Iceland’s economy is one of the fastest-growing of the OECD, driven by foreign tourism and strong domestic demand. The labour market is tight and wage growth robust, while high wage compression helps maintain a highly egalitarian economy. Inflation is persistent and broadening, and inflation expectations have de-anchored. The fiscal stance is tightening but more could be done to dampen inflationary pressures and support monetary policy. Labour market imbalances are rising. While progress has been made to remove barriers to the entry of firms in the tourism and construction sectors, barriers remain high in other sectors. Structural reform could help raise productivity notably in the domestic sector, while also contributing to disinflation. Higher and broader taxation of greenhouse gas emissions, coupled with investment in cost-effective actions, would help to efficiently achieve further emission cuts.

OECD Economic Surveys: Iceland 2023

1. Key Policy Insights

Abstract

1.1. Introduction

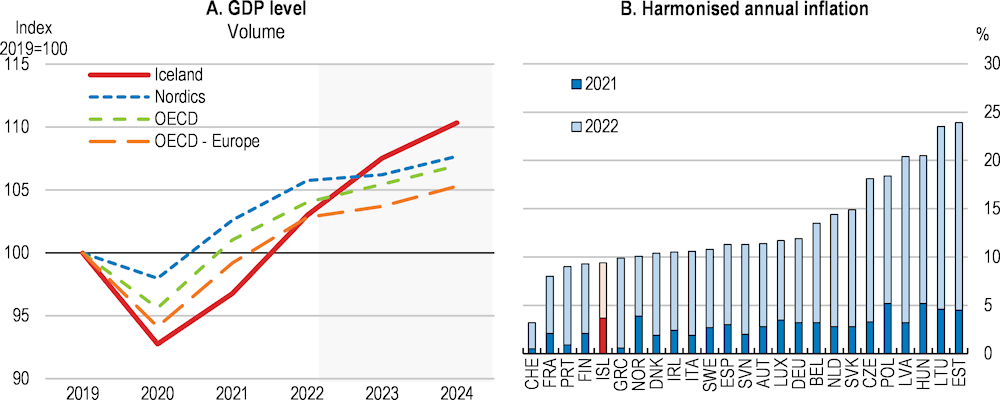

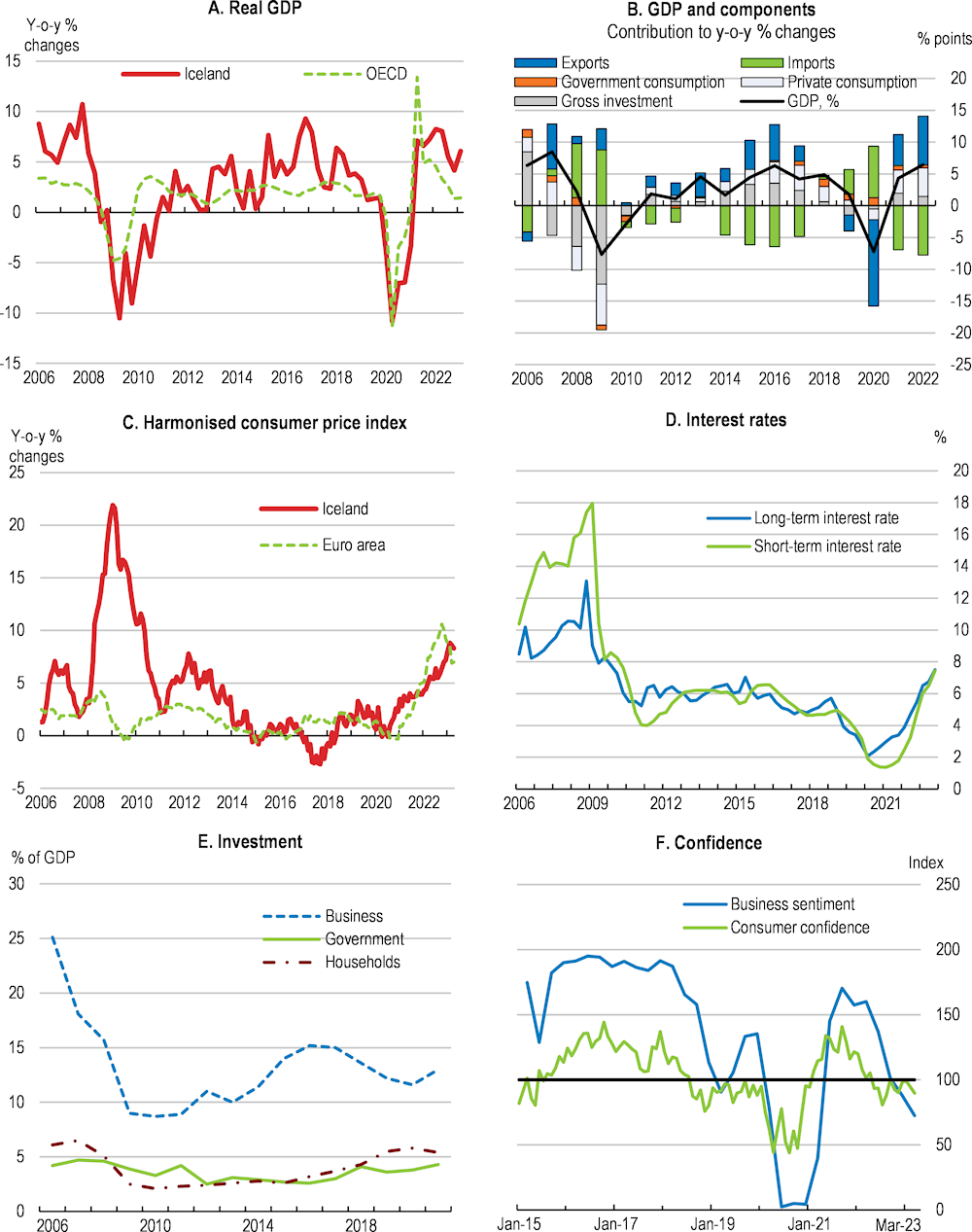

Iceland is the OECD’s smallest, among its most remote, and one of its fastest-growing economies (Figure 1.1). Foreign tourism is vigorously rebounding from the collapse during the covid-19 pandemic and exports of goods and services are thriving. Thanks to reliable domestic energy sources, the country has largely been spared the power crisis that has strangled other countries. Innovation activity is picking up, helping to diversify the economy and make it more stable and sustainable. Labour participation of both men and women, which had declined during the pandemic, is again approaching historical highs. A compressed wage distribution and a well-targeted tax-and-social benefit system is helping to maintain one of the most egalitarian economies of the OECD. Finally, trust in institutions, which is a key driver to maintain and reinforce democracy, is high.

However, Iceland is not sheltered from the storm racing through OECD economies. Inflation started to build up earlier than in many other OECD countries; it has reached levels unattained since the financial crisis in 2009, and it is broadening. Although the post-pandemic recovery was much faster than expected, the fiscal stance is not being tightened fast enough, and therefore not contributing sufficiently to the central bank’s efforts to return inflation to the target. The wage agreements reached in late 2022 and early 2023, as well as last year’s króna depreciation, could also add to inflationary pressures. Labour markets remain tight. The simultaneous rise of both the unemployment and job vacancy rate suggests growing imbalances in the post-pandemic labour market.

Figure 1.1. Iceland’s performance is strong

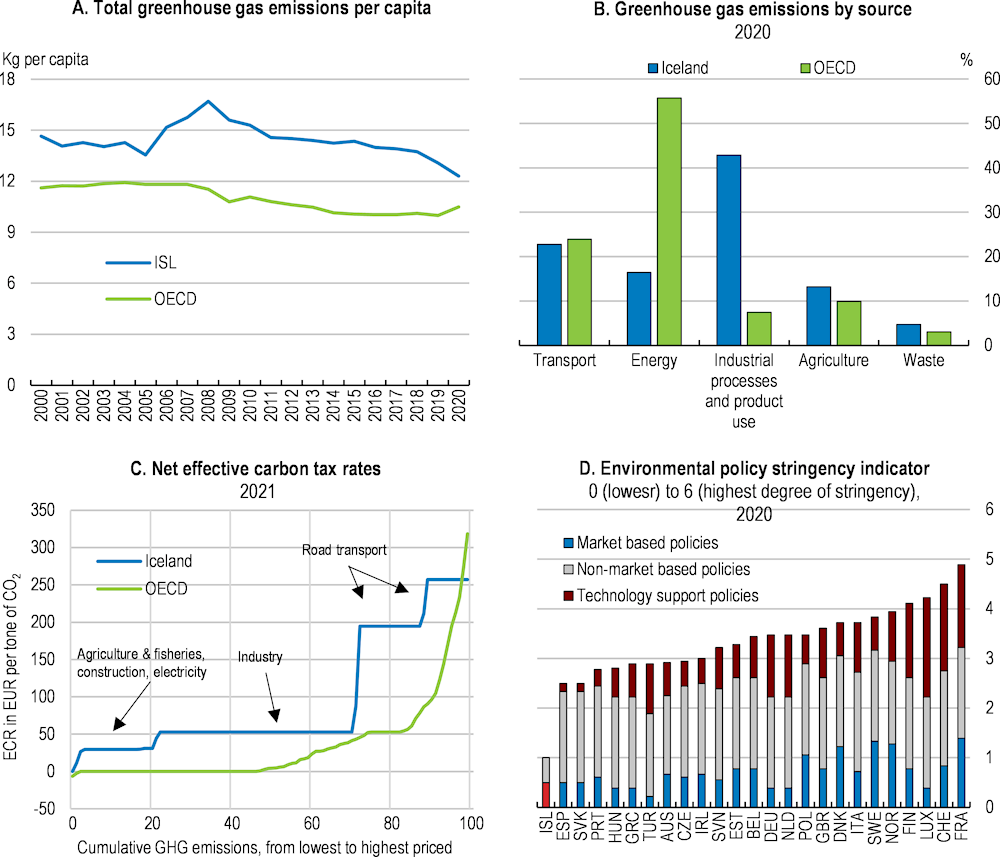

Besides managing the current macroeconomic turbulences, Iceland faces several structural challenges. Productivity growth was close to the OECD average only over the past decade, and it has slowed again after a brief acceleration before the pandemic, jeopardising sustained wage increases in the future. Considerable entry barriers, an extensive licensing and permit system and a cumbersome insolvency framework hamper sound competition and the emergence of new and innovative start-ups. Ageing is a long-term challenge, as the population will grow more slowly and get older, raising the cost for pensions, health care and long-term care. Iceland’s net per capita greenhouse gas emissions remain above the OECD average – although they started to decline – and stronger action will be needed to reduce emissions by at least 40% as set in the climate action plan.

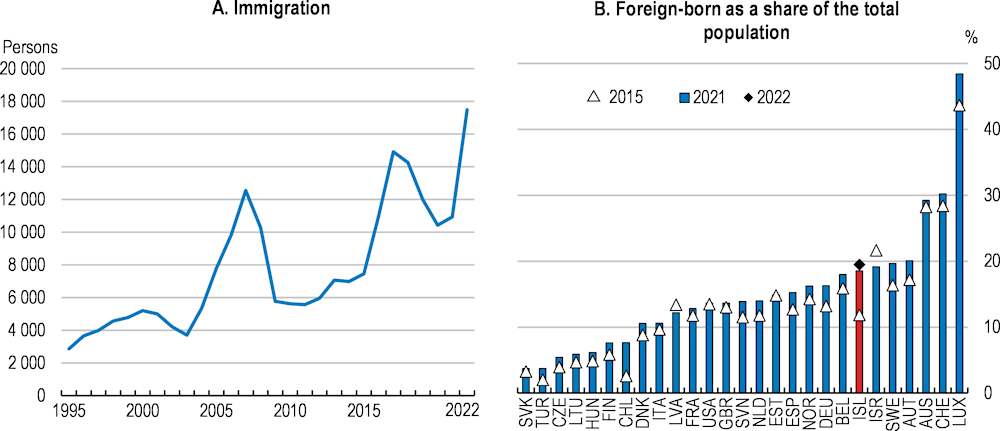

Immigration has become a key policy issue, as it has transformed the country more rapidly than most others in the OECD. As the inflow of labour immigrants kept rising, Iceland experienced the largest increase in the share of the foreign-born population among the OECD countries since the mid-2000s (Figure 1.2). Immigration plays an important economic role, including through the demographic gains it yields, helping to alleviate the adverse effects of population ageing. Immigrant workers contribute significantly to fast growing sectors, and they increase labour market flexibility. At the same time, immigration involves challenges especially for the education system in view of the poor performance and the diverse needs of students with a foreign background. Increased demand for affordable housing in a tight market adds to these challenges. Appropriate policies to better integrate immigrants and help them and their children to meet their potential are key to reap the economic benefits of immigration.

Figure 1.2. Iceland has become an immigration country

Note: In Panel A, data refer to the sum of Icelandic and non-Icelandic citizens. In Panel B, data refer to all persons that were born abroad.

Source: Statistics Iceland; and OECD, International Migration database.

Against this background, the key policy messages of this Survey are:

Better align monetary, fiscal and financial policies to bring inflation back to target, build up fiscal space and maintain financial stability.

Strengthen productivity growth by improving the business climate, easing the overreaching system of licences and permits, and investing in skills that are relevant for the labour market. Reduce carbon emissions further by mapping out a path towards higher and broader carbon taxation.

Get the best out of immigration by better integrating immigrants and their children, including through effective language training and efficient skills recognition, as well as by strengthening teachers’ professional development and ensuring a sufficient supply of affordable housing.

1.2. The economy remains strong despite some signs of cooling

1.2.1. Growth has peaked

Economic growth remains strong, although some signs of cooling have become apparent in early 2023 (Figure 1.3). Foreign tourism recovered from the pandemic-induced collapse and has regained its pre-pandemic levels. Some sectors such as aquaculture, pharmaceuticals, data storage and processing, and creative sectors like music and film are thriving. Household consumption growth is gradually levelling off on the back of tepid real wage growth and the declining value of assets, however. Business investment has picked up after the pandemic. The fiscal stance is contractionary, while investment in public infrastructure has reached a peak in 2022. Unemployment remains below 4%, close to the estimated structural rate.

Figure 1.3. Growth has peaked

Source: OECD, National Accounts database; OECD, Consumer Price Indices database; Eurostat; Statistics Iceland; and CEIC.

The central bank’s determined reaction to the surge of inflation was necessary, and it is contributing to slowing demand. Real wages have been sliding downwards, with ensuing consequences for household income, although real wage declines could have bottomed out with the wage agreements of late 2022 in the private sector and spring 2023 in the public sector. House prices – a key driver in the ongoing inflation cycle earlier on – are cooling. Both consumer and business confidence have declined.

Economic growth is expected to moderate from 6.4% in 2022 to 4.4% in 2023 and 2.6% in 2024. Household consumption will slow as real wages continue to weaken. Foreign tourism is likely to slow as capacity limits become more apparent and insofar as economic conditions in some of the origin countries worsen. Tighter financial conditions and considerable uncertainty will weigh on business investment. Housing investment will pick up in 2023 as pent-up demand is realised but will abate in 2024 as higher real interest rates bite. Public investment will no longer grow. The unemployment rate will edge up to around 4.5%. Inflation will decelerate in the wake of continued tightening, although it is projected to stay above target at the end of the projection period.

Table 1.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices |

Percentage changes, volume (2015 prices) |

||||||

|

GDP at market prices |

3 023.9 |

- 7.2 |

4.3 |

6.4 |

4.4 |

2.6 |

|

|

Private consumption |

1 518.4 |

- 3.4 |

7.0 |

8.6 |

3.7 |

2.0 |

|

|

Government consumption |

744.0 |

5.1 |

2.4 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.2 |

|

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

631.0 |

- 7.4 |

9.8 |

6.9 |

- 5.5 |

3.1 |

|

|

Final domestic demand |

2 893.4 |

- 2.0 |

6.3 |

6.4 |

1.2 |

2.0 |

|

|

Stockbuilding1 |

- 5.4 |

1.0 |

- 0.1 |

- 0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

|

Total domestic demand |

2 888.0 |

- 1.1 |

6.2 |

6.2 |

1.2 |

2.0 |

|

|

Exports of goods and services |

1 320.6 |

- 31.1 |

14.7 |

20.6 |

5.0 |

3.8 |

|

|

Imports of goods and services |

1 184.7 |

- 20.6 |

19.9 |

19.7 |

- 1.8 |

2.4 |

|

|

Net exports |

135.9 |

- 5.5 |

- 2.0 |

- 0.1 |

3.2 |

0.6 |

|

|

Memorandum items |

|||||||

|

GDP deflator |

_ |

4.1 |

6.6 |

9.0 |

6.4 |

3.5 |

|

|

Consumer price index |

_ |

2.8 |

4.4 |

8.3 |

7.4 |

3.3 |

|

|

Core inflation index2 |

_ |

2.9 |

4.4 |

7.8 |

7.2 |

3.4 |

|

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

_ |

6.4 |

6.0 |

3.7 |

3.9 |

4.3 |

|

|

Budget balance (% of GDP) |

_ |

- 8.9 |

- 8.4 |

- 4.3 |

- 2.5 |

- 1.4 |

|

|

Underlying primary fiscal balance (% of potential GDP) |

_ |

- 1.2 |

- 2.4 |

- 0.6 |

0.1 |

1.1 |

|

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP)3 |

_ |

70.4 |

77.2 |

78.4 |

78.6 |

78.6 |

|

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

_ |

1.3 |

-2.8 |

-1.8 |

-0.8 |

-0.2 |

|

1. Contributions to changes in real GDP, actual amount in the first column. Consumer price index excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco.

2. Consumer price index excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco.

3. Includes unfunded liabilities of government employee pension plans.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook No. 113 database.

The projections continue to be surrounded by considerable risks and uncertainty. The small size of Iceland’s economy makes it volatile and vulnerable. Inflation could remain higher than expected, triggering a wage-price spiral or else denting real incomes further. Goods and services exports, in particular tourism, could suffer from a stronger-than-expected slowdown in major origin countries, which could be aggravated by financial sector stress. Domestic shocks, such as a bad fishing season or a decline in viable fishing stocks, could affect exports of marine products. Investment could take an additional hit if financial conditions worsen further. A sharp fall in house prices could spark an economic contraction.

Table 1.2. Events that could entail major changes to the outlook

|

Shock |

Potential economic impact |

|---|---|

|

Inflation remains higher than expected. |

Real wages continue to decline, denting household income and consumption. |

|

Foreign tourism declines following a slowdown in the major trading partners, which could be aggravated by financial sector stress. |

Export revenues will decline, slowing GDP growth. |

|

Real estate prices plummet, pushing up non-performing loans. |

A sharp contraction ensues. |

1.2.2. The labour market remains tight, and imbalances deepen

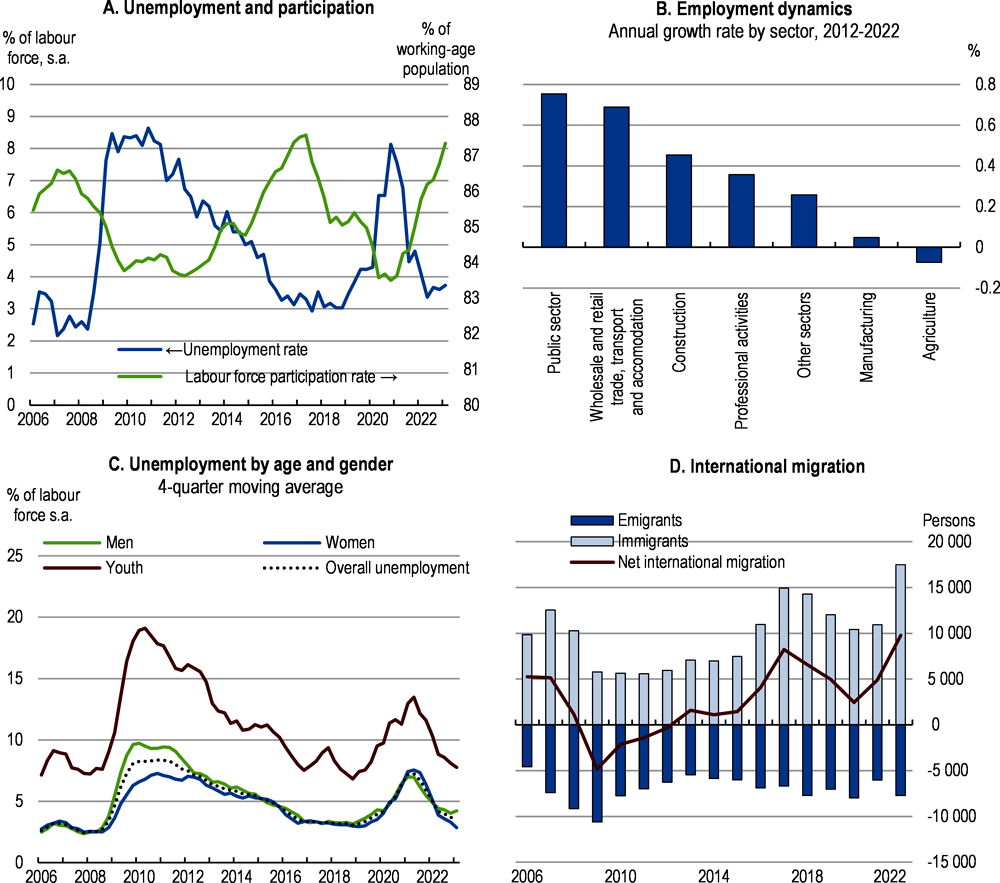

The labour market remains tight (Figure 1.4). Unemployment, which fell rapidly in the wake of the post-pandemic recovery, reached its lowest level in mid-2022 and has hardly changed since. Employment has expanded most in some service sectors, as well as in construction and IT-related activities. Differences in unemployment between men and women are negligible, and the gap between youth and overall unemployment remained largely constant both during and after the pandemic. Labour force participation, traditionally high in international comparison, is rising again, against the backdrop of flexible labour market regulation (notably flexible hire-and-fire and wage-setting rules), a high retirement age and generous support for working families (Olafsdottir, 2022[1]). Labour immigration from Europe, mostly Poland and Lithuania, has picked up after the end of the pandemic, alleviating labour shortages in Iceland’s booming economy (see also Chapter 2).

Figure 1.4. The labour market has started to ease but remains tight

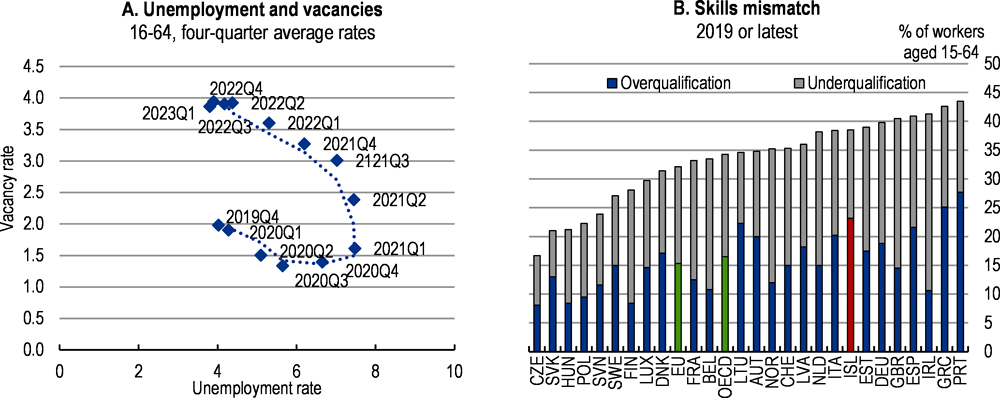

Both the pandemic and the recovery have exacerbated labour market imbalances (Figure 1.5). The relationship between unemployment and job vacancies has worsened over the past three years, as both the numbers of vacant jobs and unemployed workers have increased (the “Beveridge curve” has shifted outwards, although results should not be overinterpreted given the short period for which data are available). Rising unemployment is going hand in hand with rising labour market shortages, especially in the technical areas and in the health care sector, and overqualification in certain occupations sits along insufficient qualifications. In a 2022 survey, 56% of Icelandic firms said that they were short- or understaffed. Also, indicators of labour market qualification such as skills mismatch or field-of-study mismatch remain considerably above the OECD average. Around 75% of surveyed firms see lacking skills as a limiting factor for future growth. Business organisations point at increasing labour market polarisation and consider that the number of middle-skilled jobs is gradually declining.

The transition towards a more digitalised and greener economy is transforming Iceland, as in other countries. The transition requires strong and relevant skills, as pointed out in the previous Survey (OECD, 2021[2]). Against this background, the government should further develop skills and labour market policies to facilitate the labour market transition and provide sufficient qualifications for both existing and emerging job categories. It should notably expand skills in the STEM areas (science, technical, engineering and mathematics) which are in short supply, for instance by investing in dedicated upper-secondary and tertiary education. The fiscal plan 2023-28 foresees additional spending to expand education in STEM areas and in health care, which is welcome.

Figure 1.5. Labour market imbalances are considerable

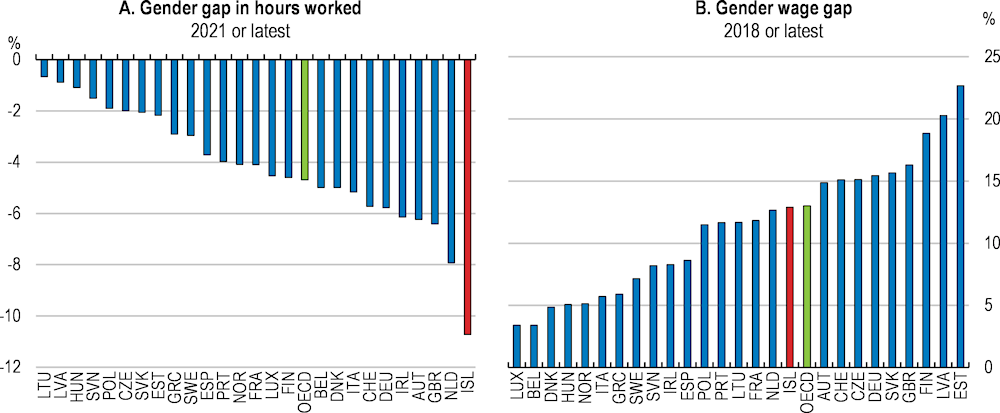

The gap in paid hours worked between men and women remains the widest in the OECD, despite a gradual decline over the past two decades and high female labour participation (Figure 1.6). During Iceland’s decades-long catch-up with the OECD’s wealthier countries, households followed a traditional work division whose shadows persist. Men often had several jobs and worked long hours to compensate for low hourly earnings, while women focused on child and family care (Olafsdottir, 2022[1]). Women are much more likely to work part-time than men (36% against 13%), and work more often in the public sector or in social services. Moreover, women are less often in higher management positions and in positions requiring STEM qualifications than men. The tax and benefit system provides few incentives for second earners - mostly women - to move from part-time to full time work as marginal tax rates are high (see fiscal section). As a result, and despite identical employment rates and a compressed wage structure, the wage gap between men and women is close to the OECD average. Against this background, an education system that fosters gender balance across professions and economic sectors, and reforms to the tax-benefit system could help reduce the gender wage gap.

Figure 1.6. The gender gap in paid hours worked is the highest in the OECD

Note: Panel A, percentage point difference in hours worked between men and women in full-time dependent employment. Panel B, data refer to gross monthly earnings of full-time employees, excluding apprentices, working in enterprises with 10 or more employees.

Source: OECD, Labour Force Statistics database.

1.2.3. Competitiveness could decline again

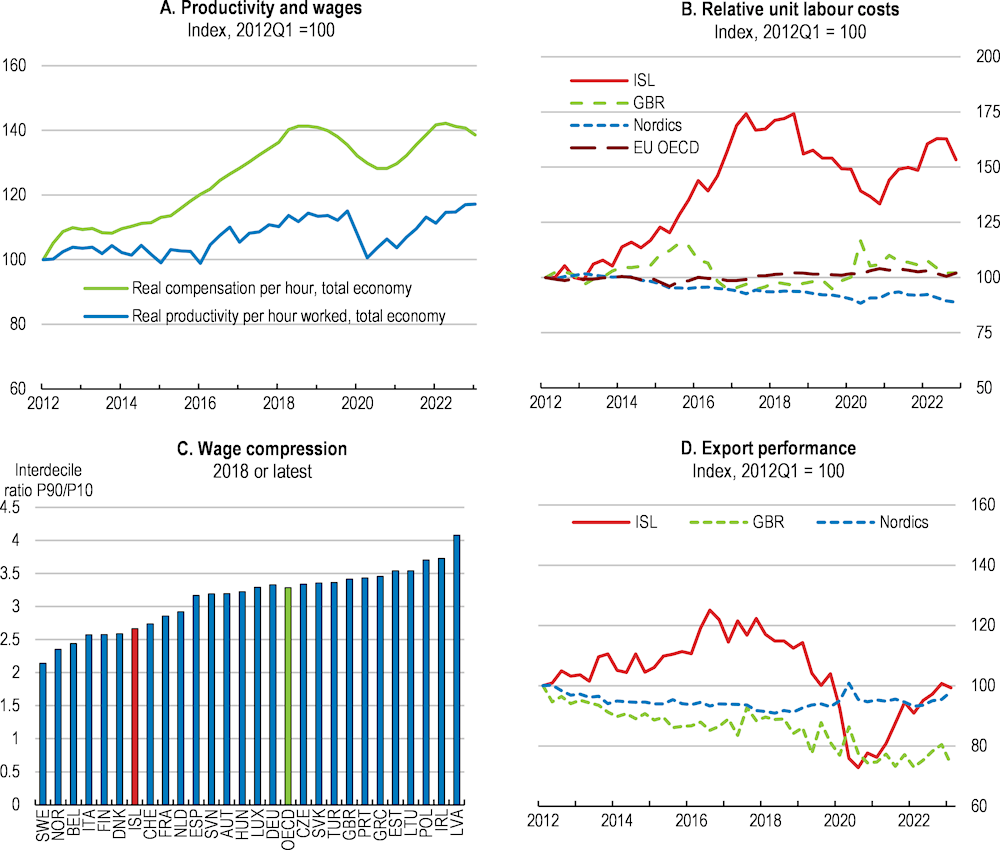

Real wages are moderating after the rebound from the trough associated with the pandemic-related collapse of foreign tourism and after having outpaced productivity growth for almost a decade since 2010. Productivity growth has become sluggish after it had accelerated a bit before the pandemic. Competitiveness as measured by relative unit labour costs has improved since the late 2010s and more so than in the other Nordic countries and the European Union, notwithstanding some erosion in 2021 (Figure 1.7). In 2022, relative unit labour costs fell by over 5 percentage points. However, they are unlikely to decline further in 2023 following the considerable wage increases agreed in late 2022 and expected weaker labour productivity growth, with firms retaining workers despite slowing output. Export performance follows a similar pattern as competitiveness, having recovered strongly after the deep fall during the pandemic.

Figure 1.7. Competitiveness improved, despite wages exceeding productivity growth

Note: Panels B and D: Nordics exclude Iceland. Panel B: relative unit labour costs (ULC) are measured economy-wide and trade-weighted, and show the evolution of competitiveness over time, with a rise in ULC reflecting declining competitiveness. Panel C: data refer to gross monthly earnings of full-time employees, excluding apprentices, working in enterprises with 10 or more employees. Panel D: export performance reflects the growth of a country’s export volumes compared to that of its export market.

Source: OECD, National Accounts database; OECD, Economic Outlook No. 113 database; and OECD, Labour Force Survey – decile ratios of gross earnings.

Iceland’s collective wage bargaining system tends to foster inclusiveness and countervail firms’ labour market power, but it could undermine flexibility, weaken the link with productivity and stifle workers’ incentives to move to more productive firms and jobs (OECD, 2018[3]). Iceland is the OECD’s most unionised country, with collective agreements covering around 90% of labour contracts. Negotiated minimum wages are binding and cannot be opted out by individual firms. The wage bargaining process is quite fragmented, with leapfrogging (or “dolphins’ race” in Icelandic) of wage demands potentially undermining competitiveness, although the merger of smaller unions over the past few years could have strengthened social partners’ consideration of the macroeconomic impact of wage settlements. Negotiations usually start in the private, export-oriented industrial sectors, and then move on to the domestic sectors and finally to the public sector. The “Living Standard Agreement” 2019-22 was the first to build on an explicit link between future GDP and wage growth but stopped short of using productivity as an anchor for wage developments. In late 2022, a connecting short-term “bridge” agreement was settled, valid until February 2024 (Box 1.1).

Box 1.1. The 2023 “bridge” wage agreements

The wage negotiations to follow up on the “Living Standard Agreement” – that had governed labour relations from 2019 to 2022 - took place in a context of high economic uncertainty. Therefore, the prospects to reach a long-term agreement covering several years, as did the former agreement, were dim. Also, negotiations took place under the impression that the “Living Standard Agreement” had not been flexible enough to react to the productivity slowdown during the pandemic and the surge of inflation thereafter.

In this context, employer organisations and unions reached a “bridge” agreement that took effect in November 2022 and will last until February 2024. The new collective agreements initially covered around 80% of all private sector employees, with wages set to increase by an average of 7.4%. In March 2023 the agreements were extended to an additional 20% or so of private sector employees, mainly in the accommodation and oil distribution sectors, following industrial action, walkout of employees and some disruptions in hotels and at airports. A small share of the labour force remains uncovered by new agreements. In the public sector, an agreement was reached in April 2023 for the vast majority of central and local government employees.

The wage bargaining framework focuses strongly on maintaining and even strengthening a compressed wage distribution - although the latter is less equal than in the other Nordic countries - with wage and other benefit increases often being the same in absolute terms across all wage groups (Figure 1.8). The compressed wage distribution partly explains Iceland’s egalitarian income distribution. Yet a wage structure that is compressed horizontally (across sectors) and vertically (across a firms’ hierarchy) might discourage workers to move to new, more productive jobs or to invest in stronger and more relevant skills, since respective monetary gains are small (OECD, 2019[4]). As a result, skills and study field mismatch remain high.

Against this background, the government and the social partners should rely more strongly on the link between productivity and wages when negotiating future agreements. While the government has no direct influence on private sector wage settlements, it could encourage negotiations to focus more on sectoral or firm-level productivity developments, as is the case in Denmark, Norway, or Sweden (OECD, 2016[5]). Under a multi-annual agreement, yearly wage adjustments could be handled more flexibly, to remain in line with actual developments in the economy. Some bargaining could be devolved to the firm level taking on the form of “organised decentralisation”, allowing firms to opt out from a collective agreement under certain conditions. Opting-out rules could promote productivity as firms could be allowed to use incentive schemes such as performance pay more frequently (OECD, 2018[3]). Finally, better productivity and wage data could help support more evidence-based negotiations. A first step has been made with the government now collecting more representative wage data.

Figure 1.8. Wages and wage growth are more equally distributed than productivity

1.2.4. The external sector has improved overall

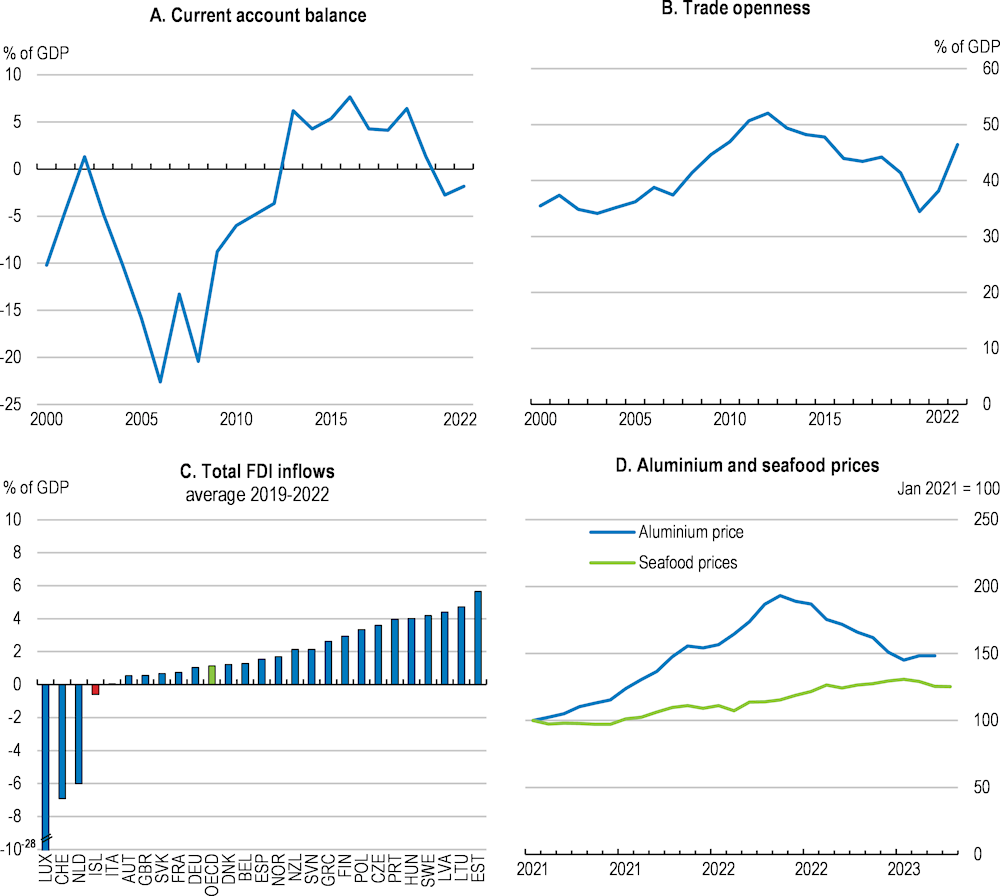

External positions have improved following the strong recovery of foreign tourism and thriving exports of energy-intensive goods and services (Figure 1.9). The current account balance, which became negative during the pandemic, is heading towards positive territory again, although rising exports are partly compensated by expanding imports, notably Icelanders travelling abroad again, and rising imports of capital goods. The terms of trade improved during the pandemic but are expected to worsen following the decrease of aluminium prices, the levelling off in seafood prices, and the increase in import prices. Net financial assets (or the net international investment position, i.e., the difference between Icelanders’ investments abroad and foreigners’ investments in Iceland), amounted to 39% of GDP in 2021, more than in most other OECD countries. Yet foreign direct investment (FDI) flows turned negative over the past few years, as opposed to most other OECD countries. Openness is deepening again as both exports and imports are expanding but it remains low in view of the country’s small size. Against this background, Iceland should continue to ease restrictions on foreign capital, to help fund investments in new sectors and in climate action.

Figure 1.9. External positions have improved, although foreign capital is shying away

Note: Panel B, Trade openness is measured as the average of goods and services imports and exports divided by GDP.

Source: OECD, Balance of Payments statistics; OECD, National Accounts database; OECD, FDI Statistics; and Statistics Iceland.

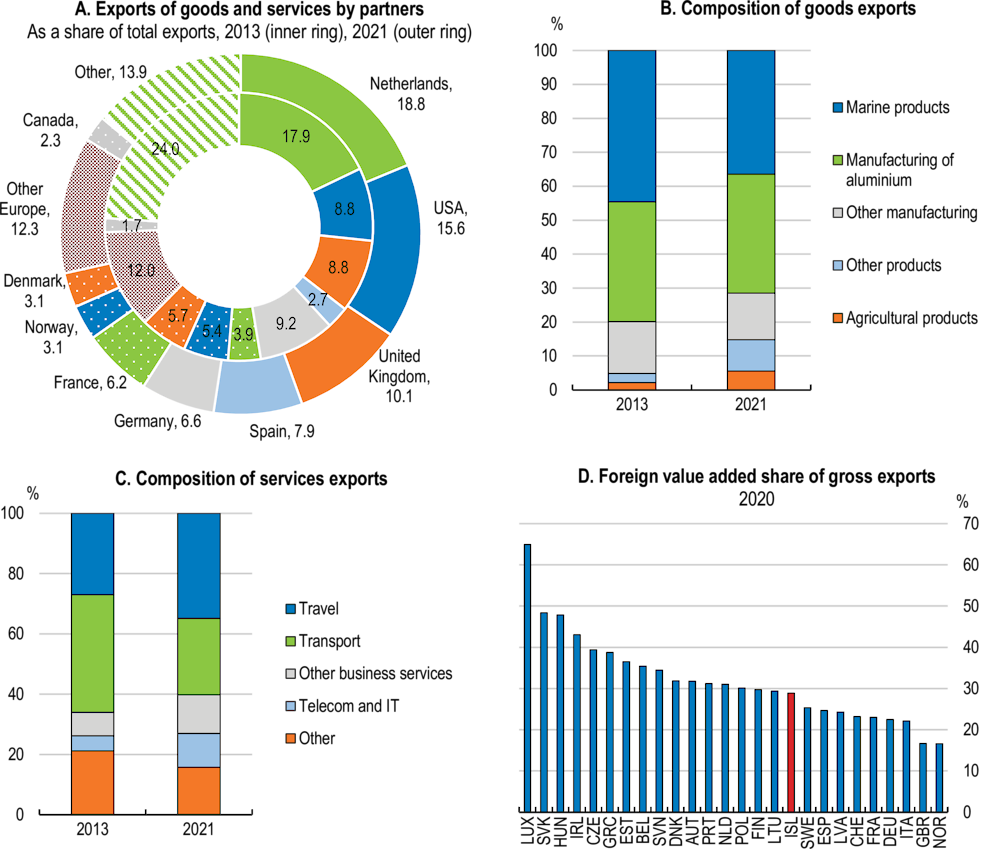

Exports and their destination countries are evolving gradually (Figure 1.10). The share of fisheries in total exports is declining but fresh and sustainably produced seafood is in ever higher demand. Aluminium exports remain key with the three smelters currently working at full capacity, benefitting from reliable domestic energy and stable energy prices. Tourism remains by far the most important service export. Non-traditional exports such as data processing, film production, software programming, and intellectual property revenue (e.g. pharmaceutical licences) are growing fast, helping to diversify the economy. However, the share of R&D-intensive exports remains low, as the fisheries, aluminium and tourism still dominate exports. The share of goods and services exported to Europe and the United States is increasing. Trade with Russia, Belarus and Ukraine was very limited before the war at around 2% of exports and 1% of imports.

Figure 1.10. The structure and destination of exports are evolving

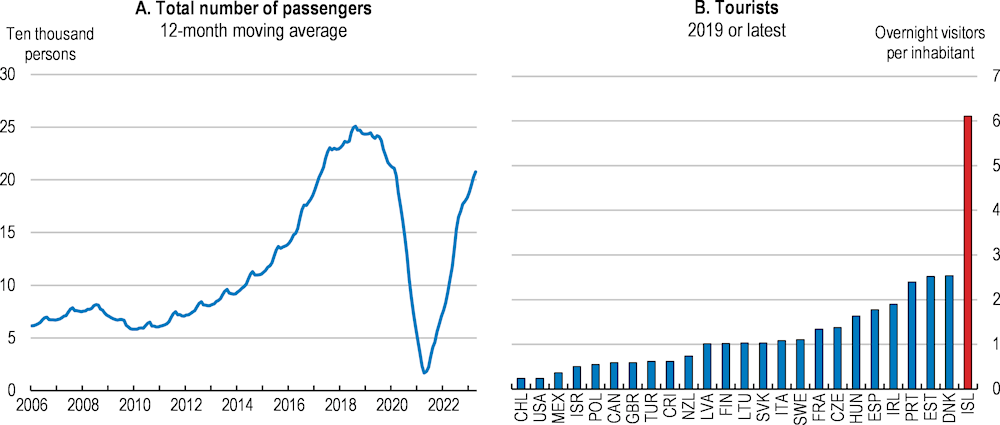

Tourism has largely recovered from the pandemic-inflicted collapse and might reach its sustainable potential soon (Figure 1.11). Value-added per tourist is rising as tourists tend to stay longer and spend more per stay, although tourism’s share in GDP remains below the 8% reached between 2016 and 2019. Iceland hosts more tourists per inhabitant than any other OECD country, exerting pressure on infrastructure and the environment. Climate change is altering a part of Iceland’s natural capital such as oceans and glaciers, jeopardising the supply of several tourism services (OECD, 2019[4]). Tourism remains concentrated in the Southwest region and along the South coast, where accommodation facilities are springing up even more rapidly than in other areas. Against this background, Iceland should continue to build on its 2019 policy framework for productive and sustainable tourism. A balanced tourism strategy – whose implementation was interrupted during the pandemic - should help improve productivity of tourism services; capitalise on the natural assets that form the basis of Iceland’s tourism sector; limit pressures on infrastructure and the environment; and aim for a geographically more even development across the country (OECD, 2022[6]). Iceland may take inspiration from New Zealand’s tourism policy framework to tap the rents generated by a fixed supply of natural capital (see also fiscal section) (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment of New Zealand, 2022[7]).

Figure 1.11. Tourism has recovered fast but may soon reach its sustainable potential

Note: Panel A, monthly number of passengers (12-month moving average) who go through security at Keflavík Airport, including foreigners residing in Iceland, foreign labour leaving the country and transit passengers. Panel B, data for 2019 except Finland (2018) and Sweden (2014).

Source: Statistics Iceland; and OECD, Tourism database.

1.3. Monetary and financial policies are being tightened

1.3.1. The central bank has reacted resolutely to the inflation spike

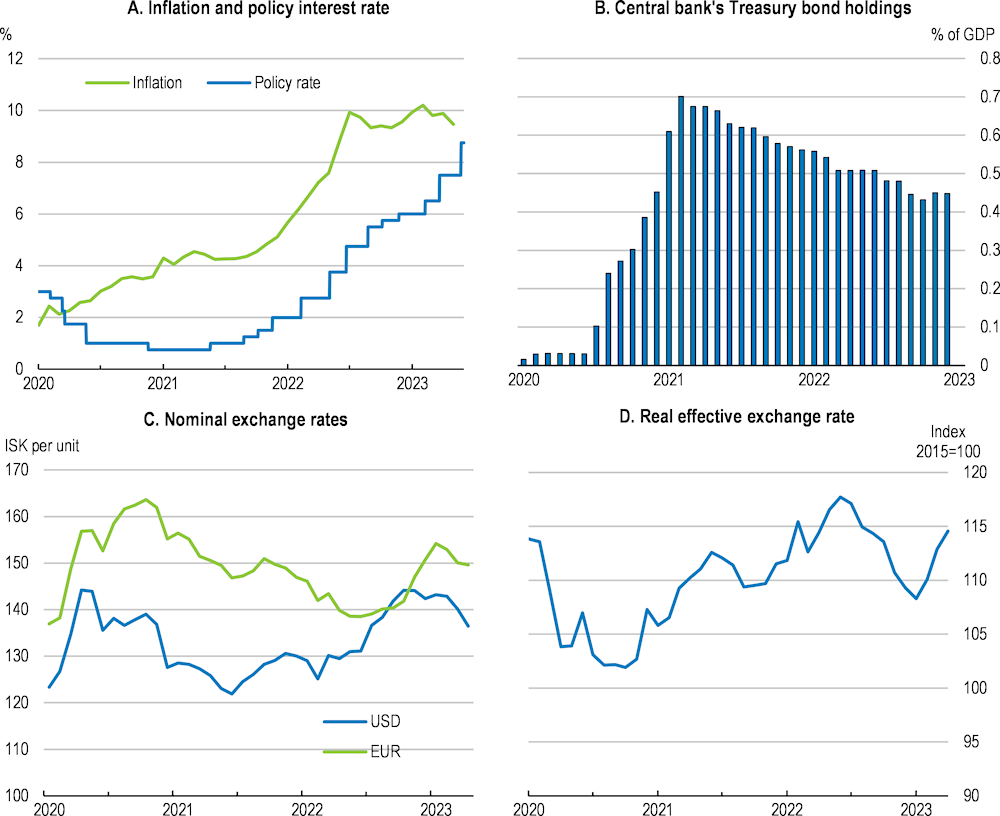

The monetary stance continues to be tightened (Figure 1.12). In May 2023, the central bank raised the key policy rate to 8.75%, the 13th increase since the cycle started in May 2021. Interest rates are 8 percentage points higher by now than two years ago, when they bottomed after the onset of the covid-19 pandemic. The central bank is also unwinding the balance sheet by divesting the proceeds of maturing treasury bonds (passive quantitative tightening). As such, treasury bond holdings have been declining from below 0.7% of GDP in mid-2021 to 0.4% of GDP by spring 2023. By international comparison, balance sheet expansion (quantitative easing) had played a minor role in the central bank’s pandemic-related toolbox, as treasury bond acquisitions amounted to 15% only of what had been planned initially (OECD, 2022[8]). Real interest rates as calculated from various measures of inflation and one-year inflation expectations have been rising by around 4 percentage points since mid-2022, currently standing at around 0.2%. The central bank considers that monetary transmission – i.e. the effect of interest rate changes on economic activity – still works through the usual household wealth, disposable income and labour market channels (Central Bank of Iceland, 2023[9]).

Figure 1.12. Monetary policy has been tightened

Note: Panel A, inflation refers to national headline CPI. Panel B, monthly holdings of central bank treasury bond holdings are divided by annualized and seasonally adjusted quarterly nominal GDP. Panel D, the real effective exchange rate is a CPI deflated measure of competitiveness. Rising values reflect declining price competitiveness.

Source: Central bank of Iceland; OECD, Consumer Prices database; and OECD, Competitiveness Indicators.

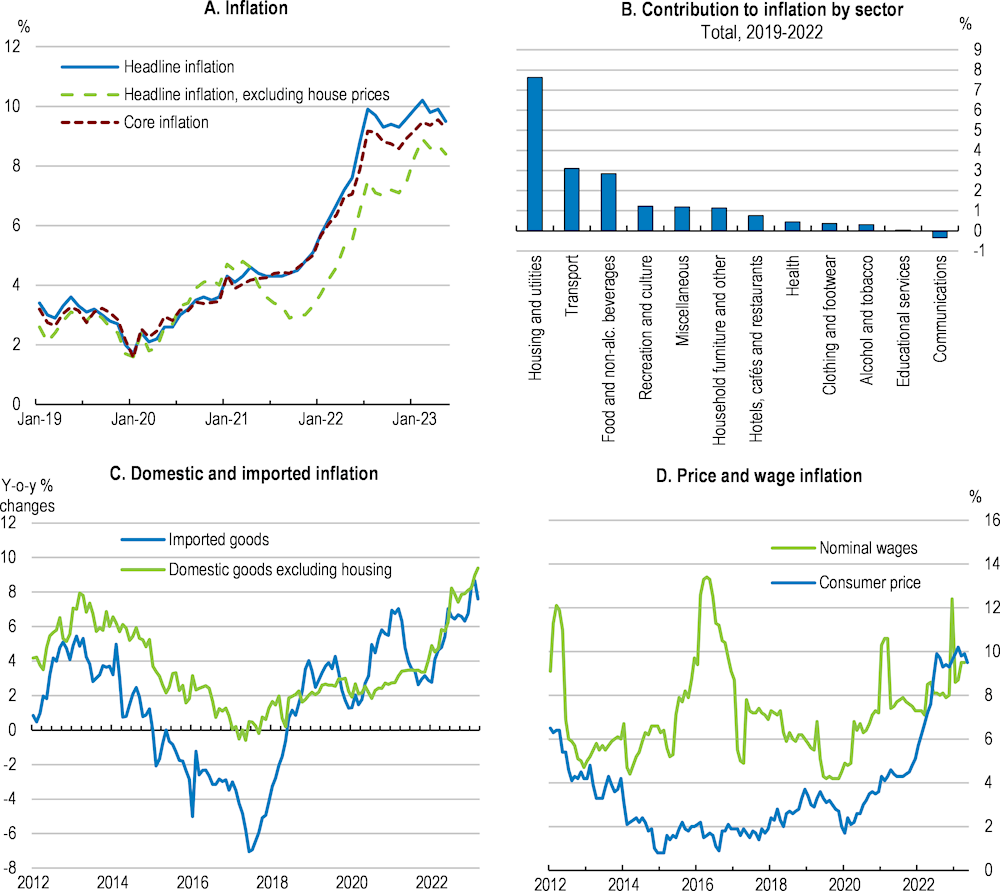

Inflationary pressures have been broadening (Figure 1.13). Headline inflation peaked at around 10% in early 2023 and has flattened since, remaining much above the central bank’s 2.5% target. Unlike in continental European countries, Iceland’s inflation surge was initially propelled by house prices, which shot up by around 50% between mid-2020 and mid-2022, largely driven by the strong post-pandemic recovery and labour immigration. Energy price inflation plays a small role as the country relies mostly on domestic energy sources. Inflation was then transmitted to the wider economy, notably the service sector. Core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices, is rising with a lag and becoming more broad-based. As such, the share of products in the consumer basket that have a year-on-year inflation rate above 6% has been gradually rising (Central Bank of Iceland, 2022[10]). The króna depreciated by around 10% against the euro and the dollar in the course of 2022, but strengthened somewhat during the early months of 2023. The exchange rate transmission channel – long a key driver of inflation in Iceland - has weakened significantly with rising credibility of monetary policy over the past decade (Edwards and Cabezas, 2022[11]).

Figure 1.13. Inflation has been broadening

Note: In Panels A and B, inflation refers to the national CPI. Panel B shows the weighted contribution of each spending item to overall inflation.

Source: Statistics Iceland; OECD, Prices database; and Bank of Iceland.

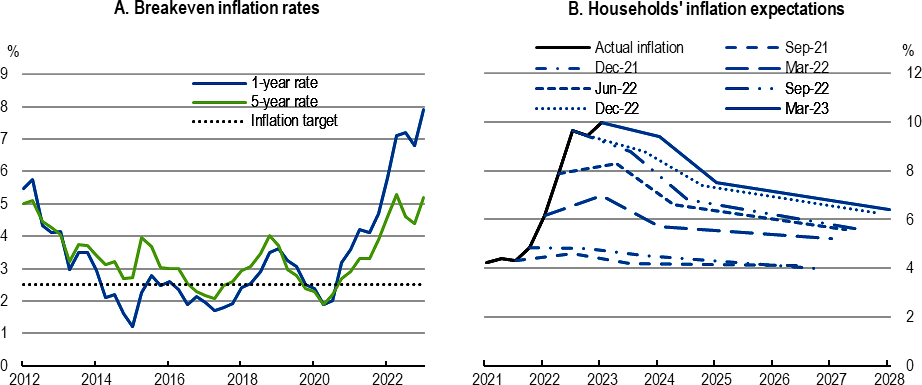

Long-term inflation expectations have ratcheted up (Figure 1.14). Since the start of the inflation spike, expectations have regularly surprised on the upside. The share of households and businesses expecting an inflation rate higher than 5% has risen sharply between late 2021 and late 2022, suggesting that expectations have detached from the 2.5% target. By the same token, the impact of inflation shocks on inflation expectations has risen, keeping long-term inflation expectations above the target (Pétursson, 2022[12]). Domestic inflation pressures are persistent as the labour market remains tight and the wage agreements of late 2022 and early 2023 are yielding annual wage hikes above productivity growth. Uncertainty is compounded by the fact that global factors and common shocks play a much larger role than in Iceland’s earlier cycles, making domestic inflation ever more wayward (Box 1.2).

Figure 1.14. Inflation expectations have de-anchored

Note: Panel B, inflation refers to national headline CPI.

Source: Central Bank of Iceland; and OECD, Consumer Prices database.

Against this background, the central bank should tighten further as needed to re-anchor expectations and to bring inflation back to the target. Tightening should take the impact of policy changes into account, as well as potential spillovers from policy in other countries given their impact on domestic inflation (Obstfeld, 2022[13]). Fiscal policy should work in the same direction as monetary policy while limiting support to vulnerable households. Finally, structural reform such as fostering a more friendly business climate and easing the conditions for foreign direct investment could help tame inflation and improve monetary policy transmission (see the section on the business climate).

Box 1.2. Inflation, and how to bring it down: lessons from Iceland

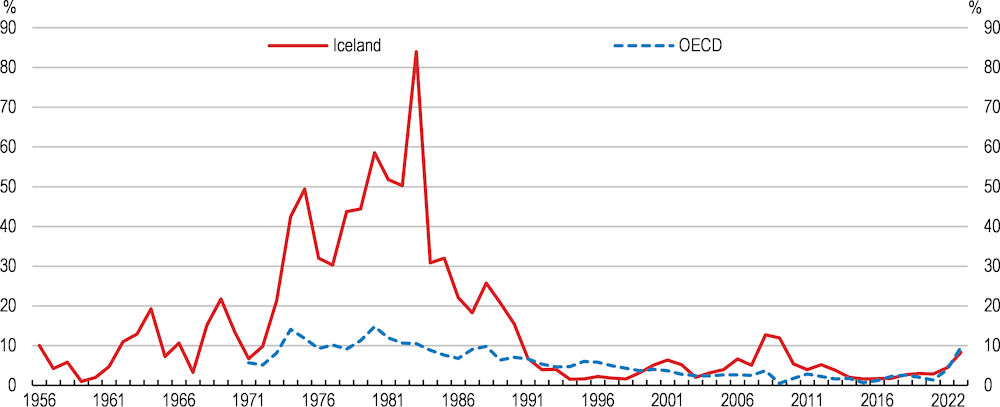

Iceland has a history of entrenched inflation and episodes of sudden inflation bursts that used to stand out among European OECD member countries. The factors most often cited to explain persistent inflationary pressures include Iceland being a small and volatile economy prone to shocks; sudden depreciations of the currency; poor coordination between monetary and fiscal policies; excessive wage increases; lacking competition between firms; flaws in financial market supervision; and low credibility of the central bank. Over the past three decades, policy reform has helped address many of these factors and bring inflation down.

Figure 1.15. Iceland’s inflation history

Annual headline inflation, 1956-2022, Iceland and OECD

Inflation hovered between 10% and 15% in the two decades following World War II and started to ratchet up afterwards. It spiked for the first time in the late 1960s when the collapse of herring stocks in the North Atlantic caused by overfishing triggered a financial and currency crisis. A vicious cycle of terms-of-trade shocks, devaluations and inflationary surges followed the fall of the Bretton Woods system and the oil crisis in the 1970s. Exchange rate management often transmitted rather than absorbed shocks. Indexation became entrenched in goods and labour markets as well as in the financial sector, fuelling a wage-price spiral. In the early 1980s, when inflation spun out of control, the talks at many family tables centred anxiously on how to cope with the price increases of the coming week. In the 1990s inflation fell to single-digit rates. The 2009 financial crisis and ensuing supply shock led to the penultimate inflation burst.

Multi-faceted policy reform helped tame inflation. In the 1980s and 1990s tighter and better aligned monetary and fiscal policies started to contain price pressures. The National Reconciliation Agreements of 1990 brought about a first concerted effort to restrain wage developments. Pro-competition regulatory reforms narrowed firms’ scope to pass cost increases onto consumers, and rising immigration eased pressure from the labour market, helping to flatten the Philips curve (see also Chapter 2). The 2001 reform of the monetary framework contributed to anchor inflation expectations by establishing a numerical inflation target. The new framework also forbade the central bank explicitly to finance government spending (monetisation). The creation of the Monetary Policy Committee in 2009 helped increase the central bank’s credibility. The fiscal framework adopted in 2015 helped reduce pressure from fiscal policy by setting numerical limits on government deficits and debt. Finally, cognisant of the close links between monetary and financial policies, a new macro-prudential framework was adopted, and the central bank and the financial supervisory authority were merged in 2019.

Source: (OECD, 1984[14]); (Andersen and Guðmundsson, 1998[15]; Central Bank of Iceland, 2017[16]; Olafsdottir, 2022[1]; Pétursson, 2018[17]; Þórarinsson, 2022[18].

1.3.2. The financial system looks resilient

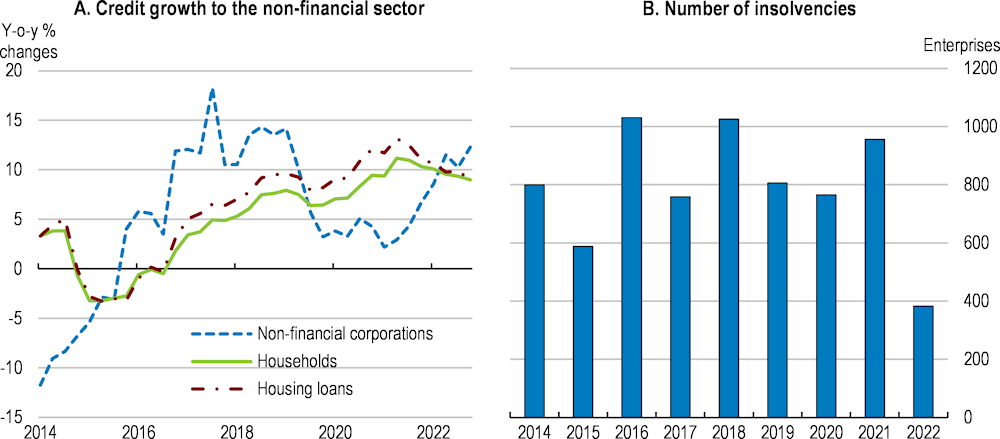

The financial system held up well in the face of the pandemic and remained largely unaffected by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the global energy crisis (Figure 1.16). Global financial risks have recently ratcheted up, however, with high-profile bank failures in the United States and Switzerland, increasing risks to Iceland’s domestic financial sector. Against this backdrop, corporate credit has been recovering vigorously from the pandemic, and household credit has continued to expand, albeit at a slowing pace. The number of insolvencies has been declining. The housing market shows signs of overheating, although house prices have started to decline in 2023. To address emerging risks, the central bank tightened macroprudential policy starting in 2022, increasing the counter-cyclical buffer in two steps from 0% to 2.5% by 2024 and lowering maximum loan-to-value and debt-service-to-income ratios on household mortgages, which is welcome. Corporate and household debt remain modest, providing ample buffers for shocks. The central bank should remain vigilant, considering potential repercussions of monetary policy – such as hikes of the key interest rate - on the financial system’s stability.

Figure 1.16. The financial system looks sound

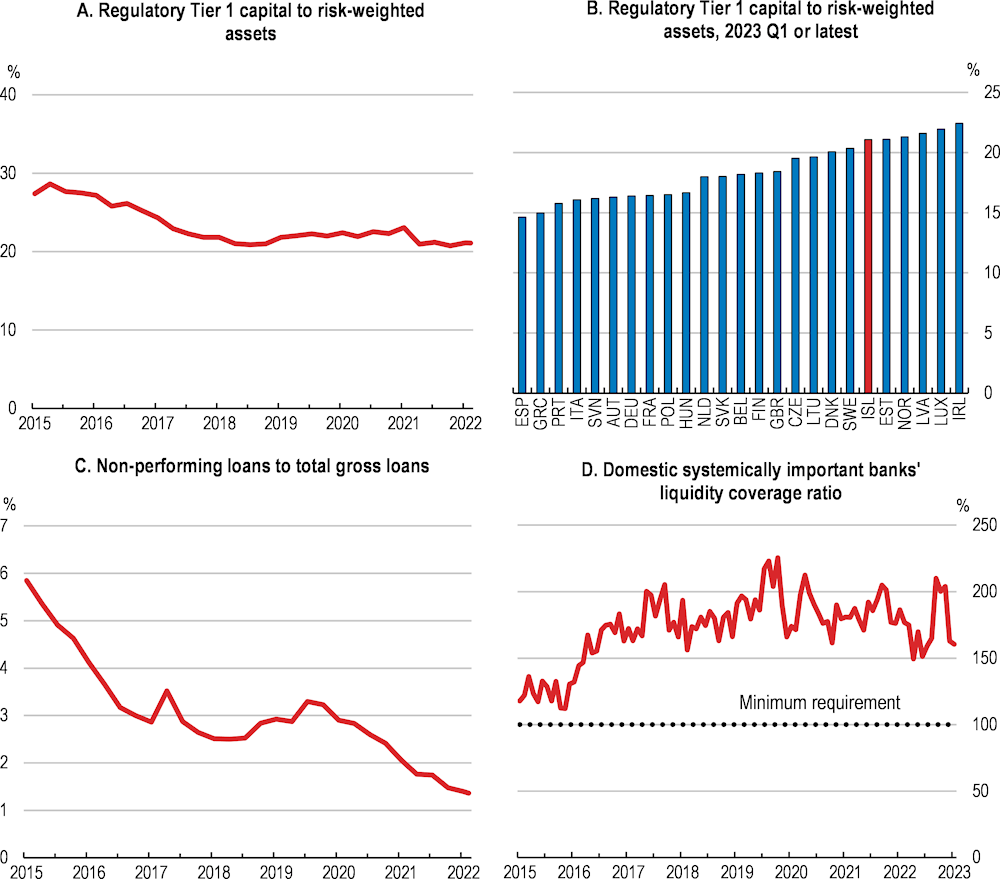

The banks seem well-capitalised and liquid, and bank profitability has increased. The regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets ratio has fallen but remains above most other OECD countries (Figure 1.17). Liquidity ratios have declined as both households and firms have been taking up more credit after the pandemic (not shown). The non-performing loans ratio continues to decline. The banking system is dominated by three domestic banks, which are considered systemically important. They are subject to additional macroprudential regulation and capital buffer requirements, to protect them better against shocks and improve the system’s resilience in case of a crisis. The capital adequacy ratios of these banks are well above regulatory requirements (Figure 1.17 D). Foreign banks’ presence in Iceland remains negligible.

Figure 1.17. Banks are well capitalised

ĺslandsbanki, the second-largest bank, has been partly privatised. A first tranche of 35% was sold in an initial public offering in summer 2021 and a second tranche of 23% was sold in spring 2022, leaving the government in a minority position, as recommended in the previous OECD Economic Survey (OECD, 2021[2]). Shares are mostly held by domestic investors, and among them a large part is held by pension funds (IMF, 2022[19]). Questions surrounding the reputation of a few small investors prompted the state auditor and the central bank to start investigations, and the sale of the third and final tranche, planned for early 2023, was postponed. However, the authorities still aim to conclude the privatisation of ĺslandsbanki during the current parliamentary term. Landsbankinn, which is one of the two other systemically important banks, remains in public hands. In April 2022 the government proposed to dissolve the state holding managing the public banks and to set up a new framework for state holdings of financial companies. The incident along the privatisation of ĺslandsbanki highlights the importance of vigilance in the process of selling public companies.

The role of the domestic financial technology sector (or fintech, including digital payment systems, crowdfunding and investment platforms, peer-to-peer lending platform operators, digital currencies, and fast data analysis) is gradually increasing but remains modest. Expanding fintech’s significance could foster competition in the financial sector (Central Bank of Iceland, 2022[20]). One concern for the authorities is that more than 90% of digital payments are routed via international payment card infrastructure, compromising its ability to maintain retail payment transactions in the case of disruptions, and first steps towards an independent domestic solution have been taken (Central Bank of Iceland, 2023[21]).

The government recently stepped up efforts to help the financial system underpin the transition towards a low-carbon economy. Climate change could have a considerable impact on the financial positions of Icelandic households and firms, including glacier retreat, shifts and reductions of fishing stocks, ocean acidification above the global average, and a rising risk of hazards such as landslides and floods. In 2021 the government set up a sustainable financing framework to support sustainable spending and investment (Government of Iceland, 2021[22]). In 2023 an annex on gender balance was added. While these efforts are welcome, the government should regularly monitor the efficiency of the sustainable financing framework.

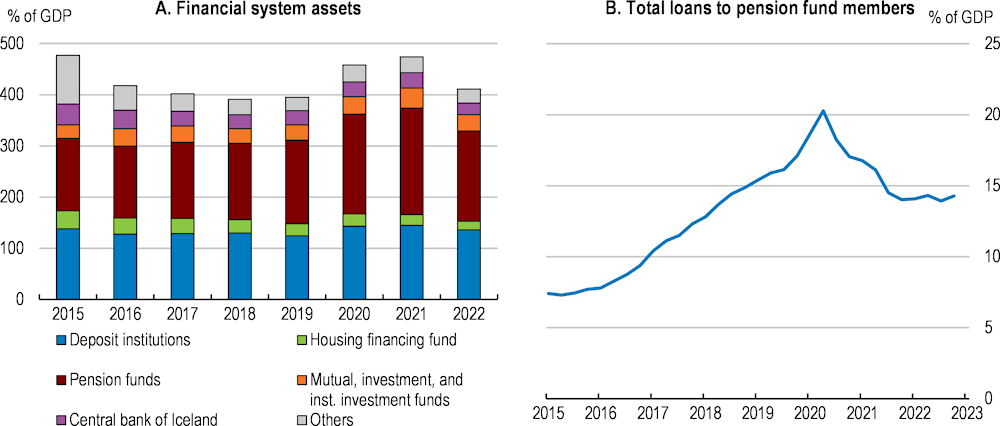

1.3.3. Pensions funds are systemically important

Pension funds have become systemically important within Iceland’s financial system. Pension funds' assets reached almost 200% of GDP by end-2022, up from around 150% in 2018 (Figure 1.18). The pension funds are a major source of household mortgage lending. They are also the largest investors in the domestic equity market and are among the largest owners of two of Iceland’s three systemically important banks (Central Bank of Iceland, 2022[23]). A 2022 reform allows the pension funds to gradually increase asset holdings denominated in foreign currency from below 50% to up to 65% of total assets, which is welcome as it reduces the funds’ exposure to developments in Iceland’s small and volatile economy. With Iceland’s pension funds having acquired a large part of the private shares of ĺslandsbanki, linkages with other financial institutions have deepened. Borrower-based macro-prudential tools have been uniform across pension funds and other financial institutions since these rules were introduced in 2017, limiting the scope for leakages and regulatory arbitrage.

Pension funds may act as a macroeconomic buffer but could also be the source of macroeconomic risks. To cover future pension benefits in a sustainable manner, pension funds are expected to reach a minimum yield - the “real reference rate” - of at least 3.5% on their assets, which is above Iceland’s potential growth rate of around 2.5%. In a low-yield environment, this obligation may lead pension funds to enter ever riskier asset classes (IMF, 2022[19]), although rising interest rates and the concomitant reduction of the net present value of long-term nominal liabilities could provide some relief (OECD, 2022[8]). Against this background, the authorities should closely monitor pension funds’ risk-taking, including through stress-tests. The intention to include pension funds in the CBI’s recently launched lending survey of financial institutions is welcome. Reducing the minimum real reference rate could be another, yet politically contested, option (see also fiscal section).

Figure 1.18. Pension funds have expanded

1.3.4. Cybersecurity and anti-money-laundering efforts are being stepped up

Cybersecurity issues have become more prominent, with several cyberattacks at financial institutions and payment services having caused disruptions (Central Bank of Iceland, 2022[20]). The number of severe attacks rose from two in 2019 to 14 in 2021, with risks growing further and spreading to non-financial and government institutions. Repeated or large-scale attacks could jeopardise financial stability, particularly if systemically important financial infrastructure is affected. The data cables linking Iceland and Europe could also become potential targets of a cyberattack. Against this background, the central bank considers cybersecurity as one of its top priorities. In 2021 the bank set up a cooperation forum on operational security of financial infrastructure and included cyber- and IT security as a priority in the central bank supervisory authority strategy for 2022-2024. Also, several business and consumer associations set up a campaign to raise public awareness of cyber-risks in daily digital payments. These efforts should continue and intensify.

Further progress has been made in strengthening anti-money-laundering and combating terrorist financing (AML/CFT) effectiveness. Iceland has addressed deficiencies identified in the 2018 Financial Action Task Force (FATF) report, is considered compliant or largely compliant with 38 out of 40 FATF recommendations and has been removed from the FATF’s “grey list” in 2021. Legal amendments in 2022 address money-laundering and terrorist financing risks related to virtual assets and asset providers and authorize the business registry to liquidate unregistered companies. The authorities conducted regular risk-based supervision and on-site inspections of obliged entities’ compliance with the AML/CFT Act - focusing on their IT systems - and implemented the guidelines on money-laundering and terrorist financing risk factors. Central bank data of foreign exchange transactions and cross-border flows is now available for other government entities to fulfil their AML/CFT roles. The risk-based control and monitoring of designated nonfinancial businesses and professions has been strengthened.

1.3.5. The housing market is cooling, but risks remain

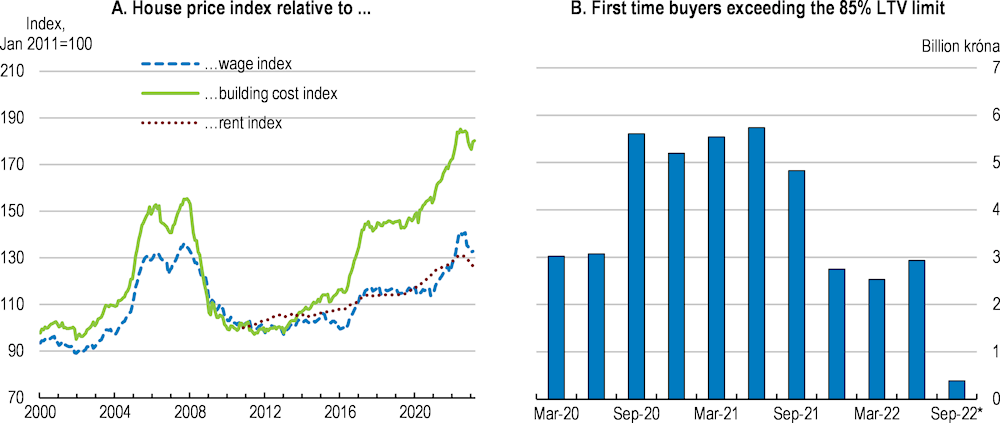

House prices and associated financial risks rose fast from around mid-2020 to mid-2022. Despite having remained stable since, house prices still diverge from fundamentals (Figure 1.19, Panel A). Favourable financial conditions during the pandemic, rapidly rising household income and credit, growing immigration and changing preferences – such as working from home - are among the reasons for the rise in housing demand and increasing mortgage debt, and more so than in many other OECD countries (Housing and Construction Agency, 2022[24]). The phenomenon is broad-based, with prices rising across Iceland and for all types of housing. The gap between house prices on the one hand and rents, wages and building costs on the other has widened considerably over the past few years.

The sharp increase in interest rates for new mortgages has cooled the housing market to some extent, but it also increased risks to the financial system. Debt service cost is rising, and the rollover of existing mortgages has become more difficult (Central Bank of Iceland, 2023[21]). The share of non-performing household mortgage loans is low and declining further, though. The central bank estimates that a tighter monetary stance prompts households to shift mortgage financing from non-indexed to indexed loans, but that such a shift does not compromise monetary policy’s capacity to affect household demand (Central Bank of Iceland, 2023[9]). Housing supply in the form of new construction and sales has started to rise, thereby cooling markets further, although it seems to remain below long-term needs, and housing affordability remains an issue.

Figure 1.19. The housing market has started to cool but prices remain high

Note: Panel B includes all new mortgage loans issued by systemically important banks and the Housing and Construction Authority. The nine largest pension funds are included from August 2020 onwards. Latest data is preliminary.

Source: Statistics Iceland; and Central Bank of Iceland.

In reaction to the overheating housing market, the central bank tightened several sector-specific macroprudential rules, to contain systemic risk and safeguard financial resilience. In June 2021, it lowered the maximum loan-to-value ratio for all but first-time buyers from 85% to 80% and in September 2022 for first-time buyers from 90% to 85%. The central bank also amended the maximum debt service-to-income ratios on consumer mortgages introduced in December 2021. Finally, in June 2022 accounting was refined by requiring a minimum interest rate, and the maximum maturities of indexed mortgages were tightened. Following these measures, the share of mortgages exceeding the LTV limits declined rapidly (Figure 1.19, Panel B). The central bank should assess the measures regularly and amend them if needed. Limiting or abolishing households’ entitlement to withdraw third-pillar pension savings on a tax-free basis could further help reduce pressures in the housing market.

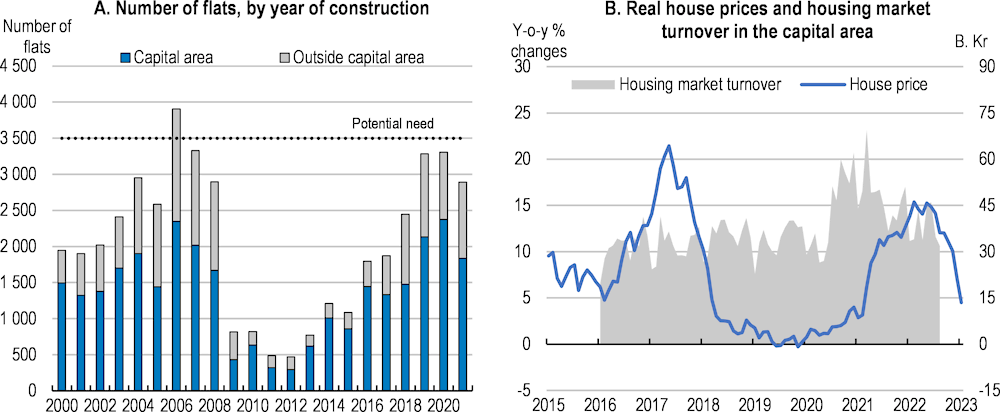

A key factor driving house prices is sluggish supply (Figure 1.20). Annual construction of new houses has been consistently below what is regarded as long-term demand of around 3 000-4 000 dwellings per year (Housing and Construction Agency, 2022[24]) (University of Iceland, 2022[25]). The construction sector took more than a decade to reach activity levels before the 2008/09 financial crisis, despite the strong recovery afterwards. As such, the number of dwellings per 1 000 inhabitants has fallen to one of the lowest levels of the OECD (OECD, 2020[26]). While building new houses takes time under any circumstances, a part of low supply responsiveness seems to be brought about by policy. Insufficient availability of land ready for construction, complex planning regulations, and a high administrative burden to obtain building permits could slow the provision of new housing. Insufficient construction could also be responsible for the rising share of households with difficulties to find affordable housing (see Chapter 2).

Figure 1.20. Housing supply reacts slowly to rising demand

Note: Panel A, number of flats listed in the Iceland Property Registry that have been allocated a construction year. Panel B, housing market turnover is expressed at constant December 2021 prices.

Source: Central Bank of Iceland.

Recent policy initiatives are paving the way for more reactive housing supply. In April 2023 the government published a green paper on a long-term housing strategy, ahead of a parliamentary resolution (Government of Iceland, 2023[27]). In July 2022 the government and the municipalities sealed a framework agreement on housing, which is a welcome starting point for further policy action (Government of Iceland, 2022[28]). Also, in 2022 the municipalities of the capital area agreed to improve coordination of land-use and infrastructure policy, and planning at the regional level has been strengthened, which is welcome given the importance of land-use governance for housing purposes (Cournède, Ziemann and De Pace, 2020[29]). The government could take further steps to address imbalances originating in the housing market. It could consider removing or further limiting households’ option to withdraw third-pillar pension savings on a tax-free basis, to reduce excessive housing demand. Housing support should be well-targeted at vulnerable households, to avoid that it just ends up in higher house prices and rents. The government, both at the central and local levels, should help step up housing supply, including sufficient affordable housing, by simplifying and clarifying planning regulations, easing the administrative burden of obtaining building permits, and by improving long-term planning and housing need forecasts.

1.4. Further fiscal tightening is needed

1.4.1. The budget balance is improving

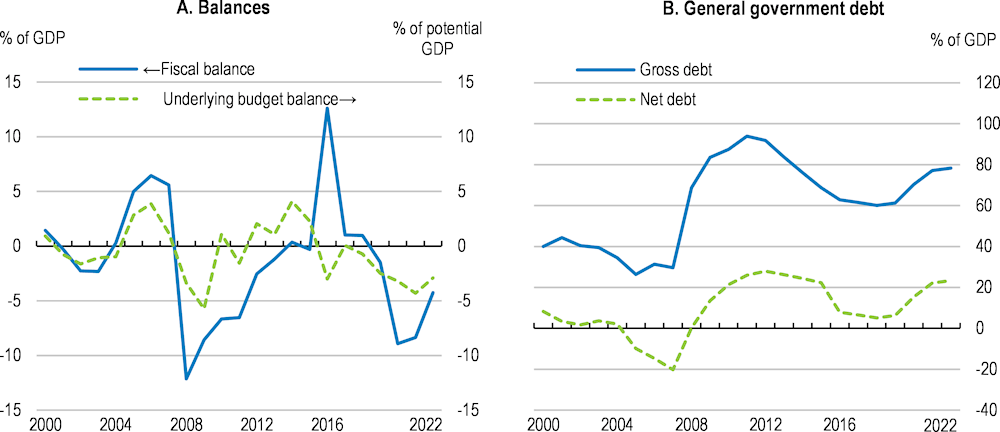

After the deep fall to -9% of GDP in 2020 following the outbreak of the pandemic, the general government fiscal balance recovered to -8% in 2021 and to around -4.5% in 2022 (Figure 1.21). A rapid exit from the pandemic has allowed to scale back fiscal support to households and firms, although interest expenditures are increasing slightly, partly because of rising indexation cost on inflation-indexed government bonds. Rapid growth after the pandemic-led contraction has buoyed tax revenues, lifting the fiscal balance in 2022 more rapidly than projected. The fiscal stance has become contractionary, after the strong pandemic-related expansion in 2021 and 2022. Gross public debt following National Accounts rules rose from around 61% of GDP in 2019 to around 78% in 2022. Net debt is low at around 23% and there is hence a considerable difference between gross and net debt, like in some other OECD countries such as Canada (OECD, 2023[30]). In Iceland’s case, it is due to large and liquid government financial assets held at the central bank, suggesting that net debt can be an appropriate metric to measure fiscal sustainability. Contingent liabilities, largely owing to debt of the Housing Financing Fund – a government-owned mortgage lender - continue to decline, reaching 24% of GDP at the end of 2022.

Figure 1.21. Fiscal deficits have begun to shrink

Note: Reflecting differences in the treatment of public entities, contingent liabilities and pension funds, the National Accounts and Statistics Iceland measures of public debt differ.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook No. 113 database.

Going forward, the fiscal plan 2024-28 projects to reinstate the fiscal rules in 2026. The fiscal deficit is planned to decline gradually until it is close to zero by 2027, and the debt-to-GDP ratio is planned to decline slightly in 2026. To reach that target, the government plans to limit real spending growth at around 1% per year. The government also plans to unwind the Housing Fund with a view to eliminate the risk that guarantees for the fund’s debt will be called upon in the future (Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs, 2022[31]). Public consumption and transfers as a share of GDP are planned to decline to pre-pandemic levels by 2027. Several tax measures – notably an automatic adjustment of income tax progression thresholds to inflation and productivity growth – will slow tax revenue increases and keep the tax-to-GDP share roughly constant (see tax section). These plans are broadly welcome, although a more rapid return to a balanced budget would be preferable to rebuild fiscal buffers faster. Also, in view of the current account deficit and with inflation running high, fiscal policy should avoid any stimulus, thereby ensuring consistency with monetary policy.

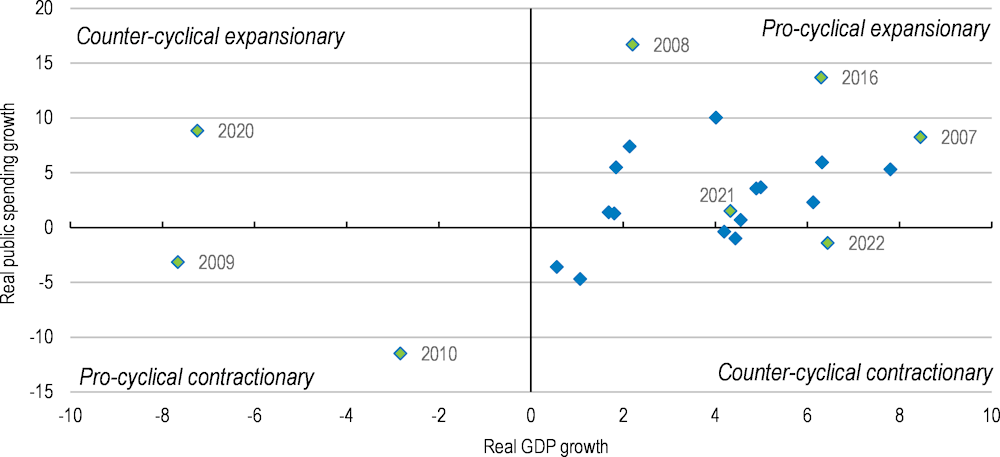

Government spending tends to be procyclical, i.e., it is expanding and contracting at times that are inappropriate from a stabilisation perspective, as in several other OECD countries (Egert, 2010[32]). On average, annual spending expands more the faster the economy grows (Figure 1.22). Spending was highly expansionary in the run-up to the financial crisis of 2008/09, while being contractionary afterwards. Overall, spending policy has been pro-cyclical more than two-thirds of the time since the turn of the millennium. Spending became more neutral in the years around 2015, when the new fiscal framework was adopted (Box 1.3), and in the face of the pandemic, but it has become pro-cyclical again during the post-covid-19 recovery. Against this background, the government should consider complementing the fiscal framework with a spending rule. While spending rules tend to add complexity to the fiscal framework and reduce budget flexibility, they can help making fiscal policy both more sustainable and stable. Around half of all OECD countries have implemented spending rules in addition to a deficit and debt rule (Rawdanowicz et al., 2021[33]). After pro-cyclical spending drift in the late 2000s, particularly at the local level, Denmark introduced a rolling four-year general government expenditure rule. A recent evaluation suggests that the spending rule helped contain spending pressure, while allowing the automatic stabilisers to work fully (Danish Ministry of Finance, 2022[34]). More recently, Ireland introduced a spending rule in 2021, requiring spending to remain below trend growth.

Figure 1.22. Spending tends to be procyclical

Note: Public spending refers to real general government total disbursements, using the GDP deflator.

Source: OECD, National Accounts database.

Box 1.3. The fiscal framework has served Iceland well, but procyclical spending remains an issue

The 2015 reform of the public finance law aimed at addressing the twin problems of excessive fiscal deficits and procyclicality which had plagued Iceland for long. The government adopted numerical fiscal rules, established an independent fiscal council, and reorganised the budgeting process. The two numerical fiscal rules consist of first, two budget balance rules, requiring the annual deficit to remain below 2.5% of GDP, and the budget to be balanced over a five-year period; and second, a debt rule requiring net debt (national definition) exceeding 30% of GDP to be reduced by 5% on average over three years. The rules are quite straightforward, facilitating budgeting in a volatile economy when potential output is difficult to gauge.

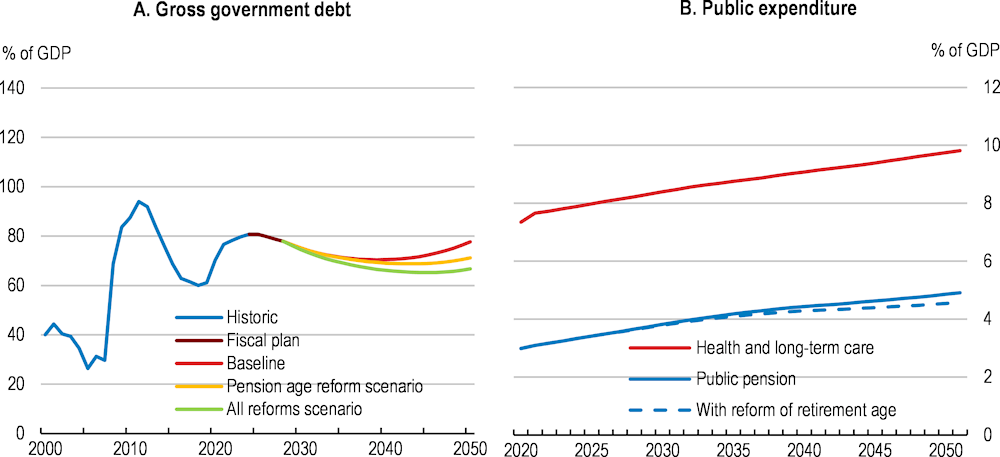

The fiscal framework has helped Iceland to improve budgeting. The framework provides guidance about the medium-term trajectory of the public finances and hence mitigates concerns about debt sustainability. It could however be strengthened further, especially as some scenarios point to a rising debt burden, notably because of the long-term rising cost of ageing, notably spending on health and long-term care (Figure 1.24). Moreover, government spending remains pro-cyclical, as described in the main text. Against this background, complementing the budget framework with an expenditure rule could help increase both the sustainability and stabilisation properties of fiscal policy in Iceland.

Source: Fjármálaráð, 2022[35], von Trapp and Nicol, 2018[36].

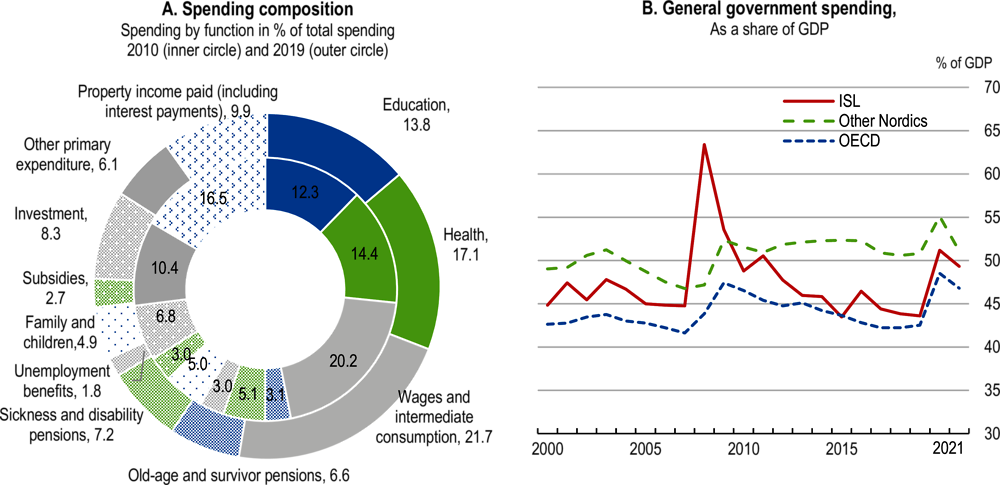

1.4.2. Public spending quality has room to improve

Spending as a share of GDP has changed little over the past decade or so, except for the rapid increase in 2020 following the drop in GDP and the government’s pandemic-related fiscal support programmes (Figure 1.23). Yet, the composition of spending has evolved, mainly because of the rising share of spending on pensions. Child and family benefits – which tend to boost growth – only grew slightly. Public investment has been expanding. Finally, pro-cyclical cuts in growth-enhancing public spending during downturns could have been detrimental to growth (Fournier and Johansson, 2016[37]).

Following the covid-19 pandemic, whether some of the recent shifts in spending are structural or permanent is an open question. Some developments will have reversed in 2021 or 2022. Unemployment-related benefits and health spending, which jumped during the pandemic, contracted, and spending on subsidies that helped firms to survive lockdowns and other restrictions were cut back. Under these circumstances, the government should continue to aim for public spending that underpins growth, using more spending reviews and building on the experience gained. Again, fiscal policy should turn more counter-cyclical, to support the move towards higher spending quality.

Figure 1.23. Spending quality has declined

1.4.3. Ageing costs will increasingly weigh on the budget

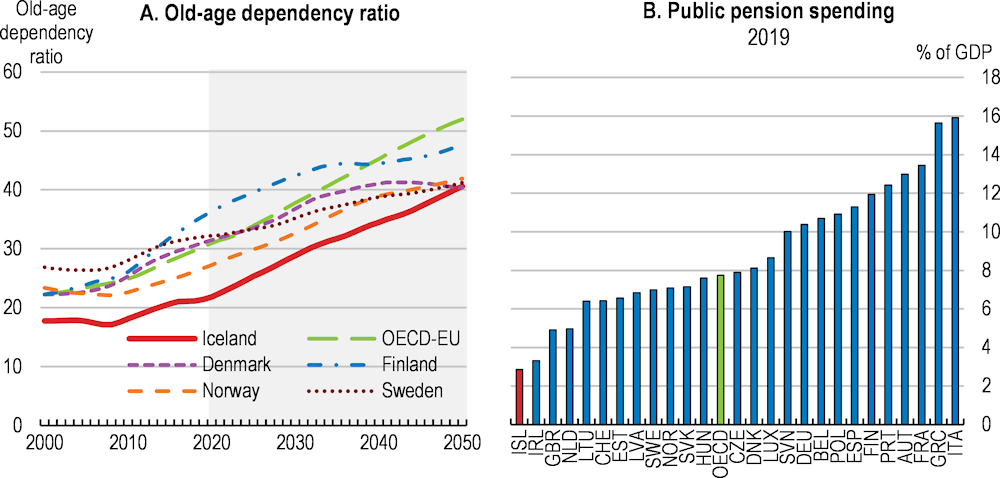

Iceland’s population is young and growing fast, owing not least to considerable labour immigration. Healthy life expectancy is one of the highest in the OECD, both for men and women. The work life is long with the statutory retirement age at 67 years, and older workers are well-integrated into the labour force. The pension system is sustainable, well-funded and diversified, comprising means-tested pay-as-you go state pensions (first pillar), statutory private funded pensions (second pillar) and individual tax-favoured savings (third pillar). Public spending on pensions as a share of GDP is the lowest in the OECD (Figure 1.24 B). Incentives for early retirement are weak, keeping participation high and pension spending under control. In this context, ageing is currently less of an issue than in almost any other OECD country.

Figure 1.24. Spending on pensions is small, but ageing costs will rise

Note: Panel A, the old age dependency ratio is the number of individuals aged 65 and more to the population aged between 15 and 64. Panel B, public pension spending refers to total public cash benefits spent on old age and survivors.

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2022), World Population Prospects 2022, Online Edition; and OECD, Social expenditure database.

The country will not escape the economic and fiscal impact of ageing, however. The old-age dependency ratio is expected to rise as population growth slows and the share of active cohorts contracts (Figure 1.24 A). The government projects the fiscal cost of ageing to rise by more than 3% points of GDP until 2050, mainly because of higher spending on health and long-term care, although the lower cost of educating the young is expected to partly compensate the rising cost of ageing (Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs, 2021[38]). The government assumes that the system of funded pensions will not require additional public funding since an in-built sustainability mechanism will adjust benefits for each age cohort, keeping the system overall sustainable. It also expects that the spending share of the state pension system will remain stable – and even decline from around 2035 – even though that share has almost doubled from 1.5% to 2.9% of GDP since 2010, partly because of a revision in 2017 that increased replacement rates. Health spending is expected to expand with life expectancy, jointly with growing incomes and technological progress. Against this background, the government should address the fiscal cost of ageing now to avoid imbalances later. One option could be to link the retirement age to life expectancy to keep the share of life spent in work and retirement roughly constant and hence allow for small incremental increases every year, as in Finland or, recently, the Netherlands (OECD, 2021[39]).

The need for and the cost of long-term care (LTC) is expected to grow as the number of people above 80 years will expand along with the prevalence of dementia over the coming decades. The cost of LTC as a share of median household income is below the Nordic average but unlike for most other OECD countries institutional care is more expensive than individual home care (Hashiguchi and Llena-Nozal, 2020[40]). As such, the government should address rising LTC cost by adequate reforms, notably by strengthening individual home and family care. While helping to contain cost, LTC reforms could also help people stay more independent into old age.

Overall, Iceland’s long-term debt profile depends on the implementation of structural reform, including linking the retirement age to life expectancy (Figure 1.25). In a baseline scenario with no reforms to address rising ageing costs, gross government debt would reach around 78% of GDP by 2050, similar to where it stands now. Age-related costs comprising health, long-term care and first-pillar state pensions will rise by 5% of GDP (from 10% to 15%). In a scenario where ageing costs are addressed by introducing an automatic link between the retirement age and life expectancy, debt will decline as labour participation will be higher and growth stronger. In the full-reform scenario, with implementation of all structural reforms recommended in Table 1.5, debt would stabilise below 70% of GDP. Reform progress in the financial and fiscal domain is shown in Table 1.3.

Figure 1.25. Reform could help contain spending and stabilise debt

Note: Debt projections until 2028 follow the fiscal plan as published in March 2023. The baseline reflects rising state pension (first pillar), public health and long-term care spending obligations, assuming an unchanged replacement rate for state pensions. The “pension age reform scenario” reflects the positive effect of linking retirement age to life expectancy by a factor of two-thirds, while the “all reforms scenario” shows the effects of reforms shown in Box 1.5, subtracted from the baseline. Based on Guillemette et al. (2017).

Source: OECD Economic Outlook No. 112 database; and OECD calculations.

Table 1.3. Past recommendations and actions taken in monetary, financial, and fiscal policies

|

Recommendations |

Actions |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Monetary and financial policies |

||

|

Keep monetary policy accommodative, but stand ready to tighten if long-term inflation expectations are rising |

After the burst of inflation, monetary policy has been tightened substantially since mid-2021. |

|

|

Fiscal policy and public finance |

||

|

Continue supporting the recovery, including by providing liquidity support for distressed, yet viable firms. |

All support measures have been withdrawn. |

|

|

Ensure that the planned investment in infrastructure, education, innovation and digitalisation is properly implemented. |

Investment in these areas continues as planned, although more could be done in education. |

|

1.4.4. Tax levels are average but marginal tax rates are high for working families

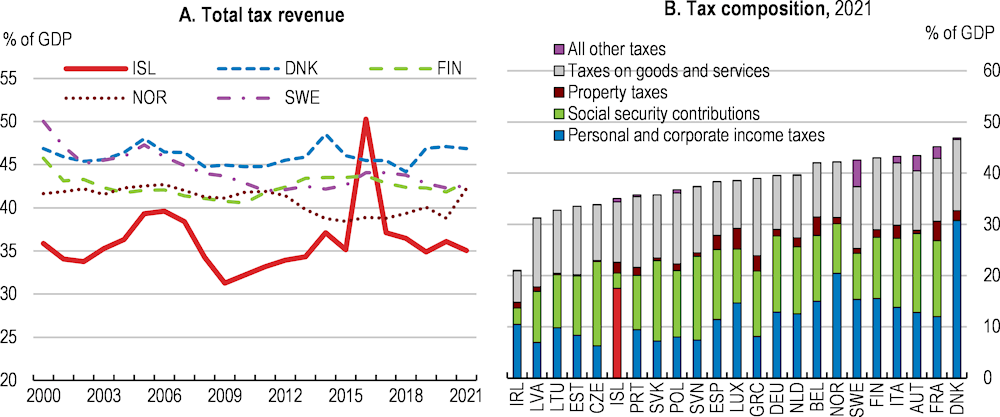

The government thoroughly overhauled the income tax system in 2019-22 as described in the past Survey. A notable measure is an automatic annual adjustment of the income tax brackets for inflation plus 1% for productivity growth, akin to a fiscal rule. The productivity adjustment keeps the share of taxpayers per tax bracket roughly constant by curtailing unwarranted tax hikes as real wages grow economy-wide, thereby avoiding real progression. The measure aligns with practices in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (OECD, 2023[41]). Several tax reliefs for innovation (see also innovation section), green investment, inheritance and charity were introduced or widened. The VAT relief for electric cars is set to expire at the end of 2023, to be replaced by a direct subsidy (OECD, 2021[2]). Yet, at 46%, the overall VAT revenue ratio (the ratio of actual collection to what is theoretically possible) remains below the 56% OECD average. Most covid-related tax reliefs have been withdrawn except the hotel tax which is planned to be reinstated in 2024. The overall tax burden is below the OECD and tilted towards personal income (Figure 1.26). The government should further reduce tax expenditures, notably reinstate the standard VAT rate in the tourism sector. It should also introduce a tourism levy to fund local sustainable development, as in New Zealand (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment of New Zealand, 2022[42]).

Figure 1.26. Taxation is around the OECD average and relies heavily on income

Note: Panel B, the spike in 2016 reflects revenues from the “exit tax” levied on creditors reclaiming assets from banks that had defaulted in the 2008/09 crisis.

Source: OECD, Global Revenue Statistics database.

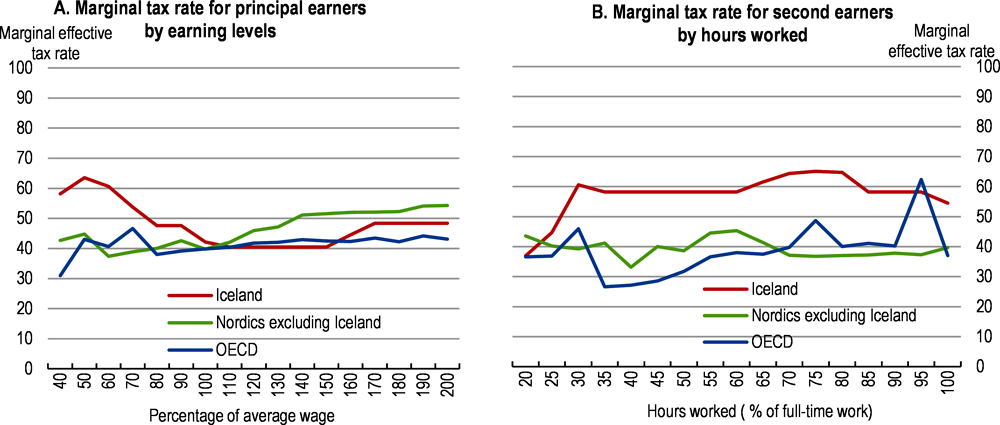

Marginal tax rates are relatively high, which is the combined result of a progressive tax system and strong means-testing of social benefits, notably for child and family benefits (Figure 1.27). While strong means-testing makes fiscal support to households well-targeted, the resulting high marginal tax rates could discourage low-income earners from seeking to earn more. Unlike in other Nordic countries, the disincentives extend far into the group of middle-income households (OECD, 2019[4]). The system of “tax bracket sharing” (a specific Icelandic form of taxing family rather than individual income) implies that Iceland has the highest marginal income tax rates for second earners in the OECD (OECD, 2022[43]). Also, strong tapering of benefits could be one factor driving the large gap in working hours between men and women, or having slowed its decline over the past decade (see Figure 1.6). A recent reform of the child and family benefit system extends benefits to middle-income earners and reduces marginal tax rates (Government of Iceland, 2022[44]). Against this background, the government should abolish “tax bracket sharing”. It could also continue to taper child and family benefits less and gradually move towards a universal child and family benefit, as in all other Nordic countries and as Lithuania did in 2018, complementing an extant means-tested instrument.

Figure 1.27. Marginal tax rates are high

Note: The marginal effective tax rate (METR) is computed according to the formula for a two-earner couple with 2 children, claiming social assistance and housing benefits, whenever eligible. Annual housing costs are set at 20% of average wage of Iceland. In both panels, the second earner earns 67% of the average wage of the first earner.

Source: Own calculations based on output from the OECD tax-benefit model, version 2.5.0.

Altogether, the fiscal recommendations would improve the budget balance by 0.5% of GDP (Box 1.4).

Box 1.4. Quantifying fiscal policy recommendations

The following estimates roughly quantify the fiscal impact of selected recommendations within a 5 to 10-year horizon, using simple and illustrative policy changes. The reported effects do not include behavioural responses and growth effects.

Table 1.4. Illustrative fiscal impact of recommended reforms

|

Policy measure |

Impact on the fiscal balance, % of GDP |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Recommendations |

||

|

Child and family benefits |

Move from means-tested towards universal child and family benefits |

-0.4 |

|

Carbon pricing |

Increase carbon taxes to levels consistent with reaching climate targets, and redistribute proceeds to households and firms or use them to support green investment |

0.0 |

|

Retirement age |

Establish an automatic link between the retirement age and life expectancy by a factor of two-thirds |

+0.3 |

|

Value-added tax |

Terminate the lower VAT rate for tourism, which would increase the VAT revenue ratio from 0.46 to 0.49 |

+0.5 |

|

Total fiscal impact |

+0.4 |

|

Note: The following recommendations are included in the structural quantification, but their fiscal impact cannot be quantified: regulatory reform in tourism, construction, and professional licensing; power sector; control of corruption.

Source: OECD own calculations.

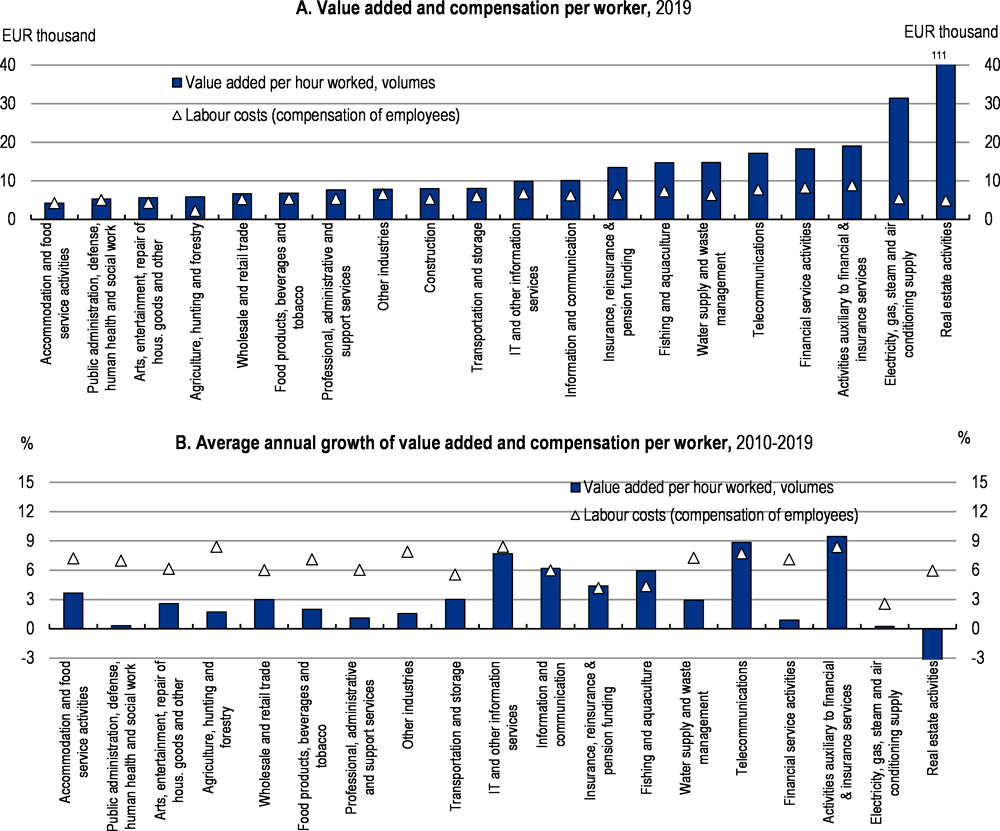

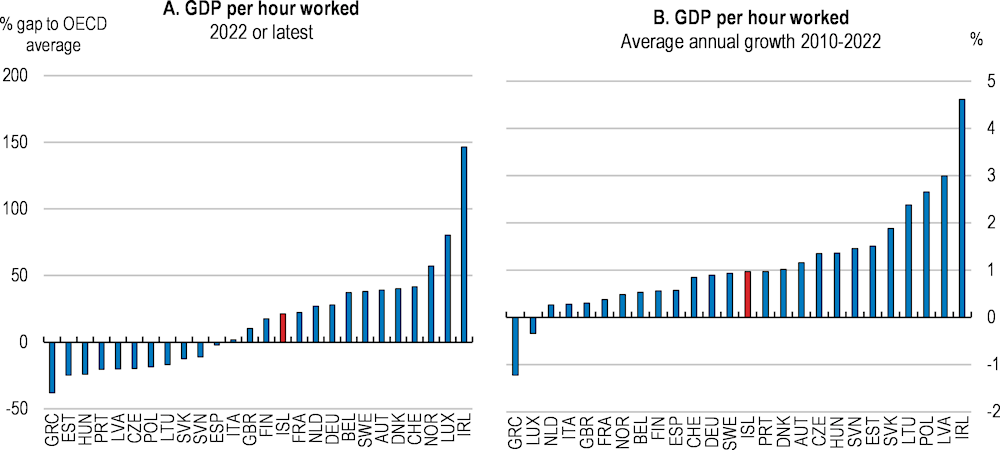

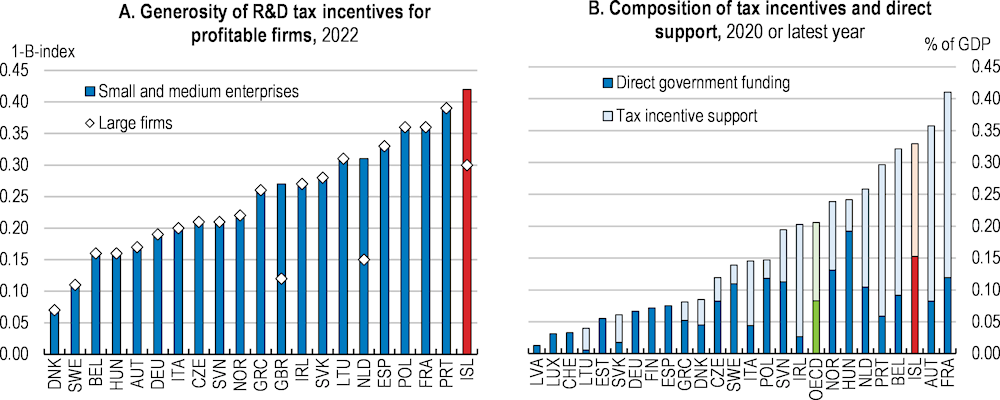

1.5. The business climate should improve to raise productivity

Labour productivity has grown by around 1% each year on average, close to OECD-wide growth, maintaining productivity at roughly 20% above the OECD level (Figure 1.27). Productivity growth accelerated in the late 2010s but slowed again after 2019 in the wake of several supply shocks and the pandemic (OECD, 2021[2]). It remains lacklustre in the domestic goods and services sector (Figure 1.7). Reforms to improve the business climate have been limited despite some action in the tourism and construction sectors. Stepping up regulatory reform efforts could help attract new and innovative firms, diversify the economy, and raise productivity to sustain high wages. Structural reform could raise GDP per capita by up to 5% (Box 1.5).

Box 1.5. Quantification of structural reforms

Selected reforms proposed in the Survey are quantified in the table below, using simple and illustrative policy changes and based on both cross-country and single-country regression analysis. Some reforms are not quantifiable under available information or given the complexity of the policy design. Most estimates rely on empirical relationships between past structural reforms and productivity, employment and investment, assuming swift and full implementation. They do not reflect idiosyncratic settings in Iceland. Hence, the estimates are merely illustrative, and results should be interpreted with care.

Table 1.5. Potential impact of structural reforms on per capita income

|

Policy |

Measure |

10 year effect, % |

|---|---|---|

|

Retirement age |

Link retirement age to life expectancy by a factor of two-thirds |

1.1 |

|

Regulatory reform in tourism and construction, and in professional licencing |

Strengthen competition in the domestic sector further, notably in tourism and construction, and ease stringent licensing in the professions |

1.0 |

|

Power sector |

Set up a transparent electricity wholesale market coordinated by an independent operator |

0.8 |

|

Taxes and social benefits |

Reduce marginal tax rates for second earners |

1.1 |

|

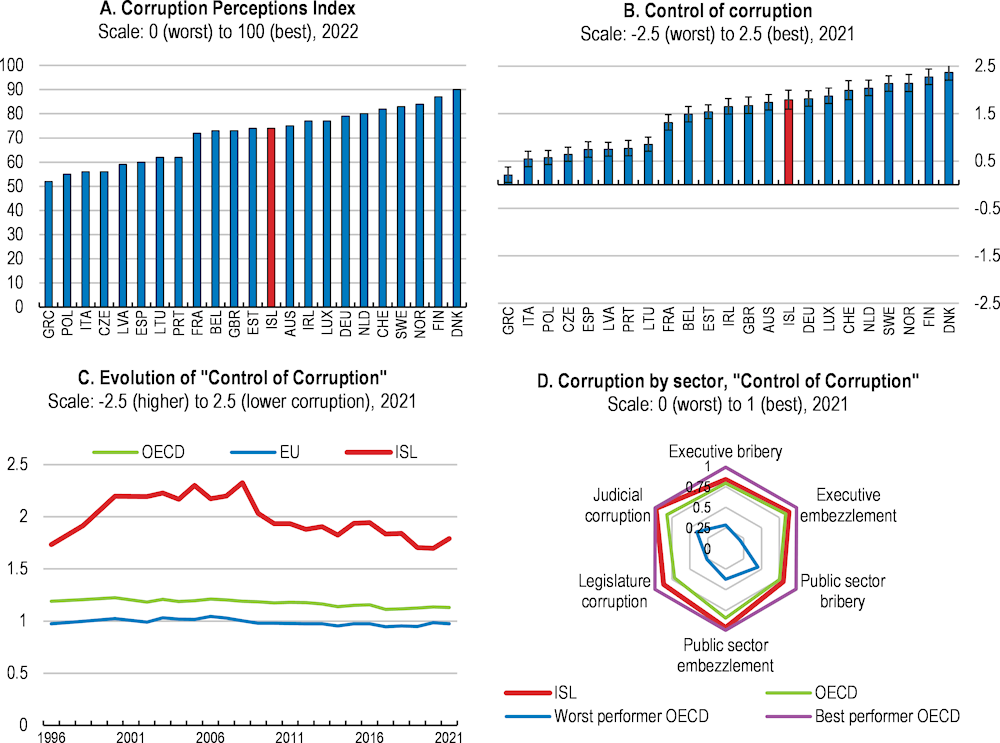

Control of corruption |

Increase control of corruption by 0.1 indicator points to reach average scores of 2010-16 |

0 to 0.7 |

|

Carbon taxation |

Increase carbon taxation to a level commensurate with achieving climate objectives |

-0.3 to -0.6 |

Note: Lower marginal tax rates for second earners are achieved by introducing a universal (rather than a means-tested) child and family benefit, as reflected in the fiscal quantification (Box 1.4). The following recommendation is included in the fiscal quantification, but the impact on per capita income cannot be quantified: terminate the reduced VAT rate in tourism.

Source: OECD calculations based on Égert and Gal, 2017[45], Cournède, Fournier and Hoeller, 2018[46], OECD, 2020[47] and Blöchliger, Johannesson and Gestsson, 2022[48].

Figure 1.28. Labour productivity has been rising by around 1% per year

1.5.1. Barriers to entry are considerable

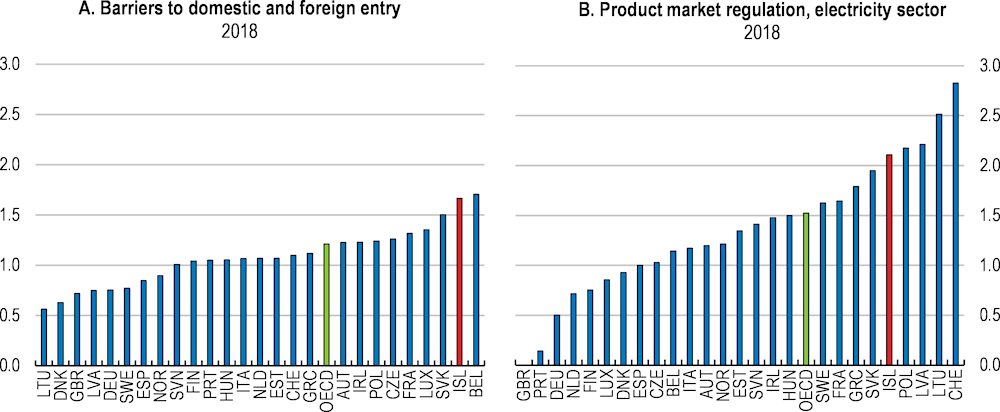

Notwithstanding improvements, Iceland’s business climate as measured by the OECD’s product market regulation indicators remains rather unfriendly. While distortions induced by direct state involvement in business activities are small, barriers to entry, notably for start-ups, are high. Foreign access to the computer service and construction sectors is more restricted than in any other OECD country, according to the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI), partly because of restrictions on non-EEA companies (OECD, 2022[49]). Over the past few years reforms opened the tourism and construction sectors to more competition, as recommended in the past Survey (OECD, 2021[2]) and the report commissioned by Iceland’s government (OECD, 2020[47]). Moreover, a simplification of building regulations is planned. However, professional licencing requirements were hardly eased as attempts met with resistance from vested interests. In this context, the government should continue its efforts to improve the business climate. A new attempt to reform professional licencing is planned for 2023.

Figure 1.29. The business climate is rather unfriendly

Note: A higher indicator value means more stringent regulation.

Source: OECD, Product Market Regulation database.

The electricity sector is unique given Iceland’s peculiar geography and geology. Domestic power generation relies on hydro and geothermal. The power grid is physically separated from the networks in Europe and the United States, restricting the pass-through of foreign energy market imbalances. The sector is mostly state- and municipally-owned and in part vertically integrated, even though it follows EU minimum regulatory requirements since 2003 (Box 1.6). Productivity increases in the sector over the past ten years have been close to the OECD average. The Competition Authority expressed concerns that a reform standstill could slow innovation in the sector, notably wind farm technology which could help meet rising electricity demand in an efficient and environmentally sustainable manner. Against this backdrop, regulatory reform, notably a transparent wholesale market coordinated by an independent operator, should form the core of a productive and competitive power sector (OECD, 2022[50]). The network operator Landsnet plans to set up a wholesale market by the end of 2024.

Box 1.6. Ownership and market structure in Iceland’s power sector

Iceland’s electricity sector is mostly owned and operated by publicly owned companies and in part vertically integrated, unlike many other countries where transmission grids are operated by independent transmission system or network operators (ownership unbundling). Landsvirkjun is the largest production company, generating around 71% of electricity, followed by Reykjavik Energy (19%) and a few smaller power companies. Landsnet, the network operator, is in the main part owned by the government (93%) after Landsvirkjun sold its 65% share at the end of 2022. Five distribution companies and municipally owned retailers are responsible for getting electricity to households and firms. The energy regulator Orkustofnun is responsible for monitoring and regulating power companies and for issuing licences for new power plants.

The market is dominated by a few large producers and consumers, with the latter mostly firms producing energy-intensive commodities like aluminium and other metals. Long-term bilateral agreements – often confidential - govern the relationship between market participants, allegedly on the grounds of heightened long-term planning security and the high capital cost of hydro and geothermal energy generation. Some large industrial electricity consumers enter direct contractual relations with producers or the network operator instead of with distributors. Overall electricity costs for industrial consumers are akin to those in several comparison countries. A subsidiary (ELMA) of the network operator Landsnet plans to set up a wholesale power exchange involving clear and transparent trading rules and a functioning price-setting mechanism by the end of 2024.

Source: (Zheng and Breitschopf, 2020[51]) and updates provided by the administration.

Regulatory reform could also help reduce inflationary pressures (see Box 1.2 on Iceland’s inflation history), thereby supporting policy in the current macroeconomic context. Companies with a dominant position in the market or less exposed to new and innovative entrants are more likely to pass cost increases to consumers (Andrews, Gal and Witheridge, 2018[52]). Stronger competition can also help keep a potential wage-price spiral under control, as containing price hikes may help reduce wage pressure. A report on the Icelandic labour market published ahead of the 2022 wage negotiations observes that competition-fostering measures in sectors such as retail sale, oil distribution, banks and insurance companies could help increase real incomes without the need for wage increases (Olafsdottir, 2022[1]). As such, the government should strongly resist the demands from certain industries that seek exemptions from the existing competition framework.

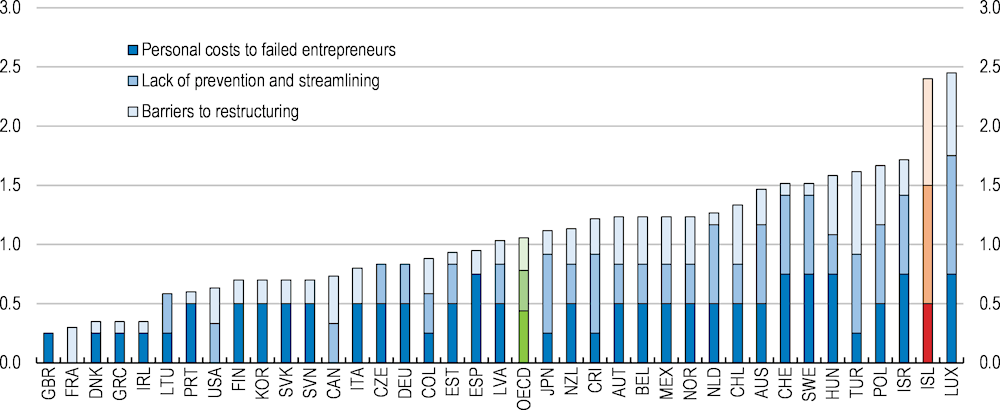

1.5.2. Temporary changes to the insolvency framework should become permanent

Efficient insolvency procedures have become more pressing as the withdrawal of covid-19-related policy support, the rise in interest rates, and growing restructuring needs induced by the green and digital transition raise pressure on businesses (André and Demmou, 2022[53]). Systems that help restructure viable firms and facilitate the exit of unviable ones can facilitate the reallocation of resources towards more productive uses and entrepreneurial risk-taking. Sound insolvency regimes can help foster technological diffusion and move the economy closer to the technological frontier. Effective insolvency frameworks encourage the parties to look for dialogue and out-of-court solutions; provide business with more options for restructuring rather than exit; speed up court procedures; improve accountability of insolvency administrators; and establish supervision rules implying more self-regulation.