The G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance recommend that the corporate governance framework ensures the strategic guidance of the company by the board and its accountability to the company and the shareholders. Chapter 4 provides information on regulatory frameworks on board structures, board independence and board-level committees, as well as risk management and implementation of internal controls, including new information on the establishment of a separate sustainability committee. The chapter also includes a section on auditor independence, accountability and oversight, with new information on audit firm and audit partner rotation. The chapter also covers board nomination and election, executive remuneration, and gender diversity on boards and in senior management.

OECD Corporate Governance Factbook 2023

4. The corporate board of directors

Abstract

4.1. Basic board structures and independence

One‑tier board structures are favoured in 23 jurisdictions compared to eight for two‑tier boards, but a growing number of jurisdictions allow both structures.

Different models of board structures are found around the world. Among the 49 surveyed jurisdictions, one‑tier boards, whereby executive and non-executive board members may be brought together in a unitary board system, are most common (in 23 jurisdictions). Nine jurisdictions have exclusively two‑tier boards that separate supervisory and management functions. In such systems, the supervisory board typically comprises non-executives board members, while the management board is composed entirely of executives. However, there are variations in how these board structures are applied across jurisdictions, as detailed in Table 4.2 and Table 4.3 (and some footnotes of Table 4.1). Overall, a growing number of jurisdictions (15), mainly from within the European Union, offer the choice of either single or two‑tier boards, consistent with EU regulation for European public limited-liability companies (Societas Europaea) (Council Regulation (EC), 2001) (Table 4.1). In addition, three jurisdictions (Italy, Japan, and Portugal) have hybrid systems that each allow for three options and provide for an additional statutory body mainly for audit purposes (Table 4.4).

Most Factbook jurisdictions impose minimum limits on board size, usually ranging from three to five members.

Ninety percent of surveyed jurisdictions require or recommend a minimum board size most commonly set at three members, regardless of board structures. Limits on the maximum size for boards are rare and exist in only nine out of 49 jurisdictions, ranging from five in Brazil under its two‑tier system to 21 in Mexico. In some jurisdictions, minimum board size requirements vary depending on the company’s market capitalisation and the size of its voting shareholder base (Chile and India). For management boards in two‑tier systems, only the People’s Republic of China (hereafter ‘China’) (19) and France (seven) establish a maximum size requirement, while 18 jurisdictions set a minimum size requirement, usually in the range of one to three members.

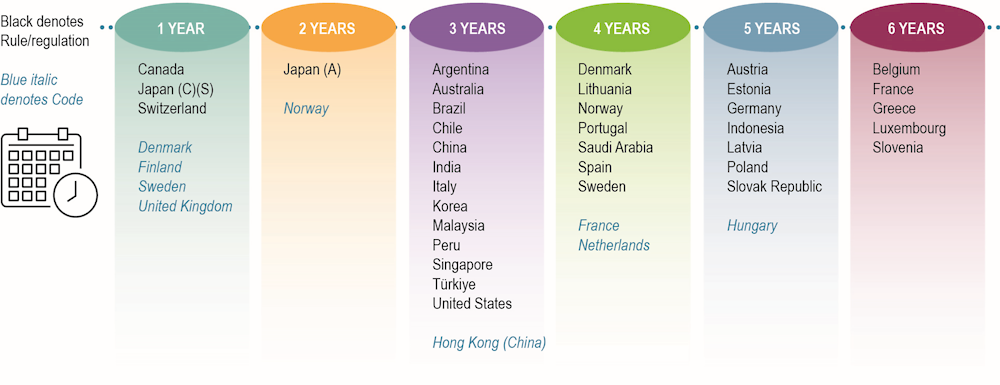

All but nine of the 49 surveyed jurisdictions have established maximum terms of office for board members before re‑election, with three‑year terms being the most common practice, and annual re‑election for all board members being required or recommended in six jurisdictions.

The maximum term of office for board members before re‑election varies from one to six years, with the largest number (13) requiring or recommending that it be set at three years. Annual re‑election for all board members is required or recommended in seven jurisdictions (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom). In some of the other jurisdictions, a number of companies have moved to require that their directors stand for re‑election annually. For instance, in the United States, while Delaware law and exchange rules permit a company to have a classified board which typically has three classes of directors serving staggered three‑year board terms, many companies have adopted annual re‑election, and the classified board system has become less prevalent. In France, it is recommended that the terms of office of the board members be staggered. In Hong Kong (China), each director should be subject to retirement from office by rotation at least once every three years.

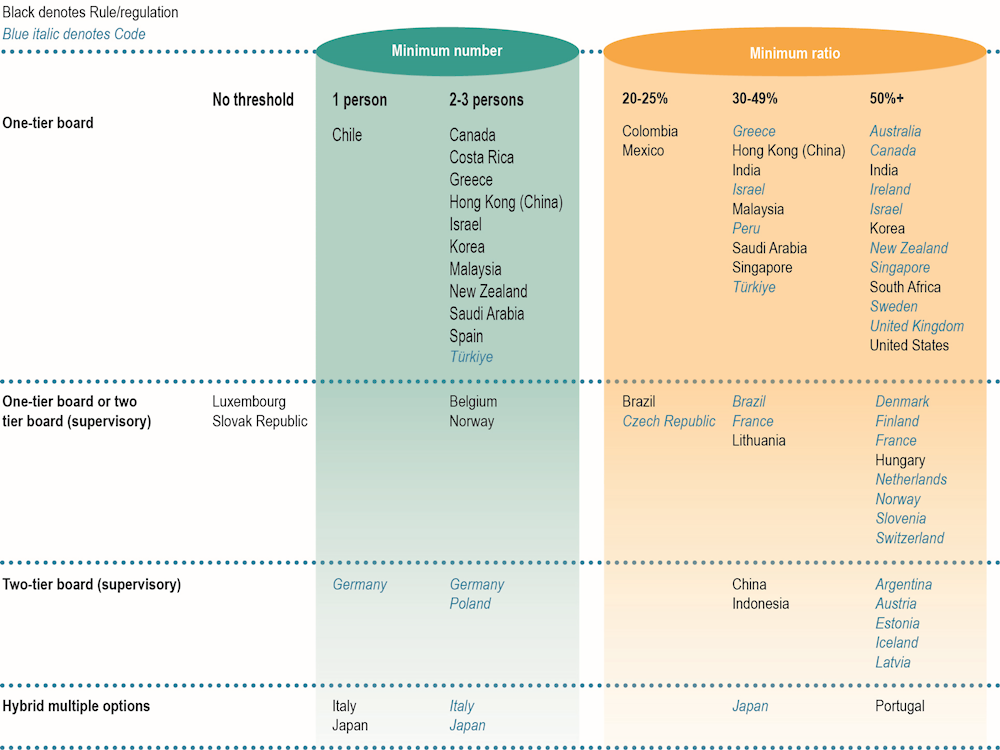

Despite differences in board structures, almost all jurisdictions have introduced a requirement or recommendation with regard to a minimum number or ratio of independent directors. The most common requirement is for two to three board members (or at least 30% of the board) to be independent, while the most common recommendation is for boards to be composed of at least 50% of independent directors.

Figure 4.1. Maximum term of office for board members before re‑election

Note: The figure refers to both 1‑tier and 2‑tier boards, with requirements for 2‑tier boards applying to the supervisory board. “Japan (A), (S) and (C)” denote a company with statutory auditors model, audit and supervisory committee model, and three committees model respectively. No maximum term in Colombia, Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, and South Africa. See Table 4.5 for data.

Principle V.E of the G20/OECD Principles calls for boards to exercise objective independent judgement on corporate affairs, while sub-Principle V.E.1 further specifies that “[b]oards should consider assigning a sufficient number of independent board members capable of exercising independent judgement to tasks where there is a potential for conflicts of interest” (OECD, 2023[1]). All but two of the surveyed jurisdictions (Luxembourg and the Slovak Republic) require or recommend a minimum number or ratio of independent directors. Six jurisdictions have established binding requirements for 50% or more independent board members for at least some companies (Hungary, India, Korea, Portugal, South Africa, and the United States). By contrast, a much larger group of 20 jurisdictions have established code recommendations for a majority of the board to be independent on a “comply or explain” basis, including eight jurisdictions with one‑tier boards, seven jurisdictions with two‑tier boards, and five with both systems (Table 4.6, Figure 4.2). Fifteen jurisdictions have established minimum independence requirements for at least two to three board members and/or at least 30% of the board. Many jurisdictions have at least two standards: a legally mandated minimum requirement for independent board members usually coupled with a more ambitious voluntary recommendation for high numbers (including Brazil, Greece, Israel, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, and Norway).

Six of the surveyed jurisdictions link board independence requirements or recommendations with the ownership structure of a company (Table 4.7). In four of these jurisdictions (Chile, France, Israel and the United States), companies with more concentrated ownership are subject to less stringent requirements or recommendations. The role of independent directors in controlled companies is different than in dispersed ownership companies, since the nature of the agency problem is different (i.e. in controlled companies the vertical agency problem between ownership and management is less common and the horizontal agency problem involving controlling and minority shareholders greater). In Italy, a stricter requirement for a majority of independent directors is imposed in cases involving integrated company groups with pyramid structures that may contribute to more concentrated control. In addition, a large number of jurisdictions have established more specific provisions to help ensure that minority shareholders have the possibility to elect at least one director in companies with controlling shareholders, as detailed in Table 4.15.

Figure 4.2. Minimum number or ratio of independent directors on the (supervisory) board

Note: The United States requirement applies to listed companies without a controlling majority. See Table 4.6 for data.

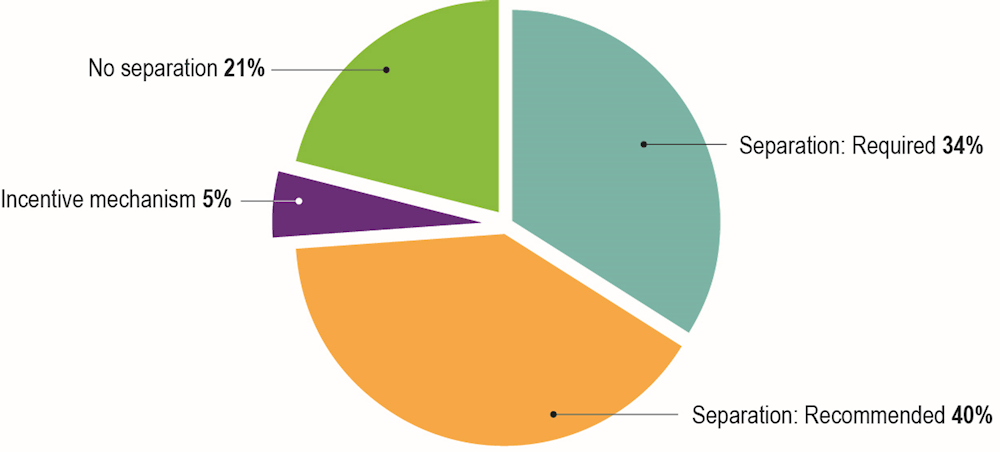

While only 34% of jurisdictions with one‑tier board systems require the separation of the functions of board chair and CEO, an additional 40% encourage it through code recommendations or incentive mechanisms.

Thirteen of 38 jurisdictions with one‑tier board systems require and 15 such jurisdictions recommend the separation of the functions of board chair and CEO in “comply or explain” codes. In addition, India and Singapore encourage the separation of the two functions through an incentive mechanism by requiring a higher minimum ratio of independent directors (50% instead of 33%). For two‑tier board systems, the separation of the functions is assumed to be required as part of the usual supervisory board/management board structure.

National approaches to defining the ‘independence’ of independent directors vary considerably, particularly with regard to maximum tenure and independence from a significant shareholder. Many jurisdictions also establish a maximum tenure for board members to be considered independent.

Figure 4.3. Separation of CEO and chair of the board in one‑tier board systems

Note: Based on 38 jurisdictions with on-tier board systems. The two jurisdictions denoted as “Incentive mechanism” set forth a higher minimum ratio of independent directors on boards where the chair is also the CEO. See Table 4.6 for data.

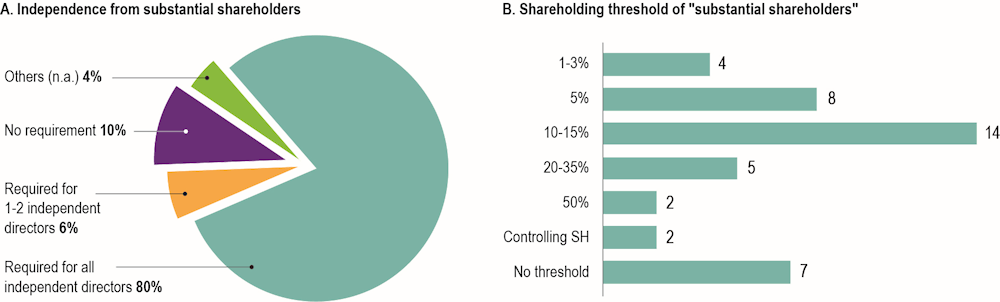

Principle V.E. of the G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance, as revised in 2023, states that “[w]hile national approaches to defining independence vary, a range of criteria are used, such as the absence of relationships with the company, its group and its management, the external auditor of the company and substantial shareholders, as well as the absence of remuneration, directly or indirectly, from the company or its group other than directorship fees.” The legal or regulatory approaches vary among jurisdictions, particularly with regard to independence from a significant shareholder and maximum tenure. While the large majority of jurisdictions’ definitions of independent directors include requirements or recommendations that they be independent of substantial shareholders (86%), the threshold for substantial shareholding ranges from 2% to 50%, with 10‑15% the most common share (in 14 jurisdictions).

Figure 4.4. Requirements for the independence of directors and their independence from substantial shareholders

Note: Based on data from 49 jurisdictions. These figures show the number of jurisdictions and percentages in each category. See Table 4.6 for data.

There are also significant differences concerning maximum tenure. Twenty-eight jurisdictions set a maximum tenure for independent directors, ranging from 5 to 15 years (with eight to ten years being the most common length). Twenty-two jurisdictions require or recommend that these directors no longer be considered as independent at the end of their tenure, and seven jurisdictions that an explanation be provided regarding their independence (Figure 4.5). A number of jurisdictions have introduced or strengthened requirements and recommendations for maximum term limits. For example, Costa Rica introduced new criteria for independence to take effect by the beginning of 2026 that will phase in a maximum tenure of nine years within a 12‑year period. In Malaysia, a mandatory 12‑year maximum tenure for independent directors was introduced as a listing rule and took effect on 1 June 2023, in addition to the shorter nine‑year limit that applies as a recommendation. The listing rule requires that if an individual has cumulatively served as an independent director of a company or its related companies for more than 12 years and observed the requisite three‑year cooling off period, the company must provide a statement to justify the nomination of the person as an independent director and explain why there is no other eligible candidate.

Figure 4.5. Definition of independent directors: Maximum tenure

Only China and some European countries have requirements for employee representation on the board.

No jurisdiction prohibits publicly listed companies from having employee representatives on the board. Ten European countries and China have established legal requirements regarding the minimum share of employee representation on the board, which varies from one member to half of board members, with one‑third the most common share. In Denmark and Sweden, there is no requirement for employee board representation but there is a statutory right for employees to appoint up to two to three representatives depending on the size of the company (Table 4.8).

4.2. Board-level committees

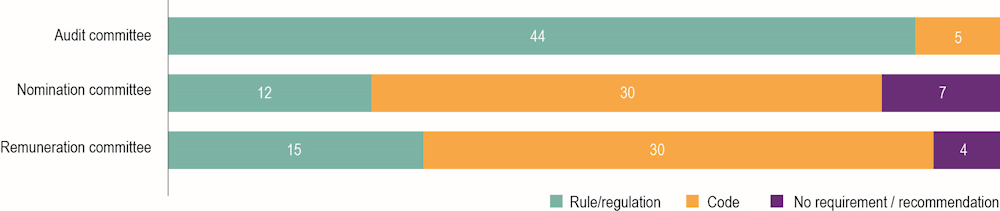

All but five jurisdictions require the establishment of an audit committee with provisions to promote their independence. Nomination and remuneration committees are not mandatory in most jurisdictions, but most jurisdictions at least recommend that they be established and often that they be comprised wholly or largely of independent directors.

Audit committees have traditionally been a key component of corporate governance regulation. The G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance, as revised in 2023, emphasises the important role of audit committees by stating that “[b]oards should consider setting up specialised committees to support the full board in performing its functions, in particular the audit committee – or equivalent body – for overseeing disclosure, internal controls and audit-related matters” (sub-Principle V.E.2). The roles of the audit committee as further elaborated in the Principles also include oversight of the internal audit activities (IV.C) and may include support for the board’s oversight of risk management (V.D.2).

All surveyed jurisdictions require or recommend listed companies to establish an independent audit committee. Forty-four jurisdictions have binding rules for audit committees and five recommend them on a “comply or explain” basis. Some jurisdictions (Brazil, Finland and Sweden) are considered as requiring the establishment of audit committees although they allow some flexibility for alternative arrangements (in Brazil, fiscal councils can be used to carry out most audit committee functions, while in Finland and Sweden the functions of the audit committee are explicitly required but may be carried out by the full board). In the United States, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 requires exchanges to adopt rules requiring independent audit committees to oversee a company’s accounting and financial reporting processes and audits of a company’s financial statements. These rules require independent audit committees to be directly responsible for the appointment, compensation, retention and oversight of the work of external auditors engaged in preparing or issuing an audit report, and the issuer must provide appropriate funding for the audit committee.

With regard to nomination and remuneration committees, the revised G20/OECD Principles provide for more flexibility by stating that “[o]ther committees, such as remuneration, nomination […] may provide support to the board depending upon the company’s size, structure, complexity and risk profile (Sub-Principle V.E.2).” The majority (61%) of jurisdictions have code recommendations to establish these committees, while nomination committees are mandatory in only 24% of jurisdictions and remuneration committees in 31%.

Figure 4.6. Board-level committees by category and jurisdiction

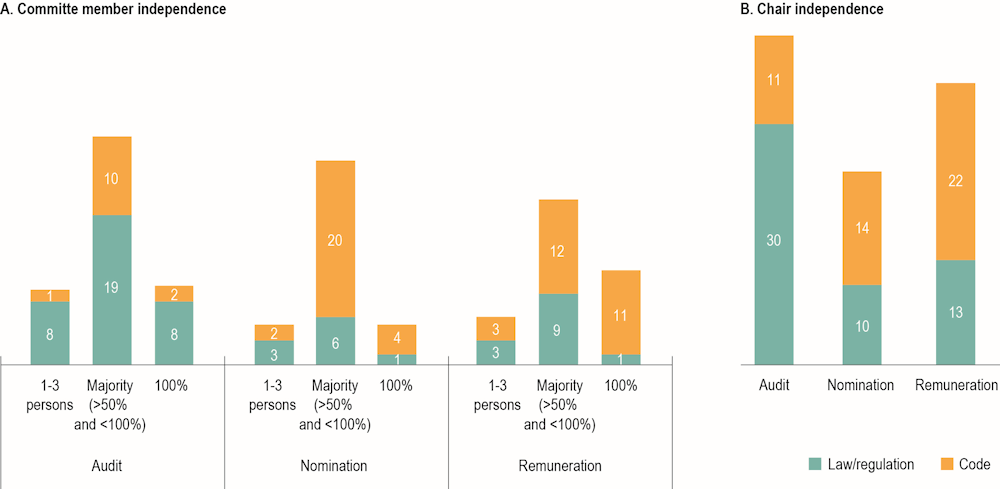

Full or majority independent membership is required or recommended for all three committees in most of the jurisdictions. A majority of jurisdictions (55%) require the audit committee to have at least a majority of independent directors, while 24% recommend such independence in their codes. Eight jurisdictions set a requirement for the minimum number of independent directors, from one to three members. Code recommendations are more common than legal requirements to encourage nomination and remuneration committees to have at least a majority of independent members (49% and 47% respectively). Concerning the independence of committee chairs, requirements are also most common for audit committees (in 61% of jurisdictions), and it is more frequently a code recommendation for nomination and remuneration committees.

Figure 4.7. Independence of the chair and members of board-level committees

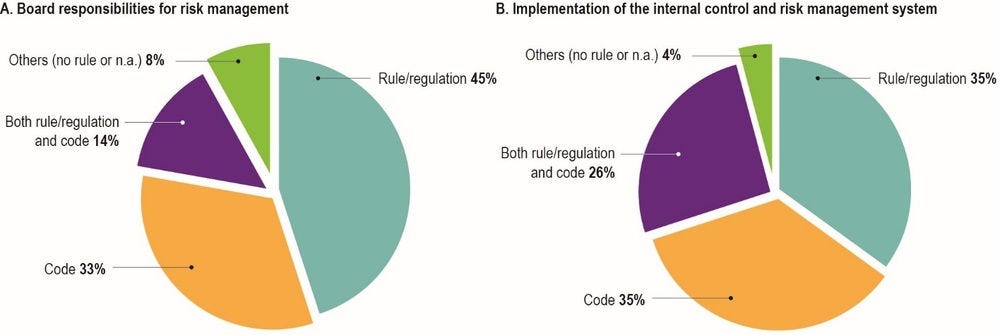

More than 90% of jurisdictions require or recommend assigning a risk management role to the board. Provisions for internal control and risk management systems are also required or recommended in the majority of jurisdictions, a significant evolution since 2015.

Explicit legal requirements or recommendations on risk management grew significantly after the 2008 financial crisis. The revised G20/OECD Principles have a new sub-Principle V.D.2 on the board’s responsibility for reviewing and assessing risk management policies and procedures. Approximately 60% of jurisdictions now have requirements regarding the board’s responsibilities with respect to risk management in the law or regulations (including 14% that have both rules and code provisions), while another 33% recommend it solely in codes (similar to 2020 levels). Nearly all surveyed jurisdictions (96%) require or recommend implementing an enterprise‑wide internal control and risk management system (beyond ensuring the integrity of financial reporting) (Figure 4.8).

Figure 4.8. Risk management and implementation of internal controls

A large majority of jurisdictions now require or recommend board-level committees to play a role in risk management oversight. The revised G20/OECD Principles (Sub-Principle V.E.2) point out that “[w]hile risk committees are commonly required for companies in the financial sector, a number of jurisdictions also regulate risk management responsibilities of non-financial companies, requiring or recommending assigning this role to either the audit committee or a dedicated risk committee. The separation of the functions of the audit and risk committees may be valuable given the greater recognition of risks beyond financial risks, to avoid audit committee overload and to allow more time for risk management issues.” Taking into account both requirements and recommendations, the audit committee is the preferred choice for risk oversight in 38 jurisdictions, while risk committees are required or recommended in 16 jurisdictions (Figure 4.9).

On sustainability, the revised Principles outline that “the board should ensure that material sustainability matters are considered” (V.D.2). The Principles also note that “[s]ome boards have created a sustainability committee to advise the board on social and environmental risks, opportunities, goals and strategies, including related to climate” (V.D.2). In terms of regulatory frameworks, South Africa is the only jurisdiction that requires this type of committee; listed companies are required to establish a social and ethics committee that is tasked to review sustainability issues. Another five jurisdictions recommend establishing a separate sustainability committee (Chile, France, Italy, Luxembourg, and Malaysia), while the remaining 43 jurisdictions do not have requirements or recommendations for a stand-alone sustainability committee. However, some jurisdictions address sustainability matters in other board-level committees. For example, in India, the role of the risk management committee includes formulation of a detailed risk management policy which includes a framework for identification of sustainability risks.

Figure 4.9. Board-level committee for risk management

4.3. Auditor independence, accountability and oversight

The G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance recognise the importance of the quality of a company’s financial reporting, supported by an independent external audit, to ensure market confidence, accountability and good corporate governance. In particular, Principle IV.C outlines that “[a]n annual external audit should be conducted by an independent, competent and qualified auditor in accordance with internationally recognised auditing, ethical and independence standards in order to provide reasonable assurance to the board and shareholders on whether the financial statements are prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with an applicable financial reporting framework.”

While the shareholders have the primary responsibility for appointing and/or approving the external auditor in the majority of Factbook jurisdictions, the board is often required to recommend suitable candidates for shareholder’s final approval.

All jurisdictions require that an external auditor be appointed to perform an audit of the financial statements of publicly listed companies, including assessing compliance with applicable federal/state or industry-specific regulations, laws, and standards. In 42 jurisdictions, the shareholders have the primary responsibility for appointing and/or approving the external auditor. In the remaining seven jurisdictions, the board has the primary responsibility (Brazil, Costa Rica, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Poland, and the United States). Among the jurisdictions where shareholders are primarily responsible for appointing/approving an external auditor, a number also require the involvement of the board in the process to assist the shareholders’ decision. For example, in 19 jurisdictions, the board is required to recommend appropriate candidates for shareholders’ appointment/approval. Furthermore, some jurisdictions also provide for the board to appoint the auditor in certain cases, for example where the shareholders fail to do so, or where the position remains vacant within a given period of a company’s registration (Australia, Canada, Ireland, Israel, Singapore, and the Netherlands). In Indonesia, the board of commissioners can be the party that appoints the external auditor if shareholders mandate it to do so.

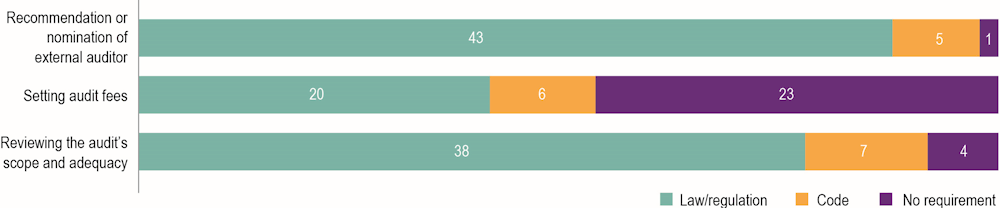

The audit committee is required or recommended to play a role in the selection and removal process of the auditor as well as in reviewing the audit’s scope and adequacy in nearly all jurisdictions, while its role is less commonly required or recommended in setting audit fees.

The G20/OECD Principles, as revised, state that it is good practice that external auditors be recommended by an audit committee independent of the board (IV.D). In 48 out of the 49 surveyed jurisdictions, the audit committee is required or recommended to play a role in the selection and appointment or removal process of the external auditor of listed companies. In the United Kingdom, legislation requires all companies with securities traded on regulated markets, as well as all deposit holders and insurers, to have an audit committee to select the auditor for the board to recommend to the shareholders. For the largest public companies, the board must accept the audit committee’s recommendation, and for others, the shareholders must be informed of any departure by the board from the recommendation. Reviewing the audit’s scope and adequacy is also a major role that the audit committee plays, and it is required or recommended in 92% of jurisdictions. Requirements and recommendations concerning the involvement of the audit committee in setting the audit fees is less common (53%).

Figure 4.10. Role of the audit committee in relation to the external audit

In order to promote the independence and accountability of external auditors for publicly listed companies, jurisdictions have adopted provisions such as mandating auditor rotation, and prohibiting or restricting external auditors from providing non-audit services such as tax services to their audit clients.

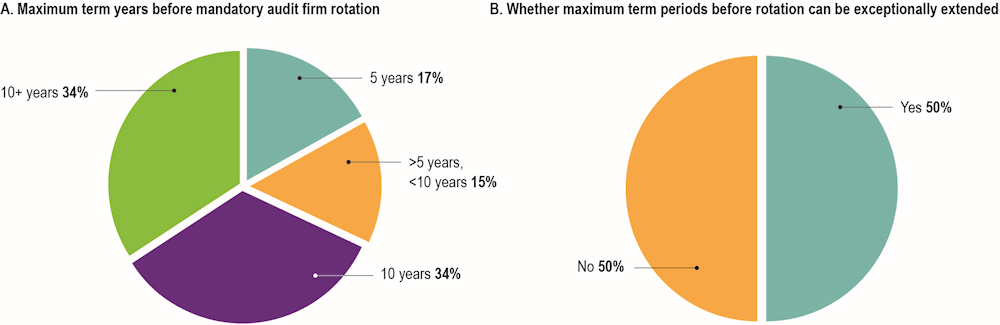

Two-thirds of Factbook jurisdictions have requirements for listed companies to rotate their external audit providers after a given period and three have code recommendations, while provisions for audit partner rotation have been established in all but four jurisdictions.

For the 36 jurisdictions that have established requirements or recommendations for the rotation of their external audit providers, the maximum term duration before rotation is required ranges between five to 24 years, with 68% of these jurisdictions requiring rotation after ten years or more. In half of the jurisdictions with a maximum term duration before rotation, the term can be exceptionally extended. This is in line with the rules introduced by the 2014 European Audit Regulation, which requires public interest entities to rotate their audit providers at least every ten years, with a possibility to extend this period to a maximum of 20 years where a public tender is held after ten years, or 24 years for joint audits. Overall, many jurisdictions subject to the European Audit Regulation have set the initial duration of engagement at ten years, and are using the option to allow extensions of the term. Among jurisdictions outside of the EU, the most common approach to rotation of audit firms is to have shorter limits, in the five to ten‑year range.

All but four jurisdictions have provisions requiring or recommending audit partner rotation after a given period. Some jurisdictions set a maximum term duration before audit partner rotation, mostly between five to seven years and often accompanied by a cooling-off period. For example, in Singapore, audit partners can be appointed for a maximum of five years before rotation with a minimum two‑year period before they can be re‑appointed by the same issuer. Indonesia has a shorter maximum period of three consecutive years. In the United States, while lead and concurring partners (or engagement quality reviewers) are required to rotate off an engagement after a maximum of five years and must be off the engagement for five consecutive years, other audit partners are subject to rotation after seven years on the engagement and must be off the engagement for two consecutive years.

Figure 4.11. Maximum term years before mandatory audit firm rotation

Note: Based on 36 jurisdictions with requirements or recommendations for audit firm rotation. See Table 4.12 for data.

The revised G20/OECD Principles put additional emphasis on the importance of audit oversight and audit regulation, stating that “a system of audit oversight and audit regulation plays an important role in enhancing auditor independence and audit quality. Consistent with the Core Principles of the International Forum of Independent Audit Regulators (IFIAR), the designation of an audit regulator, independent from the profession, and who, at a minimum, conducts recurring inspections of auditors undertaking audits of public interest entities, contributes to ensuring high quality audits that serve the public interest” (Principle IV.C).

Funding is a relevant aspect for the independence of the public oversight body from the audit profession. Public oversight bodies for audit most frequently are financed via fees levied on the audit profession or audited entities (in 21 jurisdictions), while public oversight bodies rely on both fees and government funding in 14 jurisdictions. Oversight bodies rely exclusively on the government budget to fund their operations in only 11 jurisdictions (Table 4.13).

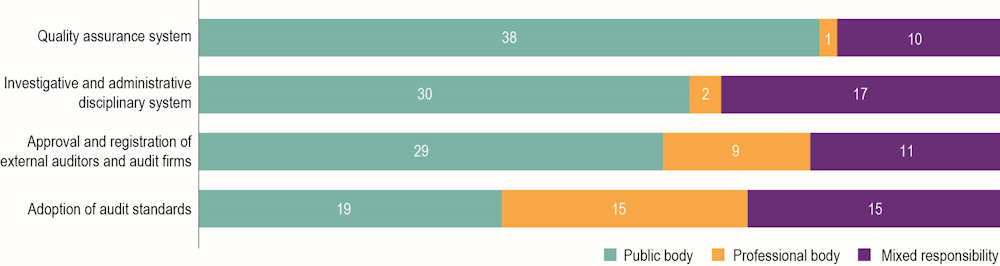

In most jurisdictions (38), the public oversight body is in charge of supervising or directly carrying out quality assurance reviews or inspections for audits of all listed entities that prepare financial reports. These responsibilities are split between the professional and public body in ten jurisdictions, while assigning such responsibility exclusively to a professional accountancy bodies is quite rare (one jurisdiction). The public oversight body is also responsible for carrying out investigative and disciplinary procedures for professional accountants in a majority of jurisdictions (30), while the responsibility is split between the professional and public body in 17 surveyed jurisdictions.

Compared to the responsibilities described above, more jurisdictions rely on delegation to professional accountancy bodies for the approval and registration of auditors and audit firms (nine) and the adoption of audit standards (15). However, in most jurisdictions public bodies take on these roles either exclusively or as a shared responsibility (for details see Figure 4.12). These figures have not changed significantly since first reported in the 2021 edition of the Factbook.

Figure 4.12. Audit oversight

4.4. Board nomination and election

In almost all jurisdictions, shareholders can nominate board members or propose candidates. The number of jurisdictions that have established majority voting requirements has nearly doubled since 2015.

Shareholders can generally nominate board members or propose candidates. Some jurisdictions set a minimum shareholding requirement for a shareholder to nominate, usually at the same level as the shareholders’ right to place items on the agenda of general meetings (Table 3.2, Figure 3.4).

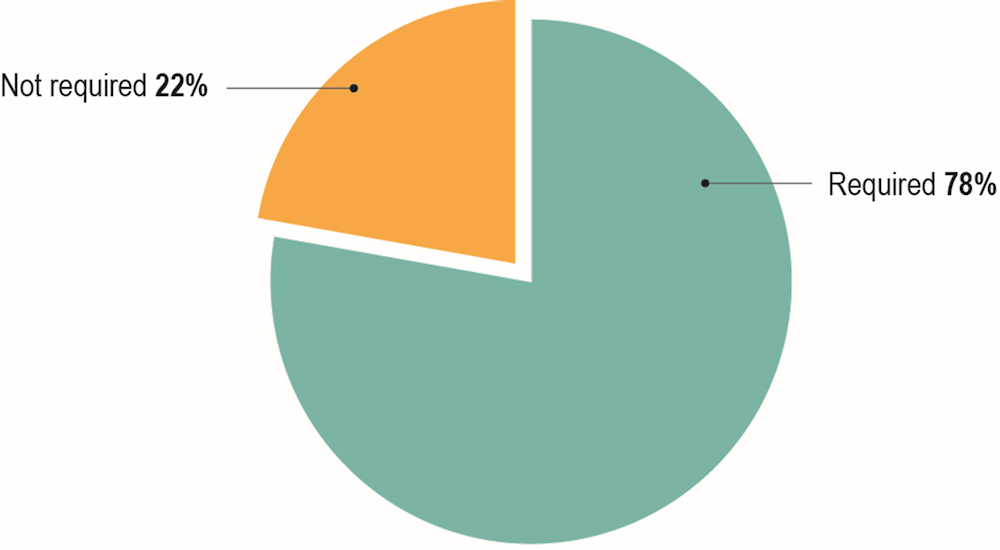

Regarding board elections, a substantial majority of jurisdictions have established majority voting requirements for board elections (78%, up from 39% in 2015), in most cases for individual candidates (i.e. not for a slate) (Table 4.14, Figure 4.13). In the United States, the Delaware Law’s default rule is plurality voting, although companies may provide for cumulative voting.

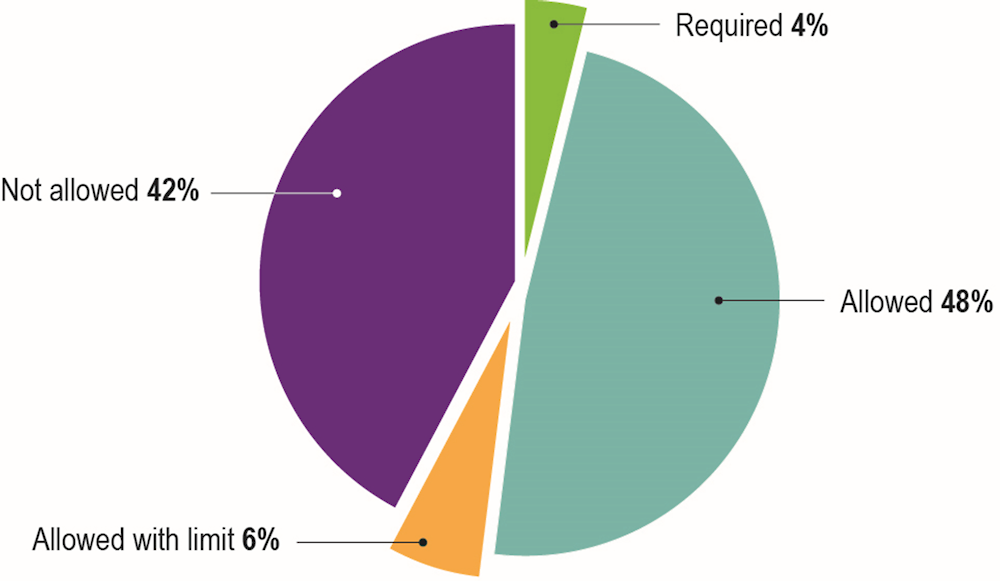

More than half of the jurisdictions (26) allow cumulative voting for electing members of the board, of which three allow it with limitations (Figure 4.14). Although a majority of jurisdictions allow cumulative voting, it has not been widely used by companies in jurisdictions where it is optional. Only two jurisdictions require cumulative voting, China and Saudi Arabia. In China, besides the election of directors, a cumulative voting system is required in the election of supervisors if a listed company whose single shareholder and its person acting in concert hold 30% or more shares.

Figure 4.13. Majority voting requirement for board election

Regarding the qualifications of candidates, 36 jurisdictions (73%) set a requirement or recommendation for qualifications for all board members while some of these and some additional jurisdictions (14) set more specific requirements or recommendations for the qualifications of at least some board appointees (e.g. independent directors, audit committee members). While most jurisdictions have established general requirements or recommendations for the qualifications of all board candidates, some jurisdictions give more emphasis to the balance of skills, experience and knowledge of the board, rather than to the qualifications of individual board members.

Figure 4.14. Cumulative voting

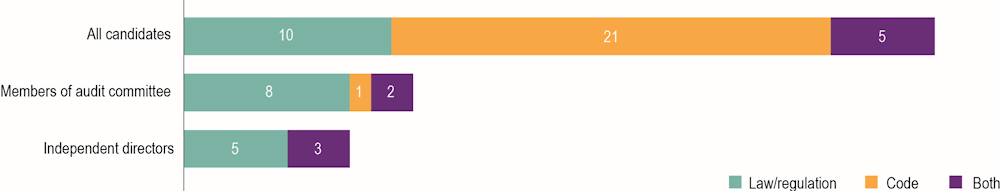

For example, Singapore’s code states that the board should comprise directors who as a group provide core competencies such as accounting or finance, business or management experience, industry knowledge, strategic planning experience and customer-based experience or knowledge. Some jurisdictions set a requirement or recommendation only for certain board members, such as members of audit committees (11 jurisdictions) or independent directors (8 jurisdictions) (Table 4.16, Figure 4.15).

Nearly two‑thirds of jurisdictions (32) require or recommend that some of the candidates go through a formal screening process, such as approval by the nomination committee (Table 4.16). In most cases, such screening processes are recommended as good practice in national codes. For example, in the United Kingdom, it is recommended that nomination committees evaluate the balance of skills, experience, independence and knowledge on the board and, in light of this evaluation, prepare a description of the role and capabilities required for a particular appointment.

Figure 4.15. Qualification requirements for board member candidates

A much smaller number of jurisdictions have established legal or listing requirements for screening processes, including in several Asian jurisdictions (China, India, Indonesia and Malaysia). Other jurisdictions with such requirements include Chile, where the Corporations Law requires that candidates for an independent director provide an affidavit stipulating their compliance with the legal requirements in the same article, and Türkiye, where large listed companies must prepare a list of independent board member candidates based on a report from the nomination committee and submit this list to the securities regulator for review. China has established a listing requirement for the stock exchange to review independent board member candidates’ qualifications. If the exchange raises an objection to a candidate, the board of directors of the listed company shall not propose that person as an independent director candidate for vote at the shareholders’ general meeting.

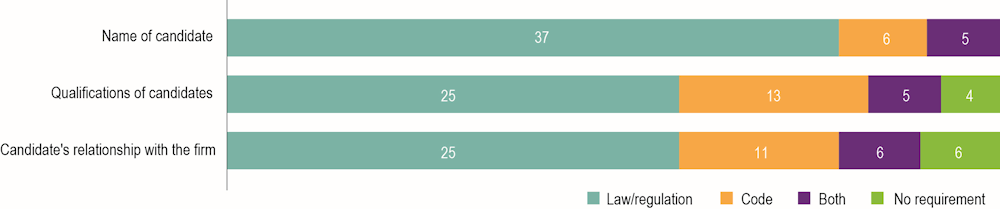

The number of jurisdictions requiring or at least recommending disclosure of relevant information to shareholders about board candidates has continued to increase.

The number of jurisdictions requiring or recommending disclosure of information on candidates’ qualifications more than doubled between 2015 and 2022, from 41% to 91% of reporting jurisdictions. Twenty-five jurisdictions establish this requirement in law/regulation, 13 recommend it in a code and five have it in both. The number of jurisdictions requiring disclosure of information on the candidate’s relationship with the firm has also more than doubled over the same period, from 37% of reporting jurisdictions in 2015 to 88% in 2022. Twenty-five jurisdictions establish this requirement in law/regulation, 11 recommend it in a code and six have it in both. All 48 jurisdictions surveyed have a requirement or recommendation to provide the names of candidates. This is a major change from 2015, when 11 jurisdictions lacked such requirements or recommendations. (Figure 4.16).

Figure 4.16. Information provided to shareholders regarding candidates for board membership

Note: Based on 48 jurisdictions for name of candidate and candidate’s relationship with the firm. Based on 47 jurisdictions for candidate qualifications. See Table 4.16 for data.

4.5. Board and key executive remuneration

Nearly all jurisdictions have introduced mechanisms for normative controls on remuneration, most often through the “comply or explain” system.

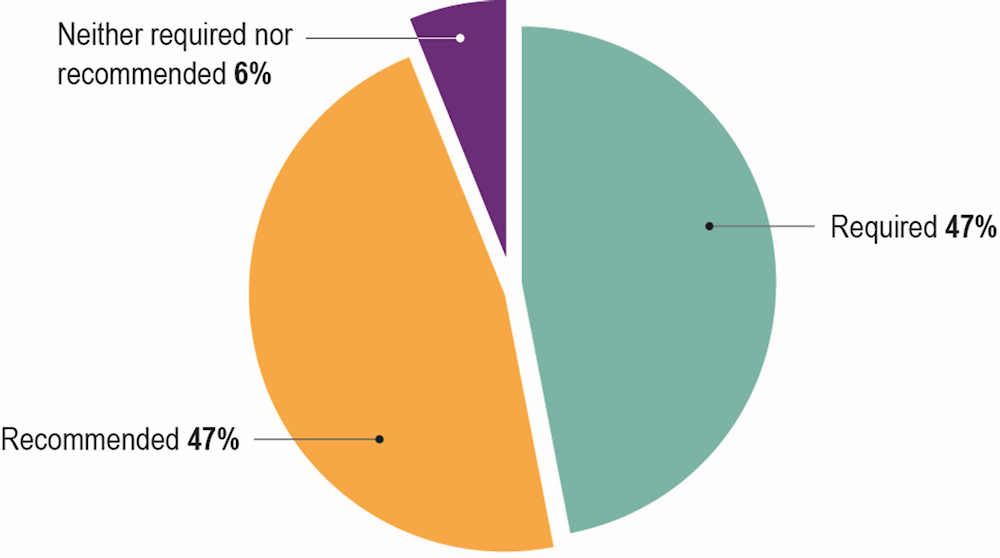

Since the 2008 financial crisis, much attention has been paid to the governance of the remuneration of board members and key executives. Besides measures to improve firm governance via independent board-level committees, 94% of jurisdictions have introduced general criteria on the structure of remuneration. Provisions tend to provide companies with substantial flexibility, with 47% establishing recommendations through the “comply or explain” system, and requirements often providing broad guidance (Figure 4.17).

Figure 4.17. Criteria for board and key executive remuneration

For example, China’s code recommends the use of long-term incentive mechanisms such as equity incentives, employee stock option plans, etc., while articles related to severance of payments “should be fair and without prejudice to the legitimate rights of listed companies.” In the European Union, where a company awards variable remuneration, the remuneration policy shall set clear, comprehensive and varied criteria for the award of the variable remuneration. It shall indicate the financial and non-financial performance criteria, including, where appropriate, criteria relating to corporate social responsibility, and explain how they contribute to the company’s business strategy and long-term interests and sustainability (Directive (EU) 2017/828 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2017 amending Directive 2007/36/EC as regards the encouragement of long-term shareholder engagement). The Norwegian Code recommends that the company should not grant share options to board members, and that their remuneration not be linked to the company’s performance. Türkiye’s code recommends that independent director remuneration should not be based on profitability, share options or company performance.

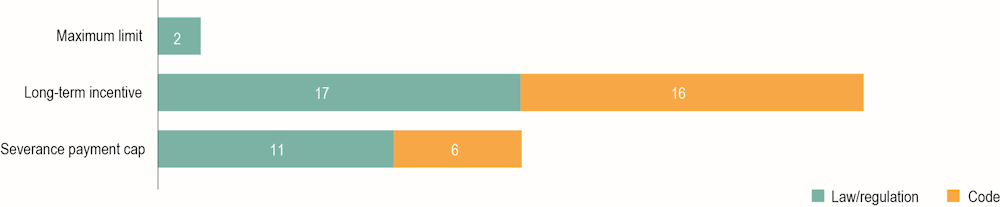

A majority of jurisdictions with general criteria also set forth some more specific measures in their laws, rules or codes. Long-term incentive mechanisms are most common, required or recommended in 33 jurisdictions (67%). These may set two‑to-three year time horizons and may involve stock options or equity incentives. In addition, provisions to limit or cap severance pay are required in 11 jurisdictions (22%) and are recommended in an additional six jurisdictions (12%) (Figure 4.18). In Australia, recommendations state that severance payments are not be provided to board members (specifically, non-executive directors). Only two jurisdictions have set maximum limits on remuneration. Saudi Arabia establishes a SAR 500 000 (Saudi Riyal) (USD 133 000) upper limit for board member remuneration. In India, if the aggregate pay for all directors exceeds 11% of profits or other specific limits in cases where the company does not have profits, then the director pay must be approved not only by shareholders but also by the government. Requirements or recommendations for ex post risk adjustments (including, provisions on golden parachutes, malus and/or clawback provisions) are rare for non-financial listed companies around the world.

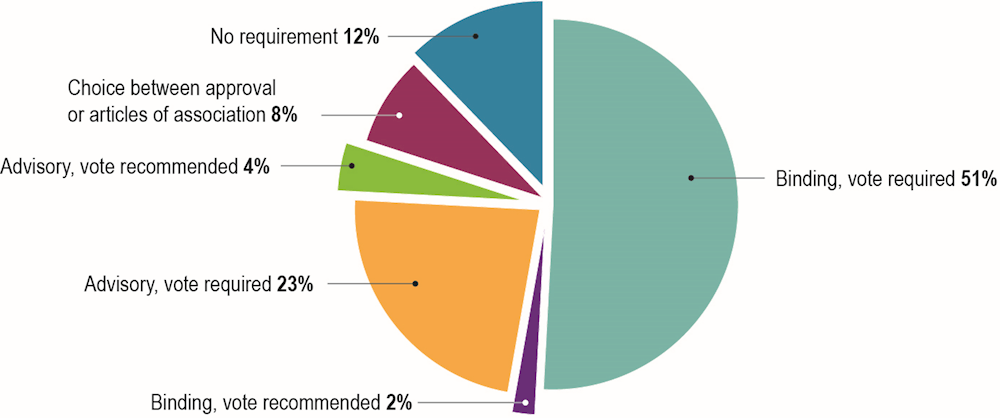

Most jurisdictions now give shareholders a say on remuneration policy and pay levels, with 88% having provisions for binding or advisory shareholder votes on remuneration policy. Binding votes on remuneration levels are a requirement in over half of jurisdictions (51%), with another 27% requiring or recommending advisory votes. Besides the distinction between binding and advisory, there are wide variations in “say on pay” mechanisms in the scope of approval.

Figure 4.18. Specific requirements or recommendations for board and key executive remuneration

Many jurisdictions have adopted rules on prior shareholder approval of equity-based incentive schemes for board members and key executives. Twenty-five jurisdictions require a binding vote on remuneration policy, one jurisdiction recommends a binding vote, and five allow choosing between shareholder approval or alternative mechanisms determined through a company’s articles of association. Norway requires a binding vote only if the company chooses to use incentive pay, while China’s requirement for a shareholder vote only applies to directors. In Costa Rica, remuneration policy for the board and key executives should always be approved by shareholders if it includes variable performance‑based bonuses in company shares.

Another 11 jurisdictions require or recommend advisory shareholder votes (Figure 4.19). In Colombia, the recommendation is that the remuneration policy for the board should always be approved by shareholders; for key executives the remuneration policy should always be approved by the board of directors. In Singapore, the Listing Manual states that issuers’ articles of association must contain a provision stating that fees payable to directors shall not be increased except pursuant to a resolution passed at a general meeting.

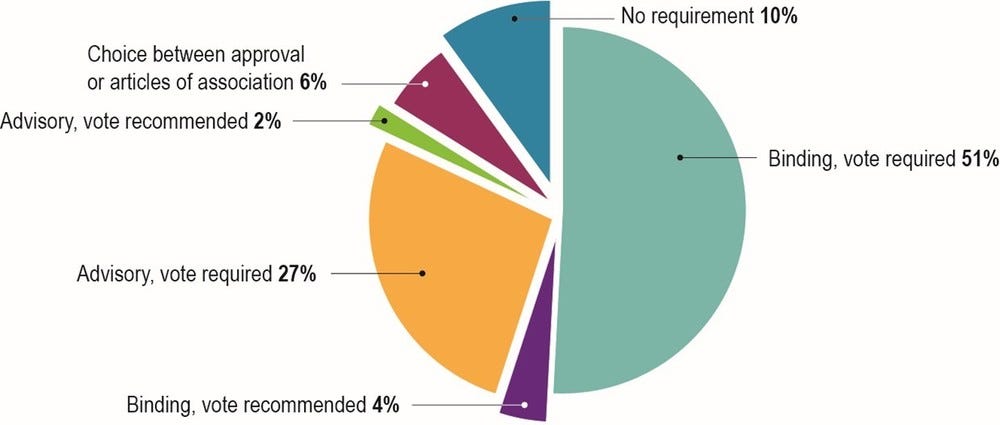

Jurisdictions also have a mix of provisions with respect to requirements or recommendations for shareholder approval of the level and/or amount of remuneration (Figure 4.20). In addition to the distinction between binding and advisory votes, there is a wide diversity of “say on pay” mechanisms in terms of the scope of approval, mainly with regard to two dimensions: voting on the remuneration policy (its overall objectives and approach) and/or total amount or level of remuneration; and voting on the remuneration for board members (which typically include the CEO) and/or the remuneration for key executives. Since 2020, the number of jurisdictions with requirements for binding votes remains high at 51% compared to just 4% who recommend it (Table 4.18).

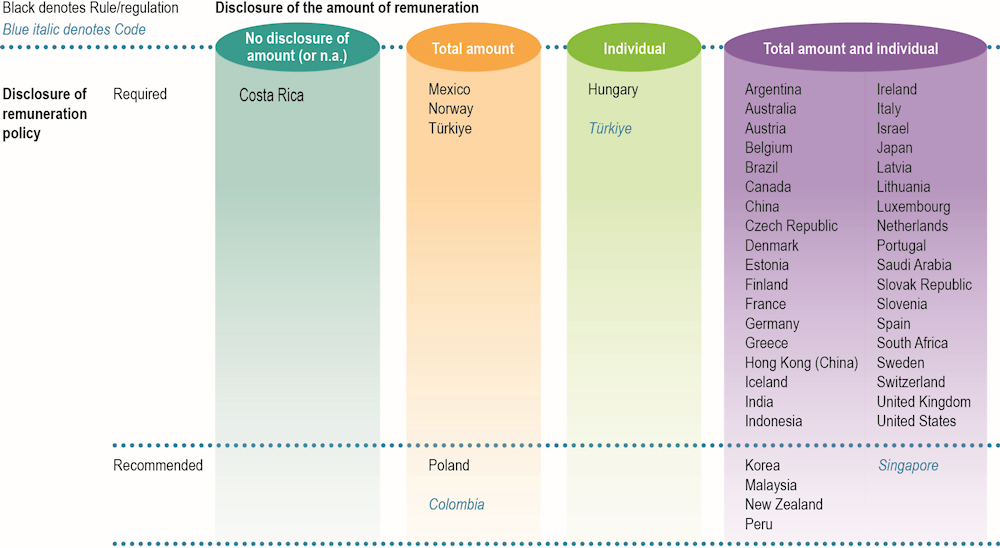

The extent to which remuneration disclosure is now required marks a major transformation of legal and regulatory frameworks since the early 2010s. An OECD survey of listed companies in 35 jurisdictions carried out in 2010 (OECD, 2011[2]) found that disclosure of individual remuneration in all listed companies was taking place in only seven jurisdictions (20%) and in a substantial majority of listed companies (80% or above) in only 15 jurisdictions (43%). Disclosure of the total individual remuneration is now a requirement in 94% of jurisdictions. These requirements usually apply to all board members and a certain number of key executives, although in some cases apply only above a certain income threshold. Only three jurisdictions do not require or recommend it (Colombia, Costa Rica, and Mexico).

Figure 4.19. Requirement or recommendation for shareholder approval on remuneration policy

The increasing attention given to remuneration by shareholders has benefited from, and has also contributed to, enhanced disclosure requirements. All jurisdictions now require or recommend that companies disclose remuneration policy, and nearly all jurisdictions require or recommend the disclosure of total aggregate remuneration.

Figure 4.20. Requirement or recommendation for shareholder approval of level/amount of remuneration

New Zealand has one of the most transparent remuneration disclosure policies, requiring it for all directors and employees earning above NZD 100 000 (USD 63 500). Some jurisdictions take a more nuanced approach. For example, in Hong Kong (China), the listing rules require issuers to disclose the remuneration of the five highest paid individuals in aggregate and by band in their annual reports, unless any of them are directors of the issuers and in that case, the identities and emoluments of each of these directors must be disclosed.

Some jurisdictions limit required reporting at the individual level. For example, in Brazil, only the highest, lowest and the average paid to directors is required. In the United States, the requirement concerns all directors, the CEO, CFO and the three most highly compensated officers other than the CEO and CFO (and above USD 100 000). In Malaysia, the recommendation is for listed issuers to disclose the remuneration component of the top five senior management in bands of RM 50 000 (USD 11 355) and to fully disclose the detailed remuneration of every senior management personnel. Japan has an amount threshold (above JPY 100 million; USD 760 000), as does Korea – directors above KRW 500 million (USD 395 900) and five employees above KRW 500 million (USD 395 900).

Figure 4.21. Disclosure of the policy and amount of remuneration

4.6. Gender composition on boards and in senior management

The G20/OECD Principles, as revised in 2023, recognise in sub-Principle V.E.4 the importance of bringing a diversity of thought to board discussions, and suggest in this regard that “[t]o enhance gender diversity, many jurisdictions require or recommend that publicly traded companies disclose the gender composition of boards and of senior management. Some jurisdictions have established mandatory quotas or voluntary targets for female participation on boards with tangible results. Jurisdictions and companies should also consider additional and complementary measures to strengthen the female talent pipeline throughout the company and reinforce other policy measures aimed at enhancing board and management diversity.” The Principles also recommend that boards regularly evaluate “whether they possess the right mix of background and competences, including with respect to gender and other forms of diversity.”

Since 2018, more jurisdictions have adopted measures to encourage women’s participation on corporate boards and in senior management, most often via disclosure requirements and regulatory measures such as mandated quotas and/or voluntary targets.

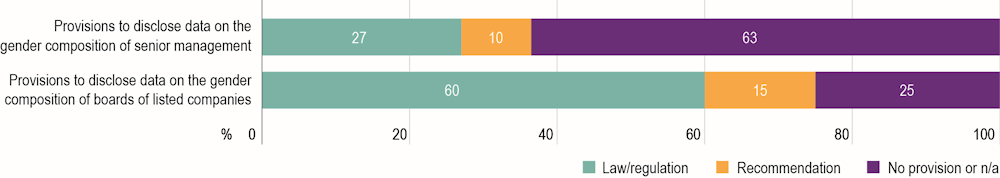

With regards to disclosure requirements, 60% of the 49 surveyed jurisdictions have mandatory provisions on the gender composition of boards of listed companies, whereas only 27% mandate disclosure of the gender composition of senior management (see Figure 4.22). Directive (EU) 2022/2381 on improving the gender balance among directors of listed companies and related measures is expected to have a sweeping impact, as it requires that countries mandate listed companies to provide competent authorities with information annually about the gender composition of their boards. If the Directive’s targets (described further below) are not being met, companies will need to explain how they plan to meet these objectives, including through more transparency in the qualification criteria and the selection process for directors. In the United States, a 2020 amendment to a US Securities and Exchange Commission regulation requires public companies to provide a description of their human capital resources to the extent that they are material to the company’s business (SEC, 2020[3]).

Argentina has a mixed approach, with companies required to disclose board composition to the securities regulator at the time of board election, while a recent change in the Corporate Governance Code also recommends companies to disclose board composition diversity on an ongoing basis. Hong Kong (China) recently introduced a requirement that listed companies disclose and explain in the corporate governance section of their annual report how and when gender diversity on boards will be achieved, including targets and timelines, as well as how a pipeline of potential board candidates to achieve gender diversity is being developed. Korea has also recently introduced mandatory disclosure for listed companies. In Singapore, listed companies are required to disclose board diversity policies in their annual reports as well as their targets for achieving diversity, including plans and timelines.

Figure 4.22. Provisions to disclose data on the gender composition of boards and of senior management

Note: This Figure shows the percentage of jurisdictions applying either a law/regulation, recommendation, or no provision. N/A = information not available. See Table 4.19 for data.

Fifteen of the 49 jurisdictions have established mandatory quotas for women’s participation on boards of listed companies. Four jurisdictions require at least 40% of women on boards (France, Iceland, Italy and Norway), six require between 20‑35%, and five mandate “at least one” female director (Finland, India, Israel, Korea and Malaysia). Requirements for specific companies vary across jurisdictions, with criteria commonly applicable to companies above a certain threshold which may take account of company size, number of employees or board members and/or level of assets. Sanctions for non-compliance exist in almost all jurisdictions with quotas, and take various forms, such as warning systems, fines, board seats remaining vacant, void nominations and delisting for non-compliant companies.

A significant boost is expected with the new EU Directive to improve gender balance amongst directors of listed companies, setting quotas for large, listed EU companies (more than 250 employees). At least 40% of the under-represented sex among non-executive board members or 33% among all directors will be required by 30 June 2026. Member states have two years to transpose the Directive’s provisions into national law. In addition, large listed companies will also have to undertake individual commitments to reach gender balance among their executive board members. Companies that fail to meet this objective will have to report the reasons and the measures they are taking to address this shortcoming. Member states will be required to set up a penalty system that is effective, proportionate, and dissuasive for companies that fail to meet the new standards by 2026 (European Commission, 2012[4]).

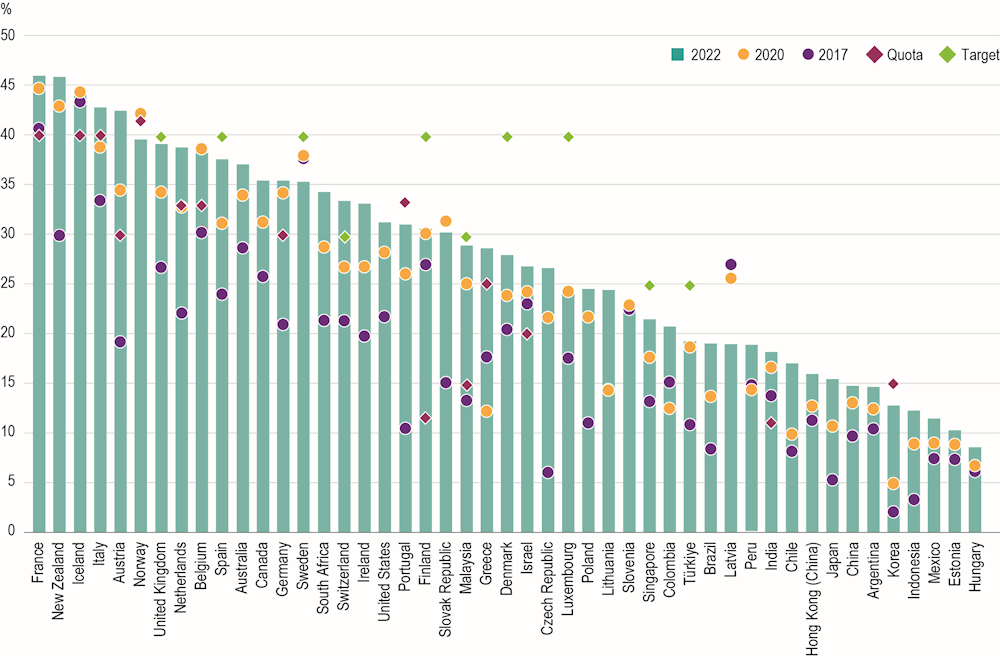

Fourteen of the 49 jurisdictions have introduced recommended targets for listed companies or require listed companies to set their own numerical targets either in their corporate governance codes, applicable on a comply-or-explain basis, or in legislation. Six jurisdictions have set targets at 40% of women on boards, compared to four that have set mandatory quotas at the same level. Based on data comparing a subset of the largest listed companies in each jurisdiction, the average participation of women on boards across all 49 jurisdictions reached 27% in 2022, a significant increase from 19% in 2017.

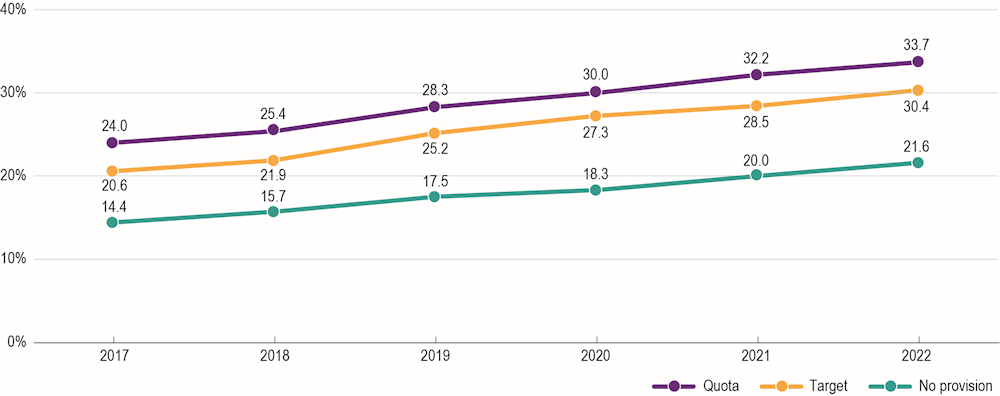

Jurisdictions have adopted a range of approaches to promote greater gender diversity on boards. Notwithstanding the policy approach, significant progress has been achieved by many jurisdictions since 2017, even in those without quotas or targets. While binding quotas have yielded the highest levels of gender diversity on average over the last six years (as seen in Figure 4.23 below), jurisdictions applying targets or adopting other measures to encourage gender diversity have experienced a similar rate of growth in levels of gender diversity, while starting from a lower base. The progress achieved in jurisdictions with no quota or target in place shows that alternative and complementary measures ranging from shareholder initiatives in support of greater diversity to promoting a more enabling environment for the advancement of women on boards and in leadership positions can also play an important role in achieving results.

Figure 4.23. Aggregate change in the percentage of women on boards

Note: Average percentage of women on boards was calculated for the three categories relevant to the figure above, namely, jurisdictions with quotas, targets or no provision. Finland, Germany, Malaysia and the Netherlands are counted twice due to their implementation of both a quota and a target. Data from 2017–19 was obtained from OECD (2021[5]). Costa Rica is not included due to lack of data for the full time period covered. See Table 4.20 for data and description of data sources.

In terms of outcomes, the largest and most actively traded companies in eight jurisdictions with quotas met or exceeded their prescribed quotas in 2022, while this was the case in only a few jurisdictions with targets. Among the jurisdictions that have yet to achieve their quotas, one was very recently introduced.

Figure 4.24. Share of women on boards of largest listed companies (in 2017, 2020, and 2022) with reference to implemented quotas & targets, percentage

Note: In instances of an “at least one’’ quota (Finland, India, Israel, Korea and Malaysia), average board size of the relevant jurisdiction was used to calculate an average percentage for the applicable quota in the Figure above. Norway’s quota is dependent upon board size and may range from 33% to 50%; for the Figure above, the average between the smallest and highest quota was used. Japan set a target at 12% for listed companies on the First section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange by the end of 2022. It is not shown in the Figure because of a substantial difference between the coverage of companies, etc. to which the target applies and the data that the Figure covers. Lithuania’s datapoints for 2017 and 2020 are identical, these markers were adjusted so both could be observed. Data from 2017–19 were obtained from OECD (2021[5]) See Table 4.20 for data.

Source: MSCI Women on Boards: Progress Report 2022 (except as otherwise noted for 13 jurisdictions referenced in footnotes of Table 4.20).

For Finland, average board size data for 2022 may be found here.

For India, average board size data for 2020 may be found here.

For Israel, average board size data for 2022 was provided by the Israeli Securities Authority (ISA).

For Korea, average board size data for 2022 may be found here.

For Malaysia, average board size data for 2022 was provided by the Securities Commission (SC Malaysia).

Of particular note, ten jurisdictions (Austria, Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Poland, Portugal, and the Slovak Republic) have at a minimum doubled since 2017 the percentage of women participating on boards (for Korea, the increase is six‑fold). Another notable case is New Zealand, a jurisdiction without a quota or target, which nevertheless had one of the highest shares of women on boards in 2022. New Zealand’s progress may have been supported by advocacy initiatives by associations and independent bodies. Institutional investor pressure, including votes against the re‑election of directors in companies that fail to encourage diversity, has also had an important influence in some jurisdictions without quotas or targets (OECD, 2020[6])). For instance, in the United States, firms where the three largest institutional investors were categorised as having comparatively higher ownership stakes increased gender diversity on boards following pressure through voting strategies and influential campaigns (Gormley et al., 2023[7]).

Complementary initiatives also exist in jurisdictions where quotas have been adopted. For example, the Israel Securities Authority established in October 2021 Forum +35 to promote gender diversity on boards of reporting corporations and other entities supervised by the ISA. The Forum’s objective is to have female directors comprise at least 35% of the boards of all supervised entities by 2026. The Forum includes representatives from the public, private and NGO sectors who contribute a broad perspective on this issue, and voluntary representatives of supervised entities whose boards have at least 35% of female directors.

With regards to women in management, as defined by the International Labour Organization, while the average of women in management (34%) exceeded the average of women on boards (27%) in 2022, the percentage of women on boards has grown by 8 percentage points since 2017, whereas the percentage of women in management has only grown by 2 percentage points.

Some jurisdictions are also extending mandatory quotas or targets to senior executives. For example, in France companies with more than 1 000 employees will have to meet 30% and then 40% quotas for more equal gender representation among senior executives and management committee members. From 2022, companies must publish annually on their websites an analysis of gender representation for their senior executive roles and management committee membership. From 2026, companies will have two years to ensure that women hold 30% or more of senior executive roles and management committee seats, and to negotiate corrective measures or implement measures in the absence of an agreement. From 2029, companies will have two years to comply with the 40% quota, and sanctions for non-compliance will take effect in 2031. Switzerland also started to require at least 20% of women on the management board beginning in 2021 (in addition to its 30% quota for women on boards). Furthermore, Germany is requiring listed companies to set individual targets for the executive board and the two management levels below the board. If the executive board of a listed company consists of four or more persons, at least one woman shall be appointed as a member of the board.

Table 4.1. Basic board structure: Classification of jurisdictions

|

One‑tier system (23) |

Two-tier system (8) |

Optional for one‑tier and two‑tier system (15 + EU) |

Multiple option with hybrid system (3) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Australia |

Austria |

Argentina1 |

Italy |

|

|

Canada |

China |

Belgium |

Japan |

|

|

Chile |

Estonia |

Brazil |

Portugal |

|

|

Colombia |

Germany |

Czech Republic |

||

|

Costa Rica |

Iceland2 |

Denmark |

||

|

Greece |

Indonesia |

Finland |

||

|

Hong Kong (China) |

Latvia |

France |

||

|

India |

Poland |

Hungary |

||

|

Ireland |

Lithuania |

|||

|

Israel |

Luxembourg |

|||

|

Korea |

Netherlands |

|||

|

Malaysia |

Norway3 |

|||

|

Mexico |

Slovenia |

|||

|

New Zealand |

Slovak Republic |

|

||

|

Peru |

Switzerland |

|

||

|

Saudi Arabia |

European Public LLC4 |

|||

|

Singapore |

||||

|

South Africa |

||||

|

Spain |

||||

|

Sweden |

||||

|

Türkiye |

||||

|

United Kingdom |

||||

|

United States |

||||

1. In Argentina, companies falling within the scope of public offering regulations are required to have an Audit Committee (Comité de Auditoría) with oversight functions. It is designated and integrated by members of the Board (majority independent). In this sense, the Audit Committee is generally considered a sub-organ of the Board. On the other hand, companies in Argentina have also another body (distinct from the board) with oversight functions, the Statutory Auditors Committee (Comisión Fiscalizadora) and Supervision Council (Consejo de Vigilancia). In that sense, the Capital Market Law foresees that companies making public offering and having established an Audit Committee may dispense with a Statutory Auditors’ Committee.

2. In Iceland, the board in its supervisory function is composed of non-executive directors only. In national law, the board appoints and delegates the executive powers to a single person, the CEO (not a member of the supervisory board). The CEO is the chair of the management board, which is composed of executive directors.

3. In Norway, both supervision and management of the operations of the company are the responsibility of the board of directors. In companies with more than 200 employees, a corporate assembly shall be elected. The corporate assembly’s tasks are limited to and consist of electing the members and the chairman of the board of directors, supervising the board of directors’ and general manager’s administration of the company, and issuing opinions to the general meeting as to whether the board of directors proposal for income statements and balance sheets should be adopted and as to the board of directors’ proposal for the employment of the profit or coverage of losses. At the proposal of the board of directors, the corporate assembly may adopt resolutions regarding certain investments, efficiency measures or alterations of the company’s operations that will entail a major change or reallocation of the labour force. Lastly, the corporate assembly may adopt recommendations to the board of directors.

4. The EU regulation (EC/2157/2001) stipulates that European public limited liability company (Societas Europaea) shall have the choice of a one‑tier system (an administrative organ) or a two‑tier system (a supervisory organ and a management organ).

Table 4.2. One‑tier board structures in selected jurisdictions

|

Jurisdiction |

Description of board structure |

|---|---|

|

Australia |

|

|

Finland |

|

|

India |

|

|

Mexico |

|

|

New Zealand |

|

|

South Africa |

|

|

Sweden |

|

|

Switzerland |

|

|

United States |

|

Table 4.3. Two-tier board structures in selected jurisdictions

|

Jurisdiction |

Description of board structure |

|---|---|

|

Brazil |

Supervisory body (optional except for state‑owned enterprises) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management body (executive and non-executive board) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

China |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Estonia |

Supervisory body |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management body |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Germany |

Supervisory body |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management body |

|

|

|

|

Indonesia |

Supervisory body |

|

|

|

|

|

Management body |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4.4. Examples of a hybrid board structure

|

Jurisdiction |

Structure |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Italy |

[T] The “traditional” model1 |

- |

Board of directors |

A board of directors and a board of statutory auditors (collegio sindacale) both appointed by the shareholders’ meeting; the board of directors may delegate day-to-day managerial powers to one or more executive directors, or to an executive committee. |

|

- |

Board of statutory auditors |

|||

|

[2] The “two‑tier” model (dualistico) |

- |

Supervisory board |

A supervisory board appointed by the shareholders’ meeting and a management board appointed by the supervisory board, unless the bylaws provide for appointment by the shareholders’ meeting; the supervisory board is not vested with operative executive powers, but, in the by-laws, it may be entrusted with “high level” management powers. |

|

|

- |

Management board |

|||

|

[1] The “one‑tier” model (monistico) |

- |

Board of directors |

A board of directors appointed by the shareholders’ meeting and a management control committee made up of non-executive independent members of the board; the board may delegate day-to-day managerial powers to one or more managing directors, or to an executive committee. |

|

|

- |

Management control committee |

|||

|

Japan |

[A] “Company with statutory auditors” model |

- |

Board of directors |

There must be at least one executive director and may be non-executive directors as well. Where this model is adopted, there is a separate organ of the company called the “statutory auditors” (Kansayaku2), which has the function of auditing the execution of duties by the directors. |

|

- |

Statutory auditors |

|||

|

[C] “Company with three committees” model |

- |

Board of directors |

The company must establish three committees (nomination, audit and remuneration committees), with each committee composed of three or more directors, and a majority must be outside directors. |

|

|

- |

Three committees |

|||

|

[S] “Company with an audit and supervisory committee” model |

- |

Board of directors |

The company must establish an audit and supervisory committee composed of more than three directors, the majority being outside directors. The committee has mandates similar to that of the statutory auditors, as well as those of expressing its view on the board election and remuneration at the shareholder meeting. |

|

|

- |

Audit and supervisory committee |

|||

|

Portugal3 |

[2C] The “traditional” model |

- |

Board of directors |

A board of directors and a supervisory board (conselho fiscal) appointed by the shareholders; the board of directors may delegate managerial powers to one or more executive directors or to an executive committee; members of the supervisory board cannot be directors and, in case of listed companies, the majority must be independent. |

|

- |

Supervisory board (conselho fiscal) |

|||

|

[2A] The “one‑tier” model |

- |

Board of directors |

A board of directors and a supervisory board (comissão de auditoria) appointed by the shareholders; the board of directors may delegate managerial powers to one or more executive directors or to an executive committee; members of the supervisory board must be non-executive directors and, in case of listed companies, the majority must be independent. |

|

|

- |

Supervisory board (comissão de auditoria) |

|||

|

[2G] The “two‑tier” model |

- |

Executive board of directors |

A board of directors and a supervisory board (conselho geral e de supervisão); members of the board of directors are appointed by the supervisory board (unless the articles of association provide for appointment by shareholders); members of the supervisory board cannot be directors and are appointed by shareholders and, in case of listed companies, the majority must be independent. Listed companies are also required to set up a financial affairs committee (comissão para as matérias financeiras) which is a specialised committee of the supervisory board composed by a majority of independent members. |

|

|

- |

Supervisory board (conselho geral e de supervisão) |

|||

1. In Italy, the traditional model, where the general meeting appoints both a board of directors and a board of statutory auditors, is the most common board structure. The board of statutory auditors functions as an internal auditing board.

2. In Japan, statutory auditors (Kansayaku) are different from external auditors. Statutory auditors are appointed by shareholders meetings and their principal role is to audit activities of directors from a legal viewpoint. Statutory auditors include both internal ones and external ones (external statutory auditors are those who have not worked for the company as executive directors or employees.). The Companies Act requires certain large companies to have committees of statutory auditors and half or more of the members of such committees shall be external statutory auditors.

3. In Portugal, all three models comprise two boards (a board of directors and a supervisory board), and a statutory auditor although subject to different rules. Portugal no longer has the concept of external auditor: since the transposition/implementation of the European audit legislation (2014) there is only the statutory auditor, which can perform the tasks once reserved to the external auditor. Notwithstanding, some national companies prefer to appoint a different auditor to issue the audit report as well as to carry out audit services with a broader scope than statutory audits, provided that the integrity of the functions and the liability regime of the statutory auditor are not compromised.

Table 4.5. Board size and director tenure for listed companies

|

Jurisdiction |

Tier(s) |

Board of directors (Supervisory board for 2‑tier board) |

Management board (two‑tier system) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Size |

Appointment |

Size |

Appointment |

|||||

|

Minimum |

Maximum |

Maximum term years |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Maximum term years |

By |

||

|

Argentina |

2 |

3 |

- |

3 to 5 |

3 |

- |

3 to 5 |

GSM |

|

Australia |

1 |

3 |

- |

31 |

||||

|

Austria |

2 |

3 |

5 |

- |

SB |

|||

|

Belgium |

2 |

3 |

- |

6 |

3 |

6 |

SB |

|

|

Brazil |

1 |

3 |

- |

3 [2] |

||||

|

2 |

3 |

5 |

- |

3 |

- |

3[2] |

GSM |

|

|

Canada |

1 |

3 |

- |

12[1] |

||||

|

Chile |

1 |

5 or 7 |

- |

3 |

||||

|

China |

2 |

3 |

- |

3 |

5 |

19 |

3 |

GSM |

|

Colombia |

1 |

5 |

10 |

- |

||||

|

Costa Rica |

1 |

3 |

- |

- |

||||

|

Czech Republic |

1+2 |

(3) |

- |

(3) |

- |

GSM, SB |

||

|

Denmark |

1+2 |

3 |

4 (1) |

1 |

SB |

|||

|

Estonia |

2 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

- |

5 |

SB |

|

|

Finland |

1+2 |

- |

(1) |

(1) |

(GSM) |

|||

|

France |

1+2 |

3 |

18 |

6 (4) |

1 |

7 |

6 |

SB |

|

Germany |

2 |

3 |

21 |

5 |

1‑2 |

- |

5 |

SB |

|

Greece |

1 |

3 |

15 |

6 |

||||

|

Hong Kong (China) |

1 |

[3]3 |

- |

(3) |

||||

|

Hungary |

1+2 |

(3)4 |

- |

(5) |

3 |

- |

- |

GSM |

|

Iceland |

2 |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

SB |

|

India5 |

1 |

3/6 |

15 |

3 to 5 |

||||

|

Indonesia |

2 |

2 |

- |

5 |

2 |

- |

5 |

GSM |

|

Ireland |

1 |

2 |

- |

|||||

|

Israel |

1 |

46 |

- |

- |

||||

|

Italy |

T+1 |

- |

3 |

|||||

|

2 |

3 |

- |

3 |

2 |

- |

3 |

SB |

|

|

Japan |

C+S |

3 |

- |

1 |

||||

|

A |

3 |

- |

2 |

|||||

|

Korea |

1 |

3 (smaller for SMEs) |

- |

3 |

||||

|

Latvia |

2 |

5 |

20 |

5 |

3 |

- |

5 |

SB |

|

Lithuania |

1+2 |

3 |

15 |

4 |

3 |

- |

4 |

SB/GSM7 |

|

Luxembourg |

1+2 |

3 |

6 |

- |

- |

6 |

SB/GSM |

|

|

Malaysia |

1 |

2 |

- |

38 |

||||

|

Mexico |

1 |

3 (3) |

21 (15) |

- |

||||

|

Netherlands |

1+2 |

- |

(4) |

- |

(4) |

GSM |

||

|

New Zealand |

1 |

- |

- |

|||||

|

Norway |

1 |

3 |

- |

4 (2) |

||||

|

2 |

12 |

- |

4 (2) |

5 |

- |

- |

SB |

|

|

Peru |

1 |

39 |

- |

3 |

||||

|

Poland |

2 |

5 |

- |

5 |

1 |

- |

5 |

SB |

|

Portugal |

2C+2A+2G |

- |

4 |

- |

4 |

SB/GSM10 |

||

|

Saudi Arabia |

1 |

3 |

- |

4 |

||||

|

Singapore |

1 |

3 |

- |

3 |

||||

|

Slovak Republic |

1+2 |

3 |

- |

5 |

1 |

- |

5 |

GSM/SB |

|

Slovenia |

1+2 |

3 |

- |

6 |

1 |

- |

6 |

SB |

|

South Africa |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

GSM |

|

Spain |

1 |

3 |

- |

4 |

||||

|

Sweden |

1 |

3 |

- |

4 (1) |

||||

|

Switzerland |

1+2 |

1 |

- |

1 |

SB |

|||

|

Türkiye |

1 |

5 |

- |

311 |

||||

|

United Kingdom12 |

1 |

2 |

- |

(1) |

||||

|

United States13 |

1 |

[3] |

- |

3 |

||||

Key: [ ] = requirement by the listing rules; ( ) = recommendation by the codes or principles; “-” = absence of a specific requirement or recommendation; SB = Supervisory board; GSM = General Shareholder Meeting. For definitions of tiers for Italy, Japan and Portugal, see Table 4.4.

1. In Australia, directors may be re‑appointed for successive terms. This includes independent directors.

2. In Canada, the Canada Business Corporations Act requires annual elections of directors for distributing corporations.

3. In Hong Kong (China), the Main Board Listing Rules do not contain any requirements for minimum board size but they require at least three independent non-executive directors and they must represent at least one‑third of the board.

4. In Hungary, in the case of a one‑tier system, there cannot be less than five members.

5. In India, while the minimum number of directors on the board of a public company is three, the boards of the top 2 000 listed entities, based on market capitalisation, are required to comprise not less than six directors. Furthermore, the maximum number of directors (15) may be increased by a special resolution of the shareholder meeting.

6. In Israel, the minimum board size is underpinned by the requirement for the membership of audit committees. In addition, according to the Israeli company law, there is a limited term for certain types of directors such as an external director.

7. In Lithuania, the board shall be elected by the supervisory board. If the supervisory board is not formed, the board shall be elected by the general meeting of shareholders.

8. In Malaysia, a director’s retirement is based on one‑third rotation at every annual general meeting where the longest serving director in the office (since the last election) shall retire. A retiring director shall be eligible for re‑election.

9. In Peru, the corporation’s bylaws must establish a fixed number or a maximum and minimum number of directors. When the number of directors is variable, the shareholder´s meeting, before the election, must decide on the number of directors to be elected for the corresponding period. The number of directors shall not be less than three.

10. In Portugal, when a company adopts the “two‑tier” model, the number of members of the supervisory board must be higher than that of the executive board of directors. Furthermore, in the “two‑tier” model, members of the executive board are appointed by the supervisory board, unless the articles of association provide that they are appointed by the shareholders. In the remaining two models, members of the board of directors are elected by the shareholders.

11. In Türkiye, directors may be re‑appointed unless otherwise stated in the company’s articles of association. Independent directors may also be re‑appointed. However, independence criteria set forth under the Corporate Governance Principles requires the independent director not to have served as a board member for six years in the company within the previous 10 years. Therefore, it would be possible to re‑appoint an independent director successively for a second term only.

12. In the United Kingdom it would be possible for two executive directors to be the sole members of a board. However it is recommended that there should also be an independent chair and independent board members. Independent board members have to be re‑appointed each year but the UK Corporate Governance Code recommends that they do not stay in post beyond a total of nine years.

13. In the United States, NYSE and Nasdaq rules require companies to have an audit committee of at least three members. The maximum term of three years would apply to companies listed on the NYSE with classified boards of directors.

Table 4.6. Board independence requirements for listed companies

|

Jurisdiction |

Tier(s) |

Board independence requirements |

Key factors in the definition of independence |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Separation of the CEO and Chair of the board (as applicable to 1‑tier boards) |

Minimum number or ratio of independent directors |

Term Maximum term of office & effect at the expiration of term |

Independence from “substantial shareholders” |

||||

|

Requirement |

Shareholding threshold of “substantial shareholders” for assessing independence |

||||||

|

Argentina |

2 |

- |

(66%) |

10 |

No independence |

Yes |

5% |

|

Australia |

1 |

Recommended |

(>50%) |

- |

- |

(Yes) |

5% |

|

Austria |

2 |

- |

(50%) |

- |

- |

No |

- |

|

Belgium |

1+2 |

Recommended |

3 |

12 |

No independence |

Yes |

10% |

|

Brazil1 |

1+2 |

Required |

20% (33%) |

- |

- |

(Yes) |

(50%) |

|

Canada |

1 |

- |

2 (>50%)2 |

- |

- |

|

|

|

Chile |

1 |

Required |

13 |

- |

- |

Yes |

10% |

|

China |

2 |

- |

33% |

6 |

No independence |

Yes |

(5%); rank in top 5 shareholders |

|

Colombia |

1 |

Required |

[25%] |

- |

- |

[Yes] |

[<50%] |

|

Costa Rica4 |

1 |

Recommended |

2 |

9 |

No independence |

Yes |

10% |

|

Czech Republic |

1+2 |

Recommended |

(>25%) |

- |

- |

(Yes) |

- |

|

Denmark |

1+2 |

Required |

(50%) |

(12) |

(No independence) |

(Yes) |

(20%) |

|

Estonia |

2 |

|

(50%)5 |

10 |

(No independence) |

Yes |

- |

|

Finland |

1+2 |

Recommended |

(>50%) |

‑6 |

- |

(Yes for 2) |

(10%) |

|

France |

1+2 |

- |

(50% or 33%) |

(12) |

(No independence) |

(Yes) |

(10%) |

|

Germany7 |

2 |

- |

(Appropriate number with further specifications) |

(12) |

Indication for non-independence |

(Yes) |

- |

|

Greece |

1 |

Required |

2 (1/3) |

9 |

(No independence) |

No |

- |

|

Hong Kong (China) |

1 |

Recommended |

[3 and 33%] |

(9) |

(Explain)8 |

Yes |

10% |

|

Hungary |

1+2 |

- |

50% |

(5) |

(No independence) |

Yes9 |

30% |

|

Iceland |

2 |

(50%) |

- |

(Explain) |

Yes for 2 |

10% |

|

|

India |

1 |

‑10 |

[33% or 50%] |

1011 |

No independence for 3 years |

Yes |

2% |

|

Indonesia |

2 |

- |

[30%] |

1012 |

[Explain] |