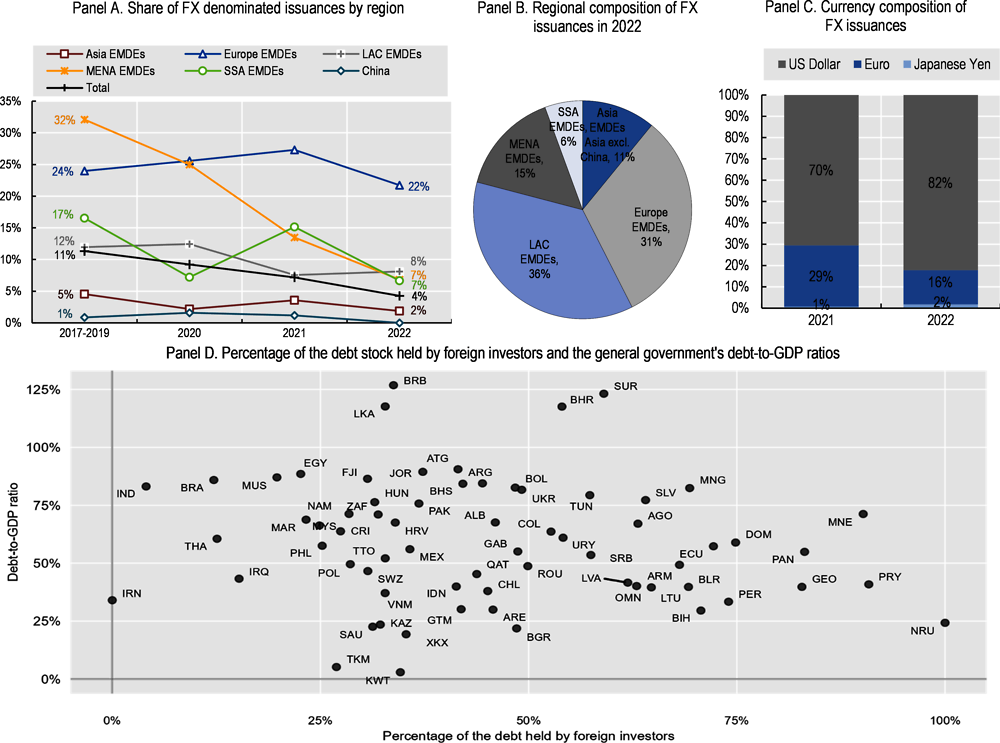

The share of foreign currency-denominated debt issuances has continued to decrease for EMDEs, falling from 7% in 2021 to 4% in 2022. The exception to this trend was the LAC region, where the share of foreign currency denominated debt remained constant at around 8%. Moreover, the currency composition of foreign currency denominated debt further tilted towards the US dollar, increasing from 72% in 2021 to 80% in 2022.

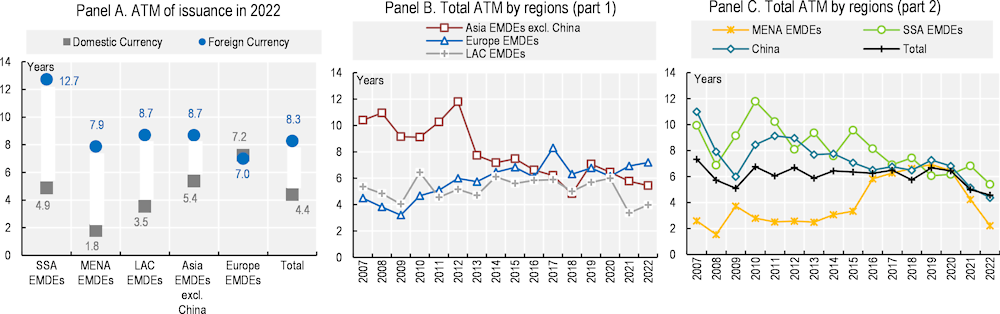

The average term-to-maturity (ATM) at issuance shortened across all regions, falling from 9.6 to 8.3 years on aggregate, as issuers relied more heavily on shorter-term securities amid increasing uncertainties and rising borrowing costs.

The average yield to maturity at issuance of fixed-rate USD-denominated government bonds issued by EMDEs increased from 4.4% in 2021 to 5.3% in 2022. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) had the highest yields (7.9%) while the LAC region issued with the lowest yield (4.6%). However, in terms of increases in borrowing costs, LAC saw a 1.45 percentage point increase in yields, the largest increase from 2021 to 2022 across all regions, while MENA saw the smallest increase of 0.21 percentage points.

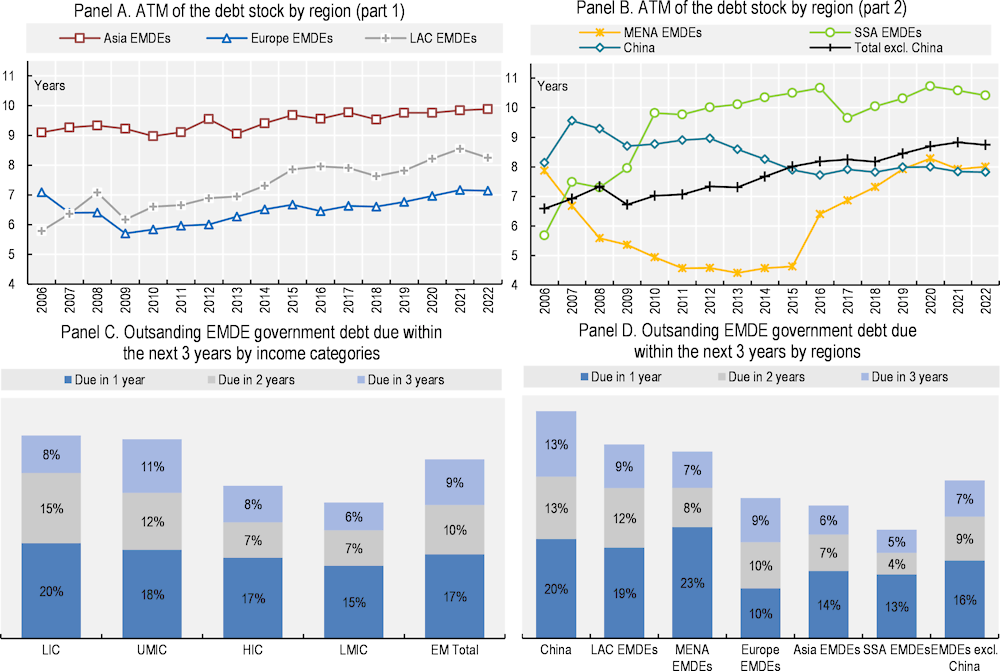

The ATM of the debt stock is at record high levels, but about one‑third of EMDE debt is coming due within the next three years. In particular, low-income countries (LICs), with already low credit quality, face greater refinancing risk as 20% of their outstanding debt is due within one year and 42% within three years.

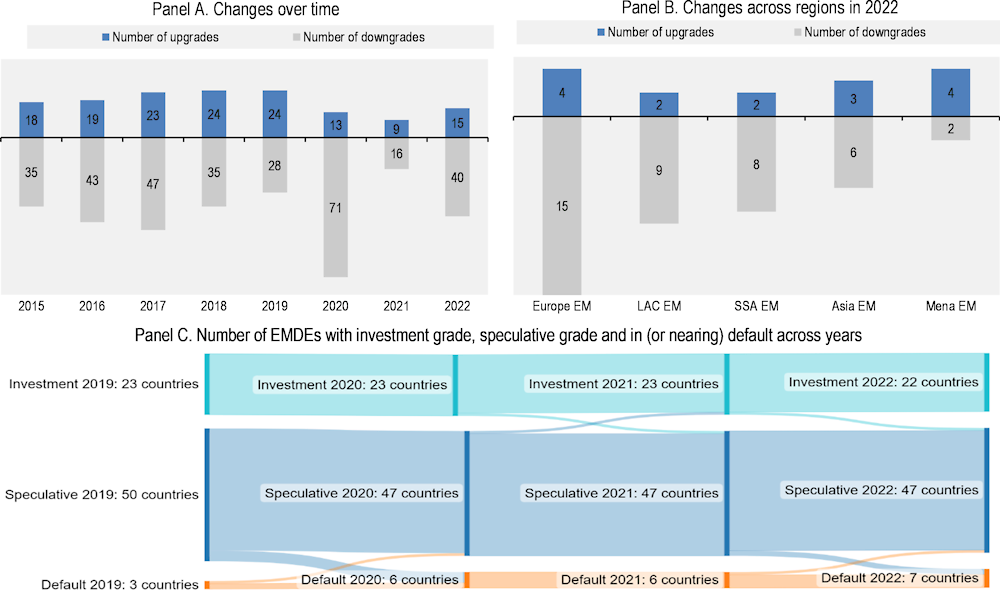

The value‑weighted credit quality of issuance deteriorated in 2022, following a wave of 40 downgrades, 15 of which were related to European sovereigns, mostly reflecting the effect of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine on risk premia and borrowing costs. MENA became the region with the highest credit quality, surpassing Asia (excluding China), mainly due to the increased share of debt issuance by commodity-exporting countries with a high credit rating, such as Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

3.2. Trends in EMDE sovereign gross borrowing

Global financial conditions tightened considerably in 2022 amid a deteriorating growth outlook, high inflation and consequent monetary tightening. Geopolitical tensions following Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine fuelled the rise in inflation and weakened investor sentiment, causing capital outflows and currency depreciations for EMDEs. Against a backdrop of fiscal policy normalisation following the pandemic, sovereigns faced the challenge of refinancing substantial amounts of pandemic-related debt at higher costs, which weighed on debt issuance in 2022.

3.2.1. Gross borrowing by EMDE sovereigns from the markets declined in 2022 mainly due to a reduction in net borrowing requirements and a stabilisation of refunding needs

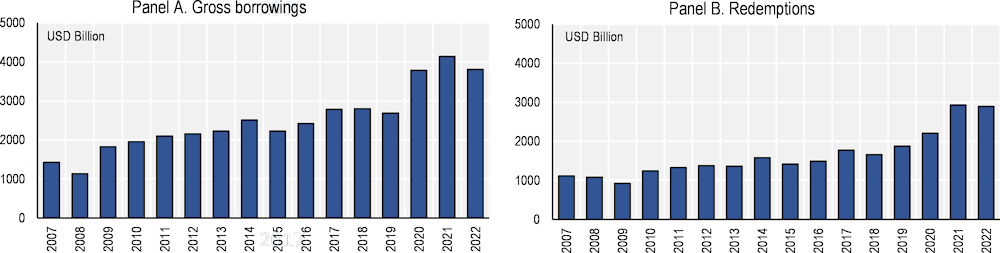

EMDEs issued significant amounts of debt during the pandemic, in response to heightened funding requirements and reduced government revenues. Issuance peaked at USD 4.1 trillion in 2021, marking a 50% increase compared to the three‑year average prior to the pandemic and a 10% increase compared to 2020 levels. EMDE gross debt issuance remained high in 2022, albeit declining by 8%, reaching a total of USD 3.8 trillion, slightly higher than in 2020 (Figure 3.1 Panel A). This reduction is more pronounced across all regional categories excluding China. In contrast to other EMDEs, Chinese gross debt issuance increased by 23% last year, impacted by the country’s restrictive zero-COVID‑19 policy and extraordinary refinancing needs from special treasury bonds which were issued in 2007 and matured in December 2022, worth 8% of its gross issuances in 2022.1 Without China, which represented 37% of total EMDE gross debt issuance in 2022, the decrease in issuance amounts to 25%. Looking at country-level data, the majority of EMDE sovereigns issued less debt in government securities in 2022 compared to their 2021 levels, with a few exceptions, including Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, China and Mexico.2

Figure 3.1. Central government gross debt issuance by EMDEs

Source: Refinitiv; and OECD calculations.

Two main factors are responsible for the significant decline in gross debt issuance in 2022. First, aggregate net borrowing needs declined from USD 1.2 to 0.9 billion partly linked to the lifting of COVID‑19‑related support measures and strong economic recovery after the pandemic (OECD, 2022[1]). When compared to 2021, 75 out of 102 EMDE sovereigns improved their fiscal balances in 2022, explaining the reduced borrowing from many EMDE sovereigns (International Monetary Fund, 2023[2]). Second, many EMDE sovereigns overborrowed in 2020 and 2021 to benefit from historically favourable funding conditions, using the augmented cash balances to smooth expected borrowings in 2022, a year of prospectively higher interest rates, amid mounting global inflationary pressures, reducing their medium-term borrowing costs.

EMDEs’ refinancing needs remained largely stable in 2022 at USD 3.9 billion, similar to the level in 2021 due to the pandemic-related issuances of 2020 and 2021 (Figure 3.1 Panel B). When China is excluded, refinancing needs drop from USD 3.0 to 2.4 trillion, still 15% higher than average pre‑pandemic levels.3 The persisting high refinancing needs reflect challenges to fund maturing debt through fiscal surpluses.4 With the increase in interest rates and slower economic growth, it is unlikely that sovereigns will be able to generate enough surpluses to fund significant parts of their maturing debt. This increases their exposure to fluctuations in funding conditions. Refinancing needs can also be reduced through lengthening maturities, the opposite of what happened in 2022 as investors’ appetite for longer-term EMDE sovereign declined amid rising inflation risks and debt management offices (DMOs) reacted to the most rapid surge in interest rates in decades by issuing shorter-term securities.

3.2.2. The nominal value of gross debt issuance declined across all regions

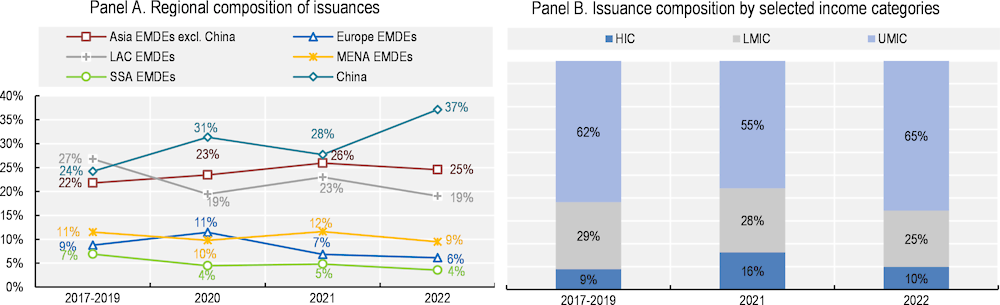

The regional composition of EMDE gross issuance reveals a relatively significant increase in the Chinese share since 2017, with corresponding decreases in other regions except for the rest of emerging Asia, whose share remained stable (Figure 3.2 Panel A). In 2022, the only two regions whose share of EMDEs’ gross issuances increased were China and EMDE Europe.

However, in all regions except China, the nominal value of gross debt issuance declined considerably in 2022. The sharpest decrease occurred in SSA, where gross issuance fell 32%, followed by 25% in MENA, 25% in LAC, 17% in EMDE Europe, and 13% in EMDE Asia excluding China. Conversely, China’s gross issuance rose by 23% in the same period. The decrease in gross issuances across regions was not primarily driven by EMDE currency depreciation (i.e. as values are converted to USD using the exchange rate of the issuance date, the amount issued in domestic currencies in 2022 declined compared to 2021 due to a pure exchange rate effect). Only about 31% of EMDEs issued a higher amount of domestic currency denominated debt in 2022 when compared to 2021 levels.5

Figure 3.2. EMDE sovereign gross debt issuance by regional and income categories

Source: Refinitiv; and OECD calculations.

There was no change in the ordering of the income categories by gross issuances – the largest issuer group remained as upper middle‑income countries (UMIC), which accounted for more than half of all gross issuances in 2022, followed by low-middle‑income countries (LMIC) and high-income countries (HIC) (Figure 3.2 Panel B). The share of UMIC also rose in 2022, due to China, which represents 37 percentage points (pp) of the 65 percentage points of the share of UMIC, and by a few countries (e.g. Algeria, Argentina, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria and Jordan) that increased their gross issuances in 2022 against the downward trend found in the majority of EMDEs in the period. On the other hand, several HICs such as Bahrain, Chile, Hungary, Oman, and Panama reduced their gross issuance compared to 2021, explaining the fall in the issuance share of HICs. In LMIC, all five largest issuers (in terms of the amount issued) reduced their gross issuances in 2022 – namely India, Egypt, Pakistan, Indonesia and the Philippines, ordering by the amount issued in the period. Of these, Egypt and Pakistan are in debt distress, suggesting that their decrease in gross issuances is not an indication of a healthier fiscal situation.

3.2.3. EMDEs net issuance increased in LAC and Europe in 2022, but decrease in Asia, MENA and SSA

Net borrowing requirements or needs refer to the difference between gross borrowing and refinancing needs. In AEs, the vast majority of funding needs are financed through marketable debt. Thus, net borrowing is more closely aligned with fiscal needs, with most of the differences being driven by movements in financial assets, especially cash balances. In other words, when net borrowing is higher than fiscal deficits, this might be attributed to overborrowing (as in 2020 and to some extent 2021) and when the opposite happens it might be attributed to a reduction in cash balances (as in 2022). In the case of EMDEs, however, this is not necessarily the case. EMDEs typically do not have as developed local bond markets as AEs and therefore more frequently rely on other means to fund their operations, notably loans and sometimes the accumulation of arrears. This means that movements in net borrowing needs can differ more strongly from fiscal balances. For instance, a country might see a decrease in its net borrowing needs measured in marketable debt despite an increase in the fiscal deficit as investors might not be willing to lend to an EMDE with difficulties to meet its obligations. In this case, the disparity between the movements in the fiscal balance and net borrowing needs measured in marketable debt could suggest a decline in market access. Another option is that countries could borrow at more favourable terms with private financial institutions or multilateral organisations. This means EMDEs’ net borrowing needs in marketable debt require careful assessment, considering the state of each country’s local bond market as well as its fiscal position.

Examples of disparities between movements in net borrowing needs and fiscal balances occurred at the peak of the COVID‑19 crisis. Although surging significantly across all regions in 2020, net debt issuances by MENA and SSA countries did not follow the general trend, rising only by 2% in MENA and declining by 42% in SSA, as several issuers with weaker fundamentals, especially low-income countries, lost access to international bond markets during a time of financial turmoil in 2020. Although financing needs remained higher than pre‑pandemic levels in 2021, all regions except MENA and SSA reduced their net debt issuance compared to 2020 levels, thanks to developments in vaccination rollouts and the lifting of some pandemic-related restrictions. In SSA and MENA however, net issuance increased significantly in 2021, by 139% and 32% respectively, reaching levels higher than prior to the pandemic in both cases. The surge in net debt issuance in the SSA region was mainly due to several issuers (including Benin, Cameroon, Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal) regaining access to markets in 2021. Notably, Benin and Côte d’Ivoire issued large amounts of Eurobonds with a maturity of 22 years each, enhancing their future redemption profile and reducing their exposure to near-term deteriorations in financial conditions.

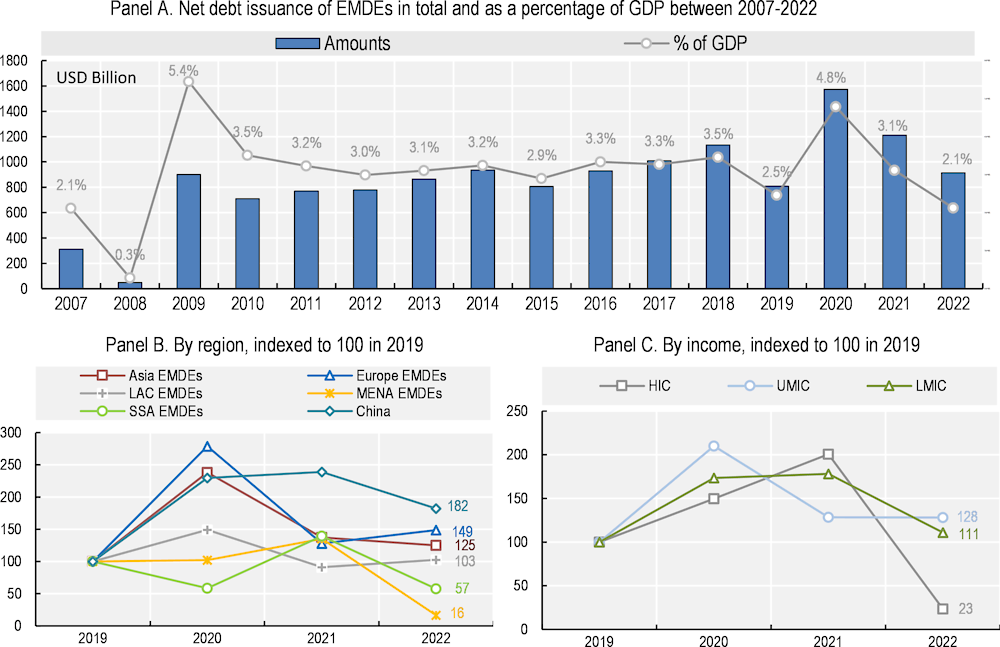

After peaking at nearly USD 1 570 billion in 2020 in the wake of the COVID‑19 crisis, EMDEs’ net borrowing needs have gradually decreased to USD 913 billion in 2022, a figure which is still 12% above the 2019 values (Figure 3.3 Panel A). This overall trend masks variation across regions, with net borrowing needs declining in all regions except for Europe and LAC. Asia (including China), MENA, and SSA significantly reduced their net debt issuance levels in 2022.

Of the 18 countries in Asia, ten reduced their net borrowing requirements in 2022. Overall, this decline suggests an improvement in these countries’ fiscal stance, also implied by the improvement in their fiscal balances as well as the decrease in their total debt-to-GDP ratios. China was the only issuer among these ten whose fiscal deficit widened between 2021 and 2022, from 6% to 8% of GDP. Its debt-to-GDP ratio also increased from 72% of GDP to 77% with the country’s zero-COVID‑19 policy being in place during large parts of 2022. Other notable exceptions to this positive trend in their fiscal stances are Bangladesh, Myanmar, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, with the latter two being in significant debt distress.

In MENA, countries issued the lowest net amount in more than a decade, plummeting from USD 177 to 21 billion between 2021 and 2022. One of the drivers of this decline is the increase in commodity prices, particularly benefiting the fiscal positions of oil and natural gas exporters following the unwinding of COVID‑19‑related measures.6 Net issuance was positive only in five out of 13 MENA issuers, namely Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, and the amounts were below those in 2021 with the exception of Algeria and Jordan. In SSA, 17 out of 23 issuers reduced their net borrowing in 2022.

Figure 3.3. EMDE net debt issuances

Source: Refinitiv; IMF (2022[3]), World Economic Outlook, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2022/10/11/world-economic-outlook-october-2022; and OECD calculations.

In SSA, net debt issuances decreased with several large issuers such as Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria reducing their net debt issuance by more than 50% compared to 2021, driving the aggregate decrease in net borrowing in the region. As opposed to Asia, the fall in net borrowing of SSA issuers was not accompanied by a stronger fiscal stance and improved debt-to-GDP ratios. With the exception of a few countries, including Gabon, Mauritius and Tanzania, the debt-to-GDP ratios increased in most SSA countries. Similarly, 13 out of 17 issuers which reduced their net borrowing from the markets experienced an increase in their debt-to-GDP ratios in 2022, suggesting some SSA issuers borrow less from markets and possibly met some of their financing needs through other means.

Conversely, net borrowing needs measured in marketable debt rose in EMDEs in Europe and LAC – the amounts of the three largest emerging Europe issuers (in terms of the amount issued), namely Russia, Türkiye and Hungary, increased by 29%, 27% and 25% respectively in 2022, driving the upward trend in the region. In particular, Russia had a primary fiscal deficit of 2.2% in 2022, as opposed to a 0.8% surplus in 2021 while the deficit of Ukraine grew from 4% in 2021 to 17%, showing the impact of the war on sovereign financing needs. In the LAC region, the increase in net debt issuance was due to Argentina, Brazil and Mexico, who issued significantly higher net amounts in 2022 compared to 2021. The fiscal balance of Brazil and Mexico also worsened in 2022.

Contrasting movements in the net debt issuance in marketable debt as a percentage of GDP to movements in total debt as a share of GDP can also provide insights into the structure of countries’ debt funding. For instance, Ukraine issued net marketable debt equal to 3% of its GDP in 2022, while its outstanding gross public debt-to-GDP ratio increased by 33 percentage points (International Monetary Fund, 2023[2]). Similarly, Sri Lanka’s net marketable debt issuance to GDP ratio of 8% in 2022 contrasts with the rise in its total indebtedness of 15 percentage points of GDP from 2021 to 2022. One of the ways in which countries are funding their needs outside of bond markets is through loans. In recent years, China has become the largest bilateral creditor to developing economies in the world, holding a substantial amount of debt, especially for low-income countries in Africa and several Asian countries. Given that Chinese loans often have higher interest rates and shorter maturities than loans offered by official creditors (such as IMF and the World Bank), repayment of Chinese loans may be challenging for some debtors (Horn et al., 2023[4]). In addition, the opaqueness of the terms of most bilateral loans makes it complicated to produce a complete picture of LIC indebtedness, exacerbating debt transparency problems. Box 3.1 explores the role played by China as a bilateral creditor for EMDEs.

Lastly, Figure 3.3 Panels B and C illustrate the net borrowing needs across regions and income categories compared to their pre‑pandemic values of 2019. It shows that in all regions except MENA and SSA, net borrowing needs in marketable debt are still above pre‑pandemic figures, especially in China and EMDEs in Europe. In terms of income categories, then only in HIC net borrowing needs in marketable debt returned to pre‑pandemic levels.

Box 3.1. China’s role as a creditor to EMDEs

China’s lending activities

Over the past two decades, China has emerged as a significant creditor to emerging markets and developing economies. This development is the result of several factors, including China’s rapid economic expansion, its consequent increasing global influence, and its desire to foster closer economic ties with other developing countries. The sheer magnitude of China’s lending activities to EMDEs has placed it among the top creditors in the global financial system. In this context, it is essential to analyse the composition and nature of China’s lending portfolio. This includes the distribution of loans across regions and sectors, the terms and conditions associated with these loans, and the overall impact on the recipient countries’ debt sustainability.

China’s lending activities encompass a wide range of sectors, with a particular focus on infrastructure, energy, and transportation projects. These investments often align with China’s broader strategic objectives, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which aims to enhance connectivity and economic integration across Asia, Europe, and Africa. By investing in critical infrastructure projects, China is able to strengthen trade links, promote regional development, and establish itself as a key player in the global economy. In addition to infrastructure investments, China’s lending also extends to other sectors, including agriculture, manufacturing, and technology.

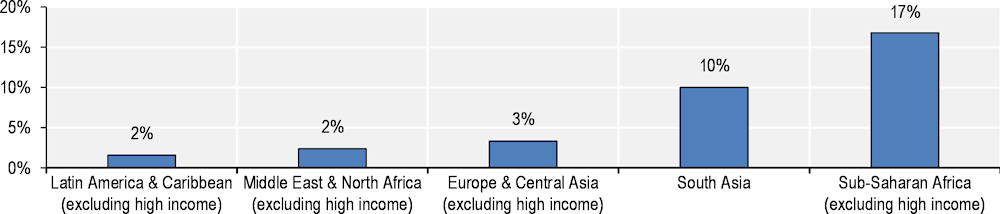

China is lending to several regions, covering countries in Africa, Latin America, and Asia. In fact, 17% of Sub-Saharan (excluding high-income) and 10% of South Asian external sovereign debt was held by China in 2021 (Figure 3.4). While there are variations in the scale and scope of lending across these regions, the overall trend points to a growing presence of Chinese lending to EMDEs. This has led to a reconfiguration of the global creditor landscape, with China now playing a prominent role in shaping the financial dynamics between developed and developing countries.

Figure 3.4. Share of China as a creditor in external debt by region

Note: Includes marketable debt and loans as of 2021.

Source: World Bank (2023[5]), International Debt Statistics, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/international-debt-statistics#.

Debt vulnerabilities and implications for emerging markets

Despite the abovementioned mutually beneficial incentives, China’s lending activities in emerging markets can also lead to external vulnerabilities and balance of payments risks for the recipient countries. The repayment of loans extended by China may put pressure on the foreign exchange reserves of these countries, especially considering that they often carry relatively high rates (Horn et al., 2023[4]), leading to a potential balance of payments difficulties.

Another concern related to China’s lending activities in emerging markets is the issue of debt transparency and governance. China’s lending practices have often been characterised by a lack of transparency, with limited information available on the terms and conditions of the loans. This opacity can hinder accurate assessments of the debt sustainability and risk exposure of the recipient countries. Furthermore, weak governance and institutional capacity in some emerging market countries can exacerbate these risks. Inadequate oversight, corruption, and mismanagement of public funds can undermine the effectiveness of the financed projects and impede debt sustainability.

Source: Based on Wang (2022[6]), China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2022 and World Bank (2023[5]), International Debt Statistics, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/international-debt-statistics#.

3.3. Composition of EMDE debt issuances

3.3.1. The share of foreign denominated debt continued to decline in 2022 in all regions, except LAC

In sovereign debt literature, the “original sin” refers to the inability of many EMDEs to borrow in their domestic currency, forcing them instead to borrow in foreign currencies, causing a currency mismatch between tax receipts and debt servicing costs and preventing their local bond markets from developing (Eichengreen and Hausmann, 1999[7]; Eichengreen, Hausmann and Panizza, 2005[8]). Countries suffering from the original sin struggle to participate in and benefit from greater currency flexibility due to the limitations of monetary policy and reliance on foreign currencies. This results in more volatile interest rates, fragile financial positions, and greater macroeconomic volatility, including wider output fluctuations and unstable capital flows. These countries have lower credit ratings and can face challenges in accessing international capital markets, making their economies less stable and more crisis-prone compared to advanced countries, especially in times of significant exchange rate volatility, growing fiscal needs and rising interest rates. The problem is especially pressing in countries with low levels of exports, since this limits the availability of hard currencies, increasing debt servicing costs in domestic currencies during periods of local currency depreciation.

Following an improvement in EMDE macroeconomic policy frameworks, some EMDEs have greatly improved the development of their local bond markets, with the average share of foreign currency-denominated bonds in total issuance falling from 15% in 2005 to 11% in 2019, prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic. This development was widespread, with the share shrinking in all regions except Europe. Following the COVID‑19 pandemic, the dominance of the domestic currency bond market became even more prevalent, with the share of foreign currency-denominated debt declining to 4% in 2022 (Figure 3.5).7

In 2022, all regions except LAC significantly decreased their shares of debt issued in foreign currency. The sharpest decline took place in Sub-Saharan Africa, where foreign currency issuance fell from 15% to 7% of total issuance – only three sovereigns from Sub-Saharan Africa issued foreign currency-denominated debt in 2022, compared to nine in 2021. Countries in Asia (excluding China, which did not issue any foreign currency denominated debt in 2022) issued 2% of their gross debt in foreign currency, the lowest level since 2007, and slightly lower than 2020 figures.8 In Europe and MENA, foreign currency issuance represented 22% and 7% of 2022s gross borrowing, respectively, a decrease of roughly 6 and 7 percentage points compared to 2021.

However, some countries still rely heavily on foreign currency-denominated borrowing. For instance, in 13 out of 38 countries that issued foreign currency debt in 2022 more than half of their marketable gross issuances were in foreign currency. Six of these countries were in LAC and three were in Europe. Concerning loans, it is worth emphasising that many EMDEs rely on loans in hard currencies to fund their needs, meaning that their exposure to foreign currency risk can be much greater than what is implied considering only marketable debt.

In terms of the currency composition of foreign currency debt, the euro and US dollar are dominant, together accounting for more than 98% of all foreign denominated debt issuance by EMDEs since 2015. While varying in time and size, other foreign currency borrowing has mainly been in Japanese yen, Swiss franc, British pound, Russian rouble and Chinese yuan. Historically representing the largest share among in foreign currency borrowing, US dollar debt accounted for 73% of the foreign currency denominated debt issued by EMDEs in 2019, before the COVID‑19 pandemic. This share decreased slightly in both years during the pandemic, falling to 70% at the end of 2021, while the share of the euro increased from 24% to 29% during the same period. In 2022 however, this composition changed significantly, as the share of USD issuance jumped to 82% and the euro share declined to 16%, although it still represents about half of all issuances from EMDE in Europe (with the other half being denominated in USD). These fluctuations were driven by Argentina, Indonesia, Mexico, Romania and Türkiye. In particular, out of 27 countries that issued euro-denominated debt during 2020 and 2021, only nine did so in 2022, while 33 out of 52 EMDEs continued to issue USD-denominated debt, driving the change in the relative shares of euros and the US dollar.

Figure 3.5. EMDEs’ exposure to foreign markets in terms of currency and investor base

Note: Values as of 2022 for the Debt-to-GDP ratios and as of 2021 for the percentage of the debt held by foreign investors.

Source: OECD calculations based on Refinitiv data and IMF Sovereign Debt Investor Base for EMDEs.

3.3.2. EMDEs still have significant room to diversify their investor base domestically and to improve their debt transparency

There are data gaps regarding the indebtedness of many EMDEs whose information is scattered across creditors that provided bilateral loans to sovereigns. This lack of readily and timely available debt data frustrates attempts to analyse debt sustainability and risk exposure, in turn making the improvement of portfolios and exploring hedging options more difficult. Addressing the lack of debt transparency for EMDEs, including the challenges associated with non-marketable debt, is crucial to ensuring financial stability and effective risk management. For these reasons, efforts have been undertaken to enhance debt management capabilities and openness via global programmes like the World Bank’s support for debt management in low- and middle‑income nations and the OECD’s Debt Transparency Initiative.

Another challenge pertains to the development of a diversified domestic investor base. Although the development of local bond markets can decrease the risk of debt distress, it only does so to a certain extent. Many EMDEs relied on foreign investors’ willingness to lend in local currencies when the domestic investor base was small. Although this has reduced exposure to exchange rate fluctuations, it also made capital flows more volatile (Onen et al., 2023[9]; OECD, 2022[10]). Specifically, to roll over their debt, countries rely on foreign investor demand, which fluctuates with global financial conditions. In times of high borrowing needs and unfavourable funding conditions, foreign investors might be reluctant to fund sovereigns with weaker fundamentals, creating a net capital outflow, devaluating the countries’ local currencies and affecting the economy accordingly (Önder and Sunel, 2021[11]).

Figure 3.5 Panel D illustrates how EMDEs are vulnerable to foreign investor demand by examining their debt-to-GDP ratios and the percentage of their debt that is held by foreign investors. On average, 44% of EMDEs’ sovereign debt is held by foreign investors, with this percentage exceeding 25% in roughly 90% of them. In addition, in 35% of the cases, the percentage of the debt held by foreign investors exceeds half of the sovereign debt outstanding, and in 55% of these cases, the debt-to-GDP ratio is above 50%, meaning that these countries own at least one‑quarter of GDP to foreign investors. Contrasting to AEs, only five countries are in this situation (namely Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Greece and Slovenia) and these are all from the euro area, which means that their debt is often held by other EU countries to which they also tend to export significantly due to the free trade policy agreed between EU members and to their geographical proximity. Therefore, for EMDEs that were already able to reduce their exposure to foreign currency risk, the next step is to build a strong domestic investor base, ideally consisting of varying types of investors, such as pension funds, insurance companies, and personal investors.

3.3.3. EMDEs face difficult trade‑offs concerning lengthening maturities and reducing reliance on securities denominated in foreign currencies

The average value‑weighted term-to-maturity at issuance (henceforth “ATM of issuances”) measures the maturity of issuances in a given year, weighted by issue size. All else equal, a higher ATM implies a lower rollover risk in the future. Conversely, a shorter average term-to-maturity of issuance translates into higher rollover risk in the future as the issuer is more sensitive to changes in financial conditions. In addition, ATM of issuances also reflects how long the current market borrowing costs will be borne by the issuer for fixed rate securities (i.e. this does not apply for floating rates and index-linked debt as the principal or coupons of these instruments are already sensitive to market fluctuations before maturity). In times of tight financial conditions, issuing securities with a longer maturity means that these costs will be paid for a longer period and vice versa. There is also typically a term premium, meaning that the yield for long maturities tends to be higher than for shorter maturity securities. Sovereign issuers aim at minimising borrowing costs and risks and face difficult trade‑offs when deciding the maturity of their issuances. In times of monetary tightening, this trade‑off implies difficult choices as lengthening maturities can reduce the exposure to further interest rate hikes but at the cost of locking in a higher yield for a long time while shortening maturities can further expose the issuer to future deteriorations in funding conditions and high debt redemptions.

In the case of EMDEs, the choice of lengthening the maturity structure of the debt portfolio tends to be even more challenging given that the demand for long maturities depends on the securities’ currency denomination. Investors are not as willing to buy long maturities denominated in local currencies due to the inflation risk in contrast with buying long maturity bonds in hard currencies like the US dollar or the euro. Therefore, the choice of some EMDEs is between either lengthening their maturities to reduce their refinancing risk and their exposure to fluctuations in funding conditions at the cost of higher foreign currency risk and higher borrowing costs or, alternatively, issuing securities with a relatively shorter maturity in domestic currency, bearing higher refinancing risk and sensitivity to fluctuations in funding conditions to reduce their exposure to foreign exchange risk. For instance, in 2022 the ATM of issuances of debt denominated in foreign currency is 7.8, 6.1, 5.2, and 3.3 years longer than those borrowed in domestic currency in SSA, MENA, and EMDE Asia (excluding China), respectively (Figure 3.6 Panel A). In EMDEs in Europe, the ATM of issuances are roughly the same regardless of the currency of denomination. In times of distress, however, even the debt denominated in foreign currency can be considered a higher risk for some investors to bear – in these cases, EMDEs with relatively weak fundamentals are forced to borrow both short term and in foreign currencies.

3.3.4. The securities issued in 2022 have, on average, a shorter maturity than those issued in 2021 in Asia and SSA, but longer in LAC and Europe

Recent movements in the ATMs illustrate the challenges faced by EMDEs in lengthening the maturity structure of their debt portfolio (Figure 3.6 Panels B and C). In 2020, the deterioration in investor confidence due to the COVID‑19 pandemic resulted in a decline in ATM of issuances, from 6.7 to 6.4 years on average across EMDEs. Turning more to their domestic debt markets, sovereigns issued a higher percentage of short-term securities, reducing the ATM of their domestic currency denominated debt issuance. In particular, EMDEs’ ATM of issuances in domestic currency fell across all regions except SSA. On the other hand, the ATMs of foreign currency denominated issuances exhibited the opposite behaviour, increasing from 12.9 years to 14.7 years between 2019 and 2020. Two exceptions to this pattern were China and SSA whose ATM of foreign currency denominated debt issuances decreased by 2% and 12%, respectively. Especially the case of SSA serves as an example of how in times of distress, issuers with weaker fundamentals are unable to borrow with long maturities, even in hard currencies, as the ATM of foreign currency denominated debt issued by SSA sovereigns continued to decline also in 2021 and 2022, falling from 16.8 years in 2019 to 12.7 years in 2022. In 2021, despite some developments in rollout of vaccines and a strong recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis, the pattern of shortening maturities for gross debt issuance continued except in Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa, which have the highest shares of foreign currency denominated debt in gross borrowing, at 27% and 15%, respectively, against 7% of the EMDEs average for 2021.9

In 2022, heightened macroeconomic and geopolitical uncertainty negatively affected the ATM of issuances, which fell for all regions except Europe and LAC (Figure 3.6 Panels B and C). The average decrease was from 5.0 to 4.6 years. The smallest decrease occurred in Asia excluding China, from 5.8 years to 5.4 years. The steepest fall, on the other hand, was observed in MENA with a decline of 48%, from 4.2 years to 2.2 years. LAC, which was the region with the lowest ATM of issuances in 2021, became the region with the second lowest one after MENA in 2022, increasing its ATM by 17%. This movement was due to Argentina, Brazil and Mexico whose ATM of issuances increased by 19%, 17% and 16% respectively.

Figure 3.6. The average term-to-maturity (ATM) of issuance for EMDE regions, weighted by issue amounts

Source: Refinitiv; and OECD calculations.

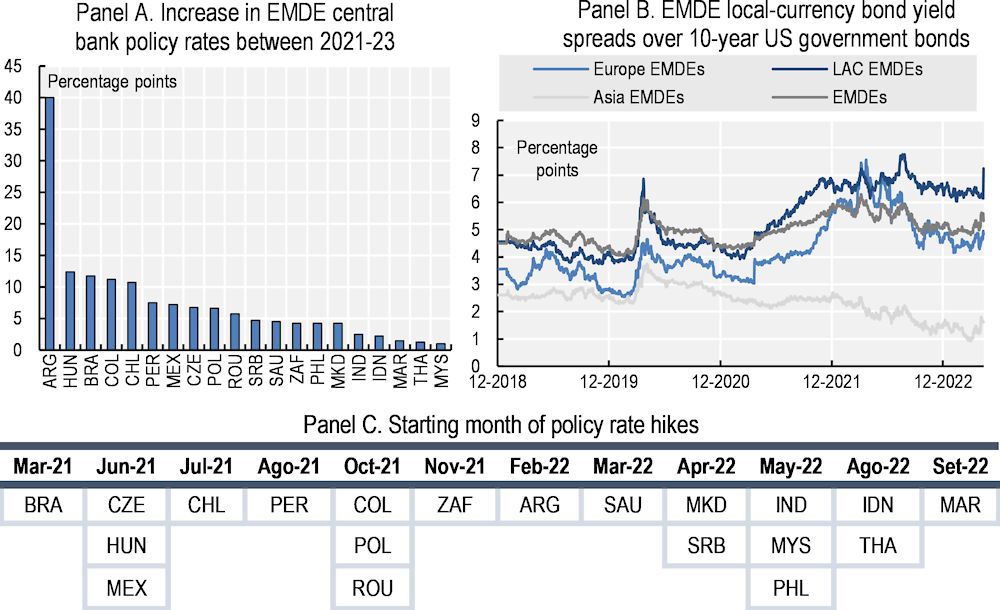

3.4. Borrowing costs rose sharply due to global monetary tightening in the face of surging inflation

3.4.1. Central banks vary in the timing and the pace of monetary tightening, with Asia seeing a delayed and smaller increase in policy rates

During the period from December 2021 to December 2022, central bank policy rates displayed distinct regional patterns, with AEs and EMDEs responding differently to inflationary pressures. In order to curb soaring inflation and anchor inflation expectations, many central banks increased interest rates in 2022, tightening financial conditions for EMDEs considerably (Figure 3.7). Only a few EMDE central banks, notably in Türkiye and Russia, reduced their policy rates in 2022 when compared to the level at the end of 2021.10

There were significant regional differences between central banks in the timing and the pace of the increase in policy rates, with AEs and EMDEs in Asia displaying a tendency to raise rates later and less than other EMDEs. 11 out of the selected 14 EMDE central banks outside Asia rose policy rates before the United States, in March 2022, and only Morocco did so after the European Central Bank (ECB), in July 2022. On the other hand, all six Asia EMDEs rose rates in or after March 2022.11 The pace of the monetary tightening also was slower in Asia, with the average increase in policy rates reaching 2.6 percentage points in the region in this monetary tightening cycle, below the average of 7.5 percentage points in other EMDEs in the same cycle (excluding the outlier Argentina). The strongest movements in policy rates were experienced by LAC countries, with all six LAC countries covered in this analysis being among the seven countries in which policy rates rose the most. This strong movement in LAC partially reflects relatively higher inflation rates in the region in 2022 of 72.4% in Argentina, 11.6% in Chile, 10.2% in Colombia and 7.9% in Mexico with the average in EMDEs in Asia being 3.8% per annum (IMF, 2022[3]).

Figure 3.7. Change in the main policy interest rate of EMDE central banks and EMDE local currency bond spread over ten‑year US Government bond yields

Note: Panel A displays the difference between the maximum and the minimum policy rate between January 2021 and March 2023 for EMDEs that experienced a rise in policy rates in the period. EMDEs that decreased policy rates in that period, and are not covered by the Panel, are China, Russia and Türkiye.

Source: Bank of International Settlements; Refinitiv; and OECD calculations.

3.4.2. EMDEs’ sovereign bond spreads have risen substantially since 2021

In times of monetary tightening with high macroeconomic and geopolitical uncertainty, yield spreads of EMDE bonds over AE bonds tend to increase. In these cases, investors tend to opt for safe havens, causing a flight-to-quality movement with capital flowing to AE securities, perceived as more secure, and away from vulnerable economies, especially those with lower credit ratings, which are already exposed to capital outflows. In addition, before this monetary tightening cycle, many investors in EMDE sovereign bonds benefitted from positive real yields. However, 2022 marked a reversal in the trend of low interest rates in AEs (see Chapter 1), allowing investors to obtain positive real yields by investing in economies with strong fundamentals. For EMDE borrowers, these movements translate into higher borrowing costs and less liquid markets, both of which exacerbate debt sustainability risks.

The evolution of the spread of EMDE local currency sovereign bond yields over ten‑year US Government bonds has shown notable dynamics across regions in the post-pandemic period (Figure 3.7 Panel B). First, EMDE spreads started to rise in early 2021, significantly earlier than major AEs’ central banks started to raise policy rates, reflecting the fact that EMDEs’ central banks reacted more swiftly to the rising inflationary pressures and capital outflows in 2021.12 Second, after Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, in February 2022, there was a 0.4 percentage point increase in the spreads on average across EMDEs in one month, driven mainly by the especially acute hike for EMDEs in Europe, from 6.0% to 6.9%. However, this increase was small compared to the surge that took place in the 12 months before the start of the war, from 3.16% to 5.96%. Third, the increase in spreads caused by the geopolitical uncertainty following the war in Ukraine was gradually reversed throughout 2022, reaching roughly the same level it had prior to the start of the war around September 2022. Fourth, the market stress caused by the banking turmoil in early 2023 has caused yet another flight-to-quality movement, impacting EMDE spreads, with an increase in March 2023 still relatively small compared to the increase prior to the war in Ukraine. As EMDE sovereign bond yields are much higher than prior to the war, this suggests that the main driver of 2022s upward trend in EMDE yields pertains to the reaction of the yield curve to adjustments of AEs’ yields, and not to movements in spreads. There are, however, many exceptions – this analysis considers only the main issuers in each region whereas some specific countries suffered substantial distress.

In terms of regional patterns, the current macroeconomic and geopolitical developments affected Asia’s EMDEs in a very distinctive way. Yield spreads in EMDEs in Asia over the 10‑year US Government bonds have peaked in the wake of the COVID‑19 pandemic and has followed a clear decreasing trend since then, reaching less than 1% in February 2023. Overall, this reflects the superior fundamentals witnessed in major EMDEs in Asia. In particular, they rely less on securities denominated in foreign currency, which account for less than 2% of their issuances in 2022,13 against 10% for all other EMDEs, and they suffered less from recent inflationary pressures, allowing their central banks to increase rates less aggressively. Conversely, large issuers from LAC suffer from a deteriorated fiscal situation while EMDEs in Europe are located closer to the war zone and have large commercial ties with Russia and Ukraine, making them more vulnerable to the war. For instance, preceding the war, exports to Russia and Belarus were between 2% and 3% of GDP for some EMDEs in Europe such as the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, while for all major AEs in Europe such as France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK, this share is below 1% of GDP (OECD, 2022[12]).

3.4.3. EMDE borrowing costs soared with global macro-financial tightening

Another indicator of sovereign bond yields explored in this chapter is the average yield to maturity at issuance (YTM) of fixed-rate USD-denominated government bonds. This indicator is drastically different than the one just explored, of EMDE local-currency bond yield spreads over ten‑year US Government bonds, in two main regards. First, the YTM captures the actual borrowing costs borne by sovereign issuers while the spread captures the difference in benchmark yields – that is, the difference between the yields of EMDEs and US sovereign bonds, both priced based on transactions in secondary markets. Second, the YTM here is of securities issued in foreign currency while the spread was based on domestic currencies. This implies that the spread captures the difference in inflation expectations across the EMDE and the US. There is a major implication of this fact for debt sustainability analysis given that the interest rates used in these assessments are expressed in real terms and not in nominal terms, meaning that a country with a high nominal rate might have a low real rate and, therefore, no debt sustainability issues (Debrun, Ostry and Wyplosz, 2020[13]). It is worth noting, though, that despite the fact that inflation can initially improve fiscal balances and reduce public debt in the short to medium term, relying on expected inflation as a strategy for reducing debt ratios is neither desirable nor sustainable, with attempts to continuously surprise bondholders proving futile or harmful (International Monetary Fund, 2023[2]).

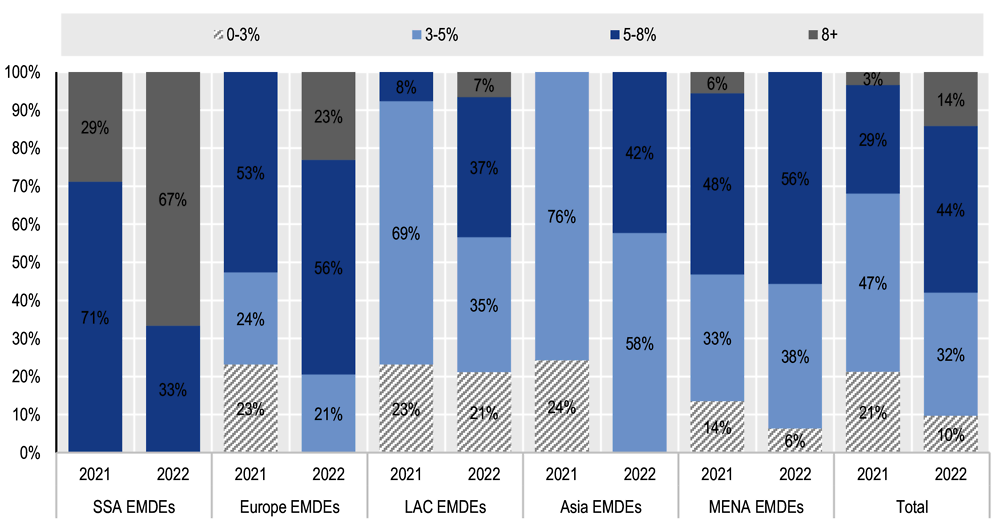

The volume share of fixed-rate USD-denominated government bond issuances across yield to maturity (YTM) categories weighted by their issue amounts has increased. by 1.1 percentage points in 2022, from 4.2% in 2021. In total less than 10% of the EMDE fixed-rate USD-denominated government bonds were issued with a yield under 3%; 32% with a yield between 3% and 5% and 58% with a yield above 5% in the primary markets. The percentage of debt issued with higher yields increased significantly across all regions in 2022 compared to 2021, with some regions breaching the 8% threshold for some issuances, which did not occur in 2021. The region with the highest yield on fixed-rate USD-denominated government bonds remained in SSA. On the other hand, EMDEs in Asia issued more than 50% of its debt at less than 5% yield in 2022 with an average yield of 4.6%, the lowest across all regions. However, this is still an increase of 33% compared to 2021. In MENA, the cost of issuing fixed-rate USD-denominated bonds remained relatively stable in 2022.

Figure 3.8. Volume share by yield group of fixed-rate USD-denominated bond issuance in 2022

Notes: Yields are calculated using fixed-rate USD-denominated securities with a maturity longer than 365 days. Comparison between EMDE yields between 2022 and 2021 is based on 34 EMDE sovereigns that issued in 2022 and the corresponding yields of 22 issuers who also issued fixed-rate USD denominated bonds in 2021.

Source: Refinitiv; and OECD calculations.

3.4.4. Average term-to-maturity is at record highs, but about one‑third of EMDE sovereign marketable debt is coming due within the next three years

The pace at which market interest rates affect borrowing costs depends greatly on the maturity profile of the debt portfolio. In that light, EMDE’s bond maturities have increased since the 2008 global financial crisis, reaching its highest level in more than 15 years in an environment of extraordinarily good funding conditions, thanks to supportive monetary policy in AEs (Figure 3.9, Panel A and B). On average, EMDEs’ (excluding China) debt stock ATM rose from 6.1 to 8.2 years between 2006 and 2022. This growth encompassed all regions except China. It is worth noting that since 2020, the EMDE debt stock’s ATM has remained largely unchanged across all regions despite the heightening macroeconomic and geopolitical uncertainties brought by the COVID‑19 crisis, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and monetary policy tightening.14

These averages mask the fact that the ATM still varies significantly across countries, revealing a wide range of exposure to refinancing and interest rate risks. For instance, among countries in which the debt-to-GDP ratio is above 50% in 2022, there are those with a very short debt portfolio, such as Algeria (2.4 years), Guinea-Bissau (three years), Zambia (3.3 years), Pakistan (3.3 years); and those with a relatively long debt portfolio, such as El Salvador (14.3 years), Fiji (14.8 years), Panama (15.2 years), and Gambia (19.5 years). Similarly, there also are disparities in the trends in the ATM of the debt stock, with Argentina, Albania and Kazakhstan experiencing a decrease respectively of 2.8, 1.4 and 1.4 years in the ATM of their debt stock in 2022, while the United Arab Emirates, Tunisia and Bolivia were able to significantly lengthen the maturity structure of their debt portfolios, by 20.0, 2.0 and 1.9 years, respectively.15 These wide disparities in ATM movements and levels reflect the corresponding asymmetries in the economic and financial situation of EMDEs.

Figure 3.9. The average term-to-maturity (ATM), weighted by outstanding debt

Note: ATM considered all securities except those with maturity below 30 days.

Source: Refinitiv; and OECD calculations.

Despite record-high ATMs, more than one‑third of total outstanding EMDE debt will mature by the end of 2025, with roughly half of this amount coming due in 2023, reflecting the high rollover risk EMDE sovereigns face (Figure 3.9, Panels C and D). Following the surge in funding needs and future uncertainties in the wake of the COVID‑19 pandemic, EMDE sovereigns have increasingly borrowed at short-maturities, most of which is still being refunded through the issuance of more short-term debt, increasing the exposure to short-term market risks. Among all the income categories, low-income countries (LIC) remained the group facing the highest rollover risk, as 20% of their outstanding debt is due within one year and 42% within three years, reflecting the reluctance of investors to bear the risk of long maturities in LICs. Some UMIC issuers also have a considerable share of debt maturing by the end of 2023. Notably, 60% of Argentina’s debt is maturing in one year, followed by Algeria (48%), Iraq (35%) and Thailand (30%), making these countries’ borrowing costs especially vulnerable to short-term fluctuations in market rates.

Looking at the regional level, MENA countries have the highest share of outstanding debt coming due in one year as 23% of the region’s outstanding debt will have to be repaid or refinanced by the end of 2023. As opposed to China, which also has a significant portion of the debt (20%) maturing in one year, MENA countries have higher exposure to international markets as historically a considerable share of the debt issued by MENA sovereigns is denominated in hard currencies to match the currency they receive from their exports, whereas, in China, foreign currency denominated debt issuance has been less than 2% over the past years. Following the MENA region, LAC countries also carry a high rollover risk with 19% of the outstanding debt coming due by the end of 2023, higher than the 17% average of EMDE countries. The heterogeneity of regions in their redemption structure is even more pronounced when China is excluded from the calculation, which has a significantly higher share of debt maturing until 2025 than the average of the rest of EMDEs weighted by their outstanding debt. EMDEs excluding China have 32% of their debt maturing in three years whereas including China this number jumps to 36%, suggesting a significant portion of the refinancing need belongs to China alone, which relied greatly on short maturities to fund their zero COVID‑19 policies. Both Asia and Europe have relatively a low share of debt due in 2023, constituting 14% and 10%, respectively, of their total outstanding debt.

It is worth noting that the maturity of this substantial amount of debt will occur concurrently with the unwinding of major AE central banks’ balance sheets (see Chapter 1). Although EMDE central banks have engaged only mildly in bond purchase programmes and predominantly only during the COVID‑19 crisis (Aguilar and Cantú, 2020[14]), foreign investors account for a substantial share of the investor base for EMDE bonds. Thus, EMDEs will likely compete for foreign funding at a time when the supply of AEs’ government bonds will increase. As many of these bonds have long maturities, the capacity of the market to buy duration risk,16 which is directly proportional to the maturity of the fixed-income security, might be insufficient to allow AEs and EMDEs to roll over their debt at the current historically high level of ATMs. And this is happening at a time when investors can obtain real positive returns by purchasing fixed-income securities from safe AEs. Going forward, this implies that EMDEs that rely on foreign investors to fund their borrowing needs will face challenges in lengthening their debt portfolio and issuing more in domestic currency. This in turn could exacerbate debt sustainability concerns.

Box 3.2. Examining Sri Lanka’s debt crisis of 2022

A combination of high exposure to international markets and macroeconomic shocks affected Sri Lanka

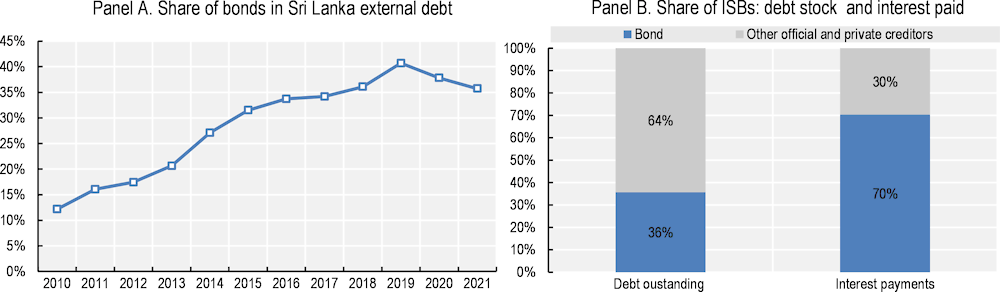

Sri Lanka faced a debt crisis in April 2022, predominantly due to its substantial exposure to international sovereign bonds (ISBs) issued at high interest rates. Between 2007 and 2019, Sri Lanka issued USD 17 billion worth of ISBs,1 resulting in the public external debt stock to GDP ratio increasing from 29% in 2010 to 44% in 2021. The proportion of ISBs in Sri Lanka’s external debt stock rose from 12% in 2010 to 36% in 2021, accounting for a considerable 70% of the government’s annual interest payments in 2021 (Figure 3.10). Elevated coupon rates and the presence of traditional collective action clauses in no more than 36% of these ISBs made debt restructuring more difficult.

Figure 3.10. Gross external debt position, breakdown by instrument

Note: External Debt refers to External Debt Stock Public and Publicly guaranteed (PPG).

Source: World Bank (2023[5]), International Debt Statistics, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/international-debt-statistics#.

This high exposure to foreign markets was combined with a weak fiscal stance and external shocks, such as the COVID‑19 pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine, setting the scene for the crisis. Sri Lanka lost approximately 24% of its annual export revenue due to the halt of tourism in 2020 and 2021 and faced escalating global oil and commodity prices as a result of the war in Ukraine. The considerable cost of ISBs in outstanding debt and the diversity of bondholders’ interests complicated the government’s efforts to negotiate a restructuring or secure alternative financing options.

Addressing the crisis: the support from the IMF

To address the crisis, authorities implemented exceptional measures, including import restrictions, the balance of payment measures, a digital fuel rationing system, and scaling up social transfers with external humanitarian support. Decisive policy actions since mid‑2022 included reducing monetary financing, raising policy rates to control inflation, introducing tax measures to improve fiscal balance, increasing electricity prices, implementing automatic energy pricing mechanisms, and initiating institutional and structural reforms.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved a USD 2.9 billion Extended Fund Facility (EFF) arrangement on 20 March 2023, to assist Sri Lanka in tackling its ongoing economic crisis. This 48‑month extended arrangement aims to provide the necessary capital to fund essential imports and offer policy space for the Sri Lankan Government to stimulate economic growth and implement structural reforms.

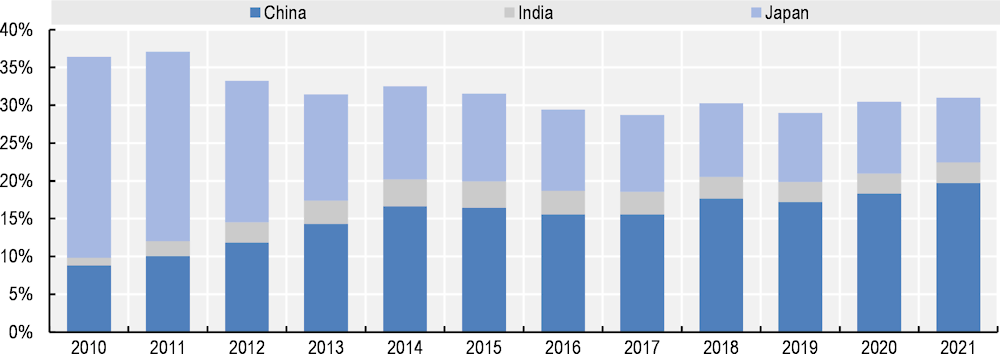

Figure 3.11. Share of Sri Lanka’s external debt held by China, India and Japan

Source: World Bank (2023[5]), International Debt Statistics¸ https://databank.worldbank.org/source/international-debt-statistics#.

The Sri Lankan EFF comes with stringent conditionalities for economic reform, such as ambitious revenue‑based fiscal consolidation to restore fiscal and debt sustainability. The IMF suggests that the Sri Lankan Government reform its tax mechanisms and manage expenditures to address persistent budget deficits, aligning spending with income. Moreover, the IMF encouraged the government to continue implementing progressive tax reforms while introducing stronger safety nets to protect the poorest and most vulnerable in the society.

Ahead of the first IMF review in six months, Sri Lanka is set to engage in debt restructuring discussions with bilateral and private creditors. The country received support guarantees from China, India, and Japan, holding more than 30% of Sri Lanka’s PPG external debt (Figure 3.11) before the approval of the IMF programme. Of these 30%, China holds roughly 20pp alone, with its share following a rising trend since 2010 (for details on the role of China as a lender see Box 3.1). The IMF programme is expected to catalyse further external funding from other multilateral organisations and inject more capital into the Sri Lankan economy, which will fund essential imports and public investments, and replenish foreign exchange reserves.

1. International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) refer to bonds issued by a sovereign government in a currency other than its own, typically to raise capital from foreign investors.

Sources: Based on IMF (2023[15]), Sri Lanka: Request for an Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility-Press Release, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/03/20/Sri-Lanka-Request-for-an-Extended-Arrangement-Under-the-Extended-Fund-Facility-Press-531191; The Diplomat (2023[16]), The Real Cause of Sri Lanka’s Debt Trap, https://thediplomat.com/2023/03/the-real-cause-of-sri-lankas-debt-trap/.

3.5. Overall credit quality of EMDEs slightly deteriorated following the record number of downgrades in Europe

3.5.1. 2022 was a year with a large number of downgrades, with most of them concentrated in six countries

Financial conditions have tightened globally, with central banks raising policy rates at a record pace. Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has spurred food and energy price increases, eroding purchasing power globally. This has made 2022 the year with among the highest ever number of sovereign rating downgrades with risks still to the downside (Fitch Ratings, 2022[17]). In this scenario, EMDEs face difficult choices as supporting the population’s purchasing power through fiscal policy can lead to an increase in borrowing costs at a time of already high policy rates and might be offset by future increases in inflation. Investors are more sensitive to EMDEs’ fiscal policy than they are to AEs’ and, thus, a simultaneous deterioration of their fiscal and financing conditions can more easily spiral, resulting in insolvency.

Two years after the 71 downgrades that were issued for 28 countries in 2020 driven by the COVID‑19 pandemic, 40 downgrades were given to EMDE sovereigns in 2022 (Figure 3.12 Panel A and B).17 As opposed to previous years, in 2022 the region which was downgraded the most was Europe, receiving 15 of 40 downgrades, followed by LAC (9) and SSA (8). Looking deeper at the composition of downgrades in 2022, the record number of downgrades given to EMDEs in Europe does not reflect a general worsening of debt quality in the whole region but rather is mainly driven by four sovereigns being downgraded by several agencies and sometimes more than once. These countries are those impacted by the war, with Ukraine accounting for five downgrades (see Box 3.3 on the Ukrainian debt management during the war) and Russia for two, while the remaining eight were split evenly between Belarus and Türkiye.18 Similarly, in Asia, six downgrades were given to only two issuers, but four times for each: Sri Lanka and Pakistan. In total, only six countries accounted for 25 out of 40 downgrades in 2022 – namely Belarus, Ghana, Russia, Sri Lanka, Türkiye and Ukraine.

Figure 3.12. Trends in EMDE sovereign credit ratings

Note: Investment grade covers ratings equal to or better than BBB- or Baa3; speculative grade covers ratings between CCC+ or Caa1 and BB+ or Ba1; and the default category covers ratings equal to or below CCC- or Caa3. For Panel C, the grade in force on 31 December of the respective year was considered.

Source: Refinitiv; and OECD calculations.

Figure 3.12 Panel C examines the distribution of EMDEs since 2019 across three rating categories: investment grade, speculative grade, and in or approaching default (i.e. ratings equal to or below CCC- or Caa3), providing valuable insights. Firstly, 62% of EMDEs fall within the speculative grade category, 30% in the investment grade, and 8% in the default category. Secondly, these figures have remained relatively stable since 2019, notwithstanding the COVID‑19 crisis, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, escalating inflationary pressures, and the deterioration of funding conditions. As a result, upgrades and downgrades primarily occurred within these categories. More specifically, countries that improved their rating category since 2019 include: Argentina (2019) and Belise (2021), which transitioned from default to speculative; and Croatia (2021), which advanced from speculative to investment grade. In contrast, Belarus (2022), Belise (2020), Lebanon (2020), Sri Lanka (2022), Suriname (2020), and Zambia (2020) shifted from speculative to default, while Colombia (2021) and Russia (2022) moved from investment to speculative grade. This implies that, despite numerous downgrades and upgrades since 2019, countries rarely lose or achieve investment grade status or exit from or enter into a default situation, even in light of significant macroeconomic and geopolitical developments.

3.5.2. Following a slight improvement in 2021, the credit quality of EMDE issuance slightly deteriorated in 2022

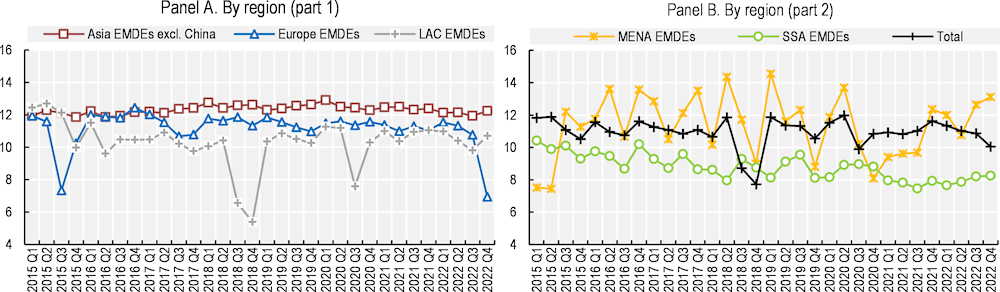

Value‑weighted sovereign credit ratings at issuance for EMDEs between 2015 and 2022 has deteriorated in 2022 relative to historical norms (Figure 3.13). Credit quality had first deteriorated in 2020, with the exception of Asia and Europe, where debt quality has remained relatively stable over time. Especially EMDEs in Asia, excluding China, have remained on average at investment grade ratings thanks to large issuers with sound credit standing (such as India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand) that dominate the region’s issuance by amounts. On the other hand, LAC and MENA experienced a sharp decline in their overall credit quality as they received most of the downgrades given to EMDEs in 2020. In addition, the weighted credit quality of SSA was not heavily affected by the significant number of downgrades given in 2020 as many issuers were effectively shut out of debt markets, concealing the effect of the downgrades.

Figure 3.13. Evolution of credit quality for a selected group of EMDEs

Note: Credit quality reflects the value‑weighted average rating of gross debt issuance at each quarter. It is not a measure for rating quality of the outstanding debt. The value of 12 in the weighted rating is equivalent to BBB or Baa and, thus, constitutes a threshold for investment grade debt issuance (Annex 3.A).

Source: Refinitiv; and OECD calculations.

In 2021, the overall credit quality of EMDEs slightly improved, driven especially by MENA and to a lesser extent by LAC; while it decreased slightly in SSA and in EMDEs in Europe. This substantial improvement in MENA credit quality in 2021 is worth explaining. In the fourth quarter of 2021, the weighted credit quality of MENA rose from around 9 to more than 12 (equivalently from BB- to BBB-), altering the status of the region from non-investment grade to investment grade. However, given that there was no upgrade given to MENA countries during 2021, this improvement in the weighted debt quality of the region was mainly due to a change in the composition of issuers and the weight of their debt. For instance, in 2020, the group of high-rating MENA countries (each having a rating of 18, equivalent to AA-), namely Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, accounted for 21% of the gross debt issuance of the region, whereas in 2021, their share increased to 29%. In the fourth quarter, the share of gross debt issued by these four high-rated countries rose to 38% with Kuwait issuing for the first time during the year, which explains the jump observed in the weighted debt quality of MENA towards the end of 2021.

In 2022, the overall debt quality of EMDEs has slightly deteriorated, mainly due to a sharp decline in the weighted debt quality of EMDEs in Europe, especially in the second half of the year. Russia and Türkiye, being the two largest issuers of the region, were downgraded a total of six times, and accounted for 39% of the total debt issued by EMDEs in Europe in 2022, which largely explains the steep fall in the weighted debt quality of the region. Asia (excluding China) continued to maintain a stable level of weighted credit quality in 2022, while MENA, after receiving four upgrades, became the region with the highest weighted rating, surpassing Asia. In addition to four upgrades, the composition of issuers also played a role in the rising average rating in the region, as the share of debt issued by high-rating MENA countries (Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) rose from 29% in 2021 to 37% in 2022.

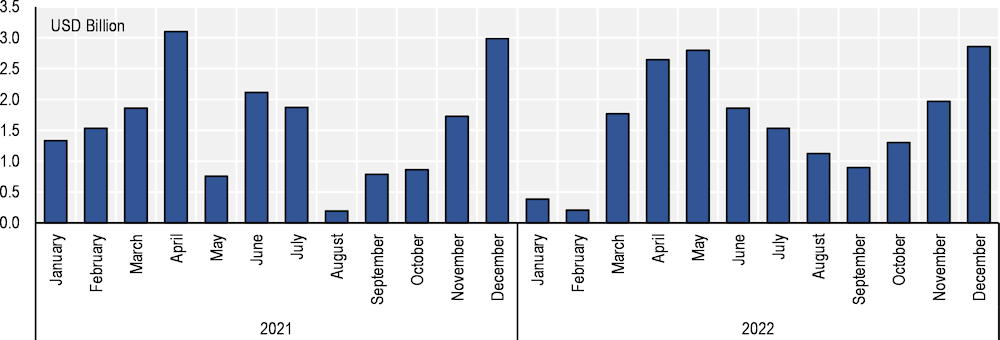

Box 3.3. How to manage debt in times of war: Ukraine experience

Debt management plans prior to the crisis were in good shape thanks to a stable economy

In a recent interview with the OECD, Yuriy Butsa, Ukraine’s Government Commissioner for Public Debt Management, provided insights on the implications of the Russian aggression on Ukraine’s public debt management and funding conditions (OECD, 2022[18]). Prior to the invasion on 24 February 2022, Ukraine’s economy was on a stable growth trajectory, characterised by a relatively low budget deficit of 3.6% of GDP in 2021, a declining debt-to-GDP ratio that had decreased from about 80% in 2016 to below 50%, and an annual GDP growth rate of 3.4%. The nation was also witnessing a recovery from the COVID‑19 pandemic, with the central bank tightening monetary policy in 2021 to curb rising inflation.

In the wake of these favourable economic conditions, Ukraine’s government funding needs for 2022 were manageable from a debt-management perspective. The government planned to meet its financing requirements through a combination of domestic debt (accounting for around two‑thirds) and loan disbursements from international financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank. The inclusion of Ukraine’s bonds in the JPM GBI-EM Index from 2022 was expected to attract more non-resident flows to the domestic market. The primary challenge for Ukraine at that time was to decide whether to borrow from external commercial sources or focus on maximising domestic market resources, given the anticipated external market backdrop.

Russia’s invasion forced Ukraine to restructure its debt and led to a sequence of downgrades

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has significantly disrupted Ukraine’s borrowing landscape and funding conditions, leading to a market panic sell-off and a considerable increase in yields on foreign currency-denominated bonds. This situation has severely limited Ukraine’s access to international capital markets, compelling the government to rely on domestic financial institutions, external donors, and the central bank in its capacity as a lender of last resort.

The country took action and decided to collaborate with creditors to restructure its debt so it could deal with extraordinary funding needs in times of war on its territory. In August 2022, the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine announced that overseas creditors backed the country’s request to freeze the country’s payments on eurobonds, accounting for 75% of Ukraine’s external debt until 2024.

Following the debt restructuring, both Fitch Ratings and Standard & Poor’s lowered Ukraine’s foreign currency ratings on 12 August. Fitch assigned a restricted default (RD) rating, while S&P assigned a selective default (SD) rating, reflecting the country’s debt restructuring. However, both agencies subsequently revised their ratings to CC (Fitch) and CCC+ stable (S&P) on 17 August and 19 August, respectively. Nevertheless, these ratings remain lower than the pre‑war B stable ratings provided by both agencies. On 10 February 2023, Moody’s downgraded Ukraine’s rating from Ca to Caa3, reflecting the heightened risks and uncertainties associated with the country’s economic and fiscal outlook following the debt restructuring.

The debt management office adopted several measures to meet funding needs

In the face of these challenges, the government has had to adapt its borrowing strategies to accommodate the increased cash needs, which are estimated at approximately USD 5 billion per month. This adaptation has led to several innovative changes in borrowing techniques. For instance, Ukraine has re‑designated its bonds as “war bonds” to support the nation during the conflict. Furthermore, the government has lowered the minimum purchase amount to 1 000 Ukrainian Hryvnia (approximately USD 34), making these bonds more accessible to a broader range of investors, including retail investors. Additionally, Ukraine has engaged with commercial banks to launch mobile applications and web-based solutions that enable individuals to participate in bond auctions more conveniently. This effort has successfully attracted 90 000 retail and business investors, demonstrating the efficacy of these initiatives.

Another strategic change has been the reduction of maximum bond maturities from five years to 1.5 years, a decision made at the request of the Primary Dealers. This adjustment reflects the difficulties in pricing long-term bonds amidst the uncertainties associated with the ongoing conflict and rising inflation. By implementing these changes, Ukraine has been able to maintain some degree of stability in its public debt management, despite the unprecedented challenges posed by the war (Figure 3.14).

Figure 3.14. Amount of the central government marketable debt issued by Ukraine

Source: Refinitiv; and OECD calculations.

By ensuring the availability of funds for social programmes, the government has also indirectly strengthened the banking sector, as increased deposits have led to improved liquidity. This improved liquidity has, in turn, enabled banks to participate more actively in the purchase of government bonds, creating a positive feedback loop that benefits both the financial sector and the government’s funding needs.

Future challenges are daunting as Ukraine needs to raise funds to reconstruct the country

Looking ahead, Ukraine faces the immense challenge of securing the necessary resources for resistance, support, and reconstruction efforts in the aftermath of the ongoing conflict. Addressing these needs requires a comprehensive funding strategy that leverages both domestic and international resources. To achieve this, the government aims to attract private investors by enhancing the credit quality of Ukrainian bonds. This could be accomplished by seeking official guarantees from other countries, which has provided such guarantees in the past. By offering credit enhancement facilities, Ukraine could decrease the risk for investors and reduce the costs associated with rebuilding the nation.

Furthermore, the government is considering issuing sustainable sovereign bonds to engage ESG-sensitive investors. By tapping into this growing market segment, Ukraine can diversify its funding sources and potentially access more cost-effective financing for its recovery and reconstruction efforts.

Sources: Based on OECD (2022[18]), Public Debt Management in Wartime: Interview with Ukraine’s Yuriy Butsa, https://oecdonthelevel.com/2022/07/04/public-debt-management-in-wartime-interview-with-ukraines-yuriy-butsa/; IMF (2023[19]), Ukraine: Request for an Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility and Review of Program Monitoring with Board Involvement-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Ukraine, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/03/31/Ukraine-Request-for-an-Extended-Arrangement-Under-the-Extended-Fund-Facility-and-Review-of-531687.

References

[14] Aguilar, A. and C. Cantú (2020), “Monetary policy response in emerging market economies: why was it different this time?”, BIS Bulletin 32, https://www.bis.org/publ/bisbull32.pdf.

[13] Debrun, X., J. Ostry and C. Wyplosz (2020), Debt Sustainability, Oxford University, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198850823.003.0005.

[7] Eichengreen, B. and R. Hausmann (1999), “Exchange rates and financial fragility”, New challenges for monetary policy, proceedings of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Jackson Hole symposium, http://www.tinyurl.com/kuwmtaw.

[8] Eichengreen, B., R. Hausmann and U. Panizza (2005), “The Pain of Original Sin, The Mystery of Original Sin, and Original Sin: The Road to Redemption”, https://eml.berkeley.edu/~eichengr/research/ospainaug21-03.pdf.

[17] Fitch Ratings (2022), 2022 Is Second-Worst Year for EM Sovereign Downgrades, https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/2022-is-second-worst-year-for-em-sovereign-downgrades-10-10-2022 (accessed on 2 April 2023).

[4] Horn, S. et al. (2023), “China as an international lender of last resort”, Kiel Working Paper 2244, https://www.ifw-kiel.de/fileadmin/Dateiverwaltung/IfW-Publications/-ifw/Kiel_Working_Paper/2023/KWP_2244_China_as_an_International_Lender_of_Last_Resort/KWP_2244.pdf.

[15] IMF (2023), Sri Lanka: Request for an Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility-Press Release, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/03/20/Sri-Lanka-Request-for-an-Extended-Arrangement-Under-the-Extended-Fund-Facility-Press-531191.

[19] IMF (2023), “Ukraine: Request for an Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility and Review of Program Monitoring with Board Involvement-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Ukraine”, IMF Country Report, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/03/31/Ukraine-Request-for-an-Extended-Arrangement-Under-the-Extended-Fund-Facility-and-Review-of-531687.

[3] IMF (2022), Wolrd Economic Outlook, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2022/10/11/world-economic-outlook-october-2022.

[2] International Monetary Fund (2023), Fiscal Monitor April 2023: On the Path to Policy Normalization.

[1] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2022: Economic and Social Impacts and Policy Implications of the War in Ukrain, OECD publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4181d61b-en.

[20] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2022 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/oecd-economic-outlook/volume-2022/issue-2_f6da2159-en.

[10] OECD (2022), OECD Sovereign Borrowing Outlook 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b2d85ea7-en.

[18] OECD (2022), “Public Debt Management in Wartime: Interview with Ukraine’s Yuriy Butsa”, OECD on the level, https://oecdonthelevel.com/2022/07/04/public-debt-management-in-wartime-interview-with-ukraines-yuriy-butsa/.

[12] OECD (2022), “The implications for OECD regions of the war in Ukraine: An initial analysis”, OECD Regional Development Papers, Vol. No. 34, https://doi.org/10.1787/8e0fcb83-en.

[11] Önder, Y. and E. Sunel (2021), “Default or depreciate”, Ghent University Working Paper, https://wps-feb.ugent.be/Papers/wp_21_1023.pdf.

[9] Onen, M. et al. (2023), “Overcoming original sin: insights from a new dataset”, BIS Working Papers No 1075.

[16] The Diplomat (2023), “The Real Cause of Sri Lanka’s Debt Trap”, The Diplomat, https://thediplomat.com/2023/03/the-real-cause-of-sri-lankas-debt-trap/.

[6] Wang, C. (2022), China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2022, https://greenfdc.org/author/christoph_nedopil_wang/.

[5] World Bank (2023), International Debt Statistics, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/international-debt-statistics#.

Annex 3.A. Methods and sources

Primary sovereign bond market data and country groupings

Primary sovereign bond market data are based on original OECD calculations using data obtained from Refinitiv that provides international security-level data on new issues of sovereign bonds. The data set covers bonds issued by emerging market sovereigns in the period from 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2022 and includes both short-term and long-term debt. The data set covers bonds issued by emerging market sovereigns in the period from 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2022 and includes both short-term and long-term debt. Short-term debt (“bills”) is defined as any security with a maturity less than or equal to 365 days but no less than 30 days, as bill issuances with a maturity less than 30 days are considered to be done for cash management purposes and excluded from calculations. The data provides a detailed set of information for each bond issue, including the proceeds, maturity date, interest rate and currency structure.

The definition of emerging markets used in this report is consistent with the IMF’s classification of Emerging and Developing Economies used in its World Economic Outlook. The regional definitions are also those used by the IMF, while the income categories used (high income, low income, lower middle income, upper middle income) are defined by the World Bank according to GNI per capita levels.

A number of bonds have been subject to reopening. For these bonds, the initial data only provide the total amount (original issuance plus reopening). To retrieve the issuance amount for such reopened bonds, specific data on the outstanding amount on each reopening date for the concerned bonds have been downloaded separately from Refinitiv. As the reopening data only provide amounts outstanding, in order to obtain the issuance amount on each relevant date, the outstanding amount on the previous date is subtracted from the outstanding amount on that given date. These calculated issuance amounts are converted on the transaction date using USD foreign exchange data from Refinitiv. To ensure consistency and comparability, the same method is used for all bonds, including those which have not been subject to reopening.

Exchange offers and certain bonds in the dataset have been manually excluded when they did not have any identifier (ISIN, RIC or CUSIP) and when they have not been able to be manually confirmed by comparing with official government data.

The issuance amounts are presented in 2022 USD and adjusted by US CPI.

Credit ratings data