This chapter summarises the main findings and recommendations of the OECD assessment of housing affordability in Lithuania. It first presents the main features of the Lithuanian housing market, including the affordability and quality gaps in the housing stock that pre‑dated the current cost-of-living crisis, and highlights housing challenges that have been amplified by the current economic and geopolitical situation. It then provides an assessment of the policies currently in place to address housing affordability. It concludes with a set of policy recommendations that Lithuania could consider to strengthen the supply of and access to affordable housing, and sets out potential priorities for action for the short and longer term.

Policy Actions for Affordable Housing in Lithuania

1. Summary of main findings and recommendations

Abstract

1.1. Profile of the Lithuanian housing market

1.1.1. The cost-of-living crisis and the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine create a challenging policy context

The current policy context is especially challenging in Lithuania. Strong inflationary pressures – driven by increases in food and energy prices – are making it harder for households to make ends meet. Headline inflation in Lithuania peaked at 22.5% in September 2022 before coming down by ½ percentage point in October. Inflation is projected to remain high in 2023 (11.9%) before abating in 2024 (4%) (OECD, 2022[1]). As in many OECD countries, nominal wages have not kept pace with increasing prices, leading to a fall in real wages and a decline in purchasing power, on average, among Lithuanian households (OECD, 2022[2]). Russia’s ongoing war of aggression against Ukraine, which has already displaced millions of people, has put additional pressures on the housing market and contributed to the cost-of-living crisis in OECD countries. Rising energy prices are one factor driving inflation, which have a disproportionate impact on poorer households in Lithuania: between January 2021 and September 2022, the bottom 20% of the income distribution in Lithuania were more impacted by the effect of higher energy prices on total living costs than the top 20% (Bulman and Blake, 2022[3]). The surge in energy prices since the second half of 2021 has generated increased demand for public support schemes to subsidise heating costs and underscored the need to improve housing quality and energy efficiency.

1.1.2. Lithuania’s ageing housing stock is dominated by owner-occupied, multi‑apartment buildings

As in many neighbouring countries, Lithuania’s housing stock is ageing and dominated by owner-occupied, multi‑apartment buildings. Lithuania has the highest rate of home ownership in the OECD, with over 90% of households owning their home (OECD, 2022[4]). This is in large part the legacy of the generalised privatisation of the state‑owned rental housing stock that began in the early 1990s in the transition to a market economy, similar to the evolution of the housing stock in many neighbouring countries. The high rate of home ownership is accompanied by a thin rental market and a highly residual social housing sector. Much of the housing stock is ageing and of poor technical quality, with critical gaps in basic amenities. Multi‑apartment buildings comprise nearly 60% of the housing stock – well above the OECD average of 40% (OECD, 2022[4]). The need to find agreement across multiple owners adds to difficulties in conducting major renovation and interventions aimed at improving the energy efficiency of buildings.

While housing quality has improved in recent decades, progress remains slow. Nearly 80% of the stock was built before 1993, around half of which was developed during the Soviet era (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[5]). Persistent housing quality deficiencies are driven by multiple factors: poorer quality construction materials, lower construction standards, along with the absence of a formal institutional and legal framework for dwelling operation and maintenance in the years following the privatisation process, the slow pace of housing improvements in the decades since their construction, and limited household resources to dedicate to housing maintenance.

1.1.3. The residential sector casts a large environmental footprint, and energy poverty has become an even bigger issue than before Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine

Most housing is energy inefficient, with the residential sector accounting for over a quarter of the country’s total final energy consumption. Final energy consumption in Lithuania has increased in recent decades, rising by nearly 19% between 2005 and 2018, as consumption levels declined on average in EU countries (European Commission; European Investment Bank, 2020[6]). The older segment of the multi‑apartment buildings constructed before 1993 consumes about twice as much energy than newer buildings. Around three‑quarters of multi-family dwellings, and nearly 60% of single‑family homes, have been attributed a very low grade in terms of energy efficiency, while less than 2% have received a high grade of energy efficiency (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[5]).

Energy poverty is a continued challenge among many low- and middle‑income households – a concern that is exacerbated by the significant rise in energy prices in recent months. In 2020, more than one‑third of Lithuanian households in the bottom quintile of the income distribution and over a quarter of households in the third quintile suffered from energy poverty – nearly three times the OECD average for households in the bottom quintile, and nearly six times the OECD average for households in the third quintile (OECD, 2022[4]). Over the past 15 years, electricity prices rose by nearly 60% in Lithuania, well beyond the EU average of 37% (Eurostat, 2021[7]). Recent months suggest even faster growth in energy prices: in September 2022, Lithuania recorded the fourth-highest annual growth rate in energy prices, at 75%, behind Türkiye (146%), the Netherlands (114%) and Estonia (78%) (Eurostat, 2021[7]). Lithuania’s high inflation rates are largely driven by an increase in energy prices (and, to a lesser extent, in food and housing). Higher energy prices have an especially strong impact in Lithuania, due to the high energy intensity of the economy and a very large share of oil and gas in the energy mix (OECD, 2022[8]).

1.1.4. Since 2010, housing prices have risen faster than the OECD average and accelerated during the early stages of the COVID‑19 pandemic

Housing prices in Lithuania have increased substantially over the past decade, and accelerated since the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic. Between 2010 and 2019 – prior to the pandemic – real house prices increased by 33%, well above the OECD and EU averages of 17% and 6%, respectively. Real house prices continued to rise through the pandemic, increasing by 18% between 2019 and 2021 – again well above the OECD and Euro Area averages of 14% and 10%, respectively (OECD, 2022[9]). Meanwhile, real rent prices increased by nearly 70% in Lithuania between 2010 and 2019, representing the second-highest jump in the OECD over this period, after Estonia. Between 2019 and 2021, rents in Lithuania dropped slightly by around 1%, reflecting the much more muted impact of COVID‑19 on rental prices relative to house prices, consistent with evidence from other OECD countries (OECD, 2022[9]). There is considerable variation in house prices across regions and among different dwelling types. While the average purchase price remains the highest among multi‑apartment buildings in the three largest cities – Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda – house prices outside these cities have recorded faster growth since the pandemic (OECD, 2022[9]).

Meanwhile, rising construction costs are making it harder to build affordable housing. Since the second half of 2021, construction costs for residential buildings have increased dramatically, with a year-on-year increase of 19% in September 2022 – more than double the growth between September 2020 and September 2021 (Lithuania Statistical Office, 2022[10]). Growth in construction costs have been due to the rising costs of construction materials and labour in the construction sector. Skill shortages in the construction sector have contributed to a near-doubling of wage growth to 14% in the course of 2022 (OECD, 2022[1]).

1.1.5. Low household spending on housing costs masks emerging affordability challenges

Low average household spending on housing in Lithuania masks a persistent housing quality and emerging affordability challenge. Before the current cost-of-living crisis, despite rising housing prices, average household spending on housing was relatively low in Lithuania relative to other OECD countries. In 2020, the most recent year for which data are available, overall housing costs – which include housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels – equalled 15% of total household consumption expenditure in Lithuania, compared to an OECD average of over 22% (OECD, 2022[4]). Fewer than 3% of all Lithuanian households were overburdened by housing costs, in that they spent more than 40% of their disposable income on housing. The share reached just 9% of households in the bottom quintile of the income distribution, well below the OECD average of 27% (OECD, 2022[4])

These figures nevertheless conceal the persistent albeit narrowing housing quality gaps, as well as the inability of many households to afford a commercial mortgage or rent in the private sector. Low average household spending on housing is largely due to the high rate of outright homeowners in Lithuania, which means that few households make monthly mortgage or rental payments; however, many Lithuanian households cannot reasonably afford a mortgage to move into a better-quality house. The results of an OECD simulation estimated that, prior to the current crisis, only around 40% of households earned a sufficient income in the pre‑COVID period to reasonably afford a mortgage to purchase a standard 50m2 flat in Vilnius; the share increased to 60% in Kaunas and Klaipėda. An OECD simulation in Latvia – a country with a similar housing market profile and historical development – found comparable results, whereby only around 43% of households could reasonably afford the mortgage for an existing flat in Riga in 2019 (OECD, 2020[11]).

The current crisis has strongly affected housing markets across the OECD and threatens to create further challenges for Lithuanian households. Across the OECD, higher interest rates have dented momentum in the market, leading to a fall in sales, mortgage lending and housing prices (OECD, 2022[1]). On the one hand, the very high rate of outright homeowners in Lithuania means that only a small share of households are affected by higher interest rates. On the other hand, the combination of Lithuania’s record growth in mortgage lending in 2021, where the total value of outstanding mortgage loans was 11% higher relative to the previous year (European Mortgage Federation (EMF), 2022[12]), and the fact that nearly all mortgages are issued on a variable rate, suggests that households paying off a mortgage may struggle to afford repayments in the months to come.

1.1.6. Demographic pressures and high levels of regional disparities create additional challenges for policy makers

The current cost-of-living crisis co‑exists alongside longer-term demographic challenges. The population of Lithuania declined by around 1% annually over the past two decades, from around 3.5 million people in 2000 to less than 2.8 million in 2021 (OECD, 2023[13]). Further, the population is ageing, with young people (aged 15‑24) comprising less than 10% of the total population. These demographic trends have implications in the housing market: over 42% of seniors aged 65 and over live in single‑person households – the third-largest share in the OECD, up 2 percentage points from 2010 (OECD, 2022[4]). Looking forward, the population is projected to continue declining by around 8% over the next decade, with the biggest drop among children and young adults. By contrast, the number of seniors is projected to grow, including by over 25% among 70‑ to 74‑year‑olds (OECD, 2023[14]).

Finally, Lithuania records among the highest levels of regional disparities in the OECD. Over 60% of the population lives in the three counties that are home to the largest cities: Vilnius, the capital region (30% of the total population), Kaunas (20%) and Klaipėda (12%). No other county records more than 10% of the national population (OECD, 2023[15]). The biggest Lithuanian cities record GDP per capita, household income and productivity levels near the OECD average, while smaller, rural areas continue to lag behind. The main drivers of these disparities include low economic growth and job creation, and insufficient labour mobility – due in part to high home ownership rates and a shallow rental market (Blöchliger and Tusz, 2020[16]).

1.2. Advancing public policies for quality housing at an affordable price

1.2.1. The Lithuanian Government has stepped up policy support for housing in recent decades, but further actions are needed

In recent years, Lithuania has made efforts to improve housing quality and make housing more affordable to low-income households and young people. Since the mid‑1990s, programmes and partnerships with financial institutions have aimed to improve the quality and energy efficiency of the housing stock. In addition, several housing support schemes have become increasingly targeted, and new schemes – such as a housing benefit scheme to support low-income tenants – have been introduced, helping to channel public support to households in greatest need of support. The government has also made efforts to combat the stigmatisation of tenants in social housing by recommending a limit to the share of units in a residential building (two‑thirds) that can be used as social housing. In parallel, policy makers have taken steps to encourage the expansion and formalisation of the private rental market. Nevertheless, an important effort is necessary to address the country’s persistent and emerging housing challenges, and to elevate the strategic importance of housing policy on the political agenda.

1.2.2. Efforts to improve housing quality and energy efficiency should be accelerated

As in many OECD countries, improving the quality and energy efficiency of the existing housing stock is one of the biggest challenges for housing policy makers in Lithuania. Lithuania’s sustained efforts to improve housing quality and the energy efficiency of the housing stock through successive government programmes since the 1990s should be commended. Current support schemes are dominated by the provision of subsidies to households to renovate flats in multi‑apartment buildings. Between 2013 and 2020, an average of roughly 340 renovations have been completed annually, with a peak of 769 multi-family buildings in 2016 (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[5]). Nevertheless, despite longstanding public support schemes for residential renovations, the pace of renovations remains far too slow. As of 2020, only 8% of the 37 136 multi‑apartment buildings built before 1993 had been renovated. The National Audit Office reports that at the current pace, it would take roughly 100 years to modernise the most energy-intensive multi-family apartment buildings in the country.

To speed up progress towards its energy efficiency objectives and make greater headway in reducing energy poverty, Lithuanian policy makers could pursue several avenues to accelerate the pace of building renovations. These include:

expanding funding support for residential modernisation schemes to meet rising demand;

making the renovation process more efficient, including through technological advances like the use of prefabricated multifunctional renovation elements, which have proven effective in peer countries, including Latvia, Estonia and the Netherlands;

strengthening the technical and financial capacity of municipal authorities’ capacity to undertake renovations, including through the development of dedicated municipal companies to manage complex renovation projects; and

increasing public support and awareness of the benefits of energy efficiency upgrades.

1.2.3. Increasingly targeted housing supports are welcome, with further gains possible

In recent years, Lithuania has provided targeted housing supports to make housing more affordable for low-income and vulnerable households, including direct financial assistance to households to cover housing-related costs and the provision of social housing. A housing allowance introduced in 2015 provides partial reimbursement of rental housing costs (Būsto nuomos mokesčio dalies kompensacija) to tenants who meet the income and asset tests and have a formal registered minimum one‑year lease for a dwelling in the private rental stock. While the payment rate is among the highest of housing allowances in the OECD, coverage of the benefit is very limited: take‑up rates have progressively increased since its introduction, but still amounted to less than 1% of the total population in 2021 (OECD, 2022[17]). One factor in its limited reach is likely because eligibility requires the registration of a formal rental contract in the State Enterprise Centre of Registers and a rental contract of at least one year, along with other income‑related eligibility criteria for the tenants (OECD, 2022[17]). Other factors include the relatively recent introduction of the scheme (2015), as well as the persistent stigma associated with recipients of social assistance and the continued importance of the shadow economy in Lithuania (which may make households hesitant to apply for fear of income checks) (Gabnytė and Vencius, 2020[18]).

A recent reform intends to transfer a portion of the financial responsibility of the housing benefit scheme from the State to municipalities in January 2024, yet to-date no additional financial resources have been foreseen for municipalities to cover these costs. In addition, eligible low-income households can receive an allowance to cover heating, drinking water and hot water costs (Būsto šildymo išlaidu, geriamojo vandens išlaidu ir karšto vandens išlaidu kompensacijos). The reach of the monthly heating allowance is much broader than the housing benefit scheme; demand for support through the scheme has further increased in recent months following the dramatic increase in energy prices.

The provision of social housing represents another important form of housing support for very low-income and vulnerable households yet demand far exceeds supply. Representing less than 1% of the total housing supply, Lithuania’s social housing sector remains extremely small, with the waiting list amounting to around 10 000 households nationally, just under 1% of all households. The stock suffers from significant quality gaps, and evictions in the social housing sector have been on the rise. In an effort to expand the supply, the government has introduced several measures. First, a new law on territorial planning grants a density bonus (the possibility to develop additional square metres than otherwise allowed) to construction projects that devote at least 10% of development to social housing. Second, adjustments to the social and municipal housing schemes should facilitate the allocation of social housing to single‑parent families, with new rules encouraging the allocation of municipal housing to households in greatest need. Third, policy makers introduced a long-term rental sublease scheme in 2019 (Būstų nuoma ne trumpesniam kaip 5 metų laikotarpiui iš fizinių ar juridinių asmenų), whereby property owners may lease their private rental dwellings to municipalities for use by tenants who qualify for social housing; a portion of the rental payment is made directly to property owners by the municipalities. However, the programme has struggled to overcome the shortage of adequate and affordable rental dwellings available for lease in the market, as well as a lack of interest from property owners to lease their dwellings to social housing tenants. Insufficient incentives for property owners, administrative hurdles, and a persistent stigma associated with social housing residents are among the factors to explain the low take‑up. Despite progress, housing support schemes for low-income and vulnerable households continue to fall well short of need, and the current cost-of-living crisis is putting additional pressures on low-income households. In the current circumstances, it is particularly urgent to protect the most vulnerable. Policy makers could consider targeted measures, including:

leveraging well-located public land for the development of social and affordable housing, when it is accessible to employment centres and infrastructure;

streamlining administrative procedures and expanding financial incentives to property owners to participate in the long-term rental sublease scheme (for instance, through tax credits);

extending the reach of some housing support schemes to reach households who struggle most in the housing market, including the housing benefit scheme; and

introducing measures to address some of the causes of eviction and/or provide timely support to households facing evictions, such as reminders to households that have missed a rental payment, or requiring that municipal authorities be informed when an eviction has been ordered by the court so that public authorities can reach out to provide support.

Additional proposed amendments to housing support schemes that are currently under discussion could help to expand their reach. These include, for instance, increasing the annual income and asset limits to determine eligibility for various public supports for housing.

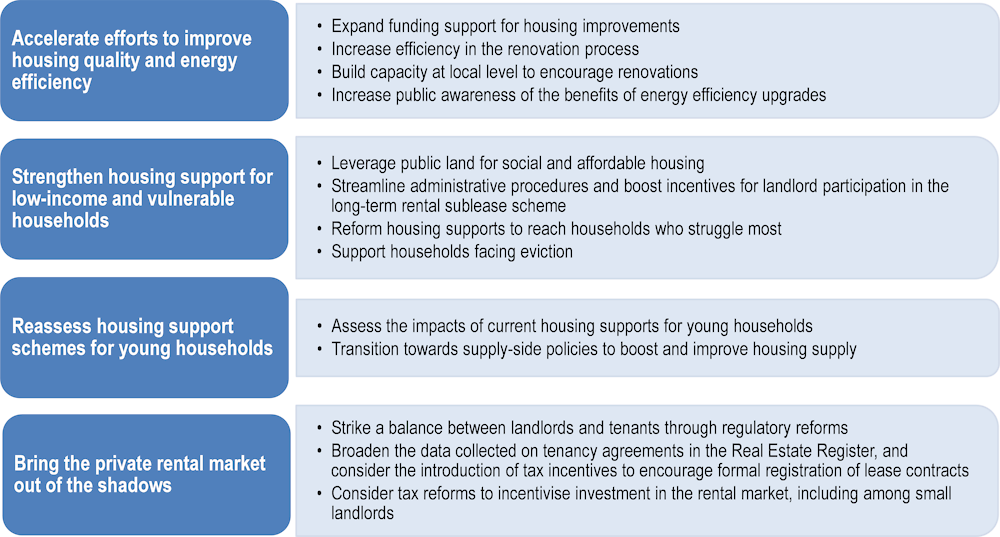

The core recommendations for Lithuanian policy makers to deliver quality housing at an affordable price are summarised in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1. Key recommendations to deliver quality housing at an affordable price in Lithuania

1.2.4. Home ownership support schemes for young households should be reassessed

Despite the relatively high home ownership rate among young people in Lithuania, nearly two in five people aged 20 to 29 years old live with their parents. The government operates two programmes to support young families to purchase their first home by providing financial support for a down payment. Both programmes target households under 36 years old and are operated by the Ministry of Social Security and Labour. A means-tested housing credit support programme, Parama bustui isigyti, provides households who meet income and asset tests with a subsidy to contribute to a mortgage or down payment for the purchase of their first home. The reach of the programme thus far has been relatively modest, covering less than 3% of all new mortgages between 2015 and 2019; just over 300 families benefitted in 2020. A second scheme was introduced in 2018 through the Law of the Republic of Lithuania on Financial Incentive for Young Families Acquiring a First Home (Finansine paskata pirmaji busta isigyjancioms jaunoms seimoms). Contrary to the means-tested housing credit support programme, under this scheme households are not required to meet income or asset tests; however, young families must purchase a home outside the main cities (no such geographic limitation exists under the means-tested scheme). There is also no requirement that the home purchased must be used as a primary residence. The reach of the regional scheme has been much broader, supporting over four and a half times more beneficiaries than the means-tested scheme in 2020 – in part because the programme initially offered more generous financial support than the means-tested programme; since then, the benefit amounts of both programmes have been harmonised.

The Lithuanian authorities are currently re‑assessing the support schemes targeting young families, which is a welcome development. There is strong potential for a share of the public subsidy to be captured by lenders, since the subsidy amount depends on the loan value rather than the asset value. Further, the programmes are costly and, in the face of the non-means-tested scheme, it is not evident that it facilitates home ownership for households which could not otherwise afford to buy a home. Moreover, the schemes aim to simultaneously respond to diverse housing, demographic, regional development and social policy objectives; a housing support measure may not be the most effective and efficient way to meet regional development and demographic objectives. Accordingly, an in-depth assessment of the take‑up and impact of these support programmes would help to better understand whether, and to what extent, these programmes have been effective in expanding home ownership among young households who would not otherwise have been able to purchase a home. The current context makes this assessment even more necessary to be able to make the best use of resources when confronted with multiple urgent demands.

In parallel, the government could consider more effective alternatives to these programmes that go beyond demand-side supports to promote home ownership. In other OECD countries, demand-side home ownership support schemes have been demonstrated to drive up housing costs overall – particularly when they are not accompanied by efforts to increase the housing supply (see OECD (2021[19])). Instead, the Lithuanian authorities could consider investments in the expansion of and improvements to the supply of social and affordable dwellings to support households – including young households – in the housing market. At the same time, policy makers could consider expanding housing supports for young people beyond home ownership support, including in the rental market.

1.2.5. Further efforts to bring the private rental market out of the shadows should be pursued

Lithuania’s formal rental market is thin and, for many households, unaffordable. Estimates of the size of the informal rental market vary. An estimate carried out by the State Tax Authority estimated that 20% of rental transactions were informal; stakeholders interviewed by the OECD estimated the size at 80%. The historic evolution of the housing market in Lithuania is in part responsible, along with public policies that favour home ownership over renting. The tax system, for instance, is more advantageous to homeowners relative to tenants, and to corporate investors in the rental market over small property owners; together, these policy distortions disincentivise investment in new rental construction and facilitate informality in the rental market. Further, tenancy arrangements fail to strike a balance between the interests of property owners and tenants, reducing the attractiveness of renting in the formal market for both parties. Aside from the losses in tax revenue, an informal rental market limits the protections and security afforded to both property owners and tenants and, by rendering it impossible to access rental subsidies, makes access to affordable housing even more limited.

Recent advances, including the introduction of a system of business certificates, have aimed to encourage formality in the rental market and generate additional revenues for municipalities. Business certificates aim to provide a faster, more financially advantageous option for small retail investors to declare rental properties for tax purposes; since 2012, small retail investors have the option to purchase a business certificate from the municipality, which enables them to avoid the 15% tax rate on gross rental income and instead pay a lump sum tax. Data provided by Vilnius municipality indicate an increasing number of certificates being issued since their introduction, but numbers remain small considering the total number of apartments in Lithuania. For example, in the Vilnius municipality, 25 778 residents purchased business certificates in 2022, a 7% increase compared to 2021. Nevertheless, more should be done to bring the private rental market out of the shadows. This includes:

Balancing the rights and responsibilities of tenants and property owners to make the rental market more efficient and affordable in the long term. This means, for instance, providing more protection for landlords in case of insolvency of the tenant and, at the same time, balanced protections for tenants. Another key step will be to broaden the data on rental agreements currently collected in the Real Estate Register to include up-to-date data on tenancy agreements (including flat size, rent levels, contract termination and renewals). This should be coupled with tax incentives to encourage the formal registration of lease contracts in the Register, which together could help transition away from the continued practice of oral rental agreements. These reforms could contribute to creating a more secure environment for property owners and investors, as well as good-quality secure housing for tenants; the recent experience of Latvia in reviewing tenancy regulations could provide inspiration to Lithuania.

Enabling property owners to deduct part of the costs derived from the lease of residential units, which could help to incentivise investment in the rental market. In most OECD countries, owners are typically taxed on their net rental income, enabling them to deduct costs such as mortgage interest from their taxable rental income. From the investors’ perspective, this would make the rental activity as attractive as investing in other assets, especially as the costs generated by renting, such as maintenance and interest payments, are generally higher compared to other asset classes.

Introducing tax incentives to increase the supply of affordable rental housing, which could also help to expand the rental housing supply and address housing affordability gaps.

1.3. Making housing a policy priority in Lithuania

In addition to adjustments to the existing housing support schemes, a number of more structural challenges remain to developing a more affordable, sustainable housing market in Lithuania. This includes persistent governance challenges, low levels of public investment and spending on housing, and the low prioritisation of housing policy on the government agenda. The current challenging economic and geopolitical context will exacerbate the housing affordability challenge and accentuate the need for more rapid improvements to the quality and energy efficiency of the housing stock, as policy makers must continue to navigate the ongoing recovery from the COVID‑19 pandemic, respond to the current cost-of-living crisis, and manage the far-reaching impacts of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. Low-income and vulnerable households, who spend a disproportionate share of their income on energy costs, are especially at risk.

1.3.1. Persistent governance, investment and spending challenges in housing policy

Housing policy making remains fragmented across ministries and levels of government, with a limited strategic vision of housing. At central level, the Ministry of Environment (MOE) and the Ministry of Social Security and Labour (MSSL) have the bulk of housing-related policy responsibilities, including the design of the main housing schemes to facilitate energy efficiency upgrades in the existing stock and to support households in need. Meanwhile, municipal authorities have a central role in the implementation of national housing support schemes and in the delivery and management of social and municipal housing, yet lack resources, capacity and a strategic voice in policy development. Contrary to over 20 OECD peers, there is no up-to-date national strategy to guide housing priorities, public spending or investment. The most recent Housing Strategy 2020 was approved in 2004 and has not been updated or adjusted to the evolving circumstances since then.

Further, even though the government has gradually increased investment and spending levels on housing in recent years – and particularly since the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic – levels remain very low overall relative to other OECD countries. Between 2000 and 2019, public investment in housing and community amenities in Lithuania averaged around 0.1% of GDP, peaking at 0.2% of GDP in 2009, before dropping significantly following the Global Financial Crisis (OECD, 2022[4]). Until 2018, public investment in housing and community amenities in Lithuania remained well below the OECD average, with the gap closing in 2018, when public investment levels in Lithuania and the OECD both averaged around 0.22% of GDP. Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that, even though Lithuania has closed the public investment gap in housing in recent years, levels remain low overall – both for Lithuania and for the OECD (OECD, 2022[4]). In parallel, over the past two decades the State has gradually withdrawn from funding social housing development, leaving the bulk of funding for social housing development to be covered through grants from EU structural funds and, to a lesser extent, municipalities, whose revenue‑raising powers have, however, remained unchanged.

Finally, there is a large and growing mismatch between the housing-related responsibilities of municipal authorities and their technical and financial capacities. Municipalities are responsible for managing the social and municipal housing stock; administering the rental compensation scheme; and supporting the implementation of the multi-family apartment modernisation programme. However, they are constrained by low levels of fiscal autonomy that limit their capacity to act and invest strategically, along with scarce financial resources. Several factors are at play: a highly centralised fiscal framework; heavy reliance of municipalities on central government assistance and EU funding; a very small share of tax revenue (taxes and fees represented less than 4% of total municipal revenue in Lithuania in 2021, compared to an OECD average of over 33%) (OECD, 2022[20]); stringent rules that limit municipalities’ ability to borrow for investment purposes; and a property tax regime that is poorly exploited, as discussed below.

1.3.2. Setting a strategic agenda for housing policy

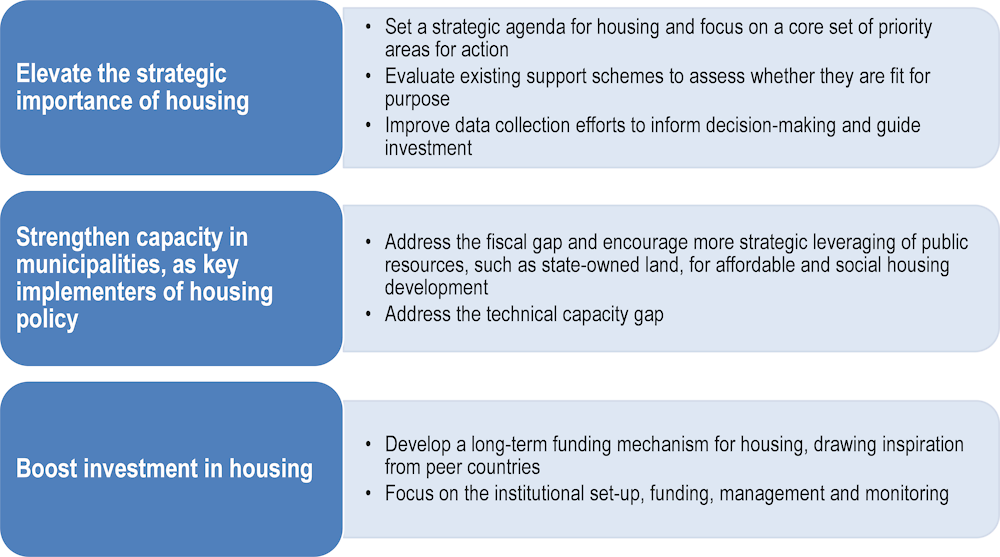

There is considerable scope for Lithuanian policy makers to develop a more integrated, strategic agenda for housing policy. A roadmap for policy makers could be structured around three core principles (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Key recommendations for setting a strategic agenda for housing policy

First, there should be one lead ministry for housing that would be responsible for developing, monitoring and updating a new housing strategy and lead reforms of housing benefits and policies in co‑ordination with the other relevant ministries. There are different options in this respect. One option could be to establish a new Ministry of Housing, which could take up the housing portfolio from the other ministries; Germany has recently established a dedicated Federal ministry for housing. For this option to work, the new Ministry must have a clear mission and policy remit and be appropriately resourced in terms of both human and financial capacity. Relevant staff from the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Social Security and Labour (and other ministries) could be transferred to the new ministry. Alternatively, the housing responsibility and the staff working on housing could be brought together under a dedicated Minister for the housing portfolio, but housed within an existing Ministry (e.g. the Ministry of Environment or Social Security and Labour, which are currently sharing responsibilities for housing). This model has recently been introduced in the Netherlands, within the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. Regardless of the final administrative model chosen, it is important that there is a clear housing responsibility within the government and the minister and his/her staff take an active role in leading the development of a new housing strategy and in co‑ordinating the implementation of housing policies and support schemes across relevant ministries and local authorities. Further, given the skills shortages in the construction sector, it will be essential for Ministries with responsibilities relating to labour market regulation, skills development and housing development to work together to develop synergies across policy areas; such an effort could be chaired by the new Ministry for housing.

The lead housing ministry could prioritise the following actions:

Set a strategic agenda for housing and focus on a core set of priorities for action: For instance, analysis by OECD and others suggests that housing quality and affordability gaps are among the most pressing policy challenges that could guide government housing priorities. The leading ministry could strengthen communication on the importance of tackling these issues, both within the government and with the general public to raise awareness. The recent engagement between the Latvian Government and parliamentarians to raise the strategic agenda for housing could provide inspiration.

Evaluate existing housing support schemes to assess whether they are fit for purpose: Many existing housing support measures consist of demand-side supports for tenants and potential homeowners, some of which will continue to be warranted in the current uncertain context. Nevertheless, more attention could be focused on supply-side interventions, including investments in the social housing supply, improved incentives to private property owners to lease their dwellings for social purposes, and accelerated efforts to undertake residential renovations, with targeted support to low-income and vulnerable households.

Improve data collection efforts to inform decision-making and guide housing investment: Lithuania could strengthen evidence‑based policy making to inform strategic decisions about where, and to whom, to allocate funding for housing, taking inspiration from OECD peers like Slovenia, Estonia and Denmark.

Second, sustained efforts to strengthen municipal capacity will be necessary, given the key role of local authorities in housing policy investment and implementation. Lithuania continues to have one of the lowest rates of property taxation in the OECD, representing roughly 1% of total tax revenue and 0.3% of GDP in 2020 (compared to around 5% of total tax revenue and 1.8% of GDP on average across the OECD) (OECD, 2021[21]). In particular, recent reforms to fully assign property tax to municipalities should be accompanied by continued efforts to raise and reorganise municipal own-source revenues, for example by increasing municipalities’ capacity to borrow for investment as well as incentivising municipalities to more strategically leverage State‑owned land for social and affordable housing development. A reform adopted in December 2022 is expected to allow municipalities some borrowing capacity, within certain annual limits set by Parliament.

To strengthen capacity within municipalities, as key implementors of housing policy, the Lithuanian Government could consider:

Addressing the fiscal gap and encouraging more strategic leveraging of public resources, such as land: This includes continuing efforts to increase and reorganise municipal own-source revenues and to provide guidance and incentives to municipalities to more strategically leverage state‑owned land for affordable and social housing development and other fiscal reforms.

Addressing the technical capacity gap: This could involve mobilising the new regional councils to improve co‑ordination of supra-municipal investment projects and incentivising inter-municipal co‑operation in key housing areas; another strategy in OECD countries is to develop municipal and/or metropolitan-scale agencies in strategic policy areas, such as housing, land-use planning, transport and economic development, in the spirit of the Vilnius municipal enterprise, Vilnius City Housing.

Third, boosting co‑ordinated long-term investments in housing should be a top priority. Lithuania could consider establishing a long-term sustainable funding mechanism. There is extensive experience in OECD countries in this area. The institutional set-up can vary (a new institution or existing funding institutions with additional resources; public body or not-for profit body). The key idea is that the fund could start with some initial equity, borrow to finance new affordable housing and eventually use a share of rents to finance new affordable housing development. Relevant experiences for Lithuanian policy makers to consider include:

Denmark’s National Building Fund: A dedicated, stand-alone, self-governing funding institution that was established by housing associations to promote the self-financing of construction, renovations, improvements and neighbourhood improvements. Funding is based on a share of tenants’ rents and contributions from housing associations to mortgage loans.

Austria’s affordable and social housing model: Austria’s funding approach relies on limited-profit housing associations that operate revolving funds under the supervision, and with the steering of, the federal, regional and municipal governments. Projects developed by limited-profit housing associations are typically financed by multiple sources, including tenant contributions, housing associations own-equity, and public and commercial loans.

The Slovak Republic’s State Housing Development Fund: A revolving fund established to finance the housing priorities of the government, the Fund is an independent entity supervised by the Ministry of Transport and Construction. Originally financed exclusively from the State budget, the Fund currently draws on small levels of government funding and European structural funding, along with repayments on the loans it issues. It supports both new development and renovations to the existing stock.

Latvia’s newly established Housing Affordability Fund: Latvia is setting up a new funding scheme to channel investment in affordable housing, with initial funding from the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility, with the possibility for additional resources from State and commercial loans. In a first phase, the Fund intends to finance the construction of new affordable rental housing outside the Riga capital area, which will be leased at below-market rents to households that meet income thresholds requirements.

Key features to be considered by Lithuanian policy makers in establishing a dedicated funding mechanism for affordable housing include: defining the scope and activities to be supported through the Fund, including the type of housing to be support (e.g. new rental and/or owner-occupied housing; renovations of existing dwellings; etc.); determining the institutional set-up of the Fund (e.g. within or outside government); identifying potential funding resources that could be mobilised at different stages (including share of State funds, concessional loans, commercial loans, State guarantees); determining the types of activities to be funded (e.g. new construction, renovation, purchase of existing dwellings, etc.); and ensuring key management and monitoring functions. The fund could be initially funded through any re‑adjustment of the property tax and resources that could be redirected from other housing support programmes. These funds could be complemented by commercial and/or concessional loans.

1.4. An integrated policy package, with priorities for the short and longer term

The proposed set of recommendations for the Lithuanian authorities are intended as a comprehensive policy package focusing on both targeted measures to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of existing support schemes and policies, as well as more broad-based efforts to address key structural challenges in the housing market. Some recommendations could generate results relatively quickly, while others will take more time to develop. For instance, one priority for the short term could focus on evaluating and improving the effectiveness of existing housing support (such as the rent compensation scheme and the financial support measures for young families). In light of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and its associated effects, including the issue of housing Ukrainian refugees and the cost-of-living crisis, it will be especially important to assess whether existing support schemes are reaching and supporting low-income and vulnerable households who are most in need. Another short-term area for attention would be to implement measures to incentivise the formalisation of residential rental agreements, which could improve the viability and effectiveness of support schemes that rely on a more robust, formalised rental market (e.g. the long-term rental sublease scheme). This includes reviewing existing tenancy regulations to ensure a balance between landlords and tenants, and broadening data collection on tenancy agreements, to provide more up-to-date information on the rental market.

In parallel, the Lithuanian authorities could begin to think about potential mechanisms to expand the supply of affordable and social housing through increased investment. Such mechanisms can be set up relatively quickly (the experience of the Latvian Housing Affordability Fund is a useful example), even if building up the financial capacity and adding to the supply will take more time. In parallel, efforts to strengthen technical capacity at municipal level will be essential, given their important (and potentially increasing) role as implementers in housing policy. These efforts would complement the recent reforms to strengthen the fiscal capacity of municipalities, which are a welcome development.

References

[16] Blöchliger, H. and R. Tusz (2020), “Regional development in Lithuania: A tale of two economies”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1650, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5d6e3010-en.

[3] Bulman, T. and H. Blake (2022), Surging energy prices are hitting everyone, but which households are more exposed? – ECOSCOPE, https://oecdecoscope.blog/2022/05/10/surging-energy-prices-are-hitting-everyone-but-which-households-are-more-exposed/ (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[6] European Commission; European Investment Bank (2020), The potential for investment in energy efficiency through financial instruments in the European Union, European Commission/European Investment Bank, https://www.fi-compass.eu/sites/default/files/publications/The%20potential%20for%20investment%20in%20energy%20efficiency%20through%20financial%20instruments%20in%20the%20European%20Union_0.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2022).

[12] European Mortgage Federation (EMF) (2022), Hypostat 2022: A Review of European Mortgage and Housing Markets, European Mortgage Federation (EMF), https://hypo.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2022/09/HYPOSTAT-2022-FOR-DISTRIBUTION.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[7] Eurostat (2021), Statistics: Electricity prices for household consumers - bi-annual data, Eurostat Data Browser, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/NRG_PC_204__custom_2023198/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 3 February 2022).

[18] Gabnytė, V. and T. Vencius (2020), Policy Note: Cash Social Assistance Benefit Non-take-up in Lithuania, Ministry of Social Security and Labour, Lithuania, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2015/social-policies/access-to-social-benefits- (accessed on 20 December 2022).

[5] Government of the Republic of Lithuania (2021), Long-term Renovation Strategy of Lithuania, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/default/files/lt_2020_ltrs_en.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2021).

[10] Lithuania Statistical Office (2022), Official Statistics Portal: Construction cost indicies, https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?indicator=S7R261#/ (accessed on 26 January 2023).

[14] OECD (2023), Elderly population (indicator), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8d805ea1-en (accessed on 26 January 2023).

[13] OECD (2023), Historical population, OECD, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=HISTPOP# (accessed on 26 January 2023).

[15] OECD (2023), Regional demography, OECD, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/BrandedView.aspx?oecd_bv_id=region-data-en&doi=a8f15243-en (accessed on 26 January 2023).

[4] OECD (2022), Affordable Housing Database, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

[20] OECD (2022), Government at a Glance - yearly updates, OECD, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=GOV (accessed on 8 July 2022).

[1] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f6da2159-en.

[8] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Surveys: Lithuania 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0829329f-en (accessed on 20 December 2022).

[2] OECD (2022), OECD Employment Outlook 2022: Building Back More Inclusive Labour Markets, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1bb305a6-en (accessed on 14 November 2022).

[17] OECD (2022), OECD tax-benefit database for Lithuania: Description of policy rules for Lithuania 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/TaxBEN-Lithuania-2022.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[9] OECD (2022), Prices: Analytical house price indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cbcc2905-en (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[19] OECD (2021), Brick by Brick: Building Better Housing Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b453b043-en.

[21] OECD (2021), Revenue Statistics 2021: The Initial Impact of COVID-19 on OECD Tax Revenues, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6e87f932-en.

[11] OECD (2020), Policy Actions for Affordable Housing in Latvia, OECD, Paris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=137_137572-i6cxds8act&title=Policy-Actions-for-Affordable-Housing-in-Latvia (accessed on 2 July 2020).