Vassiliki Koutsogeorgopoulou

OECD

OECD Economic Surveys: Iceland 2023

2. Immigration in Iceland: addressing challenges and unleashing the benefits

Abstract

Immigration has increased rapidly since the late 1990s, driven largely by strong economic growth and high standards of living. By mid-2023, foreign citizens made up around 18% of the population. This has brought important economic benefits to Iceland, including by boosting the working age population and helping the country to meet labour demands in fast-growing sectors. However, there are important challenges regarding the integration of immigrants and their children that need to be addressed through a comprehensive approach, helping to make the most of immigration. Successful labour market integration of immigrants requires more effective language training for adults and an improvement in skills recognition procedures. At the same time, immigrants need more opportunities to work in the public sector and the adult learning system should be adjusted to better encompass their training needs. Strengthening language skills is key to improving the weak educational outcomes of immigrant students. Enhancing teachers’ preparedness to accommodate students’ diverse educational needs is another pre-requisite. Strengthening integration further hinges upon meeting the housing needs of the immigrant population, including through an increase in the supply of social and affordable housing.

2.1. Introduction

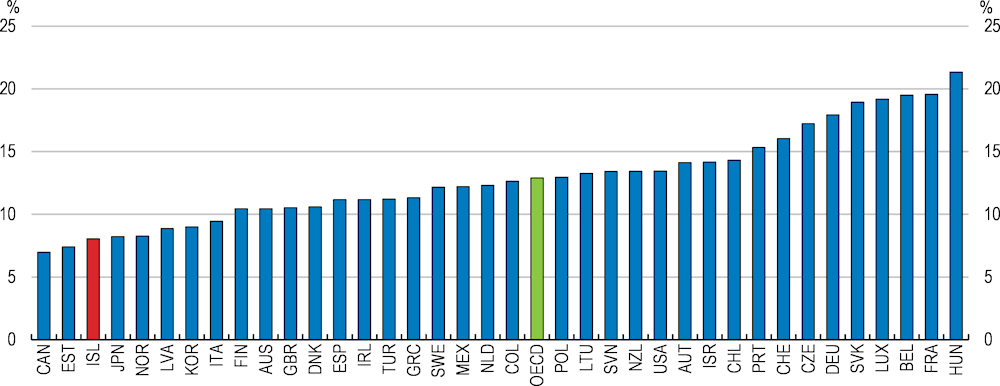

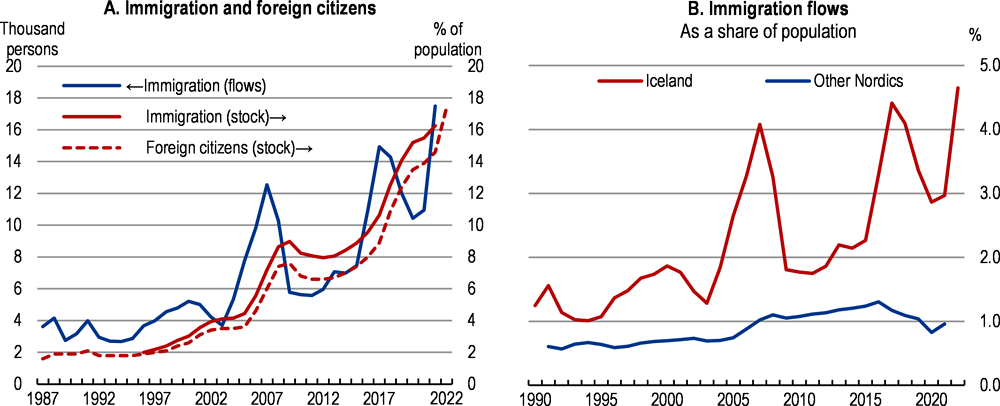

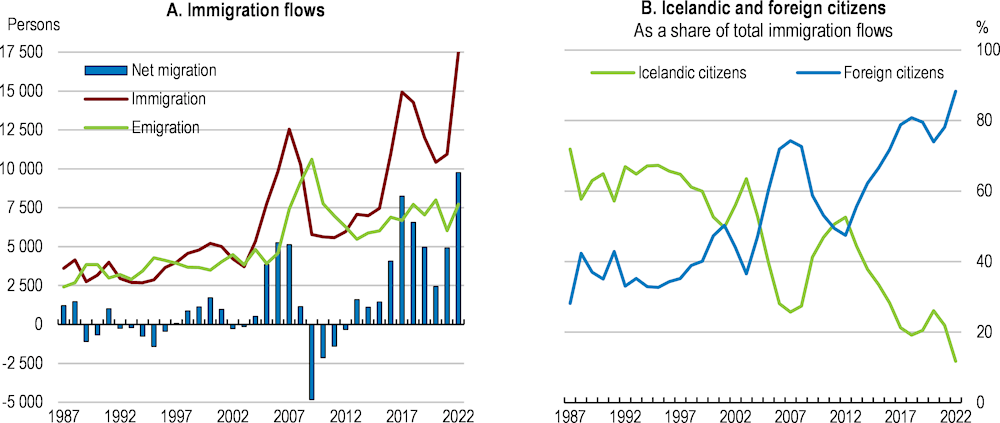

Immigration is not a new phenomenon in Iceland but has become increasingly prominent since the late 1990s, more so than in the other Nordic countries on average (Figure 2.1). Strong economic growth and high standards of living are important attractors, facilitated by the opening of Iceland’s labour market to European Economic Area (EEA) countries since the mid-1990s. The most recent waves raised the proportion of foreign citizens close to 15% of the population in 2022, compared to merely 2% in the mid-1990s, with a further increase to around 18% by mid-2023. The rapidly rising influx of immigrants and its changing geographical origins have transformed the economy through a wider variety of skills and competencies and increased population diversity. Overall, the Icelandic public has a positive view of immigration, according to a recent opinion survey covering areas such as the labour market, education, and the political and social engagement of immigrants (Ćirić, 2021[1]).

Figure 2.1. Immigration has increased rapidly

Note: In Panel A, data on immigration refer to immigration flows in Iceland, including both Icelandic and foreign citizens who obtain a residence permit or a work permit for a period exceeding three months. Foreign citizens refer to overall number of individuals that live in Iceland and do not hold Icelandic passports. Latest data point for foreign citizens correspond to 2023 first quarter. In Panel B, the other Nordics include Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. It is computed as simple average of immigration flows as a share of population in the countries depicted in the panel.

Source: Statistics Iceland; and Nordic Statistics database.

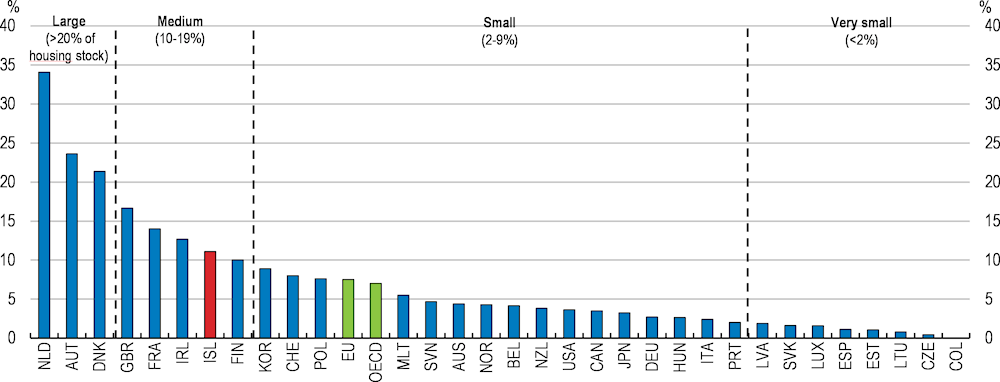

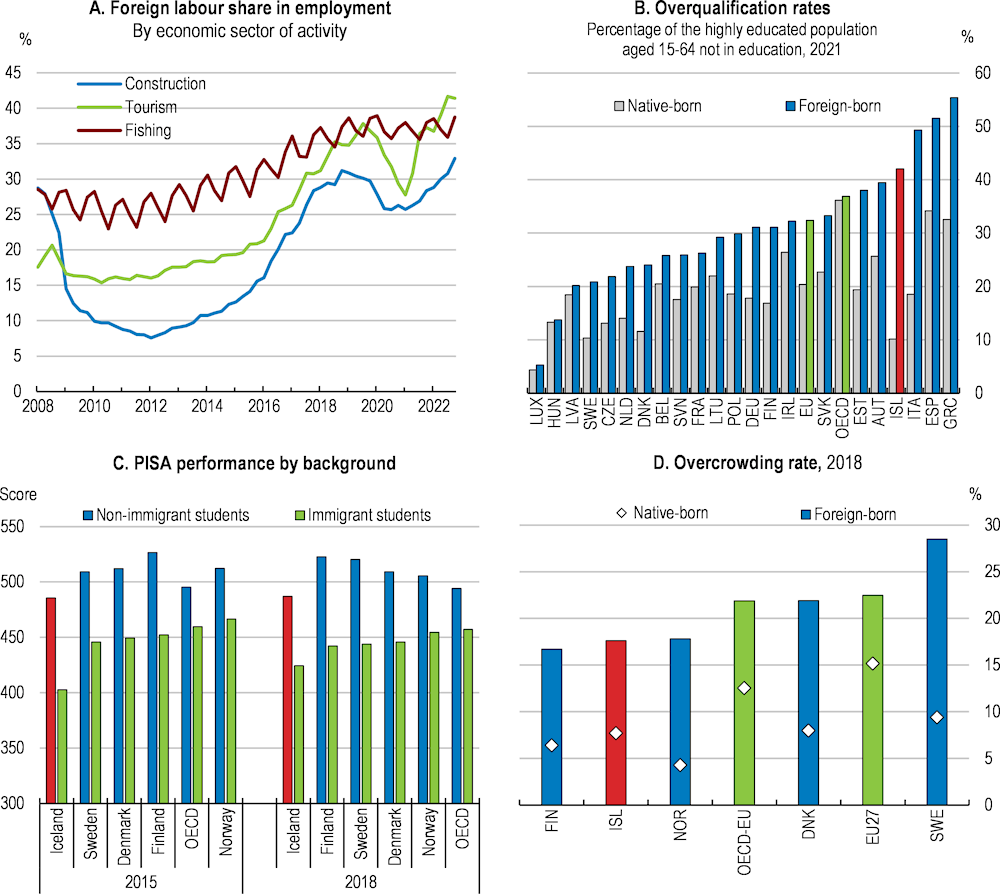

Immigration plays an important economic role, affecting performance through multiple channels. It yields visible demographic benefits not only by contributing largely to growth in the workforce, helping to alleviate pressures from shrinking native workforce, but also by changing the age structure of the population, since immigrants are in general younger than natives. Moreover, immigrant workers fill important niches in the labour market, contributing significantly to fast-growing sectors such as tourism and construction, and they increase labour market flexibility (Figure 2.2). By supplementing the human capital of the native workforce, immigrants also help to augment Iceland’s productive capacity. Indeed, empirical estimates point to a positive productivity impact from an increase in net migration, especially in the long run, which exceeds the OECD average (Boubtane, Dumont and Rault, 2016[2]). Simple scenario analysis by OECD (described below) also suggests significant output gains from net migration in the long run.

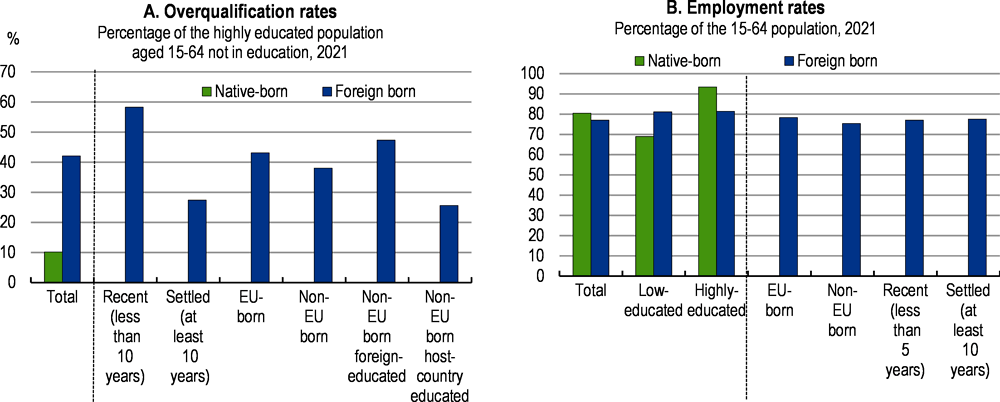

Figure 2.2. Immigration comes with benefits and challenges

Note: In Panel A, data come from the Labour Force Register. The over-qualification rate is the share of the highly educated (ISCED Levels 5-8), who work in a job that is ISCO-classified as low- or medium-skilled (levels 4-9). In Panel C, immigrant students include both first- and second-generation. In Panel D, the overcrowding rate is the share of the population living in a household that does not have an appropriate number of rooms at its disposal.

Source: Statistics Iceland; OECD, “Settling In 2023: Indicators of Immigrant Integration”; OECD, PISA 2018 database; and Eurostat – Living Conditions Survey.

However, immigration also poses policy challenges related to the integration of immigrants and their children. A much larger proportion of immigrants are over-qualified compared to natives, implying that many workers with a foreign background do not manage to translate their educational qualifications into good labour market outcomes (Figure 2.2). There are also important challenges for the education system in view of the poor educational performance and the diverse needs of students with a foreign background. Increased demand for affordable housing in a tight market adds to these challenges. Immigrants face high housing costs and tend to live in overcrowded dwellings.

This chapter discusses the economic role of immigration in Iceland focusing on the labour market, education and housing, as well as relevant integration issues in these areas, and identifies reform options to make the most of immigration. The chapter first discusses immigration patterns, putting them in an international context. This is followed by a discussion of immigration policy with an emphasis on labour markets. The subsequent sections focus on policies to better integrate immigrants and help them and their children to meet their potential. These include measures to enhance the labour market integration of immigrants by enabling them to better use the qualifications they obtained abroad and to strengthen their skills through work experience and lifelong learning, as well as measures that improve the outcomes of immigrant students, including potential reforms to better prepare school and teachers to meet diverse needs. The last section focuses on reforms to address burdensome housing costs and the poorer housing conditions immigrants tend to face. The main findings and recommendations are summarised in Table 2.1 at the end of the chapter.

2.2. Immigration patterns in an international context

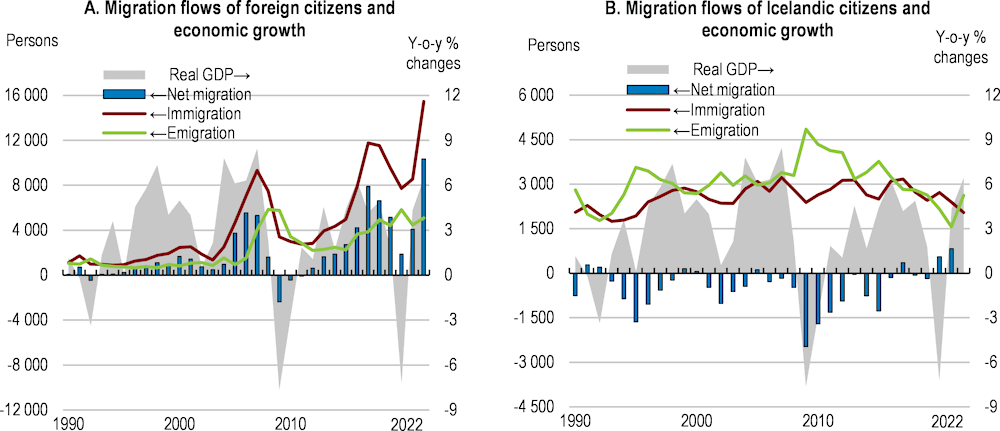

Migration inflows and outflows were roughly balanced until the late 1990s, when immigration started increasing faster than emigration (Figure 2.3). Iceland’s economic boom opened up new opportunities for foreigners in tandem with its joining the EEA in the mid-1990s, and especially the EEA enlargement to Eastern Europe in the 2000s. Foreign citizens (from EEA and third countries) accounted for around 90% of total migration flows in 2022 compared to a third in the early 1990s, with a fall in the corresponding share of returning Icelanders. The flows of migrants since the turn of the century appear to be closely related to the business cycle, a link that was much less evident in previous decades (Elíasson, 2017[3]). Inflows were particularly strong in the run-up to the global financial crisis and during the post-crisis recovery, despite a slowdown during the pandemic (Figure 2.4). The estimated inflows of immigrants as a percentage of the population in 2021 were among the highest in OECD (OECD, 2022[4]).

Figure 2.3. The large influx of foreign citizens changed the migration landscape

Note: In Panel A, data refer to immigration flows to Iceland, including both Icelandic and foreign citizens who obtain a residence permit or a work permit for a period exceeding three months.

Source: Statistics Iceland.

Figure 2.4. Migration flows appear to be largely influenced by the business cycle

Note: In Panels A and B, data refer to immigration flows in Iceland, including both Icelandic and foreign citizens who obtain a residence permit or a work permit for a period exceeding three months.

Source: Statistics Iceland; and OECD, National Accounts database.

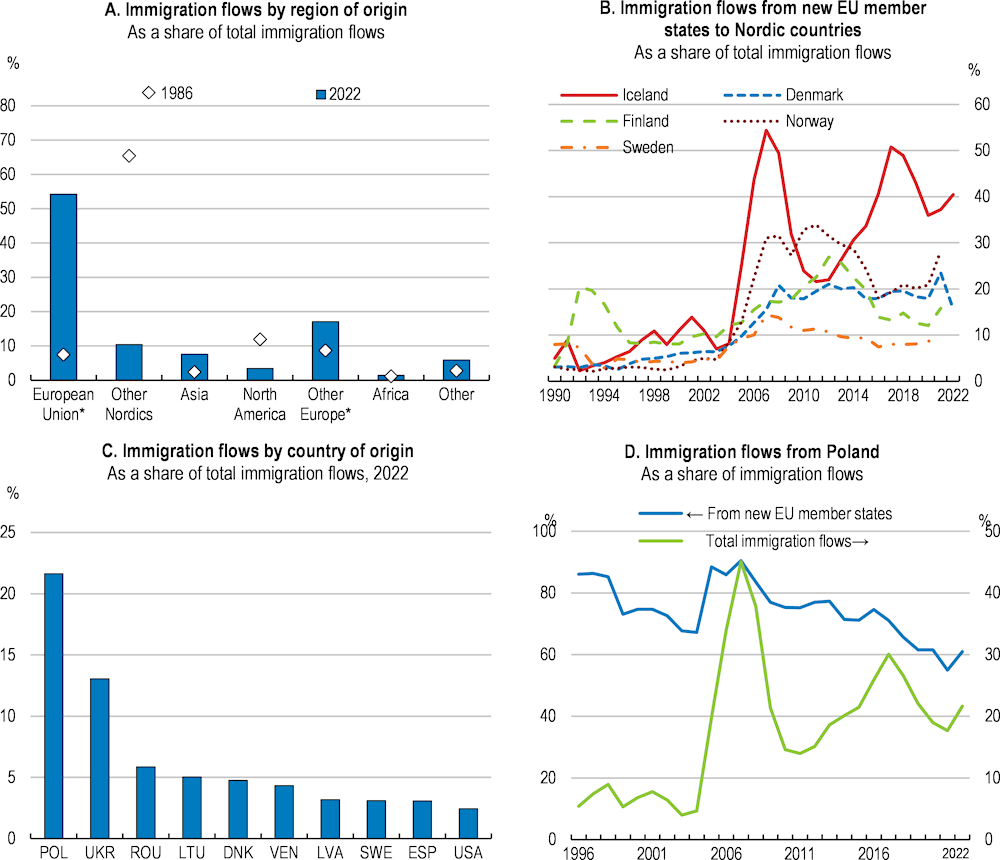

The composition of migration inflows by region/country of origin has changed over time, with the rest of Europe overtaking the other Nordic countries (Figure 2.5). In the mid-1980s, over 65% of immigrants came from the other Nordic countries and around 15% originated from elsewhere in Europe (EU and other Europe), with the pattern reversing by 2022. EU enlargements in 2004 and 2007 triggered a surge of immigration from the new member states to Iceland, above the increases experienced by the other Nordic countries. Poland is the main country of origin among the new EU member countries, followed by Romania and Lithuania. Outside the European Union, Ukraine and Venezuela account for the largest share of immigrants. An increasing number of foreigners from third countries entered Iceland over the past decade or so with refugee or other forms of protection status (Box 2.1).

Figure 2.5. The geographical diversity of immigrant inflows has increased

Note: Immigrant flows include both foreign citizens and returning citizens from the former host country. Panel A: data referring to the other Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden) are not included in the EU and “other Europe” groups. Panel B: data refer to individuals from new EU member states registered in the country as immigrants during the year. New EU member states refer to 12 new EU entrants since 2004.

Source: Statistics Iceland; and Nordic Statistics database.

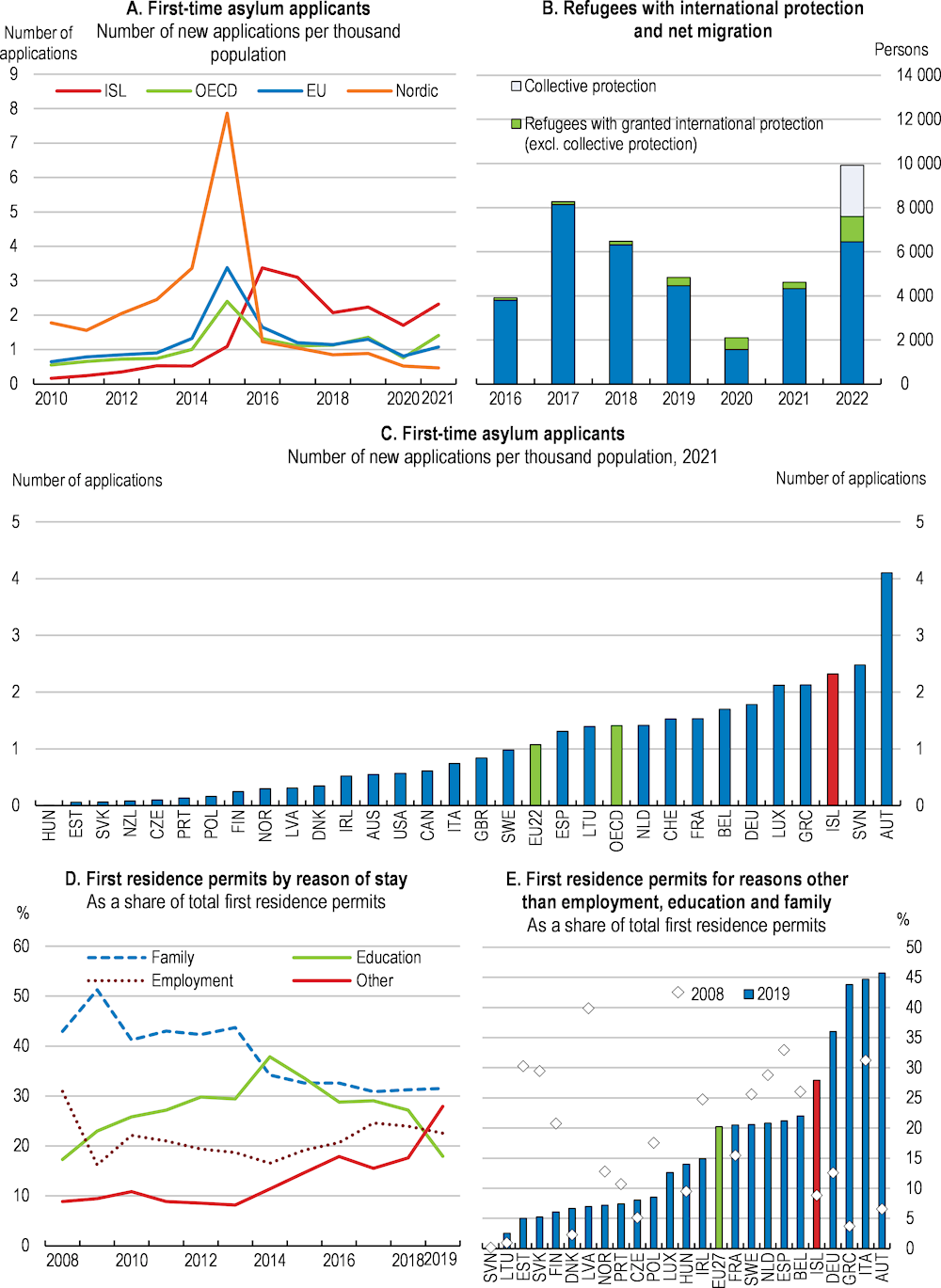

Box 2.1. The number of applicants for international protection has increased in recent years

The number of new asylum applications (per thousand of population) has risen fast since the mid-2000s (Figure 2.6). In 2021, Iceland received more new asylum seekers than most OECD countries, including the Nordic peers, and the number rose five-fold in 2022. Refugees with international protection, including those with a temporary protection status, comprised around 35% of total net immigration in 2022, with the majority coming from Ukraine and Venezuela.

The share of immigration related to reasons including international protection has increased rapidly in recent years on the basis of first residence permits issued for non-EU immigrants (Figure 2.6). On the other hand, the number of first permits for education-related reasons has almost halved as a share of total issuances between 2014 and 2019, while permits issued for employment-related reasons increased mildly without however reaching their 2008 level. Family-related reasons remain the largest category of first resident permits, accounting for around a third of the total in 2019, but the share has declined compared to its 2009 peak.

Figure 2.6. Inflows of refugees and asylum seekers increased sharply

Note: In Panel B, collective protection corresponds to temporary protection status as defined by Foreign National Act (80/2016) article 44. In Panels D and E, first residence permits for over three months are included, the category “other” refers to the first residence permits issued to asylum claimants, unaccompanied minors, to victims of trafficking and for other humanitarian reasons.

Source: OECD, International Migration database; Directorate of Immigration; Statistics Iceland; Ministry of Finance; and Eurostat.

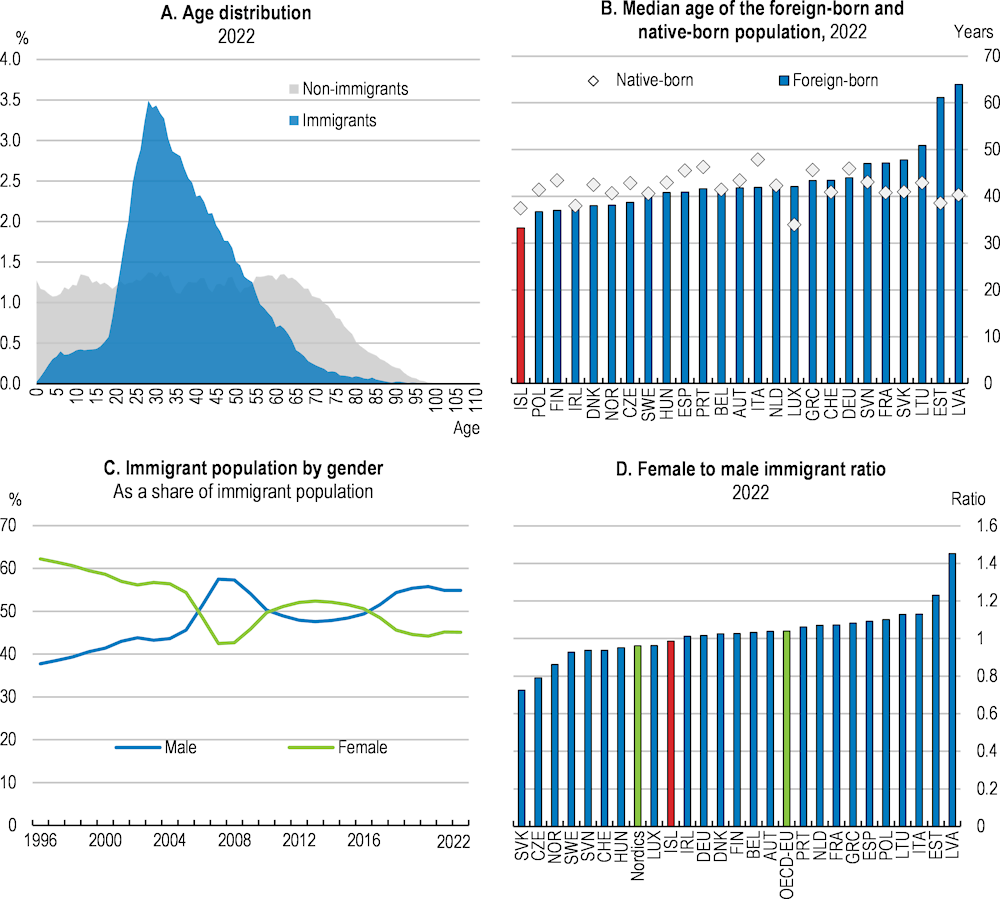

Immigrants are predominately young, with almost equal shares of men and women. The age distribution of the immigrant population is centred around younger groups within the working age population compared to a relatively flat distribution in the case of natives. The median age of the foreign-born population is the lowest in the EU area (Figure 2.7). Immigrants of prime age (25-54 years), with large work potential, accounted for over 70% of their population in 2022, against around 40% for natives. There were more women than men in the immigrant population until 2005, but the pattern has become more balanced since, probably reflecting an increase in jobs that are traditionally occupied by men (Statistics Norway, 2022[5]). In 2022, the female-to-male immigrant ratio was on par with the average of the other Nordic countries.

Figure 2.7. Immigrants are mainly young, with a balanced gender distribution

Note: In Panel A, population data are as of 1 January 2022. According to Statistics Iceland, an immigrant is defined as an individual who was born abroad, with both parents and both grandparents born abroad. Otherwise, a person is referred as native. In Panel B, data refer to population as of 1 January 2022 for all countries. Median values were imputed based on Eurostat age-distribution interval data. In Panel C, Statistics Iceland’s definition of an immigrant is used, and data are reported as of 1 January 2022. In Panel D, an immigrant is defined as an individual who was born abroad. Data are reported as of 1 January 2022. Nordic average refers to the simple average for Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. OECD-EU refers to the simple average of OECD member countries that are EU members.

Source: Statistics Iceland; and Eurostat.

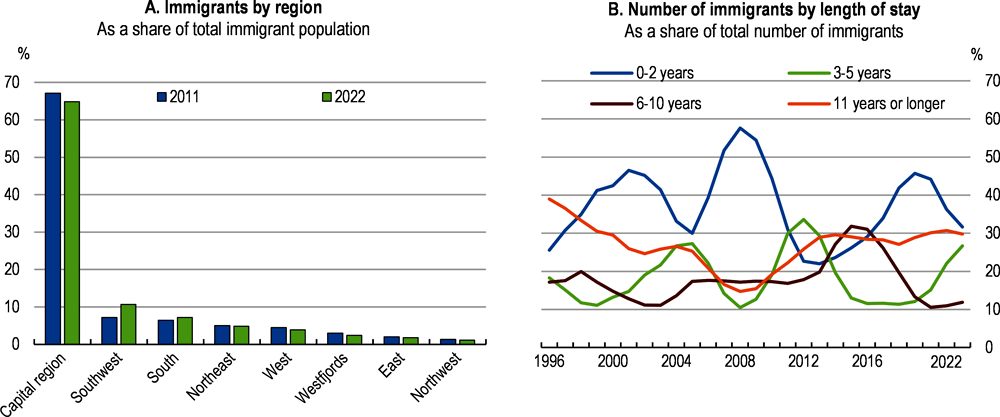

Immigrants are not distributed equally among regions. In 2022, around 65% of the immigrant population were living and worked in the capital area, a pattern that has remained broadly unchanged over time and is in line with that of the total population (Figure 2.8). Immigrants tend to concentrate in areas where tourism and construction jobs are available. An increasing share of immigrants has been staying for over five years.

Figure 2.8. Immigrants tend to live in the capital area and more have been staying longer

Note: In Panel A, immigrants include both first and second-generation immigrants. In Panel B, an immigrant is defined as an individual who was born abroad, with both parents and both grandparents born abroad. Data are reported as of 1 January 2022.

Source: Statistics Iceland; and Nordic Statistics database.

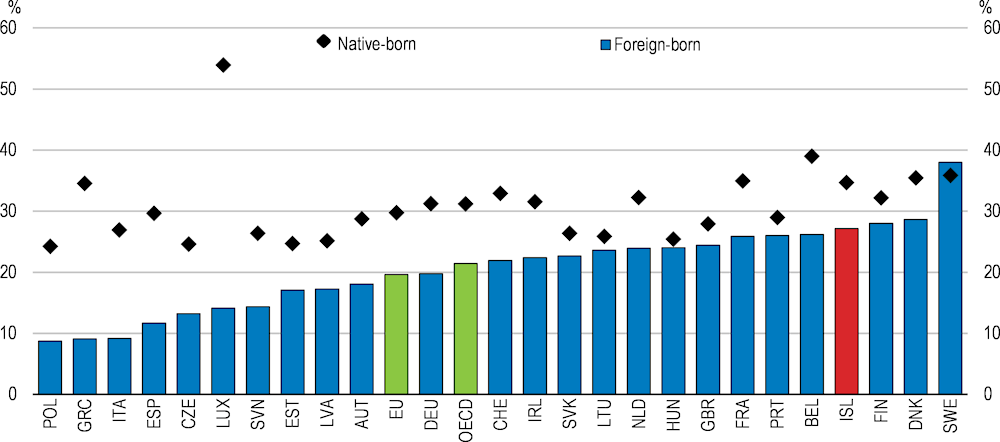

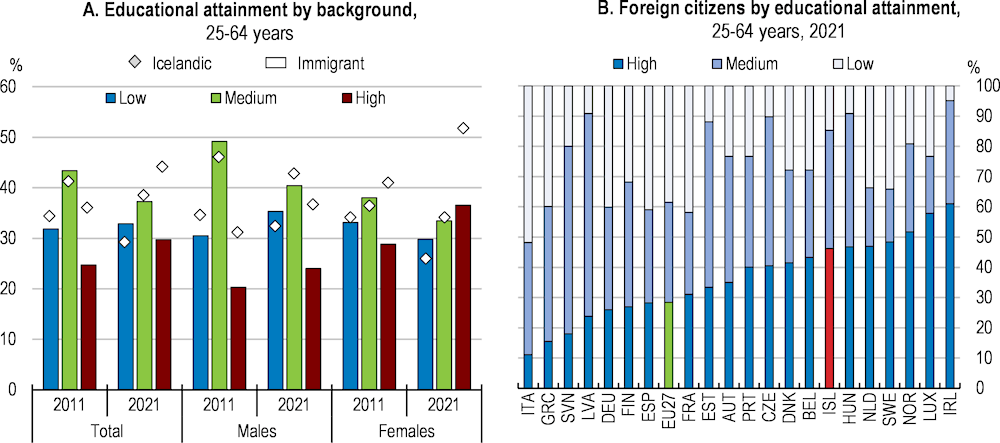

Moreover, immigrants are on average less educated than natives. The share of immigrants with tertiary education has increased over time but remains lower than that of natives, with the difference between the two groups having increased (Figure 2.9). At the same time, the share of immigrants with a basic level of education remained broadly the same between 2011 and 2021, while it declined by over 6 percentage points in the case of natives. Within the immigrant population, women tend to be better educated than men, an attainment gap that has increased over time. This may reflect the higher concentration of immigrant men in sectors requiring lower skills (see below). By international comparison, Iceland tends to host better educated immigrants than the EU countries on average, although it lags Sweden and Norway.

Figure 2.9. On average, immigrants have lower educational attainment levels than natives

Note: Low educational attainment refers to less than primary, and lower secondary education (ISCED levels 0-2), medium educational attainment refers to upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED levels 3 and 4), and high educational attainment refers to tertiary education (ISCED levels 5 and 8). In Panel A, low, medium, and high educational attainment shares may not add up to 100% due to rounding errors and omission of a “not specified” category.

Source: Statistics Iceland; and Eurostat.

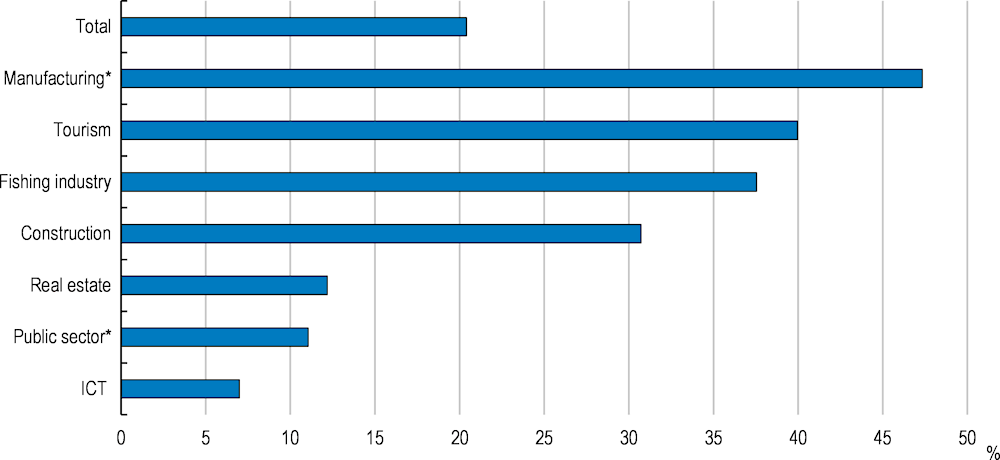

Immigrant workers are over-represented in low-skill, labour-intensive sectors. In 2022, immigrants accounted for over 20% of total employment with important contributions to fast-growing sectors such as tourism, fishing and construction, where they filled between 30% and 40% of the available jobs (Figure 2.10). These sectors are highly volatile. The tourism industry, for instance, was adversely affected by the lockdowns and travel restrictions during the pandemic, fueling large increases in unemployment among immigrants (Government of Iceland, 2022[6]). On the other hand, the share of foreign workers in higher tech activities is low. In the ICT sector, in particular, immigrants accounted for less than 10% of total employment in 2022, but recently-adopted legislation should facilitate the recruitment of foreign experts (see below).

Figure 2.10. Immigrants are concentrated in low-skill sectors

Share of immigrants in employment by economic sector of activity, 2022

Note: In Panel A, an immigrant is defined as an individual born abroad, with both parents and both grandparents born abroad. Manufacturing here refers to manufacturing of food, beverage and tobacco and include NACE classes C10-12; fishing industries include NACE classes A03 and C102; tourism industries include NACE classes: H491, H4932, H4939, H501, H503, H511, H5223, I551, I552, I553, I561, I563, N771, N7721, N79 and division S9604; and public sector here refers to NACE classes O-Q public administration, education, health, and social activities. Data are sourced from Labour Force Register.

Source: Statistics Iceland.

2.3. Immigration policy is flexible but there is scope to attract more skilled labour

Immigration policy has been amended in recent years in response to increasing immigration. A new migration law (Act on Foreign Nationals No 80/2016) entered into force in early 2017. The law simplified, among others, the application and approval processes for the issuance of residence permits, required for non-EEA citizens (Greve Harbo, Heleniak and Ström Hildestrand, 2017[7]). It also provided for a wider range of residence permits, with a particular focus on the humanitarian aspects of immigration (Government of Iceland, 2022[8]). However, the governance of immigration and integration issues remained distinct, in legal terms and administrative terms (Box 2.2), which can result in overlapping responsibilities. Planned reforms aim to amend the system of working permits for non-EEA citizens, making it simpler and more efficient (Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. Immigration framework: main features

Responsible government agencies

Immigration and integration issues in Iceland are mainly under the responsibility of two separate ministries. More specifically, issues related to foreign nationals and citizenship affairs (border control, residence permits, international protection and visa) are under the responsibility of the Ministry of Justice, while integration, inclusion and refugee resettlement (once they have been granted international protection or been invited through the UNHCR Resettlement Scheme) are under the responsibility of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour.

The Multicultural and Information Centre has played a key role in recent years, along with the municipalities, in providing assistance and counselling to immigrants. A March 2023 law has merged this Centre with the Directorate of Labour with the objective to enhance coordination, efficiency and synergies with regard to issues related to immigration, integration, social inclusion and refugee resettlement.

The Immigration Council is an intergovernmental body that advises the Minister of Social Policy and Labour on policy, implementation and monitoring of the Immigration Policy and promotes collaboration and coordination between the ministries, local authorities and other relevant stakeholders

Framework for labour immigration: issuance of temporary work permits for non-EEA nationals

While nationals from a European Economic Area (EEA) country do not need a permit to work in Iceland, non-EEA nationals are required under existing legislation (Foreign Nationals’ Right to Work Act No. 97/2002) to have a work permit prior to arrival in Iceland, which is usually a pre-condition to be granted a residence permit. Employers must submit an application for a work permit to the Directorate of Immigration. The Directorate of Labour decides whether to approve or reject the application.

There are seven categories of temporary work permits. These can be grouped into permits granted to individuals on the grounds of labour market needs and permits that accompany the individual’s residence permit. The first group includes permits that are obtained for jobs that require specific expertise (Article 8), due to labour market shortage (Article 9), service provision from a foreign provider (Article 15), and permits granted to foreign athletes and coaches (Article 10). The second group consists of work permits for students (Article 13), on the grounds of family reunification (Article 12), and due to special circumstances (Article 11), such as residence permits on humanitarian grounds.

There are several conditions for the granting of temporary work permits. These include the fulfilment of a labour market test in the case of permits granted on the grounds of labour market shortages, when this is deemed necessary by the Directorate of Labour on the basis of labour market evaluation. In cases where a labour market test is deemed to be necessary, the employer is requested to advertise the job via the EURES job search portal, which enables the Directorate to gather information on the supply of labour domestically and within the EEA.

For all categories of temporary work permits (apart from the ones for service contracts) applicants must obtain the opinion of the relevant labour union. The union provides guidance when the employment contract does not meet the minimum requirements of the relevant collective bargaining agreements and relevant labour legislation. In addition, the employment contract must be signed between the foreign national and employer

A recent draft bill proposes changes in the system of working permits for non-EEA citizens to make it simpler and more efficient. The envisaged amendments include an extension of the duration of temporary permits for foreign experts from two years under current legislation to four years. In addition, spouses of experts will no longer need a work permit to enter the labour market. The daft bill further proposes to allow foreign students to stay in the country after their graduation from Icelandic universities for up to three years, as against six months currently. They will be able to work part time (up to 60%) and bring their families while studying.

Source: Directorate of Labour; (Government of Iceland, 2022[8]); (Greve Harbo, Heleniak and Ström Hildestrand, 2017[7]).

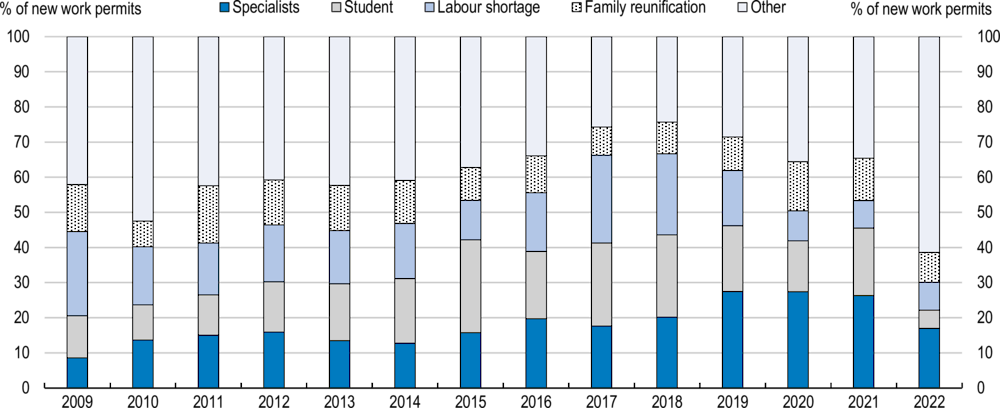

Increased immigration flows since the turn of the century appear to have been handled flexibly, providing Iceland ample scope for meeting seasonal and cyclical variations in labour demand. There are no restrictions for citizens from EEA countries, who account for the vast majority of immigrants, to enter the Icelandic labour market, but the law requires a temporary work permit for third-country nationals. There are several conditions for the granting of such temporary work permits for non-EEA nationals, including a labour market test (Box 2.2). However, tight labour markets might have effectively reduced the impact of labour market tests and other legislative requirements for non-EEA workers. Official estimates indicate high approval rates for all types of temporary work permits for third country workers, with the average approval rate exceeding 90% over the past ten years. The share of temporary work permits for foreign specialists in issuances has increased considerably since 2009 (Figure 2.11)

Figure 2.11. The issuance of temporary work permits has increased in recent years

Types of new work permits, as a share of total new work permits

Flexibility is important in view of skills shortages, so that workers from third countries can help meet demand and supplement the labour resources provided by EU/EEA immigrants. However, the skill mix can be strengthened by attracting more foreign specialists in view of shortages in frontier sectors, notably ICT. The government provides tax incentives on a case by case basis to foreign and Icelandic immigrated specialists in the form of a 25% income tax reduction for the first three years of employment of such workers, subject to certain conditions, but the system lacks transparency. Preferential tax schemes for foreign workers have become increasingly common in OECD countries, although their design differs (OECD, 2011[9]; Timm, Giuliodori and Mulle, 2022[10]; OECD, 2023[11]). However, research on the effectiveness of such schemes in terms of migration response and their economic impact is limited, making it difficult to derive clear conclusions. Focusing on the tax incentives for highly skilled migrants in the Netherlands, a recent study infers that the preferential tax scheme was effective in attracting more skilled immigrants (Timm, Giuliodori and Mulle, 2022[10]). Increased transparency and predictability of the application process and eligibility rules in the context of a major reform of the scheme in 2012 appear to have played a crucial role in this respect.

A new law facilitates the issuance of work permits for foreign specialists. An important change, in this regard, is that the proposed provisions do not condition the issuance of work permits on specific educational qualifications but rather on specialised knowledge that is in short supply in the country. It is also proposed that the government publishes a shortage occupation list for jobs requiring specialised knowledge, which would be updated regularly. The reform goes in the right direction. Implementation will help Iceland to reduce labour shortages in frontier sectors, notably ICT. A swift adoption of the draft bill proposing an extension of the duration of residence and work permits for foreign experts from two to four years (Box 2.2) is also of high importance in attracting foreign experts. At the same time, the effectiveness of the tax incentive scheme needs to be regularly monitored and assessed. Fast-track procedures for skill certification would accelerate the entry of skilled immigrants into shortage occupations (see below).

Proposed legislative changes aim to further increase the attractiveness of studying in Iceland including by allowing foreign students to stay in the country for up to three years after graduation, as against six months currently (Box 2.2). This is an important step towards facilitating the labour market integration of non-EEA students and promoting knowledge transfer. Over 15% of all students at Icelandic universities are of a foreign origin with the majority coming from third countries. The government should consider, in this context, introducing university fees for students from outside the EEA, as all the other Nordic countries have done.

2.4. The economic impact of immigration is closely related to integration

2.4.1. The impact of immigration on GDP per capita

Immigration plays an important economic role. It impacts GDP per capita by affecting demographic trends and changing the age structure of the population as, on average, immigrants are younger than natives, and through its impact on labour productivity when there are complementarities between the skills of immigrant and native workers. Immigrants arrive with skills and abilities that can supplement the human capital of the host country, contributing to innovation and productivity growth. Indeed, empirical research shows that immigration can affect human capital in the host country directly, if foreign nationals have high educational attainment, or indirectly by incentivising natives to invest in education (Portes, 2018[12]). Cross-country evidence suggests that immigration is likely to have a positive impact on GDP per capita, including in the case of Iceland, especially in the longer term, although the findings do not capture the changes in the composition of Iceland’s immigrant population observed in recent years (Box 2.3).

Box 2.3. Empirical evidence on the growth effects of immigration

Empirical research on the impact of immigration on the economy focuses on productivity and GDP per capita. The main findings of some comparative studies are as follows:

(Boubtane, Dumont and Rault, 2016[2]) estimate the impact of migration on economic growth for 22 OECD countries over the period 1986 to 2006, taking into account the skill composition of foreign immigrants. They report a positive relationship between migrants’ human capital and GDP per capita, with the estimated magnitude varying widely across countries. For Iceland, in the short run, an increase of 50% in the net migration rate of foreign-born migrants boosts economy-wide productivity by six-tenths of a percentage-point per year, with a long-run effect at 4.4% per year. In both cases, the estimated impact is over twice the average of the OECD countries considered by the analysis.

Other studies also show that immigration has a beneficial effect on economic growth in the longer term. Research by (Brunow, Nijkamp and Poot, 2015[13]), for instance, covering 36 rich countries with high immigration rates, concludes that net migration has a positive effect on GDP per capita with a lag of two decades. Exploring the longer-term impact of migration for 18 advanced countries, (Jaumotte, Koloskova and Saxena, 2016[14]) find that immigration boosts GDP per capita in host countries, operating mainly through labour productivity, with a 1% increase in the migrant share of the adult population raising GDP per capita by approximately 2% in the long run. When looking at the impact of migrants by skill level, the study concludes that both high- and low-skilled immigrants contribute to productivity, in part due to complementarity effect. The dividends from immigration appear to be broadly shared, according to the authors.

A recent study by (d’Albis, Boubtane and Coulibaly, 2019[15]) assesses the dynamic effects of an exogenous migration shock on the economy and the public finances. The results of a panel analysis of 19 OECD countries over the period 1980-2015 show that a migration shock that increases the net flow of migrants by one incoming individual per thousand inhabitants raises GDP per capita by boosting both labour supply and employment. According to these estimates, the impact on GDP per capita is 0.25% in the year of the shock and peaks at 0.31% the year after.

2.4.2. Labour market impacts

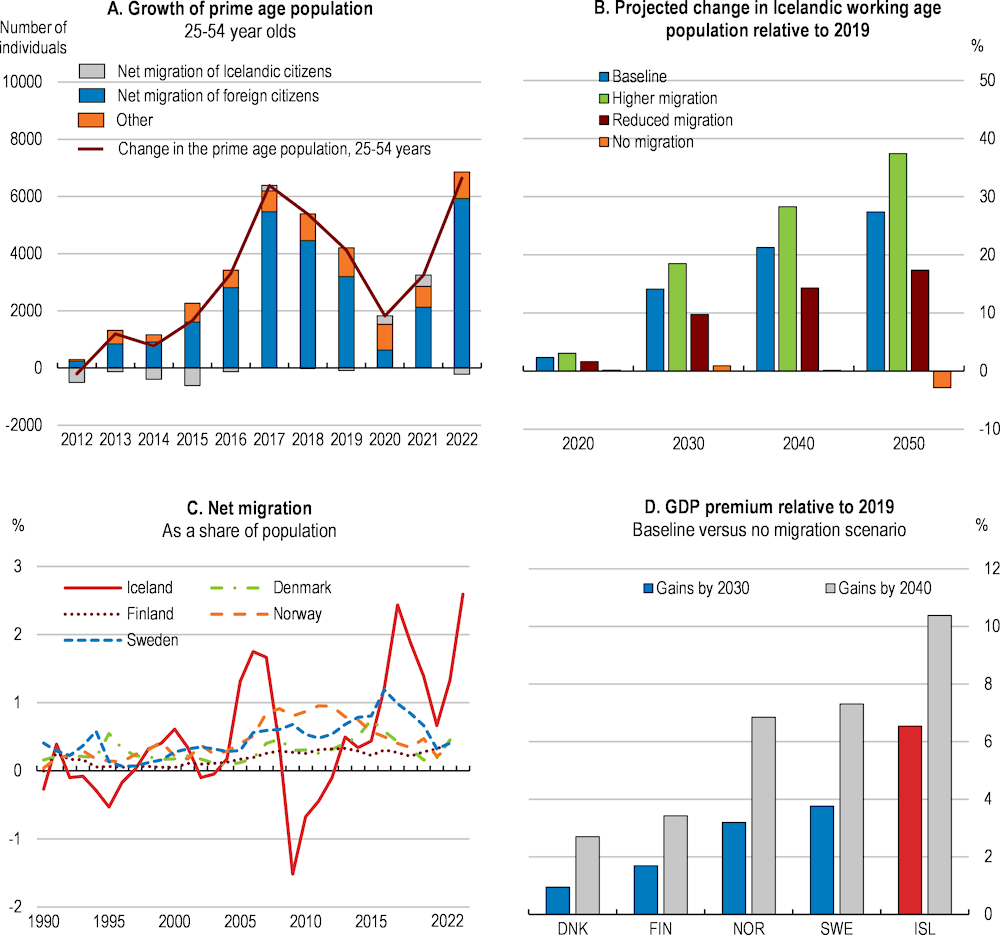

Increased inflows of immigrants has yielded important demographic benefits to Iceland, with foreign citizens contributing largely to growth in prime age population (Figure 2.12, Panel A), while helping to address the adverse impact of population ageing. This is particularly important in the fast-growing sectors of the economy. Without continued net migration, Iceland’s working age population would shrink by a cumulative 5% by 2050 (Figure 2.12, Panel B), according to OECD calculations, with clear benefits, on the other hand, from higher immigration in the years to come. Simple scenario analysis suggests significant output gains from net migration in the long run: real GDP for Iceland would be about 6.5% higher by 2030 and 10.4% by 2040 compared to a scenario with no further net immigration (Figure 2.12, Panel D). The effect is higher for Iceland than for the Nordic peers, given the current high net immigration relative to its population.

Figure 2.12. Immigration yields large demographic benefits

Note: In Panel A, net migration of foreign and Icelandic citizens refers to the age group 25-54, corresponding to the change in prime age population. The ‘other’ category refers to citizens not covered by the definition in Panel A, such as individuals that became adults in reference year. In Panel B, population projections illustrate hypothetical developments of the population size and its structure at a national level based on assumptions explained below. ‘Baseline’ scenario corresponds to keeping current demographic trends and net migration at 2019 levels. ‘Higher’ (‘reduced’) migration scenario corresponds to 33% higher (lower) than in the baseline net migration assumptions per each year. In the ‘no migration scenario’ net migration is set to zero. In Panel C, migration flows include both citizens and non-citizens of respective countries that obtain a residence permit or a work permit for a period exceeding three months and are settling in the destination country. In Panel D, calculations estimate the effect of expanded labour supply on GDP based on ‘baseline’ and ‘no migration’ scenarios presented in Panel B.

Source: Statistics Iceland; Eurostat, Population Projections; Nordic Statistics Database; and OECD, National Accounts database.

Immigration has also added to the flexibility of the Icelandic labour market in view of the close relation between migration inflows and the business cycle since the turn of the century (Figure 2.4). The adjustment of the labour market during the years of the financial crisis provides some supportive evidence in this regard. Many of the foreign workers that entered Iceland in the early 2000s left the country in the wake of the crisis, contributing to proportionally greater net emigration than in previous contractions. This likely caused the unemployment rate to rise less than would have been the case without labour migration (Central Bank of Iceland, 2011[16]; Jauer et al., 2014[17]).

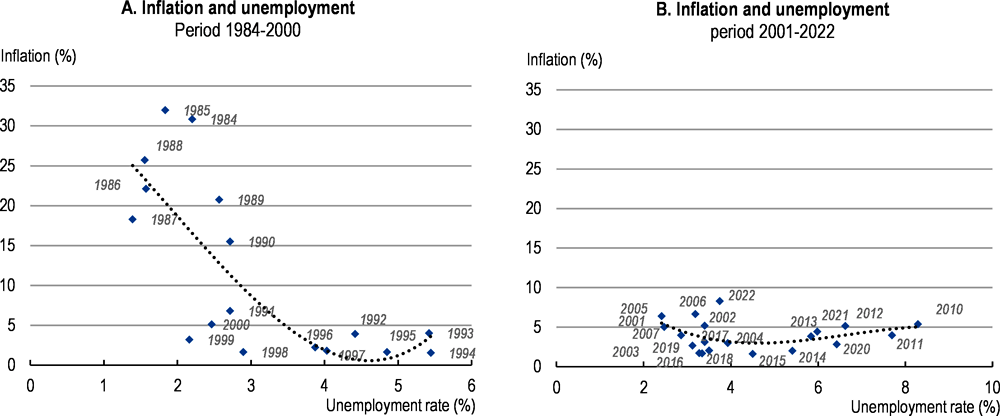

There is also evidence that, in some countries, immigration has contributed to weakening the response of inflation to economic activity. For instance, empirical evidence for Spain (Bentolila, Dolado and Jimeno, 2007[18]) and Sweden (IMF, 2015[19]) provides support in this regard. In Iceland too, the Phillips curve appears to have flattened since the late 1990s, maybe in part due to the increase in migrant inflows (Figure 2.13). Immigration may weaken the unemployment-inflation trade-off in the host country by increasing the elasticity of labour supply, which in turn has a dampening effect on wage growth (Razin and Binyamini, 2007[20]), or other channels, such as reducing the natural rate of unemployment through lower labour market mismatches (IMF, 2015[19]). Studies employing a microfounded Phillips curve further stress other labour-market channels through which immigration can affect inflation dynamics. According to the findings, increases in immigration can lower the expected marginal costs of production, leading to lower inflation for a given unemployment rate than in the absence of foreign workers (Dolado, Jimeno and Bentolila, 2008[21]). Unlike conventional models that treat labour as a homogeneous input, these studies assume some differences between immigrants and natives in terms of the determination of their wages and marginal rate of substitution between consumption and leisure (Bentolila, Dolado and Jimeno, 2007[18]).

Figure 2.13. The Phillips curve has flattened

Note: Due to being outliers, years 2008 and 2009 were excluded.

Source: OECD, Analytical database.

The impact of immigration on wages and employment in the native population is prominent in the public debate. Most studies nevertheless point to a very small impact, reflecting to a large extent skill complementarities between native and immigrant workers (Edo et al., 2020[22]; IMF, 2020[23]). However, the impact is not evenly distributed. A review of 12 studies (conducted between 2003 and 2008) for the United Kingdom, suggests that immigration has a negative impact among certain groups, notably those with lower levels of education (Ruhs and Vargas-Silva, 2020[24]). IMF research covering 22 OECD countries over the period 1995-2012 further infers that the adverse impact is felt most strongly in the young and low-skilled segments of the labour market (IMF, 2015[19]). Overall, a rise in migration results in a larger increase in unemployment for foreign-born than native workers, according to the study. Also, research on the wage effects of immigration provides little evidence that this lowers the wages of less educated native workers (Peri, 2014[25]). Nevertheless, new immigrants tend to compete more with earlier immigrants than native workers, thereby exerting a negative and slighter larger adverse impact on the wages of the former group.

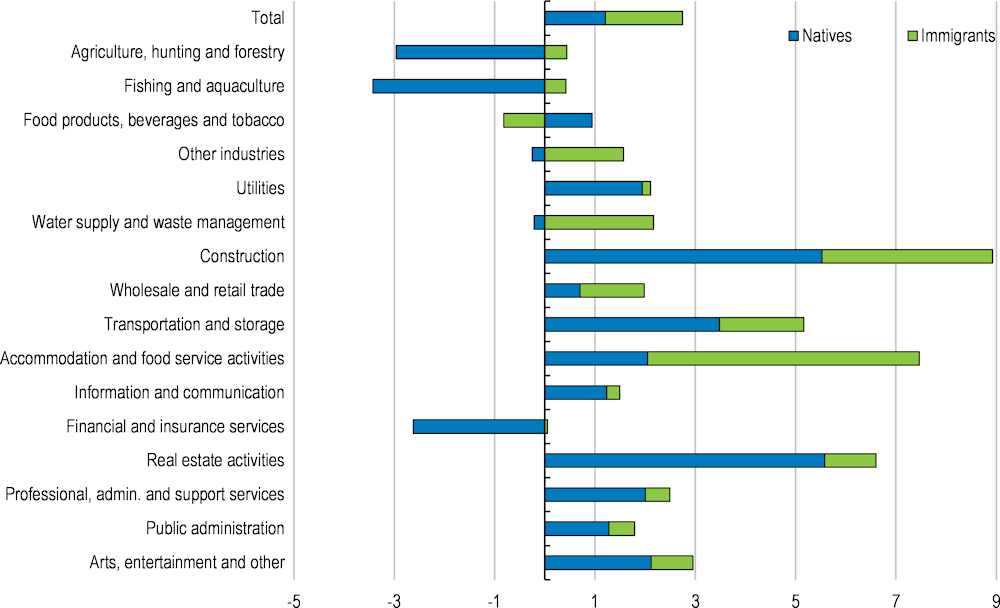

There are no specific studies analysing the impact of immigration on average wages and employment of native workers in Iceland. However, tight labour market conditions could be expected to alleviate potentially negative impacts of immigration on the employment of native workers. Moreover, as immigrant workers tend to be concentrated in low-skilled jobs, it is likely that natives move to higher-skilled jobs requiring linguistic proficiency that immigrants often lack. There are some indications, in this context, of a decline in employment of native workers over the period 2012-19 in agriculture and fishing, whereas in sectors such as real estate, transportation, ICT, as well as construction, probably at higher-skilled jobs, their employment has increased (Figure 2.14). At the same time, Iceland’s high degree of unionisation could be expected to limit the potential adverse effects on wages from increased labour supply, while the concentration of immigrants in specific sectors keep wages in such sectors stable, containing distributional consequences.

Figure 2.14. Changes in employment suggest sectoral shifts among native workers

Average annual growth in employment by sector of activity and background between 2012 and 2019

Note: According to Statistics Iceland, an immigrant refers to a person born abroad, with both parents and both grandparents born abroad. Otherwise, a person is referred to as a native. Labour data are sourced from Labour Registry.

Source: Statistics Iceland.

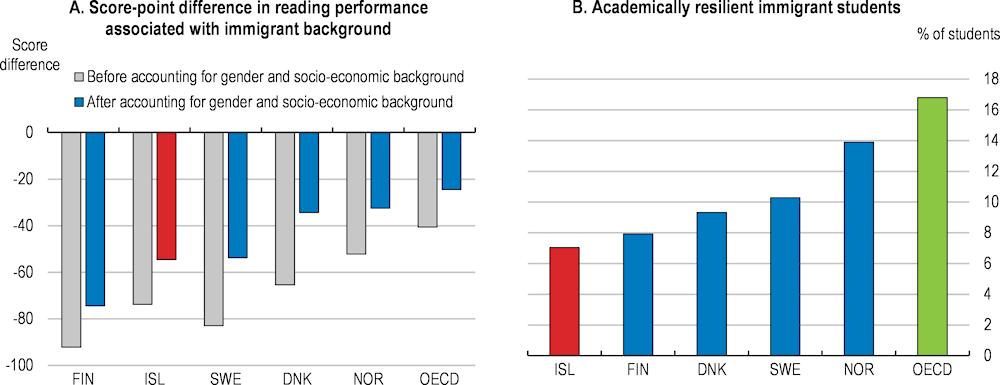

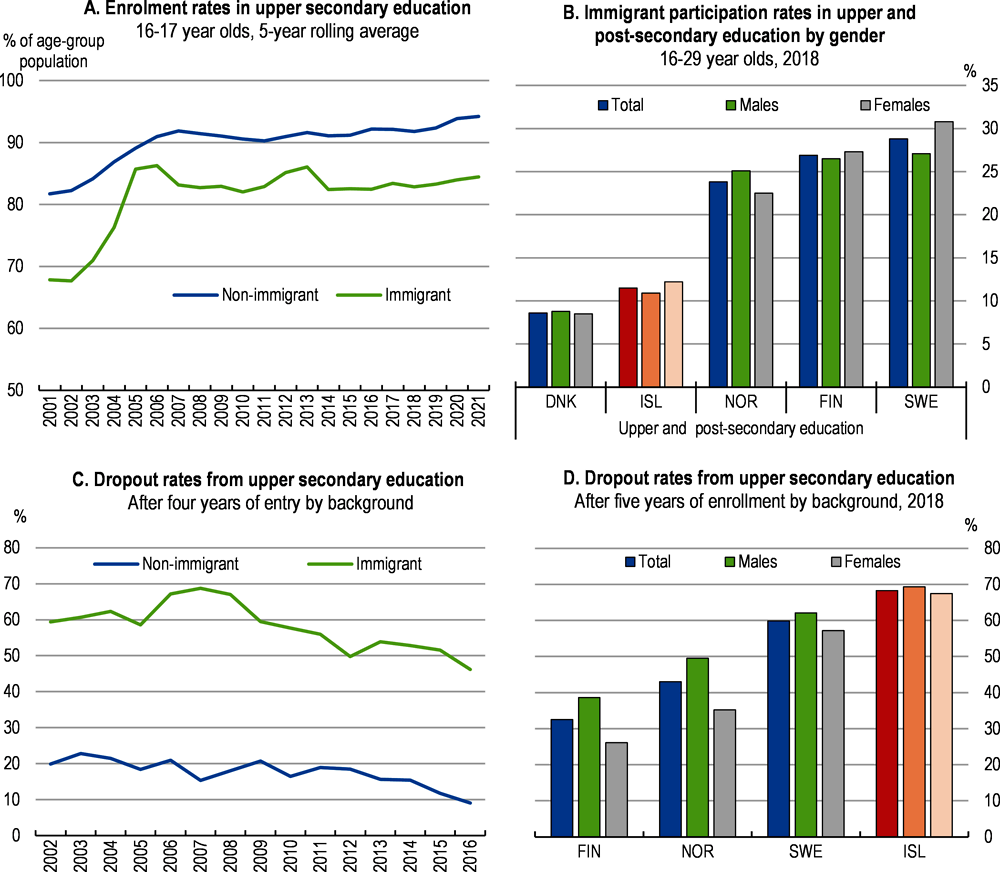

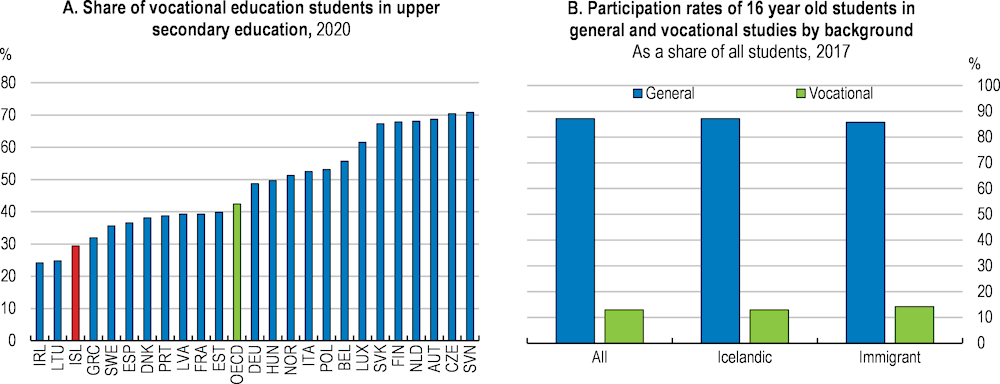

2.4.3. The impact of immigration on education

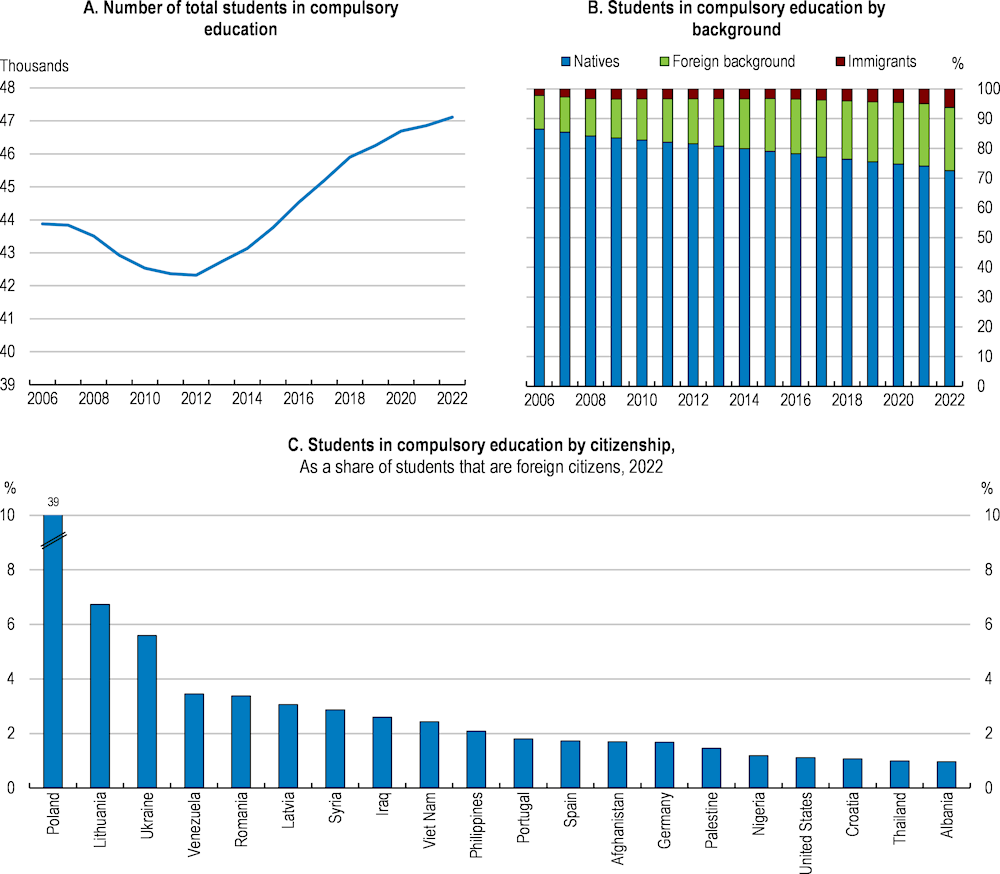

The population in compulsory education has increased steadily over the past decade driven by a rise in the share of foreign students (Figure 2.15). Immigrant students, in particular, accounted for a bit over 6% of student population in compulsory schools in 2022, three times the corresponding share in 2006. Students from Poland accounted for the largest share of foreign students, mirroring the composition of immigration.

Figure 2.15. An increasing share of students has a foreign background

Note: In Panel B, natives refer to persons with no foreign background, immigrants refer to persons born abroad, with both parents and all grandparents born abroad. Foreign background refers to individuals who are not classified as natives or immigrants.

Source: Statistics Iceland.

Increasing immigration can impact the education system in various ways, including by creating additional demand for places, posing a risk of overcrowded classes, and also through additional demand for resources in view of the diverse educational needs of students. The poor educational performance of immigrant students (discussed below) also raises qualitative challenges for schools.

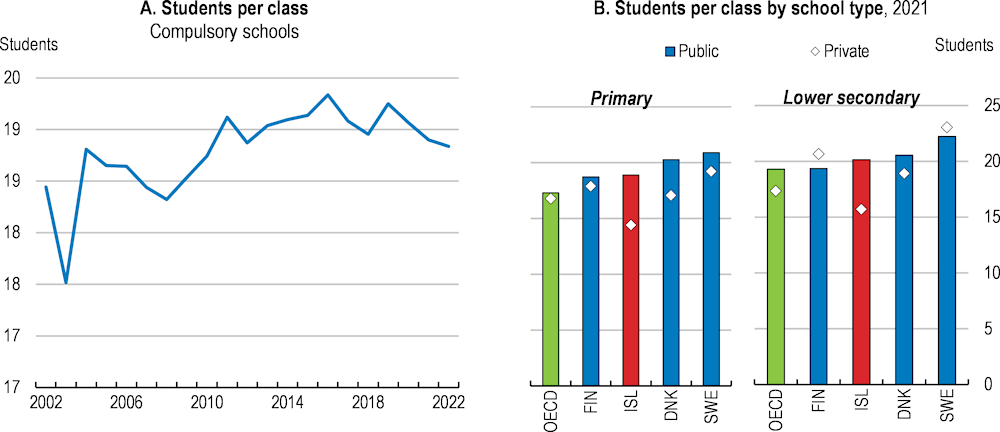

School overcrowding does not appear to be a source of concern. While the student population in compulsory education increased steadily over the past decade, the number of students per class remained, on average, broadly unchanged (Figure 2.16). International comparisons further suggest that Iceland ranks close to the OECD in this indicator both in primary and lower secondary education, with a small difference between the two levels. The average figures, however, mask variations among regions, as the problem may arise more in the areas receiving higher proportions of immigrants. In addition, Iceland exceeds the OECD average in terms of the gap in average class size between public and private institutions. The large majority of students in the country attend public schools.

Figure 2.16. The average class size remains relatively small

Note: In Panel A, students in special education schools and special education classes are excluded. Students in multi-grade classes are included. For 2004-06, students in Kárahnjúkaskóli are excluded.

Source: Statistics Iceland; and OECD, Education at a Glance.

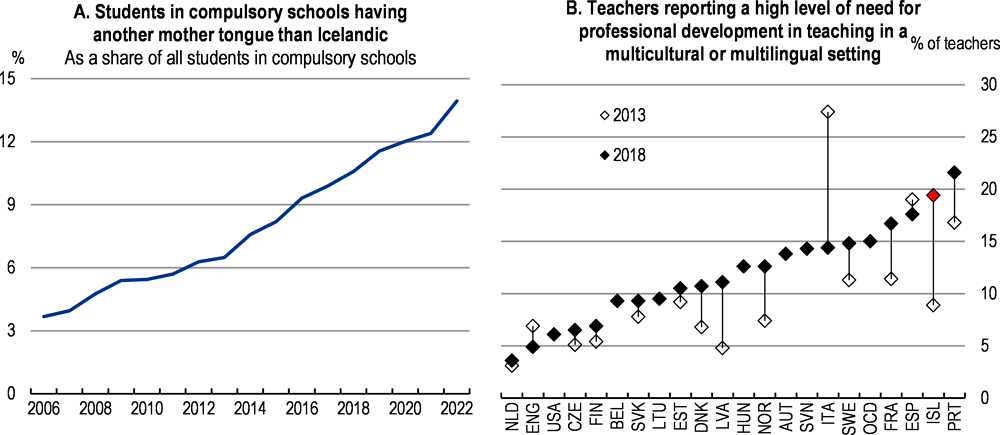

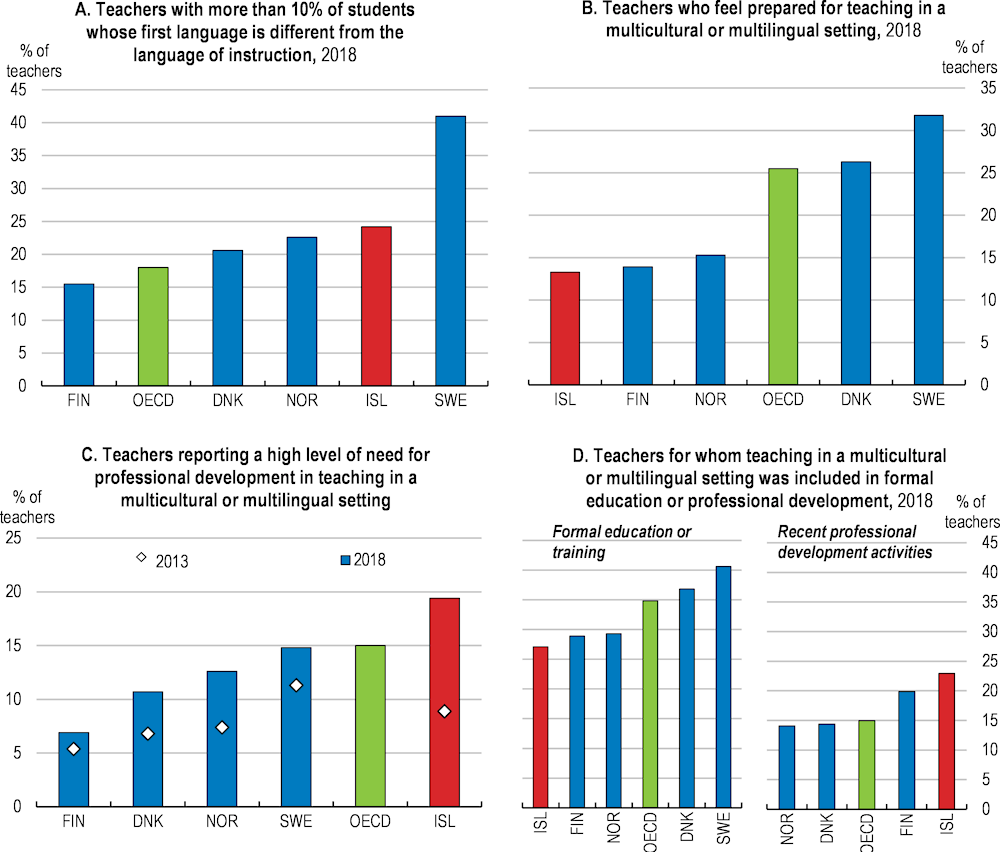

Immigrant students often require higher per-capita educational expenditure, especially upon arrival in the host country, placing additional demands for resources on schools (OECD, 2016[26]). An important component of such costs regards the additional language needs of foreign students. The share of students in compulsory education with a foreign mother tongue has increased steadily since 2006 (Figure 2.17, Panel A). Around 7% of students in compulsory education were receiving support for learning Icelandic in 2020-21, according to national data, compared to merely 3.5% a decade before, and increasing immigration will most likely raise budgetary cost further. The government provides financial assistance to municipalities to meet expenses for special needs and Icelandic lessons for immigrant children. A larger population of students with diverse needs also requires additional resources for in-service training and support for teachers to work effectively with immigrant students. The share of teachers working in multicultural or multilingual settings (including with refugee children) and reporting high needs for professional development has increased in recent years. In 2018, it was among the highest in OECD, according to the latest findings from TALIS (Teaching and Learning International Survey) (Figure 2.17, Panel B). The challenges can be larger in small rural communities where access to qualified teaching staff is more limited.

Figure 2.17. Immigration can create additional demand for educational resources

Note: In Panel A, mother tongue is defined as the language the child learns first, uses most fluently and is spoken at home, sometimes only by one parent.

Source: Statistics Iceland; and OECD, Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) database.

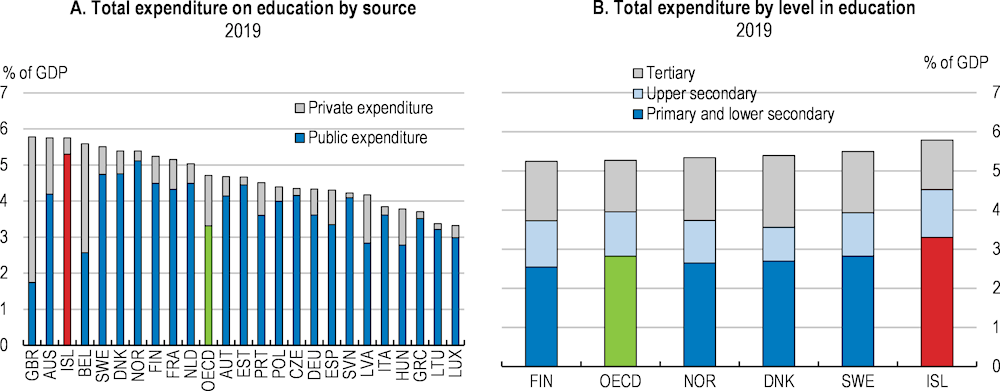

There are no available estimates of the overall school expenditure allocated to immigrant students in Iceland. International comparison of total education expenditure reveals, however, that Iceland spends 0.8% of GDP more on education than the average OECD country, with the difference mainly reflecting high expenditure on compulsory education (primary and lower secondary education), which is almost fully publicly funded (Figure 2.18). This reflects, to a large extent, the “inclusive school” policy, stipulating that all students, irrespective of their special education needs, should have access to regular schooling, an objective that is reinforced by the current education multi-year government strategy (OECD, 2016[27]). The first pillar of the “Education Policy 2030” strategy focuses, in particular, on measures to accommodate multi-cultural school populations and differentiate teaching and support (OECD, 2021[28]) (see below). For the implementation of the strategy, additional government funding will be required to ensure that schools and teaching staff can meet the needs of migrant students.

Figure 2.18. Spending on compulsory education is comparatively high

Empirical evidence on educational peer effects is mixed. Several studies have looked at the impact of the presence of immigrant students on the school performance of native-born students, or all students. There are concerns, for instance, that teachers in classrooms with a high concentration of immigrant students may be overburdened or need to spend considerably more time on such students, which may lead to negative peer effects (OECD, 2016[26]). Empirical evidence on the topic is mixed (Mezzanotte, 2022[29]). For instance, cross-country analysis by (Seah, 2016[30]) shows a differential impact of immigrant peers across the three countries considered (Austria, Canada and the United States). In particular, exposure to immigrant students has a positive impact on Australian natives, while the impact is negative in the case of Canadian natives. Exposure has no effect on native students in the United States. Institutional factors, such as the organisation of educational systems, play a crucial role in how immigrant students affect their peers. For Iceland, empirical evidence based on immigrant background and the language spoken at home shows a smaller peer effect across primary school classes than the average of the six European countries (France, Germany, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden) considered (Ammermueller and Pischke, 2009[31]), but this evidence dates back to a time when the share of immigrants in the total population was much smaller.

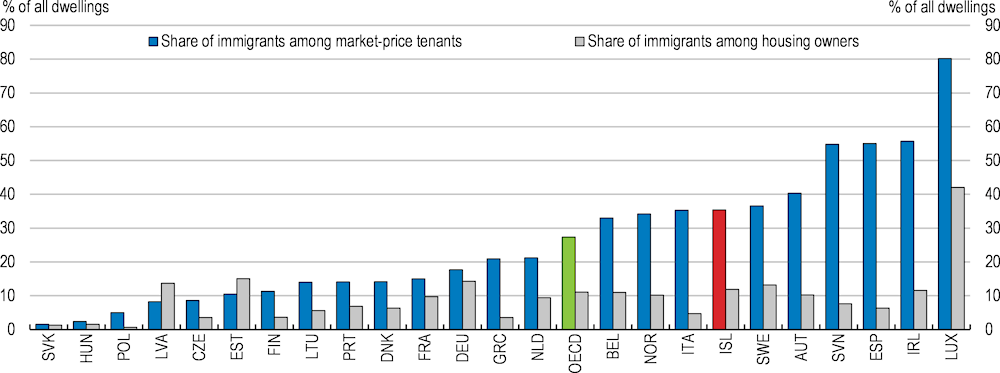

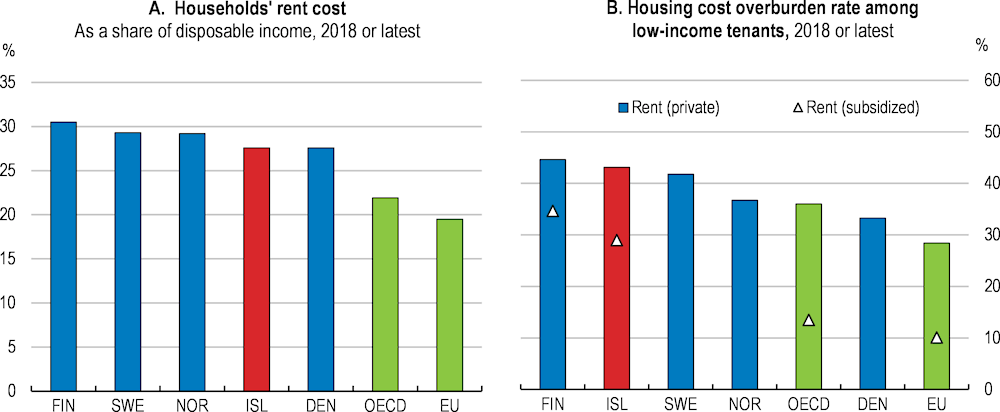

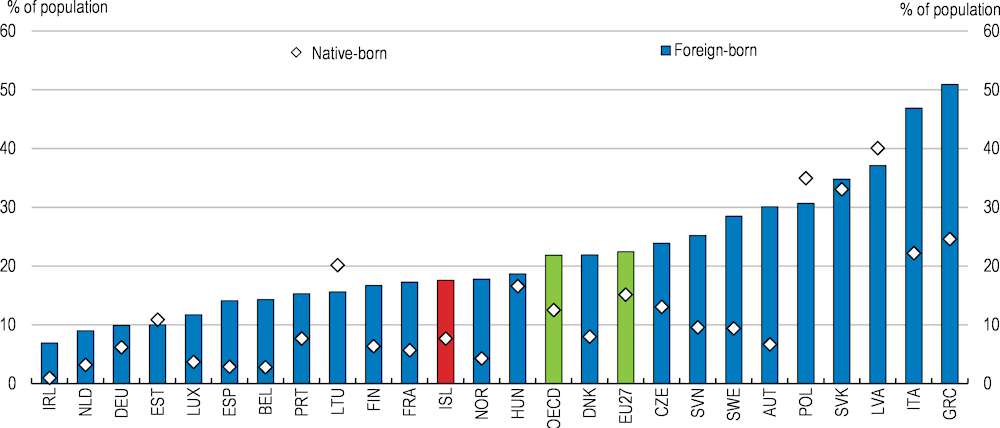

2.4.4. The impact of immigration on the housing market

Immigration affects housing markets by adding not only to demand but also to supply, given the important contribution of immigrants to the construction sector (Figure 2.10). A priori, the increased demand for housing resulting from the arrival of immigrants would be expected to affect the dynamics of house prices and rents, but the magnitude of the impact depends on the elasticity of housing supply, and thereby on the housing/rent and construction regulations. The less elastic the supply the larger the impact of immigration, at least in the short run. Other parameters also affect house prices. Immigration, for instance, may influence the composition of housing demand, given that immigrants usually opt for inexpensive housing due to their relatively low incomes (Kalantaryan, 2013[32]). Moreover, rising immigration may lead to lower building costs, which increases incentives for the construction of new dwellings, affecting house price developments.

Other factors that go beyond population growth, such as credit conditions and expectations, should also be considered when assessing the impact of immigration on house prices, while at the local level such impact also depends on the mobility response by previous residents to increased immigration, which can attenuate the house price effect (Kalantaryan, 2013[32]; OECD, 2016[26]). At the same time, establishing causality is difficult as newly arrived immigrants tend to locate in regions with good economic prospects and thus likely rising house prices (OECD, 2016[26]). Estimating and predicting the impact of immigration on the dynamics of housing markets is therefore difficult.

Empirical evidence on the impact of immigration on house prices is also mixed. On the one hand, examining the drivers of the housing market boom between 2004 and 2007, (Elíasson, 2017[3]) shows that net immigration of 1% of the population results into a house price rise of between 4% to 6% in Iceland, a stronger impact, according to the author, than the estimated effect derived by studies for other countries, such as Spain. Empirical analysis by (Gonzalez and Ortega, 2013[33]) concluded that immigration in Spain is responsible for an increase in housing prices of about 2% annually. On the other hand, some studies have found that immigration has actually reduced house prices in areas where immigrants settled because of the mobility response of the native population (Cochrane and Poot, 2019[34]; Sá, 2015[35]). For instance, estimates by (Sá, 2015[35]) for the United Kingdom show that previous inhabitants at the top of the wage distribution leave high immigration areas and move to other regions.

2.4.5. The fiscal impact of immigration

Immigration has both costs and benefits for the budget. Most studies, however, suggest a limited net fiscal impact (Box 2.4). In the case of Iceland, available estimates suggest that immigration may well have a positive net fiscal impact, to the extent that immigrants contribute more in taxes and social contributions than they receive in benefits (Nyman and Ahlskog, 2018[36]; OECD, 2013[37]). The composition of the immigrant population matters (OECD, 2021[38]; OECD, 2013[37]). In countries where recent labour migrants account for a large part of the immigrant population, such as Iceland, immigrants tend to have a more favourable fiscal impact than in countries with longstanding immigrant populations, as in the former case immigrants are relatively young, and thereby do not burden pension expenditure. With the increased number of people seeking international protection and refugees, the direct fiscal costs have increased in recent years.

Another key determinant is the employment status of immigrants. While in most countries, governments tend to spend less on immigrants on a per capita basis than on natives, immigrants tend to make lower per capita contributions to public revenues than natives (OECD, 2021[38]). The less favourable contribution reflects the fact that immigrants often have lower employment rates and wages than natives. Reducing the gap in employment rates between immigrants and natives would therefore yield significant fiscal gains. These are estimated for instance at around 0.5% of GDP for Sweden and Denmark, with the yield rising with the level of education (OECD, 2021[38]). There are no specific estimates for Iceland, but overall immigrants already have higher activity rates than in Sweden and Denmark. Even so, improving labour market conditions for highly educated immigrants, including by addressing overqualification (see below), could yield important fiscal gains, especially in view of the favourable demographics of immigrants in the country, with most immigrants being of working age.

Box 2.4. Some international evidence on the fiscal impact of immigration

A number of studies have attempted to estimate the fiscal impact of immigration, using different approaches. Most found a small net fiscal impact.

Cross-country analysis (OECD, 2013[37]), also covering Iceland, for the period before the global financial crisis, estimates that the net fiscal contribution of immigrants is close to zero, on average, rarely deviating in one or the other direction by more than 0.5% of GDP. For Iceland, the study finds a high positive net fiscal contribution of around 1% of GDP, above the OECD average. A more recent OECD study (not covering Iceland) for the period 2006-18, also finds a persistently small total net fiscal contribution over the period, ranging between minus and plus 1% of GDP for most countries considered (OECD, 2021[38]). The study concludes that government expenditure on the foreign-born is 12% lower than on native-born on average across countries, whereas immigrants contribute, on average, 11% per capita less than the native-born.

A study by (Nyman and Ahlskog, 2018[36]), also covering Iceland, focuses on the fiscal effects of intra-EEA migration. It infers that most EEA countries (21 out of 29) saw a positive fiscal impact from intra-European migration. The net fiscal impact in almost all countries was relatively small, between plus and minus 0.4% of GDP. The study concluded that the total net impact for Iceland was not significantly different from zero.

Assessing the dynamic effects of an exogenous migration shock on a panel of 19 OECD countries for the period 1980-2015 (d’Albis, Boubtane and Coulibaly, 2019[15]) find that increased migration improves the fiscal balance, through its positive effect on GDP per capita (see above) and through a decrease in per capita net transfers from the government and per capita old-age public spending.

Using the tax-benefit microsimulation model of the European Union (EUROMOD), (Christl et al., 2021[39]) find that immigrants had a more positive net fiscal contribution in 2015 than the native-born. However, estimates for the net fiscal impact over the life cycle indicate a larger net fiscal impact for natives than migrants, especially in the case of extra-EU migrants, even though the results vary considerably across EU member states.

An OECD review of recent country studies for EU members shows that the overall fiscal impact is small, with the findings further revealing a lower fiscal contribution for the non-EU immigrants compared to their counterparts from the EU group probably due to lower employment rates for the former group (OECD, 2021[38]). In France, evidence for the period 1979-2011 suggests that the net contribution of EU immigrants declined over the period, as a result of the ageing of immigrant population.

The broader economic consequences of immigration and its fiscal impact depend critically on the integration of immigrants. Appropriate policies that facilitate labour market integration of immigrants and improve the educational outcomes of their children, as well as the provision of adequate social and affordable housing, are of key importance as they largely condition other aspects of integration, shaping the economic role of immigration and helping to harness the potential benefits. Such areas also receive particular attention in the government’s four-year Action Policy Plan on Immigration Issues, covering the period 2022-25, with an overall objective to ensure equal opportunities and promote active participation in the labour market and society regardless of origin (Government of Iceland, 2022[6]). Ensuring successful integration, inclusion and social cohesion requires coordinated efforts by all stakeholders namely the government, municipalities and employers.

2.5. Improving the labour market integration of immigrants

2.5.1. On average, immigrants have worse labour market outcomes than natives

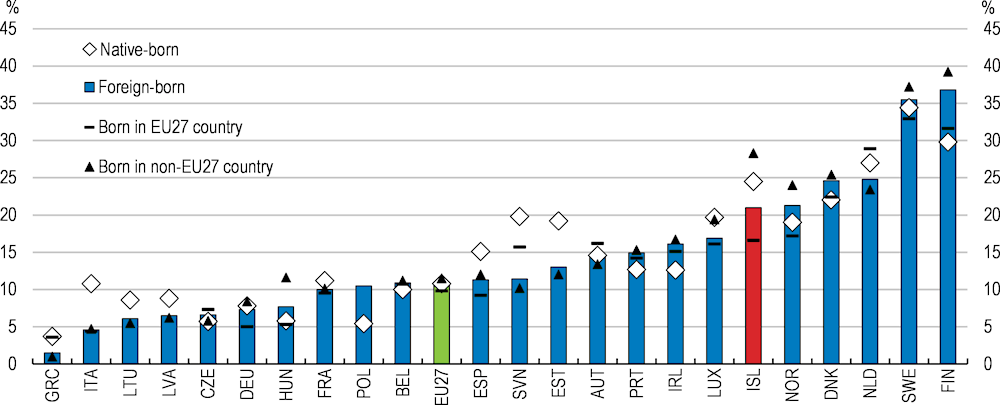

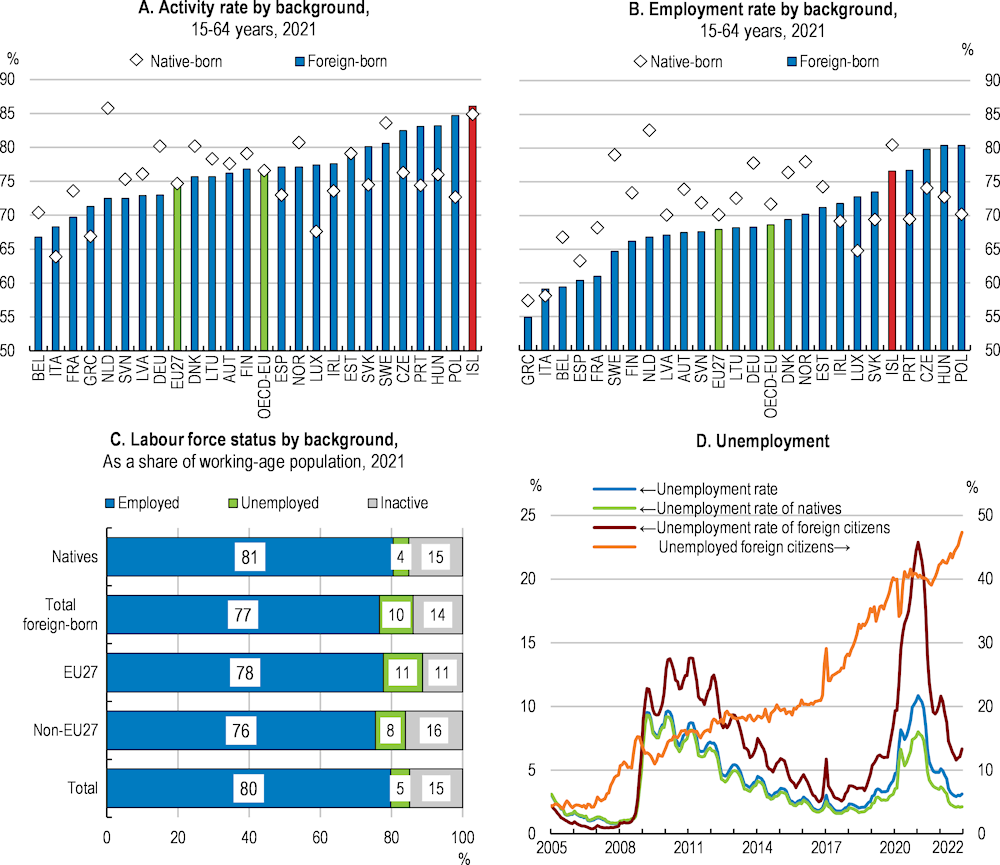

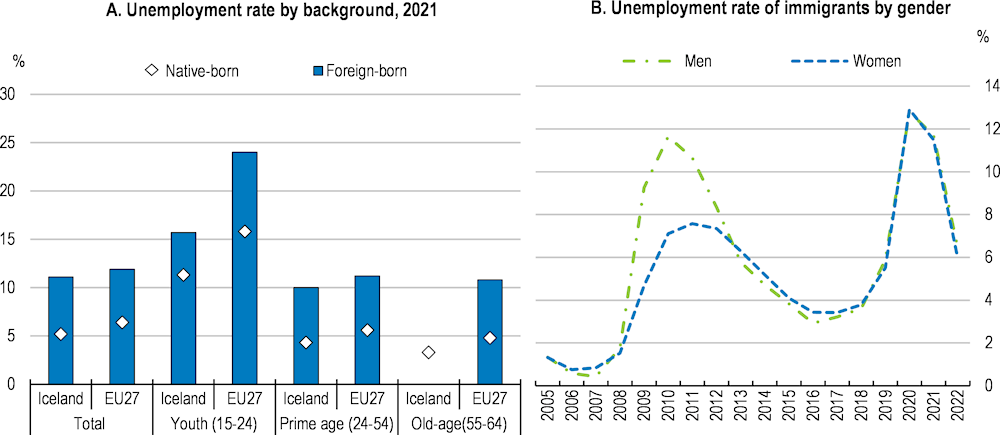

The participation rate of the foreign-born population is the highest among OECD countries and somewhat above the corresponding rate for the native-born (Figure 2.19). Moreover, Iceland has the narrowest employment gap between natives and foreign-born nationals among the Nordic countries, with relatively small differences in employment status between EU and non-EU nationals. Nonetheless, foreign-born workers face much higher unemployment than natives. The share of foreign-born nationals in registered unemployment has increased steadily since the mid-2000s, reaching 50% in 2022. Disaggregated data suggest that the unemployment gap between foreign-born and native-born persists across different age groups, although the foreign-born in Iceland, especially in the case of youth, have lower unemployment rates than their EU counterparts on average (Figure 2.20).

Figure 2.19. The labour market outcomes of immigrants can improve in some respects

Note: In Panel A, activity rate is calculated as economically active (employed and unemployed) working age (15-64) population divided by the total working-age population. In Panel B, employment rate is calculated as working age (15-64) employed population divided by the total working-age population. In Panel C, the rates are defined as the ratio of number of persons aged 15 to 64 under each status to the total population of the same age group. In Panel D, the data are sourced from the Labour Force Register and the unemployment rate corresponds to the share of unemployed in the active population. Unemployed foreign citizens refer to the share of unemployed foreign citizens in total registered unemployment.

Source: Eurostat, Labour Force Survey; and Statistics Iceland, Labour Force Register.

Gender differences in the labour market performance of immigrants, as reflected in the registered unemployment data, are very small, despite the fact that foreign-born women tend to be better educated than foreign-born men (Figure 2.20 and Figure 2.9). This may reflect the fact that women with an immigrant background are less likely to work in low-skilled occupations where is usually an excess demand for labour as they have on average a higher education level than their male counterparts (OECD, 2020[40]). At the same time, it is welcome that immigrants in Iceland have the same access to childcare facilities as the natives, especially as it is likely that women with a foreign background lack support of family networks in the host country.

Figure 2.20. The immigrant-native unemployment gap persists across all age groups

Note: In Panel A, data are sourced from the Labour Force Survey and the unemployment rate is defined as the share of unemployed in economically active (employed and unemployed) working age (15-64) population, unless specified otherwise. In Panel B, unemployment rate is defined as the ratio of registered unemployed immigrants to the working age (15-64) population.

Source: Eurostat, Labour Force Survey; and Labour Force Register.

A much larger proportion of immigrants are over-qualified compared to natives, implying that many of these workers do not meet their potential (Figure 2.21, Panel A). In 2021, more than 40% of the highly educated immigrants worked in a job below their formal qualification level, over 30 percentage points above the rate of natives. Over-qualification is particularly widespread among the foreign-born who have more recently settled in the country and non-EU immigrants who are foreign-educated. In addition, while overall employment rates for immigrants and natives do not differ much, the former group underperforms when looking at the highly-educated workers (Figure 2.21, Panel B).

Figure 2.21. Immigrants are much more likely to be over-qualified than natives

Note: The over-qualification rate refers to the share of highly educated (ISCED 2011 Levels 5-8) who work in a job that is ISCO-classified as low- or medium-skilled (ISCO Levels 4-9).

Source: OECD, “Settling In 2023: Indicators of Immigrant Integration”.

The less favourable labour market outcomes of immigrant workers compared to natives may be due to several inter-related factors. For instance, as discussed above, immigrants tend to be concentrated in sectors with high volatility, such as construction and tourism, thereby being disproportionally affected by economic shocks. Moreover, immigrants often work on temporary projects and become unemployed at their completion (Government of Iceland, 2022[6]). At the same time, skills differences between immigrant workers and natives, and especially the poor linguistic skills of immigrants, make it difficult for them to move between jobs or to another field with higher linguistic requirements. The pandemic highlighted the more vulnerable position of immigrants in the labour market. According to a recent study, immigrants fared worse than their native counterparts in 2020 in terms of job opportunities, and especially job-security (Karlsson, 2022[41]). The findings for other labour market indicators included in the study, namely choice of employment, opportunities for self-employment and real incomes, also indicated that immigrants were affected disproportionally by the pandemic, with lower perceived happiness levels among immigrants than natives.

Immigrants tend to have some wage disadvantage compared to natives. A study by Statistics Iceland finds a wage differential of around 8%, on average, over the period 2008-17 after controlling for individual characteristics and various employment-related factors (Statistics Iceland, 2019[42]; Statistics Iceland, 2019[43]). The pay differential varies by occupation, with the higher earning gaps found in low-skilled occupations such as cafeteria assistants and cleaning staff, by country of origin, as well as by length of stay in Iceland, with the gap declining over the years following the arrival. The gap in earnings between immigrant and native workers remains, irrespective of the educational level, according to the findings. Nonetheless, a large part of the wage differential remains unexplained. Cross-country analyses also suggests that, by international comparison, Iceland has a relatively large share of the native-to-immigrant wage gap that cannot be explained on the basis of productivity differentials (Cupak, Ciaian. and d’Artis, 2021[44]). Natives seem to still earn around 13% more than immigrants after controlling for productivity differentials, according to the results. The study attributes the unexplained wage gap and its variation across the examined countries to several factors, including labour market discrimination, penalties associated with non-standard forms of employment (e.g. part-time, temporary employment), imperfect transferability of skills (education and experience) and language proficiency.

2.5.2. Providing effective language training to adult immigrants

Early intervention yields important benefits in terms of integration. Evidence for EU countries suggests that language courses for recently arrived non-native speakers can increase by 8 percentage points the likelihood of proficiency in the host language, with concomitant employment benefits (OECD, 2021[45]). Supporting the rapid acquisition of language skills is also essential for the successful integration of refugees who intend to stay.

Participation in language training is not mandatory, but a variety of language learning courses are available for adult immigrants in Iceland, with applicants for international protection also being eligible for such training. Language learning courses are offered by a number of providers including by Landnemaskólinn (The Settlers School), where the courses are organised by the trade unions, as well as by various education institutions and in the context of the certified programmes of further education (Government of Iceland, 2022[6]). Language schools are funded privately and through government grants (Hoffmann et al., 2021[46]). More specifically, accredited education providers offering Icelandic language courses which are not part of a general curriculum in the public school system can apply for grants from the Icelandic Centre for Research (Rannís). Government support is granted only for courses recognised by the Directorate of Labour.

There is scope to make adult language training more effective. Around 60% of immigrants covered by a survey in 2018 reported dissatisfaction with the language courses received, generally expressing a preference for courses that are better aligned to their daily needs (Hoffmann et al., 2021[46]). Other frequently cited shortcomings included a lack of in-class evaluations for the levels of language proficiency and of an official language certificate that could be used in job applications. There are also regional disparities in the provision of Icelandic language training, with fewer courses in rural areas. A comprehensive approach to language training for adult immigrants is required. In other Nordic countries, language training is a part of the introduction programmes for immigrants (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2019[47]). In Norway, for instance, around 60% of refugees leaving the Introduction Programme in a specific year were employed or engaged in education one year after the programme, according to Statistics Norway. A study from the Institute for Social Research further concluded that refugees who participated in the Introduction Programme do better in terms of employment, welfare dependency and the level of income compared to their counterparts who did not participate in such programmes (Røed et al., 2019[48]).

A clearly defined framework for language training of adult immigrants, defining accessibility and quality standards, as well as the role and responsibilities of stakeholders, is essential for achieving involvement of all partners and ensuring effective integration. It is important that publicly-supported language training programmes are flexible in terms of structure in order to be compatible with participants’ work and family obligations. As noted above, a lack of flexibility was identified as one of the main shortcomings of the language training for adult immigrants in Iceland. Australia, Canada and New Zealand offer a range of language training options including part-time, evening and distance learning, while combining them with free childcare (OECD, 2021[45]).

Making language training for adult immigrants a part of a comprehensive approach to immigrant integration, rather than as an isolated skill to develop, is key. A new OECD report highlights that combining language instruction and vocational training has proven to be more effective in terms of future integration than providing trainings in parallel (OECD, 2023[49]). Several countries provide vocation-specific courses, including Denmark and Sweden. Iceland has been offering work-related language courses during working hours since 2003, largely funded by the government in cooperation with unions and employers. More systematic provision of language courses by Icelandic employers would further enhance the labour market relevance of training, in addition to improving the linguistic skills of employees with an immigrant background. Including language training in activation programmes is an additional way to help immigrants’ labour market integration (OECD, 2021[45]). The right of all jobseekers under the Public Employment Service (PES) to attend two Icelandic courses per year for free is a welcome initiative that needs to continue.

To reach a greater number of immigrants, regional disparities in the provision of language training and/or obstacles related to its financial cost for immigrants need to be addressed. Increasing the provision of online language training would be important in this regard, helping to deal with under-provision in the rural areas (see above). It is crucial to ensure that cost is not an obstacle to participation in language training. Iceland does not provide free accredited language courses for immigrants but union members can get a large part (around 75%) of the fee reimbursed. There is no clear-cut answer according to a recent OECD report (OECD, 2021[45]) as to whether or not language courses for adult immigrants should be free of charge, with varying cross-country experience in this area. Language courses are provided free of charge in Finland and Sweden, and reimbursement options are available in Denmark. The OECD report highlights, however, the need for the financing models to guarantee the affordability of courses for eligible learners, while also including incentives for performance by providers, as is the case for the results-based financing system used in Denmark (OECD, 2021[45]). Under this system, providers are paid half the tuition fee prior to the course and half after the individual migrant has passed the course exam, with the potential to contribute to more efficient course outcomes. Financing models should also ensure incentives for students to participate in the courses.

There is scope to increase the quality of language training for adult immigrants. There were some positive moves in recent years towards improving teacher training, including through the introduction in 2016 of the Master’s degree in Second Language Teaching, and the adoption of curricular guidelines in 2008 and 2012 to standardise language teaching (Hoffmann et al., 2021[46]). Nonetheless, there are still no formal requirements for teachers of Icelandic as a second language. Such teachers, in particular, are not required to have a degree or training in teaching Icelandic to adults as a second language and as a result, their education background and professional experience can vary considerably. In addition, some studies conclude that that the government curricula guidelines have not been implemented rigorously so far, which may inhibit the standardisation of courses (Hoffmann et al., 2021[46]; Innes, 2020[50]).

Increasing quality also requires that language courses are developed further and reformed to better meet the different skills and learning speeds of the immigrants, while introducing student evaluation in language training to help immigrants improve their learning outcomes. The recent OECD report (OECD, 2021[45]) refers in this context to the modular system operated by Sweden and Denmark as an example of high-quality, personalised language courses to a diverse group of learners. Such a system organises learning in consecutive modules with increasingly advanced learning goals, enabling migrants aiming to continue beyond the integration targets to reach their personal or professional objectives. A modular system also better takes into account the linguistic diversity and training needs of refugees (OECD, 2016[51]). A better co-ordination of language training providers is also crucial for improving quality. There is also a need to review the curricula for Icelandic as a second language and for their implementation to be reinforced (see above), while defining competency levels in line with the European language framework, as done in the other Nordic countries (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2023[52]). It is important, in this context, that the government go ahead with the preparation of quality standards for Icelandic teaching, improving coherence (Government of Iceland, 2022[6]), while also defining formal requirements for language teachers. Ensuring adequate funding for Icelandic language teaching, including for teacher preparation, is essential, in tandem with developing rigorous evaluation mechanisms to regularly assess the outcomes in terms of language proficiency and labour market integration of immigrants. The announced increase of government funding to support language training for immigrants is welcome, especially in view of rising immigration.

2.5.3. Ensuring efficient and timely assessment procedures for skills recognition

Greater transferability of skills obtained abroad can help reduce skills mismatch and overqualification. The recognition of immigrants’ education credentials in Iceland is complex as the underlying procedures are often not sufficiently transparent and also due to the large number of actors involved, with over 10 different bodies in charge of assessing different types of credentials (Réttur Aðalsteinsson & Partners, 2019[53]). Under current arrangements, the ENIC/NARIC network (operated by the University of Iceland) is responsible for the recognition of academic qualifications, while the recognition of qualifications in regulated professions is granted by the appropriate competent authority in charge for the licenses in this field (Government of Iceland, 2023[54]). Immigrants need to navigate a complex system to find the right body responsible for recognising their qualifications, and the finalisation of assessment procedures takes longer than in other Nordic countries ̶ three months on average in 2016 ̶ although such data do not capture more recent improvements (OECD, 2017[55]).

Immigrants from non-EEA countries face relatively demanding recognition conditions for their qualifications and additional procedural hurdles. They need to ascertain equivalence with corresponding education provided in Iceland, which is not the case for their peers from EEA countries (Réttur Aðalsteinsson & Partners, 2019[53]). Navigating the system to obtain information on assessment and recognition of foreign qualifications is difficult for such groups due to language barriers. At the same time, the current system does not seem to provide sufficient guidance to applicants, even though Iceland maintains an information portal online explaining recognition requirements and procedures. Immigrants from the non-EEA countries frequently express concerns about a lack of information on the conditions to be met when applying for foreign credential recognition and a work permit (Réttur Aðalsteinsson & Partners, 2019[53]). Complexity may discourage immigrants from seeking to have their qualifications assessed and recognised, increasing the likelihood of over-qualification.

Ensuring timely recognition and assessment procedures is essential for enhancing effectiveness. This would avoid having immigrants unemployed or in jobs that do not match their qualifications for long periods. Norway and Sweden have developed novel approaches to speed up recognition procedures (OECD, 2017[55]) (Box 2.5). Norway’s scheme provides a pre-arrival fast-track assessment of foreign higher education credentials, which combines speed with high evaluation standards. Sweden’s scheme aims to accelerate the entry of skilled immigrants into shortage occupations. International experience can provide valuable guidance for speeding up the process for hiring foreign experts to meet the labour needs of the ICT sector as envisaged by the legislative proposal under way (see above). Other countries have also taken steps to accelerate the recognition procedures. Australia, for instance, has introduced a pre-arrival assessment of foreign qualification since 1999, while Canada is providing relevant information and exam preparation material to international trained individuals prior to arrival (OECD, 2017[55]). In addition, in Canada’s case, many occupations have offshore exams capacity to speed up the provision of licences.

Box 2.5. Fast-track schemes for recognition: some lessons from Norway and Sweden

Norway developed a “turbo-evaluation” for employers in 2014, which entails a fast-track assessment of the candidate’s foreign higher education credentials (OECD, 2017[55]). This makes it easier for employers to assess job applicants with foreign education. Interested employers fill in an online application form containing the applicant’s education credentials, his or her CV and written authorisation. Evaluation is carried out by NOKUT (the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education) within five working days and is free of charge. This is a non-binding evaluation and only for the job at hand.

Sweden has introduced a fast-track programme to speed up the entry of skilled immigrants into shortage occupations including engineering, teaching, technical occupations and the medical profession (OECD, 2017[55]). The objective of the programme is to combine recognition of foreign credentials and prior learning with workplace training and language lessons to provide an occupational certificate. The aim of the training process is to lead to a job that fits the participant’s skills and qualifications. Tripartite fast-track discussions are under way in a number of sectors.

The skills recognition system needs to become more user-friendly and transparent. Clear rules regarding eligibility requirements for the recognition of foreign qualifications and well-coordinated assessment processes among the bodies involved, along with easily accessible information and guidance for immigrants on how to obtain recognition are essential to reduce complexity and improve effectiveness. The establishment of a one-stop shop offering multiple services would very helpful. Several countries have established such contact points. Based on international experience, in addition to informing applicants on how to obtain skills recognition, one-stop shops accept their initial applications and pass them directly to the bodies in charge of the process (OECD, 2017[55]). They also assemble information and provide advice to the applicants and stakeholders, strengthening the system and enhancing transparency. All holders of foreign qualifications in Denmark are entitled under the Assessment of Foreign Qualification Act to an assessment through the central recognition agency (OECD, 2023[49]). In Sweden, a coordinating body, established in 2013, serves as a one-stop shop for all types of qualifications, while the online portal in Germany refers the applicants to competent authorities and provides information in various languages (OECD, 2017[55]).

2.5.4. Helping immigrants gain job experience

Gaining job experience is a pathway to successful integration, and active labour market programmes (ALMPs) that combine work experience and on-the job training have proven to be effective instruments (OECD, 2014[56]). Based on available evaluations, private-sector incentive schemes appear to be a successful measure for immigrants. A meta-analysis of 33 empirical studies for the European countries concluded that wage subsidies work better than other active labour market programmes targeted to immigrants and that they also have positive employment effects on immigrants in the short run (Butschek and Walter, 2014[57]). A recent review, focusing on the larger Nordic countries, also confirms that subsidised private-sector employment is the most effective activation programme for promoting the employment of immigrants, at least in the short run (Calmfors and Sánchez Gassen, 2019[58]). The impact of labour market training on employment outcomes appears to be lager in the medium to longer term, according to the review. In Iceland, jobseekers who have been unemployed for over three months are generally entitled to a recruitment grant (wage subsidy) for up to six months. In 2022, 43% of the beneficiaries were foreign citizens, including immigrants and refugees.

A careful design is required for wage subsidies. While such schemes can be an effective tool for improving the employability of low-skilled workers, they may involve the risk of crowding out unsubsidised hires, when employers choose to rely on subsidised labour rather than regular contracts and are reluctant to offer a permanent job to programme participants when subsidies expire. This problem could be addressed, however, by targeting the subsidies at the jobseekers most in need, using the subsidy schemes on a temporary basis and making them conditional on not substituting existing workers with those receiving a subsidy (OECD, 2014[56]). Moreover, providing information about the subsidy schemes in different languages is important.

The Directorate of Labour (VMST) plays a role in the labour market integration of immigrants by providing job-search support, connecting jobseekers with a foreign background with employers, and enhancing their employability through active labour market policies (ALMPs). Efforts towards VMST modernisation need to continue, along with the development of a solid set of performance indicators to evaluate and monitor the effectiveness of the provided activation programmes, as was recommended in an earlier OECD Economic Survey (OECD, 2019[59]).