This chapter provides a comparative assessment of the management and monitoring of revolving fund schemes for affordable housing in Latvia and four peer countries. It outlines the main features of the approach in each country and proposes a series of recommendations and good practice cases for consideration by the Latvian authorities to ensure that the Fund contributes to the production and allocation of affordable housing, and that effective monitoring and control mechanisms of the Fund are in place to produce measurable results over time.

Strengthening Latvia’s Housing Affordability Fund

5. Operating a revolving fund scheme for affordable housing in Latvia

Abstract

Effective management and monitoring of affordable housing finance schemes helps to ensure that:

the dwellings produced through the scheme effectively target and are allocated to households in need of support;

rent levels balance the need to sufficiently contribute to the costs of developing and operating the dwelling, while also remaining affordable to households;

the dwellings produced through the scheme are well managed and maintained;

effective systems are in place to monitor progress and ensure compliance, including by collecting data that help track progress and adjust course; and

there are mechanisms to address tenants’ demands and possible complaints.

In line with these objectives, this chapter assesses key dimensions relating to the effective management and monitoring of affordable housing finance schemes, including:

the management of the affordable units, encompassing the eligibility criteria, allocation of the units, rent setting, dwelling management and maintenance; and

the monitoring and control of the financing scheme itself, including data collection, auditing and mechanisms to ensure compliance with the rules and regulations, measure results over time, and assess impact over time.

For each of these dimensions, the chapter first provides a comparative snapshot, highlighting where Latvia stands in comparison with peer countries, and then builds on the international practices to point at policy recommendations of relevance for Latvia.

5.1. Management of the affordable rental dwellings

5.1.1. Where does Latvia stand in comparison to peer countries?

Table 5.1 provides a comparative snapshot of the decisions relating to the management of the affordable dwellings produced through the funding scheme.

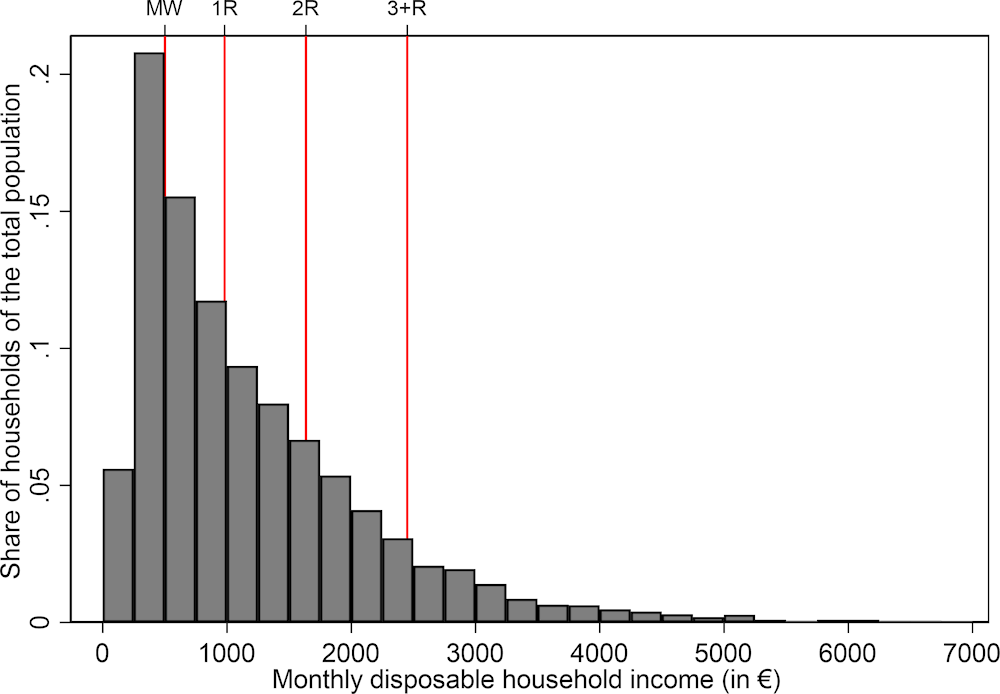

In all countries covered except Denmark, eligibility criteria for affordable units generally depend on maximum household income levels. In Latvia, Austria and the Netherlands, income thresholds are set high enough to enable a relatively large share of the population – including middle‑income households – to access the dwellings. Given that income levels are highly concentrated at the lower end of the distribution in Latvia, the income thresholds established in the Regulation enable roughly half of Latvian households to be eligible for one‑room dwellings, with an even greater share of households eligible for larger dwellings. By comparison, around 80% of the population is eligible for social housing in Austria, compared to just under half in the Netherlands.

The target beneficiaries of the affordable dwellings produced through the Housing Affordability Fund are broadly defined in Latvia’s Regulation as “households who cannot afford housing on market terms.” The relatively high income ceilings established in the Regulation facilitate access to middle‑income households – the “missing middle” (see (OECD, 2020[1])). OECD estimates that roughly half of Latvian households would be eligible to lease one‑bedroom flats produced through the Fund, according to their income levels (Figure 5.1). Income thresholds are defined by the national government in all countries except Austria (where they vary across municipalities); in the Netherlands and Latvia, income thresholds are adjusted annually. In Slovenia, there are relatively low-income thresholds, in addition to other criteria, for non-profit dwellings; in general, for cost-rent dwellings there are no income thresholds but eligibility criteria vary according to the housing project and the target beneficiaries. There are no income criteria to access social housing in Denmark; in principle, all individuals over 15 years old are eligible to apply.

Figure 5.1. Approximately half of Latvian households would be eligible for one‑room apartments produced through the Housing Affordability Fund

Note: Minimum wage is equivalent to EUR 500; income ceilings to determine eligibility for dwellings produced through the fund cannot exceed EUR 980 for a one‑room apartment; EUR 1 635 for a two‑room apartment; and EUR 2 450 for an apartment of three or more rooms. The distribution of monthly disposable income is based on national data. According to the Regulation, all households that meet the income criteria, regardless of their current place of residence, are eligible to apply for the affordable rental dwellings produced through the fund; however, there are geographic limits on the location of the construction projects/dwellings to be produced through the fund (see Section 2).

Source: OECD calculations, based on (Cabinet of Ministers (Latvia), 2022[2]), Regulation No 459, Rules on support for the construction of residential rental housing under the European Union’s Recovery and Resilience Mechanism Plan, reform and investment axis 3.1 “Regional policy” 3.1.1.4.i. under the investment “Establishment of a financing fund for the construction of low-rent housing,” https://likumi.lv/ta/id/334085-noteikumi-par-atbalstu-dzivojamo-ires-maju-buvniecibai-eiropas-savienibas-atveselosanas-un-noturibas-mehanisma-plana-3-1.

In peer countries, in addition to income ceilings, other eligibility criteria apply. This includes, for instance, requiring that tenants have citizenship or permanent residency in the country (Austria; non-profit dwellings in Slovenia); already work or live in the municipality or region in which they are applying for a dwelling (Vienna, Austria; non-profit dwellings in Slovenia); and/or meet some criteria relating to their current employment or recent employment history (non-profit dwellings in Slovenia). In the Netherlands, the Housing Act specifies that households living or working in the municipality are prioritised in the allocation of social housing.

In terms of the rent-setting approach, Austria and Denmark rely on a cost-based approach, where rent levels should be roughly equivalent to the costs incurred to develop, operate and maintain the dwelling. Slovenia relies on a modified cost-based approach for cost-rental dwellings, which is adjusted based on further considerations (e.g. location factors, tenant characteristics, funding source of the project). The Netherlands and Slovenia (for non-profit dwellings) use a utilities-based approach, where rent levels are calculated according to various characteristics relating to the size, quality and location of the dwelling. In Latvia, rent levels are only partially cost-based, given that they include a fixed monthly rent of up to EUR 5.87/m2, in addition to costs relating to the real estate tax, insurance costs, utilities and charges, and a monthly fee to cover future repairs; tenants must also pay a security deposit equivalent to two‑months’ rent.

In all countries, a building manager is responsible for the day-to-day operations of the affordable units. The building manager will be selected by the housing developer in Latvia. In Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands, housing associations manage the affordable dwellings; in Slovenia, the owners of the dwellings are responsible for the day-to-day management.

To finance dwelling maintenance and improvements costs, in addition to the monthly rent payments, tenants in Latvia contribute to charges relating to the management and maintenance of the dwelling, as well as a monthly fee, to cover building improvements. Tenant contributions to maintenance are common in peer countries, though the calculation and management of these fees vary. In Latvia, the monthly fee is equivalent to EUR 0.25/m2, compared to a progressively increasing amount in Austria (EUR 0.50/m2 in the first years after construction and then increasing to EUR 2/m2 thereafter). An important difference, however, is that in Latvia, tenant contributions to building improvements are allocated into a savings fund that is specific to each developer and/or building manager; in Denmark and the Netherlands, such contributions are mutualised into a common fund for all affordable dwellings. In Slovenia, property owners may pay into the reserve fund, but tenants do not.

Table 5.1. Comparative snapshot: Managing the affordable rental dwellings produced through the revolving fund scheme

|

|

Latvia |

Austria |

Denmark |

The Netherlands |

Slovenia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Eligibility criteria for affordable rental units |

Eligibility for affordable units is based on income. Eligible tenants’ total monthly average net income in the previous tax year cannot exceed:

Eligibility criteria are outlined in the Regulation on support for the construction of affordable rental houses and will be adjusted annually in line with inflation. |

Eligibility for affordable units is based on income. Income ceilings vary by municipality, but are relatively high to encourage social mixing (roughly 80% of all households are eligible for social/affordable housing) Additionally, some regional subsidy programmes have special schemes to define eligibility (e.g. for example, setting age limits for moving in, lower tenancy contribution, smaller flats depending on household size) |

All individuals aged 15 and over are eligible for social housing in principle, regardless of income. Nevertheless, in practice, social housing residents record, on average, lower income levels and higher unemployment rates. This is partly because vulnerable groups have a general priority, but also because legal restrictions on the construction price and size of the dwellings influence demand. |

Eligibility for affordable units is based on income. The relatively high income limits mean that social housing is available to a rather broad segment of the population (just under half of the population is currently eligible for social housing). As of 2023, housing associations must lease vacant social dwellings as follows:

Household income ceilings are adjusted annually (indexation only). |

Eligibility depends on the type of affordable dwelling, as defined in the Housing Act: For non-profit housing dwellings, eligibility is based on income and citizenship.a Household income of the previous calendar year must not exceed the following percentage of the average national net salary (adjusted according to household size):

For cost-rental dwellings, in principle, all residents of Slovenia are eligible, regardless of income or citizenship; however, specific criteria may be established depending on the target group of the project (e.g. elderly, young people). |

|

Queue of eligible tenants |

Allocation of units via a waiting list. Municipalities manage the queue in their administrative area, including for units developed by housing co‑operatives (if applicable). Dwellings are allocated by the developer according to the waiting list. Dwellings developed by housing co‑operatives can be rented out only to their members. Municipalities may identify priority groups. |

Municipalities and LPHA allocate rights to affordable/social housing, according to waiting lists:

|

Dwellings are allocated on the basis of a waiting list that is open to all housing applicants. Waiting lists are generally managed by housing associations.

|

Dwellings are primarily allocated via waiting lists, in combination with choice‑based letting systems. Choice‑based letting systems enable eligible households to choose social dwellings that meet their needs, based on a public listing of available vacancies. The dwelling is let to the house seeker with the longest waiting time. The waiting list and choice‑based letting systems are managed by the housing associations or by parties designated to manage the process on behalf of housing associations. An exception is for vulnerable groups (people with disabilities, disadvantaged groups, the homeless or refugees). They can become priority cases when they meet the criteria for priority which are identified in the local housing regulation, jointly determined by criteria from the national government. |

Allocation of dwellings depends on the type of dwelling.

|

|

Rent setting |

Rent levels must not exceed a fixed amount per square metre (EUR 5.87/m2) per month. Rent increases are permitted once every year in line with annual national inflation. In addition to the rent, the tenant pays: real estate tax and insurance costs; utilities and charges (e.g. management expenses); a monthly fee (EUR 0.25/m2) for repairs; a security deposit equivalent to two months’ rent. |

Rent levels are calculated depending on the status of the loan, declining once the loan has been repaid:

In 2019, the average (net) rent of a Housing Association dwelling was EUR 5/m2 (EUR 6/m2 for new construction). This includes the contribution to the maintenance and improvement fund, but excludes service charges (e.g. rubbish collection, cleaning of building, etc.), which may vary over time. The average (net) rent of a Housing Association dwelling is 23% below market rent (or even greater for new buildings). |

Rent levels are calculated according to the rental balance principle: housing associations’ income (rental payments) and expenditures (operating, maintenance and capital costs) must balance out. There is an upper limit on the cost of new non-profit housing construction on a square metre basis, helping to limit rent levels. Maximum rent levels vary depending on housing type and region; changes to the limits are decided by the national government and prices adjusted for inflation each year. The calculation of rent levels varies depending on the status of the loan repayment:

|

There are maximum rent ceilings for social dwellings, which depend on the quality of the housing. A rent points system is used to calculate maximum rent for a dwelling, drawing on:

|

Rent-setting depends on the type of dwelling: Non-profit rents are calculated based on a formula that accounts for several factorsb:

This yields a number of points for each dwelling, which is multiplied by a factor (of EUR 3.5 per point starting 1 April 2023), to determine the maximum allowable rent for each dwelling. This factor is adjusted annually to correct for changes in the consumer price index.c Cost-rents are calculated based on the real costs of the project, in addition to considerations relating to the dwelling location and potential tenants, as well as the funding sources used to produce the dwelling. |

|

Management of the units |

A building manager – appointed by the housing developer (the developer can also self-appoint as building manager)– is responsible for the day-to-day operations and maintenance of the affordable rental units. The building manager must be selected through an open selection procedure every five years. |

Limited-profit housing associations manage the dwellings (including dwellings that they do not own, for which owners pay service charges). The owners may collectively decide to change the housing management. |

Housing associations are responsible for the daily operations of the estates. |

Housing associations manage social dwellings. |

Owners of the non-profit dwellings are responsible for the building maintenance. |

|

Maintenance and improvements |

In addition to monthly rent payments, tenants in the affordable rental units must also make monthly payments into a savings fund (EUR 0.25/m2), which is opened in a payment institution and specific to the real estate developer, to finance building improvements. Tenants are also required to pay maintenance management expenses (e.g. relating to visual inspection, technical inspection, as well as everyday maintenance and including the remuneration of the maintenance manager). |

Housing associations charge a monthly cost-based maintenance fee, which starts at EUR 0.50/m2 in the first years after construction and goes up to EUR 2/m2. This fee feeds the maintenance and improvement fund, which is a separate revolving fund dedicated to the renovation of buildings. It ensures that the quality of housing is maintained over time (day-to-day maintenance) and that it abides with the strict regulations on the quality of the buildings (both social and environmental, e.g. installation of PV panels). In addition, tenants pay rubbish collection, cleaning of building, etc.), which may vary over time. |

Tenants’ rent covers operating and maintenance costs related to their own dwelling/social housing project. Dwelling improvements can be financed through the Fund. |

Maintenance of the housing stocks is part of the housing associations’ scope of activities. This is an operational activity and must be paid from the rental income. Conversely, home improvements (e.g. making homes sustainable) are an investment for which WSW guaranteed loans are possible. |

Owners of apartments are responsible for maintenance costs and for ensuring unchanged market value of the apartment. Owners are also required to insure apartments and shared areas of multi‑apartment buildings. Maintenance and insurance costs may not exceed 1.11% of the apartment value (for apartments built less than 60 years ago) or 1.81% of the value of the apartment (for apartments built over 60 years ago). |

Note: a) In parallel, the subsidy for households living in non-profit rental apartments is calculated according to the difference between the rent and the minimum income threshold. The monthly rent is reduced by the calculated subsidy amount, and the apartment owner is reimbursed by the municipality. A similar subsidy exists for the payment of market rents for eligible households. b) A proposed reform to this model would transition to a system of cost-rent, with a means-tested housing allowance granted to low-income households to offset the increase in rents. c) Tenants and owners may request that the municipality re‑calculates the value of the apartment and thus the maximum allowable rent amount, according to Article 120 of the Housing Act. The municipal administrative body can classify rent levels as extortionate if they exceed the average market rent in the municipality by 50% for a similar category of dwelling, location, and equipment.

5.1.2. Recommendations for Latvia based on peer practices

Policy Action 12: Monitor the production, allocation and affordability of the units produced through the Fund

In the first phase, the rent-setting calculations of dwellings produced through the Fund are designed such that the dwellings are likely to support the unmet housing needs of middle‑income households – the “missing middle” identified in (OECD, 2020[1]). Many lower-income households would require additional financial support (such as the monthly income‑tested housing allowance) for the units to be reasonably affordable (measured in terms of the share of household income dedicated to housing costs). Further, in the initial phase, the Fund aims to increase the supply of affordable rental housing in the regions (outside Riga and surrounding municipalities), even though all households that meet the income eligibility requirements are eligible to live in the new dwellings, regardless of their current place of residence. Refer to Annex 5.A for a description of the housing affordability simulation undertaken by the OECD.

Over time, however, there is an opportunity for the Fund to contribute to social mixing objectives by ensuring that dwellings are accessible to a range of low- and middle‑income households (to this end, the experience of peer countries, highlighted in Box 5.1, Box 5.2 and Box 5.3 provides a useful practice). To this end, it will be important to measure and monitor several key aspects in the production, allocation and affordability of the units produced through the Fund, such as:

The regional production of the affordable rental units, to better understand market conditions as well as identify whether any barriers exist to affordable housing development in specific regions or municipalities;

The allocation of the rental units, disaggregating by household income level and other socio-demographic characteristics of the tenants, as well as by the region of origin of the tenants, to better understand the market demand as well as any impacts of the Fund on labour mobility;

The affordability of the rental units produced through the Fund, by collecting data on rent levels as a share of tenants’ household income; and the extent to which financial support schemes (e.g. the monthly housing benefit) increases the affordability of the newly developed units among low-income households who benefit from such supports.

Box 5.1. Austria: The pursuit of social mixing as a rationale for high-income thresholds for social and affordable housing

Social mixing – which is most often defined as diversity in terms of household income levels, but can also be assessed based on other socio‑economic categories (e.g. race/ethnicity, national origin, age, among others) – aims to avoid the potential negative consequences associated with socio‑economic segregation and the geographic concentration of poverty and disadvantage (OECD, 2020[3]). In Denmark, for instance, a number of other criteria are considered in the pursuit of social mixing, including, inter alia, the share of unemployment in the area; the share of inhabitants convicted for legal infractions; literacy rate; average gross income and the share of immigrants.

In Austria, high income ceilings, combined with a large social housing stock and high-quality standards, help facilitate social mixing of different socio‑economic groups and avoid the stigmatisation of social housing tenants. This approach has helped to avoid segregation, stigmatisation and the creation of “housing ghettoes,” particularly since subsidised rental housing makes up nearly 24% of the total housing stock (OECD, 2022[4]). Austrian experts report that subsidised housing is a “tenure of choice” for both low- and middle‑income households. Dwellings are well maintained and often of equal or superior quality than market-rate rental units.

Nevertheless, even with explicit social mixing objectives, it can still be difficult to reach very low-income and vulnerable households.

Source: (OECD, 2020[3]), Social housing: A key part of past and future housing policy, http://oe.cd/social-housing-2020; (OECD, 2022[4]), OECD Affordable Housing Database, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

Box 5.2. Strategies to promote social mixing in affordable and social housing: Experiences from OECD countries

To promote social mixing in the units produced through the Fund, experiences from other OECD countries could provide inspiration:

Refining the eligibility and allocation criteria

In the Netherlands, a prioritised allocation of units is granted to tenants within the income ceiling that have economic and social ties to the municipality. Simultaneously, a share of the dwellings remains reserved for low-income households. Denmark and the Netherlands also apply refined practices for allocating dwellings to priority groups. Denmark sets aside a share of vacant affordable dwellings that local governments can allocate to households in priority need. In the Netherlands, municipalities with a high demand for social housing are granted increased flexibility to allocate social dwellings, with a specific share set aside for priority cases.

Refining the rent-setting calculation

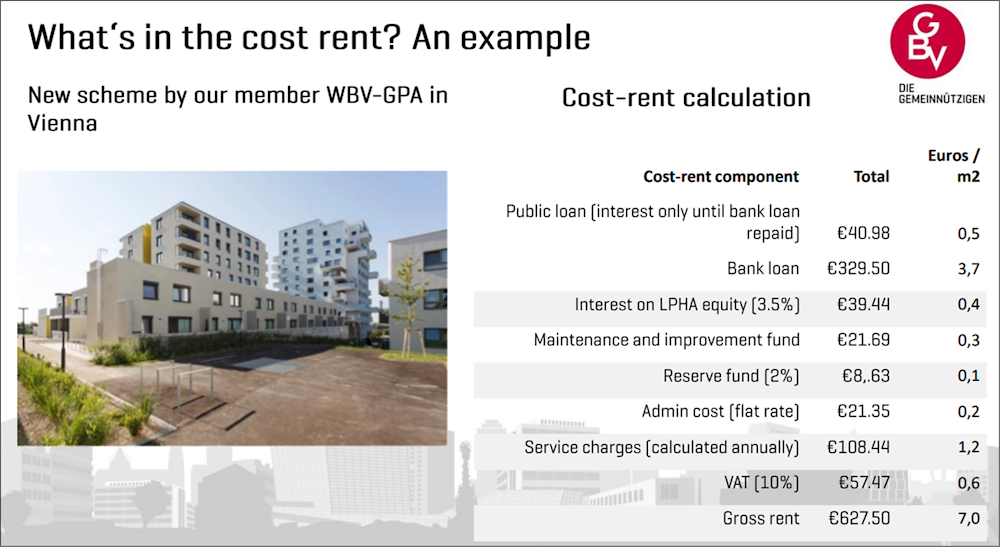

Refining the rent-setting calculation can help to extend the reach of dwellings. Experience from other countries shows that including a regional adjustment factor in the cost-based calculation facilitates accounting for local or regional cost differences (e.g. land prices). Data provided by the Latvian Ministry of Economics suggests that land prices for residential housing in Latvia vary considerably: 2021 estimates of average land prices per square metre were highest in the Riga and Pierīga regions (EUR 29.12 and EUR 12.24, respectively) – significantly higher than in Kurzeme (EUR 4.74), Zemgale (EUR 3.60), Latgale (EUR 2.10) or Vidzeme (EUR 2.09). Austria’s cost-based rent-setting, which includes a clear breakdown of the components of the rent calculation (Figure 5.2), provides inspiration to reconsider the variable component of a maximum tenant contribution of EUR 5/m2.

Some peer countries transfer the responsibility for costs, like real estate taxes, from tenants to owners. Another example to support affordability through rent-setting calculation comes from Slovenia. The country sets caps on selected costs for which tenants are responsible, such as maintenance and insurance contributions. To ensure sustained contributions, the maximum threshold for maintenance and insurance costs is flexible depending on the building age (lower caps are set for newer buildings).

Figure 5.2. A breakdown of Austria’s cost-rent calculation

Source: Presentations by Austrian experts at the Working Meeting with Latvian stakeholders organised by the OECD in 2021.

Monitoring the extent to which financial support schemes, such as housing benefits, enable low-income households to afford the rental dwellings

Another way to expand the reach of affordable dwellings to low-income households is through targeted supplementary financial support in the form of monthly housing allowances, which exist in Latvia and are widespread across the OECD (OECD, 2022[4]). In the Netherlands, for instance, tenants of social housing may also be eligible to apply for a housing benefit, which is calculated based on the amount of the tenants’ rent and/or income. In Slovenia, in parallel to the calculation of the rent level for non-profit rental apartments, the government calculates a supplementary subsidy for households according to the difference between the rent and the minimum income threshold. The calculated subsidy amount reduces the monthly rent, and the apartment owner is reimbursed by the municipality. A similar subsidy exists for eligible tenants in market-rental dwellings.

Box 5.3. Reserving the majority of social housing for households in the lowest income threshold and prioritising tenants with economic ties to the region: Experience from the Netherlands

Nearly half of the population is eligible for social housing in the Netherlands, determined by income levels. As of 2023, housing associations must lease 85% of their vacant social housing to households with an income of up to EUR 44 035 for single‑person households and EUR 48 625 for multi-person households (according to 2023 income thresholds). A maximum of 15% of vacant social housing may be let to people with an income above those thresholds if there are performance agreements in place among the local parties; if no such agreements are in place, the maximum is 7.5% of vacant dwellings. This income differentiation would be consistent with State aid rules as social mixing is considered a public policy objective. These dwellings are eligible for State Aid, which consists of reduced interest rates through loan guarantees, restructuring and project aid, and reduced land prices (from local government). Rent subsidies are also available for lower-income households to guarantee affordability.

In parallel, the Housing Act specifies that households “who are economically or socially bound to the housing market region” should be prioritised in allocating social housing.

Source: (Government of the Netherlands, 2014[5]), Housing Act of 2014, https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0035303/2022-01-01/#Hoofdstuk2. (Government of the Netherlands, 2023[6]), Am I eligible for a social rental home from a housing association?, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/huurwoning-zoeken/vraag-en-antwoord/wanneer-kom-ik-in-aanmerking-voor-een-sociale-huurwoning. (Elsinga and Lind, 2013[7]), The Effect of EU Legislation on Rental Systems in Sweden and the Netherlands, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.803044.

Table 5.2. Policy Action 12: Monitor the production, allocation and affordability of the units produced through the Fund

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

By 2026 |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

Policy Action 13: Channel tenant contributions for building improvements to a common fund

The Regulation creating the Housing Affordability Fund stipulates that tenant contributions for building improvements will be allocated to a fund that is specific to each building (e.g. linked to the building developer and/or the building manager); this means that building improvements will be financed at the scale of each building produced through the Fund. This approach contrasts with that of most peer countries, in which tenant contributions for improvements are mutualised into a common funding scheme, and building improvements are financed at the scale of the system as whole (Box 5.4). The risk with Latvia’s approach is that it may be harder to generate sufficient scale to cover the costs of any building improvements.

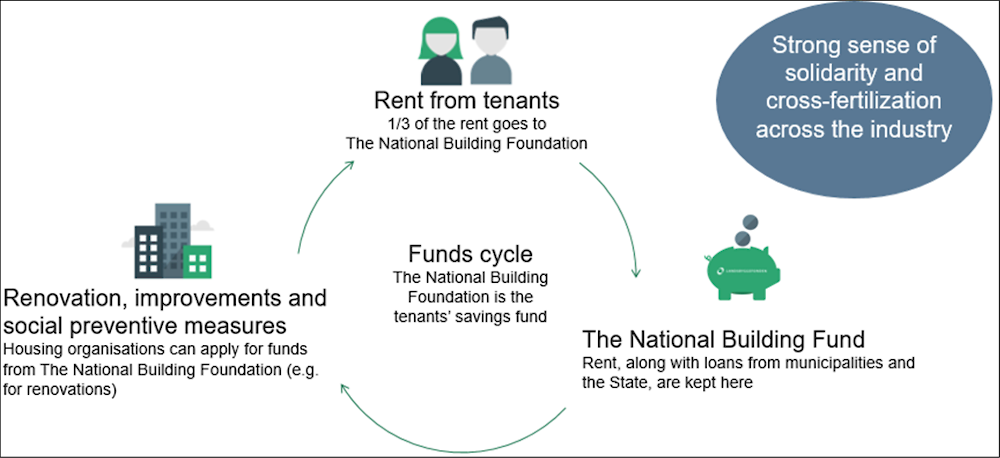

Box 5.4. Mutualising tenant contributions towards building improvements into a centralised fund

In other peer countries, tenant contributions for building improvements are mutualised into a centralised funding scheme. In Denmark, a share of tenant rents is allocated into the National Building Fund and earmarked for dwelling improvements, which can be financed through the Fund (Figure 5.3). In addition, Denmark and the Netherlands distinguish operating and maintenance costs – which are covered through a share of the revenue from tenants’ rental income – from more substantial dwelling improvement costs, which can be financed through loans from the National Building Fund (Denmark) or from loans guaranteed by the WSW (the Netherlands).

Figure 5.3. The funding cycle of Denmark’s National Building Fund includes a dedicated allocation of a share of tenant rent contributions towards a centralised fund

Source: Presentation by Danish National Building Fund at the Working Meeting with Latvian stakeholders organised by the OECD in 2022.

Table 5.3. Policy Action 13: Channel tenant contributions for building improvements to a common fund

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

By 2026 |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

5.2. Monitoring, audit and control mechanisms for revolving fund schemes

5.2.1. Where does Latvia stand in comparison to peer countries?

Table 5.4 provides a comparative snapshot of the mechanisms in place to supervise and monitor the funding mechanisms; the main actors engaged in monitoring and managing the affordable housing sector; and the approaches aimed at dealing with tenants’ complaints:

In all countries, monitoring and control of affordable housing funding depend on the main actors that fund and manage affordable housing. In Denmark and Slovenia, where the housing fund is a stand-alone independent body, the board and management of the fund are responsible for supervising and reporting on the activities of the fund. Both funds prepare annual reports with information on the activities carried out the by the funds. The Danish Fund collects a wealth of financial data and has also access to socio‑economic data from the Danish statistical office.

Where housing associations play an important role in the provision and management of affordable housing, monitoring and controls are also exercised over housing associations through the umbrella organisation and regional governments (Austria), an ad hoc authority (the Netherlands) or municipalities (Denmark). Latvia’s monitoring and control system is currently aligned with the monitoring of the RRP, of which the fund is part. The Ministry of Economics will supervise compliance with RRP regulation. Altum will supervise the use of the loans until the dwellings are ready for use and the capital rebate is granted. The Possessor will monitor the operation of the dwellings, including the allocation of the dwellings, adherence to income thresholds, occupancy of the assigned dwellings. Altum prepares an annual report where the activities linked to the fund are likely to be reflected.

External auditing of financial statements of housing associations and funds are in place in virtually all countries. Latvia’s Housing Affordability Fund is currently monitored through the RRF mechanism and an external auditing could be considered as the Fund expands.

In some countries, there are specific mechanisms to deal with complaints from tenants of affordable housing units. This is the case in Denmark and the Netherlands, where there are committees that deal with complaints and try to solve them before they reach the judiciary. In Latvia no such mechanism is currently envisaged.

Table 5.4. Comparative snapshot: Monitoring, auditing and control of affordable housing financing and actors

|

Latvia |

Austria |

Denmark |

The Netherlands |

Slovenia |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Monitoring and control |

The Ministry of Economics is responsible for monitoring the compliance with the RRP (including semi‑annual checks on RRP relevant monitoring indicators). Altum, as the administrator of the Fund, monitors the use and repayment of loans until the commissioning of the dwelling and the granting of the capital rebate. The Possessor is responsible for conducting inspections and regular supervision once the rebate is granted and verify that contributions from rental income have been made into the Fund. It also monitors overcompensation every three years and at the end of the entrustment act in line with State Aid regulation (European Commission Decision 2012/21/EU). According to RRP regulation, monitoring costs cannot exceed 3% of the RRP funding allocation. |

LPHA are supervised by the Auditing Association (part of the Austrian Federation of LPHA) and federal/regional government. Specifically, LPHA must be a member of the umbrella organisation, the Austrian Federation of Limited Profit Housing Associations. The umbrella organisation functions as an audit association (Revisionsverband). It produces an annual report, which analyses compliance with the Limited-profit Housing Act, the standard accounting principles, the economy and operating efficiency of the company, and the suitability of the management. The report has to be shared with the regional governments. Regional governments act as external supervisors and could impose sanctions, withdrawal of public subsidies or rescinding of the LPHA status. |

The Fund’s Board (where the majority of members are appointed by the Danish Social Housing Association-BL) is responsible for supervising the activities of the Fund. Municipalities have oversight responsibility over the spending and budgets of housing associations. Accounting records are submitted annually for examination by the supervisory local authority. Audited reports from all beneficiaries of public support and Fund’s loans are reported to the Fund through an on-line form. The Fund produces an annual report with information on the activities of the Fund and rental statistics collected by the Fund. |

Housing associations are obliged to produce an annual report detailing their activities and financial statements. Since 2015, the Housing Associations Authority (AW) acts as supervisory body on the governance and integrity of the housing associations, as well as their financial management. The AW also monitors the lawfulness of housing associations’ activities. In addition, the AW is responsible for supervision of WSW. The AW can impose sanctions on housing associations, such as a financial penalty or the appointment of a supervisor. Most of the time, the AW uses milder interventions, which match the intended effect and the seriousness of the situation. The AW also reports on the financial situation of the sector as a whole and the public housing performance of the sector. |

The Ministry of Solidarity-based Future is responsible for monitoring the implementation of the National Housing Programme. The Statistical Office collects and publish data on housing indicators used to monitor the activities and progress made by the Fund. As an independent public body, the Housing Fund’s management is responsible for supervising the activities of the fund and ensuring compliance with relevant rules and procedures. The Fund prepares an annual report with information on the operation of the funds, activities conducted, objectives achieved and financial information. |

|

Auditing |

Auditing of Altum’s financial statements. |

LPHA owned by public bodies (50%+) are also supervised by the Austrian Court of Audit (Rechnungshof). The ultimate supervision and control of the Federation of LPHA is carried out by the Federal Ministry for Digitalisation and Economic Affairs (BMDW), by the ministry of the Association of Austrian Auditing Associations (VÖR), and by the Federal Ministry of Finance (BMF). |

The Fund’s accounts are audited by a state‑authorised auditor who is appointed by the Minister for Social Housing on the recommendation of the Foundation administering the Fund. The auditor has access to inspect all accounting books and stocks and can demand any information deemed important. An audit protocol is kept. |

In line with regulation on public funds, the financial statements of the Fund are audited by an external auditor. The auditor’s report is included in the annual report. |

|

|

Tenants’ protection |

Specific provisions are in place to address tenant complaints in the affordable housing units. Tenants will have access to the same remedies for tenant protection under current legislation (civil courts). Residential Tenancy Law enables municipalities to establish a pre‑trial institution, in the form of a tenancy board, to review tenant complaints. Tenancy boards would comprise three representatives from tenants and three from landlords. |

District Courts have jurisdiction over tenant disputes. In 10 municipalities (including Graz, Innsbruck, Klagenfurt, Linz, Salzburg and Vienna, with the largest housing stock), Arbitration Boards for Housing settle specific tenancy law cases in the first instance (the boards are required to settle the dispute six months within a complaint’s filing). |

Tenant boards of appeal (created by the 1998 Social Renting Act) are in place to resolve disputes between tenants and housing associations. The two most frequent types of disputes occur in relation to maintenance and repair activities in connection with vacating a residence and house‑rule violations. |

Tenants can submit complaints to their housing association’s complaints committee or to the Rent Tribunal. Filing a complaint in the Rent Tribunal has a cost of EUR 450 for a company or EUR 25 for a tenant. Complaints may relate to maintenance, service charges, rent or nuisances. |

Municipalities can establish councils for the protection of tenants’ rights. There is a national council that assembles these municipal councils. |

5.2.2. Recommendations for Latvia based on peer practices

Policy Action 14: Assign dedicated staff with legal, real estate, economic and financial expertise within Altum and the Possessor to manage, supervise and monitor the Fund’s activities

The choice of a relatively “light” monitoring and control mechanism is a wise and efficient choice while the Fund is still in its infancy. It will nonetheless be important to anticipate the monitoring and control needs in the early phases of the Fund, and to support the development of the Fund over time. This is especially important for the two public institutions charged with carrying out the management and monitoring functions of the Fund and its activities, Altum and the State Asset Possessor. The human resource capacity of these institutions can continue to be built up over time, to include, as relevant, financial, real estate and economics expertise. Gaps can be addressed through targeted training and/or hiring, drawing on peer country experience (Box 5.5).

Box 5.5. The organisational structure of Denmark’s Housing Fund

The Fund has an independent administration, led by an executive board consisting of a managing director and a director of operation, and is organised in four centres with associated teams:

The Centre for Housing Social Efforts, Communication and Urban Strategy is responsible for case processing regarding housing social efforts, communication and dissemination of the foundation’s work and urban strategic initiatives.

The Administration Centre is responsible for capital management, collection of compulsory contributions, housing portal/rent register, asset management, bookkeeping, accounting and personnel administration.

The Centre for Almen Analysis is responsible for the guarantee scheme for department funds, computerised accounting reporting, the accounting database, benchmarking, thematic studies and analyses, as well as carrying out accounting reviews and providing guidance on accounting issues. Almen Analysis has developed various IT tools such as the Accounting Database and the Twin tool.

The Centre for Special Operating Support is responsible for handling cases regarding renovation, capital injection, rent support, and provides secretarial assistance to the board and management.

Source: (National Building Fund (Landsbyggefonden), 2023[8]), Organisation, https://lbf.dk/om-lbf/organisationen/.

Table 5.5. Policy Action 14: Assign dedicated staff with legal, real estate, economic and financial expertise within Altum and the Possessor to manage, supervise and monitor the Fund’s activities

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

By 2026 |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

Policy Action 15: Develop the Fund’s data infrastructure

The monitoring and controls of the activities of the Housing Affordability Fund will require the collection of significant amounts of data, which can in turn be leveraged to help monitor and inform policy decisions. Experiences from peer countries (Box 5.7) suggest the key role of the national fund in supporting efforts to expand data collection on affordable housing over time. In the case of Denmark, financial data were collected first, followed by data on building maintenance standards; followed by data on the socio‑economic characteristics of households living in the units produced through the Fund as well as the broader neighbourhood. Initially the data will be used for monitoring purposes. The Netherland’s experience in collecting financial data would be also relevant in the early stages of the Fund (Box 5.6). Over time, these data could be made publicly available for research and analysis. They will also serve as a basis for the design and implementation of housing policies.

Latvia should envisage building up the data infrastructure of the Fund over time, building on the monitoring requirements:

Construction and quality standards: Altum will have to monitor the delivery of the units and ensure that the units meet the quality requirements established in the Regulation before providing the capital rebate.

Construction costs: once the units are delivered and rented, every three years until the entrustment act ends, the Possessor will have to control every three years for at least ten years that the beneficiaries of the capital rebate are not overcompensated.

Financial data: Altum will have to monitor the loan performance and loan conditions, requiring the collection of financial data.

Affordability: Over time, the Fund’s data collection can become a tool to monitor the affordability of the units developed, by assessing rent levels against household income, and, where needed, to adjust tenants’ eligibility criteria by adding data on occupancy of the affordable housing units (see policy action recommended below).

Box 5.6. The Netherlands’ joint assessment framework and data collection

The Netherlands relies on a joint assessment framework (undertaken by AW & WSW). The joint assessment framework focuses on the three key aspects: financial continuity; business model; governance and organisation. Every year, each housing association must provide: balance sheet, cashflow statement, and profit and loss statement. AW and WSW each have specific aspects to monitor, based on the joint assessment framework, which helps to provide a more complete picture of housing associations’ activities.

Box 5.7. The Danish Housing Fund’s data collection

The Fund collects various types of data on the social housing sector and social housing tenants, including all financial statements by entities in social housing, which are made publicly available on the Fund’s website. The Fund also develops thematic statistics on the conditions of the social housing sector as well as other issues.

The Fund maintains a rental database, detailing the rent (and composition hereof) of every social housing unit in Denmark. This is used, inter alia, to monitor rent levels.

The Fund has access to Statistics Denmark’s detailed databases, with information on employment levels, education, income in the rental sector.

Table 5.6. Policy Action 15: Develop the Fund’s data infrastructure

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

By 2026 |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

Policy Action 16: Set up a dedicated website for the Fund to increase its visibility and facilitate the exchange of information

Setting up a dedicated website for the Fund could help to increase its visibility and facilitate access and exchange of information, particularly relating to investment opportunities and monitoring requirements. This is critical, because, in the initial phase, there is no single institution responsible for managing the Fund, and information relating to its activities will inevitably be posted on multiple institutions’ websites (e.g. the Ministry of Economics, Altum and the State Asset Possessor). A single virtual interface, which could include, for instance, application forms and filings for loans, loan reporting and data filing for rents, would be relatively inexpensive to set up and manage. The Danish National Housing Fund’s portal provides a useful example (Box 5.8). In Slovenia, the HFRS also has a dedicated website with information on its instruments for tenants, local communities, non- profit housing organisations and local housing funds. This describes programmes, calls, tenders of the Fund and comprehensive information on its policies and activities. In addition, tenants can apply for rent online on HFRS portal.

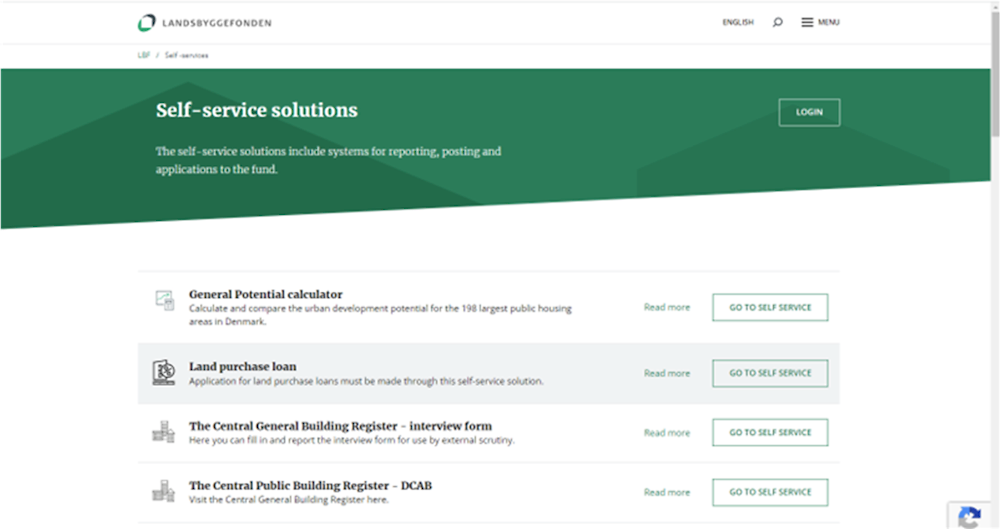

Box 5.8. Denmark’s Self-Service Portal

The website of the Housing Fund has a dedicated “self-service” webpage with application forms and filing for loans, loan reporting and data filing for rents. The website also includes, among others, calculators for urban development potential and evaluation tools for renovation projects (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4. Denmark’s self-service portal

Source: (National Building Fund (Landsbyggefonden), 2023[9]), Self-service solutions, https://lbf.dk/selvbetjeninger/.

Table 5.7. Policy Action 16: Set up a dedicated website for the Fund to increase its visibility and facilitate the exchange of information

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

By 2026 |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

References

[2] Cabinet of Ministers (Latvia) (2022), Regulations of the Cabinet of Ministers No. 459, Regulations on support for the construction of residential rental houses in the European Union Recovery and Resilience Mechanism Plan 3.1, https://likumi.lv/ta/id/334085-noteikumi-par-atbalstu-dzivojamo-ires-maju-buvniecibai-eiropas-savienibas-atveselosanas-un-noturibas-mehanisma-plana-3-1 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[7] Elsinga, M. and H. Lind (2013), “The Effect of EU-Legislation on Rental Systems in Sweden and the Netherlands”, https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.803044, Vol. 28/7, pp. 960-970, https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.803044.

[6] Government of the Netherlands (2023), Am I eligible for a social rental home from a housing association?, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/huurwoning-zoeken/vraag-en-antwoord/wanneer-kom-ik-in-aanmerking-voor-een-sociale-huurwoning (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[5] Government of the Netherlands (2014), Housing Act 2014, https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0035303/2022-01-01/#Hoofdstuk2 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[8] National Building Fund (Landsbyggefonden) (2023), Organization, https://lbf.dk/om-lbf/organisationen/ (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[9] National Building Fund (Landsbyggefonden) (2023), Self-service solutions, https://lbf.dk/selvbetjeninger/ (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[4] OECD (2022), Affordable Housing Database - OECD, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

[1] OECD (2020), Policy Actions for Affordable Housing In Latvia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=137_137572-i6cxds8act&title=Policy-Actions-for-Affordable-Housing-in-Latvia.

[3] OECD (2020), Social housing: A key part of past and future housing policy, Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Policy Briefs, http://oe.cd/social-housing-2020. (accessed on 15 April 2021).

Annex 5.A. Housing affordability simulation for Latvia

Assessing the affordability of the dwellings produced through the Fund relative to household income: Preliminary results from an OECD illustrative simulation

A simulation by the OECD found that the new affordable dwellings are most likely to support the unmet housing needs of middle‑income households – the “missing middle” identified in OECD (OECD, 2020[1]). The highest income households are ineligible to lease the units because they exceed the income ceilings; lower-income households would not be able to easily afford the rent levels without additional financial support from municipal authorities (such as the housing benefit). Without such additional support, the new units are unlikely to be affordable to low-income households relative to their monthly disposable income. This is in line with the government’s envisaged objective of targeting middle‑income households.

To recall, the rent-setting calculation outlined in the Regulation includes a variable component that can be no higher than EUR 5.87/m2 (EUR 5/m2 at the time of the simulation), along with a number of other required tenant contributions, such as, inter alia, utilities, the real estate tax and insurance costs; rent levels can be adjusted annually in line with inflation. For the purposes of the OECD simulation, two scenarios were envisaged to estimate the affordability of a one‑room dwelling produced through the fund: a legislative maximum rent scenario, where the variable component of the rent-setting calculation is assumed at the legislative maximum (e.g. EUR 5/m2), in addition to the other required tenant contributions; and an average rent scenario, where the variable component of the rent-setting calculation is calculated based on a lower tenant contribution per square metre (assumed here as EUR 2.5/m2), in addition to the other required tenant contributions. The results suggest:

Under the legislative maximum rent scenario, rent levels would account for 22% of the disposable income of households earning right around the maximum income allowed to be eligible for a one‑room apartment. However, households earning the minimum wage would end up spending 43% of their disposable income on rent for the one‑room dwelling, and would thus be considered overburdened by housing costs (see OECD (2022[4])).

Under the average rent scenario, around one‑third of eligible households would spend over 40% of their disposable income on rent for a one‑bedroom dwelling and thus be considered overburdened by housing costs.

Although the Housing Affordability Fund will not fund new affordable rental development in Riga and several municipalities surrounding the capital city, all Latvian households – regardless of their current place of residence – are eligible to apply to live in the newly produced dwellings so long as they meet the income criteria. While it is not expected that many households will choose to leave the capital region to rent a dwelling in another region, regional take‑up of the affordable units should be closely monitored. More broadly, it will be important for the Latvian authorities to measure the affordability of the units produced through the Fund by collecting data on rent levels as a share of tenants’ household income.