This chapter proposes a way forward for the Lithuanian Government to make housing a policy priority. Complementing the assessment of the current policy support measures in Chapter 3, this chapter outlines more structural challenges to housing policy, relating to governance, investment and spending. It then sets out a road map for Lithuanian policy makers to build a strategic agenda for housing, by elevating the importance of housing as a political priority, strengthening capacity at municipal level, and boosting investment in housing.

Policy Actions for Affordable Housing in Lithuania

4. A way forward: Making housing a policy priority in Lithuania

Abstract

4.1. Introduction and main findings

Persistent housing quality gaps – driven in part by the historical development of the housing stock – and emerging housing affordability struggles represent twin challenges for Lithuanian policy makers (Chapter 2). While there has been some important progress in recent decades to boost housing quality and introduce housing support schemes to target groups, a number of more structural challenges remain. Housing policy making remains fragmented across ministries and levels of government. There is no current national strategy to guide housing priorities, public spending or investment. Municipalities have a significant – and growing – set of housing-related responsibilities, with limited financial and technical resources; their scope for action is further constrained by stringent limits on their capacity to raise own-revenues. Further, even though the government has gradually increased investment and spending on housing in recent years, levels remain very low overall, and the State has fully withdrawn from funding social housing development.

The current economic and political context risks exacerbating the housing affordability challenge and accentuating the need for more rapid improvements to the quality and energy efficiency of the housing stock, as policy makers must continue to navigate the ongoing recovery from the COVID‑19 pandemic, respond to the current cost-of-living crisis, and manage the far-reaching impacts of the war in Ukraine. As a result, affordability pressures for Lithuanian households in the housing market may deepen. On the one hand, construction costs and energy prices continue their rapid ascent, in a context of mounting inflationary pressures. On the other hand, the influx of over 76 000 Ukrainian refugees who have registered for Temporary Protection in Lithuania since the onset of the war in Ukraine1 may further strain the housing market and public support schemes for housing (see Box 2.1 in Chapter 2). Indeed, the Ministry of Environment has already reported increased demand for public support for housing, including demand-side supports (such as the monthly energy and utility allowance) and financial support to improve the quality and energy efficiency of the housing stock (Chapter 3).

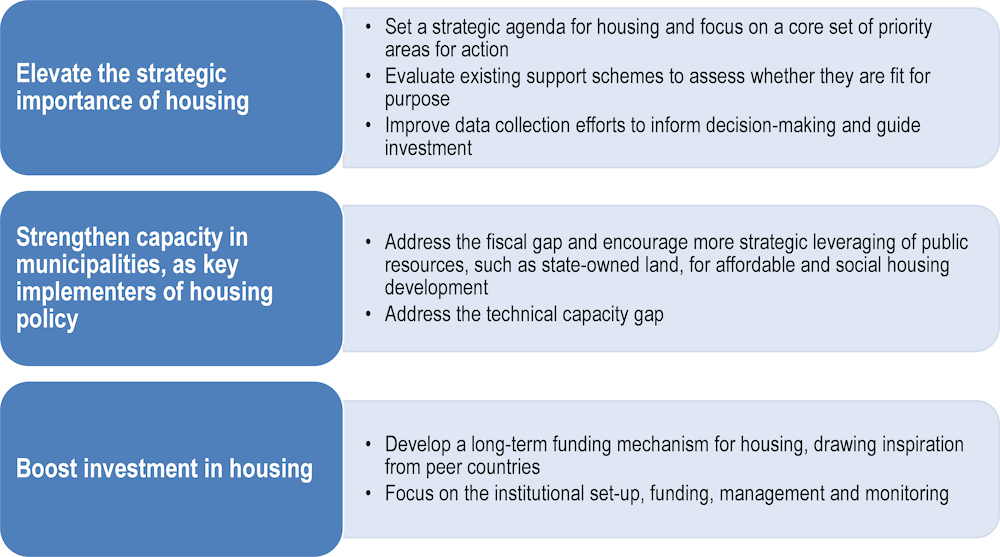

These co‑existing crises present Lithuanian policy makers with an opportunity to elevate the strategic importance of housing policy on the political agenda, and chart the path towards more affordable, sustainable housing. To do so, this chapter proposes a road map for policy action for the Lithuanian Government, which can be outlined as follows:

Set a strategic agenda for housing, focusing on a core set of priorities, and assess the current housing support schemes to determine whether they are the most effective tools to achieve the government’s aims;

Take steps to address the structural challenges relating to governance, investment and spending that continue to constrain progress. This includes strengthening the capacity of municipalities to carry out their key role as implementers of national housing policy; and

Increase investment and put more emphasis on supply-side supports for housing, potentially through the establishment of a long-term, sustainable funding mechanism for affordable and social housing.

This chapter begins by outlining structural challenges to housing policy in Lithuania relating to governance, investment and spending. It then proposes a series of recommendations for Lithuanian policy makers to advance a strategic agenda for housing.

4.2. Overcoming persistent governance, investment and spending challenges in housing policy

A number of governance challenges stymy a more effective housing policy response in Lithuania. Housing responsibilities are fragmented across ministries and levels of government, with limited strategic co‑operation across ministries relating to housing policies. The absence of an updated national housing strategy means that there is no current clear strategic direction to guide housing policies and investments. Further, in recent years, the government has increased investment and spending levels on housing in some areas, yet levels remain low overall relative to other OECD countries. Moreover, the State has gradually withdrawn from funding social housing development, leaving the bulk of funding responsibilities to the EU and, to a lesser extent, municipalities. Finally, there is a large and growing mismatch between the considerable housing-related responsibilities of municipal authorities, and their limited technical and financial capacities.

4.2.1. Fragmented housing responsibilities across ministries and levels of government

Housing responsibilities are fragmented across a range of actors and institutions at different levels of government in Lithuania. At central level, the Ministry of Environment (MOE), which is designated as the lead ministry for housing policy, and the Ministry of Social Security and Labour (MSSL) carry out the bulk of housing-related responsibilities, including the design of the main housing schemes to facilitate energy efficiency upgrades in the existing stock and to support households in need. Meanwhile, many other ministries and national agencies are involved in different aspects of housing policy (Table 4.1). This includes, for instance, agencies involved in social housing investment (the Central Project Management Agency, which is overseen by the Ministry of Finance), energy efficiency upgrades of the housing stock (APVA, overseen by the Ministry of Environment), and the management of state‑owned land (National Land Service, overseen by the Ministry of Agriculture).

Meanwhile, municipal authorities have a central role in the implementation of national housing support schemes and in the delivery and management of social and municipal housing. There is no direct responsibility for housing at regional level in Lithuania, although regional development councils, established in 2010, are involved in policy areas that have implications for housing, such as regional planning and urban development. It is expected that municipal authorities – which receive EUR 332 million in EU funding to develop and maintain the social housing stock – will present their plans for social housing development to the Regional Development Councils. Other independent and non-governmental actors are also involved in different ways: the Bank of Lithuania is responsible for macroprudential tools that affect the housing market (such as requirements relating to loan-to-value and debt-service‑to‑income, limits on loan maturity). Some (but not all) commercial banks participate as lenders in government support schemes to help young families access home ownership (Chapter 3). Meanwhile, organisations such as Caritas provide shelter and social supports to the homeless and other vulnerable populations.

This fragmentation of housing policy responsibilities is not uncommon in OECD countries. Indeed, there is no “typical” ministry responsible for housing matters: it is more common to have a lead ministry to facilitate co‑ordination around housing policies, and housing responsibilities are often shared across different levels of government (Box 4.1). As in other OECD countries, sub-national governments are responsible for a significant share of spending on housing-related programmes in Lithuania (discussed later in this Chapter).

Further, there is limited strategic co‑operation with other ministries that are responsible for key aspects of housing regulation, investment and development, including the Ministry of Justice (rental market regulations); the Ministry of Interior (regional and local planning and the financial allocation of investments); and the Ministry of Agriculture (land management and administration). As discussed in Chapter 3, there is considerable scope to leverage these critical aspects of housing and urban development towards shared objectives for a more affordable and sustainable housing stock. Currently, despite persistent challenges relating to housing quality and emerging affordability gaps and the current cost-of-living crisis (Chapter 2), housing does not appear to be top policy priority.

The fragmentation of housing policy responsibilities is compounded by the absence of an up-to-date national housing strategy in Lithuania, contrary to over 20 other OECD countries with a current national strategy (OECD, 2022[1]). The most recent Housing Strategy 2020, which was approved in 2004 and prepared by the Ministry of Environment, identified three overarching objectives: i) to expand housing options for all social groups; ii) to ensure efficient use, maintenance, renewal and modernisation of existing housing and rational use of energy resources; and iii) to strengthen the capacity of housing sector actors to participate in the housing market (Box 4.2) (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2004[2]). Many of the objectives of Housing Strategy 2020 remain relevant. However, there is no current strategic document to provide a global view of housing policy challenges or housing policy supports, to guide investments or decision-making, or to identify the actors and actions that can foster a more co‑ordinated, whole‑of-government approach to housing policy. The absence of a centralised system to share housing-related data across different actors in the government was already highlighted in the 2004 Housing Strategy, making it “difficult to analyse the housing situation and to make timely policy decisions on the basis of objective information” (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2004[2]).

Table 4.1. Housing-related responsibilities of different public actors in Lithuania

|

Ministry or institution |

Housing-related responsibilities |

|---|---|

|

Ministry of Environment |

|

|

Ministry of Social Security and Labour |

|

|

Ministry of Justice |

|

|

Ministry of Interior |

|

|

Ministry of Finance |

|

|

Ministry of Agriculture |

|

|

Bank of Lithuania |

|

|

Municipal authorities |

|

1. As of 1 November 2021, APVA replaced the Housing Energy Efficiency Agency (BETA) in managing energy efficiency programme for housing. 2. CPMA was established in 2003 through a merger of the Central Financing and Contracting Unit and the Housing and Urban Development Fund, both responsible for implementing projects financed by the EU and international financing institutions. 3. The National Land Service includes 50 territorial management divisions serving all municipalities.

Source: OECD, based on (Mikelėnaitė A., n.d.[3]), TENLAW: Tenancy Law and Housing Policy in Multi-level Europe. National Report for Lithuania, https://estatedocbox.com/73101814-Buying_and_Selling_Homes/Tenlaw-tenancy-law-and-housing-policy-in-multi-level-europe-national-report-for-lithuania.html; (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2004[2]), Lithuanian Housing Strategy, https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.225703#part_57774e1062104af19f1dfa3fde8c15bd.

Box 4.1. Responsibilities for housing depend on different ministries across the OECD

Across the OECD, there is no “typical” ministry responsible for housing matters (Table 4.2). Twenty countries have a dedicated ministry for housing and/or urban development. In other countries, however, housing policies are part of other ministerial portfolios, including regional development and/or territorial cohesion (7 countries), economic development/infrastructure (6 countries), the environment (4 countries), economy and/or finance (4 countries), social affairs (4 countries), among others.

In many countries housing responsibilities are shared across two or more ministries, given the range of tools and measures that may be introduced to support a more affordable, sustainable and fair housing market, such as, inter alia, macroprudential decisions; regulations relating to property ownership, rental agreements, housing quality and environmental sustainability; taxation of land and residential properties; property rights and registration; public support schemes to support households in accessing quality and affordable housing; or management and investment in social and municipal housing.

Different levels of government are often responsible for distinct aspects of housing policy: national governments may set the rates for property taxes, while municipalities collect the tax; national governments may establish the eligibility criteria and benefit amounts for public supports (like housing allowances or social housing), while local governments administer the support schemes and maintain and develop the social housing stock.

Table 4.2. The lead ministry for housing policy varies across countries

Lead ministry at national level responsible for housing policies

|

Lead ministry for housing policies |

Countries |

|---|---|

|

Ministry of Economy and/or Finance (Treasury) |

Australia, Estonia, Latvia |

|

Ministry of Interior |

Denmark* (Ministry of Interior and Housing) |

|

Housing/Urban Development |

Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark* (Ministry of Interior and Housing), Germany, Ireland, Israel, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, the Slovak Republic* (Transport and Construction), Slovenia* (Environment and Spatial Planning), Spain* (Transport, Mobility and the Urban Agenda), Switzerland, Türkiye* (Environment and Urbanisation), the United Kingdom (England)* (Housing, Communities and Local Government), the United States |

|

Environment |

Finland, Lithuania* (Social Security and Labour), Slovenia* (Environment and Spatial Planning), Türkiye* (Environment and Urbanisation) |

|

Regional Development/Territorial Cohesion/Local Government |

Bulgaria, Brazil, the Czech Republic, France, Norway, Romania, the United Kingdom (England)* (Housing, Communities and Local Government) |

|

Economic Development/Infrastructure |

Spain* (Transport, Mobility and the Urban Agenda), Italy (Infrastructure and Sustainable Mobility), Japan, Korea, Poland, the Slovak Republic* (Transport and Construction) |

|

Social Affairs |

Greece, Iceland, Lithuania* (Environment), Malta |

|

Shared across ministries |

Australia, Austria, Sweden |

|

Not a direct national competency; handled at subnational level |

Belgium |

*In some countries, the competencies of the lead ministry for housing policy cover multiple categories in this table. Such cases have been marked with an asterisk and cross-posted in the relevant categories.

Source: Adapted from country responses to the 2021, 2019 and 2016 OECD Questionnaire on Affordable and Social Housing (QuASH).

Box 4.2. Key objectives of Lithuania’s National Housing Strategy 2020, released in 2004

Lithuania’s most recent national housing strategy, National Housing Strategy 2020, was approved in 2004 and developed with support from the World Bank and the Council of Ministers of the Nordic States. The strategy analysed the current housing situation and identified the main policy objectives and priorities, in addition to the key steps to implementation. The three overarching ambitions of the strategy include:

Expand housing options for all social groups: this included efforts to increase the supply of non-profit rental housing and social housing, as well as the supply of housing for middle‑ and high-income households (both rental and owner-occupied dwellings); and to target public financial support to households who could not afford housing (particularly families with children and people with disabilities). Specific proposed measures included, inter alia, strengthening the legal framework governing landlord-tenant relations.

Ensure the efficient use, maintenance, renewal and modernisation of existing housing and rational use of energy resources: the overarching aim of this objective was to improve the quality of the existing housing stock, to increase the value of housing and adapt dwellings to the evolving needs of households, and to reduce social segregation in the housing stock. Specific issues to address included modernising the heating systems in apartment buildings by 2020 and improving the technical quality of housing (roofs, insulation, eliminating systemic defects in multi-family buildings); reducing energy consumption; and providing effective financial support to low-income households to improve housing quality.

Strengthen the capacity of housing sector actors to participate in the housing market: To boost the overall quality and effectiveness of the housing sector at all levels of government, the strategy proposed establishing a coherent governance system and co‑ordination mechanisms; ensuring consumer rights protections; and providing training and education to actors in the housing sector.

Source: (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2004[2]), Lithuanian Housing Strategy, https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.225703#part_57774e1062104af19f1dfa3fde8c15bd; OECD discussions with government officials during the Study Mission in September 2021.

4.2.2. Limited public investment and State spending on housing

Despite a recent uptick, public investment in housing development remains low

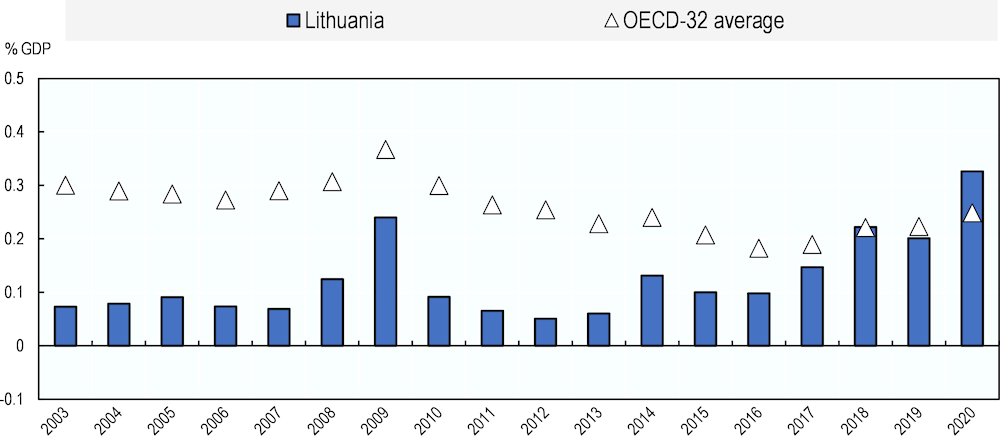

Over the past two decades, public investment in housing development in Lithuania has been uneven. Between 2003 and 2020, public investment in housing and community amenities2 averaged around 0.12% of GDP, peaking in 2009 at 0.24% of GDP, before dropping significantly in the post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) period (Figure 4.1). Through 2017, public investment in housing and community amenities in Lithuania remained well below the OECD average, though the gap closed in 2018, when public investment levels in both Lithuania and the OECD averaged around 0.22% of GDP. The narrowing is the result of, on the one hand, an uptick in Lithuania’s public investment following the significant drop of the post-GFC, as well as, on the other hand, the steady decline of public investment in housing among OECD countries. In 2020, public investment in housing in Lithuania surpassed the OECD average. Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that, even though Lithuania has closed the public investment gap in housing, levels remain low overall – both in Lithuania and in the OECD.

Figure 4.1. Public investment in housing and community amenities has been uneven in Lithuania

Note: Direct investment (COFOG series P5_K2CG) refers to government gross capital formation in housing and community amenities. Public capital transfers (COFOG series D9CG) refers to indirect capital expenditure made through transfers to organisations outside of government towards housing and community amenities. Housing and community amenities includes, among other things, housing development; community development; water supply; street lighting; R&D housing and community amenities; and housing and community amenities N.E.C. See the Eurostat Manual on sources and methods for the compilation of COFOG Statistics (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5917333/KS-RA-11-013-EN.PDF) for more detail. The OECD‑32 average is the unweighted average across the 32 OECD countries with capital transfer and gross capital formation data available for all years between 2003 and 2019. It excludes Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, New Zealand and Türkiye.

Source: OECD National Accounts Database, www.oecd.org/sdd/na/

Further, as in many OECD countries, subnational governments also play an important role in public investment in housing. In 2019, Lithuanian municipalities were responsible for around 40% of total public investment overall, of which they dedicated nearly 14% towards housing and community amenities, behind economic affairs (around 38%) and education (17%) (OECD, 2021[4]).

Social spending on housing remains comparatively low, though levels have increased considerably in recent years

Social spending on housing in Lithuania – which broadly corresponds to spending on social housing and housing allowances – remains very low from a comparative perspective. The share of spending on housing continues to represent less than 1% of total spending on social protection benefits in Lithuania (Official Statistics Portal of Lithuania, 2021[5]). Nevertheless, social spending on housing has quintupled in absolute terms over the past decade, increasing from around EUR 7.5 million in 2010 to EUR 35.5 million in 2020. It is dominated by social housing expenditures (which make up more than three‑quarters of total social spending on housing), followed by cash benefits to low-income homeowners (around 17% of the total), and means-tested rental allowances (6% of the total). Spending on rental allowances has recorded the most significant growth, representing less than 1% of total housing spending in 2015 (the year of the introduction of the measure), to nearly 6% of total social spending on housing in 2020.3 Even so, from a comparative perspective, current levels of spending on housing allowances in Lithuania, at around 0.06% of GDP, remain extremely low, amounting to around one‑fifth of the OECD average of 0.3% of GDP in 2019 (Table 4.3) (OECD, 2021[6]).

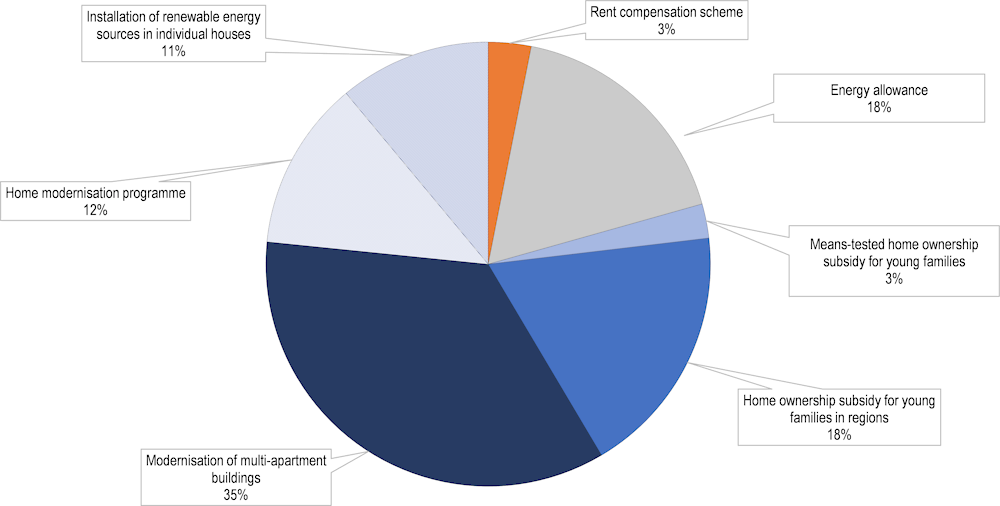

Three‑quarters of State spending on housing is allocated to improve housing quality

Among the various housing support schemes financed by the State budget, the Ministry of Environment managed about 60% of total State spending on housing in 2021, which primarily aimed to improve the quality and energy efficiency of the housing stock (Table 4.3, Figure 4.2). This includes the modernisation of multi‑apartment buildings (Daugiabuciu namu atnaujinimo (modernizavimo) programa) – which represented just over one‑third of State spending on housing overall; the home modernisation programme (Fiziniu asmenu vieno ar dvieju butu gyvenamuju namu atnaujinimas (modernizavimas) (12%); and the installation of renewable energy sources in individual homes (Atsinaujinanciu energijos ištekliu (saules, vejo, biokuro, geotermines energijos ar kt.) panaudojimas individualiuose gyvenamosios paskirties pastatuose) (11%) (see Chapter 3 for further detail on the programmes).

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Social Security and Labour managed housing support schemes that made up around 40% of total State spending on housing in 2021. This includes two programmes that aim to help households purchase their first home (the home ownership subsidy for young families in regions [Finansine paskata pirmaji busta isigyjancioms jaunoms seimoms], accounting for 18% of State spending on housing, and a means-tested programme that supports low-income and vulnerable households, including young families [Parama bustui isigyti]), representing 2% of total spending; the heating compensation support scheme (Būsto šildymo, geriamojo ir karšto vandens išlaidų kompensacijos) (18%); and the partial reimbursement of rental housing costs (Busto nuomos mokescio dalies kompensacija) (3%).

In recent years, the State has gradually withdrawn from spending on social housing development, which is now covered by funding from the European Union, with a minimum co-funding requirement by municipalities (discussed below). Over 2016‑20, up to EUR 48.9 million in EU structural funds were allocated to the programme, with an additional 15% to be financed by municipal budgets, as outlined in the Law on Support for Acquisition or Rent of Dwelling.

In terms of the reach and generosity of the various programmes, the energy/utilities allowance has the broadest reach, reaching over 100 500 households in 2021, for an average benefit of just under EUR 200 per person per year. The modernisation of multi‑apartment buildings had the second-largest reach, benefitting nearly 13 000 dwellings in 2021. However, in terms of benefit generosity, the home ownership subsidy for young families in regions provided, on average, the largest benefit amount, at around EUR 10 400 per dwelling. The next most generous schemes were the means-tested homeownership subsidy for low-income and vulnerable groups (nearly EUR 8 500 per household) and the home modernisation programme (around EUR 7 140 per dwelling).

Table 4.3. State spending on housing programmes in Lithuania

|

Name of measure/support |

State funding (EUR) |

Beneficiaries/dwellings served |

Average benefit per beneficiary/ dwelling (EUR) |

Year |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MSSL |

MOE |

Beneficiaries (households) |

Beneficiaries (dwellings) |

|||

|

For tenants: |

||||||

|

Rent compensation scheme (Busto nuomos mokescio dalies kompensacija) |

3 529 000 |

3 725 |

2021 |

|||

|

For tenants and/or homeowners: |

||||||

|

Energy/utilities allowance (Busto ildymo ilaidu, geriamojo vandens ilaidu ir karto vandens ilaidu kompensacijos) |

19 840 000 |

100 500 |

2021 |

|||

|

For homeowners: |

||||||

|

Means-tested home ownership subsidy for low-income and vulnerable households, including young families, (Parama bustui isigyti) |

2 825 000 |

3341 |

2021 |

|||

|

Home ownership subsidy for young families in regions (Finansine paskata pirmaji busta isigyjancioms jaunoms seimoms) |

20 800 000 |

2 0002 |

2021 |

|||

|

Modernisation of multi‑apartment buildings3 (Daugiabuciu namu atnaujinimo (modernizavimo) programa) |

39 800 000 |

12 886 |

3 089 |

2021 |

||

|

Home modernisation programme (Fiziniu asmenu vieno ar dvieju butu gyvenamuju namu atnaujinimas (modernizavimas)) |

14 000 000 |

1 960 |

8 654 |

2021 |

||

|

Installation of renewable energy sources in individual houses (Atsinaujinanciu energijos itekliu (saules, vejo, biokuro, geotermines energijos ar kt.) panaudojimas individualiuose gyvenamosios paskirties pastatuose) |

12 500 000 |

4 349 |

2 874 |

2021 |

||

|

Total |

46 994 000 |

66 300 000 |

106 559 |

19 195 |

– |

2021 |

1. This figure also includes 9 persons (families) who received additional subsidies. 2. This figure also includes 420 young families who received additional subsidies. 3. The modernisation of multi‑apartment buildings also benefits from funding from municipal authorities and the European Union. The social housing development programme is excluded because it is largely financed by the EU, with a share of co-funding by municipalities (e.g. no direct State funding).

Source: Information provided by the Ministry of Social Security and Labour and the Ministry of Environment.

Figure 4.2. The majority of State spending on housing aims to facilitate access to home ownership and improve housing quality

Note: Schemes to support existing or prospective homeowners are shaded in blue; schemes to support tenants are shaded in orange; schemes that support both tenants and homeowners are shaded in grey. The social housing development programme is excluded because it is largely financed by the EU, with a share of co-funding by municipalities (e.g. no direct State funding).

Source: Information provided to the OECD by the Ministry of Social Security and Labour and the Ministry of Environment.

Progressive withdrawal of the State funding from social housing development

In recent decades, the central government has withdrawn from directly funding social housing development, while the European Union has taken on an increasingly primary role, with a sustained albeit declining contribution from municipal authorities:

2004‑07: Approval of State funds to support municipalities in developing social housing. To respond to the objective outlined in the Lithuanian Housing Strategy 2020 to expand housing options for all social groups, the government approved in 2004 to allocate funding to municipal authorities for the development of social housing. Created in response to the sizeable waiting list for social housing, the programme was intended to increase funding for municipal social housing to be leased to low-income households in accordance with the Law on State Support for Acquisition or Lease of Housing. In the first three years, total funding to be allocated to municipalities amounted to 65 million lita (roughly EUR 18.8 million), divided among 60 local entities, with around one‑third of the funding allocated to Vilnius where social housing needs were assessed as the most significant (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2004[2]).

2007‑13: Introduction of EU funding to complement State and municipal resources. Partly in response to the global financial crisis, the contribution of EU funding, through the structural fund programming for 2007‑13, provided additional support to convert buildings into social housing and to renovate social housing (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[7]); the State and municipalities allocated funds for the development of the social housing stock. During the 2007‑13 period, of the total EUR 28.2 million budgeted for the fund, the State contributed roughly 65% of total, municipalities covered around 21%, and 13% came from the EU (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[7]). The result was around 900 social housing units added to the stock during this period, with the vast majority of these units (over 600 dwellings) purchased from the existing stock and converted to social dwellings.

2014‑20 – A much larger role for EU funding and the withdrawal of State funding. Over the most recent period, covering 2014 to 2020, the overall funding for the programme increased significantly, due in large part to the substantial increase in the share of the EU’s contribution, to assume around 85% (up to EUR 49.9 million) of the total funding amount, provided as grants through EU structural funds. The remaining 15% of the funding allocation was to be covered by municipalities’ own funding, drawing on rental revenue and sales from municipal and social housing. The State no longer contributes financially to the programme. At the end of 2019, over 1 170 social housing units were added to the overall stock (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[7]). Spending on social housing in Lithuania was around one‑tenth of the EU-average in 2019, at around EUR 10 per inhabitant compared to around EUR 101 per inhabitant in the EU (European Commission, 2022[8]).The financial support from the EU has helped to increase the speed with which new social housing could be developed (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[7]). However, the current funding arrangements also put the social housing sector on vulnerable footing, given the near total reliance on grants as well as on a single funding source, should funding be reduced or eliminated in the future. The government should make it a priority to expand and diversify funding to support the development of social housing; this could take the form of national funding mechanism, discussed in the next section.

4.2.3. A growing mismatch of housing-related responsibilities and resources at municipal level

In addition to the high level of fragmentation of housing responsibilities at national level, there is a considerable and growing mismatch at municipal level between the depth and breadth of the housing-related responsibilities of municipal governments, and their financial and technical capacity. Housing responsibilities of municipal authorities (with the exception of Vilnius, where Vilnius City Housing – the only municipal housing institute in Lithuania – is responsible for these tasks) include:

Managing and expanding the social housing stock;

Managing the municipal housing stock;

Administering the rental compensation scheme; and

Supporting the implementation of the multi-family apartment modernisation programme.

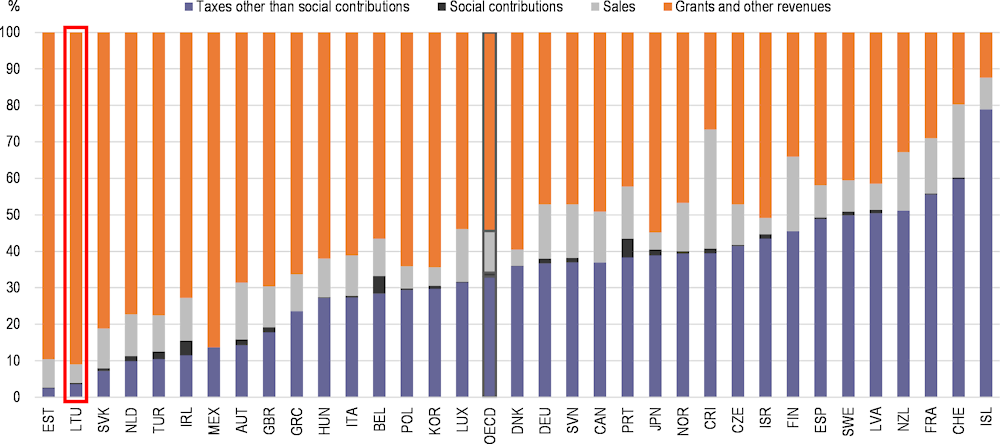

However, despite municipalities’ broad, and growing, range of responsibilities, low levels of fiscal autonomy limit their capacity to act and invest strategically. Scarce financial resources are another constraint, driven by several factors. First, Lithuania is characterised by a highly centralised fiscal framework, which subjects local governments to stringent fiscal restrictions and limits their investment capacity. Municipalities generate a low levels of their own tax revenue and raise comparatively few own financial resources to fund public projects. In terms of fiscal capacity, subnational government revenue in Lithuania represented less than 9% of GDP and 25% of public revenue in 2019, well below the OECD average of 16% and 42%, respectively (OECD, 2021[4]).

Second, municipalities rely heavily on central government assistance and EU funds to cover their responsibilities in domains such as housing, education and social welfare. In 2021, grants and subsidies made up over 90% of municipalities’ total revenue in Lithuania; this is well above the OECD average of around 54% (OECD, 2022[9]). Local governments in Lithuania recorded the highest reliance on grants among all OECD countries in 2021 (Figure 4.3). The share of revenues that could be freely spent by local governments (calculated as the sum of own taxes, fees and general-purpose grants) represents just over half of local revenues, providing them with very little spending autonomy to prioritise spending and reallocate funds. Moreover, their reliance on national and EU assistance for local and regional investment (especially earmarked intergovernmental grants) means that they have limited capacity to plan investment, as intergovernmental grants are volatile and not supported by medium-term commitments from central government. This is also unlikely to be sustainable in the long term, given that EU structural funds are expected to decrease over time as the country develops and will be concentrated on narrower policy objectives. Further, a dependence on sectoral earmarked grants for local public investment is a fragmented approach, which often misses opportunities for investment complementarity between sectors, resulting in sub-optimal regional development outcomes. To attract residents, for instance, housing improvements must be accompanied by appropriate investments in transport infrastructure (OECD, 2021[10]).

Figure 4.3. Composition of local government revenues across OECD countries

Note: Data refer to 2021 (provisional values included), except for Chile, Costa Rica, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Türkiye, and the OECD average, where data refer to 2020. No data are available for Australia, Chile, Colombia, and the United States.

Source: Calculations based on (OECD, 2022[9]), Government at a Glance – yearly updates, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=GOV.

Third, only a small fraction of municipal revenue comes from taxes, with no own-revenue. Taxes and fees represented less than 4% of total municipal revenue in Lithuania in 2021, compared to an OECD average of over 33% (OECD, 2022[9]). In addition to a much smaller share of tax revenue relative to other countries, the vast majority of tax revenue in Lithuanian municipalities consists of immovable property and land taxes, which local governments can levy within pre‑defined limits. Under the Lithuanian self-employment business certificate regime, there is a fixed personal income tax (PIT) amount set by the municipalities and PIT revenues from business certificates are allocated to municipality budgets. By contrast, all other PIT regulation related to other self-employment and employment is set by the State. Overall, Lithuanian municipalities do not generate any significant own-revenue, which is the case in just four other OECD countries: Ireland, Sweden, Chile and Colombia.

Fourth, municipal resources have long been constrained by stringent rules that limit their ability to borrow for investment purposes, to produce sufficient revenues to repay loans, or to develop projects that could attract lenders. Recent reforms to housing support schemes risk exacerbating the mismatch between municipal financial needs and available resources in coming years, as local authorities will be tasked with taking on additional responsibilities, with no adjustment foreseen in financial or human resources. In 2024, the government plans to transfer part of the financial responsibility for the rental compensation scheme from the central government to municipal authorities (Chapter 3). In addition, large regional disparities, mounting urbanisation and ageing pressures, as well as National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) measures, which are all projected to increase local investment demands, may exacerbate the mismatch. In addition, European co-funding, upon which municipalities are highly dependent, is likely to shrink over the next few years (OECD, 2021[10]). As a step forward, in January 2023, a constitutional law that provides for a flexibility rule for the annual budgeting of municipalities entered into force. Following the Fiscal Agreement Nr.XII‑1289 in Lithuania, municipalities may deduct appropriations from state budget grants and support by the European Union and other international financial support from the municipal debt ceiling of 60% measured relative to municipalities’ personal income tax budget revenue (75% for the city of Vilnius). It also allows municipalities to keep unused budget transfers, rather than returning them to the central government.

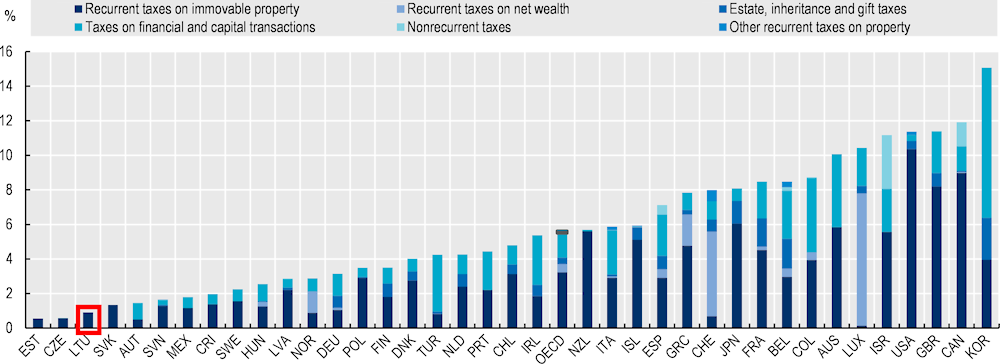

Finally, the property tax regime – which is the main source of municipal tax revenue – is poorly exploited. Good practices in fiscal federalism in OECD countries usually assign property taxes exclusively to the local level, as these tend to be the most stable tax base. This is the case in Lithuania, where municipal tax revenue primarily consists of two property taxes (tax on immovable property and the tax on land from households, i.e. around 0.2% of GDP). Since 2013, municipalities are able to set the rates of the tax on immovable property and of the tax on land, within predefined limits set by law (or decisions from central authorities), while other tax rates are set at the central level. Nevertheless, Lithuania continues to have one of the lowest rates of property taxation in the OECD, at roughly 0.3% of GDP in 2020 (compared to around 1.8% of GDP on average across the OECD), despite separate land and building taxes and a progressive scale for the buildings tax. On average across OECD countries, property taxes represent over 5% of total tax revenues, yet account for around 1% in Lithuania (Figure 4.4) (OECD, 2021[11]). In addition, empirical OECD analysis concluded that recurrent taxes on immovable property, in particular when owned by households, were the least damaging tax for long-run economic growth, compared to consumption taxes, personal income taxes and corporate income taxes (Johansson, 2008[12]). Further, the tax-exempt threshold value is still very high in Lithuania from an international perspective, as a reflection of the long-standing perception of property tax as a “luxury tax.” This remains true even if Lithuania cut the tax-exempt threshold for non-commercial property from EUR 220 000 to EUR 150 000 in 2020, which is still significant (OECD, 2021[13]), although a step in the right direction (OECD, Forthcoming[14]). Publicly-owned property (state property), on the other hand, is not taxed, and municipalities frequently set low land tax rates and partially or completely exclude the building tax, further reducing tax revenues.

Figure 4.4. Property tax revenue as a share of total tax revenues in OECD countries

Note: Data refer to 2021, except for Australia, Japan, Greece and the OECD average, where data refer to 2020.

Source: Revenue Statistics – OECD countries: Comparative tables https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=REV.

In parallel, there are varied levels of technical capacity across Lithuanian municipalities. In its evaluation of the Social Housing Investment Programme, the National Audit Office cited wide variation in approaches to social housing development across municipalities, with uneven financial and technical capacity. Another example is the multi-family apartment modernisation programme, in which nearly three in ten applications (many of which had been prepared by administrators at municipal level) were rejected by the national agency between 2014 and 2018 because they failed to comply with the eligibility requirements or to provide all necessary documentation (Aukščiausioji Audito Institucija, 2020[15]). Capacity is markedly higher in the local administrations of larger cities, namely Vilnius, which operates its own municipal housing institute (Vilnius City Housing) and a local agency to facilitate energy efficiency upgrades to the housing stock.

4.3. Setting a strategic agenda for housing policy

Against this backdrop, there is significant scope for the Lithuanian Government to develop a more integrated, strategic agenda for housing policy. In a first instance, this would call for a lead ministry for housing that would take action to elevate the strategic importance of housing policy and strengthen the analytical basis for housing policy making. Sustained efforts to strengthen municipal capacity will also be needed, given the key role of local authorities in housing policy investment and implementation. A third key priority would be to boost co‑ordinated long-term investments in housing. Experiences from OECD countries can provide inspiration to Lithuania in each of these domains. These steps constitute a road map for policy action for the Lithuanian Government, summarised in Figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5. Key recommendations for setting a strategic agenda for housing policy

4.3.1. Elevate the strategic importance of housing policy and strengthen the analytical basis for policy making

To elevate the strategic importance of housing policy within the government, and more broadly in public discourse, there should be one lead ministry for housing that would be responsible for developing, monitoring and updating a new housing strategy and lead reforms of housing benefits and policies in co‑ordination with the other relevant ministries. There are different options in this respect:

One option could be to establish a new Ministry of Housing, which could take up the housing portfolio from the other ministries; Germany has recently established a dedicated Federal ministry for housing. For this option to work, the new Ministry must have a clear mission and policy remit and be appropriately resourced in terms of both human and financial capacity. Relevant staff from the Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Social Security and Labour (and other ministries) could be transferred to the new ministry.

Alternatively, the housing responsibility and the staff working on housing could be brought together under a dedicated Minister for the housing portfolio, but housed within an existing Ministry (e.g. the Ministry of Environment or Social Security and Labour, which are currently sharing responsibilities for housing). This model has recently been introduced in the Netherlands. within the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations.

Regardless of the final administrative model chosen, it is important that there is a clear housing responsibility within the government and the minister and his/her staff take an active role in leading the development of a new housing strategy and in co‑ordinating the implementation of housing policies and support schemes across relevant ministries and local authorities. Further, given the skills shortages in the construction sector, it will be essential for Ministries with responsibilities relating to labour market regulation, skills development and housing development to work together to develop synergies across policy areas; such an effort could be chaired by the new Ministry for housing.

Focus on a core set of priority areas for action

As a first step, the lead Ministry could identify and coalesce around a handful of priority objectives for housing, and communicate on the importance of tackling these issues, both within the government and with the general public to raise awareness of the issue. The present OECD report, in addition to recent analyses by the Council of Europe Development Bank (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[7]) and others, suggest that housing quality and affordability gaps are likely to be top government priorities. The experience of Latvia, for instance, can provide inspiration: the Latvian Ministry of Economics used data and evidence on the gaps in coverage of the government’s housing programmes to engage in dialogue with parliamentarians, helping to facilitate action on a set of priorities that included improving the regulation of the rental market and supporting the establishment of a dedicated fund to develop new affordable rental housing (OECD, 2020[16]).

Evaluate existing housing support schemes to assess whether they are fit for purpose

Chapter 3 outlines a number of potential reforms to existing schemes that could be considered. Many current housing measures consist of demand-side support, namely the rental compensation scheme (housing benefit) introduced in 2015, the monthly energy and utility allowance and down payment assistance for young households. While well-targeted demand-side supports are likely to continue to be warranted in the current challenging and uncertain context, more attention could be focused on supply-side interventions. This includes, for instance, investments in the social housing supply, which falls well short of demand and suffers from considerable quality gaps; improved incentives to private property owners to lease their dwellings for social purposes; and accelerated efforts to undertake residential renovations, with targeted support to low-income and vulnerable households. Additional avenues for reform that could have significant impacts on housing outcomes (for instance, relating to the tax regime or public land management) would require action from other ministries, as they are outside the responsibility of these two ministries.

Improve data collection efforts to inform decision making and guide housing investment

Collecting data on a range of housing market and policy outcomes is a key tool to inform strategic decisions about where, and to whom, to allocate funding for housing. Lithuania could strengthen evidence‑based policy making, taking inspiration from OECD peers:

In Slovenia, for example, the Priority development areas for the housing supply (PROSO) is a key tool to guide policy action and investment throughout the national territory. The two‑stage model quantifies housing needs in different parts of the country; public investments through the Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia are then obliged to spend 60% of its funds according to the needs identified in the PROSO.

Estonia established a building registry platform in 2016, which is used by all municipalities across the country. It has handled around 32 000 procedures a year and is connected to other databases that provide information on the built environment. The building logbook includes information on building permit applications, construction notification services, energy efficiency ratings, and information on energy usage by utility network operators; it can, upon request, access more data sources as needed. This enables detailed information on the renovation potential across the country and enables priority-setting in the renovation process (Hummel et al., 2022[17]). Building logbooks are being developed and enhanced across European Union member states to serve as a common repository for all relevant building data (Box 4.3) (European Commission, 2020[18]).

Denmark has a comprehensive approach to data collection via its National Housing Fund. The Fund has, over the past decades, established a vast data warehouse to monitor and inform policy decisions. Data collection efforts can be organised in phases: starting first with financial records, followed by data on housing maintenance standards, and finally, more detailed data on economic characteristics and social indicators relating to the tenants (e.g. employment data) and neighbourhood composition. In addition, information management and data collection are facilitated by a common administrative IT system; the national government provides the IT framework that is also used by all municipalities. This reduces the administrative burden and enables more efficient decision-making on new construction sites and the allocation of social housing. A strong evidence base can help Lithuania better identify the need for public intervention in the housing market, ensure that needs are appropriately addressed and make the best use of resources.

Box 4.3. Digital logbooks to facilitate the planning of building renovations

Digital Building Logbooks are part of the European “Renovation Wave” strategy to increase the speed and efficiency of renovations across Europe. Many countries across the European Union have made advances in developing building logbooks, including Portugal (ADENE), Greece (CRES) and Estonia (TREA) (Hummel et al., 2022[17]).

Digital building logbooks are repositories that store a wide variety of data about buildings in an interoperable way that can help in the planning of renovations to increase energy efficiency. Building logbooks combine static and dynamic data about dwellings that enable better co‑operation and information sharing between the construction sector, among building owners and occupants, financial institutions and public authorities (Gómez-Gil, Espinosa-Fernández and López-Mesa, 2022[19]):

Static data include information about the lifecycle of the building, updates on the physical state, renovation and maintenance work that was carried out, as well as administrative data such as plans, technical systems installed, and construction materials used.

Dynamic data in logbooks include real-time energy use, indoor environmental quality, lifecycle emissions and other information that is recorded and stored automatically (European Commission, 2020[18]).

4.3.2. Strengthen capacity in municipalities, as key implementers of housing policy

Measures to strengthen municipal capacity would also support the government’s efforts to make housing policy more effective. Addressing the fiscal and technical capacity gaps will be critical, along with incentives to encourage more strategic use of public resources (including State‑owned land) to advance affordable housing goals.

Address the fiscal gap and encourage more strategic leveraging of public resources, such as land. To strengthen the fiscal capacity of municipalities, policy makers should continue efforts to increase and reorganise municipal own-source revenues. Recent work by the OECD Network on Fiscal Relations, including (Dougherty, Harding and Reschovsky, 2019[20]) and (Phillips, 2020[21]), finds that housing supply elasticities are stronger in countries where subnational governments have more authority over their taxes (tax autonomy) and receive a larger share of property taxes. This suggests that, if Lithuania had a higher degree of subnational government autonomy over their tax base (in particular for property taxes, meaning they can levy and receive a larger portion of these taxes) this could produce a significantly higher housing supply response (OECD, 2021[22]). Recommendations in the OECD 2020 Economic Survey of Lithuania pointed at the need for the government to broaden the land tax base and incentivise municipalities to raise additional property tax revenue, in addition to lowering further the tax-exempt threshold value (OECD, 2020[23]). In line with these recommendations, the government has begun to reform the intergovernmental fiscal system. Reforms include the full assignment of the property tax to the municipalities (OECD, 2020[23]), and increased flexibility in the municipal budgeting rule.

In parallel, rules should guide how municipalities can use the funds, including incentivising municipalities to more strategically leverage state‑owned land for social and affordable housing development (see Chapter 3). While municipalities are currently allowed to leverage State‑owned land for strategic purposes, they do not make use of this opportunity to develop social or affordable housing. Greater use of this prerogative would contribute to increase the local supply of social housing, shortening the long waiting lists and reducing municipal spending on the rent compensation scheme. Additional incentives should be put in place by the national government to encourage municipalities to further utilise this resource.

There is potential to complement fiscal reforms, for instance, by broadening the base of the immovable property tax – currently viewed as a “luxury tax” with little revenue – and following through with plans to move towards a “universal property tax.” Further, Lithuania should pursue plans to raise municipalities’ capacity to borrowing for investment (OECD, 2022[24]). Lithuanian municipalities should make use of the latest adoption of the budgeting flexibility rule to allocate more resources towards growth- and welfare‑enhancing investment projects.

Address the technical capacity gap

To address technical capacity gaps within municipalities, there are several possible areas to consider. The newly created regional councils could contribute to better co‑ordination of supra-local investment projects, but the role of regional councils would need to be complemented by stronger incentives for collaboration and pooling resources and capabilities. Policy makers could incentivise inter-municipal co‑operation in key housing areas. Local authorities report limited co‑ordination of investment projects among municipalities, which hinders economies of scale and scope. Future efforts should aim to further incentivise inter-municipal co‑operation, either by pooling expertise (e.g. shared service centres) or programmes to expand outreach and increase bargaining power to cut spending (e.g. for public-private partnerships). Another opportunity could be to consider establishing municipal- and/or metropolitan-scale agencies. Vilnius is the only municipality with a designated municipal enterprise (Vilnius City Housing), which has strengthened the city’s capacity to complete energy efficiency upgrades to the housing stock. Following Vilnius’ example for housing and modernisation in other large cities (e.g. Kaunas, Klaipėda, Šiauliai) could help increase institutional capacity for housing administration in a few of the larger municipalities.

4.3.3. Boost investment in affordable housing through the establishment of a long-term, sustainable funding mechanism

Given the low levels of investment in housing in Lithuania over the past decades, a sustained effort to boost housing investment will be essential to improve the quality of the existing stock and increase the supply of new affordable and social housing. Yet the current context is challenging, with increased uncertainty that could make it difficult to commit significant public resources to the housing sector. This is compounded by the absence of a single institutional champion for housing policy.

Lithuanian policy makers could aim to establish a dedicated housing fund, following the experience from other countries. The institutional set-up can vary (a new institution or existing funding institutions with additional resources; public body or not-for-profit body). The key idea is that the fund could start with some initial equity, borrow to finance new affordable housing and eventually use a share of rents to finance new affordable housing development.

Lessons from four OECD countries: Developing a long-term funding mechanism for housing

Lithuania could consider developing a special-purpose instrument to mobilise and channel resources towards affordable and social housing. This could help to overcome the contextual and institutional challenges and boost investment in both new housing development as well as the renovation of the existing stock (OECD, 2020[23]). Moreover, such special-purpose funds and funding systems can be a stepping stone towards a more co‑ordinated and strategic approach to housing policy. Effective housing funds can typically serve as a platform to bring together central and local authorities, financing institutions and not-for-profit housing associations towards a common objective.

This section outlines four different approaches to establishing a long-term, self-sustaining funding mechanism for housing, presenting the experiences of Denmark, Austria, the Slovak Republic and Latvia. Each case describes the institutional set up and the funding mechanism. The section then draws some lessons for Lithuania, highlighting a number of key features that should be considered by policy makers.

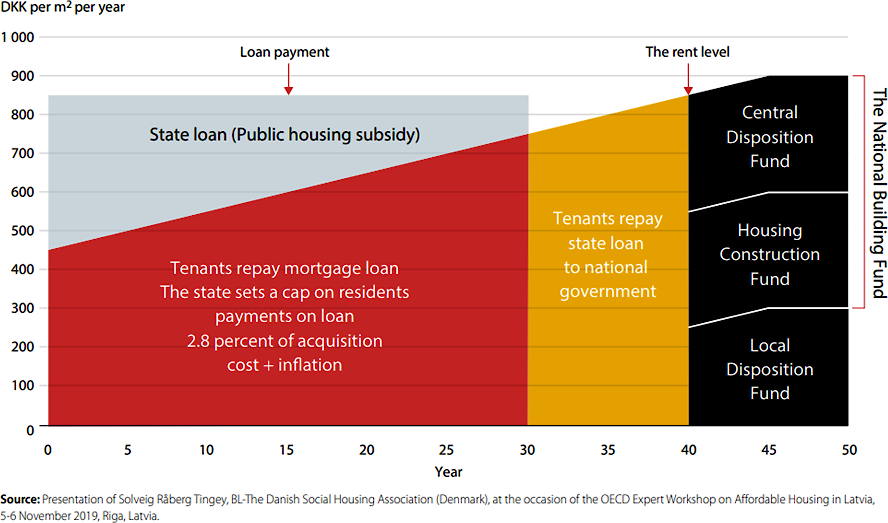

Denmark’s National Building Fund

Denmark’s the National Building Fund was created in 1967 and is a key pillar of the national model to provide social and affordable housing, which is largely implemented by housing associations. The Fund operates in and contributed to the development of a housing market that is significantly different from that in Lithuania. In Denmark, social rental housing accounts for 21% of all dwellings, one of the largest shares in the OECD. Approximately 49% of all households in Denmark live in rental dwellings (as of 2020) (OECD, 2022[1]). Despite these differences with Lithuania, the institutional set-up (a self-governing body under state supervision with a strong role for municipalities), as well as the funding model (self-funding over the long-term) could provide some inspiration for the design of a revolving fund in Lithuania.

Institutional set-up: The National Building Fund is a self-governing institution established by housing associations with the purpose of promoting the self-financing of housing construction, renovations, improvements and neighbourhood amenities. Funding is based on a share of tenants’ rents, without the need for direct public funding. The Fund is managed by a board of nine members, including representatives from housing organisations, tenants and the two largest municipalities in Denmark (Copenhagen and Aarhus). The budget of the Fund must be approved by the housing minister. An independent secretariat manages the Fund.

The national government establishes the regulatory framework for the social housing sector (rent setting, cap on building costs, financing modalities), the role of the different actors (national government, municipalities, housing associations, tenants, private financial institutions), and the Fund’s spending priorities. The national government also provides a state guarantee on mortgage loans and state loans to the Fund (as long as the assets of the Fund are negative). Municipalities are responsible for the implementation of housing guidelines through municipal plans, and for planning new social housing development. Housing associations – not-for-profit organisations – manage social housing developments, manage the waiting list and initiate new housing projects with the approval of municipalities.

The development of a fiscal master plan, agreed with municipalities, is the precondition to access support from the Fund. Every fourth year, a housing agreement negotiated in Parliament determines how much the Fund can finance. Each housing association contributes to and can borrow from the Fund, which supports a wide range of activities, including renovation of the existing housing stock, social and preventive investments in vulnerable areas, including the development of social master plans that are co-financed with municipalities to support interventions related to security and well-being, crime prevention, education and employment, and parental support.

The Secretariat of the Fund collects various data on the social housing sector and social housing tenants. In particular, the Fund collects all financial statements by entities in social housing. These are universally available on the Fund’s website, together with raw averages and benchmark values on individual accounts. In addition, to monitor rent levels, the Fund maintains a rental database, detailing the rents (and composition of rents) of every social housing unit in Denmark. The Fund also has access to the detailed databases operated by Statistics Denmark, where economists monitor the tenants in the sector, relating to employment levels, education and income, for instance.

Funding model: The initial capital of the Fund was built on contributions from a gradual rent increase in the social housing sector determined by a political agreement in 1966. Currently, funding is based on a share of tenants’ rents (amounting to 2.8% annually of the total acquisition cost of the property), in addition to housing associations’ contributions to mortgage loans, amounting altogether to approximately 3% of the property development cost. Rental payments are adjusted once a year for the first 20 years after loan take‑up, with the increase in the net price index or, if this has risen less, the private sector average earnings index. After the first 20 years, the amount is adjusted by 75% of the increase in these indices. Adjustments are made for the last time in the 45th year following the loan take‑up, after which it is maintained at the reached nominal level.

The Fund is a linchpin of a funding model that largely relies on commercial loans from mortgage institutions. Commercial loans finance 86‑90% of the investment cost. The loan (30‑year) is taken by the housing association to finance each housing development. State subsidies are provided to support the repayment of these loans. Municipalities pay a portion of the cost upfront in the form of an interest-free and instalment-free 50‑year loan, which covers 8‑12% of the investment costs. Tenants provide an upfront payment when they take up residence, which covers 2% of investment costs.

When the mortgage loans for the construction of the dwelling have been repaid, rental payments continue to contribute to the repayment of the state loan. However, tenants do not experience any reduction in their rent after the loans are repaid: they continue to pay rent at the same level, with two‑thirds of the rental revenue going to the Fund as savings. Tenant contributions enable the Fund to finance renovations and developments of the existing housing stock. The contributions also cover the operating costs of the Fund, which consist of general administrative expenses (for example, salaries of the employees) (Figure 4.6).

Figure 4.6. Denmark’s National Building Fund financing model

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2020[16]), Policy Actions for Affordable Housing in Latvia, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=137_137572-i6cxds8act&title=Policy-Actions-for-Affordable-Housing-in-Latvia.

Rent levels do not depend on household income, and there are no income criteria to apply for social housing. Public housing subsidies are given to all types of rental housing in Denmark and consist of individual allowances, in the form of a housing benefit scheme (boligydelse) and a rent rebate scheme (boligsikring). These allowances are financed by municipalities, which are then refunded to a large extent by the national government. The amount of the housing benefit depends on the rent level, excluding costs relating to electricity, water and heating, the size of the rental dwelling, household size and composition, the income and assets of the tenants, and, whether the tenant is elderly and/or a person with disability. Given that the number of housing developments that have paid off their mortgages is increasing, in the coming years the Fund will have generated a surplus to dedicate towards physical and social modernisation programmes decided upon in the sector.

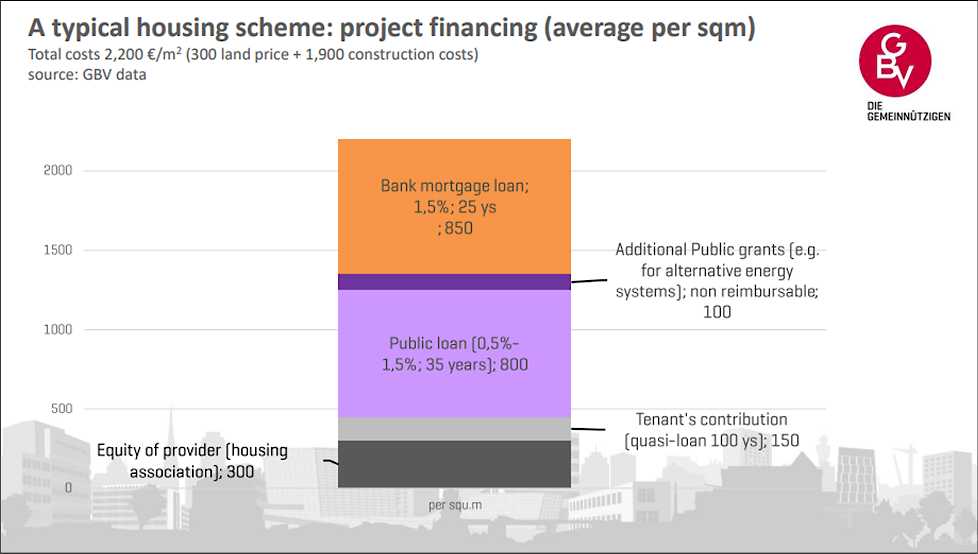

Austria’s affordable and social housing model

Contrary to Denmark, Austria does not have a dedicated housing fund. Rather, the provision of affordable and social housing relies on limited-profit housing associations that operate revolving funds under the supervision, and with the steering of, the federal, regional and municipal governments. Limited-profit housing associations provide new construction, renovation of the existing stock as well as management of the municipal housing stock. As in the case of Denmark, the Austrian housing market is markedly different from the Lithuanian housing market. Approximately 44% of Austrian households live in rental dwellings (as of 2020). Affordable and social rental housing accounts for 24% of the total housing stock in 2020 (OECD, 2022[1]). Austria’s funding mechanism and the role of limited-profit housing associations provide interesting insights for Lithuania.

Institutional set-up: Affordable and social housing in Austria is provided by both local governments (municipalities) and limited-profit housing associations (LPHA). LPHA account for more than two‑thirds of the social and affordable housing stock, while local authorities account for the remainder. LPHA are a distinctive third sector in the housing market; they are neither state‑owned nor profit-driven. They are independent institutions, owned by local public authorities, charity organisations, parties, unions, companies, the financing industry or private persons. Their main activities consists of providing basic housing, encouraging property ownership, promoting rental housing, improving housing quality, and advancing barrier-free accessibility and climate policy goals.

The federal and regional governments set the housing policy priorities, provide housing loans and subsidies and are responsible for monitoring the LPHA. Municipalities are responsible of local planning permissions and managing available land.

Funding model: Projects developed by LPHA are typically financed by multiple sources. LPHA usually finance around 10‑20% of a new project from their own equity. The equity of LPHA increases mainly from two sources: i) the surpluses of the older housing stock for which loans have been repaid (LPHA continue to charge “basic rent” of around EUR 1.8/m2 to tenants after the repayment of loans) and ii) the 3.5% interest on LPHA equity invested.

A key feature of the financing system of the Austrian LPHA is the role of tenants. Tenants contribute to the financing of LPHA activities (3‑7% on average) by granting a quasi-loan to the association, in the form of a down payment, which cannot exceed 12.5% of the total construction costs and a share in land costs. This amount is returned to tenants at the time of moving out, depreciated by 1% for each year of occupation of the dwelling. Low-income households that cannot afford to pay the initial down payment can receive a public loan with 1% interest.

In addition to LPHA own equity, additional funding resources come from public and commercial loans, which represent, respectively, around 36% and 39% of overall funding. Public loans are regulated and provided by the federal provinces and are conditional on upholding the rules established in the federal subsidy laws. They have favourable financing terms, with interest rates between 0.5 and 1.5% and 35 years of maturity.

Given the high credit worthiness of LPHA, due to co-financing with the State and their clear ownership structure, commercial bank loans are also granted at favourable terms, with interest rates of 1.5% and 25‑years’ maturity on average (Figure 4.7). An important source of commercial funding in Austria is provided through Housing Construction Convertible Bonds (HCCB), which are issued by special-purpose banks (Wohnbaubanken). There are six Housing Construction Banks active in Austria since 1994 (subsidiaries of major Austrian banks). Their main task is to provide medium- and long-term low-interest loans with 20‑30 years maturity to affordable housing developers. The bonds benefit from tax advantages (e.g. a waiver for capital income tax on the first 4% of HCCB coupon rate for investment in the sector; a deduction of the cost of bonds purchased from income for tax purposes). The yields on HCCB are 1% lower than commercial loans and combined with the tax advantages it makes these long-term bonds attractive, even without a government guarantee.

Figure 4.7. Project financing for a typical housing project by housing associations in Austria

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2020[16]), Policy Actions for Affordable Housing in Latvia, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=137_137572-i6cxds8act&title=Policy-Actions-for-Affordable-Housing-in-Latvia.

The Slovak Republic’s State Housing Development Fund

The Slovak Republic’s State Housing Development Fund was established in 1996 as a revolving fund to finance the government’s priorities defined in the State Housing Policy Concept. It is an independent entity supervised by the Ministry of Transport and Construction. The Fund was originally financed exclusively from the state budget, with the intention that it would become self-sustaining over time. The Fund continues to draw on small levels of government funding, together with some European structural funding, but is now primarily self-sustaining via the repayments on the loans provided by the Fund. The Fund operates in a housing context that shares similarities with the Lithuanian housing market: most households own their dwelling outright, but the housing stock is relatively poor quality and fewer than 8% of households live in rental dwellings (as of 2022) (OECD, 2022[1]). The Fund supports the maintenance and refurbishing of existing dwellings and has become one of the main implementing instruments of the Slovak Republic’s housing strategy.

Institutional set-up: The Fund is administered by the Ministry of Transport and Construction and headed by a Director General appointed by the ministry. The Fund provides favourable long-term loans, financing up to 100% of acquisition costs for a term of up to 40 years with differentiated interest rates ranging from 0% to 2%. Eligible households can also access the loans: for example, young couples and single parents have access to maximum 75% of the acquisition cost or the construction (up to EUR 100 000). Newly married couples and households in which a member has a severe disability may access up to 100% of the acquisition cost or the construction (up to EUR 120 000). Municipalities, self-governing regions, non-profit organisations and other bodies that operate in cities or villages with a population of over 2000 can borrow from the Fund to build, purchase or upgrade rental apartments, or build or purchase equipment or land related to the acquisition of rental apartments.

To complement the Fund, a housing development programme, introduced in 1998, provides subsidies to municipalities to finance the construction of social rental housing, infrastructure around new housing developments, and improvements to existing buildings. Depending on the building features and quality standards, subsidies to municipalities can cover between 40 and 75% of the acquisition costs. Subsidies can be combined with loans for the State Housing Development Fund.

Funding model: The State’s initial investment in the Fund has allowed the Fund to become self-funded through the repayment of its loans. In 2020 revenues from repayment of principal from loans amounted to approximately EUR 140 million, up by EUR 10 million compared to 2019. The loan repayments and interest payments are reinvested in new loans. In 2020, the Fund’s equity amounted to EUR 2.5 billion (State Housing Development Fund (Republic of Slovakia), 2020[25]).

The Fund has also been effective in funding maintenance and refurbishments. As of 2016, approximately half of the country’s dwelling stock had been refurbished. Of those, half (or 25% of the total housing stock) have been refurbished with the support of the Fund (Table 4.4). The Ministry of Transport and Construction has been very active in engaging with housing managers and association of owners to explain the opportunities offered by the Fund and the possibility of using the support to finance interventions aimed at solving serious technical problems like failures in the water pipe system, roofing, etc. Financing is provided after the presentation of a technical assessment, which has further contributed to better understand the state of the housing stock and raise awareness of the need to intervene.

Table 4.4. Refurbishments of the housing stock in the Slovak Republic

|

|

Dwellings in residential buildings |

Family houses |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2011 Census |

931 605 |

1 008 795 |

1 940 400 |

|

Refurbished dwellings |

543 406 |

378 271 |

921 677 |

|

Share of refurbishments |

58.3% |

37.5% |

47.5% |

Source: (OECD, 2020[16]), Policy Actions for Affordable Housing in Latvia, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=137_137572-i6cxds8act&title=Policy-Actions-for-Affordable-Housing-in-Latvia.

Since 2013, the Fund has also accessed EU structural funds to finance renovation and energy efficiency of buildings. As part of the Integrated Regional Operational Programme (Objective 4.1), in 2018 the Fund created a dedicated funding facility co-financed by EU funds (85%) and the Fund’s own funding (15%) for a total amount of approximately EUR 160 million. The facility finances renovation of existing apartment buildings in order to enable their systematic renovation. Projects need to improve the energy performance of buildings and reduce energy needs to the level of low-energy, ultra-low-energy and near-zero energy (State Housing Development Fund (Republic of Slovakia), 2020[25]).

Latvia’s Housing Affordability Fund

Latvia and Lithuania share similar housing challenges and features of the housing market. Latvia also has a large share of households owning their dwelling (69% of outright owners in 2019) and a small rental market (12% of households living in rental accommodation in 2019). The quality of the existing housing stock is also an issue, and the social housing stock is small (2% of the overall housing stock). Drawing on the lessons of some of the countries presented above, in July 2022 Latvia approved new legislation to set up a Housing Affordability Fund to channel investment into affordable rental housing. The new Housing Affordability Fund will be designed as a revolving fund in which rents paid by tenants are perpetually reinvested in the Fund to finance the construction of new affordable rental housing outside Riga. The key features of the Fund are outlined below.

Institutional set-up: The EU Recovery and Resilience Facility is financing the establishment of the Housing Affordability Fund to support the construction of new affordable rental housing in Latvia. The Housing Affordability Fund will be used to finance the construction of new affordable rental housing outside Riga that meets minimum construction, environmental and energy efficiency requirements, and which are rented at a below-market price to households that meet income thresholds requirements.

The Ministry of Economics is responsible for defining and steering housing policy and is responsible for the establishment of the Fund. Altum, Latvia’s development finance institution, will administer the Fund and select housing projects to be financed, as well as monitor the use and repayment of the loans. Municipalities will be managing the applications of eligible tenants and assign the units. The State public asset manager will monitor the activities of the Fund once the affordable units will be in use, verifying the contributions of the tenants into the Fund and authorising any use of the Fund’s resources to finance maintenance.

Funding model: Initial funding to establish the Housing Affordability Fund will come from the Latvian Recovery and Resilience Plan, for an amount of EUR 42.9 million (European Commission, 2021[26]). Additional resources will come from State loans and/or commercial loans. Over time, additional sources would contribute to the fund, including, in a first phase, repayment of the principal by the beneficiaries of the financing mechanism (e.g. the real estate developers); and following the repayment of the loan issued by Altum, contributions from the monthly rental income of the affordable rental housing (50% of the rental income), to be paid by the owners of the affordable rental apartments (e.g. the developers) indefinitely.

Key features to consider in establishing up a housing funding mechanism in Lithuania

Lithuania could build on these features to consider the establishment of a funding mechanism to channel resources towards affordable and social housing. The approaches of Austria, Denmark, the Slovak Republic and Latvia are not mutually exclusive and offer elements that could be adapted to fit the needs of Lithuania. Issues to be considered include:

Objectives and strategy: A first step will be to define the scope and activities to be supported through such a fund. Both maintenance and new construction can be activities that the fund could potentially finance. The definition of the scope and mission of the fund could also serve as a basis for the defining housing priorities and provide a concrete tool for advancing on long-term housing objectives. Keeping the objectives sufficiently broad to cover issues related to quality, access and affordability could be a way to attract more easily funding.