This chapter assesses the current housing policy framework in Lithuania, evaluating the housing support schemes in place to i) improve housing quality and energy efficiency; ii) provide housing support to low-income and vulnerable households; iii) help young households purchase their first home; and iv) formalise the private rental market. It provides a series of recommended policy directions in each area to support policy makers in facilitating access to quality housing at an affordable price, in an increasingly challenging policy context.

Policy Actions for Affordable Housing in Lithuania

3. Policies for quality housing at an affordable price in Lithuania

Abstract

3.1. Introduction and main findings

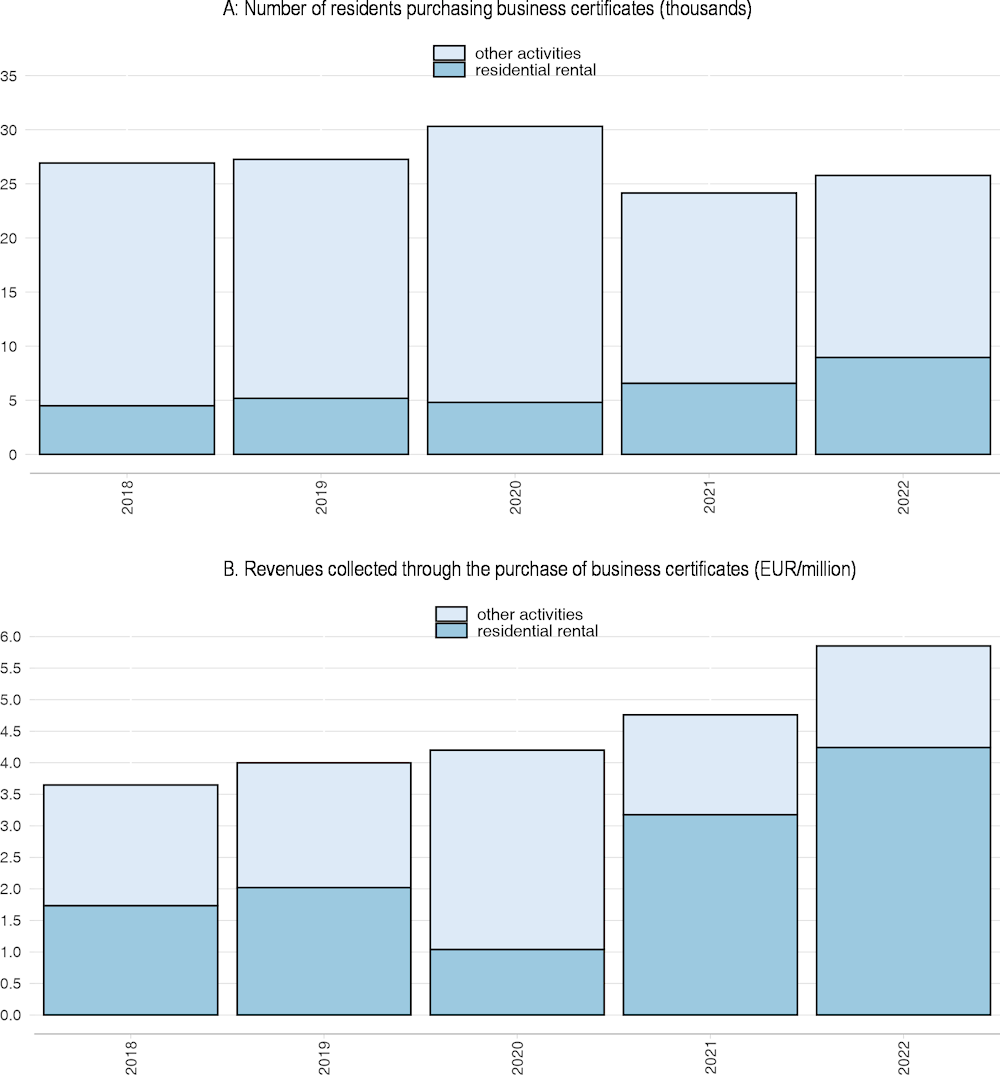

In recent years, Lithuania has made efforts to improve housing quality and make housing more affordable to low-income households and young people. For instance, since the mid‑1990s, programmes and partnerships with financial institutions have aimed to improve the quality and energy efficiency of the housing stock. Several housing support schemes have become increasingly targeted, and new schemes have been introduced, including a housing benefit scheme to support low-income tenants in 2015. Together, these have helped to channel public support to households at higher risk of poverty and in greatest need of support. Policy makers have also introduced measures to formalise the private rental market, notably through the introduction of business certificates for small retail investors in the rental market, which represent a more efficient and financially advantageous alternative to formally lease a property and declare rental income for tax purposes.

Nevertheless, much remains to be done. Among the priorities that could be considered by policy makers:

Accelerating the pace of improvements to the quality and energy efficiency of the housing stock;

Strengthening housing support for low-income and vulnerable households;

Re‑evaluating housing support schemes to help young people access home ownership by assessing whether such measures are the most effective use of government resources; and

Considering fiscal and regulatory reforms to help bring the private rental market out of the shadows, thereby providing more robust alternatives to home ownership in a housing market that remains heavily dominated by owner-occupied housing.

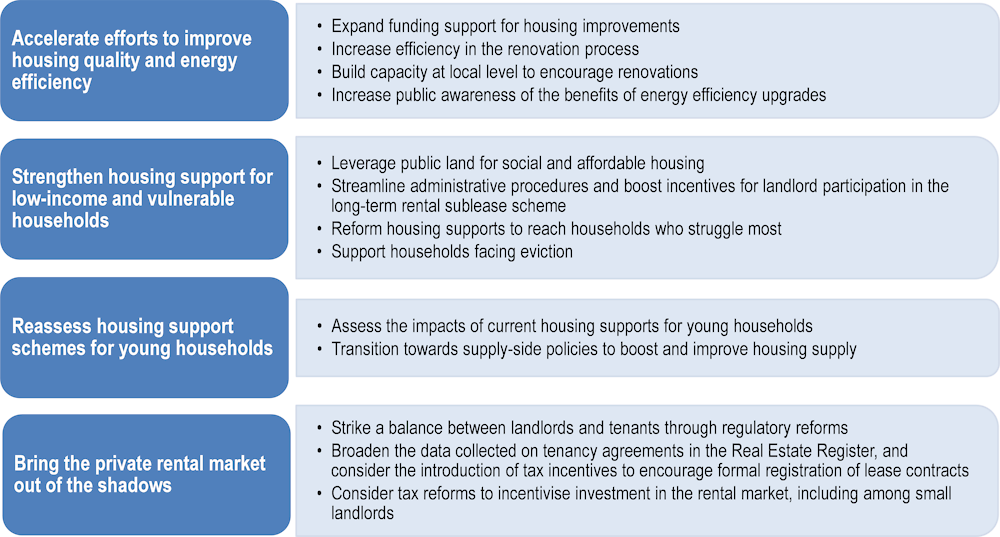

This chapter is organised into four sections, each reflecting a key priority in Lithuania’s current housing policy agenda. Section 3.1 focuses on policies to improve housing quality and energy efficiency. Section 3.2 addresses housing support schemes for low-income and vulnerable households. Section 3.3 focuses on housing supports for young families. Section 3.4 addresses measures to further formalise the private rental market. Each section begins with an assessment of the current policy framework, outlines recent advances and remaining challenges, and concludes with a series of recommended policy directions. The core recommendations for Lithuanian policy makers to deliver quality housing at an affordable price are summarised in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1. Key recommendations to deliver quality housing at an affordable price in Lithuania

3.2. Accelerating efforts to improve housing quality and energy efficiency

Improving the quality and energy efficiency of the existing housing stock is one of the most significant housing challenges for Lithuanian policy makers, as is the case across most OECD countries (Box 3.1). The main form of public support in Lithuania consists of financial incentives for households to upgrade flats in multi‑apartment buildings, with a subsidy or loan covering part of renovation costs for all households, regardless of income, along with a subsidy covering total renovations costs for low-income households who already qualify for the heating allowance (Heating cost subsidy programme, Būsto šildymo, geriamojo ir karšto vandens išlaidų kompensacijos).1 Nevertheless, despite longstanding public support schemes for residential renovations, the pace of renovations remains far too slow, and considerable gaps in housing quality persist.

Box 3.1. Renovating the existing building stock is a pressing need in most OECD countries

Buildings account for about 28% of total global energy consumption and, including emissions from construction and materials, nearly 40% of global energy-related carbon emissions (Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction and United Nations Environment Programme, 2021[1]; International Energy Agency (IEA), 2021[2]). Retrofitting and renovating the existing housing stock is the key means to decarbonise buildings in most OECD countries, and can also generate lead to gains in health and energy affordability (OECD, 2022[3]). Moreover, from a distributional point of view, policy supports to retrofit residential buildings tend to be progressive (Bourgeois, Giraudet and Quirion, 2021[4]).

The European Commission has identified improving housing quality and energy efficiency as a priority area of action and has launched the Renovation Wave initiative. This initiative aims to double annual rates of renovations and energy efficiency upgrades by 2030, to renovate 35 million building units, and aims to use public funding to create 160 000 green jobs that will help reach these goals (European Commission, 2020[5]).

3.2.1. Existing support schemes: Financial incentives to upgrade multi-family apartment buildings

Since the mid‑1990s, various programmes have been implemented to support renovations and energy-efficiency upgrades to the housing stock. Funding for such schemes has varied over time,2 with numerous adjustments to the successive support schemes implemented with the aim of accelerating renovations.

Subsidised loans and subsidies to cover a share of renovation costs of owners in multi-family apartment buildings to pursue energy efficiency renovations

The Ministry of Environment, in co‑operation with the Ministry of Social Security and Labour, operates several support schemes that provide financial incentives to homeowners to undertake renovation projects to improve housing quality and energy efficiency, described in the Law on State Support for the Renovation of Multi‑apartment Buildings. The Multi-Apartment Building Modernisation programme (MABM) constitutes the longest running and largest investment into renovation of housing in Lithuania. Since its inception in 2005, successive iterations of this programme have provided subsidised loans for renovation work on multi‑apartment buildings that have three or more stories and were built before 1993. The bulk of renovation efforts have concentrated on multi‑apartment buildings, which make up nearly 60% of the occupied residential stock, with three‑quarters of such buildings having been attributed a “D” or lower grade in terms of energy efficiency. Around 90% of multi-family dwellings were built before 1993 and are energy inefficient, consuming around twice as much energy relative to multi-family buildings constructed after 1993 (Aukščiausioji Audito Institucija, 2020[6]) (Chapter 2).

The current programme aims to provide funding for the renovation of 5 000 multi‑apartment buildings by 2030, around 500 apartment buildings per year (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[7]). Homeowners are eligible for a mix of loans at favourable rates and subsidies that amount to 30% of total renovation costs. There are no income limits to either the lending or subsidy components of the renovation programme. Renovations must increase energy efficiency substantially, as the objective of the programme is to ensure that heating costs after the renovation do not exceed the heating costs paid by households before the renovation, factoring in also the costs related to the loan payments (Lithuanian Environmental Project Management Agency, 2022[8]). In this way, the project aims to foster deep, comprehensive renovation efforts, including insulation of outer walls, replacement of windows and heating systems, and the repair of roofs (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[9]). This programme is financed through two preferential loan funds: the Multi‑apartment Building Modernisation Fund (DNMF), managed by the Public Investment Development Agency (VIPA), and the Jessica II Fund, managed by the European Investment Bank (EIB) (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[7]).

In addition to financial support provided through the MABM programme, a number of initiatives have been developed, including efforts to facilitate the decision-making process among homeowners in large multi‑apartment buildings, where a majority of residents must approve the renovation plans, and to further develop competencies of municipalities to manage the complex, technical process of largescale renovations.

Subsidies to cover renovation costs for low-income owners in multi-family apartment buildings

Under the MABM programme, low-income owners may apply for public support to cover renovation costs, and receive a full cost subsidy in lieu of the standard rate of 30%. To qualify, households must already be eligible for the compensation for heating, drinking water and hot water costs (Box 3.2). A recent reform of the Law on Cash Social Assistance for Poor Residents of 2003 has helped to accelerate the pace of renovations among low-income households. The amended law includes the provision that recipients of the heating cost compensation must agree to proposed renovation projects for their building; failure to do so means that they lose their heating cost compensation.

Box 3.2.Lithuania’s compensation for heating, drinking water and hot water costs

The heating compensation (Būsto šildymo, geriamojo ir karšto vandens išlaidų kompensacijos) is means-tested support to cover expenses for heating, drinking and hot water. It should be noted that the compensation does not cover electricity costs, which can amount to over EUR 100 per month (Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania, 2022[10]).

This support scheme is administered by municipalities, according to the eligibility requirements set out by the national government. Eligibility conditions are the same as for the Social Benefit (Socialinė pašalpa) and consist of a means-test and compliance with various other employment and family responsibilities (see OECD Tax-Benefit Database for further information). Generally, eligibility is based on income thresholds as well as limits on the value of any owned property, whereby the value of the property cannot exceed the average property value set for the family’s residential area. However, temporarily (through 30 April 2024), the property criteria is excluded from the eligibility determination. Effective as of 1 January 2022, the allowance consists of a heating cost compensation that caps a household’s (family’s) monthly energy expenses at 10% of the difference between the family income and 2 times the state‑supported income (SSI) provided to each member of the family; and 10% of the difference between an individual’s income and 3 times the state‑supported income (SSI) for individuals.

In 2021, such benefits amounted to approximately EUR 19.84 million, serving 100 500 persons, or just under EUR 200 per person per year on average – up from EUR 13.15 million for 93 700 people in 2020 (OECD, 2021[11]) The benefit is delivered directly to the utility providers, unless the household does not have central heating (in which case they receive the benefit amount directly).

As outlined in Chapter 1, energy poverty is likely to remain at the forefront of policy makers’ concerns. Energy prices in Lithuania have been on the rise in recent decades, and at much faster rates than the EU average. In September 2022, Lithuania recorded the fourth-highest annual growth rate in energy prices, at 75%, behind Türkiye (146%), the Netherlands (114%) and Estonia (78%) (OECD, 2022[12]). Indeed, demand for the programme has continued to grow: in the first half of 2022, over 150 000 people benefitted from the compensation scheme, amounting to around EUR 29 million (Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania, 2022[10]).

3.2.2. Recent advances and remaining challenges

Lithuania’s sustained efforts to improve housing quality and the energy efficiency of the housing stock through successive government programmes since the 1990s should be commended. An average of roughly 340 renovations have been completed annually between 2013 and 2020, and a peak of 769 multi-family buildings renovated in 2016 (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[7]). Another positive development is that housing support schemes for renovation have become increasingly targeted, which helps to improve the allocation of scarce public resources to households in greater need and make some headway in reducing energy poverty.

Yet despite progress, the pace of renovations remains sluggish, and significant housing quality gaps persist. As of 2020, only 8% of the 37 136 multi‑apartment buildings built before 1993 had been renovated. The National Audit Office reports that at the current pace, it would take roughly 100 years to modernise the most energy-intensive multi-family apartment buildings in the country. Moreover, rural homeowners have been largely excluded from renovation efforts, which have focused on multi‑apartment buildings in urban areas. This results in considerable gaps in housing quality between urban and rural areas. The urban-rural gap is compounded by the fact that current homeowners – even those with a low income and poor quality housing – are in many cases ineligible for social housing.3 This means that rural homeowners are ineligible for public support to improve their dwelling.

3.2.3. Recommended policy directions

To speed up progress towards its energy efficiency objectives and make greater headway in reducing energy poverty, Lithuanian policy makers could pursue several opportunities to accelerate the pace of building renovations. This includes i) expanding funding support for residential modernisation schemes to meet rising demand; ii) making the renovation process more efficient; iii) strengthening municipal capacity for renovations through dedicated municipal companies; and iv) increasing public support and awareness of the benefits of energy efficiency upgrades.

Expand funding support for housing improvements

Boosting funding support for housing improvements should be a top priority for Lithuania. Current demand for renovations under the MABM programme cannot be met with existing funds. In September 2022, year-on-year growth in construction costs increased by 19%, more than double the growth from the same period of the previous year (Lithuania Statistical Office, 2022[13]). Moreover, the significant surge in energy prices since the second half of 2021 has generated increased demand for the heating cost subsidy and provided even further momentum to improve the energy efficiency of the residential sector. The Ministry of Environment reported that project applications received from the first round of renovation applications in 2022 already exceed the currently allocated budget for the programme.

Over the long term, these building fiscal pressures will only be mitigated by improving the energy efficiency of buildings, which calls for ramping up the current pace of renovations. Indeed, the goal of renovating 5 000 multi‑apartment buildings by 2030, as set out in Lithuania’s Long-term Renovation Strategy, would yield a total of 22% of the target buildings (e.g. multi‑apartment buildings built before 1993) renovated over the next few years. By increasing funding for renovations, the government could potentially scale up existing targets to increase energy savings further.

One option to increase funding support over the long term could be to establish a dedicated housing fund. Housing funds exist in many OECD countries, and can take different forms. Denmark, Slovenia and the Slovak Republic have developed a single‑purpose housing fund, in different stages of maturity; Latvia is currently establishing such as fund to support the development of new affordable rental housing. Chapter 4 provides an in-depth discussion of funding models, along with detailed country examples.

Increase efficiency in the renovation process

At the same time, increasing efficiency in the renovation process would also help accelerate building renovations. This is because deep energy efficiency renovations tend to require co‑ordination across many contractors who specialise in different parts of the renovation process on the building site; delays at any step lead to extra costs. Several countries, including Latvia and Estonia, are piloting the use of prefabricated multifunctional renovation elements to speed up the renovation process (Box 3.3). This approach has the potential to expedite deep renovations and reduce the disturbance for occupants who live in the dwellings, making renovations more attractive for owners. Similarly, the Netherlands has introduced a programme that improves the co‑ordination of different steps in the renovation process, thus reducing the total renovation time for net-zero renovations of social housing to 10 days (Box 3.4).

Box 3.3. Increasing efficiency of deep residential renovations: the MORE‑CONNECT pilots in Estonia and Latvia

Estonia and Latvia have developed pilot projects to test more efficient ways to undertake deep residential renovation by using prefabricated multifunctional renovation elements. This pilot is part of the development of the integrated design of nearly Zero Energy Buildings (nZEB), funded by the European Union’s H2020 framework programme for research and innovation. Projects generally include thermal insulation, high-performance window installation, insulation of the roof, mechanical ventilation, a heat pump for hot water use and heating, and photovoltaic panels for electricity generation. The pilot assessed whether modular renovation could increase the energy efficiency of dwellings, while simultaneously reducing costs, renovation time and disturbance for dwelling occupants (European Commission, 2019[14]).

Estonia and Latvia share strong similarities with Lithuania in terms of the history, quality and building typologies of the housing stock.

A pilot project in Estonia modernised a typical five‑story multi‑apartment building with prefabricated large concrete panel elements in Tallinn. The building represents a common form of housing constructed in urban areas between the1960‑1990s across the Baltics, making it an especially relevant case for Lithuania, considering the stock of over 37 000 multi‑apartment buildings built before 1993.

A pilot project in Latvia consisted of the deep renovation of a silicate brick building built in 1967, and commonly constructed in the 1950‑1960s in rural areas and smaller cities across Latvia and the Baltics.

Initial findings suggest that modular renovations can provide an efficient alternative to traditional deep renovation in both urban and rural areas. Using prefabricated renovation elements offers a one‑stop-shop solution for production and a single point of contact for end-users. Apartment owners can rely on one party who is responsible for all stages of the renovation, from initial planning, inventory of specific demands, adherence to building codes, translation into modular renovation kits, installation of the modules, to financing and aftercare. Over time, the goal is to carry out the entire renovation process on-site in a maximum of 5 days. Nevertheless, further optimisation in the production and installation process of prefabricated modules is needed.

Source: (European Commission, 2019[14]), MORE-CONNECT: Development and advanced prefabrication of innovative, multifunctional building envelope elements for Modular Retrofitting and smart Connections, https://www.more-connect.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/MORE-CONNECT-WP1_D1.7-Final-publishable-report.pdf.

Box 3.4. Completing net-zero energy renovations in 10 days: The Energiesprong programme

The Netherlands designed the Energiesprong programme, which consolidates all steps of the renovation process to complete net-zero energy renovations of social housing in 10 days. The programme aims to foster private investment by enlarging the market size and enabling increased use of low-cost technologies like prefabricated facades (also tested in Estonia and Latvia; see Box 3.3), smart heating and ventilation systems, as well as insulated roofs with solar panels (OECD, 2022[3]). The strength of the programme is the fact that it brings together stakeholders such as housing authorities, the construction industry, banks and utility companies to discuss and plan projects more efficiently. Though the programme is currently still dependant on public subsidies, it aims to become financially self-sufficient after its pilot phase (Visscher, 2020[15]). The approach has been adopted in other OECD countries, including France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States (states of California and New York).

Source: (OECD, 2022[3]; Visscher, 2020[15]), “Decarbonising Buildings in Cities and Regions”, https://doi.org/10.1787/a48ce566-en.

Build capacity at local level to encourage renovations, including through dedicated municipal enterprises

There is a need to further develop capacity within municipal administrations to facilitate building renovations, given the key role of local authorities in the building management and renovation process. The most recent estimates suggest that 80% of multi‑apartment buildings are managed by municipally-appointed administrators, around 17% by a homeowners’ association (HOA), and 3% by a joint activity agreement (JAA) between apartment owners. In most cases, administrators are municipal housing maintenance companies (Sirvydis, 2014[16]).

The co‑ordination of all owners of a multi‑apartment building to agree to undertake renovations poses significant challenges. Administrators appointed by the municipalities are tasked with three separate, but interconnected tasks in the renovation process: i) informing and encouraging apartment owners about renovations and government support programmes; ii) managing the administrative burden as well as the renovation processes; and iii) in some cases, functioning as borrowers of renovation loans in lieu of apartment owners. However, owners in multi‑apartment buildings often have varying financial means, energy usage behaviour and preferences on the development of the building, which together make it difficult to take a joint decision on renovations for energy efficiency (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[7]). Moreover, administrators do not always possess the necessary mix of competencies to manage the complex administrative process involved. The approach of the municipality of Vilnius, which represents an integrated approach that encompasses renovations as part of larger neighbourhood development efforts, could be replicated elsewhere in Lithuania (Box 3.5).

Box 3.5. Renew the City: Vilnius’ public institution to implement urban regeneration projects, including energy efficiency upgrades

The public institution Renew the City (Atnaujinkime miestą) was established by the municipality in 2007 to implement urban regeneration projects throughout the city. It disseminates information, offers consultations, manages apartment renovation projects and implements neighbourhood programmes to improve quality of life. This more centralised and holistic approach has shown signs of being more effective than individual administrators in convincing apartment owners to undertake renovations of multi‑apartment buildings.

To date, Renew the City has conducted more than 120 renovation projects of apartment buildings. This programme could serve as an example across Lithuania and help build capacity at the local level to boost renovations and urban renewal.

Increase public awareness of the potential benefits of energy efficiency upgrades

Enhancing public awareness about the benefits of energy efficiency upgrades to save costs and increase quality of living are vital to accelerate the pace of renovations. Latvia’s “Let’s live warmer!” (Dzīvo siltāk!) programme is an example of a successful public awareness campaign to foster energy efficiency upgrades is. Similar to Lithuania, Latvia’s policy priority lies in the improvement of multi‑apartment residential buildings. A number of activities, ranging from seminars, workshops, public discussions and publications on national, regional and local level aim to inform citizens about benefits and processes to carry out renovation projects (Ministry of Economics of the Republic of Latvia, 2020[17]). The public awareness programme has contributed to increasing the number of submitted renovation applications: applications for the Improvement of Heat Insulation of Multi-Apartment Residential Buildings programme quadrupled between 2009 (before the public awareness programme began) and 2011 (Ministry of Economics of the Republic of Latvia, 2020[17]). The rapid and significant rise in energy costs since 2021 may also provide a favourable context to encourage households to undertake renovations.

3.3. Strengthening housing support for low-income and vulnerable tenants

The provision of social housing and direct financial assistance to households are the main forms of support to make housing more affordable to low-income and vulnerable tenant households. Nevertheless, the demand for such supports far exceeds the supply, and important challenges in the design and implementation of the government’s primary two support schemes persist. The supply of social housing is far too small to meet demand, and efforts to supplement the social housing supply through the private rental market have not substantially increased the stock of social housing. Moreover, a strong stigma is attached to social housing residents, limiting interest from private landlords to lease rental units to social tenants and complicating efforts to expand the supply.

3.3.1. Existing support schemes: Social housing and cash benefits to cover housing costs

Two types of housing support are available to low-income and vulnerable tenants: direct financial support to cover housing-related costs, namely through the rental compensation and energy compensation schemes, and in-kind support, such as social rental housing and the associated scheme to lease private rental housing to households that qualify for social housing. Both types of programmes are means-tested.

Direct financial support to cover housing-related costs: Rent and energy compensation schemes

Introduced in 2015 under the Law on Support for the Acquisition or Rental of Housing, the partial reimbursement of rental housing costs (Būsto nuomos mokesčio dalies kompensacija) is a housing allowance allocated by municipalities to tenants who meet the income and asset tests and have a formal registered minimum one‑year lease for a dwelling in the private rental stock.4 The amount of the housing benefit is determined based on the location of the dwelling, as well as household size and composition. Local authorities assess households’ eligibility for the housing benefit scheme and administer the programme, according to the eligibility criteria established by the central government. Currently, funding for the housing benefit comes from the State budget, with some additional top-off support provided by municipalities in some places (especially in Vilnius).

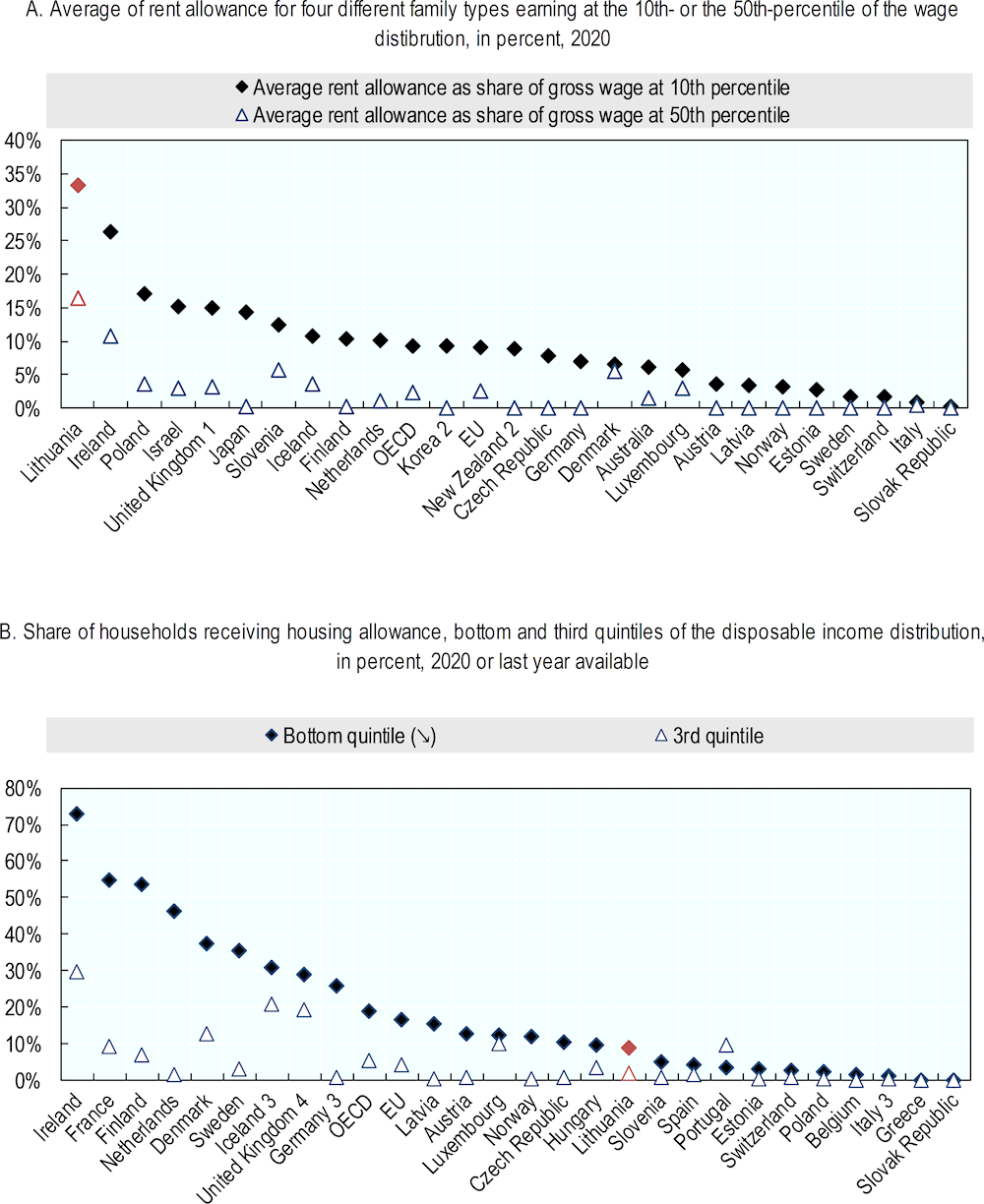

Take‑up rates for the housing benefit scheme have progressively increased since its introduction, though they remain very low overall. In 2021, around 3 725 individuals received the housing benefit (less than 1% of the total population), and an even larger amount registered in the first half of 2022. While the benefit is among the most generous housing allowances in the OECD, it is very limited in its reach (Figure 3.2) (OECD, 2022[18]). One factor in its limited reach is likely because eligibility requires the registration of a formal rental contract of at least one year in the Real Estate Register which is administered by the State Enterprise Centre of Registers (SECR), along with other income‑related eligibility criteria for the tenants (OECD, 2022[19]). Other explanations for the limited reach include the relatively recent introduction of the scheme (2015), as well as the persistent stigma associated with recipients of social assistance and the continued importance of the shadow economy in Lithuania (which may make households hesitant to apply for fear of income checks) (Gabnytė and Vencius, 2020[20]).

In addition, low-income households (families) that meet the eligibility conditions of the Law on Cash Social Assistance for Poor Residents of 2003 are eligible to receive an allowance to cover heating, drinking water and hot water costs (Būsto šildymo išlaidu, geriamojo vandens išlaidu ir karšto vandens išlaidu kompensacijos). The reach of the monthly heating allowance is much broader than the housing benefit scheme; demand for support through the scheme has further increased in recent months following the dramatic increase in energy prices (see Box 3.2). To be eligible, households (who may be homeowners or renters) must meet an income‑test5 and fall into one of a number of social situations (e.g. reduced working capacity, registered as unemployed, taking care of a family member, pregnant, a parent raising a young child not in school, etc.) (OECD, 2022[19]).

Figure 3.2. Lithuania has the most generous housing benefit scheme in the OECD – but its reach is very limited

Notes: Panel A: Rent allowance calculated based on assumed rent of 20% of average wage. Only shows central government housing allowance. Where no national scheme exists, a representative region was chosen, refer to country specific information for more details: http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/benefits-and-wages-country-specific-information.htm. Full-time earnings are either at the 10th or the 50th percentile of the full-time wage distribution. No transitional benefits for entering the labour market are considered; social assistance but no unemployment benefits are considered. The four family types considered are (1) single person, (2) single parent with two children aged 4 and 6, (3) one‑earner couple and (4) one‑earner couple with two children aged 4 and 6. Earnings are either at the 10th- or the 50th percentile of the full-time wage distribution. Panel B: No information available for Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Republic of Türkiye and the United States due to data limitations. Only estimates for 100 or more data points are shown. Quintiles are based on the equivalised disposable income distribution. Low-income households are households in the bottom quintile of the net income distribution.

1. Panel A: The present publication presents time series which extend beyond the date of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union on 1 February 2020. In order to maintain consistency over time, the “European Union” aggregate presented here excludes the UK for the entire time series.

2. Panel A: Data for New Zealand are preliminary and data for Korea refer to 2018.

3. Panel B: Data for Germany and Italy refer to 2019 and for Iceland to 2018.

4. Panel B: In the United Kingdom, net income is not adjusted for local council taxes and housing benefits due to data limitations.

Source: (OECD, 2022[18]), Affordable Housing Database – OECD, indicator PH3.3, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

Social housing

The provision of social housing represents an important form of housing support for very low-income and vulnerable households, yet demand far exceeds supply. Representing less than 1% of the total housing supply, Lithuania’s social housing sector remains extremely small and suffers from significant quality gaps (Chapter 2). Spending on social housing in Lithuania was a tenth of the EU-average in 2019, at around EUR 10 per inhabitant compared to around EUR 101 per inhabitant in the EU (European Commission, 2022[21]). Lithuania lacks an overall strategy to address “chronic shortages” of the social housing stock and to increase its quality (European Commission, 2022[21]). In 2020, the waiting list for social housing amounted to around 10 000 households nationally (around 22 000 people) (European Commission, 2022[21]). Eligibility conditions for social housing, which are based on income and asset means-testing, are established by the central government (Ministry of Social Security and Labour, MSSL) and set out in the Law on Support for Acquisition or Rental of Housing. Municipal authorities manage both existing and prospective social housing tenants, determining tenants’ eligibility for social housing, allocating the stock and managing the waiting list. They also monitor tenants’ continued eligibility for social housing, based on annual income and asset testing, following the households’ declaration submitted to the State Tax Inspectorate and the information provided in the property registry.6

In addition to managing the entry and through fare of social housing tenants, local authorities are also responsible for the operation, management, maintenance and development of the social housing stock. This includes maintenance responsibilities, in addition to efforts to increase the supply. Approaches differ across municipalities, but generally involve either developing new social housing or purchasing (and in some cases, upgrading) existing dwellings from the private stock to convert to social dwellings. Around 85% of funding comes from the EU, with a maximum co-financing contribution of 15% from municipalities; in past years, the State had contributed around 65% of the programme funding.

Municipal housing – which, as its name implies, is owned and managed by municipalities – is another potential avenue to (modestly) increase the supply of social housing. Unlike social housing, which is allocated via income eligibility requirements, such income criteria have not generally applied to the allocation of municipal housing. Municipal housing accounts for the majority of the public rental housing stock owned by local authorities (which includes both municipal and social housing), which nevertheless together represent a small fraction of Lithuania’s overall housing stock (Chapter 2). Municipal units can be leased for up to one year to households that qualify for social housing; new regulatory amendments that came into force in January 2022 encourage municipalities to prioritise vulnerable groups in the allocation of municipal housing (see Box 3.5). In addition, the management of the municipal housing stock contributes indirectly to the social housing supply, given that the proceeds from the sale of municipal housing must be reinvested in social housing.

Prior to 2019, rents for municipal housing were set according to a similar formula as for social housing; however, this requirement has since been lifted, and municipalities must set rents at market-rate, with a series of exceptions permitted for certain groups. Typically, tenants in municipal housing have fixed-term contracts and are not required to meet the income and asset eligibility test required of social housing tenants, nor do they need to declare their income levels. However, in a promising development that could be replicated in other municipalities, in 2021 the municipality of Vilnius began to request household income data from municipal housing residents, with the aim to better understand the profile of municipal tenants, and, over the medium term, potentially making more efficient use of the municipal housing stock for low-income and socially vulnerable populations. In parallel, efforts to increase the quality of the municipal housing stock could be undertaken.

The long-term rental sublease scheme

In an effort to expand the supply of affordable and social rental housing, the government introduced in 2019 a long-term rental sublease scheme (Būstų nuoma ne trumpesniam kaip 5 metų laikotarpiui iš fizinių ar juridinių asmenų), whereby landlords lease their private rental dwellings to municipalities for use by tenants who qualify for social housing. The minimum rental tenure is for five years (compared to the standard one‑year rental contracts), with the rent paid directly to landlords by municipalities, with the cost of rent covered by the State budget, tenant payments, and the municipal budget. The programme aims to provide low-income tenants with a more secure, affordable tenure, and to offer property owners a rental contract for up to five years, with payment guaranteed by the municipality. However, the programme has struggled to overcome the shortage of adequate and affordable rental dwellings in the market, as well as a lack of interest on the part of landlords to lease their dwellings to social housing tenants. The incentives appear thus far insufficient to attract a significant number of landlords to participate in the scheme, and the application procedure creates an additional burden for property owners in requiring, for instance, that landlords conduct an external assessment of the value of the property. The persistent stigma associated with social housing residents is likely another factor that discourages participation from landlords.

Persistent stigma associated with social housing residents contributes to supply shortage

A strong stigma affects residents of social housing in Lithuania, as social norms perpetuate negative perceptions of social tenants. In a number of Lithuanian municipalities (notably the Trakai, Lazdijai, Širvintos, Kėdainiai and Akmenė districts), more than 60% of residents disapprove of having social housing apartments in their apartment blocks (Lapienytė, 2018[22]).

A number of factors may contribute to the stigmatisation of social housing tenants. First, eligibility criteria that primarily reserve social housing for households with acute needs, therefore limiting socio‑economic diversity among residents. On the one hand, targeting social housing to the most vulnerable households, including those in the bottom segment of the income distribution, can help to ensure that, in a context of constrained resources, social housing is allocated to households in greatest need. On the other hand, the resulting concentration of low-income and vulnerable households can generate “social and economic ghettoes by policy design” (Poggio and Whitehead, 2017[23]). Further, regulations permit residents to remain in social housing as long as they meet the eligibility requirements. In practice, this may mean that those with choice exit the tenure, leaving social housing buildings with only those with fewest resources and opportunities. The more policies seek to encourage pathways out of poor neighbourhoods, the greater the stigma experienced by those who remain in situ (Wassenberg, 2004[24]). At the same time, the number of evictions from social housing in Lithuania is also increasing, which might be reinforcing the poor reputation of social housing.

Second, the quality and location of many social housing developments is another factor contributing to stigma. The stock suffers from significant quality gaps and insufficient maintenance, which in turn cast a negative image of residents, especially through media reporting on poor housing conditions. Further, social housing tends to be geographically concentrated, often in remote areas (Mikutavičienė, 2018[25]). Its distance from city centres and workplaces and poor connection to public transport can exacerbate social exclusion and stigmatisation.

Third, the phenomenon known as NIMBYism (“Not in my backyard”) – that is, the perception that social dwellings could decrease home values and neighbourhood attractiveness – could be another contributing factor, along with a wider stigmatisation of poverty.

The stigmatisation of social housing has a broader impact on the housing market. As discussed, it generates negative consequences on landlords’ willingness to rent dwellings to municipalities for social purposes. As a result, this limits the potential contribution of the private housing stock towards the social housing supply and fails to alleviate the problem of long waiting lists for social housing. Further, stigma may also affect developers’ willingness to develop new social housing.

3.3.2. Recent advances and remaining challenges

Several important advances in support to low-income and vulnerable tenant households have been introduced in recent years. For instance, the housing benefit scheme introduced in 2015 has helped to expand the menu of housing support schemes for tenants on the lower end of the income distribution. Subsequent reforms to the scheme in 2020 significantly increased the generosity of the benefit. Namely, the calculation to determine the benefit amount is now differentiated according to family size, and based on a larger floor area relative to the previous rules, resulting in a more generous benefit amount (OECD, 2022[19]). One key objective of the 2020 reforms was to make the housing benefit more attractive to single‑earner households, for whom housing costs represent a bigger relative financial burden compared to dual-earner households. Hence, the per person benefit allocated to single households is higher than that for families, even though the benefit for families remains more generous in absolute terms. An additional reform, adopted in December 2021, will transfer a portion of the financial responsibility of the housing benefit scheme from the State to municipalities in January 2024.

Efforts to expand the social housing stock have continued, through new construction and the acquisition and conversion of existing dwellings. This includes the long-term rental sublease scheme, in addition to a new law on territorial planning7 that grants a density bonus (the possibility to develop additional square metres than otherwise allowed) to construction projects that devote at least 10% of development to social housing. Further adjustments to the social and municipal housing schemes, which came into force on 1 January 2022 (with a few exceptions), facilitate the allocation of social housing to single‑parent families and new rules thus encouraging the allocation of municipal housing to households in greatest need; both are welcome developments (Box 3.6).

In addition, the government has introduced a number of measures to address the stigma associated with social tenants and to avoid the spatial concentration of social housing. In particular, the Minister of Social Security and Labour outlined guidelines such that when planning to build new housing or reconstruct and adapt existing buildings for housing purposes, no more than two‑thirds of the housing units in a residential building can be used as social housing. Proposed regulatory changes will also mandate that social tenants receive social services, which – provided that municipalities have the means to offer such services – could help raise the social stature of residents. Recent efforts by the Lithuanian Ministry of Finance and the Central Project Management Agency have brought together social housing residents with their neighbours who do not live in social housing, as part of the public awareness campaign, “I am your neighbour. Do not sort me,” funded by the EU’s European Social Fund. The campaign has been effective in increasing acceptance among municipal administrations to place social housing tenants in conventional apartment buildings, and in reducing the share of people who associate social housing residents with problematic or anti-social behaviour. Thanks to the project, the rate of municipal officials recognising the benefits of locating social housing in conventional apartment buildings increased from 48% to 62% (European Commission, 2021[26]). The initiative suggests that there is scope to use communication campaigns as a vehicle to subvert existing stereotypes.

Box 3.6. Recent legislative amendments to the law on housing support in Lithuania

A number of amendments to the Law on Support for Acquisition or Rental of Housing came into force on 1 January 2022, with provisions for both social and municipal housing.

Social housing:

Municipalities are authorised to prioritise single‑parent families in the allocation of social housing units;

The income and asset tests to be eligible for social housing were increased from 25% to 35% and 50%, depending on the target group, due to the higher risk of poverty of these groups;

Municipalities are obliged to provide social services (as of 1 January 2023), as well as support to receive the housing benefit, to households on the waiting list for social housing;

The income and asset tests to be eligible for social housing shall be lifted for a temporary period, in the event of a national emergency or quarantine (an amendment resulting from the COVID‑19 pandemic);

Municipalities are obliged to monitor the condition of social housing units, as well as the use of such units to ensure that the tenancy contract is respected (e.g. the lease holder is living in the dwelling, etc.);

In the event of a breach of contract by social housing tenants, municipalities have the obligation to organise social services and support the household to be evicted to find alternate suitable accommodation;

The prior requirement that households evicted from social housing must wait five years until they are again eligible for social housing has been eliminated.

Municipal housing:

The possibility to lease municipal housing units at below-market rate prices (not to exceed 20% beyond the price of a social housing unit) to households that meet certain characteristics (e.g. nearing retirement age, persons with disabilities, single‑parent families, families with three or more children, etc.); for all other cases not specified in the legislation, municipal housing should be leased at market rent;

Clearer rules in the allocation of municipal housing units were introduced, including facilitating the transition of households that are no longer eligible for social housing but meet certain characteristics (e.g. nearing retirement age, persons with disabilities, families with three or more children, etc.) to move into municipal housing;

Adjustments to the rules regarding the sale of municipal housing, including to enable purchase by rehabilitated political prisoners and other target groups.

Source: Information provided by the Lithuanian Ministry of Social Security and Labour, 2022.

3.3.3. Recommended policy directions

Despite these advances, housing support for low-income and vulnerable households continue to fall well short of need. A set of targeted policy actions could contribute to improve housing support, including i) leveraging public land for the development of social and affordable housing; ii) streamlining administrative procedures and boosting incentives for landlord participation in the long-term rental sublease scheme; iii) considering reforms to reach households who struggle most in the housing market, including potential adjustments to the housing benefit scheme to expand its reach; and iv) introducing measures to address some of the causes of eviction. These measures should be anchored in an ambitious strategic agenda for housing, coupled with significant efforts to boost investment in social and affordable housing (Chapter 4).

Pursue opportunities to leverage public land for social and affordable housing

In line with the recent changes to territorial planning regulations that incentivise developers to allocate a share of residential development to social and affordable housing, Lithuania could consider encouraging municipal authorities to leverage public land for the development of social and affordable housing. In Lithuania, municipalities already have the possibility under the existing legal framework to leverage State‑owned land for strategic purposes, but thus far have not exercised this right for social and affordable housing; in most cases, State‑owned land has been acquired by municipalities for commercial or industrial development.

The Lithuanian Government could consider shifting the financial incentive structure to encourage leveraging public land for housing, with a minimum share required to be allocated for social and/or affordable housing, as is common practice in many OECD countries. In Latvia, for instance, the city of Valmiera has developed 150 affordable rental units in multi‑apartment buildings on subsidised public land without expectations on returns on investments (OECD, 2020[27]). The reduced land costs enabled to offer apartments at roughly EUR 4/m2 below market value. Over time, such efforts to expand the supply would likely contribute to reducing pressures on demand-side supports, such as the housing benefit scheme while helping to expand the stock of affordable and social housing.

In Luxembourg, the Support for affordable housing construction scheme (Aide à la pierre – logements abordables), introduced in the Law of 25 February 1979 relating to housing support, along with the Housing Pact (Pacte logement), established in 2008, provides financial support to local governments and public and private developers to build housing that will be made available at a subsidised purchase or rental price. This includes financing of land acquisition, planning and construction of housing; prices of subsidised dwellings must be on average 20% below market prices and minimum energy efficiency standards must be met (OECD, 2022[18]). The Housing Pact takes the form of an agreement between the government and the local authority (noting that eligible municipalities must have recorded population growth of at least 15% over a 10‑year period), with the aim to increase the housing supply and reduce real estate costs (Gouvernment du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, n.d.[28]). The provisions of public support of the Housing Pact include:

financial support: EUR 4 500 per additional inhabitant above an annual population growth of 1% between 2007 and 2017, with the potential for additional funding depending on the locality; and

a series of implementation tools: these include, inter alia, the right of first refusal (whereby the government has the priority to acquire a property in the public interest, notably to develop affordable housing) as well as other administrative and fiscal tools (such as a vacancy tax that may be levied on properties that are unoccupied for more than 18 months) (Gouvernment du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, n.d.[28]).

At the same time, policy makers must also ensure the integration of social housing in the broader urban neighbourhood. Social housing is often developed far from job centres without easy access to public transport. Increased collaboration with the Ministry of Transport, for instance, could enhance connectivity of existing social housing dwellings. Improved urban design to better connect the area to the city’s core would help to integrate social housing residents and support their inclusion. This was an important lesson from the large‑scale renovation of Regent Park social housing estate in Toronto (Canada) (OECD, 2020[29]).

Streamline the administrative procedures and boost incentives for landlord participation in the long-term rental sublease scheme

There is also scope to reduce the administrative burden and boost incentives to encourage landlords to participate in the long-term rental sublease scheme. Easing administrative burdens and expanding financial incentives for landlords could be supplemented with a public information campaign about the possibility and benefits to rent out apartments for social purposes. Lithuanian policy makers may draw inspiration from practices in other OECD countries to incentivise landlords to participate in affordable and social housing schemes that draw on the existing housing stock. Incentivising the use of the existing stock is of particular relevance in Lithuania, in light of a declining population and a less pressing need to develop new housing. Countries provide different types of incentives:

Under the Private Rented Sector leasing scheme in Wales (United Kingdom), local authorities can sub-lease residential properties from private landlords for a fixed duration of five years, and take responsibility for managing the tenancy; in return, landlords can receive a grant (up to GBP 2000) or an interest-free loan (up to GBP 8 000) to bring the property up to a minimum quality standard, as well as ongoing tenancy support for the duration of the agreement (Box 3.7) (Welsh Government, 2021[30]).

The Private Rental Incentives programme in Tasmania (Australia) pays participating landlords an annual subsidy (which varies according to the size and location of the rented unit) to lease their properties at an affordable rent (Department of Communities Tasmania (Australia), n.d.[31]).

Ireland allows landlords to benefit from a more generous level of mortgage income tax relief if dwellings are leased for social purposes, relative to the relief provided to property owners who rent out properties at market rate (Clarke and Oxley, 2017[32]).

Australia, Flanders (Belgium), France and England (United Kingdom) have developed social rental agencies as intermediaries between low-income tenants and private landlords that are designed to reduce costs and risks to landlords; social rental agencies can have different functions (Box 3.8) (Clarke and Oxley, 2017[32]).

Box 3.7. The Private Rented Sector leasing scheme in Wales (United Kingdom)

Under the pilot phase of the Private Rented Sector leasing scheme in Wales (United Kingdom), between 2020 and 2027, six local authorities1 have the ability to sub-lease residential properties from private landlords for a fixed duration of up to five years.

The objectives of the scheme are to:

Improve access to affordable housing to low-income and vulnerable households, by reducing the risks perceived by potential landlords to lease their dwellings for a social purpose;

Provide longer-term security of tenure to vulnerable households;

Provide tailored support to help tenants maintain their tenancy (e.g. advice on independent living, money management);

Reduce stigma and discrimination among low-income and vulnerable tenants, including by reducing the risks perceived by potential landlords to lease their dwellings for a social purpose; and

Improve housing quality of properties that participate in the scheme.

The local authority transfers the rent payments to the landlord at the level of the applicable Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rate for the term of the lease, with a 10% management fee deducted for managing the property and its maintenance throughout the tenancy. In return, landlords are offered incentives to bring the property up to the required minimum quality standard, through a maintenance grant of up to GBP 2000 and an interest- free loan of up to GBP 8 000, in addition to ongoing tenancy support for the duration of the tenancy agreement.

An external assessment conducted in late 2021 reported positive feedback from participating local authorities, landlords and tenants. In terms of the proposed incentives, the maintenance grant was much more popular among landlords than the interest-free loan; the 10% maintenance fee was acceptable to landlords because it removed their maintenance responsibilities. Most tenants and landlords indicated a willingness to pursue the lease at the end of the initial tenancy contract.

Some challenges were highlighted by participants. For instance, local authorities found setting up and implementing the scheme to be relatively resource‑intensive. It could also be challenging to match tenants with housing that met their needs. There is also a need to streamline the documentation requirements from landlords during the application procedure.

1. Participating authorities include Cardiff City Council, Carmarthenshire County Council; and Conwy Council (in partnership with Denbighshire County Council). The pilot was extended (on a more limited basis) in September 2020 to Ceredigion, Newport and Rhondda Cynon Taf.

Source: (Welsh Government, 2021[30]), Evaluation of the Private Rented Sector Leasing Scheme pilot (summary), https://gov.wales/evaluation-private-rented-sector-leasing-scheme-pilot-summary-html.

Box 3.8. Social rental agencies in Belgium, France and the United Kingdom

Social Rental Agencies (SRAs) aim to increase the available social and affordable housing stock for low-income tenants and vulnerable populations. SRAs lease dwellings from private landlords and sublet them at a reduced rate to low-income groups. There is wide diversity in the setup and functioning of SRAs: services provided by SRAs can exceed mere housing provision by linking vulnerable tenants to welfare services available to them and supporting renovations to improve the quality of dwellings at the lower end of the rental market. SRAs can serve as a supplementary measure to complement existing social housing efforts by governments, beyond renting out publicly owned dwellings (Suszynska, 2017[33]). SRAs are usually either financially self-sufficient or aim to become financially self-sufficient over time (Archer et al., 2019[34]).

SRAs incentivise private apartment owners to rent their dwellings to low-income and vulnerable tenants, to be managed by SRAs. Benefits of renting to low-income tenants through SRAs include guaranteed income from rent, avoidance of vacant periods, reduced management costs and efforts, as well as tax incentives through higher rates of expense deduction (Clarke and Oxley, 2017[32]).

Several SRA experiences are worth mentioning:

In France, the Affordable Rent (Dispositif “Louer Abordable”) tax incentive encourages private landlords to rent out their flats to low-income populations by providing a reduction of the taxable rental income. The tax deduction is based on the rent level and location of the dwelling, with higher deductions in places with the most severe housing shortages. The tax advantage is subject to an agreement with the National Housing Agency (Agence nationale de l’habitat).The deduction amounts to 30% of gross rental income if the dwelling is let at a below market rate, 70% if let as social housing, and 85% if the management of the property is handed to an SRA (Ministère de l’Economie, 2022[35]). The most prominent SRA in France is Solibail, which guarantees rental payments, selects and manages tenants and maintains the dwellings. Tenants can stay in these apartments for a maximum of 18 months, after which households have to move, usually to social housing (Clarke and Oxley, 2017[32]). More than 10 000 households in Île‑de‑France have rented through Solibail to date. Similar initiatives like SOliHA have 145 SRAs across France that manage over 23 600 private dwellings. Landlords can benefit from this programme for 6 years or extend the duration to 9 years if they carry out renovation work.

In the Flanders region of Belgium, SRAs were established in the mid‑1980s as a response to homelessness and rental housing shortages in the predominantly owner-occupied market. Currently, 48 SRAs add over 10 000 affordable homes to the existing 150 000 social housing units, amounting to 1.5% of the entire private rental sector (Archer et al., 2019[34]). The government provides block grants to SRAs to fund their operation, which are mostly used for staff costs of the organisation, bringing attention to the large administrative burden of this approach. Access to SRA-managed units is means-tested, and rents are set below market rate, but above social housing rates.

In England (United Kingdom), around 100 active SRA schemes operated in 2018 (Archer et al., 2019[34]), managing over 5 500 properties across England. The focus lies in the provision of affordable housing to people experiencing homelessness, ex-offenders, refugees, people with addictions and people with disabilities. They supplement the existing system of council housing in the provision of affordable housing to vulnerable groups. SRAs in England usually set rent levels around the Local Housing Allowance (LHA). LHAs are used to calculate the local value of the Housing Benefit, which a majority of people utilising SRAs in England receive.

Consider reforms, including to the housing benefit scheme, to reach households who struggle in the housing market

As discussed in Chapter 1, single‑person and single‑parents with dependent children are at the highest risk of poverty, compared to other household types (Eurostat, 2022[36]), and are also least able to reasonably afford to access a mortgage or pay the rent. Policy makers should aim to better understand the housing situation of these households – whether they are renting in the private market, living with their parents and/or in poor quality housing, in order to determine how to better target housing support to these households. Strengthening the housing benefit scheme could be relevant – for instance by expanding the availability of the scheme to reach more households in need, including single‑person and single‑parent households (see also forthcoming report). Additional proposed amendments to housing support schemes that are currently under discussion could help to expand their reach. These include, for instance, increasing the annual income and asset limits to determine eligibility for various public supports for housing. At the same time, adjustments to the housing benefit scheme would also require parallel efforts to formalise the private rental market (see discussion later in this Chapter), since households are only eligible to receive the housing benefit if they have a formal rental contract.

Introduce measures to address some of the causes of eviction

In addition, policy makers can adopt measures to address some of the causes of eviction and to provide timely support to households facing eviction, which have been on the rise in the social housing sector. There are a number of good practice examples from other OECD countries. For instance, sending reminders to households that have missed a rental payment can help be effective in many cases. In Austria, the courts are obligated to notify local authorities of imminent evictions; a similar requirement exists in Belgium that court authorities must inform the Public Centre for Social Welfare of eviction procedures, with the added obligation that public authorities must reach out to the household to provide support (Mackie, Johnsen and Wood, 2019[37]). Further supporting residents in the phases preceding an eviction could help in addressing the contextual and behavioural causes of the phenomenon. A recent behaviourally-informed case study in this regard was conducted in the United Kingdom by the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) (Fitzhugh et al., 2018[38]). BIT worked with Metropolitan, a UK housing association with approximately 40 000 properties, to run two RCTs on rent arrears in 2017‑18. Rent arrears were a significant challenge for Metropolitan – as they are for many social landlords – with around 15‑20% of customers in arrears at any one time. In the experiment, simply reminding customers to pay their rent led to a relative reduction of arrears cases of 10%, thus diminishing grounds for evictions. Further counselling services would be needed to prevent debt accumulation, together with mechanisms for debt relief by municipalities (European Social Policy Network (ESPN), 2019[39]).

3.4. Reassessing housing support schemes for young households

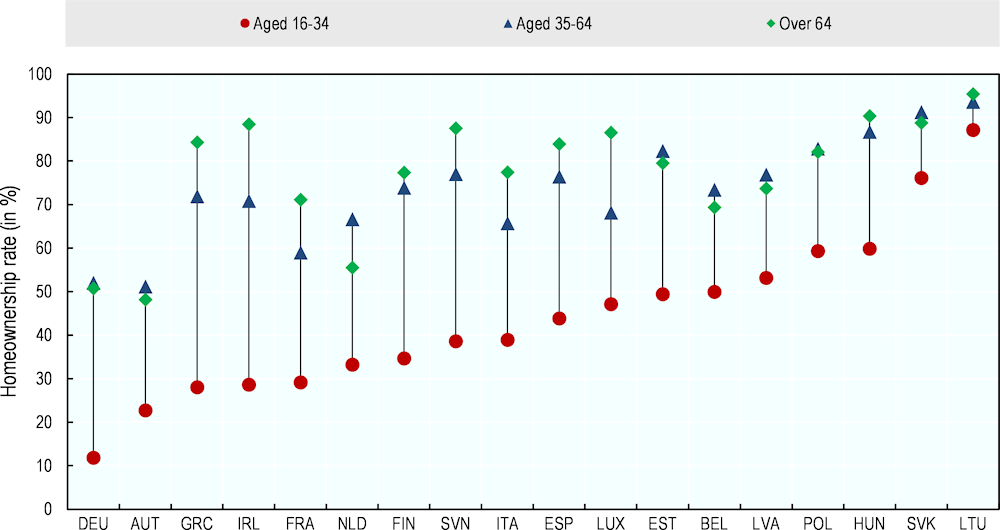

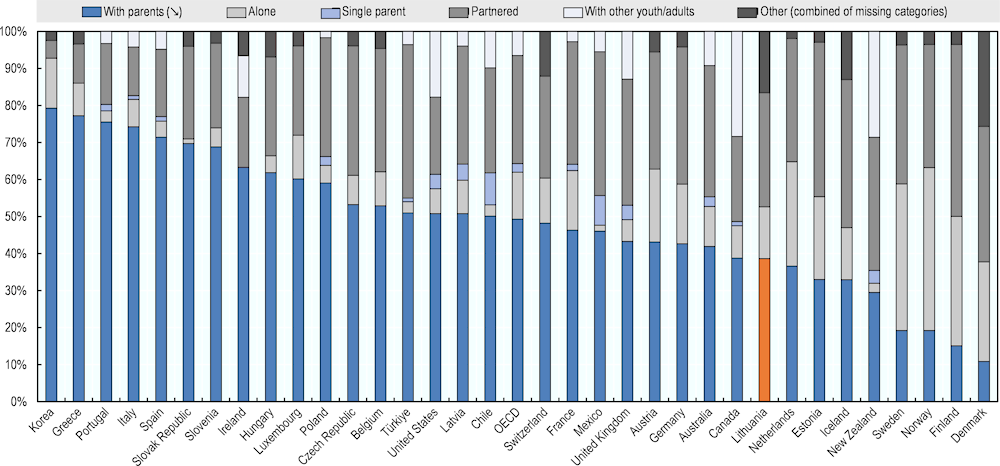

Lithuania has the highest home ownership rate in the OECD (Chapter 2). This is consistent across all households age groups, and results in the smallest spread in home ownership by age in the OECD (Figure 3.4). Nevertheless, nearly four in ten young people aged 20 to 29 years old live with their parents (Figure 3.5). This is likely related to limited prospects for home ownership relative to older households and a thin rental market (OECD, 2022[18]).

Figure 3.3. The spread in home ownership by age is small in Lithuania

Note: Compared to the original dataset, some age groups have been merged to keep the graph readable. Merging was done by calculating a weighted average of homeownership rates based on the number of persons in each age group.

Source: ECB (2017) Household Finance and Consumption Survey.

Figure 3.4. Over half of Lithuanian young people aged 20‑29 years old live with their parents

Note: Data refer to 2019 for Germany, Ireland, Italy and Poland; to 2018 for Iceland, the United Kingdom and the United States, to 2017 for Canada, Chile and Ireland, to 2016 for Korea, to 2015 for the Republic of Türkiye and 2012 for Japan.

Source: (OECD, 2022[18]), Affordable Housing Database – OECD, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

3.4.1. Existing support schemes: Subsidies for down-payment assistance

Currently, two programmes aim to support young families in Lithuania in purchasing their first home by providing financial support for a down-payment. Both programmes target households under 36 years old and are operated by the Ministry of Social Security and Labour. It should be noted that public support in the housing market prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) was of a much different nature than today, as it focused on the provision of subsidies for mortgage insurance premia, a mortgage interest tax deduction and public mortgage insurance. However, the fallout from the GFC and the significant financial instability led to a sharp decline in housing prices, defaults and the shutdown of the government-owned mortgage insurance company (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[9]).

Means-tested support for a down-payment

As outlined in the Law on Support for Acquisition or Rental of Housing, a means-tested housing credit support programme, Parama bustui isigyti, provides households who meet income and asset tests with a subsidy to contribute to a mortgage or down-payment for the purchase of their first home. The subsidy amount, which is funded by the State with budget allocations that vary annually, is determined by household size and type (larger households are eligible for a larger subsidy, ranging from 15% to 30% of the housing loan), as well as the value of the loan (with a maximum limit on the loan value capped at EUR 53 000 for a single‑person household, EUR 87 000 for a household of two or more people, and EUR 35 000 for renovation/upgrades to an existing dwelling). A CEB analysis calculated that the subsidy reduced the beneficiary’s own contribution by around 6.5% (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[9]).

Nevertheless, the reach of the subsidy programme thus far has been modest, covering less than 3% of all new mortgages between 2015 and 2019. In 2021, total spending on the programme amounted to over EUR 2.8 million, reaching more than 330 households, for an average benefit amount of just around EUR 8 500 per households. This nevertheless represents a decline of overall funding and number of beneficiaries from 2018, which allocated a total of EUR 4.3 million, equivalent to an average of roughly EUR 6 500 to 660 households (OECD, 2019[40]). The MSSL attributes the drop in take‑up in 2021 to the introduction of a second, more attractive, scheme to support young families (described below), which until recently offered larger subsidies and was not means-tested; the subsidy amounts of the two programmes have since been harmonised. The amount of subsidies that can be disbursed is dependent on the annual budgetary appropriation, and has fluctuated considerably from year to year (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[9]).

Financial support to buy a home outside the main cities

The second scheme was introduced in 2018 through the Law of the Republic of Lithuania on Financial Incentive for Young Families Acquiring a First Home (Finansine paskata pirmaji busta isigyjancioms jaunoms seimoms). The aim of the scheme is twofold: i) to help young families to purchase their first home in Lithuanian regions (e.g. outside the main cities; eligible regions are determined by a maximum average house price); and ii) to contribute to regional development and territorial cohesion. A related objective is to reduce demographic decline, through both the emigration of young families as well as a declining fertility rate. This support scheme thus aims to leverage housing policy to meet both regional development and demographic policy objectives.

Contrary to the means-tested housing credit support programme discussed above, under this scheme households are not required to meet income or asset tests. There is also no requirement that the home purchased must be used as a primary residence. Eligible households receive a subsidy that can be used to cover part of the mortgage payments or the down-payment. The amount of the subsidy depends on the household size and composition, ranging from 15% of the total loan value for families without children, to 30% for households with three or more children; the value of the housing loan is capped at EUR 87 000.

Between September 2018 and August 2022, just over 5 000 young households benefitted from the programme. In 2021, the average benefit amounted to around EUR 10 400 per household for a total of EUR 20.8 million. Nevertheless, the maximum subsidy available is much higher (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[9]). Funding for the programme comes from the State budget, and the reach of the programme is much more significant than the means-tested housing support. Since its introduction, the scheme has proven popular among young families. In a 2019 survey of families who had benefited from the programme, around two‑thirds of beneficiaries reported that they would not have been able to purchase a home without the State support. The survey also found that 75% of beneficiaries were employed and over 60% had higher education degrees; just under one in three households used the scheme to buy a home outside their municipality of origin. According to data provided by MSSL, a disproportionate share of the subsidies (18%) were allocated to young families in the Klaipėda municipality between September 2018 and August 2022; the next-largest share (7%) of subsidies were allocated to young families in Kaunas.

3.4.2. Recent advances and remaining challenges

Several challenges and inefficiencies are reported for both home ownership support programmes. First, the two programmes targeting youth mix diverse policy objectives, attempting to address a combination of housing policy objectives (help young people purchase their first home); social policy objectives (help low-income young people purchase a home, in the case of the means-tested programme); demographic objectives (reduce the emigration of young people from regions and support fertility); and regional development/territorial cohesion (generate economic activity in declining regions). It is difficult to design a programme that would effectively meet all three objectives: for instance, many young households may prefer to purchase a home in the capital area, where the subsidy does not apply. There is no requirement that beneficiaries live in the purchased dwelling for a minimum amount of time, as is the case in similar programmes in OECD countries; anecdotal evidence suggests that some households use the subsidy to purchase a second holiday home, though data are not available to confirm. Other challenges include:

Inefficiencies in the process to apply for and obtain government support: Administrative delays in the time it takes for a household to apply for and receive the subsidy are reportedly a significant challenge. Households must apply for the public support scheme before applying for a loan; many households who are eligible for the public support do not ultimately receive a bank loan (e.g. because they are not deemed creditworthy), which creates inefficiencies in the process. Despite the government support, many young households still lack sufficient savings to contribute to the down-payment, which is generally 15% of the home value.

Potential capturing of the subsidy by the commercial lenders: There is also the potential for a portion of the public subsidies to be captured by the lenders, given that the subsidy amount is dependent on the loan value, rather than the value of the asset; households are thus incentivised to take out the maximum loan value. Further, analysis from the CEB suggests that only a handful of commercial banks participate in the two government programmes, and they do not necessarily offer the best rates to consumers (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[9]).

The programmes are costly. Combined, the two home ownership support programmes for young families amounted to EUR 23.6 million, reaching over 2 300 households. By comparison, in the same year (2021), the direct financial support provided to low-income households under the rental compensation scheme and energy allowance amounted to around EUR 23.4 million, reaching 3 725 and 100 500 beneficiaries, respectively (Chapter 3).

Recent legislative amendments in means-tested housing support resulted in an increase in the subsidy amount that is reimbursed by the State. This means a reimbursement of 15% of the housing loan for young families without children; 20% for households raising one child; 25% for households raising two children; and 30% for households raising three or more children, for people with disabilities (or households that include a person with a disability), people under age 36 who were left without parental guardianship, single‑parent families.

3.4.3. Recommended policy directions

Two important policy directions to improve housing supports for youth are to first assess the impacts of the two support schemes, and to consider transitioning from demand-side to more supply-side supports for young people. The Lithuanian authorities are currently re‑assessing the support schemes targeting young families, which is a welcome development.

Assess the impacts of current housing supports for young households

Assessing the take‑up and impact of the existing support programmes for youth will help to better understand whether, and to what extent, these programmes have been effective in expanding home ownership among young households who would not otherwise have been able to purchase a home. A continued evaluation of the programmes can support the government to course correct as needed and make evidence‑based decisions on potential alternatives to the existing measures to support young households.

Transition towards supply-side policies to boost and improve housing supply

Currently, government supports for young people focus on demand-side measures that aim to increase their access to home ownership, by providing down-payment assistance. However, these types of measures have been demonstrated to drive up housing costs overall – particularly when they are not accompanied by efforts to increase the housing supply (Pawson et al., 2022[41]). This is because most first-time homebuyer assistance measures primarily result in accelerating a first home purchase among households that are already close to doing so, rather than expanding home ownership opportunities to households who would otherwise be excluded; as a result, such measures increase demand and, accordingly, house prices (Pawson et al., 2022[41]).

Given that in Lithuania the main issue is the lack of good quality affordable housing, demand-side home‑ownership support policies should be accompanied by parallel efforts to expand the housing supply to avoid further pressure on house prices. As a result, the government should aim to invest more in the construction and maintenance of social and affordable dwellings to support households – including young households – in the housing market (discussed further in Chapter 4). At the same time, policy makers should consider expanding housing supports for young people beyond home ownership support. The formal rental market is thin and unaffordable, and thus does not represent a viable alternative for young households. Young people, who also tend to be more mobile than older households, could benefit from a developed formal rental market; the rental market is also generally more flexible and requires fewer initial resources compared to home ownership. Lithuania should thus consider providing alternatives to home ownership by incentivising the expansion of the formal rental market. As discussed in the next section, such efforts would call for changes to the current legal and tax framework to help incentivise investment and bring the current informal rental market out of the shadows.

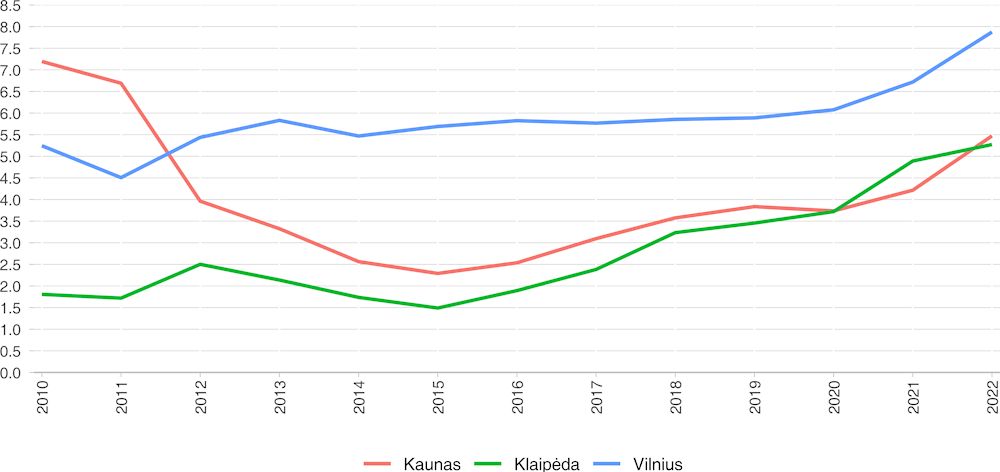

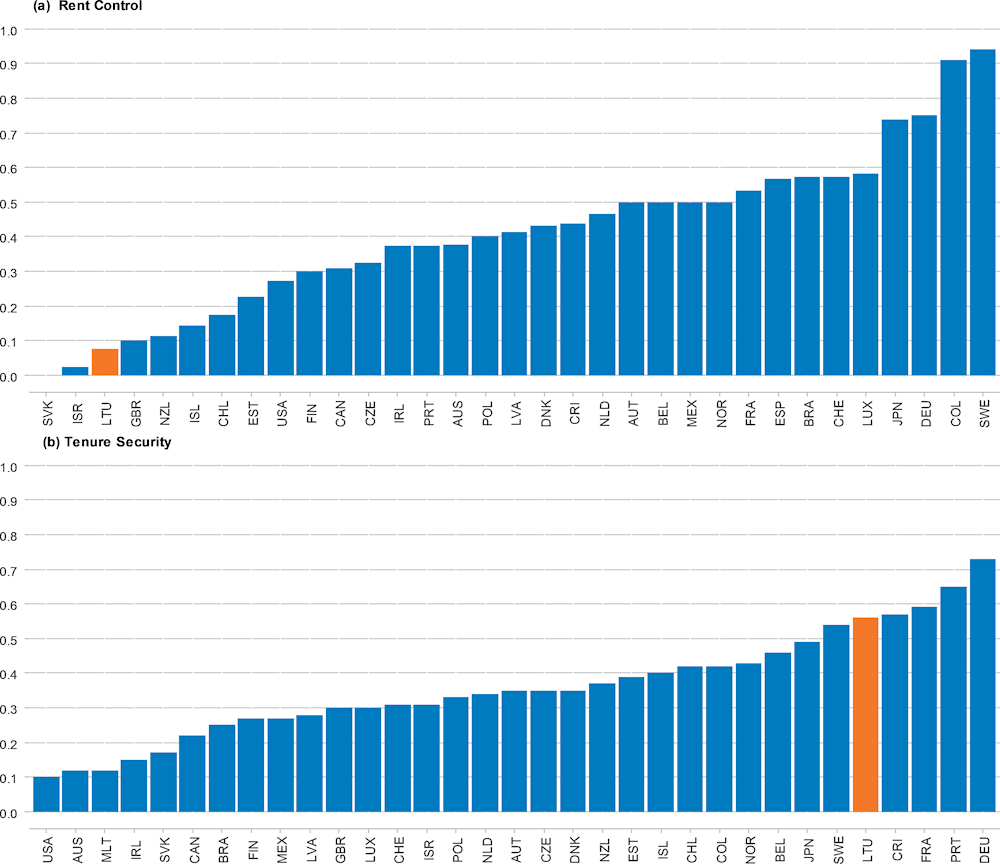

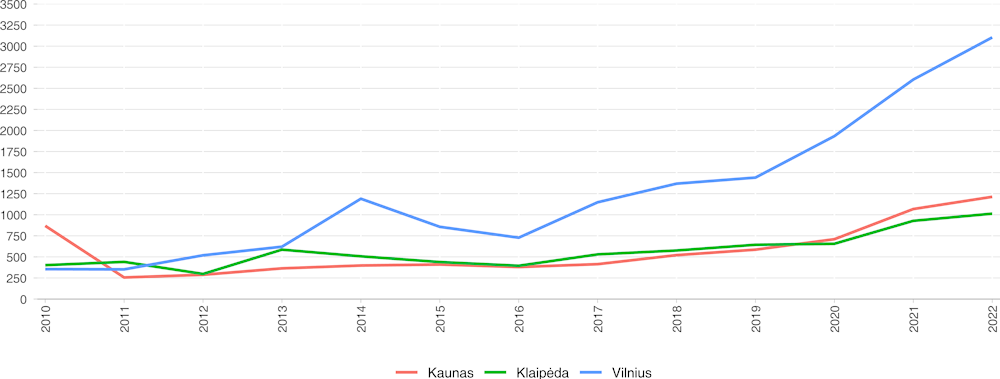

3.5. Bringing the private rental market out of the shadows

Renting an apartment is a significant challenge in Lithuania. As discussed in Chapter 2, the formal rental market is thin and unaffordable to most households. This is partially due to the historic development of the housing market in Lithuania; however, public policy continues to play an important role. The tax system in particular favours home ownership over renting, and corporate investors in the rental market over small landlords, which disincentivises investment in new rental construction and facilitates informality in the rental market. Further, tenancy arrangements fail to strike a balance between the interests of landlords and tenants, reducing the attractiveness of renting in the formal market among both landlords and tenants. Recent advances, including the introduction of a system of business certificates to better monitor activity in the rental market, have aimed to encourage formality in the rental market and contribute additional revenues to municipalities. Nevertheless, more could be done to bring the private rental market out of the shadows by creating the conditions to develop and expand the rental market, while protecting vulnerable tenants.