After a relatively strong performance during and after the pandemic, short-term growth prospects are weak. Inflation has reached a three-decade-high, monetary policy has been tightened and the global environment is uncertain. Falling real wages and rising borrowing costs are taking a toll on household incomes, while lower housing prices reduce their wealth. Structural reforms are needed to lay the foundations for a sustained recovery. Skills are generally high, but need to be better matched to labour demand, and disadvantaged groups need to be better integrated into the labour market to bring down high long-term unemployment. A major recent reform of the employment service can help if skilfully implemented. Tax reform to incentivise work while discouraging income shifting could improve labour market outcomes and inclusiveness. Reforms in the 1990s made Sweden’s pension system with its focus on lengthening working lives and in-built sustainability the envy of countries around the world. Decisions taken before fall 2022 put these values into question in the context of population ageing and mounting spending pressures ahead.

OECD Economic Surveys: Sweden 2023

1. Key policy insights

Abstract

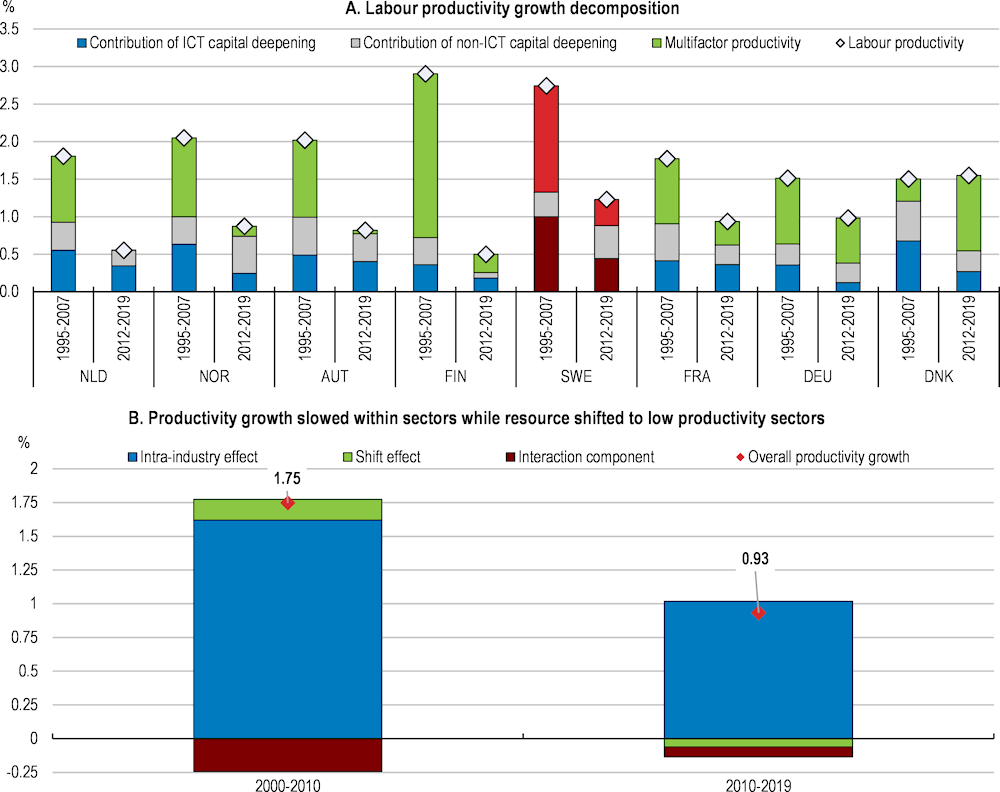

Sweden is a knowledge-based economy with high standards of living, well-being, income- and gender equality, as well as high environmental quality. Despite strong population increases, largely related to immigration, GDP per capita has expanded faster than in most OECD countries over the past decade. In the Swedish welfare model, high productivity is matched by workers’ skills, and a solid safety net supports people who lose their jobs, reach retirement age or suffer from ill health. A central pillar of this societal model is an employment rate which is among the highest in the OECD, partly reflecting high participation of women and the elderly.

After a strong recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, the economy is slowing due to the ripple effects of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. Inflation, climbing to a three-decade high, has forced the Riksbank to tighten monetary policy, further hitting highly indebted households already grappling with declining real wages. Home prices have fallen almost a fifth from their peak in March 2022, sentiment indicators point to historically depressed household confidence, and retail sales have nosedived as households rein in consumption. Commercial real estate companies, who used the years of low interest rates to gear up their portfolios, find it increasingly hard to refinance their debt as interest rates rise and financial conditions tighten. Fiscal policy, expected to be broadly neutral in 2023, has met the energy crisis by mostly broad-based, untargeted energy price support and tax reliefs, although Sweden has shown more restraint on energy price support measures than many other OECD countries. Off-cycle budget decisions have in important cases gone beyond necessary crisis management measures.

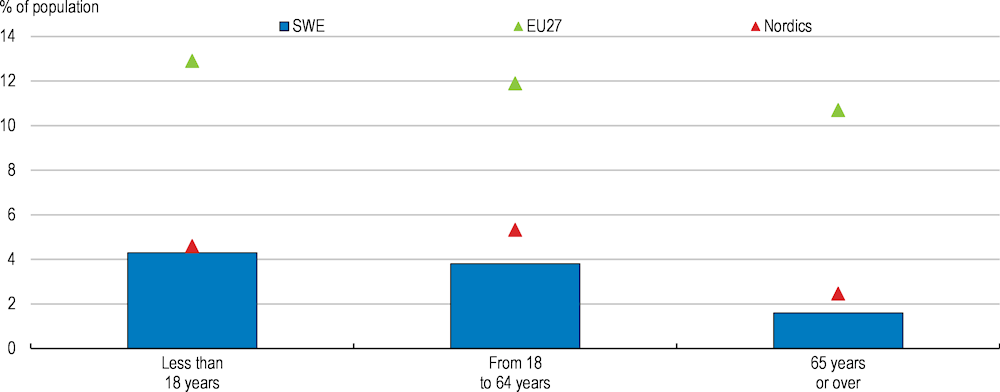

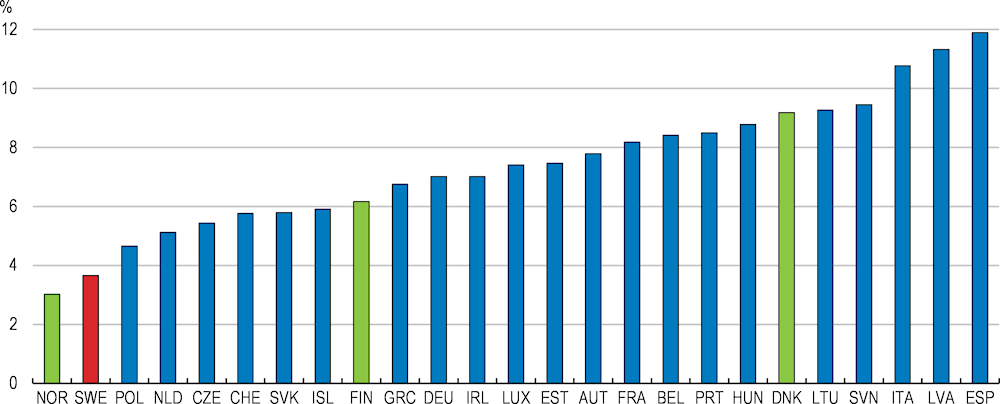

Even though Sweden has one of the highest employment rates in the OECD, population ageing increases spending pressures ahead and reduces the economic growth potential. Long-term unemployment has remained relatively high over the past decade. Despite considerable policy efforts, many of the low-skilled, the foreign-born, and the elderly find it difficult to succeed in a labour market where a compressed wage distribution places high demands on skills and productivity. Re-skilling and activation policies are key for these groups, and a recent reform introducing a purchaser-provider model with outcome-based payments for employment services could help if well implemented. The tax wedge on labour is high. The large difference between labour income tax and capital income tax incentivising income shifting, and low and regressive housing taxation, point to significant room to improve the tax mix to better support employment and inclusive growth while preserving fiscal sustainability. Sweden’s pension system has long been admired for combining high living standards for Sweden’s retirees with long-term sustainability and incentives to extend working lives. However, recent reforms go in the direction of weakening the long-term sustainability of the system and reducing incentives to remain in work for many older workers.

Sweden has led the way in reducing greenhouse gas emissions since the 1970s and has implemented a comprehensive and relatively efficient policy package with carbon pricing, subsidies, regulations and tools for cooperation and dialogue. However, the government’s intention to reduce the biofuel blending requirement will likely move the 2030 reduction target out of reach unless new and ambitious measures are implemented to make up for the shortfall. This opportunity should be seized to remove inconsistencies in greenhouse gas reduction targets and extend effective climate policies to agriculture, natural sinks and carbon capture and storage.

A green industrial revolution is taking place with its epicentre in Sweden’s northern regions. High-emitting sectors, notably steel, cement and chemicals, have set out to eliminate their emissions by means of electrification, hydrogen and carbon capture and storage, while the mining sector is expanding to provide input materials needed around the world to decarbonise. To maintain momentum, Sweden will need to roughly double its electricity generation with renewables and nuclear power and invest in plannable generation capacity, storage and transmission. These projects are challenged by long planning and permitting processes, and many wind power projects are struck down by municipalities. The green industrial revolution depends on people and skills, for industry and for complementary public services. This is a challenge for northern regions and municipalities after decades of demographic decline.

Against this background, the main messages of this Survey are:

Stand ready to tighten monetary policy as needed to curb inflation and ensure that inflation expectations are anchored. Gradually phasing out energy crisis support could help contain ongoing inflationary pressures and support efforts to meet climate targets.

Population ageing calls for mobilising underutilised labour resources, notably the low-skilled, the elderly, and the foreign-born by means of careful implementation of the employment services reform, reforms to taxes and benefits to strengthen work incentives and discourage income shifting, and by safeguarding the long-term sustainability of the pension system.

Sweden needs to urgently implement new policies to reaffirm its commitment to climate targets. The nascent green industrial revolution calls for economically viable investments in clean industry, low-carbon electricity generation and transmission to go ahead at speed.

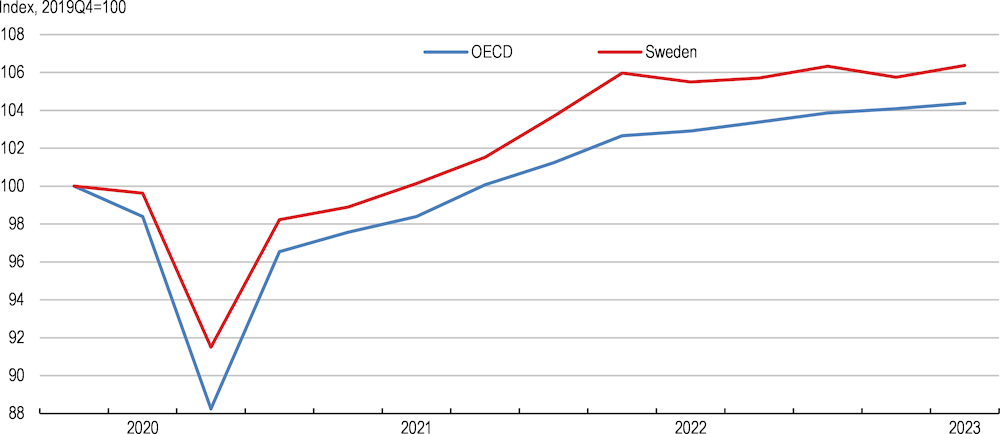

1.1. The economy is facing external headwinds

Russia’s war against Ukraine and the associated surge in energy prices put Sweden’s economy under renewed pressure from high energy costs and rising interest rates as it was still recovering from the COVID-19 crisis. Sweden fared better through the pandemic than many of its peers (Figure 1.1). After contracting by around 3% in 2020, the economy returned to its pre-pandemic level by the first quarter of 2021. The economy grew by 2.9% in 2022, but momentum waned following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Real GDP grew by 0.6% in the first quarter of 2023 after a 0.5% contraction in the fourth quarter of 2022. Household consumption and housing investments continued falling. Consumer confidence plummeted with surging inflation and interest rates, but the continued strength of the labour market prevented a larger contraction in private consumption.

Figure 1.1. Sweden’s economy was more resilient to the pandemic than the OECD average

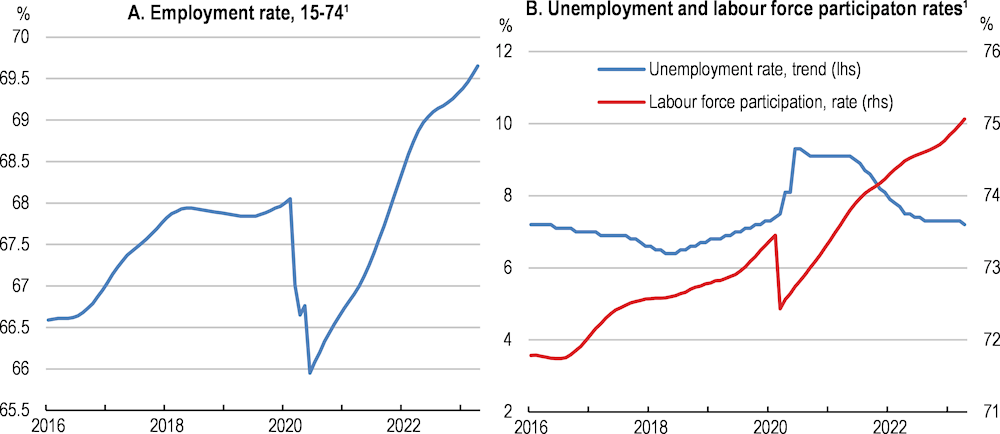

The labour market weathered the pandemic well, supported by public policies. Employment surpassed pre-crisis levels by the end of 2021 and increased at a robust pace in 2022 and the beginning of 2023 (Figure 1.3, Panel A). Unemployment was back at pre-pandemic levels by mid-2022 (Panel B). According to the latest Labour Force Survey, the employment rate reached a new high of 70% in April, and the unemployment rate dropped to 7.2%. The short-term work scheme, the largest pandemic support measure in terms of spending, was introduced promptly in March 2020 and benefitted a large number of workers until September 2021. Health measures during the pandemic, which were less intrusive in Sweden than in most OECD countries, also played a role in shielding the labour market from the worst consequences of the pandemic (Box 1.1). Sweden showed the lowest increase in unemployment and furloughs among Scandinavian countries during the first six months of the pandemic (Zoutman et al., 2020).

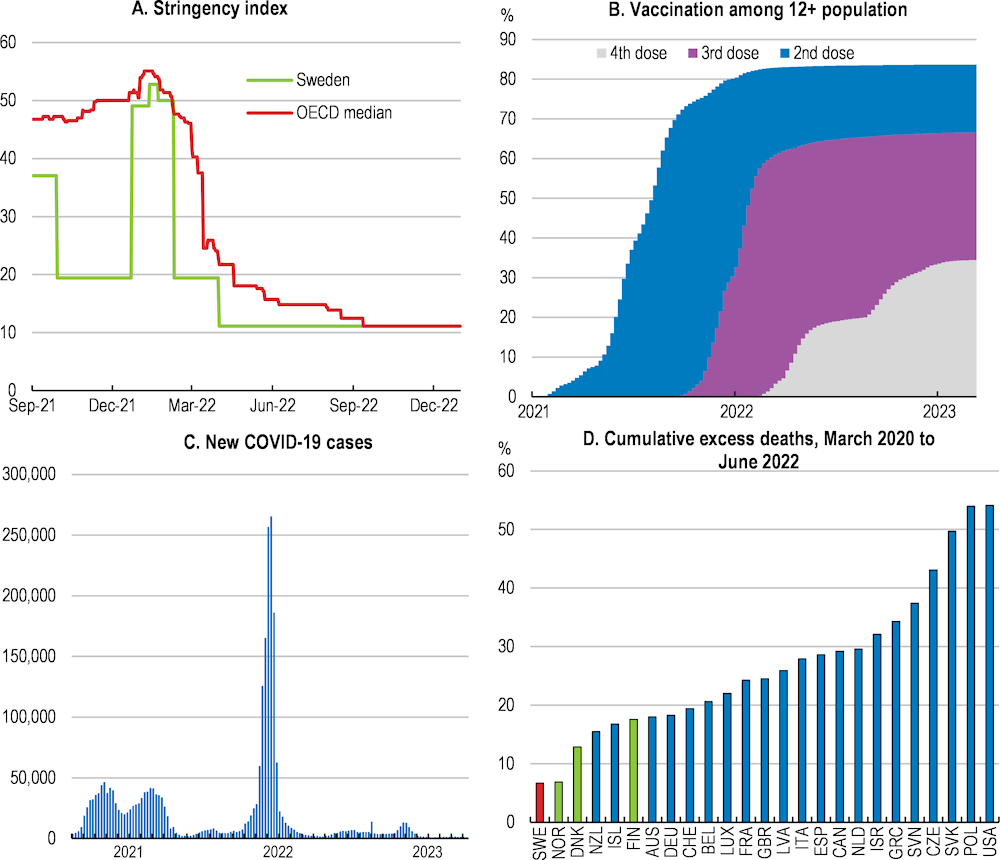

Box 1.1. Health policies in Sweden during the COVID-19 pandemic

Sweden’s health policies and responses to COVID-19 during the pandemic stand out as one of the least intrusive in the OECD. Unlike most other OECD countries, Sweden did not impose a national lockdown and relied on public recommendations or voluntary measures. Swedes were only encouraged to work from home and limit travel whenever possible, and those with symptoms of COVID-19 were asked to self-isolate. Preschools and compulsory (primary and lower secondary) schools remained open. As the number of confirmed cases surged in 2021, some restrictions were imposed, such as a ban on visiting nursing homes, but restaurants and businesses were never mandated to completely close. Although Sweden's reported COVID-19 mortality rate was among the highest in the world at the beginning of the pandemic, surpassing those of neighbouring countries in lockdown, its total excess deaths during the first two years of the pandemic were among the lowest in Europe.

Figure 1.2. Excess deaths were among the lowest in the OECD

Source: Public Health Agency of Sweden; Oxford Coronavirus government response tracker; OurWorldinData; and OECD calculations.

Source: KFF (2021) and SOU (2022a).

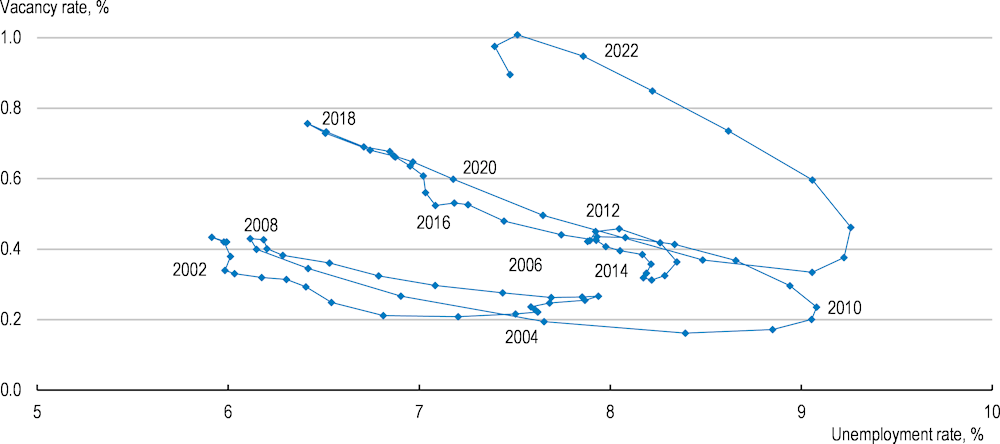

Figure 1.3. The labour market has recovered

Direct trade and financial links with Russia and Ukraine are limited, but Russia’s war against Ukraine is affecting the Swedish economy through higher energy and food prices and slow growth among important trading partners. Inflation started rising from mid-2021 because of soaring energy prices and pandemic-induced supply bottlenecks, and shot up further following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Rising electricity prices were most of the time confined to the southern areas of the country, where increasing electricity market integration means that prices much of the time are set in tune with Central Europe. The government has responded by introducing a number of support policies, including electricity price compensation to households and businesses, and most recently retroactive support to households financed by transmission bottleneck fees collected by Svenska Kraftnät, the transmission system operator. More targeted support has also been handed out, notably by increasing the housing allowance for low-income families with children (Box 1.4).

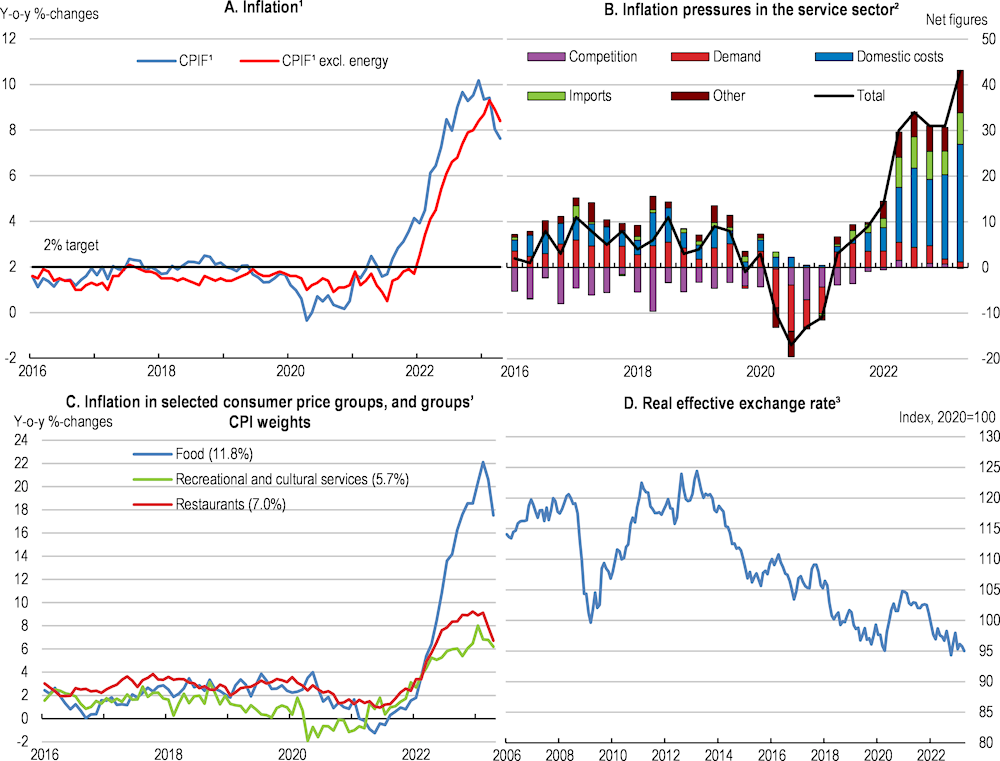

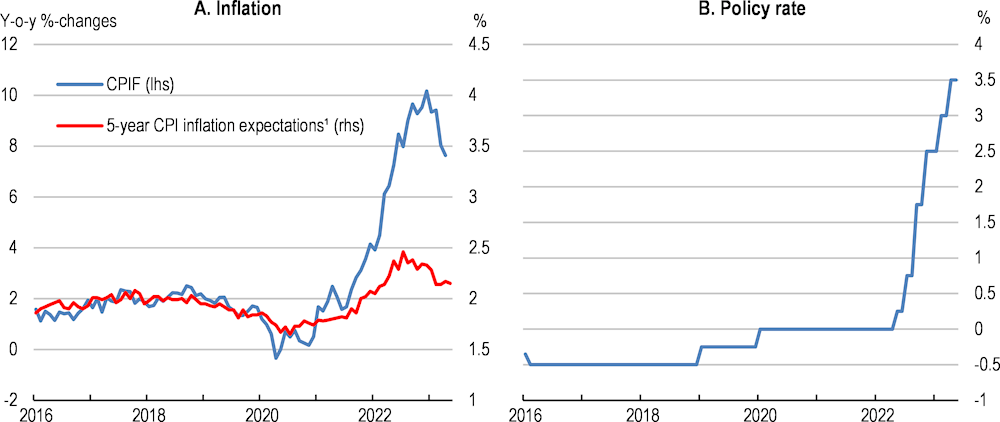

Consumer price inflation with a fixed mortgage rate (CPIF) moderated to 7.6% in April 2023, after peaking at 10.2% in December (Figure 1.4, Panel A). However, this is still around four times the 2% inflation target, and CPIF inflation excluding energy stood at 8.4%. Inflationary pressures remain broad-based, with prices rising markedly for food, restaurants, and recreation and culture (Panel C). Cost developments in the service sector are now primarily driven by domestic costs (Panel B). Nominal wages grew by around 3% in 2022, while real wages were down 5.2% year on year in March. The contribution of import prices to service inflation has also risen sharply, reflecting soaring global energy and food prices combined with the trade-weighted exchange rate which weakened over the course of 2021-22 (Panel D). Long-term inflation expectations remain slightly above the 2% target (see Section 1.3).

Figure 1.4. Inflation pressures have broadened

1. Consumer price index with a fixed mortgage rate.

2. This measure is calculated as the share of respondents in the NIER Economic Tendency Survey that raised prices times the share of respondents who mentioned X as the most important factor behind the price hike minus the share of respondents that lowered prices times the share that mentioned X as the most important factor behind the lowered price.

3. Trade-weighted average of 15 bilateral real exchange rates (including the Euro zone as a single entity).

Source: National Institute of Economic Research; Bank for International Settlements.

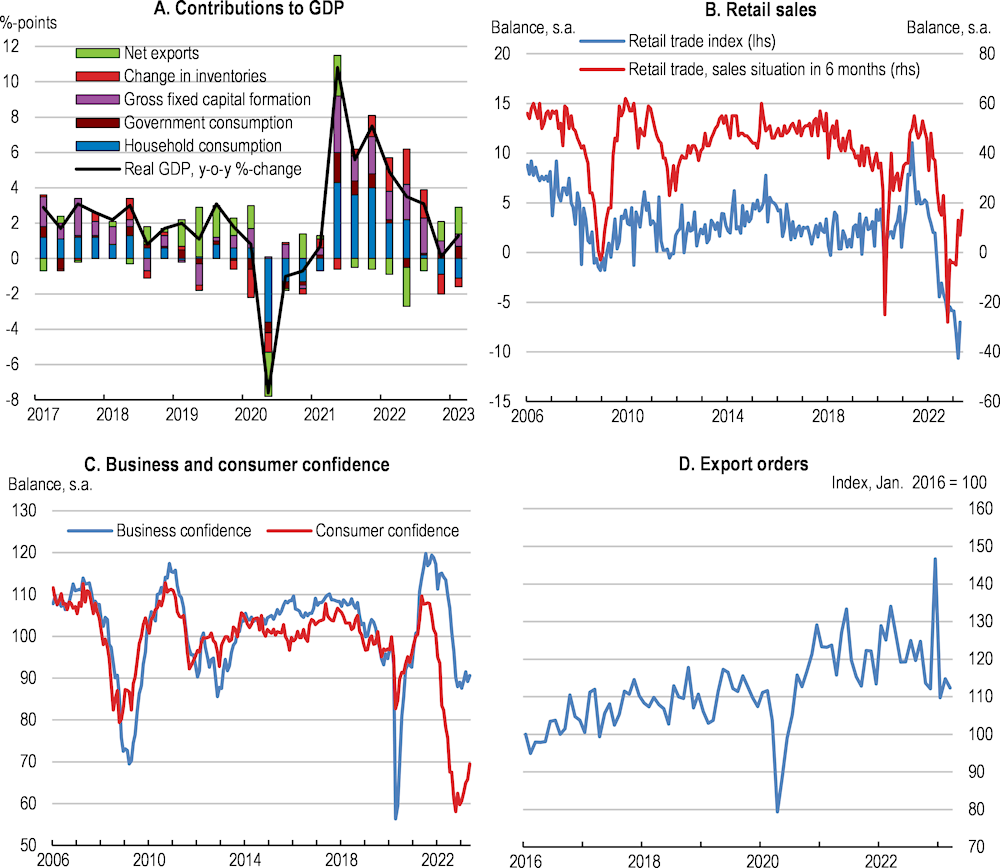

Weak household consumption is weighing on growth (Figure 1.5, Panel A). After the contraction in the fourth quarter of 2022, the economy rebounded by 0.6% in the first quarter of 2023, mainly driven by exports and inventories. However, household consumption and residential investments continued to decline. House prices have fallen considerably, reducing household wealth and investment. Consumption of durables such as clothes and household equipment has decreased sharply, in line with plummeting retail sales (Panel B). Household confidence improved slightly in recent months, partly reflecting lower electricity prices, but remained at historically depressed levels, influenced by negative real wage growth, increased debt servicing burdens, and the reduction in household wealth (Panel C). Manufacturing output has held up, with considerable order backlogs, but new orders, notably for exports, are decreasing (Panel D). Business confidence has fallen, driven by labour shortages and shrinking order books.

Figure 1.5. The economic momentum is weak

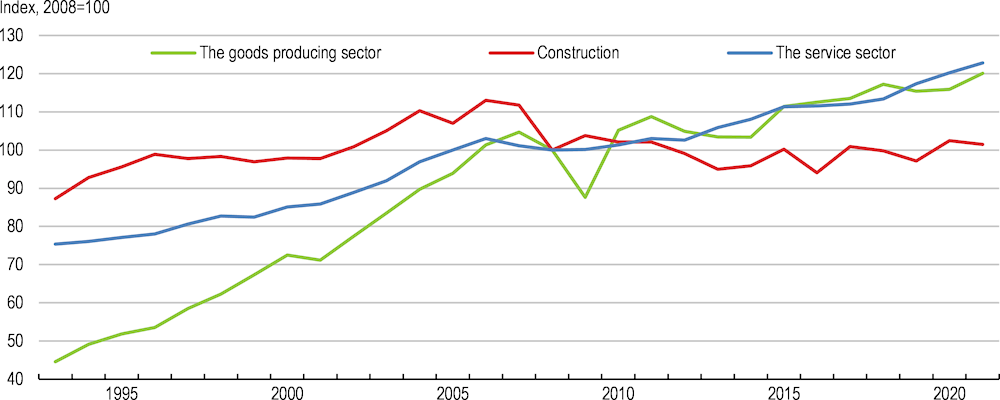

The economy is set to contract in the near term. After a 2.9% expansion in 2022, output is projected to shrink by 0.3% in 2023 before growing by 1.4% in 2024. Construction activity is set to decline significantly, against the backdrop of higher construction costs and lower housing prices. Price pressures are broadening. Inflation will therefore come down only gradually and will remain high in 2023. Nominal wage growth is set to increase given the recent wage negotiations for the manufacturing industry that concluded in April 2023, but only modestly. The agreement on 7.4% wage growth over the next two years (4.1 % in 2023 and 3.3% in 2024) sets the wage norm for other sectors to follow. As a consequence, real wages will decline in 2023 and weigh on consumption together with lower housing prices and higher debt-servicing burdens (Table 1.1).

Uncertainty remains high. A long period of very low interest rates has boosted household debt, which amounted to around 200% of household disposable income in 2022. This debt burden could reduce consumption further if mortgage rates rise faster than assumed, given the high prevalence of variable-rate mortgages (see Section 1.2). Highly-leveraged commercial real estate developers may also face severe financial difficulties as interest rates rise, with potential repercussions on financial stability (see Section 1.2). On the upside, lower-than-expected inflation could limit the decline in real disposable incomes and limit the need for further monetary tightening, boosting housing prices, private consumption and investment.

Table 1.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage changes unless specified¹, volume (2009/10 prices)

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

-2.3 |

5.9 |

2.9 |

-0.3 |

1.4 |

|

Private consumption |

-3.2 |

6.2 |

2.0 |

-2.7 |

2.0 |

|

Government consumption |

-2.0 |

2.9 |

0.1 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

1.6 |

6.8 |

6.2 |

-1.6 |

0.1 |

|

Housing |

1.6 |

11.5 |

4.7 |

-18.4 |

-4.7 |

|

Business |

1.4 |

7.6 |

8.7 |

2.1 |

1.3 |

|

Government |

2.0 |

-1.0 |

-1.2 |

4.1 |

0.3 |

|

Final domestic demand |

-1.7 |

5.4 |

2.6 |

-1.4 |

1.3 |

|

Stockbuilding² |

-0.7 |

0.4 |

1.1 |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

-2.4 |

5.9 |

3.7 |

-1.6 |

1.2 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

-5.9 |

10.8 |

7.1 |

4.0 |

3.3 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

-6.3 |

11.3 |

9.4 |

1.6 |

3.2 |

|

Net exports |

0.0 |

0.3 |

-0.6 |

1.3 |

0.2 |

|

Other indicators |

|||||

|

Potential GDP |

1.9 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

|

Output gap³ |

-3.5 |

0.5 |

1.6 |

-0.5 |

-0.9 |

|

Employment |

-1.3 |

0.9 |

2.8 |

0.1 |

0.7 |

|

Unemployment rate⁴ |

8.5 |

8.8 |

7.5 |

7.9 |

8.0 |

|

GDP deflator |

2.0 |

2.6 |

5.6 |

6.1 |

2.5 |

|

CPI |

0.5 |

2.2 |

8.4 |

7.9 |

2.4 |

|

CPIF⁵ |

0.5 |

2.4 |

7.7 |

6.3 |

2.4 |

|

Household saving ratio, net⁶ |

17.0 |

15.5 |

13.9 |

13.8 |

13.6 |

|

Current account balance⁷ |

5.9 |

6.5 |

4.2 |

5.6 |

5.6 |

|

General government fiscal balance⁷ |

-2.8 |

0.0 |

0.7 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

|

Underlying government net lending³ |

-0.4 |

-0.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

|

Underlying government primary balance³ |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

0.1 |

|

Gross government debt (Maastricht)⁷ |

39.9 |

36.5 |

32.8 |

32.7 |

32.7 |

|

General government net debt⁷ |

-38.3 |

-42.1 |

-36.5 |

-34.0 |

-32.1 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

0.1 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

3.8 |

4.1 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

0.0 |

0.3 |

1.5 |

2.8 |

3.2 |

1. Annual data are derived from quarterly seasonally and working-day adjusted figures.

2. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

3. As a percentage of potential GDP.

4. As a percentage of the labour force.

5. CPI with a fixed mortgage interest rate.

6. As a percentage of household disposable income.

7. As a percentage of GDP.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook No. 113.

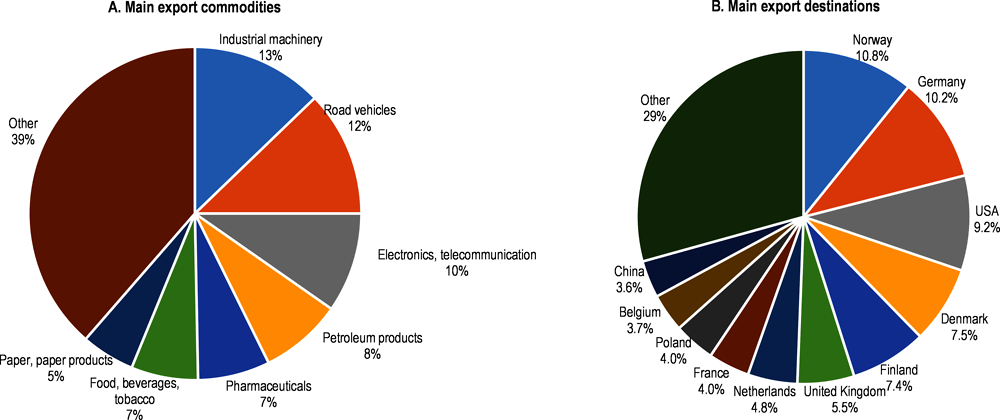

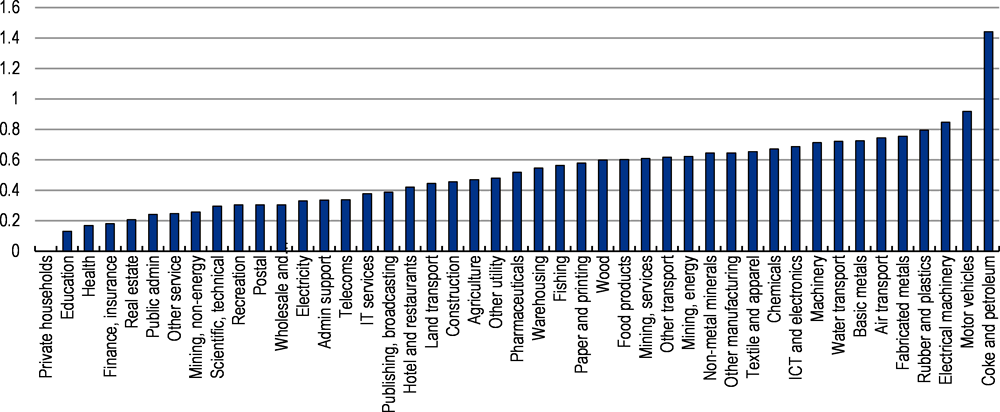

Sweden’s economy is trade-oriented, but exports are relatively diversified in terms of products and destinations (Figure 1.6). However, its deep integration in global value chains implies some vulnerabilities if global trade tensions intensify or supply chains are hit by other shocks (Schwellnus et al, 2023). The country is particularly vulnerable to supply-side shocks in some raw materials including basic metals (Figure 1.7). The raw material supply chain is essential for the green transition in Sweden and elsewhere, and like the rest of the world, Sweden currently depends on a few countries for the import of rare earths necessary to electrification and battery production. The recent discovery in northern Sweden of the largest rare earth deposit in Europe should in due course reduce heavy reliance on China, also for Sweden’s trading partners (Chapter 2). Diversification, stockpiling, early warning systems and homeshoring have roles to play to ensure the supply of essential commodities, intermediates and goods (Box 1.2).

Figure 1.6. Exports of goods by commodity and market

Share of total exports, 2022

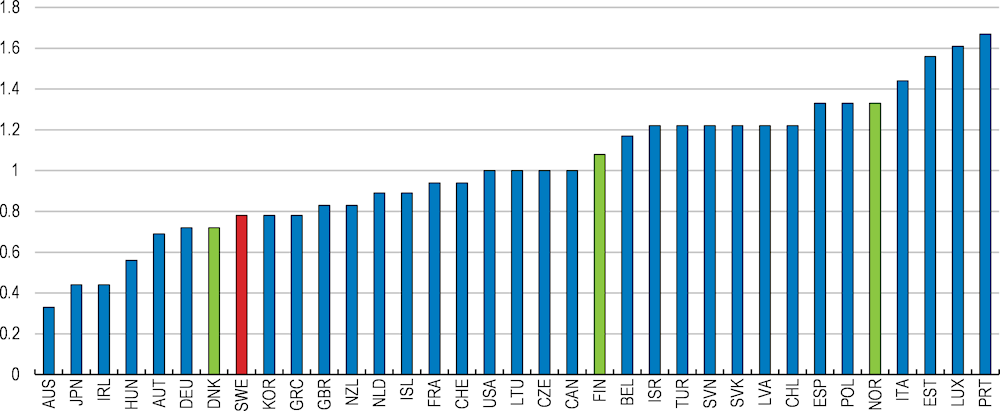

Figure 1.7. Foreign input reliance by sector

The ratio of foreign output used in domestic production to total domestic gross output

Note: The figure accounts for indirect input trade between partner countries based on the OECD Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) data. The indicator can take values above 1, given that the numerator counts value added multiple times when goods or services cross borders multiple times. The indicator is calculated as where subscripts c and j denote, respectively, countries and industries; denotes gross output of industry j’ in country c’ used in the production of industry j in country c.

Source : Schwellnus et al. (2023).

Box 1.2. Strategies for raw material supply chain resilience

At the outset, businesses should be expected to adapt to uncertainty and supply chain shocks such as COVID-19, protectionist measures and Russia’s aggression against Ukraine without policy intervention. For some essential goods there may nonetheless be a case for government intervention and coordination. Measures to be considered include:

Ex-ante assessment of risks and stress-testing: Governments can introduce a systematic risk assessment framework based on evidence and data. For instance, the Productivity Commission in Australia has developed a ‘data-with-experts’ framework to identify vulnerable supply chains. It casts a wide net by first identifying those products that are vulnerable to supply chain disruptions using a data scan, to reduce the probability of missing a good or service that is vulnerable. Then it identifies which of these vulnerable products are used in essential industries. The final step relies on expert assessment to stress test the data-driven analysis and to determine, from among the vulnerable products used in essential industries, those which are critical. Korea is also selecting core products to be monitored by the early warning system, based on data such as annual import volume and supplier concentration and strategic importance to the economy. A holistic approach would also be important, given that risks are interconnected across sectors. The Swiss Federal Office for National Economic Supply for instance uses cross-departmental analysis when conducting risk assessments.

Trade diversification: The government can contribute to trade diversification by mapping vulnerabilities and making this data available to companies, and by more direct support such as using diversification as a criterium when extending export guarantees and other financial assistance to companies trading abroad. For example, Japan provides targeted subsidies to companies which invest in facilities in ASEAN countries for their strategically important industries.

Stockpiling: Stockpiling comes at a cost, and companies may not internalise the societal costs of shortages. In these cases, governments can facilitate stockpiling of essential goods. In Switzerland, for instance, the importers of designated products, including oil products, are mandated to stock a certain amount by law. This stockpile is privately owned but can only be accessed under government permission in an emergency. In return, the storage costs of companies are financed by state taxes. Likewise, Korea has first drawing rights to oil and gas stored in Korea by foreign oil companies under the International Joint Stockpile programme in case of supply disruptions.

Home-shoring: Producing at home is expensive as a general strategy, but can be a rational policy if due consideration is given to trade-offs, including opportunity costs of public funds, and possible costs of introducing other distortions into markets. For example, half of the krypton gas used in Korea’s semiconductor production came from Ukraine and Russia before the war. The impact has been limited thanks to a combination of raw materials stockpiling, import diversification and the establishment of domestic production.

Source: OECD (2022), Australian Productivity Commission (2021); Korean Ministry of Finance and Economy (2022); JETRO (2022); Swiss Federal Office for National Economic Supply (2021).

Table 1.2. Events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Uncertainty |

Possible outcomes |

|---|---|

|

Intensification of global energy supply disruptions. |

Inflation could stay higher for longer, negatively affecting real household income and activities in energy-intensive sectors. |

|

Intensification of global trade tensions. |

Export growth could weaken and supply chain stress intensify. |

|

Sabotage of critical infrastructure, including sub-sea cables. |

The economy could be adversely impacted, for instance by lower labour productivity and interruptions to business and social functions. |

|

Stronger than expected decline in real estate prices. |

Private consumption could fall short of current forecasts. The commercial real estate sector could face severe debt refinancing problems, which could threaten overall financial stability. |

1.2. Financial stability risks should be monitored closely

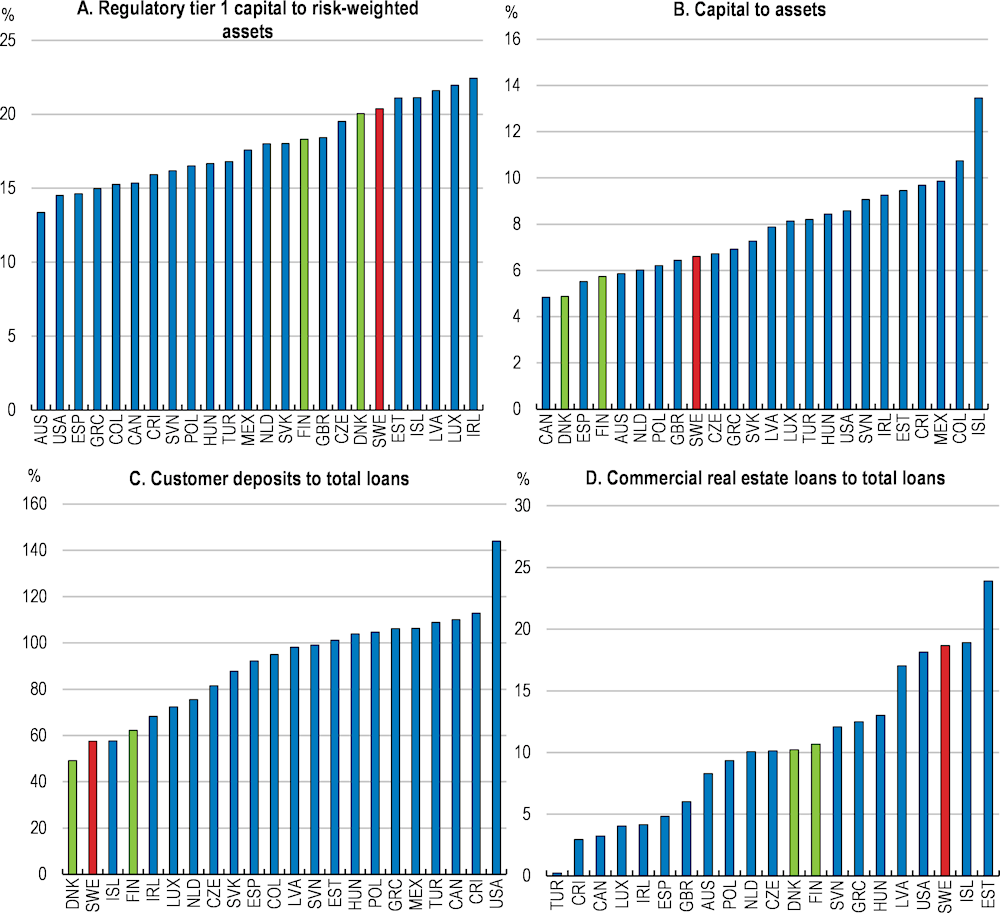

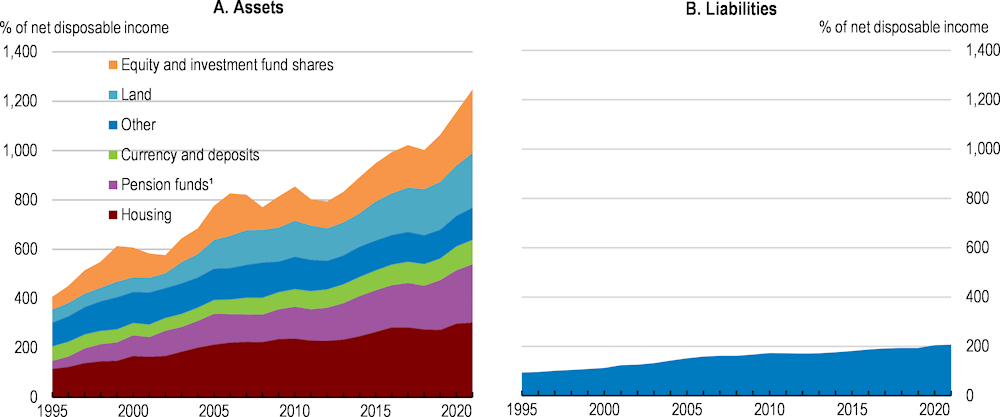

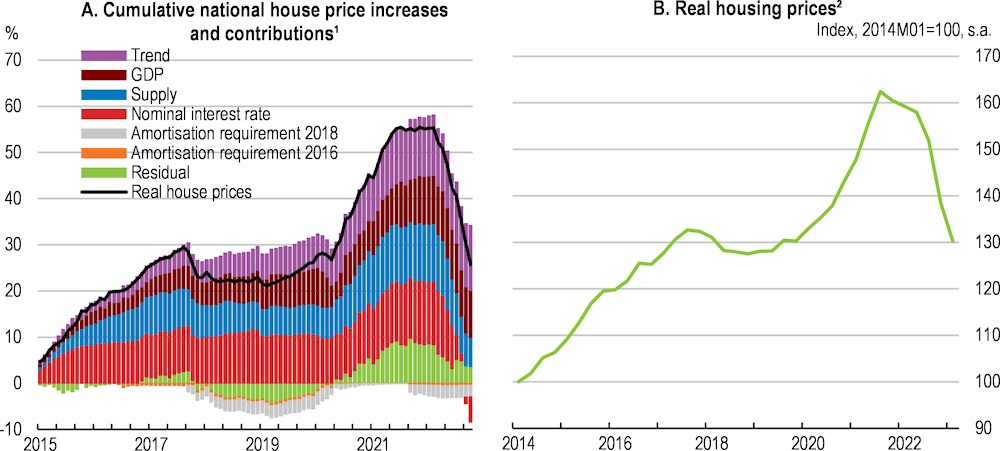

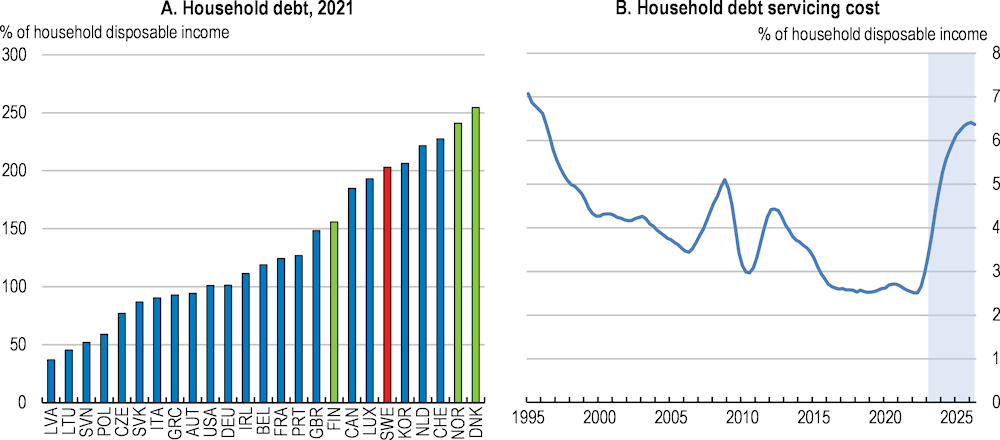

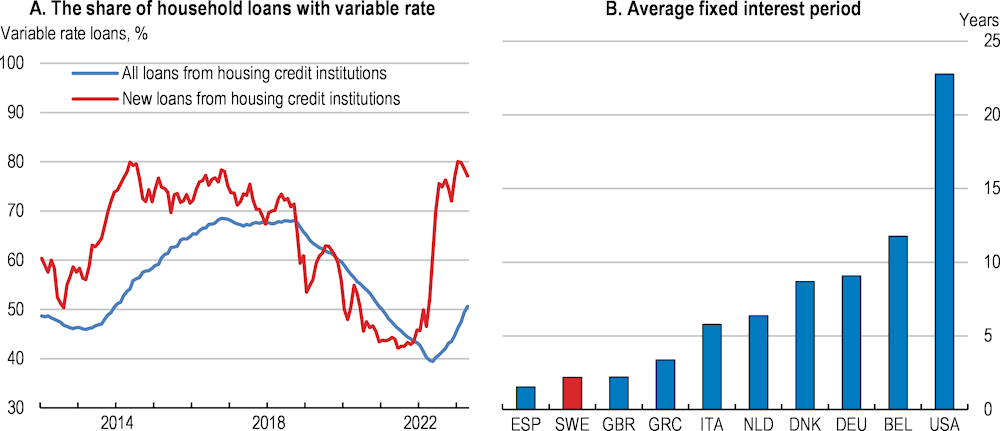

Swedish banks have high risk-weighted capital ratios as mortgages with relatively low risk weights account for a large share of their loan portfolio (Figure 1.8, Panel A), but their overall leverage is higher than in many OECD peers (Panel B). The Nordic banks have a narrow deposit base (Panel C) and rely heavily on wholesale funding, which can entail liquidity risks in periods of market turmoil. Sweden’s financial system coped well with the pandemic, backed by temporary measures by the authorities including loans, guarantees and tax holidays. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has increased uncertainty and financial conditions have tightened. Consequently, the risk of business failures and repayment difficulties for indebted households has increased. Highly indebted households and a high prevalence of variable mortgage rates make the Swedish housing market sensitive to rising interest rates. Real housing prices increased sharply during the pandemic (Figure 1.9). A number of factors are estimated to have contributed, including the easing of financial conditions, a temporary lifting of the amortisation requirement for borrowers who applied for an exemption, and a shift in demand towards larger apartments and houses outside of the city centres on the back of the expansion of teleworking (André and Chalaux, 2023). This in turn increased the average loan-to-income ratio (Finansinspektionen, 2022a; Riksbank, 2022a). Sweden’s households have high debt in international comparison (Figure 1.10, Panel A). Around 80% of the household debt consists of mortgages, and most mortgages are on short-term fixed or floating rates (Figure 1.11, Panels A and B). The share of new loans at variable rates has increased significantly recently, possibly because borrowers expect rates to fall again and therefore do not want to lock in higher rates. Households’ debt service is set to increase relatively rapidly as interest rates rise (Figure 1.10, Panel B). Households generally have sizeable asset holdings and hence good repayment abilities, even though a sizeable share of assets relates to illiquid real-estate holdings and pensions and the distribution may be uneven (Figure 1.12). However, housing market corrections, together with rising interest rates, lead over-leveraged households to hold back non-essential consumption. Swedish home prices have fallen around 19% from their March 2022 peak, one of the steepest falls in the OECD, amid tightened financial conditions, and are likely to fall further this year.

Figure 1.8. The banking system is relatively well-capitalised

2022

Macroprudential instruments can limit the build-up of financial vulnerabilities. Several steps were taken before the pandemic, including raising the countercyclical buffer from 2 to 2.5% in 2019 and tightening the amortisation requirement in 2018 (OECD, 2021a). After the COVID-19 outbreak, the countercyclical buffer was set to zero and lenders were allowed to provide a temporary exemption of the amortisation requirement. To slow the rapid rise in housing prices and household debt, the exemption to the mortgage amortisation requirement was not prolonged after August 2021. The countercyclical buffer rate is currently 1% and will reach 2% in June 2023.

Figure 1.9. Real housing prices have fallen sharply

1. “Trend” mainly reflects an upward trend. It also includes a small discrepancy between the sum of the contributions calculated through dynamic simulations and the fitted value. “Nominal interest rate” corresponds to the nominal floating mortgage rate. “Amortisation requirement 2016/2018” accounts for the mortgage amortisation requirements introduced in June 2016 and March 2018.

2. Real estate price index for one- or two-dwelling buildings. The index has been deflated with the CPI.

Source: André and Chalaux (2023); Statistics Sweden.

Figure 1.10. Household debt is high

Note: In panel A, households include non-profit institutions serving households. The shaded area in Panel B represents the Riksbank’s forecast on household debt servicing costs.

Source: OECD, National Accounts (database); The Riksbank’s Monetary Policy Report, April 2023.

Figure 1.11. Sweden has a relatively high share of variable-rate mortgages

Note: Panel A refers to loans with an original interest rate fixation period of less than three months. Panel B refers to averages over all loans from MFI to households for the period 2003-2013.

Source: Statistics Sweden; The Riksbank’s Monetary Policy Report, September 2022.

Figure 1.12. Households’ asset holdings are sizeable compared to liabilities

Further macroprudential measures may be required as housing prices bottom out and start increasing again in the future. These could include introducing a targeted sectoral countercyclical buffer which imposes a capital buffer specifically for household loans, complementing the existing countercyclical buffer, if EU law allows. The experience of Switzerland suggests that a sectoral countercyclical buffer in the household sector can contribute to lowering banks’ mortgage risks and related financial risks (Suh, 2021). It could also help counteract current biases towards financing against housing as collateral. Introducing an interest rate stress test based on payments as a proportion of income for customers seeking variable rate mortgages could also be considered (IMF, 2023a). This identifies at-risk customers and allows banks to adjust lending practices for more stable loans and mitigating default risk. However, reforming structural weaknesses in housing and tax policy to address the fundamental problems behind high housing prices and household debt is preferable to tighter macroprudential measures. Such reform could include streamlining land-use planning and zoning regulations to increase housing supply, limiting the tax bias in favour of homeownership (OECD, 2021a), and easing rental market regulations to foster a more balanced tenure mix (see Section 1.5).

To better comprehend the risks faced by households and to improve policy evaluations, it would be beneficial to have detailed microdata on household balance sheets. Granular data would provide a clearer picture of household financial situations and potential vulnerabilities, which would inform more targeted policy interventions. Moreover, this data could assist in identifying trends and patterns in household finances, allowing policymakers to better anticipate emerging financial stability risks. Unfortunately, such data has not been available since the discontinuation of the wealth tax in 2007. However, a recent public inquiry has suggested collecting more comprehensive data on household balance sheets, which could be a crucial step towards more informed and effective policy decisions (SOU, 2022b).

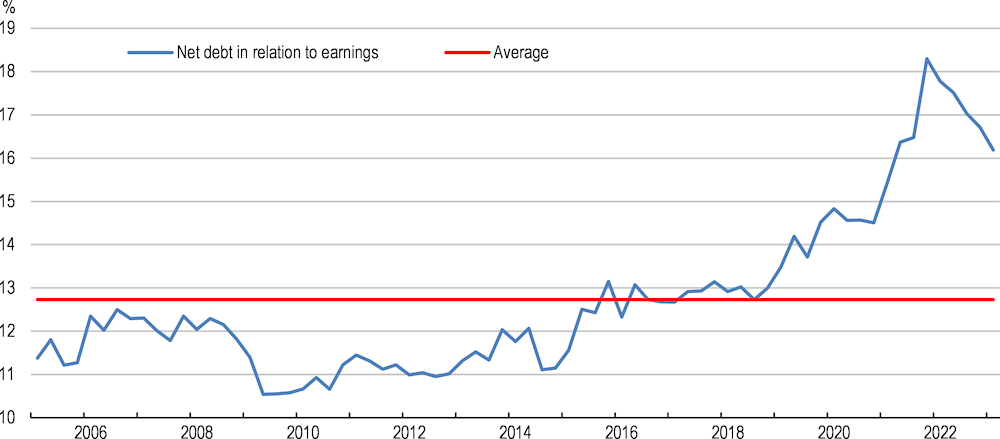

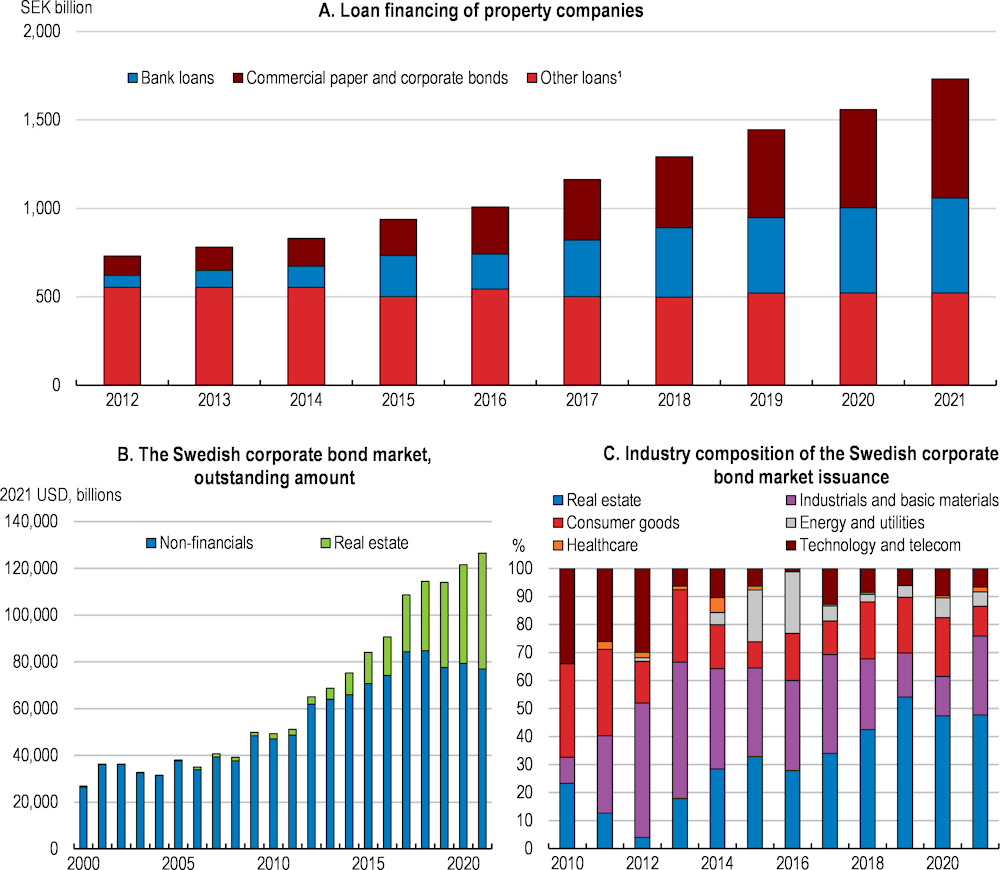

Highly leveraged commercial real estate developers pose another financial vulnerability. Real estate companies saw a sharp increase in debt relative to earnings during the pandemic (Figure 1.13). Commercial real estate loans amount to around 18% of total bank loans, one of the highest in the OECD. Real estate companies have also borrowed directly through capital markets (Figure 1.14, Panel A). Low interest rates led investors to consider corporate bonds as an increasingly attractive investment option, as many other interest-bearing assets produced very low returns (Riksbank, 2021). In 2021, the real estate sector accounted for around 40% of outstanding amounts in the Swedish bond market (Panel B) and roughly half of total issuance (Panel C), although this share is currently declining with limited activity by commercial real estate companies since the summer of 2022. This degree of concentration exposes the bond market as a whole to fluctuations within the real estate sector (OECD, 2022j). The recent downward adjustments to real estate valuations have inflated loan-to-value ratios. Refinancing options are running out and several highly indebted commercial real estate firms are now striving to reduce their debt (Finansinspektionen, 2022a). Given their high indebtedness and their large share of outstanding bonds, a shock originating in commercial real estate can spread across the financial sector more quickly than before, threatening overall financial stability. Office vacancy rates in Greater Stockholm roughly doubled from early 2020 to mid-2022, and has continued to increase, especially in less central locations (NPN, 2022; and Cushman and Wakefield, 2023).

The Swedish corporate bond market lacks liquidity, primarily reflecting low pricing transparency and a relatively high share of unrated bonds. This reduces investor confidence, contributing to lower traded volumes (Riksbank, 2022a). The Swedish corporate bond market’s structural vulnerabilities are compounded by the homogenous investor base. Pension and insurance companies dominate international markets, typically buying bonds at the issuance and holding them until maturity. In contrast, small private investment funds make up a significant portion of the Swedish market. These funds generally offer daily redemptions, which can result in large price movements if they need to sell significant quantities quickly. This situation, coupled with low transparency in traded volumes and prices, leads to unreliable price formation and liquidity.

Figure 1.13. Property companies have increased their debt relative to their earnings

Note: Volume-weighted ratio for 34 commercial real estate companies. The ratio is calculated using interest-bearing liabilities minus liquid assets relative to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation.

Source: The Riksbank.

Despite self-regulatory efforts, transparency in pricing securities remains limited, hampering the price discovery process (OECD, 2022j). Finansinspektionen required fund managers in the autumn of 2021 to conduct a thorough liquidity analysis and to take action if liquidity on the asset side did not meet specified conditions. A recent OECD report proposes further policy options to improve pricing transparency and reduce liquidity risks in Sweden (OECD, 2022j). These include increasing the proportion of corporate bonds with credit ratings through the promotion of domestic rating systems which are relatively inexpensive compared to international ones and involving more intermediaries, notably banks, who can quickly publish price data for the bonds. Finansinspektionen, the Riksbank, and the Swedish National Debt Office have also jointly called for the introduction of a Swedish standard for benchmark bonds, which requires a minimum issuance of SEK 1 billion (i.e. around USD 100 million) and at least two intermediaries (Finansinspektionen, 2022b), which would help increase transparency and liquidity in the market. Despite recent failures of several US regional banks and rising bond rates, the stability of Swedish banks and the financial system remains intact, with limited links and relatively large capital buffers (SOU, 2023). The Riksbank and Finansinspektionen should remain vigilant and be prepared to intervene if necessary to preserve financial stability in the short term.

Sweden’s fintech sector has grown rapidly over the past decade and its size is one of the largest in Europe (McKinsey, 2022). The sector is expected to expand further in the coming years, with new technological advancement and a more mature online lending market (Bertsch and Rosenvinge, 2019). The expansion of the fintech industry provides a number of benefits, notably by boosting competition and providing cheaper and easier accessible financial services. It can pose financial risks, however, because loans from fintech companies tend to be directed to high-risk borrowers who are unable to borrow from conventional financial institutions. The fintech sector remains relatively small compared to the rest of the financial system in Sweden, and therefore does not pose financial stability risks for the moment (Riksbank, 2022b). However, careful monitoring is needed given its rapid growth and the growing exposure of commercial banks to fintech credit (Bertsch and Rosenvinge, 2019). Many Fintech companies are not under the supervision of Finansinspektionen, thereby increasing the risk that financial sector vulnerabilities remain undetected (Riksbank, 2022c). Going forward, identifying and rectifying information gaps should remain a priority.

Figure 1.14. The financial sector has become increasingly exposed to property companies

1.The 2021 value is an estimate by the Riksbank.

Source: The Riksbank, Financial Stability report 2022:2; and OECD (2022), The Swedish Corporate Bond Market and Bondholder Rights.

1.3. Monetary policy has been tightened

Responding to rising inflation, the Riksbank raised its policy rate in six steps from 0% in May 2022 to 3.5% in April 2023 (Figure 1.15). These hikes, while somewhat more modest than those of other central banks, partly reflecting high interest-rate sensitivity caused by high household debt with mostly floating rates, have helped contain increases in long-term inflation expectations to only slightly above the 2% target. Wage growth is expected to be relatively modest compared to many other European countries. The wage negotiations have resulted in a two-year nominal wage increase of 7.4%.

Monetary policy should continue to ensure that inflation expectations are anchored to prevent a price-wage spiral. Even though monetary tightening has a cost in terms of reduced demand and financial market strain as discussed above, not tightening enough would further entrench high inflation, and entail far more costly subsequent tightening to re-anchor inflation expectations and restore the credibility of the Riksbank.

Besides raising interest rates, the Riksbank started normalising its balance sheet. It ended net asset purchases in 2021 and tapered asset purchases throughout the second half of 2022 before halting them completely from January 2023. The Riksbank started to sell government bonds in April 2023. It plans to hold its corporate and mortgage bonds until they reach their maturities. The maturities of these bonds are relatively short. Almost the entire holding of these bonds will mature within five years (Flodén, 2022). Such a gradual and predictable quantitative tightening approach is likely to limit how much it increases market pricing of liquidity risks and long-term interest rates (Ono and Pina, 2022).

Figure 1.15. Monetary policy has been tightened

1.Money market players’ expectation.

Source: The Riksbank; National Institute of Economic Research.

Box 1.3. Implications for the Riksbank’s long-term earnings capacity from a cashless society

After substantial purchases of mainly fixed-rate government bonds, the Riksbank is expected to face losses of around SEK 80 billion for 2022 and end up with negative equity. Losses occur as policy rate hikes lower asset values and increase interest expenses. This is also the case for other OECD central banks.

In the case of the Riksbank, the challenge is compounded by its low seigniorage (the profit made by printing money), as the country is largely cashless. The Riksbank’s earnings capacity to buffer the losses is therefore significantly lower than that of other central banks.

Negative equity may not necessarily be a concern for central banks, as they have the unique ability to finance their activities through seigniorage. Some central banks, such as in Chile, the Czech Republic, Israel and Mexico, experienced negative equity for several years, but financial and price stability were maintained. The problem arises, however, if a central bank experiences a permanent loss of seigniorage. In such a scenario, the central bank’s interest-bearing debt could rapidly increase beyond its control, ultimately jeopardising long-term price stability (Flodén, 2022). If there are no alternative ways to generate earnings, the government may need to recapitalise the central bank.

The new Riksbank law taking effect this year mandates equity injections from the state, if the Riksbank’s equity is below SEK 20 Bn (or 1/3 of the “target value”, 60 billion for 2023). The exact amount depends on accounting technicalities and a formal adoption by the Riksdag. Many OECD countries do not have a legal obligation for the government to recapitalise the central bank in case of negative equity. Only some central banks have explicit indemnity agreements with the government that allow compensation for losses related to certain quantitative easing policies (e.g., the Bank of England, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, and the Bank of Canada).

The government’s obligation to recapitalise the central bank may raise some issues, including with respect to central bank independence. Central banks are public institutions, but there is broad consensus that their independence is essential to fulfil their mandate of achieving price and financial stability without undue influence from governments with priorities that are sometimes at odds with the central bank’s objectives (Bell et al., 2023).

It is therefore crucial to establish transparent and codified arrangements for dealing with potential financial losses or reduced profitability. This can be achieved through implementing fully automated and credible rules for recapitalisation by the government, developing protocols for handling loss episodes, and establishing clear risk-sharing agreements (Bell et al., 2023). Generating earnings through alternative means could also be considered. One promising avenue is through the implementation of a central bank digital currency (CBDC). CBDCs can potentially create seigniorage, for instance by creating differences between returns on central bank assets and currency liabilities or reducing operating costs compared to cash (BIS, 2018), especially when the demand for the CDBCs is high (Riksbank, 2020). Therefore, CBDCs can be considered an important component of promoting central bank independence by providing alternative revenue streams and reducing the risks to long-term profitability in the cashless society. However, issuing CBDCs carries financial and operational risks, including bank runs, capital flow volatility, and cyber risks (IMF, 2023b).

1.4. Fiscal policy support should be gradually phased out

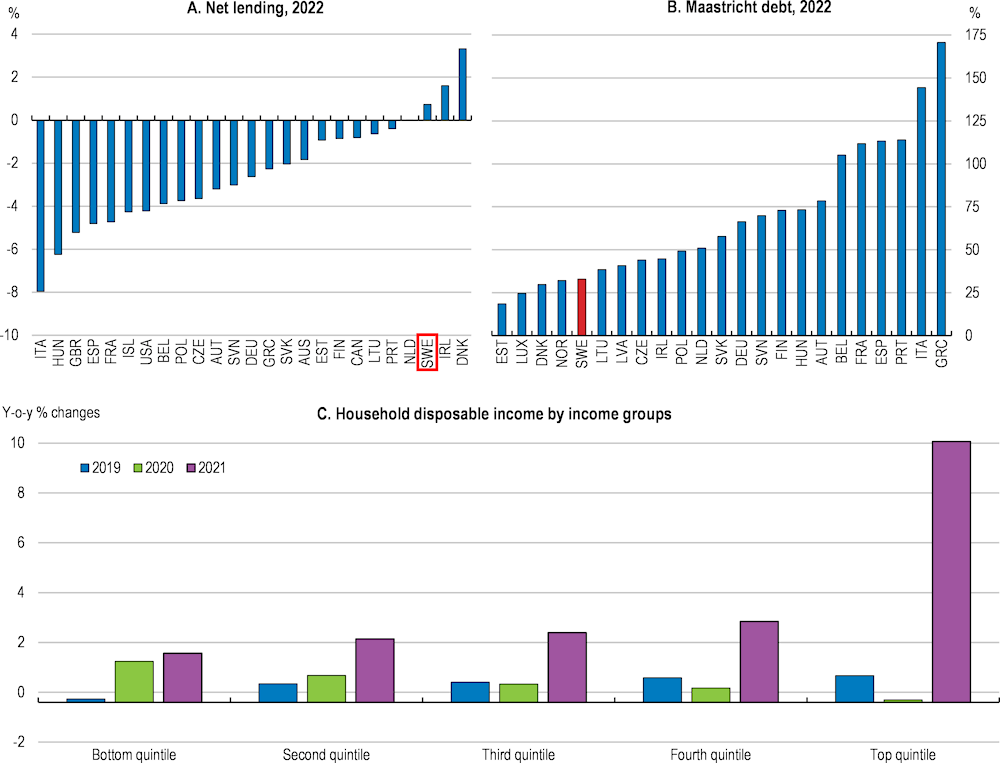

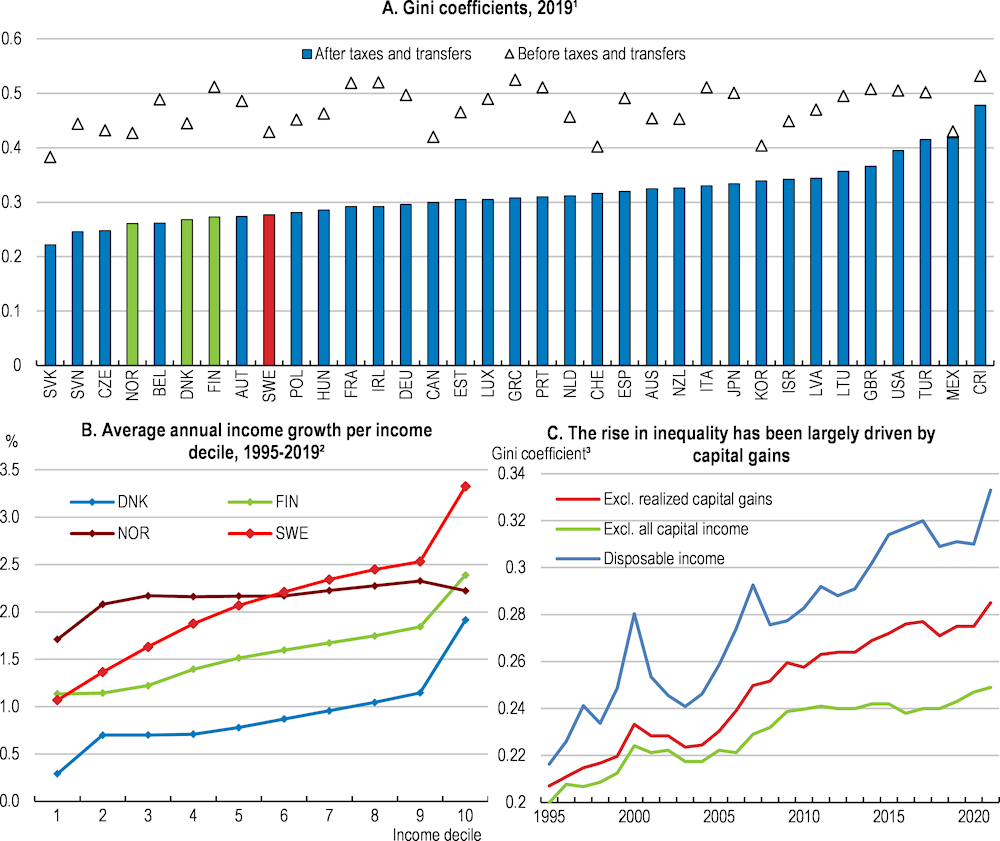

After the pandemic years of increasing public expenditure, fiscal support continued in 2022 albeit to a lesser extent than in many other OECD countries. Discretionary fiscal support during the pandemic is estimated at 4% of GDP in 2020 and 4.5% in 2021, while strong revenue growth in 2021 offset the deterioration of the underlying primary balance (Figure 1.16, Panel A), which helped keep public debt low (Panel B). Temporary employment retention subsidies and cash transfers, together with automatic stabilisers, helped save jobs and limited household income losses. Despite the pandemic, the incomes of the bottom quintile of households grew in 2020, and by more than for the other quintiles (Panel C). However, this pattern reversed in 2021 as the top quintile of households experienced strong income growth, primarily due to increased capital income.

In 2022, in response to increasing energy prices and the deteriorating energy security situation, the government added discretionary spending amounting to 1.2% of GDP to its already expansionary budget. The measures included electricity subsidies for households in southern Sweden where electricity prices are relatively high (Box 1.4). They also included tax cuts on diesel and petrol, and a temporary increase in housing allowances for economically vulnerable families with children. In addition, the measures included a permanent increase of the basic pension and earnings-related pensions (see Section 1.5).

Figure 1.16. Fiscal stimulus has supported household disposable income

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 112 Database; Statistics Sweden Statistical Database: Household finances (Income distribution (fractiles) by region, type of income, distribution measurements, observations and year, 2021).

Box 1.4. Support measures in the face of rising electricity prices

The government has responded to soaring electricity bills by introducing a number of measures aimed at both households and companies:

In the spring of 2022, the government set aside SEK 9 billion to compensate households with an energy consumption that exceeded 700 kWh per month in the period December 2021 to February 2022. The support was based on electricity consumption, ranging from SEK 100 to SEK 2000 for households consuming more than 2000 kWh in the given month. The support was then extended, and slightly modified, to include also March 2022 for households in southern Sweden (electricity bidding areas (SE) 3 and 4). Payments were administered by the Legal, Financial and Administrative Services Agency (Kammarkollegiet) and private grid operators.

In February 2023 some 4.3 million households in SE3 and SE4 received retroactive compensation for electricity consumed between October 2021 and September 2022. The support amounts to SEK 0.5 per kWh consumed for SE3 and SEK 0.79 per kWh for SE4 financed by transmission bottleneck fees collected by the Transmission System Operator Svenska Kraftnät. The government has allocated SEK 17 billion to the Swedish Social Insurance Agency, which is responsible for the payments. Companies and other organisations will be able to apply for a similar support (with total cost estimated at SEK 29 billion) until September. Some 27 000 households in southwestern Sweden connected to the European natural gas network will receive SEK 0.79 per kWh (at an estimated total cost of SEK 150 million).

Another support scheme, covering November and December 2022, was expanded to include households residing in SE1 and SE2 in northern Sweden. The households will be compensated for 80% of their electricity consumption (up until 18,000 kWh) and receive SEK 1.29, SEK 1.26 and SEK 0.9 per kWh in SE4, SE3 and SE1 and SE2 respectively. Payments started in the spring of 2023.

The government has set aside SEK 2.4 billion to support electricity-intensive companies. Businesses consuming over 0.015 kWh per SEK of turnover in the period October-December 2022 will be compensated for electricity expenditure that exceeds the 2021 average electricity price by more than 50%. The support will have a ceiling of EUR 2 million per firm.

Source: Government of Sweden (2023a); Government of Sweden (2022a); Swedish Energy Agency (2023).

The fiscal stance in 2023 is set to be broadly neutral. A fuel tax reduction and retaining the pandemic-era unemployment benefit increase weaken the budget balance. Recent electricity supports are financed by redistributing to households the extraordinarily high bottleneck fees collected by the transmission system operator Svenska Kraftnät during the energy crisis and will therefore not directly affect the fiscal balance. In response to Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and against the backdrop of Sweden’s NATO application, defence spending is also set to increase. These measures, presented in the autumn budget for 2023, amount to around 0.6% of GDP, which is set to be partly financed by structural savings. In mid-April, the government presented the spring 2023 budget bill which includes new measures of around SEK 4 billion (0.1% of GDP) focusing on defence and education. It also temporarily raises housing subsidies for the economically vulnerable. It follows three off-cycle budgets totalling SEK 2.4 billion (0.05% of GDP) related to a revenue cap for electricity producers, temporary fuel tax reductions, and military aid to Ukraine. Adding up these off-cycle budgets, measures in 2023 supplementary to the autumn budget amount to 6.4 billion (0.15% of GDP).

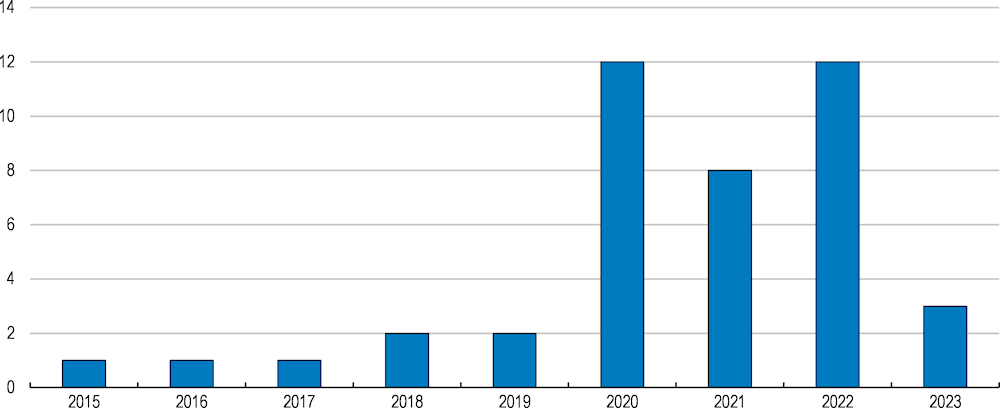

Extensive fiscal decisions have thus been made outside of the regular budget process. The budget was amended outside of the ordinary budget cycle 12 times in 2022, and eight in 2021 (Figure 1.17). Some off-cycle expenditure increases to respond to major and sudden crises such as COVID-19 and the energy crisis can be seen as a reasonable deviation from the fiscal framework. However, a number of measures have been decided outside of the ordinary budget process even when they were either unrelated to the COVID-19 crisis or Russia’s war on Ukraine, or lacking the urgency required for off-cycle treatment. Examples of expenditure which should have been handled in a regular budget process include the new tax-funded income pension supplement (see Section 1.5), increasing the bonus for low-emission vehicles (since abolished, see Chapter 2) and ex-post compensation to households for high electricity prices (Fiscal Policy Council, 2022a). Evidence suggests that the frequent off-cycle tax and spending decisions risk undermining fiscal credibility (End and Hong, 2022), and that lower fiscal credibility is strongly correlated with worse economic outcomes in the medium term, for instance through deteriorating market borrowing conditions (Hameed, 2005; Arbatli and Escolano, 2015; Kemoe and Zhan, 2018). It is important to go back to the normal budget process where different expenditures are weighed against one another in a unified review and expenditure increases are examined in light of a predetermined total fiscal space (Ministry of Finance, 2017).

The Swedish fiscal policy framework consists of budget policy targets (notably a surplus target), a disciplined central government budget process, independent monitoring by the Fiscal Policy Council and rules to secure openness and clarity. The framework, together with the Fiscal Policy Council’s ex-post evaluations, has served the country well for a long time, notably in stabilising the economy, including during the global financial crisis (Eyraud et al., 2018). To ensure that off-cycle budget spending is indeed used to respond to crises as opposed to pushing through unrelated measures without the scrutiny of the normal budget process, the Fiscal Policy Council could be encouraged to assess in real time whether or not off-budget spending is urgently warranted as a crisis response. Any new assignments to the Fiscal Policy Council should come with an evaluation of the need to increase its resources, as its staff is limited.

The government should stick to fiscal strategies that do not exacerbate ongoing price pressures, to help the central bank contain inflation and allow for smaller increases in interest rates than would otherwise be the case. The electricity subsidies cover households that paid a higher price than a certain limit, and they are not income-tested. The compensation has been retroactive and therefore not known to customers at the time of purchasing electricity, but it may increase the propensity to spend by making customers expect similar support to be repeated. Also, such generalised energy subsidies including fuel tax cuts are costly, and benefit higher-income households disproportionally (OECD, 2022a). If extended over the long term, they lead to overconsumption and run counter to climate targets. Transfers to those most in need would be a superior alternative. Targeted support has also been handed out, notably by increasing the housing allowance for low-income families with children by up to SEK 1325 per month at a total cost of SEK 500 million. The government plans to increase the housing allowance further (from 25 to 40% of the housing benefit) and push the end date of the increased allowance from 30 June to 31 December 2023, which is a step in this direction. Going forward, temporary energy supports including fuel tax cuts should be gradually phased out and the general social security system should take over in supporting households in need. This would maintain incentives to reduce energy use, while contributing to reducing inflation pressures. At the same time, the social security system should be carefully reviewed to ensure adequate support for those who rely on it, given that major working-age benefits benefits and associated ceilings have not been regularly uprated to match income growth over the past two decades (OECD, 2019), leading to fairly modest benefit levels.

Enhancing the effectiveness of the public administration can also improve the responsiveness, the quality and the cost efficiency of public services, and help the country embrace the green and digital transitions. Sweden has developed a unique public governance model, with relatively few ministries and relastively high independence of public agencies. Satisfaction with public services is high and inequality is low, with a 0.27 Gini coefficient post taxes and transfers (OECD, Forthcoming). Government is large in OECD comparison both in terms of employment (29% of total employment) and expenditures (53% of GDP in 2021) (OECD, 2021d). However, the country also faces regional and sectoral disparities in the access, quality and digitalisation of public services, and faces a number of challenges in governing cross-cutting issues, particularly the digitalisation of the public administration, public sector integrity and climate change, which call for improved coordination and policy coherence (OECD, Forthcoming).

Local government revenue is sensitive to economic cycles, primarily due to its heavy reliance on personal income taxes. This dependence, coupled with the requirement for a balanced budget every year, creates a challenge for local governments to invest in countercyclical public housing and infrastructure projects. The situation has been further exacerbated by increased spending on interest rates. Investing in housing and other infrastructure is particularly important for regions transitioning to a greener economic model, where workers may need to relocate or retrain for new jobs (Chapter 2). To bridge the investment gap, municipalities could be allowed to collect more tax revenues, particularly property taxes (see Section 1.5).

Figure 1.17. Extensive fiscal decisions have been made outside of the regular budget process

Number of extraordinary amendment budgets

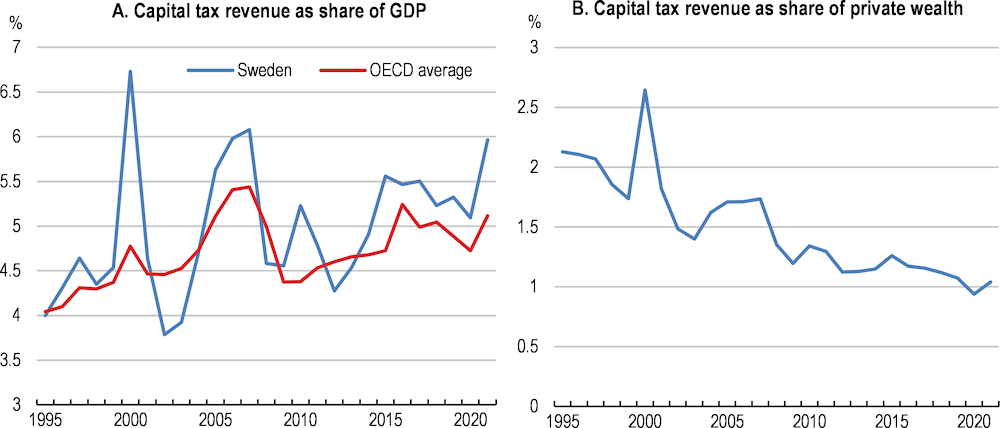

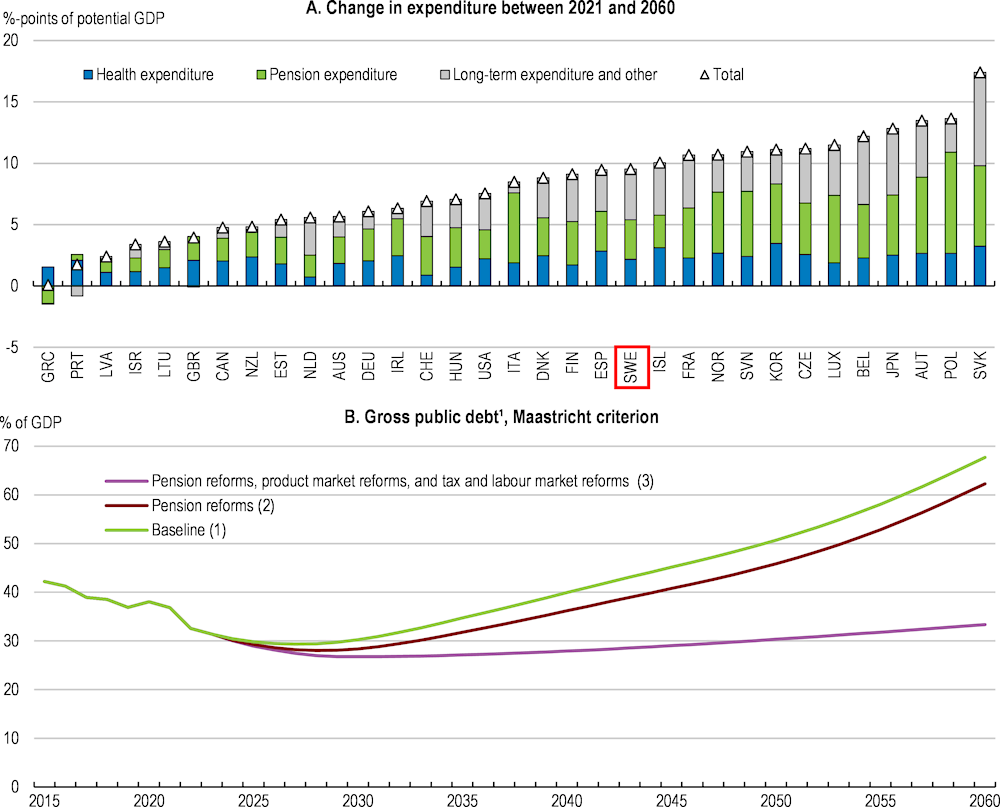

Public debt remains low in international comparison (Figure 1.16, Panel B). Despite the fiscal deficit, the public debt ratio fell in 2022 due to the Riksbank's amortisation of foreign currency loans, together with high inflation, which pushed up nominal GDP. Even so, population ageing is projected to exert relatively high spending pressures ahead, notably in health and long-term care (Figure 1.18, Panel A). According to the OECD Long-term Model, ageing-related public expenditure will increase faster than in many other OECD countries. Without measures to contain ageing-related costs, debt would rise to close to 70% of GDP by 2060. In contrast, assuming ageing costs are contained through increasing productivity and cost-efficiency in public services, such as by expanding home/community-based long-term care and telemedicine as recommended in the previous Survey (OECD, 2021a), and structural reforms implemented in line with the recommendations of this Survey, the debt-to-GDP ratio would stabilise around the current level of 35% of GDP (Panel B and Box 1.5). Increasing tax revenues particularly through higher employment or working hours, together with curbing spending through improving cost efficiency, are key to ensuring long-term fiscal sustainability.

Figure 1.18. Population ageing exerts spending pressures ahead

Note: (1) Based on no policy change and age-related costs as estimated in the OECD long-term model baseline (Guillemette et al., 2017); (2) Also implementing recommendations on pensions as outlined in the Survey (i.e. increasing the relative importance of earnings-related pensions) (3) Also phasing out mortgage interest deductibility, closing the gap in property tax revenues against the OECD average by one-third by 2030, closing the gap in the labour tax wedge against the OECD average by half by 2030, easing rental regulations, streamlining building, planning and product market regulations affecting construction and speeding up climate-friendly investment, and boosting active labour market policies. The model parameters are based on simplified assumptions standardised across OECD countries.

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Long-term model; OECD (2022b), Social spending (indicator), doi: 10.1787/7497563b-en; Guillemette and Turner (2021).

Box 1.5. Quantifying the impact of proposed structural reforms

This box provides a summary of the long-term potential impacts of selected recommendations in this Survey on GDP and the fiscal balance. However, estimating the exact impact of the recommended reforms is often challenging due to the lack of suitable theoretical or empirical models. Therefore, the quantification presented in this section is based on scenarios that capture some aspects of these reforms. It's important to note that the quantified impacts are merely illustrative and subject to large uncertainties.

|

Recommendation |

Effect on the level of GDP per capita in 2050 (percentage points) |

Net fiscal impact in 2050 (change in primary balance, % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|

|

Implement recommendations on pensions as outlined in the Survey (Increasing the relative importance of earnings-related pensions)¹. |

+0.3 |

+0.3 |

|

Implement revenue-neutral tax reform to reduce the tax wedge on work, increase property-related taxes, reduce incentives to classify labour income as capital income and expand the CO2 tax with a tax credit for negative emissions.² |

+1.8 |

0 |

|

Ease rental regulations and streamline building, planning and product market regulations affecting construction and speeding up climate-friendly investments.³ |

+7.9 |

+ 1.4 |

|

Boost active labour market policies, notably by enforcing activation requirements more strictly. 4 |

+2.4 |

+ 1.6 |

Note: 1. Increasing the relative importance of earnings-related pensions is assumed to postpone retirement by four months on average by 2050, as it encourages people to work longer. 2. The gap to the OECD average of the labour tax wedge for above-average earners is assumed to be reduced by half by 2030. The capital dividend tax rate in Sweden is assumed to be increased corresponding to one-third of the gap to the OECD average by 2030. One-third of the gap to the average OECD property tax revenues is assumed to be closed by 2030. Mortgage interest deductibility is assumed to be gradually phased out until 2030.The tax reform is assumed to be calibrated so that increased taxes from property and dividends off-set expenditures for a tax credit for negative emissions and reduced revenue from the personal income tax. 3.The strictness of rent control is assumed to move to the level of Norway, where the initial rent level can be freely negotiated and rent increases are regulated. The reform would increase rental housing supply by a more efficient use of the current housing stock and by incentivising additional investments in rental housing. The OECD Product Market Regulation indicator on barriers to investment (ranging from 1 to 6) is assumed to be reduced by 0.4. 4. Boosting active labour market policies spending by 0.5% of GDP by 2050 is assumed to lead to an increase in the employment rate by 6 percentage points by 2050.

Source: OECD simulations based on the framework by Egert and Gal (2017) and Guillemette and Turner (2020).

1.5. Structural reforms for a stronger and more inclusive labour market

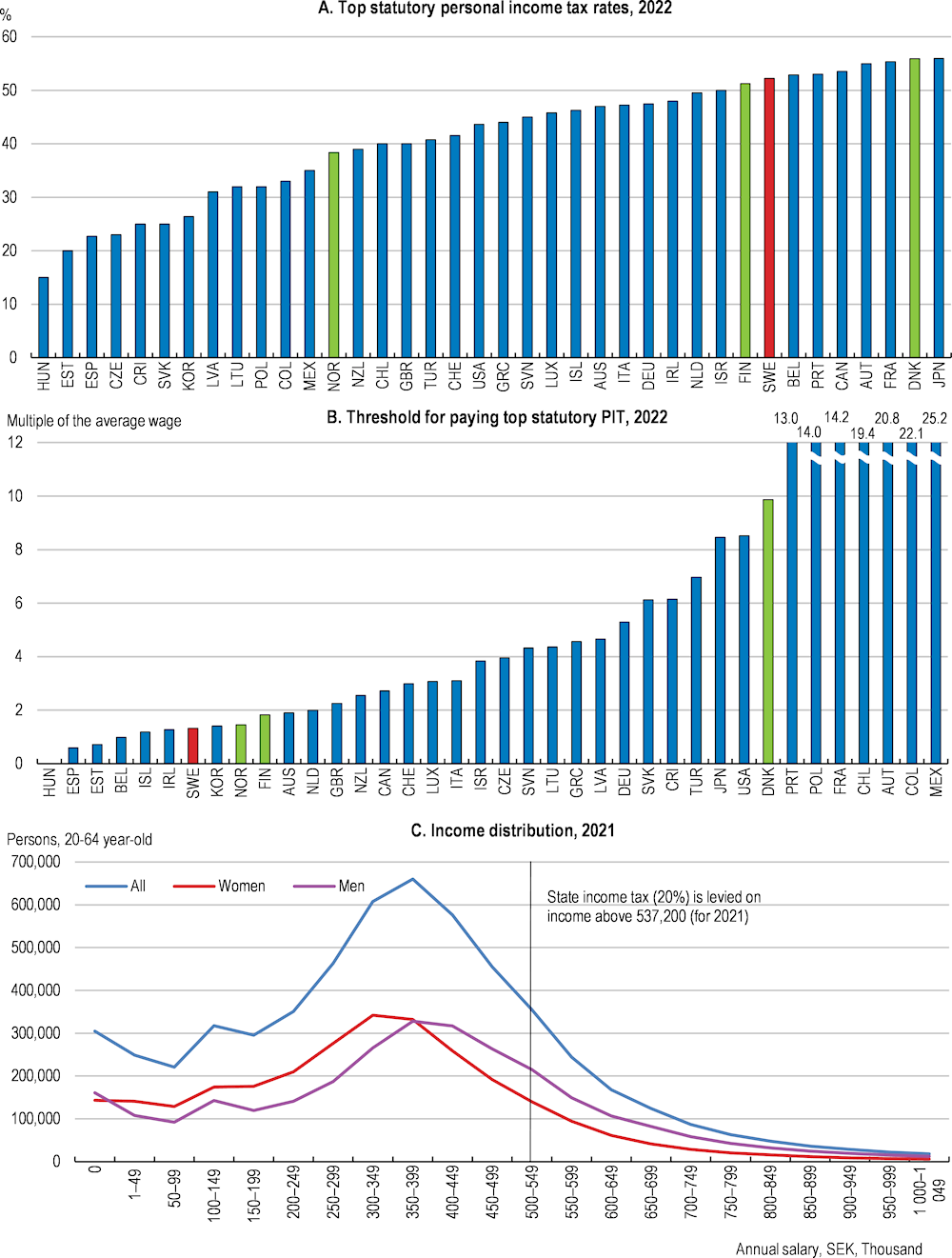

Maintaining high employment is a prerequisite for the sustainability of the Swedish welfare state and to counter the ageing-related contraction of the labour force and its negative fiscal impacts. Sweden has a very high labour force participation rate and one of the highest employment rates in the OECD. The employment rates of women and the elderly are also high in OECD comparison. Even so, unemployment has remained relatively high over the past decade, reflecting a high structural unemployment rate that is now estimated at 7.3% by the National Institute of Economic Research (Konjunkturläget December 2022, 2022). At the same time, labour market mismatch has increased in recent years. Firms report a lack of qualified labour and difficulties in filling vacancies. Labour shortages are most apparent in non-cyclical professions, such as education, health and social care, and in technology and ICT (Statistics Sweden, 2022). A large share of jobseekers lack the needed skills, notably the foreign-born with insufficient education or Swedish language skills. Furthermore, a relatively high labour tax wedge discourages employment and longer working hours, and some recent pension reforms weaken incentives to continue working in old age counteracting a series of other efforts to extend working lives.

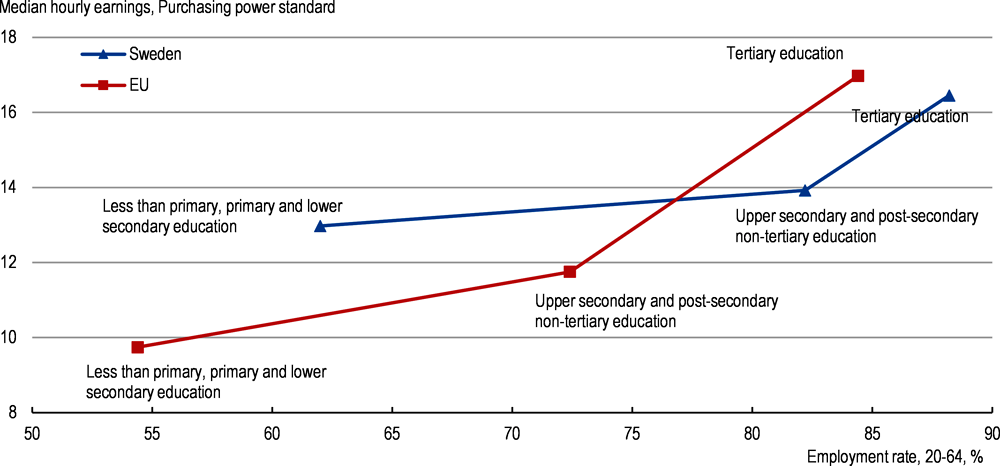

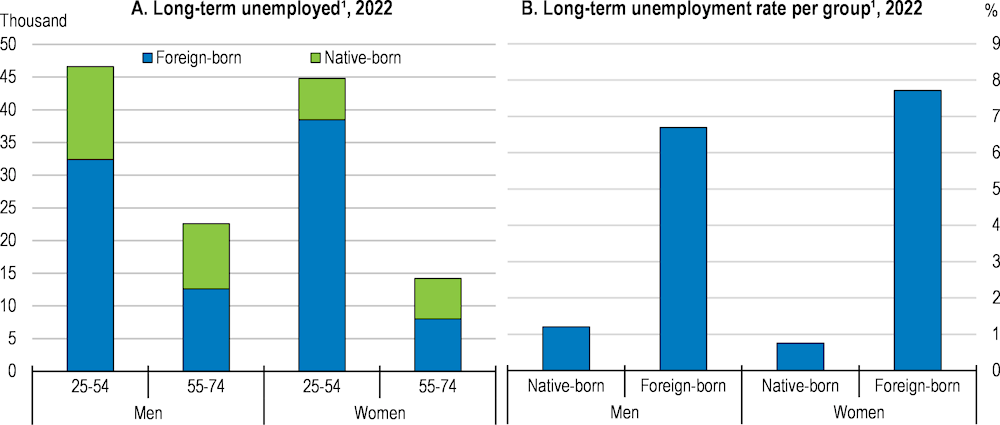

Addressing long-term unemployment notably among the foreign-born

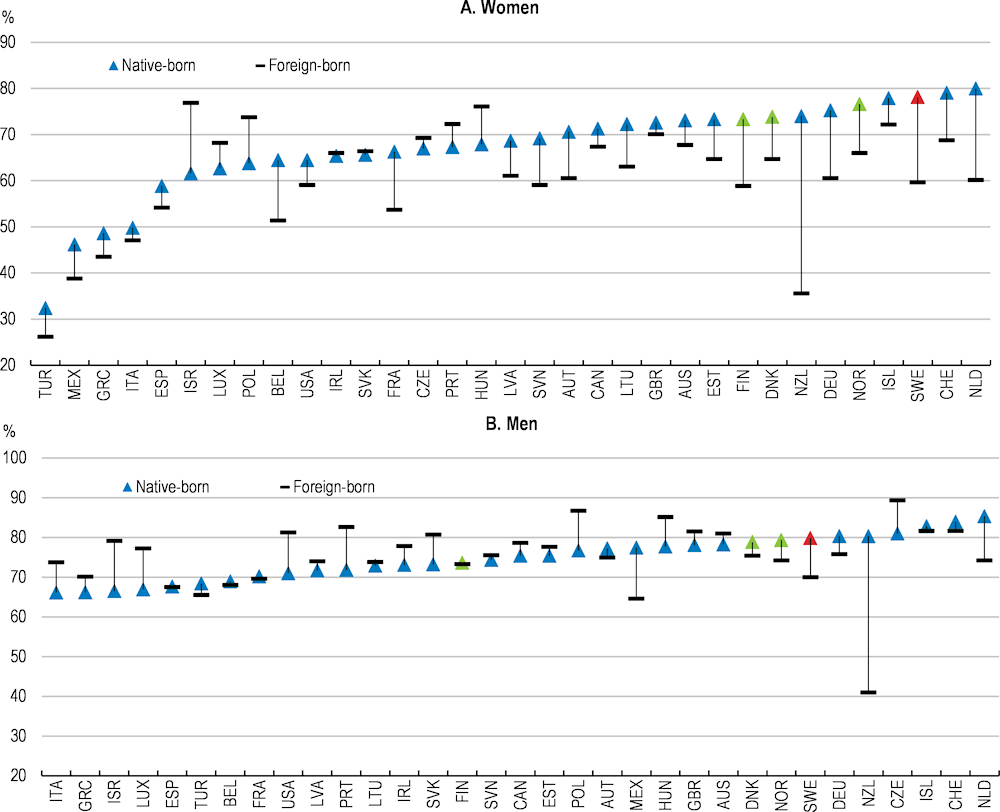

Long-term unemployment is much higher among foreign-born than among native-born people (Figure 1.19). A compressed wage structure raises demands for workers’ productivity, which are in general matched by high levels of skills and education. This high-productivity, high-employment equilibrium is at the centre of the Swedish model characterised by a symbiotic relationship between external competitiveness, a strong social safety net and high public investments in people’s skills and health. However, high skill demands make it hard for those with low education and low skills to find jobs (Figure 1.20). This leads to high unemployment among the foreign-born, who are on average less educated and may lack some of the skills needed to succeed in the Swedish labour market, such as Swedish language skills, qualifications recognised by Swedish employers and more subtle knowledge of Swedish culture and labour market functioning. Empirical evidence suggests that substantial employment penalties are related to migrants’ lower literacy proficiency, but that participation in adult education and training is effective in improving their employment prospects (Bussi and Pareliussen, 2017). Participation in adult education and training is high in Sweden, including among the foreign-born.

Figure 1.19. Foreign-born people are more likely to be long-term unemployed

1. People who have been unemployed longer than 27 weeks, as a share of the 15-74 labour force.

Source: Labour Force Surveys, Statistics Sweden.

Figure 1.20. Wages are compressed and employment gaps large

2018

Foreign-born women, in particular, struggle to enter the labour market. Their employment rate was 18 percentage points lower than that of native women in 2021, although still higher than the employment rate of native-born women in some OECD countries (Figure 1.21). In 2021, foreign-born women made up over a third of the long-term unemployed. They often start from a low level of education (in 2022, over 40% of unemployed foreign-born women had nine years of education or less) and sometimes face strong gender- and family norms.

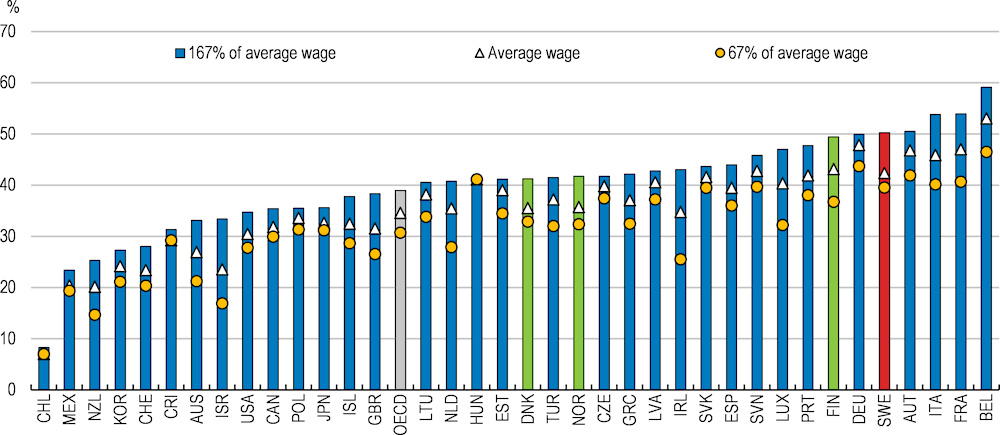

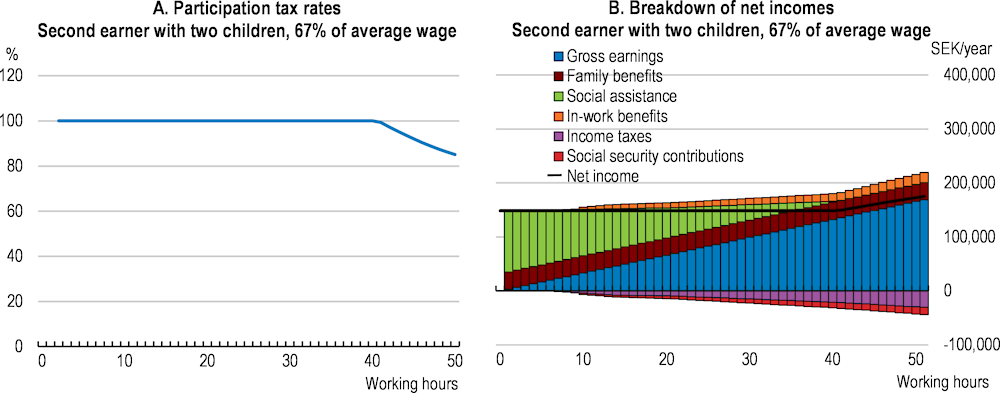

Relatively weak financial work incentives for low-income second earners receiving social assistance can contribute to the low employment rate of female immigrants, despite individual income taxation. For example, a second earner with children taking up a full-time job at 67% of the average wage would lose around 85% in taxes, social contributions and lost benefits (Figure 1.22, Panel A). The weak financial work incentives increase the risk that social assistance recipients remain jobless and end up in a poverty trap.

Figure 1.21. The foreign-born female employment rate is low

2021, employed as share of population, 15-64 year-olds

Low benefit levels can encourage the transition to work but can also involve increased income disparities and a greater risk of financial vulnerability, not least for children. A more gradual tapering of social assistance against work income could improve work incentives and reduce poverty risks. Considering fiscal costs, a gradual tapering over time for social assistance recipients moving into employment could be considered. This would still incentivise workers to grow into higher paid jobs and follow career-enhancing training. The relatively high participation tax rates are mainly driven by a generous level of social benefits combined with their withdrawal krona for (after-tax) krona of work income (Figure 1.22, Panel B). This leads to a participation tax rate of 100%, in other words no income gains by working, when taking a low-paid part-time job (Figure 1.22, Panel A). This provides weak financial incentives to take up low-paid employment despite the Earned Income Tax Credit. Also, social benefits such as the multiple child supplement should be carefully reviewed to see whether work incentives could be strengthened without exacerbating inequality.

Figure 1.22. Low-income second earners face weak work incentives

For Sweden, 2022

Note: Participation tax rates refer to the fraction of income that is taxed away by the combined effect of taxes and benefit withdrawals when entering or returning to work.

Source: OECD TaxBen model. http://oe.cd/TaxBEN.

Another way to counter the low work incentives is to calibrate activation policies to encourage the unemployed to step up their job search. In particular, policies that tie benefit receipt to job search or participation in ALMPs can help to ease any trade-offs between benefit generosity and labour market outcomes. Sweden has relatively demanding activation requirements for jobseekers to be entitled to social benefits (OECD, 2017a). For instance, actively and regularly searching for jobs is a precondition for receiving unemployment benefits. However, Sweden’s employment services are less likely to sanction those who do not comply with the active job search requirements compared with most other OECD countries, including Finland and Norway (Figure 1.23). An empirical analysis on Sweden suggests that more stringent enforcement of activation requirements increases the likelihood of exiting unemployment into employment, albeit at the expense of slightly lower hourly wages (Van Den Berg and Vikström, 2014). Sweden recently reformed its employment service to expand the use of private providers (see below). Private providers usually have less incentives to sanction those who do not comply with the active job search requirement, because this means losing clients (OECD, 2022c). A recent review by the Swedish Unemployment Insurance Inspectorate (IAF, 2021) found that there is a lack of systematic monitoring by the Public Employment Service (PES) of how private providers enforce activation requirements. Improving the monitoring system, for instance based on sanctioning rates across providers, and using this as a basis for conducting more thorough follow-up checks should be considered (OECD, 2022c).

Dropout rates from Swedish language courses and other early ALMP activities for immigrants are higher for women than for men, and activation programmes generally have a smaller effect on women in the Nordics (Nielsen Arendt and Schultz-Nielsen, 2019). Nevertheless, initiatives such as the Establishment Programme for recently arrived immigrants and the pilot project Equal Establishment (see below), both run by the PES, show that, if well-tailored, ALMPs could yield significant effects also for women in Sweden. Both these programmes saw a positive impact on immigrant women’s employment comparable to that for men (Andersson Joona, Wennemo Lanninger and Sundström, 2017; Swedish Public Employment Service, 2022).

Figure 1.23. Sweden has less stringent sanctions for those who do not comply with the active job search requirements

Strictness of sanctions, 2022

Note: Strictness scores in each category range from 1 (least strict) to 5 (most strict). ‘Sanctions' includes 5 items (sanctions for voluntary unemployment, for refusing job offers, for repeated refusals of job offers, for failures to participate in counselling or ALMPs, and for repeated failures to participate in counselling or ALMPs).

Source: OECD Benefits, Taxes, and Wages database (2022).

The sanction regime should be accompanied by effective and tailored job search assistance in order not to impoverish already vulnerable people. Over the past years, Sweden has taken some measures to speed up the integration of newly arrived immigrants, focussing on foreign-born women, like funding to increase the possibilities for persons on parental leave to take part in Swedish language courses and training, as documented in the previous OECD Economic Survey of Sweden (OECD, 2021a). A pilot project, Equal Establishment, targeting refugee immigrants and their relatives was also initiated. The project was a PES-run randomized controlled trial conducted in 16 cities between 2018 and 2021 in which some recently arrived migrants were offered a tailored job matching method and some only took part in regular ALMP activities. The evaluation report by the PES (2022) shows that the new matching method increased the probability of being in work and studies by approximately eight percentage points compared with the Employment Service's regular support. A cost analysis also showed that the project yielded better value for money than regular support, but the pilot project was not scaled up for lack of funding. However, Matching from day one, a method used in the Equal Establishment programme will be taken further in 2023 as part of the Public Employment Service’s efforts to the improve employment outcomes of those furthest away from the labour market.

Sweden has reformed the PES by introducing a purchaser-provider split for activation policies with outcome-based payments, while the focus of the PES has shifted to analytical work and monitoring jobseekers (Bennmarker et al., 2021). At their best, reforms outsourcing publicly financed services to private providers can spur innovation and result in better-quality services at a lower cost. To achieve this, the reform must encourage competition focussed on actually achieving the results desired by the purchaser. This can happen if there are enough providers to stimulate competition, and if outcomes are accurately measured and providers remunerated accordingly.

Jobseekers are segmented into three groups based on their employability (OECD, 2022c). Providers are paid a daily allowance plus a performance compensation based on the employment/education outcome, both of which are differentiated based on a client’s employability in order to ensure providers do not focus their attention on only the clients closest to the labour market. The reform has entailed a significant downsizing of the number of local PES offices and employees, and an increased role for digital services. By the end of 2021 all municipalities had access to the new matching tool KROM, which the jobseekers can use to choose job service providers.

Although it is too early to thoroughly evaluate the reformed PES, there have been indications that remote and sparsely populated regions are not sufficiently covered by private sector providers (OECD, 2022d). Furthermore, municipalities have so far not been allowed to provide matching services as they are confined by law to operating within their proper geographical boundries, while KROM service areas often straddle several municipalities. Simplifying application requirements for providers that are already active in other regions and easing requirements on physical presence in rural areas could enhance competition in these areas. Pragmatic solutions should also be found to allow municipalities to provide matching services in fair competition with private providers. Moreover, the payment model needs continued calibrating to make sure that remuneration is properly adapted to the chances of the jobseeker. Providers in the Swedish market cannot refuse certain jobseekers, but indicators focusing on employment/education outcomes can incentivise providers to persuade jobseekers with low potential to switch to other providers (OECD, 2022c).

The expansion of external providers of matching services should be accompanied by measures to enable jobseekers to choose providers that best satisfy their needs. An increase in the number of providers tends to reduce service quality when jobseekers are unable to make informed choices (Moraga-González, Sándor, and Wildenbeest, 2017; OECD, 2022c). In 2022, to help jobseekers make informed choices, Sweden introduced a system similar to Australia's "Star Ratings" assessment system which rates providers according to their overall performance and makes these ratings publicly available. As of March 2023, it is available in 59 out of a total of 72 service areas. However, for many jobseekers, especially less educated individuals and migrants, it can be difficult to make an informed decision based solely on star ratings. This was indeed the case in Belgium and the Netherlands. The experience from a pilot programme in Belgium (Flanders) suggests that assistance from counsellors was particularly useful for less-educated individuals in helping jobseekers make informed choices, with a large majority of participants reporting satisfaction with their provider choice (OECD, 2022c). Due to technical reasons with the matching service procurement, ratings will be temporarily unavailable for up to 20 months from mid-April 2023. Going forward, ensuring consistency in ratings and avoiding such prolonged gaps will be important to provide jobseekers and the PES with the necessary information. The PES should also consider making indicators such as customer satisfaction survey data available to clients to avoid that providers focus their efforts only on the measured outcomes.

The government should consider shifting the focus of ALMP spending from employment incentives to training. Sweden’s ALMP spending is currently 2.2% of GDP, around the OECD average, but the spending is heavily tilted towards employment incentives rather than training (OECD, 2022b). The government launched the so-called entry jobs (previously establishment jobs) in the fall of 2022 in close cooperation with social partners. Under the programme, the government will pay around half of the wage costs for up to two years when a company employs migrants who have been in Sweden less than three years or someone who has been unemployed for at least two years. The scheme costs around EUR 400 million (SEK 4.2 billion) (European Commission, 2022). Subsidised employment could be a step towards work, but should be provided simultaneously with tailored training and mentoring to be effective in the longer run (OECD, 2022e). In particular, evidence from Denmark and Sweden (e.g. the Establishment lift, a joint programme between three Stockholm municipalities) suggests that involving staff with diverse linguistic and cultural knowledge in skills training could enhance the effects of the training (Penje and Ström Hildestrand, 2022).

Box 1.6. Some recent labour market reforms go in the right direction

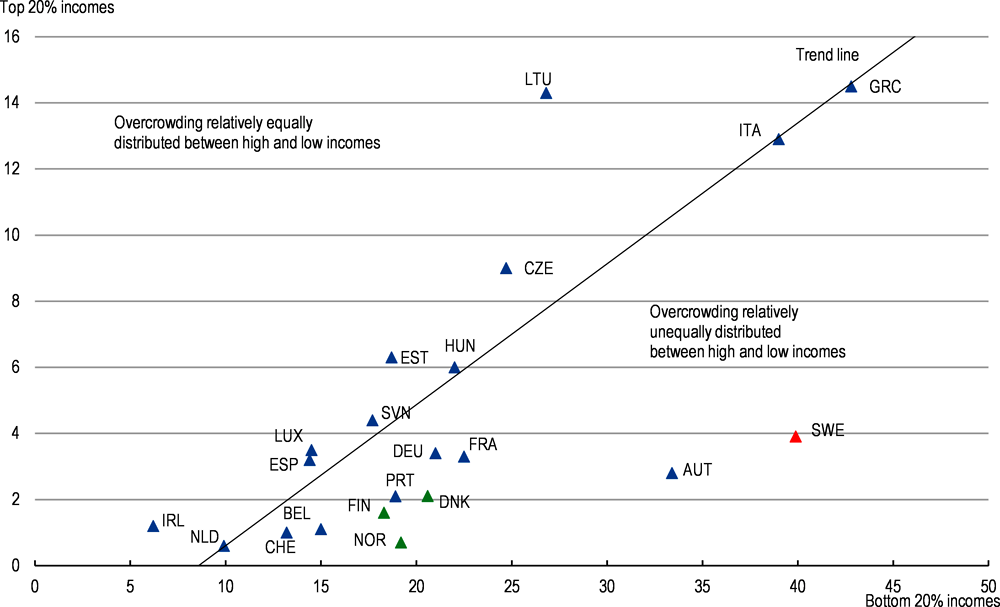

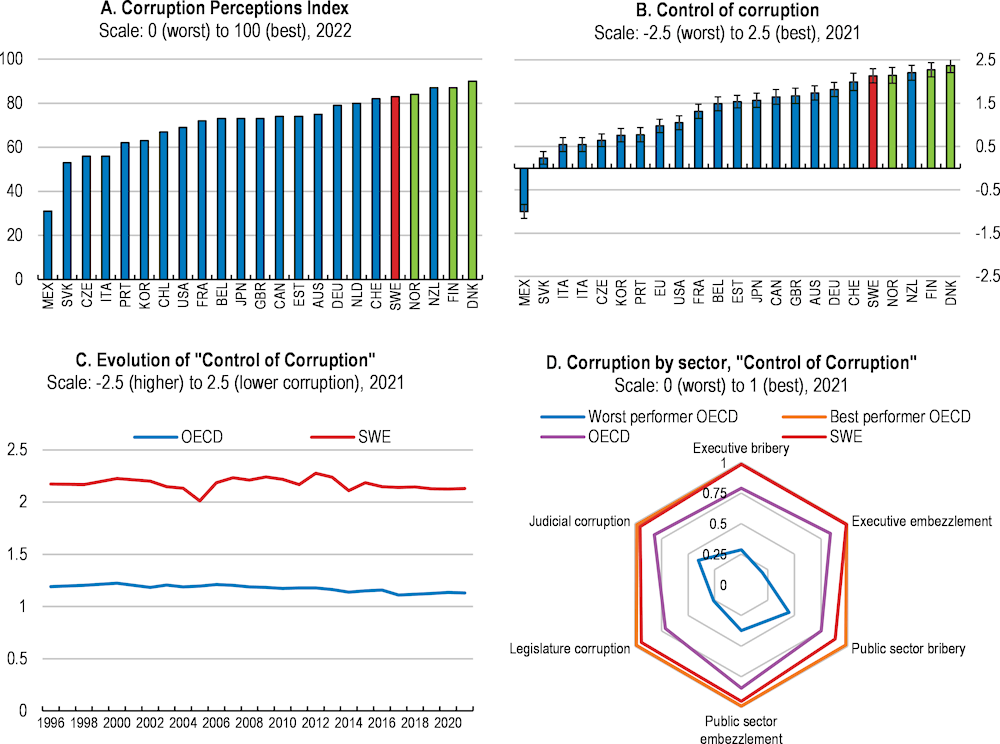

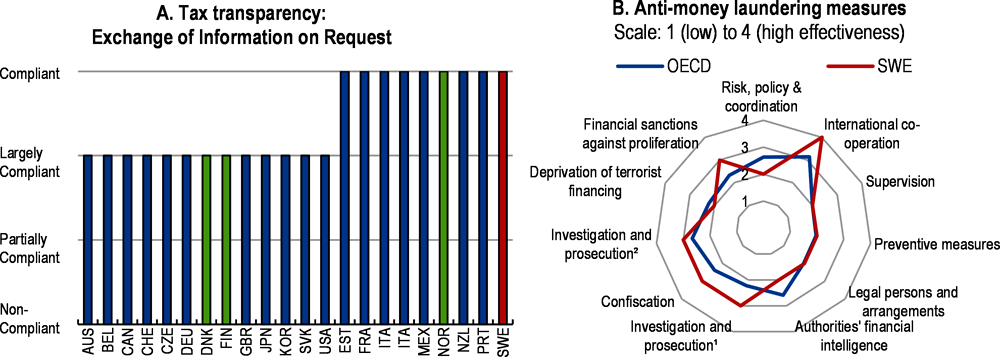

In order to increase labour market flexibility, employment protection legislation (EPL) was reformed in the fall of 2022, in line with the recommendations in the 2021 Survey (Government of Sweden, 2022b). With the new law, employers of all sizes can exempt three persons from the order of priority rules when laying off employees and no longer bear the wage costs during an ongoing dispute concerning the validity of a contract termination. If the ruling is in favour of the employee, he or she will be compensated retroactively. The new act also facilitates conversion of fixed-term contracts into open-ended ones and makes full-time contracts the new norm. Social partners retain the possibility to deviate from many of the regulations in their collective agreements. Another part of the labour market reform package is the introduction of a new support scheme, consisting of both grants and loans of up until 80% of the wage for up to 44 weeks, for experienced (a minimum eight years of work experience is required for eligibility) workers in need of up- or reskilling. In addition, workers who are not covered by a collective agreement will now get access to transition support in the form of job counselling. The new EPL reform will ease financial risks for businesses - especially for small and growing ones – while maintaining predictability and employment security for workers.